Submitted:

03 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminary Work

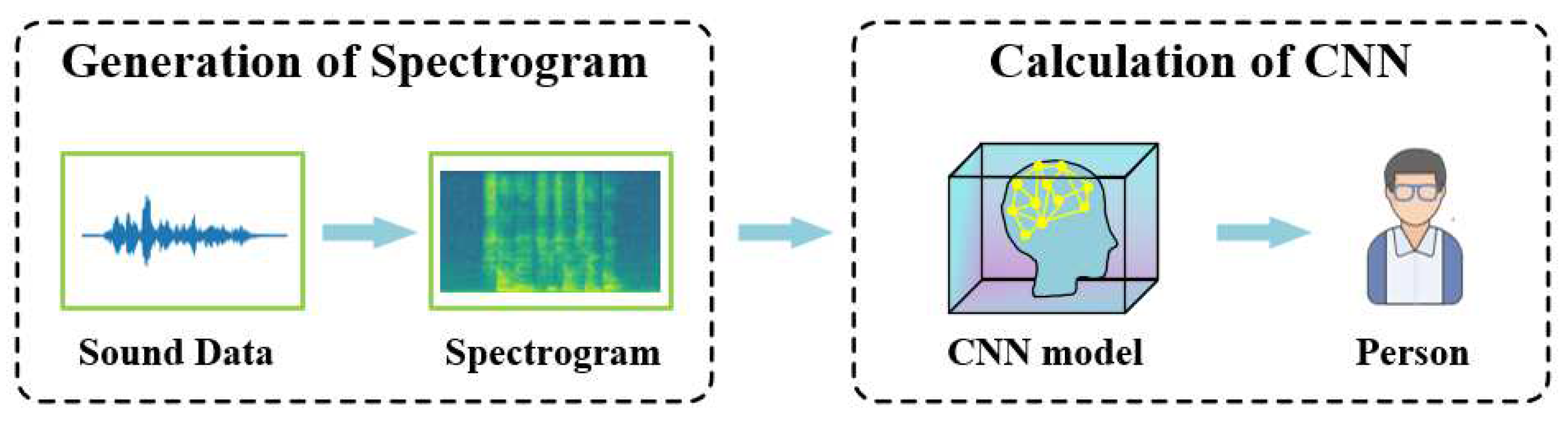

2.1. Speaker Recognition in CNN

2.2. Generation of Spectrogram

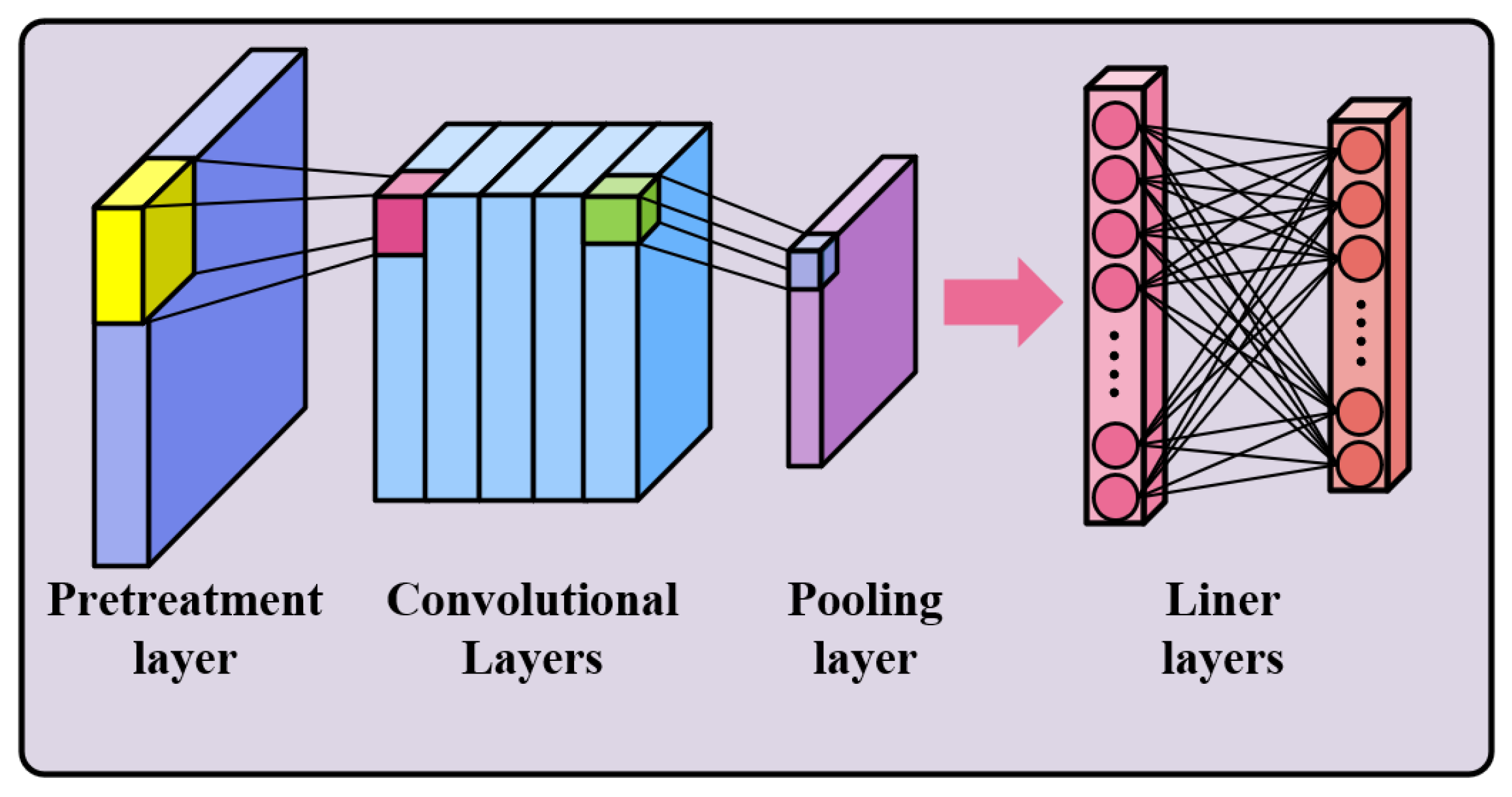

2.3. CNN Architecture

- The number of filters per convolution layer: this parameter determines the abstraction ability of the network and the number of features to be extracted eventually;

- The number of neurons in the fully connected layer: too few neurons may result in failure to train a model that meets the requirements, while numerous neurons may lead to overfitting;

- Learning rate: if the learning rate is too low, it is easy for the model to fall into a local optimum, and if it is too high, it is easy to miss the global optimum and fail to complete the training.

3. Proposed Approaches

3.1. Resnet

3.2. DBO

3.3. Optimization Process

- Step I, divide the data set into a training set and a test set in a ratio of about 8:2;

- Step II, initialize the population and divide it into different beetle roles according to the fitness ranking. Among them, ball-rolling beetles accounts for 6/30, brood balls accounts for 6/30, small beetles accounts for 7/30 and thief beetles accounts for 11/30;

- Step III, the beetles search for the optimal hyperparameter group according to their own strategies of position adjustment;

- Step IV, build a convolutional neural network for speaker recognition by using the optimal hyperparameters;

- Step V, evaluate the model on the test set after training.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Hyperparameters Optimization

4.3. Model Training

4.4. Noise Resistance Test

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, H.; Gupta, D. LPC and LPCC method of feature extraction in Speech Recognition System. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference - Cloud System and Big Data Engineering (Confluence), Noida, India, 14-15 January 2016; pp. 498-502. [CrossRef].

