Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Synthesis and modification of MNPs

2.1. Synthesis

2.1.1. Co-precipitation

2.1.2. Solvothermal synthesis

2.1.3. Thermal decomposition

2.1.4. Microemulsion method

2.1.5. Green synthesis.

2.2. Surface modifications

2.2.1. Organic coatings/ligands

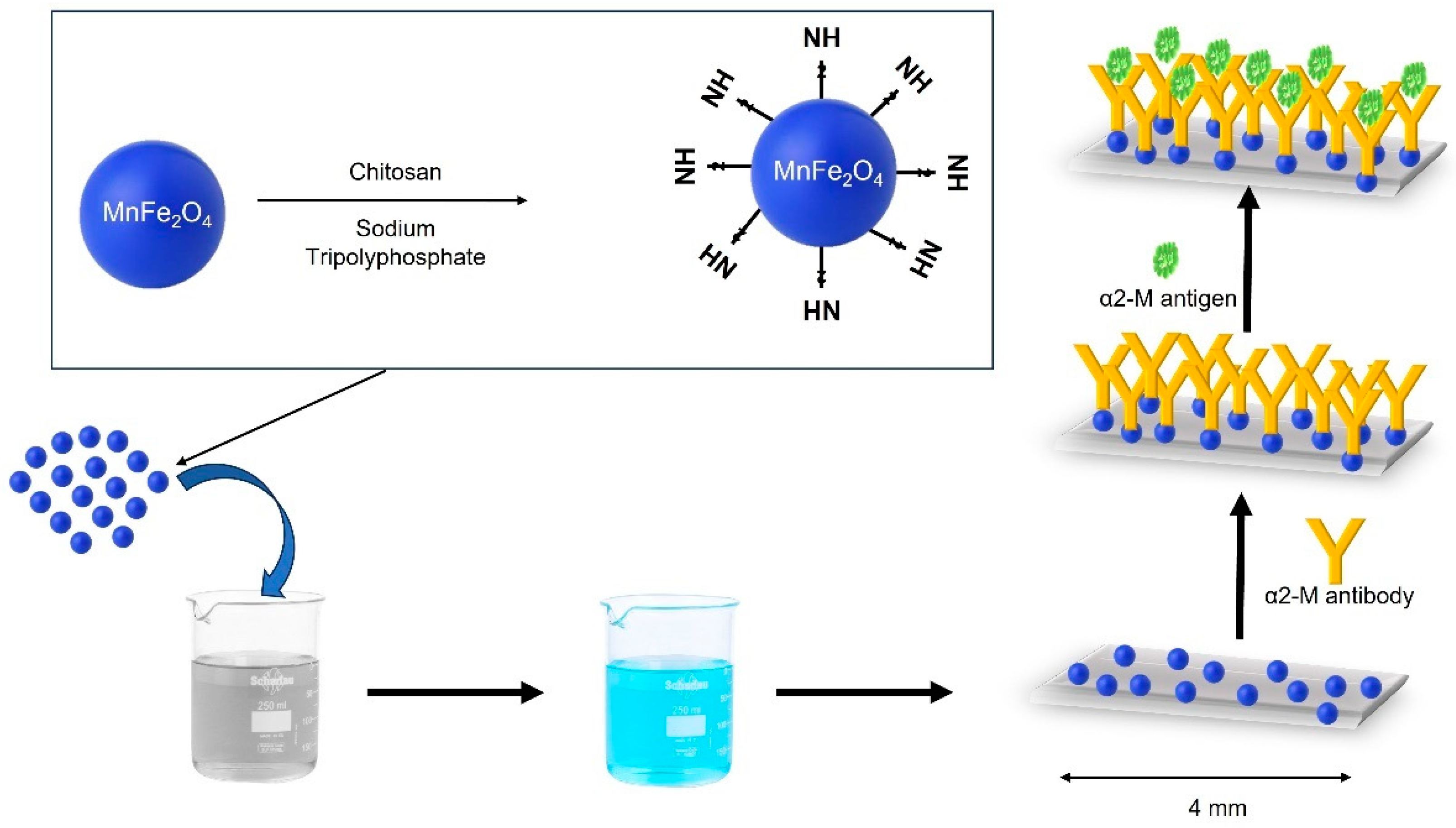

2.2.1.1. Chitosan

2.2.1.2. Poly (ethylene glycol)

2.2.1.3. Polypyrrole (PPy)

2.2.1.4. Polyaniline (PANI)

2.2.1.5. Polydopamine (pDA)

2.2.3. Inorganic coatings and modifications

2.2.3.1. Silica

2.2.3.2. Gold (Au)

2.2.3.3. Platinum (Pt)

2.2.3.4. Quantum dots (QDs)

3. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Prabowo, B.A., et al. The Challenges of Developing Biosensors for Clinical Assessment: A Review. Chemosensors, 2021. 9. [CrossRef]

- Bhavadharini, B., et al., Recent Advances in Biosensors for Detection of Chemical Contaminants in Food — a Review. Food Analytical Methods, 2022. 15(6): p. 1545-1564. [CrossRef]

- Aquino, A. and C.A. Conte-Junior A Systematic Review of Food Allergy: Nanobiosensor and Food Allergen Detection. Biosensors, 2020. 10. [CrossRef]

- Péter, B., et al. Review of Label-Free Monitoring of Bacteria: From Challenging Practical Applications to Basic Research Perspectives. Biosensors, 2022. 12. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, B., H. Dellweg, and L.M. Gierasch, Glossary for chemists of terms used in biotechnology (IUPAC Recommendations 1992). 1992. 64(1): p. 143-168. [CrossRef]

- biosensor. 2014.

