1. Introduction

Innovative solutions, such as energy efficiency in green buildings and consideration of human health in an indoor environment, are critical for a sustainable future [

1,

2]. Green buildings, being more energy-efficient, are associated with reduced energy consumption and improved indoor air quality, a synergy that significantly contributes to human health [

3,

4]. Energy optimization strategies go beyond merely reducing energy costs; they enhance the comfort of inhabitants while lessening environmental harm[

5,

6,

7]. In fact, it is a fundamental and dynamic element in developing green and sustainable buildings. It offers an expedited solution to mitigate the varied impacts, including environmental, economic, social, and so forth, that the construction sector poses. Hence, pursuing high energy efficiency is crucial for achieving building sustainability.

Undeniably, most of us spend a substantial amount of time indoors, as much as 80-90% [

8]. Therefore, optimizing our indoor environments for energy efficiency and air quality is crucial. By exploring and overcoming the hurdles to implementing innovative energy optimization strategies, we can foster healthier, sustainable breathing spaces for the present and future generations[

8,

9].

Chemicals from pesticides, cleaning products, volatile organic compounds from construction materials and furnishings have significant hazards. In addition, particulate matter from tobacco mold and smoke can also have significant effects on human health when indoors [

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Deteriorated air quality, poor illumination, and inadequate thermal comfort are all factors that might negatively affect our health. Designing, analyzing, and managing healthy, comfortable, and energy-efficient buildings falls within the purview of indoor environmental quality professionals. In addition, comfort, delight, productivity, and well-being are all things that should be prioritized in interior spaces [

2,

7,

12].

In recognition of the fact that buildings can have both beneficial and detrimental impacts on their occupants and the surrounding environment, green construction practices have been developed. They hope to lessen the adverse effects while increasing the positive ones. Natural ventilation, renewable energy sources, and a state of art HVAC systems are examples of how green building design and construction may improve IEQ. Incorporation of natural light provides admittance to nature and encourages physical activity are further ways that can design to improve health and well-being. The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that everyone should be able to live in a healthy, safe, and environmentally friendly community. Although it is common knowledge that green buildings save on energy costs, little is known about how green design principles affect occupant health and indoor air quality[

5,

14].

This study explores the role of green buildings in creating healthier settings, emphasizing interior environmental quality and its subsequent impact on human health and comfort. This research also explores several green building energy optimization technologies and their potential advantages to indoor human health. The challenges of incorporating these solutions into prevailing buildings and the prominence of monitoring energy efficiency will be explored.

2. Literature Review

The vital role of green buildings in enhancing indoor environmental quality and human health is indisputable [

15,

16]. Consequently, this study evaluates numerous energy optimization measures for green buildings and investigates their effects on residents' stress levels, mood, productivity, and thermal, acoustic, and visual comfort. Along with social and behavioral variables, it also emphasizes environmental issues, architectural design, operation, and maintenance, as well as other factors that can impact occupant health [

8,

15,

16,

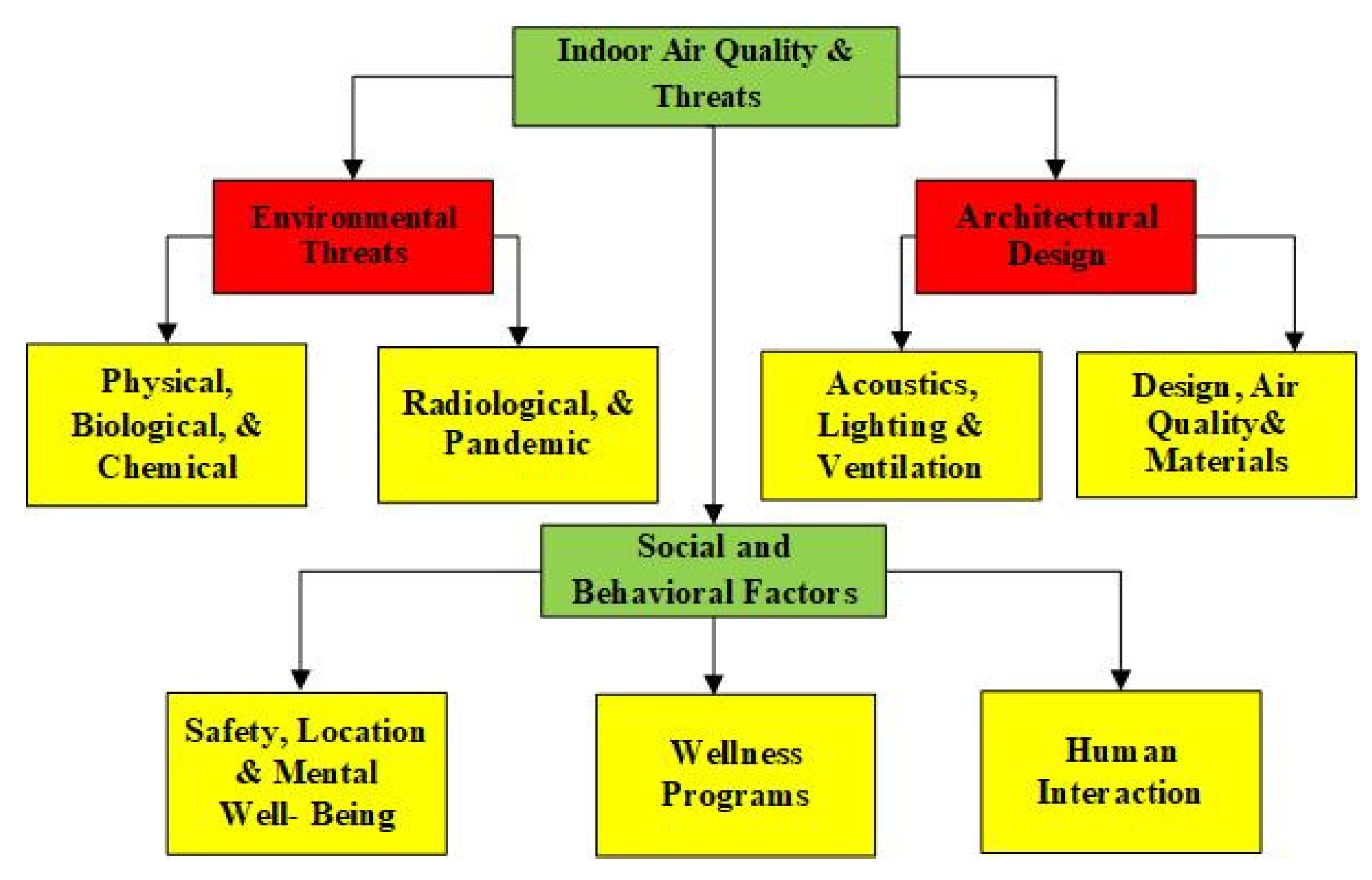

17]. The study discusses various physical and non-physical aspects that influence indoor environmental quality including indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting, acoustics, and ventilation (

Figure 1). This section demonstrates the significant contribution that green buildings with superior interior environmental quality may make to enhancing human health[

18,

19,

20].

Recently, green construction has grown in popularity as a method to reduce energy use efficiently while improving interior environmental quality and human health. Mukhtar et al. (2019) examined the effects of natural ventilation systems, daylighting strategies, and passive design techniques on thermal comfort in green buildings[

21]. The building-related elements highlighted here that may have an impact on tenant health include environmental hazards, architectural design, social and behavioral concerns, and operation and maintenance [

8,

9].

Passive design solutions, which include construction methods and materials that enhance occupant comfort while reducing energy consumption, are also championed as a means to bolster energy efficiency in green buildings [

8,

22,

23]. According to studies, these measures can reduce energy usage by raising it to 50% while also enhancing thermal comfort and lowering the danger of airborne infections. These measures also support to improve acoustics, which leads to better concentration and mental health results for residents [

16,

22,

24,

25]

By utilizing renewable energy technology, green buildings can generate their own heat and electricity, thus enhancing their energy security and independence [

26,

27]. A building's carbon footprint and reliance on nonrenewable energy sources can be significantly reduced by using these sources. Green roofs and walls are emerging in eco-friendly architecture because of their many advantages, such as lowering the urban heat island effect, enhancing thermal insulation, decreasing storm runoff, and improving air quality. Low-volatile organic compound paints, recycled materials, adhesives, and sustainably obtained wood are all examples of sustainable construction materials that can reduce a building's environmental impact and promote its indoor air quality[

26,

27,

28,

29].

