1. Introduction

Surgical video recordings have become an indispensable tool in surgery and its use can be categorized into 3 main groups [

1]:

Surgical Education and Training: Video recordings provide a valuable resource for trainees to observe and learn surgical procedures from experts. By capturing critical moments during surgery, videos also allow for retrospective analysis and discussions among surgical teams and aid in complex decision-making. Literature reports have documented the utility of surgical video review in assessing anatomical landmarks, identifying surgical errors, refining surgical techniques [

2], and the development [

3] and assessment [

4] of objective surgical skill metrics which can be used for training. Additionally, video-based platforms and telemedicine applications have enabled remote surgical education and mentorship, further expanding access to surgical training opportunities.

Patient Outcomes Assessment: Surgical video recordings provide objective documentation of surgical procedures, enabling detailed analysis of surgical techniques, complications, and their impact on patient outcomes. Retrospective video analysis has been utilized in several studies to investigate patient outcomes [

5].

Quality Improvement Initiatives: By reviewing surgical videos, surgical teams can identify areas for improvement, refine surgical approaches, evaluate adherence to established protocols, and enhance patient safety[

6]. Furthermore, video-based quality assurance programs have been implemented to monitor surgical performance, benchmark outcomes, and ensure standardized practices across institutions [

7].

Uniform surgical phase definition and assessment is an enabling factor in many of the applications above. Surgical phase assessment allows for consistent and standardized indexing across procedures which facilitates video review, analysis and sharing. As video analysis, computer vision, artificial intelligence, and data-analytics (so called “surgical data science”) enter surgical theaters, the importance of correct and uniformly defined surgical phases increases. This is especially true for complex surgeries which require a decomposition into simpler phase blocks for objective assessment and review [

8]. Previous work has also shown that phase definitions, even for non-complex procedures, are often not uniformly defined [

9] and there is a clear need for common ontologies to unlock the full potential of surgical data science [

10]. Up to now, researchers have been focusing on shorter and often linear procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy[

11], whilst more varying and complex procedures, which might benefit most from new data science insights, remain poorly investigated.

One such longer procedure with more inherent variation is robot assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN). Partial nephrectomy itself is the gold standard treatment for patients with T1 renal cell carcinoma [

12]. RAPN has become increasingly popular, amongst others because of its low morbidity and early convalescence when compared to open surgery [

13] and its shorter learning curve when compared to laparoscopy [

14].

Apart from the usefulness of surgical phase indexing for video manipulation and case revision, surgical errors are often related with, and dependent on, specific surgical phases [

15]. As such, surgical phases form an initial and crucial step towards achieving automated and objective surgical skill assessment. A skill assessment system should first identify the phase it is in, before focusing on the errors inherent to that phase. Error reduction and skill enhancement through proficiency based progression as compared to classical training has proven to be beneficial for surgical skill acquisition and quantification [

16]. Surgical phase duration has not yet been shown to correlate with surgical skill. When assessing clinical outcomes, full surgical duration has been investigated for correlations [

17,

18,

19]. To our best knowledge, specific surgical phase duration and possible correlations with patient-specific clinical parameters has not been performed.

In this work, we firstly propose a vision-based framework for objective, uniform, and precise surgical phase definition during RAPN. The definition is based on previously developed and clinically validated metrics for a proficiency-based curriculum[

4].

Secondly, we manually analyze 100 RAPN procedures to refine and optimize the previously defined visual cues. We compare our annotations to a commercially available online platform (Touch Surgery™ – Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) which provides phase information when uploading videos to its online library without user input. We evaluate its correctness by comparing manually performed in-house annotations.

Finally, we perform the first statistical exploration of phase durations and patient characteristics/clinical outcomes in RAPN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data collection and visual cue definition

During January 2018 - June 2022, 100 transperitoneal RAPN procedures were collected in OLV Aalst Hospital (80 procedures) and Ghent University Hospital (20 procedures) after IRB approval. All procedures were performed on Intuitive Xi robotic systems (Intuitive™, California, USA).

We derive 16 visually distinctive phases from the validated RAPN metrics framework as developed by Farinha et al [

3,

4]. We define exact visual cues as starting points for surgical phases.

Table A1 (Appendix) depicts the exhaustive phase list and corresponding visual cues. We adapt the existing framework, defined for left-sided RAPN, for common phases as present in both left and right-sided RAPN. We refer to this annotation framework as the Orsi-framework.

