3.1. Plasma in diamond

One of the most important problems in the analysis of laser-induced processes and the permanent consequences of these processes is the understanding of the mechanisms of energy dissipation of an intense electromagnetic field in a medium. In the experiments described below, reversible processes in diamond were studied: the process of excitation of the electronic subsystem stimulated by femtosecond irradiation and the process of heating the diamond lattice stimulated by the electron - hole recombination. In these experiments, interferometric microscopy was used to measure the polarizability of diamond under femtosecond laser irradiation and its temporal dynamics.

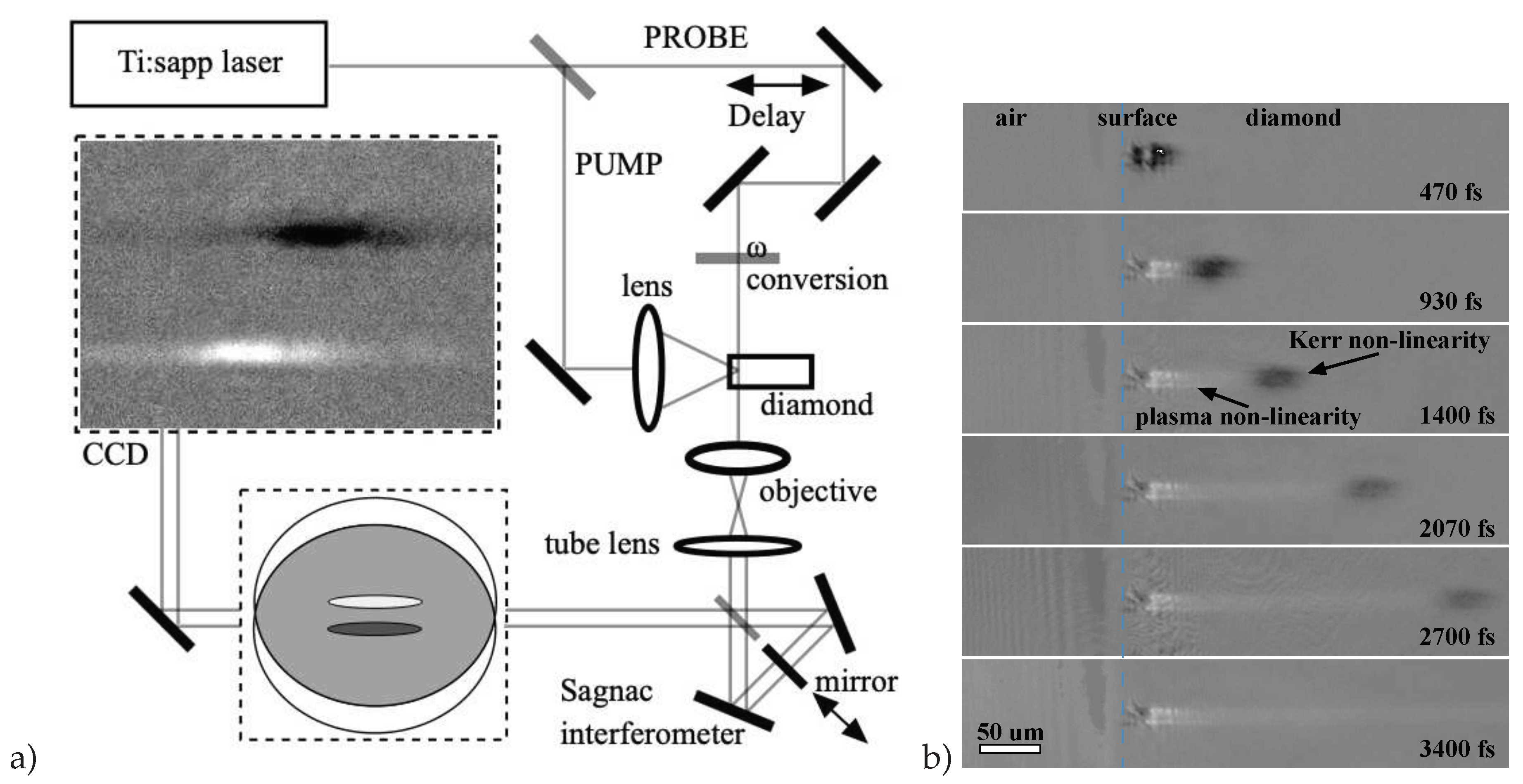

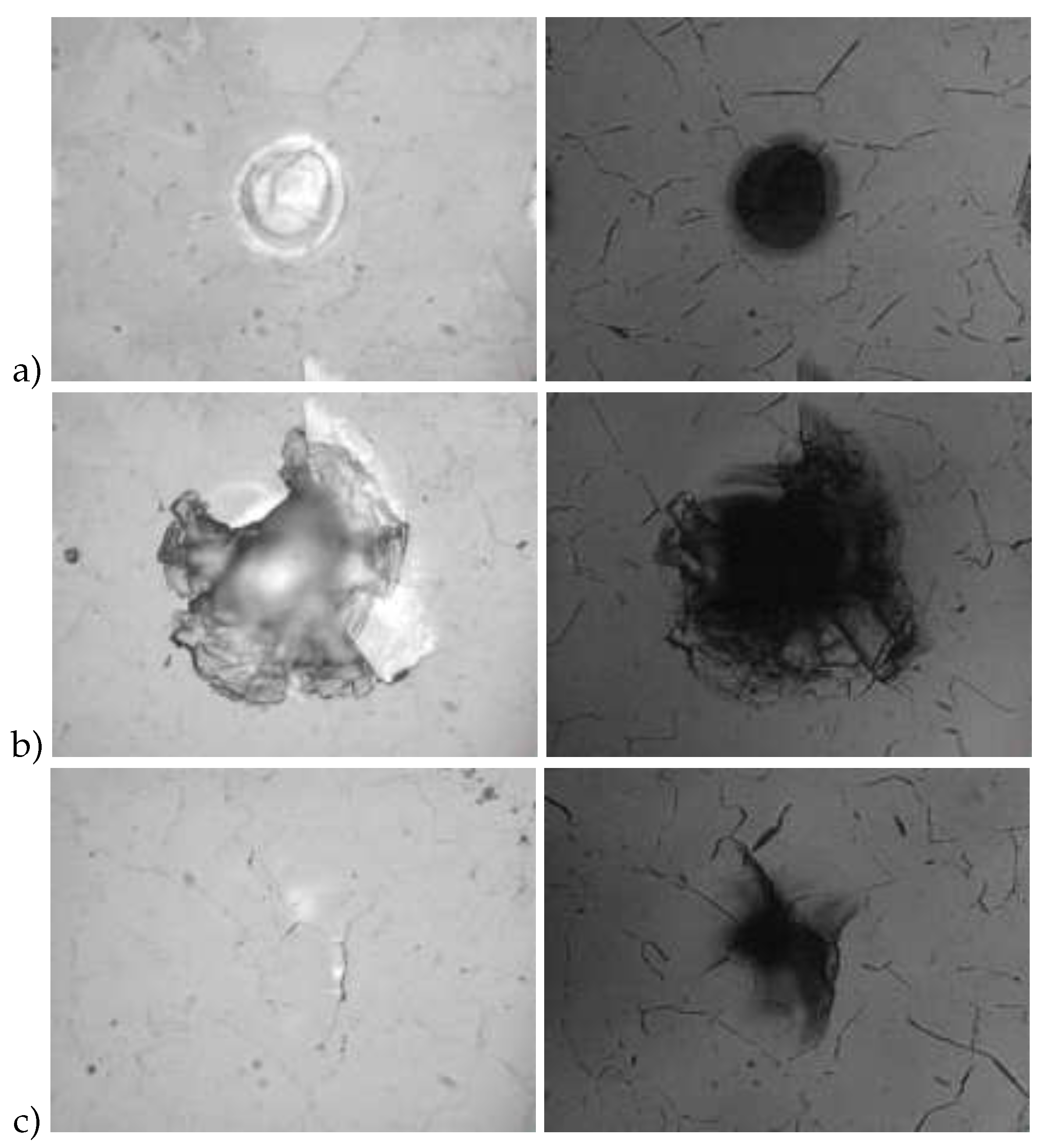

A typical picture of the propagation of a femtosecond laser pulse in the near-surface layer of a diamond sample is shown in

Figure 1b [

44]. The presented series of interference photographs clearly shows that the polarizability of a crystal in a laser caustic varies greatly with time. In the test described the interferometer was tuned so that a decrease in image brightness indicates an increase in the refractive index (dark areas correspond to

), and, on the contrary, an increase in brightness indicates a decrease in the refractive index (light areas correspond to

).

The cloud is clearly seen propagating through the crystal at the speed of light. This image of the light packet arises due to the optical Kerr effect, which locally increases the refractive index of the medium proportionally to the intensity of the radiation: . Further exposure to the laser field results in ionization of the covalent bonds of the crystal and, as a consequence, the appearance of electrons in the conduction band and holes in the valence band (e–h pairs). The appearance of both types of free carriers leads to a proportional decrease in n, which is described in terms of classical concepts by the Drude theory: , where is the refractive index of diamond, is the frequency of the laser radiation, is the effective optical mass of carriers, is their concentration, e and are the electron charge and mass.

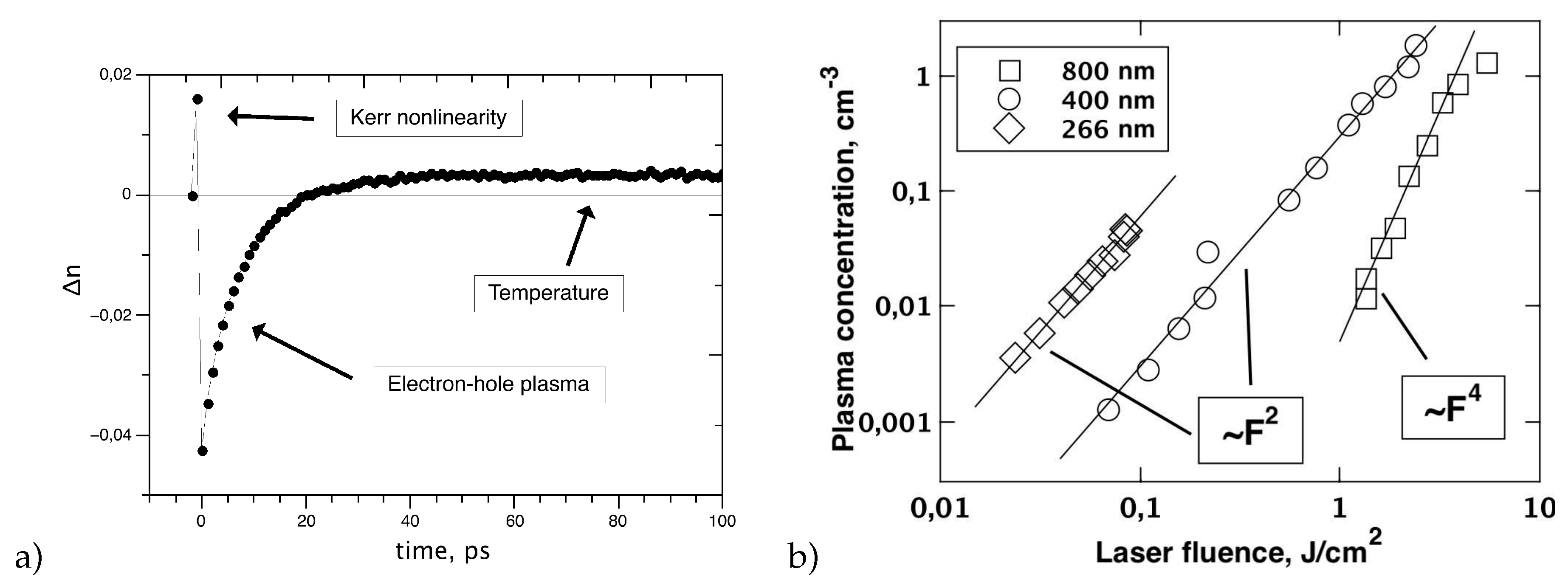

Thus, when intense pulses affect diamond crystal, two mechanisms of light-induced perturbation of the electron subsystem prevail: the optical Kerr effect, which is a manifestation of the anharmonicity of the localized bound electrons, and photoinduced transitions of the electrons, leading to the formation of a free electron-hole plasma. A typical dynamics of

n value over subnanosecond time scale is shown in

Figure 2a. The presented data have allowed to determine the lifetime of the dense electron-hole plasma in diamond, which is about 10 ps. It was also found that after the complete recombination of carriers, approximately 20 ps later, a region with positive

appeared. This induced polarizability slowly decreased with time and after about 40 ns became less than the sensitivity threshold of the measuring system. Simultaneously, the size of the perturbed region gradually increased, so that the integral

over space did not depend on time:

.

