Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. CSR Requirements in the Supply Chain

2.2. CSR Standards Framework

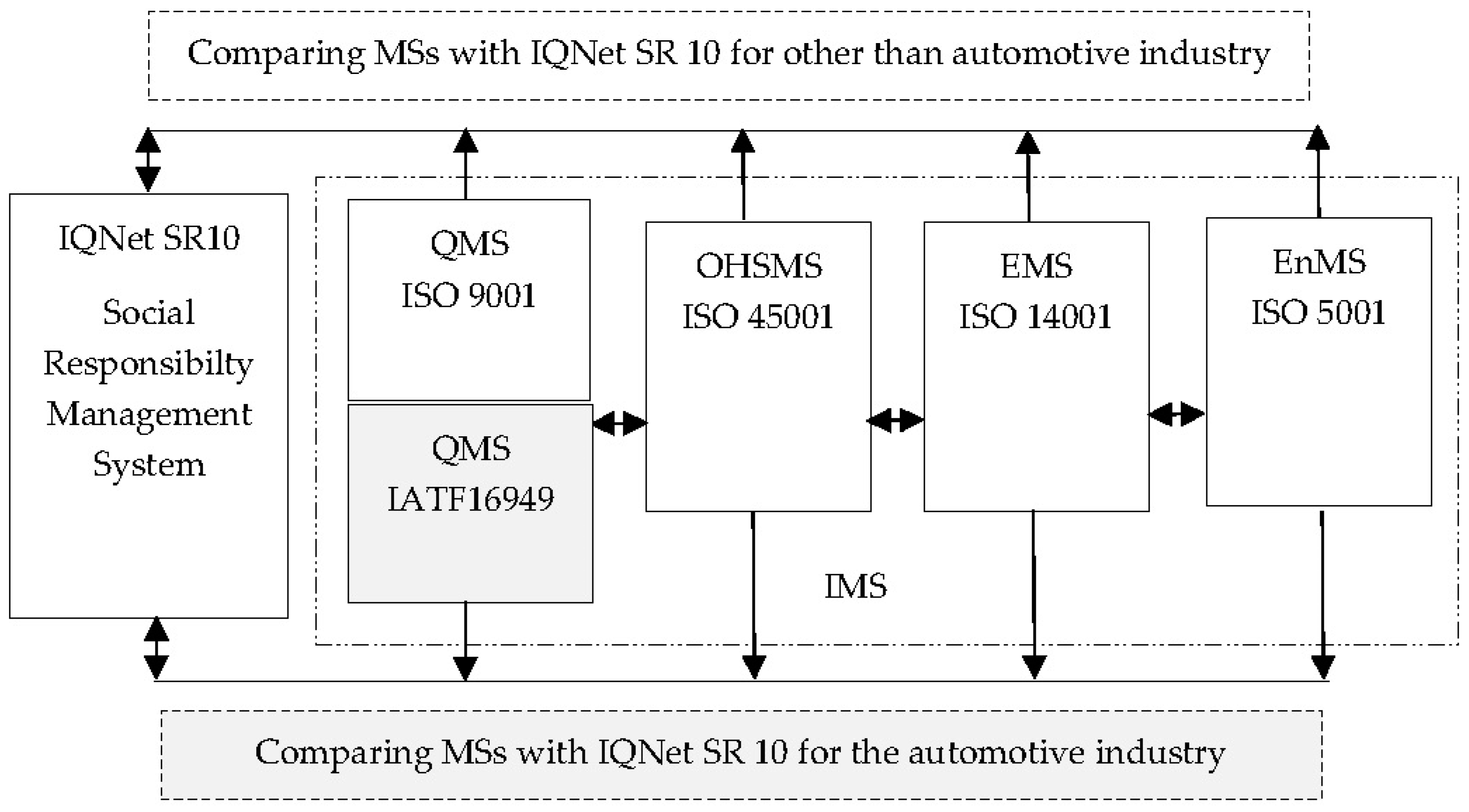

2.3. Analysis of CSR Requirements across Multiple Management Systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Framework of the SRIM Model

