1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis is one of the most frequent reasons for disability. Furthermore, the treatment of the aftermath requires significant financial resources. Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), next to total hip arthroplasty (THA), is one of the most often performed elective orthopedic surgeries. The main task is to reduce pain, restore knee function, and improve the quality of patient life. Although knee replacement is an effective treatment for severe joint damage, postoperative complications include blood loss, thrombosis, infection, and loosening or malalignment of the prosthetic component are known. Due to the blood loss related to TKA, which can range from 1500 to 2000 mL, the problem of perioperative bleeding has been debated for many years [

1].

Blood loss can be evaluated either by an estimation of the loss or by measurements of the drop of hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (HTC) as a surrogate for blood loss [

2,

3]. Different blood-sparing techniques in TKA have been studied, like the use of hypotensive anesthesia, perioperative blood salvage, perioperative blood donation, or recombinant human erythropoietin. Every 1000 mL of blood loss decreases the hemoglobin value by about 3g/dL [

4]. Significant blood loss increases the risk of blood transfusion and may result in prolonged patient stay and delayed rehabilitation. Postoperative allogeneic blood transfusion is a considerable risk of hemolytic and non-hemolytic reactions. Moreover, increase the costs related to knee replacement [

5,

6]. The impact caused by surgery enhanced by the tourniquet promotes the activation of the fibrinolytic system, and hyperfibrinolysis is considered the primary cause of postoperative bleeding after TKA surgery [

7]. Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a fibrinolysis inhibitor effecting by directly preventing plasminogen activation as well as inhibiting activated plasmin from degrading fibrin clots. TXA promotes hemostasis and can reduce the duration and quantity of blood loss [

8,

9]. It is worth highlighting that TXA has been included in the List of Essential Medicines of the World Health Organization (WHO) and is currently utilized in many different fields of medicine [

10]. Clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have confirmed that intravenous and topical TXA administration effectively reduces blood loss and transfusion risk. Intravenous administration of TXA is the most commonly used, but many studies have shown that topical use has similar safety and efficacy in TKA [

11,

12]. The analgesic effect associated with intraoperative topical use of TXA seems interesting, most likely associated with decreased postoperative inflammation and surgical site swelling [

11,

13]. Several perioperative TXA management protocols have been discussed, including a single dose and multiple administrations [

14,

15,

16]. Recently more studies have focused on the administration of oral TXA [

17,

18].

1.1. Local infiltration analgesia (LIA)

A technique including high-volume local infiltration analgesia (LIA) developed by Kerr and Kohan was dedicated to analgesia after TKA and THA [

19]. It initially assumed infiltration of ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline into the tissues around the surgical field supplemented with additional postoperative intra-articular injections. Despite limited data, using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in solution correspond with better managing postsurgical pain [

19]. Nowadays, LIA has been widely used for pain relief in patients undergoing total knee replacement for more than 15 years.

We aimed to investigate the efficacy of TXA supplemented with LIA in reducing blood loss in patients undergoing TKA.

2. Materials and methods

We have used the STROBE protocol designed for retrospective observational studies [

20].

Patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis who underwent unilateral primary cemented TKA at a ZSM Hospital in Chorzów between January 2018 and July 2022 were enrolled in the study. Following inclusion criteria were established for further evaluation to assess homogeneity between the groups: 1. patients with posterior-stabilized (PS) TKA exclusively because this procedure requires the release of the posterior joint capsule and is at risk of more significant intraoperative blood loss; 2. patients operated under spinal anesthesia (the vast majority of patients) as general anesthesia may result in increased blood loss; 3. patients operated on by one of the two surgeons (Ł.W; B.O). Patients with 1. pre-existing coagulopathy; 2. receiving long-term anticoagulant therapy before the surgery; 3. with other additional procedures, including implant removal; 4. with any complications requiring extended surgery, e.g., intraoperative femoral condyle fracture, were excluded from evaluation. After considering the above criteria, 530 individuals were included for further analysis. All data has been anonymized. The authors had no access to information that could identify individual participants. Patients were divided into three groups, corresponding to the method of bleeding control: I - patients without additional bleeding protocol (control group); II - patients with iV: 1,0 g of TXA administered 30 minutes before skin incision and 3 hours later (TXA group); III - patients with exact TXA protocol combined with intraoperative local infiltration analgesia (ropivacaine 200 mg and epinephrine 0.5 mg in 100 ml solution) (TXA + LIA group). Differences in the number of individuals between particular groups resulted from restrictions related to COVID-19 during the study period.

According to the Polish guidelines for preventing and treating venous thromboembolism, each patient received a dose of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) 12 hours before surgery (40 mg Clexane, Sanofi, Paris, France), and LMWH was continued postoperatively for 14 days. In order to assess blood loss, the hemoglobin (Hb-g/dl) level before the surgery was compared with the lowest hemoglobin level during the hospital stay. As a standard, laboratory tests were performed on the day of hospital admission, the second postoperative day, and the day preceding discharge. The rate of blood transfusions was assessed in each group. According to local hospital regulations, the hemoglobin cut-off level for transfusion was 8,5 g/dl. However, in patients with anemia-related symptoms, the transfusion trigger was less than 9,0 g/dl.

