1. Introduction

Digital transformation has affected our lives and consumption. Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) service technologies have grown rapidly in various industries, including real estate, fashion brands, retail, transportation, tourism, education, entertainment, museums, furnishing, jewelry, consumer-packaged goods, and beauty products. Technological advance drives the VR development of computing, motion sensors, digital displays, and computer vision.

Augmented reality (AR) integrates virtual content into reality. The AR has been attracting increasing attention from marketing researchers. A VR creates a perception of virtual information, whereas AR enhances the real world for generating information [

1,

2]. The AR is defined as a feature of the interactive, real-time, computer-generated, and simultaneous application [

3,

4,

5] enabling consumers to see the real world and its virtual objects by wearing see-through displays[

6]. An AR is a 3-D computer-simulated visualization technology supplementing sensory information, including graphics, labels, objects, sounds, and avatars[

7,

8,

9].

An AR delivers an interactive experience and enhances contextual information for appearance, enjoyment, and usability [

6,

10] Marketing platforms evolve rapidly in AR and enable real-time interactions to enhance customer experiences [

7,

11]. For example, advancing new technologies, such as Apple AR and 5G glasses, enhances marketers’ ability by employing AR in various industry contexts. [

12,

13,

14] With the increasing number of companies integrating AR into their marketing plans, AR marketing applications have become other forms of digital marketing strategies [

15,

16,

17]. AR in marketing applications provides consumer experiences and demonstrates consumer benefits by integrating digital information and the physical environment [

18].

A VR refers to a computer-generated simulation that incorporates vision, hearing, or touch and interacts to be real and is a vehicle with other hardware for simulation [

19,

20]. Firms use VR marketing tools, including branded VR, to promote their businesses [

3,

16,

21]. Virtual Reality marketing is an effective strategy [

22] and an ideal marketing platform for enhancing consumer experiences [

23,

24,

25]. Retailers use VR for service innovation to create new business opportunities and promote economic growth[

26,

27].

The research scope focuses on fashion brands using VR or AR service technology applications to improve the shopping experiences. With advances in VR and/or AR service technologies, many fashion brands use VR and/or AR service technologies to enhance services for enhanced consumer experience.

The fashion brand industry

increasingly uses VR or AR technologies

to conduct customer service businesses. Firms such as Amazon, ASOS, Nike, and IKEA implement VR and AR service technologies to enhance the consumption experience of their products and help consumers make purchase decisions [

15,

28]. Consumers often use computer-generated product representations to develop innovative products before making purchasing decisions [

20,

28]. [

22]s’ research find that VR and AR service technologies produce better effects on consumer behaviors than traditional businesses. [

5,

29,

30] examined the effect of VR and AR service technologies in some previous studies. However, limited studies exist that examine AR and VR service technologies for consumer distractive and negative effects on consumer responses [

31,

32,

33]. Few studies have focused on AR and VR service technologies to examine consumers’ psychological mechanisms. Despite the steady growth in VR and AR service technology applications, the literature still lacks empirical research explaining consumers’ psychological factors and perspectives. Therefore, this study addresses how VR and AR service technologies reshape our understanding and conceptualization of consumer purchase intention in the fashion brand context.

This research theme has received little attention in marketing and information management journals. A literature review reveals that studies on VR and AR service technologies for fashion brands are scarce. This study attempts to explain consumer purchase decisions regarding fashion brands using VR and AR service technologies. It employs self-determination theory (SDT) to examine empirical evidence of antecedent variables and purchase intention for fashion brands in the context of VR and AR service technologies. This research aims to understand the factors that facilitate the adoption of VR and AR service technologies by incorporating the SDT.

