Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

- In the first instance, the baseline engine model was configured in the software to be used during the study;

- The second step was the implementation of the oxy-fuel combustion in the model, aiming to achieve an engine performance close to the original;

- Finally, the in-situ oxygen production system was designed separately from the main engine model.

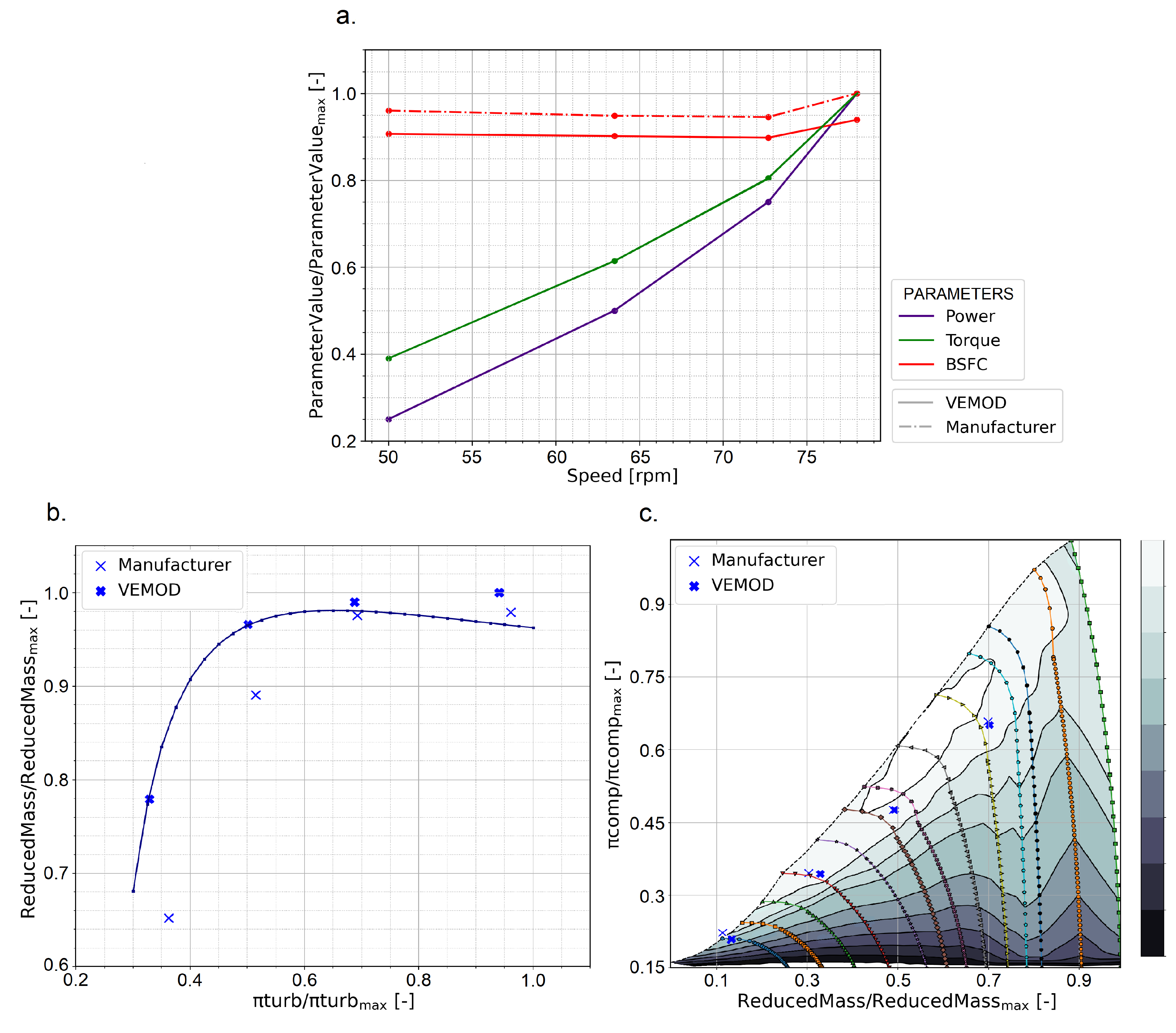

2.1. Configuration of the Baseline Model

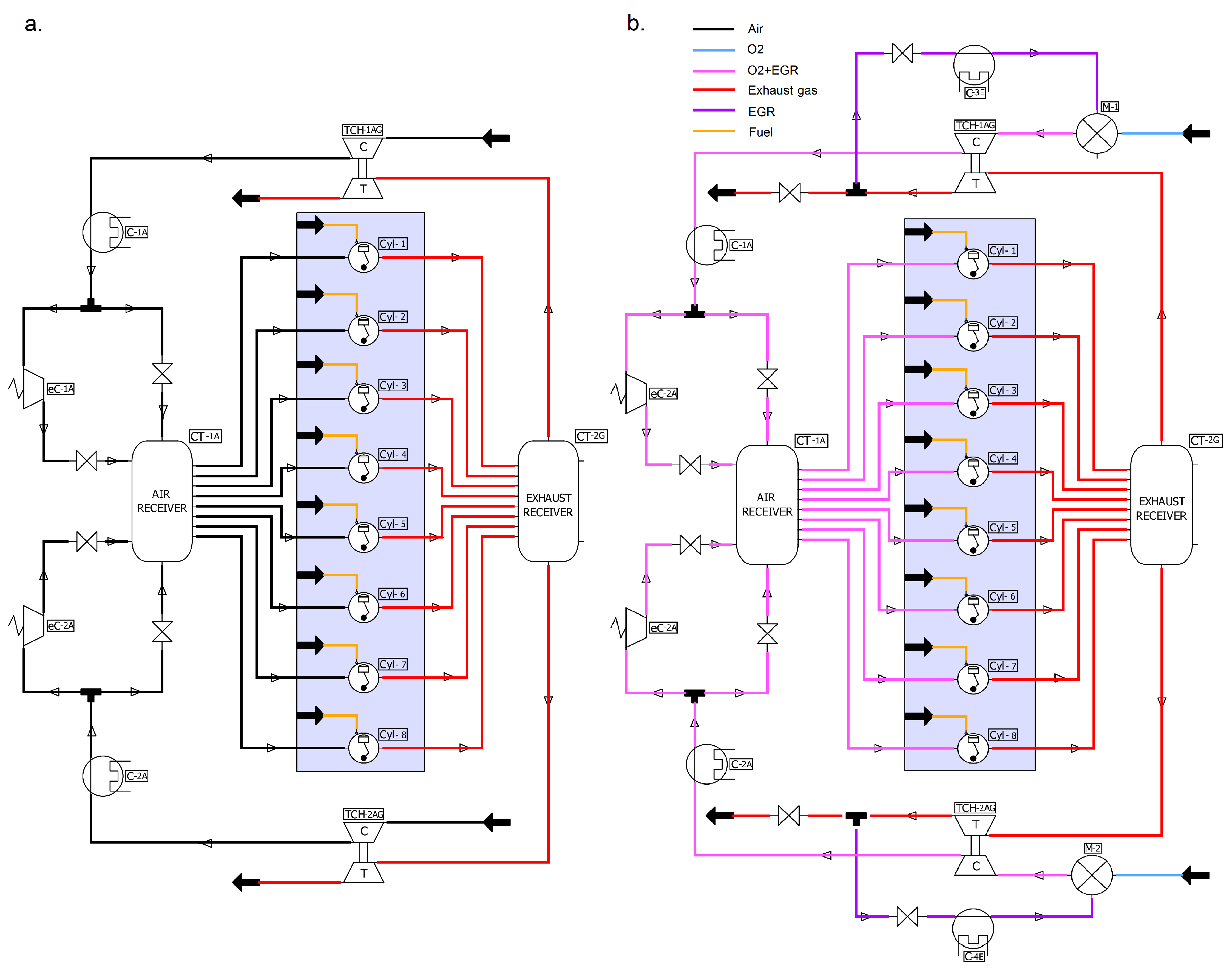

2.2. Implementation of the Oxy-Fuel Combustion

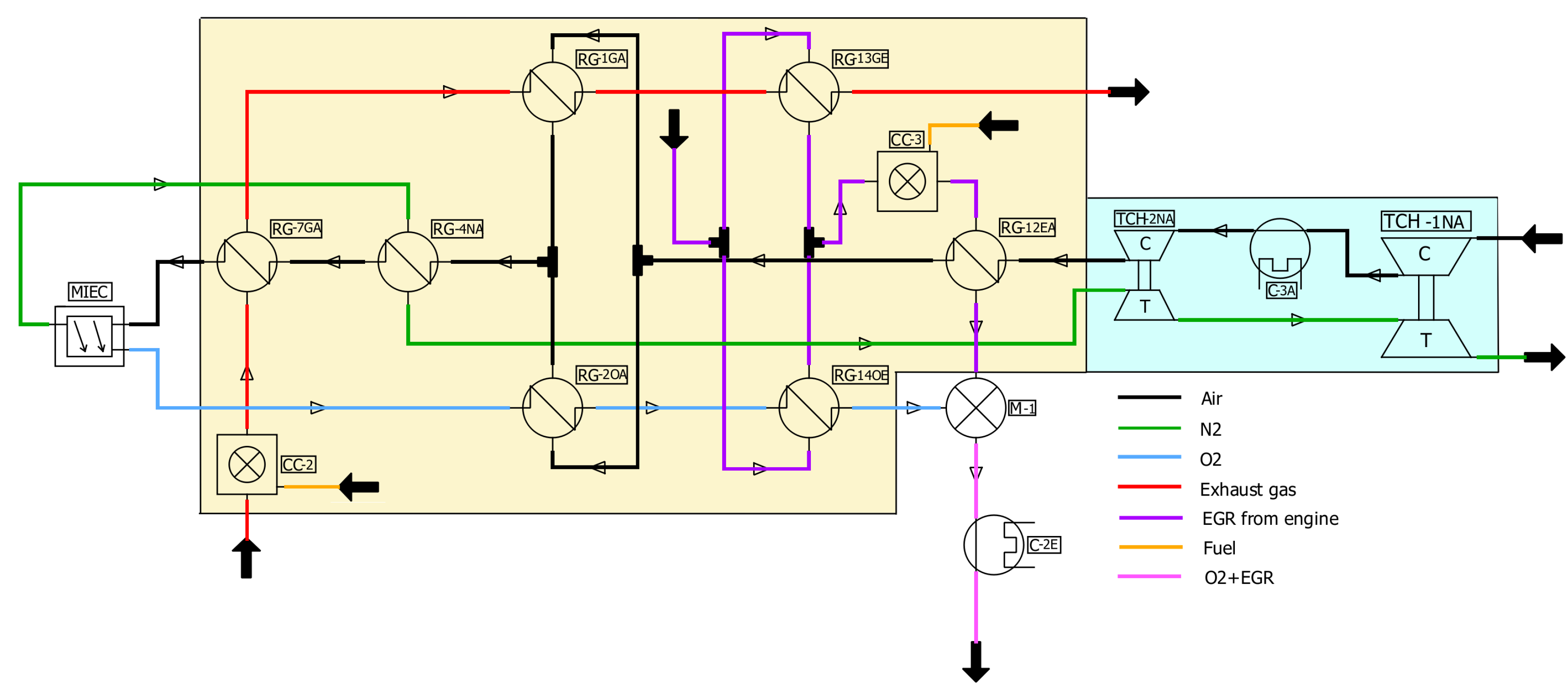

2.3. Design of the O Production System

2.3.1. Reference Layout

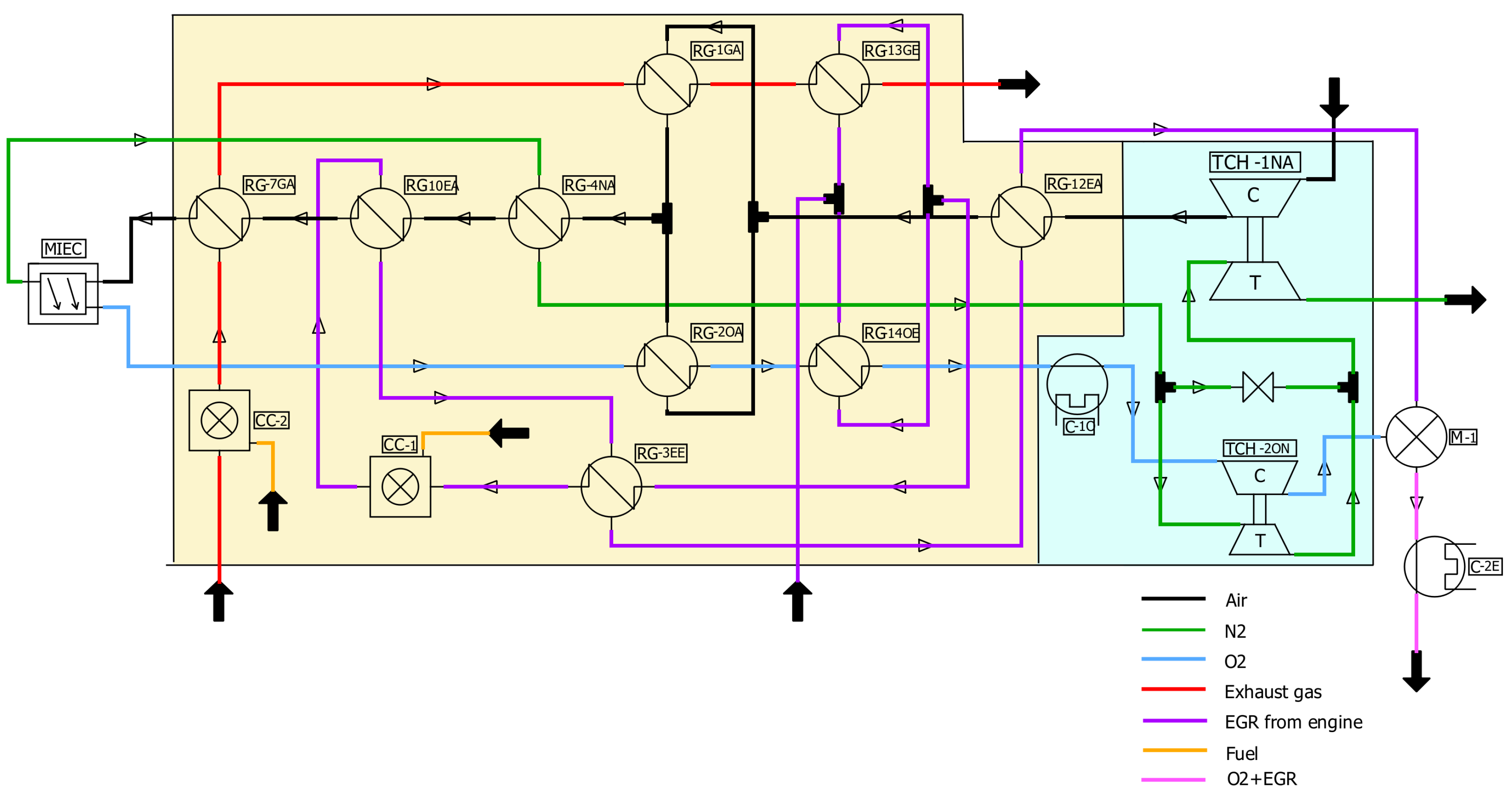

2.3.2. Layout Conception

2.3.3. Layout Optimization

- Parallel configuration: The first turbocharging proposal consists of connecting two units in parallel with a common N line at the inlet of the turbines. The TCH-1NA turbocharger is placed at the beginning of the air flow line and the TCH-2ON turbo at the end of the O line to achieve the required O partial pressure gradient in the MIEC. This parallel configuration is shown in the light blue box in Figure 4.

- Serial configuration: Maintaining the location of the turbochargers in the scheme, the second turbocharging attempt was a series turbine configuration in which the N line is regulated by a by-pass valve to first drive the TCH-2ON turbine and then, when the N flow confluences again, drive the TCH-2ON turbine. The by-pass valve lift was swept to determine the best possible value. This serial configuration is shown in the light blue box in Figure 5.

- Two stage air compression: The third configuration analyzed was another serial arrangement but in this case for both turbines and compressors. The air is compressed twice for further increase the partial pressure gradient in the MIEC without the need to generate vacuum. This configuration is shown in the light blue box in Figure 6; the heat exchanger system is different from that shown in the previous figures because, as it will be demonstrated in the Results section, the EGR line burner is not necessary for this setup at full engine load.

