1. Introduction

Suicide is one of the top 20 leading causes of death worldwide, accounts for approximately 800 000 deaths annually, which is a serious public health problem [

1]

. Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death for adolescents between 15 and 19 years [

2]. Young people with suicidal behaviors often do not access mental health services or even seek professional help [

3,

4]. There are number of factors that explain this: concerns around confidentiality, fears of stigma from staff and peers, lack of knowledge of who to seek help from [

5]. However, there are a lot of barriers for young people when they try to access mental health support. Recently young people preferred getting support from online community-based services (forums, webchat, or support groups) when have suicidal behavior [

4,

6]. Possibility to stay anonymous is the most important factor that induce young people to seek help on the Internet [

7]. Furthermore, face-to-face access to psychological and psychiatric services has been hampered by the pandemic outbreak. Due to the COVID-19, cases of suicide have been reported in many countries affected by the pandemic. Infected patients, healthcare providers including those directly engaged to the treatment of patients with SARS-Cov-2; employees of industries affected by the economic crisis, the whole families of deceased are at risk of committing suicide. Apart from psychosocial stressors, individuals with psychiatric disorders and suicide behaviors before pandemic started are in the high risk of suicide attempts (SA). The COVID-19 pandemic started spreading in November 2019 in Wuhan China. The first case of SARS-Cov-2 infection in Poland was found on March 4, 2020. The fear of being infected as well as restrictions applied to limit infection's spreading have had a negative impact on family life and human relationships. All of these factors caused anxiety and distress to the children and their families. This study aimed to examine prospective differences in admission rates to the Department of Orthopedic Surgery Children's Trauma Center after SA in the interval of 4 years covering the peripandemic period.

2. Material and Methods

We have used the STROBE protocol designed for retrospective observational studies [

8].

To compare the number of patients treated for injuries following suicide attempts, we retrospectively searched the medical database of patients treated at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery Children's Trauma Center at two-time intervals. Two equal time frames covering the 24-month period before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed. We assumed March 4, 2020, as the cut-off date, when the first case of infection in Poland was detected.

The Department of Orthopedic Surgery medical database was searched in two separate time frames. The initial search revealed 1151 patients hospitalized in the 24 months before March 4, 2020, and 1269 patients at the same time after that date. In April 2020, only six patients were admitted to the Department due to the sanitary regime and home isolation. For the obtained data, search criteria for external causes of morbidity and mortality have been established following the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ICD-10: X60-X84 (intentional self-harm). Search queries used were: [X80 - Intentional self-harm by jumping from a high place; X81- Intentional self-harm by jumping or lying before moving object; X82 - Intentional self-harm by crashing of a motor vehicle; X83 - Intentional self-harm by other specified means; X84 - Intentional self-harm by unspecified means]. Four records were obtained in the pre-COVID-19 and ten in the post-COVID-19 period. It is worth highlighting that we did not specify the search criteria for the underlying disease diagnosis. We searched for all patients with an intentional self-harm history. Under the above criteria, the data were additionally analyzed in terms of the history of previous suicide attempts: [Y87.0 - Sequelae of intentional self-harm; Z91.5 - Personal history of self-harm]. The documentation of 14 patients has been subjected to a thorough investigation by two authors (Ł.W and M.D). The medical records were studied individually in detail, including ambulance reports from the scene of the accident with a description of the circumstances of the injury, psychological and psychiatric consultations that the patients underwent during their hospital stay, previous psychiatric treatment history, and specialist orthopedic procedures. The mental health part of suicide was initially explored and documented on a rigorous protocol by a psychiatry consultant with experience working with juvenile patients. The study's authors, in close cooperation with the consulting psychiatrist, carried out a retrospective analysis of medical documentation. Due to the multi-source nature of the verified data, we have minimized any doubts regarding the suicide attempt.

We analyzed gender, age, trauma mechanism, sustained injuries, medical procedures, length of hospitalization and history of mental disorders.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Pearson's correlation coefficients, Kruskal Wallis test and Dun's test were used for the statistical analysis. That tests are belonging to multivariate data analysis methods, because its concern the comparison of more than two groups [

9]

. For significant Kruskal Wallis analysis, i.e., p<0.05, Dun's post-hoc test was used. All tests were calculated at a statistical significance level of alpha = 0.05.

All procedures in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For the study ethical approval was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Silesian Medical Chamber in Katowice, Poland (ŚIL.KB.1134.2022) due to the retrospective nature of the study.