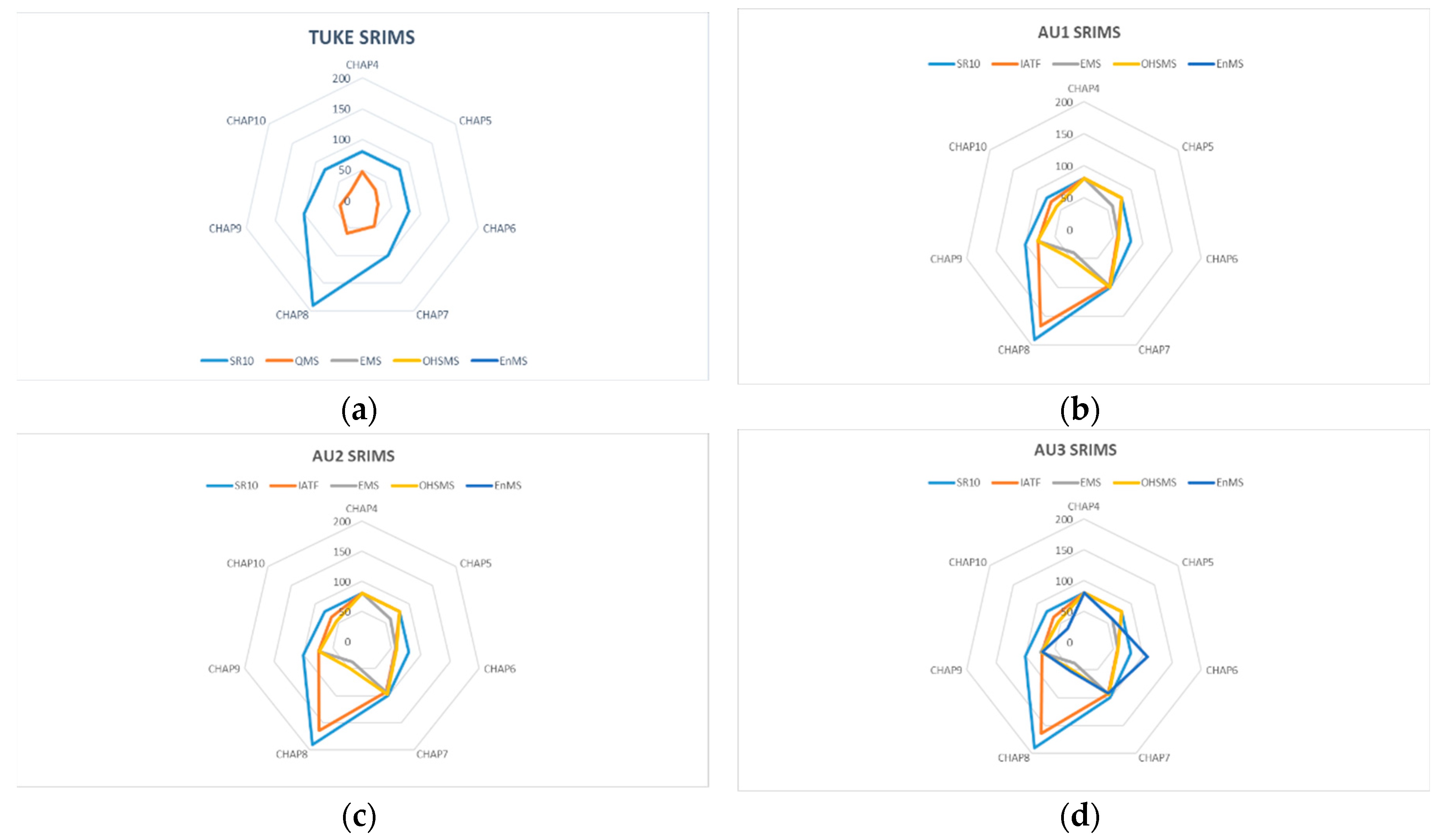

- A research organization (TU), focused on the development of electronic systems, which has an ISO 9001 quality management system in place, but other management systems are not applied, even though it must comply with other requirements of its customers in its activities.

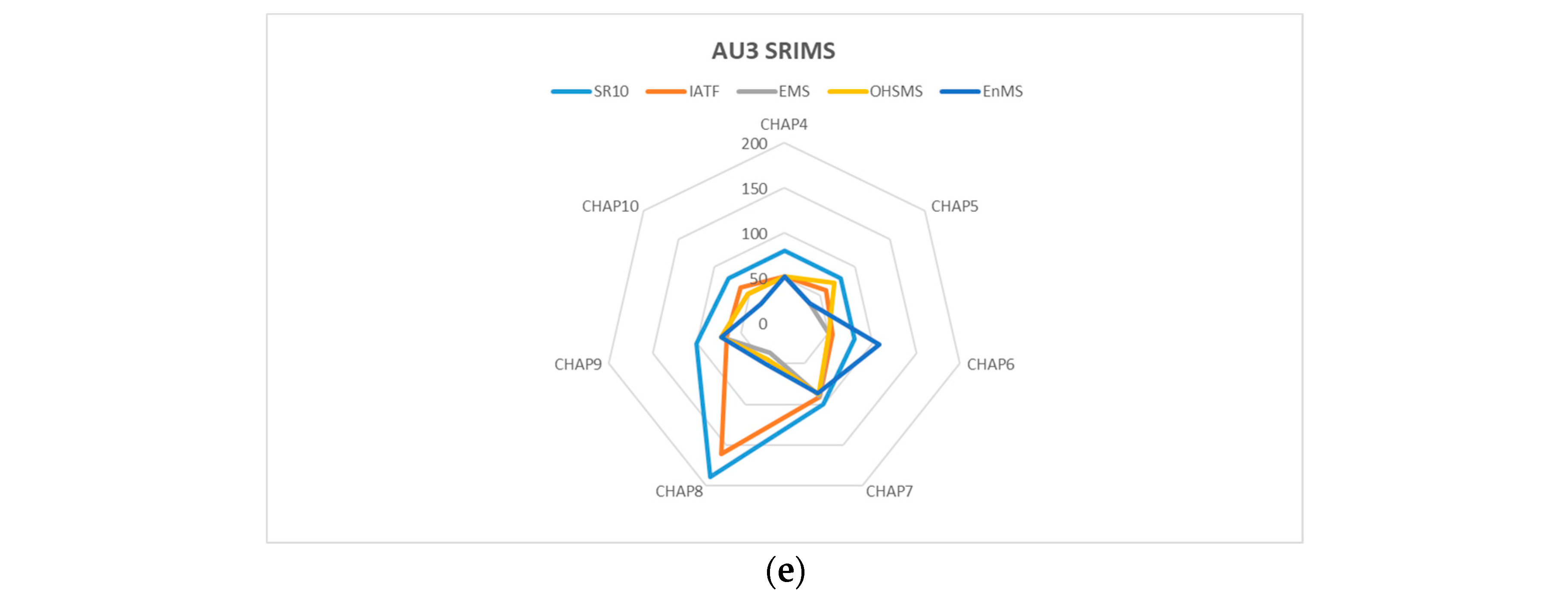

- Three organizations that are suppliers to the automotive industry. Two of them, AU1 and AU2, did not have an energy management system in place, but had a system in place for CSR according to IQNet SR10. Only AU3 has an energy management system in place. It also has CSR requirements in its policy but does not have one in place according to IQNet SR10.

- The last respondent for model verification was a metallurgical company, referred to as OC, which also has an energy management system in place, but a CSR policy, not compliant with IQNet SR10.