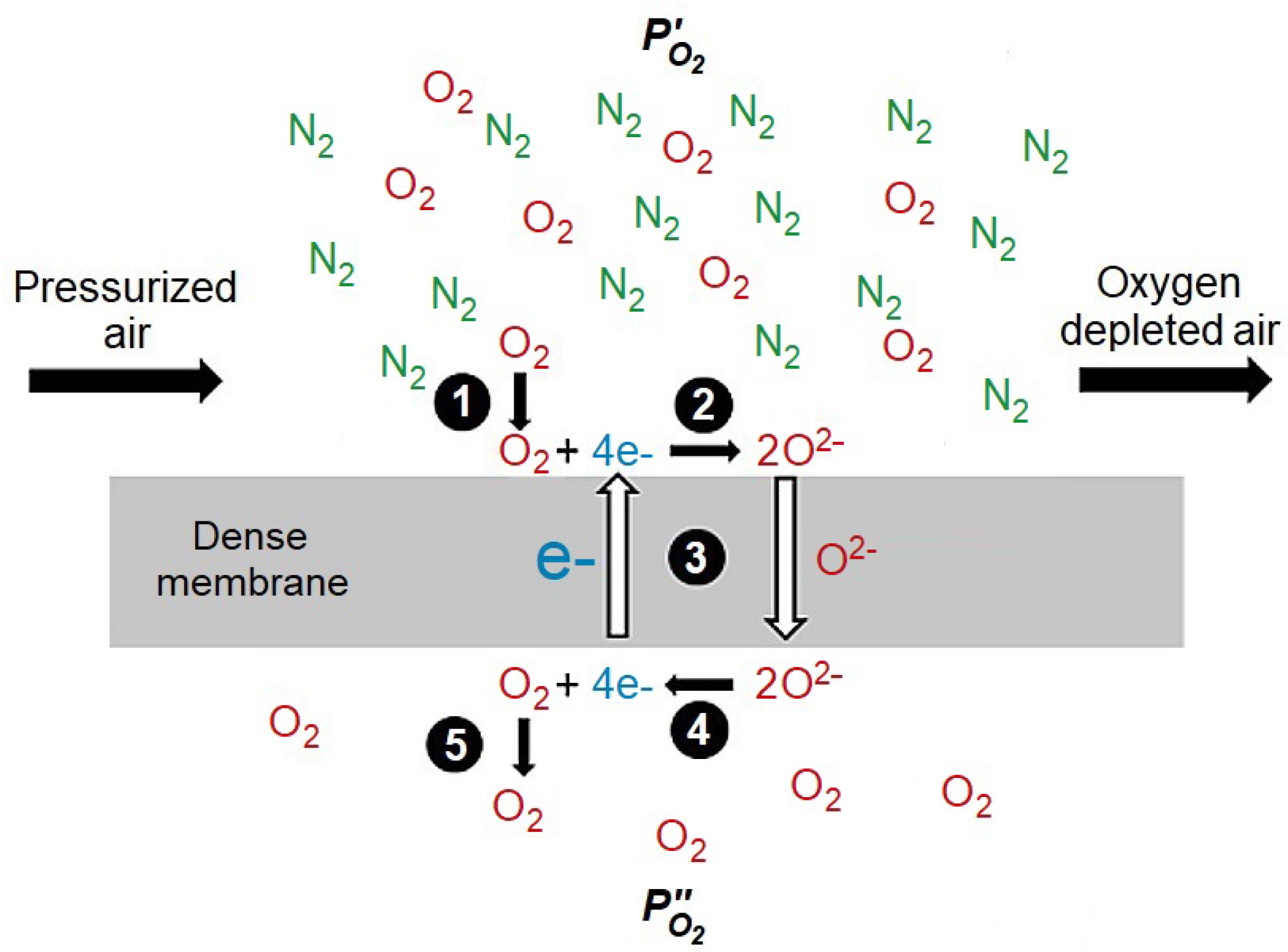

2.3.3.1 MIEC Membrane:

3. Results and Discussion

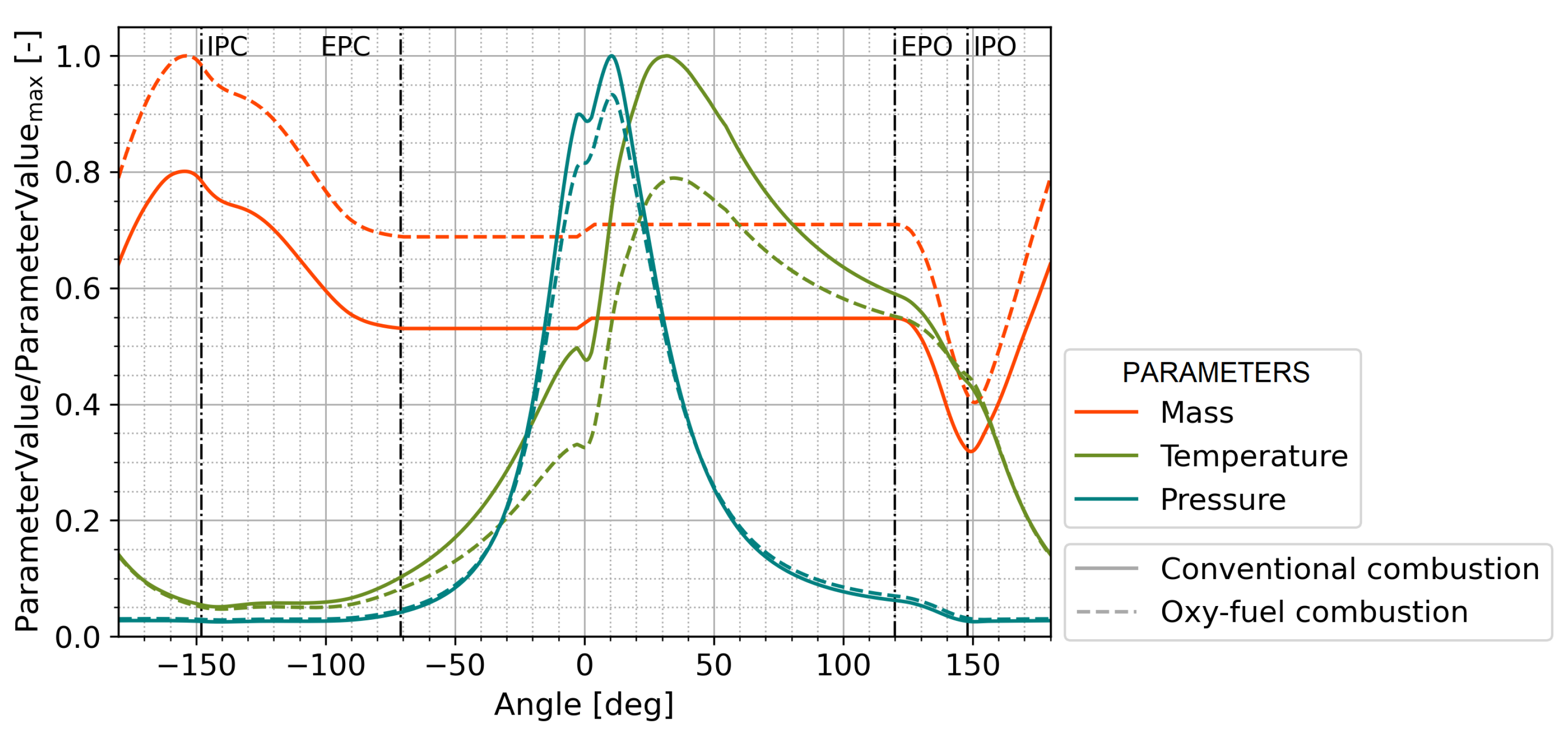

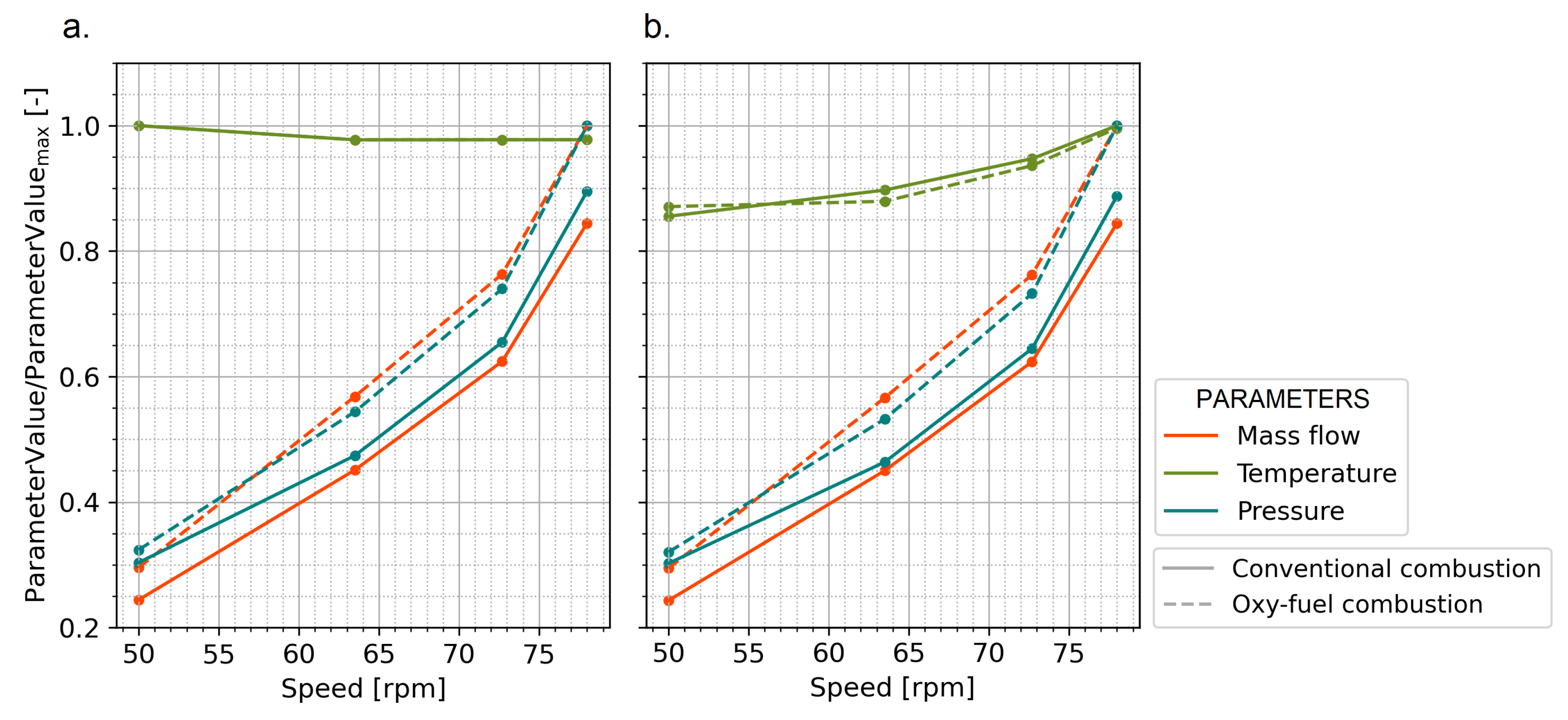

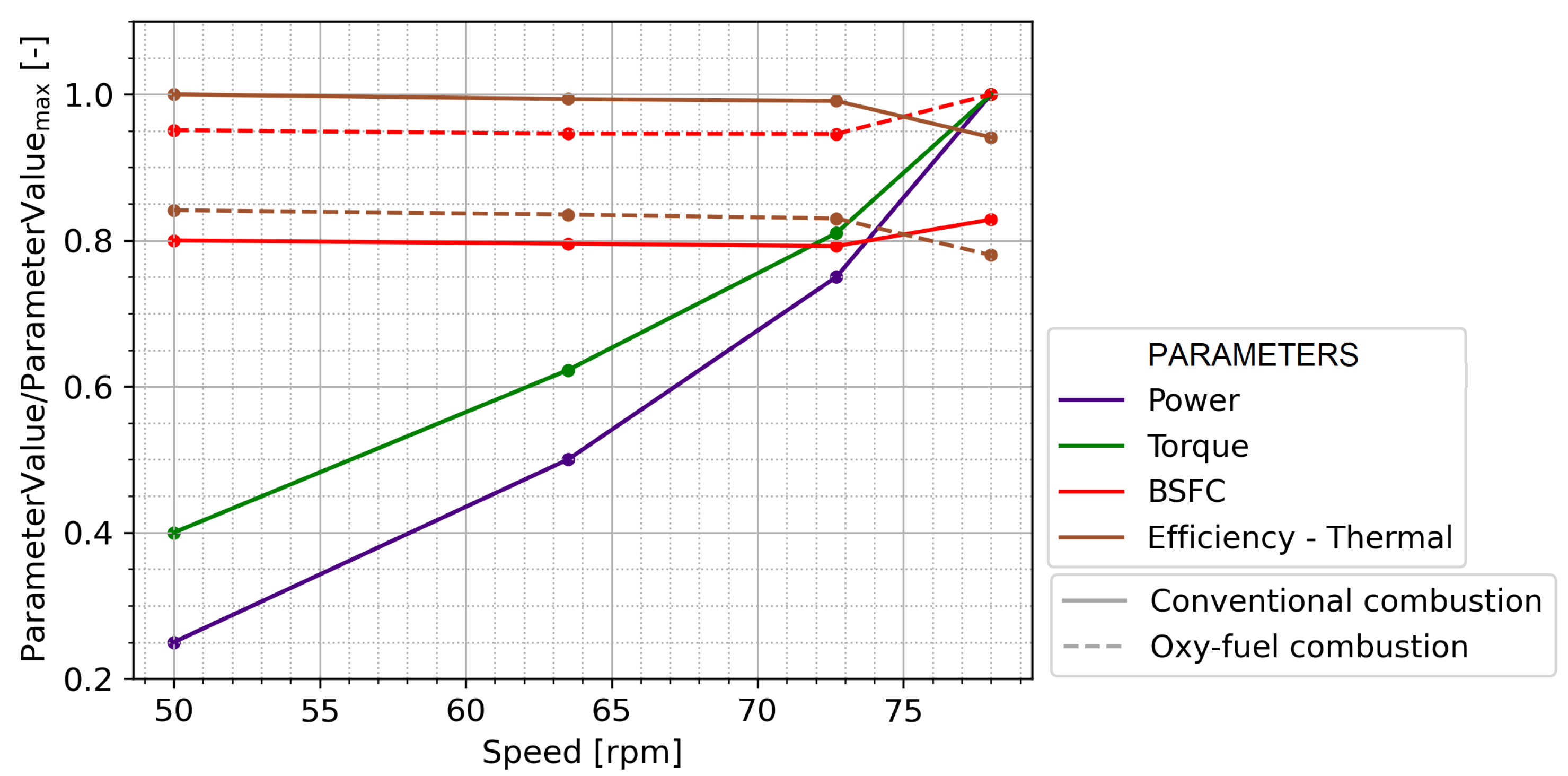

3.1. Engine Behavior under Oxy-Fuel Combustion

3.2. O Production System Design Process Results

3.2.1. Turbocharging System

-

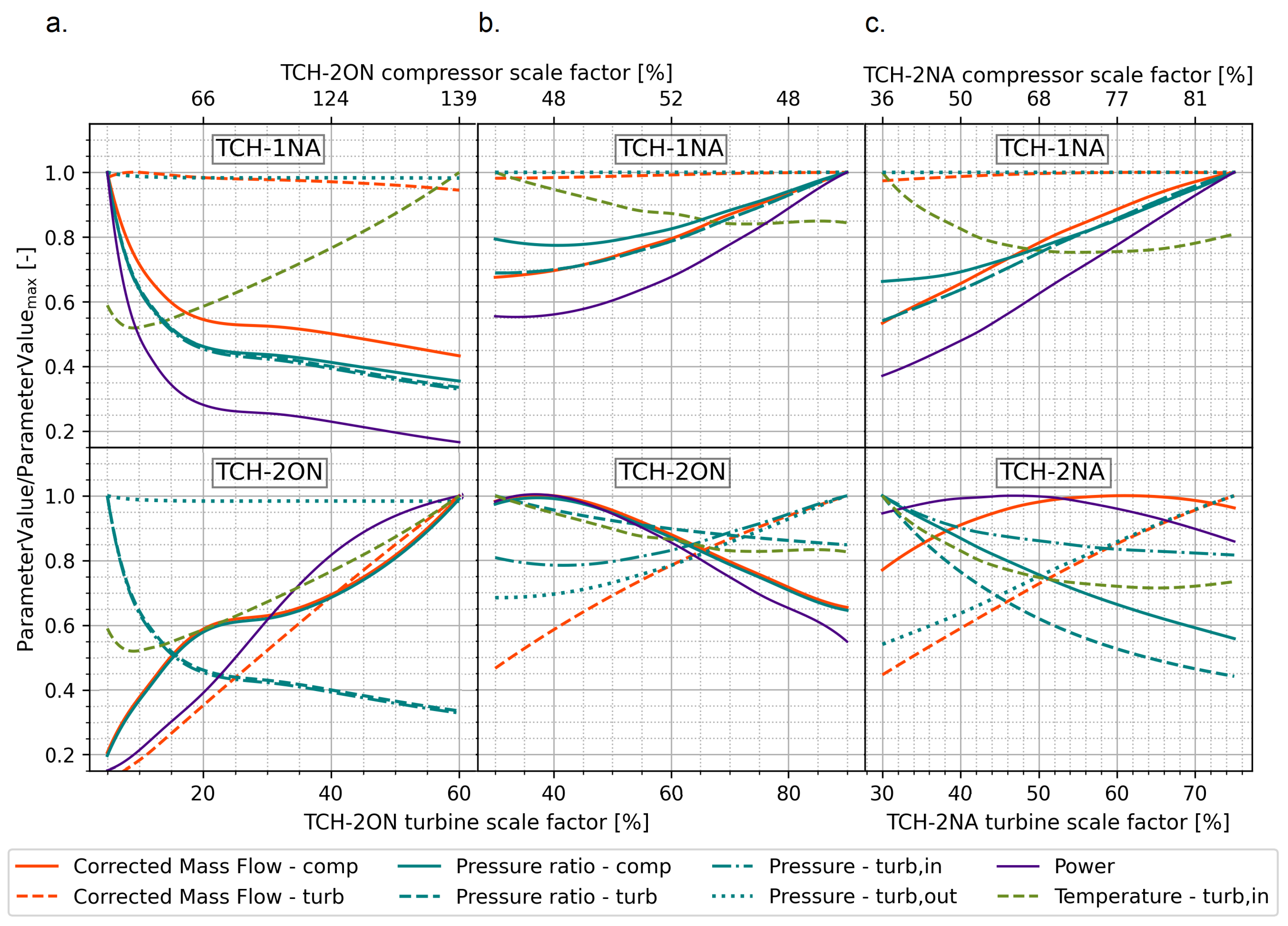

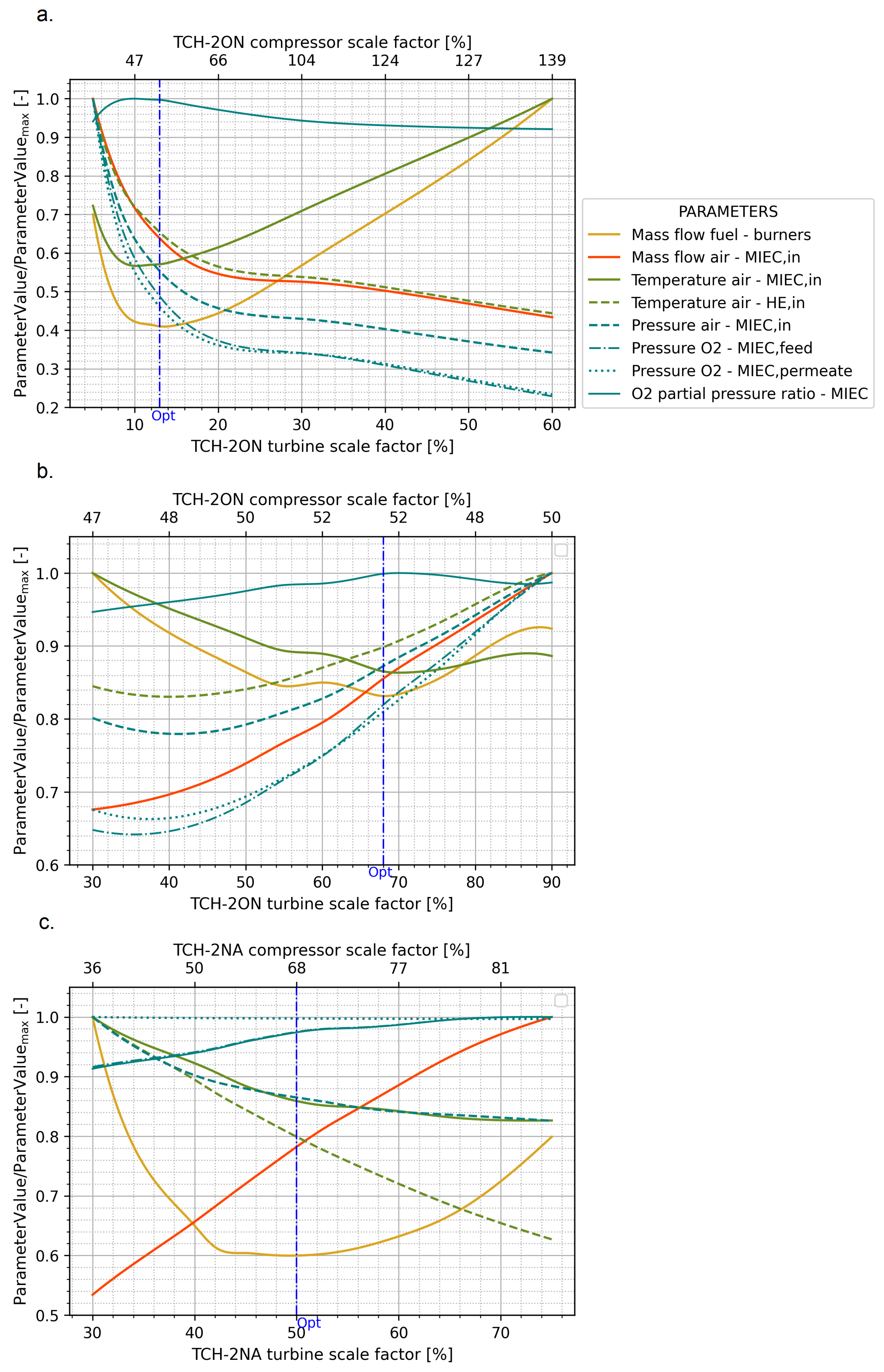

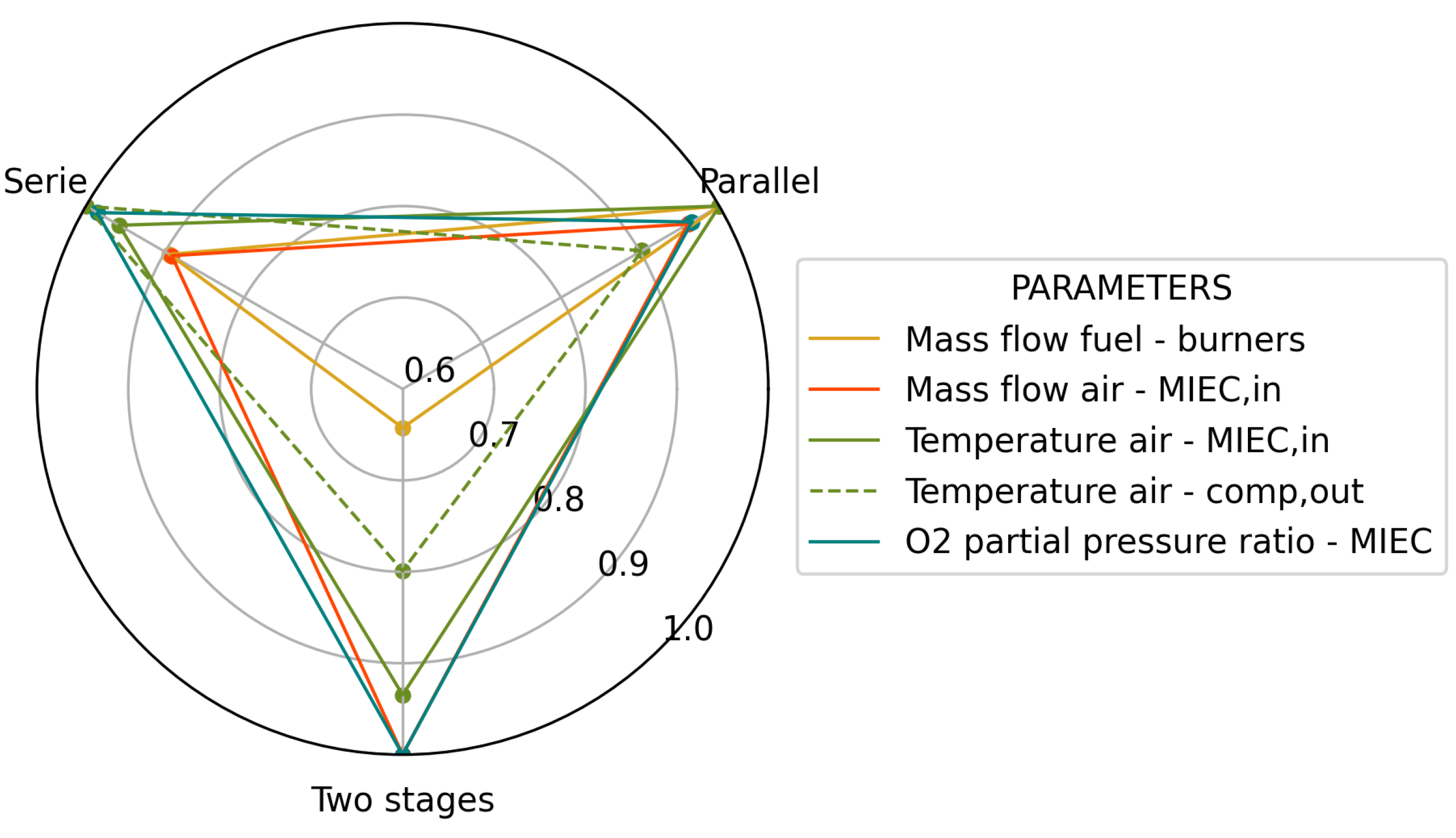

Parallel configuration (Figure 4): When the turbochargers are connected in parallel, the turbines share the N inlet line, so it must be divided so that each receives a part of the flow. If the turbines are of the same size, both suck in equal amounts of N, but if one of them is smaller it receives less. This characteristic in parallel arrangement explains the evolution of the behavior in the turbochargers when performing the size sweep of