1. Introduction

A modern water bike Explorer-1 (

Figure 1, [

1]) can develop speed up to 2.7 m/s using only human muscle power at the total weight of 240 kg. This rather high speed was achieved by improving the shape of pontoons (shown in yellow) and using an effective propeller [

1]. Similar vehicles can be used not only for recreation and fitness, but also for transportation, especially with the use of electrical power. To increase the speed and the commercial effectiveness (weight-to-drag ratio) of such vehicles, special shaped pontoons of low drag (similar to the body shape of the best swimmers) can be proposed.

The maximal speed of fastest fish can be around 30 m/s (e.g., sailfish, swordfish, black marlin, etc., [

2,

3,

4,

5]). A very sharp nose – rostrum- of these animals probably allows them to remove the boundary layer separation and high pressures on the body surface. and to reduce the wave resistance when moving near the water surface. The corresponding axisymmetric bodies with concave noses have no pressure peaks on their shape [

6] and much lower values of the vertical velocity on the water surface [

7]. Since the reason of the waves on the water surface is the high pressure on the vessel bow and stern [

8,

9,

10,

11], these special shaped bodies could be used to reduce the wave resistance.

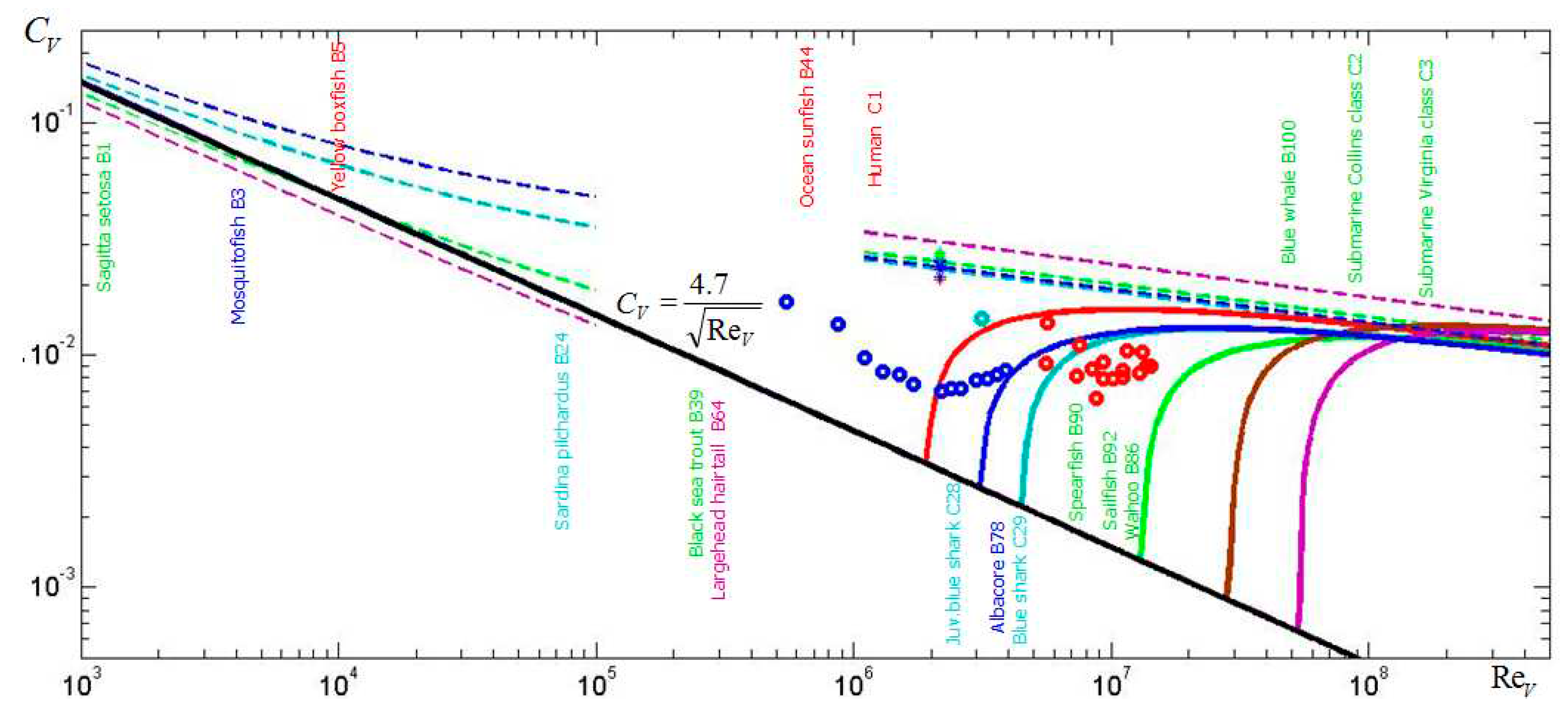

It was shown in [

12] that axisymmetric bodies similar to the trunks of high speed fish can ensure the underwater flow pattern without boundary separation and low drag. The expected values of volumetric drag coefficient

can be reduced more than twice in comparison with known shapes in the range of volumetric Reynolds numbers

from 1 to 10 millions (see [

12,

13],

Figure 2). The corresponding volumetric coefficients can be calculated as follows:

where

V is the volume (displacement),

is speed,

X is the total drag ;

and

are density and kinematic viscosity of water.

Upper dashed lines correspond to the laminar flow, lower dashed lines – to the turbulent one. Drag coefficients for standard bodies are shown in dark blue for

L/D=4.5; in blue for

L/D=5.9; in green for

L/D=12.4 and magenta for

L/D=33.3. Solid lines represent volumetric drag cofficients for special shaped bodies: unseparated unclosed body UA-2 (

L/D=3.52; red line, [

14] ); closed bodies UA-4.5c “Albacore” (

L/D=4.5; dark blue line), UA-5.9c “Blue shark” (

L/D=5.9; blue line), UA-12.4c “Sailfish” (

L/D=12.4; green line), UA-33.3c “Largehead hairtail” (

L/D=33.3; magenta line); unclosed body UA-23.3 (

L/D=23.3; brown line). Markers show the experimental data for standard (“stars”, [

15]]) and other special shaped bodies of revolution (“circles”): red – “Dolphin” body [

16], blue - Goldschmied body [

15], dark blue – Hansen&Hoyt body, [

17]. Typical values of volumetric Reynolds numbers are shown by names.