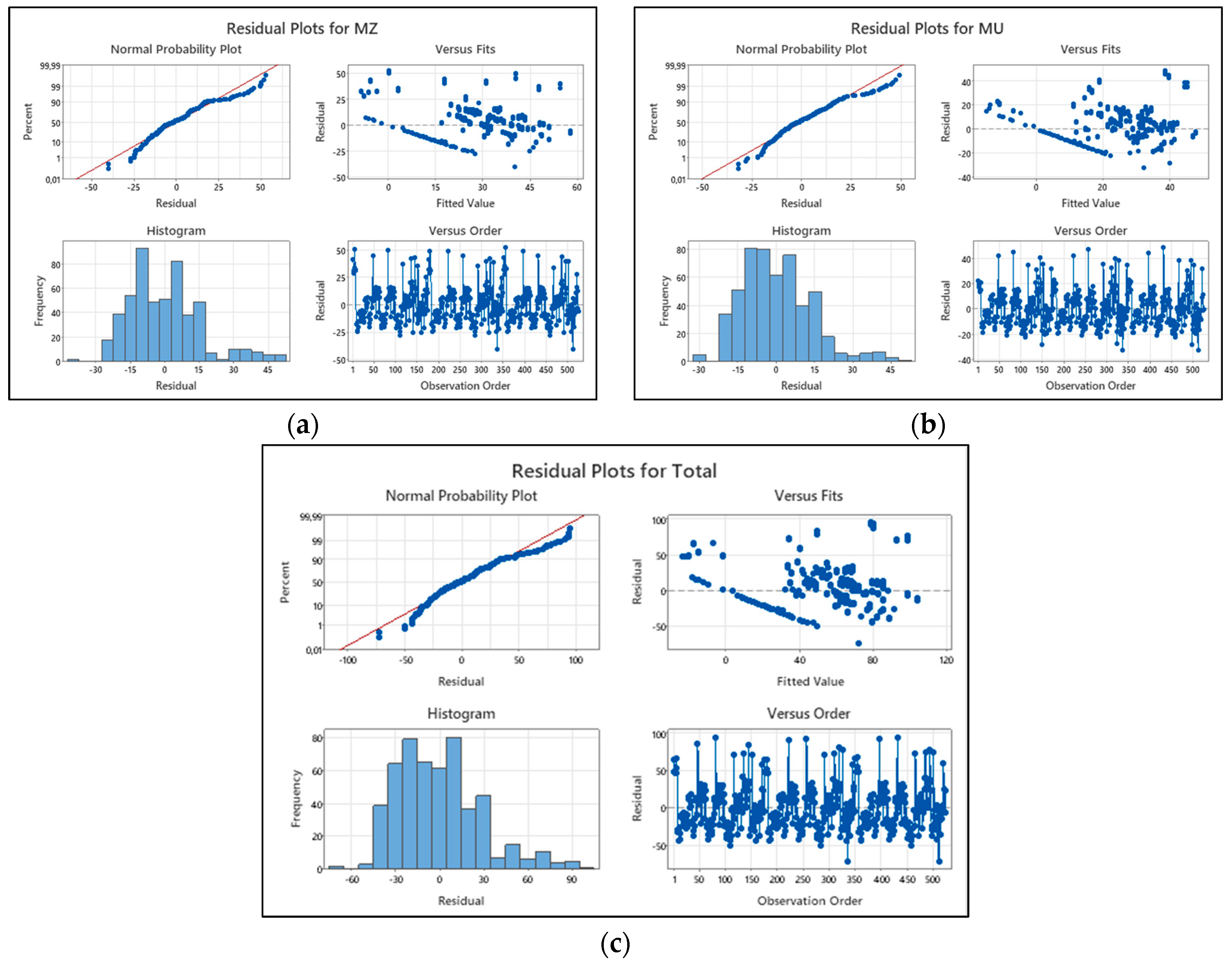

3.2. Evaluation by SRIMS Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, W.; Ahmad, J. Incorporating stakeholder approach in corporate social responsibility (CSR): A case study at multinational corporations (MNCs) in Penang. Social Responsibility Journal 2010, 6, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, D.; Hansen, E. G.; Schaltegger, S. Strategies in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: An Empirical Investigation of Large German Companies 2012. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Forthcoming, Avaliable at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2046934. 2046. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa, P.J.; Przychodzen, W. Social sustainability in supply chains: a review. Social Responsibility Journal 2020, 16, 1125–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, N, M. ; Sinha, S.; Raj, A.; Panda, S.; Merigó, J.M. Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B. Corporate social responsibility and supply chain management: Framing and pushing forward the debate. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 273, 122981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Du, J.; Shahzad, F.; Wattoo, M.U. Environment Sustainability Is a Corporate Social Responsibility: Measuring the Nexus between Sustainable Supply Chain Management, Big Data Analytics Capabilities, and Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.; Skjoett-Larsen, T. Corporate social responsibility in global supply chains. Supply Chain Management 14, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Busse, C.; Bode, C.; Henke, M. Sustainability-Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management. Bus. Strat. Env. 2014, 23, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A.; Gazda, A. A New QFD-CE Method for Considering the Concept of Sustainable Development and Circular Economy. Energies 2023, 16, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pacific Management Review 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamardi, A.A.; Mahdiraji, H.A.; Masoumi, S.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. Developing sustainable competitive advantages from the lens of resource-based view: evidence from IT sector of an emerging economy. Journal of Strategic Marketing 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, O.R.; Almsafir, M.K. The Role of Strategic Leadership in Building Sustainable Competitive Advantage in the Academic Environment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014, 129. International Conference on Innovation, Management and Technology Research, Malaysia, 22–23 September 2013, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, T. The ISO 26000 guidance on social responsibility international standard: what are the business governance implications? Corporate Governance 2013, 13, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R. , Zyphur, M.J. & Schminke, M. When does Ethical Code Enforcement Matter in the Inter-Organizational Context? The Moderating Role of Switching Costs. J Bus Ethics 2011, 104, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Eusanio, M.; Tragnone, B.M.; Petti, L. From Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000) to Social Organisational Life Cycle Assessment (SO-LCA): An Evaluation of the Working Conditions of an Italian Wine-Producing Supply Chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, M.; Santarcangelo, V.; Donvito, V.; Schiavone, O.; Massa, E. Big data for corporate social responsibility: blockchain use in Gioia del Colle DOP. Qual Quant. 2021, 55, 1945–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, C.; Sarkis, J. Determining and applying sustainable supplier key performance indicators. Supply Chain Management 2014, 19, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbufalo, E.; Bastl, M. Multi-principal collaboration and supplier’s compliance with codes-of-conduct. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2018, 29, 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, I.J.; Schwarzkopf, J.; Müller, M. Exploring Supplier Sustainability Audit Standards: Potential for and Barriers to Standardization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castka, P.; Balzarova, M.A. ISO 26000 and supply chains—On the diffusion of the social responsibility standard. International journal of production economics 2008, 111, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, K.; Farzipoor Saen, R. Incorporating dynamic concept into gradual efficiency: Improving suppliers in sustainable supplier development. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 202, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; Spekman, R.E.; Kamauff, J.W.; Werhane, P. Corporate Social Responsibility in Global Supply Chains: A Procedural Justice Perspective. Long Range Planning 2007, 40, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formentini, M.; Taticchi, P. Corporate sustainability approaches and governance mechanisms in sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 112, s–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Liu, Z.; Cruz, J.; Wang, J. Social and Environmental Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis of Supply Chain Profitability and the Recession. Operations and Supply Chain Management 2020, 13, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.; Baden, D.; Harwood, I.A. Insights into Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in Supply Chains: A Multiple Case Study of SMEs in the UK. Operations and Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2009, 2, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sütőová, A.; Kóča, F. Corporate Social Responsibility Standards: Is it Possible to Meet Diverse Customer Requirements? Management Systems in Production Engineering 2022, 30, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, D.; Harwood, I. A.; &, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Woodward, D. G. The effects of procurement policies on ‘downstream’ corporate social responsibility activity: Content-analytic insights into the views and actions of SME owner-managers. International Small Business Journal 2011, 29, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronckers, M.; Gruni, G. Retooling the Sustainability Standards in EU Free Trade Agreements. Journal of International Economic Law 2021, 24, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, A.; Sicurelli, D.; Yildirim, A. Promoting sustainable development through trade? EU trade agreements and global value chains. Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 2021, 51, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yasmeen, R.; Li, Y.; Hafeez, M.; Padda, I.U.H. Free Trade Agreements and Environment for Sustainable Development: A Gravity Model Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 Definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2008, 15(1–13). [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Business horizons 2007, 50, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behringer, K.; Szegedi, K. The Role of CSR In Achieving Sustainable Development – Theoretical Approach. European Scientific Journal, ESJ 2016, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Three-Domain Approach. Business Ethics Quarterly 2003, 13, 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- Witek-Hajduk, M.K.; Zaborek, P. Does Business Model Affect CSR Involvement? A Survey of Polish Manufacturing and Service Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R. Sustainability, responsibility and ethics: different concepts for a single path. Social Responsibility Journal 2021, 17, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Seuring, S. Management of Social Issues in Supply Chains: A Literature Review Exploring Social Issues, Actions and Performance Outcomes. J Bus Ethics 2017, 141, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.; Sarkis, J.; Adenso-Díaz, B. Environmental management system certification and its influence on corporate practices: Evidence from the automotive industry. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2008, 28, 1021–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A. Designing an environmental sustainable supply chain through ISO 14001 standard. Management of Environmental Quality 2013, 24, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshni, A.G.; Siti-Nabiha, A.K.; Jalaludin, D.; Abdalla, Y.A. Barriers to and enablers of sustainability integration in the performance management systems of an oil and gas company. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 136, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Pawar, K.S.; Bhardwaj, S. Improving supply chain social responsibility through supplier development. Production Planning & Control 2017, 28, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruxue, S.; Pingtao, Y.; Weiwei, L. ; Wang, L Sustainability self-determination evaluation based on the possibility ranking method: A case study of cities in ethnic minority autonomous areas of China. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 87, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsien, C.; Zi-Yu, K.; Eisner, E.; Sing Ying, Ch.; Ng Kuan Yuan, L.; Dönmez, J.; Mennenga, M.; Herrmann, Ch.; Sze Choong Low, J. Self-Assessment and Improvement Tool for a Sustainability Excellence Framework in Singapore. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöggl, J.-P.; Fritz, M.M.C.; Baumgartner, R.J. Sustainability Assessment in Automotive and Electronics Supply Chains—A Set of Indicators Defined in a Multi-Stakeholder Approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, N.; Prewett, K.; Shavers, C. L. Is your supply chain ready to embrace blockchain? Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 2019, 2019. 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, I.; Müller, M.; Schwarzkopf, J. Dear supplier, how sustainable are you? A multiple-case study analysis of a widespread tool for sustainable supply chain management. Nachhaltigkeits Management Forum 2020, 28, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N.; Ormiston, J. Blockchain as a sustainability-oriented innovation?: Opportunities for and resistance to Blockchain technology as a driver of sustainability in global food supply chains. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 2022. 175, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M. A.; Habib, M. S.; Hussain, A.; Shahbaz, M. A.; Qamar, A.; Masood, T.; Sultan, M.; Mujtaba, M. A.; Imran, S.; Hasan, M.; Akhtar, M. S.; Uzair Ayub, H. M.; Salman, C. A. Blockchain Adoption for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Economic, Environmental, and Social Perspectives. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10, 899632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastig, G.M.; Sodhi, M.S. Blockchain for Supply Chain Traceability: Business Requirements and Critical Success Factors. Production and Operations Management 2020, 2020. 29, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQNet Association. (2015). IQ Net SR10 Social Responsibility Management Systems Requirements. Bern: IQNet Association - The International Certification Network.

