Submitted:

21 July 2023

Posted:

24 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.3. Treatment methods

2.4. Outcome measures

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

3.2. Clinical efficiency

3.3. Treatment compliance

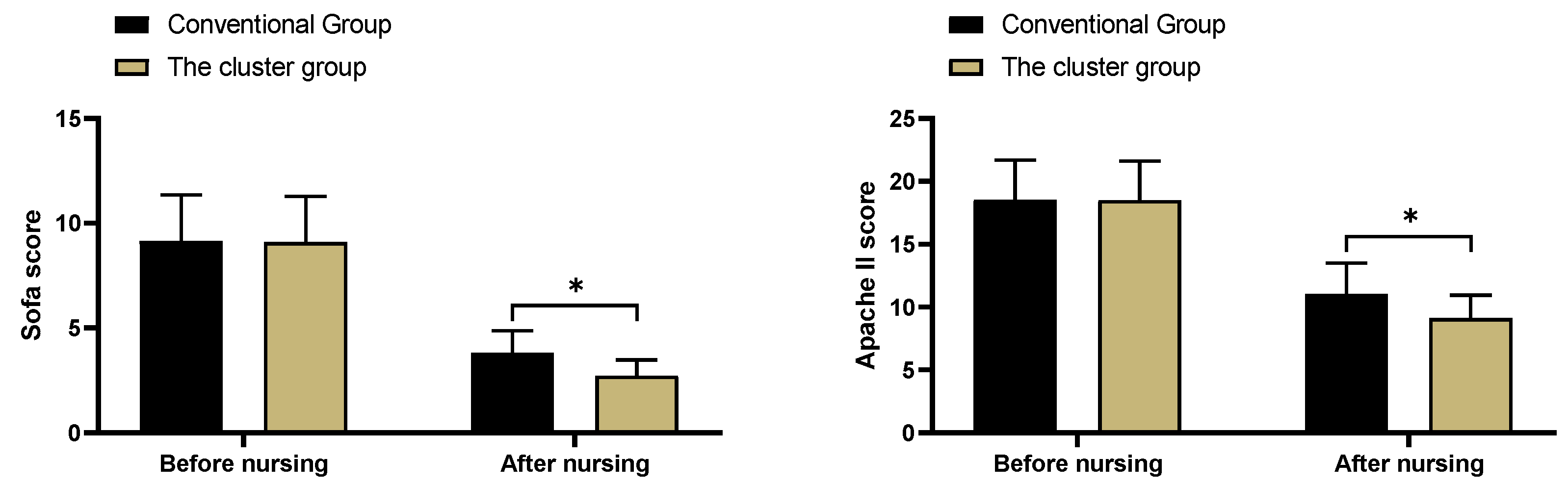

3.4. SOFA scores and APACHE II scores

3.5. Intestinal barrier function

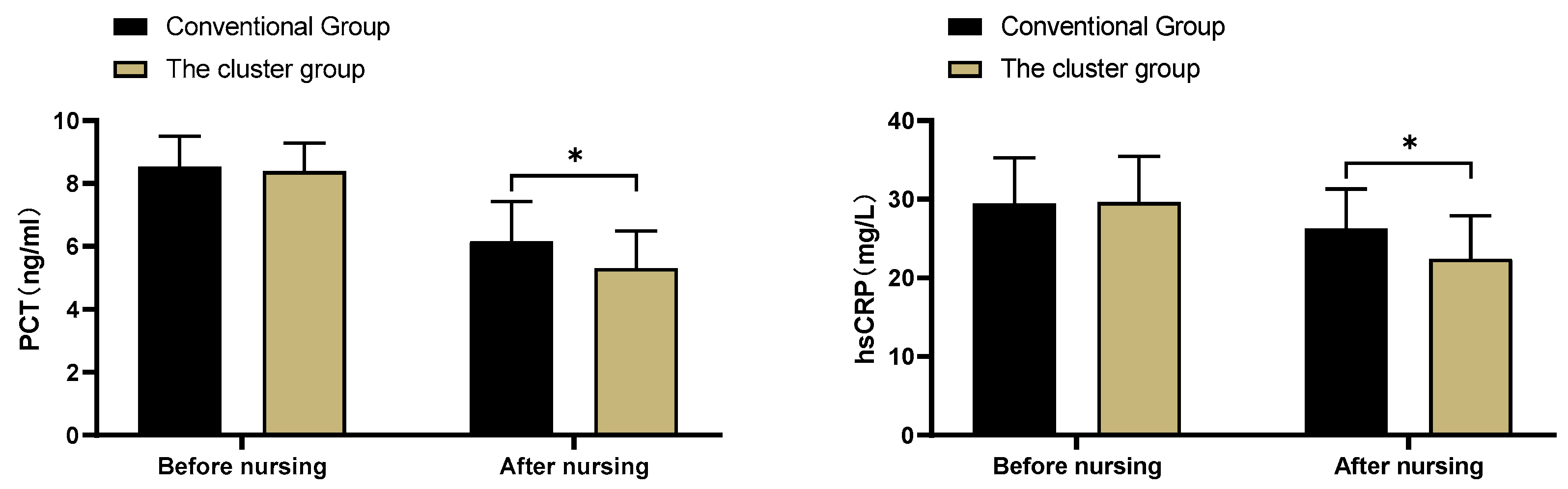

3.6. Inflammatory factor levels

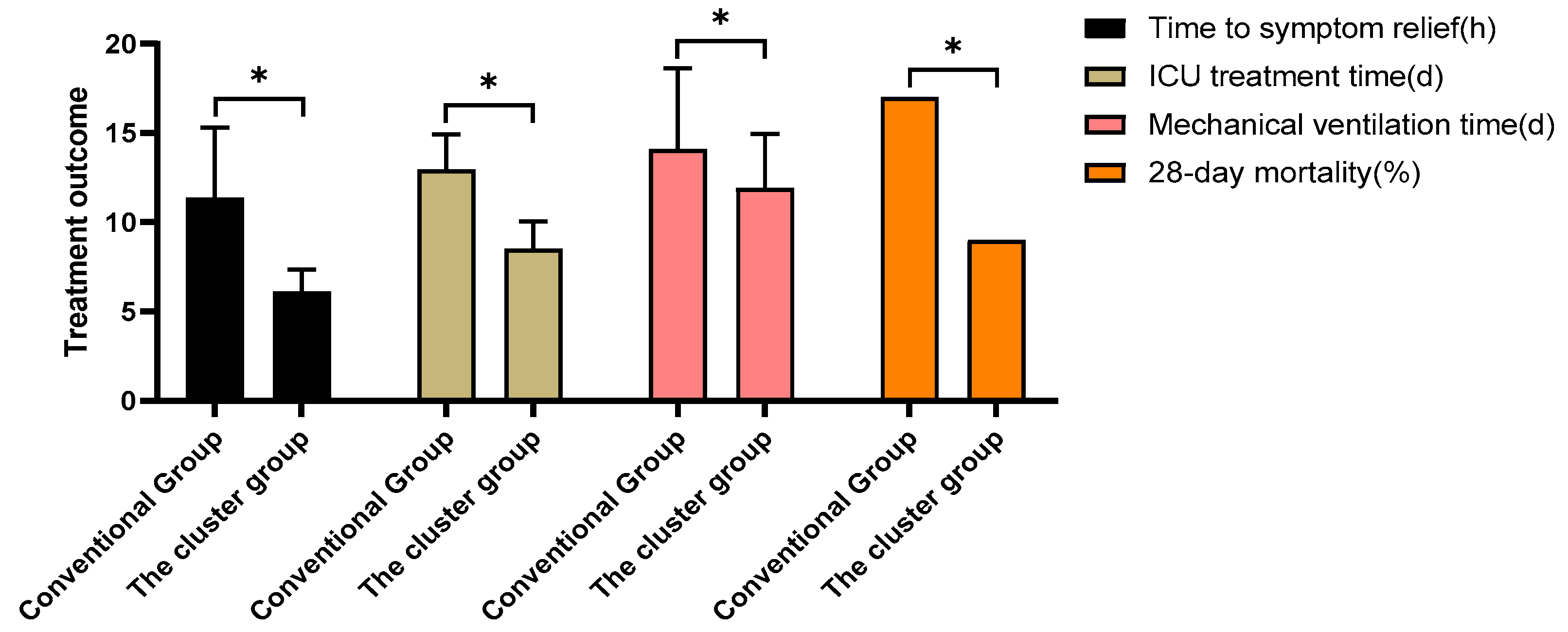

3.7. Treatment outcomes

3.8. Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Font, M.D., B. Thyagarajan, and A.K. Khanna, Sepsis and Septic Shock - Basics of diagnosis, pathophysiology and clinical decision making. Med Clin North Am, 2020. 104(4): p. 573-585. [CrossRef]

- Shankar-Hari, M., et al., Developing a New Definition and Assessing New Clinical Criteria for Septic Shock: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama, 2016. 315(8): p. 775-87. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A., B. Rush, and J. Boyd, Pathophysiology of Septic Shock. Crit Care Clin, 2018. 34(1): p. 43-61. [CrossRef]