This study contributes to research on VR and AR service technologies in two ways. First, by examining how VR and AR attributes influence consumer perceptions of fashion brands with their service technologies, fashion brand retailers can improve their VR and AR service technologies. Second, a more thorough conceptualization of consumer purchase intention perception of fashion brands with VR and AR service technologies could help fashion brand retailers learn how to attract consumers to their fashion brands when designing VR and AR service infrastructures. Third, the results contribute knowledge to information management journals. This study seeks to answer three important questions: (1) How do VR and AR service technologies re-evaluate the understanding and conceptualization of consumer purchase intention in the fashion brand context? (2) How do the antecedents of VR and AR service technologies affect consumer experience in the fashion brand context?(3) What are consumers’ cognitive responses to VR or AR service technologies in the fashion brand context?

The research motivation is to study the unique experiential and psychological aspects of VR and AR in fashion brands. However, information management literature lacks an understanding of the role of psychological and experiential factors in examining the antecedents of consumer purchase intention. This research aims to address this gap and add to our theoretical knowledge of VR and AR service innovation technologies by exploring the antecedent variables influencing purchase intention. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to develop a theoretical model with key variables influencing purchase intentions for fashion retailers' VR and AR service technologies based on SDT. The findings have significant managerial implications for firms with VR and AR service technologies for better service innovation performance and purchase intentions of potential customers. Little research has contributed to the theoretical and managerial implications of improving VR and AR service technologies in the fashion brand industry. Further, most studies have focused on VR and AR technical issues, ignoring customer perspectives.

This study highlights a theoretical model for VR/AR service technologies. This research contributes to the literature by advancing the knowledge of consumer experience and purchase decisions based on the SDT. Furthermore, the SDT provides a useful foundation for investigating consumer behavioral intentions and important practical insights for enhancing fashion brand practices. The research outcomes will provide a foundation for firms to invest in and design VR and AR service technologies and examine their context of fashion brands for further studies. A comprehensive determinant of purchase intentions toward fashion brands would enable managers to formulate effective marketing strategies in the digital marketing era.

5. Discussion

Advances in AR/VR marketing applications have attracted considerable interest. The AR is increasingly deployed in retail settings.

This research finding provides empirical support for the SDT

as a guiding framework for understanding how to influence purchase intention in the fashion brand context, focusing on the purchase intention effect after an AR/VR usage application. This result is consistent with previous studies that found AR/VR marketing is a driving strategy for improving and increasing consumer purchase intentions [

14,

18,

112,

113]. [

77] and [

87] recognized the psychological and cognitive factors influencing consumers’ acceptance and adoption of innovative marketing technologies and supported the purchase decision from the AR and VR service technologies application.