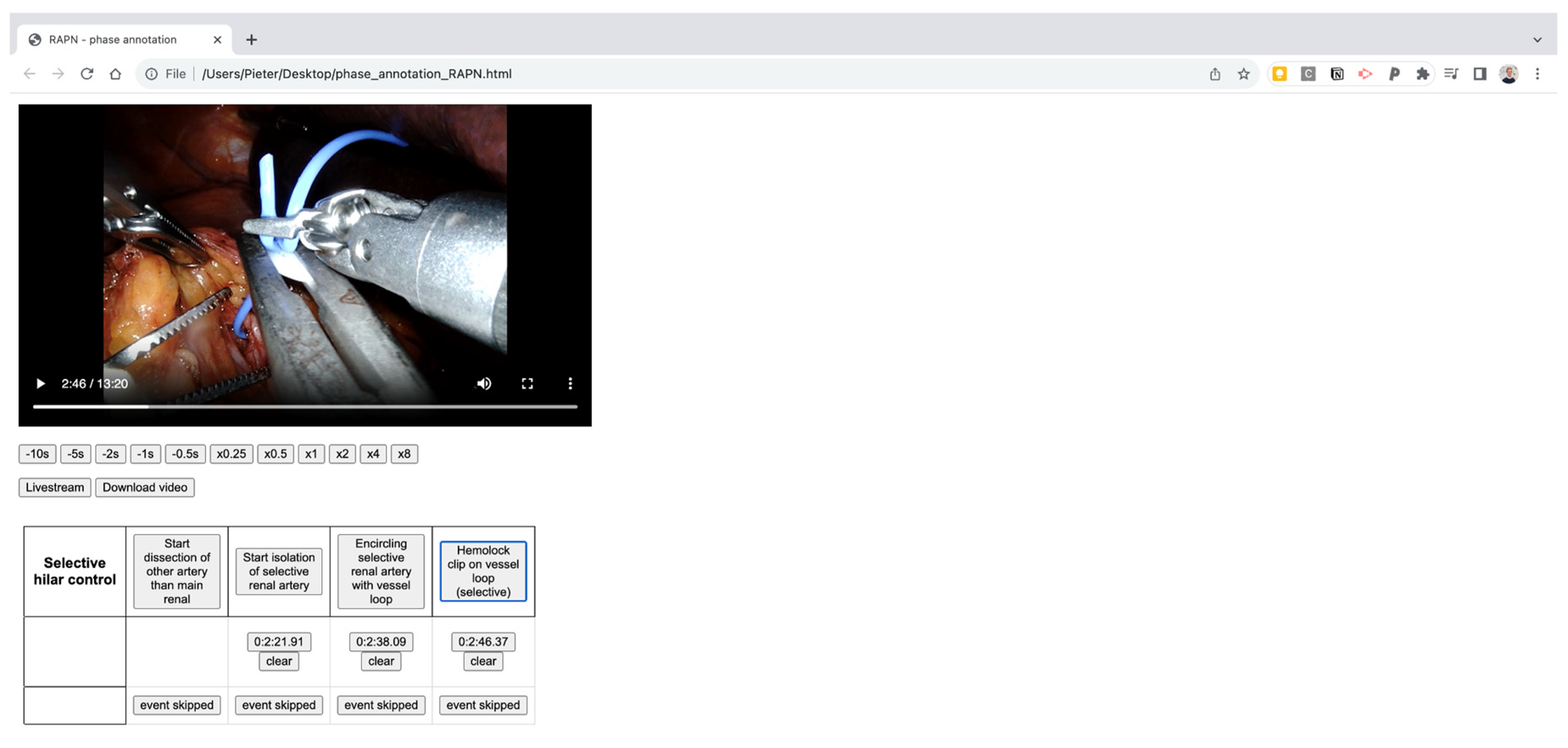

An in-house developed manual annotation tool is used, consisting of an in-browser viewer which allows to load a video, precisely define starting points of selected phases and export the timepoints with millisecond precision afterwards. An example of the manual annotation tool can be found in the Appendix (

Figure A1). All videos were assessed by three medical students (MD, CVS, TO) after consensus on the visual definitions with a consultant urologist (RDG). The final manual student annotations were subsequently double-checked by a second consultant urologist (MPL).

2.2. Comparison to commercial software

The precise and more nuanced Orsi definitions are concatenated in 13 phases to be consistent with the Touch Surgery (TS) phase definitions for a one-to-one comparison. The phases consistency can be found in

Table 1. Two medical students (KVR, AW) reviewed all videos for correctness after automated, rule-based concatenation.

All uploaded videos were automatically anonymized with removal of all possible identity clues, which include removal of out-of-body segments, as well as removal of segments with TilePro™ function (Intuitive™, California, USA) while they display patient-specific information such as CT, MRI or 3D model data [

20]. The anonymization did not alter the case duration as these parts were blacked out, rather than cropped. Subsequently, videos were uploaded to the TS platform (software version February 2023). The Orsi-analysis was performed on full non-anonymized videos, under IRB approval.

After upload and processing, TS timepoints were manually extracted from the online commercial platform.

The Touch Surgery platform does not provide details on the phase definition rules. The videos underwent automated similarity analysis in which the manual Orsi annotations are compared to Touch Surgery annotations by use of a predefined loss function. This function objectifies how differently phases were annotated and detects procedures who have least similarity.

