Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Main Outcomes Measures

2.4. Surgical Technique

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rabinowitz, Y.S. Keratoconus. Survey of Ophthalmology 1998, 42, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Jiménez M, Santodomingo-Rubido J, Wolffsohn JS. Keratoconus: A review. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2010, 33, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes JA, Tan D, Rapuano CJ, Belin MW, Ambrósio Jr R, Guell JL, et al. Global consensus on keratoconus and ectatic diseases. Cornea 2015, 34, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollensak G, Spoerl E, Seiler T. Riboflavin/ultraviolet-a–induced collagen crosslinking for the treatment of keratoconus. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2003, 135, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhanji, V.; Sharma, N.; Vajpayee, R.B. Management of keratoconus: current scenario. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 95, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadpour M, Heidari Z, Hashemi H. Updates on Managements for Keratoconus. Journal of Current Ophthalmology 2018, 30, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashwin, P.T.; McDonnell, P.J. Collagen cross-linkage: a comprehensive review and directions for future research. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 94, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh PS, Stulting RD, Muller D, Durrie DS, Rajpal RK, Binder PS, Donnenfeld ED, Durrie D, Hardten D, Hersh P, Price Jr F. United States multicenter clinical trial of corneal collagen crosslinking for keratoconus treatment. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Abstract of Israel 2019, No. 70. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Shneor, E.; Frucht-Pery, J.; Granit, E.; Gordon-Shaag, A. The prevalence of corneal abnormalities in first-degree relatives of patients with keratoconus: a prospective case-control study. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2020, 40, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millodot, M.; Shneor, E.; Albou, S.; Atlani, E.; Gordon-Shaag, A. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Keratoconus in Jerusalem: A Cross-sectional Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 2011, 18, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netto, E.A.T.; Al-Otaibi, W.M.; Hafezi, N.L.; Kling, S.; Al-Farhan, H.M.; Randleman, J.B.; Hafezi, F. Prevalence of keratoconus in paediatric patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Shaag, A.; Millodot, M.; Kaiserman, I.; Sela, T.; Itzhaki, G.B.; Zerbib, Y.; Matityahu, E.; Shkedi, S.; Miroshnichenko, S.; Shneor, E. Risk factors for keratoconus in Israel: a case-control study. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2015, 35, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnitzky A, Ras TA. The Bedouin population in the Negev.: Abraham Fund Inititatives; 2012.

