1. Introduction

Fentanyl is used in clinical settings to manage severe pain in cases such as cancer patients or after surgery. However, it is increasingly being used illicitly, either as a stand-alone drug or mixed with other substances such as heroin, cocaine, or counterfeit prescription pills; which can result in unintentional overdoses and fatalities [

1,

2]. The illicit use of fentanyl has led to a surge in opioid-related deaths worldwide due in part to the fact that fentanyl is up to 100 times more potent than morphine, and just a small amount (approximately 2 mg) can be lethal. In the United States, for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 70,000 deaths from overdoses involving fentanyl in 2021. Canada has also seen a significant increase in fentanyl-related deaths, with greater than 75% of all opioid deaths post 2020 due to fentanyl [

3]. While there are fewer but significant numbers of deaths in Europe and the rest of the world, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) has put out warnings regarding rampant fentanyl diffusion in different areas of Europe as well as the presence of new formulations of fentanyl analogs, with some of them up to 10,000 times more potent than morphine [

4].

Addressing the fentanyl problem requires a multifaceted approach, including strategies to reduce the availability of illicit fentanyl through law enforcement efforts, improving access to treatment for opioid addiction, and increasing public awareness of the dangers of fentanyl. Additionally, there is a need for improved detection and analytical methods to identify fentanyl for law enforcement, or for detection of fentanyl contamination in other drugs. Current methods of detection and analysis of fentanyl and its analogs involve various spectroscopic or chromatographic techniques such as LC-HRMS [

5], SPME-GC-MS [

6], GC-IR [

7], GC-ECD [

8], LC-UV [

9], IMS [

10], and other methods [

11,

12,

13]. However, these methods are expensive, time-consuming, require large instrumentation that is generally unportable, and necessitates skilled individuals to carry out the test procedures. Other methods for visual and sensitive detection include surfactant-based colorimetric tests [

14,

15], electrochemical sensors [

16,

17], and immunoassays, for instance, ELISAs, EMITs, and LFAs [

18]. Recently, antibody-based fentanyl test strips (FTS) have attracted attention due to their small size, portability, and simplicity of use; however, antibodies suffer from poor stability under varying conditions, prolonged manufacture times and can provide false positive responses.

The development of molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) as the molecular recognition component for fentanyl sensors and separations is a promising advancement in this area