- ISO 26000 Guidance on Social Responsibility. Ženeva: ISO. 2010.

- Szczuka, M. Social Dimension of Sustainability in CSR Standards. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 3, 4800–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.C.M.; Schöggl, J.P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Selected sustainability aspects for supply chain data exchange: Towards a supply chain-wide sustainability assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 141, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola, M. D.; Baraibar-Diez, E. Is Corporate Reputation Associated with Quality of CSR Reporting? Evidence from Spain. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2017, 88, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H. Certification and Accreditation: Types and Rules. In: Standards for Management Systems. Management for Professionals. Springer, (2020)Cham. [CrossRef]

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), https://www.responsiblebusiness.org/.

- McGrath, P.; McCarthy, L.; Marshall, D.; Rehme, J. Tools and Technologies of Transparency in Sustainable Global Supply Chains. California Management Review 2021, 2021. 64, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartos, K.E.; Schwarzkopf, J.; Mueller, M.; Hofmann-Stoelting, Ch. Explanatory factors for variation in supplier sustainability performance in the automotive sector – A quantitative analysis. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain 2022, 5, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagyová, A.; Pačaiová, H.; Markulik, Š.; Turisová, R.; Kozel, R.; Džugan, J. Design of a Model for Risk Reduction in Project Management in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Symmetry 2021, 13, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, V.; Paunović, M.; Casadesus, M. Measuring the Impact of ISO 9001 on Employee and Customer Related Company Performance. Quality Innovation Prosperity 2023, 27, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Sá, J.C.; Félix, M.J.; Barreto, L.; Carvalho, F.; Doiro, M.; Zgodavová, K.; Stefanović, M. New Needed Quality Management Skills for Quality Managers 4.0. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletič, D.; Marques de Almeida, N.; Gomišček, B.; Maletič, N. Understanding motives for and barriers to implementing asset management system: an empirical study for engineered physical assets. Production Planning & Control 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawak, S.; Rogala, P.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M. Research trends in quality management in years 2000-2019. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 2020, 12, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacana, A.; Czerwińska, K. A Quality Control Improvement Model That Takes into Account the Sustainability Concept and KPIs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispas, L.; Mironeasa, C.; Silvestri, A. Risk-Based Approach in the Implementation of Integrated Management Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgodavova, K.; Bober, P. An Innovative Approach to the Integrated Management System Development: SIMPRO-IMS Web Based Environment. Quality Innovation Prosperity 2012, 16, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenadál, J. The New EFQM Model: What is Really New and Could Be Considered as a Suitable Tool with Respect to Quality 4.0 Concept? Quality Innovation Prosperity 2020, 24, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, R.A.; Sanghadasa, M.; Priya, S. Optimization of segmented thermoelectric generator using Taguchi and ANOVA techniques. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, D.C.; DeMars, C.E. An Updated Recommendation for Multiple Comparisons. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2019, 2, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, R. ; Pan, Q-K. ; Naderi, B. Iterated Greedy methods for the distributed permutation flowshop scheduling problem. Omega 2019, 83, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trama, R.; Hautier, Ch.A.; Blache, Y. fctSnPM: Factorial ANOVA and post-hoc tests for Statistical nonParametric Mapping in MATLAB. Journal of Open Source Software 2021, 6, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováč, J.; Gregor, I.; Melicherčík, J.; Kuvik, T. Analysis of the Operating Parameters of Wood Transport Vehicles from the Point of View of Operational Reliability. Forests 2023, 14, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malash, G.F.; El-Khaiary, M.I. ; Piecewise Linear Regression: A Statistical Method for the Analysis of Experimental Adsorption Data by the Intraparticle-Diffusion Models. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 163, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Rafiq, M. An Overview of Construction Occupational Accidents in Hong Kong: A Recent Trend and Future Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Daza, M.A.; Guzmán Rincón, A.; Castaño Rico, J.A.; Segovia-García, N.; Montilla Buitrago, H.Y. Multivariate Analysis of Attitudes, Knowledge and Use of ICT in Students Involved in Virtual Research Seedbeds. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukavská, K.; Burda, V.; Lukavský, J.; Slussareff, M.; Gabrhelík, R. School-Based Prevention of Screen-Related Risk Behaviors during the Long-Term Distant Schooling Caused by COVID-19 Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašková, M.; Balážiková, M.; Krajňák, J. Hazards related to activities of fire-rescue department members during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2022, 117, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CSR standards and access to assessments | Basic subject and requirements | Access to auditing | EL | AU | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBA (Responsible Business Alliance) 2020 | RBA Code of Conduct: 1. Staff; 2. Health and Safety; 3. Environment; 4. Ethics; 5. Management systems | RBA VAP, auditable by a third party. | √ | ||

| Electrolux Supplier standards in the workplace 2020 |

Child labour; Workforce; Safety measures; Health and safety; Non-discrimination; Harassment and abuse; Disciplinary and grievance procedures; Working time; Compensation; Freedom of assembly; Environmental compliance; Corruption and business ethics. | Electrolux Workplace Policy and Supplier Workplace Standard . (second and third party audits) | √ | ||

| BSH Supplier Code of Conduct 2021 |

Laws and regulations; Corruption and bribery; Human rights; Labour; Child labour; Harassment; Compensation; Hours of work; Non-discrimination; Health and safety; Freedom of assembly and collective bargaining; Environment; Supply chain. | CSR audit carried out by a third party towards BSH Supplier Code of Conduct. |

√ | ||

| IATF 16949 | CSR policy that, as a minimum, should include: Anti-Bribery Policy, Employee Code of Conduct, and Ethics Escalation Policy. | √ | |||

| SAQ ver 5.0 2021 |

Business Management, Working Conditions and Human Rights, Health and Safety, Business Ethics, Environment, Supplier Management, Responsible Sourcing of Raw Materials. | √ | |||

| BMW Group Supplier Sustainability Policy 2021 |

1. Environmental responsibility; 2. Social responsibility; 3. Public governance; 4. Supply chain responsibility |

SAQ 5.0 / RBA VAP (third party audit) | √ | ||

| FORD Human Rights Code, basic working conditions and social responsibility 2021 |

1. Human rights and working conditions; 2. Community involvement and indigenous peoples; 3. Bribery and corruption; 4. Environment and sustainability, 5. Accountability and implementation |

SAQ 5.0 / RBA VAP(third party audit) | √ | ||

| PSA Group Responsible Purchasing Rules 2020 |

1. Social principles; 2. Environmental protection; 3. Ethical principles; 4. Sustainable procurement | EcoVadis Platform/PSA Group Own methodology ( third party audits) |

√ | ||

| Volkswagen Group Code of Conduct for Business Partners 2020 |

1. Environmental protection; 2. Human and labour rights of employees; 3. Transparent business relations; 4. Fair market conduct; 5. Due diligence to promote a responsible mineral supply chain; 6. Integration of sustainability requirements in the organization and processes. |

SAQ 5.0 / RBA VAP (third party audit) | √ | ||

| FCA Group Sustainability guidelines for suppliers 2020 |

1. Human rights and working conditions; 2. Environment; 3. Business ethics and corruption; 4. Monitoring and corrective action. |

RBA (by third party towards Supplier Code of Conduct) | √ | ||

| ResponsibleSteel 2021 |

1. Company Management; 2.Social, Environment and Governance Management System; 3. Responsible Sourcing of Input Materials; 4. Decommissioning and Closure; 5.Occupational Health and Safety; 6. Labor rights; 7. Human Rights; 8.Stakeholder Engagement and Communication; 9. Local communities; 10. Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas; 11.Noise, Emissions, Efluents and Waste; 12. Water Stewardship; 13. Biodiverzity. |

Third party audit according to ResponsibleSteel standard. | √ | ||

| ThyssenKrupp Supplier Code of Conduct 2020 |

Human and labour rights; Employee health and safety; Environmental protection; Business conduct; Supplier relations; Compliance with the ThyssenKrupp Code of Conduct. |

ThyssenKrupp Supplier Code of Conduct (second or third party audit) |

√ |

| Standard Chapters |

IQNet SR10 | QMS | IATF | EMS | OHSMS | EnMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Context of the organization | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 5 | Leadership | 80 | 60 | 80 | 60 | 80 | 60 |

| 6 | Planning | 80 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 120 |

| 7 | Support | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 8 | Operation | 190 | 150 | 180 | 40 | 60 | 60 |

| 9 | Performance evaluation | 100 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 10 | Improvement | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| 710 | 610 | 660 | 500 | 540 | 580 | ||

| Respondent | IQNet SR10 | QMS | IATF | EMS | OHSMS | EnMS | Area of activity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TU | √ | EL | |||||

| 2 | AU1 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | AU |

| 3 | AU2 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | AU | |

| 4 | AU3 | √ | √ | √ | √ | AU | ||

| 5 | OC | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ST | |

| Factor | Level | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Organization | 5 | AUT1; AUT2; AUT3; OC; TU |