- Chorny, A.; Lifshits, T.; Kratz, A.; Levy, J.; Golfarb, D.; Zlotnik, A.; Knyazer, B. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes patients in Jewish and Bedouin populations in southern Israel. Harefuah 2011, 150, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferdi AC, Nguyen V, Gore DM, Allan BD, Rozena JJ, Watson SL. Keratoconus Natural Progression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 11,529 eyes. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickens, H.W. Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Among Minorities. Heal. Aff. 1990, 9, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Kumar, D.A.; Agarwal, A.; Basu, S.; Sinha, P.; Agarwal, A. Contact Lens-Assisted Collagen Cross-Linking (CACXL): A New Technique for Cross-Linking Thin Corneas. J. Refract. Surg. 2014, 30, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh PS, Greenstein SA, Fry KL. Corneal collagen crosslinking for keratoconus and corneal ectasia: One-year results. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011, 37, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.; Pahuja, N.K.; Nuijts, R.M.; Ajani, A.; Jayadev, C.; Sharma, C.; Nagaraja, H. Current Protocols of Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking: Visual, Refractive, and Tomographic Outcomes. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2015, 160, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinciguerra, P.; Albè, E.; Trazza, S.; Rosetta, P.; Vinciguerra, R.; Seiler, T.; Epstein, D. Refractive, Topographic, Tomographic, and Aberrometric Analysis of Keratoconic Eyes Undergoing Corneal Cross-Linking. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randleman, J.B.; Santhiago, M.R.; Kymionis, G.D.; Hafezi, F. Corneal Cross-Linking (CXL): Standardizing Terminology and Protocol Nomenclature. J. Refract. Surg. 2017, 33, 727–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kormas, R.M.; Abu Tailakh, M.; Chorny, A.; Jacob, S.; Knyazer, B. Accelerated CXL Versus Accelerated Contact Lens–Assisted CXL for Progressive Keratoconus in Adults. J. Refract. Surg. 2021, 37, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugar J, Macsai MS. What Causes Keratoconus? Cornea 2012, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AZ, Zhang J, Gokul A, McGhee CNJ, Ormonde SE. The Enigma of Environmental Factors in Keratoconus. The Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- McMonnies, C.W.; Alharbi, A.; Boneham, G.C. Epithelial Responses to Rubbing-Related Mechanical Forces. Cornea 2010, 29, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawazeer, A.M.; Hodge, W.G.; Lorimer, B. Atopy and keratoconus: a multivariate analysis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 84, 834–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, A.Y.; Vinker, S.; Bahar, I.; Kaiserman, I. The Association of Keratoconus With Immune Disorders. Cornea 2010, 29, 1261–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, V.; Karakaya, M.; Utine, C.A.; Albayrak, S.; Oge, O.F.; Yilmaz, O.F. Evaluation of the Corneal Topographic Characteristics of Keratoconus With Orbscan II in Patients With and Without Atopy. Cornea 2007, 26, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderan, M.; Jahanrad, A. Topographic, tomographic and biomechanical corneal changes during pregnancy in patients with keratoconus: a cohort study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 95, e291–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uphoff, E.; Cabieses, B.; Pinart, M.; Valdés, M.; Antó, J.M.; Wright, J. A systematic review of socioeconomic position in relation to asthma and allergic diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 46, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, S.; Davidovitch, N.; Abu Fraiha, Y.; Abu Freha, N. Consanguinity and genetic diseases among the Bedouin population in the Negev. J. Community Genet. 2019, 11, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jani, D.; McKelvie, J.; Misra, S.L. Progressive corneal ectatic disease in pregnancy. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2021, 104, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi-Saliternik, R.; Friedlander, Y.; Cohen, T. Consanguinity in a population sample of Israeli Muslim Arabs, Christian Arabs and Druze. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2002, 29, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Shaag A, Millodot M, Essa M, Garth J, Ghara M, Shneor E. Is Consanguinity a Risk Factor for Keratoconus? Optometry Vision Sci 2013, 90. [Google Scholar]

- Tamir, O.; Peleg, R.; Dreiher, J.; Abu-Hammad, T.; Abu Rabia, Y.; Abu Rashid, M.; Eisenberg, A.; Sibersky, D.; Kazanovich, A.; Khalil, E.; et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in the Bedouin population: management and compliance. Isr. Med Assoc. J. IMAJ 2007, 9, 652–655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galil A, Carmel S, Lubetzky H, Vered S, Heiman N. Compliance with home rehabilitation therapy by parents of children with disabilities in Jews and Bedouin in Israel. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001, 43, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukenik-Halevy, R.; Abu Leil-Zoabi, U.; Peled-Perez, L.; Zlotogora, J.; Allon-Shalev, S. Compliance for genetic screening in the Arab population in Israel. Isr. Med Assoc. J. IMAJ 2012, 14, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Mahrouqi, H.; Oraba, S.B.; Al-Habsi, S.; Mundemkattil, N.; Babu, J.; Panchatcharam, S.M.; Al-Saidi, R.; Al-Raisi, A. Retinoscopy as a Screening Tool for Keratoconus. Cornea 2019, 38, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Pavlatos, E.; Chamberlain, W.; Huang, D.; Li, Y. Keratoconus detection using OCT corneal and epithelial thickness map parameters and patterns. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, T.; Mrochen, M.; Seiler, T. Complication and failure rates after corneal crosslinking. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janine L, Robert H, Christiane O, Eberhard S, Pillunat Lutz E, Frederik R. Risk Factors for Progression of Keratoconus and Failure Rate After Corneal Cross-linking. Journal of Refractive Surgery 2021, 37, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng ALK, Chan TCY, Cheng ACK. Conventional versus accelerated corneal collagen cross-linking in the treatment of keratoconus. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016, 44, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloshevski, B.; Shashar, S.; Mimouni, M.; Novack, V.; E Malyugin, B.; Boiko, M.; Knyazer, B. Comparison between three protocols of corneal collagen crosslinking in adults with progressive keratoconus: Standard versus accelerated CXL for keratoconus. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 31, 2200–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporossi, A.; Mazzotta, C.; Baiocchi, S.; Caporossi, T.; Denaro, R. Age-Related Long-Term Functional Results after Riboflavin UV A Corneal Cross-Linking. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 2011, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbisan, P.R.T.; Pinto, R.D.P.; Gusmão, C.C.; de Castro, R.S.; Arieta, C.E.L. Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking in Young Patients for Progressive Keratoconus. Cornea 2019, 39, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient Characteristics | Jewish group (68 patients, 75 eyes ( | Bedouin group (98 patients, 123 eyes) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographical characteristics | |||

