Submitted:

07 August 2023

Posted:

08 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of {[Ni(μ-3isoani)2]·DMF}n (1)

2.2. Synthesis of [Ni(3isoani)2(H2O)4] (2)

2.3. Physical measurements

2.4. X-ray Diffraction Data Collection

2.5. Computational details

3. Results and Discussion

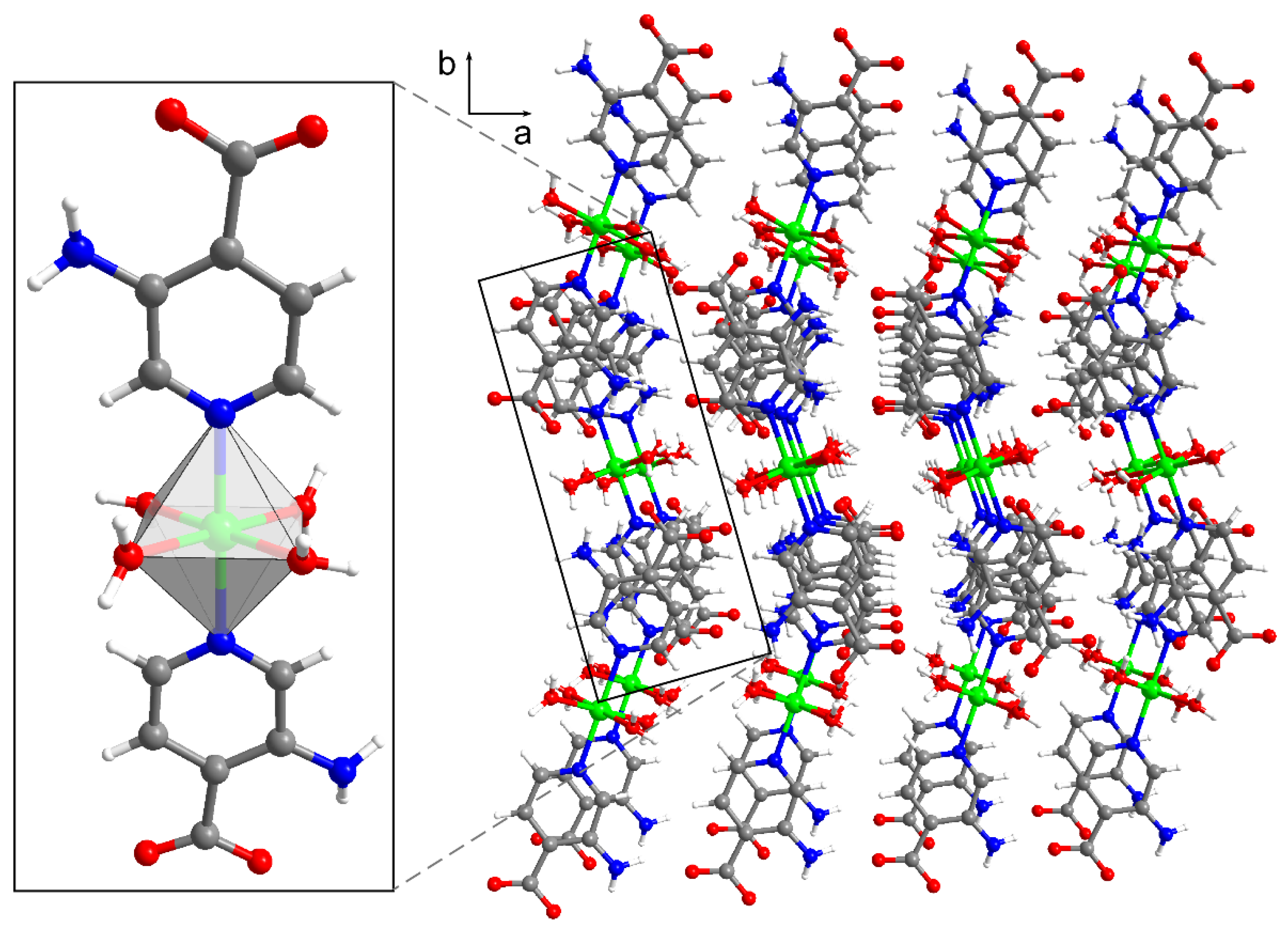

3.1. Structural description of compounds 1 and 2

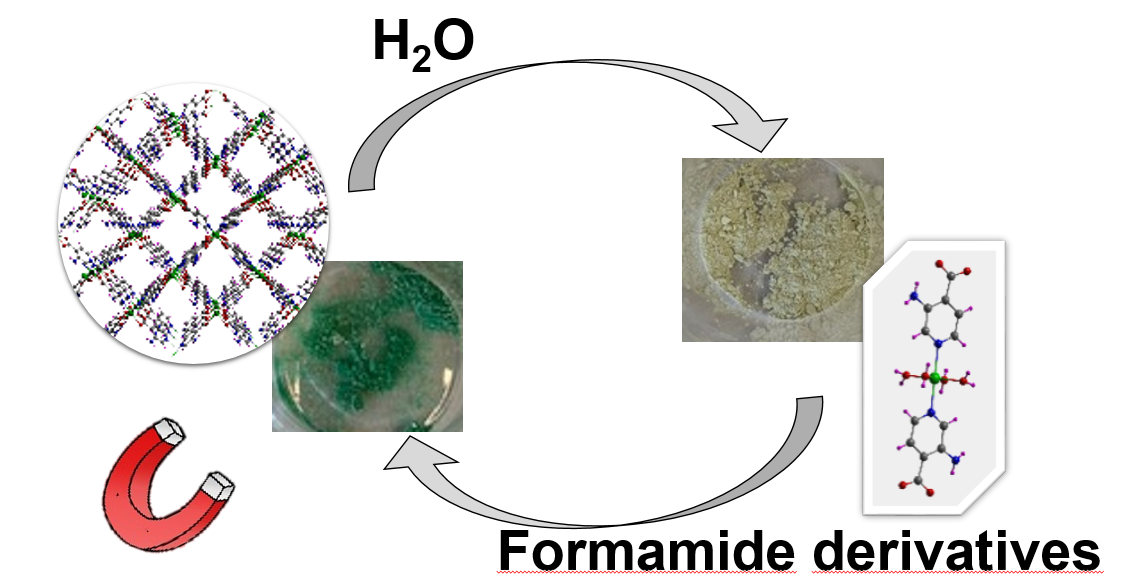

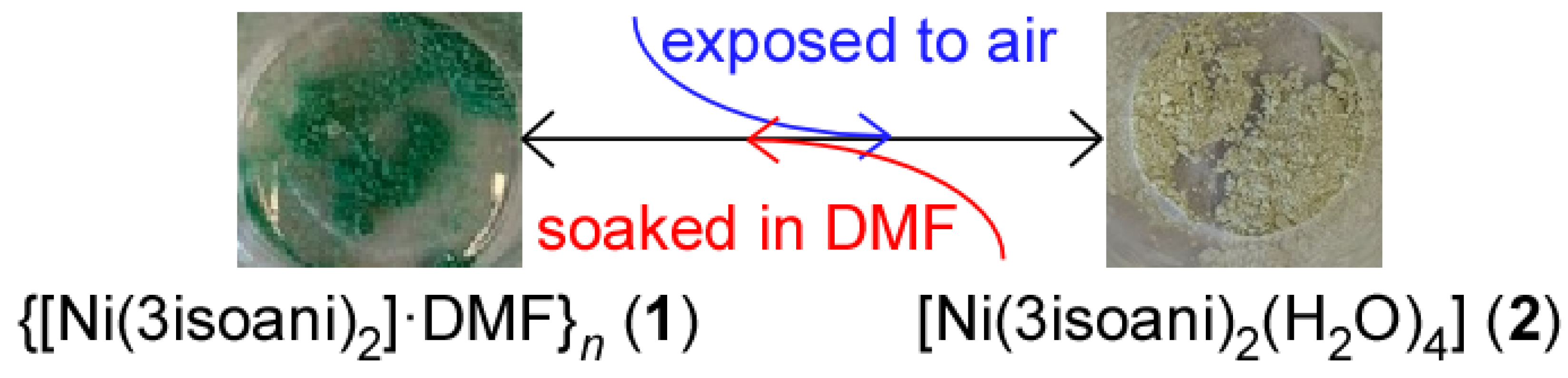

3.2. Structural dynamics of compounds 1 and 2: solid state transformations

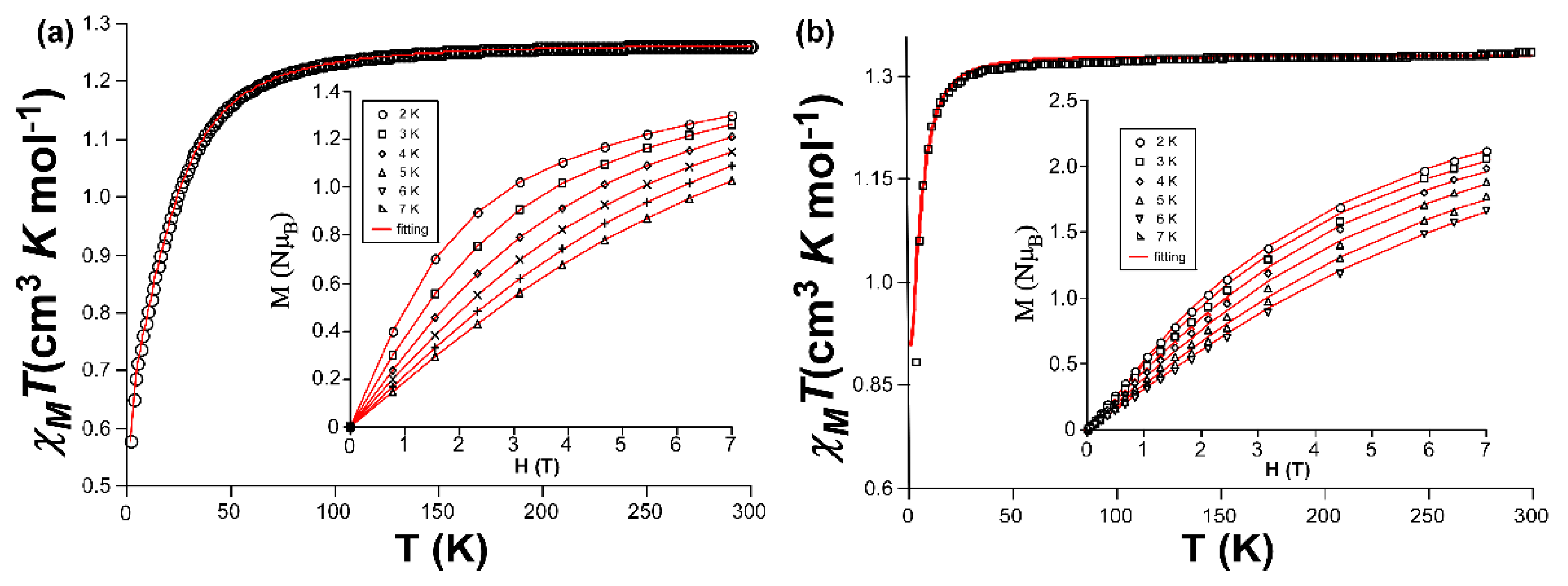

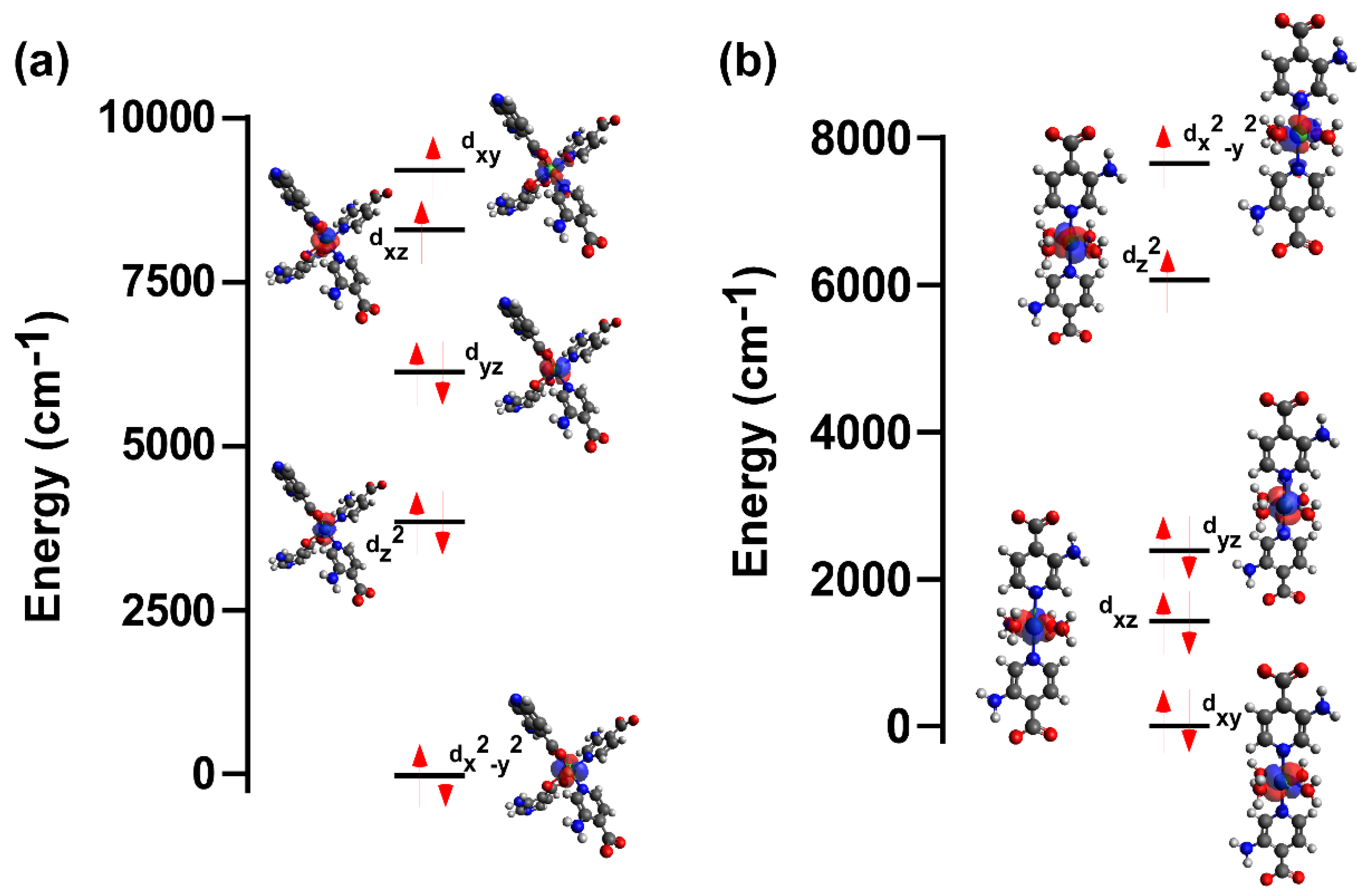

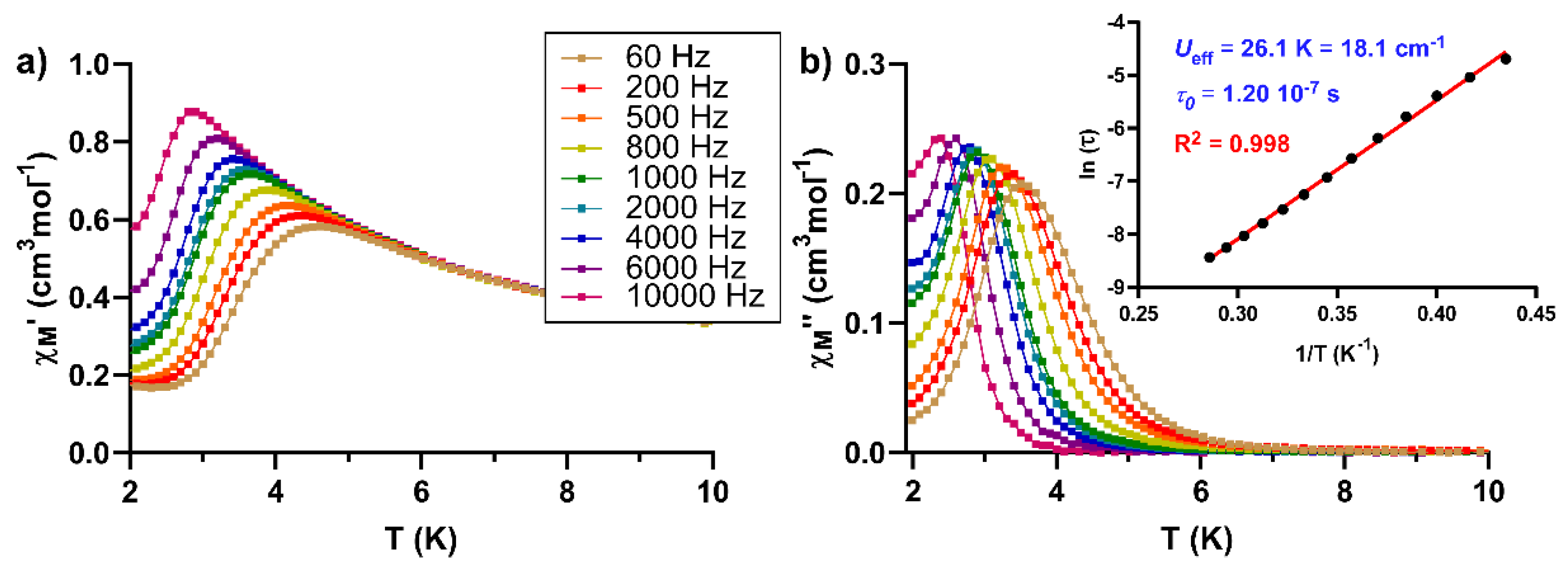

