1. Introduction

Creativity is a cognitively complex process that generates novel and valuable ideas, solutions, and products. It is essential in numerous facets of human life, including academic performance and education. Creativity as a means of enhancing academic performance is gaining increasing attention in research and education.

Several brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and default mode network, have been linked to creative thought in neurocognitive studies of the brain processes underlying creativity. These regions are associated with various cognitive functions, such as ideation, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving.

The relationship between creativity and academic achievement is complex and can vary depending on the context and the specific measures of creativity and academic achievement employed in the studies. Here are some potential influences of creativity on academic performance:

Enhanced Problem-Solving: Through creative thinking, students can approach problems in novel ways and generate inventive solutions. This can be especially beneficial in subjects that require solving complex problems, such as mathematics and science.

Enhanced Learning and Memory Consolidation: Creative activities can improve learning and memory consolidation. When students actively engage in creative tasks related to the topic, they may better comprehend and retain the information. Incorporating creative elements into the instructional process can increase student motivation and engagement. Students become more invested in their studies when encouraged to explore and express their ideas creatively.

Communication and Expression: Creativity can improve both written and verbal communication skills. Students who can express themselves creatively may excel in subjects that require effective communication, such as literature, writing, and the arts.

Engaging in creative activities can aid in reducing stress and anxiety, which can positively affect academic performance.

Recognizing that the connection between creativity and academic performance can be complex is essential. Creativity can have positive effects, but an imbalanced emphasis on creative activities at the expense of traditional academic subjects can have negative consequences.

According to [

1], creativity is a complex and multifaceted process that involves identifying information gaps, formulating hypotheses about them, analyzing and testing them, and communicating the results to solve problems and promote environmental changes. According to research findings, creativity is also associated with school performance and academic accomplishments, such as arithmetic, writing, and reading [

2,

3,

4]. In addition, juvenile creativity undergoes various developmental changes, including a decline during elementary school [

5]. Characteristics such as acquired knowledge, methods of thinking, verbal and language skills, types of stimulation, and motivation are also responsible for a child’s creativity performance throughout his or her development [

6]. It also appears to be associated with reading, critical thinking, reasoning, creativity, and freedom of expression [

7]. Lastly, thinking and creating original products and new ideas are among the skills that distinguish humans from other living objects and have brought them to their current position. According to this meta-analysis, creative ability is a component of the school experience and the development of cognitive skills, as well as a factor that promotes excellent academic performance [

8].

According to several researchers, creativity and learning entail change and have fundamental parallels [

2,

9,

10,

11]. Specifically, creativity is associated with novel and significant modifications to ideas, goods, and behaviors. Similarly, learning is characterized by relatively stable changes in comprehension and conduct [

9,

10,

12,

13]. It seems reasonable to presume a positive relationship between creativity and academic success, which is viewed as the result of learning.

An earlier study [

14] revealed that sixth graders’ creative abilities were more closely related to reading than mathematics. Another German study examining the relationship between student creativity and academic achievement (teacher-determined grades) reached similar conclusions, namely that creativity is most strongly associated with academic achievement in social studies (e.g., history and political science) and less so with academic achievements in language learning (German and English) or mathematics and natural sciences [

15,

16]. Some researchers [

17] discovered positive correlations between students’ creativity and academic performance in earth sciences, geography, Spanish, and chemistry.

In addition, the neurocognitive profile of creativity can be studied beyond education and the enhancement of academic performance and within the psychology of individual differences, as it can be related to the parameter of leadership [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], clinical psychology, as it can be studied in the context of therapy and psychopathology [

23], as well as in special minority groups [

24]. All the parameters as mentioned above are evaluated in the subsequent.

More specifically, the neurocognitive profile of leadership creativity refers to the underlying brain processes and cognitive mechanisms that contribute to the creative thinking and problem-solving abilities of influential leaders [

18,

20]. Creativity plays a vital role in enabling leaders to navigate complex challenges, innovate, and inspire others, despite the fact that leadership is a multifaceted concept involving various traits and skills [

21,

22]. The neurocognitive profile of leadership creativity is comprised of cognitive skills, emotional intelligence, and the capacity to foster a creative and collaborative environment. These characteristics enable leaders to think critically, adapt to changing conditions, and motivate their teams to produce innovative solutions and superior results. Consequently, creativity is central to effective leadership across a variety of domains and industries.

