Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

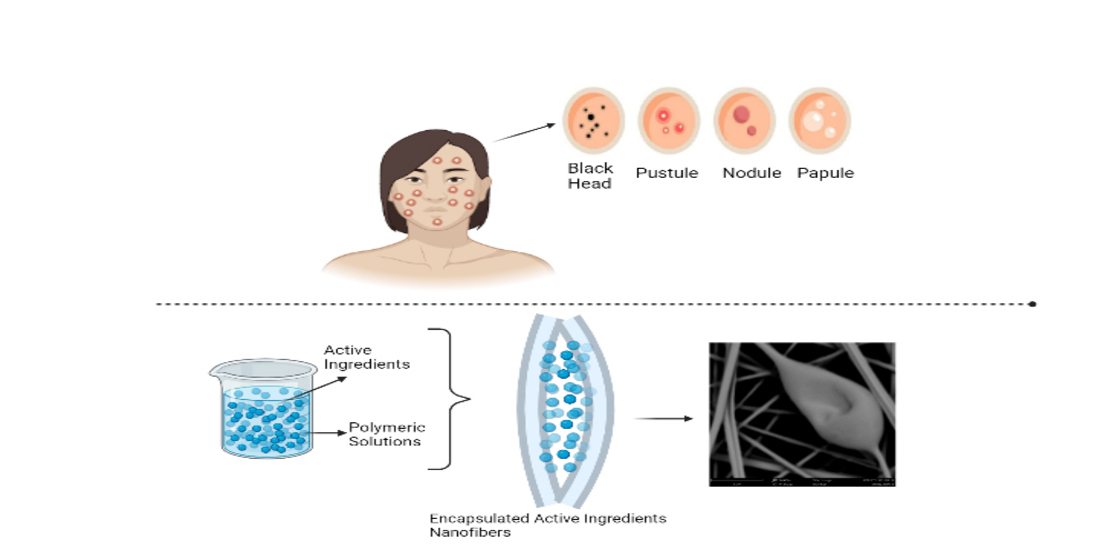

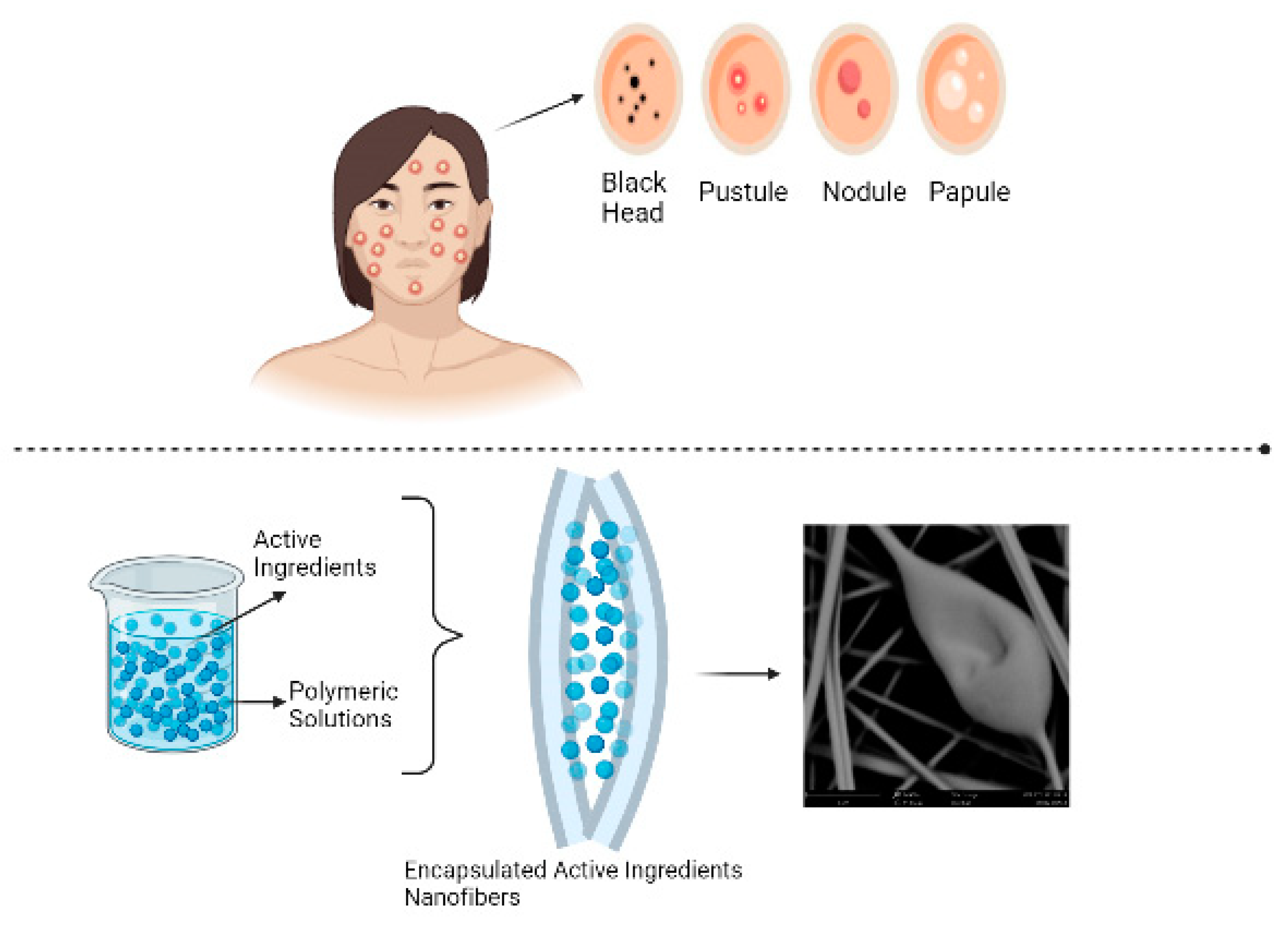

1. Introduction

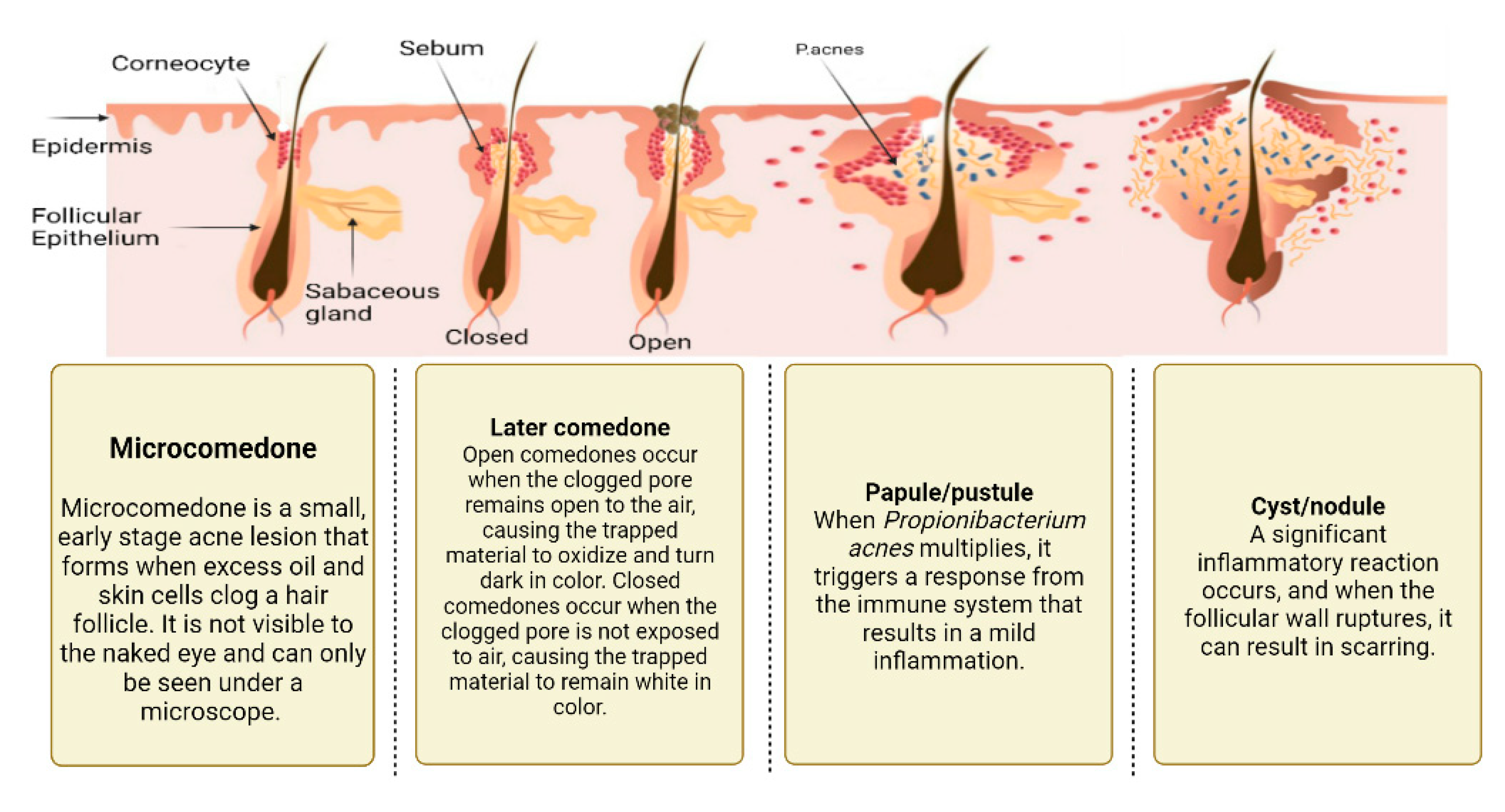

2. Pathogenesis of Acne

2.1. Excess sebum production

2.2. Epidermal hyper-proliferation and formation of comedones