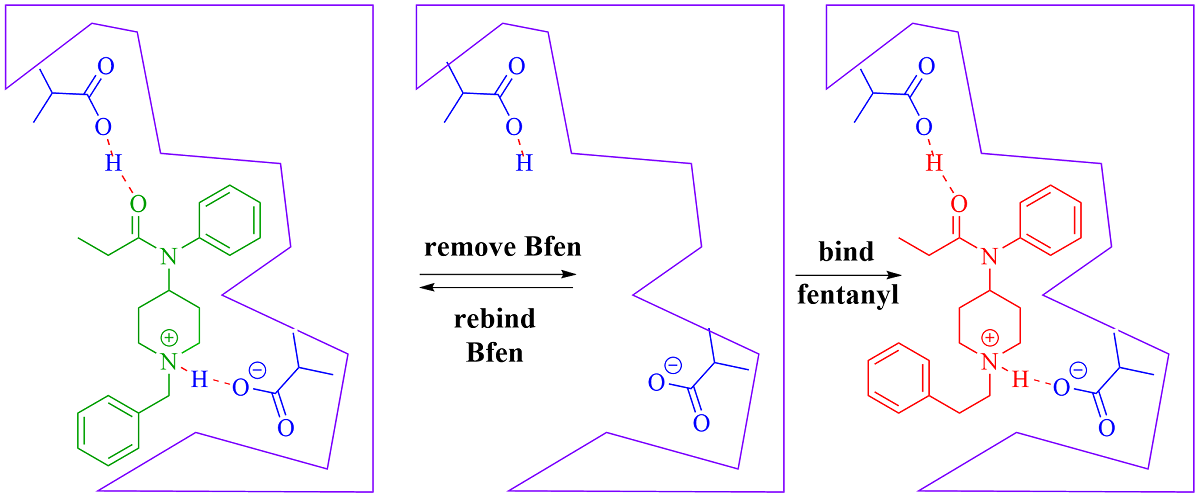

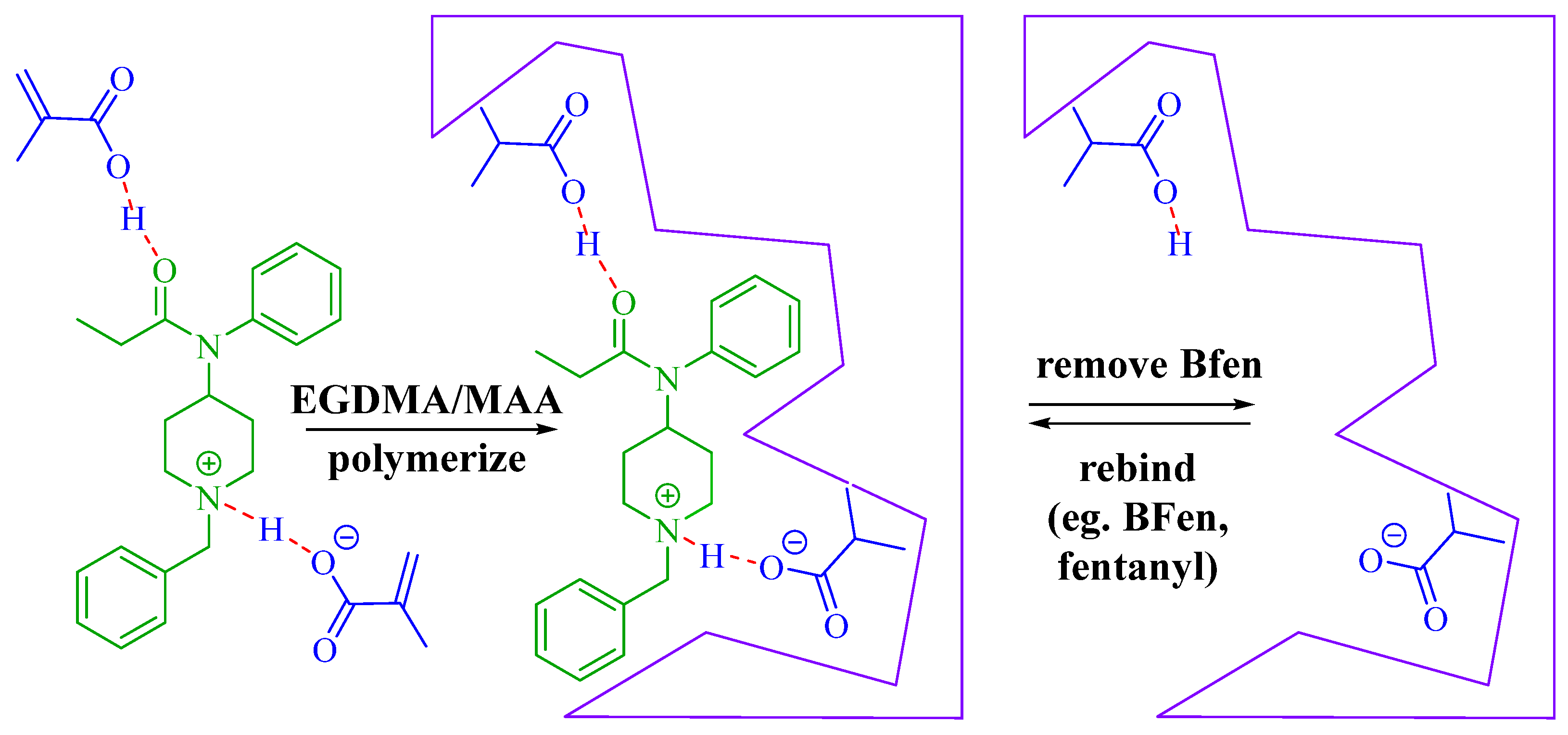

. MIPs are very stable and can maintain their recognition properties for decades, even when exposed to high or low temperatures, different solvents, and variable humidity. Moreover, MIPs are inexpensive, and can be adjusted chemically to maximize performance characteristics. Synthesis of MIPs begins with the formation of a complex between a targeted template molecule (e.g., fentanyl) and monomer(s), which is most easily accomplished via non-covalent interactions by simple mixing of these components in solvent (

Scheme 1). The complex is polymerized and the template is removed by simple extraction to leave cavities in the polymer that are imprinted to match the shape of the template and provide functional groups in a complementary interactive array to the template. There have been two previous reports of molecular imprinting of fentanyl, the earliest describing a fentanyl imprinted silicate xerogel developed for extraction based assays that exhibited an increase in adsorbed fentanyl versus non-imprinted xerogel materials with selectivity versus donepezil [

19]. The second report imprinted carboxyl-fentanyl in nanoparticles using a multimonomer mixture applied to a long period grating sensor that selectively detected the template [

20].

To initiate a long-term goal of optimizing fentanyl-specific binding MIPs, the research in this study explores the effect of changing the ratio of the template versus the amount of functional monomer employed. The optimum formulation was subsequently evaluated for selectivity versus narcotics that are often laced with fentanyl, such as methamphetamine, heroin, and cocaine. Because of the fatal toxicity of fentanyl, a structurally close analog, benzylfentanyl (BFen), was used for the imprinting process, and binding compared to genuine fentanyl. The analog BFen only differs in structure from fentanyl by a single carbon reduction in the N-2-phenylethyl group of fentanyl, and therefore anticipated to best mimic fentanyl during imprinting. The use of an analog versus actual fentanyl will create safe MIPs without toxicity (benzylfentanyl is pharmacologically inactive) [

21,

22] and will eliminate contamination of fentanyl samples by trace amounts of fentanyl remaining in the MIP causing inaccurate detection results. The outcome from these studies set the stage for further optimization studies toward improving the binding uptake and selectivity for fentanyl in MIPs, e.g., use of different monomers, templates, crosslinkers, and monomer/component ratios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, Aldrich) and methacrylic acid (MAA, Aldrich) were distilled in vacuo over boiling chips prior to polymerization. Benzylfentanyl, acetyl-benzylfentanyl (ABF), and benzoyl-benzylfentanyl (BBF) were synthesized as described herein. Fentanyl was synthesized according to the reference [

23]. Heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and 2,2 -azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. The solvents used were HPLC grade, obtained from VWR, and used without further purification.

2.2. Synthesis of benzylfentanyl, acetyl-benzylfentanyl, and benzoyl-benzylfentanyl

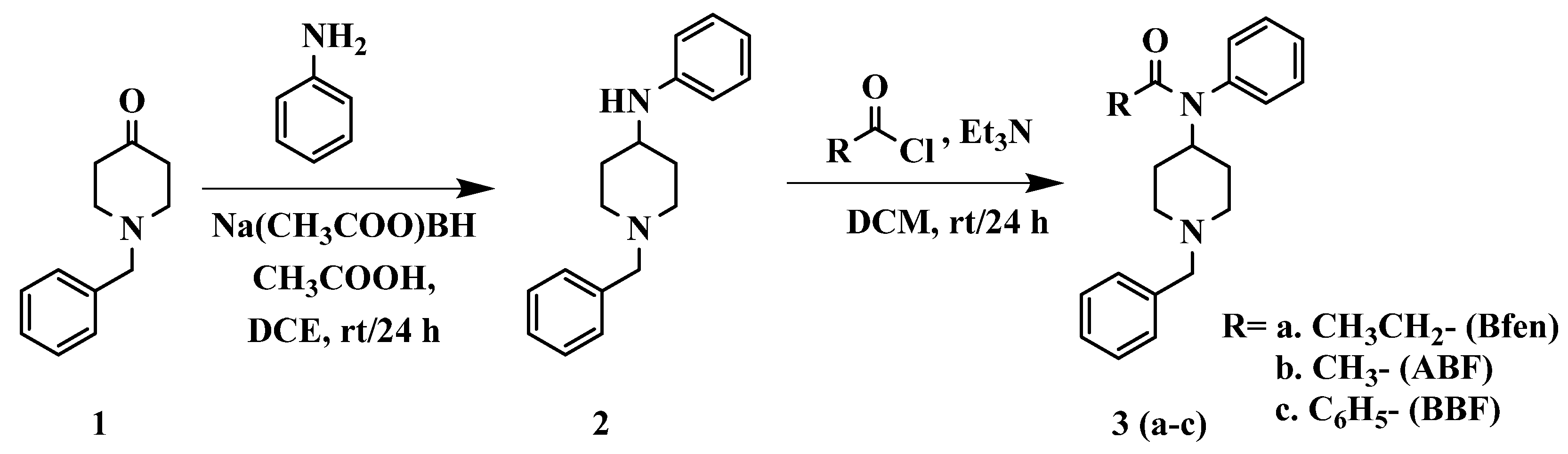

Benzylfentanyl and its derivatives were synthesized by the route shown in

Scheme 2 described below, following similar routes found in the literature, with modifications to obtain the highest overall yield of any publication [

23,

24].

