1. Introduction

The international community has increased the proportion of renewable energy to realize decarbonization. However, long-term power use is unstable because a continuous and constant energy supply is unstable owing to the production environment variables. To address this problem, research has been conducted on methods to convert the surplus power produced with renewable energy into hydrogen energy for storage using power-to-gas technology, indicating the conversion of the energy type [

1]. Drawing is useful as a process to produce mechanical parts related to hydrogen energy in various fields because it can control mechanical properties through initial materials and the geometrical design of dies. Drawing is the process of increasing the longitudinal dimension and decreasing the lateral cross-sectional area by pulling the rod or pipe between dies. The die geometry is designed differently depending on the use purpose of the product. The products designed and manufactured by applying the drawing process to rods are used as they are usually. However, they are also processed into specific geometry through subsequent processes, such as bending or cutting, to be used as materials for fastening components, such as small pistons, structural members, shafts, spindles, bolts, and nuts. Wire products manufactured by applying the drawing process to wire materials are used for wiring in electrical and electronic devices, cables, springs, musical instruments, paper clips, fences, welding rods, and shopping carts [

2]. To apply the benefit of drawing those components of different geometries that can be manufactured through the conversion of mechanical properties, it is necessary first to design materials to secure product performance suitable for the hydrogen energy use environment. To select materials suitable for hydrogen energy, the arrangement of atoms that affects the behavior and performance of metals must be considered first. Metals are arranged in crystal forms during solidification to form a lattice structure. In this instance, their properties are determined by the arrangement of atoms. Metals form different lattice structures during solidification because the energy required to form each structure is minimized [

2]. Because the criteria to minimize the energy required to form the crystal structure may vary depending on the temperature or alloy composition ratio, materials must be selected considering the environment in which the product is used and the heat that may occur during the manufacturing process. In addition, different methods are applied depending on the product’s geometry, and changes in the mechanical properties of materials during processing affect the performance of the manufactured component. Therefore, to produce uniform products, research must be conducted first on cold processing criteria at room temperature for specific materials within the material standards in which the range of the element content is specified. In particular, severe hydrogen embrittlement occurs in high-strength steel. It reduces toughness or ductility by weakening the microstructural binding force of the metal material when hydrogen atoms penetrate the metal and involves delayed fracture in which sudden fracture occurs at a strength below the material’s ultimate tensile strength. It must be considered when materials are selected before the safety design of hydrogen energy-related mechanical components. Each manufacturer has different processing environment conditions for materials to be used during the manufacture of certain components. Therefore, the final lattice structure is inevitably different. Considering that this difference is severe in high-strength steel, an analysis of the correlation between the processing hardening phenomenon according to processing conditions and hydrogen embrittlement resistance according to the degree of residual stress during the rod drawing process can be required to control the mechanical properties of the primary processed product at the previous stage of the post-treatment process. Active movement of hydrogen atoms in metal is required for hydrogen to cause the embrittlement phenomenon by weakening the microstructural binding force of the metal. Because the face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice structure has lower hydrogen solubility than the body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice structure, the movement of hydrogen atoms is less active, and hydrogen embrittlement resistance is relatively high [

3]. SUS316, an austenitic metal with an FCC lattice structure, is mainly used as a material for mechanical components for hydrogen energy. It has high corrosion resistance to prevent rust on weld zones when materials are exposed to salt in the ocean [

4]. The critical hydrogen content and hydrogen embrittlement resistance of stainless steel also vary depending on the activity of the austenite phase in the metal. They can also be numerically expressed using the nickel equivalent equation according to the nickel content and nickel-based elements that activate the austenitic structure of the metal, as shown in Equation (1) [

5].