| Standard | 5 | EMS; EnMS; IATF; OHSAS; QMS |

| Chapter | 7 | 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10 |

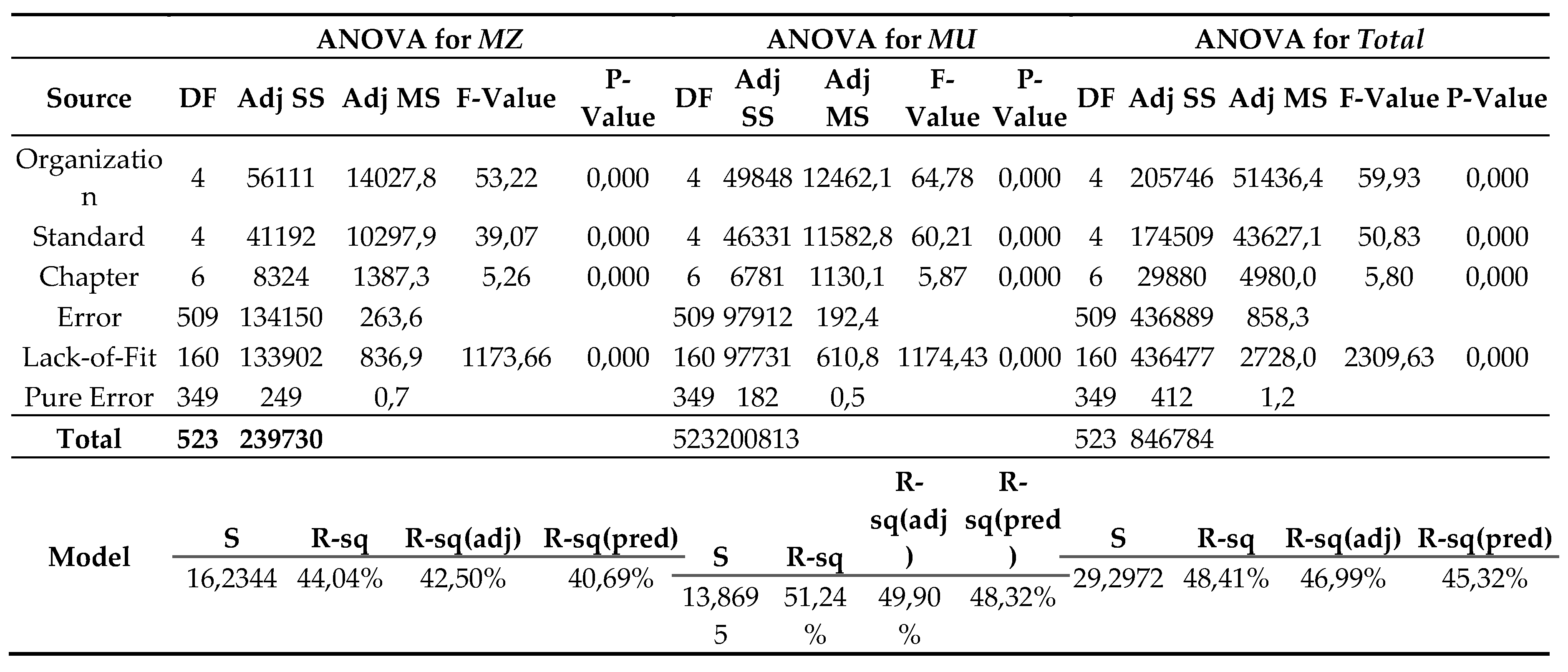

| Test for Equal Variances |

MZ versus Organisation; Standard; Chapter | MU versus Organization; Standard; Chapter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Test Statistic | P-Value | Test Statistic | P-Value |