The neurocognitive profile of creativity in gamification refers to the cognitive processes and brain mechanisms engaged when individuals engage in creative activities in the context of gamified experiences. Gamification incorporates game elements and mechanics into non-game contexts to improve user engagement, motivation, decision-making, and overall experience [

25]. Gamification can cultivate an environment that encourages innovative thought and problem-solving when combined with creativity [

26].

Understanding the neurocognitive aspects of creativity in gamification enables designers and educators to create more engaging and effective gamified experiences that harness the power of creativity to improve learning, problem-solving, and overall user satisfaction [

27]. By tapping into the brain’s cognitive processes associated with creativity, gamification can become a potent instrument for stimulating innovative thought and fostering an enjoyable learning or interactive environment [

28].

More specifically, the neurocognitive profile of creativity in therapy refers to the underlying brain processes and cognitive mechanisms at play when people engage in creative activities as part of the therapeutic process. Clinical psychology frequently employs creative approaches to therapy, which can provide clients with unique advantages and opportunities to investigate and express themselves in novel and imaginative ways. Incorporating creativity into therapy can enhance the therapeutic process by engaging various brain regions and fostering emotional expression, insight, and personal development. Recognizing the diverse ways creativity can contribute to the healing and transformational process, therapists who use creative approaches customize interventions to each client’s needs and preferences [

29].

While creativity is typically associated with improved academic performance, the relationship between creativity and academic performance in people with psychopathology can be influenced by several factors. It is essential to recognize that despite their difficulties, individuals with psychosis can exhibit remarkable resilience and fortitude. Integrating supportive interventions, cognitive remediation, and creative therapies into academic programs may improve this population’s cognitive performance, creative expression, and academic performance.

Due to the complexity of psychosis and its varied effects on individuals, research in this field is constantly evolving. Further research is required to comprehend the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying creativity in people with psychosis and how creative interventions can be effectively integrated into educational settings to enhance academic outcomes. In addition, the treatment and support of individuals with psychosis should be comprehensive, considering their unique strengths, obstacles, and personal objectives [

30]. In both a correctional facility and special population settings, it is essential to embrace a holistic approach that recognizes each individual’s unique needs and challenges [

31]. Trauma, psychological health, and social support are essential to their cognitive and academic abilities [

32,

33]. Individualized interventions, such as creative therapies, educational programs, and vocational training, can positively affect cognitive abilities, creative expression, and academic performance as a whole [

34].

This systematic review aims to investigate whether there is a correlation between creativity and academic capabilities and with which of the academic abilities this correlation is usually found. The research sample includes published scientific articles in valid and recognized scientific journals investigating the relationship between creativity and academic skills in different countries and cultures.