2.3. Propionibacterium Acnes Infiltration

2.4. Inflammation Process

3. Treatment of Acne

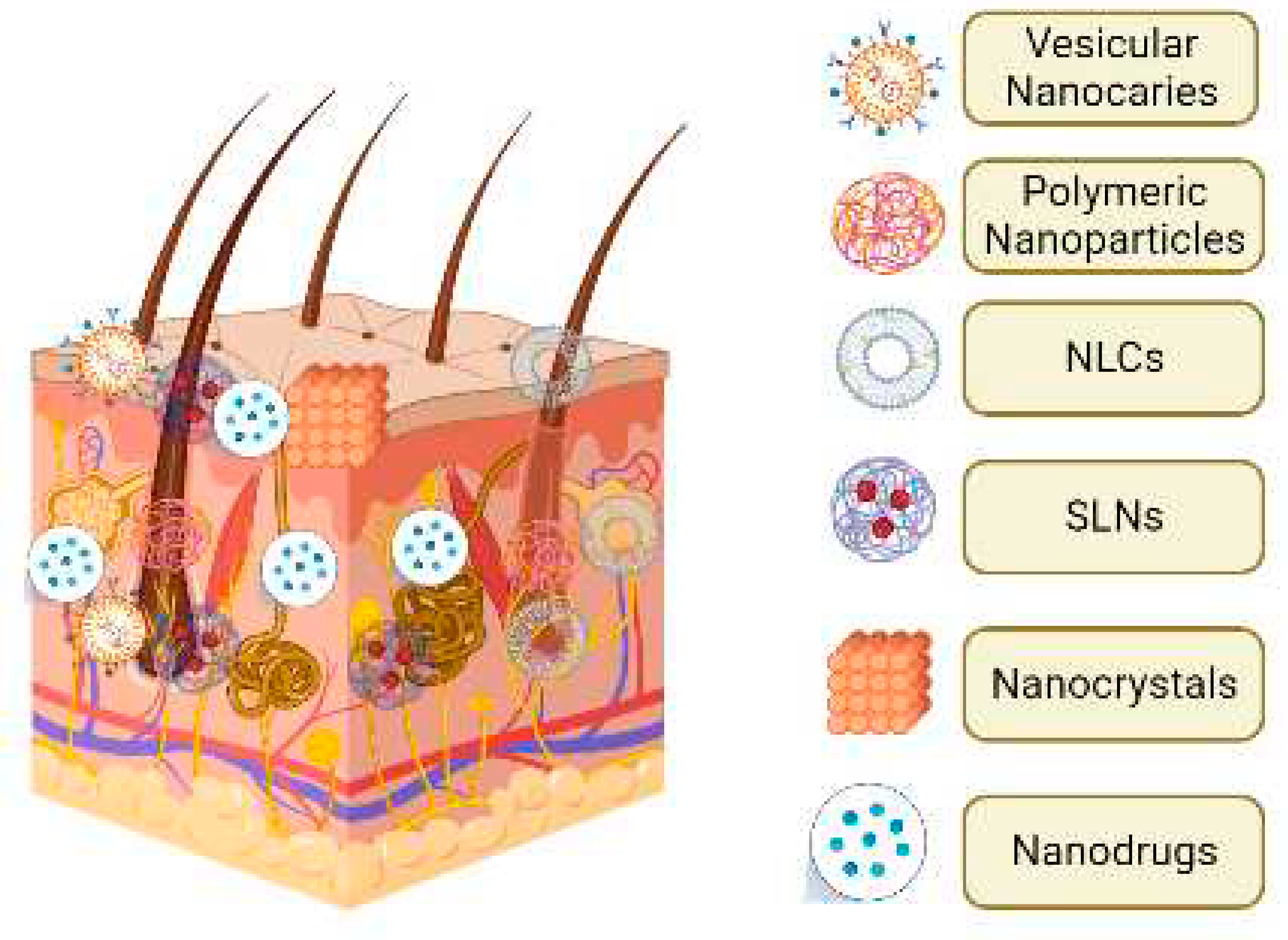

4. Nanotechnology & acne treatment

5.1. Lipid nanoparticles (LNs)

5.1.1. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs)