The volumetric Reynolds number for Explorer-1 is approximately 1.3 million. It means that larger and faster vehicles with special shaped pontoons can also have a lower drag (see black solid line in

Figure 2). Since such pontoons move near the water surface, the friction and wave drags of corresponding bodies of revolution has to be evaluated.

In this paper we will concentrate on theoretical estimations of the total drag of special shaped bodies of revolution moving near the water surface. We will discuss also the opportunities of using electrical accumulators for the water bikes and similar vehicles and problems connected with manufacturing of proposed shapes.

2. Friction drag on floating bodies of revolution similar to the shape of the fastest fish

Let us assume that the axisymmetric shape of pontoons is similar to the bodies of the fastest fish and removes the boundary layer separation. If the distance between pontoons is large enough, the interference and pressure drag connected with separation can be neglected. Then the hydrodynamic forces acting on each pontoon can be estimated as for single hull of volume V and length L.

The total drag

X on an slender axisymmetric unseparated body can be estimated with the use of the following formula for the volumetric drag coefficient in a laminar unbounded flow, [

12]:

The solid black line represents this relationship in

Figure 2. Equation (1) shows that the volumetric drag coefficient does not depend on the hull shape, provided it is slender (with high values of

L/D ratio) and ensures the laminar flow pattern without separation. Formula (1) is valid only for the volumetric Reynolds numbers

lower than the critical one, [

18]:

At higher Reynolds numbers, the turbulence appears in boundary layer and increases the friction drag. The corresponding values of the drag coefficient can be calculated with the use of flat plate concept [

19] and start to deviate from the relationship (1) (see solid lines in

Figure 2). At supercritical Reynolds numbers the shape peculiarities have to be taken into account and the drag coefficient is much higher (see

Figure 2). For example, at high Reynolds numbers it can be estimated as follows [

12,

18]:

for the unbounded attached turbulent flow (see

Figure 2).

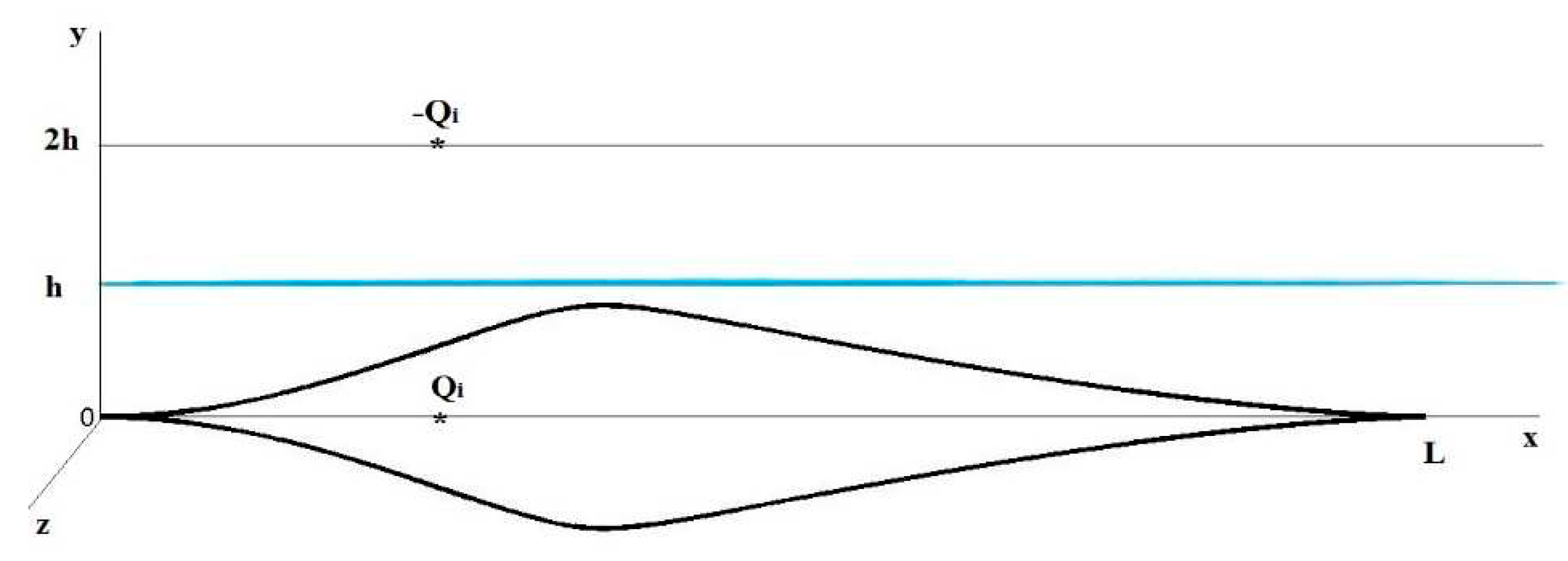

If a slender body of revolution moves horizontally at constant speed

at depth

h along its axis of symmetry

Ox (

h is the distance between the undisturbed water surface and the body axis of symmetry, see

Figure 3), its wave resistance must be taken into account. The case

h<D/2 changes also the friction drag.

Assuming the friction drag

Xf to be proportional to the submerged area

Sf, the corresponding volumetric drag coefficient (based on the displacement

Vf)

will be proportional to

(

is the density of water). Introducing the shape coefficients

and

corresponding to the part of the body wetted by water (i.e.

and

) and Equations (1) and (4) yield:

In particular, at h = 0, the corresponding values = 0.5 and according to Equation (2):

Formula (6) shows that floating bodies of revolution may have lower friction drag coefficient in comparison with the underwater ones. Nevertheless, the pressure drag connected with the waves on the water surface (even without the boundary-layer separation) may yield rather high levels of total drag.