| Time until follow-up, months Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

17.55 ± 6.58 (57/75) 15.00 12.00;40.00 |

16.38 ± 5.14 (87/123) 14.00 12.00;34.00 |

0.256 |

| Age, years Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

23.64 ± 6.90 (75) 22.00 9.10;45.00 |

18.68 ± 6.60 (123) 18.00 7.60;41.00 |

<0.001 |

| Gender, % (n/N) Male |

77.9% (53/68) | 54.0% (53/98) | 0.002 |

| Treated eye, % (n/N) Right eye |

46.7% (35/75) | 49.6% (61/123) | 0.770 |

| Family History of KC, % (n/N) Yes |

12.1% (8/66) | 39.1% (36/92) | <0.001 |

| Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis per history, % (n/N) Yes |

18.4% (12/65) | 29.4% (28/95) | 0.138 |

| Wearing of Glasses, % (n/N) Yes |

37.1% (23/62) | 37.0% (30/81) | 1.000 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Type of CXL, % (n/N) Standard Accelerated |

32.0% (24/75) 68.0% (51/75) |

16.3% (20/123) 83.7% (103/123) |

0.013 |

| UCVA, logMAR Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

0.59±0.45 (73) 0.47 0.00; 2.00 |

0.89±0.59 (106) 0.70 0.00; 3.00 |

<0.001 |

| BCVA, logMAR Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

0.30±0.21 (73) 0.22 0.00; 1.00 |

0.45±0.24 (107) 0.47 0.00; 1.00 |

<0.001 |

| K Max, D Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

56.28±6.62 (75) 54.10 45.00; 81.40 |

58.15±8.94 (119) 56.50 44.60; 88.90 |

0.229 |

| K Mean, D Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

48.34±4.28 (75) 47.40 42.20; 62.70 |

50.24±5.87 (122) 49.40 38.70; 69.20 |

0.028 |

| MCT, μm Mean ± SD (n) Median Min; Max |

465.18±46.42 (75) 464.00 338.00; 560.00 |

434.85±49.52 (122) 436.00 244.00; 531.00 |

<0.001 |

| MCT, % (n/N) <400μm 400μm <Thickness<450μm 450μm <Thickness<500μm >500μm |

8.0% (6/75) 30.7% (23/75) 30.7% (23/75) 30.7% (23/75) |

8.0% (22/122) 41.8% (51/122) 32.0% (39/122) 8.2% (10/122) |

<0.001 |

| Clinical Parameters | Jewish group (52 Patients, 57 Eyes) | Bedouin group (71 Patients, 87 Eyes) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | >12 months | P value | Baseline | >12 months | P value | |

| (N=57) | (N=57) | (N=87) | (N=87) | |||

| UCVA (logMAR) | 0.003 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 0.57±0.44 (55) | 0.44±0.39 (52) | 0.90±0.59 (76) | 0.62±0.46 (69) | ||

| Median | 0.4 | 0.26 | 0.74 | 0.5 | ||

| Min; Max | 0.00; 2.00 | 0.00; 2.00 | 0.00; 3.00 | 0.00; 2.00 | ||

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.008 | 0.003 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 0.32±0.22 (55) | 0.23±0.21 (52) | 0.45±0.25 (79) | 0.39±0.36 (79) | ||