the TCH-2NA turbo (see Figure 10.a). The TCH-1NA turbocharger has a predictable tendency, as more N corrected mass flow through the turbine, the more speed, power and, therefore, pressure ratio the turbine and compressor have; however, the same is not true for the TCH-2ON turbocharger because, besides the N flowing through, there are other factors affecting its performance. As Table 3 presents, the pressure ratio in TCH-2ON turbine increases because the rise of the pressure ratio in TCH-1NA compressor leads to a higher pressure of N flowing out of the MIEC, however, its temperature is lower due to the drop in fuel consumption (see Figure 11.a); as a result of these conditions in the N coming out of the MIEC, the THC-2ON turbocharger power decreases.After this analysis of turbocharging variation, it is possible to explain the effect on MIEC operation and fuel burner expenditure in parallel configuration (Figure 11.a). The increase in power and pressure ratio of TCH-1NA turbocharger entails an increase in the air mass flow coming in the system and in the air pressure after compression, thus contributing to the increment in the O partial pressure on the feed side. On the other hand, the decrease in THC-2ON turbocharger power causes a lower suction in the O flow line and thus to a higher O partial pressure on the permeate side. Despite the latter, the ratio of O partial pressures in the MIEC increases because the growth rate of the partial pressure on the feed side is higher than on the permeate side until it reaches 10 % of the turbine scale factor beyond which the tendency is opposite. The lowest fuel consumption is around 12.5% of the TCH-2NA turbine scale factor, in the range where the ratio of O partial pressures is maximum, and within this, where the temperature of the air entering the MIEC is higher.

