3.1. Determination of Antioxidant Activity and Total Polyphenols Spectrophotometrically

The antioxidant capacity of wine samples was determined by ABTS, DPPH and FRAP methods. ABTS analysis revealed the values of the antioxidant capacity of the wines ranging from 2.53 ± 0.04 to 5.59 ± 0.06% (

Table 2). The lowest determined value was for the sample RR VS from organic production, on the contrary, the highest for the sample RM Z from integrated production. In the case of determination of antioxidant capacity by the DPPH method, statistically significant differences were recorded in samples of both red and white varieties. Again, lower values were measured in the organic samples, and the order coincides with the results determined by the ABTS method. The values obtained by the FRAP method range from 20.62 ± 0.22 to 34.22 ± 0.20 µmol/g. Higher values for red wines were also recorded by Jamroz and Bełtowski [

22] or Lino et al. [

23].

Table 2.

Spectrophotometric determination of the antioxidant capacity and total polyphenols.

Table 2.

Spectrophotometric determination of the antioxidant capacity and total polyphenols.

| Analyte |

Method |

Sample |

| RR Z |

RR VS |

RM Z |

RM VS |

| Antioxidant capacity |

ABTS (%) |

2.82 ± 0.18d

|

2.53 ± 0.04d

|

5.59 ± 0.06c

|

4.10 ± 0.24a

|

| DPPH (%) |

41.63 ± 0.78f

|

29.12 ± 0.28e

|

87.94 ± 0.46d

|

80.50 ± 0.10a

|

| FRAP (μmol/g) |

21.60 ± 0.88c

|

20.62 ± 0.22c

|

34.22 ± 0.20b

|

29.59 ± 0.16a

|

Total

Polyphenols (Gallic acid)

|

UV/VIS mg/g |

0.54 ± 0.00a

|

0.40 ± 0.00c

|

1.73 ± 0.05b

|

1.28 ± 0.02d

|

Several studies have been devoted to the relationship of the amount of total polyphenols with the value of antioxidant capacity. From the results we obtained (

Table 2), it is evident that the order of the individual samples corresponds to the order of the samples in the determination of total polyphenols. From this it can be concluded, that the higher amount of total polyphenols means the higher the value of the antioxidant capacity, which was also reached by Ghiselli et al. [

24]. Another study that reports the influence of different flavonoids, but also the synergistic or antagonistic effect of different groups of polyphenols, comes from the collective of authors Di Majo et al. [

25]. The high degree of correlation between antioxidant capacity and the total amount of polyphenols, flavonoids and flavan-3-ols is also confirmed by Minussi et al. [

26], further Li et al. [

27], or Meng et al. [

28].

The possible effect between the type of agricultural management and the amount of all polyphenols in the samples was investigated. The total polyphenols results (represented by gallic acid) are shown in

Table 2. We observe a statistically significant difference between all of them. Values range from 0.40 to 1.73 ± 0.05 mg/g. A higher amount of gallic acid was measured by this method in wine samples from integrated production. The highest value of 1.73 ± 0.05 (mg/g) was recorded for the RM Z sample and the lowest 0.40 ± 0 (mg/g) for the organic sample RR VS. The amount of polyphenols in red wine samples is multiple. This fact also corresponds to the studies of Haseeb et al. [

29], Markoski et al. [

30] and Li et al. [

27], who report up to 10 times higher quantity due to the fermentation of red wines in the presence of skins and other parts of the berries. Tinttunen and Lehtonem [

31] also compared the values of total polyphenols in organic and normal wines within the framework of the study. They analyzed 9 wine samples and in most cases there were more total polyphenols in normal wines without a BIO (organic) declaration.