SUS316L is more suitable for hydrogen energy than SUS316 owing to the research result that hydrogen embrittlement resistance is improved as the carbon content decreases for SUS316L compared to SUS316 [

6]. Although SUS316L has lower price competitiveness than SUS304, which is the same austenitic stainless steel, SUS316L is considered appropriate for preventing hydrogen embrittlement because the carbon content of SUS304 is higher than that of SUS316L and molybdenum (Mo), an element related to embrittlement, is contained only in SUS316L [

7,

8]. To secure the price competitiveness of the selected material, it is necessary first to change its elemental composition ratio and design the mechanical component manufacturing process for higher performance. Second, the material and process need to be optimized considering the target performance and dimensional precision during the manufacture of products in each step. Consequently, research is required on technology that can control mechanical properties considered particularly important for fastening components among components for hydrogen energy, such as strength, ductility, and elongation.

Le Thanh Hung Nguyen et al. analyzed the change in the toughness of SUS316L by conducting the CVN impact test after charging hydrogen at room temperature and cryogenic temperature. They reported that SUS316L is suitable as a material that constitutes liquefied hydrogen containers [

9]. The absorbed energy required to fracture the specimen in a shock test from -196℃ to –25℃ range was smaller for lower temperatures. The toughness of SUS316L at -253℃, the boiling point of liquefied hydrogen, is expected to be lower. Considering that the largest hydrogen penetration occurred when the hydrogen charging time was 24h and that 12h of the hydrogen charging time caused little difference in absorbed energy despite the small amount of hydrogen charged, it is judged that the relationship between the amount of hydrogen charged and absorbed energy is not always constant and that the internal crystal structure of the hydrogen-charged specimen may affect the strength change.

Haruki Nishida et al. measured the mechanical properties of Fe-Cr-Ni-based austenitic alloys through a test in the pressurization conditions of hydrogen gas 11 and 100MPa. They analyzed the relationship between strength and ductility. In the test, SUS316L of nickel equivalent of 27.1 was used, and stacking fault energy (SFE) was presented as a factor that determines hydrogen embrittlement resistance along with nickel equivalent. In addition, the ultimate tensile strength of SUS316L tended to increase, and its elongation generally decreased as the hydrogen gas pressure increased [

10].

Lucas Renato Queiroga et al. studied the susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement according to the surface treatment of austenitic stainless steels and proved through tests that alloys with high nickel content have excellent hydrogen embrittlement resistance [

11]. The method of calculating hydrogen embrittlement sensitivity based on the gauge length that changes during the fracture of the specimen is judged to be different from the method based on the change in the cross-sectional area of the fracture specimen in terms of precision [

12].

Rong Jian Shi et al. conducted a tensile test after spreading hydrogen by the water electrolysis testing method. They used the concept of the hydrogen embrittlement index based on the change in elongation. They also compared the difference in microstructure in the cross-sectional areas of fracture specimens through a scanning electron microscope to evaluate hydrogen embrittlement resistance [

13].

However, no study evaluated hydrogen embrittlement resistance according to the drawing speed at room temperature and presented safety design standards for drawing products to determine initial rod-type materials and drawing process design standards in the pretreatment process to produce cut products for hydrogen energy. In this study, SUS316L, which is most commonly used as a material for hydrogen, was selected as the initial material on the premise that it is used immediately in the primary product condition or subjected to post-processing, such as cutting. Water electrolysis testing was conducted to identify the relationship between mechanical properties of materials and hydrogen embrittlement resistance. The mechanical properties of the selected material were evaluated by varying the tensile speed after charging hydrogen into the tensile specimens, and the difference was analyzed. The hydrogen charge was tested under environmental conditions with an error range of ±1°C at a temperature of 19°C and an error range of ±4% at a relative humidity of 38% R.H. In addition, a tensile test was conducted on SUS316L, which may have different mechanical properties depending on the processing environment, and material selection criteria were presented by examining the results. As a material selection criterion, the change in tensile strength, elongation, and reduction of area according to the hydrogen charge were analyzed to determine the change due to the effect of hydrogen embrittlement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

SUS316L, which contains elements as shown in

Table 1, was selected for the hydrogen embrittlement evaluation test. The initial geometry of the product was set to a round bar with a diameter of 16 mm. The nickel equivalent value of the selected material calculated using Equation (1) was 25.4548. It was designed to be close to the minimal element content for the composition ratio based on the standard of cold-processed alloy rods and manufactured considering the production cost [

14]. Cracks, which are the most important factor in designing metals for hydrogen energy use, are predicted by various engineering methods. In relation to cracks, an equation to obtain SFE was also used shown in

Table 1 to calculate SFE according to the composition ratio of SUS316L. SFE is an important parameter that affects austenite phase change properties similarly to nickel equivalent. Crystalline defects that can affect mechanical properties of the materials selected are less likely to occur as the SFE of the material increases.