Follow-up for patients included was extended for one month after discharge to assess the early readmission rate.

2.1. Surgical technique

Operations were performed by two surgeons (Ł.W and B.O). A standard medial parapatellar approach completed through a straight midline incision of the quadriceps tendon was used in all cases. Surgical procedures were performed without a tourniquet, and thorough hemostasis was performed. The drain was used only in control group and was obligatorily removed 24 hours after the procedure, nonetheless of the drainage amount. When TXA was included in the perioperative protocol, drains were abandoned. After standard bone cuts, reasonable efforts have been taken to obtain a correct soft tissue balance to keep the joint aligned in flexion and extension. Cement-receiving bone surfaces were cleaned to remove fat residue, bone debris, marrow, and blood using a pulse lavage system. The LIA solution contained 200 mg of ropivacaine and 0.5 mg of epinephrine in a volume of 100 ml. The solution was sterile and prepared in two 50 ml syringes. The LIA was performed in two stages. The first administration (30 ml) concerned the posterior joint capsule directly after the osteophytes resection on the posterior aspect of femoral condyles, followed by releasing the tightened capsule. The midpoint of the posterior capsule was avoided due to the proximity of the neurovascular bundle. The second application concerned the remaining parts of the joint: medial collateral ligament (10 ml), lateral collateral ligament (10 ml), supracondylar soft tissue (20 ml), quadriceps tendon (10 ml), and subcutaneous tissue (20 ml).

Figure 1 shows the intraoperative administration of LIA.

For all patients, joint capsule was tightly sutured using STRATAFIX Symmetric PDS Plus 1-0 (ETHICON, Johnson & Johnson, Germany). After the surgery, a compression dressing on the operated limb was applied. On the first postoperative day, weight-bearing was allowed in line with a standard rehabilitation program.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. For the study ethical approval and participant consent was waived by the bioethics committee of Silesian Medical Chamber in Katowice, Poland (ŚIL.KB.1011.2022) due to the retrospective nature of the study.

All data were fully anonymized before analysis.

3. Results

According to inclusion and exclusion criteria, the patients were divided into groups corresponding to the protocol of blood loss reduction and the need for a blood transfusion. Group TXA + LIA was the most numerous, with 225 patients. Control group and TXA group were less considerable, with 164 and 141 patients. All groups were homogeneous in terms of gender, with a female predominance. The mean age for all patients was 71,44. Only the TXA group requiring blood transfusion differed from this value with the mean age of 75,93. The mean BMI value for all patients was 27,47. The mean hospitalization for patients from the control group was 7.02 (SD 1.34) days, 6.08 (SD 1.06) days for the TXA group, and 5.56 (SD 0.79) for the TXA + LIA group. The overview of the study group is presented in

