1. Introduction

In the European Union (EU), Regulation (EU) No 305/2011 (Construction Products Regulation, or CPR) lays down harmonized rules for evaluating the requirements of items permanently installed in residential and public buildings, considering the impacts on the environment and people's health and safety. 1 According to CPR, one of the basic requirements of construction works is safety in case of fire. In this context, a harmonized classification regarding reaction to fire and additional classifications for smoke production, flaming droplets, and acidity have been adopted. 2-4 Flooring, linear insulation for pipes, panels, wall coverings, and other items commonly found in buildings do not require tests and requirements for assessing the release of acid gases in case of fire. 2 However, cables are the only building and construction products for which an additional classification for acidity is required. 3

EN 13501-6 provides the test methods and requirements for evaluating the reaction to fire classification of cables and their additional classifications. 3 EN 60754-2, originally developed to determine the corrosivity, is required for assessing the acidity according to CPR, 5 with the methodology also explained in detail in Ref. 6 and Ref. 7. The test is carried out by burning the test specimen in a tube furnace. The effluents are then collected in two bubblers with double deionized water (DDW), where pH and conductivity are measured. Weighted pH and conductivity values for the cable are calculated considering the non-metallic material per unit length of the cable, according to paragraph 8.3 of the standard. 5 Class a1 cable requires the pH to be more than 4.3 and the conductivity less than 2.5 mS/mm, class a2 requires the pH to be more than 4.3, and the conductivity less than 10 mS/mm and class a3 are those materials that are neither class a1 nor class a2. EN 60754-2 is performed under isothermal conditions between 935 °C and 965 °C. On the other hand, EN 60754-1, the technical standard performed for determining the halogen acid gas content in contexts outside CPR, 8 is carried out with a heating regime: 40 minutes from room temperature to 800 °C and 20 minutes in isothermal conditions at 800 °C. In EN 60754-1, temperature increases at about 20 °C/min, covering the typical temperatures of ignition and the developing stage of the fire, and after they exceed the typical flashover temperatures (600 °C – 650 °C), 9 reaching 800 °C.

Flame retardants and smoke suppressants are crucial in designing items capable of delaying flashover, and decreasing smoke production, to meet the main goals of fire safety strategy, i.e., the reduction of fatalities and injuries, conservation of property, protection of environment, preservation of heritage, and continuity of business operations in case of fire. For evaluating the performance of flame retardants and smoke suppressants, different heat fluxes can be chosen in bench-, intermediate- or full-scale fire tests, 9, 10 to evaluate how to reduce the fire hazard, strictly linked to parameters like ignitability, flammability, heat release (amount and rate), flame spread, smoke production, and its toxicity.11, 12 Heat release rate is considered "the single most important variable" in fire hazard, 13 and several bench-scale fire tests, such as cone calorimetry, can evaluate it. In cone calorimetry, flame retardants, and smoke suppressants are usually tested in heat fluxes typical of pre-flashover fire,9, 10, 11 to understand if their use in the items can reduce the fire risk. When a PVC cable burns, hydrogen chloride (HCl) is released from the polymer's thermal decomposition; therefore, it can be one of the effluents in case of fire. However, in a real fire scenario, its concentration in the gas phase decays, absorbed by common materials found in buildings. 14 This behavior has two consequences: the HCl concentration in the gas phase is less than expected, and HCl does not travel far from where the fire originates.

Obviously, EN 60754-2 is a bench-scale test. It does not consider all variables of a real fire scenario that could affect the concentration of HCl in the gas phase; therefore, current PVC cables in the market can only meet class a3. Thus, the research in new low-smoke acidity compounds is paramount for creating PVC cables working in specific locations where the best additional classifications for acidity are needed.6, 15 Recently, a new generation of low-smoke acidity PVC compounds has been developed to manufacture cables that meet the additional classification a1 or a2. 16-18 These compounds contain acid scavengers that act at high temperatures in the condensed phase, efficiently trapping HCl in the char and reducing its evolution in the gas phase. Their performance in dropping down the smoke acidity is strictly linked to the efficiency of the acid scavengers, and the efficiency depends on the kinetics of scavenging and whether acid scavengers or their reaction products are stable in the range of temperatures where we need them to work. Therefore, as described in Ref. 6, not only temperatures, heating regimes, and the chemical nature of the acid scavengers play a crucial role in their efficiency but also their particle size and the dispersion level they can reach in the matrix, getting as much as possible an intimate contact with PVC chains. Hence, the research in novel low-smoke acidity compounds at the laboratory level will be decisive, but the right choice of production systems able to reach a high dispersion level for acid scavengers will also be crucial. Cable manufacturers willing to produce cables in class a1 or a2 must consider all these aspects.

In this article, the acidity of several PVC compounds for cables has been tested by comparing the following test methods:

1) EN 60754-2 has been carried out at 950 °C, and EN 60754-2 with the heating regime of EN 60754-1 (internal method 3).

2) EN 60754-2 has been conducted at 950 °C, and EN 60754-2 at 500 °C (internal method 2).

The hypothesis has been to verify if different heating regimes could affect the concentration of HCl in the gas phase and to explore the role of the acid scavengers in this context. In particular, it has been evaluated whether the acidity is reduced when the heating regime of EN 60754-1 is run and a pre-flashover temperature of 500 °C is chosen. In this paper, "acidity" and "smoke acidity" are considered interchangeable terms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The tested formulations have been divided into four series to verify if the internal methods 2 and 3 give different results from EN 60754-2.

Table 1 displays the first series and intends to show the impact of different acid scavengers at high temperatures on acidity, performing EN 60754-2, internal methods 2 and 3. FR50.0 is a typical PVC compound for non-flame retarded jackets, with a coated ground calcium carbonate (GCC) like Riochim.

19 FR50.1 contains a synthetic Al(OH)

3 (ATH, from Nabaltec), an inert acid scavenger, which does not reduce the smoke acidity. FR50.2 has Mg(OH)

2 (MDH, from Europiren) as uncoated brucite, an ineffective acid scavenger fixing HCl as MgCl

2 but then rereleasing it due to its decomposition.

6, 7, 20, 21 FR50.3 includes coated ultrafine precipitated calcium carbonate (UPCC), Winnofil S from Imerys

22, a potent acid scavenger which efficiently captures HCl as CaCl

2 in a single-step reaction, currently used for reducing the acidity of the PVC compounds' effluents in case of fire.

6, 7 FR50.4 and FR50.5 show the action of two potent acid scavengers from Reagens, AS-1B and AS-6B. They are the new generation of acid scavengers at high temperatures, acting in the condensed phase.

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 show typical formulations with low values of acidity, where acid scavengers work in multiple-step reactions in fixing HCl in the condensed phase. These kinds of reactions are explained in Refs 6 and 7. The primary and secondary acid scavengers are dosed in different ratios giving different scavenging efficiencies, and the impacts on the measurements carried out with EN 60754-2 and internal 3 are evaluated. RPK B-NT/8014 is an anti-pinking additive from Reagens commonly used to switch off discoloration when large quantities of MDH are introduced in PVC compounds. AS0-B is a potent acid scavenger produced by Reagens. Cabosil H5 is a fumed silica from Cabot, RI004 antimony trioxide from Quimialmel, and Kisuma 5A, a synthetic coated MDH produced by Kisuma.

EN 60754-2 and internal methods 2 and 3 use DDW internally produced by the ion exchange deionizer in

Table 5 with the quality according to the standard (pH between 5.50 and 7.50, and conductivity less than 0.5 mS/mm). Buffer and conductivity standard solutions from VWR International are the following:

- -

pH: 2.00, 4.01, 7.00, and 10.00,

- -

conductivity: 2.0, 8.4, 14.7, 141.3 mS/mm

2.2. Test Apparatuses

Table 5 gives the employed test apparatuses.