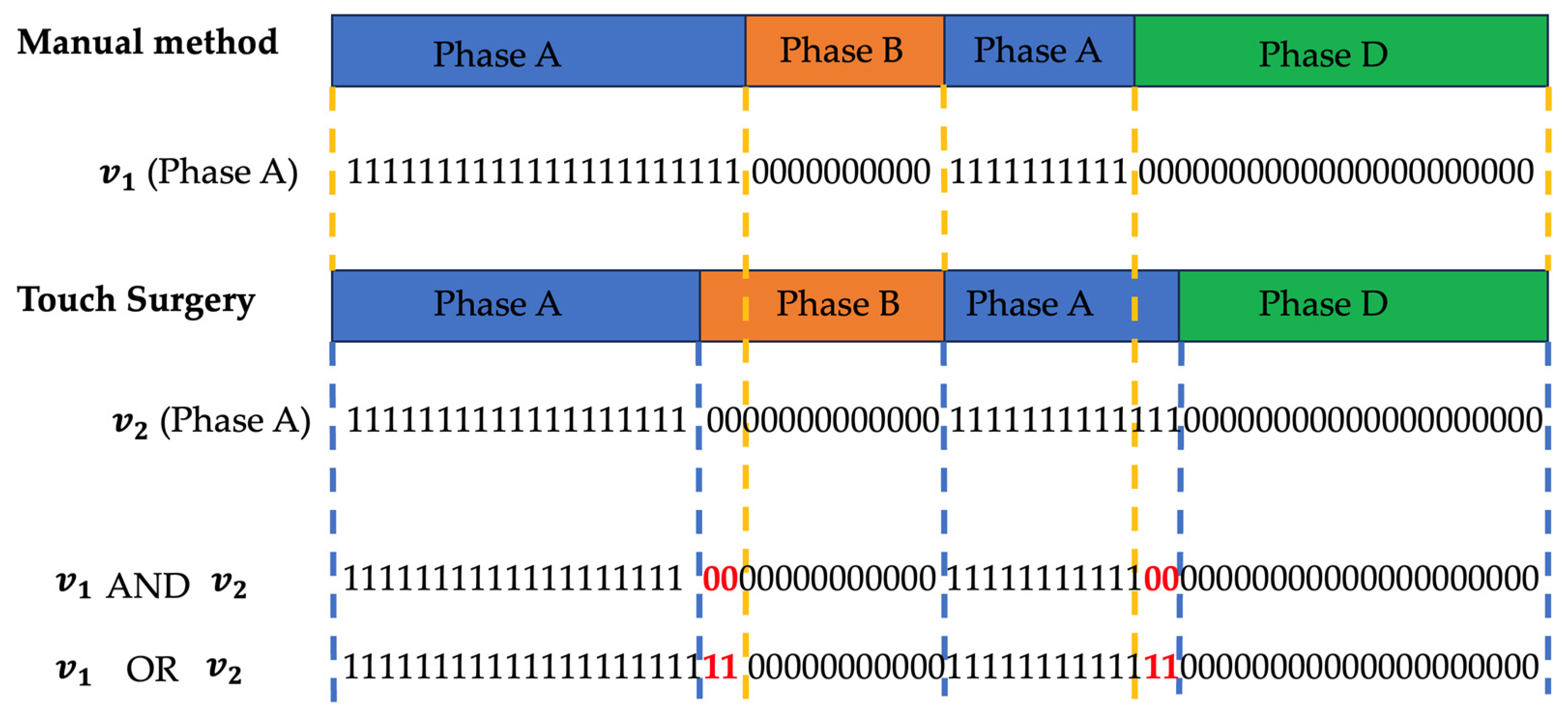

We base the loss function on a commonly used metric called Intersection-over-Union (IoU). For each phase, a binary vector is created which indicates 1 for seconds that belonged to that phase for the given annotation method and 0 elsewhere. The total sum of all phase vectors equals the total procedure time in seconds. The concept is visualized in

Figure 1. The IOU per phase is then calculated as follows:

Where

is the vector with the number of seconds spent in a certain phase X in the manual annotation and

is the vector with the amount seconds spent in phase X according to the Touch Surgery annotation. Both are linked in a one-to-one temporal fashion as depicted in

Figure 1.

As such, the numerator holds the number of seconds where both procedures “agree” on the investigated phase for the full procedural. The overlaps are summed as phases can reoccur. The denominator counts the number of seconds where the phase was indicated by at least one of both annotation methods. A perfect correspondence between both annotation approaches results in an IoU(phase) of 100%. To determine the final loss, we multiply all IoU(phases) and take the negative logarithm.

The loss function is described below:

2.3. Clinical analysis

We explored correlations between phase durations and the following clinical parameters: age, gender, tumor complexity (PADUA score), tumor size, prior abdominal surgery, BMI, pT stage, histology, preoperative and postoperative renal function as measured by eGFR and creatinine. We also examined postoperative complications. Durations are assessed for both TS and manual (M) definitions. Correlation examination was performed by use of the Spearman’s, Kendall’s tau tests, as appropriate. In case of statistically significant correlation, a linear regression model was then built to analyze the relationship between the identified variables. All the analysis were performed by using Jamovi software v2.3.

