1. Introduction

The hydrogen-storage capacity of magnesium is high, its price is low, and its reserves in the earth’s crust are large. However, its reaction rate with hydrogen is low even at relatively high temperature such as at 573 K [

1]. A lot of work to improve the hydriding and dehydriding rates of magnesium has been performed by alloying with magnesium certain metals [

2,

3] such as Cu [

4], Ni [

5,

6], In [

7] , Sn [

8] , V [

9], and Ni and Y [

10].

Reilly et al. [

5] and Akiba et al. [

6] improved the reaction kinetics of Mg with H

2 by preparing Mg-Ni alloys. Song et al. [

11,

12,

13,

14] increased the hydriding and dehydriding rates of Mg by mechanical alloying of Mg with Ni under Ar atmosphere. Bobet et al. [

15] improved the hydrogen-storage properties of both magnesium and Mg+10 wt% Co, Ni, or Fe mixtures by mechanical milling under H

2 (reaction-involved milling) for a short time (2 h).

Many researchers are interested in hydrogen production and storage based on the use of renewable energy resources. In a renewable energy-based hydrogen economy, the distribution of hydrogen from the producer to the consumer is currently the missing key technology.

There are three types of methane reforming: steam reforming, autothermal reforming, and partial oxidation. These are chemical processes which can produce pure hydrogen gas from methane using a catalyst. Most methods work by exposing methane to a catalyst (usually nickel) at high temperature and pressure [

16].

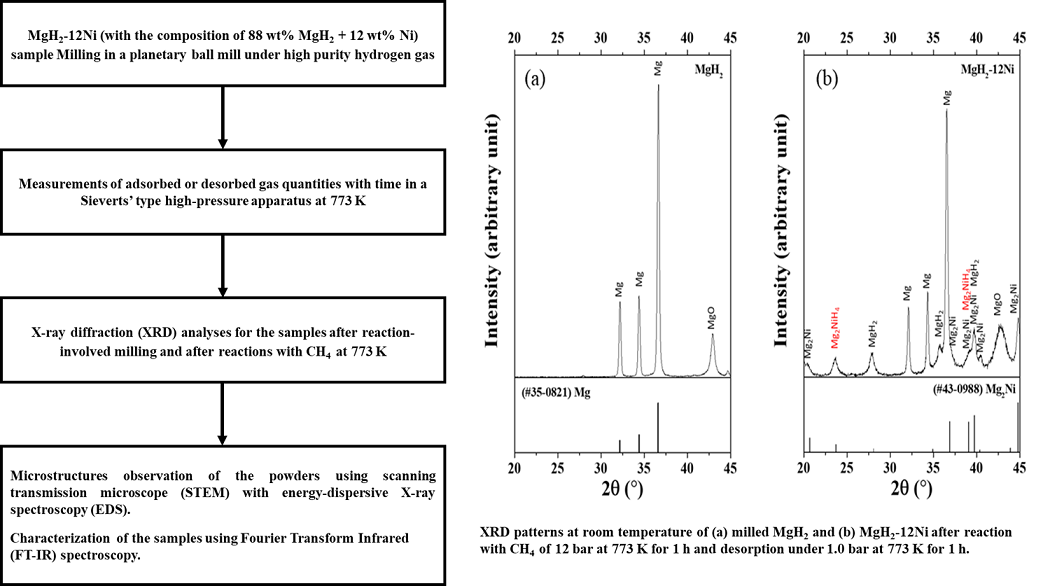

In this work, a new study for CH4 reforming to hydrogen and storage of hydrogen was performed using magnesium-based alloy. MgH2 -12Ni (with the composition of 88 wt% MgH2 + 12 wt% Ni) was prepared in a planetary ball mill by milling under hydrogen gas (reaction-involved milling). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses were performed for the samples after reaction-involved milling and after reactions with CH4. The variation of adsorbed or desorbed gas with time was measured by a Sieverts’ type high-pressure apparatus at 773 K. The microstructures of the powders were observed using scanning transmission microscope (STEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The synthesized samples were also characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy.