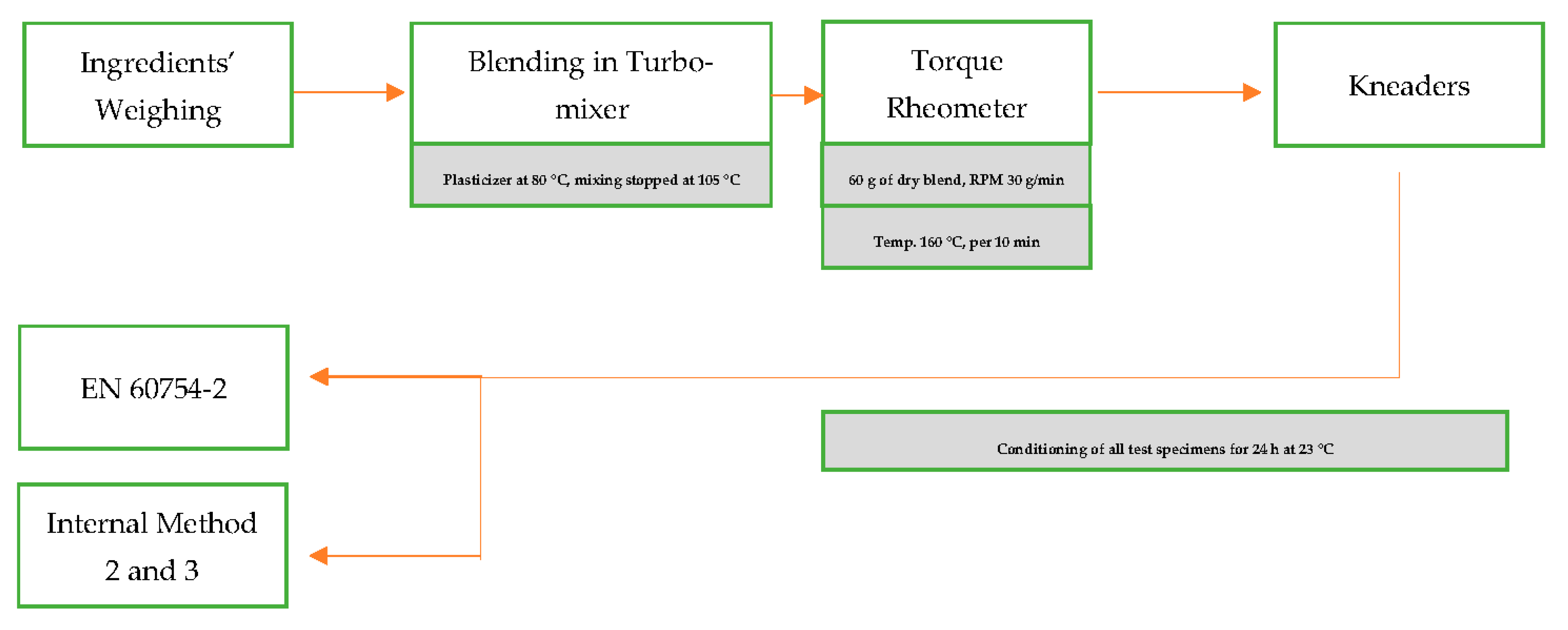

2.3. Sample preparation

The formulations in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 have been prepared in a turbo mixer, making the dry blends and then processing them in a torque rheometer for 10 minutes. The test specimens for EN 60754-2 and internal methods 2 and 3 have been derived from the kneaders.

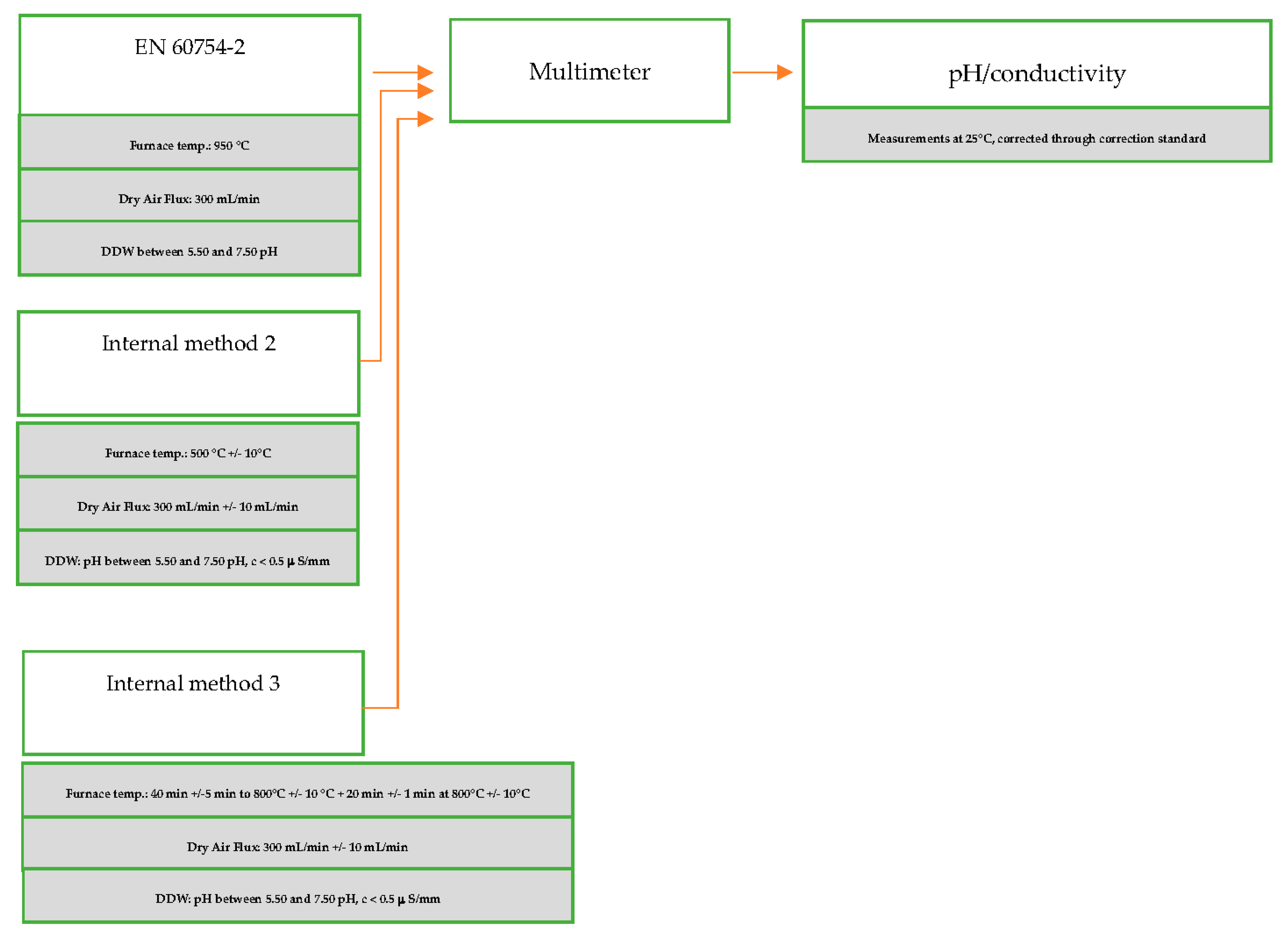

2.4. Internal tests and international technical standards used

Table 6 shows the technical standards and the main utilized conditions.