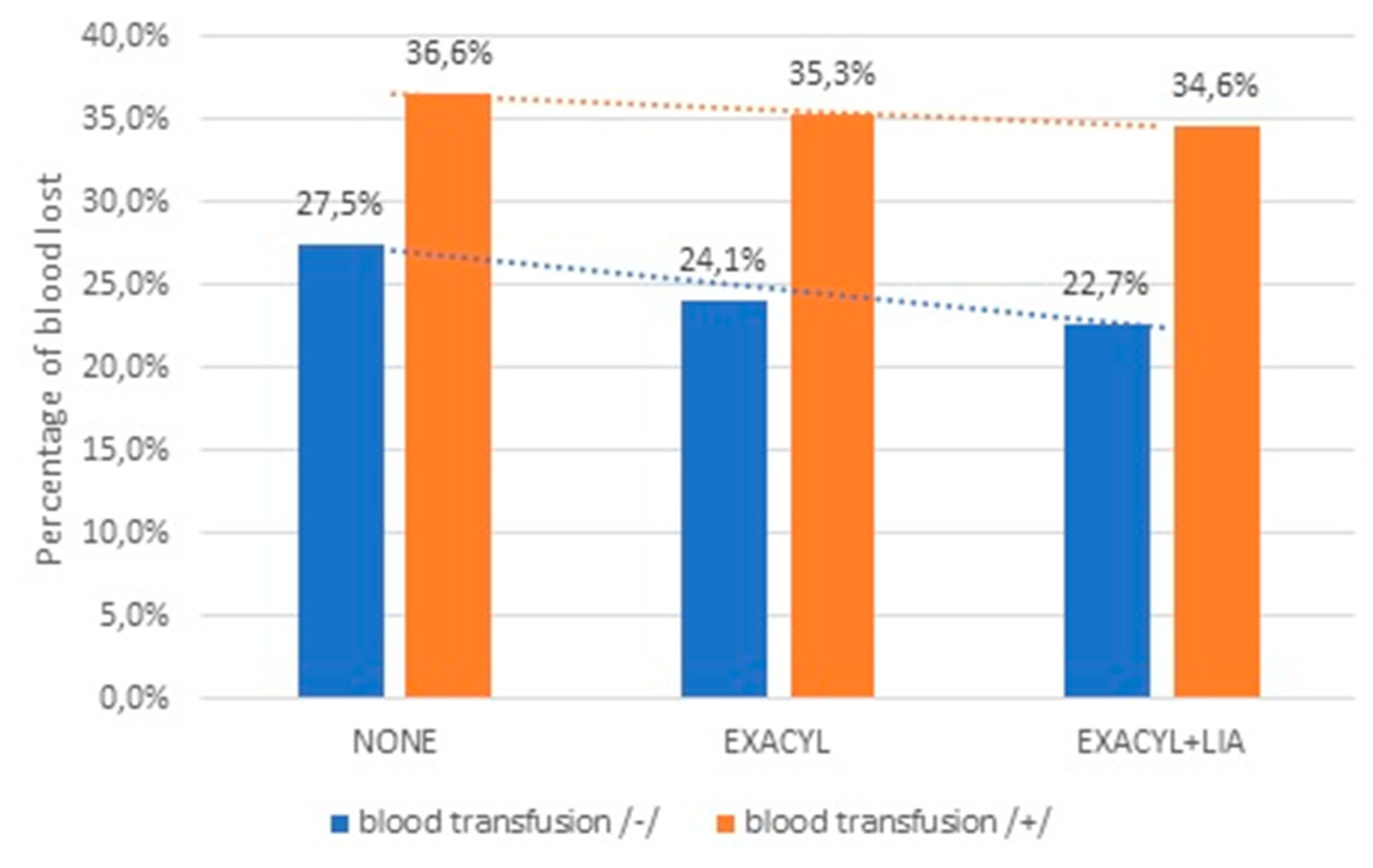

Table 1. The most significant reduction of hemoglobin value was found in the control group, which amounted to an average of 30.08% output value. In the TXA group, the decrease in hemoglobin was, on average, 25.17% (p<0.001), and in the TXA + LIA group, it was 23.67% (p<0.001). There is a statistically significant difference between the TXA and the TXA + LIA group for the mean difference at the 0.05 level (-.28757; p=0.02). Statistically significant (p<0.01) perioperative TXA administration reduced blood loss concerning pre-op hemoglobin value by 3.4% and TXA + LIA by 4.8% for patients not requiring a transfusion. Statistically significant (p<0.01) perioperative TXA administration reduced blood loss by 1.3% and TXA + LIA by 2% for patients requiring blood transfusion.

Figure 2. shows the percentage of blood loss concerning the initial hemoglobin value (separately for patients requiring blood transfusion and those who did not receive the blood). Based on the interdependence statistics (Chi-square test = 23.894; p<0.01), there is a statistically significant relationship between the decrease in the rate of allogeneic blood transfusions, which was 24.4% in the control group, 9.9% in the TXA group and 8% in TXA + LIA group.

3.1. Complications

In seven patients (5 in a control group and 2 in the TXA group), we observed persistent wound leaking lasting more than 72 hours, requiring prolonged hospitalization and handled by proper wound care. One patient from control group was readmitted with symptoms of wound infection four weeks after the initial surgery. The patient underwent the irrigation & debridement (I&D) procedure with the replacement of the polyethylene insert and retaining of the prosthesis. No pathogens were cultured from the intraoperatively collected materials. After I&D, recurrence of infection symptoms was no observed. We documented two cases of deep venous thrombosis among 530 patients (one case in a control group and one in TXA + LIA group).

3.2. Statistical analysis

The two-factor ANOVA test was used in the analysis of the test results. This analysis verified whether the study groups differed statistically significantly in blood loss. The work uses a multivariate analysis technique utilizing CHAID prediction trees with independent component analysis. BMI, age, and sex were assumed as independent secondary variables. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between independent secondary variables and blood loss. Then, Tukey's post-hoc test for unequal samples was used to analyze the detailed results. Before starting the analysis of differences, descriptive statistics were calculated (

Table 2).

The factorial Anova test (

Table 3) and Tukey's post-hoc test (

Table 4) for unequal samples were used to verify whether there were apparent differences between groups.