3. Results

3.1. General Phase data analysis and comparison

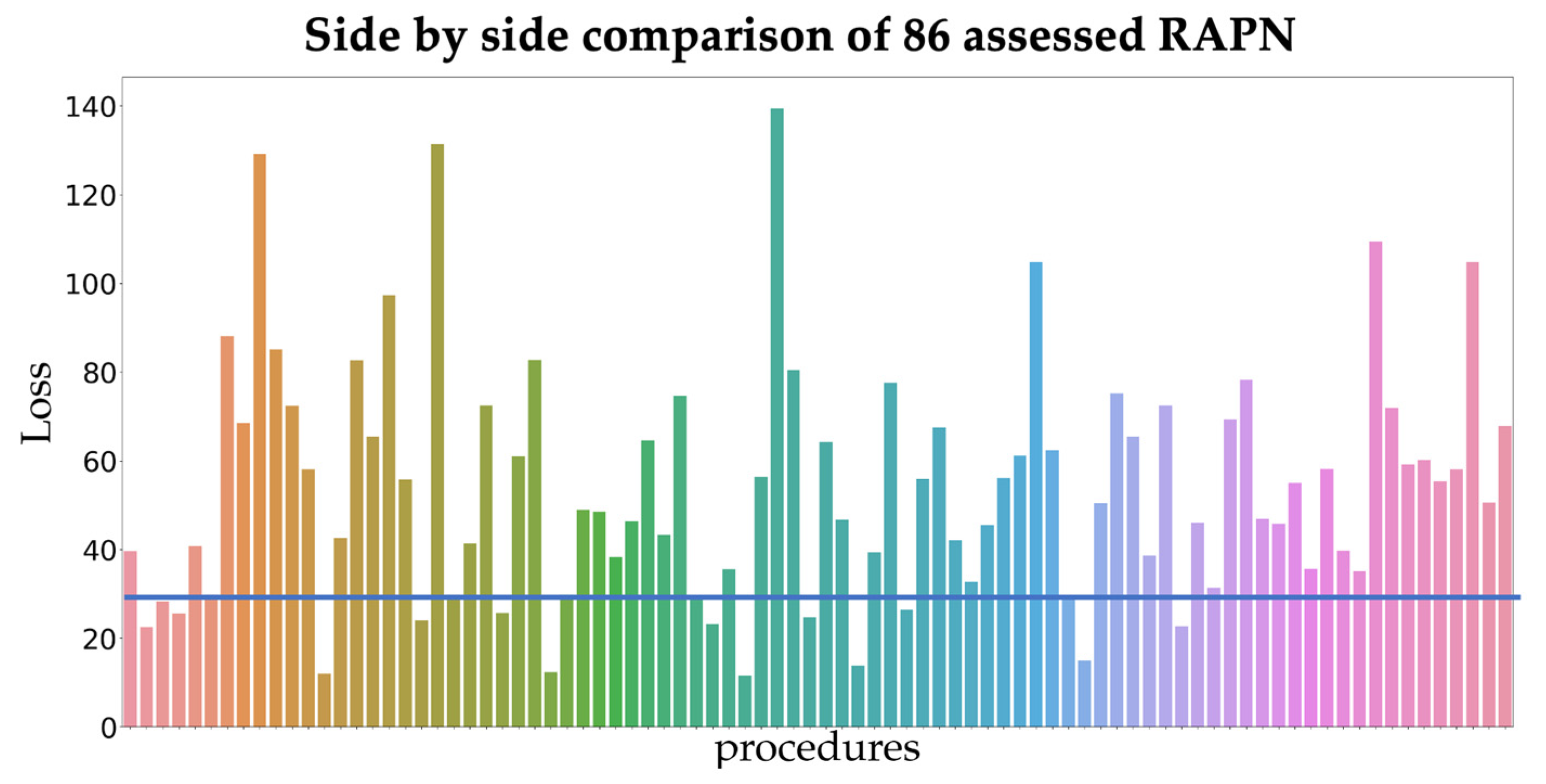

Touch Surgery does not provide phase assessment in case of cystic renal lesions, despite it being a similar technical approach. As such, the resulting final dataset for the side-by-side comparison was diluted to a total of 86 RAPN procedures.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for our concatenated manual (M) phase analysis and the TS analysis for 86 analyzed procedures.

At first sight, phase duration in both platforms are quite different. When looking at similarity between phase definitions on the full dataset, the 15 RAPN procedures with the least similarity (consistent with a loss lower than 29) were analyzed in depth for phase assessment differences.

Figure 2 shows the loss for all procedures.

The following recurring discrepancies were withheld in poorly corresponding videos. Although port insertion and surgical access was not always recorded, it was not annotated in TS in half of the cases, leading to a longer duration of ‘Colon Mobilization’. From ‘Colon Mobilization’ onwards, we do note that in general the same number of phases are annotated. A clearly differing visual definition is present in ‘Kidney mobilization’ and ‘Tumor identification’. Ultrasound use and guided demarcation forms an important part of tumor identification and in certain procedures, ultrasound (US) is initiated before opening of Gerota's fascia. In the Manual phase analysis, this US usage is considered a subphase of 'Tumor identification' and thus marks the beginning of this phase. Touch Surgery does not always recognize US usage as part of 'Tumor identification' yet, resulting in a missed phase initiation. Touch Surgery recognizes the start of the 'Tumor identification' phase when the US is used for the second time when the renal parenchyma with tumor zone is already freed from peri-renal fat. This also results in longer ‘Tumor Identification’ phases in the manual assessment. As the manual assessment is more nuanced and the definition is different, a side-by-side comparison on accuracy is irrelevant. This differing definition impacts all phase durations before the onset of hilar clamping and tumor excision, which makes phase duration comparison for other phases before ‘Hilar Clamping’ unreliable.

We do note that combining all surgical manipulations before ‘Hilar Clamping’, this is the combination of ‘Port Insertion and Surgical Access’, 'Colon Mobilization', 'Identification of Anatomical Landmarks', 'Hilar Dissection' and ‘Kidney Mobilization’, does have very similar mean and median durations (means are 76,5 and 76,3 minutes, medians are 62 and 64,9 minutes for respectively M and TS assessment).