2. Materials and Methods

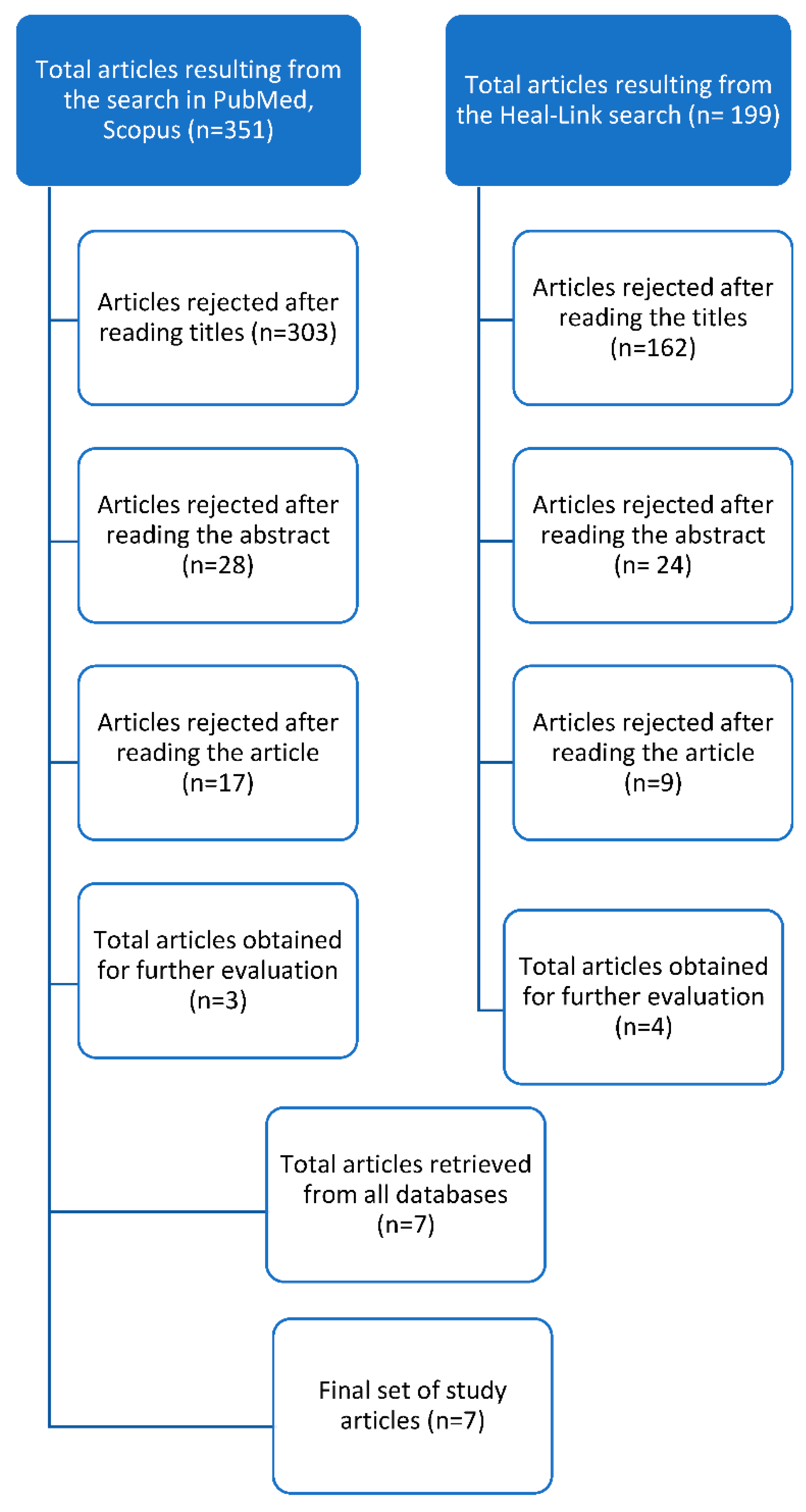

This is a systematic review of the literature carried out using the search terms “creativity, intelligence, academic achievement, learning, students, reading, understanding” in bibliographic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Heal-link) and their synonyms and combinations.

For an article to be included in the study, it had to meet the following criteria: (1) it had to be a scientific article, (2) it had to be written in English, (3) it had to be germane to the topic of the study, and (4) its sample had to include students aged 5 to 16 with normal, typical development. (5) be published between 2016 and 2022, (6) be published in a reputable scientific journal, (7) the article is a research or longitudinal study, (8)) to be in the field of psychology, (9) to be exhaustive, and (10) to be freely accessible.

The Picos (Population, Interventions, Controls, Outcomes, Study design) method was utilized as a criterion for including articles in this study. Articles were included in the search if their country had a population of students up to 16 with standard, typical development, and no diagnosed developmental disorders who attended public schools. Children’s creativity should have been evaluated using a recognized creativity assessment test, such as the Torrance Creative Thinking Test modified for each country’s population, the Dimension Change Card Sort, the Consensual Assessment Technique, or the Aurora battery.

After searching the databases for the articles and implementing the filters, 550 articles were retrieved. After evaluating these, seven articles emerged. After acquiring the bibliography and evaluating the articles based on criteria, duplicate articles were identified and removed from all search results from the three databases. Then, the titles of the articles were evaluated, and those incompatible with the purpose of the systematic review were excluded. The abstracts of the remaining studies were subsequently read, and those that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria were discarded. The full texts of the studies that were discovered as a result of the previous search were examined, and those that needed to provide the necessary information regarding the subject and purpose of the review were eliminated. The methodology and quality of the studies were evaluated, and those that met the eligibility requirements were chosen (

Figure 1).