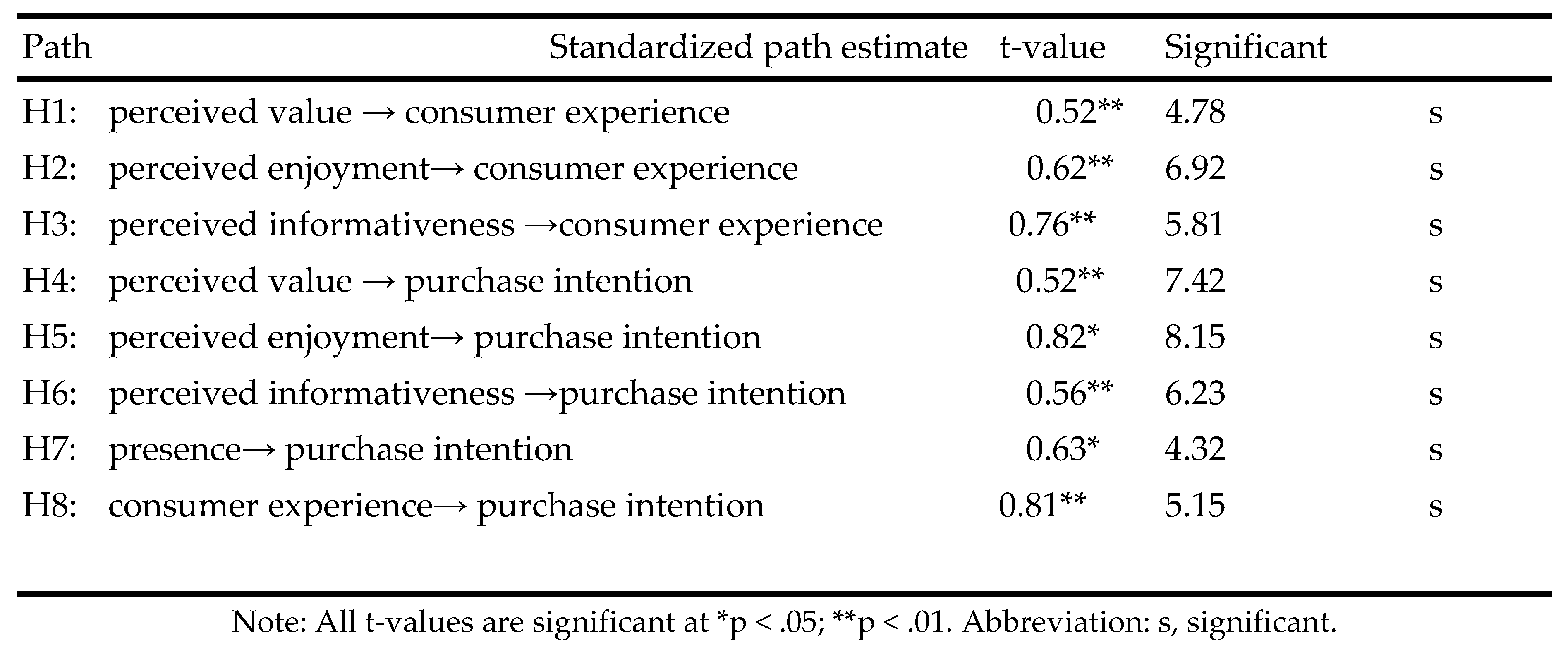

In addition, this study highlights the roles of consumers’ perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and experience

as important determinants of purchase intentions. The research findings reveal that fashion product purchase intentions are influenced by multiple factors.

The results show that AR and VR service technologies consumer experience positively impacts consumer purchase intentions, such as increased curiosity, interest, inspiration, enthusiasm, surprise, expectation, and satisfaction. Previous researches emphasize the importance of AR/VR service technologies for enhancing the consumer experience for better organizational performance [

16,

96]. Therefore, the empirical research incorporates some research constructs related to the SDT to develop a research model to examine how AR and VR service technologies influence consumers’ psychological responses to interact with the product and make purchase decisions.

Although AR/VR service technologies are relatively new in Taiwan, the research results suggest that these systems attempt to influence consumers’ attitudes toward value, enjoyment, and informativeness. Taiwanese consumers appreciate innovative service technologies, and the data analysis demonstrates their comfort in using the new technology when perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, and consumer experience influence their purchase intention. In particular, this study finds that value, enjoyment, and informativeness are antecedents of consumer experience, which, in turn, affect purchase intention. The results show fashion brand retailers in Taiwan with AR/VR applications supporting physical and online shopping influence consumer buying decisions. Taiwanese fashion brand retailers have developed and adopted a new AR/VR application technology that positively influences consumer purchase intentions and decisions. The study of fashion brand retailers considers consumer interactions with AR/VR applications as a shopping experience by focusing on perceived value, enjoyment, and informativeness as the most important elements of the AR/VR application.

Considering it is essential to examine consumers’ perceptions of VR/AR service technology applications, this study investigated the influence of AR/VR service technology usage on fashion brand consumers. It focuses on consumer experience and purchase intention of AR/VR service technologies. The conceptual model examines the research constructs for psychological characteristics (perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience) rather than the technology acceptance model (TAM), including ease of use, usefulness, attitude, and behavioral intention research constructs and variables. In summary, fashion brand retailers should introduce AR/VR systems to support the consumer experience and enhance purchase intention. Therefore, fashion brand retailers should develop interactive AR/VR service systems as a new marketing strategy.