The next important surgical landmark entails tumor excision, which is most often performed after hilar clamping. We see here that of all 100 procedures, 77 procedures were performed off-clamp. Touch Surgery did not indicate tumor excision and tumor retrieval in 2 cases due to our anonymization protocol. Both cases had patient-specific CT scan or 3D model info in the console view which was anonymized before upload. Despite being a clear drawback for comparison, these phases should not impact median times, where we note similar trends. The combined duration of ‘Hilar clamping’ and ‘Tumor Excision’ is very similar. We find mean and median combined values of respectively 9,2 and 6,9 minutes for manual assessment; 9,9 and 8,6 minutes for TS assessment. The main factors attributing to longer ‘Tumor Excision’ times in TS are twofold. TS includes application of hemostatic agents, which is excluded in our manual assessment and the TS ‘Tumor Excision’ phase starts as soon as the kidney is manipulated after clamping, where in our assessment it only starts when the blunt dissection takes place. This also results in a longer manual ‘Hilar Clamping’ duration.

After tumor excision, we enter the last procedural part in which the kidney is reconstructed after specimen retrieval. ‘Specimen Retrieval’ has very similar durations, nonetheless we note that, despite our best efforts, both our manual assessment and TS missed to annotate one specimen retrieval, albeit in different procedures. Similar to ‘Hilar Clamping’, the ‘Hilar Unclamping’ phase is once more shorter in TS. The main attributing factor is the rennoraphy starting point definition. In TS, this phase starts when needles are brought closeby the parenchyma and thus this ends the unclamping. In our assessment, this phase only starts at the first parenchymal suture. This is also reflected in shorter renorraphy times for our assessment and confirms the narrower definition. ‘Specimen retrieval and Closure’ has a similar time range and includes the renal retroperitonealisation. The ‘Operation Finished’ definition is more precise in our assessment and marks when the camera is removed from the abdomen for the last time, whilst for Touch Surgery this is simply the end of the video, resulting in an empty phase duration.

3.2. Clinical data correlation exploration

Prior abdominal surgery did not significantly impact any of the phases’ duration, independent of the phase assessment methodology (TS or M). Likewise, no significant impact was found for age, gender, pT stage, histology type or pre/post-operative renal function. The post-operative complication rate was too low to find any correlations.