2.1. Impacts of Indoor Air Quality

Indoor air quality, abbreviated as IAQ, refers to the air quality within indoor spaces and its influence on human health, comfort, and productivity. This imposes diversified impacts on the environment, society, economics, utilization of technologies strategies, and so forth (

Figure 1) [

6,

29].

2.1.1. Environmental

Energy efficiency measures play a critical role in minimizing environmental impacts. These can be facilitated by utilizing tools for inclusive thermal transfer value calculations, energy modeling, and implementing high-performance building envelopes [

30]. Integrating Building-Integrated Photovoltaic, abbreviated as BIPV facades, efficient light fixtures, and adopting resource-efficient building materials play a pivotal role in achieving this objective[

6,

31].

2.1.2. Economical

Energy efficiency can also play a significant role in attenuating economic impacts. Considerable cost savings can be realized using life cycle assessment methodologies, cost-benefit analyses, and green price premiums. Moreover, the application of multi-energy system designs in buildings, such as solar water heating systems and photovoltaic power generation, contributes to minimizing the total life cycle cost, thereby enhancing the economic feasibility of sustainable buildings[

32].

2.1.3. Social

To mitigate the social impacts, it is essential to innovate new locally available systems that integrate cultural elements into the social dimension of sustainability[

33]. Measuring and comparing indoor environmental quality against benchmark standards, alongside applying novel analytical techniques like option-based conjoint experiments, are essential steps. Models integrating renewable energy, optimized energy consumption, lighting optimization, construction waste management, storm-water quality control, heat-island effect on roofs, and outdoor and indoor air quality are valuable for reducing social impacts[

34].

2.1.4. Energy Effficiency

Energy efficiency and its management have garnered substantial attention in academic and industrial research worldwide. Studies conducted since 2011 span diverse areas, from energy performance, energy management, and energy saving to applying renewable energy sources in sustainable buildings [

7,

9]. Even though governments, research institutions, and universities have commenced numerous studies in this field, no systematic review may have coherently synthesized this knowledge toward achieving energy-efficient sustainable buildings[

35].

2.1.5. Technology Utilization

Technology plays a pivotal role in achieving energy efficacy in buildings. The active and passive design of technologies has been utilized for their probable benefits in energy-saving and reduction in energy demand. Technologies such as double-skin facades have been reviewed for their capacity to improve indoor thermal comfort and enhance energy effectiveness [

6,

35].

2.1.6. Techniques and Strategies

Several techniques have been adopted to enhance energy efficiency. A comprehensive review of comfort management and energy in smart energy buildings involves considerations like occupants' behavior, simulation of tools, control systems, and supply source contemplations. Retrofitting strategies, including passive strategies with assessment approaches (life cycle assessment, social and cost assessment), have been critically reviewed to find optimum retrofitting elucidations [

24]. Figure X discusses environment, social behaviors, and architectural design (ESA).

3. Discussion

Sick building syndrome is characterized by symptoms like eye complications, headaches, sore throats, chest and nasal congestion, difficulty concentrating, dry skin, and dizziness, and is frequently associated with building-related illnesses. These symptoms might not prevent individuals from their daily tasks but often lead to complaints, lost productivity, and dissatisfaction with their work environment. In short, decades of research have shed light on how buildings influence human health and affect occupants’ comfort and productivity. A few key factors include environmental hazards, operation, and maintenance, architectural design, as well as social and behavioral factors (

Figure 2). Environmental hazards encompass biological, physical, radiological, and physical impacts. Operation and maintenance concern with regular repair and maintenance as well as cleaning. Architectural design also can be understated because of design, acoustics, ventilation, lighting, material selection, air quality, and physical activities. Social and behavioral factors also persist due to the importance of safety, wellness location, mental well-being, and human interactions (

Figure 2)[

36,

37].

Environmental hazards, encompassing physical, biological, radiological, chemical, and pandemic-related risks, can significantly impact indoor air quality. Physical hazards include airborne particles from construction activities or natural disasters affecting indoor air quality. Biological threats encompass the presence of mold, bacteria, viruses, and allergens, leading to respiratory issues and infections. Radiological threats like radon gas can seep into buildings, posing long-term health risks like lung cancer[

16,

38,

39]. Chemical hazards arise from volatile organic compounds (V.O.C.s), formaldehyde, lead, asbestos, and other toxic substances commonly found in building materials, cleaning products, and furnishings. Pandemic-related threats, as witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasize the importance of indoor air quality in preventing the spread of infectious diseases. Appropriate ventilation, air filtration, and disinfection measures are crucial in mitigating these environmental threats and maintaining a healthy indoor environment [

25,

40].

Social and behavioral factors play a significant role in indoor air quality, abbreviated as IAQ, as they can influence safety, location choices, wellness programs, mental well-being, and human interaction. Ensuring safety in indoor environments involves promoting awareness of IAQ risks, implementing preventive measures, and establishing protocols for handling emergencies. Building location decisions can consider factors such as proximity to pollution sources, access to green spaces, and availability of clean outdoor air. Wellness programs focusing on IAQ education, regular maintenance, and promoting healthy behaviors contribute to improved IAQ and overall well-being. Good IAQ supports mental well-being by creating comfortable and conducive spaces, reducing stress, and enhancing cognitive function. Furthermore, a healthy indoor environment facilitates positive human interaction, collaboration, and productivity, fostering a sense of community and satisfaction among occupants [

6,

41].

Architectural design is vital for functional, aesthetically pleasing, and healthy indoor environments. Key considerations include acoustics, ventilation, lighting, selection of materials, design, physical activity promotion, and indoor air quality. Acoustic design controls sound for clear communication, while adequate lighting enhances visual comfort. Ventilation ensures fresh air and pollutant removal. Low-emission materials are chosen for sustainability and indoor air quality. The design prioritizes functionality and well-being, promoting physical activity. Indoor air quality is maintained through ventilation and filtration. Incorporating these factors creates healthier, more sustainable spaces [

8,

25,

40].