- Sumitha, M.S. and T.S. Xavier, Recent advances in electrochemical biosensors – A brief review. Hybrid Advances, 2023. 2: p. 100023. [CrossRef]

- Ronkainen, N.J., H.B. Halsall, and W.R. Heineman, Electrochemical biosensors. Chem Soc Rev, 2010. 39(5): p. 1747-63.

- Biswas, G.C., et al. A Review on Potential Electrochemical Point-of-Care Tests Targeting Pandemic Infectious Disease Detection: COVID-19 as a Reference. Chemosensors, 2022. 10,. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.B., N.H. Ayachit, and T.M. Aminabhavi Recent Advances in Microfluidics-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Foodborne Pathogen Detection. Biosensors, 2023. 13. [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H., et al. Comprehensive Review on Wearable Sweat-Glucose Sensors for Continuous Glucose Monitoring. Sensors, 2022. 22,. [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J., et al., Advances in Biosensor Technologies for Infection Diagnostics. Accounts of Chemical Research, 2022. 55(2): p. 121-122. [CrossRef]

- Martín, M.-S., et al., First bioelectronic immunoplatform for quantitative secretomic analysis of total and metastasis-driven glycosylated haptoglobin. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry, 2023. 415(11): p. 2045-2057. [CrossRef]

- Brady, N., et al., An immunoturbidimetric assay for bovine haptoglobin. Comparative Clinical Pathology, 2019. 28: p. 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Lou, D., et al., Advances in nanoparticle-based lateral flow immunoassay for point-of-care testing. View, 2022. 3(1): p. 20200125.

- Jin, Y., et al., Multifunctional nanoparticles as coupled contrast agents. Nat Commun, 2010. 1: p. 41. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.P., et al., Biomedical applications of nanotechnology. Biophys Rev, 2017. 9(2): p. 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Pascual, A.M. and A. Rahdar, Functional Nanomaterials in Biomedicine: Current Uses and Potential Applications. ChemMedChem, 2022. 17(16): p. e202200142. [CrossRef]

- Baig, N., I. Kammakakam, and W. Falath, Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Materials Advances, 2021. 2(6): p. 1821-1871. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z., et al., Recent Advances in Magnetic Nanoparticles-Assisted Microfluidic Bioanalysis. Chemosensors, 2023. 11(3): p. 173. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I., K. Saeed, and I. Khan, Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arabian Journal of Chemistry, 2019. 12(7): p. 908-931.

- Scigalski, P. and P. Kosobucki, Recent Materials Developed for Dispersive Solid Phase Extraction. Molecules, 2020. 25(21). https://doi:10.3390/molecules25214869. [CrossRef]

- Predoi, D., et al., Biocompatible Layers Obtained from Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in Suspension. Coatings, 2019. 9(12): p. 773. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S., et al., Cutting-Edge Advances in Electrochemical Affinity Biosensing at Different Molecular Level of Emerging Food Allergens and Adulterants. Biosensors (Basel), 2020. 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A., et al., Recent Advances of Magnetic Nanomaterials for Bioimaging, Drug Delivery, and Cell Therapy. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 2022. 5(8): p. 10118-10136. [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, M., et al., Nanomaterials for diagnosis and treatment of brain cancer: Recent updates. Chemosensors, 2020. 8(4): p. 117. https://doi:10.3390/chemosensors8040117. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K., et al., Magnetosome-inspired synthesis of soft ferrimagnetic nanoparticles for magnetic tumor targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2022. 119(45): p. e2211228119. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., et al., Review on Recent Progress in Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Diverse Applications. Front Chem, 2021. 9: p. 629054. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I., et al., Electrochemical bioassay based on l-lysine-modified magnetic nanoparticles for Escherichia coli detection: Descriptive results and comparison with other commercial magnetic beads. Food Control, 2023. 145: p. 109492. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S., et al., Beyond Sensitive and Selective Electrochemical Biosensors: Towards Continuous, Real-Time, Antibiofouling and Calibration-Free Devices. Sensors (Basel), 2020. 20(12). [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S., et al., Electrochemical biosensors for autoantibodies in autoimmune and cancer diseases. Analytical Methods, 2019. 11(7): p. 871-887. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A., M.J. Nine, and F.S. Silva, Biosensing platform on ferrite magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, functionalization, mechanism and applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci, 2021. 290: p. 102380. [CrossRef]

- Schladt, T.D., et al., Synthesis and bio-functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles for medical diagnosis and treatment. Dalton Trans, 2011. 40(24): p. 6315-43. [CrossRef]

- Abid, N., et al., Synthesis of nanomaterials using various top-down and bottom-up approaches, influencing factors, advantages, and disadvantages: A review. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, 2022. 300: p. 102597. [CrossRef]

- Alromi, D.A., S.Y. Madani, and A. Seifalian, Emerging Application of Magnetic Nanoparticles for Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer. Polymers (Basel), 2021. 13(23). [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Torres, M., et al., Polymeric Composite of Magnetite Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Application in Biomedicine: A Review. Polymers (Basel), 2022. 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Ognjanović, M., et al., Bifunctional (Zn,Fe)3O4 nanoparticles: Tuning their efficiency for potential application in reagentless glucose biosensors and magnetic hyperthermia. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2019. 777: p. 454-462. [CrossRef]

- Antarnusa, G. and E. Suharyadi, A synthesis of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coated magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their characteristics for enhancement of biosensor. Materials Research Express, 2020. 7(5): p. 056103. [CrossRef]

- Xing Guo, J.H., Yang Ge, Dong Zhao, Shengbo Sang and Jianlong Ji, Highly Sensitive Magnetoelastic Biosensor for Alpha2-Macroglobulin Detection Based on MnFe2O4@chitosan. Micromachines, 2023. 14(401).