Figure 1.

Round bars for hydrogen embrittlement test.

Figure 1.

Round bars for hydrogen embrittlement test.

Therefore, comparing nickel equivalent with SFE is essential in the preliminary analysis stage for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation. However, it is judged that many experiments will be required because the values of nickel equivalent and SFE vary depending on which equation is used.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Specimens Processing

Electrons move from cathode to anode when the current flows from anode to cathode. The cation hydrogen in the solution moves toward the electrons, resulting in reduction and combination as hydrogen gas when a specimen is placed at the end of the cathode of battery, and the specimen containing electrons is inserted in an aqueous solution. M10 standard rod specimens with a diameter of 6 mm were used to evenly distribute the effect of the hydrogen embrittlement caused by the hydrogen gas over the cross-sectional area of the specimen [

22,

23].

2.2.2. Hydrogen Charging Test

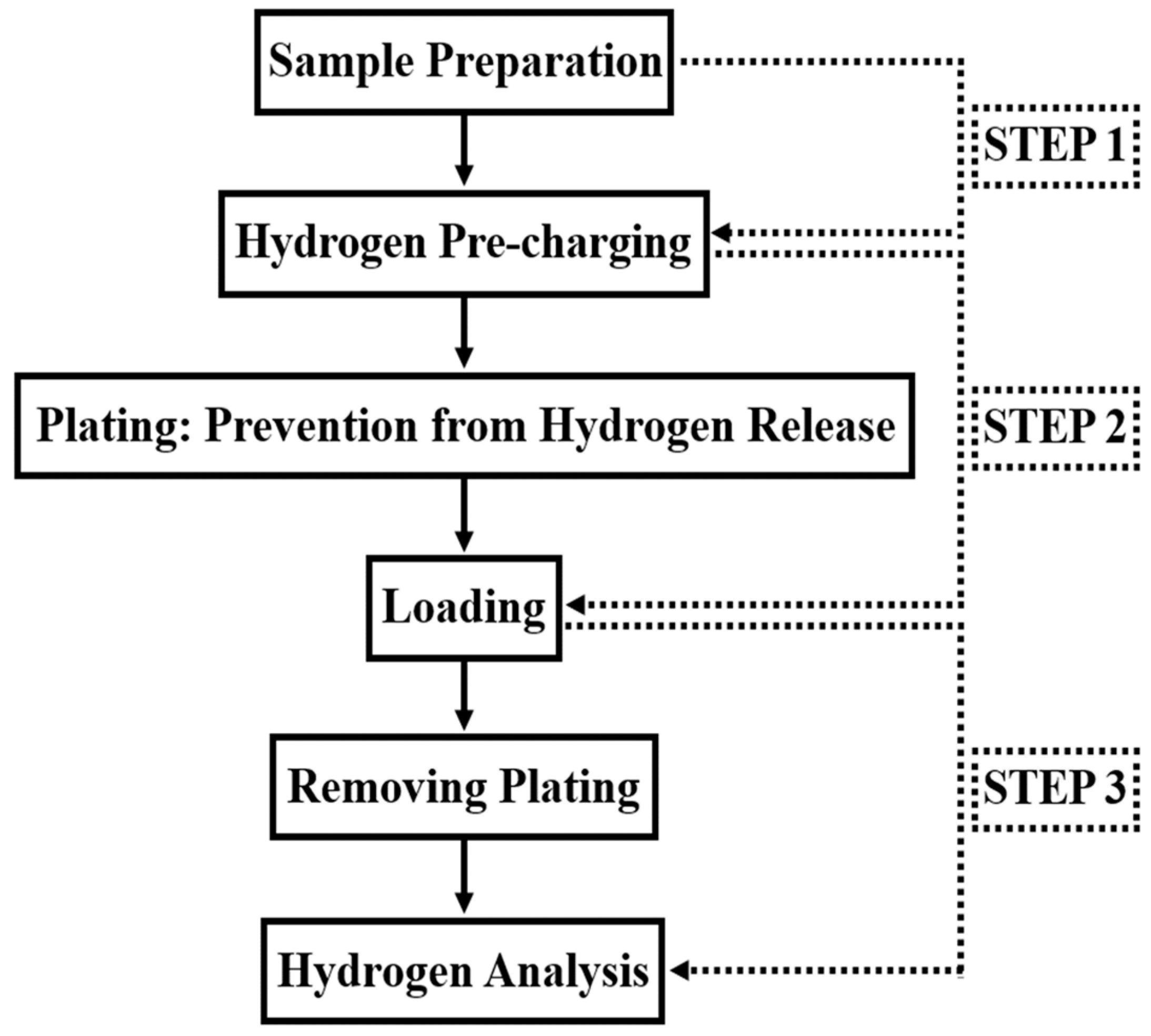

The ISO standard-based hydrogen pre-charging test shown in

Figure 2, used to evaluate hydrogen embrittlement resistance in high-strength steel, was used to penetrate hydrogen into the tensile specimens selected. Under the hydrogen charging test conditions, the plating process was excluded for in-depth analysis of factors that affect mechanical properties and the test was conducted as shown in

Figure 3 [

24]. NaCl and NH

4SCN, which can generate more hydrogen, were mixed at a 10:1 ratio for the electrolyte solution shown in

Table 2. Based on 1L of distilled water, a solution that mixed 30g of NaCl with 3g of NH

4SCN was prepared and used. The hydrogen penetration time of the specimens was set to 48h in accordance with the test standard. The test standard states that the current density should be set in the 0–20A/m

2 range. The purpose of this study, however, is to observe the embrittlement phenomenon according to the maximum amount of hydrogen charged rather than measuring the cross-sectional area of the specimen and setting the current density to 20A/m

2. Therefore, the current of the constant current supply device was set to 0.5A, and the test was conducted. The analysis began based on the hypothesis that applying a current density much higher than 20A/m