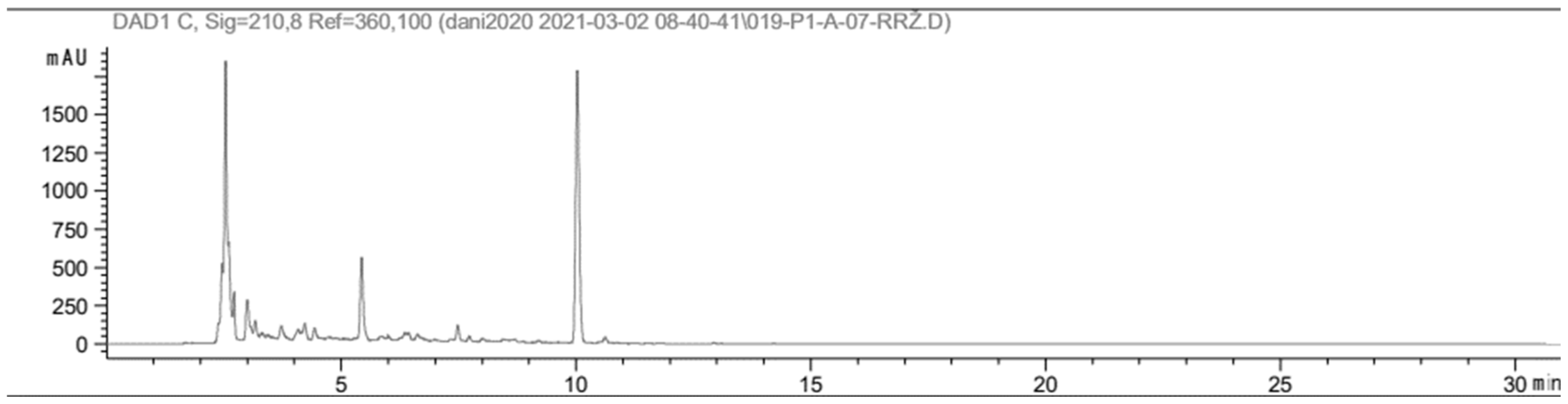

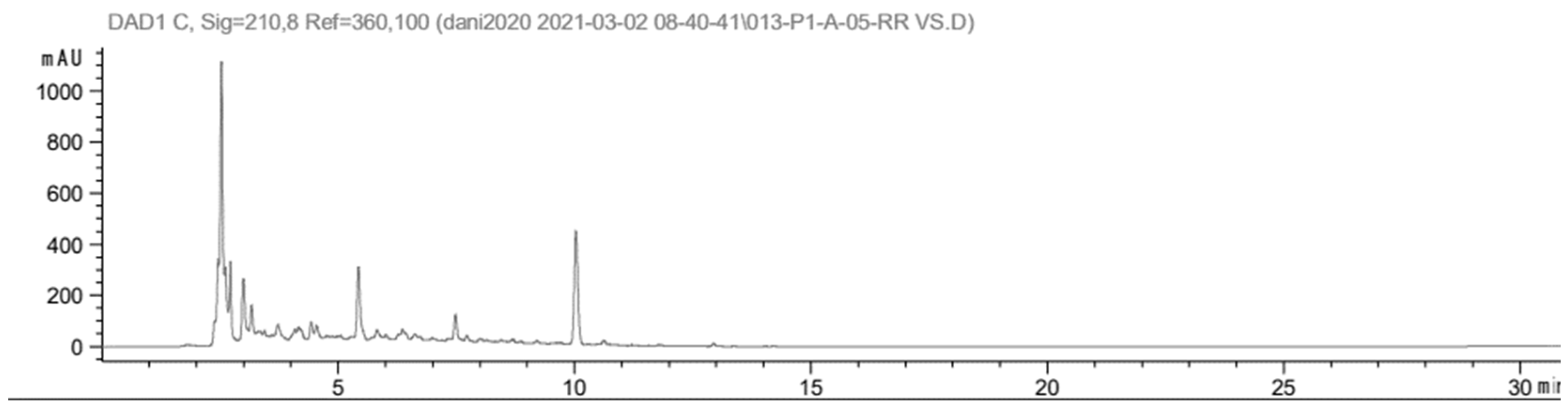

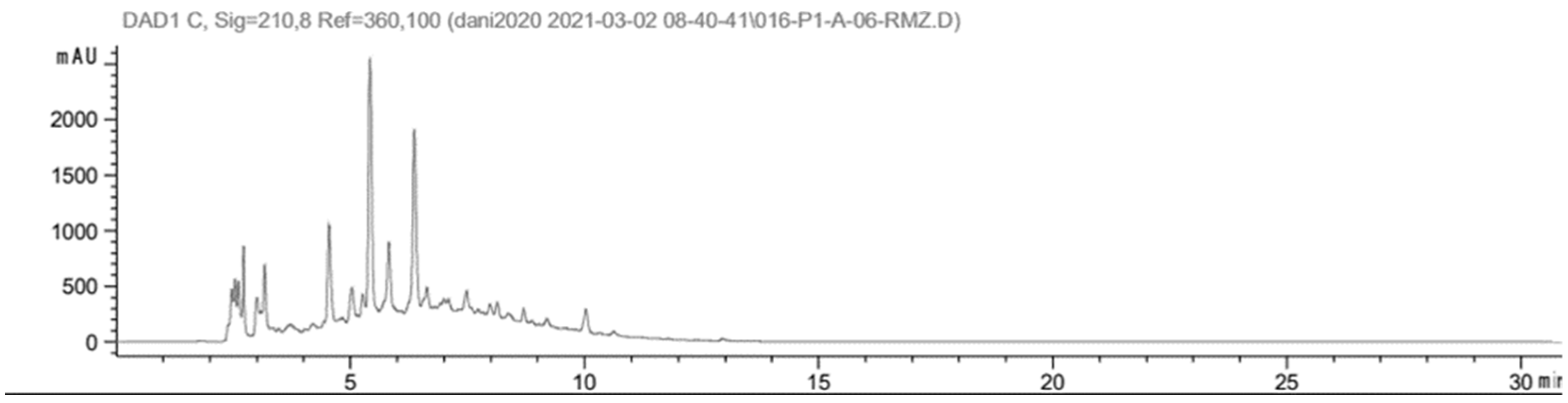

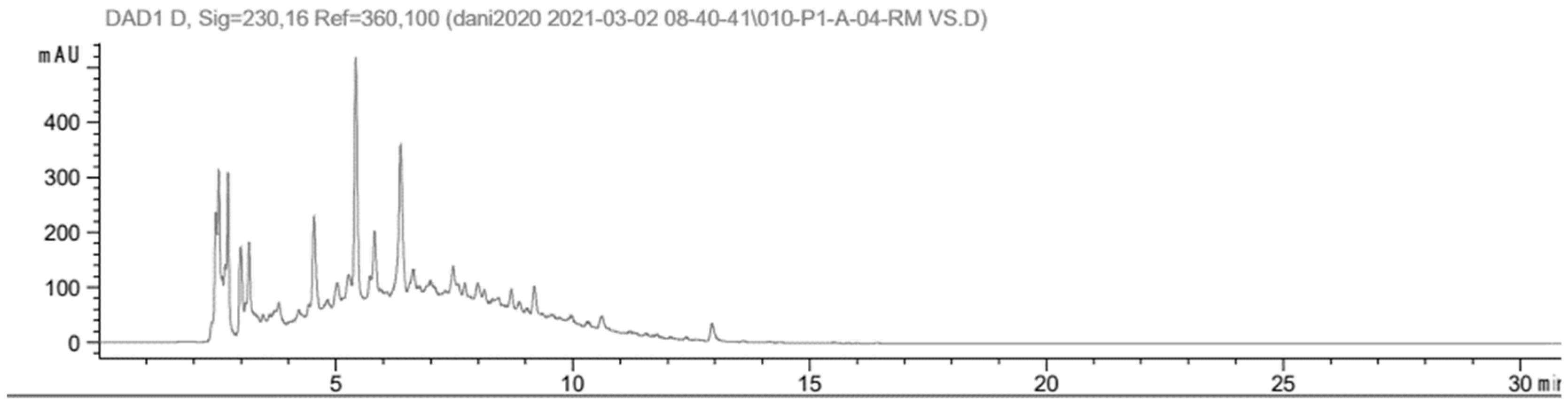

3.2. Phenolic Profile by HPLC

The phenolic profile was also determined using the HPLC method (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). It is clear from the obtained results that a significantly higher amount of polyphenols was recorded in the RR Z sample from integrated production (