-

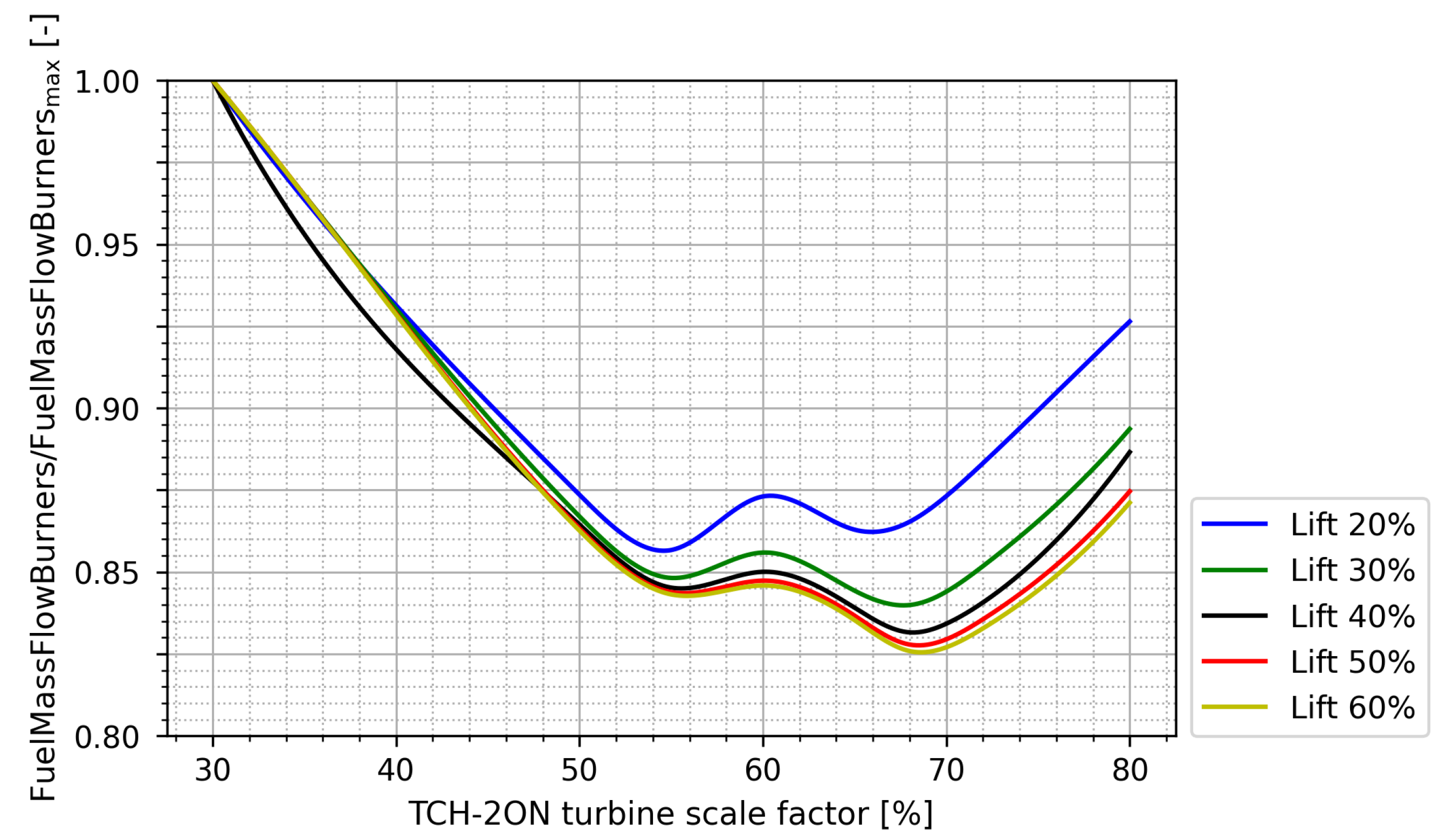

Serial configuration (Figure 5): When the turbochargers are placed in series, the larger one (low pressure turbine) always receives all the N flow entering the turbocharging system, while the smaller one (high pressure turbine) could be by-passed to regulate the flow boosting the turbine and thus to avoid working out of range. In this case the TCH-2ON turbocharger is by-passed, for which a sweep of the valve lift with respect to the turbine scale factor was performed to establish the lift that implies the lowest fuel consumption. Figure 12 displays this sweep for openings between 20% and 60%, since in this interval the turbocharger works properly. As can be seen the lifts from 40% to 60% are very close and present the lowest fuel consumption, independently of the turbine scale factor, so the selected one is 50% to avoid being at the limit of the range.Continuing with the analysis of the serial turbocharging system, as the N mass flow through TCH-2ON turbine decreases by its size reduction, there is less suction in the N line leaving the MIEC, thus slightly decreasing the mass flow passing through the TCH-1NA turbine; for this reason the behavior of the TCH-1NA turbocharger is opposite to the manifested by the parallel arrangement. As for the TCH-2ON turbocharger, examining Figure 10.b and Table 3, it is evident that the pressure ratio in the turbine increases even though the inlet pressure decreases, which occurs because the outlet pressure also drops, but at a higher rate. This increment in the pressure ratio and temperature of the flow entering TCH2-ON turbine results in an increase in the power output of the TCH-2ON turbocharger.Regarding the MIEC operating conditions and fuel consumption, the declined performance of TCH-1NA turbocharger implies a decrease in the air mass flow drawn from the atmosphere and in the air pressure after compression, leading to a lower O partial pressure on the membrane feed side. The improved power of TCH-2ON generates a higher vacuum in the O flow line and, consequently, a decrease in the O partial pressure on the permeate side. Despite the decrease in O2 partial pressures on both membrane sides, the ratio between them depends on the rate of decrease of one with respect to the other. As evidenced in Figure 11.b, from 72% to 68% of turbine scale factor, the slopes of both curves are almost equal, and from the last point the slope of the partial pressure on the feed side is greater than on the permeate; for this reason the O partial pressure ratio increases up to this range and then decreases. The lowest fuel consumption is found at 68% of the TCH-2NA turbine scale factor, in the range where the ratio of O partial pressures is maximum, and within this, where the temperature of the air entering the MIEC is higher, as concluded in the previous parallel configuration.

-

Two stage air compression (Figure 6): The third turbocharging configuration studied is another serial arrangement but, in this case, the two turbochargers work in full serial mode (i.e. no by-pass valve) and both are located in the air flow line to obtain the O partial pressure gradient in the MIEC by compressing only the fluid going to the feed side. Since this configuration has the operating principle of the previous one, the TCH-1NA turbo has the same tendency in performance variation (Figure 10.c). Nevertheless, the TCH-2NA turbocharger power first improves due to the increase in the pressure ratio and temperature of N entering TCH-2NA turbine, but later decreases due to the corrected mass flow decrease. It is worth noting that, this time, the pressure ratio increases due to the rise in the inlet pressure of TCH-2NA turbine caused by the conditions produced in the MIEC; in addition to the significant decrease in the inlet pressure of TCH-1NA turbine (outlet of TCH-2NA turbine).Although the turbochargers behavior in this case is very similar to the past one, the MIEC and fuel consumption are different. The reason is that the cooler between the compression stages leads to a lower air temperature after the turbocharging system compared to the other designs studied (it can be seen in Figure 13), so now the main purpose of the burners is to heat the air up to the MIEC requirement instead of increasing the O partial pressure ratio, because the two stage air compression is high enough to reach a very good outlet air pressure. This change in the burners operating objective explains why the EGR line burner is not needed for this configuration at full engine load and the exhaust gases line burner is sufficient to heat the air to the required value at the MIEC. The lowest fuel consumption is obtained when the TCH-2NA turbine scale factor is around 50% where the temperature of air entering the MIEC is high enough without further reduction of O partial pressure ratio in the MIEC.