The procedures and the precautions in performing EN 60754-2 and internal methods 2 are described in detail in the technical standard, 5 and Parts I and II of this paper 6, 7

Internal method 3 follows this specific procedure: an empty combustion boat is introduced into the tube furnace through the sample carrier. The airflow is set between 290 and 310 ml/min, depending on the quartz tube geometry. The thermocouple is placed at the center of the tube furnace, the initial ramp is chosen, the heater is started, and the time is measured with a stopwatch. The ramp is selected to reach 800 °C +/- 10 °C in 40 min +/- 5 min and to maintain an isothermal condition of 800 °C +/- 10 °C for 20 min +/- 1 min. The heating rate is adjusted accordingly if temperatures and times exceed the above ranges. The conductivity of the water in the bubblers is checked to verify the possibility of contamination from previous tests. After determining the quartz tube's heating regime and cleaning status, the sample is weighed in the combustion boat (1.000 g +/- 0.001 g of material) and introduced into the tube furnace at room temperature through the sample carrier. The heater is switched on, and the stopwatch monitors the ramp. After 1 hour, the connectors are opened, the water from the bubbling devices and washing procedures is collected in a 1 L volumetric flask filled to the mark, and then pH and conductivity are measured. The method measures three replicates to calculate the mean value, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV).

3. Results

Table 7a,

Table 7b, and

Table 7c show pH and conductivity of the formulations in

Table 1 measured according respectively to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C, internal methods 3 and 2.

Table 8a gives the pH and conductivity of the formulations in

Table 2 measured according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C.

Table 8b pH and conductivity performing internal method 3.

Table 9a brings the pH and conductivity of the formulations in

Table 3 measured according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C.

Table 9b pH and conductivity obtained performing internal method 3.

Table 10a shows the pH and conductivity of the formulations in

Table 4 measured according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C.

Table 10b displays the pH and conductivities, performing internal method 3.

4. Discussion

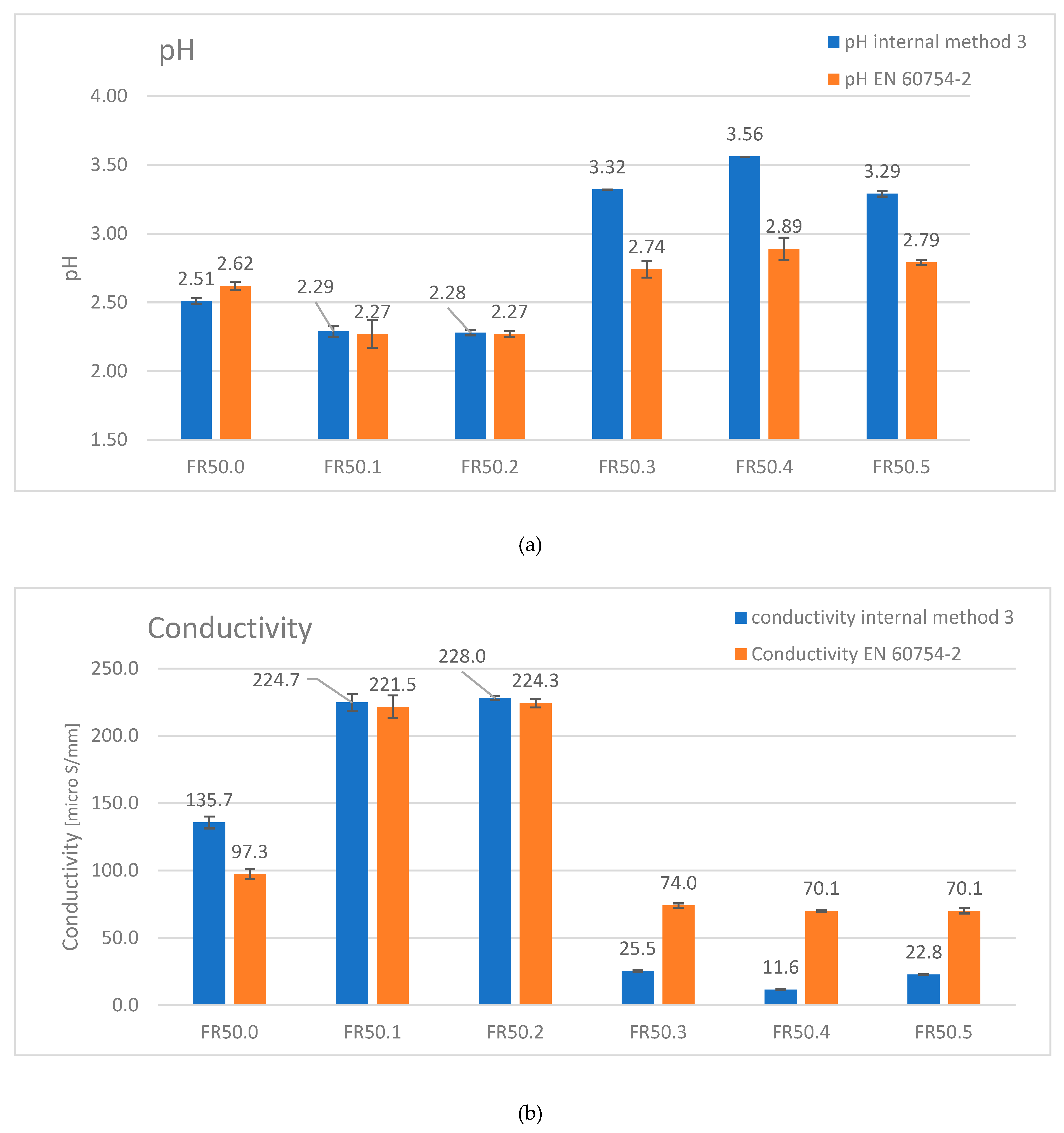

Figure 1a,b compare pH and conductivity achieved by formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 of

Table 1 (results reported in

Table 7a and

Table 7b) when performing EN 60754-2 at 950 °C and internal method 3. FR50.0, representing a typical non-flame retarded PVC jacket compound for cables, contains a GCC, which is a grade not actually good as acid scavenger. Internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 differ slightly in pH and conductivity. In particular, for FR50.0, EN 60754-2 only shows a slightly better smoke acidity compared to internal method 3. The phenomenon has been observed in Ref. 7, probably due to the formation of CaO, which more likely occurs at 950 °C than in the heating conditions of EN 60754-1. However, this effect disappears as particle size decreases and CaCO

3 increases its efficiency.

FR50.1 and FR50.2, containing ATH and MDH, respectively an inert and an ineffective acid scavenger, show high and comparable smoke acidity with both methods. Hence, the results obtained for FR50.0, FR50.1, and FR50.2 indicate that internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 work similarly when formulations are free of efficient acid scavengers. Nevertheless, the behavior in FR50.3, FR50.4, and FR50.5 is different. All these formulations contain potent acid scavengers at high temperatures that act in the condensed phase. In this case, the differences between the two heating regimes are significant, with EN 60754-2 showing rather higher smoke acidity than internal method 3.