3.3. Magnetic properties of compounds 1 and 2

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiao, L.; Seow, J.Y.R.; Skinner, W.S.; Wang, Z.U.; Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic frameworks: Structures and functional applications. Mater. Today 2019, 27, 43–68. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.R.; Sculley, J.; Zhou, H.C. Metal-organic frameworks for separations. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 869–932. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Lollar, C.T.; Li, J.; Zhou, H.-C. Recent advances in gas storage and separation using metal–organic frameworks. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 108–121. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Cui, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Su, C.Y. Applications of metal-organic frameworks in heterogeneous supramolecular catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6011–6061. [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, J.; Pérez-Mendoza, M.; Calahorro, A.J.; Casati, N.; Seco, J.M.; Aragones-Anglada, M.; Moghadam, P.Z.; Fairen-Jimenez, D.; Rodr\’\iguez-Diéguez, A. Modulation of pore shape and adsorption selectivity by ligand functionalization in a series of {\textquotedblleft}rob{\textquotedblright}-like flexible metal{\textendash}organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Gates, B.C. Catalysis by Metal Organic Frameworks: Perspective and Suggestions for Future Research. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 1779–1798. [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, O.M.; O’Keeffe, M.; Ockwig, N.W.; Chae, H.K.; Eddaoudi, M.; Kim, J. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature 2003, 423, 705–714. [CrossRef]

- Farha, O.K.; Eryazici, I.; Jeong, N.C.; Hauser, B.G.; Wilmer, C.E.; Sarjeant, A.A.; Snurr, R.Q.; Nguyen, S.T.; Yazaydın, A.Ö.; Hupp, J.T. Metal–Organic Framework Materials with Ultrahigh Surface Areas: Is the Sky the Limit? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15016–15021. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wang, K.-Y.; Lv, X.-L.; Yan, T.-H.; Zhou, H.-C. Hierarchically porous metal–organic frameworks: Synthetic strategies and applications. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 1743–1758. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Design strategies for MOF-derived porous functional materials: Preserving surfaces and nurturing pores. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 440–459. [CrossRef]

- Guillerm, V.; Kim, D.; Eubank, J.F.; Luebke, R.; Liu, X.; Adil, K.; Lah, M.S.; Eddaoudi, M. A supermolecular building approach for the design and construction of metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6141–6172. [CrossRef]

