1. Introduction

HMGB1 was first isolated among other “high-mobility group” proteins in 1973, so designated because of their high mobilities in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis relative to other extracted non-histone chromosomal proteins [

1]. It is a 30 kDa protein with two nuclear localization signals (NLSs) and an acidic tail of 30 amino acids (

Figure 1). HMGB1 interacts with DNA and other nuclear proteins to regulate replication [

2], translation [

3], and DNA repair [

4]. Beyond its nuclear function, HMGB1 has a dual role as a danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) by mediating an immune response when secreted from activated immune cells [

5] or passively secreted from necrotic cells [

6]. Secreted HMGB1 can activate the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) [

7] as well as toll-like receptor (TLR)-2 and TLR-4 [

8]. Among other consequences, activation of these receptors initiates cell-signaling cascades that activate nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), a key transcription factor in both innate and adaptive immune responses [

8]. The mechanisms that regulate the shift between HMGB1’s dual nuclear and DAMP activities and their impact in human disease have been the subject of much of the research into HMGB1 as a potential therapeutic target [

9,

10].

The role of HMGB1 in the etiology of cancer is complex because of its involvement in both DNA repair and extracellular signaling [

11,

12]. Growth and metastasis of tumors is thought to be sustained by signaling from HMGB1 and other DAMPs released by necrotic cells following chemotherapy or radiation [

13,

14]. Extracellular HMGB1 promotes invasion and metastasis by stimulating cell migration and by mediating interactions among components of the extracellular matrix and the tumor microenvironment. Due to these functions, circulating HMGB1 is considered to be an indicator of tumor progression in many cancers [reviewed in [

15]]. However, intracellular HMGB1 also has effects on tumor progression by mediating DNA repair mechanisms [

4] and NF-κB signaling [

8]. Although HMGB1 overexpression has been reported to be common in many types of cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

16,

17], breast cancer [

18], colorectal cancer [

19], pancreatic cancer [

20], and malignant mesothelioma [

21], the ability of different types of tumors to produce their own pool of circulating HMGB1 remains uncertain. In addition, increased tumor HMGB1 mRNA and protein expression corelates correlates with the progression of NSCLC patients [

22]. The mechanisms that regulate HMGB1 localization to the nucleus, cytosol, and extracellular space are unclear and may vary among different contexts and cell types.

Platinum-based chemotherapies such as cisplatin and carboplatin are important therapeutic options for the treatment of NSCLC [

23,

24]. The cytotoxicity of platinum drugs in lung cancer cells is thought to result from DNA damage, especially 1,2-d(GpG) intrastrand crosslinks, which interferes with DNA replication and eventually activates apoptosis [

25]. HMGB1 secretion during the treatment of NSCLC has been reported, although the studies were flawed by the analysis of HMGB1 in serum instead of plasma [

26,

27]. Regrettably, a significant number of studies of HMGB1 secretion have been conducted using serum instead of plasma [

28] Our study utilizing matched plasma and serum samples from twenty healthy control subjects revealed that HMGB1 is released when blood is allowed to clot and form serum [

15]. The process of clotting led to a substantial 30-fold increase in HMGB1 concentrations, escalating from 0.2 ng/mL in plasma to 6 ng/mL in serum [

15]. Consequently, the reliable detection of an elevation in HMGB1 release from tissues into the plasma becomes very difficult to interpret when the protein is quantified in serum. Measurements conducted solely in serum only indicate the ability of blood cells to generate HMGB1 and fail to reflect the actual circulating levels of HMGB1. Despite this fundamental issue, serum is still frequently employed in biomarker studies to quantify HMGB1 secreted from tissues in various pathological conditions.

Various post-translational modifications (PTMs) of HMGB1 have been implicated as mediators of HMGB1 mobility and secretion. These modifications include acetylation [

29,

30,

31,

32] methylation [

33], poly-ADP ribosylation [

34], serine phosphorylation [

30,

31], and cysteine (Cys) oxidation [

31]. A paradigm has emerged relating various circulating HMGB1 proteoforms with corresponding mechanisms of release, where hyperacetylated HMGB1 undergoes regulated secretion from immune cells during inflammation [

3], and hypoacetylated HMGB1 is passively released from necrotic cells after tissue injury [

35]. Similarly, secretion of the HMGB1 proteoform with an intramolecular disulfide between Cys-23 and Cys-45 (

Figure 1) has been associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, whereas reduced HMGB1 with no intramolecular disulfide bond has been associated with passive released from necrotic cells [

36,

37]. However, many of the studies supporting this conceptual framework have been discredited or retracted [reviewed in [

28]. Therefore, we considered that it was important to definitively characterize distinct patterns of HMGB1 PTMs arising from chemotherapy-induced HMGB1 secretion.

PTMs could play a role in mediating the mobility of HMGB1 in cisplatin treated cells. For example, HMGB1 is a substrate of poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 1 (PARP1) [

38,

39], and DNA damage is a potent inducer of PARP1 activity [

38]. Therefore, secreted HMGB1 could conceivably be ADP-ribosylated prior to secretion. Similarly,

in vitro experiments have demonstrated that acetylation and phosphorylation of HMGB1 can modulate its DNA-binding properties [

40,

41]. Furthermore, the binding affinity between cisplatin modified DNA and reduced HMGB1 is 10-fold greater than with oxidized HMGB1

in vitro [

42], which suggests that differences in cellular redox state could contribute to variability in cellular response to platinum drugs. Therefore, characterizing the PTMs and oxidation state of HMGB1 is necessary to fully understand the mechanism by which it is secreted from NSCLC cells resulting from platinum drug treatment.

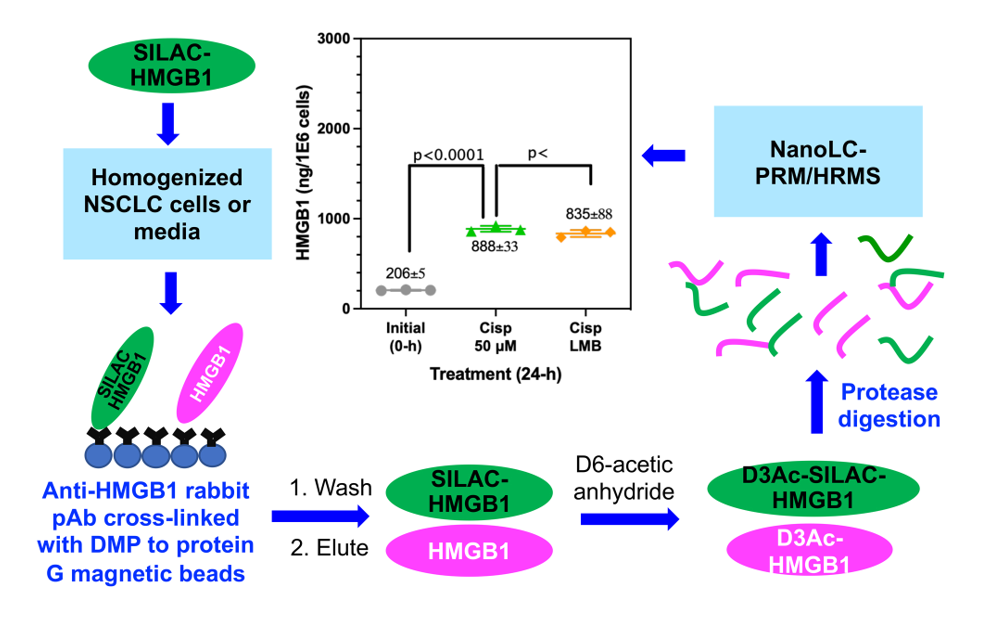

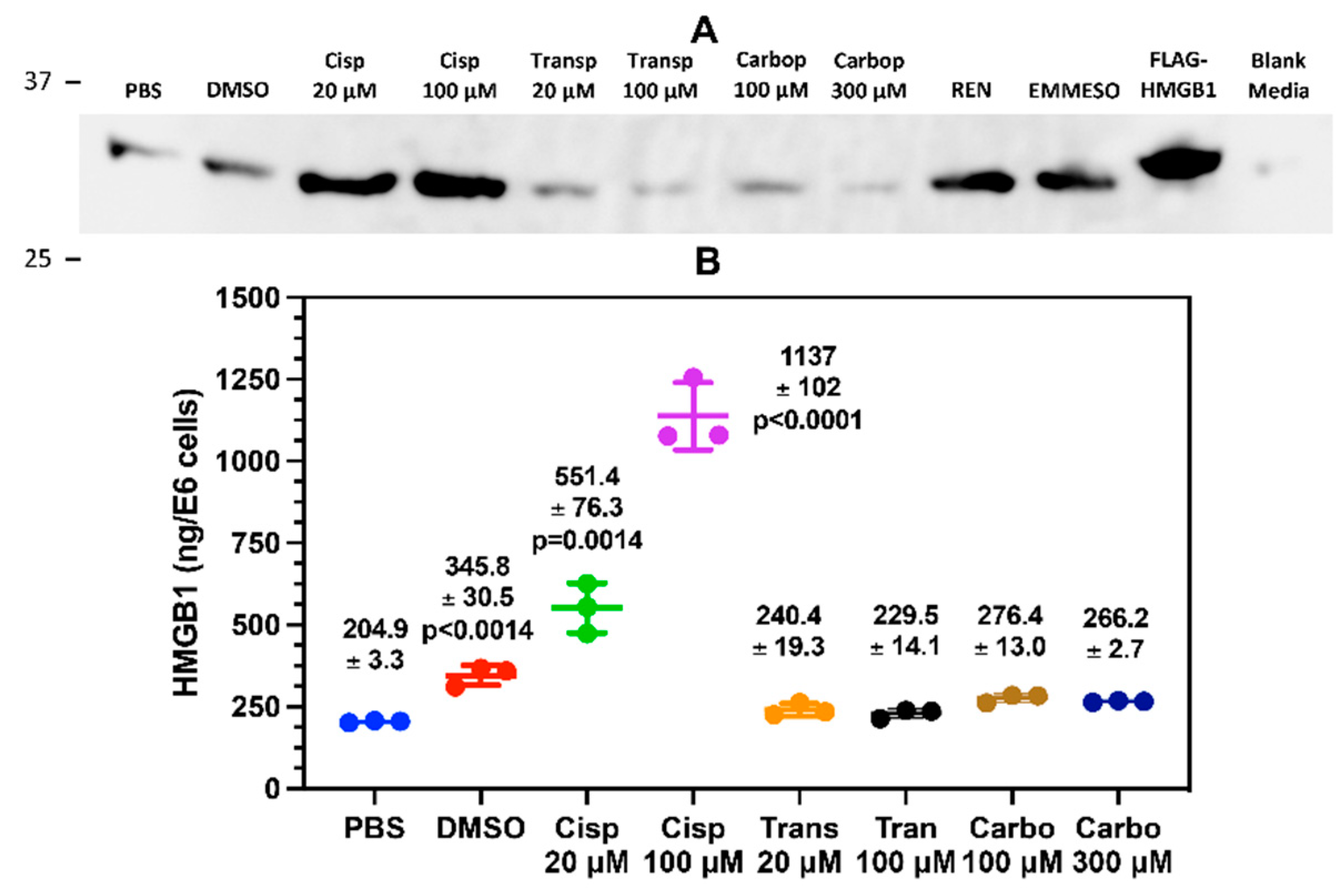

In the current study, we determined whether platinum drugs could induce regulated HMGB1 translocation and secretion in the human A549 NSCLC cell line. We report a sensitive and specific assay to quantify HMGB1 proteoforms in cells and cell culture media using immunopurification (IP) with magnetic beads covalently crosslinked with dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP) to an HMGB1 polyclonal antibody (pAb) coupled with nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-PRM/HRMS). A differential alkylation approach with iodoacetamide (IAA) and N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) modification of Cys residues was used in combination with a [13C15N]-HMGB1 internal standard to characterize and accurately quantify the redox state of HMGB1 Cys residues. Post-IP acetylation with D6-acetic anhydride was used to convert all acetylated and nonacetylated HMGB1 into a single molecular form, to characterize and accurately quantify endogenous acetylation of HMGB1 lysine residues. These sensitive and specific methods revealed, surprisingly, that cisplatin, but not carboplatin or transplatin, could induce HMGB1 release from A549 cells prior to cell death or loss of plasma membrane integrity. Furthermore, the secretion was mediated by nuclear transport rather than by acetylation, ADP-ribosylation, phosphorylation, or oxidation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Reagents and solvents were LC/MS-grade quality unless otherwise noted. Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI) supplied LC/MS grade water and acetonitrile. Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA): [