5.1.2. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs)

5.1.3. Nano emulsions

5.2. Vesicular nanocarriers

5.2.1. Liposome

5.2.2. Niosome

5.2.3. Polymeric nanoparticles

5.3. Encapsulated Electrospun nanofibers

6. Conclusions, Challenges, and Future Perspectives

Abbreviations

References

- Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Coimbra, S.C.; Pawar, K.D.; Peixoto, D.; Chá-Chá, R.; Araujo, A.R.; Cabral, C.; Pinto, S.; Veiga, F. Nanotechnology-based formulations toward the improved topical delivery of anti-acne active ingredients. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 1435–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, G.A.; Oliveira, C.A.; Mahecha, G.A.B.; Ferreira, L.A.M. Comedolytic effect and reduced skin irritation of a new formulation of all-trans retinoic acid-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for topical treatment of acne. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2011, 303, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, N.; Narayanan, V.; Gautam, H.K. Nano-Therapeutics to Treat Acne Vulgaris. Indian J. Microbiol. 2022, 62, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, D.D.; Umari, T.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Dunnick, C. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc. Heal. Med. Ther. 2016, ume 7, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanli, T.; Michniak-Kohn, B.B. Development and Characterization of a Topical Gel Formulation of Adapalene-TyroSpheres and Assessment of Its Clinical Efficacy. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsambas, A.D.; Dessinioti, C. Hormonal therapy for acne: why not as first line therapy? facts and controversies. Clin. Dermatol. 2010, 28, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.A.; Bagatin, E. Skin barrier and microbiome in acne. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2017, 310, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, G.; Azarpira, N.; Alizadeh, A.; Goshtasbi, S.; Tayebi, L. Shedding light on the role of keratinocyte-derived extracellular vesicles on skin-homing cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.U. In Vitro Models Mimicking Immune Response in the Skin. Yonsei Med J. 2021, 62, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, M.I.; Roop, D.R. Mechanisms Regulating Epithelial Stratification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Navarini, A.; Vavricka, S.R. Skin Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 53, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luger, T.; Amagai, M.; Dreno, B.; Dagnelie, M.-A.; Liao, W.; Kabashima, K.; Schikowski, T.; Proksch, E.; Elias, P.M.; Simon, M.; et al. Atopic dermatitis: Role of the skin barrier, environment, microbiome, and therapeutic agents. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2021, 102, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre Rocha, M.; Sousa Costa, C.; Bagatin, E. Acne Vulgaris: an Inflammatory Disease Even Before the Onset of Clinical Lesions. Inflammation & Allergy - Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets - Inflammation & Allergy) 2014, 13, 162–7. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, K.; Singh, B.; Singla, S.; Wadhwa, S.; Garg, B.; Chhibber, S.; Katare, O.P. Nanocolloidal Carriers of Isotretinoin: Antimicrobial Activity against Propionibacterium acnes and Dermatokinetic Modeling. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 1958–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlapudi, A.P.; Kodali, V.P.; Kota, K.P.; Shaik, S.S.; Kumar, N.S.S.; Dirisala, V.R. Deciphering the effect of novel bacterial exopolysaccharide-based nanoparticle cream against Propionibacterium acnes. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casetti, F.; Wölfle, U.; Gehring, W.; Schempp, C. Dermocosmetics for Dry Skin: A New Role for Botanical Extracts. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 24, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.M.; Khan, S.; Rawnsley, J. Hair Biology. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2018, 26, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mondragón, E.A.; Ganoza-Granados, L.d.C.; Toledo-Bahena, M.E.; Valencia-Herrera, A.M.; Duarte-Abdala, M.R.; Camargo-Sánchez, K.A.; Mena-Cedillos, C.A. Acne and diet: a review of pathogenic mechanisms. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex 2022, 79, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farci, F.; Mahabal, G.D. Hyperkeratosis. StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A.; Schlosser, B.; Paller, A. A review of diagnosis and treatment of acne in adult female patients. Int. J. Women's Dermatol. 2017, 4, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, B.-J.; Kwon, A.-R. The grease trap: uncovering the mechanism of the hydrophobic lid in Cutibacterium acnes lipase. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Jain, A.; Garg, N.K.; Agarwal, A.; Jain, A.; Jain, S.A.; Tyagi, R.K.; Jain, R.K.; Agrawal, H.; Agrawal, G.P. Adapalene loaded solid lipid nanoparticles gel: An effective approach for acne treatment. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2014, 121, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, E.; Güngör, S.; Özsoy, Y. Potential enhancement and targeting strategies of polymeric and lipid-based nanocarriers in dermal drug delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2017, 8, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Li, H. Acne, the Skin Microbiome, and Antibiotic Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilicka, K.; Dzieńdziora-Urbińska, I.; Szyguła, R.; Asanova, B.; Nowicka, D. Microbiome and Probiotics in Acne Vulgaris—A Narrative Review. Life 2022, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.P.; A Smith, C.; Luo, H.; Liu, Y. Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2016, CD009436–CD009436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabouri, M.; Samadi, A.; Nasrollahi, S.A.; Farboud, E.S.; Mirrahimi, B.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Kashani, M.N.; Dinarvand, R.; Firooz, A. Tretinoin Loaded Nanoemulsion for Acne Vulgaris: Fabrication, Physicochemical and Clinical Efficacy Assessments. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilicka, K.; Rusztowicz, M.; Szyguła, R.; Nowicka, D. Methods for the Improvement of Acne Scars Used in Dermatology and Cosmetology: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.R. Sorafenib-Associated Facial Acneiform Eruption. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 5, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Eady, A.; Philpott, M.; Goldsmith, L.A.; Orfanos, C.; Cunliffe, W.C.; Rosenfield, R. What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp. Dermatol. 2005, 14, 143–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.K.; Horrow, M.M.; Smith, R.J.; Springer, J. Adenomyosis: A Sonographic Diagnosis. RadioGraphics 2018, 38, 1576–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagatin, E.; da Rocha, M.A.D.; Freitas, T.H.P.; Costa, C.S. Treatment challenges in adult female acne and future directions. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.L.; Carneiro, G.; de Araújo, L.A.; de Jesus, M.; Trindade, V.; Yoshida, M.I.; Oréfice, R.L.; Farias, L.d.M.; de Carvalho, M.A.R.; Dos Santos, S.G.; et al. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with Retinoic Acid and Lauric Acid as an Alternative for Topical Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olutunmbi, Y.; Paley, K.; English, J.C. Adolescent Female Acne: Etiology and Management. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2008, 21, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, L.; Csongradi, C.; Aucamp, M.; du Plessis, J.; Gerber, M. Treatment Modalities for Acne. Molecules 2016, 21, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Piquero-Martin, J. Update and Future of Systemic Acne Treatment. Dermatology 2003, 206, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, H.; Cunliffe, W.; Berson, D.; Dreno, B.; Finlay, A.; Leyden, J.J.; Shalita, A.R.; Thiboutot, D. Management of acne: a report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, S1–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, E.M.; Graber, E.M. Clinical pearl: comedone extraction for persistent macrocomedones while on isotretinoin therapy. J. Clin. aesthetic Dermatol. 2011, 4, 20–1. [Google Scholar]