Figure 1), which also corresponds to the results obtained in the determination of total polyphenols. In the case of red wine samples, a higher amount is also noticeable in integrated production, i.e. in the RM Z sample (

Figure 3). The similar representation and number of peaks in both red and white wine samples confirms the theory of the influence of the variety on the phenolic profile, which is in line with, for example Paskvanka et al. ( [

32], Shadidi and Naczk [

33], Merkyté et al. [

34].

Figure 1.

Phenolic profile of RR Z sample.

Figure 1.

Phenolic profile of RR Z sample.

Figure 2.

Phenolic profile of RR VS sample.

Figure 2.

Phenolic profile of RR VS sample.

Figure 3.

Phenolic profile of RM Z sample.

Figure 3.

Phenolic profile of RM Z sample.

Figure 4.

Phenolic profile of RM VS sample.

Figure 4.

Phenolic profile of RM VS sample.

The amount of polyphenols can be influenced by the variety, and also by the region in which the grapes were grown. This is also confirmed by Pasvanka et al. [

32]. Not only variety and region, but also other external factors such as climatic conditions, production process factors or storage conditions play an important role (Gutiérrez-Escobar et al. [

35], Lino et al.[

23], Sánchez Arribas et al. [

9].

3.3. Determination of Phenolic Substances by the UHPLC-MS/MS Method

Table 3 shows the obtained results of the quantification of individual phenolic substances. Significantly higher values of syringic acid were measured in red wine samples using the UHPLC-MS/MS method. No statistically significant difference was noted between samples of white and red varieties. Nevertheless, slightly higher values were found for samples from integrated production. Statistically insignificant, but slightly lower values for organic production were also measured in the study by Dutra et al. [

36].

A statistically significantly higher amount of

2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid was found in samples from organic production. The determination of the amount of phenolic acids was also dealt with by Kalkan et al. [

37], who analyzed 14 samples of red and white wines. The values of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid ranged widely from 0.029 mg/l to 5.89 mg/l. Similar values were recorded by Kilinc and Kalkan ( [

38] in a study of Turkish commercial wines.

Gallic acid is considered to be the dominant phenolic acid in wines regardless of vintage and region [

39]. The differences in the amount of this acid in the samples of white wines (Rhine Riesling) were statistically insignificant. The amount of gallic acid was also determined by Kumšta et al. [

40] in several Riesling samples from different regions. Their study showed that the amount of gallic acid ranged from 430 ± 0.15 µg/l to 5 170 ± 1.19 µg/l. The study by Kumšta et al. [

40] confirmed the effect of growing area on the amount of phenolic acids, including gallic acid. Significantly higher values were recorded for red wine samples, which corresponds to the results of Minussi et al. [

41]. A higher value of 3 372.99 ± 25.80 µg/l was measured in the RM Z sample from integrated production.

Table 3.

Quantification of phenolic substances by UHPLC-MS/MS.

Table 3.

Quantification of phenolic substances by UHPLC-MS/MS.