2 when a constant current of 0.5A flows in a specimen with a cross-section diameter of 6mm will make it easier to observe hydrogen embrittlement by maximizing hydrogen diffusion.

2.2.3. Thermal Desorption Mass Spectrometry Test

The penetration of hydrogen can be analyzed by applying thermal desorption mass spectroscopy for the specimen exposed to hydrogen gas for 48h in the hydrogen charging test. The residual amount of hydrogen gas according to the time of exposure to hydrogen gas must also be measured. Because this study mainly attempts to identify control design variables that secure hydrogen embrittlement resistance by applying a processing method without coating with specific metal elements, coating in the previous step or post-treatment to control coating was not introduced separately. The heating temperature was set to 400℃, and the heating rate, which does not significantly impact the test results, to 100℃, and the peak occurrence over time was observed. The hydrogen diffused in a particular metal was calculated by integrating the first peak of the thermal desorption analysis curve. The peak occurrence over time was then observed. If a hydrogen-dispersed specimen is placed inside a heating furnace under heating temperatures of 400℃, it is expected that the peak will be observed once. This is because the hydrogen that penetrated the surface and inside of the metal specimen is heated and measured simultaneously. If internal temperatures of the furnace increase from 0 to 400℃ over time with the heating rate set to 100℃, the first peak will be observed first as hydrogen that penetrates the surface is measured. After that, as the temperature rises, the second peak will be observed as hydrogen diffusing inside is measured. The pretreatment such as coating is required for prevent hydrogen diffusion in real time, and it is recommended to use a specimen based on the gauge length to measure the amount of diffusion compared to the uniform surface area. The presence of hydrogen that escapes from the specimen at room temperature is a variable that must also be considered during the experiment. In this study, only one peak was considered and compared with the tensile test results to measure the maximum amount of hydrogen diffused in SUS316L when hydrogen gas penetration was performed for 48h.