- Chia Ai, O.; Hariharan, M.; Yaacob, S.;Sin Chee, L. Classification of speech dysfluencies with MFCC and LPCC features. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 2157-65. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Singh, U.; Bansal, G.; Gupta, R.; Singh, A.K. A Review on Emotion Detection and Classification using Speech. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Computing & Communications (ICICC) 2020, New Delhi, India, 21-23 February 2020. [CrossRef].

- Tiwari, V. MFCC and its applications in speaker recognition. International journal on emerging technologies 2010, 1, 19-22. [CrossRef].

- Bhadragiri, J. M.; Ramesh, B. N. Speech recognition using MFCC and DTW. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Electrical Engineering (ICAEE), Vellore, India, 9-11 January 2014; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef].

- Nakagawa, S.; Zhang, W.; Takahashi,M. Text-independent speaker recognition by combining speaker-specific GMM with speaker adapted syllable-based HMM. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Montreal, QC, Canada, 30 August 2004; pp. I-81. [CrossRef].

- Matsui, T.; Kanno,T.; Furui,S. Speaker recognition using HMM composition in noisy environments. Computer Speech & Language 1996, 10, 107-116. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Limkar, M.; Rao,B.R.; Sagvekar, V. Speaker Recognition using VQ and DTW. International Journal of Computer Applications 2012, 3, 975-8887. [CrossRef].

- Keogh, E.; Ratanamahatana, C.A. Exact indexing of dynamic time warping. Knowledge and Information Systems 2005, 7, 358-386. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Shuwu, Z.; Bo, X. Text-independent speaker identification using GMM-UBM and frame level likelihood normalization. In Proceedings of the 2004 International Symposium on Chinese Spoken Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, 15-18 December 2004; pp. 289-292. [CrossRef].