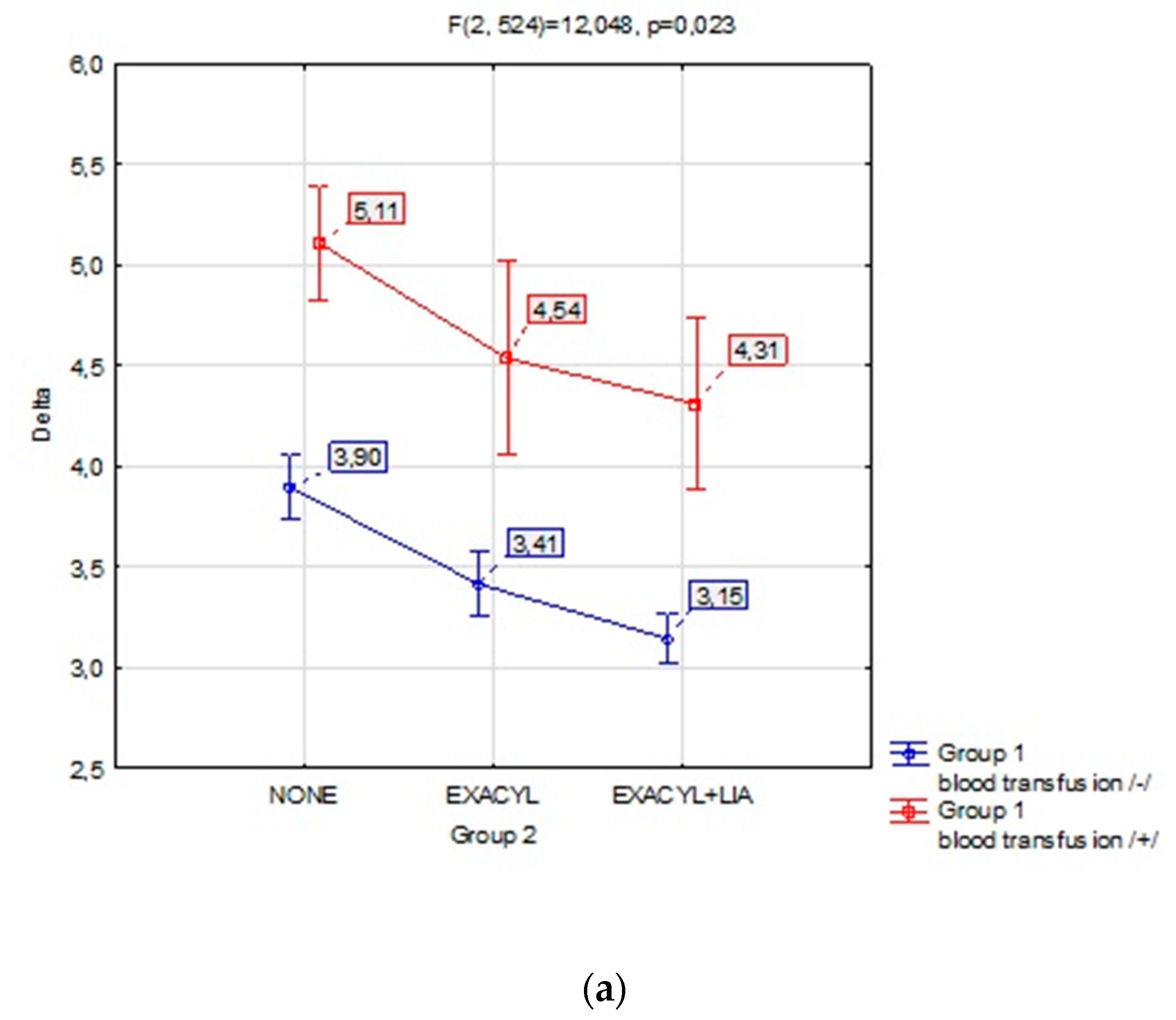

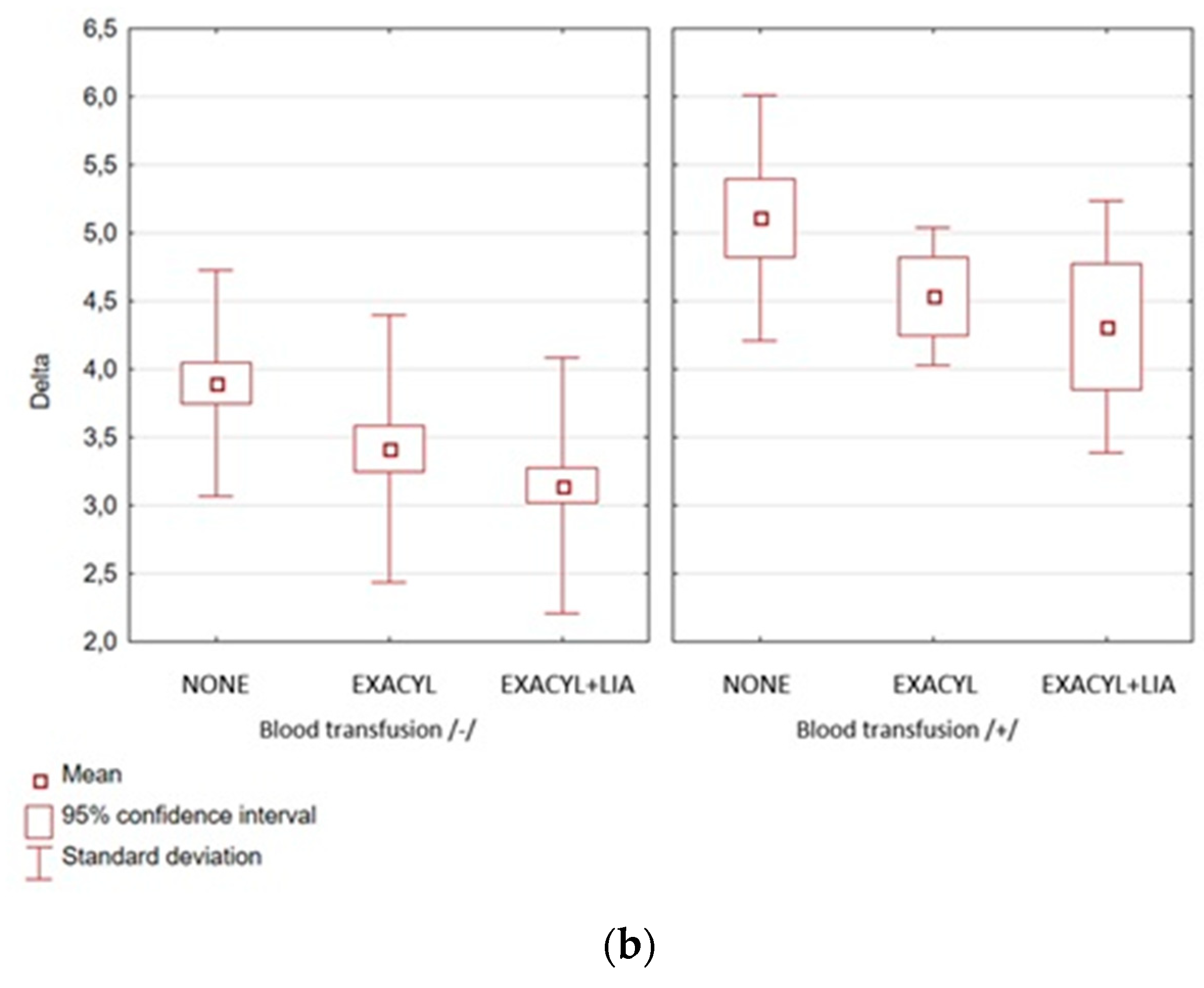

Figure 3a,b show the measured statistics. The 95% confidence interval for the mean indicates a range of results that will favor 95% of the tested people from a given group.