- Orooji, Y., et al., Cerium doped magnetite nanoparticles for highly sensitive detection of metronidazole via chemiluminescence assay. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2020. 234: p. 118272. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., One-step solvothermal synthesis of Fe3O4@Cu@Cu2O nanocomposite as magnetically recyclable mimetic peroxidase. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2016. 682: p. 432-440. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Magnetic Fe3O4@MOFs decorated graphene nanocomposites as novel electrochemical sensor for ultrasensitive detection of dopamine. RSC Advances, 2015. 5(119): p. 98260-98268. [CrossRef]

- Guivar, J.A., E.G. Fernandes, and V. Zucolotto, A peroxidase biomimetic system based on Fe3O4 nanoparticles in non-enzymatic sensors. Talanta, 2015. 141: p. 307-14. [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C., et al., Comparison and functionalization study of microemulsion-prepared magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Langmuir, 2012. 28(22): p. 8479-85. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J., et al., Air-stable Fe@Au nanoparticles synthesized by the microemulsion’s methods. Journal of the Korean Physical Society, 2013. 62(10): p. 1376-1381. [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.G.S.d., et al., Luminomagnetic Silica-Coated Heterodimers of Core/Shell FePt/Fe3O4 and CdSe Quantum Dots as Potential Biomedical Sensor. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2017. 2017: p. 1-9.

- Ying, S., et al., Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Current developments and limitations. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 2022. 26: p. 102336. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.S., et al. A Review on Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Diverse Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Catalysts, 2022. 12,. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Beltran, C.H., et al., One-minute and green synthesis of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles assisted by design of experiments and high energy ultrasound: Application to biosensing and immunoprecipitation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl, 2021. 123: p. 112023. [CrossRef]

- Satvekar, R.K. and S.H. Pawar, Multienzymatic Cholesterol Nanobiosensor Using Core–Shell Nanoparticles Incorporated Silica Nanocomposite. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, 2018. 38(5): p. 735-743. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian-Fard-Fini, S., M. Salavati-Niasari, and D. Ghanbari, Hydrothermal green synthesis of magnetic Fe(3)O(4)-carbon dots by lemon and grape fruit extracts and as a photoluminescence sensor for detecting of E. coli bacteria. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc, 2018. 203: p. 481-493. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y., Y. Li, and D.S. Lee, Functionalization of Magnetic Nanoparticles with Organic Ligands toward Biomedical Applications. Advanced NanoBiomed Research, 2021. 1(5): p. 2000043. [CrossRef]

- Serrano García, R., S. Stafford, and Y.K. Gun’ko Recent Progress in Synthesis and Functionalization of Multimodal Fluorescent-Magnetic Nanoparticles for Biological Applications. Applied Sciences, 2018. 8,. [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Torres, M., et al. Polymeric Composite of Magnetite Iron Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Application in Biomedicine: A Review. Polymers, 2022. 14,. [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, T., et al., Electrochemical DNA Sensors with Layered Polyaniline-DNA Coating for Detection of Specific DNA Interactions. Sensors (Basel), 2019. 19(3). [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q., et al., Sensitive electrochemical DNA sensor for the detection of HIV based on a polyaniline/graphene nanocomposite. Journal of Materiomics, 2019. 5(2): p. 313-319. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., et al. Application of Polypyrrole-Based Electrochemical Biosensor for the Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13. [CrossRef]

- Tertiş, M., et al., Label-free electrochemical aptasensor based on gold and polypyrrole nanoparticles for interleukin 6 detection. Electrochimica Acta, 2017. 258: p. 1208-1218. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., et al., Multifunctional glucose biosensors from Fe(3)O(4) nanoparticles modified chitosan/graphene nanocomposites. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 11129. [CrossRef]