The observed long-lived

perturbation was interpreted as diamond heating, which is confirmed by a good agreement between the measured dynamics of the spatial spreading of the perturbed region and the simulated dynamics of heat propagation from the region initially occupied by photoinduced plasma [

44]. A comparison of the experiment and calculation results showed that the heating of the diamond lattice in the pre-ablation regime is relatively low:

. Close estimates of the increase in temperature were obtained from the energy stored in the electron-hole plasma and released as a result of carrier recombination.

Interferometric microscopy also allows to obtain the dependence of the concentration of photoinduced

e–

h pairs on the radiation fluence for all three harmonics of the Ti-sapp laser (

Figure 2b) [

44]. The plasma density was calculated using Drude formalism from the negative change in

n. These data demonstrate that the density of the electron-hole plasma can reach

cm

without damage of the diamond lattice. The absorption has a multiphoton character in a wide dynamic range of laser fluence (up to surface graphitization and destruction). The corresponding dependences are power-law with an exponent of 4 for 800 nm (four-photon transition), 2 - for 400 and 266 nm wavelength (indirect and direct two-photon transitions, respectively). The contribution of the three-photon direct transition at the 400 nm exposure is not detected. The contribution of inverse bremsstrahlung to the excitation of the electronic subsystem is also not observed even for 800 nm irradiation.

The obtained dependences

actually give the quantum yield of phototransitions in diamond and allow us to estimate the M-photon absorption cross sections for all used wavelengths using the formula:

, where

is the photon energy. The calculated

values are given in the

Table 2 in comparison with known literature data.

3.2. Multipulse ablation of diamond

Already in the first experiments on laser destruction of natural diamonds by pulsed radiation it was shown that damage to the diamond surface is accompanied by blackening in the laser affected zone, presumably due to the transformation of diamond into graphite [

15,

46]. Thereafter Rothschild et al. [

14] developed these ideas and pointed out that graphitization is indeed the key feature of diamond ablation. It was shown that when diamond is irradiated with intense UV pulses, two processes occur: the transformation of diamond into graphite and the subsequent evaporation of this graphitized material.

Special attention should be paid here to the fact that graphite is a semi-metal and its absorption in the optical range of the spectrum is orders of magnitude higher than that of diamond. This circumstance leads to a sharp jump in the optical absorption in laser affected zone during the primary formation of the graphite-like layer and, consequently, to different mechanisms of diamond ablation at the stage of formation of the graphite layer and after it. Three situations should be distinguished: (i) graphitization has not yet begun and the radiation energy is absorbed in the diamond, subjecting the relations described in

Section 3.1. In particular, this is always true for the first laser pulse. (ii) If the graphitized carbon phase has formed and completely covers the zone irradiated, the laser energy is dissipated completely in the target and the ablation process resembles the ablation of metals. This is exactly the established regime of multipulse processing that usually refers to "diamond ablation" term. (iii) An intermediate situation is also possible, when the radiation energy is close to the threshold and graphitization is spread over time - a gradual accumulative formation of the graphite layer occurs. In this regime, the role of both multiphoton absorption in diamond and one-photon absorption on "non-diamond" inclusions is important (see

Section 3.4).

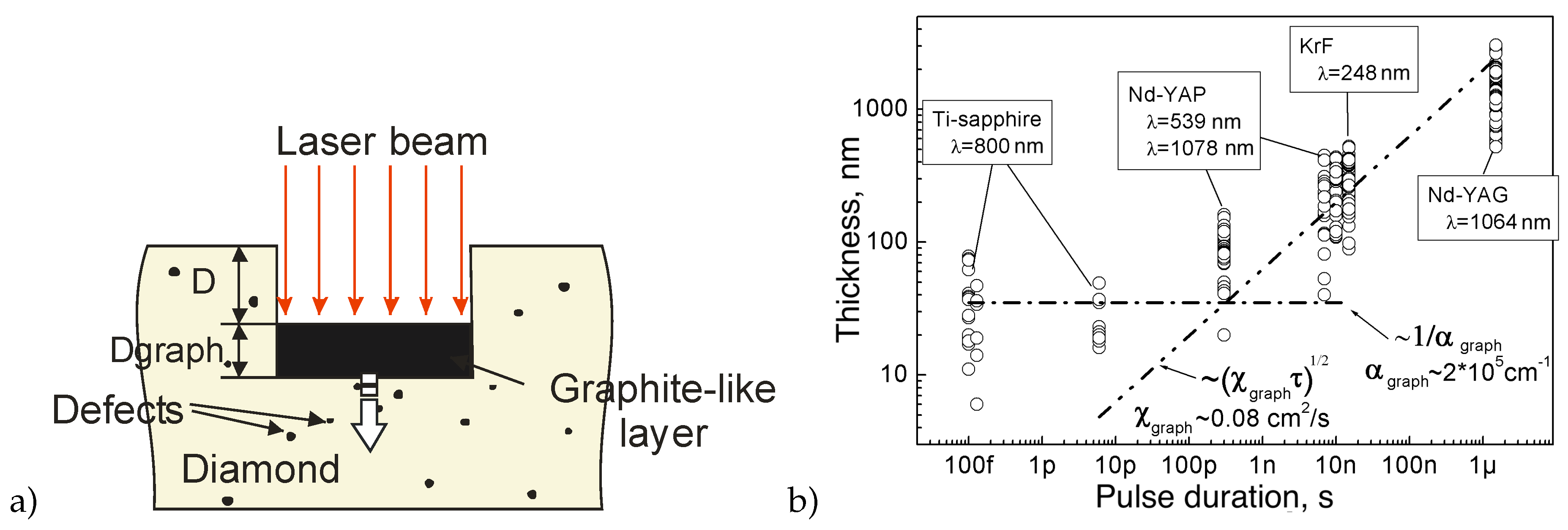

The correctness of the two-stage ablation mechanism (through graphitization and evaporation) was fully corroborated in the later works [

47,

48]. To date, the generally accepted model of the ablation under multipulse irradiation is the "graphite piston" model, which combines the evaporation of graphitized material from the surface and graphitization at the diamond-graphite interface into a single self-consistent process (

Figure 3a). According to this model, the energy of the next laser pulse is completely absorbed in a rather thick graphitized layer and heats it up. As a result, the temperature in the zone affected reaches values higher than the evaporation temperature of graphite, thus removing material from the surface. Simultaneously, the diffusive penetration of heat into the sample increases the temperature of the graphite-diamond interface and initiates the transformation of the next portion of the diamond. In this way the repetitively pulsed laser radiation "push" the "graphite piston" into the diamond plate, involving more and more new diamond layers in the graphitization process.

Studies of the properties of the graphite-like layer formed during multipulse ablation also confirm that diamond ablation is a thermally stimulated process [

48]. In particular, it is shown that the thickness of the graphitized layer varies over a wide range (10 nm

m) depending on the duration of the laser pulse. The layer thickness, as the “graphite piston” model implies, is determined by the depth of the heat-affected zone: for long pulses - by the thermal conductivity of the graphite-like phase; for short pulses (up to femtosecond ones) - by the depth of radiation absorption in this phase. This conclusion was made on the basis of the experimental results and the corresponding assessments of the thickness of the graphitized layer depending on the laser pulse duration (

Figure 3b). The absorption coefficient and thermal conductivity of polycrystalline graphite at a temperature of 2000K (

cm

and

cm

/sec [

49]) were taken as the corresponding values for the graphitized carbon phase. Note, that the influence of the laser wavelength on the layer thickness was found to be illusive: its small variations are rather caused by differences in the pulse duration of the used laser systems.

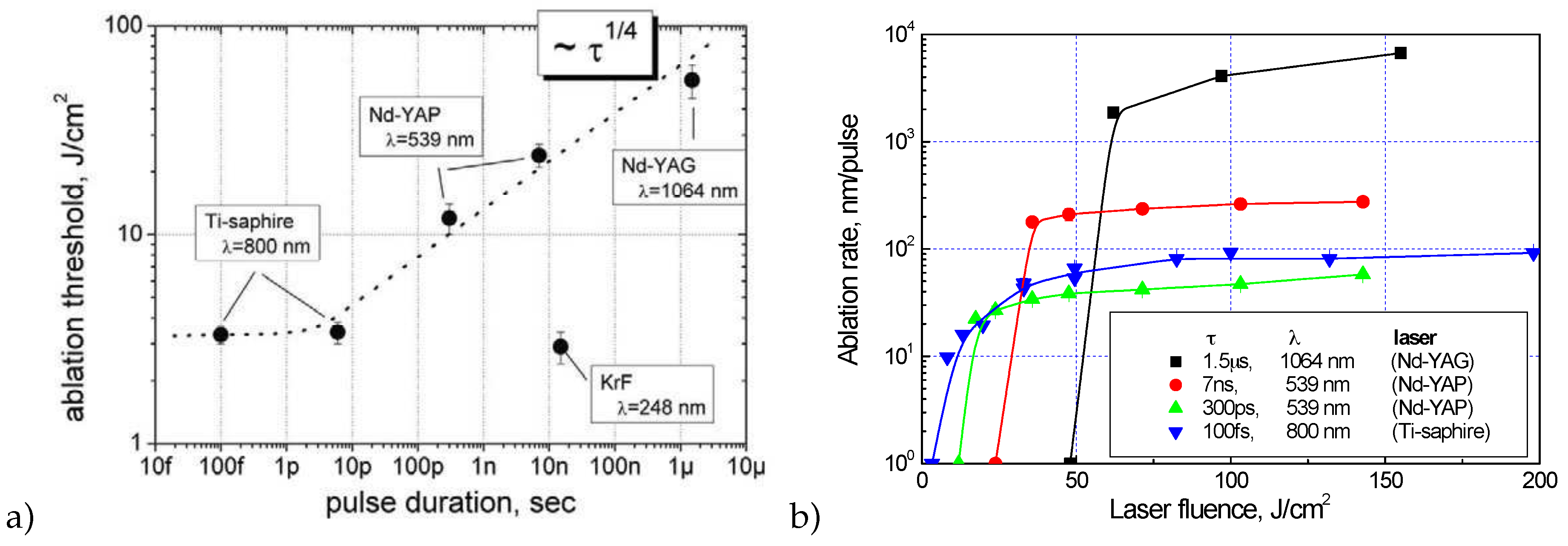

The laser ablation of diamond has a pronounced threshold character [

14]. In other words, a noticeable rearrangement of the structure of the material is observed if only the laser fluence exceeds a certain threshold. It is interesting to analyze the value of the graphitization threshold depending on the pulse duration (

Figure 4a). The ablation threshold value is approximately constant for short pulses (up to 10 ps), and then increases with increasing pulse duration proportionally to the fourth root of the pulse duration. (The exception is a sharp decrease in the threshold for a nanosecond excimer KrF laser (248 nm), associated with the high absorption of diamond in the UV spectral range.) The observed dependence is much weaker than the proportionality to the square root of the pulse duration, which is expected as a consequence of the material cooling due to thermal conductivity. A possible explanation is that the probability of an elementary graphitization event obeys the Boltzmann statistics, and, therefore, the amount of the graphitized phase during laser irradiation depends not only on the laser heating temperature, but also on the time interval during which this temperature is sustained.

