Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Screening

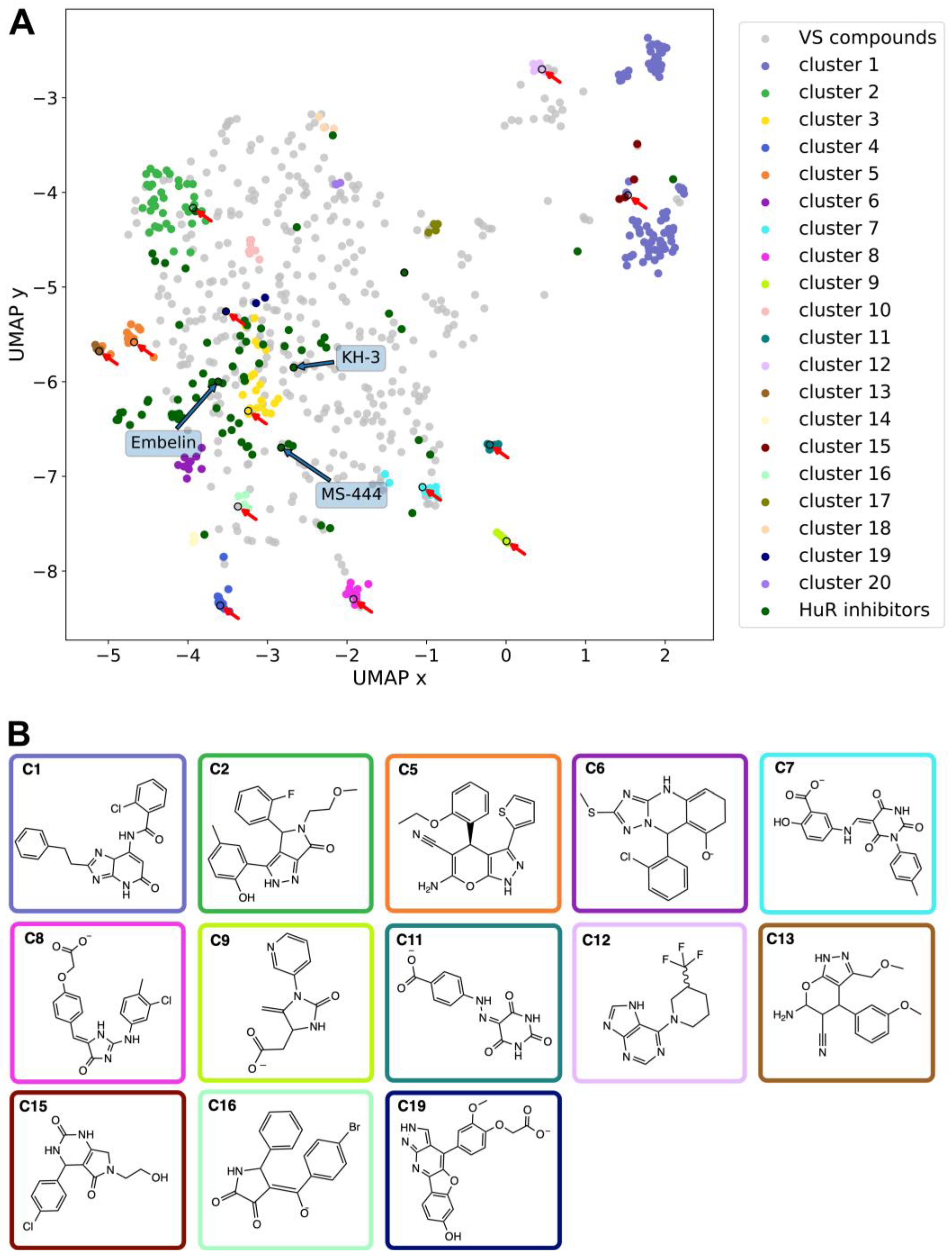

2.2. Comparison with the chemical space of the existing ligands

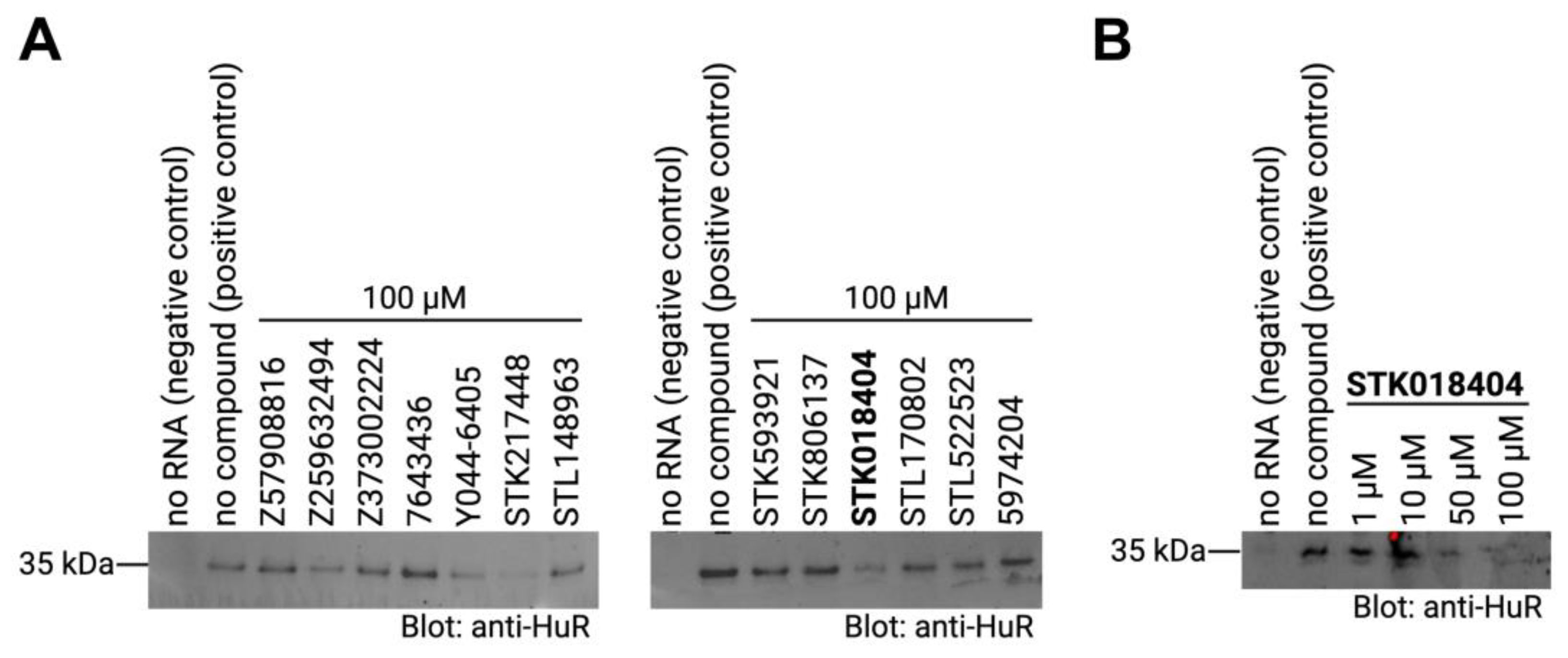

2.3. Experimental test

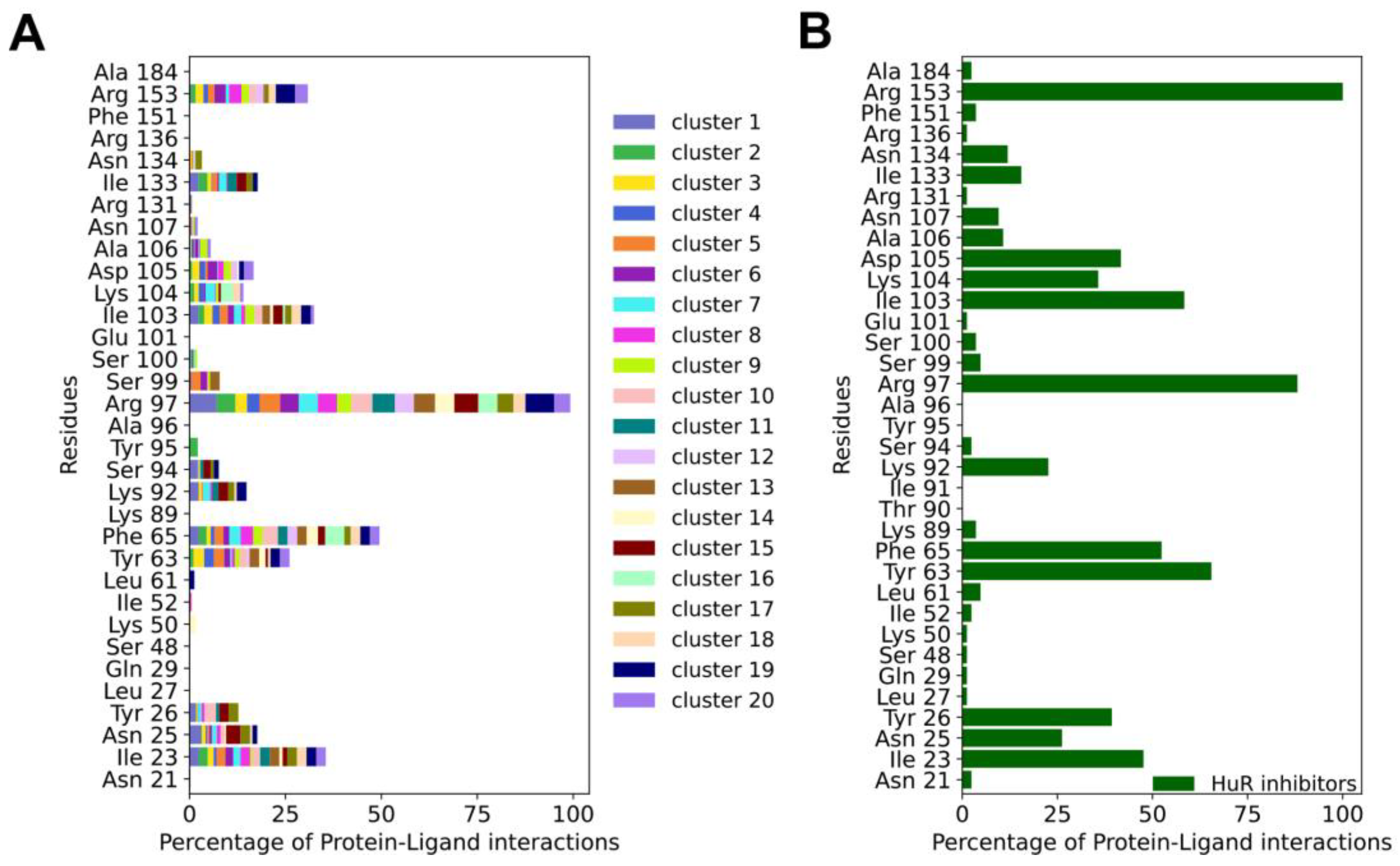

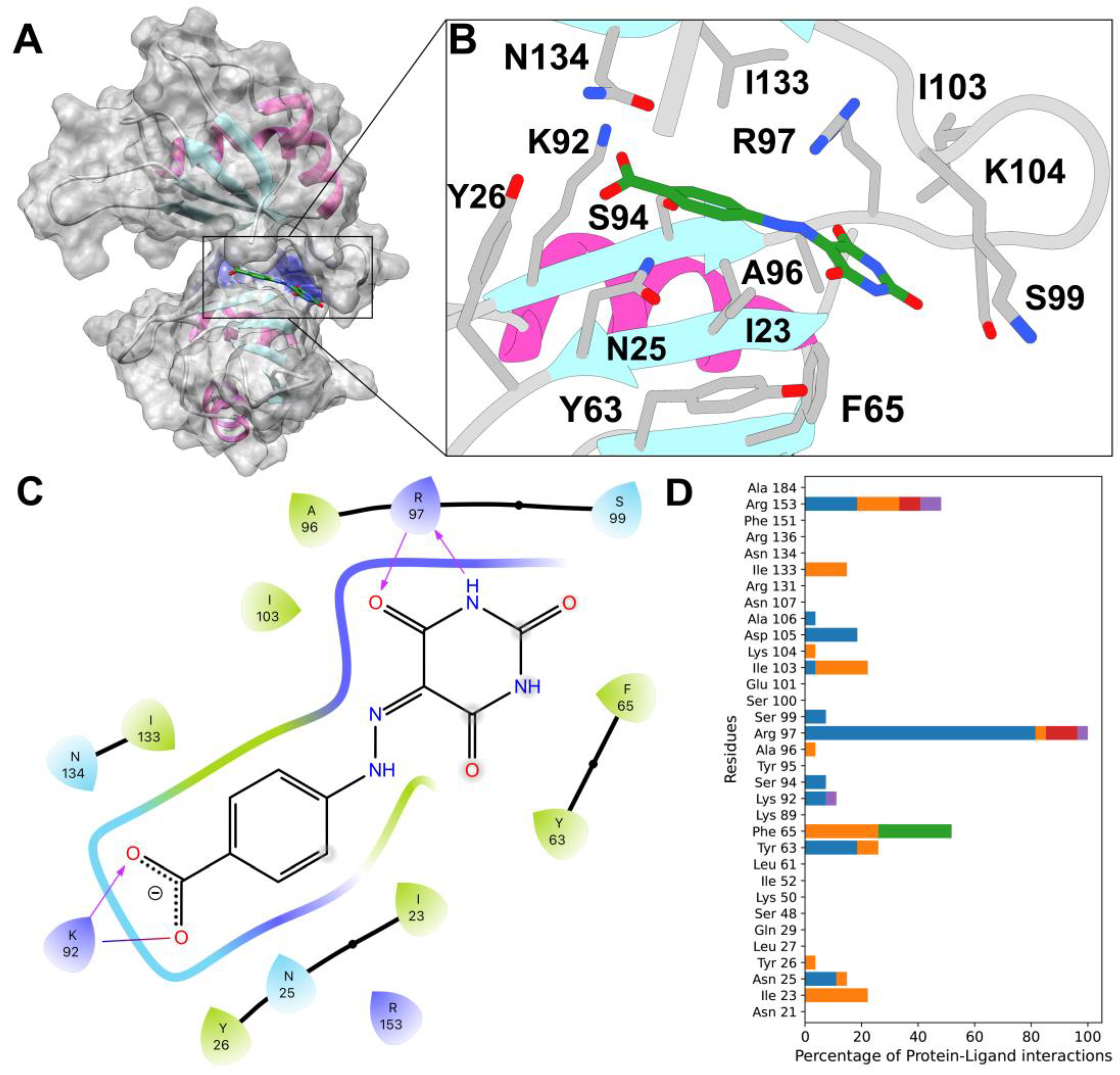

2.4. Docking and Fingerprints

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Methods: RNA pull-down

4.2. Computational Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glisovic, T.; Bachorik, J.L.; Yong, J.; Dreyfuss, G. RNA-Binding Proteins and Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingh, J. The Many Facets of RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 25, 684–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Ceriani, M.C.; Capaccioli, S.; Nicolin, A. Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Gene Expression by Degradation of Messenger RNAs. J. Cell. Physiol. 2003, 195, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Ye, X.; Vishwakarma, V.; Preet, R.; Dixon, D.A. CRC-Derived Exosomes Containing the RNA Binding Protein HuR Promote Lung Cell Proliferation by Stabilizing c-Myc MRNA. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2022, 23, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Peña, J.B.; Campbell, Z.T. RNA-Binding Proteins as Targets for Pain Therapeutics. Transl. Regul. Pain 2018, 4, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunder, N.; de la Peña, J.B.; Lou, T.-F.; Chase, R.; Suresh, P.; Lawson, J.; Shukla, T.; Black, B.J.; Campbell, Z.T. The RNA-Binding Protein HuR Is Integral to the Function of Nociceptors in Mice and Humans. J. Neurosci. 2022, JN-RM-1630-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, D.A.; Tolley, N.D.; King, P.H.; Nabors, L.B.; McIntyre, T.M.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Prescott, S.M. Altered Expression of the MRNA Stability Factor HuR Promotes Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression in Colon Cancer Cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2001, 108, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Fang, X.; Yao, H.; Gong, C. Novel Roles of RNA-Binding Proteins in Drug Resistance of Breast Cancer: From Molecular Biology to Targeting Therapeutics. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetter, C.; Licata, L.A.; Costantino, C.L.; Witkiewicz, A.; Yeo, C.; Brody, J.R.; Keen, J.C. Cytoplasmic Accumulation of the RNA Binding Protein HuR Is Central to Tamoxifen Resistance in Estrogen Receptor Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1496–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gardashova, G.; Lan, L.; Han, S.; Zhong, C.; Marquez, R.T.; Wei, L.; Wood, S.; Roy, S.; Gowthaman, R.; Karanicolas, J.; Gao, F.P.; Dixon, D.A.; Welch, D.R.; Li, L.; Ji, M.; Aubé, J.; Xu, L. Targeting the Interaction between RNA-Binding Protein HuR and FOXQ1 Suppresses Breast Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional Regulation of Cancer Traits by HuR. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2010, 1, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antic, D.; Lu, N.; Keene, J.D. ELAV Tumor Antigen, Hel-N1, Increases Translation of Neurofilament M MRNA and Induces Formation of Neurites in Human Teratocarcinoma Cells. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgonetti, V.; Coppi, E.; Galeotti, N. Targeting the RNA-Binding Protein HuR as Potential Thera-Peutic Approach for Neurological Disorders: Focus on Amyo-Trophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Spinal Muscle Atrophy (SMA) and Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeussler, J.; Haeusler, J.; Striebel, A.M.; Assum, G.; Vogel, W.; Furneaux, H.; Krone, W. Tumor Antigen HuR Binds Specifically to One of Five Protein-Binding Segments in the 3′-Untranslated Region of the Neurofibromin Messenger RNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 267, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Zheng, L.; Viera, L.; Suswam, E.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Estévez, A.G.; King, P.H. Mutant Cu/Zn-Superoxide Dismutase Associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Destabilizes Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor MRNA and Downregulates Its Expression. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 7929–7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, L.; Bush, D.J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, L.; Suswam, E.A.; King, P.H. Mutant Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase Associated with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Binds to Adenine/Uridine-Rich Stability Elements in the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor 3′-Untranslated Region. J. Neurochem. 