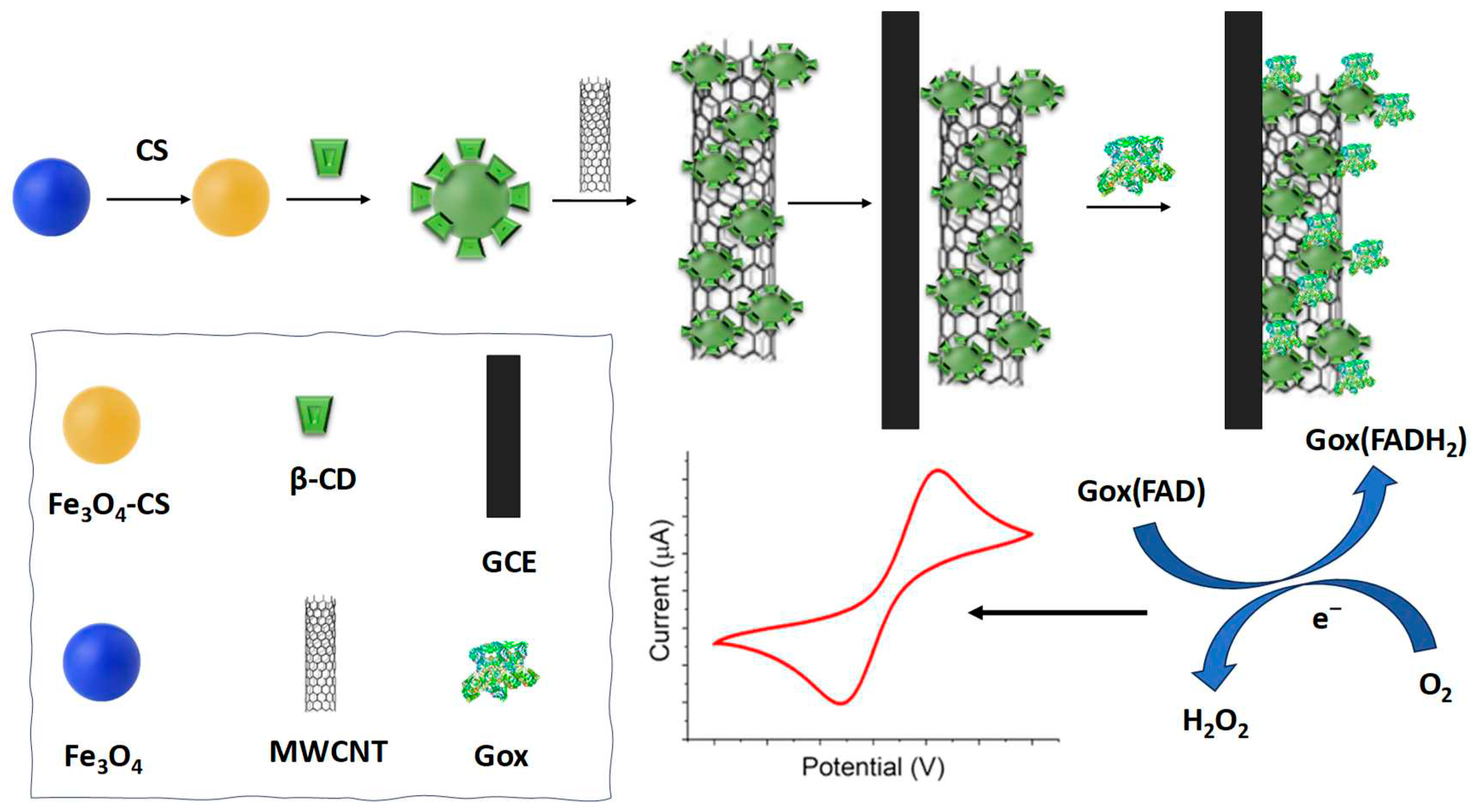

- Peng, L., et al., A Novel Amperometric Glucose Biosensor Based on Fe3O4-Chitosan-β-Cyclodextrin/MWCNTs Nanobiocomposite. Electroanalysis, 2020. 33(3): p. 723-732. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., X. Ni, and Y. Cao, Electrochemical determination of hemoglobin on a magnetic electrode modified with chitosan based on electrocatalysis of oxygen. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 2019. 837: p. 219-225.

- Di Tocco, A., et al., Development of an electrochemical biosensor for the determination of triglycerides in serum samples based on a lipase/magnetite-chitosan/copper oxide nanoparticles/multiwalled carbon nanotubes/pectin composite. Talanta, 2018. 190: p. 30-37. [CrossRef]

- Lv, S., et al., The detection of brucellosis antibody in whole serum based on the low-fouling electrochemical immunosensor fabricated with magnetic Fe(3)O(4)@Au@PEG@HA nanoparticles. Biosens Bioelectron, 2018. 117: p. 138-144. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y., et al., Visual determination of hydrogen peroxide and glucose by exploiting the peroxidase-like activity of magnetic nanoparticles functionalized with a poly(ethylene glycol) derivative. Microchimica Acta, 2017. 184(7): p. 2115-2122. [CrossRef]