2.2.1. Reductive amination of 1-benzyl-4-piperidone (1)

In a RBF were dissolved 1-benzyl-4-piperidone (1) (4.0 g, 21 mmol) and aniline (4.92 g, 53 mmol) in 1,2-dichloroethane (50 mL), followed by the addition of AcOH (1.27 g, 21 mmol). The reaction mixture was treated with sodium triacetoxyborohydride (6.72 g, 32 mmol) and subsequently stirred at rt for 24 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by adding 1 N NaOH, and the product was extracted with 1,2-dichloroethane. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum to give either a yellow solid or oil. The product was then purified either by recrystallization in hexane or column chromatography using EtOAc:CHCl3 50:50 to obtain a 90% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ 7.21-7.33 (m, 5H), δ 7.02 (t, 2H), δ 6.55 (d, 2H), δ 6.46 (t, 1H), δ 5.35 (d, 1H), δ 3.46 (s, 2H), δ 3.17 (quin, 1H), δ 2.75 (d, 2H), δ 2.06 (t, 2H), δ 1.85 (d, 2H), δ 1.38 (dq, 2H).

2.2.2. Acylation of 1-benzyl-4-(phenylamino) piperidine (2)

1-Benzyl-4-(phenylamino) piperidine (2) (1.0 g, 3.8 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (15 mL), and Et3N (1.14 g, 11 mmol) was added. Subsequently, the appropriate acid chloride (11 mmol) was added to the solution and stirred at rt for 24 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was washed with 1 N NaOH (3 X 15 mL) and 5 N NaOH (2 X 15 mL) and extracted with dichloromethane. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, then concentrated under vacuum to give either a yellow solid or oil. The product was then purified either by recrystallization in hexane or column chromatography using CHCl3:EtOAc 70:30 to obtain yields in the range of 70-87%. Benzylfentanyl (3a): 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ 7.47-7.39 (m, 3H), δ 7.27-7.17 (m, 7H), δ 4.43 (quin, 1H), δ 3.37 (s, 2H), δ 2.75 (d, 2H), δ 1.97 (t, 2H), δ 1.81 (q, 2H), δ 1.65 (d, 2H), δ 1.17 (dq, 2H), δ 0.86 (t, 3H). Acetyl-benzylfentanyl (3b): 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ 7.48-7.40 (m, 3H), δ 7.28-7.24 (m, 2H), δ 7.21-7.15 (m, 5H), δ 4.41 (quin, 1H), δ 3.37 (s, 2H), δ 2.78 (d, 2H), δ 1.97 (t, 2H), δ 1.68 (d, 2H), δ 1.60 (s, 3H), δ 1.21 (dq, 2H). Benzoyl-benzylfentanyl (3c): 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δ 7.34-7.26 (m, 5H), δ 7.22 (dd, 2H), δ 7.18-7.07 (m, 6H), δ 6.97 (dd, 2H), δ 4.80 (quin, 1H), δ 3.65 (s, 2H), δ 3.09 (d, 2H), δ 2.31 (t, 2H), δ 1.91 (d, 2H), δ 1.73 (dq, 2H).

2.3. Polymer preparation

Benzylfentanyl (2.7 mmol) was dissolved in 4 mL of chloroform in a 13 mm 100 mm screw cap tube. EGDMA (21 mmol), MAA (5.4 mmol), and AIBN (0.54 mmol) were added to this solution. The control polymer was prepared similarly, without the introduction of the benzylfentanyl template molecule. Nitrogen gas was bubbled into each solution to purge for 5 min, then capped and sealed with parafilm.

The samples were placed into a photochemical reactor immersed in a constant temperature water/ethylene glycol bath and equilibrated to 19°C. A standard laboratory UV light source (a Canrad–Hanovia medium pressure 450 W mercury arc lamp) jacketed in a borosilicate double-walled immersion well immersed in the bath, and the polymerization was initiated photochemically. The system's temperature was maintained by both the cooling jacket surrounding the lamp and the constant temperature bath. The polymerization reaction was run for 8 h; afterward, the sample tubes were manually cracked open and the polymer was removed. The polymers were lightly crushed for Soxhlet extraction using methanol overnight before grinding and sizing.

2.4. Particle Sizing

Bulk processed MIP materials are most often ground and sized prior to packing in columns that are subsequently evaluated for binding. Thus, the polymers were ground utilizing a mortar and pestle, and the particles were sized using USA Standard Testing Sieves (VWR), or Whatman #1 filter paper. The sieved particles were collected in the 25-37 micron range; the particles passing below the 25 micron sieves were further filtered through Whatman #1 filter paper to provide particles in the 11-25 micron range. Prior to evaluation, both particle sizes were separately slurry packed into HPLC columns (10cm x 4.1mm i.d.) using a Beckman 1108 Solvent Delivery Module, and eluted overnight with 95/5 (v/v): MeCN/H2O, after which the baseline was steady indicating no further BFen needed to be removed.

2.5. Chromatographic tests

A Hitachi L-7100 pump with Hitachi L-7400 detector was used for the HPLC analysis which was carried out isocratically at room temperature (22 °C). Prior to chromatographic testing, the columns were equilibrated with the desired mobile phase. Samples comprised of 20µL of a 0.1 mM solution of different analytes in acetonitrile were injected onto the HPLC, and the chromatographic values detected at λ = 254 nm were reported as the average value of triplicate runs. Acetone was used as the inert substance to determine the void volume. The capacity factors were calculated by the relation , where is the retention time of the analyte, and is the void volume. The imprinting factor (IF) was calculated as the ratio of capacity factors from the imprinted column over the non-imprinted column (). Finally, to determine the selectivity of the MIP, the cross-binding selectivity was calculated by the relation , where is the capacity factors of the analyte and is the capacity factors of benzylfentanyl.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of MIP parameters

There are a number of variables that affect the optimization of selective binding by the BFen-MIP, such as template:functional monomer ratio, particle size, mobile phase composition and flow rate. Each of these parameters was evaluated in turn before the final evaluation of binding and selectivity of fentanyl, its analogs and select narcotics often found laced with fentanyl or its derivatives.

3.1.1. Optimization of template:functional monomer ratio

The first variable investigated was the optimum template:functional monomer ratio, which was carried out by synthesis of 5 different BFen-MIPs incorporating different amounts of the BFen template, while keeping the formulation of crosslinker (EGDMA):functional monomer (MAA):initiator (AIBN) at the value 78:20:2. It should be noted that these polymer components add up to 100% of the MIP material, which does not include the template because the template is removed in the final step of MIP preparation. Therefore, the template does not contribute to the composition of the final material.