2.2.4. Tensile test

The tensile test measures the external force required for the plastic deformation of a specimen composed of specific materials. It is usually conducted to assess the properties of the materials through the flow stress curve. The main factors affecting flow stress include temperature, strain, and strain rate from the continuum mechanics perspective. Additional factors include the chemical composition, purity, crystal structure, phase composition, microstructure, particle size, and pre-strain of the material [

25]. Therefore, even if the phase composition and use environment conditions are considered, analyzing the change in flow stress depending on the temperature, strain, and strain rate is essential for the initial test setting in the future. We set the strain rate as an independent variable, and the mechanical property evaluation test results for fracture specimens were analyzed based on the flow curve after the specimens charged with hydrogen were subjected to tension at room temperature. The existing tensile test specimen size complied with “round tension test specimen 3” in the ASTM E8 standard for accurately measuring flow stress because there is still no clear standard for tensile test specimens for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation shown in Figure. 5.

Figure 5.

Slow strain rate tensile testing machine using hydrogen charging specimens.

Figure 5.

Slow strain rate tensile testing machine using hydrogen charging specimens.

This test is significant on such a design level because the strain rate at room temperature cannot significantly affect mechanical property evaluation and can rather be evaluated to be favorable in terms of the safety of the designed component. The deformation rate ranged from 2 to 10mm/min, which is the maximum rate of the tensile tester. In the case of cold processing, because the strain sensitivity index is low, the change in extreme tensile strength, which is usually proportional to the strain rate, is expected to be insignificant. This is also considered an important factor in calculating the range in terms of safety components and process design.

3. Results

3.1. Stress

The amount of average residual hydrogen in a specimen was measured through gas chromatography to be 1.8134ppm when one specimen was used, 1.7321ppm when four specimens were used. The test was conducted by setting six conditions, and the secured stress measurement results are shown in

Table 3. The tensile strength for specimens with no hydrogen penetration ranged from 721 to 734MPa. Because the gauge length that increased during fracture is 37mm when the tensile deformation rate is 10mm/min, the strain rate is 0.0045/s, which is obtained by dividing the tensile deformation rate by the gauge length of the specimen during fracture. A section with a strain rate of 0.1/s or less is referred to as a quasi-static strain rate section, and the 0.1 to 1,000/s range is defined as a medium strain rate section. Because there is time for heat to be sufficiently dissipated because of plastic deformation below the medium strain rate, it was assumed that there was no change in mechanical properties caused by heat generation. When the initial specimen was compared with the hydrogen-penetrated specimen, the tensile stress under a deformation rate of 10mm/min was 721MPa for the initial specimen, but 747MPa for the hydrogen-penetrated specimen, confirming that the strength was increased by hydrogen embrittlement. The yield strength was measured to be 500 and 646MPa, respectively, indicating that hydrogen embrittlement affects the mechanical properties of materials. In other words, more force is required to process SUS316L exposed to hydrogen. The safety of use is secured as long as a force larger than the tensile strength is applied during use. This is also an important factor to be considered in terms of design because the yield strength is increased and plastic deformation by external force does not easily occur.

Considering that there was a significant difference in yield strength depending on the penetration of hydrogen at a deformation rate of 10mm/min, the deformation rate was compared with 7.5, 3, and 2mm/min. There was no significant difference in tensile strength for the specimen before hydrogen penetration as the deformation rate decreased, but the yield strength tended to increase marginally . There was also no significant difference in tensile strength for the hydrogen-penetrated specimen. However, the yield strength was measured to be from 630 to 650MPa owing to hydrogen embrittlement, verifying that hydrogen penetration increased yield strength.