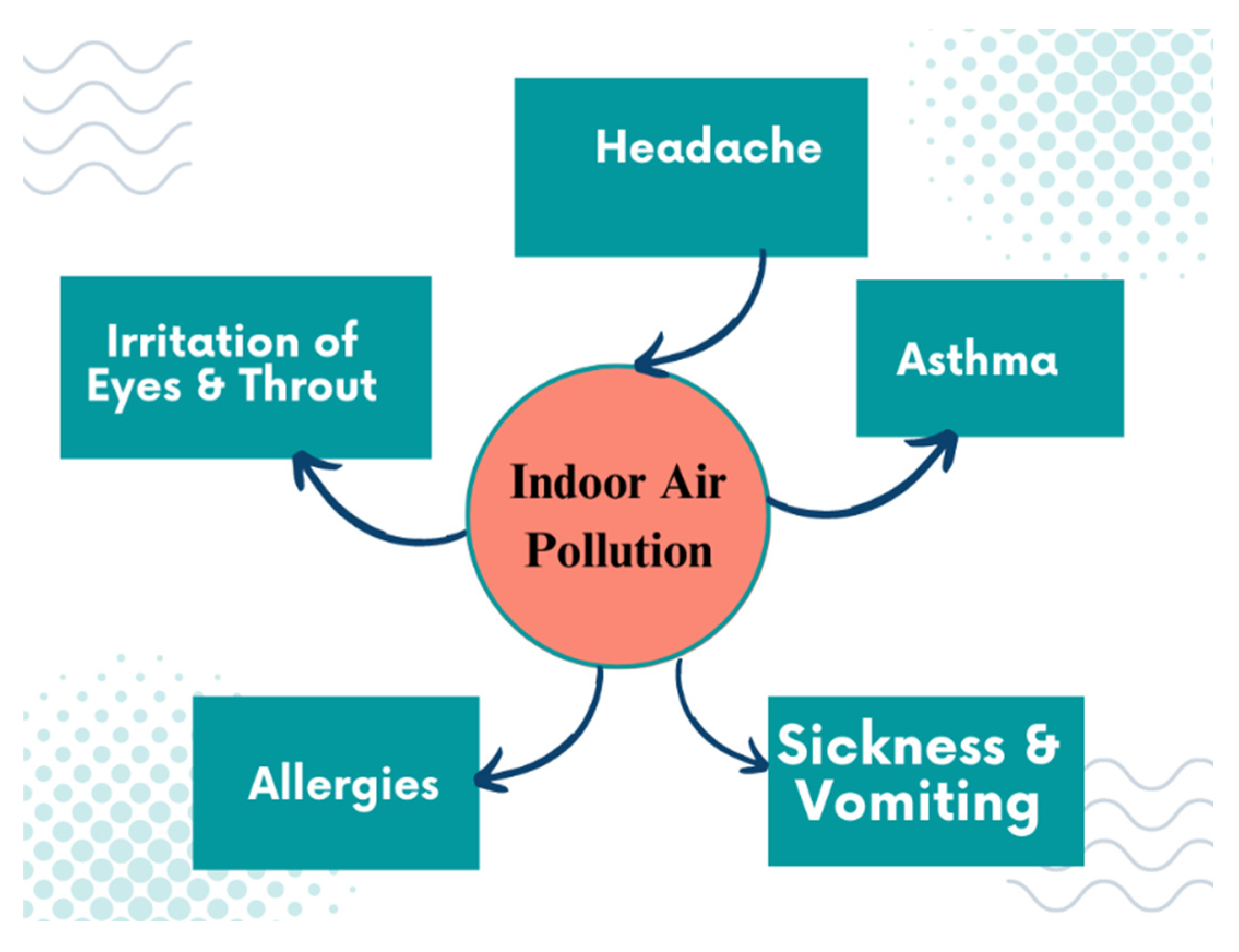

Figure 4.

Key health impacts due to indoor air pollution.

Figure 4.

Key health impacts due to indoor air pollution.

3.1. Features Affecting Indoor Environmental Quality

The issues impacting indoor environmental quality and occupants' comfort can be characterized as physical and non-physical. Physical factors include indoor air quality, thermal comfort, lighting, acoustic conditions, and ventilation. Non-physical factors are challenges to quality to measure employed instruments, including safety and security, space layout, and cleanliness.

The IAQ encompasses pollutants from building materials, human activities, outdoor pollutants infiltrating the building, and its systems and conditions. Poor IAQ can lead to acute and chronic effects, such as irritation, asthma, headaches, and probable carcinogenicity, depending on the type of pollutants and duration of exposure. IAQ is intertwined with other in-building factors impacting the health and comfort of the occupants, such as thermal comfort, lighting, acoustics, and ventilation [

42,

43].

Indoor climate quality remains crucial even in the most preeminent of indoor settings. Noise pollution is detrimental to human health on many levels, and green buildings are specifically built to reduce this problem [

44,

45,

46]. They use insulation to control the temperature and humidity, which has the added benefit of cutting down on outside noise. Using cutting-edge technology to create a carbon-free future is yet another option for achieving green building goals.[

26,

41,

42,

43].

3.2. Green Building: Improving Well-being and Sustainability

Green buildings are crucial in promoting healthier and more sustainable environments for occupants. Studies reported that researchers achieve this by enhancing indoor environmental quality and minimizing negative environmental impacts. Research designates that green buildings contribute to occupant health by encouraging physical activity and plummeting pollutant exposure [

14,

43,

47]. Moreover, this also enhances occupant well-being by increasing access to natural light and educating thermal comfort[

14].

3.3. Strategies for Optimizing the Use of Energy in Green Buildings

Several strategies exist for optimizing green building energy performance. Some examples include passive solar design, high-efficiency lighting and appliances, and the use of renewable energy sources[

21,

30,

48]. Large windows, south-facing facades, and thermal mass are all components of passive solar design that help reduce the necessity for artificial cooling and heating [

44,

49]. Energy-efficient lighting and appliances can save costs while maintaining comfortable indoor temperatures. Incorporating renewable energy sources like solar panels and wind turbines can reduce pollution and help lessen our reliance on fossil fuels[

33,

43,

50,

51].

3.3.1. Integrated Approach for Better Outcomes

An interdisciplinary strategy is necessary to fully comprehend the impact of green buildings on people's well-being, the natural world, and the economy[

52,

53]. Green buildings have the potential to promote occupant contentment and lessen the building's environmental footprint. Many factors, features, and characteristics of green buildings are relevant to achieving these aims. To reduce energy consumption and promote IEQ., energy optimization techniques are essential. However, retrofitting these systems into older structures requires careful design and management[

54,

55]. The success of energy optimization techniques may be verified, and their effectiveness can be pinpointed through cautious monitoring of energy consumption [

56,

57]. Each facility's operator or owner will have unique operational practices and physical specifications, which can affect how well these tactics work. Therefore, operators and owners should consider their exceptional circumstances when deciding how best to maximize green buildings' energy efficiency[

8,

15].

3.3.2. Physical and Non-Physical Impacts

The studies reported that green buildings can improve residents' physical and mental health by improving both the physical and non-physical IAQ components of interior surroundings, including lighting, temperature, sound, and visual comfort. These all are essential to indoor environmental quality[

39,

51]. Furthermore, indoor air quality indicates a considerable impact on people's health. Green buildings can improve indoor air quality by purifying outdoor air and preventing harmful contaminants from entering the building. Furthermore, research has shown that pollutants in the outside environment contribute to increasing pollution and poor interior air quality. Furthermore, thermal comfort is given more consideration in green buildings than in traditional structures, and research shows that managing the internal environment can increase people's comfort, physical and mental health, and productivity[

58].

However, it is crucial to recognize that the quality of IEQ remnants is an integral component. Green buildings address this by reducing external noise levels, thereby improving physical and mental health [

59,

60].

3.4. Technologies for Indoor Air Quality Improvement

Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning, termed HVAC systems, are commonly used for indoor climate control, but they often have limitations in addressing IAQ concerns. While some HVAC systems incorporate air purification functions, their effectiveness against pathogens like viruses is limited. Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation (UVGI) technology has shown promise in air purification by disrupting microorganisms' D.N.A[

58,

61].