Over recent decades, there has been increasing interest about the environmental consequences of the use of fossil fuels in the production of electricity and the propulsion of vehicles. The burden dependence of industrialized countries on fossil fuels was noted during the oil crisis of the 1970’s [

17]. As human population increases exponentially across the globe, the quest for finding energy production methods that reduce the general dependence on fossil fuels, while mitigating poisonous emissions, has continued. Electrochemical devices, particularly fuel cell systems, have enormous potential for revolutionizing the manner in which power is produced and utilized. Direct electrochemical production promises increased energy efficiency, reduced dependence on non-renewable resources, and reduced environmental impact. However, fundamental challenges remain in developing the materials systems necessary to achieve the required levels of performance and durability, and bring solid oxide fuel cell technology to fruition.

Fuel cells are energy conversion devices, producing electricity by electrochemically combining fuel and oxidant gases across an electrolyte [

17]. The scientist William Grove is credited with first demonstrating the fuel cell concept and associated electrochemical processes in 1839 [

18]. He reversed the process of electrolysis – whereby hydrogen and oxygen are recombined – and showed that a small electrical current can be produced [

3]. Although the concept was demonstrated over 170 years ago, fuel cells have only recently garnered serious consideration as an economically and technically viable power source.

As next-generation power sources compared with conventional energy systems, fuel cells have a number of advantages, and thus have gained popular recognition. A key feature of a fuel cell system is its high energy conversion efficiency. Since a fuel cell converts the chemical energy of the fuel directly to electrical energy, its conversion efficiency is not subject to the Carnot limitation [

19]. Other advantages relative to conventional power production methods include modular construction, high efficiency at partial load, minimal siting restrictions, the potential for cogeneration, and much lower generation of pollutants [

19].

One of the studies to apply the fuel cells to practical use is hydrogen generation and storage. We could generate hydrogen from CH4 and store hydrogen in a form of metal hydride with nano sizes at the same time. The results of the present work can be applied to production of hydrogen and storage of hydrogen, which can be used for supplying hydrogen to fuel cells. It is thought that the materials developed in our work can be used for motive power fuel and portable appliances as mobile applications, transport and distribution as semi-mobile applications, and industrial off-peak power H2-generation, hydrogen-purifying systems, and heat pumps as stationary applications.

2. Materials and Methods

MgH2 (Magnesium hydride, 98%, Alfa Aesar), Ni (average particle size 2.2–3.0 um, purity 99.9 % metal basis, C typically < 0.1%, Alfa Aesar), and CH4 (purity 99.95%, O2 < 5 ppm, N2 < 100 ppm, H2O < 5 ppm, H2 < 1 ppm, THC (total hydrocarbon content) < 5 ppm, and CO/CO2 < 1 ppm, Korea Noble Gas Co. Ltd) were used as starting materials.

A mixture with the composition of 88 wt% MgH2 +12 wt% Ni (total weight, 8 g) was placed in a hermetically sealed stainless steel container with 105 hardened steel balls (total weight of 360 g). The sample–to–ball weight ratio was 1/45. Samples were handled in a glove box under Ar to prevent the oxidation. MgH2-12Ni with the composition of 88 wt% MgH2 +12 wt% Ni was prepared in a planetary ball mill (Planetary Mono Mill; Pulverisette 6, Fritsch) by milling at a disc revolution speed of 400 rpm under high purity hydrogen gas of 12 bar for 6 h.

The variation of absorbed or desorbed gas quantity with time was measured by a Sieverts’ type high-pressure apparatus previously described [

20]. The sample quantity used for this measurement was 0.5 g.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns for the samples after reaction-involved milling and after adsorption–desorption cycling were obtained in a Rigaku D/MAX 2500 powder diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. The analysis of the XRD patterns was performed using the program MDI JADE 5.0. JCPDS card data PDF-2 2004 of the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) were used for phase identification.

The synthesized samples were also characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Frontier, PerkinElmer).

The microstructures of the powders were observed using a JEM-ARM200F cs_corrected-Field Emission Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy EDS (Hitachi Su-70 Schottky Field Emission SEM-Oxford Aztec 80mm/124ev EDX) operated at 200 kV.