As already mentioned, typical ablation rates are similar for diamond and metals due to one-photon absorption in both cases.

Figure 4b shows ablation curves for various laser systems [

48]. For all laser pulse durations used, when the ablation threshold is exceeded, the regime of developed evaporation is attained; the laser heating and the further evaporation of the substance occur so rapidly that the thermal conduction process does not have time to spread a significant part of the energy in the depth of the material.

The dependencies given show that for radiation of microsecond duration the material removal has the highest efficiency. Moreover, simple estimates demonstrate that when using long laser pulses, diamond ablation occurs with virtually no loss of optical energy. For shorter pulses, the ablation rates decrease, which is usually attributed to radiation screening by the ablation plume and material overheating due to a very high laser intensity - the substance does not have time to evaporate or cool. It is interesting to note that, as compared to picosecond lasers, the ultrafast (femtosecond) sources provide the increase in the ablation rate, because one of these two effects - screening by evaporated carbon vapor - disappears.

We emphasize once again that laser ablation, being a thermally stimulated process, is characterized by a threshold value of the laser fluence at which it can develop. At fluencies exceeding this threshold, diamond graphitization and ablation are initiated. In this case a clearly defined crater has to be formed in the zone irradiated, the depth of which is determined by the number of pulses (

Figure 5a). However, the structural inhomogeneity of diamond can lead to uncontrolled and non-local surface or volume destruction (

Figure 5b,c, respectively), which is also accompanied by graphitization.

This effect is attributed to the presence of microscopic absorbing inclusions in the diamond bulk and, as a rule, manifests strongly in polycrystalline diamond, which has multiple defects and their clusters at the boundaries between crystallites. Such inclusions are able to provide stronger, as compared to the surface, heating of the underlying parts of the crystal and their graphitization. Subsurface graphitization, in turn, will entail explosive destruction of the diamond in the bulk or on the surface, depending on how far the absorbing center was from the surface. This is due to the fact that the material density of graphite is less than the material density of diamond, and during graphitization the substance tends to expand. Similar features should be taken into account in high-precision laser micromachining of diamonds.

3.3. Single-pulse ablation of diamond

In the

Section 3.2, it was shown that the multipulse ablation rate and the thickness of the graphitized layer produced by femtosecond pulses are limited by the depth of radiation absorption in the target. In fact, the portion of graphitised/ablated material per pulse is determined by the density of the plasma with which the radiation interacts. When the graphitized surface is irradiated, this plasma consists of

cm

electrons. Therefore, the well-absorbing graphite limits the radiation penetration depth to

nm. On the other hand, during the first pulse, when initially non-conductive diamond is irradiated, the plasma arisen is not so dense: the concentration of

cm

corresponds the graphitization threshold (see

Section 3.1). This plasma interacts dynamically with the pulse itself and also limits the penetration of radiation into the diamond. However, the penetration depth in this case becomes noticeably higher and reaches tens and hundreds of nanometers.

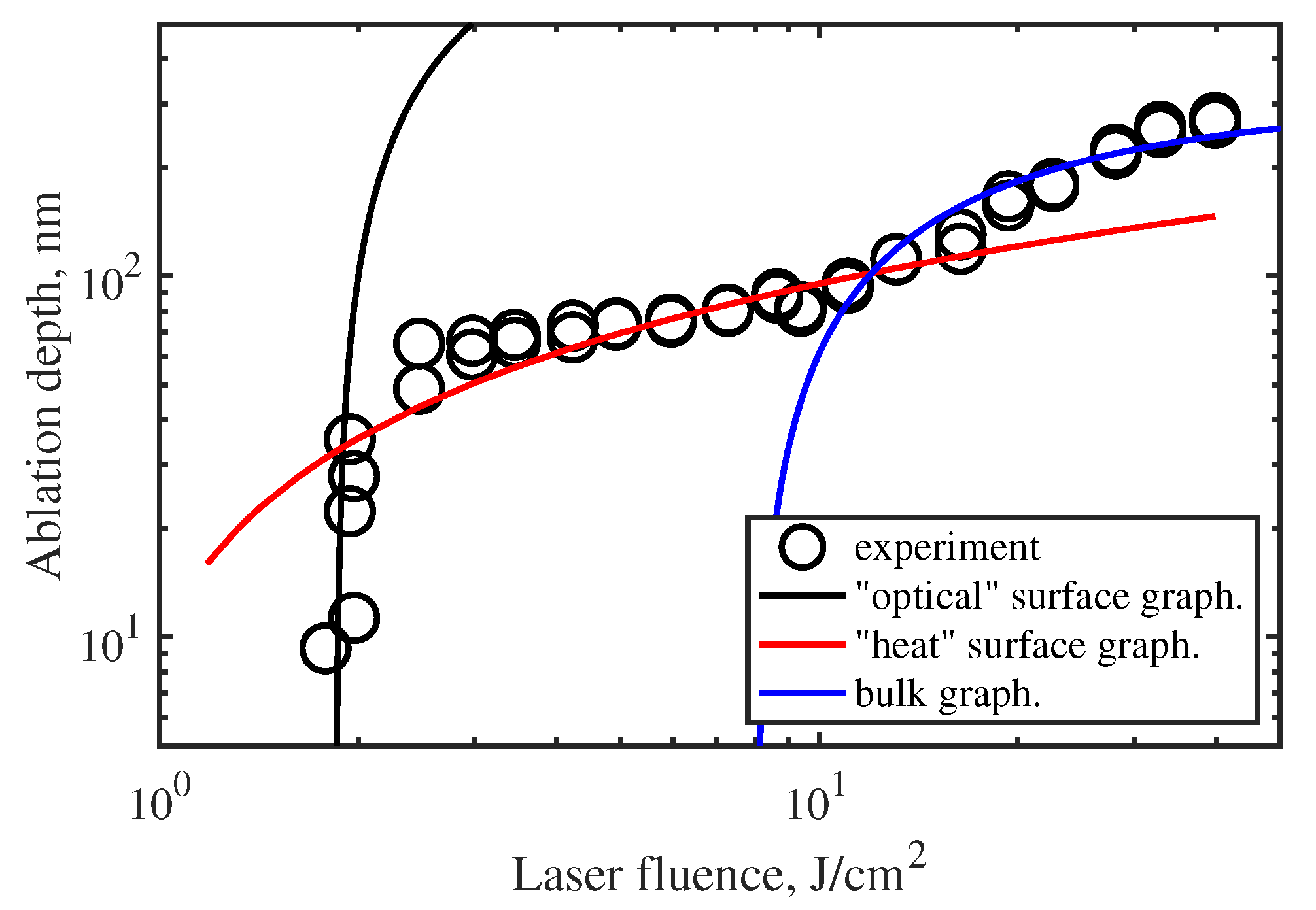

Figure 6 shows the experimental depths of the ablation craters as a function of the laser fluence under the single pulse exposure [

50,

51]. In these conditions the main mechanism of laser energy deposition was two-photon absorption (

fs,

nm). As is evident in the data of

Figure 6, the dependence is complex and consists of three parts revealing three different regimes of graphitization under single-pulse laser irradiation. The first regime is realized at energies close to the threshold. For two-photon absorption the penetration depth is given as:

(

is two-photon absorption coefficient of diamond,

is threshold of graphitization). The field penetrated into the crystal by

m, and

dependence describes well the initial sharp increase in the thickness of the graphitized layer from 10 nm to 70 nm (black curve,

Figure 6).

At energies just above the threshold, a transition to the second graphitization regime, which is characterized by strong saturation, is observed. The depth of graphitization grows slowly, according to a logarithmic law (red curve,

Figure 6). The key factor which restricts the ablation rate in this regime is a finality of graphization wave velocity. Calculations show that the diamond lattice rearrangement occurs layer by layer at a typical velocity of 1 atomic layer (

nm) per 0.1 ps [

52]. The graphitization wave starts from the surface and, as the diamond has a record thermal conductivity (

cm

/s), the subsurface layers have time to cool down before the graphitization wave reaches them. On the other hand, the heat released in the near-surface graphitized region turns out to be "locked," since the thermal conductivity of graphite is much less than that of diamond (

cm

/s). As a result, the increase in the absorbed energy in the second regime causes incremental superheating of graphitized layer instead of growth of its thickness.

The third regime is realized when the laser fluence exceeded a certain threshold and bulk graphitization started in the crystal. Opposed the previous case, such graphitization is not sourced by the surface but occurred simultaneously in the entire excited volume (

m). Indeed, the surface swelling in the laser spot reaches

m, indicating implicitly the thickness of the graphitized phase is close to

m. In this regime, the dependence of the graphitization depth on the laser fluence is also well described within the model of optical field penetration into diamond and two-photon absorption (blue curve,

Figure 6). The simulation shows that a threshold of the bulk graphitization is around 8 times a threshold of the surface graphitization.

3.4. Graphitization of (111) diamond face

Single-shot laser exposure made it possible to investigate a relationship between the crystallographic orientation of a diamond sample and the structure of the graphitized phase. This task is of interest in terms of carbon composites consisting of insulating diamond phase and conducting graphite phase. Laser processing can easily produce graphitic inclusions in diamond, however the crystal perfection of the graphitized phase is rather low. Raman spectroscopy identified laser-modified diamond as a disordered form of carbon [

47,

53], which is much closer to glassy carbon than to highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) [

54]. Essentially, laser-graphitized diamond is the mixture of the

-bonded amorphous carbon intermixed with nanocrystalline graphite with a grain size of approximately 3 nm [

54,

55]. The high amorphization in the laser-graphitized phase deteriorates its conduction. The typical resistivity of the laser-graphitized surface layer exceeds

cm [

56,

57]. In the case of HOPG the conductivity along basal (0001) plane is substantially higher (

cm).