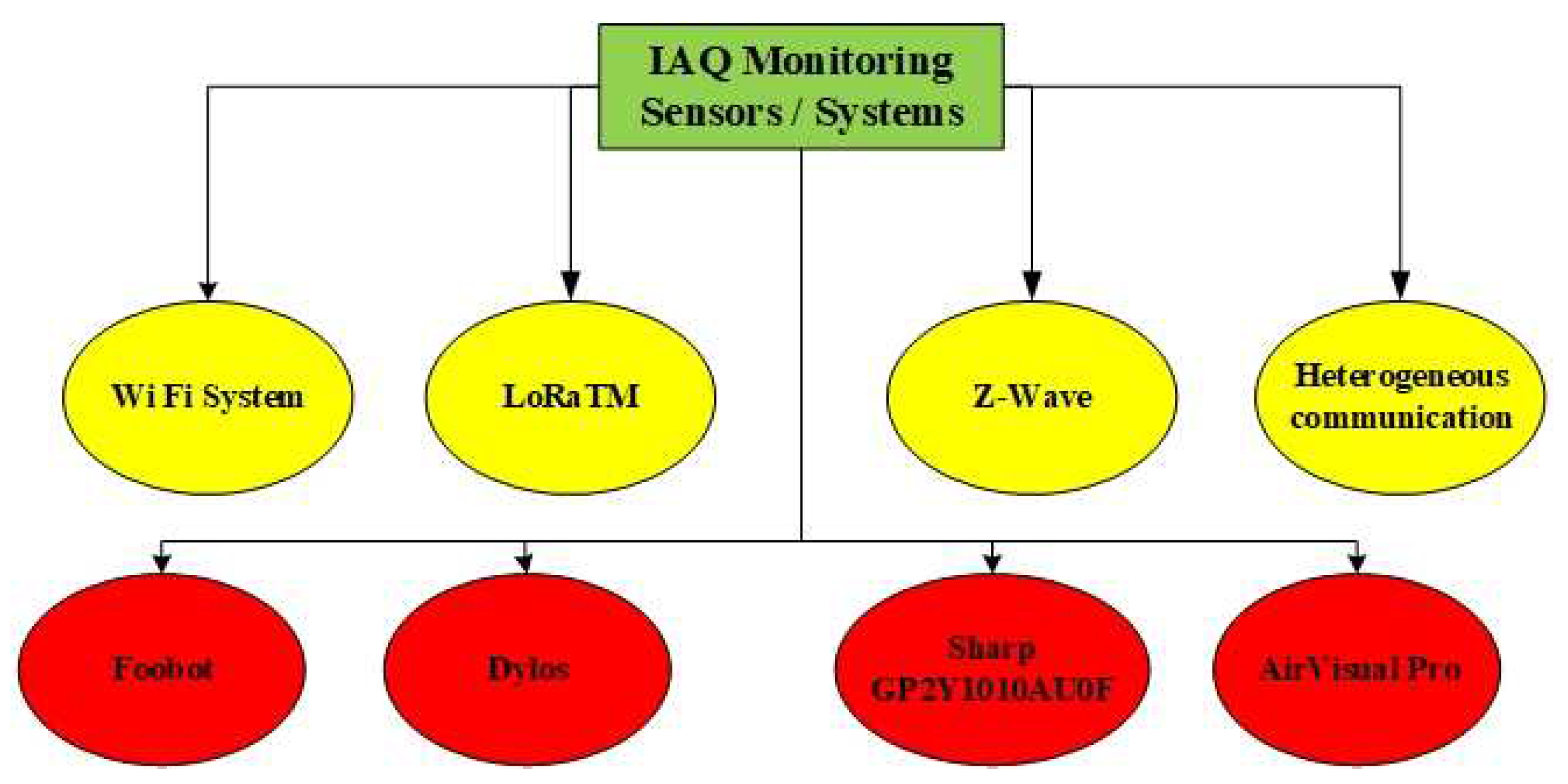

Dylos, Foobot, and AirVisual Pro, are also reported as reliable, low-cost devices for PM monitoring: Among the low-cost devices evaluated in the studies, Dylos, Foobot, and AirVisual Pro consistently demonstrated promising performance in PM monitoring. These devices showed moderate to high correlations with reference instruments, indicating their reliability for capturing mass particle levels in indoor environments. However, it is worth noting that Dylos exhibited a non-linear response and became less responsive at higher PM levels (

Figure 5).

Sharp GP2Y1010AU0F, a specific PM sensor module, was frequently employed in the reviewed studies for PM measurements. This sensor module showed good agreement with the instruments used for comparison. It was often integrated into commercially available low-cost devices such as Foobot, AirAssure, UBAS, and HAPEX (

Figure 5)[

61,

62,

63].

Wi-Fi, a form of wireless networking conforming to IEEE 802.11 standards, is the most popular choice for IAQ monitoring systems[

64]. It is designed to operate in the unlicensed I.S.M. (5-60 GHz) band of frequencies. Its quick and secure connectivity makes it an excellent option for IAQ monitoring. It includes low prices and compatibility with various electronic gadgets, including mobile phones, PCs, etc. Its dependable, secure, swift, and low-cost benefits make it a popular option for IAQ monitoring systems' gateway-to-IoT-server connection. Researchers have implemented steps to address Wi-Fi's drawbacks, such as its limited range, high price tag, and high power consumption. They utilized low-cost, low-power, and small-footprint electronics like the ESP8266 and ESP32 modules. Wi-Fi consumption in IAQ monitoring systems can also be optimized by setting connection time intervals and using the onboard Wi-Fi of devices like the Raspberry Pi (

Figure 5)[

64,

65,

66].

Indoor air quality monitoring systems frequently use Bluetooth, a low-power, low-cost wireless communication technology based on the IEEE 802.15.1 standard. This allows data transmission between mobile phones and sensor networks and short-range communication between gateways and sensors using the 2.4 GHz unlicensed I.S.M. band[

67,

68]. About 10% of IAQ monitoring systems rely on it for two-way communication. It enables smartphones to receive sensor data for processing and offers sensor values that can be queried. Bluetooth's low price and power consumption are only two of its many benefits. Inadequate security against eavesdropping, limited transmission coverage, and the possibility of interference with other wireless communication technologies, such as Wi-Fi, only constitute some of the drawbacks. Despite these limitations, Bluetooth remains a beneficial technological advancement[

67,

68,

69].

IAQ monitors make use of LoRaTM wireless technology. It uses the 868 MHz and 900 MHz I.S.M. bands and supports transfer rates of 0.3 KB/s to 50 kb/s. LoRa is perfect for outdoor monitoring because of its low price, low power consumption, and long node battery life. It is widely used as the conduit for sensor data in the heart of IAQ monitoring to reach the cloud. LoRa's adoption is more complicated than other communication technologies because it calls for mobile home gateways[

66,

69,

70]. Furthermore, environmental monitoring data is susceptible to theft due to this security protocol's shortcomings, such as poor key management and a rudimentary authentication mechanism. Resultantly, it can't be used for massive innovative home projects (

Figure 5).

About one in ten IAQ monitoring systems employs multiple generations of mobile connection protocols like 2G, 3G, 4G, and GPRS. It is constructive in mobile monitoring systems because it allows devices to interact via cellular networks. Uncertain monitoring locations call for more expansive network coverage, a problem that is difficult to handle with today's standard wireless technologies. Data may be sent, received, and processed over large cellular regions thanks to mobile communication. LTE can bypass intermediary devices like gateways and data loggers and provide raw data directly to web servers. However, mobile communication's high price and energy requirements limit its usage in IAQ monitoring systems[

66,

71,

72].

Visible light communication (V.L.C.) is an alternative to radio frequency (R.F.) wireless communication for use in IAQ monitoring systems, especially in indoor settings. For both illumination and wireless communication, V.L.C. uses L.E.D. lights. It enables close-range interaction within the 6-meter illumination radius of most indoor spaces. There is decreased electromagnetic interference and better data security using V.L.C., a form of non-RF wireless communication. V.L.C. is limited in its applicability because it depends on line-of-sight communication and can only be used in areas with direct visibility. Because of this, V.L.C. is sometimes seen as an alternative to established R.F. communication technologies for use in enclosed spaces(

Figure 5) [

70,

73].

Z-Wave is a private wireless communication standard developed for use in residential and small business automation. It may be obtained at a reasonable price and uses little energy. On the other hand, it can only transmit data at a rate of 40 kbps and has a communication range of only 30 meters. To get data from sensor nodes to central gateways, Z-Wave is employed for IAQ monitoring. Z-Wave modules are used at each node to increase the actual transmission distance. However, Z-Wave's application in IAQ monitoring systems is restricted since it operates in a frequency band that is not authorized in some countries (

Figure 5)[

66,

74].

Heterogeneous communication, which uses various wireless communication methods, is widely used in IAQ monitoring systems. Various research has addressed the topic of combining different forms of communication. Increasing communication efficiency is more difficult to implement than using a single technology. IAQ monitoring systems frequently use multiple communication protocols to guarantee interference-free operation and improved data sharing. The transmission of data from monitors to cloud platforms via a combination of GSM and Wi-Fi, for example, enables real-time communication customization based on individual circumstances. To supplement medium and long-range communication, Bluetooth is often opted for. Because of its low price and power consumption, Bluetooth is a promising option for combination with other forms of electronic communication. Sensors and gateways can talk to one another using wireless technologies like Bluetooth (

Figure 5)[

70,

75].

Numerous other technologies and sensors were used in the reviewed studies that employed various technologies and sensors for IAQ monitoring. These included commercially available low-cost devices, sensor modules, and custom-built devices. The performance of the low-cost sensors assessed in the reviewed studies varied depending on the specific sensor and instruments, study conditions, and the instruments used for comparison. Laboratory studies generally showed higher correlations between low-cost sensors and reference instruments, indicating good agreement. However, field studies demonstrated more variability, likely due to uncontrolled environmental conditions and diverse pollution sources[

66,

69].