- Thiboutot, D.; Gollnick, H.; Bettoli, V.; Dréno, B.; Kang, S.; Leyden, J.J.; Shalita, A.R.; Lozada, V.T.; Berson, D.; Finlay, A.; et al. New insights into the management of acne: An update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Group. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 60, S1–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne, an overview. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serarslan, G.; Kaya. M.; Dirican, E. Scale and Pustule on Dermoscopy of Rosacea: A Diagnostic Clue for Demodex Species. Dermatol. Pr. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021139–e2021139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.C.C.D.; Gama, A.C.C.; Genilhú, P.d.F.L.; Santos, M.A.R. High speed digital videolaringoscopy: evaluation of vocal nodules and cysts in women. CoDAS 2021, 33, e20200095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollnick, H. Current Concepts of the Pathogenesis of Acne: implications for drug treatment. Drugs 2003, 63, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piipponen, M.; Li, D.; Landén, N.X. The Immune Functions of Keratinocytes in Skin Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M.; Schmuth, M. Abnormal skin barrier in the etiopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 9, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, A.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, T. Staphylococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2007, 29, S23–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonkosky, D.M.; Pochi, P.E. Acne vulgaris in childhood. Pathogenesis and management. Dermatol Clin 1986, 4, 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnec, V.; Eilers, H.; Jahns, A.C.; Omer, H.; Alexeyev, O.A. Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) granulosum Extracellular DNase BmdE Targeting Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) acnes Biofilm Matrix, a Novel Inter-Species Competition Mechanism. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 809792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, C.N.; Lehmann, P.F. Acne: a review of immunologic and microbiologic factors. Hear. 1999, 75, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, A.; Mozafarpoor, S.; Bodaghabadi, M.; Mohamadi, M. The potential of probiotics for treating acne vulgaris: A review of literature on acne and microbiota. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.H.; Suh, D.H. Recent progress in the research aboutPropionibacterium acnesstrain diversity and acne: pathogen or bystander? Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platsidaki, E.; Dessinioti, C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, J.; Bond, R. Malassezia Yeasts in Veterinary Dermatology: An Updated Overview. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Pécastaings, S.; Corvec, S.; Veraldi, S.; Khammari, A.; Roques, C. Cutibacterium acnes (Propionibacterium acnes) and acne vulgaris: a brief look at the latest updates. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32 (Suppl. S2), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, T.-X.; Hao, D.; Wen, X.; Li, X.-H.; He, G.; Jiang, X. From pathogenesis of acne vulgaris to anti-acne agents. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, I.L.; Haider, T.; Kumari, A.; Dubey, S.; Jain, P.; Soni, V. Models for acne: A comprehensive study. Drug Discov. Ther. 2018, 12, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akamatsu, H.; Horio, T.; Hattori, K. Increased hydrogen peroxide generation by neutrophils from patients with acne inflammation. Int. J. Dermatol. 2003, 42, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenfield, D.Z.; Sprague, J.; Eichenfield, L.F. Management of Acne Vulgaris. JAMA 2021, 326, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, F.; Shumaker, P.R.; Goodman, G.J.; Spring, L.K.; Seago, M.; Alam, M.; Al-Niaimi, F.; Cassuto, D.; Chan, H.H.; Dierickx, C.; et al. Energy-based devices for the treatment of Acne Scars: 2022 International consensus recommendations. Lasers Surg. Med. 2021, 54, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Uk), N.G.A. Management options for moderate to severe acne – pairwise comparisons: Acne vulgaris: management: Evidence review F2. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2021.