- Eddaoudi, M.; Sava, D.F.; Eubank, J.F.; Adil, K.; Guillerm, V. Zeolite-like metal–organic frameworks (ZMOFs): Design{,} synthesis{,} and properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 228–249. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bosch, M.; Gentle, T.; Zhou, H.C. Rational design of metal-organic frameworks with anticipated porosities and functionalities. CrystEngComm 2014, 16, 4069–4083. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-L.; Makal, T.A.; Zhou, H.-C. Interpenetration control in metal–organic frameworks for functional applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2232–2249. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-N.; Zhong, D.-C.; Lu, T.-B. Interpenetrating metal–organic frameworks. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 2596–2606. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, B.; Beobide, G.; Sanchez, I.; Carrasco-Marin, F.; Seco, J.M.; Calahorro, A.J.; Cepeda, J.; Rodriguez-Dieguez, A. Controlling interpenetration for tuning porosity and luminescence properties of flexible MOFs based on biphenyl-4,4 ’-dicarboxylic acid. Crystengcomm 2016, 18, 1282–1294. [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Wu, X.; Han, X.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y. Rational synthesis of interpenetrated 3D covalent organic frameworks for asymmetric photocatalysis. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1494–1502. [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, M.; Nabipour, H.; Valizadeh, N.; Mozafari, M. Chapter 5 - The role of flexibility in MOFs. In Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications; Mozafari, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2020; pp. 93–110 ISBN 978-0-12-816984-1. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Tsang, S.C.E.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. Structural heterogeneity and dynamics in flexible metal-organic frameworks. Cell Reports Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100544. [CrossRef]

- Garcı́a-Valdivia, A.A.; Pérez-Mendoza, M.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Cepeda, J.; Fernández, B.; Souto, M.; González-Tejero, M.; Garcı́a, J.A.; Espallargas, G.M.; Rodrı́guez-Diéguez, A. Interpenetrated Luminescent Metal–Organic Frameworks based on 1H-Indazole-5-carboxylic Acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 4550–4560. [CrossRef]

- Echenique-Errandonea, E.; Rojas, S.; Cepeda, J.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Seco, J.M. Slow Magnetic Relaxation and Modulated Photoluminescent Emission of Coordination Polymer Based on 3-Amino-4-hydroxybenzoate Zn and Co Metal Ions. Molecules 2023, 28, 1846. [CrossRef]

- Castells-Gil, J.; Baldoví, J.J.; Martí-Gastaldo, C.; Mínguez Espallargas, G. Implementation of slow magnetic relaxation in a SIM-MOF through a structural rearrangement. Dalt. Trans. 2018, 47, 14734–14740. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Fernandez-Garcia, G.; Badiane, I.; Camarra, M.; Freslon, S.; Guillou, O.; Daiguebonne, C.; Totti, F.; Cador, O.; Guizouarn, T.; et al. Magnetic Slow Relaxation in a Metal–Organic Framework Made of Chains of Ferromagnetically Coupled Single-Molecule Magnets. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6983–6991. [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, S.; Chastanet, G.; Teat, S.J.; Mallah, T.; Sessoli, R.; Wernsdorfer, W.; Winpenny, R.E.P. Phosphonate Ligands Stabilize Mixed-Valent {MnIII20−xMnIIx} Clusters with Large Spin and Coercivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5044–5048. [CrossRef]

- Aromí, G.; Aguilà, D.; Gamez, P.; Luis, F.; Roubeau, O. Design of magnetic coordination complexes for quantum computing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 537–546. [CrossRef]

- Boča, R. Zero-field splitting in metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 757–815. [CrossRef]

- Bar, A.K.; Pichon, C.; Sutter, J.P. Magnetic anisotropy in two- to eight-coordinated transition–metal complexes: Recent developments in molecular magnetism. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 308, 346–380. [CrossRef]

- Gatteschi, D.; Sessoli, R. Quantum Tunneling of Magnetization and Related Phenomena in Molecular Materials. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 268–297. [CrossRef]