3. Results

Researchers from various nations and cultural origins published the articles (n=7). In particular, the articles originated from Natal, Brazil, Rwanda, East Africa, the Midwest of the United States, Iconium, Turkey, Wales, England, Beijing, China, and cities in Northern England. In 2022, four of these studies were published, compared to just one in 2016, 2020, and 2021. The studies were published in prestigious English-language scientific journals. Six research projects were funded—two longitudinal, one cohort, two descriptive, and two explorative studies (

Table 1).

In all studies, evaluations were conducted on children attending public institutions with the consent of both parents and school personnel. Year of publication, country of origin of researchers, year/duration of implementation, funding, research design, purpose, sample, instruments, results, and conclusions were extracted from each study.

Regardless of children’s previous academic performance, [

37] published a longitudinal study evaluating the contribution of creativity to future academic performance. The research sample consisted of 1165 seventh-grade students from six schools in England. The researchers used the five “Aurora battery” subtests to evaluate creative and practical abilities to conduct their research. In particular, subtests were administered to evaluate verbal (conversations and figurative language), numeracy (animated numbers), and figurative creativity (book covers and multiple uses). In addition, Key Stage (KS2) tests were administered to evaluate pupil achievement after completion of certain educational stages.

Furthermore, at age 16, the English, mathematics, and science ratings from the general secondary school certificate were considered. Regarding the procedure, KS2 scores were collected in 2006, Aurora was awarded two years later in 2008, and its scores were examined in conjunction with GCSE scores four years later in 2012. Multiple (domain-specific) creativity factors represented the Aurora subtest scores less accurately than a single (general) creativity factor. Thus, it was determined that the subtests assessed a standard set of general creativity skills but independently evaluated a distinct set of creative skills.

In addition, creativity could be used to predict GCE scores independently of KS2 scores. According to the researchers, this result was based on the fact that the creative skills assessed by Aurora are distinct from the academic skills measured by KS2 and may have contributed more to the long-term prediction of GCSE performance four years later. Independent of other academic abilities, the researchers discovered that a general form of creativity contributes to future academic performance.

In 2020, researchers [

41] examined the relationship between creativity and academic achievement, as well as gender differences in this relationship, among Beijing, China’s upper primary school pupils. 8 to 15-year-old Beijing fourth, fifth, and sixth-graders from four primary public institutions participated in the survey. Children’s creativity was evaluated using the Chinese variant of the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT). In addition, the researchers created a survey to capture the students’ personal information. Students’ academic achievement was determined by their final semester grades, which professors or a faculty commission evaluated. The correlation between student creativity and academic achievement was found to range from weak to moderate in the study’s findings. The five creativity subtest scores (originality, fluency, elaboration, abstract titles, and resistance to premature closure) were significantly and positively related to students’ Chinese performance, whereas only four of the subtest scores (fluency, originality, resistance to premature closure, and abstract titles) were significantly related to students’ mathematics achievement. In addition, boys and girls performed notably differently on assessments of creativity. Specifically, boys outperformed girls in originality, whereas girls outperformed boys in abstract title usage. Also, processing and using abstract title scores were considerably correlated with girls’ Chinese and mathematics academic achievement.

In contrast, for boys, resistance to early closure was associated with their academic performance in Chinese and mathematics. In contrast, originality and use of abstract titles were only associated with their academic performance in Chinese. The researchers concluded that students’ creativity was significantly and positively correlated with their academic achievement and that females’ creativity tended to be adaptive. Simultaneously, males demonstrated both innovative and adaptive creativity.

Some other researchers [

40] conducted a longitudinal study to examine the relationship between nine-year-old children’s creativity and educational achievement, regardless of the student’s intellect or motivation. The sample consisted of 1,306 twin children from Welsh and English institutions. The inclusion criterion for the study was data from children’s written accounts between the ages of nine and sixteen. The Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT) was used to code the creativity and nine other dimensions of 9-year-old children’s home-written stories under the supervision of their parents and guardians. The CAT measures creativity in shared creative products like children’s written stories. On a seven-point scale with ten criteria, children’s stories were evaluated: creativity, likeability, novelty, imagination, logic, emotion, grammar, detail, vocabulary, and straightforwardness. Verbal and non-verbal tests were used to assess intelligence at age 9, such as the Vocabulary and General Knowledge tests from the WISC-III and the Figure Classification and Shapes tests from the Cognitive Abilities Test 3. The motivation to write at age nine was assessed with two questions to parents/guardians and children. Teachers assessed educational attainment at ages nine and twelve by recording current achievement in grammar, spelling, and writing, and educational attainment at ages nine and thirteen was assessed by teachers by recording current achievement. According to the research, creative expression and writing motivation at age 9 were not significant predictors of academic achievement.