3.2. Elongation and Reduction of Area

The elongation and cross-section reduction rate are the most important results that must be analyzed when hydrogen embrittlement is evaluated using fracture specimens through the tensile test. The elongation is calculated by marking the gauge length on the specimen and measuring the increased gauge length. The cross-section reduction rate is calculated by measuring the diameter of the specimen before and after fracture. Hydrogen embrittlement can be evaluated based on elongation, but the cross-section reduction rate based on the fracture surface has a larger difference in the unit. Therefore, it is more precise to observe changes before and after hydrogen embrittlement through changes in cross-section reduction rate, as shown in

Figure 6. As the deformation rate increased, the elongation and cross-section reduction rate generally decreased. When the deformation rates were 2 and 10mm/min, the cross-section reduction rate was 84 and 78.22% for the specimen before hydrogen embrittlement and 79.75 and 76.63% for the specimen after hydrogen embrittlement. The difference in cross-section reduction rate is calculated to be 5.78% before hydrogen embrittlement and 3.12% after hydrogen embrittlement. It is considered the main reason for this is that the difference in yield strength according to the deformation rate and hydrogen permeation conditions affects the toughness of materials.

Figure 6.

The results on the fracture behavior characteristics according to the deformation rate of the forged SUS316L rod charged hydrogen through the water electrolysis test.

Figure 6.

The results on the fracture behavior characteristics according to the deformation rate of the forged SUS316L rod charged hydrogen through the water electrolysis test.

Deformation rates of 3 and 7.5mm/min were not applied to the hydrogen-penetrated specimen in the test. This is because it was assumed that the deformation rate between the minimum and maximum deformation rates (2 and 10mm/min) would follow certain trends, as in the tensile test results before hydrogen penetration. Therefore, additional tests were conducted by reflecting these parts to improve reliability in terms of test precision. As shown in

Figure 6, the elongation and cross-section reduction rate of the hydrogen-penetrated specimen were expressed as Equations (2, 3) through interpolation with the linear equation based on the maximum and minimum values. They can be used for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation when the deformation rate increases or the slow strain rate tensile test is conducted. In Equations (2, 3), v is the tensile deformation rate, RA is the cross-section reduction rate, and

is the elongation. These equations can be used to evaluate the specimens penetrated by hydrogen in a way that generates hydrogen gas at room temperature.

The functional formulas could vary depending on additional variables, such as the metal material of the specimen, element content, specimen temperature, test environment temperature, test pressure, amount of residual hydrogen according to the hydrogen penetration method, microstructure, and applied processing method. In particular, further experiments are required on the hydrogen energy use environment and important temperature and pressure conditions. In addition, tests need to be conducted using the specimen size according to the tensile test standard for precise evaluation of mechanical properties. It is also important to compare specimen fracture results to secure reliability by selecting specimens for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation that can more clearly confirm changes in cross-section reduction rate and elongation due to hydrogen embrittlement.

4. Discussion

The mechanical performance of materials in terms of strength was not fully satisfied because a deformation rate higher than the tensile deformation rate presented in the tensile test standard was arbitrarily applied. Because hydrogen embrittlement increases strength, prior tests to establish test and design standards before and after hydrogen embrittlement are essential. In the future, it is necessary to conduct repeated tests under the same test conditions and compare results to secure the reliability of test measurement values.

The tensile test specimen based on the ASTM E8 standard must be continuously used for mechanical property evaluation to measure changes in elongation. It is also necessary to prepare additional specimens with a longer gauge length than the existing specimen and use them for hydrogen embrittlement resistance measurement. This study proved that the degree of embrittlement can also be evaluated using the ASTM E8 standard specimen by measuring the elongation and especially the cross-section reduction rate. Evaluation criteria are expected to be different because the difference in the amount of residual hydrogen inside caused by the difference in the specimen area and volume touched by hydrogen can be a variable.

Here, hydrogen embrittlement was evaluated by setting the hydrogen penetration time to 48h, but a preliminary study proved the largest embrittlement phenomenon occurred at 24h. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the difference in hydrogen penetration between the metal surface and the inside according to the hydrogen penetration time. It is also judged that the rate at which hydrogen diffuses and escapes to the outside over time during the low-speed tensile test and the amount are important variables for mechanical property evaluation. Because the hydrogen gas penetration test through the water electrolysis method and the hydrogen penetration rate in the high-pressure hydrogen gas environment will be different, in-depth research will be conducted in the future. For this, mechanical property change tendencies of materials for hydrogen energy must be observed by selecting at least two types of specimens, fixing dimensions, and providing different test conditions.