3.5. New Zealand -A Case Study

Considering most citizens of New Zealand spend so much time indoors, it is no surprise that Al-Rawi et al. (2021) performed research and presented a case study on indoor air quality. People in New Zealand spend many of their lives indoors, making indoor air quality a major issue for their homes[

61]. Several health problems have been linked to poor IAQ, but respiratory illnesses are the most common. This case study aims to improve indoor air quality (IAQ) by modifying a dehumidifier to include germicidal irradiation technology (U.V. light) and superior filtration[

61].

A custom-built dehumidifier equipped with ultraviolet lamps, Camfil's CityPleat-200, and Dual-10 30/30 filters were employed. The North Waikato house in rural New Zealand was chosen for the experiment. Particulate matter (PM2.5) and smaller PM, relative humidity, and temperature were all measured as baseline IAQ parameters before the IAQIS was implemented. Thermal imaging samples for mold growth and air quality monitoring with a Camfil sensor were gathered to evaluate the IAQIS. The 30/30 filter and U.V. light added to the modified dehumidifier significantly reduced mold growth, lowered relative humidity and raised the temperature in the space. The relative humidity dropped by 13.3 percent, and the temperature rose by 4.1 degrees Celsius as a result of this combination[

41,

61].

In short, the study's results proved that the modified dehumidifier equipped with U.V. light and enhanced filtration could improve indoor air quality (IAQ) in homes. This synergistic effect on mold growth, relative humidity, and temperature was the most noticeable. Sustainable methods to improve indoor air quality (IAQ) and thermal comfort in older buildings are highlighted.

3.6. Limitations and Benefits of Low-cost Sensors and Instruments

To ensure accurate measurements, the reviewed studies emphasized the importance of regular calibration and validation of low-cost sensors and instruments using reference instruments. Calibration should be site-specific and consider factors like temperature and relative humidity[

74,

76]. It is crucial to address low-cost sensors' limitations and potential drift over time and under varying conditions.

Despite variances in performance and the necessity for calibration with reference instruments, the use of low-cost sensors and instruments for IAQ monitoring is supported; the evaluated studies overall promote the use of low-cost sensing technologies for IAQ monitoring. Affordability, lower electricity consumption, and ease of use are all advantages of low-cost sensors and equipment. They must, however, be entirely independent, as reference instruments are still required for validation and calibration. Technological advancements include developing low-cost sensors and introducing intelligent models for continuous calibration[

76,

77].

Nevertheless, a major amount of the low-cost sensor technology assessed can be used to qualitatively analyze air quality, offering valuable insights into indoor air conditions and assisting in personal exposure management. These can also be used as ready-to-use tools, alerting end-users to potentially high levels of pollutants and allowing them to take easy mitigation actions. Furthermore, based on the measured ranges, these devices might be considered for quantitative analysis using calibration models[

74,

76,

77].

In short, the reviewed studies demonstrate the potential of low-cost sensors and instruments for IAQ monitoring. While this performance varies, they can provide valuable insights into IAQ conditions when properly calibrated and validated. Future research should explore their applicability in different indoor environments, expand the range of pollutants studied, and improve their accuracy and reliability.

3.7. Significance of Sensor Longevity in Research

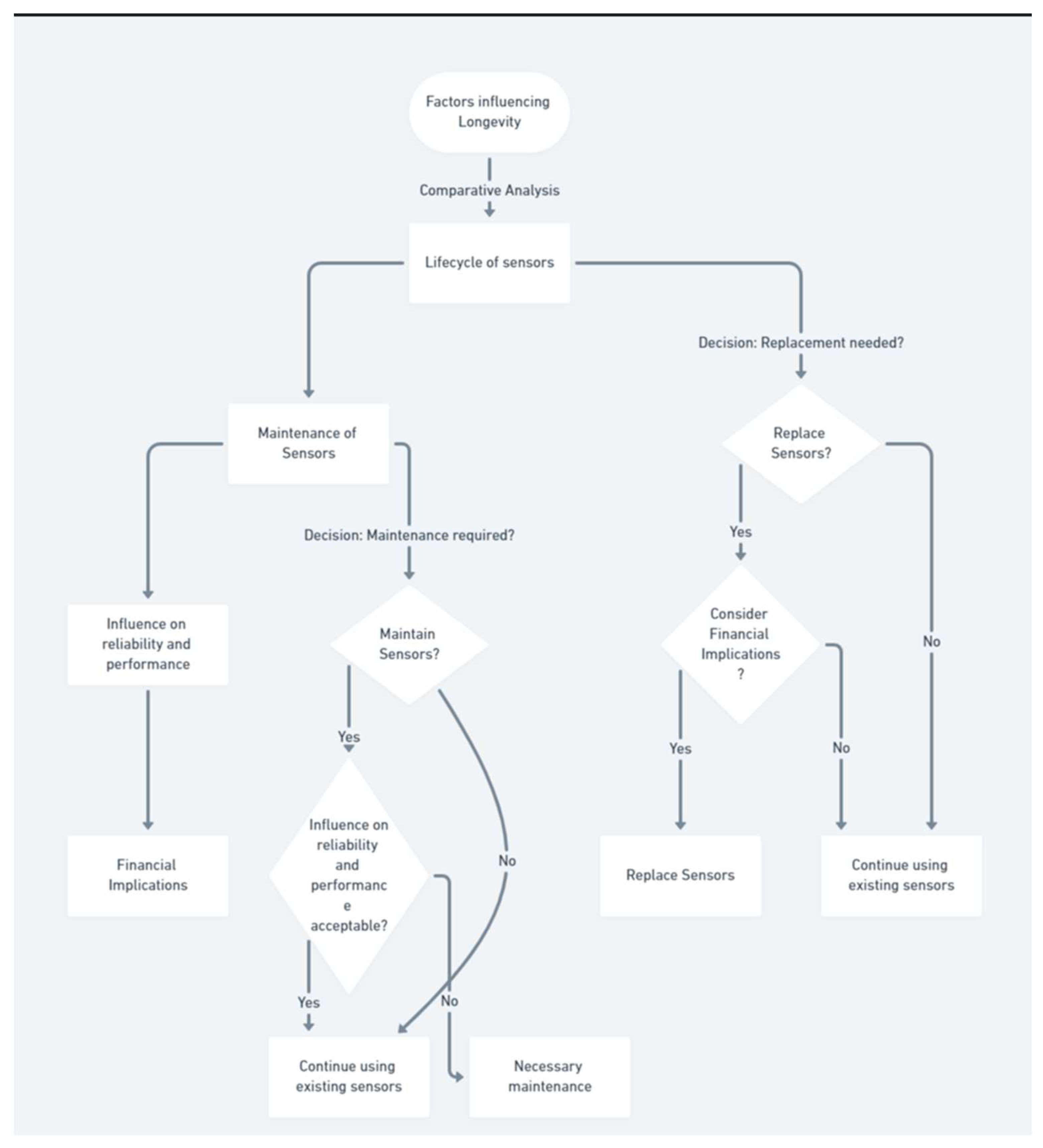

The duration of a sensor's operational functionality is a crucial aspect that influences its feasibility and economic efficiency, particularly when used on a wide scale. Utilizing low-cost sensors may have an initial affordability advantage; nevertheless, it is crucial to consider the potential for elevated long-term expenses resulting from their limited durability and frequent need for replacement. Many factors influence longevity, such as the lifecycle of sensors, comparative analysis, maintenance of sensors, influence on reliability and performance, and financial implications [

78,

79,

80].

The lifecycle of sensors can be influenced by a range of parameters, including environmental conditions, usage patterns, component quality, and manufacturing procedures. Incorporating these factors into the manuscript can yield a more holistic perspective[

78,

79,

80].

Secondly, a potential avenue for exploration is conducting a comparative analysis of the durability of several sensors discussed in the research article, including Dylos, Foobot, and AirVisual Pro. Examining the lifespan of each entity might yield valuable insights regarding their appropriateness for various applications and scales[

79,

80].