13C

615N

2] lysine, [

13C

915N

1] tyrosine and [

2H

6] acetic anhydride. EMSCO/FISHER (Philadelphia, PA) supplied Pierce Protein A/G magnetic agarose beads, formic acid, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS),. Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) supplied ammonium hydroxide (Optima). MilliporeSigma (Billerica, MA) supplied the anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb raised against the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1 (H9539), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail, L-cysteine, chloramine-T hydrate, triethanolamine and ethanolamine. Abcam (Waltham, MA) supplied the rabbit anti-HMGB2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) raised against an N-terminal HMGB2 peptide of unspecified sequence (ab124670). Anti-histone H3 rabbit pAb (cat. # PA5-16183) and anti-fatty acid synthase (FASN) rabbit pAb (cat. # MA5-14887) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Novus Biologicals (Centennial, CO) supplied early apoptosis-specific stain polarity Sensitive Indicator of Viability and Apoptosis (pSIVA) and propidium iodide (PI) fluorescent stains. Promega (Madison, WI) supplied mass spectrometry grade trypsin endo-proteinase. Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) supplied (TCEP), endoproteinase Glu-C from

Staphylococcus aureus V8, Tris HCl pH 8 solution, and dimethyl pimelimidate DMP. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was supplied by Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA) supplied the Western Lightning Plus electrochemical luminescence (ECL) reagent. REN and EMMESO malignant mesothelioma cells were a kind gift from Dr. Steven M. Albelda, University of Pennsylvania. Platinum drugs were dissolved in PBS because dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) can cause oxidative stress and apoptosis [

43,

44,

45].

2.2. Platinum treatments and lung cancer cell models

A549 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium/Ham's F-12 Nutrient Mixture media with 15 mM HEPES and 2 mM glutamine (Thermo Fisher Gibco, 11330-032), supplemented with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Gibco 15140-122) and 5% FBS (Sigma Aldrich F2442). Cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 106 cells per 35x10mm plate and cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cisplatin, transplatin, and carboplatin were prepared as 5 mM stocks in PBS with 30 s pulse sonication and diluted into 10 mL cell culture media for treatment. After 24-h, media was collected and subjected to centrifuge to remove any cell debris (1000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was transferred to fresh 15-mL tubes. REN and EMMSO cell lines were cultured in RPMI Media with 2 mM glutamine, supplemented with 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin and 5% FBS.

2.3. Expression and purification of stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) labeled HMGB1

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 SILAC medium containing 0.5 mM [13C615N2]-lysine and 0.2 mM [13C915N1]-tyrosine for at least three passages. HMGB1-FLAG tag plasmid (Origene RC205918) was transfected into HEK293T cells by use of lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected cells were harvested in NP-40 lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 mM DTT, dithiothreitol (DTT)] containing protease inhibitor cocktail after 48-h transfection. Harvested cells were subjected to pulse sonication on ice (30 s) and centrifuged (17720 g, 15 min, 4 °C) before cell lysate supernatant was carefully transferred to fresh tubes. Anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma Aldrich) were washed twice with NP-40 lysis buffer and added to each tube and incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation. After removal of the supernatant, the beads were washed with the following solutions sequentially: NP-40 lysis buffer × 3, 0.5 M KCl in NP-40 lysis buffer × 1, 1 M KCl in NP-40 lysis buffer × 1, and PBS × 2. SILAC HMGB1 was eluted from beads with glycine elution buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5) for 20 min and subsequently with 10 mM NH4HCO3 for 10 min. Aliquots of 250 mM NH4HCO3 were added to pooled eluent until pH was neutral.

2.4. Crosslinked magnetic bead immunoprecipitation and trypsin digestion

Protein A/G magnetic beads were gently vortexed and 40 μL dispersed beads were transferred to two 2-mL protein LoBind microcentrifuge tubes (Eppendorf, 022431102). Beads were washed twice with PBS and twice with Buffer A (0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4). Each tube was incubated with 100 μL buffer A and 100 μL of either H9539 (Sigma Aldrich) or ab79823 (Abcam) anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb for 2-h at 4 °C with gentle rotation, followed by the addition of 400 μL buffer A and further overnight incubation at 4 °C. The pAb solutions were removed and beads were gently washed twice with buffer A and then twice with 1 mL of cross-linking buffer (0.2 M triethanolamine, pH 8). After washes, the beads were suspended in 1 mL of 25 mM DMP prepared in cross-linking buffer and incubated at room temperature for 1-h with gentle rotation. The DMP solution was removed, and the beads were washed with 1 mL of blocking buffer (0.1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.2) and then incubated at room temperature for 30 min in 1 mL of blocking buffer. The blocking buffer was then removed, and the beads were washed twice with PBS. The PBS was removed, and the beads were incubated in glycine elution buffer for 15 mins at room temperature with gentle rotation to remove any residual non-crosslinked antibody from the beads. After removing the glycine elution buffer and two final washes with PBS, beads with both HMGB1 pAbs were equally aliquoted into fresh protein LoBind tubes containing 1 mL A549 media, SILAC FLAG-HMGB1 internal standard (800 ng) and 100 μL IP lysis buffer. Media immunoprecipitation samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation and gently washed twice with PBS. HMGB1 was eluted with 15 min vigorous shaking of beads in 100 μL elution buffer and then with 5 min vigorous shaking 50 μL 10 mM NH

4HCO

3. The two eluents of each sample were combined and subsequently neutralized with 50 μL 250 mM NH

4HCO

3. The combined elute was dried under N

2 for subsequent resuspension in 25 mM NH

4HCO

3 pH 8 and digested with 400 ng trypsin protease per sample overnight at 37 °C with 600 RPM shaking. We have also previously shown that the IP procedure can efficiently isolate acetylated forms of HMGB1 [

15].

2.5. Cell Fractionation

Nuclear and cytosolic subcellular fractions were prepared with ProteoExtract Subcellular Proteome Extraction Kit (Millipore Sigma, 539790) following a protocol adapted from the manufacturer’s instructions. After removing cell culture media, cell plates were gently washed twice with PBS and aspiration. Cells were gently lifted in 1 mL PBS and pelleted by centrifugation (600 g, 6 min, 4° C). The PBS supernatant was discarded, and cells were resuspended in 300 µL wash buffer and gently rocked (5 min, 4 °C) before centrifugation (600 g, 6 min, 4° C). This entire wash step was repeated, and then the cells were resuspended in 200 µL extraction buffer I with 2 µL protease inhibitor and gently rocked (5 min, 4 °C) to extract the cytosolic fraction. The cell sample was subjected to centrifugation (1000 g, 10 min, 4° C) and the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube to provide the cytosolic fraction. The remaining pellet was resuspended in 200 µL provided Extraction Buffer II with 2 µL provided protease inhibitor and gently rocked (30 min, 4 °C) before centrifugation (6000 g, 10 min, 4° C). The supernatant was discarded, and the remaining pellet was resuspended in 100 µL extraction buffer III with 2 µL d protease inhibitor and 1 µL benzonase nuclease. The cell sample was gently rocked (10 min, 4 °C) to extract the nuclear fraction. Finally, the sample was subjected to centrifugation (7000 g, 10 min, 4° C) and the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube to provide the nuclear fraction. Cytosolic and nuclear fraction were tested with immunoblotting for FASN and Histone-3/Histone-4 antibodies, respectively.