| Analyte (µg/l) |

Sample |

| RR Z |

RR VS |

RM Z |

RM VS |

| Syringic acid |

77..80 ± 6..68a

|

65..46 ± 2.87a

|

1386.91 ± 15.75b

|

1375.27 ± 40.18b

|

| 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid |

497.16 ± 0.57a

|

651.19 ± 20.92b

|

291.81 ± 1.34c

|

775.48 ± 0.60d

|

| Gallic acid |

616.13 ± 3.33a

|

638.69 ± 6.65a

|

3372.99 ± 25.80b

|

2121.39 ± 14.95c

|

| 4-hydroxybenzoic acid |

89.96 ± 4.38a

|

107.31 ± 2.72bf

|

41.15 ± 2.51c

|

96.50 ± 3.60ab

|

| Chlorogenic acid |

48.06 ± 0.76a

|

17.62 ± 1.11b

|

1.82 ± 0.20c

|

0.30 ± 0.04d

|

| Caffeic acid |

714.31 ± 11.18a

|

295.14 ± 16.48b

|

952.54 ± 6.57c

|

755.61 ± 17.71a

|

| Vanillic acid |

195.86 ± 15.03ae

|

174.29 ± 27.73a

|

1280.79 ± 86.08b

|

1689.74 ± 111.60c

|

| p-Coumaric acid |

342.43 ± 6.57a

|

73.56 ± 1.39b

|

266.31 ± 10.21c

|

205.35 ± 7.19d

|

| Ferulic acid |

130.21 ± 4.27a

|

63.18 ± 0.93b

|

91.27 ± 8.89c

|

68.25 ± 2.98b

|

| Salicylic acid |

89.91 ± 5.38a

|

68.66 ± 5.38b

|

26.85 ± 1.02c

|

58.27 ± 1.05d

|

| Quercetin |

0.09 ± 0.01a

|

0.02 ± 0.01b

|

3.37 ± 0.10d

|

0.13 ± 0.14ab

|

| Naringenin |

1.82 ± 0.04a

|

1.67 ± 0.06a

|

3.12 ± 0.11b

|

5.49 ± 0.06c

|

| Catechin |

1221.88 ± 61.54a

|

1325.81 ± 180.54a

|

35402.57 ± 34.13b

|

17133.36 ± 458.74c

|

| Naringin |

0.13 ± 0.03a

|

0.11 ± 0.01ab

|

0.22 ± 0.11a

|

0.90 ± 0.16b

|

| Myricetin |

3.34 ± 0.34a

|

2.15 ± 0.12a

|

108.31 ± 2.19b

|

171.10 ± 2.10c

|

| Hesperidin |

0.54 ± 0.05a

|

0.26 ± 0.03bc

|

0.28 ± 0.03bc

|

0.40 ± 0.04ab

|

Higher amounts of

4-hydroxybenzoic acid (

p-hydroxybenzoic acid) were measured especially in samples from organic production. However, in white varieties both in the case of BIO production and in the case of integrated, higher amounts of

p-hydroxybenzoic acid were observed. The content of this acid is influenced by the year, but the region also has a significant influence according to the study by Kumšta et al. [

40]. The amount and occurrence of this acid varies among some studies. For example, in the analyzes of the study by Franquet-Griell et al. [

42], this acid was not detected in Spanish wine samples. In Kumšta et al. [

40], the values of this acid in Riesling samples ranged from 300 ± 0.05 µg/l to 1,180 ± 0.15 µg/l, and similar amounts were also measured in Italian wine samples [

41].

The highest value of

chlorogenic acid, 48.06 ± 0.76 µg/l, was determined in the sample RR Z from integrated production. In the group of red wines, this value was again higher for integrated production than for organic, but these amounts were considerably lower compared to white wines. There have been studies in which this acid was not detected in wine samples at all [

43,

44]. Amounts greater than 2 mg/l may indicate adulteration with apple juice [

45].

Samples from integrated production contain a statistically significantly higher amount of

caffeic acid than organic samples. The values of RR Z and RR VS were compared with the values of Rieslings from the study by Kumšta et al. [

40] and the values were significantly lower. Minussi et al. [

41] analyzed several Italian wines and the amount of caffeic acid in the samples ranged from 500 µg/l to 5000 µg/l.

A significantly higher amount of

vanillic acid was found in samples of RM Z and RM VS red wines. In the case of white varieties, no statistically significant difference was noted. The wide range of values of this acid also corresponds to the studies of Minussi et al. and Kiling and Kalkan [

38,

41]. The amount of vanillic acid was also determined in Ryzlink samples from different regions of the Czech Republic by Kumšta et al. ( [

40], whose values ranged from 70 ± 0.02 µg/L to 850 ± 0.45 µg/l and 70 ± 0.03 µg/l to 1030 ± 0.43 µg/l.