- Fortea-Pérez, F.R.; Vallejo, J.; Mastropietro, T.F.; De Munno, G.; Rabelo, R.; Cano, J.; Julve, M. Field-Induced Single-Ion Magnet Behavior in Nickel(II) Complexes with Functionalized 2,2′:6′-2″-Terpyridine Derivatives: Preparation and Magneto-Structural Study. Molecules 2023, 28, 4423. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.-S.; Jiang, S.-D.; Wang, B.-W.; Gao, S. Understanding the Magnetic Anisotropy toward Single-Ion Magnets. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2381–2389. [CrossRef]

- Baldoví, J.J.; Coronado, E.; Gaita-Ariño, A.; Gamer, C.; Giménez-Marqués, M.; Mínguez Espallargas, G. A SIM-MOF: Three-Dimensional Organisation of Single-Ion Magnets with Anion-Exchange Capabilities. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 10695–10702. [CrossRef]

- Frost, J.M.; Harriman, K.L.M.; Murugesu, M. The rise of 3-d single-ion magnets in molecular magnetism: Towards materials from molecules? Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2470–2491. [CrossRef]

- Miklovič, J.; Valigura, D.; Boča, R.; Titiš, J. A mononuclear Ni(II) complex: A field induced single-molecule magnet showing two slow relaxation processes. Dalt. Trans. 2015, 44, 12484–12487. [CrossRef]

- Pajuelo-Corral, O.; García, J.A.; Castillo, O.; Luque, A.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Cepeda, J. Single-ion magnet and photoluminescence properties of lanthanide(Iii) coordination polymers based on pyrimidine-4,6-dicarboxylate. Magnetochemistry 2021, 7, 8. [CrossRef]

- Razquin-Bobillo, L.; Pajuelo-Corral, O.; Artetxe, B.; Zabala-Lekuona, A.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Sebastian, E.S.; Cepeda, J. Combined experimental and theoretical investigation on the magnetic properties derived from the coordination of 6-methyl-2-oxonicotinate to 3d-metal ions. Dalt. Trans. 2022, 51, 9780–9792. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Dieguez, A.; Perez-Yanez, S.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Seco, J.M.; Cepeda, J. From isolated to 2D Coordination Polymers based on 6-aminonicotinate and 3d-Metal Ions: Towards Field-Induced Single-Ion-Magnets. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 2229–2242. [CrossRef]

- García-Valdivia, A.A.; Seco, J.M.; Cepeda, J.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A. Designing Single-Ion Magnets and Phosphorescent Materials with 1-Methylimidazole-5-carboxylate and Transition-Metal Ions. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 13897–13912. [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, J.; Navas, A.; Jannus, F.; Fernández, B.; Cepeda, J.; O’Donnell, M.M.; Díaz-Ruiz, L.; Sánchez-González, C.; Llopis, J.; Seco, J.M.; et al. Designing Single-Molecule Magnets as Drugs with Dual Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Diabetic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bain, G.A.; Berry, J.F. Diamagnetic Corrections and Pascal’s Constants. J. Chem. Educ. 2008, 85, 532–536. [CrossRef]

- Bruker APEX2; Inc., B.A., Ed.; Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2012.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SADABS empirical absorption program; 1996.

- Sheldrick, G.M. {\it SHELXT} {--} Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with {\it SHELXL}. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O. V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.K.; Puschmann, H. {\it OLEX2}: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B Condens. Matter 1993, 192, 55–69. [CrossRef]

- Rudberg, E.; Sałek, P.; Rinkevicius, Z.; Ågren, H. Heisenberg Exchange in Dinuclear Manganese Complexes: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2006, 2, 981–989. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Cano, J.; Alvarez, S.; Alemany, P. Broken symmetry approach to calculation of exchange coupling constants for homobinuclear and heterobinuclear transition metal complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 1999, 20, 1391–1400. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E.; Rodríguez-Fortea, A.; Cano, J.; Alvarez, S.; Alemany, P. About the calculation of exchange coupling constants in polynuclear transition metal complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 982–989. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian16 {R}evision {C}.01 2016.

- McLean, A.D.; Chandler, G.S. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11–18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 5639–5648. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Weaver, M.N.; Merz, K.M. Assessment of the “6-31+G** + LANL2DZ” Mixed Basis Set Coupled with Density Functional Theory Methods and the Effective Core Potential: Prediction of Heats of Formation and Ionization Potentials for First-Row-Transition-Metal Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 9843–9851. [CrossRef]

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView {V}ersion {6} 2019.