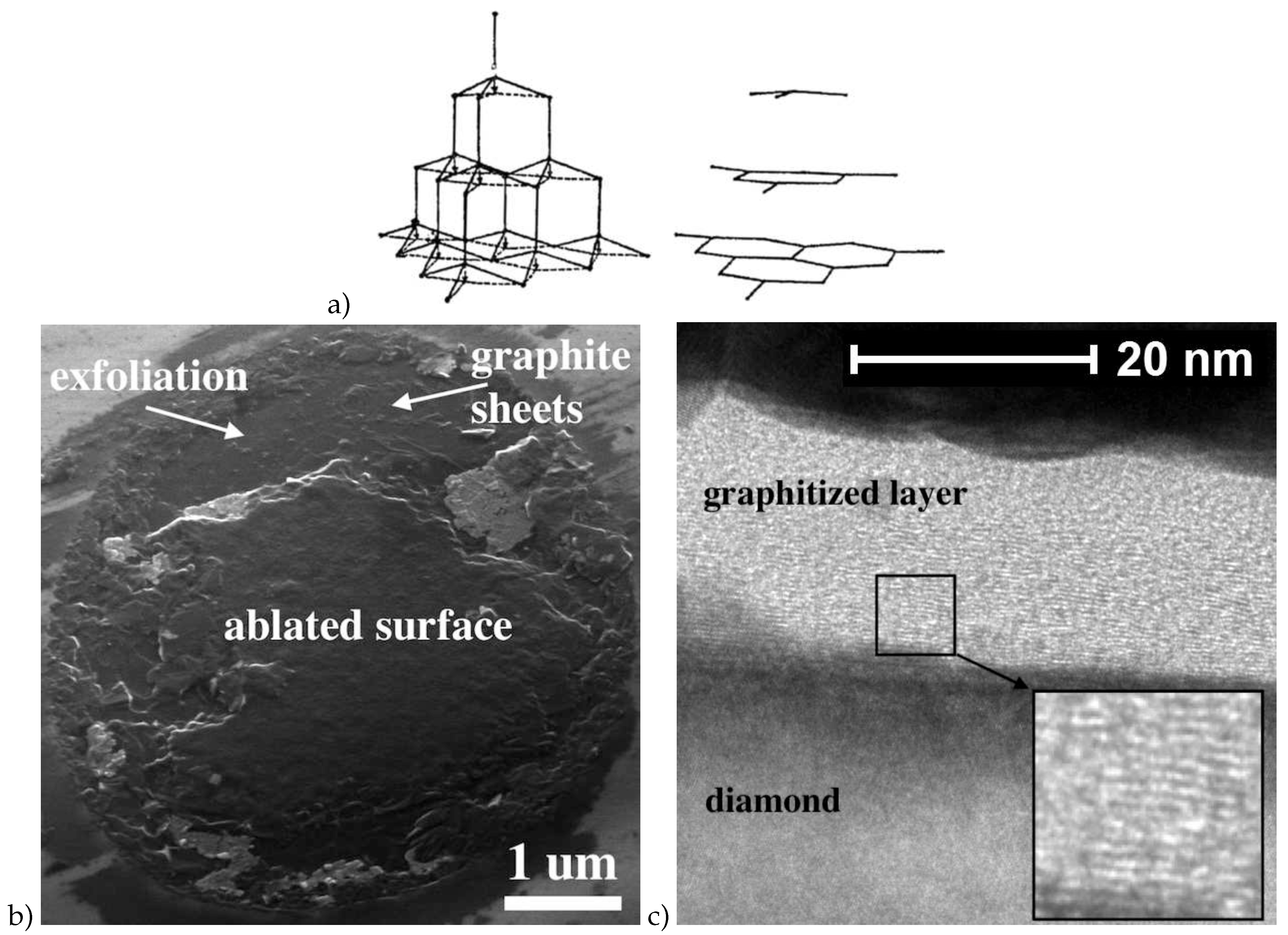

The remarkable improvement of the crystal perfection of the graphitized phase produced on the diamond surface was achieved due to the processing of the (111) face. This face graphitization is preferable, as the energetically favorable diamond-graphite transition is realized via transformation of two diamond (111) planes into a graphite (0001) plane as

Figure 7a illustrates [

58]. As a result, graphite produced on any diamond face always tends to arrange itself so that its basal plane (0001) was parallel to the (111) plane of the diamond crystal [

59]. Thus, the crystallographic orientation of the irradiated surface strongly affects the performance of crystal structure of graphitized phase. Graphitized layer produced on the (111) surface has minimal internal stresses thus improving its structure. It should be noted that the formation of highly oriented graphite on the (111) surface was predicted by molecular dynamics simulations performed for both stationary furnace heating [

52] and pulsed laser heating [

60].

The structure of the layer graphitized with single femtosecond UV pulse on the (111) diamond face was studied in detail in [

61]. The SEM inspection of graphitized diamond surface confirm that the graphitic sheets arranged along (111) plane (

Figure 7b). The thin flakes graphite are found to be of about 100 nm laterally. The adhesion of these flakes to the substrate was rather low; the modified phase could be easily scratched by a steel tip. According the data of bright-field TEM microscopy the structure of the carbon in the bulk of the graphitized layer (

Figure 7c) is highly ordered. The laser-modified material resembles HOPG and consist of regular sheets which are parallel to the diamond surface. The closer to graphite-diamond interface, the higher the structural performance of graphitized material is and the more it resembles HOPG. On the other hand, the sub-surface (

nm) graphitized structure is rather amorphized.

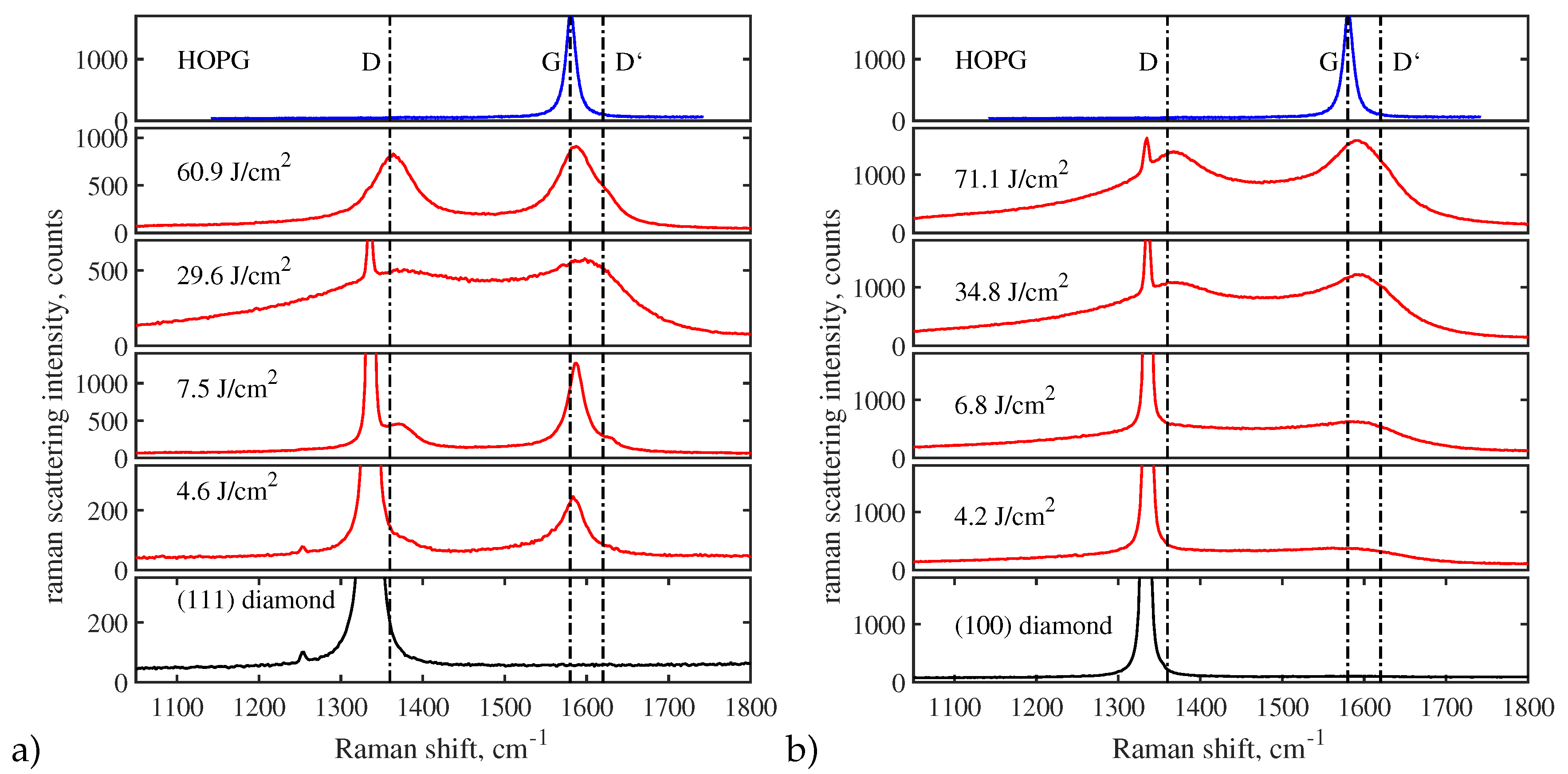

Besides the fact that the structure of the graphitized layer is determined by the crystallographic orientation of the irradiated face, it essentially depends on the laser fluence.

Figure 8 compares the Raman spectra obtained on the (111) and (100) faces. The spectrum of original diamond, that exhibits a single intensive "diamond" peak at 1333 cm

, is depicted in the bottom part of both panels. In the case of (111) graphitization the lowest fluencies are characterized by the emergence of the narrow

G peak (

cm

), while the

D and

peaks are relatively low and can hardly be distinguished. Taken as a whole these spectra are close to the HOPG spectrum [

62]. (The typical Raman spectrum of HOPG is presented in the top part of the

Figure 8). Note that above SEM and TEM images correspond exactly this regime. At the elevated pulse energy the Raman spectra acquired the typical features of the graphitization on the (100) diamond face: the

D and

G peaks become wider, attributing the formation of disordered nanocrystalline graphite [

62]. It noteworthy that the disorder diminishes in the bulk graphitization regime (see

Section 3.3). The

D and

G peaks get relatively narrow (

Figure 8a,

J/cm

) and the correspondent spectra resemble the spectra of a diamond graphitized at the low fluence.

Nothing similar happens when the (100) or (110) diamonds are graphitized. In the case, as a number of studies proved the graphitized material is close in structure to nanocrystalline graphite with a significant content of the amorphous phase [

47,

54,

55,

63,

64,

65]. The typical Raman spectra for the (100) face irradiated at different laser fluencies are shown in

Figure 8b.