- Osborn, T.M., Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Trials (ProCESS, ARISE, ProMISe): What is Optimal Resuscitation? Crit Care Clin, 2017. 33(2): p. 323-344. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K., B. Venkatesh, and S. Finfer, Sepsis and septic shock: current approaches to management. Intern Med J, 2019. 49(2): p. 160-170. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.X., et al., Study on clinical nursing pathway to promote the effective implementation of sepsis bundle in septic shock. Eur J Med Res, 2021. 26(1): p. 69. [CrossRef]

- [Consensus on diagnosis and treatment of invasive fungal infection in patients with severe liver disease]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi, 2022. 30(2): p. 159-168.

- Arabi, Y.M., et al., Electronic early notification of sepsis in hospitalized ward patients: a study protocol for a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 2021. 22(1): p. 695. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., et al., [Visualized analysis of literature on sepsis caused by Gram positive bacteria in SinoMed]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue, 2020. 32(3): p. 294-300.

- Kowalkowski, M., et al., Protocol for a two-arm pragmatic stepped-wedge hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial evaluating Engagement and Collaborative Management to Proactively Advance Sepsis Survivorship (ENCOMPASS). BMC Health Serv Res, 2021. 21(1): p. 544. [CrossRef]

- Tan, D., et al., Patient, provider, and system factors that contribute to health care-associated infection and sepsis development in patients after a traumatic injury: An integrative review. Aust Crit Care, 2021. 34(3): p. 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.L., et al., Nurses' knowledge and confidence in recognizing and managing patients with sepsis: A multi-site cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Amer, Y.S., et al., Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for neonatal sepsis using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II Instrument: A systematic review of neonatal guidelines. Front Pediatr, 2022. 10: p. 891572. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, H., et al., Cluster Analysis in Nursing Research: An Introduction, Historical Perspective, and Future Directions. West J Nurs Res, 2018. 40(11): p. 1658-1676. [CrossRef]

- Trochet, C., et al., [Septic shock, organisation and nursing care]. Rev Infirm, 2020. 69(260-261): p. 22-24.