The values of

p-coumaric acid measured in samples of wines from integrated and BIO production range from 18.23 ± 0.94 µg/l to 342.43 ± 6.57 µg/l, and higher amounts were recorded in both red and white samples from production integrated. Compared to the studies of Kumšta et al. ([

40], but also Minussi et al. [

41] all values are significantly lower.

In all samples,

ferulic acid was recorded and its amount ranged from 63.18 ± 0.93 µg/l to 130.21 ± 4.27 µg/l. The order of the individual samples based on the content of this acid corresponds to the order of the samples in the determination of p-coumaric acid, and even in this case these values are lower than the values obtained in the analyzes by Kumšta et al. [

40].

The highest amount of

salicylic acid, 89.91 ± 5.38 µg/l, was found in the RR Z sample, and the lowest 26.85 ± 1.02 µg/l in the RM Z sample. Minussi et al. [

41] determined salicylic acid in 7 samples of Italian wines and the resulting amount ranged from 200 µg/l to 1,000 µg/l. Pavlovic et al. [

46] analyzed 12 wine samples and the salicylic acid content in this case ranged from 350 ± 0.02 µg/l to 1,400 ± 0.01 µg/l. In a study by Nikfardjam et al. [

47], this acid was not detected in some samples, and in others it reached values of a maximum of 310 µg/l.

Quercetin was present in minimal amounts in the samples. Only in samples RM Z was its amount higher. In a study by Nikfardjam et al. [

48] quercetin was not detected in any of 6 samples of German white wines. This flavonoid is found primarily in the skin of the berries, which explains the higher values in red wine due to fermentation with the skins.

The amount of

naringenin in the samples ranged from 1.67 ± 0.06 µg/l to 5.49 ± 0.06 µg/l. No statistically significant difference was recorded between white wines. In red wines a higher amount was measured in the RM VS sample from organic production. The amount of naringenin was also determined by Sergazy et al. [

49] within the analysis of two red varieties, and their results ranged from 10 µg/l to 90 µg/l.

The amounts of

catechin in the samples are different. The highest value of 35 402.57 ± 34.13 µg/l was measured in the sample of red wine from integrated production. No statistically significant difference was noted between the white wine samples. In an analysis of individual polyphenols by Nikfardjam et al. [

48] catechin was not detected in some samples, in others it reached values of up to 6,000 µg/l (6 mg/l). Kupsa et al. [

50] confirmed the effect of the region on the catechin content in Riesling wine samples. Sergazy et al. [

49] compared the amount of polyphenols of two red varieties. Values ranged from 9.7 mg/l to 68.8 mg/l.

The amounts of

naringin are very small in all wine samples. Naringin is most abundant in citrus fruits and is responsible for the bitter taste [

51].

Regarding the amount of

myricetin, we do not observe a statistically significant difference between the white wine samples. The values of red wines correspond to the values reached by Sergazy et al. [

49]. Simonetti et al. [

52] determined the amount of polyphenols in 10 samples of red wines and 3 samples of white wines. Even in their case, a higher myricetin content was recorded in red wines.

Hesperidin is the main flavonoid in oranges and lemons [

53]. The content of this flavanone is minimal in the determined samples.

3.4. Vitamins Determination by the UHPLC-MS/MS Method

Within the determination of

vitamin C, no statistically significant difference was noted between red and white wine samples. The results found also correspond to the studies of Moreno and Peidan [

54]. Vitamin C is present in grapes at around 50 mg/l and its amount decreases during the production process, specifically during fermentation [

43]. Vitamin C enters the wine from preparations containing ascorbic acid, which are used during production to prevent unwanted oxidation and browning of the wine, while the European limit for added ascorbic acid is 150 mg/l.