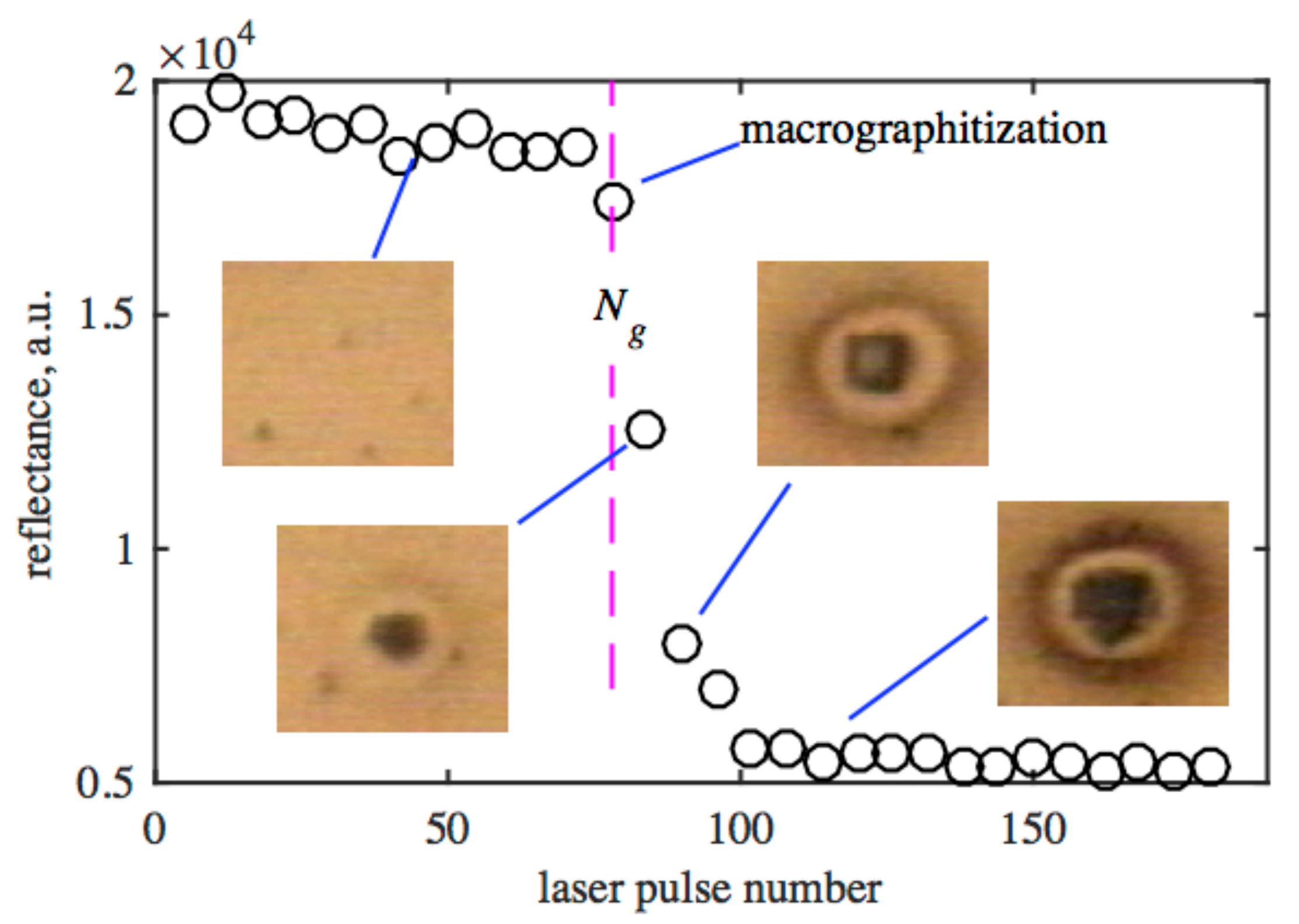

3.5. Accumulative graphitization of diamond

Before the discussion of subthreshold regimes of exposure to diamond, a few words should be said about the accumulative regime of irradiation [

33,

39]. In this regime the laser fluence is less than the single-pulse graphitization threshold but higher than the multipulse one. During multipulse irradiation the surface in the laser focus remains uncovered with an absorbing graphitized layer, and the diamond is directly exposed to radiation. The effect of each individual pulse is too small to be measured and it introduces a tiny change (damage) in the lattice. However, being permanent, these changes accumulate from pulse to pulse. And after a certain time they appear in the form of the rapid graphitization of the diamond surface, which can be easily detected (

Figure 9).

To date, understanding the mechanisms of accumulative graphitization is rather poor. In [

39] a model of accumulative graphitization of diamond under the femtosecond irradiation is proposed. It is based on two-stage growth of graphite-like nanodroplets and transformation of diamond into graphite around initial point nuclei (accumulation stage). When the droplet reaches a certain critical size

, its heating by a femtosecond pulse becomes effective and the critical temperature required for thermal graphitization of diamond is reached. In this moment the growth of the droplet accelerates and the droplet increases to a micron size in several pulses.

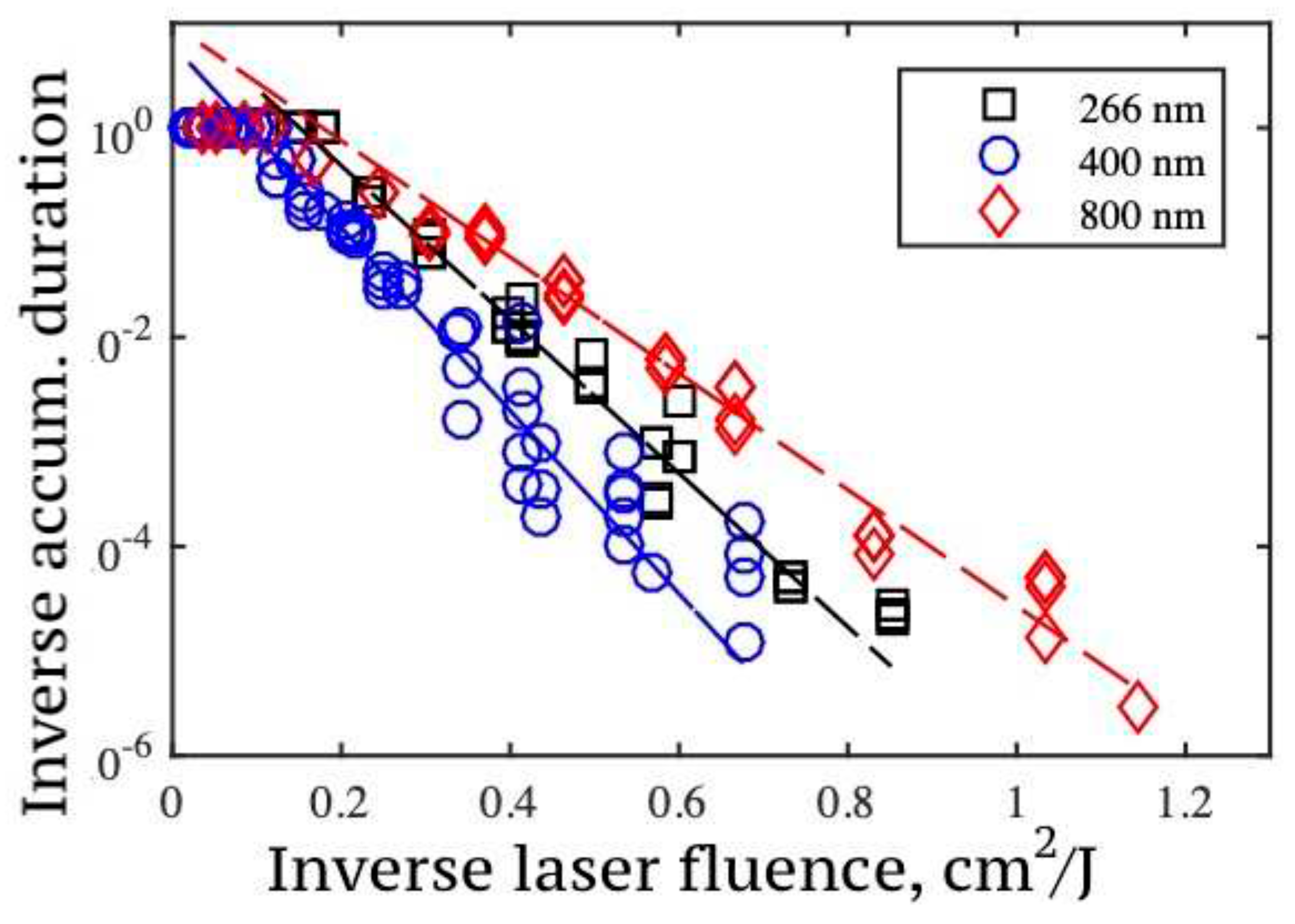

It is substantiated experimentally that the duration of the accumulation stage (

pulses) can serve as a measure of the rate of structural changes in the lattice at a fixed laser fluence. This makes it possible to estimate the graphitization rate at the accumulation stage as

. Experimental dependences of

on laser fluence for Ti-sapp laser radiation (800 nm, 400 nm and 266 nm) are shown in

Figure 10. Their analysis shows that the growth rate of graphite clusters on the diamond surface obeys the Arrhenius law. In other words, accumulative graphitization is a thermally stimulated process. On the basis of the experimental data, the assessments of the rate of accumulative graphitization under femtosecond irradiation were obtained: graphite nanodroplets on the diamond surface grow at a rate of

nm/pulse. The corresponding dependence on laser fluence will be discussed in

Section 3.7.

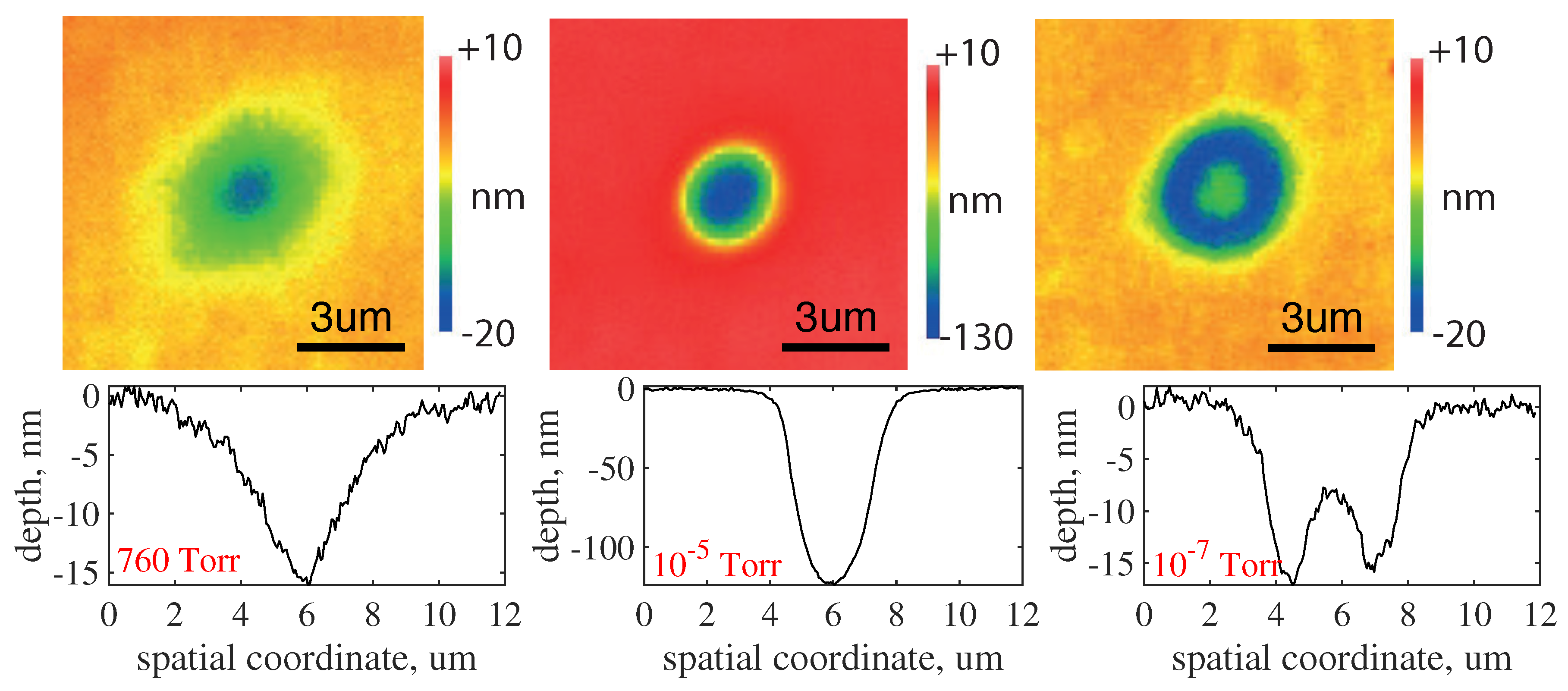

3.6. Nanoablation of diamond

This Section discusses the main regularities of the process of laser nanoablation of diamond - slow etching of a sample surface in the air atmosphere at laser fluence below the multipulse graphitization threshold. The first observations of such a graphitization-free etching process took place in the works studying laser annealing of ion-implanted crystals [