3. Results

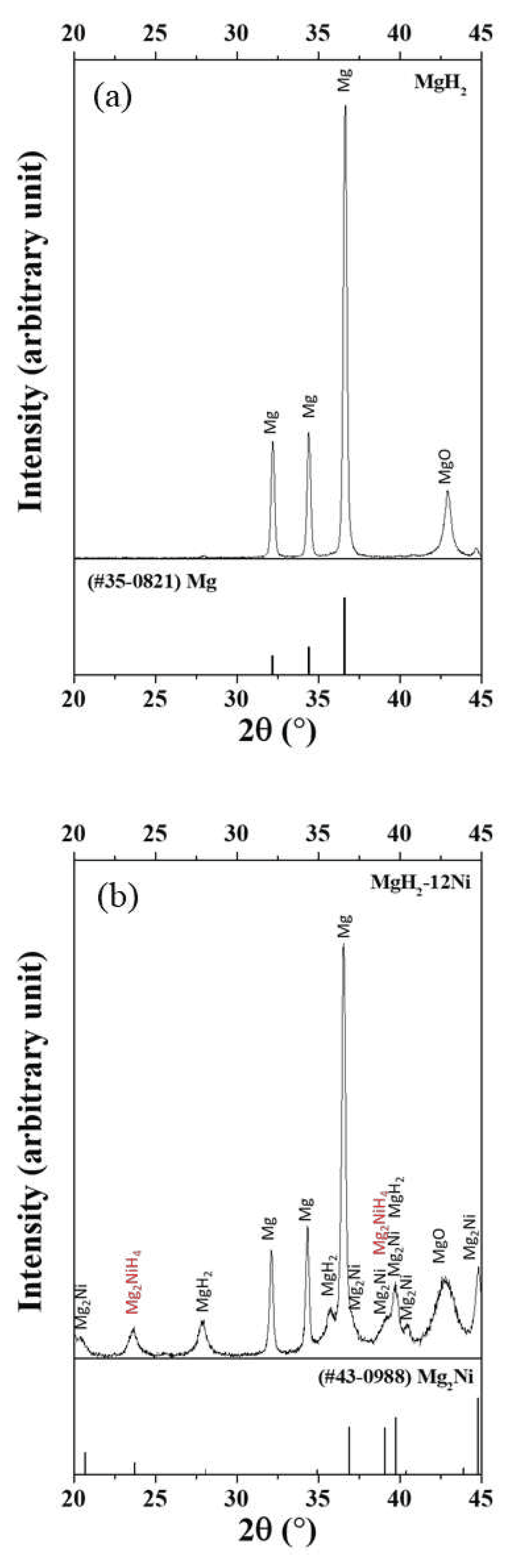

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns at room temperature of milled MgH

2 and MgH

2-12Ni after reaction with CH

4 of 12 bar at 773 K for 1 h and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K for 1 h.

When the milled MgH

2 was heated up to 773 K under 1.0 bar CH

4 and vacuum pumped, the hydrogen in the milled MgH

2 is thought to have been removed. It is believed that Mg

2Ni was formed during heating up to 773 K [

21]. When the MgH

2-12Ni was heated up to 773 K under 1.0 bar CH

4 and vacuum pumped, the hydrogen in the MgH

2 is thought to have been removed.

The XRD pattern of the milled MgH2 after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K exhibited phases of Mg and MgO. MgO is believed to have been formed during sample exposure to air for XRD pattern obtention. This shows that reforming of CH4 had not taken place.

The XRD pattern of MgH2-12Ni after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K exhibited phases of MgH2, Mg2NiH4, Mg, Mg2Ni, and MgO. The formations of MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 show that reforming of CH4 had taken place, reformed CH4 (hydrogen-containing mixture) is adsorbed on the particles, and MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 hydrides were believed to have been formed by the reactions of Mg (formed during heating up to 773 K under 1.0 bar and vacuum pumping at 773 K) and Mg2Ni (formed during heating up to 773 K) with hydrogen (formed from the reforming of CH4 and adsorbed on the particles) during cooling to room temperature.

Figure 2 shows quantity of reformed CH

4 versus time t in 12 bar CH

4 at 773 K and desorbed quantity of reformed CH

4 versus t in 1.0 bar at 773 K for MgH

2-12Ni. The quantity of reformed CH

4 in 12 bar CH

4 at 773 K was 0.8 wt% for 1 min and 1.17 wt% for 60 min. The desorbed quantity of reformed CH

4 (hydrogen-containing mixture) in 1.0 bar at 773 K was 0.8 wt% for 1 min and 1.17 wt% for 60 min.