3. Results

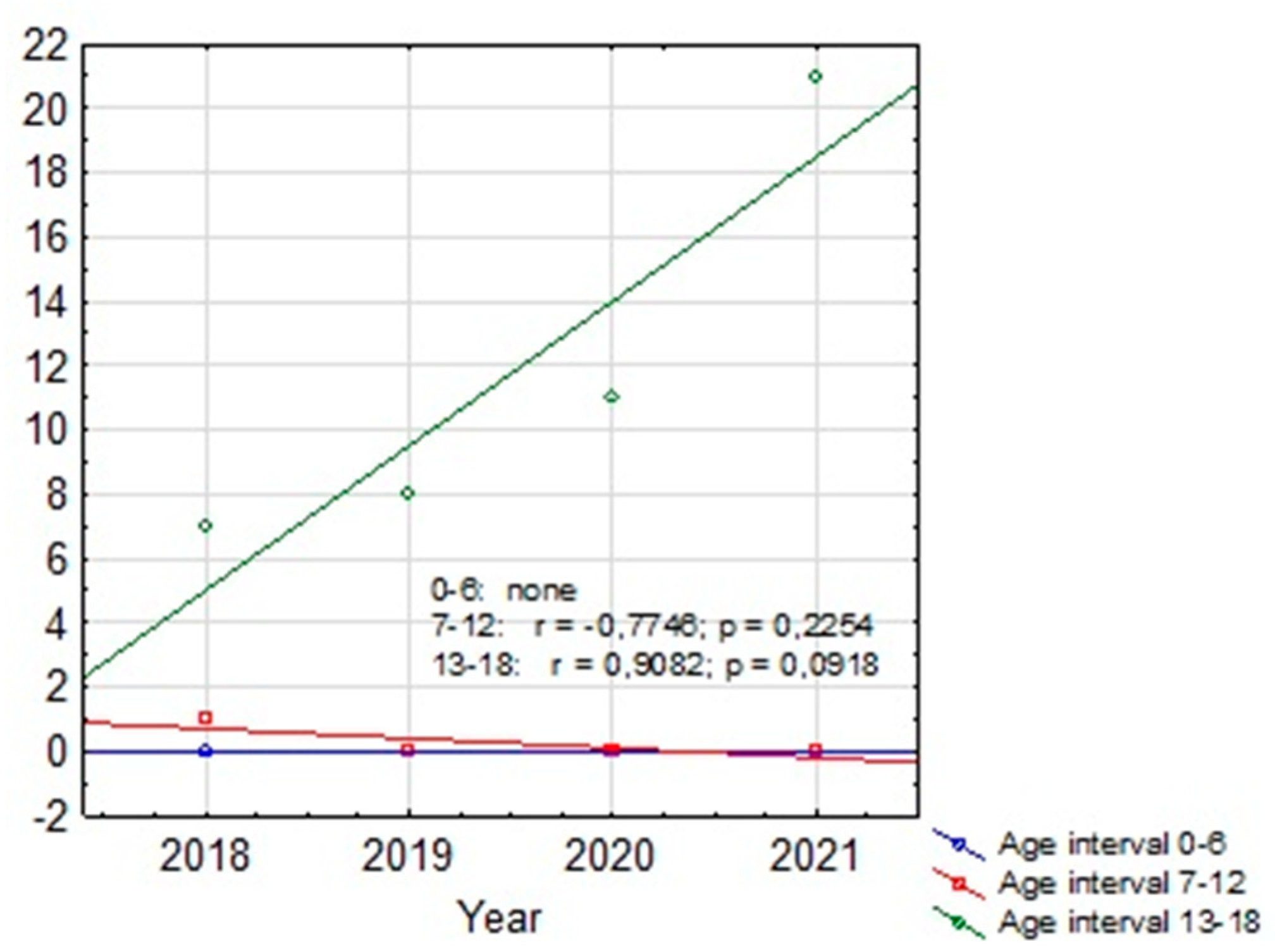

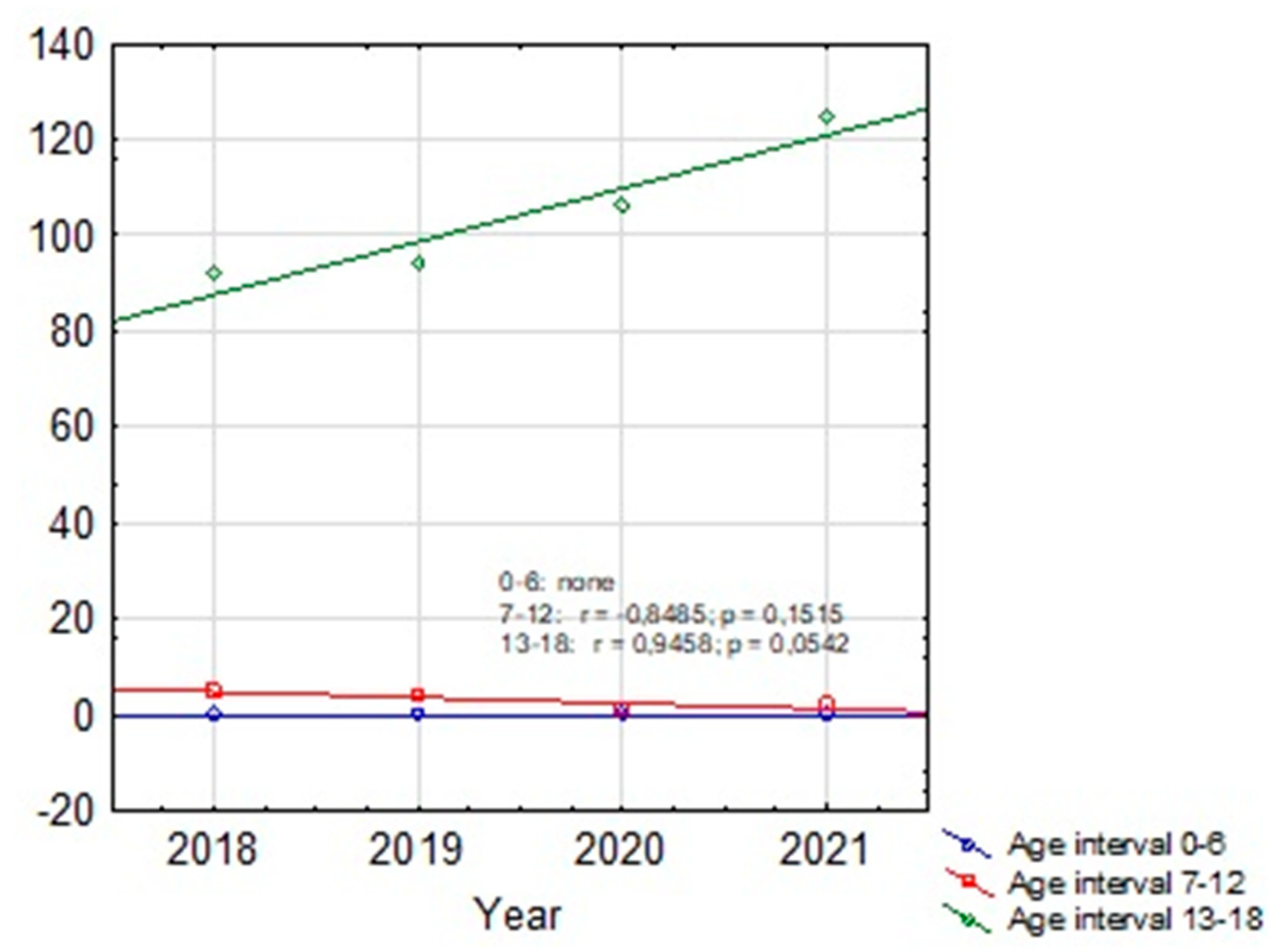

Based on our retrospective review we found 4 patients treated in our department before the pandemic period and 10 patients treated during COVID-19. The group before SARS-Cov-2 era consisted of three girls and one boy with a mean age of 14.97 (12.7-17.6). The group treated in the pandemic crisis consisted of 8 boys and 2 girls, the mean age was 15.49 (10.8-17.2). In the pre-COVID-19 group, 2 out of 4 patients had received psychiatric treatment before, but none had attempted suicide before. In the COVID-19 group, 6 out of 10 patients had previously received psychiatric treatment, moreover 3 of them attempted suicide before. In 3 patients treated in a pandemic, the suicide attempt was the first manifestation of mental problems, none of these patients received psychiatric help before. The mean hospital stay in both groups was similar and amounted 17.75 days (11-27) for the group before and 16.2 days (3-31) for the group after COVID-19, respectively. The most common SA in the group before COVID-19 was a jump from height. Among the group of patients after COVID-19, we observed 6 jumps from height, one deliberate motor vehicle accident, two throws under the car and one under the train. According to the police records in the last four years no case of fatal SA was found among the 0-6 y.o. group. There was also no increase in SA in the 7-12 y.o. group (only one case in 2018). In 12-18 y.o. interval for the whole country there was an increase of fatal SA (respectively: 2018 - 92 SA; 2019 - 94 SA; 2020 - 106 SA; 2021 - 125 SA). The same tendency was observed for the Silesian Voivodeship (respectively: 2018 - 7 SA; 2019 - 8 SA; 2020 - 11 SA; 2021 - 21 SA). Details are presented in

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for children with SA before and during the pandemic based on the U Mann Whitney statistic for different groups are shown in

Table 4.