28,

29,

30]. These observations initiated a series of experiments when already pure diamonds, which were free of introduced defects and characterized by high optical transparency, were subjected to long-term irradiation with nanosecond KrF laser pulses. It was found that visible graphitization of the surface did not develop at laser fluence of 15 J/cm

during millions of pulses [

31]. Simultaneously, the removal of carbon inside the laser spot happened, the rate of which was about

nm/pulse. To emphasize the extremely low etching rates, this process was called "nanoablation".

The experiments, comparing the rates of nanoablative diamond etching in air and in a helium flow [

31], showed the importance of atmospheric oxygen deficiency. More detailed studies had been demonstrated that the etching rate dependence on the ambient pressure is essentially nonmonotonic (

Figure 11). The nanoablation rate (

r) increases almost linearly with pressure in the high vacuum of

to

Torr. However, a further increase in pressure leads to a sharp drop in the carbon removal rate, and in the range from

Torr to atmospheric pressure, this rate remains constant at

nm/pulse.

The increase in the nanoablation rate () observed at low pressures suggests to exclude the evaporative mechanism of substance removal and leads to the conclusion that the nanoablation is a chemical reaction. A main reactant in this reaction is, obviously, oxygen, which (i) is chemically active and (ii) reacting with carbon creates volatile components (CO, CO).

Detailed analysis of the

curve shows that its complex character cannot be explained solely in terms of the reaction with oxygen. A sharp drop in the nanoablation rate at pressures of

Torr indicates the presence of some inhibitor of laser stimulated oxidation of diamond. The most likely candidate for this role is water contained in the atmosphere and easily adsorbed on the hydrophilic surface of diamond, up to the formation of a thin aquatic layer there [

66]. Indeed, water vapor significantly slows down the oxidation process. For example, 2.5% water vapor increases in the activation energy of thermal oxidation of diamond by 1.5 times [

67].

The ambient pressure also affects the topology of craters formed during nanoablation. This influence has two aspects, shown in the

Figure 12. The first is that the depths of the craters obtained at the same dose of radiation differ by several times (see craters obtained at

Torr and at 680 Torr). The second aspect is that at low pressures (in the region of linear growth of the nanoablation rate) the shape of the profile changes: at a pressure of

Torr the crater bottom noticeably flattens, and at

Torr an elevation appears in the crater center. In other words, at low pressures, the rate of nanoablation in the center of the irradiation zone is significantly lower than on its periphery, despite the fact that the radiation intensity in the center is higher.

The effect arises due to a mechanism that becomes important in the shortage of the atmospheric oxygen. This mechanism is surface oxygen diffusion, which allows additional amount of oxygen to appear inside the laser affected zone. Indeed, laser heating leads to desorption of oxygen, thus forming a gradient in the surface concentration of oxygen: its amount in the center of the laser spot turns out to be significantly lower than at the periphery. The surface diffusion of adsorbed oxygen develops in the direction opposite to the concentration gradient, i.e., to the center of the laser spot. As a result, much more oxygen piles up on the periphery of the crater due to the diffusion than was adsorbed in the center of the spot from the gas phase. This eventually causes the flattening of the crater bottom and even its uplift (

Figure 12,

Torr).

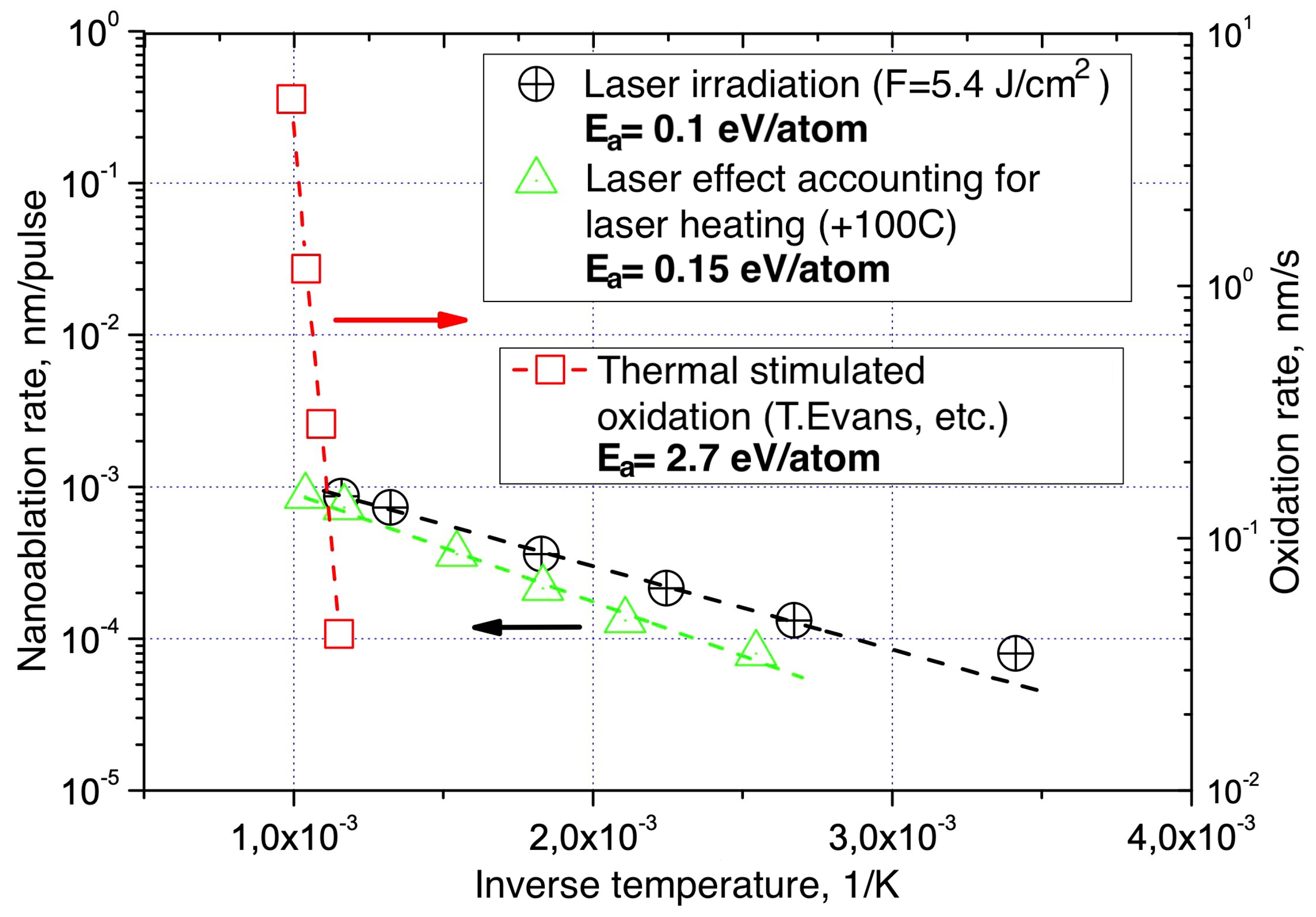

The understanding nanoablation as a chemical reaction is crucially supported by the investigations of its kinetics under external heating. The nanoablation rates were measured for various temperatures in the range 20C ÷ 600C at a fixed laser fluence (

Figure 13). It has been found that the nanoablation rate increases approximately 10 times as the temperature rises from room temperature to 600C and reaches

nm/pulse. In this case, the temperature dependence is close to Arrhenius law with an activation energy of about

eV/atom.

For comparison purposes, the

Figure 13 presents data on thermally stimulated oxidation of diamond [

68]. The corresponding activation energy is

eV/atom and exceeds the activation energy under combined action (laser exposure + external heating) by a factor of 25. These data show that the laser action drastically reduces the height of the potential barrier, which must be overcome in each oxidation event. For this reason, under laser excitation the reaction rate sharply increases, and so much so that the carbon removal becomes noticeable even at room temperature.