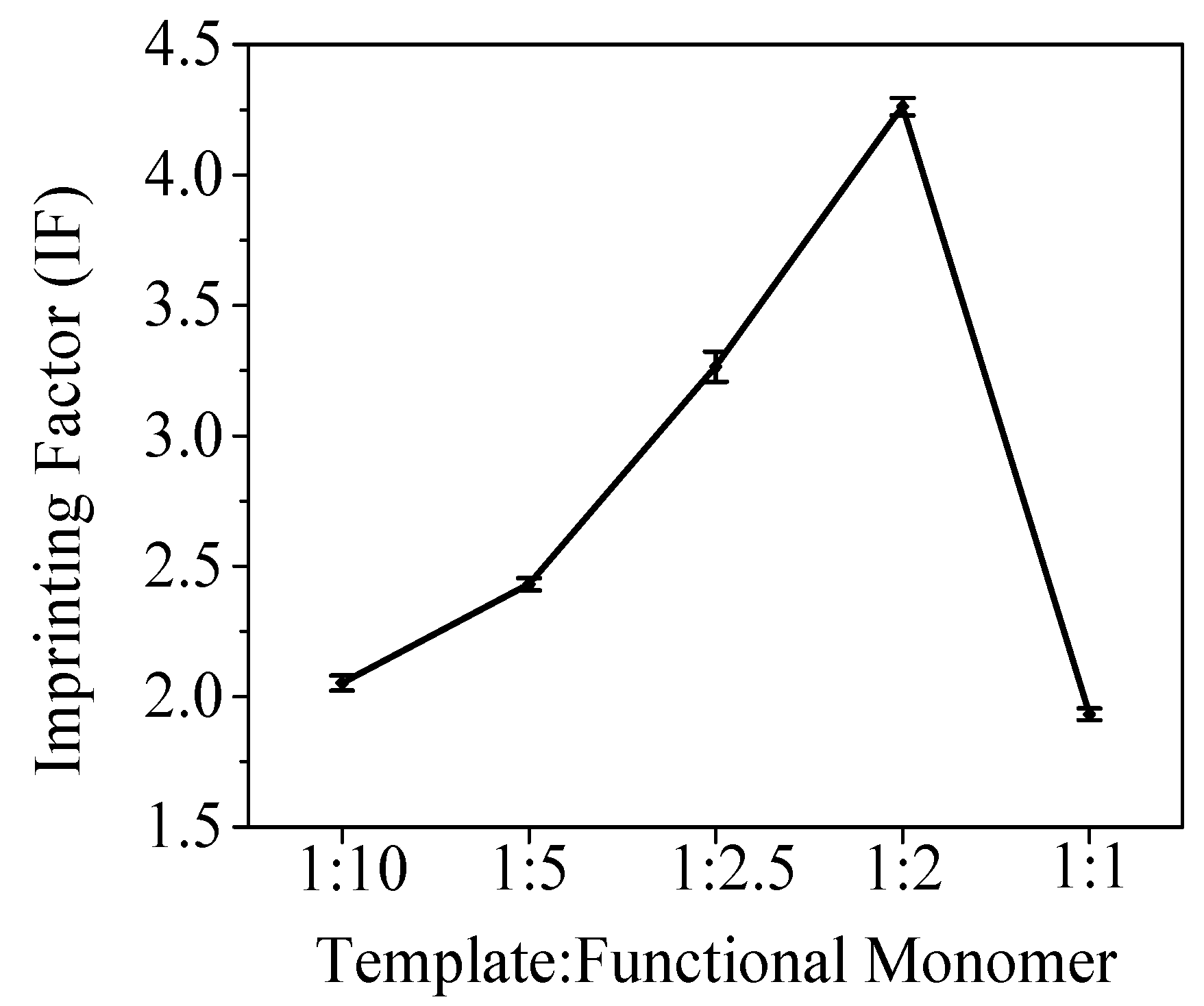

The ratios of template:functional monomer tested were 1:10, 1:5, 1:2.5, 1:2, and 1:1; which provided a good range of data to observe the performance trend. The 5 synthesized MIPs were evaluated using the imprinting factor (IF) as the figure of merit, following the methods described in the "Chromatographic tests" portion of the "Materials and Methods" section (vide supra). The IF measures the increase in the ratio of BFen binding for the imprinted polymer versus the non-imprinted polymer, in essence providing a measure of the "imprinting effect" where better imprinting is indicated by larger IF values.

The results are shown in

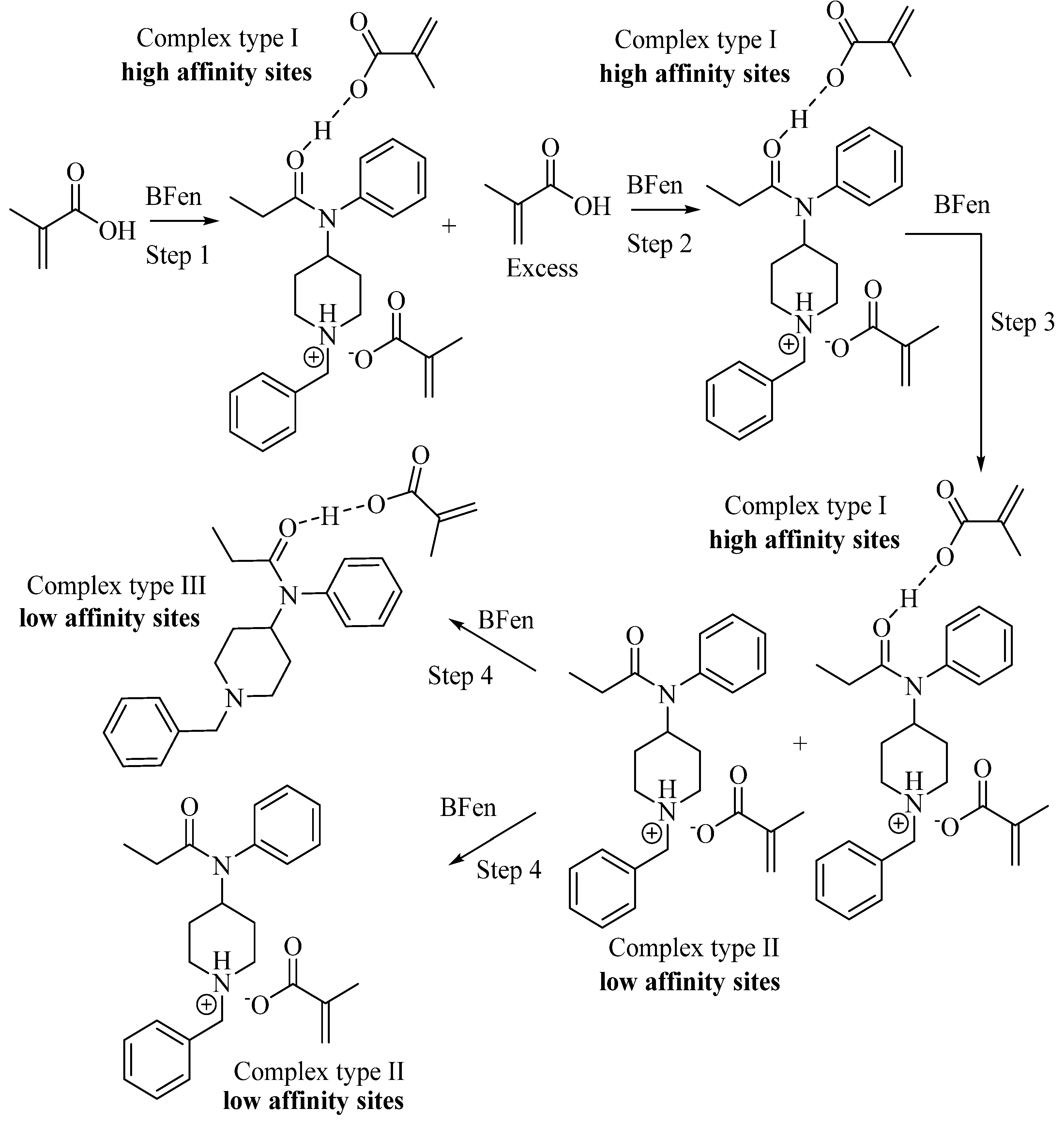

Figure 1 indicating the best IF occurs at a template:functional monomer ratio of 1:2. This optimum ratio can be explained by the template:functional monomer complexes illustrated in