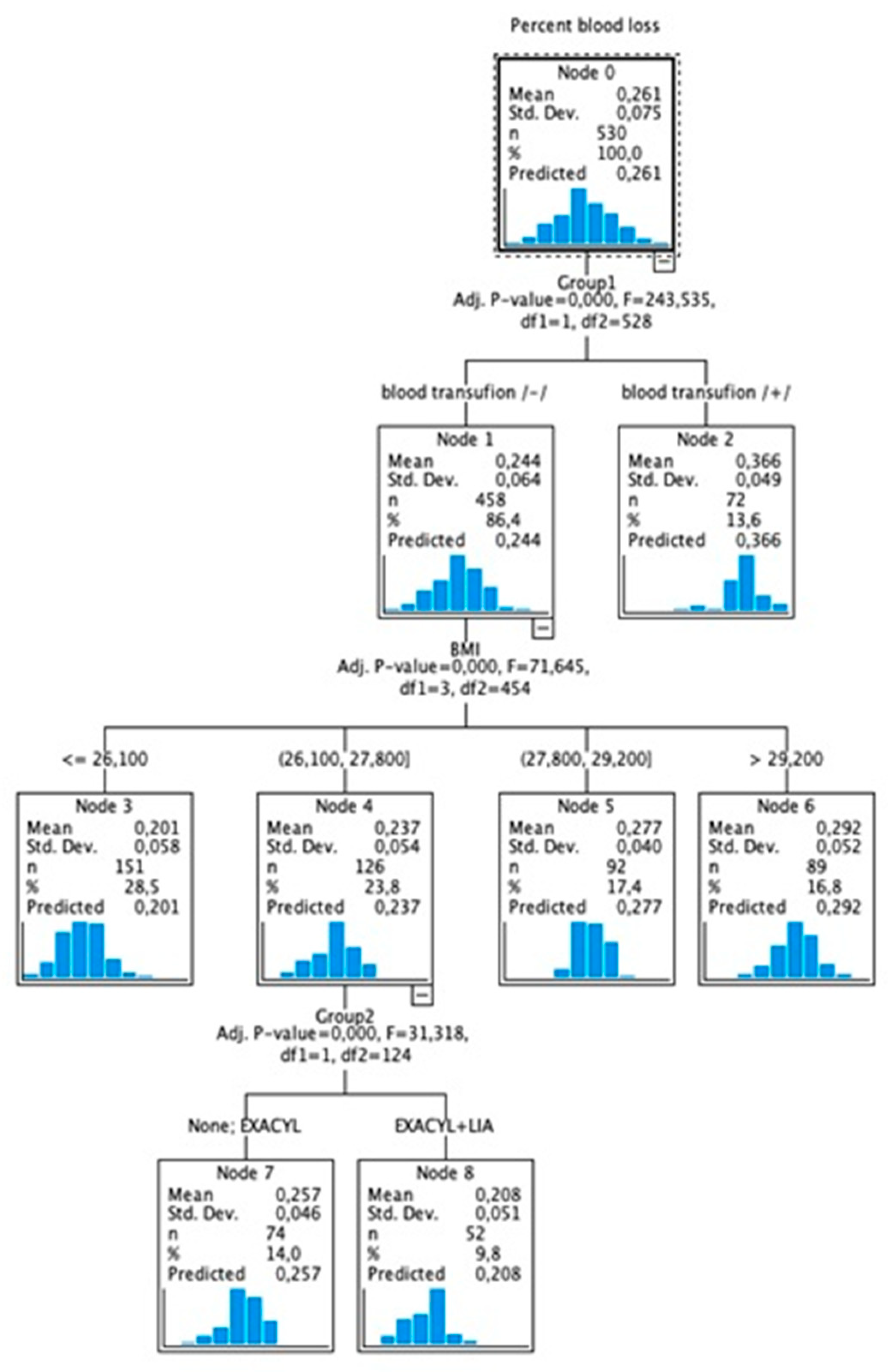

For none of the groups, gender and age were significantly related to perioperative blood loss. However, it was assessed that BMI is strongly related to blood loss. It can be concluded that the lower the BMI, the lower the blood loss after TXA administration (r=0.737; p<0.01). Blood loss is consistently lower for TXA + LIA (r=0.805; p<0.01).

Figure 4 shows a predictive model of the relationship between blood loss and BMI. The risk of blood loss for our study increased with higher BMI by: 20.1% for BMI<=26.1, 23.7% for BMI 26.1-27.8, 27.7% for BMI 27.8-29.2, and 29.2% for BMI>=29.2.

4. Discussion

Different studies have proved that using TXA in the perioperative protocol is a safe and effective method of reducing blood loss [

21,

22]. Numerous randomized controlled trials confirmed similar effectiveness of a dose of 1.0 g TXA with a dose calculated according to body weight of 20 mg/kg [

23]. Administering one dose of TXA and a scheme that assumes two or even more doses are known. Iwai et al. showed that double intravenous administration of TXA in the perioperative time resulted in a better reduction of blood loss than a single dose [

24]. Furthermore, many studies have revealed that topical use has comparable efficacy in TKA and avoids the prothrombotic effect of tranexamic acid [

11,

25,

26,

27]. The effectiveness of combining intravenous and topical TXA usage can be found in the literature. This protocol outcomes in lower average blood loss and a lower drop in hemoglobin levels compared to isolated intravenous administration [

28]. Marra F et al., in the prospective study, compared intravenous, intraarticular, and a combination of the two administrations of TXA and concluded that no protocol seems superior to the others in terms of blood loss and decrease in hemoglobin level [

29].

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTED) is a known complication of TKA. Although patients undergoing knee replacement routinely receive anticoagulant prophylaxis, VTED events still occur, with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). The prevalence of VTED is estimated at 0.8 to 1.8% of TKA patients [

30,

31]. In our study, we used a double dose of 1.0 g TXA administered 30 min before skin incision and 3 hours later. Like other authors, we did not notice an increased risk of VTED in our study group. We documented two cases of DVT and no PE among 530 patients (0.4%). One case of deep venous thrombosis was in a control group (66-year-old woman with BMI 29.7) and one in TXA + LIA group (75-year-old woman with BMI 29.8). Both patients had no additional risk factors for VTED, and both required blood transfusion due to a decrease in hemoglobin and systemic symptoms of anemia. The low level of thrombotic complications in our study should be explained by the fact that patients with pre-existing coagulopathy were excluded to ensure the homogeneity of the compared groups. The limitation of our study is the use of a drain in the control group. No drain was used in the TXA and TXA + LIA groups. Some studies have shown that using a drain in TKA increases blood loss [

32,

33], while others report that it does not influence perioperative blood loss [

34,

35,

36]. Although there is no agreement on using a drain and its impact on perioperative total blood loss, we believe this may cause a more significant difference between the study groups in our survey. Local infiltration analgesia is administered intraoperatively into the posterior capsule and soft tissues around the knee to reduce postoperative pain. There is heterogeneity in the studies of local analgesic drug combinations, infiltration sites, and volumes. Some LIA protocols rely on bupivacaine, others ropivacaine. The addition of steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been questioned because of the potentially increased risk of periprosthetic infection and renal as well as gut toxicity [

19,

37]. We have started using LIA routinely in TKA since January 2021 in close cooperation with anesthesiologists. Contrary to most recommendations, we used a volume of 100 ml because high LIA volumes may increase the risk of prolonged wound drainage or leaking [

19,

38].