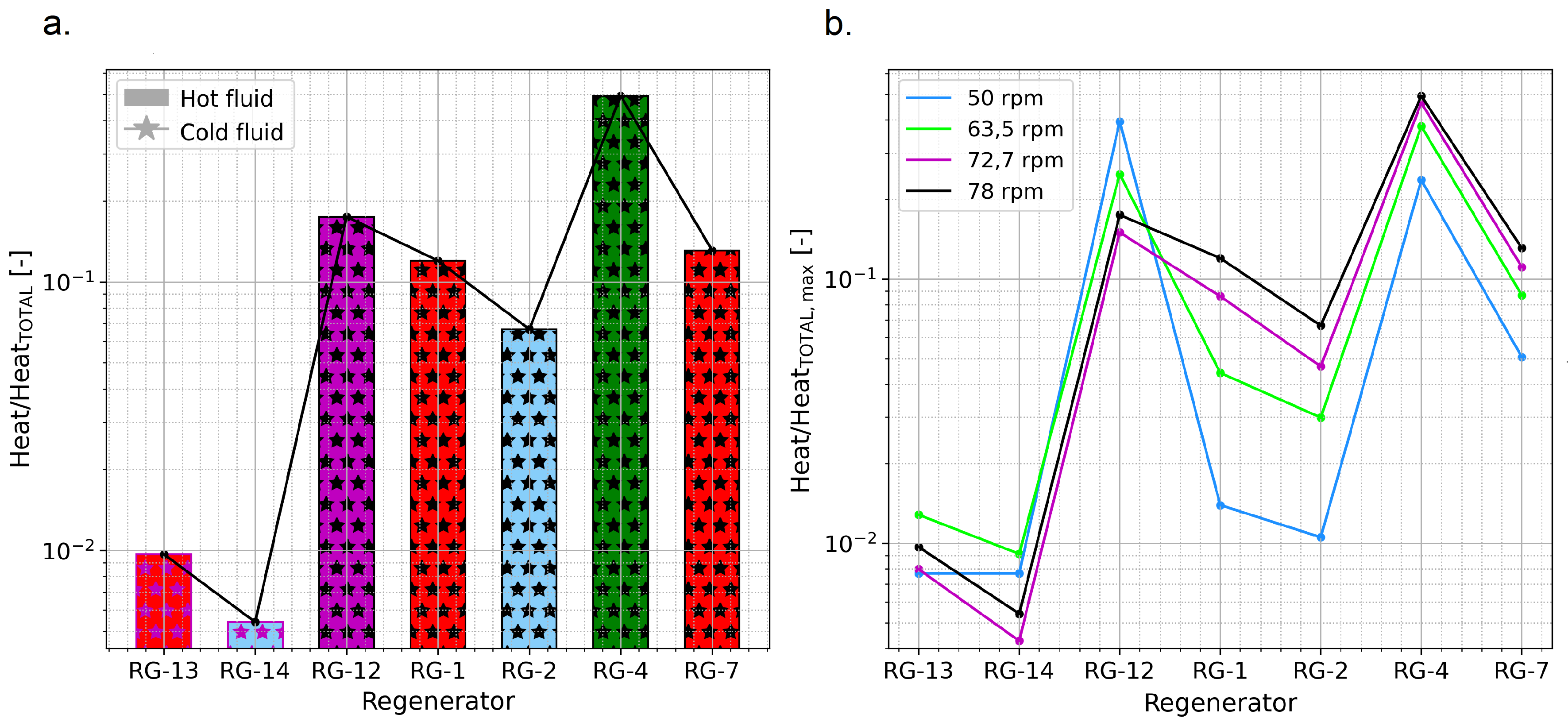

3.2.2. Heat Exchanger System

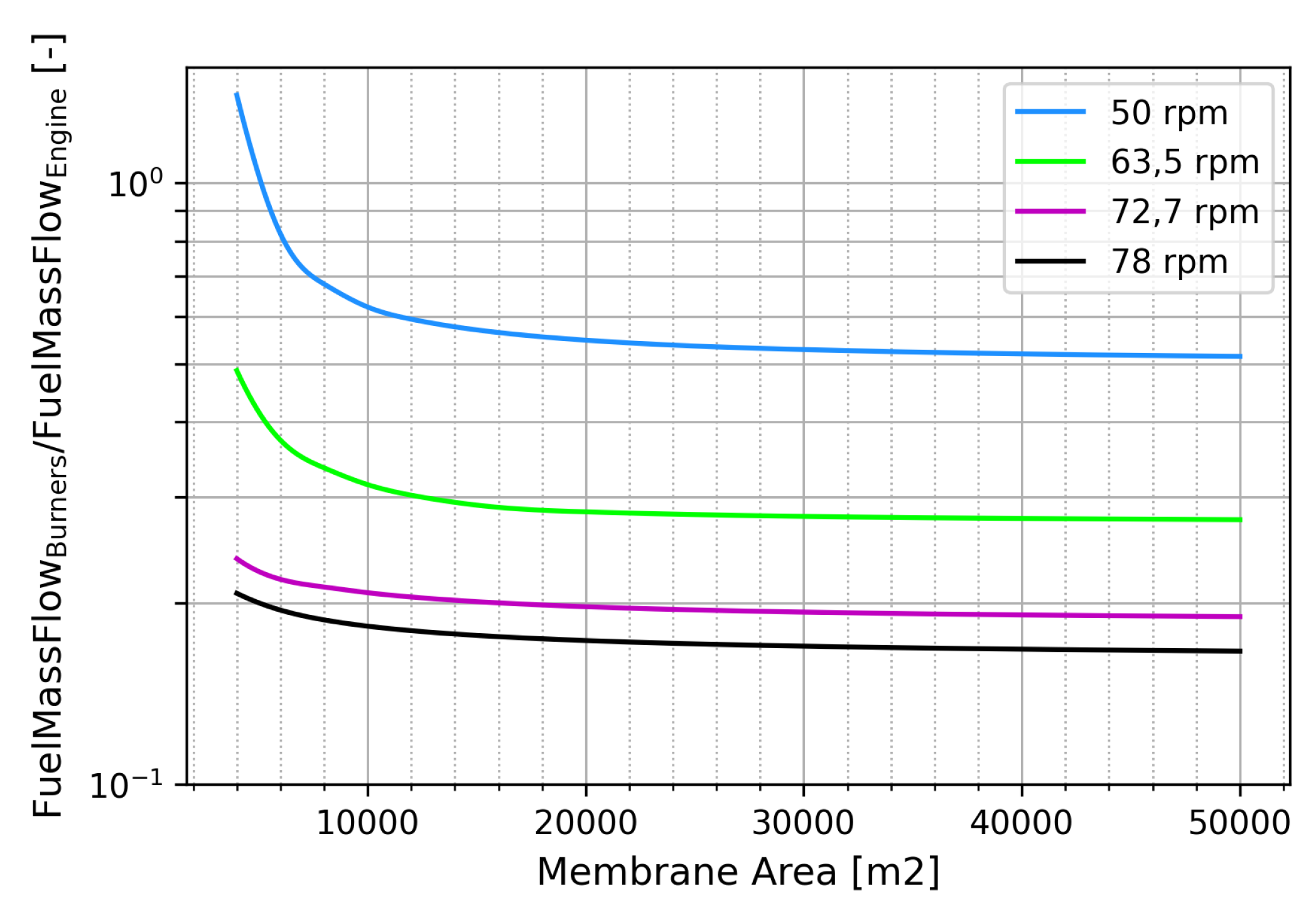

3.2.3. MIEC Membrane

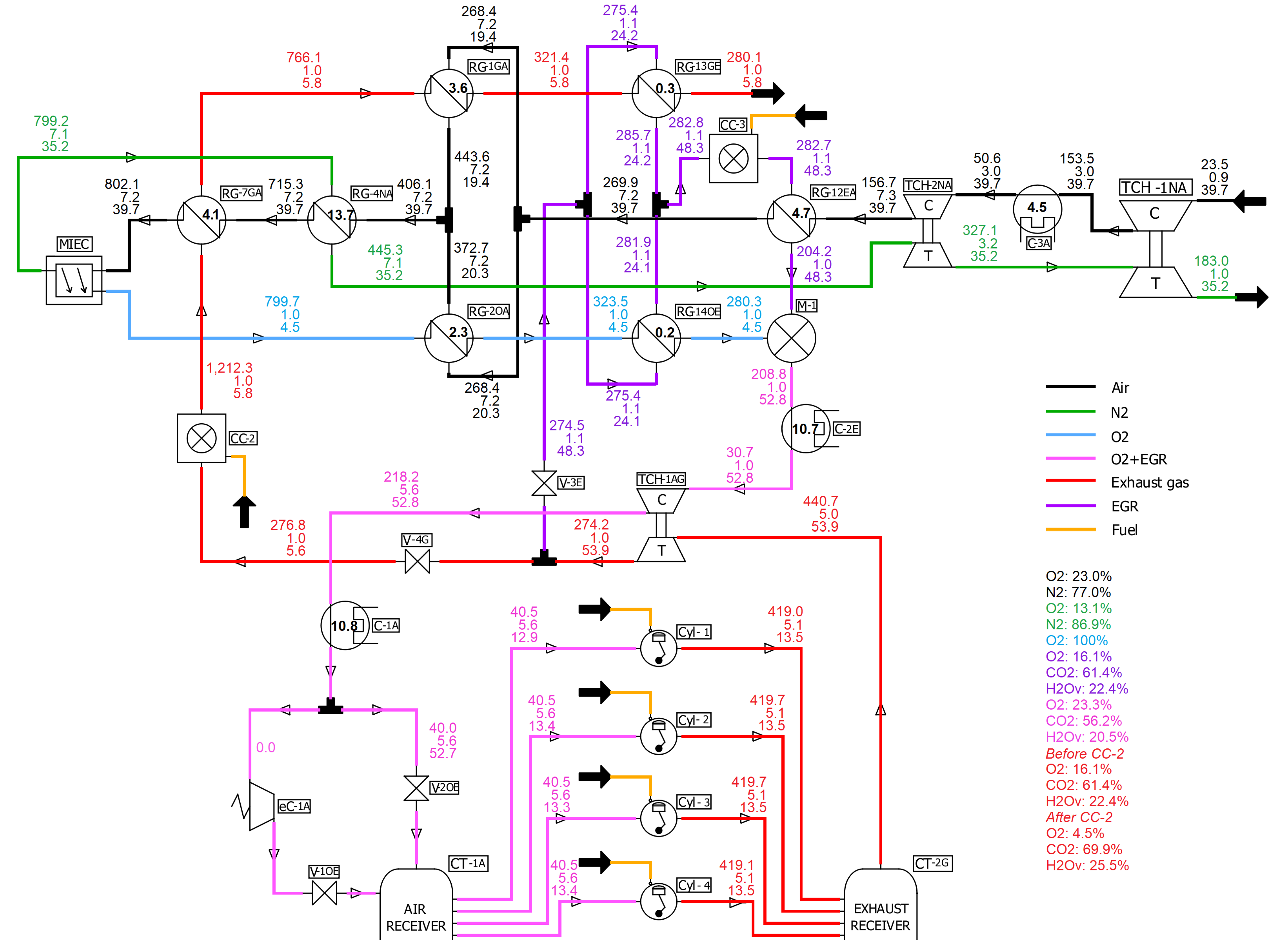

3.3. Conclusive Oxy-Fuel Marine Engine Layout

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2SE | Two Stroke Engine |

| BMEP | Break Mean Effective Pressure |

| BOF | Basic Oxygen Furnace |

| BSCF | BaSrCoFeO membrane |

| BSFC | Break Specific Fuel Consumption |

| CAC | Compressed Air Cooler |

| C-ASU | Cryogenic Air Separation Unit |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CI | Compression Ignition |