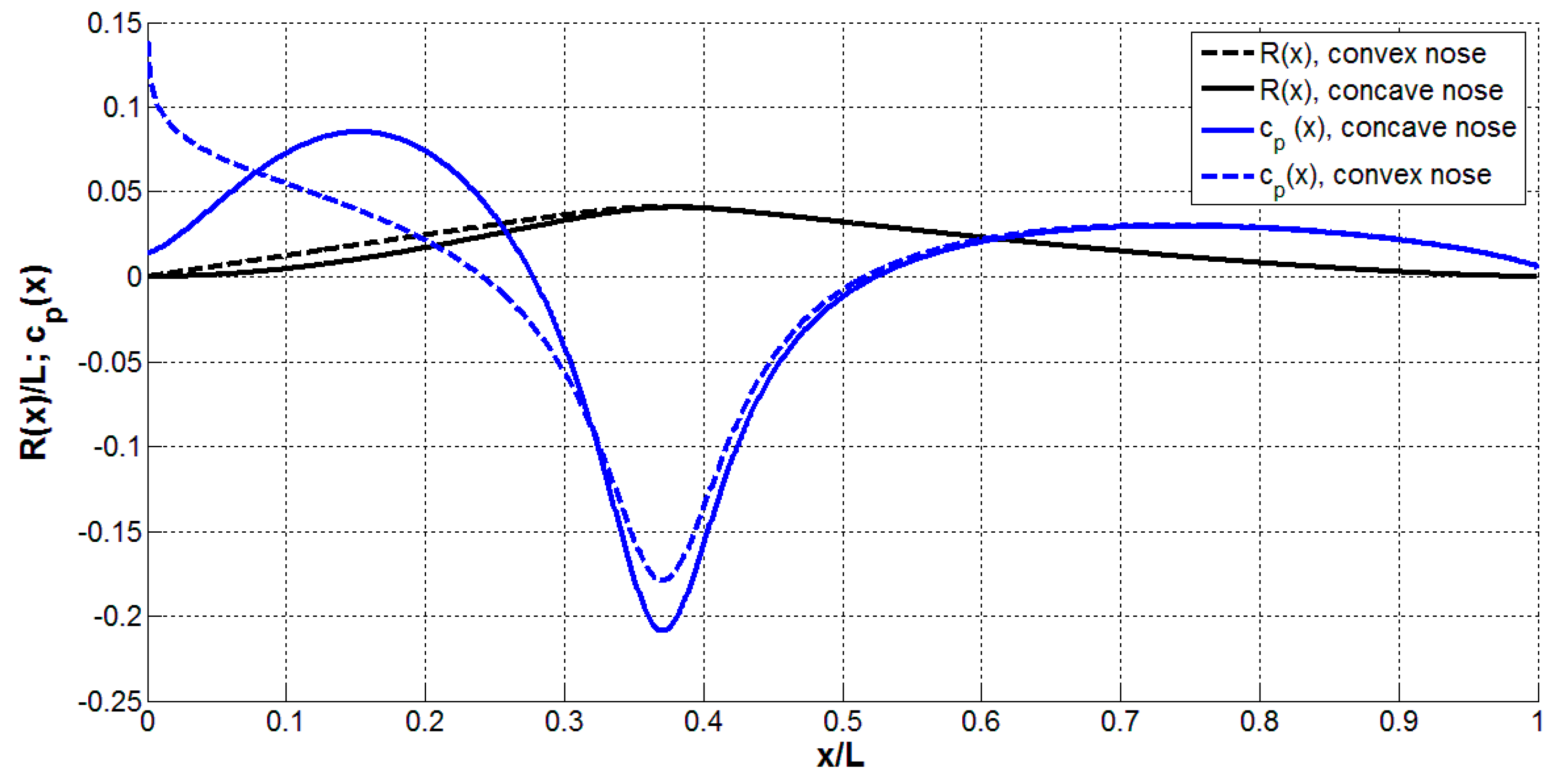

Let us calculate the values of function

f(h) for the body of revolution obtained in [

6] with the use of sources and sinks located on the axis of symmetry. Their intensity is given by:

The values of parameters

c , d,

, and

x* were adjusted to remove the stagnation point on the nose. The absence of the very small velocities near this point allows reducing the maximal pressure on the body surface and the wave drag [

7]. Black solid line in

Figure 4 represents an example of such body of revolution with a sharp concave nose, similar to shape of sailfish. The pressure coefficient

on its surface at infinite depth is shown by the blue solid line;

p(x) is pressure on the hull surface;

is the pressure in the ambient flow at the same depth). We see the absence of a stagnation point at nose, since

doesn’t tend to 1.0 at

.