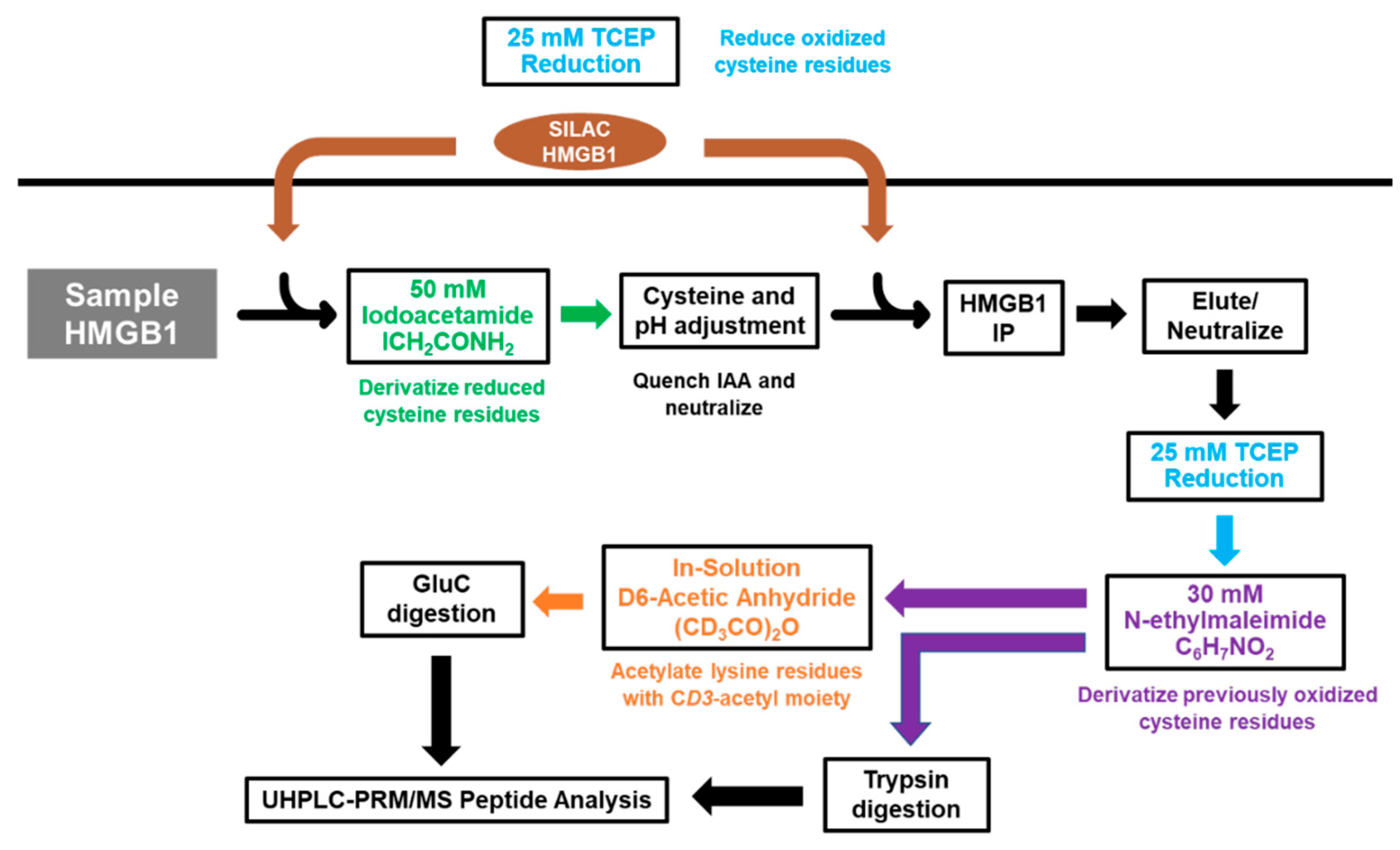

2.6. In-solution D6-acetic anhydride D3-acetylation and GluC and chymotrypsin digestion

Following glycine-HCl and NH4HCO3 elution of HMGB1, 100 μL 250 mM NH4HCO3 was added to each sample to elevate pH to 8.5. A working stock of D6-acetic anhydride (Cambridge Isotopes DLM-1162-PK) was diluted 14X in acetonitrile. Successive additions of 30 µL ammonium hydroxide (Fisher A470) and 140 µL working stock D6-acetic anhydride were added to each sample and incubated for 1-h at 37 °C with 600 RPM shaking. Following the acetylation reaction, samples were dried under N2 gas and resuspended in 200 μL 50 mM NH4HCO3 pH 8 for Glu-C protease digestion or 200 μL pH 8 for Chymotrypsin digestion.

2.7. IAA/NEM Cys derivatization

SILAC FLAG-HMGB1 stock was reduced in 50 mM TCEP (Thermo Scientific 77720) for 1-h at pH 7 and 30 °C with 600 RPM shaking. Then stock was diluted to 20 ng/µL with Optima water. Iodoacetamide was prepared away from light as a 500 mM stock in 250 mM NH

4HCO

3. Reduced SILAC FLAG-HMGB1 internal standard (400 ng) was added to each 1-mL A549 media sample, followed by addition of iodoacetamide solution for a 60 min reaction with 50 mM iodoacetamide at pH 8.5 and 25 °C in the dark with 600 RPM shaking. Residual iodoacetamide was then quenched with 100 mM L-Cys at pH 8.5 and 30 °C in the dark with 600 RPM shaking and the sample pH was brought to neutral with 0.5 M HCl (Fisher SA48-500). Then more reduced SILAC internal standard (400 ng) was added to each sample, followed by 100 µL IP lysis buffer for 1 mM BME final concentration. Both HMGB1 pAbs were equally aliquoted into samples for overnight immunoprecipitation and subsequent elution as previously described [

15]. Following elution, samples were reduced with a large excess (25 mM) TCEP for 1-h at pH 6 and 30 °C with 600 RPM shaking. The high concentration of TCEP prevented its consumption by any NAD

+ that might have been present in the eluate [

46]. N-ethylmaleimide was prepared in the dark as a 300 mM stock in water, and aliquots were added to each sample for a 60 min reaction with 30 mM N-ethylmaleimide at pH 7 and 25 °C in the dark with 600 RPM shaking. Samples were then dried under N

2 gas and tryptic digests were prepared as previously described [

15]. Glu-C digests were prepared following

D6-acetic anhydride acetylation steps as previously described [

15].

2.8. NanoLC-PRM/HRMS

UHPLC-MS was conducted on a Q Exactive HF hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled to a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLCnano with capillary flowmeter chromatographic system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The nanoLC system was composed of two columns, including a trapping column (Acclaim PepMap C18 cartridge (0.3 mm × 5 mm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific) for preconcentration purpose and an analytical column (C18 AQ nano-LC column with a 10 μm pulled tip (75 μm × 25 cm, 3 μm particle size; Columntip, New Haven, CT) to separate digested peptides; two pumps, including one nanopump delivering solvents to analytical column and a micropump connecting to the trapping column; and a 10-port valve. The nanoLC system was controlled by Xcalibur software from the Q-Exactive mass spectrometer. Samples (8 μL) were injected via microliter-pickup injection mode. Loading solvent was water/acetonitrile (99.7:0.3 v/v) containing 0.2% formic acid. A 10-port valve was set at the loading position (1−2) with the loading solvent at 10 μL/min for 3 min. The valve was then changed to the analysis position (1−10), at which time the trapping column was connected with the analytical column, and samples loaded on the loading column were back-flushed into the analytical column. The valve was maintained in the analysis position for 10 min before the end of the run, when it was switched to the loading position ready for the next analysis. Samples were eluted with a linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.35 μL/min: 2% B at 2 min, 5% B at 15 min, 35% B at 40 min, 95% B at 45−55 min, 2% B at 58−70 min. Solvent A was water/acetonitrile (99.5:0.5 v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid, and solvent B was acetonitrile/water (98:2 v/v) containing 0.1% formic acid. Nanospray Flex ion source (Thermo Scientific) was used. MS operating conditions were as follows: spray voltage 2500 V, ion transfer capillary temperature 250 °C, ion polarity positive, S-lens RF level 55, in-source collision-induced dissociation (CID) 1.0 eV. Both full-scan and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) were used. The full-scan parameters were resolution 60 000, automatic gain control (AGC) target 1 × 106 , maximum IT 200 ms, scan range m/z 290−1600. The PRM parameters were resolution 60 000, AGC target 2 × 105 , maximum IT 80 ms, loop count 5, isolation window 1.0 Da, NCE 25.

2.9. Quantification of HMGB1

Standard curve samples for tryptic and Glu-C digests of HMGB1 were prepared in media in triplicate. Recombinant HMGB1 was serially diluted in water and added to each media sample, followed by 800 ng SILAC internal standard. Two peptides per digest with three of the best nano-LC-PRM/HRMS transitions (H

31PDASVNFSEFSK

43 and G

115EHPGLSIGDVAK

127) were used to generate the standard curves with mean values of light-to-heavy ratios of peak areas of the non-Cys tryptic peptides (

Figure S1) from cisplatin-treated A549 media. A549 media HMGB1 was quantified by light-to-heavy ratios of peak areas using the generated standard curves (

Figure S2).

2.10. Quantification of HMGB1 lysine acetylation and Cys oxidation

Lysine acetylation was quantified as previously described [

15]. Briefly, PRM transitions for all possible CH

3-acetylated and C

D3-acetylated lysine residues were selected in the relevant samples from Glu-C and Chymotrypsin digests. The ratio of each light peptide peak area to the corresponding SILAC peptide peak area was calculated by Xcalibur QuanBrowser and qualified by Skyline. Cys oxidation was quantified by comparing the light-to-heavy ratio of peak areas in CAM- and NEM-modified Cys-containing peptides in the relevant trypsin and Glu-C digests. The CAM ratio compared to NEM ratio for a given Cys-containing peptide represents the ratio of reduced to disulfide oxidized Cys. The percentage of disulfide oxidation of a given Cys residue was calculated by NEM L/H divided by the sum of CAM L/H and NEM L/H and averaged for three PRM transitions per peptide.

2.11. Inhibitor co-treatments and ImageJ blot quantification

A549 cells were seeded in 6-well cell culture plates at 0.5 × 10

6 cells per well. Olaparib, GO-6983, Rottlerin, and KPT-330 were prepared as stocks in DMSO and LMB was provided in a 70/30 Methanol/Water (v/v) solution. Cell culture media was replaced fresh in each well right before inhibitor solutions and vehicle controls were added to each well. Following 3-h in the cell culture incubator, cisplatin or PBS vehicle control was added to each well for 24-h incubation. After 24-h media was collected and subjected to centrifuge to remove any cell debris (1000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant was transferred to fresh 2-mL tubes. Western Blots for HMGB1 were performed as previously described [

15]. Following imaging, Western Blots were quantified with ImageJ software by subtracting the membrane background signal from each blot using the same area and normalizing the signal to the calculated signal from the blot of HMGB1 (50 ng) on the membrane.

2.12. Trypan blue exclusion assay for A549 proliferation and viability

Trypan blue exclusion assays were performed on A549 cells evenly split into 35x10mm plates for a target density of 3 × 106 cells per plate. After all cells had re-adhered, they were treated with either cisplatin or PBS vehicle control (N = 5). For the trypan blue exclusion assays, cell culture media was aspirated, and cells were lifted by gentle washing with 2.5 mL trypsin-EDTA 0.5% and 2.5 mL PBS. Aliquots of 200 µL cell suspension were mixed with 200 µL trypan blue solution, and 2 × 11 µL of the mixture was then added to cell counter slides for analysis for cell count and viability by an automated cell counter (LUNA Automated Cell Counter L10001, Logos). The values obtained from the A and B sides of each slide were averaged and used to calculate the total viable and dead cells on a given plate.

2.13. Asp-N protease digests of A549 subcellular fractions

A549 subcellular fractions were collected as previously described [

47]. Partial aliquots were taken from each fraction for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample preparation. SILAC HMGB1 was distributed equally to each partial aliquot. SDS-PAGE was run as previously described [

15], followed by overnight Colloidal Blue staining (Thermo Fisher, LC6025). Following staining, gels were briefly rinsed with deionized water and gel pieces between 25 kDa and 37 kDa were excised from each lane to cut into approximately 1 mm

3 pieces and added to fresh microcentrifuge tubes. Gel pieces were rinsed by gentle shaking in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50% acetonitrile by volume and the solution aspirated before the pieces were dried with 200 µL aliquots of acetonitrile and gentle shaking. After drying the acetonitrile was aspirated and 5 µL

D6-acetic anhydride was to each tube of gel pieces to absorb, followed by 50 µL of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate. After absorption, 150 µL of 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 15 µL were added to each tube to bring the pH to approximately 8.5. Samples were incubated for 1-h at 37 °C with 600 RPM shaking, followed by removal of the supernatant, rinsing again with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 50% acetonitrile, and drying again with acetonitrile. A working stock of Asp-N protease was prepared in water 25 ng/µL. After removing acetonitrile, 30 µL (750 ng) Asp-N protease was added to each tube for absorption by the gel pieces. Following absorption, 200 µL 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added to each tube and samples were incubated overnight at 37 °C with 600 RPM shaking. Following incubation, the digest supernatant was removed and added to fresh tubes. Residual peptides were extracted from the gel pieces by 45 mins bath sonication with 150 µL extraction buffer (3% formic acid in 50% aqueous acetonitrile). The supernatants from this extraction were recombined with the corresponding digest supernatants, and the samples were dried under N

2 gas and prepared for LC-MS analysis as previously described [

15].