Functions used for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation will vary depending on additional variables, such as the deformation rate, specimen size, and amount of hydrogen penetration. Through continuous research and development, there is a possibility that complex polynomials that add additional constants or equations according to the influence of each variable will be developed.

Regarding the nickel equivalent used as an index for hydrogen embrittlement evaluation, the Sanga’s equation that considers the influence of nitrogen and other elements, including the Hirayama’s equation, can also be considered for nickel equivalent evaluation. Presenting hydrogen embrittlement evaluation criteria for processed materials with nickel equivalent alone is difficult. However, it can be used as an index for determining the suitability of materials for hydrogen energy. It needs to be analyzed with additional variables, such as SFE.

The Ludwik’s equation is useful when it is necessary to implement material properties by interpolating flow curves for engineers who design materials considering the element content. Because only this equation can directly express the change in yield stress with the Voce’s equation in relation to the chemical elements and density of the material, it has been used in related studies [

26]. The hydrogen embrittlement evaluation test must consider the yield stress because the graph begins with the yield strength in the plastic region except for the elastic section.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the tensile test was conducted with the hydrogen-penetrated specimen to evaluate hydrogen embrittlement resistance, and hydrogen energy material evaluation criteria for safety design were established by analyzing the test results. The research results were summarized as follows:

(1) When hydrogen gas was generated in SUS316L, the strength of the material increased owing to the embrittlement phenomenon caused by the diffusion of hydrogen on the surface and inside. Regardless of the tensile deformation rate, the penetration of hydrogen into the metal tended to increase the yield and tensile strength. The yield and tensile strength increased by a minimum of 122 and 5MPa at a deformation rate of 2mm/min, a maximum of 146 and 26MPa at 10mm/min, respectively.

(2) The elongation and cross-section reduction rate tended to decrease as the tensile deformation rate increased. Equations to calculate the elongation and cross-section reduction rate according to the deformation rate should vary depending on the hydrogen energy use environment. The effect of the deformation rate of an SUS316L round bar on hydrogen embrittlement at room temperature can be predicted using the formula presented here.

(3) When the amount of residual hydrogen was measured by setting the hydrogen penetration time of the selected specimen to 48h under the application of a current density of 20A/m2 or higher, the presence of approximately 1.8134ppm of hydrogen was confirmed through gas chromatography. Because the amount was smaller than expected, it will be necessary to identify factors that affect the amount of residual hydrogen through continuous research on test environments and conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-T.A., D.-H.C and J.-H.P.; methodology, M.-T.A., D.-H.C and J.-H.P.; software, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; validation, J.-H.P.; formal analysis, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; investigation, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; data curation, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; writing—original draft preparation, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; writing—review and editing, J.-H.P.; visualization, M.-T.A., D.-H.C; supervision, J.-H.P.; project administration, J.-H.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1F1A1064158)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Park, H. K.; Park, J. S. Simulation study of hydrogen liquefaction process using helium refrigeration cycle. The Korean Society of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 2020, 31, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpakjian, S.; Schmid, S. Manufacturing Processes for Engineering Materials. Second edition. Prentice-Hall, 2007.

- Hwang, J. S.; Nguyen, L. H.; Kim, M. S.; Lee, J. M. Evaluation of hydrogen embrittlement resistance of stainless steel 316L material used at cryogenic temperatures. Journal of Advanced Marine Engineering and Technology, 2019, 43, 254-262. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.H.; Joe, M.W.; Kim, S.H.; Han, D.H.; Yoo, K.H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, J.S. evaluation and prediction of formation of heat-affected zone and mechanical properties according to welding method of STS 316L/A516-70N clad plates. Korean Journal of Metals and Materials, 2022, 60, 873-883. 60. [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, T.; Ogirima, M. Influence of chemical composition on martensitic transformation in Fe-Cr-Ni stainless steel. Journal of the Japan Institute of Metals and Materials, 2008, 34, 507-510. [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D. M. Hydrogen embrittlement testing of austenitic stainless steels SUS 316 and 316L. The University of British Columbia, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Korean Industrial Standard. Cold finished stainless steel bars, KS D 3692; Korean Standards Association: Seoul, Korea, 2018, 1-7.