- Tan, J.; Bhate, K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Deng, Y. Ablative Fractional CO2 Laser for Facial Atrophic Acne Scars. Facial Plast. Surg. 2018, 34, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Q.; Tao, T.; Hu, T.; Karadağ, A.S.; Al-Khuzaei, S.; Chen, W. Sex hormones and acne. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 35, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A.K.; Saric, S.; Sivamani, R.K. Acne Scars: How Do We Grade Them? Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 19, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, G.J.; Baron, J.A. Postacne scarring - a quantitative global scarring grading system. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2006, 5, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Beissert, S.; Cook-Bolden, F.; Chavda, R.; Harper, J.; Hebert, A.; Lain, E.; Layton, A.; Rocha, M.; Weiss, J.; et al. Impact of Facial Atrophic Acne Scars on Quality of Life: A Multi-country Population-Based Survey. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 23, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Chuang, Y.; Chen, P.; Chen, C. Efficacy and Safety of Ablative Resurfacing With A High-Energy 1,064 Nd-YAG Picosecond-domain Laser for the Treatment of Facial Acne Scars in Asians. Lasers Surg. Med. 2019, 52, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.; Park, H.; Choi, S.; Bae, Y.; Kang, C.; Jung, J.; Park, G. Combined Fractional Treatment of Acne Scars Involving Non-ablative 1,550-nm Erbium-glass Laser and Micro-needling Radiofrequency: A 16-week Prospective, Randomized Split-face Study. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2017, 97, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.K.; Tang, J.; Fung, K.; Gupta, A.K.; Thomas, D.R.; Sapra, S.; Lynde, C.; Poulin, Y.; Gulliver, W.; Sebaldt, R.J. Development and Validation of a Scale for Acne Scar Severity (SCAR-S) of the Face and Trunk. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2010, 14, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhang, X.; Jones, E.; Bulger, L. Correlation of photographic images from the Leeds revised acne grading system with a six-category global acne severity scale. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 27, e414–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.-M.; Min, H.-G.; Kim, H.-J.; Shin, J.-H.; Nam, S.-H.; Han, K.-S.; Ryu, J.-H.; Oh, J.-J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, K.-J.; et al. Effects of repetitive photodynamic therapy using indocyanine green for acne vulgaris. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Gloor, M.; Merkel, W.; Warnecke, J.; Höffler, U.; Lehmacher, W.; Glutsch, J. Antibacterial and sebosuppressive efficacy of a combination of chloramphenicol and pale sulfonated shale oil. Multicentre, randomized, vehicle-controlled, double-blind study on 91 acne patients with acne papulopustulosa (Plewig and Kligman's grade II-III). Arzneimittelforschung 1998, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Xia, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, G.J.; Sang, H.; Peinemann, F. Topical azelaic acid, salicylic acid, nicotinamide, sulphur, zinc and fruit acid (alpha-hydroxy acid) for acne. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD011368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, G.T.; Mac Donald, C.L.; Markowitz, A.J.; Stephenson, D.; Robbins, A.; Gardner, R.C.; Winkler, E.; Bodien, Y.G.; Taylor, S.R.; Yue, J.K.; et al. The Traumatic Brain Injury Endpoints Development (TED) Initiative: Progress on a Public-Private Regulatory Collaboration To Accelerate Diagnosis and Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 2721–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S.; Noorizadeh, K.; Zadmehr, O.; Rasekh, S.; Mohammadi-Samani, S.; Dehghan, D. Novel topical drug delivery systems in acne management: Molecular mechanisms and role of targeted delivery systems for better therapeutic outcomes. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, S.; Kaur, R.; Sahu, P.M. Efficacy of Microneedling With 35% Glycolic Acid Peels Versus Microneedling With 15% Trichloroacetic Acid Peels in Treatment of Atrophic Acne Scars: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2022, 48, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langley, R.G.B.; Feldman, S.R.; Nyirady, J.; van de Kerkhof, P.; Papavassilis, C. The 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) Scale: A modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2013, 26, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; ElMahdy, N.; Elfar, N.N. Microneedling (Dermapen) and Jessner's solution peeling in treatment of atrophic acne scars: a comparative randomized clinical study. J. Cosmet. Laser Ther. 2019, 21, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, G.J.; Baron, J.A. Postacne Scarring: A Qualitative Global Scarring Grading System. Dermatol. Surg. 2006, 32, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréno, B.; Poli, F.; Pawin, H.; Beylot, C.; Faure, M.; Chivot, M.; Auffret, N.; Moyse, D.; Ballanger, F.; Revuz, J. Development and evaluation of a Global Acne Severity Scale (GEA Scale) suitable for France and Europe. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 25, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, S.; Kotla, N.G.; Webster, T.J. Formulation and evaluation of a topical niosomal gel containing a combination of benzoyl peroxide and tretinoin for antiacne activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Cong, T.; Wen, X.; Li, X.; Du, D.; He, G.; Jiang, X. Salicylic acid treats acne vulgaris by suppressing AMPK / SREBP 1 pathway in sebocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, M.; Chehade, A.; Sanghera, R.; Grewal, P. A Clinician’s Guide to Topical Retinoids. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2021, 26, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreno, B.; Bagatin, E.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Rocha, M.; Gollnick, H. Female type of adult acne: Physiological and psychological considerations and management. JDDG: J. der Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2018, 16, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alliance (UK), NG. Management options for moderate to severe acne – pairwise comparisons; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.; Redhu, R.; Verma, R.; Mittal, V.; Kaushik, D. Anti-acne Treatment using Nanotechnology based on Novel Drug Delivery System and Patents on Acne Formulations: A Review. Recent Patents Nanotechnol. 2021, 15, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Fernandez, B.; Castaño, O.; Mateos-Timoneda, M. .; Engel, E.; Pérez-Amodio, S. Nanotechnology Approaches in Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2021, 10, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Silva, A.L.; Guerra, C.; Peixoto, D.; Pereira-Silva, M.; Zeinali, M.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Castro, R.; Veiga, F. Ethosomes as Nanocarriers for the Development of Skin Delivery Formulations. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 947–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolli, S.S.; Pecone, D.; Pona, A.; Cline, A.; Feldman, S.R. Topical Retinoids in Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chatim, A.; Kankaria, A.; Feldman, S. Review of Tretinoin-Benzoyl Peroxide in The Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliervoet, L.A.; Mastrobattista, E. Drug delivery with living cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Lv, W.; Peng, R. Recent Advances in Nano-Formulations for Skin Wound Repair Applications. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, ume 16, 2707–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, L.; Morelli, L.; Ochoa, E.; Labra, M.; Fiandra, L.; Palugan, L.; Prosperi, D.; Colombo, M. The emerging role of nanotechnology in skincare. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 293, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht, S.; Asghari-Sana, F.; Fathi-Azarbayjani, A.; Sharifi, Y. Fabrication and characterization of tretinoin-loaded nanofiber for topical skin delivery. Biomater. Res. 2020, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlířová, R.; Langová, D.; Bendová, A.; Gross, M.; Skoumalová, P.; Márová, I. Antimicrobial Activity of Gelatin Nanofibers Enriched by Essential Oils against Cutibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnama, S.; Movaffagh, J.; Shahroodi, A.; Jirofti, N.; Bazzaz, B.S.F.; Beyraghdari, M.; Hashemi, M.; Kalalinia, F. Development and characterization of the electrospun melittin-loaded chitosan nanofibers for treatment of acne vulgaris in animal model. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Rayner, S.; Chung, R.; Shi, B.; Liang, X.-J. Advances in nanotechnology-based strategies for the treatments of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mater. Today Bio 2020, 6, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Utreja, P.; Kumar, L. Nanotechnological Carriers for Treatment of Acne. Recent Patents Anti-Infective Drug Discov. 2018, 13, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hajleh, M.N.; Abu-Huwaij, R.; Al-Samydai, A.; Al-Halaseh, L.K.; Al-Dujaili, E.A. The revolution of cosmeceuticals delivery by using nanotechnology: A narrative review of advantages and side effects. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 20, 3818–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.S.; Nasr, M.; Mamdouh, W.; Sammour, O. Insights on the Use of Nanocarriers for Acne Alleviation. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2018, 16, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrapovic, N.; Richard, T.; Messaraa, C.; Li, X.; Abbaspour, A.; Fabre, S.; Mavon, A.; Andersson, B.; Khmaladze, I. Clinical and metagenomic profiling of hormonal acne-prone skin in different populations. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6233–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Wiraja, C.; Chew, S.W.T.; Xu, C. Nanodelivery Systems for Topical Management of Skin Disorders. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 18, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baveloni, F.G.; Riccio, B.V.F.; Di Filippo, L.D.; Fernandes, M.A.; Meneguin, A.B.; Chorilli, M. Nanotechnology-based Drug Delivery Systems as Potential for Skin Application: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 3216–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contri, R.V.; Frank, L.A.; Kaiser, M.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Guterres, S.S. The use of nanoencapsulation to decrease human skin irritation caused by capsaicinoids. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-H.; Hung, C.-F.; Sung, H.-C.; Yang, S.-C.; Yu, H.-P.; Fang, J.-Y. The Bioactivities of Resveratrol and Its Naturally Occurring Derivatives on Skin. J. Food Drug Anal. 2021, 29, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boskabadi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Akbari, J.; Morteza-Semnani, K.; Hashemi, S.M.H.; Babaei, A. Topical Gel of Vitamin A Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: A Hopeful Promise as a Dermal Delivery System. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 11, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.; Coelho, C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Botelho, C.M. Nanocarriers as Active Ingredients Enhancers in the Cosmetic Industry—The European and North America Regulation Challenges. Molecules 2022, 27, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, T.S.; Gujarathi, N.A.; Aher, A.A.; Pachpande, H.E.; Sharma, C.; Ojha, S.; Goyal, S.N.; Agrawal, Y.O. Recent Advancements in Topical Anti-Psoriatic Nanostructured Lipid Carrier-Based Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A.; Cristiano, M.C.; Fresta, M.; Paolino, D. The Challenge of Nanovesicles for Selective Topical Delivery for Acne Treatment: Enhancing Absorption Whilst Avoiding Toxicity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, ume 15, 9197–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.S.; Ellis, C.N.; Headington, J.T.; Voorhees, J.J. Topical tretinoin in the treatment of aging skin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1988, 19, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschoff, R.; Möller, S.; Haase, R.; Kuske, M. Tolerability and Efficacy of Clindamycin/Tretinoin versus Adapalene/Benzoyl Peroxide in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. 2021, 20, 295–301. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, A.; Sonker, A.K.; Gidwani, B. Carrier-Based Drug Delivery System for Treatment of Acne. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghule, T.; Rapalli, V.K.; Gorantla, S.; Saha, R.N.; Dubey, S.K.; Puri, A.; Singhvi, G. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers as Potential Drug Delivery Systems for Skin Disorders. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4569–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroğlu. ; Aslan, M.; Yaman,.; Gultekinoglu, M.; Çalamak, S.; Kart, D.; Ulubayram, K. Liposome-based combination therapy for acne treatment. J. Liposome Res. 2019, 30, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škalko, N.; Čajkovac, M.; Jalšenjak, I. Liposomes with clindamycin hydrochloride in the therapy of acne vulgaris. Int. J. Pharm. 1992, 85, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, K.M.; Mandal, A.S.; Biswas, N.; Guha, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Behera, M.; Kuotsu, K. Niosome: A future of targeted drug delivery systems. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2010, 1, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asthana, G.S.; Sharma, P.K.; Asthana, A. In VitroandIn VivoEvaluation of Niosomal Formulation for Controlled Delivery of Clarithromycin. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chutoprapat, R.; Kopongpanich, P.; Chan, L.W. A Mini-Review on Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Topical Delivery of Phytochemicals for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris. Molecules 2022, 27, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers as novel drug delivery systems: Applications, advantages and disadvantages. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 13, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, M.K.; Yen, T.-L.; Jan, J.-S.; Tang, R.-D.; Wang, J.-Y.; Taliyan, R.; Yang, C.-H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs): An Advanced Drug Delivery System Targeting Brain through BBB. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraban, N.; Musich, P.R.; Freeman, H.S. Synthesis and Encapsulation of a New Zinc Phthalocyanine Photosensitizer into Polymeric Nanoparticles to Enhance Cell Uptake and Phototoxicity. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmowafy, M.; Al-Sanea, M.M. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) as drug delivery platform: Advances in formulation and delivery strategies. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani-Asadi-Jafari, F.; Hadjizadeh, A. Niosome-encapsulated Doxycycline hyclate for Potentiation of Acne Therapy: Formulation and Characterization. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Spray-drying of oil-in-water emulsions for encapsulation of retinoic acid: Polysaccharide- and protein-based microparticles characterization and controlled release studies. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 124, 107193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korting, H.C.; Schäfer-Korting, M. Carriers in the Topical Treatment of Skin Disease. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2009, 197, 435–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Veiga, F.; Figueiras, A. Dendrimers as Pharmaceutical Excipients: Synthesis, Properties, Toxicity and Biomedical Applications. Materials 2019, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, S.; Shakeel, F.; Talegaonkar, S.; Ahmad, F.J.; Khar, R.K.; Ali, M. Development and bioavailability assessment of ramipril nanoemulsion formulation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 66, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Jung, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, S.; Youn, H.; Im, H.-J. Lipid nanoparticles for delivery of RNA therapeutics: Current status and the role of in vivo imaging. Theranostics 2022, 12, 7509–7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, D.; Kiselev, M.A. Methods of Liposomes Preparation: Formation and Control Factors of Versatile Nanocarriers for Biomedical and Nanomedicine Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assali, M.; Zaid, A.-N. Features, applications, and sustainability of lipid nanoparticles in cosmeceuticals. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Loomis, K.; Smith, B.; Lee, J.-H.; Yavlovich, A.; Heldman, E.; Blumenthal, R. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles as Pharmaceutical Drug Carriers: From Concepts to Clinic. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2009, 26, 523–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Wu, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z. Cell or Cell Membrane-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Theranostics 2015, 5, 863–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosa, A.; Reddi, S.; Saha, R.N. Nanostructured lipid carriers for site-specific drug delivery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, R.; Dawre, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles dispersed topical hydrogel for Co-delivery of adapalene and minocycline for acne treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matussek, F.; Pavinatto, A.; Knospe, P.; Beuermann, S.; Sanfelice, R.C. Controlled Release of Tea Tree Oil from a Chitosan Matrix Containing Gold Nanoparticles. Polymers 2022, 14, 3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharkar, V.B.; Mendiratta, C.; Kyadarkunte, A.Y.; Bhosale, S.H.; A Barhate, G. Skin delivery aspects of benzoyl peroxide-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for acne treatment. Ther. Deliv. 2014, 5, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, V.; Bansal, K.K.; Verma, A.; Yadav, N.; Thakur, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Rosenholm, J.M. Solid lipid nanoparticles: Emerging colloidal nano drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, W.; Mäder, K. Solid lipid nanoparticles Production, characterization and applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 47, 165–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemiyeh, P.; Mohammadi-Samani, S. Potential of Nanoparticles as Permeation Enhancers and Targeted Delivery Options for Skin: Advantages and Disadvantages. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, ume 14, 3271–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, R.; Zhan, Y.; Wei, S.; Xu, S.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J. Tea tree oil nanoliposomes: optimization, characterization, and antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.P.; Varela, C.; Mendonça, L.; Cabral, C. Nanotechnology-Based Topical Delivery of Natural Products for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, T.; Gomes, D.; Simões, R.; Miguel, M.d.G. Tea Tree Oil: Properties and the Therapeutic Approach to Acne—A Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsewedy, H.S.; Shehata, T.M.; Soliman, W.E. Tea Tree Oil Nanoemulsion-Based Hydrogel Vehicle for Enhancing Topical Delivery of Neomycin. Life 2022, 12, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingchoncharoen, P.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Richardson, D.R. Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy: What Is Available and What Is Yet to Come. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 701–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, N.; Valizadeh, H.; Zakeri-Milani, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Structure, Preparation and Application. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 5, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, R.H.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery--a review of the state of the art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, K.L.; Ravasio, A.; González-Aramundiz, J.V.; Zacconi, F.C. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) Prepared by Microwave and Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis: Promising Green Strategies for the Nanoworld. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowska-Kośnik, A.; Szekalska, M.; Winnicka, K. Nanostructured lipid carriers: A potential use for skin drug delivery systems. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 71, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musielak, E.; Feliczak-Guzik, A.; Nowak, I. Optimization of the Conditions of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) Synthesis. Molecules 2022, 27, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-L.; Al-Suwayeh, S.A.; Fang, J.-Y. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) for Drug Delivery and Targeting. Recent Patents Nanotechnol. 2013, 7, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Mustapha, O.; Ali, T.; Rehman, M.; Zaidi, S.S.; Baseer, A.; Batool, S.; Mukhtiar, M.; Shafique, S.; Malik, M.; et al. Development, Characterization, and Evaluation of SLN-Loaded Thermoresponsive Hydrogel System of Topotecan as Biological Macromolecule for Colorectal Delivery. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9968602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, I.; Yasir, M.; Verma, M.; Singh, A.P. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Groundbreaking Approach for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 10, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.; Patrício, A.B.; Prata, J.M.; Nadhman, A.; Chintamaneni, P.K.; Fonte, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Comparative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, F.; Shafiq, S.; Haq, N.; Alanazi, F.K.; A Alsarra, I. Nanoemulsions as potential vehicles for transdermal and dermal delivery of hydrophobic compounds: an overview. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 9, 953–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurpret, K.; Singh, S.K. Review of Nanoemulsion Formulation and Characterization Techniques. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 80, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.F.; Masoumi, H.R.F.; Karjiban, R.A.; Stanslas, J.; Kirby, B.P.; Basri, M.; Bin Basri, H. Ultrasonic emulsification of parenteral valproic acid-loaded nanoemulsion with response surface methodology and evaluation of its stability. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2016, 29, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevc, G.; Vierl, U. Nanotechnology and the transdermal route: A state of the art review and critical appraisal. J. Control. Release 2010, 141, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosny, K.M.; Al Nahyah, K.S.; Alhakamy, N.A. Self-Nanoemulsion Loaded with a Combination of Isotretinoin, an Anti-Acne Drug, and Quercetin: Preparation, Optimization, and In Vivo Assessment. Pharmaceutics 2020, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, J.; Ciotti, S.; Baker, J.R. Methods of treating acne using nanoemulsion compositions. WO201702 3751A2, 2017.