Thirdly, maintenance requirements refer to the necessary actions or procedures that must be undertaken in order to ensure the proper functioning and longevity of a particular system. An inclusive comprehension of the maintenance requirements of sensors is of utmost importance in evaluating the overall cost of ownership and the viability of implementing extensive deployments[

66,

81]. Periodic maintenance typically encompasses many tasks, such as cleaning, recalibration, software upgrades, and battery replacement.

Fourthly, Insufficient or incorrect maintenance practices can result in diminished operational efficiency, decreased precision, and potentially the malfunctioning of sensors.

Finally, over the course of time, the accumulation of maintenance expenses might become significant, especially in deployments of a large size. A comprehensive examination of these expenses in connection with the initial cost of the sensors can provide a more accurate comprehension of the financial ramifications associated with using inexpensive sensors[

78,

79,

80].

3.8. Implication of Architectural Design in Green Buildings

Indeed, the advent of intelligent technologies facilitated IAQ's improvement, but architectural design cannot be underscored. Architectural design can considerably impact the natural ventilation within a building [

8,

36]. Architects can effectively facilitate a continuous influx of fresh air, thereby contributing to the mitigation of indoor pollutants and the establishment of a pleasant thermal environment, through the strategic placement of windows, vents, and openings. Secondly, spatial planning plays a crucial role in influencing airflow and indoor air quality (IAQ) within a built environment. The configuration and layout of rooms, corridors, and common areas directly impact these factors. The implementation of intelligent spatial planning strategies contributes to the efficient utilization of natural light and the optimization of airflow patterns, resulting in a decreased reliance on artificial lighting and mechanical ventilation systems[

82,

83].

Moreover, the integration of architectural design and technology is essential for optimal outcomes. Architects have the ability to enhance indoor air quality and decrease energy usage by including various elements like sensors, HVAC systems, and energy-efficient windows in their designs. This integration of features results in the development of a cohesive system that effectively achieves both objectives[

9,

82,

84]The utilization of low-VOC materials serves as a preventive measure against the polluting of indoor air. The emission of dangerous chemicals from paints, varnishes, flooring materials and adhesives underscores the importance of utilizing certified eco-friendly materials. The incorporation of renewable and recycled resources in construction practices aligns with the overarching sustainability objectives of green buildings. These materials have the potential to mitigate the environmental impact of construction and are frequently accompanied by a reduced presence of associated contaminants. In addition, construction operations have the potential to introduce various contaminants, such as dust particles and chemical substances, into the indoor environment. Implementing appropriate management methods, such as the establishment of dust control measures and the isolation of construction zones, safeguards the IAQ[

82,

83,

84].

The adherence to building rules and green building standards, such as LEED, guarantees that the building satisfies particular IAQ criteria. It offers recommendations pertaining to ventilation, the selection of materials, and activities related to the building. Frequent assessment of IAQ throughout and following the construction process guarantees the maintenance of the intended standards within the structure. Additionally, it facilitates the implementation of necessary modifications in order to address evolving circumstances and usage trends effectively [

7,

9].

Incorporating comprehensive analyses of architectural design, building materials, construction processes, and human behavior should be intricately mingled with the preexisting discourse on technologies. For instance, elucidate the manner in which HVAC systems can be engineered to synergize with natural ventilation elements in architectural design, or expound upon the necessity of selecting building materials based on their capacity to be monitored and regulated for indoor pollution control through the utilization of sensors[

9,

83].

It is imperative to emphasize that technology constitutes merely a single component within a comprehensive and multifaceted strategy for addressing IAQ. Incorporating diverse components, encompassing both technological and non-technology aspects, plays a pivotal role in formulating a holistic approach toward preserving and auguring indoor air quality inside sustainable buildings.

3.9. Future Uncertainties and Sustainability Challenges

Recognizing future uncertainties in indoor environment quality evaluations and current sustainability difficulties in all aspects is critical. Hence, embracing new technologies and analyses is vital to address these difficulties. Few sustainable development goals also strive to ensure a sustainable way of life and the well-being of future generations. The green buildings can play a significant role in enhancing public health and supporting achieving these goals. Physical and non-physical modifications should be employed in green construction to enhance occupants' thermal, visual, and auditory comfort(Das et al., 2022; Hák et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2015a).

Furthermore, in the context of low-cost sensors and instruments, they can be employed to maintain upright performance while still being useful in indoor situations. However, the accuracy and precision of both low-cost sensors and instruments, as well as research-grade reference equipment offered by manufacturers, were occasionally available[

87]. The lack of a uniform calibration approach was crucial in establishing conclusive findings about the sensors employed[

66]. The variety of these instruments utilized for comparison, research duration, performance indices, and settings or conditions (field-based or lab-based) added to the difficulty of unambiguous interpretation. All of these elements significantly impact the performance of air quality monitoring devices. The previous study has also revealed disparities in equipment selection and sampling[

66,

87].

In addition, the most studied indoor sampling areas were offices and homes and focused on monitoring IAQ in offices and houses, with specific areas such as kitchens and bedrooms being commonly sampled [

88]. This is because people spend significant time in these indoor environments. However, the review emphasized the need for studies in other relevant indoor settings, such as hospitals, vehicles, gyms, and educational premises, where exposure to indoor air pollutants can have significant health implications[

66].

In terms of future trends, developing and implementing intelligent and efficient models capable of continuous on-field calibration, learning from measured data represents a promising direction. These models can improve the reliability and precision of low-cost sensing technology. However, further studies are obligatory to evaluate the viability of low-cost sensors and instruments by comparing them with federal reference and equivalent methods instead of other instruments. It is crucial to exercise attention in their use, as they have yet to achieve a similar level of quality as reference instruments and may struggle to measure extreme pollutant levels accurately. Implementing new strategies and technologies can refine and improve green building practices. Subsequently, it can ensure enhanced indoor air quality and human health like visual illustration (

Figure 6).

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, this in-depth analysis shows how green buildings and energy optimization measures can dramatically improve both IEQ. and occupant health. Green buildings lower their carbon footprint and improve the health and comfort of their occupants by implementing energy-efficient practices. Green buildings provide a bright and sustainable future for future generations by putting the needs of their occupants first in terms of comfort, health, and productivity.

This research shows how important IAQ is to the well-being, contentment, and productivity of building occupants in green buildings. Passive design, renewable energy utilization, and intelligent technology are all examples of energy optimization approaches that can help increase energy efficiency and increase (IAQ metrics like thermal comfort, acoustic quality, and illumination.

The advantages and disadvantages of inexpensive sensors and devices for IAQ monitoring are also discussed. Although these tools provide helpful information, they must be appropriately calibrated and validated against standard instruments to assure accuracy and reliability.

The review concludes with a need for more investigation into IAQ beyond commercial and residential buildings. The development of intelligent models for on-field calibration bolsters the potential for improved performance and utility of low-cost sensors. This extensive review also concludes that green buildings, energy optimization measures, and cutting-edge technologies significantly contribute to a healthier indoor environment and a more sustainable future. In the long run, refining and improving green building practices to address the construction sector's difficulties and ensure enhanced indoor air quality and human health requires collaborative efforts with researchers from numerous disciplines.