Scheme 3, showing the solution phase intermediates in template-functional monomer complex formation as the amount of template is increased, similarly described for other MIPs [

25]. After BFen is added to MAA in step 1 of

Scheme 3, it is envisioned that the template is fully complexed to give "complex I", with the remaining excess MAA not complexed to the template. As the template concentration increases, as in the case of the 1:5, 1:2.5, and 1:2 ratios; the absolute concentration of "complex I" increases which leads to a proportional increase in the total number of binding sites per gram of MIP, which in turn increases the IF (per gram of MIP) as shown in

Figure 1. This means the "imprinting effect" increases as the density of binding sites increases per gram of MIP. When the ratio reaches 1:2, the maximum concentration of "complex I" is reached, and there is no longer any excess MAA. At this point, the maximum number of "high affinity" binding sites has been reached, leading to the maximum "imprinting effect" or IF observed. Further increasing the template to give the ratio 1:1 decreases the number of "high affinity" sites ("complex I") which are replaced by low affinity sites ("complex II" and "complex III"). The low affinity sites are a result of fewer functional monomers bound to the template, lowering the enthalpic and entropic contributions to binding. Thus, the overall "imprinting effect" goes down as the high affinity sites are replaced by the low affinity sites. From these results, the ratio 1:2 template:functional monomer was chosen for subsequent studies.

3.1.2. Particle size optimization

There have been several reports that assess the chromatographic performance of different sized MIP particles from which some generalizations can be made [

26,

27]. One of the clearest findings is that MIP sizes greater than 63 µm show poor selectivities and lower retention time due to mass transfer issues of solutes through the larger particles. On the other hand, there have been mixed findings for MIP particles ground to smaller sizes. Previous studies have shown that particle size ranges above 25µm have provided better binding results than particles smaller than 25µm, despite increased number of theoretical plates and fewer problems anticipated with mass transfer associated with smaller particles in chromatography [

26]. Therefore, for this study, two different particle size ranges were investigated; the larger sized particles were obtained using standard sieves in the 25-37 µm range, and the smaller sized particles in the 11-25 µm range were obtained by filtering the particles below 25 µm through Whatman #1 filter paper.

Two separate columns were slurry packed with the differently sized MIPs, and evaluated using a mobile phase system consisting of MeCN/H

2O, 99.9/0.1 respectively. The results shown in

Table 1 indicate that the particle sizes of 25-37 µm produce better IF values versus the particle size range 11-25 µm, which correlates with the findings of previous studies [

26,

27].

A priori, it could be envisaged that the smaller particles should provide a better IF due to increased surface accessibility, shorter path-length diffusion distances for quicker mass-transfer kinetics of substrates, and access to more buried binding sites. However, the data show this is not the case, which has been attributed previously to a scenario whereby a considerable number of binding sites may have been destroyed during the grinding process to smaller sized particles. Based on these findings, the 25-37 µm sized particles were used for further studies.

3.1.3. Mobile phase composition and flow rate

The optimum mobile phase conditions were evaluated using various acetonitrile and water proportions, and it was first determined that elution of BFen in 95/5 (v/v): MeCN/H2O yielded retention values near the void volume, suggesting that the mobile phase was excessively polar. Systematically lowering the water component in acetonitrile to 1% and subsequently to 0.1% indicated longer elution durations, with 100% MeCN producing the longest eluting peak indicating the highest binding affinity. Mobile phases containing 1% and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile were also examined to see whether the protonation state of the BFen affected binding; unfortunately the retention durations were reduced. Thus, the acid component provided unacceptably high elutropic strength, and therefore it was decided that 100% MeCN was the best mobile phase. In addition, several flow rates were evaluated (0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mL/min); however, the IF stayed the same in all cases and the faster flow rate of 1.0 mL/min was chosen for further studies.

3.2. Evaluation of Selectivity

The selectivity of the MIP for the template, BFen, and more crucially fentanyl, was compared to other regularly encountered narcotics known to be contaminated with fentanyl, such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. In addition, two fentanyl analogs, acetyl-benzylfentanyl (ABF) and benzoyl-benzylfentanyl (BBF), with structural similarities to fentanyl, were also examined.