| Multiple comparisons | — | 0,002 | — | 0,042 |

| Levene | 0,51 | 1,000 | 0,66 | 0,993 |

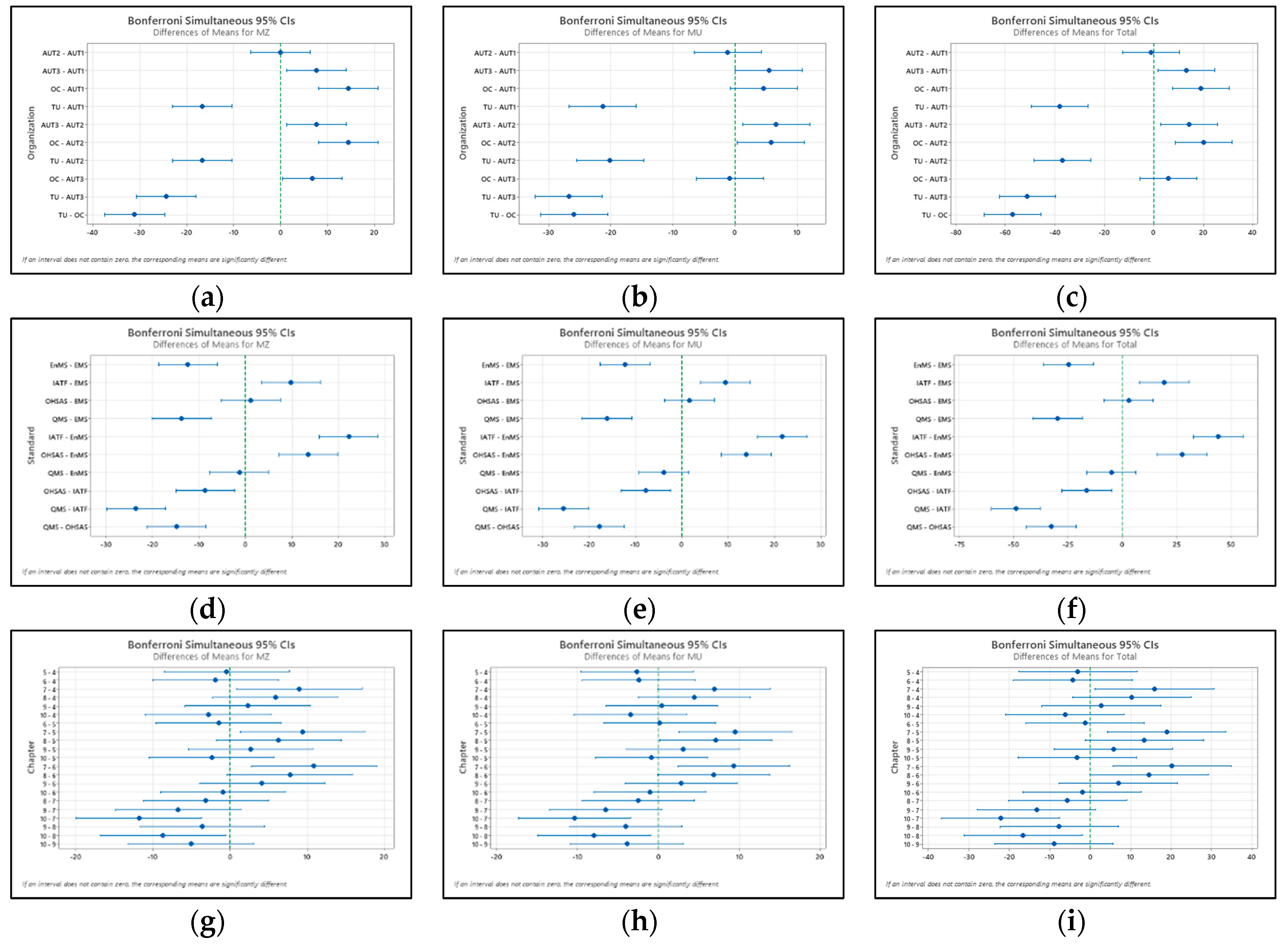

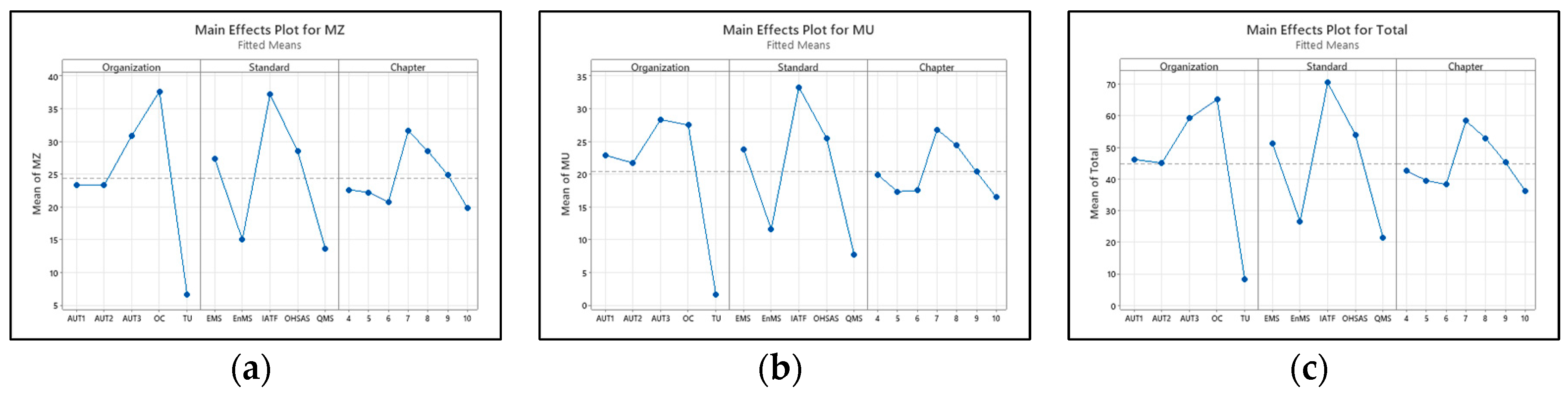

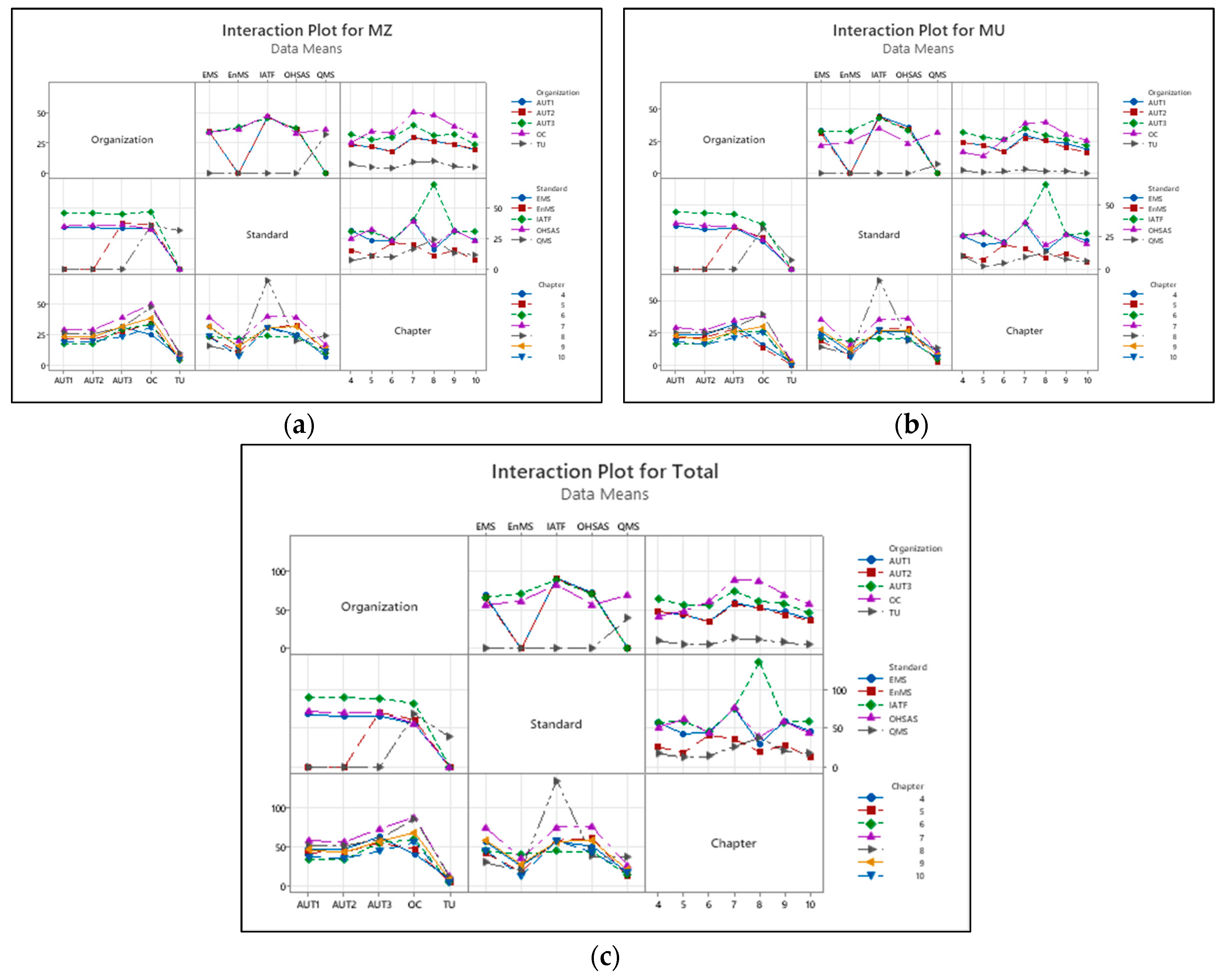

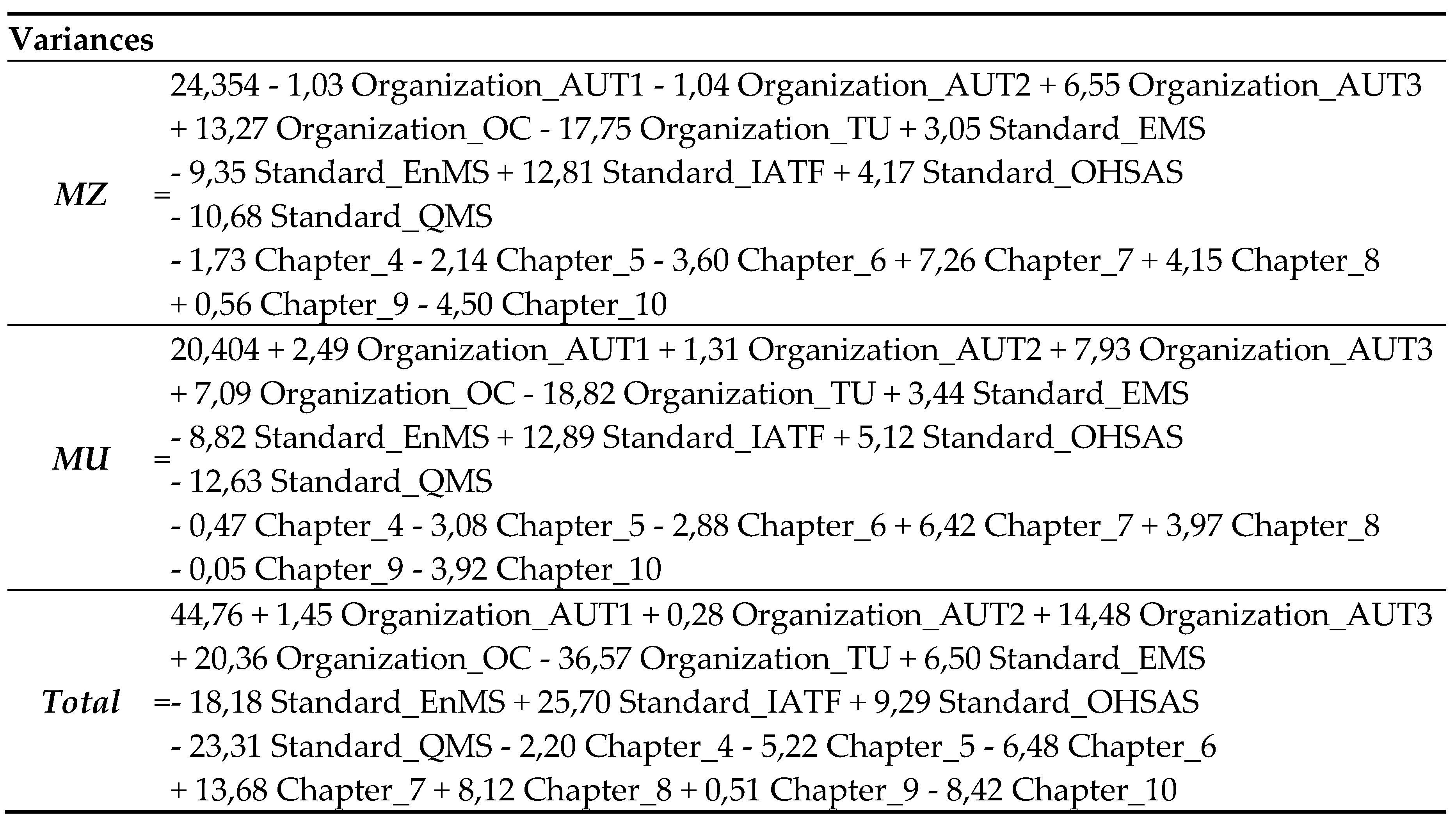

| MZ | MU | Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | N | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | ||||||||

| OC | 104 | 37,6238 | A | 27,4940 | A | B | 65,1178 | A | |||||||

| AUT3 | 105 | 30,9007 | B | 28,3330 | A | 59,2337 | A | ||||||||

| AUT1 | 105 | 23,3214 | C | 22,8904 | B | C | 46,2118 | B | |||||||

| AUT2 | 105 | 23,3170 | C | 21,7191 | C | 45,0362 | B | ||||||||

| TU | 105 | 6,6053 | D | 1,5842 | D | 8,1895 | C | ||||||||

| Standard | N | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | ||||||||

| IATF | 105 | 37,1635 | A | 33,2922 | A | 70,4557 | A | ||||||||