Author Contributions

MT Bashir, Md. Munir Hayet and Ali Sikander conceived the original idea for the research, led the data analysis process, and contributed to the drafting and revising of the manuscript. Bashir also supervised the overall research process, providing critical feedback and insights to improve the final manuscript. Saad, Alrowais and Abbas performed a significant amount of the data collection and analysis for the manuscript. Saad also took part in the drafting of the manuscript and provided insights on the green building and energy optimization aspects of the research. Nabiha contributed to the design and implementation of the research and participated in the writing and revision of the manuscript. Waqas and Zawar worked on the final template. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the faculties and staff of CECOS University, Pakistan, INTI International University, Malaysia, and Jouf University, K.S.A. These institutions have provided invaluable resources, intellectual guidance, and the conducive academic environment necessary for the conduct of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alawneh, R.; Ghazali, F.E.M.; Ali, H.; Asif, M. Assessing the Contribution of Water and Energy Efficiency in Green Buildings to Achieve United Nations Sustainable Development Goals in Jordan. Build. Environ. 2018, 146, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.S.; Zhang, J.; Sigsgaard, T.; Jantunen, M.; Lioy, P.J.; Samson, R.; Karol, M.H. Current State of the Science: Health Effects and Indoor Environmental Quality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, S.; Singh, S.K. Energy Efficient Buildings. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Res. 2014, 5, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, V.J.L.; Lo, I.M.C.; Ma, J.; Tse, K.T.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Chan, C.M. Simulation Optimisation towards Energy Efficient Green Buildings: Current Status and Future Trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciej Serda; Becker, F. G.; Cleary, M.; Team, R.M.; Holtermann, H.; The, D.; Agenda, N.; Science, P.; Sk, S.K.; Hinnebusch, R.; et al. Energy Consumption and Efficiency in Green Buildings. Int. J. Sci. Res. Dev. 2018, 5, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, F.S.; Sa’di, B.; Safa-Gamal, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Alrifaey, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S. Energy Efficiency in Sustainable Buildings: A Systematic Review with Taxonomy, Challenges, Motivations, Methodological Aspects, Recommendations, and Pathways for Future Research. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2023, 45, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Krogmann, U.; Mainelis, G.; Rodenburg, L.A.; Andrews, C.J. Indoor Air Quality in Green Buildings: A Case-Study in a Residential High-Rise Building in the Northeastern United States. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. - Part A Toxic/Hazardous Subst. Environ. Eng. 2015, 50, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.; Adibhesami, M.A.; Bazazzadeh, H.; Movafagh, S. Green Buildings: Human-Centered and Energy Efficiency Optimization Strategies. Energies 2023, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Melkania, N.P.; Nain, A. Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) in Green Buildings, a Pre-Requisite to Human Health and Well-Being. Digit. Cities Roadmap IoT-Based Archit. Sustain. Build. 2021, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Adhikary, S.; Das, R.K.; Banerjee, A.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Paul, S.; Pathak, S.; Duttaroy, A.K. Bioactive Food Components and Their Inhibitory Actions in Multiple Platelet Pathways. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincinelli, A.; Martellini, T. Indoor Air Quality and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Hu, S.; Lu, M.; He, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G. Analysis of Human Electroencephalogram Features in Different Indoor Environments. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cionita, T.; Jalaludin, J.; Adam, N.M.; SIREGAR, J.P. Assessment of Children’s Health and Indoor Air Contaminants of Day Care Centre in Industrial Area. Iran. J. Public Health 2014, 43, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X. New Dimension to Green Buildings: Turning Green into Occupant Well-Being. Buildings 2021, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Ji, W.; Wang, Z.; Lin, B.; Zhu, Y. A Review of Operating Performance in Green Buildings: Energy Use, Indoor Environmental Quality and Occupant Satisfaction. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Ramalho, O.; Mandin, C. Indoor Air Quality Requirements in Green Building Certifications. Build. Environ. 2015, 92, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhang, L.; Sun, S.; Yu, X.; Dong, X.; Wu, T.; Ou, J. Electrostatic Self-Assembled Carbon Nanotube/Nano Carbon Black Composite Fillers Reinforced Cement-Based Materials with Multifunctionality. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2015, 79, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, W.; Landis, A.E.; Jones, A.K.; Schaefer, L.A.; Bilec, M.M. Indoor Environmental Quality in a Dynamic Life Cycle Assessment Framework for Whole Buildings: Focus on Human Health Chemical Impacts. Build. Environ. 2013, 62, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaoka, H.; Suzuki, N.; Eguchi, A.; Matsuzawa, D.; Mori, C. Impact of Exposure to Indoor Air Chemicals on Health and the Progression of Building-Related Symptoms: A Case Report. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestka, J.J.; Yike, I.; Dearborn, D.G.; Ward, M.D.W.; Harkema, J.R. Stachybotrys Chartarum, Trichothecene Mycotoxins, and Damp Building–Related Illness: New Insights into a Public Health Enigma. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 104, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A.; Yusoff, M.Z.; Ng, K.C. The Potential Influence of Building Optimization and Passive Design Strategies on Natural Ventilation Systems in Underground Buildings: The State of the Art. Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 2019, 92, 103065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, O.K. Passive Design Strategies for Residential Buildings in a Hot Dry Climate in Nigeria. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 128, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Elaouzy, Y.; El Fadar, A. Energy, Economic and Environmental Benefits of Integrating Passive Design Strategies into Buildings: A Review. Renew. Sustain. energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali, A.; Valipour, A. Prioritization of Passive Measures for Energy Optimization Designing of Sustainable Hospitals and Health Centres. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovatfard, A.; Heravi, G. Identifying Key Performance Indicators for Healthcare Facilities Maintenance. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharoon, D.A.; Rahman, H.A.; Omar, W.Z.W.; Fadhl, S.O. Historical Development of Concentrating Solar Power Technologies to Generate Clean Electricity Efficiently–A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 996–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palzer, A.; Henning, H.-M. A Comprehensive Model for the German Electricity and Heat Sector in a Future Energy System with a Dominant Contribution from Renewable Energy Technologies–Part II: Results. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantini, M.; Loprieno, A.D.; Porta, P.L. A Life Cycle Approach to Green Public Procurement of Building Materials and Elements: A Case Study on Windows. Energy 2011, 36, 2473–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Mohamad Zin, R.; Štreimikienė, D.; Mardani, A.; Ismail, M. The Role of Green Building Materials in Reducing Environmental and Human Health Impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, L.; Manfren, M.; Nastasi, B. Energy Efficiency, Demand Side Management and Energy Storage Technologies–A Critical Analysis of Possible Paths of Integration in the Built Environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 95, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P.; Breivik, C.; Røkenes, H.D. Building Integrated Photovoltaic Products: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Research Opportunities. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 100, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleyl, J.W.; Bareit, M.; Casas, M.A.; Chatterjee, S.; Coolen, J.; Hulshoff, A.; Lohse, R.; Mitchell, S.; Robertson, M.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Office Building Deep Energy Retrofit: Life Cycle Cost Benefit Analyses Using Cash Flow Analysis and Multiple Benefits on Project Level. Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrizadeh, S.; Yao, R.; Yuan, F.; Awbi, H.; Bahnfleth, W.; Bi, Y.; Cao, G.; Croitoru, C.; de Dear, R.; Haghighat, F. Indoor Air Quality and Health in Schools: A Critical Review for Developing the Roadmap for the Future School Environment. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wu, J. Economic Returns to Residential Green Building Investment: The Developers’ Perspective. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 47, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adochiei, F.-C.; Nicolescu, Ş.-T.; Adochiei, I.-R.; Seritan, G.-C.; Enache, B.-A.; Argatu, F.-C.; Costin, D. Electronic System for Real-Time Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 international conference on e-health and bioengineering (EHB), IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Angelon-Gaetz, K.A.; Richardson, D.B.; Lipton, D.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Lamb, B.; LoFrese, T. The Effects of Building-related Factors on Classroom Relative Humidity among N Orth C Arolina Schools Participating in the ‘F Ree to B Reathe, F Ree to T Each’Study. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, A.; Jawahir, I.S. Optimization of Sustainable Machining of Ti6Al4V Alloy Using Genetic Algorithm for Minimized Carbon Emissions and Machining Costs, and Maximized Energy Efficiency and Human Health Benefits. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition; American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2021; Vol. 85567, p. V02BT02A061.