Interestingly, our study showed no wound infection, delayed wound healing, or prolonged wound leaking in the TXA + LIA group. Patients in the LIA group had significantly lower pain scores according to Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), especially in the first two postoperative days compared with other patients. However, the detailed assessment was different from the purpose of this study. It is considered that LIA is a recommended analgesic option but cannot improve functional outcomes after TKA. Based on our results, the combination of TXA with LIA reduces perioperative blood loss. In our study, the decrease in hemoglobin value in the control group averaged 30.08%. In the TXA group was, on average, 25.17% (p<0.001), and in the TXA + LIA group, it was 23.67% (p<0.001). Moreover, reducing blood loss seems crucial to decrease the rate of allogeneic blood transfusions because they could increase the risk of surgical site infection and periprosthetic joint infection [

39]. For our patients, we noticed a statistically significant relationship (p<0.01) between the decrease in the allogeneic blood transfusions rate of 24.4% in the control group, 9.9% in the TXA, and 8% in the TXA + LIA group. Therefore, the combination of TXA with LIA might positively affect the final effect of TKA.

According to Başdelioğlu K, high BMI values adversely affect clinical and functional outcomes after TKA. Furthermore, obesity is one of the most critical risk factors for prosthesis infection and aseptic prosthesis loosening [

40]. Analyzing the results, we did not find any correlation between blood loss and the patient's sex or age. However, we found a strong relationship between blood loss and BMI. Our study's risk of blood loss increased with higher BMI by 20.1% for BMI<= 26.1 and 29.2% for BMI>=29.2.

Further analysis is needed to understand the impact of the combination of tranexamic acid with local infiltration analgesia to reduce perioperative blood loss and the rate of blood transfusions after total knee replacement.

4.1. Study limitations

The main limitations of our study comprise the retrospective design. Another limitation of our study is the use of a drain in the control group, where the drain was not used in the TXA and TXA + LIA groups, and the lack of measurement of the volume of intraoperatively lost blood.

5. Conclusions

Compared to the separate administration of tranexamic acid, the combination of perioperative administration with local infiltration analgesia statistically significantly reduces blood loss in patients after total knee replacement. The combination of TXA and LIA minimizes the rate of allogenic blood transfusion and shortens hospital stays.

Author Contributions

Ł.W. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Ł.W. collected data. Ł.W. B.O. and M.D. conducted the data analysis. Ł.W. prepared the final version of the manuscript. Ł.W. B.O. and M.D. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was not funded. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent to Publish

Not applicable.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. For the study ethical approval and participant consent was waived by the bioethics committee of Silesian Medical Chamber in Katowice, Poland (ŚIL.KB.1011.2022) due to the retrospective nature of the study. All data were fully anonymized before analysis.

Abbreviations

| TKA |

Total knee arthroplasty. |

| THA |

Total hip arthroplasty. |

| TXA |

Tranexamic acid. |

| LIA |

Local infiltration analgesia. |

| NSAIDs |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. |

| STROBE |

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. |

| LMWH |

Low Molecular Weight Heparin. |

| I&D |

Irrigation & debridement procedure. |

| VTED |

Venous thromboembolic disease. |

| DVT |

Deep venous thrombosis. |

| PE |

Pulmonary embolism. |

References

- Park, J.H.; Rasouli, M.R.; Mortazavi, S.M.; et al. Predictors of perioperative blood loss in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg AM 2013, 95, 1777–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, P.E.; Lavand'homme, P.; Yombi, J.C.; Thienpont, E. Lower blood loss after unicompartmental than total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015, 23, 3494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spahn, D.R. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Kapadia, B.H.; Issa, K.; et al. Postoperative blood loss prevention in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2013, 26, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvakas, E.C.; Blajchman, M.A. Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogeneic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention. Blood 2009, 113, 3406–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shander, A.; Hofmann, A.; Ozawa, S.; et al. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 2010, 50, 753–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.L.; Letson, H.L.; Morris, J.L.; McEwen, P.; Hazratwala, K.; Wilkinson, M.; Dobson, G.P. Tranexamic acid is associated with selective increase in inflammatory markers following total knee arthroplasty (TKA): a pilot study. J Orthop Surg Res 2018, 13, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengborn, L.; Blomback, M.; Berntorp, E. Tranexamic acid–an old drug still going strong and making a revival. Thromb Res 2015, 135, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, J.D. Antifibrinolytics in major orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad orthop surg 2010, 18, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Model List of Essential Medicines: 21st List 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Dang, S.; Duan, D.; Wei, L. Comparison of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018, 19, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shen, B.; Zeng, Y. Comparison of topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and prospective cohort trials. Knee 2014, 21, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laoruengthana, A.; Rattanaprichavej, P.; Rasamimongkol, S.; Galassi, M.; Weerakul, S.; Pongpirul, K. Intra-articular tranexamic acid mitigates blood loss and morphine use after total knee arthroplasty. A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 877–881. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, D.R.; Sierra, R.J. Efficacy of combined use of intraarticular and intravenous tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. Ann Transl Med 2015, 3 (Suppl 1), S39. [Google Scholar]