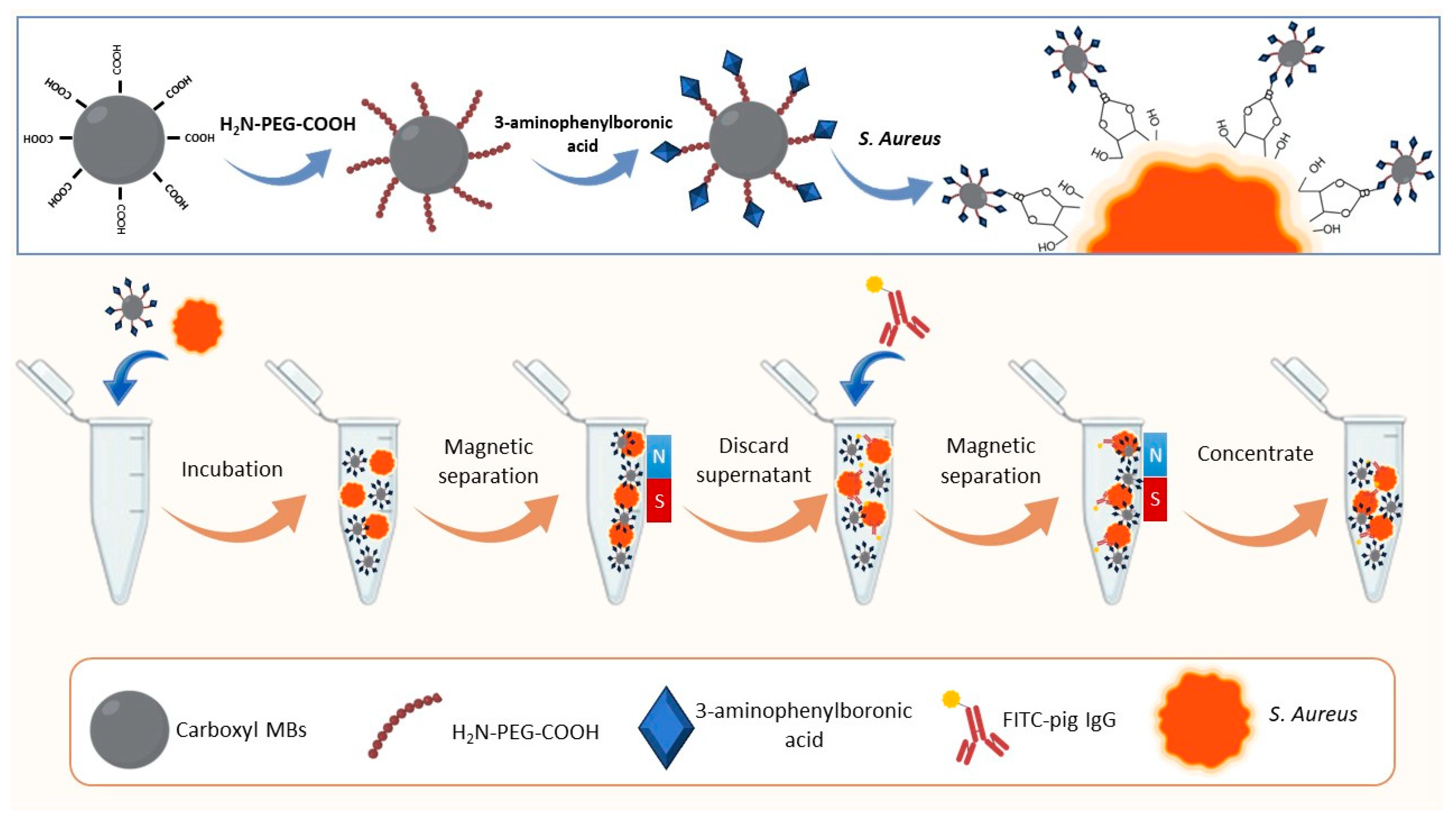

- Wang, Z., et al., A novel PEG-mediated boric acid functionalized magnetic nanomaterials based fluorescence biosensor for the detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Microchemical Journal, 2022. 178: p. 107379. [CrossRef]

- Cha, B.G., et al., Iron Oxide@Polypyrrole Core–Shell Nanoparticles as the Platform for Photothermal Agent and Electrochemical Biosensor. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2016. 16(7): p. 6942-6948. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S., et al., Development of Voltammetric Glucose-6-phosphate Biosensors Based on the Immobilization of Glucose-6-phosphate Dehydrogenase on Polypyrrole- and Chitosan-Coated Fe(3)O(4) Nanoparticles/Polypyrrole Nanocomposite Films. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2019. 188(4): p. 1145-1157. [CrossRef]

- Song, E., et al., A polypyrrole-mediated photothermal biosensor with a temperature and pressure dual readout for the detection of protein biomarkers. Analyst, 2022. 147(12): p. 2671-2677. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S., H. Lang, and D. Bahadur, Polyaniline-iron oxide nanohybrid film as multi-functional label-free electrochemical and biomagnetic sensor for catechol. Anal Chim Acta, 2013. 795: p. 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Wen, T., et al., Novel electrochemical sensing platform based on magnetic field-induced self-assembly of Fe3O4@Polyaniline nanoparticles for clinical detection of creatinine. Biosens Bioelectron, 2014. 56: p. 180-5. [CrossRef]