| OHSAS | 104 | 28,5268 | B | 25,5229 | B | 54,0497 | B | ||||||||

| EMS | 105 | 27,4081 | B | 23,8490 | B | 51,2570 | B | ||||||||

| EnMS | 105 | 14,9998 | C | 11,5825 | C | 26,5823 | C | ||||||||

| QMS | 105 | 13,6701 | C | 7,7743 | C | 21,4444 | C | ||||||||

| Chapter | N | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | Mean | Grouping | ||||||||

| 7 | 75 | 31,6125 | A | 26,8287 | A | 58,4412 | A | ||||||||

| 8 | 75 | 28,5033 | A | B | 24,3751 | A | B | 52,8784 | A | B | |||||

| 9 | 75 | 24,9143 | A | B | C | 20,3585 | A | B | C | 45,2728 | A | B | C | ||

| 4 | 74 | 22,6282 | B | C | 19,9340 | A | B | C | 42,5622 | B | C | ||||

| 5 | 75 | 22,2141 | B | C | 17,3245 | C | 39,5387 | B | C | ||||||

| 6 | 75 | 20,7540 | B | C | 17,5241 | B | C | 38,2781 | B | C | |||||

| 10 | 75 | 19,8492 | C | 16,4841 | C | 36,3333 | C | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).