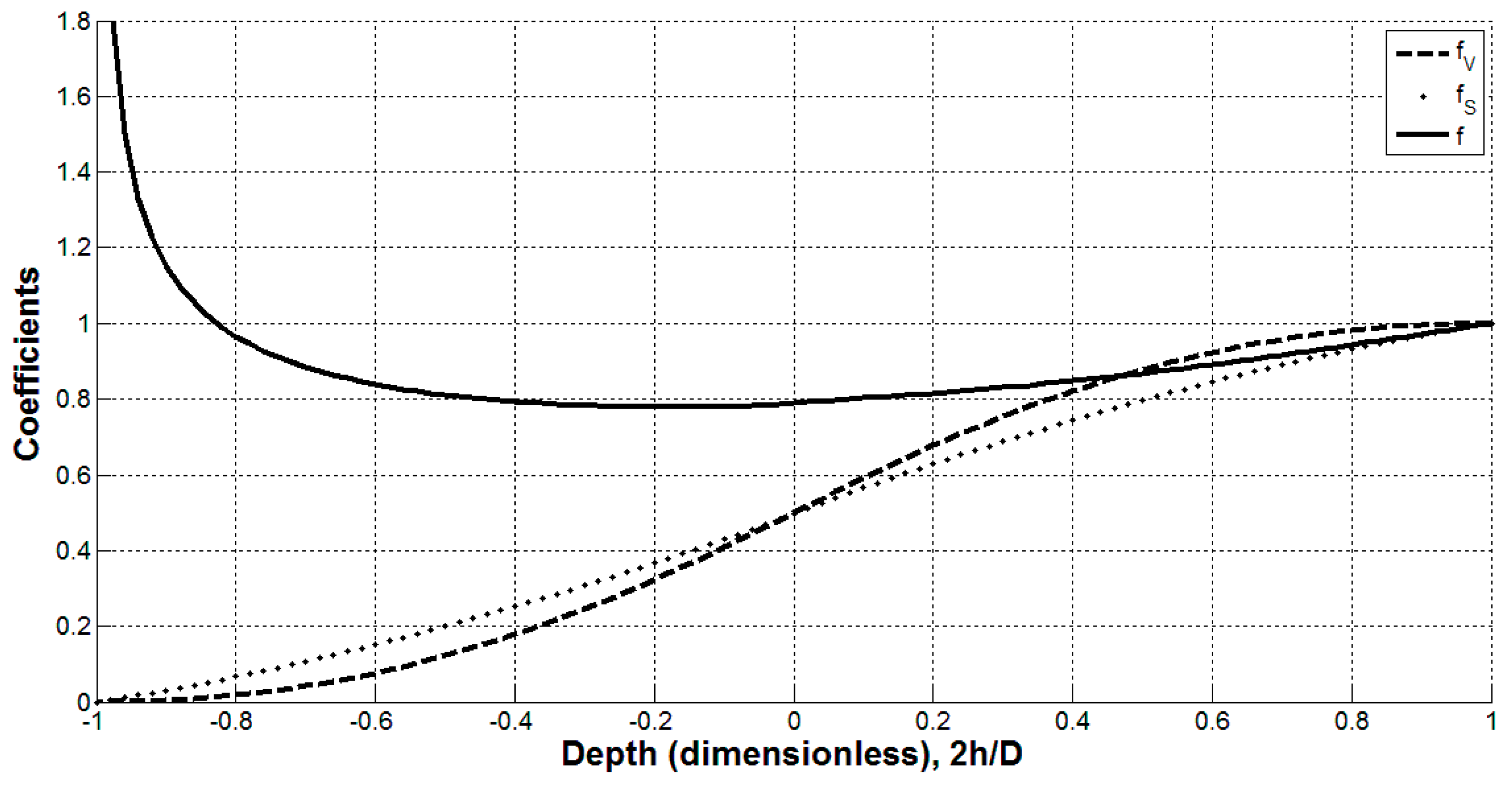

Figure 5 represents the results of calculations of shape coefficients

fS, fV (dotted and dashed lines, respectively) and the friction drag coefficient

f (the solid line) for the slender body of revolution similar to the sailfish shape (shown in

Figure 4 by the black solid line). The minimum value of

f = 0.7782 correspond to the dimensionless depth of steady horizontal movement

h/D = -0.09 and is only 2% lower than the value given by (6) and corresponding to

h = 0. If we are interested in only positive values of

h, the minimum friction drag can be achieved at the smallest values of depth, e.g.,

h/D<0.1 (see the solid line in

Figure 5).

3. Estimations of vertical velocities on the water surface

The wave drag caused by the hulls with a sharp concave nose (similar to the rostrum of the fastest fish [

2,

3,

4,

5] and shown in

Figure 4) can be estimated with the use of the vertical velocities on the water surface. In order to simulate the presence of the water boundary, let us use sources and sinks with intensities

Qi located on the axis of symmetry

Ox and sources and sinks of opposite intensities

–Qi located on the line

y=2h,

z=0 (see

Figure 3, [

20]). Then the vertical velocities on the water surface at the plane of symmetry (

y=h,

z=0) can be estimated as follows, [

7]:

The discrete values of

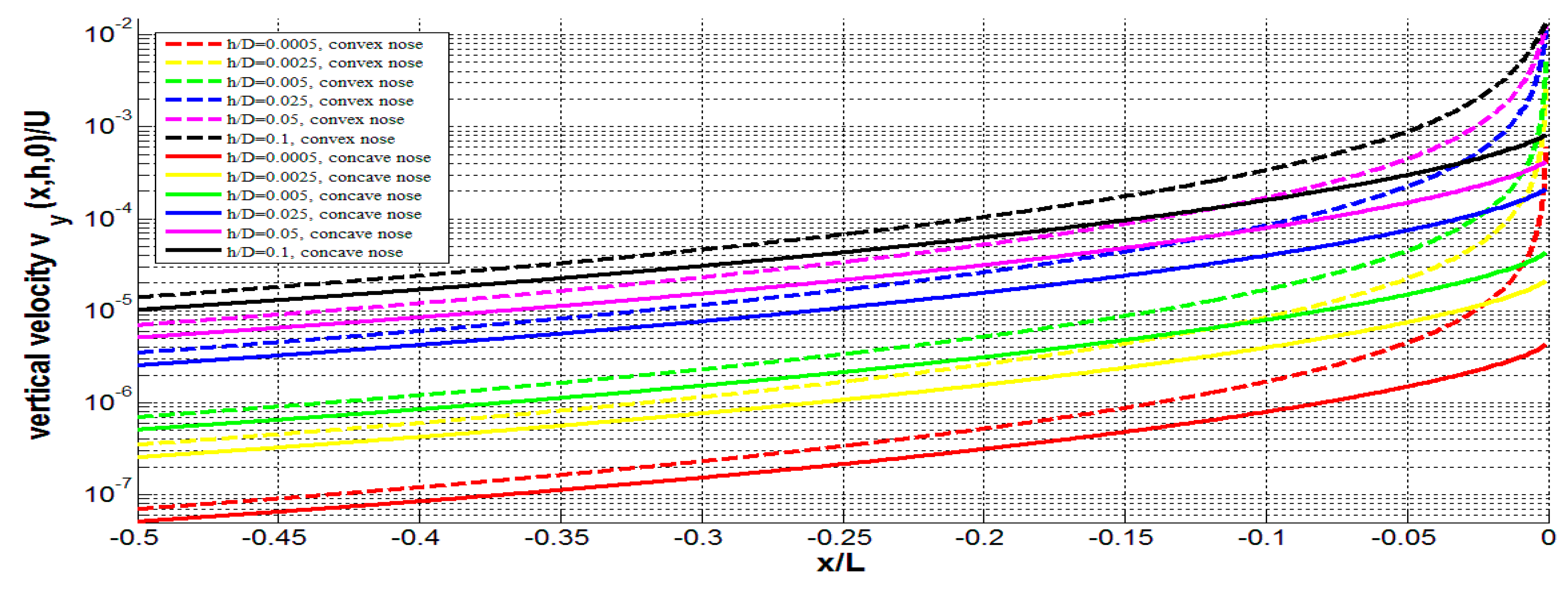

Qi corresponding to the distribution (7) have been used in eq. (8) to estimate the deformation of the water surface and corresponding wave resistance. Solid lines in

Figure 6 represent the results of calculations of the vertical velocity on the water surface upstream of the concave nose at different values of the dimensionless depth

h/D. The solid lines in

Figure 4 show the radius

R(x) of corresponding body with rostrum (black) and the pressure coefficient on its surface at infinite depth (blue).

The slender bodies of revolution with convex nose have a stagnation point and a pressure peak on the surface. To illustrate this fact, we have used the source distribution:

and a sets of constant parameters

a, b,

, and

x* in order to calculate an example of a body of the same

L/D ratio with convex nose (see the dashed black line in

Figure 4), the pressure coefficient on its surface in unbounded flow (see the dashed blue line in

Figure 4) and formula (8) for corresponding values of

(see dashed lines in

Figure 6).

Figure 6 illustrates that the vertical velocities on the water surface upstream to the shapes with the concave nose can be significantly reduced in comparison with the similar slender shapes with convex nose (compare corresponding solid and dashed lines). This effect is especially strong at small depths (compare red and black lines) due to the absence of high pressures on the hull.

Both shapes shown in

Figure 4 have no stagnation points (and high pressures) on the trailing edge (see blue lines at

x=1). Thus, we can expect small vertical velocities downstream to the trailing edge.

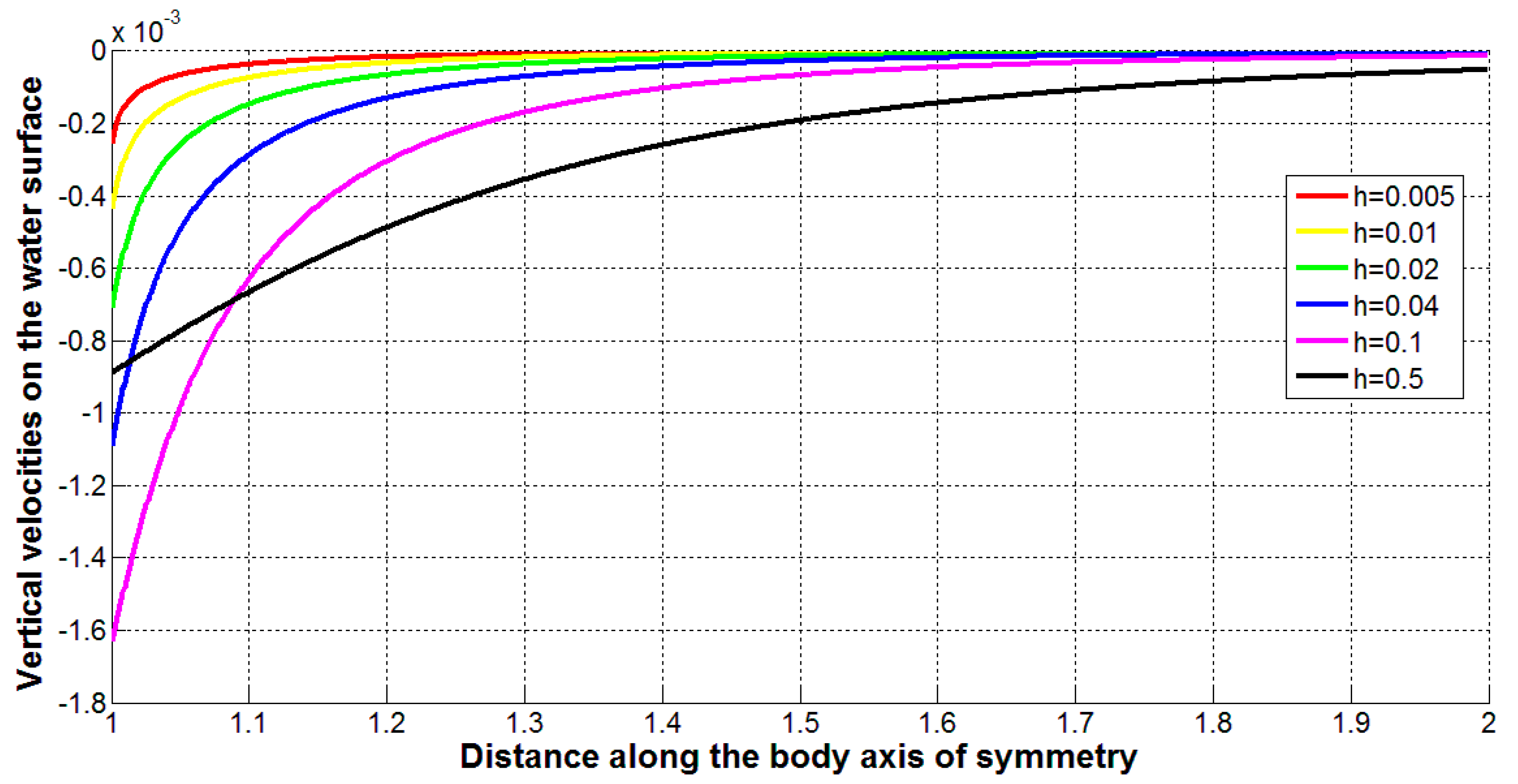

Figure 7 illustrates the results of calculations for the body with concave nose (see the black solid line in

Figure 4). The magnitudes of vertical velocities are higher than the corresponding values upstream to the leading edge (compare, for example, the red line in

Figure 7 and the green solid line in

Figure 6). Nevertheless, the magnitudes of the vertical velocities upstream to the convex nose are much higher (compare, for example, the red line in

Figure 7 and the green dashed line in

Figure 6). Probably, the magnitude of the vertical velocities can be reduced with the use of a more concave trailing edge.