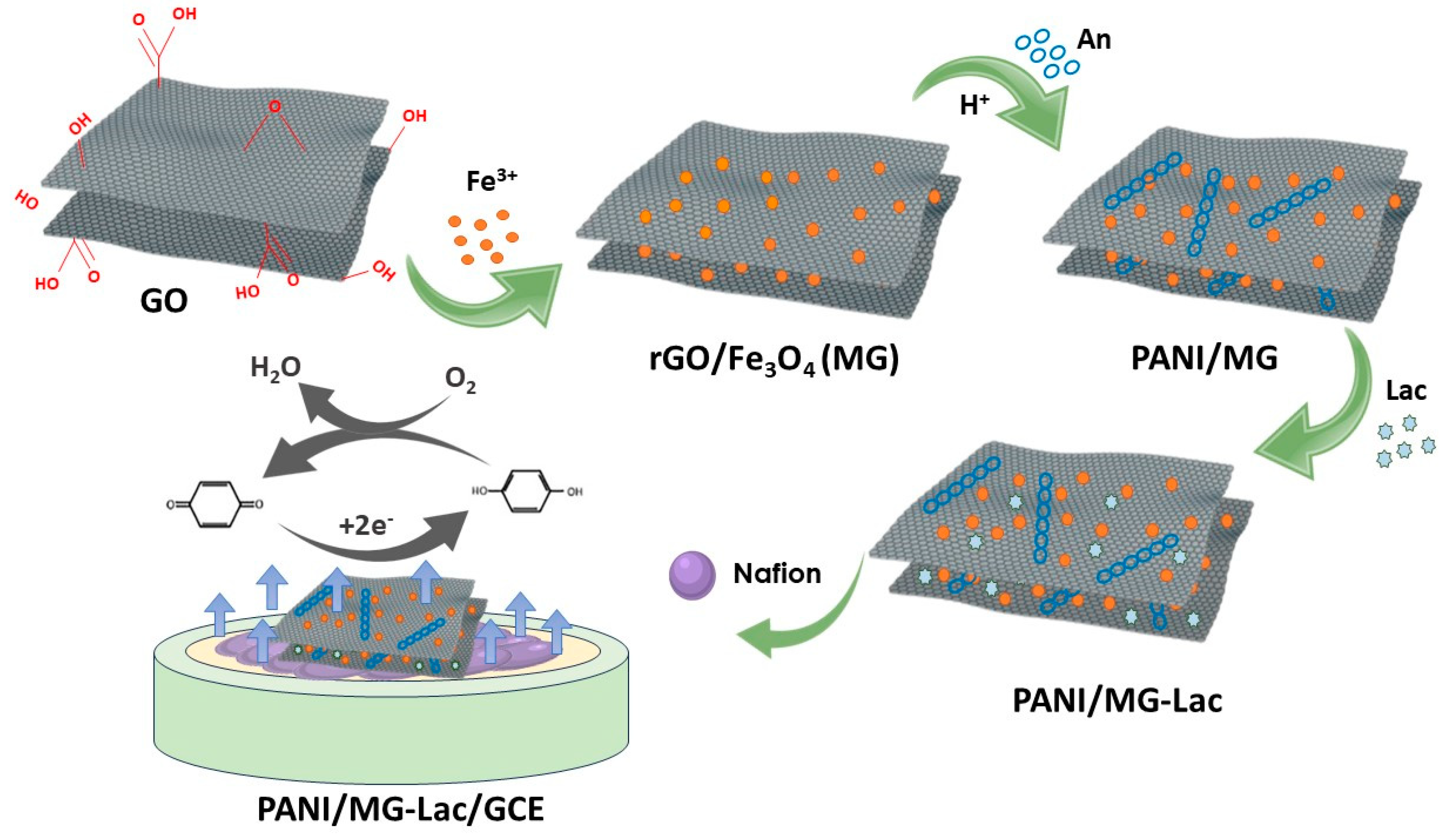

- Lou, C., et al., Laccase immobilized polyaniline/magnetic graphene composite electrode for detecting hydroquinone. Int J Biol Macromol, 2020. 149: p. 1130-1138. [CrossRef]

- Hsine, Z., et al., Recent progress in graphene based modified electrodes for electrochemical detection of dopamine. Chemosensors, 2022. 10(7): p. 249. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.P., et al., Facile preparation of novel core-shell enzyme-Au-polydopamine-Fe(3)O(4) magnetic bionanoparticles for glucosesensor. Biosens Bioelectron, 2013. 42: p. 293-9.

- Martin, M., et al., Rapid Legionella pneumophila determination based on a disposable core-shell Fe(3)O(4)@poly(dopamine) magnetic nanoparticles immunoplatform. Anal Chim Acta, 2015. 887: p. 51-58. [CrossRef]