Perceived value, enjoyment, and informativeness positively affect consumer experience. Consumer experience can enhance consumer value, enjoyment, and informativeness. Consumer experience can facilitate comparing products using AR/VR service technology applications. Therefore, service providers should also suggest customized schemes based on customer needs and highlight the importance of marketing plans for AR/VR service technology applications.

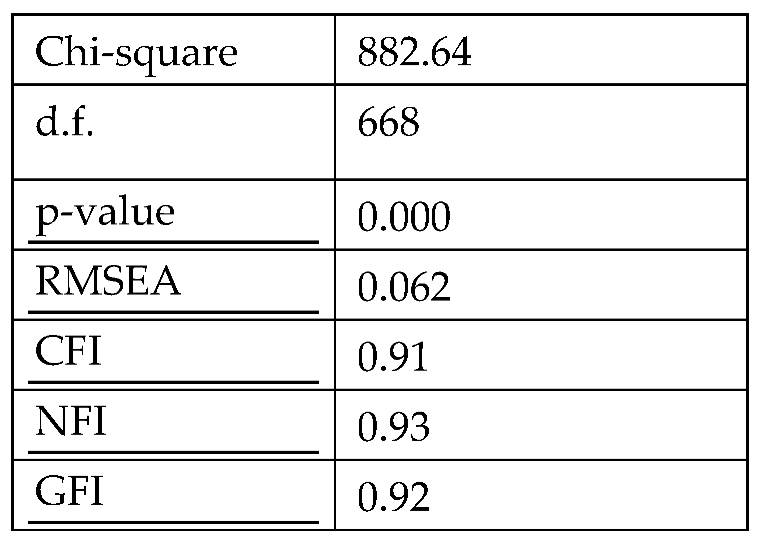

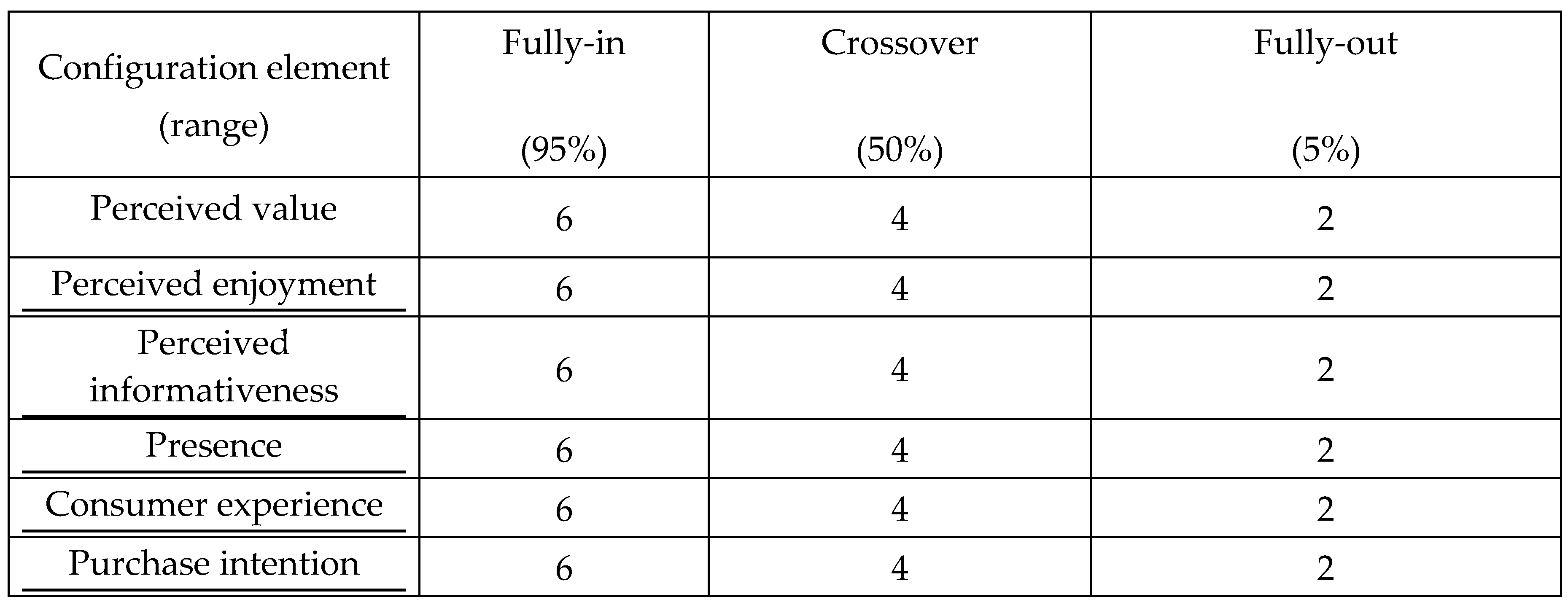

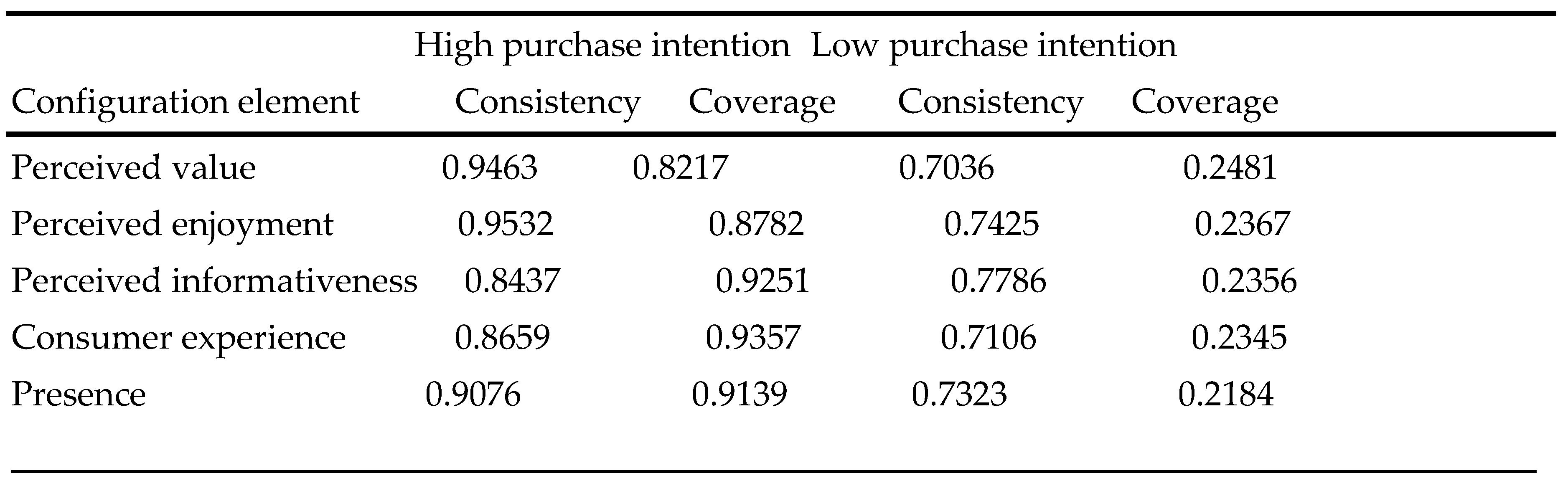

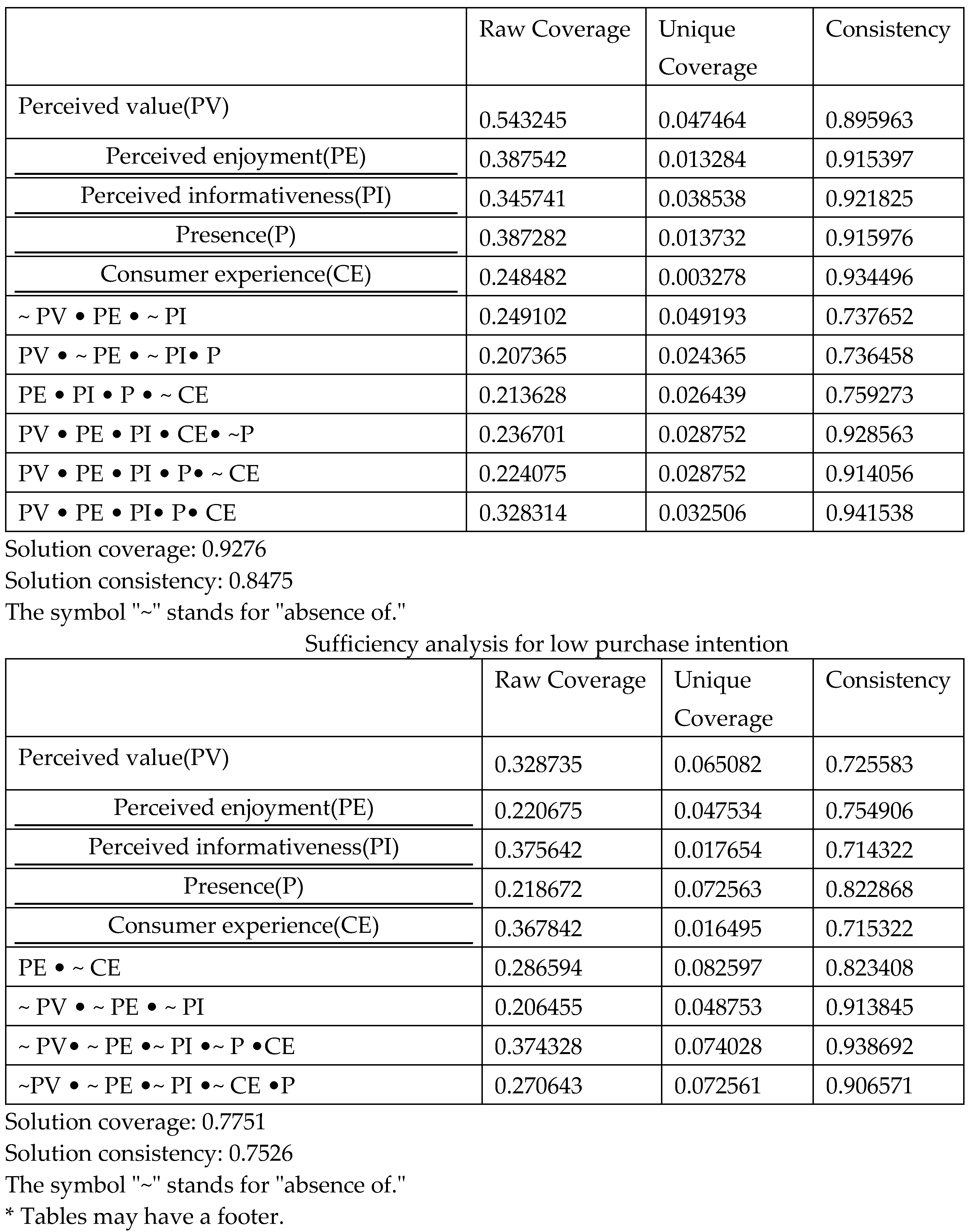

This study combined SEM and fsQCA to examine the proposed research hypotheses. The SEM and fsQCA enrich the understanding of how perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience explain a consumer's purchase intention. The SEM analysis indicates that perceived value, perceived enjoyment and perceived informativeness, presence, and consumer experience positively affect purchase intention, while the fsQCA findings show that these cognitive factors should always be combined with purchase intention. The results show that perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience are not individually relevant and must be combined to predict purchase intentions.