2009, 108, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jarujaron, S.; Gurley, E.C.; Chen, L.; Ding, H.; Studer, E.; Pandak, W.M.; Hu, W.; Zou, T.; Wang, J.-Y.; Hylemon, P.B. HIV Protease Inhibitors Increase TNF-α and IL-6 Expression in Macrophages: Involvement of the RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Atherosclerosis 2007, 195, e134–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Jang, B.-C.; Wu, M.-T.; Paik, J.-H.; Furneaux, H.; Hla, T. The RNA-Binding Protein HuR Regulates the Expression of Cyclooxygenase-2 *. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 25227–25233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cok, S.J.; Acton, S.J.; Morrison, A.R. The Proximal Region of the 3′-Untranslated Region of Cyclooxygenase-2 Is Recognized by a Multimeric Protein Complex Containing HuR, TIA-1, TIAR, and the Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein U *. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36157–36162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, P.; Cerofolini, L.; D’Agostino, V.G.; Zucal, C.; Fuccio, C.; Bonomo, I.; Dassi, E.; Giuntini, S.; Di Maio, D.; Vishwakarma, V.; Preet, R.; Williams, S.N.; Fairlamb, M.S.; Munk, R.; Lehrmann, E.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Elezgarai, S.R.; Luchinat, C.; Novellino, E.; Quattrone, A.; Biasini, E.; Manzoni, L.; Gorospe, M.; Dixon, D.A.; Seneci, P.; Marinelli, L.; Fragai, M.; Provenzani, A. Regulation of HuR Structure and Function by Dihydrotanshinone-I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 9514–9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Volpe, S.; Nasti, R.; Queirolo, M.; Unver, M.Y.; Jumde, V.K.; Dömling, A.; Vasile, F.; Potenza, D.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Costa, G.; Alcaro, S.; Zucal, C.; Provenzani, A.; Di Giacomo, M.; Rossi, D.; Hirsch, A.K.H.; Collina, S. Novel Compounds Targeting the RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Structure-Based Design, Synthesis, and Interaction Studies. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P. Inhibition of RNA-Binding Proteins with Small Molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, L.; Zucal, C.; Maio, D.D.; D’Agostino, V.G.; Thongon, N.; Bonomo, I.; Lal, P.; Miceli, M.; Baj, V.; Brambilla, M.; Cerofolini, L.; Elezgarai, S.; Biasini, E.; Luchinat, C.; Novellino, E.; Fragai, M.; Marinelli, L.; Provenzani, A.; Seneci, P. Interfering with HuR–RNA Interaction: Design, Synthesis and Biological Characterization of Tanshinone Mimics as Novel, Effective HuR Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasti, R.; Rossi, D.; Amadio, M.; Pascale, A.; Unver, M.Y.; Hirsch, A.K.H.; Collina, S. Compounds Interfering with Embryonic Lethal Abnormal Vision (ELAV) Protein–RNA Complexes: An Avenue for Discovering New Drugs: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 8257–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.-J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, D.-X.; Zhang, X.-Y. Potentialities and Challenges of MRNA Vaccine in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 923647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.-J.; Jeong, K.-C.; Chae, M.-J.; Kim, S.-Y.; Park, W.-Y. Flavonoids Inhibit the AU-Rich Element Binding of HuC. BMB Rep. 2009, 42, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lan, L.; Wilson, D.M.; Marquez, R.T.; Tsao, W.; Gao, P.; Roy, A.; Turner, B.A.; McDonald, P.; Tunge, J.A.; Rogers, S.A.; Dixon, D.A.; Aubé, J.; Xu, L. Identification and Validation of Novel Small Molecule Disruptors of HuR-MRNA Interaction. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bhattacharya, A.; Ivanov, D.N. Identification of Small-Molecule Inhibitors of the HuR/RNA Interaction Using a Fluorescence Polarization Screening Assay Followed by NMR Validation. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0138780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner, N.-C.; Hintersteiner, M.; Mueller, K.; Bauer, R.; Seifert, J.-M.; Naegeli, H.-U.; Ottl, J.; Oberer, L.; Guenat, C.; Moss, S.; Harrer, N.; Woisetschlaeger, M.; Buehler, C.; Uhl, V.; Auer, M. Identification and Mechanistic Characterization of Low-Molecular-Weight Inhibitors for HuR. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julio, A.R.; Backus, K.M. New Approaches to Target RNA Binding Proteins. Gener. Ther. 2021, 62, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Jiao, H.; Teng, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Hebbard, L.; George, J.; Qiao, L. Embelin Reduces Colitis-Associated Tumorigenesis through Limiting IL-6/STAT3 Signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 1206–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Triptolide Inhibits COX-2 Expression by Regulating MRNA Stability in TNF-α-Treated A549 Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 416, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutka, S.C.; Yang, W.Q.; Dong, S.D.; Ward, S.L.; Craig, D.A.; Timmermans, P.B.M.W.M.; Murli, S. Identification of Nuclear Export Inhibitors with Potent Anticancer Activity In Vivo. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hing, Z.A.; Mantel, R.; Beckwith, K.A.; Guinn, D.; Williams, E.; Smith, L.L.; Williams, K.; Johnson, A.J.; Lehman, A.M.; Byrd, J.C.; Woyach, J.A.; Lapalombella, R. Selinexor Is Effective in Acquired Resistance to Ibrutinib and Synergizes with Ibrutinib in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 3128–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ramesh, R.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Armaly, A.M.; Wei, L.; Xing, M.; Roy, S.; Lan, L.; Gao, F.P.; Miao, Y.; Xu, L.; Aubé, J. Small Molecules Targeting the RNA-Binding Protein HuR Inhibit Tumor Growth in Xenografts. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 2032–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuguchi, W.; Nomura, T.; Kitamura, T.; Otsuguro, S.; Matsushita, K.; Sakaitani, M.; Maenaka, K.; Tei, K. Suramin, Screened from an Approved Drug Library, Inhibits HuR Functions and Attenuates Malignant Phenotype of Oral Cancer Cells. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 6269–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, V.G.; Adami, V.; Provenzani, A. A Novel High Throughput Biochemical Assay to Evaluate the HuR Protein-RNA Complex Formation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, V.G.; Lal, P.; Mantelli, B.; Tiedje, C.; Zucal, C.; Thongon, N.; Gaestel, M.; Latorre, E.; Marinelli, L.; Seneci, P.; Amadio, M.; Provenzani, A. Dihydrotanshinone-I Interferes with the RNA-Binding Activity of HuR Affecting Its Post-Transcriptional Function. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, F.F.; Preet, R.; Aguado, A.; Vishwakarma, V.; Stevens, L.E.; Vyas, A.; Padhye, S.; Xu, L.; Weir, S.J.; Anant, S.; Meisner-Kober, N.; Brody, J.R.; Dixon, D.A. Impact of HuR Inhibition by the Small Molecule MS-444 on Colorectal Cancer Cell Tumorigenesis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 74043–74058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Berry, D.; Passecker, K.; Mesteri, I.; Bhuju, S.; Ebner, F.; Sedlyarov, V.; Evstatiev, R.; Dammann, K.; Loy, A.; Kuzyk, O.; Kovarik, P.; Khare, V.; Beibel, M.; Roma, G.; Meisner-Kober, N.; Gasche, C. HuR Small-Molecule Inhibitor Elicits Differential Effects in Adenomatosis Polyposis and Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2424–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doller, A.; Huwiler, A.