4. Discussion

Numerous quantitative studies of protein expression using MS-based methodology have relied on the utilization of stable isotopically labeled standards known as AQUA peptides [

48]. These AQUA peptides offer exceptional precision by compensating for variations in ionization efficiency within the mass spectrometer. However, their accuracy is compromised, particularly when immunoprecipitation (IP) is employed for protein isolation, as they fail to account for losses that occur during the isolation procedure. Moreover, they do not consider inter-sample differences in protein digestion efficiency, as demonstrated in our research on apolipoprotein (Apo)A1 protein in human serum [

49]. The inclusion of an AQUA peptide before protease digestion results in differential loss of the peptide during digestion when compared to the protein-derived peptide [

49], rendering this approach unsuitable. Fortunately, these challenges can be effectively overcome by utilizing Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) protein internal standards, as we have successfully demonstrated for HMGB1 in serum and plasma [

15], as well as in various other scenarios. For instance, SILAC internal standards have proven effective for quantifying oxidized HMGB1 in cell media [

6], amyloid-β proteins in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [

50], apolipoprotein-A1 in serum [

51], human frataxin-M and human frataxin-E proteins in whole blood [

52], and mouse frataxin-M proteins in mouse heart, brain, and liver tissues [

47]. The SILAC protein internal standard method establishes a ratio between the SILAC-labeled protein and the corresponding endogenous protein at the beginning of the isolation procedure. This ratio remains constant throughout the entire process and is employed to calculate the quantity of endogenous protein using a standard curve constructed simultaneously with an authentic protein standard. Additionally, the SILAC protein serves as a carrier to enhance the recovery of low-level tissue proteins that may be lost due to non-selective binding to glassware and plastic surfaces. This effect was convincingly demonstrated in our assay for amyloid-β proteins in CSF [

50], where proteins are nearly entirely lost in the absence of a stable isotope carrier due to binding to surfaces during isolation and analysis.

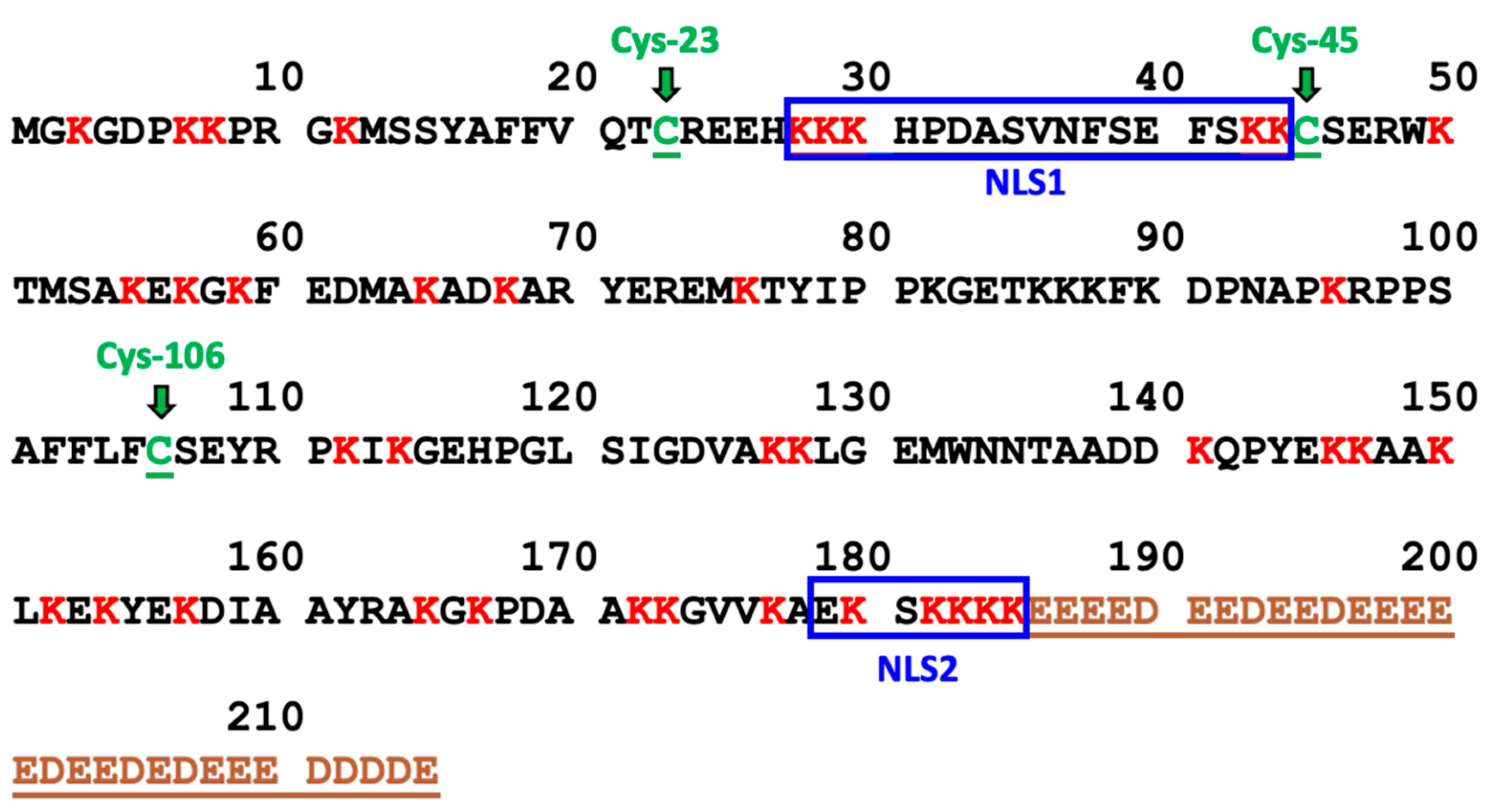

Immunoblotting of cell culture media with and anti-HMGB1 pAb demonstrated that REN and EMMESO mesothelioma cell lines constitutively secrete significant amount of HMGB1. However, A549 NSLC cells do not secrete HMGB1 unless treated with cisplatin. In contrast, HMGB2, despite being found in similar amounts to HMGB1 in the nucleus of A549 cells, is not secreted. Absolute quantification with LC-MS on immunocaptured HMGB1 from A549 cell culture media revealed that cisplatin was very effective at inducing HMGB1 release (

Figure 2B). This suggested that cisplatin has a unique biological activity, which causes HMGB1 secretion. In keeping with such a possibility, neither cisplatin’s stereoisomer transplatin nor the platinum drug analog carboplatin caused significant HMGB1 release, even at much higher doses. Both cisplatin [

53] and carboplatin [

54] form the same 1,2-(GpG) intrastrand crosslinks, suggesting that the slower kinetics of carboplatin’s reactivity with DNA might be sufficient to result in disparate effects on HMGB1 release, or the that activity might even be distinct from their effects on DNA damage. Trypan blue exclusion assays demonstrated that 100 μM carboplatin were less effective than 20 μM and 100 μM cisplatin in attenuating A549 cell proliferation and viability after 24 h, suggesting less impact on DNA replication, presumably through less reactivity with nuclear DNA (

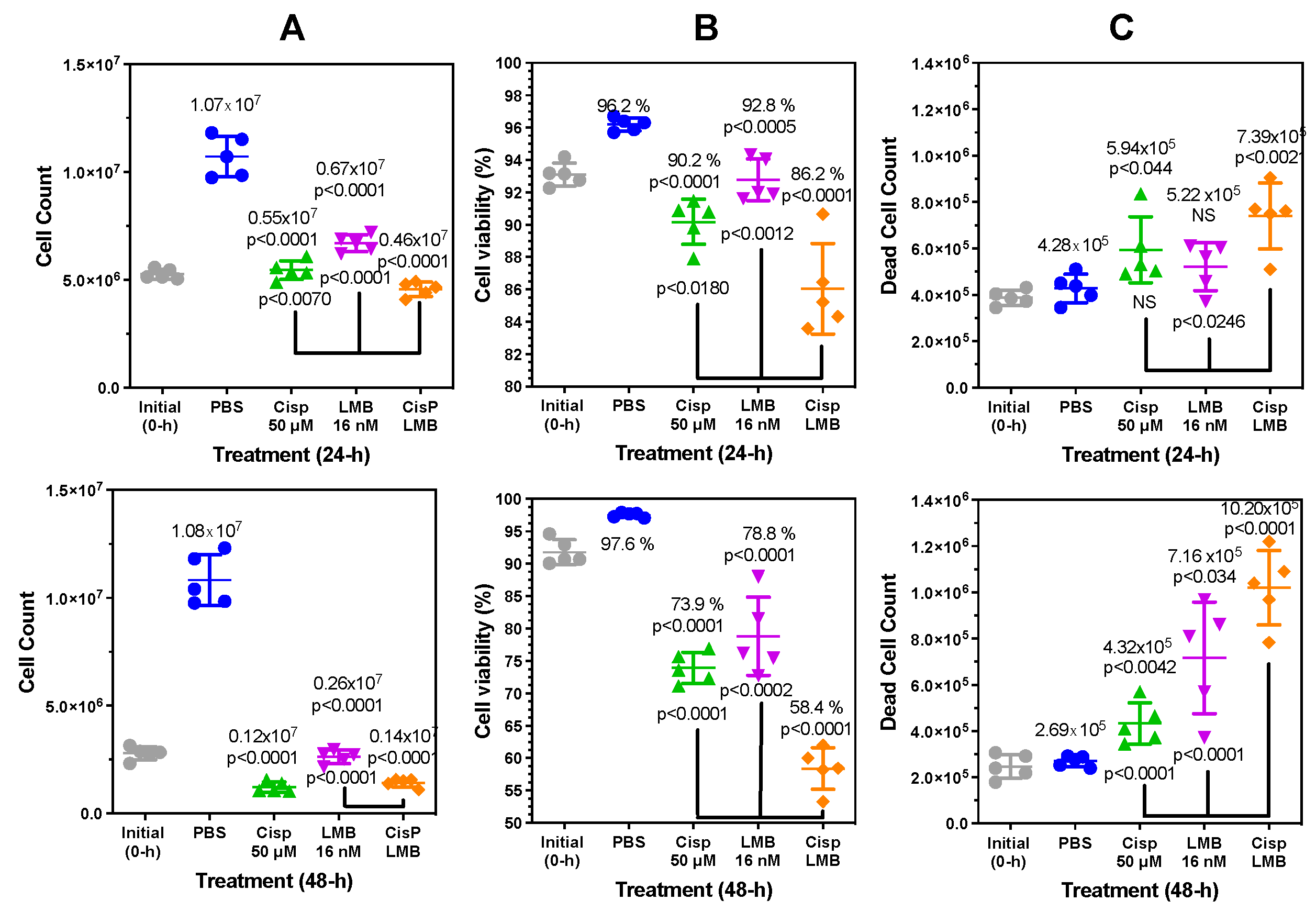

Figure S12). However, there was no difference in cell viability between 20 μM cisplatin and 300 μM carboplatin, which means that it is not simply a difference in the ability of platinum drugs to induce A549 cell death that is responsible for the increase in cisplatin mediated HMGB1 release.