| CMCR | Contracted Maximum Continuous Rated |

| CO | Carbon Dioxide |

| DPF | Diesel Particulate Filter |

| ECA | Emission Control Areas |

| EGR | Exhaust Gas Recirculation |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HFO | Heavy Fuel Oil |

| HVOF | High Velocity Oxy-Fuel |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| m/m | mass by mass |

| MARPOL | Marine and Pollution |

| MDO | Marine Diesel Oil |

| MIEC | Mixed Ionic-Electronic Conducting Membrane |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NOx | Nitrous Oxides |

| O | Oxygen |

| ODS | Ozone Depleting Substances |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| SCR | Selective Catalytic Reduction |

| SOx | Sulphur Oxides |

| VGT | Variable Geometry Turbine |

| VEMOD | Virtual Engine Model |

References

- International Maritime Organization. Marine Environment. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- International Maritime Organization. Introduction to IMO. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- International Maritime Organization. Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) – Regulation 13. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/Pages/Nitrogen-oxides-(NOx)-Regulation-13.aspx.

- International Maritime Organization. Initial IMO GHG Strategy. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/pages/reducing-greenhouse-gas-.

- Deng, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z. A review of NOx and SOx emission reduction technologies for marine diesel engines and the potential evaluation of liquefied natural gas fuelled vessels. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aakko-Saksa, P.T.; Lehtoranta, K.; Kuittinen, N.; Järvinen, A.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johnson, K.; Jung, H.; Ntziachristos, L.; Gagné, S.; Takahashi, C.; Karjalainen, P.; Rönkkö, T.; Timonen, H. Reduction in greenhouse gas and other emissions from ship engines: Current trends and future options. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einbu, A.; Pettersen, T.; Morud, J.; Tobiesen, F.; Jayarathna, C.; Skagestad, R.; Nysæter, G. Onboard CO2 Capture From Ship Engines. SSRN Electronic Journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignard, D.; Pritchard, C. Processes for the Synthesis of Liquid Fuels from CO2 and Marine Energy. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2006, 84, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Pei, Y.; Ajmal, T.; Rana, K. J.; Aitouche, A.; & Mobasheri, R. Oxy-fuel combustion for carbon capture and storage in internal combustion engines – A review. International Journal of Energy Research 2022, 46, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhre, B. J. P.; Elliott, L. K.; Sheng, C. D.; Gupta, R. P.; Wall, T. F. Oxy-fuel combustion technology for coal-fired power generation. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2005, 31, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Manovic, V.; & Hanak, D. P. Techno-economic assessment of coal- or biomass-fired oxy-combustion power plants with supercritical carbon dioxide cycle. Energy Conversion and Management 2020, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomen, E.; Hendriksa, C.; Neele, F. Capture technologies: improvements and promising developments. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A. I.; Espatolero, S.; Romeo, L. M. Oxy-combustion power plant integration in an oil refinery to reduce CO2 emissions. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2016, 45, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. M.; Long, H. A. Integration of carbon capture in IGCC systems. Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) Technologies 2017, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Maldonado, F.; Spörl, R.; Fleiger, K.; Hoenig, V.; Maier, J.; Scheffknecht, G. Oxy-fuel combustion technology for cement production - State of the art research and technology development. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2016, 45, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyiklioğlu, O.; Tat, M. E. Tribological assessment of NiCr, Al2O3/TiO2, and Cr3C2/NiCr coatings applied on a cylinder liner of a heavy-duty diesel engine. International Journal of Engine Research 2021, 22, 2267–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quader, M. A.; Ahmed, S.; Ghazilla, R. A. R.; Ahmed, S.; Dahari, M. A comprehensive review on energy efficient CO2 breakthrough technologies for sustainable green iron and steel manufacturing. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Argyle, M. D.; Dellenback, P. A.; Fan, M. Progress in O2 separation for oxy-fuel combustion - A promising way for cost-effective CO2 capture: A review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2018, 67, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panesar, R; Lord., M; Simpson., S; White., V; Gibbins., J; Reddy., S. Coal-Fired Advanced Supercritical Boiler/ Turbine Retrofit with CO2 capture. 8th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, Trondheim, Norway, 19-22 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo, E.; Alonso-Fariñas, B.; Vega, F.; Cano, M.; Navarrete, B. Alternatives for oxygen-selective membrane systems and their integration into the oxy-fuel combustion process: A review. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, S.; Serra, J. M.; Lobera, M. P.; Escolástico, S.; Schulze-Küppers, F.; Meulenberg, W.A. Ultrahigh oxygen permeation flux through supported Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3-δ membranes. Journal of Membrane Science 2011, 377, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, H.J.M.; Burggraaf, A.J. Chapter 10 Dense ceramic membranes for oxygen separation. Membrane Science and Technology 1996, 4, 435–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazaola, A. A.; Labella, A. C.; Liu, Y.; Porras, N. B.; Tanaka, D. A. P.; Annaland, M. V. S.; Gallucci, F. Mixed ionic-electronic conducting membranes (MIEC) for their application in membrane reactors: A review. Processes 2019, 7, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Yang, W.; Cong, Y.; Dong, H.; Tong, J.; Xiong, G. Investigation of the permeation behavior and stability of a Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3-δ oxygen membrane. Journal of Membrane Science 2000, 172, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interreg North-West Europe. RIVER - Non-Carbon River Boat Powered by Combustion Engines. Available online: https://vb.nweurope.eu/projects/project-search/river-non-carbon-river-boat-powered-by-combustion-engines/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Interreg North-West Europe. Oxygen production on the CRT narrowboat in river. Available online: https://www.opteam-network.com/critt/river0220/ (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Interreg North-West Europe. Installation and Integration of an Oxyfuel Combustion Engine System with CO2 Capture and Storage Facilities on a Ship. Available online: https://opteam-network.com/critt/river0920/ (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Mobasheri, R.; Izza, N.; Aitouche, A.; Peng, J.; Bakir, B. Investigation of Oxyfuel Combustion on Engine Performance and Emissions in a DI Diesel HCCI Engine. 8th International Conference on Systems and Control, Marrakech, Morocco, 23-25 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Arnau, F.; Piqueras, P.; Auñon, A. Development of an Integrated Virtual Engine Model to Simulate New Standard Testing Cycles. WCX World Congress Experience, Detroit, USA, 10-12 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ditaranto, M.; Hals, J. Combustion instabilities in sudden expansion oxy–fuel flames. Combustion and Flame 2006, 146, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J. R.; Arnau, F. J.; García-Cuevas, L. M.; Farias, V. H. Oxy-fuel combustion feasibility of compression ignition engines using oxygen separation membranes for enabling carbon dioxide capture. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TIER | CONSTRUCTION DATE | n < 130 | n = 130-1999 | n ≥ 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 January 2000 | 17.0 | 9.8 | |

| II | 1 January 2011 | 14.4 | 7.7 | |

| III | 1 January 2016 | 3.4 | 2.0 |

| Engine speed [rpm] | Load [%] |

|---|---|

| 50 | 25 |

| 63.5 | 50 |

| 72.7 | 75 |

| 78 | 100 |

| ELEMENT | PARAMETER | PARALLEL | SERIAL | TWO STAGES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCH-1 | All except | ↖ | ↙ | ↙ |

| Turbocharger | Temperature IN | |||

| TCH-2 | Corr. mass flow | ↙ | ↖ | ↙ |

| Compressor | Pressure ratio | ↙ | ↖ | ↖ |

| Power | ↙ | ↖ | ↖ | |

| TCH-2 | Corr. mass flow | ↙ | ↙ | ↙ |

| Turbine | Pressure ratio | ↖ | ↖ | ↖ |

| Pressure IN | ↖ | ↙ | ↖ | |

| Pressure OUT | = | ↙ | ↙ | |

| Temperature IN | ↙ | ↖ | ↖ | |

| Power | ↙ | ↖ | ↖ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).