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Eberhardt, W. Protein Kinase C␣-Dependent Phosphorylation of the MRNA-Stabilizing Factor HuR: Implications for Posttranscriptional Regulation of Cyclooxygenase-2. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, K.; Oubridge, C.; Jessen, T.H.; Li, J.; Evans, P.R. Crystal Structure of the RNA-Binding Domain of the U1 Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A. Nature 1990, 348, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.C.; Steitz, J.A. HNS, a Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Shuttling Sequence in HuR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 15293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

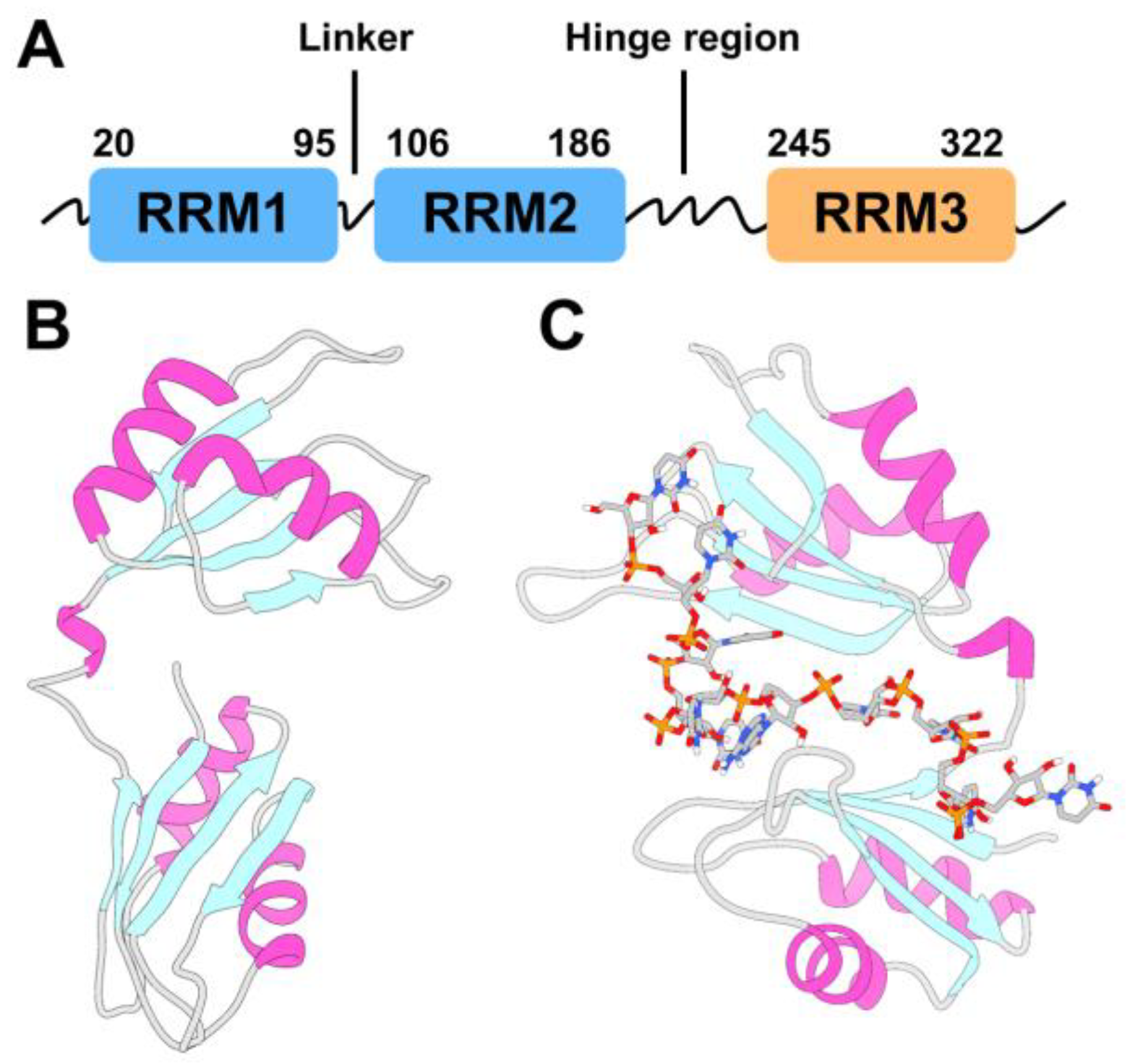

- Wang, H.; Zeng, F.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; Niu, L.; Teng, M.; Li, X. The Structure of the ARE-Binding Domains of Hu Antigen R (HuR) Undergoes Conformational Changes during RNA Binding. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabis, M.; Popowicz, G.M.; Stehle, R.; Fernández-Ramos, D.; Asami, S.; Warner, L.; García-Mauriño, S.M.; Schlundt, A.; Martínez-Chantar, M.L.; Díaz-Moreno, I.; Sattler, M. HuR Biological Function Involves RRM3-Mediated Dimerization and RNA Binding by All Three RRMs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripin, N.; Boudet, J.; Duszczyk, M.M.; Hinniger, A.; Faller, M.; Krepl, M.; Gadi, A.; Schneider, R.J.; Šponer, J.; Meisner-Kober, N.C.; Allain, F.H.-T. Molecular Basis for AU-Rich Element Recognition and Dimerization by the HuR C-Terminal RRM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, N.; Yang, X.; Ananthan, S.; Sorochinsky, A.; Hackney, J.R.; Gentry, Z.; Bae, S.; King, P.; Nabors, L.B. Hu Antigen R (HuR) Multimerization Contributes to Glioma Disease Progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 16999–17010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Yabukarski, F.; Biel, J.T.; Pinney, M.M.; Doukov, T.; Powers, A.S.; Fraser, J.S.; Herschlag, D. Assessment