- Akgul, T.; Buget, M.; Salduz, A.; et al. Efficacy of preoperative admin- istration of single high dose intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective clinical study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2016, 50, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Xie, J.; Huang, Q.; Huang, W.; Pei, F. Additional benefits of multiple-dose tranexamic acid to anti-fibrinolysis and antiinflammation in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2020, 140, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; et al. Comparison of 3 routes of administration of tranexamic acid on primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. J Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 2738–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Q.J.; Ching, W.Y.; Wong, Y.C. Blood sparing efficacy of oral tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Relat Res 2017, 29, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, D.R.; Kohan, L. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008, 79, 174–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. ; STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourlier, H.; Reina, n.; Fennema, P. Single dose intravenous tranexamic acid as effective as continuous infusion in primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomised clinical trial. Arch orthop trauma surg 2015, 135, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, s.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Fu, Y.C.; et al. The efficacy of combined use of intraarticular and intravenous tranexamic acid on reducing blood loss and transfusion rate in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015, 30, 776–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B.R.; Haughom, B.D.; Belkin, M.n.; et al. Weighted versus uniform dose of tranexamic acid in patients undergoing pri- mary, elective knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2014, 29 (9 suppl), 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, T.; Tsuji, S.; Tomita, T.; et al. Repeat-dose intravenous tranexamic acid further decreases blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Int orthop 2013, 37, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.F.; Hou, W.L.; Chen, J.B.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid for total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Med sci Monit 2015, 21, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, F.; Karaoğlu, S.; Mermerkaya, M.U.; et al. Reducing blood loss in simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: combined intravenous-intra-articular tranexamic acid admin- istration. A prospective randomized controlled trial. Knee 2015, 22, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera, X.; Martínez-Zapata, M.J.; Hinarejos, P.; et al. Topical and intravenous tranexamic acid reduce blood loss compared to routine hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Arch orthop trauma surg 2015, 135, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, N.P.; nisthane, P.P.; Shah, N.A. Combined administration of systemic and topical tranexamic acid for total knee arthroplasty: can it be a better regimen and yet safe? A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2016, 31, 542–547. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, F.; Rosso, F.; Bruzzone, M.; Bonasia, D.E.; Dettoni, F.; Rossi, R. Use of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. Joints 2017, 4, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahi, A.; Chen, A.F.; Tan, T.L.; Maltenfort, M.G.; Kucukdurmaz, F.; Parvizi, J. The incidence and economic burden of in-hospital venous throm- boembolism in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Shen, B.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.K.; Kang, P.D.; Pei, F.X. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism of total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of evidences in ten years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015, 16, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerke-Kroll, B.T.; Sculco, P.K.; McLawhorn, A.S.; Christ, A.B.; Gladnick, B.P.; Mayman, D.J. The increased total cost associated with post-operative drains in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, D.; Luger, E.; Bickels, J.; Menachem, A.; Dekel, S. Efficacy of closed wound drainage after total joint arthroplasty. A prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty 1997, 12, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Penematsa, S.; Parekh, S. Are drains required fol- lowing a routine primary total joint arthroplasty? Int Orthop 2007, 31, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omonbude, D.; El Masry, M.A.; O’Connor, P.J.; Grainger, A.J.; Allgar, V.L.; Calder, S.J. Measurement of joint effusion and haematoma formation by ultrasound in assessing the effectiveness of drains after total knee replacement: a prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010, 92, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaram, R.O.; Parkinson, R.W. Closed suction drains do not increase the blood transfusion rates in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2007, 31, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.; Ramankutty, S.; Board, T.; et al. Does intraarticular steroid infiltration increase the rate of infection in subsequent total knee replacements. Knee 2009, 16, 262–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, C.; Zan, P.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Q.; Li, G. The Comparison of Local Infiltration Analgesia with Peripheral Nerve Block following Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA): A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. J Arthroplasty 2015, 30, 1664–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innerhofer, P.; Klingler, A.; Klimmer, C.; Fries, D.; Nussbaumer, W. Risk for postoperative infection after transfusion of white blood cell-filtered allogeneic or autologous blood components in orthopedic patients undergoing primary arthroplasty. Transfusion 2005, 45, 103–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başdelioğlu, K. Effects of body mass index on outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2021, 31, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).