It is well known that the pressure peaks on the hulls cause deformations of water surface and wave resistance [

8,

9,

10]. To reduce this drag the elongated wave-piercing hulls and bulbous bows are used [

11,

21,

22,

23]. The proposed shapes with very sharp concave noses and tails open the prospects for further reduction of wave resistance. Since the wave drag is expected to be low, formulas (1) and (3) can be used to estimate the total drag on floating special shaped hulls with concave noses, since the smallest values of depth

h can be recommended.

Since such hulls have been never tested (similar shapes exist only in nature - the fastest fish give us the examples), the improved water bike pontoons give us a good opportunity to verify the theoretical estimations on the real vehicle. After change of the pontoons of the prototype (e.g., [

1]) by improved ones (similar to shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), we could estimate the increase of the maximal speed with the use of the same human muscles power.

Let us make some estimations for Explorer-1 ([

1],

=2.7 m/s; displacement 0.24 m

3). For the pontoons of an improved water bike, we can use two almost half-submerged bodies of revolution similar to shown in

Figure 4 by the black solid line with the volume of 0.24 m

3 each. Then the total drag can be estimated with the use of formulae (1): the volumetric Reynolds number is approximately 1.3 million (

=2.7 m/s;

V=0.24 m

3;

m

2/s at 10 °C) and the volumetric drag coefficient

. This value is more then twice lower than the drag on Hansen and Hoyt body [

17] tested at the same volumetric Reynolds number (see.

Figure 2).

According to the formulae (1), the volumetric drag coefficients of improved water bikes can be much lower at higher subcritical Reynolds numbers. If we use the special shaped pontoons of length L=3m (the same as for Explorer-1) and volume 0.24 m3 each, than the critical Reynolds number will be around 4.4 million (see Equation (2)). It means, that even at speed 9 m/s, we could expect the laminar flow pattern and . In the next Section we will answer the question: is this speed achievable with the use of the human muscles power only?

4. Estimations of maximal velocities and ranges

The mechanical power

P of a vehicle can be estimated as the product of its speed

by the thrust (which is equal to the total drag

X in steady motion). Then with the use of the volumetric drag coefficient

, we can obtain the following relationship:

Taking the characteristics of Explorer-1, [

1]: the maximum speed

=2.7 m/s, the displacement

V=0.24 m

3, and

(this value was measured on the Hansen&Hoyt body, [

17], see

Figure 2), the mechanical power can be estimated as 38W. The corresponding human muscles power is higher, since only its part is transformed into mechanical power of the vehicle motion (in particular, some energy is wasted on the propeller). But if we change only pontoons, the obtained value 38W can be used to estimate the maximal speed of the improved water bike.

If we use two equal almost half-submerged pontoons of volume

V with the shape similar to one shown in

Figure 4 by the black solid line, then the wave resistance can be neglected for small values of depth, e.g.,

h/D<0.1, see

Figure 3 and

Figure 5. The total drag of the improved water bike can be estimated as a friction drag on a single underwater hull of the same volume

V.

For subcritical Reynolds numbers, the volumetric drag coefficient of the vehicle can be estimated with the use of formula (1). Then eq. (10) allows calculating its maximal speed at given value of mechanical power as follows:

Formula (11) yields the maximal speed of 3.8 m/s for the improved water bike with the same mechanical power 38W and displacement V=0.24 m3 (the value m2/s was used for this estimation). Thus, the expected speed is almost 41% higher then for the prototype. Nevertheless, the maximal speed of 9 m/s estimated in previous Section for a laminar vehicle cannot be achieved with the use of human power only. On the other hand, an improved human muscle powered water bike of mass 1t can achieve the speed of 2.9 m/s. Thus, similar improved vehicles can be also used for transportation at rather high speeds.

Significant differences in speeds of the prototype and an improved water bike can be easily registered in tests, giving us an opportunity to estimate the efficiency of new pontoons. In the case of success, the new shapes can be recommended for rowing shells, small boats and ships with subcritical Reynolds numbers. The new shapes could be also very useful for larger and faster vehicles since their volumetric drag coefficients are much lower then for standard hulls even at supercritical Reynolds numbers (compare solid and dashed lines in

Figure 2).

Small drag on unseparated hulls allows increasing the commercial effectiveness (weight-to-drag ratio, [

24]). In particular, the dolphin–like underwater shapes can ensure the attached laminar flow at rather high Reynolds numbers [

25] and can be recommended for SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull) yachts and ferries [

13]. The small drag of floating hulls with a sharp nose similar to the shapes of fastest fish could improve the commercial efficiency of common ships for both sub- and supercritical Reynolds numbers.

To reduce the negative impact of emissions of carbon dioxide and toxic substances (which are critical in some areas [

26,

27]), the use of fossil fuels has to be stopped. Electric ships are already in operation [

28,

29], but there is some delay in electrification of the maritime transport (in comparison with cars and buses) connected with the higher drag in water. The low drag of the proposed hulls allows increasing the commercial efficiency of ships and range with the use of one charge.