Attenuated total reflectance FT-IR spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) spectra of MgH

2-12Ni reacted with 12 bar CH

4 at 723 K and 773 K are shown in

Figure 3. Peaks for C-H bending, C=C stretching, and C=C bending resulting from CH

4 reforming were observed [

22,

23]. Peaks for O-H stretching, C=O stretching, and C-O stretching are believed to be formed due to a reaction with oxygen in air.

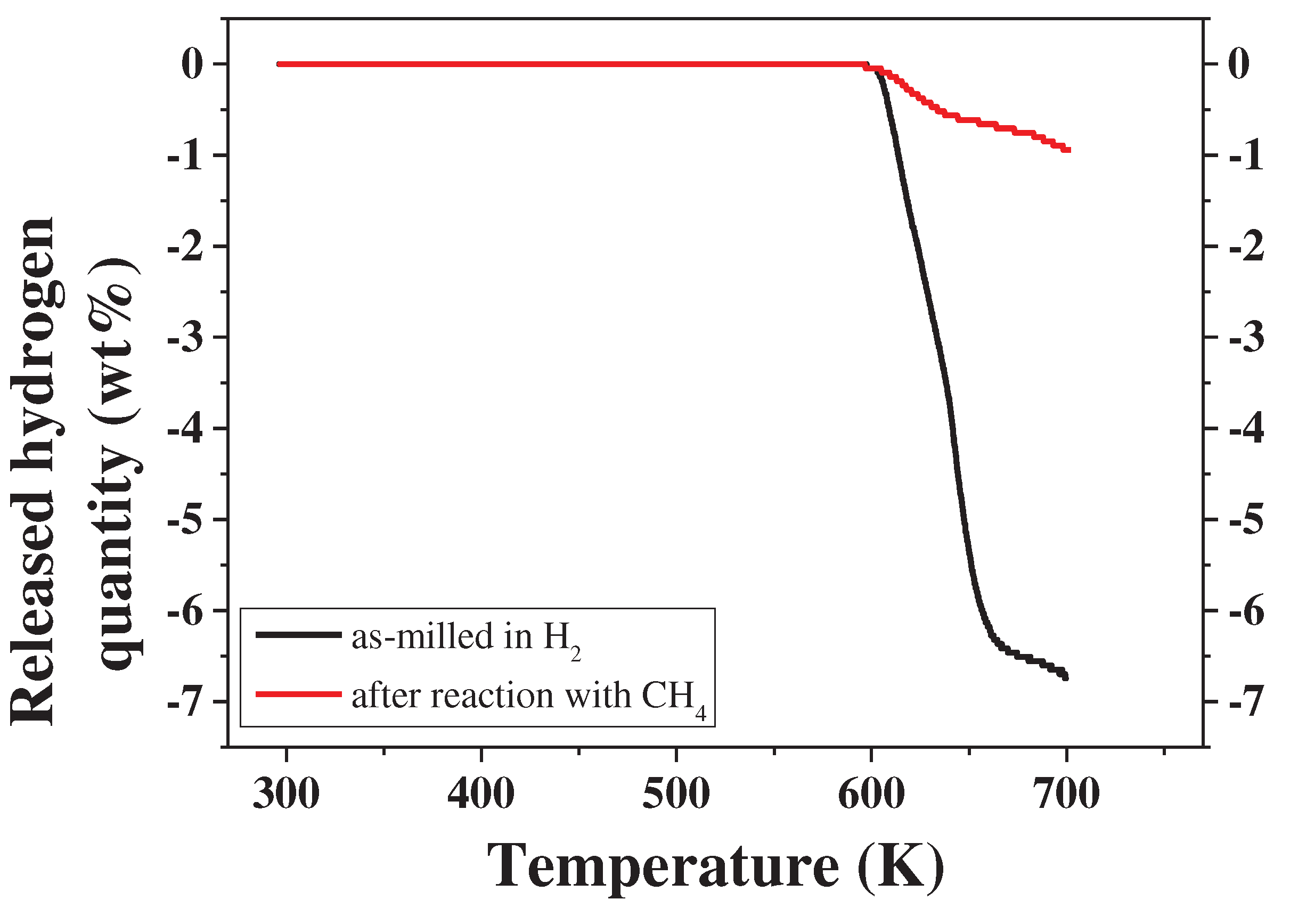

Figure 4 shows the released hydrogen quantity versus temperature T curve for as-milled MgH

2-12Ni and the released gas quantity versus T curve for MgH

2-12Ni after reaction with CH

4 of 12 bar when heated at a heating rate of 5–6 K/min.