DMSO (

p<0.0014) and cisplatin at 20 μM (p<0.0014) and 100 μM (p<0.0001) induced significantly increased amounts of HMGB1 secretion from A549 cells when compared with PBS controls (

Figure 2B). DMSO is known to cause cellular oxidative stress and DNA oxidation [

43] as well as apoptosis [

44]. Therefore, we reasoned that both DMSO and cisplatin might function similarly by causing passive release of HMGB1 due to loss of nuclear and plasma membrane integrity following apoptosis and secondary necrosis. However, analysis with fluorescence microscopy revealed that DMSO caused robust apoptosis and necrosis (

Figure S11B), whereas low dose cisplatin had very little effect after 24-h at doses up to 100 μM (

Figures S11C and S11D). Trypan blue exclusion assays confirmed this finding, showing that 24-h cisplatin treatment with 50 μM cisplatin primarily induced a significant decrease in cell proliferation (

Figure 8A upper) and viability (

Figure 8B upper) after 24-h compared to PBS. There was a very modest increase in cell death (5.9 ± 1.4 x 10

5 cells;

p<0.044) when compared to PBS (4.3 ± 0.5 x 10

5 cells) at 24-h (

Figure 8C upper). Given that A549 cells showed significant secretion of HMGB1 with cisplatin despite intact nuclear and plasma membranes after 24-h, we reasoned that secretion was through a regulated mechanism rather than a passive release of nuclear proteins. It is noteworthy that there remained a significant decrease in cell proliferation (p<0.0001,

Figure 8A lower) and viability (p<0.0001,

Figure 8B lower) when compared with PBS at 48-h with no additional increase in cell death (

Figure 8C lower).

To confirm that cisplatin treatment specifically induced the secretion of HMGB1, and not all nuclear proteins, we examined the nuclear, cytosolic, and media fractions of A549 cells for HMGB1 and HMGB2. Anti-HMGB1 and anti-HMGB1 immunoblotting showed specificity for HMGB1 and HMGB2 respectively, as demonstrated with recombinant proteins (

Figures S3A and S3B). HMGB1 was detected in nuclear and cytosolic fractions (

Figure S3A), whereas HMGB2 was only detected in the nucleus. (

Figure S3B). Anti-histone 4 and anti-FASN immunoblotting confirmed robust enrichment of the nuclear and cytosolic fractions and showed that there was no leakage of A549 cellular proteins into the cell culture media (

Figure S3C). HMGB1 and HMGB2 are nuclear proteins that are 93 % homologous and 80 % identical [

55]. Surprisingly, we found that only HMGB1 was secreted in significant amounts into the A549 cell culture media after cisplatin treatment. This finding was confirmed by qualitative LC-MS analysis of HMGB1- and HMGB2-specific peptides in subcellular fractions (

Figures S4 to S6). It has been previously reported that HMGB2 can be secreted from myeloid cells [

56] and has been detected in serum of patients with coronary artery in-stent restenosis [

57], which provides further evidence that cisplatin is unique in its ability to selectively induce HMGB1 release in the presence of high levels of HMGB2.

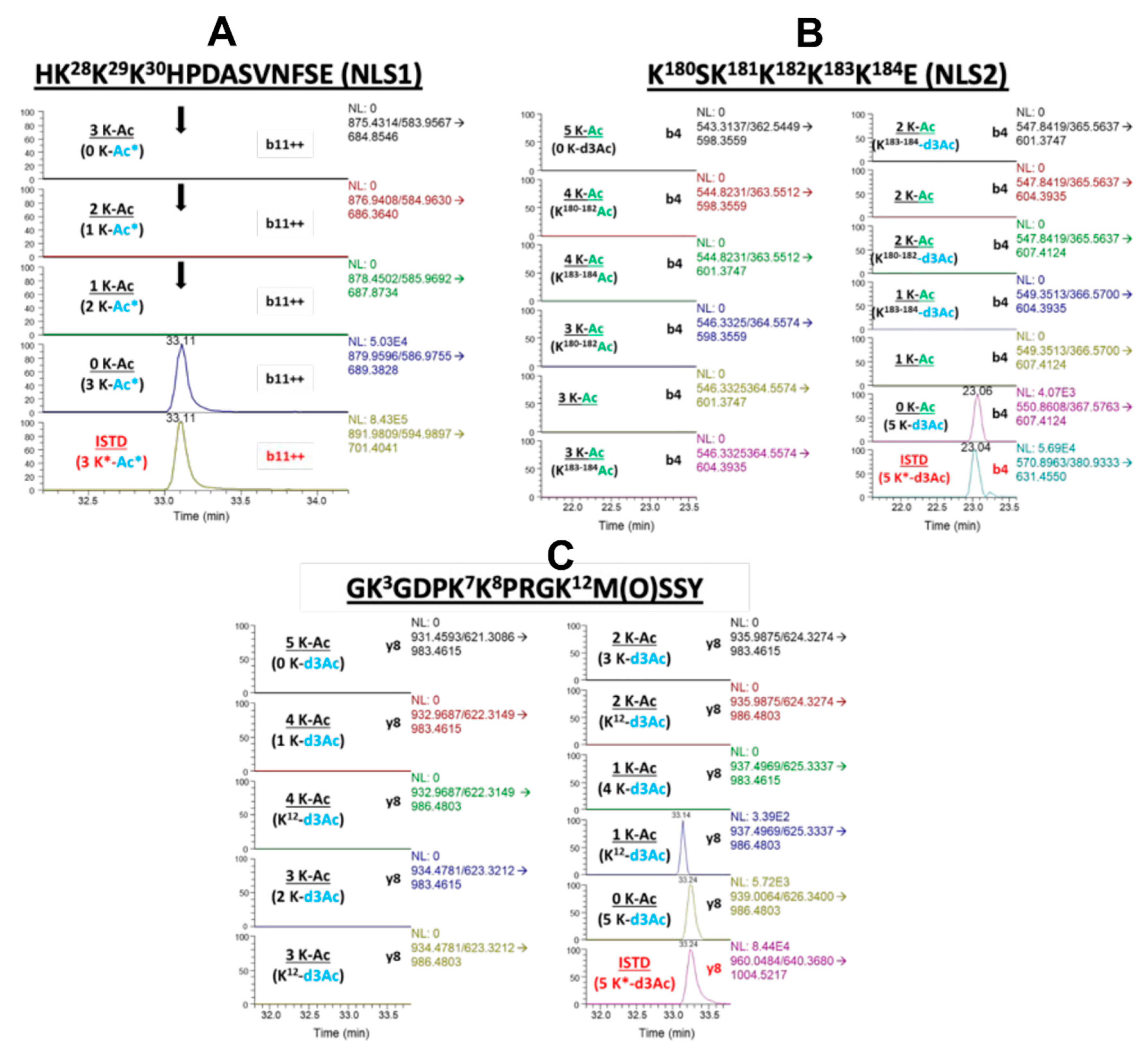

There are several reports that acetylation of HMGB1 at K-3, K-7, or K-12 can modulate its ability to inhibit the repair of cisplatin DNA-adducts [

4,

58,

59,

60]. Unfortunately,

in vitro, and

in vivo studies with cisplatin have been unable to confirm that these PTMs are present on secreted HMGB1. To address this issue by quantifying acetylation at K-3, K-7, and K-12, a SILAC HMGB1 internal standard was added to cell culture media samples collected from A549 cells (

Scheme 1). HMGB1 was isolated by IP of these samples and treated with

D6-acetic anhydride to trideuteroacetylate (C

D3-acetylate) all unacetylated HMGB1 lysine residues. This process converted each of the HMGB1-derived peptides into one molecular form, that only differed in the mass of the acetyl-lysine modification. In a previous study, we showed the IP procedure can isolate HMGB1 containing acetylated lysine residues [

15]. Using this approach, we were unable to detect acetylation on K-3, K-7, or K-12 residues using a highly specific nanoLC-PRM/HRMS method (

Scheme 1). There is also substantial evidence suggesting that HMGB1 NLS1 and NLS2 acetylation is required to facilitate its secretion [

31,

32,

41,

61], although many of the key studies have been retracted or statements of concern issued [

28]. Consequently, it is perhaps not surprising that we were unable to detect any acetylated forms of HMGB1 secreted after treatment of A549 lung cells with cisplatin. Therefore, we investigated whether cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion was regulated by other PTMs.