- Liu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, T.; Li, J.; Shen, C. GMM and CNN Hybrid Method for Short Utterance Speaker Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 14, 3244-3252. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.M.; Sturim, D.E.; Reynolds, D.A. Support vector machines using GMM supervectors for speaker verification. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2006, 13. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, B.; Du, J. Research on transformer fault voiceprint recognition based on Mel time-frequency spectrum-convolutional neural network. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2022, 2378, 12-89. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Ashar, A.; Bhatti, M.S.; Mushtaq,U. Speaker Identification Using a Hybrid CNN-MFCC Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Smart Technologies (ICETST), Karachi, Pakistan, 26-27 March 2020; pp. 1-4. [CrossRef].

- Chung, J.S.; Nagrani, A.; Zisserman, A. Voxceleb2: Deep speaker recognition. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.05622 [CrossRef].

- Jagiasi, R.; Ghosalkar, S.; Kulal, P.; Bharambe, A. CNN based speaker recognition in language and text-independent small scale system. In Proceedings of the 2019 Third International conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 12-14 December 2019; pp. 176-179. [CrossRef].

- Yoo, J.H.; Yoon,H.I.; Kim, H.G.; Yoon, H.S.; Han, S.S. Optimization of Hyper-parameter for CNN Model using Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st International Conference on Electrical, Control and Instrumentation Engineering (ICECIE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 25-25 November 2019; pp. 1-6. [CrossRef].

- Ishaq, A.; Asghar, S.; Gillani, S.A. Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis Using a Hybridized Approach Based on CNN and GA. IEEE Access 2020; 8, 135499-135512. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, J.; Guo, X.; Tan, L. A self-Adaptive CNN with PSO for bearing fault diagnosis. Systems Science & Control Engineering 2020, 9, 11-22. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneshwari, K.S.; Venkatachalam, K.; Hubálovský, S.; Trojovský P.; Prabu, P. Improved Dragonfly Optimizer for Intrusion Detection Using Deep Clustering CNN-PSO Classifier. Computers, Materials & Continua 2022, 70. [CrossRef].

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Advances in engineering software 2016, 95, 51-67. [CrossRef].

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Advances in engineering software 2014, 69, 46-61. [CrossRef].

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: sparrow search algorithm. Systems science & control engineering 2020, 8, 22-34. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Peraza-Vázquez, H.; Peña-Delgado, A.; Ranjan, P.; Barde, C.; Choubey, A.; Morales-Cepeda, A.B. A bio-inspired method for mathematical optimization inspired by arachnida salticidade. Mathematics 2021, 10, 102. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: a new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. The Journal of Supercomputing 2023, 79, 7305-7336. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, H.; Feng, S.; Zhu, H. How to measure adaptation complexity in evolvable systems–A new synthetic approach of constructing fitness functions. Expert Systems with Applications 2011, 38, 10414-10419. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Reilly, N.; Arena1, S.; Lamba, S.; Bartolini, A.; Amodio, V.; Magrì, A.; Novara, L.; Sarotto, I.; Nagel, Z.D.; Piett, C.G.; Amatu, A.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Siena, S.; Bertotti, A.; Trusolino, L.; Corigliano, M.; Gherardi, M.; Lagomarsino, M.C.; Nicolantonio, F.D.; Bardelli, A. Adaptive mutability of colorectal cancers in response to targeted therapies. Science 2019, 366, 1473-1480. [CrossRef]. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yin, H.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Kern, C.; Halstead, M.; Chanthavixay, G.; Trakooljul, N.; Wimmers, K. Sahana, G.; Su, G.; Lund, M.S.; Fredholm, M.; Karlskov-Mortensen, P.; Ernst, C.W.; Ross, P.; Tuggle, C.K..; Fang, L.; Zhou, H. Pig genome functional annotation enhances the biological interpretation of complex traits and human disease. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5848. [CrossRef].

| Layer | Range |

|---|---|

| residual block 1 | 16~32 |

| residual block 2 | 32~64 |

| residual block 3 | 64~128 |

| residual block 4 | 128~256 |

| residual block 5 | 256~512 |

| residual block 1 | 512~1024 |

| linear layer 1 | 256~512 |

| linear layer 2 | 64~128 |

| learning rate | 1e2~1e-3 |

| Layer | CNN | PSO-CNN | SSA-CNN | DBO-CNN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| residual block 1 | 32 | 24 | 27 | 21 |

| residual block 2 | 64 | 32 | 54 | 63 |

| residual block 3 | 128 | 117 | 107 | 71 |

| residual block 4 | 256 | 230 | 143 | 256 |

| residual block 5 | 512 | 386 | 424 | 272 |

| linear layer 1 | 1024 | 424 | 904 | 653 |

| linear layer 2 | 512 | 272 | 394 | 259 |

| learning rate | 1e-2 | 1e-3 | 1e-3 | 1e-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).