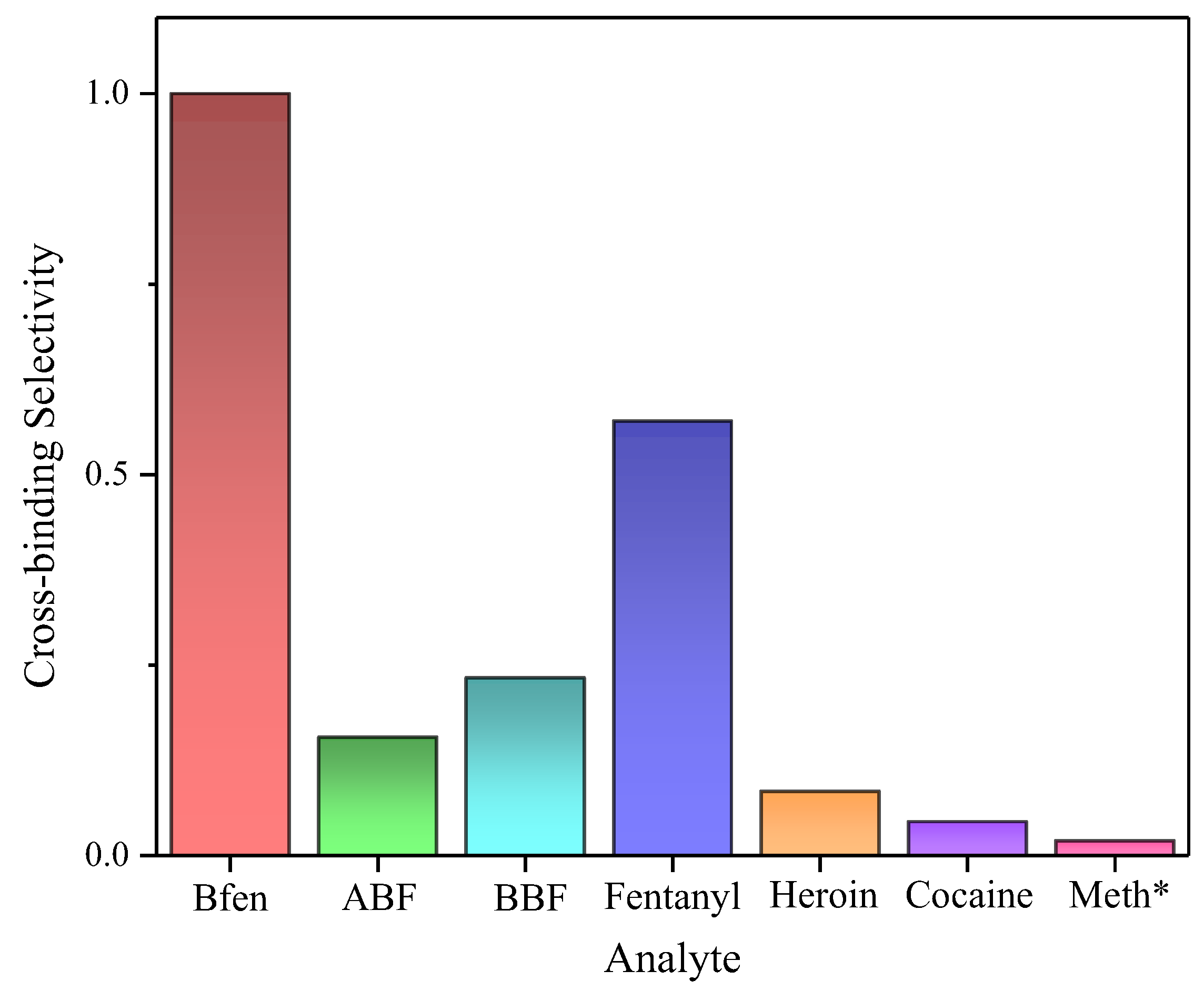

The results of the chromatographic experiments are shown in

Figure 2, with the best selectivity found for BFen, which the MIP was originally developed for. This is the usual finding for MIP technology, i.e. the template binds best to its own imprinted polymer [

28]. To evaluate the cross-binding selectivity (CBS) of the other compounds tested, the capacity factors were normalized relative to BFen binding as described in section 2.5. The second best recognized analyte was fentanyl, a very important finding that opens the door to using this MIP for promising applications in the detection and/or separation of fentanyl from other substances. For example

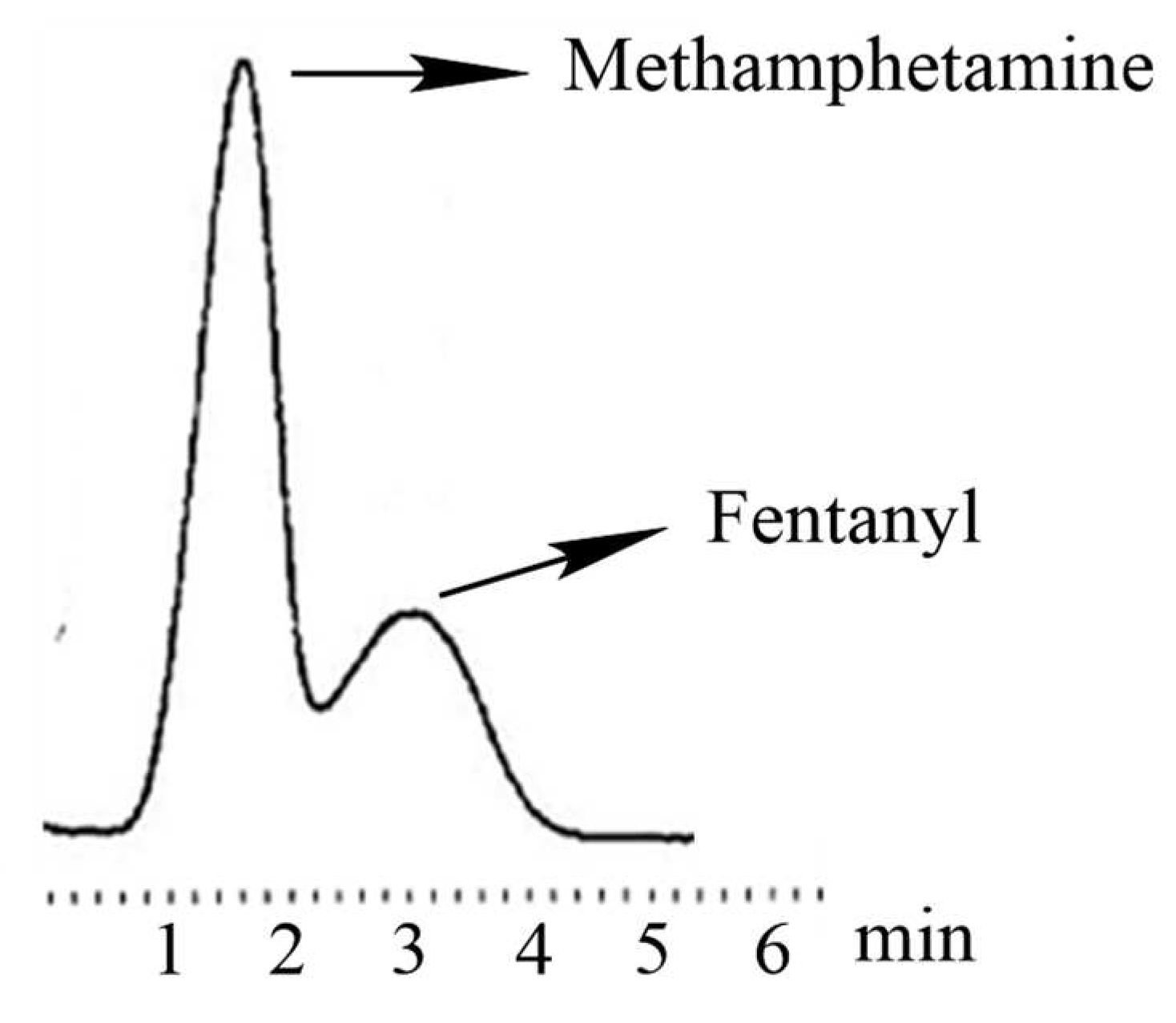

Figure 3 shows a typical MIP-based separation of fentanyl from methamphetamine, demonstrating the ability of the BFen-MIP to distinguish fentanyl laced in another narcotic. This suggests that the BFen-MIP could serve as the recognition component of fentanyl sensors for law-enforcement, or in commercial test-strips for point-of-care analysis. The related compounds ABF and BBF, also appear to show significantly less binding in spite of their structural similarity to fentanyl. The higher binding seen for BBF versus ABF is possibly due to increased non-specific binding to the more hydrophobic benzene group.