- Ridolfi, D.M.; Marcato, P.D.; Justo, G.Z.; Cordi, L.; Machado, D.; Durán, N. Chitosan-solid lipid nanoparticles as carriers for topical delivery of tretinoin. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2012, 93, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Narasimhan, B.; Wang, Q. Biocompatible nanoparticles and vesicular systems in transdermal drug delivery for various skin diseases. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 555, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badilli, U.; Gumustas, M.; Uslu, B.; Ozkan, S.A. Lipid-based nanoparticles for dermal drug delivery. In Organic Materials as Smart Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery; Grumezescu, A.M., Ed.; William Andrew Publishing: 2018; pp. 369–413. [CrossRef]

- Vanic, Z.; Holaeter, A.-M.; Skalko-Basnet, N. (Phospho)lipid-based Nanosystems for Skin Administration. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 4174–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raminelli, A.C.P.; Romero, V.; Semreen, M.H.; Leonardi, G.R. Nanotechnological Advances for Cutaneous Release of Tretinoin: An Approach to Minimize Side Effects and Improve Therapeutic Efficacy. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 3703–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Abdelmalak, N.S.; Badawi, A.; Elbayoumy, T.; Sabry, N.; El Ramly, A. Tretinoin-loaded liposomal formulations: from lab to comparative clinical study in acne patients. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Wei, M.; He, S.; Yuan, W.-E. Advances of Non-Ionic Surfactant Vesicles (Niosomes) and Their Application in Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamishehkar, H.; Rahimpour, Y.; Kouhsoltani, M. Niosomes as a propitious carrier for topical drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012, 10, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Wei, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Zhao, L. Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6027–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Lee, R.J.; Xiang, G. Nano Encapsulated Curcumin: And Its Potential for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, ume 15, 3099–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrarya, M.; Gharehchelou, B.; Poodeh, S.H.; Jamshidifar, E.; Karimifard, S.; Far, B.F.; Akbarzadeh, I.; Seifalian, A. Niosomal formulation for antibacterial applications. J. Drug Target. 2022, 30, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkilani, A.Z.; Abu-Zour, H.; Alshishani, A.; Abu-Huwaij, R.; Basheer, H.A.; Abo-Zour, H. Formulation and Evaluation of Niosomal Alendronate Sodium Encapsulated in Polymeric Microneedles: In Vitro Studies, Stability Study and Cytotoxicity Study. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Huang, H.-Y. In Vitro Anti-Propionibacterium Activity by Curcumin Containing Vesicle System. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 61, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, G.; Garg, T.; Malik, B.; Chauhan, G.; Rath, G.; Goyal, A.K. Development and characterization of niosomal gel for topical delivery of benzoyl peroxide. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, P.; Patravale, V. The Upcoming Field of Theranostic Nanomedicine: An Overview. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2012, 8, 859–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabaa, H.; Mady, F.M.; Hussein, A.K.; Abdel-Wahab, H.M.; Ragaie, M.H. Dapsone in topical niosomes for treatment of acne vulgaris. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 12, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucho, C.I.C.; Barros, M.T. Polymeric nanoparticles: A study on the preparation variables and characterization methods. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 80, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzoni, E.; Cesaretti, A.; Polchi, A.; Di Michele, A.; Tancini, B.; Emiliani, C. Biocompatible Polymer Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Applications in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Disorder Therapies. J. Funct. Biomater. 2019, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.; Giuliano, E.; Venkateswararao, E.; Fresta, M.; Bulotta, S.; Awasthi, V.; Cosco, D. Biodegradable Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 601626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Parveen, R.; Chatterji, B.P. Toxicology of Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2021, 9, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikušová, V.; Mikuš, P. Advances in Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucho, C.I.C.; Barros, M.T. Polymeric nanoparticles: A study on the preparation variables and characterization methods. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 80, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prgomet, I.; Gonçalves, B.; Domínguez-Perles, R.; Pascual-Seva, N.; Barros, A.I.R.N.A. Valorization Challenges to Almond Residues: Phytochemical Composition and Functional Application. Molecules 2017, 22, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatpou, D.; Mehrabi, F.; Rahzani, K.; Aminiyan, A. The Effect of Aloe Vera Clinical Trials on Prevention and Healing of Skin Wound: A Systematic Review. Iran. J. Med Sci. 2019, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Saric, S.; Notay, M.; Sivamani, R.K. Green Tea and Other Tea Polyphenols: Effects on Sebum Production and Acne Vulgaris. Antioxidants 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-L.; Tang, M.; Du, Q.-Q.; Liu, C.-X.; Yan, C.; Yang, J.-L.; Li, Y. The effects and mechanisms of a biosynthetic ginsenoside 3β,12β-Di-O-Glc-PPD on non-small cell lung cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, ume 12, 7375–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisoni, E.; Imbimbo, M.; Zimmermann, S.; Valabrega, G. Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy: Turning up the Heat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzohairy, M.A. Therapeutics Role ofAzadirachta indica(Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 7382506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta; Srivastava, J. K.; Shankar, E.; Gupta, S. Chamomile: A herbal medicine of the past with a bright future (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2010, 3, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.-M.; Kawanami, H.; Kawahata, H.; Aoki, M. Wound healing potential of lavender oil by acceleration of granulation and wound contraction through induction of TGF-β in a rat model. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawid-Pać, R. Medicinal plants used in treatment of inflammatory skin diseases. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2013, 3, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puaratanaarunkon, T.; Washrawirul, C.; Chuenboonngarm, N.; Noppakun, N.; Asawanonda, P.; Kumtornrut, C. Efficacy and safety of a facial serum containing snail secretion filtrate, Calendula officinalis, and Glycyrrhiza glaba root extract in the treatment of maskne: A randomized placebo-controlled study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4470–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abduljabbar, A.; Farooq, I. Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers: Processing, Properties, and Applications. Polymers 2022, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yeo, M.; Yang, G.H.; Kim, G. Cell-Electrospinning and Its Application for Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Martinez, E.J.; Cornejo-Bravo, J.M.; Serrano-Medina, A.; Perez-González, G.L.; Gómez, L.J.V. A Summary of Electrospun Nanofibers as Drug Delivery System: Drugs Loaded and Biopolymers Used as Matrices. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2018, 15, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning of Nanofibers: Reinventing the Wheel? Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Fujihara, K.; Teo, W.-E.; Yong, T.; Ma, Z.; Ramaseshan, R. Electrospun nanofibers: solving global issues. Mater. Today 2006, 9, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, G.; Huang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Jing, X. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for drug delivery applications. J. Control. Release 2014, 185, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; McCann, J.T.; Xia, Y.; Marquez, M. Electrospinning: A Simple and Versatile Technique for Producing Ceramic Nanofibers and Nanotubes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.; Chandra, A.; G. , P.; S., S.; Roy, S.; Agatemor, C.; Thomas, S.; Provaznik, I. Electrospinning over Solvent Casting: Tuning of Mechanical Properties of Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and Electrospun Nanofibers: Methods, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy Makhlouf AS. Handbook of, Nanofibers. Handbook of Nanofibers; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, R.S.; Bachu, R.D.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Bhaduri, S. Biomedical Applications of Electrospun Nanofibers: Drug and Nanoparticle Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2018, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, R.; Abbasipour, M. Controlling nanofiber morphology by the electrospinning process. In Electrospun Nanofibers; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiffrin, R.; Razak, S.I.A.; Jamaludin, M.I.; Hamzah, A.S.A.; Mazian, M.A.; Jaya, M.A.T.; Nasrullah, M.Z.; Majrashi, M.; Theyab, A.; Aldarmahi, A.A.; et al. Electrospun Nanofiber Composites for Drug Delivery: A Review on Current Progresses. Polymers 2022, 14, 3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, F.; Okutan, N. Nanofibre Encapsulation of Active Ingredients and their Controlled Release. In: Rai V R, editor. Advances in Food Biotechnology, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2015, p. 607–16. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, B.S.; Vasile, C. Encapsulation of Natural Bioactive Compounds by Electrospinning—Applications in Food Storage and Safety. Polymers 2021, 13, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miletić, A.; Pavlić, B.; Ristić, I.; Zeković, Z.; Pilić, B. Encapsulation of Fatty Oils into Electrospun Nanofibers for Cosmetic Products with Antioxidant Activity. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acne Grading Scale | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Description | Macular | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Types of Scars | Erythematous, Hypopigmentation, Hyperpigmentation | Atrophic or Hypertrophic Rolling or Papular Scars | Moderate Atrophic or Hypertrophic Scars, Rolling Distensible Scars, Shallow Box Cars | Most Severe Atrophic or Hypertrophic Scars, Deep Boxcar, Ice Pick, Bridges and Tunnels, and Keloid |