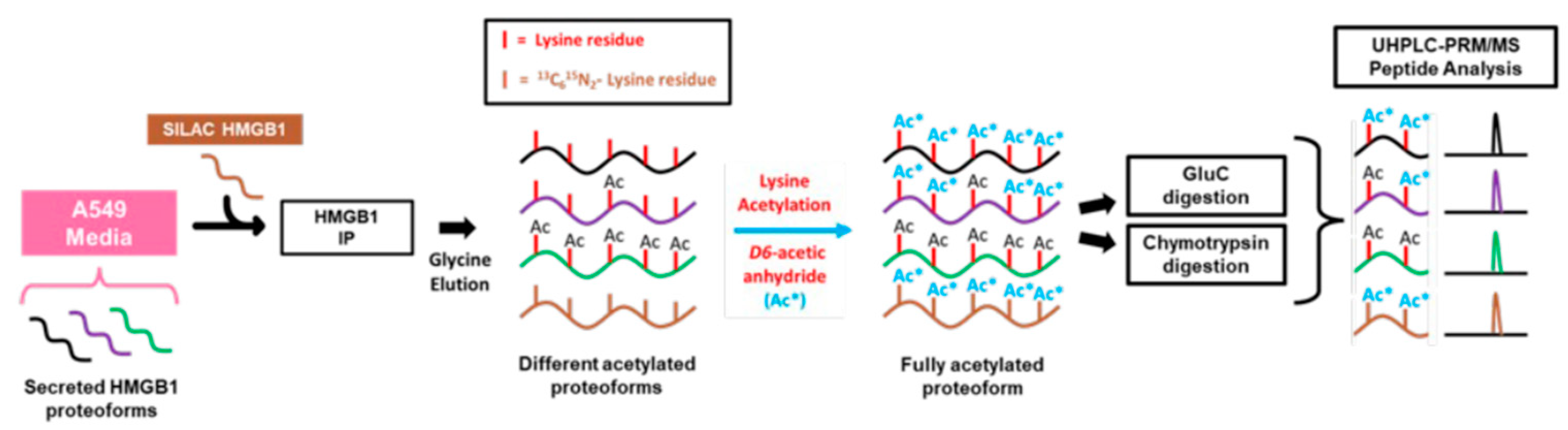

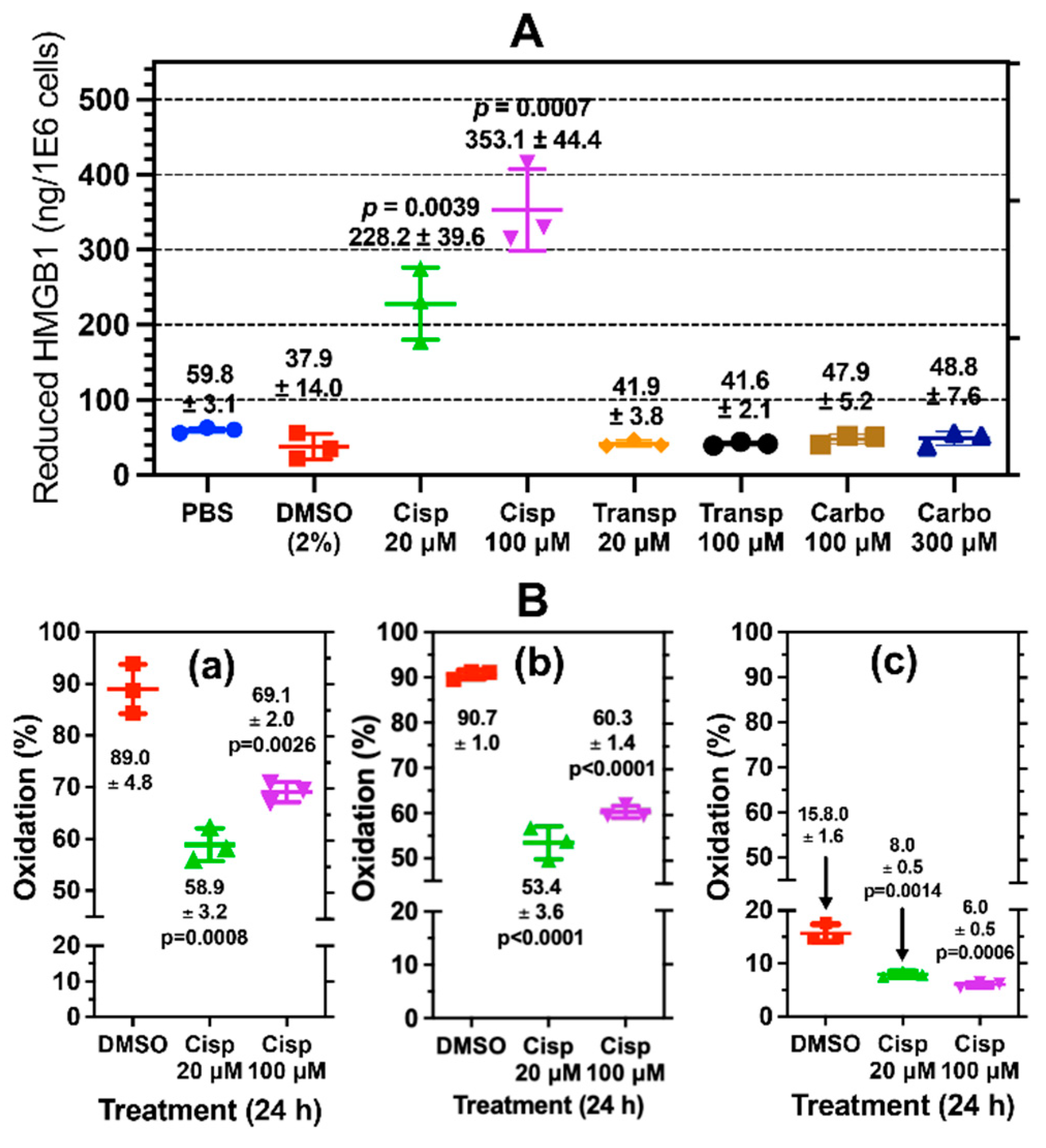

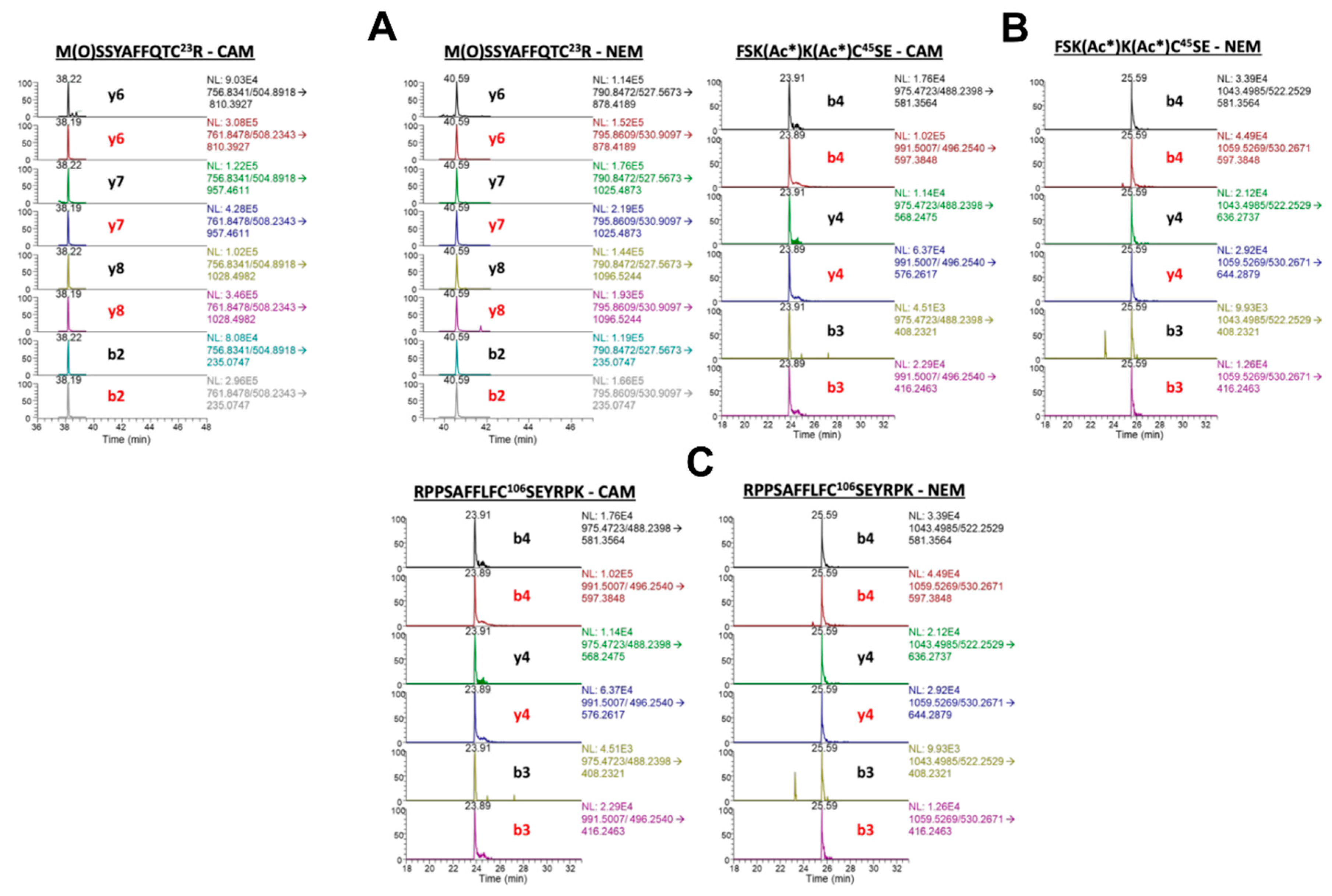

The oxidation state of HMGB1’s three Cys residues has been considered especially important in regulating both HMGB1’s secretion and its extracellular signaling activity. However, there are contradictory reports that relate the redox status of extracellular HMGB1 to its mechanism of secretion. This is because most approaches in interrogating the redox state of HMGB1 lack the necessary quantitative parameters for site-specific analysis to accurately measure labile modifications like disulfide bonds. Therefore, we developed a novel differential alkylation approach using SILAC HMGB1 internal standard to control for any differences in HMGB1 recovery, digestion, or peptide ionization efficiency among differentially alkylated HMGB1 proteoforms. This made it possible to conduct site-specific quantification of HMGB1 Cys-disulfides (

Scheme 2). Although other tested treatments induced the release of some reduced HMGB1 with free Cys-23 and C-45,, cisplatin induced the secretion of significantly more reduced HMGB1. The association of this reduced proteoform of HMGB1 with chemokine activity [

62,

63,

64] indicates that cisplatin could increase immune cell recruitment to tumors during cancer chemotherapy.

We also explored whether other PTMs might be involved in the regulation of cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion by testing the effects of different pharmacological inhibitors of PTM formation and examining immunoblots of the cell culture media. Although ADP-ribosylation by PARP1 has been implicated in the regulation of HMGB1 mobility, including a model of DNA damage-associated subcellular translocation [

65], the PARP1 inhibitor Olaparib [

66] had no effect on cisplatin-mediated HMGB1 secretion (

Figure 6A). Similarly, although HMGB1 phosphorylation by PKCs has been suggested to increase HMGB1 secretion, we found that pan-PKC inhibitors GO-6983 [

67] and Rottlerin [

68] had no effect on cisplatin-mediated HMGB1 secretion from A549 cells (

Figure 6b and

Figure 6C). Furthermore, we were unable to detect any other modifications at lysine, tyrosine, serine, or threonine using LC-HRMS/MS analysis of Asp-N, Glu-C, or chymotryptic peptides.