The second best recognized analyte was fentanyl, a very important finding that opens the door to using this MIP for promising applications in the detection and/or separation of fentanyl from other substances. For example,

Figure 3 shows a typical MIP-based separation of fentanyl from methamphetamine, demonstrating the ability of the BFen-MIP to distinguish fentanyl laced in another narcotic. This suggests that the BFen-MIP could serve as the recognition component of fentanyl sensors for law-enforcement, or in commercial test-strips for point-of-care analysis. The related compounds ABF and BBF, also appear to show significantly less binding in spite of their structural similarity to fentanyl. The higher binding seen for BBF versus ABF is possibly due to increased non-specific binding to the more hydrophobic benzene group.

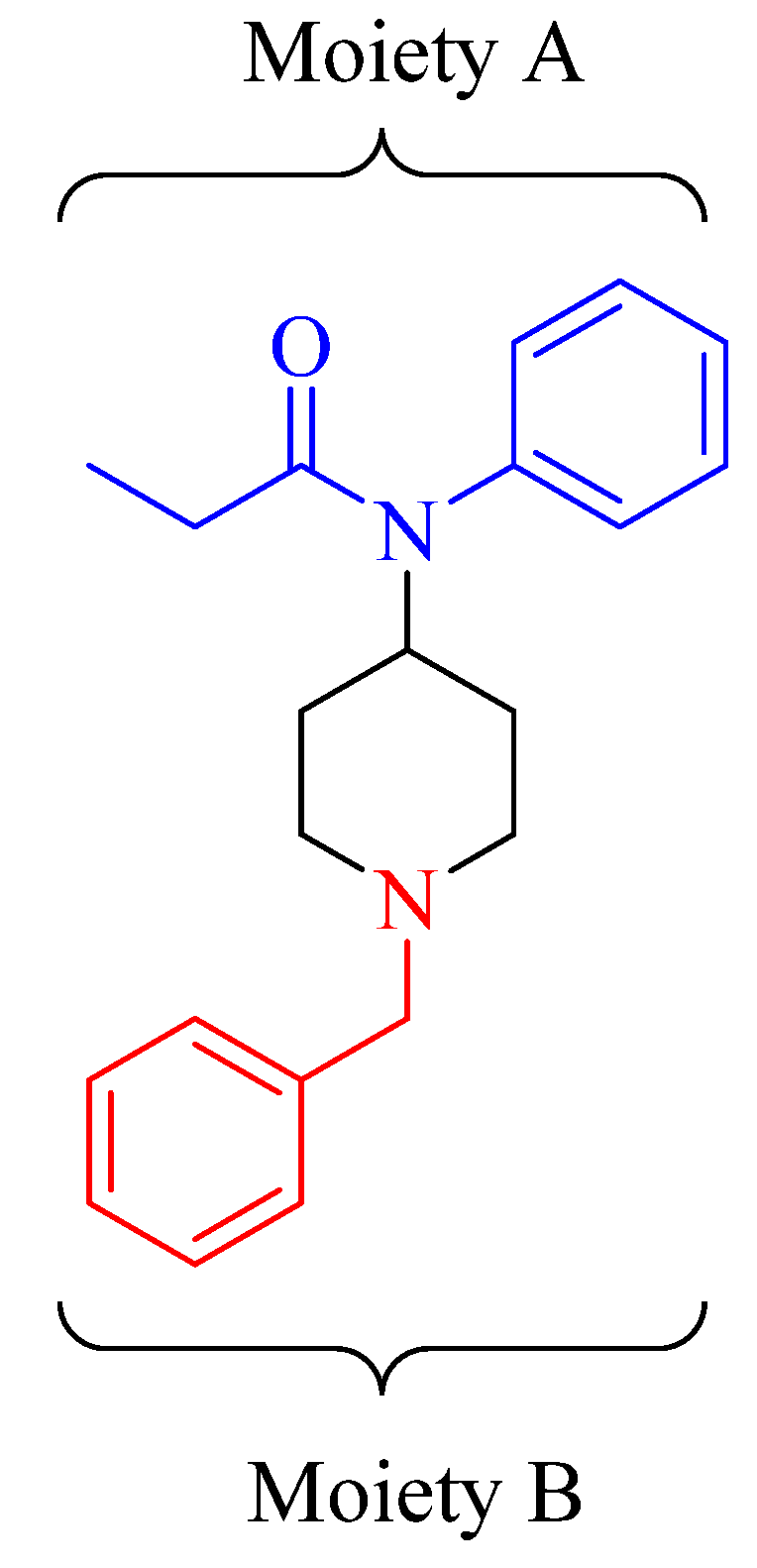

The significant difference in binding of BFen and fentanyl versus ABF and BBF is curious, and points to sub-structures of fentanyl and its analogs that have greater influence on binding. For instance,

Figure 4 splits BFen into two moieties representing the top and bottom halves of the molecule. The top moiety (A) is found in both BFen and fentanyl, which are the highest binding analogs. However, ABF and BBF have changes in moiety A, and suffer severe loss in binding. On the other hand, ABF and BBF are most similar to BFen with respect to moiety B versus fentanyl, yet fentanyl shows better binding to the MIP. This suggests binding of fentanyl analogs is controlled more by moiety A than moiety B. None-the-less, moiety B does influence binding as seen in the approximately 40% lowering of binding by fentanyl versus BFen, which only differs by one methylene unit in moiety B. This unexpected finding could point toward the design of future analogs that could elicit higher-affinity for fentanyl. Heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine essentially showed negligible binding affinity towards the imprinted polymer indicated by elution close to the void volume, as expected.