of Enzyme Active Site Positioning and Tests of Catalytic Mechanisms through X-Ray–Derived Conformational Ensembles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 33204–33215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, K.; Wu, X.; Fields, J.K.; Johnson, D.K.; Lan, L.; Pratt, M.; Somoza, A.D.; Wang, C.C.C.; Karanicolas, J.; Oakley, B.R.; Xu, L.; De Guzman, R.N. The Fungal Natural Product Azaphilone-9 Binds to HuR and Inhibits HuR-RNA Interaction in Vitro. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0175471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; Shaw, D.E.; Francis, P.; Shenkin, P.S. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Repasky, M.P.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Halgren, T.A.; Sanschagrin, P.C.; Mainz, D.T. Extra Precision Glide: Docking and Scoring Incorporating a Model of Hydrophobic Enclosure for Protein−Ligand Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6177–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butina, D. Unsupervised Data Base Clustering Based on Daylight’s Fingerprint and Tanimoto Similarity: A Fast and Automated Way To Cluster Small and Large Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1999, 39, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajusz, D.; Rácz, A.; Héberger, K. Why Is Tanimoto Index an Appropriate Choice for Fingerprint-Based Similarity Calculations? J. Cheminformatics 2015, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv September 17, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.03426 (accessed 2023-06-21).

- Vasile, F.; Della Volpe, S.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Costa, G.; Unver, M.Y.; Zucal, C.; Rossi, D.; Martino, E.; Provenzani, A.; Hirsch, A.K.H.; Alcaro, S.; Potenza, D.; Collina, S. Exploration of Ligand Binding Modes towards the Identification of Compounds Targeting HuR: A Combined STD-NMR and Molecular Modelling Approach. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, C.W.; Preet, R.; Dhir, T.; Dixon, D.A.; Brody, J.R. Understanding and Targeting the Disease-Related RNA Binding Protein Human Antigen R (HuR). WIREs RNA 2020, 11, e1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, J.R.; Calkins, D.; Sullivan, A.P.; Shelley, J.C. Towards the Comprehensive, Rapid, and Accurate Prediction of the Favorable Tautomeric States of Drug-like Molecules in Aqueous Solution. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2010, 24, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M. Epik: A Software Program for PKaprediction and Protonation State Generation for Drug-like Molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, E.; Damm, W.; Maple, J.; Wu, C.; Reboul, M.; Xiang, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Lupyan, D.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Knight, J.L.; Kaus, J.W.; Cerutti, D.S.; Krilov, G.; Jorgensen, W.L.; Abel, R.; Friesner, R.A. OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit. [CrossRef]

- Salentin, S.; Schreiber, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Adasme, M.F.; Schroeder, M. PLIP: Fully Automated Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W443–W447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-C.; Liou, J.-P.; Kuo, C.-C.; Lai, W.-Y.; Shih, K.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Pan, W.-Y.; Tseng, J.T.; Chang, J.-Y. MPT0B098, a Novel Microtubule Inhibitor That Destabilizes the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α MRNA through Decreasing Nuclear–Cytoplasmic Translocation of RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Chung, T.-W.; Choi, H.-J.; Lee, C.H.; Eun, J.S.; Han, Y.T.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-Y.; Han, C.-W.; Jeong, H.-S.; Ha, K.-T. A Novel Cantharidin Analog N-Benzylcantharidinamide Reduces the Expression of MMP-9 and Invasive Potentials of Hep3B via Inhibiting Cytosolic Translocation of HuR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 447, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doller, A.; Badawi, A.; Schmid, T.; Brauß, T.; Pleli, T.; Zu Heringdorf, D.M.; Piiper, A.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Eberhardt, W. The Cytoskeletal Inhibitors Latrunculin A and Blebbistatin Exert Antitumorigenic Properties in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Interfering with Intracellular HuR Trafficking. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 330, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, M.-J.; Sung, H.Y.; Kim, E.-H.; Lee, M.; Kwak, H.; Chae, C.H.; Kim, S.; Park, W.-Y. Chemical Inhibitors Destabilize HuR Binding to the AU-Rich Element of TNF-α MRNA. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009, 41, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).