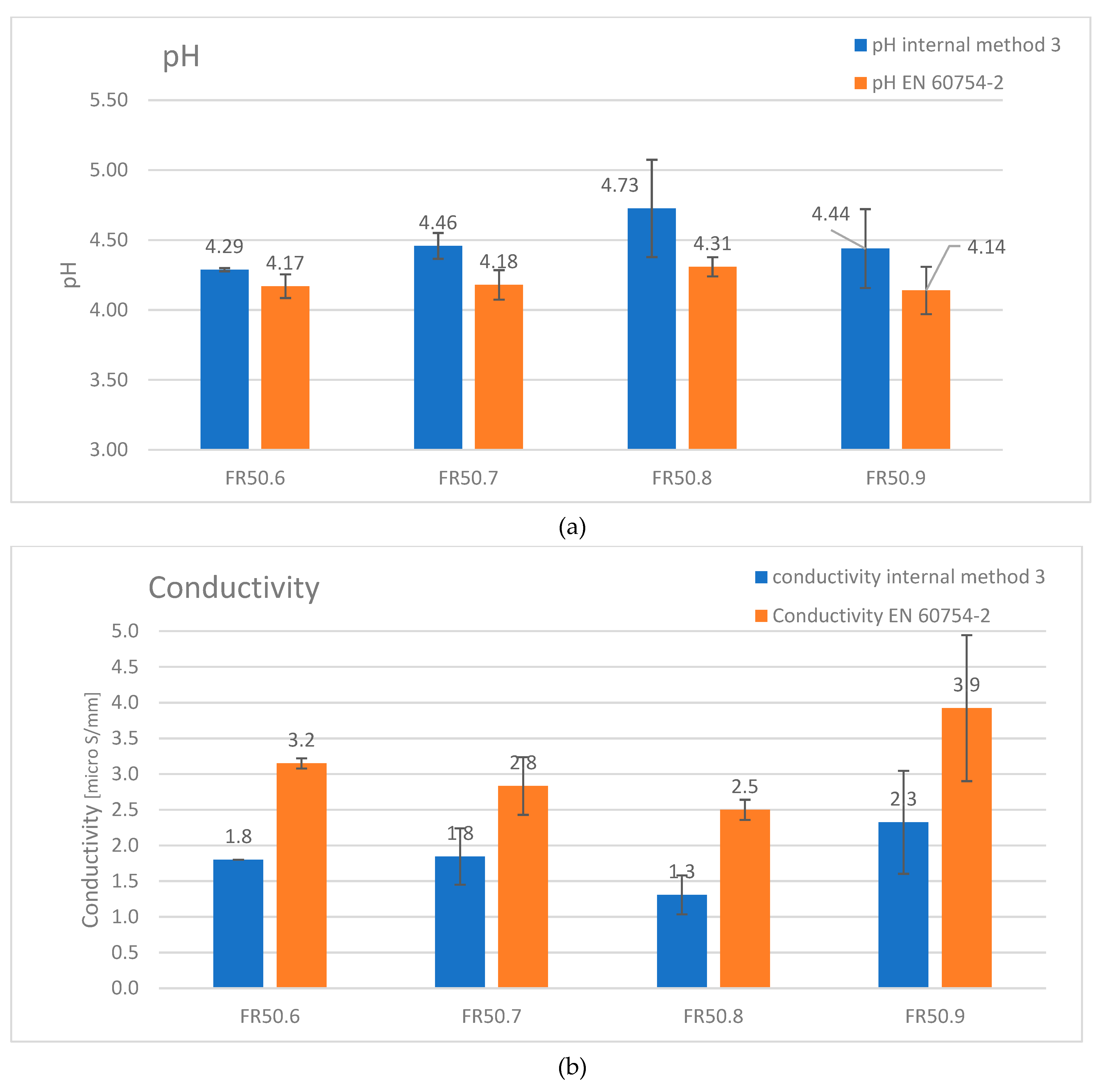

Figure 2a,b compare the pH and conductivity achieved by formulations FR50.6 – FR50.9 of

Table 2 (results reported in

Table 8a and

Table 8b when performing internal method 3 and EN 60754-2). In this case, the measurements concern the effect on acidity from AS-1B and AS-6B, which are potent acid scavengers at high temperatures, in combination with synthetic MDH. The compounds have high pH and low conductivity, and internal method 3 clearly shows low acidity, confirming the behavior of the samples FR50.3 – FR50.5 in

Table 1, which also contain potent acid scavengers. It is essential to highlight that as soon as the conductivity reaches values below 10 mS/mm, obtaining values with less than 5 % of the coefficient of variation, as requested by EN 60754-2 (

Table 8a and

Table 8b), becomes complex. In fact, the standard has many manual procedures and other sources of errors, exhaustively explained in Ref. 6 and Ref. 7, severely affecting the small values of the conductivity obtained with these formulations.

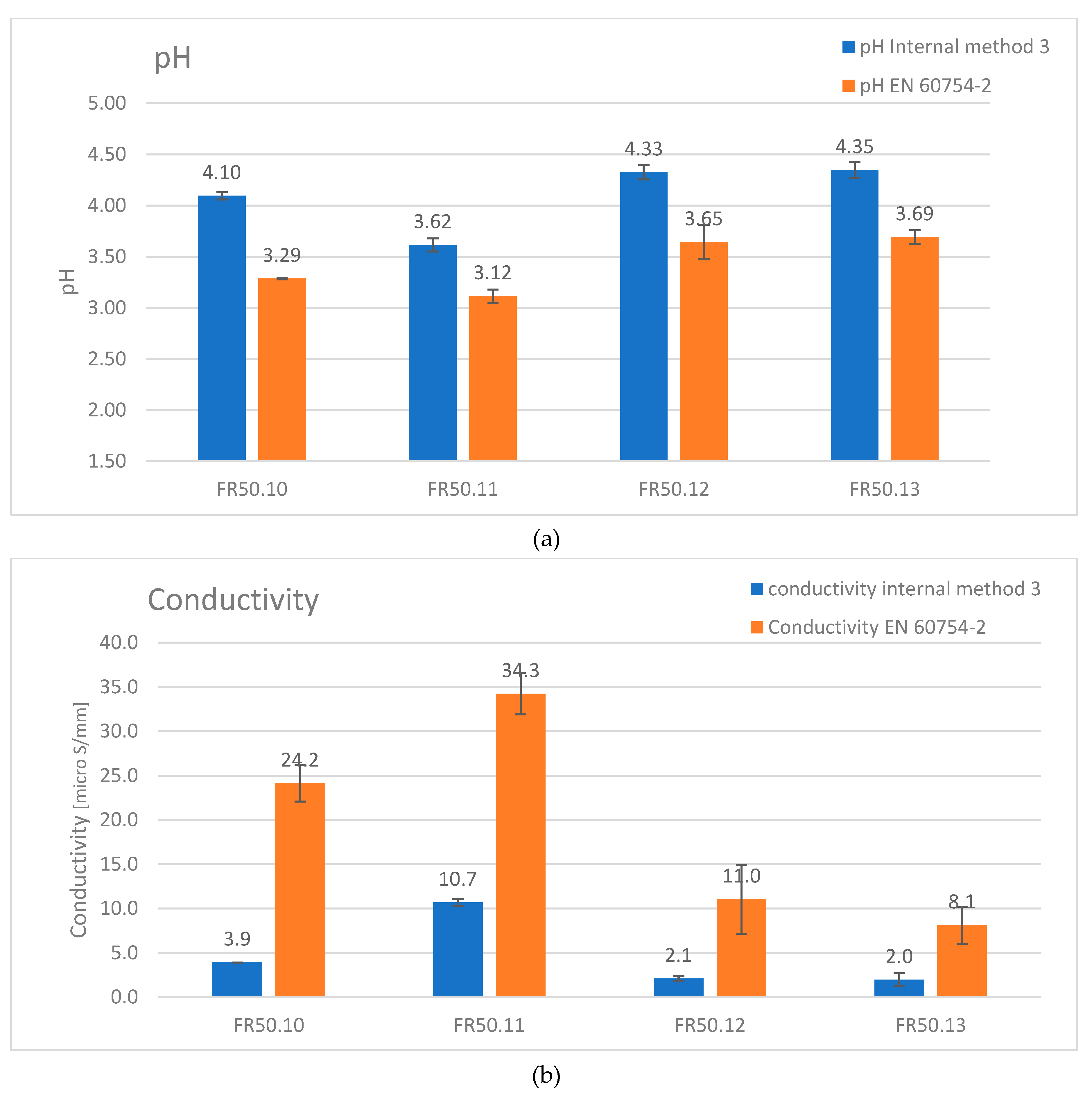

Figure 3a,b compare the pH and conductivity achieved by formulations FR50.10 – FR50.13 of

Table 3 (results reported in

Table 9a and

Table 9b), performing internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. In this set of formulations, UPCC and AS-0B, potent acid scavengers at high temperatures, are tested in combination with synthetic MDH, Kisuma 5A, and fumed silica. All formulations show extremely low acidity, reflecting the synergistic effect of UPCC and AS-0B with MDH in multiple-step reactions, as described in Ref. 6 and Ref. 7. AS-0B behaves better than UPCC. The use of fume silica, aiming to help the dispersion, is unsuccessful.

As for the formulations of the first two series (

Table 1 and

Table 2), internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 again show significant differences due to the different temperature regimes and final temperatures, with EN 60754-2 measuring higher acidity than internal method 3.