| Visibility Distance | Not visible from a 50cm distance | May be covered by makeup and facial hair | Visible at a normal social distance | Obvious at a social distance or greater |

| Flattening by hand | Not applicable | May be flattened manually | Could be flattened manually | Not able to be flattened manually |

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Clear, no lesion. Erythema and residual pigmentation may be visible. |

| 1 | Almost clear, with a few scattered open or closed comedones and very few papules. |

| 2 | Mild, with a few open or closed comedones and a few papules and pustules. Less than 50% of the face is affected. |

| 3 | Moderate, with many papules and pustules, many open or closed comedones, and one nodule. More than 50% of the face is affected. |

| 4 | Severe, with many papules and pustules, open or closed comedones, and rare nodules. The entire face is involved. |

| 5 | Very severe, with highly inflammatory acne covering the face and the presence of nodules. |

| Treatment Type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Topical Retinoids | Vitamin A derivatives that help unclog pores and reduce inflammation. | Tretinoin, Adapalene |

| Topical Antibiotics | Kill bacteria on the skin and reduce inflammation. | Clindamycin, Erythromycin |

| Topical Benzoyl Peroxide | Kills bacteria on the skin and reduces inflammation. | Benzoyl peroxide |

| Oral Antibiotics | Kill bacteria in the body and reduce inflammation. | Tetracycline, Doxycycline |

| Hormonal Therapy | Regulate hormonal imbalances that can contribute to acne. | Oral contraceptives, Spironolactone |

| Isotretinoin | A powerful oral medication that reduces oil production, unclogs pores, and reduces inflammation. | Isotretinoin |

| Chemical Peels | A chemical solution is applied to the skin to remove the top layer of dead skin cells and unclog pores. | Salicylic acid, Glycolic acid |

| Light Therapy | Blue or red light is used to kill bacteria on the skin. | Blue light therapy, Red light therapy |

| Advantages | References | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible and biodegradable | [145] | Limited drug compatibility with the lipid matrix | [145] |

| High drug loading capacity | [146] | Difficulty achieving homogenous particle size distribution | [146] |

| Controlled drug release | [147] | Risk of lipid oxidation | [147] |

| Improved skin penetration | [146] | Potential cytotoxicity of some lipids | [146] |

| Can be used with a variety of drugs | [145] | Limited research on long-term toxicity | [145] |

| Active Herbal Ingredient | Source | Potential Benefits for Acne | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tea tree oil | Leaves of Melaleuca alternifolia | Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, reduces sebum production | [183] |

| Aloe vera | Leaves of Aloe vera plant | Anti-inflammatory, wound healing, moisturizing | [184] |

| Green tea extract | Leaves of Camellia sinensis plant | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, reduces sebum production | [185] |

| Licorice extract | Roots of Glycyrrhiza glabra plant | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial | [186] |

| Turmeric extract | Roots of Curcuma longa plant | Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant | [187] |

| Neem extract | Leaves of Azadirachta indica tree | Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, reduces sebum production | [188] |

| Chamomile extract | Flowers of Matricaria chamomilla plant | Anti-inflammatory, wound healing, antibacterial | [189] |

| Lavender oil | Flowers of Lavandula angustifolia plant | Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, wound healing | [190] |

| Willow bark extract | Bark of Salix alba tree | Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, reduces sebum production | [191] |

| Calendula extract | Flowers of Calendula officinalis plant | Anti-inflammatory, wound healing, antibacterial | [192] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).