4. Conclusions

A fentanyl selective MIP has been synthesized using BFen as the template, anticipated to be the analog most closely resembling fentanyl. A tremendous advantage of using BFen is its significantly lower toxicity versus fentanyl, as well as the important benefit of using analogs as the MIP template which eliminates any interference in detection by leaching of any remaining template. Although the literature has two examples of fentanyl binding MIPs, neither of these reports discussed development of the MIP matrix formulation to maximize binding and/or selectivity of fentanyl. With the long term goal of optimizing fentanyl-specific binding MIPs, a traditional polymer formulation utilizing MAA as the functional monomer and EGDMA as the crosslinker was chosen as the first generation of BFen-MIPs for study. This formulation was successful in selectively binding the template and genuine fentanyl. The best selectivity was found for BFen, which is not surprising since most MIP studies report the template used for imprinting turns out to be the strongest binding analyte. However, it was very encouraging that fentanyl exhibited the next best selectivity in binding to the MIP. The two other benzylfentanyl analogs tested also showed binding to the MIP to a lesser degree, but significantly better than the non-related narcotics in comparison. In general, for MIPs, compounds that are most similar in structure to the template tend to exhibit better binding versus non-related compounds. It is anticipated that this phenomenon could be useful for the detection of a large family of fentanyl analogs which are often encountered as contraband. The low binding of non-related compounds such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine could be strategic in monitoring contamination with fentanyl analogs. Improvements in the fentanyl binding and selectivity using different monomers and crosslinkers, as well as optimization of the MIP component ratios, is currently under investigation. These materials will be further incorporated into detection formats and assays that will someday save many lives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; methodology, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; validation, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; formal analysis, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; investigation, Md.R.H.; resources, D.A.S.; data curation, Md.R.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; writing—review and editing, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; visualization, Md.R.H. and D.A.S.; supervision, D.A.S.; project administration, D.A.S.; funding acquisition, D.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Harry C. Spencer for technical support, and Dr. Christina Sabliov for HPLC access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Drug Enforcement Administration 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment. Available online: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/2019-NDTA-final-01-14-2020_Low_Web-DIR-007-20_2019.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Sharp Increase in Fake Prescription Pills Containing Fentanyl and Meth. Available online: https://www.dea.gov/alert/sharp-increase-fake-prescription-pills-containing-fentanyl-and-meth (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Fischer, B. The continuous opioid death crisis in Canada: changing characteristics and implications for path options forward. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, J.K.; Halpin, J.; Mattson, C.L.; Goldberger, B.A.; Gladden, R.M. Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700—10 states, July–December 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2017, 66, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Halifax, J.C.; Tangsombatvisit, C.; Yun, C.; Pang, S.; Hooshfar, S.; Wu, A.H.; Lynch, K.L. Development and application of a High-Resolution mass spectrometry method for the detection of fentanyl analogs in urine and serum. Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Advances in the Clinical lab 2022, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, S.R.; Fulton, A.C.; DeGreeff, L.E. Comparative analysis of vapor profiles of fentalogs and illicit fentanyl. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2021, 413, 7055–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S. Studies on fentanyl and related compounds: II. Spectrometric discrimination of five monomethylated fentanyl isomers by gas chromatography/Fourier transform-infrared spectrometry. Forensic Science International 1989, 43, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.M.; Allen, A.C.; Cooper, D.A.; Carr, S.M. Determination of fentanyl and related compounds by capillary gas chromatography with electron capture detection. Analytical chemistry 1986, 58, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, I.; Allen, A. Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic separation of fentanyl homologues and analogues: II. Variables affecting hydrophobic group contribution. Journal of Chromatography A 1984, 292, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.D.; Fulton, A.C.; Romanczyk, M.; Giordano, B.C.; Katilie, C.J.; DeGreeff, L.E. Detection of N-phenylpropanamide vapor from fentanyl materials by secondary electrospray ionization-ion mobility spectrometry (SESI-IMS). Talanta Open 2022, 5, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Lian, R.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ouyang, Z. Rapid and on-site detection of multiple fentanyl compounds by dual-ion trap miniature mass spectrometry system. Talanta 2020, 217, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittgen, J.; Pütz, M.; Zimmermann, R. Identification of fentanyl derivatives at trace levels with nonaqueous capillary electrophoresis-electrospray-tandem mass spectrometry (MS n, n= 2, 3): Analytical method and forensic applications. Electrophoresis 2012, 33, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisco, E.; Verkouteren, J.; Staymates, J.; Lawrence, J. Rapid detection of fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, and opioids for on-site or laboratory based drug seizure screening using thermal desorption DART-MS and ion mobility spectrometry. Forensic Chemistry 2017, 4, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Sun, J.; Xiang, X.; Yu, H.; Shao, B.; He, Y. Surfactants directly participate in the molecular recognition for visual and sensitive detection of fentanyl. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2022, 354, 131215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liang, J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Y.; Shao, B. A Chemically Initiated Electron Exchange Chromogenic Reaction System for Colorimetric Detection of Fentanyl and Norfentanyl.

- Glasscott, M.W.; Vannoy, K.J.; Fernando, P.A.I.; Kosgei, G.K.; Moores, L.C.; Dick, J.E. Electrochemical sensors for the detection of fentanyl and its analogs: Foundations and recent advances. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 132, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester, N.; Mynttinen, E.; Etula, J.; Lilius, T.; Kalso, E.; Mikladal, B.F.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Sainio, S.; Nordlund, D. Single-walled carbon nanotube network electrodes for the detection of fentanyl citrate. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2020, 3, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Law, M.Y.; Rollins, D.E.; Moody, D.E. Detection of fentanyl and its analogs by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 1990, 14, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Piri-Moghadam, H.; Bayat, P.; Balalaie, S. Application of sol–gel based molecularly imprinted xerogel for on-line capillary microextraction of fentanyl from urine and plasma samples. Analytical Methods 2013, 5, 7096–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Grillo, F.; Canfarotta, F.; Whitcombe, M.; Morgan, S.P.; Piletsky, S.; Correia, R.; He, C.; Norris, A.; Korposh, S. Carboxyl-fentanyl detection using optical fibre grating-based sensors functionalised with molecularly imprinted nanoparticles. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2021, 177, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanyan, R.S.; Hruby, V.J. Fentanyl-related compounds and derivatives: current status and future prospects for pharmaceutical applications. Future medicinal chemistry 2014, 6, 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.L. Designer drugs: past history and future prospects. Journal of Forensic Science 1988, 33, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Bhutia, Y.D.; Singh, P.; Rao, P.; Gujar, N.L.; Ganesan, K.; Bhattacharya, R. Synthesis and comparative bioefficacy of N-(1-phenethyl-4-piperidinyl) propionanilide (fentanyl) and its 1-substituted analogs in Swiss albino mice. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2013, 22, 3888–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Ni, L.; Shi, J.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, S.; Lam, A.-l.; Magiera, J.; Sekar, S.; Kuo, A.; Smith, M.T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of fentanyl analogues modified at phenyl groups with alkyls. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2018, 10, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Spivak, D.A. New insight into modeling non-covalently imprinted polymers. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125, 11269–11275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, R.; Houck, S.; Spivak, D.A. Comparison of particle size and flow rate optimization for chromatography using one-monomer molecularly imprinted polymers versus traditional non-covalent molecularly imprinted polymers. Analytica chimica acta 2005, 542, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.H.; Rachkov, A.E.; Park, J.K.; Yano, K.; Karube, I. Synthesis and binding properties of a noncovalent molecularly imprinted testosterone-specific polymer. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry 1998, 36, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, D.A.; Simon, R.; Campbell, J. Evidence for shape selectivity in non-covalently imprinted polymers. Analytica chimica acta 2004, 504, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).