The as-milled MgH2-12Ni released hydrogen of 5.09 wt% up to about 648 K relatively rapidly and released hydrogen of 6.74 wt% up to about 700 K slowly. MgH2-12Ni after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar released gas (hydrogen-containing mixture) of 0.66 wt% up to about 663 K rapidly and 0.94 wt% up to about 702 K slowly.

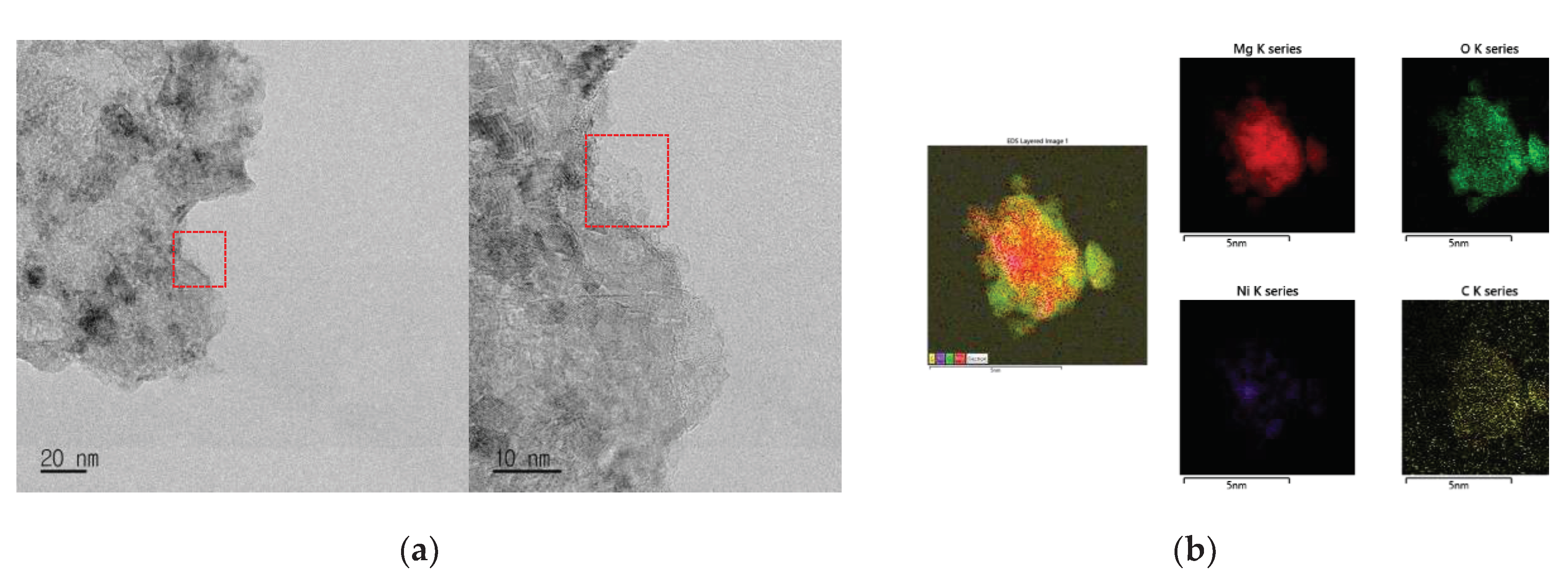

Figure 5 shows STEM images and EDS images of MgH

2-12Ni reacted with CH

4 of 12 bar at 773 K for 1 h. The STEM images exhibit irregular shape of a particle. The EDS images show that the distribution of Mg, Ni, O, and C on the particle is quite homogeneous.

4. Discussion

Figure 2 shows that the quantity of reformed CH

4 in 12 bar CH

4 at 773 K was 1.17 wt% . MgH

2-12Ni after reaction with CH

4 of 12 bar released gas (hydrogen-containing mixture) of 0.66 wt% up to about 663 K rapidly and 0.94 wt% up to about 702 K slowly (

Figure 4).