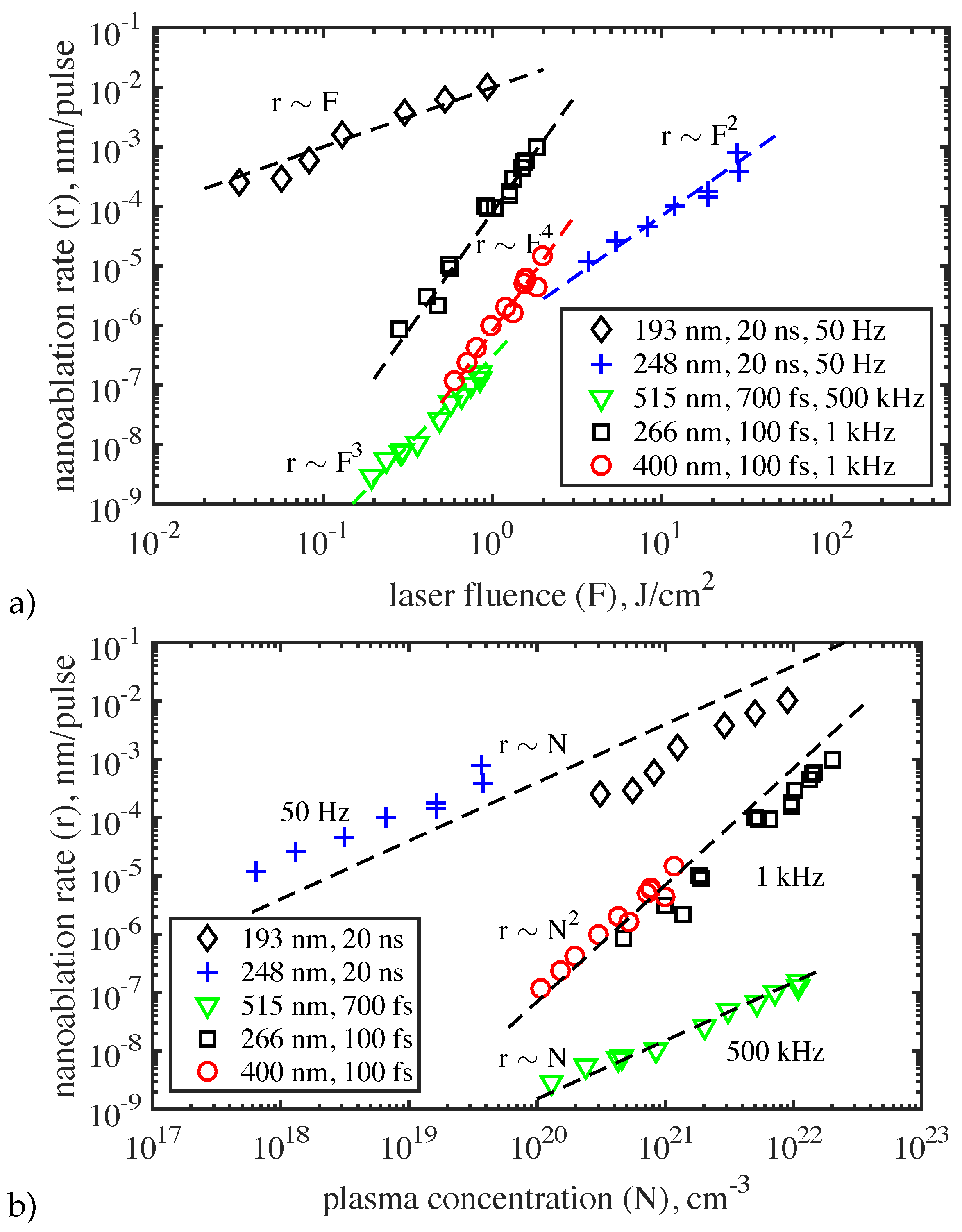

Thus, nanoablation is a photostimulated process and the parameters of laser radiation largely determine its efficiency. This is confirmed by the nanoablation rate dependencies on the laser fluence, radiation wavelength, and laser pulse duration [

69,

70,

71]. Unlike conventional thermally stimulated ablation, nanoablation is a non-threshold process, and for all used laser sources, the material removal rate

r was found to depend on the laser fluence

F in a power-law manner:

, where the exponent

s depends on the radiation wavelength and pulse duration (

Figure 14a).

As in any photo-stimulated process, the wavelength dependence is expectedly critical. In particular, etching of the diamond surface does not take place under IR irradiation. When using radiation in the visible or UV spectral ranges (193 nm - 515 nm), two regimes of nanoablation were observed, depending on the duration

of laser pulses. At

1 ps, the nanoablation rate is proportional to the concentration of carriers excited by radiation, while for femtosecond pulses (

fs) this dependence turns out to be nonlinear, namely, quadratic (

Figure 14 b). (

Figure 14b is a recalculation of nanoablation data (

Figure 14a) using diamond photoionization data (

Figure 2)). It was also found that as the pulse repetition rate increases (at least, up to

kHz), the nanoablation rate remains stable, that opens up new possibilities in the development of high-performance nanomachining methods for the diamond surface.

Therefore, the nanoablation proceeds through a three stages. The first step is dissociation of molecular oxygen on the surface, which is known to be effective at room temperature [

72]. Oxigen chemisorption takes place between laser pulses and causes oxygen species to saturate dangling bonds and form ether-like bridge [

73] or ketone on-top sites [

74]. The second step is realized when light is absorbed and the energy imparted makes the excited electrons leave the bonding orbitals and transfer to nonbonding or antibonding states. This runs the third step that is a C–O group desorption, which hypothetically consists of six elementary transformations, including

-scission of the C–CO bond, formation of a dimer C–C bond, and cleavage of the second C–CO bond [

75]. Two of these transformations have high activation barriers (

eV) and control the overall reaction kinetics. Without laser pumping these barriers stop the oxidation at room temperature, whereas photo activation enables the C–O group desorption. So, in the last third step the oxides desorb from the surface, resulting in gradual removal of the substance from an irradiated zone.

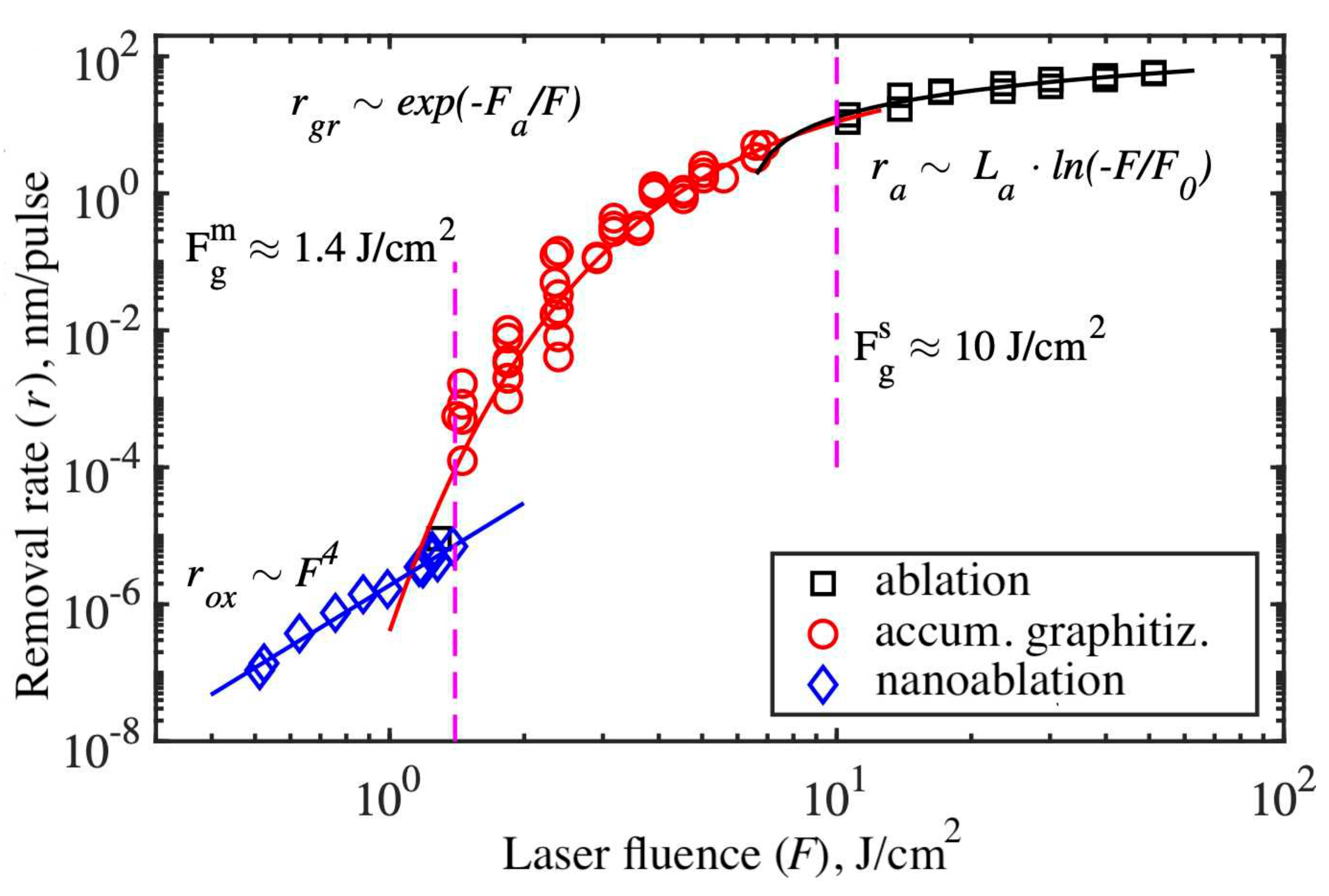

3.7. Overall picture of laser-induced processes in diamond

It is interesting to comprehend the relationship of various laser-stimulated processes and compare their rates. The instance of such data combining the rates of (i) nanoablation, (ii) accumulative graphitization and (iii) evaporative ablation for the case of 2

nd harmonic of Ti-sapp laser are shown in the

Figure 15. Data for nanoablation and evaporative ablation were measured directly (as crater depth divided by the number of pulses). The data for the accumulation regime were calculated as

, where

nm is a constant calculated from the conditions of heating a graphite drop with a femtosecond pulse [

39]. These data show that, taken as a whole, the laser pulse exposure on diamond is not a threshold process, as previously thought. Intense radiation initiates a complex of fast or slow interrelated processes resulting in diamond transformation or destruction.

It is apparent, the result of multipulse irradiation critically depends on the laser fluence. There are two key points: single pulse graphitization threshold J/cm and multipulse graphitization threshold J/cm. At low laser intensity (), nanoablation takes place. Typical rates for this laser are nm/pulse and below. At moderate fluence () during long-term multipulse exposure the diamond lattice gradually transforms into a graphite-like phase. Typical rates for this laser are nm/pulse.

The observed behavior suggests the hypothesis of a competition between photooxidation and graphitization in diamond. If the optical energy fluence is below the multipulse graphitization threshold (

), photooxidation dominates. Its rate is much higher than the rate of thermally stimulated graphitization. Any graphite cluster produced will be exposed to oxygen and etched away instead of continuing to absorb light and grow. It is the regime that is referred by the term nanoablation. The situation changes on going to a higher laser fluence

: in the case photooxidation can not completely remove graphitized clusters, and they grow faster and faster. Accumulative graphitization develops, as detailed in the

Section 3.5. Thus, the lower limit of the accumulative graphitization rate is determined by the competition between it and nanoablative etching.

In turn, the upper limit of the accumulative graphitization rate is limited by the development of single-pulse ablation, the typical rates of which are

nm/pulse (

Figure 15). This regime is completely determined first (before graphitization) by the process of multiphoton absorption in diamond and then (after graphitization) by single-photon absorption in graphite, and is described in detail in

Section 3.2 - 3.3.

3.8. Laser-induced NV centers in diamond

This Section is devoted to another important aspect of laser interaction with diamond: the possibility of modifying its lattice at the atomic level, in other words, to the formation of structural defects. The nitrogen-vacancy complexes (NV centers) are of main interest due to the perspectives of their application in quantum optics, probing, and other fields [

18]. Since nitrogen is an impurity that is difficult to get rid and which is always present in diamonds (including synthetic ones), the main difficulty lies in the controlled and preferably local generation of diamond lattice vacancies. Significant efforts are being made to use ionic [

76], electronic [

77], and laser exposure [

35,

78,

79] for this purpose.

It turned out that different regimes of laser generation of NV centers are possible: with graphitization of the diamond lattice and without it. It is rather simple to obtain generation of NV centers in the graphitization regime, since such a strong lattice damage is a natural source of vacancies that relatively easily diffuse into diamond over distances of

m. In the experiment, a strong enhancement of the luminescence of NV centers was found near the regions of laser graphitization, which were created both on the surface [

78] and in the bulk of diamond [

79]. However, the use of such structures is very limited, since damage to the crystal lattice negatively affects properties of NV centers, in particular, the inhomogeneous broadening of optical transitions in the defect increases dramatically.