- Korean Industrial Standard. Stainless steel bars, KS D 3706; Korean Standards Association: Seoul, Korea, 2017, 1-18.

- Nguyen, L. H.; Hwang, J. S.; Kim, M. S.; Kim, J. H.; Kim, S. K.; Lee, J. M. Charpy impact properties of hydrogen-exposed 316L stainless steel at ambient and cryogenic temperatures. Metals, 2019, 9, 625. 9. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Tsuzaki, K. Chemical composition dependence of the strength and ductility enhancement by solute hydrogen in Fe–Cr–Ni-based austenitic alloys. Materials Science and Engineering, 2022, 836, 142681. [CrossRef]

- Queiroga, L. R.; Marcolino, G. F.; Santos, M.; Rodrigues, G.; Santos, C. E.; Brito, P. Influence of machining parameters on surface roughness and susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement of austenitic stainless steels. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2019, 44, 29027-29033. [CrossRef]

- Depover, T.; Escobar, D. P.; Wallaert, E.; Zermout, Z.; Verbeken, K. Effect of hydrogen charging on the mechanical properties of advanced high strength steels. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2014, 39, 4647-4656. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R. J.; Wang, Z. D.; Qiao, L. J.; Pang, X. L. Effect of in-situ nanoparticles on the mechanical properties and hydrogen embrittlement of high-strength steel. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials, 2021, 28, 644. [CrossRef]

- ASTM 493-95; An American National Standard. Standard specification for stainless steel wire and wire rods for cold heading and cold forging, USA, 2004, 1–3.

- Dai, Q.X.; Cheng, X.N.; Luo, X.M.; Zhao, Y.T., Structural parameters of the martensite transformation for austenitic steels, Materials Characterization, 2002, 49, 367-371. [CrossRef]

- Schramm, R.E.; Reed, R.P. Stacking fault energies of seven commercial austenitic stainless steels, Metallurgical Transactions, 1975, 6, 1345–1351. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.G.; Thompson, A.W.; The composition dependence of stacking fault energy in austenitic stainless steels, Metallurgical Transactions, 1977, 8, 1901–1906. [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, T.; Suzuki, K.; Ooki, S.; Hashimoto, A. The effect of chemical composition and heat treatment conditions on stacking fault energy for Fe-Cr-Ni austenitic stainless steel, Metallurgical and Materials Transactions, 2013, 44, 5884-5896. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, F.B. Physical metallurgical development of stainless steels, Gothenburg, 1984, 2-28.

- Brofman, P. J.; Ansell, G.S. On the effect of carbon on the stacking fault energy of austenitic stainless steels. Metallurgical Transactions, 1978, 9, 879–880. 9. [CrossRef]

- Ojima, M.; Adachi, Y.; Tomota, Y.; Katada, Y.; Kaneko, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Saka, H.; Weak beam TEM study on stacking fault energy of high nitrogen steels, International Conference on Interstitially Alloyed Steels, 2009, 80, 477-481.

- Korean Industrial Standard. Test pieces for tensile test for metallic materials, KS B 0801; Korean Standards Association: Seoul, Korea, 2017, 1-18

.

- ASTM E8/E8M; Standard test methods of tension testing of metallic materials. Annual Book or ASTM Standards, American Society for Testing and Materials, 3.01.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 16573 Steel—Measurement method for the evaluation of hydrogen embrittlement resistance of high strength steels, 2020, 1-11.

- Yi, D. Y. Plastic Processing. Third Edition, Moonwundang, 2005, 101-144.

- Kang, T. H.; Yoon, S. C.; Kim, M. W.; Lee, S. J. Plastic deformation behavior of sintered Fe-based alloys for light-weight automotive components, 2014, 23, 151-159.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).