This study also provides insights when employing SEM, and the fsQCA complement and contributes to the existing literature. The SEM and fsQCA methods examine the antecedents of purchase intention through a symmetric theory approach [

33,

81]. The fsQCA provides important and detailed information about higher or lower purchase intention segments for necessary and sufficient conditions. Decision-makers can understand the differences in purchase intention among different consumer segments. The FsQCA operationalization of the SDT model with an adjective semantic differential segmented group offers a better cause analysis of AR/VR service technology applications supporting the validity of the basic SDT model. Hence, SEM combined with the fsQCA model is preferred over the single model. Empirically, this study combines the SEM and fsQCA models for better predictive accuracy[

81].

This study examines consumer differences and similarities across segments based on their psychological responses towards AR/VR service technologies application in fashion brand retail using fsQCA. The purchase intention heterogeneity was examined by employing fsQCA. It was found that consumer heterogeneity exists in consumers’ psychological perceptions of AR/VR service technologies. This study identifies the commonalities and differences between low and high purchase intention segments by employing fsQCA to predict consumers’ purchase intentions and examines the combined conditions of perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience. Consumers with high purchase intentions have a greater positive response towards AR/VR service technologies and higher perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, and presence. Perceived value, perceived enjoyment, perceived informativeness, presence, and consumer experience are necessary to enhance consumers’ purchase intentions from the fsQCA. Accordingly, the research findings indicate that perceived value, perceived enjoyment and informativeness, presence, and consumer experience are necessary and sufficient conditions to enhance consumers’ purchase intentions. These findings support SDT and reveal that a consumer’s perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and experience are necessary and sufficient to predict purchase intention. Consistent with the fsQCA results, firms should focus on understanding consumer attitudes and intentions toward AR/VR marketing. Future AR/VR marketing consumer research should examine consumers’ perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience as psychographic variables to enhance purchase intention for AR and VR service technology applications.

From a theoretical perspective, the results shed light on the affective factors influencing purchase intention in marketing and information management literature. This study extends the previous research explaining how consumers perceive VR and AR in fashion brands. Despite the application of ARVR service technologies by retailers worldwide, previous studies show that consumer attitudes towards AR/VR service technologies as management and marketing strategies are not always positive [

13,

87]. However, the research findings indicate that AR/VR service technologies applied to marketing strategies can have positive motivations and attitudes towards consumers’ experiences.

This research identifies relevant variables and adopts them from the AR/VR domain to further understand consumers’ purchase intentions in the fashion brand market. Among the research constructs, perceived value and enjoyment, perceived informativeness, presence, and consumer experience influence were tested as determinants of purchase intention toward fashion brands. Contrastingly, perceived value and enjoyment and perceived informativeness are examined as determinants of enhancing the consumer experience in the fashion brand context. The research findings regarding the significant factors are suggested for future research on purchase intentions toward fashion brands.

This study demonstrates that perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience positively affect purchase intention. This strengthens the SDT, arguing their satisfaction with psychological characteristics in the virtual environment and how to facilitate purchase intention. The research results are consistent with other studies in the literature, which show that consumers’ attitudes could determine their purchase intention [

69,

93,

104]. The AR/VR service technologies for marketing applications can be coordinated to develop and implement successful marketing programs [

17,

101]. These results shed new light on previous studies by [

18,

114], showing that consumers’ psychological factors can influence their purchase intention to stimulate retail AR/VR service technology development. The research found that psychographic factors influence the technological adoption of AR/VR services.

Regarding practical implications, this study considers AR/VR service technologies as a marketing strategy and offers important practical implications for fashion brand retailers. The research segments high and low purchase intention consumer groups to identify the heterogeneity of consumer attitudes toward AR/VR service technologies. The results show that consumers react differently to AR/VR service technologies applications, from low to high purchase intention. Fashion brand retailers can leverage critical resources to communicate the value of AR/VR service technologies and assist consumers. They should ensure that AR/VR service technology is high value, enjoyable, informative, and has a good presence and consumer experience to increase consumers’ purchase intention. These practical implications are important for future AR/VR service technology applications in the fashion brand context.