Let us estimate the maximal speed and range of electrical vehicles with improved hulls using the power to weight ratio

PW and the operation time

T at given value of the power. The power to mass ratio for modern electrical accumulators ranges from 1.65 to 9706

W/kg, [

30]. Then corresponding power to weight ratios are between 0.17 and 990.4

W/N or m/s. The battery discharge time

T can range between 0.5 and 90,000 seconds, [

30].

Taken into account that only a part

of the accumulator power

Pa is used for a steady motion (with the required mechanical power

X) and that the weight of accumulators

gma is only a part

of a vehicle tonnage, the following formula is valid:

Equation (12) allows estimating the speed that can be achieved at given values of pW, km and kP as follows:

Taking into account Equations (1) and (3), the following estimations for the maximal velocity in the cases of the laminar and turbulent flows can be obtained:

If the ranges of

kP and

km are between 0.1 and 1.0, the

kt values are located between 0.15 and 12.6

.

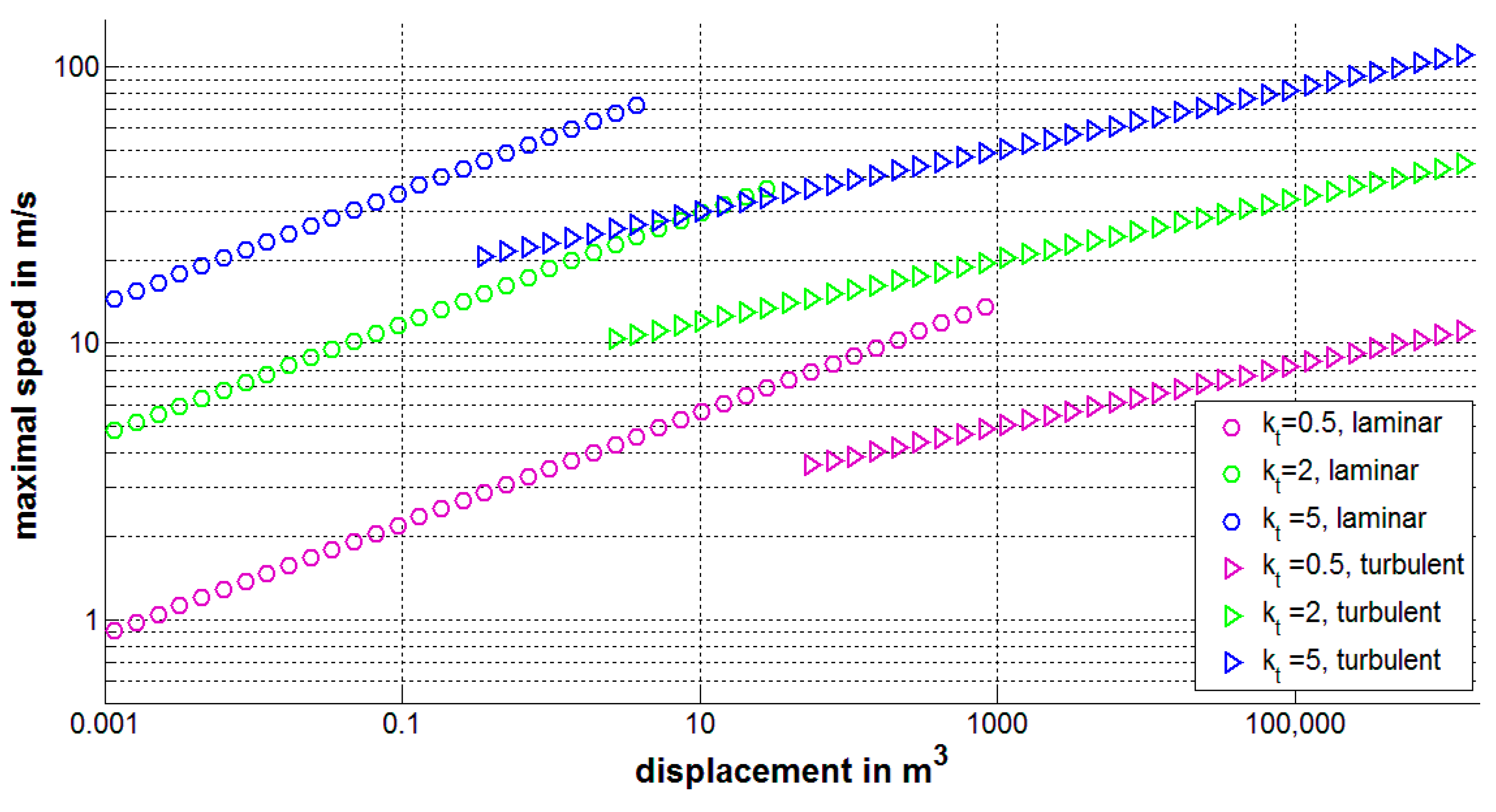

Figure 8 illustrates the relationships (14) at three different

kt values for laminar (“circles”) and turbulent (‘triangles”) hulls versus displacement

V. At high values of

kt rather high speeds of electrical vehicles are possible (especially for large values of the displacement, see blue markers in

Figure 8). Taking in (14) some average value

kt =1.0

, the maximum speed of the improved electrical water bike (with

V=0.24 m

3 ;

m

2/s) can be estimated as 6.1 m/s for the laminar case and 4.0 m/s for the turbulent one.

To estimate the range of the improved electrical water bike, it is enough to multiply values (14) by the battery discharge time

T. Then at the highest value of

T =90,000 sec the range of the laminar vehicle can be 549 km. This estimation looks too optimistic, since the batteries with high value of

kt (ensuring the highest speeds) have smaller discharging time, [

30].