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Becker, U.; Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 224108. [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [CrossRef]

- van Wüllen, C. Molecular density functional calculations in the regular relativistic approximation: Method, application to coinage metal diatomics, hydrides, fluorides and chlorides, and comparison with first-order relativistic calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109, 392–399. [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence{,} triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [CrossRef]

- Hellweg, A.; Hättig, C.; Höfener, S.; Klopper, W. Optimized accurate auxiliary basis sets for RI-MP2 and RI-CC2 calculations for the atoms Rb to Rn. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2007, 117, 587–597. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.-F.; Singh, M.K.; Gan, D.; Xiao, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Dunbar, K.R. Probing the Axial Distortion Effect on the Magnetic Anisotropy of Octahedral Co(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7622–7630. [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.; Borini, S.; Cestari, M.; Cimiraglia, R. A quasidegenerate formulation of the second order n-electron valence state perturbation theory approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 121, 4043–4049. [CrossRef]

- Maganas, D.; Sottini, S.; Kyritsis, P.; Groenen, E.J.J.; Neese, F. Theoretical Analysis of the Spin Hamiltonian Parameters in Co(II)S4 Complexes, Using Density Functional Theory and Correlated ab initio Methods. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 8741–8754. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Yu, C.; Xie, Q.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Hou, H. Porous functionalized MOF self-evolution promoting molecule encapsulation and Hg2+ removal. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 13382–13385. [CrossRef]

- Gantzler, N.; Kim, M.-B.; Robinson, A.; Terban, M.W.; Ghose, S.; Dinnebier, R.E.; York, A.H.; Tiana, D.; Simon, C.M.; Thallapally, P.K. Computation-informed optimization of Ni(PyC)2 functionalization for noble gas separations. Cell Reports Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 101025. [CrossRef]

- Pajuelo-Corral, O.; Pérez-Yáñez, S.; Vitorica-Yrezabal, I.J.; Beobide, G.; Zabala-Lekuona, A.; Rodríguez-Diéguez, A.; Seco, J.M.; Cepeda, J. A metal-organic framework based on Co(II) and 3-aminoisonicotinate showing specific and reversible colourimetric response to solvent exchange with variable magnet behaviour. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 24, 100794. [CrossRef]

- Chilton, N.F.; Anderson, R.P.; Turner, L.D.; Soncini, A.; Murray, K.S. PHI: A powerful new program for the analysis of anisotropic monomeric and exchange-coupled polynuclear d- and f-block complexes. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1164–1175. [CrossRef]

- Titiş, J.; Boça, R. Magnetostructural D correlation in Nickel(II) complexes: Reinvestigation of the zero-field splitting. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 3971–3973. [CrossRef]

| Compound | 1 |

|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C15H17N5NiO5 |

| Formula weight (g mol-1) | 406.04 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pnn2 |

| a (Å) | 11.944(2) |

| b (Å) | 6.740(1) |

| c (Å) | 10.661(2) |

| V (Å3) | 858.2(3) |

| Reflections collected | 6467 |

| Unique data/parameters | 2814/136 |

| Rint | 0.0521 |

| GoF (S)a | 1.075 |

| R1b/wR2 [I > 2σ(I)]c | 0.0410/0.0869 |

| R1b/wR2 [all]c | 0.0486/0.0941 |

| Ni1–O1 | 2.123(2) | Ni1–O2A (i) | 2.081(2) |

| Ni1–O1A (i) | 2.123(2)) | Ni1–N1A | 2.028(3) |

| Ni1–O2A | 2.081(2) | Ni1–N1A (i) | 2.028(3) |

| Compound | Exp. | Calc. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | E/D | giso | D | E/D | g2 | |

| 1 | -17.3(1) | 0.05 | 2.25(1) | -21.1 | 0.07 | 2.24, 2.26, 2.38 (2.27) |

| 2 | -4.8(3) | 0.15 | 2.37(5) | -6.7 | 0.12 | 2.34, 2.35, 2.39 (2.38) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).