The results revealed the relative importance of all significant factors identified through research hypothesis testing by employing SEM and FsQCA. Among the significant determinants of the purchase intention of fashion brands, attitude investigation is important for strategic decisions regarding the perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience. Accordingly, consumer experience is the most critical factor for fashion brands, affected by perceived value, enjoyment, and informativeness. Therefore, fashion brand service providers should consider the important psychological factors of these research results.

This study has practical implications for retailers and marketers to invest in AR/VR service technologies. Since AR/VR service technologies specifically lead to beneficial effects, it is recommended that investors invest in AR/VR service technologies applications to enhance consumer experience and purchase intention. This study demonstrates the positive effects of informativeness as a marketing strategy. The high purchase intention segment significantly and positively affects psychological attitudes toward AR/VR service innovation applications. Hence, fashion brand retailers have opportunities to promote the benefits of AR/VR service technologies to consumers. Purchase intention can be enhanced through consumer perceptions of value, enjoyment, informativeness, and presence in AR/VR service technologies. Consumers have a better experience of their purchase intentions. This research finding supports fashion retailers’ development of necessary AR/VR service technology applications.

The sample data for this research were collected between April and June 2022 in Taiwan. During this period, the COVID-19 pandemic strongly affected the global economy [

115,

116]. This study demonstrates that consumers’ purchase intentions can be enhanced through perceived value and enjoyment, perceived informativeness, presence, and consumer experience in fashion brands during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research also guides decision-makers to invest in AR/VR service technologies to improve consumers’ purchase intentions. The research findings motivate marketing managers and/or CEO to invest in AR/VR service technologies during and after COVID-19. The results also help us understand that consumers can use AR/VR service technologies and applications for their shopping experience. Consumers can gather information about products from AR/VR service technologies applications, which can be used to strengthen their purchase intentions.

6. Conclusions

The research objectives shed light on AR/VR marketing issues, on which little research exists for AR/VR service technologies application in the information management literature. Therefore, this study obtains findings that answer three key questions: How do the antecedents of VR or AR service technology applications affect consumer experience in the fashion brand context? What are consumers’ purchase intentions using VR or AR service technologies in the fashion brand context? Which factors influence the results of consumers’ purchase intentions for the AR/VR service technologies application in the marketing plan? The research findings show that perceived value, enjoyment, informativeness, presence, and consumer experience positively affect purchase intentions when using AR/VR service technologies. Finally, the results highlight that perceived value, enjoyment, and informativeness affect the consumer experience. Regarding the impact of the AR/VR consumer experience, the results show that AR/VR consumer experience positively impacts consumers’ purchase intention in terms of increased curiosity, interest, inspiration, enthusiasm, amazement, expectation, and satisfaction.

This study had some limitations. First, only fashion brands in Taiwan are examined, limiting industry-wide generalizability because customers may have varying attitudes toward the AR/VR shopping experience. Accordingly, future research should extend to another industry or national context to provide additional perspectives. Second, the research investigates Taiwanese fashion brand consumer samples, mainly focusing on a certain age range (between 16 and 35 years). This range of young respondents answered the questionnaire because of the extensive use of AR/VR service technologies applications; however, this might limit the research performance to a general public sample. Empirical evidence from older consumers with higher incomes should be used in future studies. Third, the sample in this study was sufficiently large for SEM and fsQCA to obtain valid empirical results. However, future research should obtain a larger sample set and collect more data to increase predictive validity. Given the vast diversity of this fashion brand market, future studies should focus on the effect across countries from different consumer cohorts to explore the different segments of AR/VR service technologies applications. Fourth, the research model developed only six research constructs; therefore, this study did not include the impact of other important factors, such as loyalty and technological characteristics. These variables should be considered in future studies. Future studies should examine other research constructs and variables to evaluate indicators impacting consumer purchase intention. Finally, another research limitation of the survey is that the questionnaire is a self-reported measure of consumers’ responses owing to constraints of the survey's administration to respondents from an online survey. Future research could collect open and secondary data sources to obtain the views of AR/VR service technologies consumers.