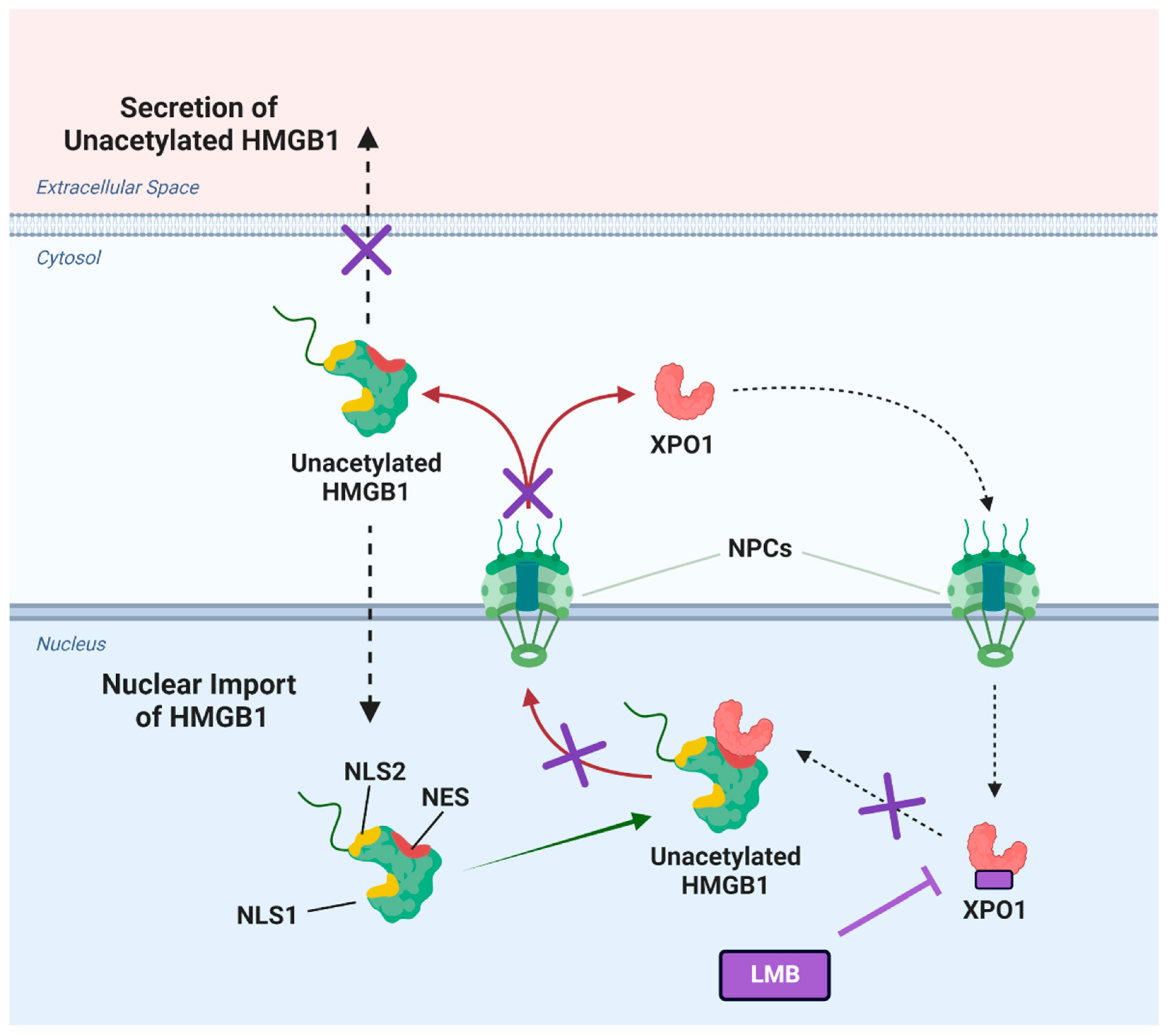

Misinterpretation of much of the original MS data on HMGB1 secretion led to the erroneous concept that acetylation was required for HMGB1 secretion to occur [

69]. Nevertheless, this early study did convincingly show that inhibition of nuclear export with LMB prevented the transport of HMGB1 from the nucleus to the cytosol [

69]. However, this study did not report that LMB also inhibits secretion of the substantial amounts of HMGB1 that are present in the cytosol (

Figure 7B). LMB is known to inhibit the nuclear export of proteins through binding and inhibition of XPO1 (CRM1) (

Figure 9) [

70,

71]. Inhibition of XPO1 might also prevent the nuclear export of pro-secretory proteins and so prevent the secretion of cytosolic proteins [

72]. We reasoned that LMB could inhibit the secretion of HMGB1 by concentrating it in the nucleus and inhibiting secretion of the residual HMGB1 from the cytosol (

Figure 9). LMB caused an increase in cell death (

Figure 8C) and is known to be cytotoxic [

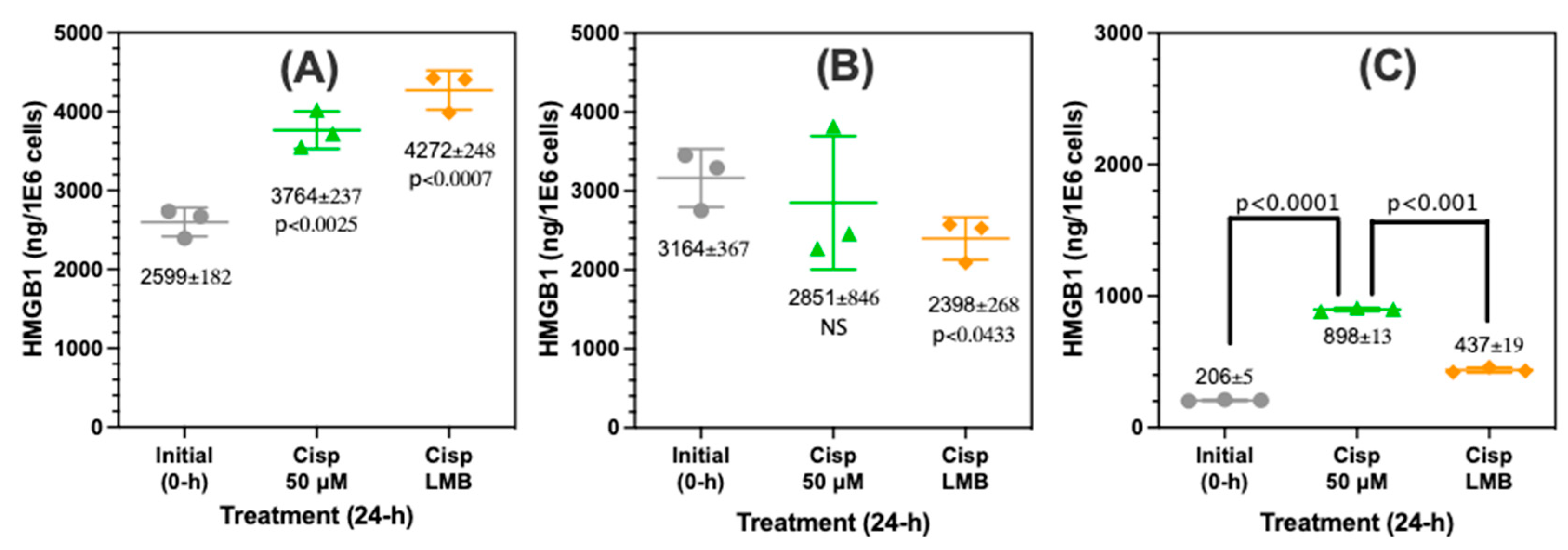

73].

Consequently, there is a narrow concentration range where a decrease in HMGB1 secretion can be observed before it induces necrotic cell death and releases HMGB1. We found that addition of LMB caused a significant inhibition of cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion (

Figure 6D,

Figure 6F and

Figure 7C). We also showed that the XPO1 inhibitor KPT-330 [

74,

75] also caused a significant decrease in HMGB1 secretion (

Figure 6E and

Figure 6G). A combination of cisplatin and LMB resulted in an additive increase in A549 cell death at 24-h and 48-h when compared with LMB alone or cisplatin alone (

Figure 8C). There was a concomitant increase in nuclear HMGB1 with a decrease in cytosolic HMGB1 (

Figure 7B) and inhibition of HMGB1 secretion (

Figure 7C) as would be predicted if nuclear export were inhibited (

Figure 9). HMGB1 binds more tightly to cisplatinated DNA than unmodified DNA, and this binding inhibits the repair of cisplatin derived 1,2-(GpG) DNA intrastrand crosslinks, which in turn interferes with DNA replication and eventually activates apoptosis [

25]. Cisplatin treatment causes increased HMGB1 concentration in the nucleus (

Figure 7A), and cancer cells seem to partially survive treatment with cisplatin by transporting HMGB1 from the nucleus into the cytosol where it is then secreted into the extracellular milieu. Therefore, our data are consistent with the concept that LMB-mediated accumulation of HMGB1 in the nucleus facilitates the known ability of HMGB1 to inhibit of 1,2-(GpG) DNA intrastrand repair [

4,

58,

59,

60] and so potentiates the ability of cisplatin to induce A549 NSCLC viability and cell death (

Figure 7).

Figure 1.

Amino Acid Sequence of HMGB1. The 43 lysine residues are labeled in red and the 3 cysteine residues (Cys-23, Cys-45, and Cys-106) are labeled in green. NLS1 consists of residues 28-44 and NLS2 consists of residues 179-185. The acidic tail (residues 186-215) is labeled in brown.

Figure 1.

Amino Acid Sequence of HMGB1. The 43 lysine residues are labeled in red and the 3 cysteine residues (Cys-23, Cys-45, and Cys-106) are labeled in green. NLS1 consists of residues 28-44 and NLS2 consists of residues 179-185. The acidic tail (residues 186-215) is labeled in brown.

Figure 2.

Cisplatin induces HMGB1 secretion from lung cancer cells. Assays were performed following 24-h incubation A549 cells with cisplatin (Cisp, 20 μM), Cisp (100 μM, transplatin (Transp, 20 μM), Transp (100 μM), carboplatin (Carbop, 100 μM) and Carbop (300 μM). (A) Representative HMGB1 immunoblots of biological replicates (n=3) comparing A549 cell culture media to media from untreated malignant mesothelioma cell lines REN and EMMESO. An anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb against the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1 was used. (B) absolute quantification of secreted HMGB1 by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry. Significant differences compared to PBS were determined using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Error bars show ± SD.

Figure 2.

Cisplatin induces HMGB1 secretion from lung cancer cells. Assays were performed following 24-h incubation A549 cells with cisplatin (Cisp, 20 μM), Cisp (100 μM, transplatin (Transp, 20 μM), Transp (100 μM), carboplatin (Carbop, 100 μM) and Carbop (300 μM). (A) Representative HMGB1 immunoblots of biological replicates (n=3) comparing A549 cell culture media to media from untreated malignant mesothelioma cell lines REN and EMMESO. An anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb against the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1 was used. (B) absolute quantification of secreted HMGB1 by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry. Significant differences compared to PBS were determined using unpaired Student’s t-tests. Error bars show ± SD.

Scheme 1.

Procedure for preparation and analysis of acetylation in secreted HMGB1. A549 cell culture media was collected and spiked with K*Y*- stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) internal standard. HMGB1 proteoforms were isolated by overnight IP and eluted with glycine-HCl before CD3-acetylation with D6-acetic anhydride in ammonium bicarbonate/acetonitrile buffer. Samples were subjected to either Glu-C, chymotrypsin, or Asp-N protease digests, and acetylated peptides were analyzed by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry with acetylation status determined by differences in m/z.

Scheme 1.

Procedure for preparation and analysis of acetylation in secreted HMGB1. A549 cell culture media was collected and spiked with K*Y*- stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) internal standard. HMGB1 proteoforms were isolated by overnight IP and eluted with glycine-HCl before CD3-acetylation with D6-acetic anhydride in ammonium bicarbonate/acetonitrile buffer. Samples were subjected to either Glu-C, chymotrypsin, or Asp-N protease digests, and acetylated peptides were analyzed by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry with acetylation status determined by differences in m/z.

Figure 3.