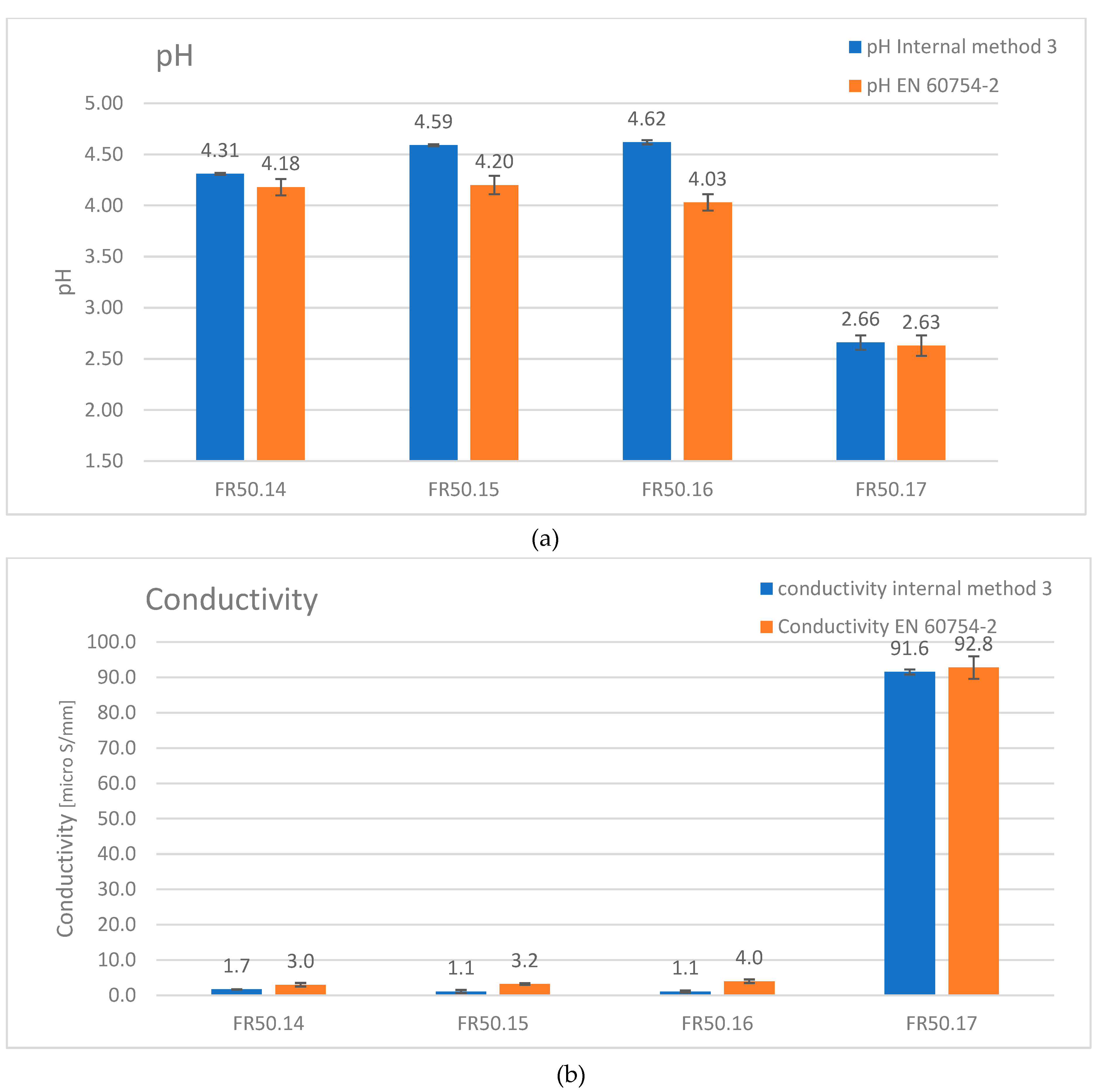

Figure 4a,b compare the pH and conductivity achieved by formulations FR50.14 – FR50.17 of

Table 4 (results reported in

Table 10a and

Table 10b), performing internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. In this series, AS-0B, AS-1B, and AS-6B, potent acid scavengers at high temperatures, are tested with milled brucite (FR50.14, FR50.15, and FR50.16). As with synthetic MDH, with brucite, the smoke acidity is also low, suggesting its synergistic effect between AS-0B, AS-1B, and AS-6B. Again, the internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 differences are considerable. On the other hand, FR50.17 is a typical CPR jacket compound used for matching the classification Cca s3 d1 a3 in PVC cables.

Figure 4a,b and

Table 10a and

Table 10b show that the new low-smoke acidity compounds exhibit acidity values of several orders below standard grade compounds for cable currently on the market. In this last case, being the compound free of potent acid scavengers, internal method 3 and EN 60754-2 give comparable measurements in terms of pH and conductivity.

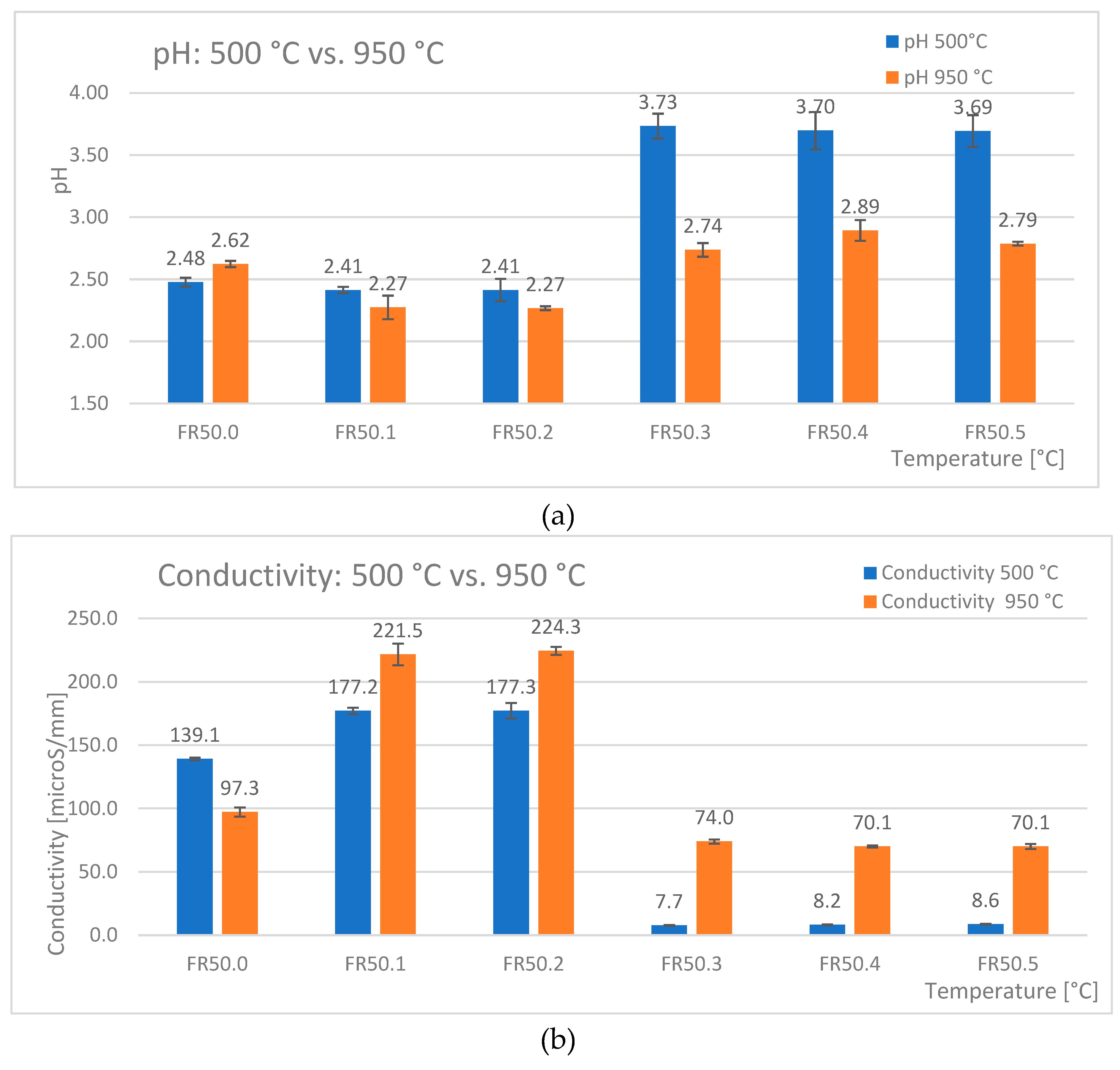

Figure 5a,b compare the pH and conductivity (

Table 7c) achieved by formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 of