Recently, Chen et al. [

35] showed the possibility of the formation of NV centers with a femtosecond laser in the bulk of diamond without total destruction of the lattice. A narrow range of pulse energies was found in which vacancies can be generated using single-pulse laser irradiation avoiding visible graphitization. Above, we have described this regime as the accumulative graphitization (see

Section 3.5). We emphasize that Chen et al., working in the accumulative regime, affected the diamond by a single shot only and, thus, deliberately prevented the development of macrographitization. In order to heal the created laser damage to the lattice, the crystal was annealed at the temperature of

C. Such a procedure led highly likely to the formation of

centers in the irradiated region, which was buried at the depth of several microns from the surface.

The next reasonable step in order to mitigate the lattice damage was made in [

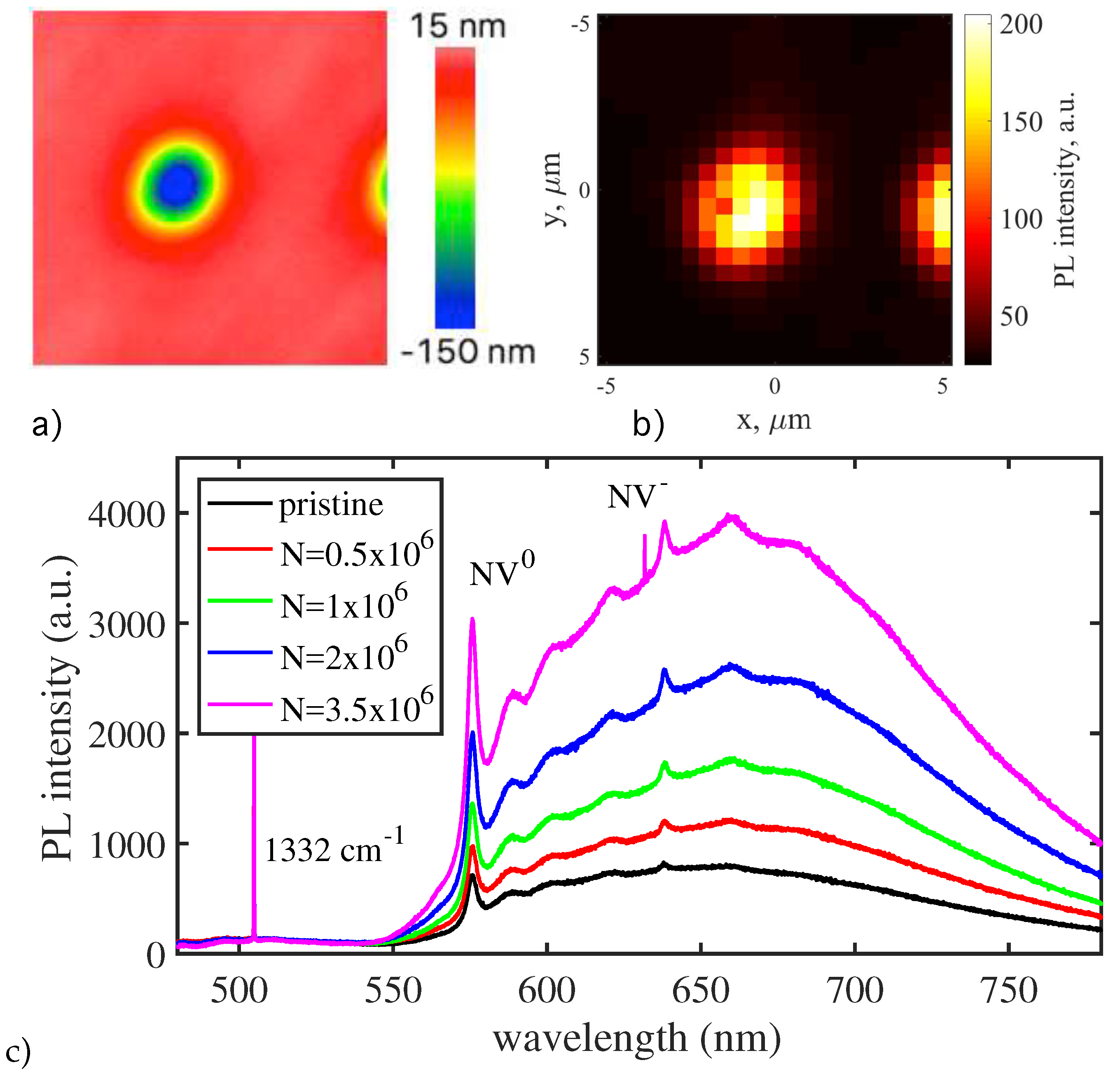

32,

80]. The technique consisted in creating vacancies on the diamond surface, which appear during nanoablation.

Figure 16a,b illustrates two effects that occur inside the irradiated zone after nanoablative etching: (i) the appearance of a nanoablated crater and (ii) a sharp increase in photoluminescence (PL) intensity. The latter indicates the formation of new color centers. The PL signal after irradiation was about ten times greater than before it.

Spectroscopic measurements confirmed that the induced color centers are indeed NV complexes. Both before and after laser exposure, the PL spectra are typical for NV centers and consist of narrow zero-phonon lines (ZPL) and broad phonon wings (

Figure 16c). Both neutral (ZPL at 575 nm) and negatively charged (ZPL at 638 nm) centers are observed. Note that laser irradiation increases the PL intensity, while the shape of the spectra remains unchanged. The ratio of NV

to NV

is constant. To check how much the laser action damages the lattice, the width of zero-phonon lines at low temperatures (

K) was measured. In the PL spectra of irradiated diamond, as compared to pristine one, no changes in the width of the lines at 575 nm and 638 nm were found. The ZPL width at half maximum intensity was found around 0.3 nm for both NV

centers and NV

centers.

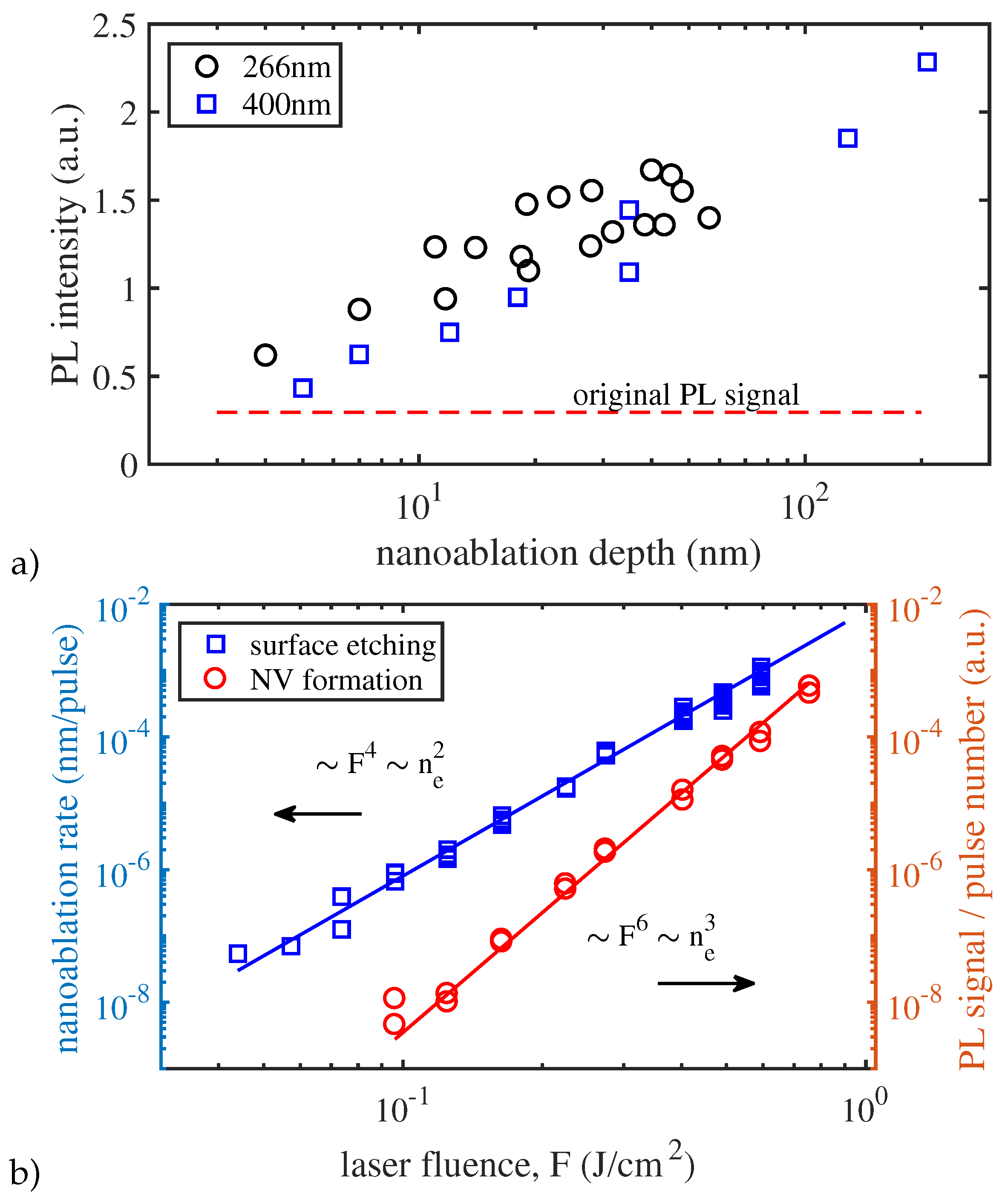

The fact of a stable correlation between the process of creating NV centers and the process of nanoablative etching has been confirmed experimentally.

Figure 17a shows that the intensity of photoluminescence (i.e., the number of NV centers) does not depend on the parameters of the radiation that stimulates nanoablation process, but depends only on the depth of the obtained nanoablative crater. The kinetics of the generation of NV centers was also studied and the dependences of their formation rate on the laser energy density were obtained (

Figure 17b). It turned out that while the nanoablation rate is proportional to the fourth power of the laser fluence (as a result of two-photon absorption - see

Section 3.6), the generation rate of NV centers is proportional to the sixth power of the laser fluence. Allowing for the absorption mechanism, these rates are proportional respectively to the second and third powers of the concentration of the electron-hole plasma. The power-law nature of the dependences suggests laser-stimulated generation of defects in diamond, like nanoablation, to be a photostimulated process.

A possible interpretation of the obtained results is that the process of formation of NV centers goes through three successive stages. First, intense light strongly perturbs the electronic subsystem of diamond, but the accompanying heating is still insufficient to run a thermal graphitization transition. Ionization stimulates the second stage - surface reactions with adsorbed oxygen, and as a result of nanoablative etching, empty atomic nodes are formed on the surface in the carbon lattice - nodes that are not filled with carbon atoms. Actually, being on the surface, these empty nodes are not yet full-fledged vacancies, however, some of them diffuse deep into the crystal, thereby transforming into real vacancies. Third, the vacancies created in this way diffuse further inside the crystal until impurity nitrogen atoms capture them and form NV complexes. In this scheme, the trapping of vacancies is a secondary process, and the rate of formation of NV centers is determined by the mechanism of laser-induced formation of vacancies and their laser-stimulated diffusion.

The results obtained show that femtosecond laser nanoablation is a promising tool for controlling the formation of NV centers in diamonds. This is a relatively slow process, and at a sufficiently low laser fluence, the formation of single NV center requires several laser pulses, which makes it possible to control a number of NV centers and, particularly, to create single-photon emitters in the pregiven points on the surface in a controlled manner.