5. Strength and materials limitations

Formulae (14) and

Figure 8 illustrate, that rather high speeds of electrical vehicles can be achieved at high values of the parameter k

t, especially for the laminar case. In the turbulent flow, the corresponding maximal speed is approximately twice lower. To achieve the highest speeds, special shaped very slender hulls must be used, which ensure the laminar attached flow. Unfortunately, the length and volume of such hulls are limited by critical Reynolds numbers (see formula (2)). The length to diameter ratio

L/D must be as high as possible to increase the critical Reynolds number. In particular, taking into account the formula

(where dimensionless coefficient

varies from 0.23 to 0.33 for

from 0.02 to 0.28 [

12,

18]), eq. (2) can be rewritten as follows:

The values of L/D range from 5 to 12 for the fastest fish allowing them have to have subcritical Reynolds numbers, a laminar flow pattern and a low drag. Modern materials and technologies make it possible to manufacture very elongated special shaped hulls. Probably, modern materials can ensure the values of

L/D higher than 33.3 (typical for the fish Largehead hairtail, [

2]) and critical values of the volumetric Reynolds number higher than 50 millions (according to eq. (16)).

6. Conclusions

Improved pontoon shapes can increase the speed and tonnage of water bikes using the human muscles and electrical power. If the calculated significant differences in speeds of the prototype and an improved water bike will be registered in tests, the new shapes can be recommended for rowing shells, small boats and ships and probably also for larger and faster vehicles.

Modern materials and technologies open wide prospects for these special shaped hulls in shipbuilding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.N., T.M.; methodology, S.K.; software, I.N.; validation, T.M.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, I.N., T.M.; resources, S.K., T.M.; data curation, I.N.; writing—original draft preparation, I.N.; writing—review and editing, S.K., T.M.; visualization, I.N.; supervision, S.K.; project administration, S.K.; funding acquisition, S.K., T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Oleksii Rodionov for his support and useful discussion of the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- https://hydrobikes.com/products/explorer-1.

- Yu. G Aleyev, Nekton, Dr. W. Junk, The Hague, 1977.

- Available online: https://www.thetravelalmanac.com/lists/fish-speed.htm (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Available online: https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/fastest-fish-in-the-world-1556626683-1 (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swordfish (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Nesteruk, FASTEST FISH SHAPES AND OPTIMAL SUPERCAVITATING AND HYPERSONIC BODIES OF REVOLUTION, Innov Biosyst Bioeng ( 2020) vol. 4, no. 4, 169–178. [CrossRef]

- I. Nesteruk. Shapes of the fastest fish and optimal underwater and floating hulls. Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.H. MICHELL, The wave resistance of a ship, Phil Mag(5),vol. 45 (1898)106-123.

- T. H. HAVELOCK, Wave patterns and wave resistance, Trans RINA, (1934) 430-442.

- E. O. TUCK, J. L. COLLINS and J.L. WELLS, On ship waves and their spectra, J Ship Res, (1971) 11-21.

- L. LAZAUSKAS and E. O. TUCK, Low drag multihulls for sporting, commercial and military applications, Fourth Int Conf on Fast SeaTransp (FAST97), (1997) 647-652, Baird Publications, Melbourne.

- I. Nesteruk. Maximal speed of underwater locomotion, Innov Biosyst Bioeng, 2019, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 152–167. [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk, S. Krile, Z. Koboevic. Electrical Swath Ships with Underwater Hulls Preventing the Boundary Layer Separation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2020, 8(9):652. 8(9). [CrossRef]

- Nesteruk. Rigid Bodies without Boundary-Layer Separation. Int. J. of Fluid Mechanics Research, 2014, vol. 41(3), pp. 260-281.

- Goldschmied, F.R. Integrated hull design, boundary layer control and propulsion of submerged bodies: Wind tunnel verification. In AIAA (82-1204), Proceedings of the AIAA/SAE/ASME 18th Joint Propulsion Conference, pp. 3–18, 1982.

- Greiner, L., editor. Underwater missile propulsion. Compass Publications, 1967.

- R. J. Hansen and J. G. Hoyt, Laminar-To-Turbulent Transition on a Body of Revolution with an Extended Favorable Pressure Gradient Forebody, Journal of Fluids Engineering, Vol. 106 (1984) 202-210.

- I. Nesteruk, Efficiency of Steady Motion and its Improvement with the Use of Unseparated and Supercavitating Flow Patterns, Naukovi Visti NTUU KPI, (2016) No. 6, 51-67. [CrossRef]

- Hoerner, S.F. Fluid-dynamic drag. Midland Park, N.J. 1965.

- J. N. Newman, Applications of Slender-Body Theory in Ship Hydrodynamics, Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, Vol. 2, 67-94 (1970). [CrossRef]

- E. Boulougouris and A. Papanikolaou, Hull form optimization of a high-speed wave piercing monohull. Proc. 9th Int. Marine Design Conference-IMDC06, Ann Arbor - Michigan. January 2006. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259976812_Hull_form_optimization_of_a_high-speed_wave_piercing_monohull.

- C. Wei, Y. Li, S. Yu et al. Experimental study on the high speed mono-wave-piercing boat [J]. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science) (2016) 21(5): 524–529.

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulbous_bow (accessed on 19 October 2022).

- Gabrielly, Y. & von Karman, Th. What price speed. Mechanical Engineering. USA. Vol. 72. No. 10, 1950. P. 775-779.

- I. Nesteruk, M. I. Nesteruk, M. Brühl, Th. Möller. Testing a special shaped body of revolution similar to dolphins trunk, KPI Science News, No. 2, 2018, pp.44-53. [CrossRef]

- Michael Le Page. France and others plan to tackle air pollution in Mediterranean sea. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2191427-france-and-others-plan-to-tackle-air-pollution-in-mediterranean-sea/.

- Croatia country briefing - The European environment — state and outlook 2015. https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer-2015/countries/croatia.

- Fred Lambert. All-electric ferry cuts emission by 95% and costs by 80%, brings in 53 additional orders. Feb. 3rd 2018. https://electrek.co/2018/02/03/all-electric-ferry-cuts-emission-cost/.

- Fred Lambert. A new all-electric cargo ship with a massive 2.4 MWh battery pack launches in China. Dec. 4th 2017. https://electrek.co/2017/12/04/all-electric-cargo-ship-battery-china/.

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power-to-weight_ratio#Electrochemical_(galvanic)_and_electrostatic_cell_systems (accessed on 9 May 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).