Table 1, performing internal method 2 and EN 60754-2. The measurements have been performed in isothermal conditions, respectively, at 500 °C and 950 °C and clearly show that applying a lower temperature of 500 °C, in the presence of effective acid scavengers, the HCl in the gas phase is highly reduced (see FR50.3 – FR50.5). The behavior of FR50.0 in isothermal conditions at 500 °C recalls that with the internal method 3. The formation of CaO at 500 °C is unlike, and the efficiency at 950 °C is higher.

All these data clearly indicate that if a powerful acid scavenger has time to react with HCl, as it happens at lower temperatures (internal method 2, isothermal) and lower temperatures with a slower heating regime (internal method 3), it can trap HCl in the condensed phase with higher efficiencies. On the other hand, the higher temperatures and fast heating regimes of EN 60754-2 hinder its action: the acid scavenger at high temperatures cannot compete with the rapid HCl evolution during PVC compound combustion, and HCl escapes quickly into the gas phase, decreasing the pH and increasing the conductivity of the solutions in the bubblers. In the absence of effective acid scavengers, both standards show comparable values.

The interference of heating regimes and final temperatures in tube furnace tests for determining HCl was well explained in Ref. 22 in 1986. Here Chandler, Hirschler, and Smith highlighted that humidity, soot formation, dimensions of the combustion boat, and temperature regimes could affect the results of the method. In the paper, the acid scavenger in PVC compounds was CaCO3, but no information regarding its particle size was given. Isothermal conditions at 650 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C and 950 °C were applied, showing an increase in the emission of HCl as temperature increases. The scavenging efficiency in isothermal was also lower than performing a temperature gradient of 10 °C per minute. All these aspects confirmed that CaCO3, as an acid scavenger, suffers from high temperatures and fast heating rates. They justified the behavior with these specific phrases.

"It is clear that the higher the temperature at which the tube furnace test is carried out, the higher the HC1 emission will be".

"The lower efficiency during isothermal runs (after 3 weight loss stages) than during gradual heating runs…., coupled with the fact that there is a significantly larger weight loss in the first stage of the isothermal runs, indicates that there is a much greater likelihood of HCI being emitted before it has had the opportunity of reacting with the filler."

The acid scavengers used in our paper, currently used such as UPCC or novel such as AS-XB series, confirm the same behavior with a collapse of their efficiencies as temperature increases and when the heating regime accelerates.

5. Conclusion

When an acid scavenger, acting in the condensed phase at high temperatures, is added to the PVC compound, EN 60754-2 performed at 950 °C assesses higher smoke acidity than internal method 3, with a heating regime up to 800 °C. On the contrary, if acid scavengers are absent, inert, or ineffective, both tests show comparable acidity values. Depending on the acid scavengers in the formulations, the gap between EN 60754-2 and internal 3 can become significant. For example, in

Figure 1, FR50.3 gives a value about 3 times lower in conductivity when a gradual heating regime up to 800 °C is set, becoming even about 10 times less when EN 60754-2 is run isothermally at 500 °C, using internal method 2.

This behavior confirms what Ref. 7 reports, where the efficiencies of some acid scavengers have been measured in isothermal conditions at different temperatures. What speeds up the evolution of HCl, such as high temperatures and quick heating regimes, hinders the action of the acid scavengers during PVC compound combustion. Therefore, acid scavengers cannot trap HCl released quickly in the gas phase, increasing the effluents' acidity. Thus, the higher the temperature or faster the heating regime, the quicker the evolution and lower the probability of acid scavenger trapping HCl, as highlighted in Ref. 22 and Ref. 23.

In conclusion, EN 13501-6 aims to meet the request of CPR according to its second basic requirement for construction works, i.e., safety in case of fire. It requires the standard EN 60754-2 to assess acidity indirectly at temperatures between 935 °C and 965 °C in isothermal conditions. It must be highlighted that room fires can have different stages with different temperatures and heat flows.13 Specifically, temperatures can rise between 300 °C and 600 °C in the ignition and developing fire stages, capable of reaching from 650 °C up to 1100 °C in the fully developed stage.13 Specifically, those temperatures obliterate entirely the action of the powerful HCl scavengers in low-smoke acidity compounds for cables. Acid scavengers, on the other hand, work efficiently (even up to 10 times better) when a heating regime or pre-flash-over temperatures are used. We must highlight that acid scavengers, such as UPCC or fine particle size GCC, are commonly used as HCl scavengers to reduce the effluents' acidity in many standards out of the scope of CPR. However, the new generation of acid scavengers at high temperatures is more efficient than the old generation. Therefore, they are promising substances for further development, aiming to meet the best additional classifications for acidity according to CPR.

However, those considerations show how EN 60754-2 is weak in its indirect assessment of acidity. It is probably a useless device to foresee if the material of an item can be a real problem in terms of its capability of releasing HCl in the gas phase. That is not only because in real fire scenarios, HCl decays, generating less acidity than expected, and travels only a short distance from where the fire originated.14 But also because EN 60754-2 assesses the acidity at typical temperatures of fully developed fires.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.; methodology, G.S., F.D., I.B., M.P. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.; writing—review and editing, G.S., F.D., I.B., M.P. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to acknowledge Ing. Carlo Ciotti, Emma Sarti, all PVC Forum Italia, and the PVC4cables staff.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Abbreviations

| PVC |

Poly(vinyl chloride); |

| HCl |

Hydrogen chloride; |

| EU |

European Union; |

| CPD |

Construction Product Directive; |

| CPR |

Construction Product Regulation; |

| UPCC |

Precipitated Calcium Carbonate; |

| GCC |

Ground Calcium Carbonate; |

| Phr |

Part per Hundred Resin; |

| DINP |

Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate; |

| ESBO |

Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil; |

| COS |

Calcium Organic Stabilizer; |

| DDW |

Double Deionized Water; |

| M |

Mean; |

| SD |

Standard Deviation; |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation; |

| MCC |

Micro Combustion Calorimetry |

Appendix A. A schematic diagram of the sample preparation and testing process

Figure A1.

A schematic diagram of the sample preparation.

Figure A1.

A schematic diagram of the sample preparation.

Figure A2.

A schematic diagram of the testing process and main conditions.

Figure A2.

A schematic diagram of the testing process and main conditions.