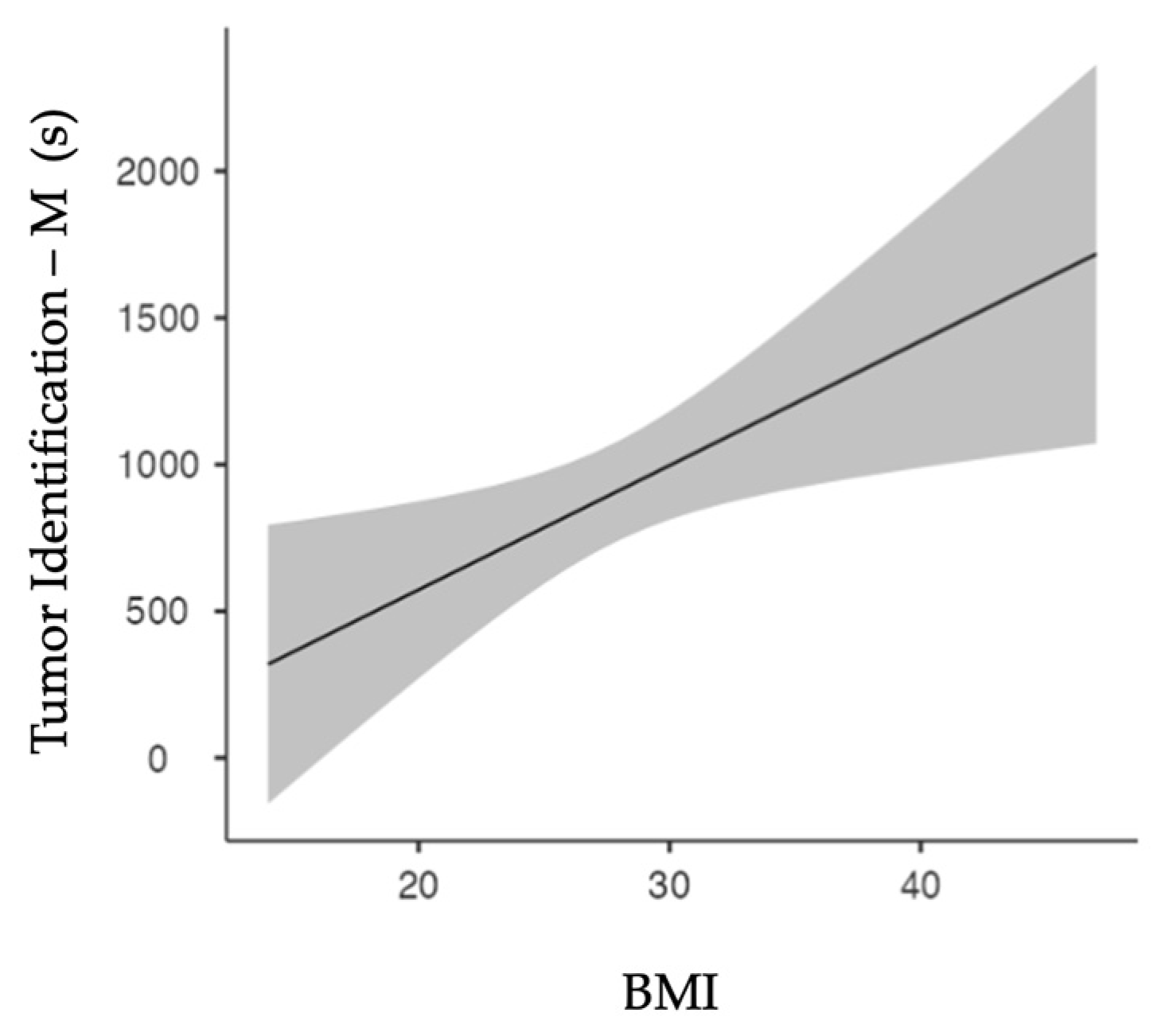

Spearman’s test showed a significant correlation (p=0.011) between patients’ BMI and the ‘Tumor Identification’ duration for manually assessed cases only.

Figure 3 shows the linear regression model. Increased BMI results in increased ‘Tumor Identification’ periods (p=0.011).

When assessing tumor complexity according to the PADUA scores, we see that ‘Renorrhaphy’ duration has a significant positive correlation with PADUA score (p<0.001 for both Touch Surgery and manual assessment). Likewise, ‘Tumor Excision’ was significantly correlated with PADUA scores, nevertheless only in manual assessment (p<0.001). At linear regression, PADUA score confirmed a positive correlation with ‘Renorrhaphy’ duration (p<0.001 for both TS and M assessment,

Figure 4a and 4b, respectively).

Figure 4c depicts the positive correlation between manual assessment of ‘Tumor Excision’ and Padua score (p<0.001).

4. Discussion

Defining visual clues for phase analysis is a repetitive process in which the multicentric approach allowed for a more robust and precise definition. Several iterations where required before agreeing on a final template as provided in

Table A1, which was then used for full dataset investigation. Despite our best efforts in checking all procedures fivefold, post-hoc data analysis revealed we still missed annotating one phase. As such, phase annotation is a time-intensive effort which reveals the clinical need for intelligent systems which can support this automatically and consistently.

When comparing our manual platform and the Touch Surgery platform for RAPN phase assessment, we identify three key items:

Firstly, the lack of analyzing renal cysts in Touch Surgery is an apparent drawback as it immediately discards 14% of the cases, despite having identical surgical technique and approach.

Secondly, when analyzing both platforms for the remaining 86 procedures, we identify the lack of uniform and transparent definition as the main inhibitor for in depth side-by-side comparison. Touch Surgery does not provide details on the phase analysis process. It is unknown whether the assessment happens fully autonomous, semi-autonomous or fully manually. In the latter case, nothing is known about the expertise level of annotators, their training, or their interrater reliability. The platform provides no information on the used visual phase cues. On the other hand, no public consensus exists for objectively defined visual phase cues. Despite having based our definition on a published consensus for phase metrics, defining visual cues requires more details and as such there is a clear mismatch between both definitions.

Thirdly, assessment of the most differing procedures as identified by the loss function, shows that phase combinations and evaluation of specific subphases results in greater similarity. As such, large surgical entities are annotated in a similar fashion. When assessing the full procedure, 3 major operative parts (preparation for tumor excision, tumor excision and the hemostasis and closure) were found to be similar. Nevertheless, they are insufficiently granular for immediate outcome correlation research.

BMI and ‘Tumor Identification’ duration correlate positively, which can be suspected as higher BMI often involves more intraabdominal fatty tissue. As the kidney is surrounded by perinephric fat, tumor identification on the renal surface can indeed be more tedious. This correlation was not withheld in the TS definitions. This can be attributed to the apparent TS definitions of only annotating ‘Tumor Identification’ when the kidney is already fully exposed. Another attributing factor is our removal of our echography TilePro™ segments in the TS group for anonymization purposes. Nevertheless, these segments were often correctly picked-up inside the TS platform, starting when ultrasound entered the body and ending upon ultrasound removal.

When tumor complexity rises, e.g. because of larger size or endophytic nature, as expected tumor excision duration also increases. Likewise, ‘Renorraphy’ duration increases with tumor complexity. Big or deep tumor can indeed leave large or difficult to reach renal resection beds, which can effectively be more difficult to reconstruct or obtain adequate hemostasis. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that these correlations are only withheld in manual assessment. The missing correlation for TS might be attributed to the broader ‘Tumor Excision’ definition which includes hemostatic agent applications. Touch Surgery retrieved statistical significance with renorraphy duration only. We do note that 2 out of 86 cases were irrelevant for tumor excision comparison, given the pre-upload anonymization. Furthermore, the manual data analysis was performed on 14 cases more.

5. Conclusions

When assessing surgical phase duration for clinical relevance, a very nuanced description and definition of phase starting points is required. Metrics based training curricula can help in identifying the clinically most relevant phases. Sufficient granularity in surgical phases annotation is a stringent requirement for thorough exploration of clinical relevance. Currently, due to its blackbox nature and its omission of cystic lesions, the Touch Surgery platform cannot support research aimed at evaluating clinical outcomes or surgical performance in RAPN using proficiency-based metrics. Commercially generated annotations can however provide general surgical information and are expected to facilitate surgical video navigation outside clinical trials.