| Median | 0.22 | 0.2 | 0.48 | 0.3 | ||

| Min; Max | 0.00; 1.00 | 0.00; 1.00 | 0.00; 1.00 | 0.00; 2.00 | ||

| Kmax (D) | 0.981 | 0.624 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 55.80±6.02 (57) | 55.66±6.22 (57) | 57.15±7.24 (85) | 57.74±7.93 (87) | ||

| Median | 54.1 | 52.7 | 56.1 | 56.6 | ||

| Min; Max | 47.40; 72.00 | 45.60; 70.30 | 44.60; 79.60 | 46.20; 85.90 | ||

| K1 Flat front (D) | 0.257 | 0.566 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 45.87±3.42 (57) | 46.06±3.73 (57) | 48.05±5.17 (87) | 48.30±5.24 (87) | ||

| Median | 45.3 | 46 | 47.1 | 47.3 | ||

| Min; Max | 38.20; 55.70 | 37.70; 56.60 | 36.90; 66.50 | 38.80; 65.00 | ||

| K2 steep front (D) | 0.238 | 0.979 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 50.07±4.31 (57) | 49.61±4.26 (57) | 52.37±5.77 (87) | 52.65±6.11 (87) | ||

| Median | 50.4 | 49.1 | 52.5 | 51.9 | ||

| Min; Max | 42.80; 63.30 | 42.20; 65.20 | 40.50; 72.10 | 43.50; 70.80 | ||

| K mean front (D) | 0.711 | 0.391 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 47.76±3.62 (57) | 47.74±3.82 (57) | 50.00±5.31 (87) | 50.40±5.43 (86) | ||

| Median | 47.1 | 47.3 | 49.6 | 49.5 | ||

| Min; Max | 42.20; 59.20 | 40.10; 60.60 | 38.70; 69.20 | 41.40; 67.20 | ||

| K mean back (D) | 0.479 | 0.194 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | -7.41±0.82 (57) | -7.00±0.73 (57) | -7.46±0.92 (85) | -7.42±1.39 (85) | ||

| Median | -7.2 | -6.9 | -7.4 | -7.5 | ||

| Min; Max | -9.90; -6.00 | -9.60; -5.90 | -11.00; -5.60 | -10.70; 0.60 | ||

| Astigmatism front (D) | 0.125 | 0.859 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 4.18±2.57 (57) | 3.56±2.17 (57) | 4.31±2.00 (87) | 4.28±2.05 (87) | ||

| Median | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4 | 4.2 | ||

| Min; Max | 1.00; 13.70 | 0.40; 9.80 | 0.10; 11.30 | 0.00; 10.20 | ||

| Astigmatism back (D) | 0.166 | 0.104 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 0.83±0.45 (57) | 0.74±0.43 (57) | 0.89±0.38 (86) | 0.91±0.82 (87) | ||

| Median | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | ||

| Min; Max | 0.00; 2.10 | 0.10; 2.00 | 0.20; 1.80 | 0.00; 6.40 | ||

| CCT (μm) | 0.003 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 488.49±44.36 (57) | 480.64±41.09 (57) | 454.77±41.30 (85) | 440.75±56.84 (85) | ||

| Median | 484 | 483 | 454 | 442 | ||

| Min; Max | 384.00; 574.00 | 385.00; 560.00 | 356.00; 547.00 | 119.00; 609.00 | ||

| ACT (μm) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 482.19±44.36 (57) | 470.45±46.42 (57) | 448.01±41.80 (87) | 430.47±59.21 (85) | ||

| Median | 480 | 470 | 444 | 435 | ||

| Min; Max | 346.00; 542.00 | 355.00; 563.00 | 346.00; 542.00 | 108; 599.00 | ||

| MCT (μm) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 466.86±45.96 (57) | 453.19±50.12 (57) | 434.70±44.04 (87) | 418.54±45.69 (86) | ||