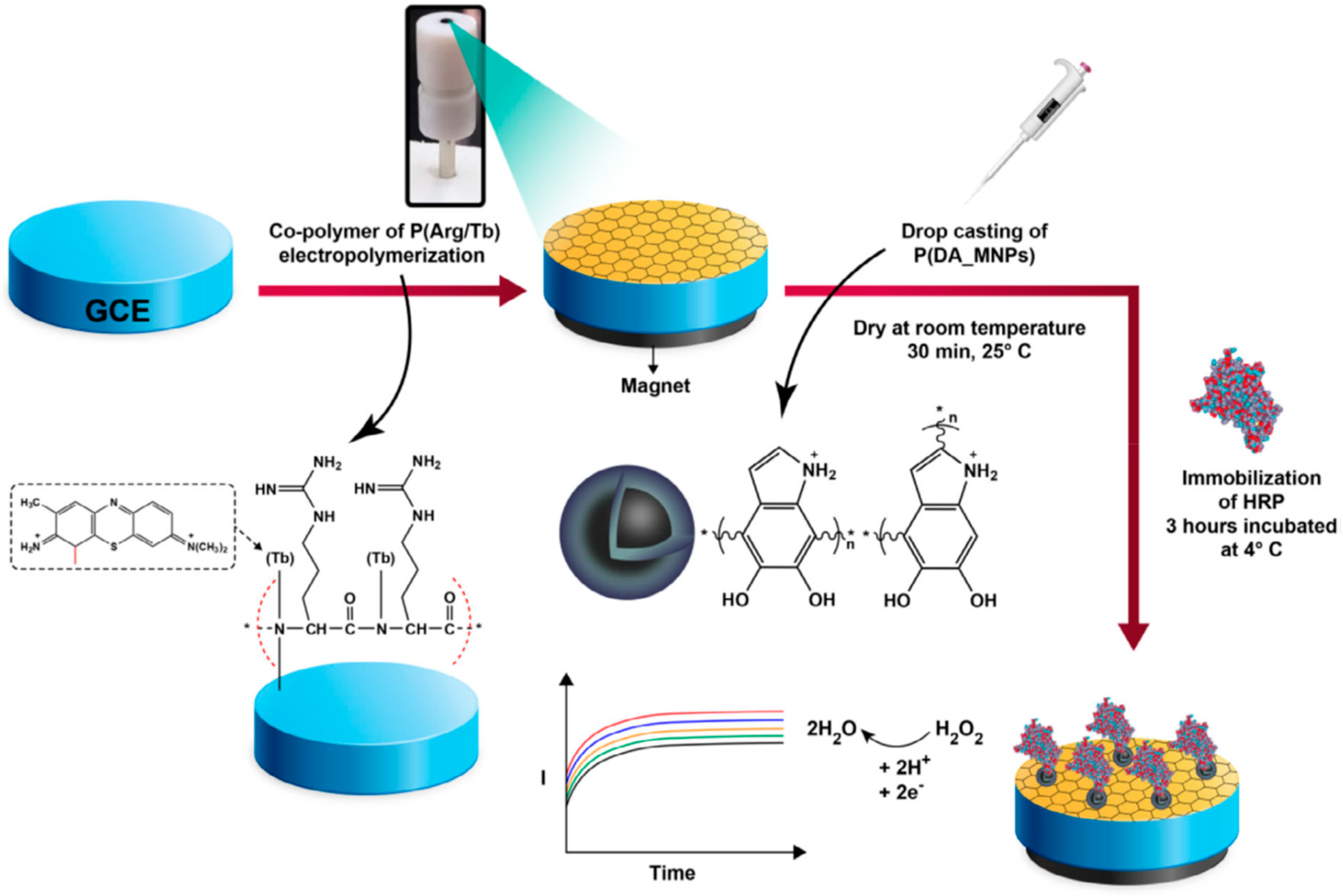

- Sardaremelli, S., M. Hasanzadeh, and F. Seidi, Enzymatic recognition of hydrogen peroxide (H(2) O(2) ) in human plasma samples using HRP immobilized on the surface of poly(arginine-toluidine blue)- Fe(3) O(4) nanoparticles modified polydopamine; A novel biosensor. J Mol Recognit, 2021. 34(11): p. e2928.

- Rashid, Z., et al., Effective surface modification of MnFe 2 O 4 @SiO 2 @PMIDA magnetic nanoparticles for rapid and high-density antibody immobilization. Applied Surface Science, 2017. 426: p. 1023-1029. [CrossRef]