- Saini, J.; Dutta, M.; Marques, G. A Comprehensive Review on Indoor Air Quality Monitoring Systems for Enhanced Public Health. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2020, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, N.; Liang, H.; Gao, X. The Effect of Built Environment on Physical Health and Mental Health of Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dion, H.; Evans, M. Strategic Frameworks for Sustainability and Corporate Governance in Healthcare Facilities; Approaches to Energy-Efficient Hospital Management. Benchmarking An Int. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluyssen, P.M.; Roda, C.; Mandin, C.; Fossati, S.; Carrer, P.; De Kluizenaar, Y.; Mihucz, V.G.; de Oliveira Fernandes, E.; Bartzis, J. Self-reported Health and Comfort in ‘Modern’Office Buildings: First Results from the European OFFICAIR Study. Indoor Air 2016, 26, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Nagy, Z. Comprehensive Analysis of the Relationship between Thermal Comfort and Building Control Research-A Data-Driven Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2664–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Laurent, J.G.C.; Flanigan, S.S.; Eitland, E.S.; Spengler, J.D. Green Buildings and Health. Curr. Environ. Heal. reports 2015, 2, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wokekoro, E. Public Awareness of the Impacts of Noise Pollution on Human Health. World J Res Rev 2020, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Slabbekoorn, H. Noise Pollution. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R957–R960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, X.; Ann, T.W.; Darko, A.; Wu, Z. Critical Factors in Site Planning and Design of Green Buildings: A Case of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tu, Y. Green Building, pro-Environmental Behavior and Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore. Cities 2021, 108, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.D.L. Carbon Materials for Structural Self-Sensing, Electromagnetic Shielding and Thermal Interfacing. Carbon N. Y. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X. A Hybrid Method of Dynamic Cooling and Heating Load Forecasting for Office Buildings Based on Artificial Intelligence and Regression Analysis. Energy Build. 2018, 174, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, S. Optimization of Passive Solar Design Strategies: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinakis, V.; Doukas, H.; Karakosta, C.; Psarras, J. An Integrated System for Buildings’ Energy-Efficient Automation: Application in the Tertiary Sector. Appl. Energy 2013, 101, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Clements-Croome, D.; Wang, Q. Move beyond Green Building: A Focus on Healthy, Comfortable, Sustainable and Aesthetical Architecture. Intell. Build. Int. 2017, 9, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Gupta, R.; Kutnar, A. Sustainable Development and Green Buildings. Drv. Ind. 2013, 64, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Gupta, V.; Nihar, K.; Jana, A.; Jain, R.K.; Deb, C. Tropical Climates and the Interplay between IEQ and Energy Consumption in Buildings: A Review. Build. Environ. 2023, 110551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Cheong, D.; Sekhar, C. A Review of Occupancy-Based Building Energy and IEQ Controls and Its Future Post-COVID. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 804, 150249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Shang, W.; Liu, J.; Xue, M.; Wang, C. Achieving Better Indoor Air Quality with IoT Systems for Future Buildings: Opportunities and Challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 164858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Mahecha, S.D.; Moreno, S.A.; Licina, D. Integration of Indoor Air Quality Prediction into Healthy Building Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergefurt, L.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; Appel-Meulenbroek, R.; Arentze, T. The Physical Office Workplace as a Resource for Mental Health–A Systematic Scoping Review. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, A.; Milner, K. Changes in Productivity, Psychological Wellbeing and Physical Wellbeing from Working in a’green’building. Work 2014, 49, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Kumar, V.; Saha, P. Importance of Indoor Environmental Quality in Green Buildings. In Proceedings of the Environmental Pollution: Select Proceedings of ICWEES-2016; Springer, 2018; pp. 53–64.

- Al-Rawi, M.; Ikutegbe, C.A.; Auckaili, A.; Farid, M.M. Sustainable Technologies to Improve Indoor Air Quality in a Residential House – A Case Study in Waikato, New Zealand. Energy Build. 2021, 250, 111283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Sousan, S.; Streuber, D.; Zhao, K. GeoAir—A Novel Portable, GPS-Enabled, Low-Cost Air-Pollution Sensor: Design Strategies to Facilitate Citizen Science Research and Geospatial Assessments of Personal Exposure. Sensors 2021, 21, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asha, P.; Natrayan, L.; Geetha, B.T.; Beulah, J.R.; Sumathy, R.; Varalakshmi, G.; Neelakandan, S. IoT Enabled Environmental Toxicology for Air Pollution Monitoring Using AI Techniques. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Krogmann, U.; Mainelis, G.; Rodenburg, L.A.; Andrews, C.J. Indoor Air Quality in Green Buildings: A Case-Study in a Residential High-Rise Building in the Northeastern United States. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part A 2015, 50, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzlu, M.; Pipattanasomporn, M.; Rahman, S. Review of Communication Technologies for Smart Homes/Building Applications. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT ASIA); IEEE; 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Review of Communication Technology in Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System and Challenges. Electron. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.P.; Li, X. AirSniffer: A Smartphone-Based Sensor System for Body Area Climate and Air Quality Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2016 10th International Symposium on Medical Information and Communication Technology (ISMICT); IEEE; 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi, K.; Lohani, D. An Internet of Things Framework to Forecast Indoor Air Quality Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Metaheuristics Algorithms, and Applications: First Symposium, SoMMA 2019, Trivandrum, India, December 18–21, 2019, Revised Selected Papers 1; Springer, 2020; pp. 90–104.

- Kanál, A.K.; Kovácsházy, T. IoT Solution for Assessing the Indoor Air Quality of Educational Facilities. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC); IEEE, 2019; pp. 1–5.

- Zhou, M.; Abdulghani, A.M.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Internet of Things (IoT) Enabled Smart Indoor Air Quality Monitoring System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 international conference on computing, networks and internet of things; 2020; pp. 89–93.

- Karami, M.; McMorrow, G.V.; Wang, L. Continuous Monitoring of Indoor Environmental Quality Using an Arduino-Based Data Acquisition System. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 19, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, R.; Zaidi, S.M.H.; Shakir, M.Z.; Shafi, U.; Malik, M.M.; Haque, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Zaidi, S.A.R. Internet of Things (Iot) Based Indoor Air Quality Sensing and Predictive Analytic—A COVID-19 Perspective. Electronics 2021, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.Q.; Rachim, V.P.; Chung, W.-Y. EMI-Free Bidirectional Real-Time Indoor Environment Monitoring System. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 5714–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Perez, A.; Bierer, B.; Scholz, L.; Wöllenstein, J.; Palzer, S. A Wireless Gas Sensor Network to Monitor Indoor Environmental Quality in Schools. Sensors 2018, 18, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, Q. A High Precise E-Nose for Daily Indoor Air Quality Monitoring in Living Environment. Integration 2017, 58, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Á.; Adeli, H.; Reis, L.P.; Costanzo, S. New Knowledge in Information Systems and Technologies: Volume 3; Springer, 2019; Vol. 932; ISBN 3030161870.

- Marques, G.; Pitarma, R. A Cost-Effective Air Quality Supervision Solution for Enhanced Living Environments through the Internet of Things. Electronics 2019, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeman, N.M.; Murphy, C.T. Regulation of Reproduction and Longevity by Nutrient-Sensing Pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Horr, Y.; Arif, M.; Kaushik, A.; Mazroei, A.; Katafygiotou, M.; Elsarrag, E. Occupant Productivity and Office Indoor Environment Quality: A Review of the Literature. Build. Environ. 2016, 105, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, V.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.-C. Indoor Air Pollution, Related Human Diseases, and Recent Trends in the Control and Improvement of Indoor Air Quality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostek, K.; Wiśniewski, M.; Skomra, W. Analysis and Evaluation of Business Continuity Measures Employed in Critical Infrastructure during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustain. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftness, V.; Hakkinen, B.; Adan, O.; Nevalainen, A. Elements That Contribute to Healthy Building Design. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megahed, N.A.; Ghoneim, E.M. Indoor Air Quality: Rethinking Rules of Building Design Strategies in Post-Pandemic Architecture. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, J.D.; Chen, Q. Indoor Air Quality Factors in Designing a Healthy Building. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 567–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Roy, D.; Sahoo, N.; Roy, U. IFIT3 Gene Expression And Function Contribute To Hand Pathology Even With Antiretroviral Therapies (CARTS). Innov. Aging 2022, 6, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable Development Goals: A Need for Relevant Indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojer, H.; Branco, P.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I. V On-Field Performance Test and Calibration of Two Commercially Available Low-Cost Sensors Devices for CO 2 Monitoring. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 2022, 5, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Moreno-Rangel, A.; Baek, J.; Obeng, A.; Hasan, N.T.; Carrillo, G. Indoor Air Quality and Health Outcomes in Employees Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. Atmosphere (Basel). 2021, 12, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).