It turned out that the amount of

vitamin B1 is different for the individual tested samples. A statistically significant difference was found between the samples of white wines, on the contrary, the difference in the amount of thiamine in the samples of red wines is statistically insignificant. According to Schanderl [

55], the amount is higher in wines from red varieties due to the higher presence of this vitamin in skins and seeds. However, Michlovský [

56] states the same amount of this vitamin in red and white wines, corresponding to 60 µg/l. In grapes, thiamine is most often found in the amount of 0.1 - 1 mg/l [

57] and this amount decreases radically during fermentation and the final value corresponds to 3% to 5% of the original amount [

58].

The highest amount of riboflavin (

vitamin B2) was contained in the RR Z sample from integrated production, namely 129.44 ± 2.50 µg/l. In the case of the white variety, a higher amount was recorded in the integrated production, in the case of the red variety in the BIO sample RM VS. Ribérau-Gayon et al. [

43] mention an amount of 8 – 133 µg/l for white wines, which our values correspond to, but for red wines a value in the range of 0.47 – 1.9 µg/l. Other sources report amounts of up to 100 µg/l in white wines and significantly lower in red wines [

56]. B2 found in wines is primarily a yeast product [

59]. In higher amounts, riboflavin can be the cause of aromatic defects in wines. White and rosé wines tend to be more sensitive to this defect, so yeast with a lower production of riboflavin is often used, or the amount is reduced using preparations [

60].

Table 4.

Quantity of selected vitamins.

Table 4.

Quantity of selected vitamins.

| Analyzed vitamin (µg/l) |

Sample |

| RR Z |

RR VS |

RM Z |

RM VS |

| C |

367.37 ± 71.20a

|

439.38 ± 14.42ac

|

395.31 ± 38.50a

|

418.59 ± 10.97ac

|

| B1 |

25.92 ± 1.24a

|

6.75 ± 0.25b

|

15.00 ± 0.42c

|

13.94 ± 0.33c

|

| B2 |

129.44 ± 2.50a

|

39.49 ± 0.95b

|

43.49 ± 1.36c

|

69.82 ± 1.10d

|

| B3 |

1432.62 ± 121.40ac

|

999.06 ± 69.47ab

|

1877.03 ± 101.17c

|

980.81 ± 31.13a

|

| B5 |

596.21 ± 19.77a

|

464.93 ± 9.99b

|

1159.07 ± 53.16c

|

933.60 ± 46.81d

|

| B6 |

13.15 ± 0.52a

|

– |

0.59 ± 0.11b

|

2.00 ± 0.14c

|

As part of the comparison of the results for

vitamin B3 content, no statistically significant difference was noted between the white wine samples. The amount of niacin in the sample RR VS was 999.06 ± 69.47 µg/l and in RR Z from integrated production 1432.62 ± 121.40 µg/l. The differences between the results regarding the red varieties were statistically significant, with a higher value measured for the RM Z sample, namely 1877.03 ± 101.17 µg/l. In the course of fermentation, niacin in musts is consumed by yeast, its amount decreases, and after its depletion, it is regenerated by yeast. The resulting amount is in the range of 1000 – 2000 µg/l, and this amount tends to be higher in red wines [

56].

A higher amount of pantothenic acid (

vitamin B5) was found in samples of red varieties. The highest amount of 1159.07 ± 53.16 µg/l was measured in the RM Z sample from integrated production, the lowest amount of 464.93 ± 9.99 µg/l in RR VS from organic production. Hagen et al. [

61] reported in their study that grapes contained an average of 8.5 and 6.8 mg/L pantothenic acid in red and white cultivars, however, a large decrease in pantothenic acid content in wine was observed in must during fermentation processes. The vitamin content decreases during fermentation due to consumption by the yeast, but it can also be synthesized by them. The resulting amount in wines corresponds to an average of 1,000 µg/l. During storage, this value decreases [

56].

Vitamin B6 value was not identified for RR VS sample. The most of this vitamin was measured in the RR Z sample from the integrated production, namely 13.15 ± 0.52 µg/l. The amount in the grapes is usually higher, but during fermentation there is a significant reduction in this value. Between 50 and 90% of the B6 from the grapes passes into the must, and the resulting amount in the wines represents 40% of this amount in white wines and 60% in red wines [

58].