In contrast, logic, intellect, and ninth-grade English writing grade were significant predictors for all children. However, in the second half of the sample, the finding that logic at age 9 is a statistically significant predictor of English writing at age 12 was not replicated. In addition, creative expressiveness, as a measure of creativity, explained variance in English scores across time independent of children’s intellect and motivation. In addition, the study revealed moderate genetic and environmental influences on writing creativity at age 9. This study also revealed some intriguing gender distinctions. At nine, females scored higher than boys on tests of creative expression and reasoning, writing motivation, and English writing grades. Even in adolescence, the researchers concluded that creativity in children’s writing is associated with academic achievement.

In a 2022 descriptive study, researchers [

39] examined the relationship between creative thinking and Turkish pupils’ reading and listening comprehension levels, thereby attempting to demonstrate a connection between language and thought. The research sample comprised 380 seventh-graders from eight public schools in the Iconium Province of Turkey. The only baseline for the study was the seventh grade because the researchers wanted to examine the development of abstract processing and creative thinking abilities, which develop by age 11. Students’ reading comprehension skills were evaluated with the Reading Comprehension Achievement Test (RCAT), their auditory comprehension skills with the Auditory Comprehension Achievement Test (LCAT), and their creative thinking with the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT). Pearson correlation analysis was utilized for the data analysis. The survey results indicated that secondary school students’ reading and listening comprehension levels are average. The correlation between reading comprehension and auditory comprehension is statistically significant, while the correlation between reading comprehension and fluency, a subdimension of creativity, is the least significant. In addition, there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between listening comprehension and creative thinking scores. There was also a positive and significant correlation between reading and auditory comprehension. Finally, a correlation between reading comprehension and creative thinking abilities appears. All association trends were statistically significant, according to the researchers’ findings. Therefore, they believe it necessary to encourage students to develop a positive attitude toward reading, listening, and writing and exercise reading and writing to foster and develop their creative thinking.

In 2022, other researchers [

38] studied the relationship between first-grade students in the Midwestern United States and their creativity. The survey included 141 students, with a mean age of 6.19 years, from two schools with comparable demographic characteristics in the Midwestern United States. The research was conducted using the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking-Figurative (TTCT-F) to measure students’ creativity and the Northwest Evaluation Association-Measure of Academic Progress-development (NWEA-MAP-Growth) to evaluate students’ achievement development in math and reading over time. In order to conduct the research, permission was sought from the student’s parents, who were notified via electronic newsletter and regular mail and gave their assent. Research revealed a correlation between all TTCT-F scores and academic achievement, including math and literacy. This suggests that even kindergarten and first-grade students exhibit the exact relationships between creativity and academic achievement as older students. In addition, students who can better comprehend stimuli or generate original ideas are more likely to demonstrate academic success. However, no significant correlations between academic development and TTCT-F scores were discovered. However, grade level substantially influenced the relationship between creative thinking processes and academic growth in reading and mathematics, with kindergarteners exhibiting significantly more significant growth than first graders. Inferred from the foregoing, the study demonstrates significant positive relationships between TTCT-F performance and static academic achievement scores in reading and mathematics. However, the correlation with academic growth scores could have been more precise.

In 2022, researchers [

35] conducted a cohort study with measurements in grades 1 and 4 on cognitive flexibility based on adaptive skills, such as problem-solving and creativity, in low-resource school-attending Rwandan students. Three hundred six children ages 7-8 and 10-11 from primary institutions in Kigali, Rwanda, as well as informal settlements and villages, participated in the study to determine the population’s poverty index. The Dimension Change Card Sort (DCCS), which assesses the classification of primarily colors and shapes, and the Flexible Item Selection Task (FIST), which measures flexibility in selection and object matching, were used to evaluate children’s cognitive flexibility. The Object-based Pattern Reasoning Assessment (OPRA), which assesses non-verbal reasoning through the recognition of patterns in sequences, four literacy activities were used to assess reading, which was selected from validated context-adapted reading assessment tools and in the Rwandan language, and self-made questionnaires were used to assess the student’s personal and socioeconomic characteristics. Several factors demonstrated significant correlations with students’ cognitive flexibility, as demonstrated by the research findings. On measures of cognitive flexibility, literacy, and nonverbal reasoning, Grade 4 students scored substantially higher than Grade 1 students. This was true for both literacy and nonverbal reasoning assessments.