Cisplatin induced secretion of unacetylated HMGB1. Lysine-containing peptides from cisplatin treated A549 media were analyzed for acetylation by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry (nanoLC-PRM/HRMS). Chromatograms show light (black) and heavy (red) transitions with CD3 or endogenous CH3-acetylation. (A) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for NLS1 peptide HK28K29K30HPDASVNFSE comparing b11 transitions for triply (first panel), doubly (second panel), and singly (third panel) acetylated NLS1 compared to unacetylated NLS1 peptide (fourth panel) and heavy NLS1 peptide (fifth panel). (B) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for NLS2 peptide K180SK181K182K183K184 comparing y8 transitions of different possible acetylation states. (C) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for N-terminal peptide GK3GDPK7K8PRGK12M(O)SSY comparing b4 transitions of different possible acetylation states.

Figure 3.

Cisplatin induced secretion of unacetylated HMGB1. Lysine-containing peptides from cisplatin treated A549 media were analyzed for acetylation by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry (nanoLC-PRM/HRMS). Chromatograms show light (black) and heavy (red) transitions with CD3 or endogenous CH3-acetylation. (A) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for NLS1 peptide HK28K29K30HPDASVNFSE comparing b11 transitions for triply (first panel), doubly (second panel), and singly (third panel) acetylated NLS1 compared to unacetylated NLS1 peptide (fourth panel) and heavy NLS1 peptide (fifth panel). (B) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for NLS2 peptide K180SK181K182K183K184 comparing y8 transitions of different possible acetylation states. (C) NanoLC-PRM/HRMS chromatograms for N-terminal peptide GK3GDPK7K8PRGK12M(O)SSY comparing b4 transitions of different possible acetylation states.

Scheme 2.

Procedure for preparation and redox analysis of secreted HMGB1. A549 cell culture media samples were incubated with iodoacetamide (IAA) to carbamidomethylate free (reduced) Cys residues. tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP)-reduced (SILAC) HMGB1 is added both before and after the reaction to act as an internal standard for both free (reduced) and disulfide (oxidized) HMGB1. HMGB1 is immunoprecipitated, eluted, and reduced with TCEP prior to N-ethylmaleimide derivatization. Tryptic peptides for PRM analysis are prepared by overnight trypsin digestion, whereas Glu-C peptides are prepared by overnight Glu-C digestion following in-solution CD3-acetylation of the lysine residues with D6-acetic anhydride.

Scheme 2.

Procedure for preparation and redox analysis of secreted HMGB1. A549 cell culture media samples were incubated with iodoacetamide (IAA) to carbamidomethylate free (reduced) Cys residues. tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP)-reduced (SILAC) HMGB1 is added both before and after the reaction to act as an internal standard for both free (reduced) and disulfide (oxidized) HMGB1. HMGB1 is immunoprecipitated, eluted, and reduced with TCEP prior to N-ethylmaleimide derivatization. Tryptic peptides for PRM analysis are prepared by overnight trypsin digestion, whereas Glu-C peptides are prepared by overnight Glu-C digestion following in-solution CD3-acetylation of the lysine residues with D6-acetic anhydride.

Figure 4.

Cisplatin mediated the release of reduced and oxidized HMGB1 from lung cancer cells. (A) absolute quantification of reduced HMGB1 released by A549 cells (n=3) determined by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry (nanoLC-PRM/HRMS) analysis. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used compare cisplatin with PBS. (B) Site-specific cysteine (Cys) oxidation percentages calculated from nanoLC-PRM/HRMS analysis of carbamidomethyl (CAM)- and N-ethyl maleimide (NEM)-modified peptides in HMGB1 secreted from A549 cells (n=3). (a) Cys-23. (b) Cys-45 (c) Cys-106. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used compare cisplatin with DMSO. Error bars show ± SD.

Figure 4.

Cisplatin mediated the release of reduced and oxidized HMGB1 from lung cancer cells. (A) absolute quantification of reduced HMGB1 released by A549 cells (n=3) determined by nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry (nanoLC-PRM/HRMS) analysis. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used compare cisplatin with PBS. (B) Site-specific cysteine (Cys) oxidation percentages calculated from nanoLC-PRM/HRMS analysis of carbamidomethyl (CAM)- and N-ethyl maleimide (NEM)-modified peptides in HMGB1 secreted from A549 cells (n=3). (a) Cys-23. (b) Cys-45 (c) Cys-106. An unpaired Student’s t-test was used compare cisplatin with DMSO. Error bars show ± SD.

Figure 5.

Nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis of Cys-containing peptides from cisplatin treated A549 media. Chromatograms show corresponding light (black) and heavy (red) transitions. Carbamidomethyl (CAM)-modified transitions indicate free (reduced) Cys proteoforms and N-ethyl maleimide (NEM)-modified transitions indicate disulfide (oxidized) Cys proteoforms. (A) tryptic peptide M(O)SSYAFFQTC23R with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right). (B) Glu-C peptide FSK(Ac*)K(Ac*)C45SE with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right). (C) tryptic peptide RPPSAFFLFC106SEYRPK with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right).

Figure 5.

Nano liquid chromatography parallel reaction monitoring/high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis of Cys-containing peptides from cisplatin treated A549 media. Chromatograms show corresponding light (black) and heavy (red) transitions. Carbamidomethyl (CAM)-modified transitions indicate free (reduced) Cys proteoforms and N-ethyl maleimide (NEM)-modified transitions indicate disulfide (oxidized) Cys proteoforms. (A) tryptic peptide M(O)SSYAFFQTC23R with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right). (B) Glu-C peptide FSK(Ac*)K(Ac*)C45SE with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right). (C) tryptic peptide RPPSAFFLFC106SEYRPK with CAM-modified transitions (left) and NEM-modified transitions (right).

Figure 6.

Cisplatin mediated high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) secretion is regulated by nuclear exportin 1 (XPO1). Representative anti-HMGB1 immunoblots from biological replicates (n=3) of A549 cell culture media using anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb against the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1. (A) Olaparib (50 µM) (B) GO-6983 (120 nM), and (C) Rottlerin (100 µM) treatments showed no effect on cisplatin (50 µM) mediated HMGB1 secretion from A549 cells. Conversely, XPO1 (chromosomal maintenance 1; CRM1) inhibitors (E) leptomycin B (LMB) (4.5 nM) and (E) KPT-330 (75 nM) significantly attenuated cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion. Normalized immunoblot quantification of HMGB1 in A549 cell culture media comparing effects of XPO1 inhibitors on cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion. (F) LMB (4.5 nM). (G) KPT-330 (75 nM). Significant differences were determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test). Error bars show ± SD.

Figure 6.

Cisplatin mediated high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) secretion is regulated by nuclear exportin 1 (XPO1). Representative anti-HMGB1 immunoblots from biological replicates (n=3) of A549 cell culture media using anti-HMGB1 rabbit pAb against the C-terminal acidic tail of HMGB1. (A) Olaparib (50 µM) (B) GO-6983 (120 nM), and (C) Rottlerin (100 µM) treatments showed no effect on cisplatin (50 µM) mediated HMGB1 secretion from A549 cells. Conversely, XPO1 (chromosomal maintenance 1; CRM1) inhibitors (E) leptomycin B (LMB) (4.5 nM) and (E) KPT-330 (75 nM) significantly attenuated cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion. Normalized immunoblot quantification of HMGB1 in A549 cell culture media comparing effects of XPO1 inhibitors on cisplatin mediated HMGB1 secretion. (F) LMB (4.5 nM). (G) KPT-330 (75 nM). Significant differences were determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test). Error bars show ± SD.

Figure 7.

Increased cisplatin mediated nuclear HMGB1 accumulation and decreased secretion after inhibition of nuclear transporter 1 (XPO1). HMGB1 levels were quantified in A549 cells by nano liquid chromatography-parallel reaction monitoring/high resolution/mass spectrometry in A549 subcellular fractions and A549 cell media after treatment with 50 μM cisplatin and a combination of 50 μM cisplatin with 4.5 nM leptomycin B (LMB). (A). Nuclear fraction. (B) Cytosolic fraction. (C) Cell media. Values are mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using an unpaired student’s t-test.

Figure 7.

Increased cisplatin mediated nuclear HMGB1 accumulation and decreased secretion after inhibition of nuclear transporter 1 (XPO1). HMGB1 levels were quantified in A549 cells by nano liquid chromatography-parallel reaction monitoring/high resolution/mass spectrometry in A549 subcellular fractions and A549 cell media after treatment with 50 μM cisplatin and a combination of 50 μM cisplatin with 4.5 nM leptomycin B (LMB). (A). Nuclear fraction. (B) Cytosolic fraction. (C) Cell media. Values are mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was conducted using an unpaired student’s t-test.

Figure 8.

Cisplatin and leptomycin B (LMB) synergistically attenuate A549 cell growth and increase A549 cell death. Trypan Blue exclusion assay on biological replicates (n =5) after cisplatin (50 μM), LMB (16 nM) and a combination of cisplatin (50 μM) and LMB (16 nM) treatment after 24-h. (A) Cell count after 24-h (upper) and 48-h (lower). (B) Cell viability (%) after 24-h and 48-h. (C) Dead cell count after 24-h and 48-h.

Figure 8.

Cisplatin and leptomycin B (LMB) synergistically attenuate A549 cell growth and increase A549 cell death. Trypan Blue exclusion assay on biological replicates (n =5) after cisplatin (50 μM), LMB (16 nM) and a combination of cisplatin (50 μM) and LMB (16 nM) treatment after 24-h. (A) Cell count after 24-h (upper) and 48-h (lower). (B) Cell viability (%) after 24-h and 48-h. (C) Dead cell count after 24-h and 48-h.

Figure 9.

Cisplatin mediated high mobility group box (HMGB1) secretion is regulated by nuclear exportin 1 (XPO1). HMGB1 contains two reported nuclear localization sequences (NLS1 and NLS2) and a potential nuclear export sequence (NES). Upon treatment of lung cancer cells with cisplatin, XPO1 (also known as chromosomal maintenance 1; CRM1) facilitates the nuclear export of unacetylated HMGB1 through the nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) into the cytosol. This translocation allows HMGB1 to be subsequently secreted into the extracellular space. Inhibitors of XPO1 such as leptomycin B (LMB) inhibit the binding of XPO1 to HMGB1, thereby preventing XPO1-regulated secretion of HMGB1 in the presence of cisplatin. Figure created in Biorender.

Figure 9.

Cisplatin mediated high mobility group box (HMGB1) secretion is regulated by nuclear exportin 1 (XPO1). HMGB1 contains two reported nuclear localization sequences (NLS1 and NLS2) and a potential nuclear export sequence (NES). Upon treatment of lung cancer cells with cisplatin, XPO1 (also known as chromosomal maintenance 1; CRM1) facilitates the nuclear export of unacetylated HMGB1 through the nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) into the cytosol. This translocation allows HMGB1 to be subsequently secreted into the extracellular space. Inhibitors of XPO1 such as leptomycin B (LMB) inhibit the binding of XPO1 to HMGB1, thereby preventing XPO1-regulated secretion of HMGB1 in the presence of cisplatin. Figure created in Biorender.