The Pressure-Composition isotherms (P-C-T diagram) in metal-hydrogen systems exhibit equilibrium plateau pressures at various temperatures. The equilibrium plateau pressures are the equilibrium hydrogen pressures at which metal and hydrogen coexist under equilibrium. At a certain temperature, in order for a metal hydride to be formed, hydrogen with a pressure higher than the equilibrium hydrogen pressure must be applied. At 773 K, the equilibrium hydrogen pressures of Mg and Mg

2Ni are much higher than 12 bar, which was applied in the present work. The equilibrium plateau pressure at 773 K is 103 bar for Mg-H system [

24] and 115 bar for Mg

2Ni-H system [

25]. It is thus believed that the hydrides of Mg and Mg

2Ni are not formed after the reaction with CH

4 of 12 bar at 773 K. CH

4 is reformed and reformed gas mixture is adsorbed, and the hydrides of Mg and Mg

2Ni are formed during cooling to room temperature by the reactions of Mg and Mg

2Ni with hydrogen. The equilibrium plateau pressure is 1 bar at 557 K for Mg-H system [

24] and at 527 K for Mg

2Ni-H system [

25]. At temperatures from 473 K to room temperature (during cooling), the equilibrium plateau pressures of Mg-H and Mg

2Ni-H systems are very low, the formation of MgH

2 and Mg

2NiH

4 being possible.

The XRD pattern of the milled MgH2 after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K did not exhibited the MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 phases. However, the XRD pattern of MgH2-12Ni after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K exhibited the MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 phases. This shows that reforming of CH4 had taken place, reformed CH4 (hydrogen-containing mixture) was adsorbed on the particles, and MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 hydrides were believed to have been formed by the reactions of Mg (formed during heating up to 773 K under 1.0 bar and vacuum pumping at 773 K) and Mg2Ni (formed during heating up to 773 K) with hydrogen (formed from the reforming of CH4 and adsorbed on the particles) during cooling to room temperature.

The addition of Ni for sample preparation is thought to have led to different result for the particles. The surface state of the MgH

2-12Ni and the larger surface area of the MgH

2-12Ni than the milled MgH

2 might have played a role on the reformation of CH

4. However, the Ni and Mg

2Ni formed during heating up to 773 K are believed to have brought about catalytic effects for reforming CH

4, playing a more strong role on the reformation of CH

4. It was reported that most methods for methane reforming usually used nickel as a catalyst [

16].

Transition metals such as Ni are reported to have catalytic effects on the absorption of gases [

26]. The added Ni (and less possibly Mg

2Ni) might have helped CH

4 be adsorbed on the particles.

In our future researches, gas chromatography analyses will be performed for the gases which are obtained after the reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K. This will help the present work to be verified.