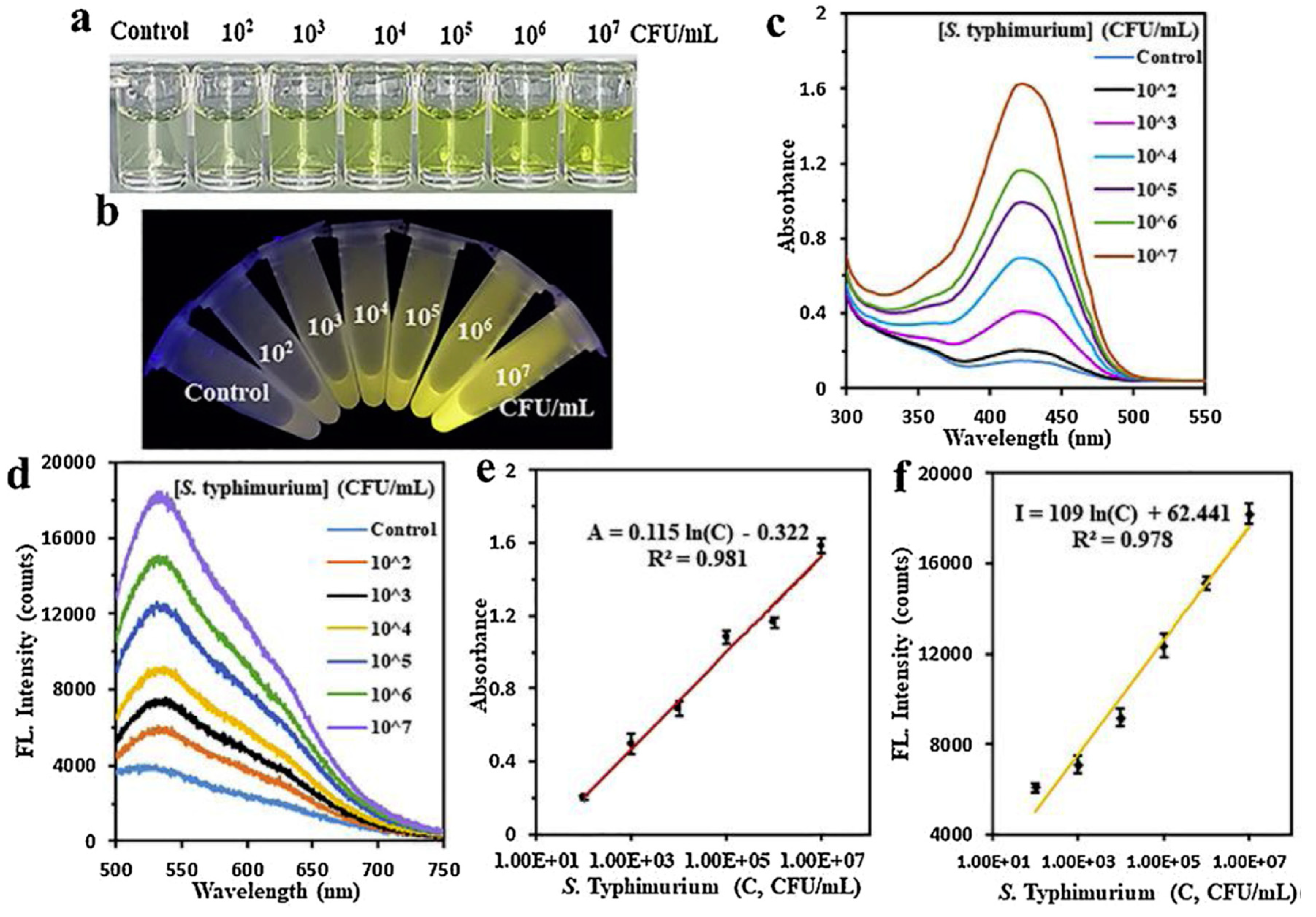

- Huang, F., et al., An Acid-Responsive Microfluidic Salmonella Biosensor Using Curcumin as Signal Reporter and ZnO-Capped Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Signal Amplification. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2020. 312: p. 127958.

- Javad Ghodsi, A.H., Amir Abbas Rafati, Yalda Shoja, Olena Yurchenko and a.G. Urban, Electrostatically immobilized hemoglobin on silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles for simultaneous determination of dopamine, uric acid, and folic acid. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2016. 163(13). [CrossRef]

- Achadu, O.J., et al., 3D hierarchically porous magnetic molybdenum trioxide@gold nanospheres as a nanogap-enhanced Raman scattering biosensor for SARS-CoV-2. Nanoscale Adv, 2022. 4(3): p. 871-883.

- Seo-Eun Lee, S.-E.J., Jae-Sang Hong, Hyungsoon Im, Sei-Young Hwang, Jun Kyun Oh and Seong-Eun Kim, Gold-Nanoparticle-Coated Magnetic Beads for ALP-Enzyme-Based Electrochemical Immunosensing in Human Plasma. Materials, 2022. 15(19). [CrossRef]

- Khoshfetrat, S.M. and M.A. Mehrgardi, Amplified detection of leukemia cancer cells using an aptamer-conjugated gold-coated magnetic nanoparticles on a nitrogen-doped graphene modified electrode. Bioelectrochemistry, 2017. 114: p. 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Magnetic Fe(3)O(4)-Based Sandwich-Type Biosensor Using Modified Gold Nanoparticles as Colorimetric Probes for the Detection of Dopamine. Materials (Basel), 2013. 6(12): p. 5690-5699. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., et al., An ultrasensitive electrochemical biosensor for bisphenol A based on aptamer-modified MrGO@AuNPs and ssDNA-functionalized AuNP@MBs synergistic amplification. Chemosphere, 2022. 311(Pt 2): p. 137154.

- He, C., et al., A Highly Sensitive Glucose Biosensor Based on Gold Nanoparticles/Bovine Serum Albumin/Fe3O4 Biocomposite Nanoparticles. Electrochimica Acta, 2016. 222: p. 1709-1715. [CrossRef]

- Della Ventura, B., et al., Gold Coated Nanoparticles Functionalized by Photochemical Immobilization Technique for Immunosensing. 2021. 753: p. 113-118. [CrossRef]

- Weng, C., et al., A label-free electrochemical biosensor based on magnetic biocomposites with DNAzyme and hybridization chain reaction dual signal amplification for the determination of Pb(2). Mikrochim Acta, 2020. 187(10): p. 575. [CrossRef]

- Choi, G., et al., A cost-effective chemiluminescent biosensor capable of early diagnosing cancer using a combination of magnetic beads and platinum nanoparticles. Talanta, 2017. 162: p. 38-45. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S., et al., Pt-Decorated Magnetic Nanozymes for Facile and Sensitive Point-of-Care Bioassay. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 2017. 9(40): p. 35133-35140.

- Borisova, B., et al., Reduced graphene oxide-carboxymethylcellulose layered with platinum nanoparticles/PAMAM dendrimer/magnetic nanoparticles hybrids. Application to the preparation of enzyme electrochemical biosensors. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2016. 232: p. 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Šafranko, S., et al., An Overview of the Recent Developments in Carbon Quantum Dots—Promising Nanomaterials for Metal Ion Detection and (Bio) Molecule Sensing. Chemosensors, 2021. 9(6): p. 138. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, C., et al., Development of magnetic nanoparticle assisted aptamer-quantum dot based biosensor for the detection of Escherichia coli in water samples. Sci Total Environ, 2022. 831: p. 154857. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R., et al., Fluorescence detection of histamine based on specific binding bioreceptors and carbon quantum dots. Biosens Bioelectron, 2020. 167: p. 112519. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).