Even after controlling for background variables, significant differences were found in the cognitive flexibility of Rwandan students across schools. In addition, the family structure appeared to significantly affect cognitive flexibility, as children from single-parent families performed better than pupils from nuclear families, despite living in more modest homes and consuming fewer protein-rich foods. The most significant finding of this study is the correlation between cognitive flexibility and other learning outcomes among Rwandan children, as cognitive flexibility predicts non-verbal reasoning. In addition, limited evidence of a correlation between cognitive flexibility was discovered. Due to their limited exposure to print and written materials before entering the classroom, 7- and 8-year-olds need help with adaptability and literacy skills. The correlations between cognitive flexibility and reading and language skills appeared more stable and dependable among fourth graders. The researcher concludes that curricula based on fostering abilities that enhance creativity and problem-solving are the foundation for enhancing academic accomplishments and developing skills to adapt to changing conditions.

Additionally, researchers [

36] conducted an exploratory study on the relationship between creativity and reading, phonological awareness, and decoding skills. The sample consisted of 75 children of both sexes in grades 1 (6-7 years), 2 (7-8 years), and 3 (8-9 years) from public elementary institutions in Natal, Brazil. The method’s selection criteria required candidates to be in grades 1 to 3 at a primary school in Natal. In contrast, exclusion criteria included history or diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorder and hearing, vision, and movement disorders. The Brazilian Figural Creativity Test (TCFI), which measures creativity through numbers, was used to evaluate the abovementioned abilities. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI), adapted for the Brazilian territory, the Phonological Awareness – Sequential Assessment Tool (CONFIAS), which measures phonological awareness, and the Reading Assessment of Words and Pseudowords Isolated (LPI), which measures children’s reading of words and pseudowords. All parents and custodians were informed and provided written consent for their children’s participation. Children were withdrawn individually from the classroom for three 40-minute assessment sessions in a room with minimal distractions. The results indicated that creativity did not appear to develop, as expected by the researchers based on the available literature, and that there were no significant differences between school years. No significant distinctions between the first and second grades regarding phonological awareness performance existed. On the LPI, all divisions had relatively low performance. However, their performance improved as the number of students in a class increased. Also, significant all-grade correlations were found between verbal tests, executive functions (intelligence assessment), and creativity, and these correlations increased over time, even when intelligence and creativity indices were below average.

Regarding the relationship between creativity, reading, and phonological awareness, it was observed that correlations between creativity, phonological awareness, and reader decoding were weak regarding significance and effect size in the first and second years. In contrast, the correlations in the third year ranged from moderate to robust. These disparities are likely the result of the first- and second-graders immature development. It was discovered that creativity in reading allowed for the development of cognitive skills, including language, imagination, freedom of expression, and cognitive and linguistic abilities. The researchers determined that creativity was related to skills such as literacy and intelligence in all three grades, with the strongest correlations occurring in third grade.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that creativity is associated with performance. According to the studied research data, overall creativity contributed to academic performance independently of other academic skills. In addition, it was discovered that adaptive creativity promotes academic performance for females, whereas both innovative and adaptive creativity is valuable for boys. Creativity is detectable in children’s writing and serves as a predictor of future academic success. Finally, a correlation between reading and listening aptitude and creativity and mathematics was identified.

The study provides several insights into the associations between creative thought processes and academic success. However, several limitations will influence future research. First, the sample size of the research studies could have been greater, rendering it impossible to generalize the results to a wide range of students from various nations. In addition, correlations between creativity and educational achievement were moderate in some studies. It is emphasized that various academic subjects and capabilities were not evaluated. The research articles, however, were limited to specific creativity-related skills, such as reading, writing, and mathematics.