- Alp, E., H. Erdem, and J. Rello, Management of septic shock and severe infections in migrants and returning travelers requiring critical care. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2016. 35(4): p. 527-33. [CrossRef]

- Dalimonte, M.A., J.R. DeGrado, and K.E. Anger, Vasoactive Agents for Adult Septic Shock: An Update and Review. J Pharm Pract, 2020. 33(4): p. 523-532. [CrossRef]

- Bughrara, N., J.L. Diaz-Gomez, and A. Pustavoitau, Perioperative Management of Patients with Sepsis and Septic Shock, Part II: Ultrasound Support for Resuscitation. Anesthesiol Clin, 2020. 38(1): p. 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Berg, D. and H. Gerlach, Recent advances in understanding and managing sepsis. F1000Res, 2018. 7. [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.J., A. Shukla, and D.K. Heyland, Enteral nutrition in septic shock: A pathophysiologic conundrum. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr, 2021. 45(S2): p. 74-78. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, M., Early goal-directed therapy versus usual care in the management of septic shock. Cjem, 2017. 19(1): p. 65-67. [CrossRef]

| Routine group (n=47) | Care bundles group (n=47) | t/x² | P | |

| Sex | 0.047 | 0.829 | ||

| Male | 31 | 30 | ||

| Female | 16 | 17 | ||

| Age (year) | 22-78 | 21-77 | ||

| Mean age (year) | 53.47±8.22 | 53.52±8.19 | -0.03 | 0.976 |

| Site of infection | ||||

| Lung | 22 | 19 | 0.389 | 0.533 |

| Biliary tract | 9 | 8 | 0.072 | 0.789 |

| Abdominal cavity | 7 | 8 | 0.079 | 0.778 |

| Urinary system | 4 | 6 | 0.448 | 0.503 |

| Other | 5 | 6 | 0.103 | 0.748 |

| Education level | 0.174 | 0.677 | ||

| High school and below | 26 | 28 | ||

| Junior college and above | 21 | 19 |

| Group | N | Markedly effective | Effective | Ineffective | Clinical efficiency (%) |

| Routine group | 47 | 11 | 17 | 19 | 59.6%(28/47) |

| care Bundles group | 47 | 16 | 22 | 9 | 80.9%(38/47) |

| x² | - | - | - | - | 5.087 |

| P | - | - | - | - | 0.024 |

| Group | n | Complete compliance | Good compliance | Poor compliance | Compliance (%) |

| Routine group | 47 | 13 | 17 | 17 | 63.8%(30/47) |

| Care bundles group | 47 | 22 | 23 | 2 | 95.7%(45/47) |

| x² | - | - | - | - | 14.842 |

| P | - | - | - | - | <0.001 |

| Group | n | IFABP (ng/ml) | DAO (mIU/ml) | Lactic acid (mmol/L) | |||

| Before care | After care | Before care | After care | Before care | After care | ||

| routine group | 47 | 64.28±10.31 | 56.45±10.12 | 9.24±1.35 | 7.25±1.26 | 1.86±0.45 | 1.68±0.33 |

| care bundles group | 47 | 64.33±10.45 | 45.63±9.71 | 9.18±1.41 | 5.44±0.71 | 1.91±0.39 | 1.41±0.31 |

| t | - | -0.023 | 5.289 | 0.211 | 8.58 | -0.576 | 4.088 |

| P | - | 0.982 | <0.001 | 0.833 | <0.001 | 0.566 | <0.001 |

| Group | n | Endotoxin (EU/ml) | Bowel dysfunction score | ||||

| Before care | After care | Before care | After care | ||||

| routine group | 47 | 0.78±0.14 | 0.72±0.13 | 10.42±2.23 | 6.39±1.84 | ||

| care bundles group | 47 | 0.80±0.15 | 0.61±0.09 | 10.39±2.27 | 4.26±1.31 | ||

| t | - | -0.668 | 4.769 | 0.065 | 6.465 | ||

| P | - | 0.506 | <0.001 | 0.948 | <0.001 | ||

| Routine group(n=47) | Care bundles group(n=47) | x² | P | |

| Multi-Organ Failure | 2 | 0 | - | - |

| Pulmonary edema | 1 | 0 | - | - |

| Dizziness and headache | 4 | 1 | - | - |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 | 1 | - | - |

| Total incidence (%) | 21.3%(10/47) | 4.3%(2/47) | 6.114 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).