| Median | 463 | 460 | 432 | 423.5 | ||

| Min; Max | 338.00; 560.00 | 277.00; 541.00 | 339.00; 531.00 | 297.00; 517.00 | ||

| Corneal volume (mm3) | 0.003 | 0.004 | ||||

| Mean+sd (n) | 57.32±4.84 (57) | 56.68±4.74 (57) | 55.98±3.96(85) | 55.11±4.68 (87) | ||

| Median | 57.4 | 56.6 | 55.3 | 55.2 | ||

| Min; Max | 35.60; 68.70 | 34.60; 66.70 | 48.30; 68.20 | 30.50; 66.00 | ||

| Change (calculated as 12+ months post procedure minus at baseline) | Jewish group (52 Patients, 57 Eyes) | Bedouin group (71 Patients, 87 Eyes) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCVA (logMAR) | 0.56 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.12±0.35 (52) | -0.23±0.53 (66) | |

| Median | -0.17 | -0.11 | |

| Min; Max | -1.00; 1.40 | -2.00; 0.90 | |

| BCVA (logMAR) | 0.864 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.07±0.21 (50) | -0.08±0.29 (73) | |

| Median | -0.02 | -0.02 | |

| Min; Max | -0.80; 0.60 | -0.78; 1.00 | |

| Kmax (D) | 0.973 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.16±2.45 (56) | 0.09±2.14 (84) | |

| Median | 0 | 0.1 | |

| Min; Max | -4.40; 8.60 | - 8.60; 7.00 | |

| K1 Flat front (D) | 0.588 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | 0.18±2.02 (57) | 0.25±1.9 (87) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | |

| Min; Max | -10.40; 4.70 | -3.20; 11.70 | |

| K2 steep front (D) | 0.35 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.45±3.01 (57) | 0.28±3.10 (87) | |

| Median | -0.2 | 0 | |

| Min; Max | -19.00; 7.60 | -5.10; 22.90 | |

| K mean front (D) | 0.776 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.02±2.40 (57) | 0.33±2.24 (86) | |

| Median | 0 | 0.1 | |

| Min; Max | -14.00; 6.60 | -3.60; 12.80 | |

| K mean back (D) | 0.747 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.02±0.31 (57) | 0.08±8.65 (83) | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | |

| Min; Max | -1.30; 1.10 | -1.70; 6.95 | |

| Astigmatism front (D) | 0.327 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.61±2.18 (57) | -0.02±1.65 (87) | |

| Median | -0.3 | 0 | |

| Min; Max | -8.60; 4.50 | -7.10; 4.90 | |

| Astigmatism back (D) | 0.932 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.08±0.37 (57) | 0.03±0.8 (86) | |

| Median | -0.1 | -0.05 | |

| Min; Max | -1.50; 0.60 | -0.90; 5.00 | |

| CCT (μm) | 0.639 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -7.84±19.24 (57) | -14.92±45.77 (83) | |

| Median | -11 | -10 | |

| Min; Max | -57.00; 40.00 | -344.00; 93.00 | |

| ACT (μm) | 0.733 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -11.73±18.52 (57) | -18.04±44.02 (85) | |

| Median | -12 | -11 | |

| Min; Max | -60.00; 35.00 | -333.00; 92.00 | |

| MCT (μm) | 0.686 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -13.67±19.78 (57) | -16.6±24.94 (86) | |