Given the limitations outlined above, it is recommended that additional research be conducted to evaluate the contribution of creativity to the enhancement of skills in an educational context. It is considered necessary to conduct systematic reviews, which should include research employing other variables, such as the children's personality, the social and economic context of their development, and the characteristics of their families, to investigate this relationship. In addition, future research should seek to comprehend the function of creativity in learning, considering classroom-level variables. Finally, it is essential to investigate the potential effects of creativity deprivation in educational contexts on academic performance.

Levels of creativity have a predictive and cumulative effect on future academic performance. Therefore, it is essential to recognize and encourage creativity in education and to provide opportunities for the expression and development of creativity, which can lead to new educational and professional development opportunities for students.

5. Conclusions

The neurocognitive profile of creativity influences academic performance positively through multiple cognitive, emotional, and motivational mechanisms. Integrating creative approaches into educational practices may improve students' problem-solving skills, motivation, and engagement and reduce their stress levels. However, the precise nature of these effects may vary based on the situation and the individual. As neuroscience and education continue to develop, additional research is required to understand the relationship between creativity and academic achievement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and E.G.; methodology, M.T.; formal analysis, M.T.; investigation, M.T.; resources, M.T. and E.G.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, M.T., E.G. and C.H.; visualization, E.G. and C.H.; supervision, E.G.; project administration, E.G; funding acquisition, C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Torrance, E. P. (1993). Understanding creativity: Where to start? Psychological inquiry: An International Journal for the Advancement of Psychological Theory, 4(3), 232–234. [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A., Karwowski M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2017). Creativity and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(2), 269-299. [CrossRef]

- Leopold, C., Mayer, R. E., & Dutke, S. (2019). The power of imagination and perspective in learning from science text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 793–808. [CrossRef]

- Bart, W. M., Can, I., & Hokanson, B. (2020). Exploring the relation between high creativity and high achievement among 8th and 11th graders. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 7(3), 712–720.

- Urban, K. K. (1991). On the development of creativity in children. Creativity Research Journal, 4(2), 177–191. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. H., Cheng, Y., Ip, H. M., & McBride-Chang, C. (2005). Age differences in creativity: Task structure and knowledge base. Creativity Research Journal, 17(4), 321–326. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Meintani, P.M., Dimakos, I. (2021). Neurocognitive and Emotional Parameters in Learning and Education Process. 14th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, 8th- 10th November, Seville, Spain. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Dimakos, I. (2022). An Overview of Cognitive Neuroscience in Education. 14th Annual International Conference on Edu.cation and New Learning Technologies, 4 th – 6 th July, Mallorca, Spain. [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R.A. (2016). Creative learning: A fresh look. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 15, 6– 23. [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.A., & Chand, I. (1995). Cognition and creativity. Educational Psychology Review, 7, 243– 267. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.K. (2012). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation ( 2nd edn). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Alexander, P.A., Schallert, D.L., & Reynolds, R.E. (2009). What is learning anyway? A topographical perspective considered. Educational Psychologist, 44, 176– 192. [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. (1999). A propulsion model of types of creative contributions. Review of General Psychology, 3, 83– 100. [CrossRef]

- Cicirelli, V.G. (1965). Form of the relationship between creativity, IQ, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 56, 303– 308. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Gkintoni, E., Katsibelis, A. (2022). Application of Gamification Tools for Identification of Neurocognitive and Social Function in Distance Learning Education. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(5), 367–400. [CrossRef]

- Freund, P.A., Holling, H., & Precel, F. (2007). A multivariate multilevel analysis of the relationship between cognitive abilities and scholastic achievement. Journal of Individual Differences, 28, 188– 197. [CrossRef]

- Niaz, M., Núñez, G.S.D., & Pineda, I.R.D. (2000). Academic performance of high school students as a function of mental capacity, cognitive style, mobility–fixity dimension, and creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 34, 18– 29. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Transformational Leadership and Digital Skills in Higher Education Institutes: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5(1), pp.1–15. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., & Beligiannis, G. N. (2021). Associations between Traditional and Digital Leadership in Academic Environment: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5(4), pp.405–428. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Halkiopoulos, C., Antonopoulou, H. (2022). Neuroleadership an Asset in Educational Settings: An Overview. Emerging Science Journal. Emerging Science Journal, 6(4), 893–904. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., Beligiannis, G. (2019). Transition from Educational Leadership to e-Leadership: A Data Analysis Report from TEI of Western Greece. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18 (9), pp.238-255. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Halkiopoulos, C., Barlou, O., Beligiannis, G. (2020). Leadership Types and Digital Leadership in Higher Education: Behavioural Data Analysis from University of Patras in Greece. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19 (4), pp.110-129. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Pallis, E. G., Bitsios, P., & Giakoumaki, S. G. (2017). Neurocognitive performance, psychopathology and social functioning in individuals at high risk for schizophrenia or psychotic bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 512–520. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Giannoulis, A., Theodorakopoulos, L., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2022). Socio-Cognitive Awareness of Inmates through an Encrypted Innovative Educational Platform. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(9), 52-75.