Assessment according to our metrics-based definitions resulted in more clinical correlations. Firstly, this strengthens our idea that, despite their practicality and ease of use, commercial annotations are not ready for primetime use in investigating possible clinical correlations. Secondly, this suggests that expert consensus methods for choosing phase definitions such as derived from metrics-based training curricula can help in standardization. Given the lack of visual phase definition consensus, this manuscript might act as a guide towards better standardization for future phase analysis projects in RAPN. Likewise, we hope it inspires future projects in robot-assisted surgery assessment.

As this work explores surgical phase duration correlation with patient characteristics, it is important to note that correlations do not imply causations and that the value of this work is more hypothesis generating. The retrospective nature of this study further adds to this.

Lastly, this work can serve as the necessary basis for automated phase detection in RAPN. Here, deep learning computer vision algorithms take in phase duration data combined with video data to automatically assess and define surgical phases. This is in turn an enabler towards fully automated surgical scene understanding [

21] which unlocks a myriad of other possible applications. Given the time-intensive nature of manual annotations, automated phase detection can also pave the way for larger patient cohort investigations. This is a needed step towards gathering more evidence.

6. Patents

Not Applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D.B; methodology, P.D.B, J.S., R.D.G.; software, J.S., W.B.; validation, P.D.B, F.P.; formal analysis, P.D.B, F.P., M.D..; investigation, P.D.B., M.D.; resources, C.D., C.V.P., A.G., K.D., A.M ; data curation, K.M., T.O., A.W., K.V.R., C.V.S., M.P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D.B., F.P.; writing—review and editing, P.D.B., R.F., E.C., C.V.P.; visualization, W.B., J.S., F.P.; supervision, K.D., A.M.; project administration, P.D.B.; funding acquisition, K.D., A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following grants: 1. Baekeland grant of Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship (VLAIO), grant number HBC.2020.2252 (Pieter De Backer); 2. Ipsen NV grant, grant number A20/TT/1655 (Karel Decaestecker)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of OLV Hospital Aalst-Asse-Ninove (protocol code B12201941209 on 03/09/2019) and Ghent University Hospital (protocol code B6702020000442 on 21/08/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to full data anonymization (General Data Protection Regulation art. 26) in this retrospective study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available as open sourcing all videos for general usage was not declared in the IRB approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mieken Vereecken for her administrative help related to the manuscript. We also thank Luca Sarchi for feedback on definition on the computer vision clues for phases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

RAPN Phase list with the according visual cues.

Table A1.

RAPN Phase list with the according visual cues.

| |

RAPN phase |

Starting point |

Visual starting cue |

Phase characteristics |

| 1 |

Port Insertion and Surgical Access |

Inside abdomen |

When the video starts in the abdominal space or when the camera is inserted into the abdominal space and there is no visual of the trocar |

Port placement

Instrument insertion

Adhesion removal |

| 2 |

Colon (and Spleen) Mobilization |

Identification of the mesenteric line

A*: spleen mobilization |

Right kidney: when the camera points between the liver and the right paracolic gutter

Left kidney: when the camera points between the paracolic gutter and the kidney contour can be seen

A* when instruments mobilize the spleen |

Opening of peritoneum

Adhesion removal |

| 3 |

Hilar Control General |

Identification of gonadal vein

A*: start dissection of renal vein |

Identification of gonadal vein: when the gonadal vein can be partially seen

A* when the renal vein can be partially seen |

Dissection of main renal artery

Start isolation of main renal artery**

Vessel loop on main renal artery

Hemolock clip on vessel loop |

| 4 |

Selective Hilar Control |

Start dissection of other than main renal artery |

When the artery can be partially seen |

Dissection of selective renal artery

Start isolation of selective renal artery**

Vessel loop on selective renal artery

Hemolock clip on vessel loop |

| 5 |

Kidney Mobilization |

Start opening Gerota's fascia |

When a new incision in the perirenal fat, representing the surrounding renal fascia (Gerota’s fascia), is made |

Dissection of kidney surface |

| 6 |

Tumor Identification |

Start demarcation of tumor

A*: ultrasound start |

When the monopolar curved scissors uses coagulation to delineate tumor position, whilst remaining on the kidney surface

A* when the ultrasound probe is pressed against the parenchyma and the ultrasound image can be seen |

Use of ultrasound probe

Tumor demarcation |

| 7 |

Hilar Clamping |

Bulldog clamp on main artery

A*: bulldog clamp on selective artery |

When the bulldog clamp is positioned on the renal artery

When the bulldog clamp is positioned on a first or higher order renal artery |

Use of bulldog clamp

Use of ICG |

| 8 |

Tumor Excision |

Start blunt dissection |

When the monopolar curved scissors cut function is used to cleave open the renal parenchyma, or the tumor is being separated from the renal parenchyma whilst the scissor blades are closed |

Resection of tumor |

| 9 |

Specimen Retrieval |

Free tumor base |

When the tumor base is completel free from tumor |

Specimen retrieval |

| 10 |

Inner Renorrhaphy |

First inner renorrhaphy stitch |

When the needle (not the needle wire) has fully exited the parenchyma after its first bite |