References

- Regulation (EU) No 305/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 March 2011 laying down harmonised conditions for the marketing of construction products and repealing Council Directive 89/106/EEC. Consolidate version available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02011R0305-20210716 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- EN13501-1:2018; Fire classification of construction products and building elements - Part 1: Classification using data from reaction to fire tests. CEN: Brussels, Belgium. 2019. Available online: https://store.uni.com/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- EN 13501-6:2018; Fire classification of construction products and building elements. Classification using data from reaction to fire tests on power, control and communication cables. CEN: Brussels, Belgium. 2018. Available online: https://store.uni.com/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- EN 50575:2014+A1:2016; Power, control and communication cables - Cables for general applications in construction works subject to reaction to fire requirements. Available online: https://my.ceinorme.it/home.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- EN 60754-2:2014/A1:2020; Test on Gases Evolved during Combustion of Materials from Cables—Part 2: Determination of Acidity (by pH Measurement) and conductivity. CENELEC: Brussels, Belgium. 2020. Available online: https://my.ceinorme.it/home.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Sarti, G. A New Perspective on Hydrogen Chloride Scavenging at High Temperatures for Reducing the Smoke Acidity of PVC Cables in Fires. I: An Overview of the Theory, Test Methods, and the European Union Regulatory Status. Fire 2022, 5, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, G. A New Perspective on Hydrogen Chloride Scavenging at High Temperatures for Reducing the Smoke Acidity of PVC Cables in Fires. II: Some Examples of Acid Scavengers at High Temperatures in the Condensed Phase. Fire 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 60754-1; Test on Gases Evolved during Combustion of Materials from Cables—Part 1: Determination of the Halogen Acid Gas Content. CENELEC: Brussels, Belgium. 2014. Available online: https://my.ceinorme.it/home.html (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Schartel, B.; Hull, T. R. Development of fire-retarded materials—Interpretation of cone calorimeter data. FAM 2007, 31, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V. Specimen Heat Fluxes for Bench-scale Heat Release Rate Testing. Fire and Materials. 1995, 19, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schartel, B.; Kebelmann, K. Fire Testing for the Development of Flame Retardant Polymeric Materials from: Flame Retardant Polymeric Materials, A Handbook CRC Press. 2019. Available online: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.1201/b22345-3.

- Hirschler, M. Poly(vinyl chloride) and its fire properties. FAM 2017, 41, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V; Peacock, R.D. Heat release rate: The single most important variable in fire hazard. Fire Safety Journal 1992, 18, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschler, M. Fire safety, smoke toxicity, and acidity. In Proceedings of the Flame Retardants 2006, London, UK. 14–15/02/2006.

- Sarti, G.; Piana, M. PVC in cables for building and construction. Can the "European approach" be considered a good example for other countries? Acad. Lett. 2022, 5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarti, G.; Piana, M. PVC cables and smoke acidity: A review comparing performances of old and new compounds. In Proceedings of the AMI Cables 2020, Duesseldorf, Germany, 3–5 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti, G.; Piana, M. Smoke acidity and a new generation of PVC formulations for cables. In Proceedings of the AMI Formulation 2021, Cologne, Germany, 16–18 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sarti, G. Developing and improving fire performance and safety in PVC. In Proceedings of the Future of PVC Compounding, Production & Recycling, online, 24–25 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Commercial GCC purchased by Umbriafiller. Available on request: https://www.umbriafiller.com (accessed on 01/06/2023).

- Kipouros, G.J.; Sadoway, D.R. A thermochemical analysis of the production of anhydrous MgCl2. J. Light Met. 2001, 1, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galwey, A.K.; Laverty, G.M. The thermal decomposition of magnesium chloride dihydrate. Thermochim. Acta 1989, 138, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commercial PCC Purchased by Imerys. Available online: https://www.imerys-performance-minerals.com/system/files/2021-02/DATPCC_Winnofil_S_LSK_EN_2019-07.pdf (accessed on 01/06/2023).

- Chandler, L.A.; Hirschler Smith, G.F. A heated tube furnace test for the emission of acid gas from PVC wire coating materials: Effects of experimental procedures and mechanistic considerations. Eur. Polym. J. 1987, 23, 51–61 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, I. Characterization of PVC compounds and evaluation of their fire performance, focusing on the comparison between EN 60754-1 and EN 60754-2 in the assessment of the smoke acidity, Master degree Thesis, University of Bologna, Bologna, 10/2021. Available at: https://www.pvc4cables.org/images/assessment_of_the_smoke_acidity.pdf. (accessed on 01/06/2023).. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported. FR50.0-FR50.2 without efficient acid scavengers, FR50.3 – FR50.5 with efficient acid scavengers.

Figure 1.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported. FR50.0-FR50.2 without efficient acid scavengers, FR50.3 – FR50.5 with efficient acid scavengers.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.6 – FR50.9 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 2.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.6 – FR50.9 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.10 – FR50.13 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.10 – FR50.13 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 4.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.14 – FR50.17 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 4.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.14 – FR50.17 measured with internal method 3 (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars). SD is reported.

Figure 5.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 measured with internal method 2 at 500 °C (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars) at 950 °C. SD is reported.

Figure 5.

Comparison of pH (a) and conductivity (b) of formulations FR50.0 – FR50.5 measured with internal method 2 at 500 °C (blue bars) and EN 60754-2 (orange bars) at 950 °C. SD is reported.

Table 1.

First series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. UPCC means Ultrafine Precipitated Calcium Carbonate. HTAS stands for High Temperature Acid Scavengers.

Table 1.

First series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. UPCC means Ultrafine Precipitated Calcium Carbonate. HTAS stands for High Temperature Acid Scavengers.

| Raw Materials |

Trade Name |

FR50.0

[phr] |

FR50.1

[phr] |

FR50.2

[phr] |

FR50.3

[phr] |

FR50.4

[phr] |

FR50.5

[phr] |

| PVC |

Inovyn 271 PC |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| DINP |

Diplast N |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

| ESBO |

Reaflex EP/6 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

| Antioxidant |

Arenox A10 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| COS |

RPK B-CV/3037 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| CaCO3

|

Riochim |

90 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Al(OH)3

|

Apyral 40 CD |

0 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Mg(OH)2

|

Ecopyren 3.5 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| UPCC |

Winnofil S |

0 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

0 |

0 |

| HTAS 1 |

AS-1B |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

0 |

| HTAS 2 |

AS-6B |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

90 |

Table 2.

Second series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. HTAS means High Temperature Acid Scavengers.

Table 2.

Second series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. HTAS means High Temperature Acid Scavengers.

| Raw Materials |

Trade Name |

FR50.6

[phr] |

FR50.7

[phr] |

FR50.8

[phr] |

FR950.9

[phr] |

| PVC |

Inovyn 271 PC |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| DINP |

Diplast N |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

| ESBO |

Reaflex EP/6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

| Mg(OH)2

|

Kisuma 5A |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

| Antioxidant |

Arenox A10 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| COS |

RPK B-CV/3037 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| HTAS 1 |

AS-1B |

123.0 |

123.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| HTAS 2 |

AS-6B |

0.0 |

0.0 |

123.0 |

123.0 |

| Anti Pinking |

RPK B-NT/8014 |

0.0 |

6.0 |

0.0 |

6.0 |

Table 3.

Third series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. UPCC means Ultrafine Precipitated Calcium Carbonate. HTAS High Temperature Acid Scavenger.

Table 3.

Third series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. UPCC means Ultrafine Precipitated Calcium Carbonate. HTAS High Temperature Acid Scavenger.

| Raw Materials |

Trade Name |

FR50.10

[phr] |

FR50.11

[phr] |

FR50.12

[phr] |

FR950.13

[phr] |

| PVC |

Inovyn 271 PC |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| DINP |

Diplast N |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

| ESBO |

Reaflex EP/6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

| Antioxidant |

Arenox A10 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| COS |

RPK B-CV/3037 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| Mg(OH)2

|

Kisuma 5A |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

| UPCC |

Winnofil S |

90.0 |

90.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| Fumed Silica |

Cabosil H5 |

0.0 |

15.0 |

0.0 |

15.0 |

| HTAS 3 |

AS-0B |

0.0 |

0.0 |

123.0 |

123.0 |

Table 4.

Forth series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. ATO means antimony trioxide and HTAS High Temperature Acid Scavenger.

Table 4.