- Halkiopoulos, C., Antonopoulou, H., Gkintoni, E., Aroutzidis, A. (2021). Neuromarketing as an Indicator of Cognitive Consumer Behavior in Decision Making Process of Tourism Destination. In: Katsoni, V., Şerban, A.C. (eds) Transcending Borders in Tourism Through Innovation and Cultural Heritage. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H., Katsibelis, A., Halkiopoulos, C. (2021). Cognitive Parameters Detection via Gamification in Online Primary Education During Covid-19. 15th Annual International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED2021), 8-10 March, Valencia, Spain. INTED2021 Proceedings, pp. 9625-9632. [CrossRef]

- An, Y. (2020). Designing Effective Gamified Learning Experiences. International Journal of Technology in Education, 3(2), 62. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Kakoleres, G., Telonis, G., Halkiopoulos, C., & Boutsinas, B. (2023). A Conceptual Framework for Applying Social Signal Processing to Neuro-Tourism. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, 323–335. [CrossRef]

- Carson, S. (2013). Creativity and Psychopathology: Shared Neurocognitive Vulnerabilities. Neuroscience of Creativity, 175–204. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H., Kim, K. K., & Hahm, J. (2016). Neuro-Scientific Studies of Creativity. Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders, 15(4), 110. [CrossRef]

- Stamatiou, Y. C., Halkiopoulos, C., Giannoulis, A., & Antonopoulou, H. (2022). Utilizing a Restricted Access e-Learning Platform for Reform, Equity, and Self-development in Correctional Facilities. Emerging Science Journal, 6, 241–252. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, T. S. (2006). The Psychology of Novelty-Seeking, Creativity and Innovation: Neurocognitive Aspects Within a Work-Psychological Perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management, 15(2), 164–172. [CrossRef]

- Leder, H., & Belke, B. (2019). Art and Cognition: Cognitive Processes in Art Appreciation. Evolutionary and Neurocognitive Approaches to Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 149–163. [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E., Boutsinas, B., Kourkoutas, E. (2022). Developmental Trauma and Neurocognition in Young Adults. 14th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, 4 th – 6 th July, Mallorca, Spain. [CrossRef]

- Bayley, S.H. (2022). Learning for adaptation and 21st-century skills: Evidence of pupils’ flexibility in Rwandan primary schools. International Journal of Educational Development, 93. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, R. L. M., Alves, R. J. R., Azoni, C. A. S. (2022). Creativity and its relationship with intelligence and reading skills in children: an exploratory study. Psicologia: Reflexao e Critica, 35(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Mourgues, C., Tan, M., Hein, S., Elliott, J. G., Grigorenko, E. L. (2016). Using creativity to predict future academic performance: An application of Aurora's five subtests for creativity. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 378-386. [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L. D., Thomas, J., Finch, W. H., Ridgley, L. M. (2022). Exploring creativity's complex relationship with learning in early elementary students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 44. [CrossRef]

- Sur, E., Ateş, M. (2022). Examination of the Relationship Between Creative Thinking Skills and Comprehension Skills of Middle School Students. Participatory Educational Research, 9(2), 313-324. [CrossRef]

- Toivainen, T., Madrid-Valero, J. J., Chapman, R., McMillan, A., Oliver, B. R., Kovas, Y. (2021). Creative expressiveness in childhood writing predicts educational achievement beyond motivation and intelligence: A longitudinal, genetically informed study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(4), 1395-1413. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Ren, P., Deng, L. (2020). Gender Differences in the Creativity–Academic Achievement Relationship: A Study from China. Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(3), 725-732. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).