| Median | -13 | -15 | |

| Min; Max | -83.00; 39.00 | -98.00; 27.00 | |

| Corneal volume (mm3) | 0.896 | ||

| Mean+sd (n) | -0.63±1.63 (57) | -1.02±3.63 (85) | |

| Median | -1 | -0.6 | |

| Min; Max | -4.60; 3.40 | -27.50; 3.90 |

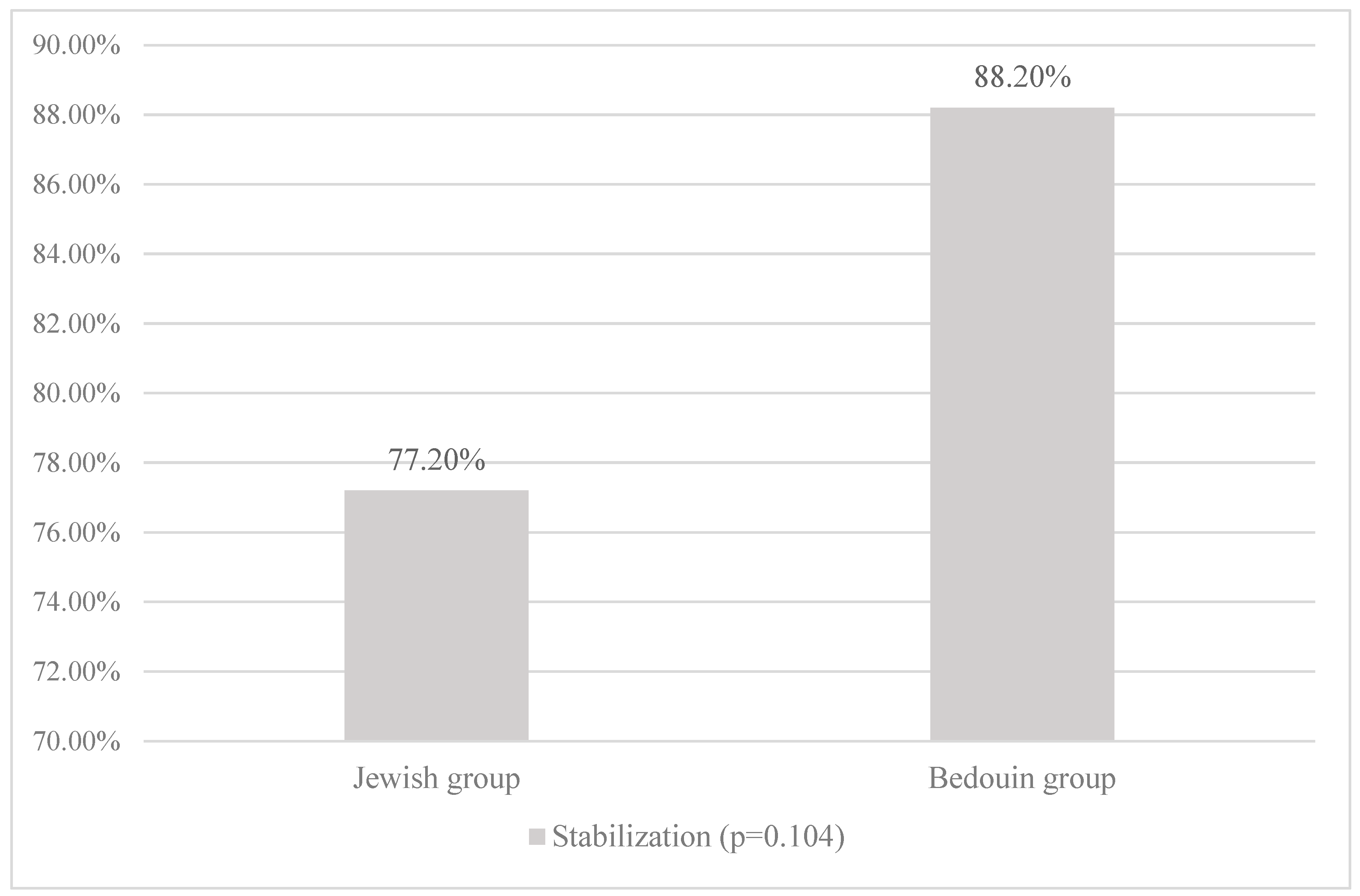

| Patient Characteristics | RR | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval (RR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Kmax < 55 at baseline | 1.24 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.39 |

| MCT > 450 at baseline | 1.08 | 0.171 | 0.96 | 1.23 |

| Standard CXL procedure | 1.14 | 0.041 | 1.01 | 1.31 |

| Jewish origin | 1.05 | 0.472 | 0.92 | 1.19 |

| Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis per history | 1.06 | 0.486 | 0.91 | 1.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).