5. Conclusions

CH4 reforming to hydrogen and storage of hydrogen was studied using magnesium-based alloy. MgH2-12Ni (with the composition of 88 wt% MgH2 + 12 wt% Ni) was prepared in a planetary ball mill under high purity hydrogen gas. XRD pattern of MgH2-12Ni after reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and desorption under 1.0 bar at 773 K exhibited phases of MgH2 and Mg2NiH4. This shows that reforming of CH4 was occurred, the reformed CH4 (hydrogen-containing mixture) is then adsorbed on the particles, and hydrides were formed during cooling to room temperature. Ni and Mg2Ni formed during heating up to 773 K are believed to have brought about catalytic effects for reforming CH4. MgH2-12Ni adsorbed 0.8 wt% reformed CH4 within 1 min in a reaction with CH4 of 12 bar at 773 K and then desorbed 0.8 wt% reformed CH4 within 1 min under H2 of 1 bar at 773 K. Attenuated total reflectance FT-IR spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) spectra of MgH2-12Ni after reactions under 12 bar CH4 at 723 K and 773 K showed peaks of C-H bending, C=C stretching, O-H stretching, O-H bending, and C-O stretching.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; Song, M.Y.; methodology, Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; Song, M.Y.; formal analysis, Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; Song, M.Y.; investigation, Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; Song, M.Y.; data curation, Kwak, Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Kwak, Y.J. .; Song, M.Y.; writing—review and editing—Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; Song, M.Y.; project administration, Kwak, Y.J.; Lee, K.-T.; funding acquisition, Kwak, Y.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1C1C2009103).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Han, J.S.; Park, K. D. Thermal analysis of Mg hydride by Sieverts’ type automatic apparatus. Korean J. Met. Mater. 2010, 48, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Kwon, S.N.; Song, M.Y. Hydrogen storage characteristics of melt spun Mg-23.5Ni-xCu alloys and Mg-23.5Ni-2.5Cu alloy mixed with Nb2O5 and NbF5. In Korean J. Met. Mater.; 2011; Volume 49, pp. 298–303, UCI : G704-000085.2011.49.4.004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.I.; Hong, T.W. Hydrogenation properties of Mg-5wt.% TiCr10NbX (x=1,3,5) composites by mechanical alloying process. Korean J. Met. Mater. 2011, 49, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Wiswall, R.H. Reaction of hydrogen with alloys of magnesium and copper. Inorg. Chem. 1967, 6, 2220–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J.; Wiswall, R.H. Reaction of hydrogen with alloys of magnesium and nickel and the formation of Mg2NiH4. Inorg. Chem. 1968, 7, 2254–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, E.; Nomura, K.; Ono, S.; Suda, S. Kinetics of the reaction between Mg-Ni alloys and H2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1982, 7, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, E.; Nomura, K.; Ono, S.; Suda, S. Kinetics of the reaction between Mg-Ni alloys and H2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1982, 7, 787–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.C.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.Z.; Zhu., M. Microstructure and hydrogen storage properties of Mg–Sn nanocomposite by mechanical milling. J. Alloy Compd. 2011, 509(11), 4268–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, P.; Song, X.; Liu, J.; Song, A.; Zhang, P.; Chen, G. Study on the hydrogen desorption mechanism of a Mg–V composite prepared by SPS. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37(1), 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, S. Characterization of Mg–20 wt% Ni–Y hydrogen storage composite prepared by reactive mechanical alloying. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32(12), 1869–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y. Improvement in hydrogen storage characteristics of magnesium by mechanical alloying with nickel. J. Mater. Sci. 1995, 30, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Ivanov, E.I.; Darriet, B.; Pezat, M.; Hagenmuller, P. Hydriding properties of a mechanically alloyed mixture with a composition Mg2Ni. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1985, 10, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Ivanov, E.I.; Darriet, B.; Pezat, M.; Hagenmuller, P. Hydriding and dehydriding characteristics of mechanically alloyed mixtures Mg-xwt.%Ni (x = 5, 10, 25 and 55). J. Less-Common Met. 1987, 131, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y. Effects of mechanical alloying on the hydrogen storage characteristics of Mg-xwt% Ni (x = 0, 5, 10, 25 and 55) mixtures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1995, 20, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobet, J.-L.; Akiba, E.; Nakamura, Y.; Darriet, B. Study of Mg-M (M=Co, Ni and Fe) mixture elaborated by reactive mechanical alloying — hydrogen sorption properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2000, 25, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methane_reformer (visited on June 18, 2023).

- Carrette, L.; Friedrich, K.A.; Stimming, U. Fuel cells- Fundamentals and applications. Fuel Cells 2001, 1(1), 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larminie, J.; Dicks, A. Fuel Cell Systems Explained, 2nd ed.; Wiley, 2003; Available online: https://sv.20file.org/up1/482_0.pdf.

- Ngyuen, N.Q. Ceramic fuel cells. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1993, 76, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Ahn, D.S.; Kwon, I.H.; Ahn, H.J. Development of hydrogen-storage alloys by mechanical alloying Mg with Fe and Co. Met. Mater. Int. 1999, 5, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Ivanov, E.I.; Darriet, B.; Pezat, M.; Hagenmuller, P. Hydriding properties of a mechanically alloyed mixture with a composition Mg2Ni. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1985, 10, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/KR/ko/technical-documents/technical-article/analytical-chemistry/photometry-and-reflectometry/ir-spectrum-table. (visited on June 29, 2023).

- https://chem.libretexts.org/Ancillary_Materials/Reference/Reference_Tables/Spectroscopic_Reference_Tables/Infrared_Spectroscopy_Absorption_Table. (visited on June 29, 2023).

- Stampfer, J.F. Jr.; Holley, C.E. Jr.; Suttle, J.F. The magnesium-hydrogen system. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 3504–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Park, H.R. Pressure–composition isotherms in the Mg2Ni–H2 system. J. Alloys. Compd. 1998, 270, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.Y.; Pezat, M.; Darriet, B.; Hagenmuller, P. Hydriding mechanism of Mg2Ni in the presence of oxygen impurity in hydrogen. J. Mater. Sci. 1985, 20, 2958–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).