1. Introduction

Speaking about of ancient Egyptian mathematics, it is impossible to pass by its famous riddle.

The matter of that the Egyptians considered a circle’s area (

S) to be equal to the area of the square, the side of which is 8/9 of circle’s diameter (

d), i.e. believed in modern designations,

Similar calculations are available in Moscow Mathematical Papyrus that dated to around 19th century BC [

1] and Rhind Mathematical Papyrus that dated roughly 17th century BC (but it is probably a copy of an older document) [

2].

This formula is characterized by amazing accuracy. If to consider that the ratio of a circle’s circumference (

L) to its diameter

the result is really very good: it exceeds the exact value (number π) 3.14159..., less than 0.02 (in other words, an error less than 1%) [

3]. But the answer to the question of how this result was obtained, has not yet been.

Various hypotheses have been proposed [

4,

5], but all of them are unconvincing.

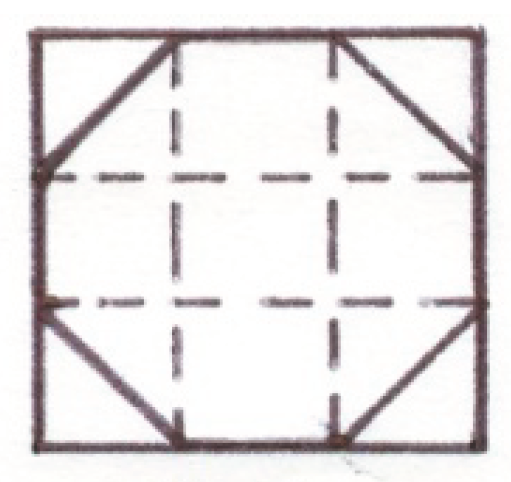

The most reasonable is the assumption (put forward at the beginning of the 20th century) that the Egyptians divided the square into 9 parts, cut corners and get the right octagon the area of which is

d2 –

2/

9 d2, i.e. is 7/9 square area [

6], as can be seen in

Figure 1.

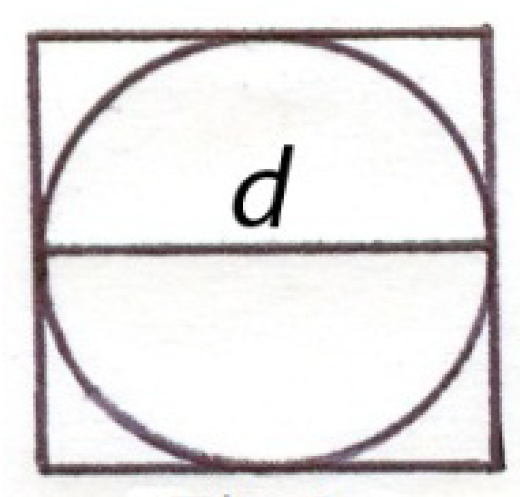

The area of the octagon close to the area of circle inscribed inside a square (

Figure 2) and is approximately equal to the area of square with the side 8/9 of the circle’s diameter, because 7/9 = 63/81 ≈ (8/9)

2. However, the researchers could not understand how the Egyptians came from the expression

d2 –

2/

9 d2 to the expression (

d –

1/

9 d )

2.

Here we reconstruct the ancient Egyptian method, in modern designations.

2. Method

At first, the Egyptian scientist have determined that an arbitrary square with side

d has the area (

Sq) is equal to:

where

P = 4

d is the perimeter of a square.

Then he drawed in the square the circle with a diameter equal to the side of the square (

Figure 2) and he found that the circle’s circumference is smaller than the perimeter of the square, and the circle area is smaller than the square area:

Substituting in formula (3)

L instead of

P, he obtained that the area of the circle

or

where

d ∙

d = 1 is the square’s area (in

Figure 2).

Hence, the ratio of the circumference to the diameter is equal to:

Thus, to calculate the area of a circle

it is necessary to know the ratio of the circumference length to the diameter (

L/

d). Using a strip of papyrus and a round flat object (such as a disc or wheel), the ancient researcher was able to determine

by direct measurement that this relationship lies approximately in the middle between the values 3 +

1/

4 and 3 +

l/

9:

Substituting in formula (7) the octagon’s area 7/9 instead of the circle’s area S, he obtained 4∙7/9 = 28/9 = 3 + 1/9 and made sure that the value of 7/9 for the area of the circle is not suitable.

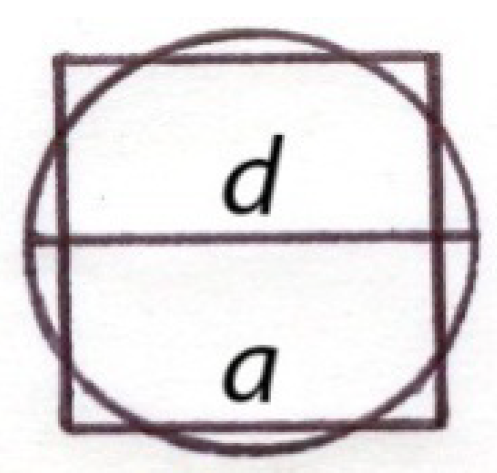

Next, our scientist draws a square with an area equal to a given circle,

Sq =

S (

Figure 3). He sees that the square’s side (

а) is slightly smaller than the circle’s diameter (

a <

d), perhaps, it different from the diameter that is taken as

the unit of length (

d = 1), at 1/10, or 1/9, or 1/8:

Therefore, the square’s side is one of the following values from the circle’s diameter:

The areas of the circle and the square (in

Figure 3) the same,

S =

a ∙

a, so researcher receives from equation (7):

Sequentially substituting in the last formula instead of the square’s side

a its values (9/10, 8/9, 7/8), he calculates:

Thus, the unknown mathematician came to the conclusion that

the empirical condition (8)

is satisfied the value L/

d = 3 +

1/

6 , from where

a = (8/9)

d and the area of the circle is (

8/

9 d )

2 [

7].

3. Conclusion

Ancient Egyptians first proposed a mathematical method for calculating the circle’s area and the ratio of a circumference to diameter. This method is characterized by excellent accuracy, simplicity and elegance.

Footnote: This article is registered as an object of copyright in the Intellectual Property Office of Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyzpatent) in November 2008 (Certificate № 1162).

References

- V.V. Struve and B.A. Turaev, Mathematischer Papyrus des Staatlichen Museums der Schönen Künste in Moskau. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Mathematik, Abteilung A: Quellen, Vol. 1. (Heidelberg: J. Springer, 1930).

- T.E. Peet, The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus. British Museum10057 and 10058, London: The University Press of Liverpool limited and Hodder - Stoughton limited (1923).

- B.van der Waerden, Science awakening, Groningen: Wolters, 1954, p. 32.

- H. Engels, Quadrature of the circle in Ancient Egypt, Historia Mathematica, 4(2) 137–140 (1977). [CrossRef]

- P. Gerdes, Three alternate methods of obtaining the ancient Egyptian formula for the area of a circle, Historia Mathematica, 12(3) 261–268 (1985). [CrossRef]

- O. Neugebauer, Lectures on the history of ancient mathematical sciences, Moscow-Leningrad, 1937, pp. 140–141 [in Russian]. Available online: http://www.astro-cabinet.ru/library/Neigebauer/N_Lek_Ogl.htm.

- A.B. Abdukadyrov, Physics – unity in diversity, Bishkek, 2008, pp. 3–5 [in Russian].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).