3.5. Determination of Carbohydrates Using HPLC-ELSD Method

Saccharose is the most important transport sugar in the grape vine. Saccharose is contained both in the berries of the vine, where it is enzymatically split into glucose and fructose, but in small quantities it is also found in musts. During fermentation it is easily hydrolyzed to D-glucose and D-fructose, and it should no longer be present in wines [

1,

56]. Saccharose was not identified in our samples (

Table 5). It shows to the no addition of saccharose in the production process [

62].

Glucose is one of the residual sugars in wines, based on the amount of which wines are classified into 4 categories. In the fermentation process, glucose is preferentially fermented, so its amount in wines tends to be lower than the amount of fructose [

56]. In the RR Z, RM Z and RM VS samples, the glucose content was not proven, which may explain the minimal amount of residual sugar in these wines.

The highest amount of

fructose was recorded in the RR Z sample from ingested production. The preferential fermentation of glucose [

63] is confirmed by the zero value of glucose in the sample RR Z from integrated production, in which the highest fructose value of 8.05 ± 0.44 g/l was measured. Both samples of the red variety are representatives of dry wines, which is also confirmed by low fructose values.

Table 5.

Quantity of selected types of carbohydrates.

Table 5.

Quantity of selected types of carbohydrates.

| Analyzed carbohydrate (g/l) |

Sample |

| RR Z |

RR VS |

RM Z |

RM VS |

| Saccharose |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Glucose |

– |

0.72 ± 0.11a

|

– |

– |

| Fructose |

8.05 ± 0.44a

|

4.21 ± 0.53c

|

0.41 ± 0.06b

|

1.49 ± 0.33bd

|

3.7. Sulfur Dioxide

From a technological point of view, sulfur dioxide has fundamental importance, as it ensures the physiological-chemical and biological stability of wine. On the one hand, with antioxidant effects, that it binds molecular oxygen and thereby chemical and enzymatic oxidation. But also a part of the quality of the wine based on its anti-aldehyde effect, when sulfur dioxide binds acetaldehyde, thus spoiling the aroma of the wine. In wine, sulfur dioxide occurs in various forms [

65]. Sulfur dioxide can be present in the wine as free (HSO

3- or SO2) or linked to carbonyl and unsaturated compounds and phenols [

66]. In our study, the free and bound form of sulfur dioxide was determined during the wine analysis (

Table 7).

Table 7.

Sulfur dioxide (free form and total) content.

Table 7.

Sulfur dioxide (free form and total) content.

Analyte

(mg/l) |

Sample |

| RR Z |

RR VS |

RM Z |

RM VS |

| SO2 free |

16.45 ± 0.07 |

5.60 ± 1.56 |

11.70 ± 0.57 |

12.65 ± 0.92 |

| Total SO2 |

134.25 ± 0.64a

|

50.15 ± 2.90bc

|

29.90 ± 0.28b

|

41.25 ± 0.78c

|

No statistically significant difference was noted between the free SO2 values. The amount of free sulfur dioxide in wines should not exceed 50 mg/l, which corresponds to the lowest amount that a person can detect in wine. EU and US Directives require food manufacturers to indicate sulfur dioxide content, if it is higher than 10 mg/l at a concentration, because it is potentially toxic to the human body [

67]. Sulfur dioxide can cause an asthma attack, allergic reactions of various types in hypersensitive people, or dermatological problems [

68].

Small amounts of sulfites occur naturally in wines, but most are added to wine for the purpose of preservation or to prevent oxidation and unwanted browning. European legislation sets limits for individual wines based on color, residual sugar content and the type of farm the wine comes from. A higher amount is allowed for white wines and for wines with a higher residual sugar content. All measured values listed in the table of legislative requirements, and in all cases the limit value is not even close. Tinttunen and Lehtonen [

31] also compared SO

2 content in a study of 9 samples representing normal and organic production. In most of their samples, a higher amount was recorded for wines from normal production. However, in the case of the red variety, as in our case, a higher amount was produced organically.