Inner renorrhaphy |

| 11 |

Hilar Unclamping |

Bulldog clamp off main artery

A*: bulldog clamp off selective artery |

When the bulldog clamp is opened on the main renal artery

A* when the bulldog clamp is opened on the selective artery |

Hilar unclamping |

| 12 |

Outer Renorrhaphy |

First outer renorrhaphy stitch |

When the needle (not the needle wire) has fully exited the parenchyma after its first bite |

Outer renorrhaphy

Use of hemostatic agent |

| 13 |

Specimen Removal and Closing |

Tumor bagging |

When the tumor falls halfway into the endobag |

Tumor bagging

Use of hemostatic agent |

| 14 |

Instrument Removal |

Vessel loop removal

A*: bulldog clamp removal |

When the assistant fully grasps the already cut vessel loop using a laparoscopic instrument

When the assistant fully grasps the bulldog clamp using a laparoscopic instrument |

Instrument removal |

| 15 |

Retroperitonalisation of the Kidney |

Passing first stitch in parietal peritoneum |

When the needle (not the needle wire) has fully exited the fatty tissue after its first bite. |

Suturing parietal peritoneum |

| 16 |

End of Operation |

Tension hem-o-lok retroperitonealisation

A*: secure suture retroperitonealisa-tion** |

When the non-absorbable clip is pressed against the peritoneum while the needle wire is still under tension

A* When the last clip is fully applied on the suture wire |

Removal of robotic instruments**

Drain placement

Camera out of body

Camera stop |

Figure A1.

Screenshot of the in-house developped HTML file for phase analysis.

Figure A1.

Screenshot of the in-house developped HTML file for phase analysis.

References

- S. Cheikh Youssef et al., “Evolution of the digital operating room: the place of video technology in surgery,” Langenbecks. Arch. Surg., vol. 408, no. 1, p. 95, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. R. Grenda, J. C. Pradarelli, and J. B. Dimick, “Using Surgical Video to Improve Technique and Skill,” Ann. Surg., vol. 264, no. 1, pp. 32–33, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Farinha et al., “International expert consensus on metric-based characterization of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy,” Eur. Urol. Focus, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 388–395, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Farinha et al., “Objective assessment of intraoperative skills for robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN),” J. Robot. Surg., Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Balvardi et al., “The association between video-based assessment of intraoperative technical performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review,” Surg. Endosc., vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 7938–7948, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Langerman and T., P. Grantcharov, “Are We Ready for Our Close-up?: Why and How We Must Embrace Video in the OR,” Ann. Surg., vol. 266, no. 6, pp. 934–936, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Zeeshan, A. E. Dembe, E. E. Seiber, and B. Lu, “Incidence of adverse events in an integrated US healthcare system: a retrospective observational study of 82,784 surgical hospitalizations,” Patient Saf. Surg., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 23, May 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Maier-Hein et al., “Surgical data science for next-generation interventions,” Nat Biomed Eng, vol. 1, no. 9, pp. 691–696, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Garrow et al., “Machine Learning for Surgical Phase Recognition,” Ann. Surg., vol. 273, no. 4, pp. 684–693, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gibaud et al., “Toward a standard ontology of surgical process models,” Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg., vol. 13, no. 9, pp. 1397–1408, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Lavanchy, C. Gonzalez, H. Kassem, P. C. Nett, D. Mutter, and N. Padoy, “Proposal and multicentric validation of a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery ontology,” Surg. Endosc., vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 2070–2077, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023. ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6. EAU Guidelines Office, Arnhem, The Netherlands. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines/, 2023.

- Bravi et al., “The IRON Study: Investigation of Robot-assisted Versus Open Nephron-sparing Surgery,” Eur Urol Open Sci, vol. 49, pp. 71–77, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Guerrero, A. V. O. Claro, M. J. Ledo Cepero, M. Soto Delgado, and J. L. Álvarez-Ossorio Fernández, “Robotic versus Laparoscopic Partial Nephrectomy in the New Era: Systematic Review,” Cancers, vol. 15, no. 6, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mottrie et al., “Objective assessment of intraoperative skills for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP): results from the ERUS Scientific and Educational Working Groups Metrics Initiative,” BJU Int., vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 103–111, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mazzone et al., “A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on the Impact of Proficiency-based Progression Simulation Training on Performance Outcomes,” Ann. Surg., vol. 274, no. 2, pp. 281–289, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B. P.-H. Chen, I. M. Soleas, N. C. Ferko, C. G. Cameron, and P. Hinoul, “Prolonged Operative Duration Increases Risk of Surgical Site Infections: A Systematic Review,” Surg. Infect., vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 722–735, Aug/Sep 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. S. Kim et al., “Surgical duration and risk of venous thromboembolism,” JAMA Surg., vol. 150, no. 2, pp. 110–117, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Jackson, J. J. Wannares, R. T. Lancaster, D. W. Rattner, and M. M. Hutter, “Does speed matter? The impact of operative time on outcome in laparoscopic surgery,” Surg. Endosc., vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 2288–2295, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. De Backer et al., “A Novel Three-dimensional Planning Tool for Selective Clamping During Partial Nephrectomy: Validation of a Perfusion Zone Algorithm,” Eur. Urol., Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. De Backer et al, “Automated intra-operative video analysis in robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: Paving the road for Surgical Automation,” presented at the ERUS23 20th Meeting of the EAU Robotic Urology Section, Florence.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).