Forth series of formulations: DINP means Di Iso Nonyl Phthalate. ESBO stands for Epoxidized Soy Bean Oil. The used antioxidant is Arenox A10, which is Pentaerythritol tetrakis(3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate), CAS number 6683-19-8. COS stands for Calcium Organic Stabilizer. ATO means antimony trioxide and HTAS High Temperature Acid Scavenger.

| Raw Materials |

Trade Name |

FR50.14

[phr] |

FR50.15

[phr] |

FR50.16

[phr] |

FR50.17

[phr] |

| PVC |

Inovyn 271 PC |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| DINP |

Diplast N |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

50.0 |

| ESBO |

Reaflex EP/6 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

| Mg(OH)2

|

Ecopyren 3.5 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

30.0 |

| Antioxidant |

Arenox A10 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

| COS |

RPK B-CV/3037 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| ATO |

RI004 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

| CaCO3

|

Riochim |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

65.0 |

| HTAS 1 |

AS-1B |

123.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| HTAS 2 |

AS-6B |

0.0 |

123.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| HTAS 3 |

AS-0B |

0.0 |

0.0 |

123.0 |

0.0 |

Table 5.

Main test apparatuses utilized.

Table 5.

Main test apparatuses utilized.

| Test apparatus |

Producer |

Model |

Additional Info's |

| Torque Rheometer |

Brabender |

Plastograph EC |

50 CC chamber, 30 rpm, 60 g sample mass, 160 °C per 10 minutes. |

| Halogen Acid Gas testapparatus |

SA Associates |

Standard model |

Porcelain combustion boats. |

| Multimeter |

Mettler Toledo |

S213 standard kit |

|

| Conductivity electrode |

Mettler Toledo |

S213 standard kit |

Reference thermocouple adjusting temperature fluctuation. |

| pH electrode |

Mettler Toledo |

S213 standard kit |

Reference thermocouple adjusting temperature fluctuation. |

| Ion Exchange Deionizer |

Culligan Pharma |

System 20 |

|

Table 6.

Tests for assessing acidity.

Table 6.

Tests for assessing acidity.

| Technical standard |

Measurement |

Temperature |

Note |

| EN 60754-2 |

pH and conductivity |

Isothermal at 950 °C |

The general method, according to the 2014 version. |

| Internal method 2 |

pH and conductivity |

Isothermal at 500 °C |

The general method, according to the 2014 version. |

| Internal method 3 |

pH and conductivity |

23°C – 800 °C in 40 min800 °C per 20 min |

EN 60754-2 carried out with the thermal profile of EN 60754-1 |

Table 7a.

pH and conductivities of the formulation in

Table 1, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 7a.

pH and conductivities of the formulation in

Table 1, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.0 |

FR50.1 |

FR50.2 |

FR50.3 |

FR50.4 |

FR50.5 |

| pH |

2.62 |

2.27 |

2.27 |

2.74 |

2.89 |

2.79 |

| SDpH |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.08 |

0.02 |

| CVpH [%] |

1.15 |

4.41 |

0.88 |

2.19 |

2.77 |

0.72 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

97.3 |

221.5 |

224.3 |

74.0 |

70.1 |

70.1 |

| SDc |

3.7 |

8.4 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

| CVc [%] |

3.8 |

3.8 |

1.4 |

2.2 |

1.0 |

2.9 |

Table 7b.

pH and conductivity of the formulation in

Table 1, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 7b.

pH and conductivity of the formulation in

Table 1, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.0 |

FR50.1 |

FR50.2 |

FR50.3 |

FR50.4 |

FR50.5 |

| pH |

2.51 |

2.29 |

2.28 |

3.32 |

3.56 |

3.29 |

| SDpH |

0.02 |

0.04 |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

| CVpH [%] |

0.80 |

1.75 |

0.88 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.61 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

135.7 |

224.7 |

228.0 |

25.5 |

11.6 |

22.8 |

| SDc |

4.4 |

6.1 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

| CVc [%] |

3.2 |

2.7 |

0.7 |

2.7 |

1.7 |

0.4 |

Table 7c.

pH and conductivity of the formulation in

Table 1, according to internal method 2 at 500 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 7c.

pH and conductivity of the formulation in

Table 1, according to internal method 2 at 500 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation à |

FR50.0 |

FR50.1 |

FR50.2 |

FR50.3 |

FR50.4 |

FR50.5 |

| pH at 500 °C |

2.48 |

2.41 |

2.41 |

3.73 |

3.70 |

3.69 |

| SDpH |

0.04 |

0.03 |

0.09 |

0.10 |

0.15 |

0.13 |

| CVpH [%] |

1.61 |

1.24 |

3.73 |

2.68 |

4.05 |

3.52 |

| Conductivity at 500 °C [mS/mm] |

139.1 |

177.2 |

177.3 |

7.7 |

8.2 |

8.6 |

| SDc |

1.2 |

2.5 |

6.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

| CVc [%] |

0.9 |

1.4 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

4.9 |

3.5 |

Table 8a.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 2, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 8a.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 2, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.6 |

FR50.7 |

FR50.8 |

FR50.9 |

| pH |

4.17 |

4.18 |

4.31 |

4.14 |

| SDpH |

0.08 |

0.11 |

0.07 |

0.17 |

| CVpH [%] |

1.92 |

2.63 |

1.62 |

4.11 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

3.2 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

3.9 |

| SDc |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

| CVc [%] |

3.1 |

14.3 |

4.0 |

25.6 |

Table 8b.

pH and conductivities of formulations in

Table 2, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 8b.

pH and conductivities of formulations in

Table 2, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.6 |

FR50.7 |

FR50.8 |

FR50.9 |

| pH |

4.29 |

4.46 |

4.73 |

4.44 |

| SDpH |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0.35 |

0.28 |

| CVpH [%] |

0.23 |

2.02 |

7.40 |

6.31 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

1.8 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

2.3 |

| SDc |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

| CVc [%] |

0.0 |

22.2 |

23.1 |

30.4 |

Table 9a.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 3, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 9a.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 3, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.10 |

FR50.11 |

FR50.12 |

FR50.13 |

| pH |

3.29 |

3.12 |

3.65 |

3.69 |

| SDpH |

0.01 |

0.06 |

0.17 |

0.07 |

| CVpH [%] |

0.30 |

1.92 |

4.66 |

1.90 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

24.2 |

34.3 |

11.0 |

8.1 |

| SDc |

2.1 |

2.3 |

3.9 |

2.1 |

| CVc [%] |

8.7 |

6.8 |

35.2 |

25.9 |

Table 9b.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 3, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 9b.

pH and conductivity of formulations in

Table 3, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.10 |

FR50.11 |

FR50.12 |

FR50.13 |

| pH |

4.10 |

3.62 |

4.33 |

4.35 |

| SDpH |

0.04 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

| CVpH [%] |

0.98 |

1.66 |

1.62 |

1.84 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

3.9 |

10.7 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

| SDc |

0.3 |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

| CVc [%] |

7.7 |

15.0 |

33.3 |

10.0 |

Table 10a.

pH and conductivities of formulation in

Table 4, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 10a.

pH and conductivities of formulation in

Table 4, according to EN 60754-2 at 950 °C. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.14 |

FR50.15 |

FR50.16 |

FR50.17 |

| pH |

4.18 |

4.20 |

4.03 |

2.63 |

| SDpH |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

| CVpH [%] |

1.91 |

2.14 |

1.99 |

3.80 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

3.0 |

3.2 |

4.0 |

92.8 |

| SDc |

0.5 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

3.2 |

| CVc [%] |

16.7 |

6.3 |

12.5 |

3.4 |

Table 10b.

pH and conductivities of formulation in

Table 4, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

Table 10b.

pH and conductivities of formulation in

Table 4, according to internal method 3. The mean values, standard deviations, and coefficient of variation are reported.

| Formulation → |

FR50.14 |

FR50.15 |

FR50.16 |

FR50.17 |

| pH |

4.31 |

4.59 |

4.62 |

2.66 |

| SDpH |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.07 |

| CVpH [%] |

0.23 |

0.22 |

0.43 |

2.63 |

| Conductivity [mS/mm] |

1.7 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

91.6 |

| SDc |

0.0 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.9 |

| CVc [%] |

0.0 |

9.1 |

9.1 |

1.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).