Figure 1 and

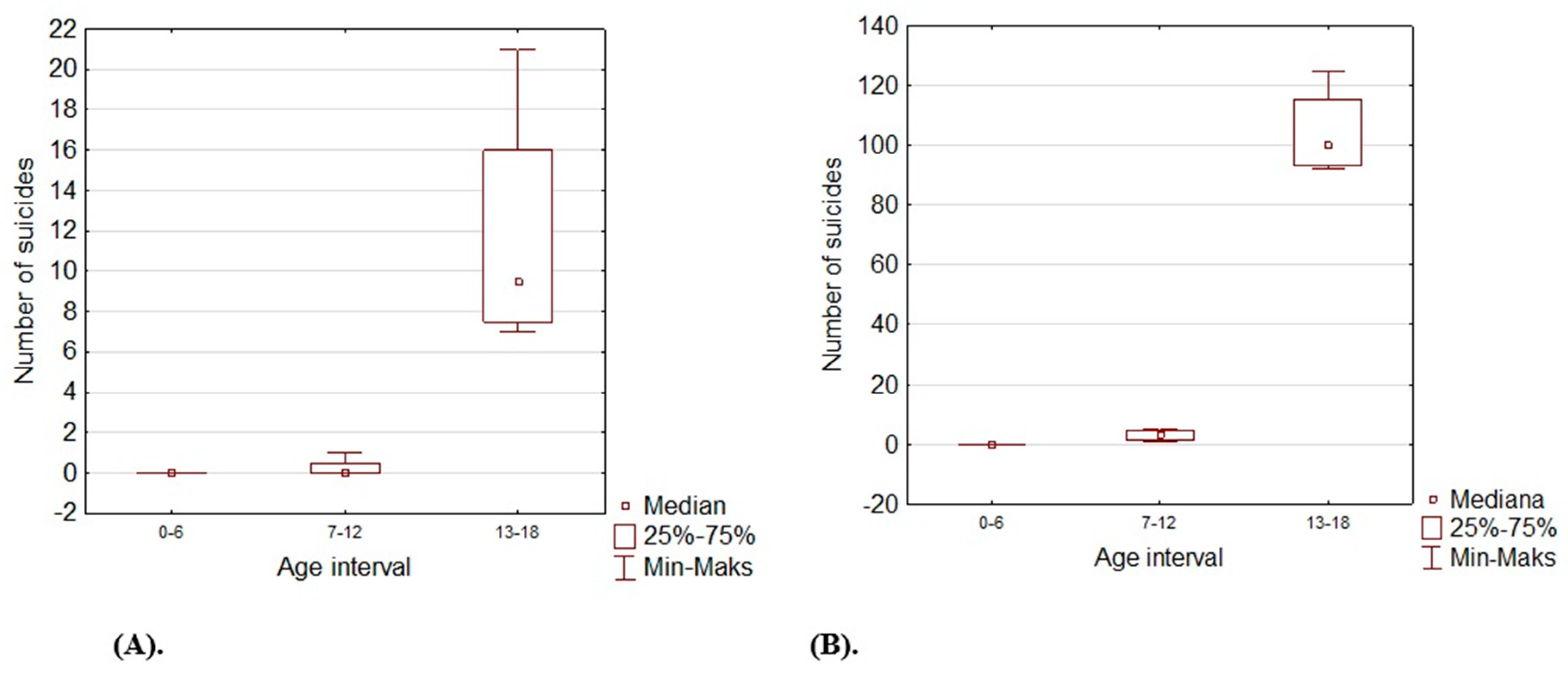

Figure 2 show trends in the number of suicides by age groups. Although for the 13-18 age group those trends are not statistically significant (p>0.05), we can conclude that at this age the number of suicides increases. Based on the Kruskal Wallis test and the Dun post hoc test, it can be stated that between 2018 and 2021 the largest number of suicides concerned the 13-18 y.o. group, both for the Silesian Voivodeship (H=9.374; p=0.0092) and for the entire country (H= 10.203; p=0.0061). The results are shown on box and whisker chart;

Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Table 1.

Patients treated before the COVID-19 pandemic. CRIF-closed reduction with internal fixation; CREF-closed reduction with external fixation; ORIF -open reduction with internal fixation; NA - not available.

Table 1.

Patients treated before the COVID-19 pandemic. CRIF-closed reduction with internal fixation; CREF-closed reduction with external fixation; ORIF -open reduction with internal fixation; NA - not available.

| No |

Sex / age. |

Sustained injuries. |

Medical procedures. |

Hospital stay. |

Injury mechanism. |

Previous mental disorders. |

| 1. |

Girl / 12.7 |

Multiple unstable pelvic fracture; middle shaft fractures of the right radius and ulna; psychoorganic syndrome after traumatic encephalitis. |

CRIF / anterior external fixation of pelvic ring; CRIF / FIN stabilization of radius and ulna fractures |

27 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Negative history of mental disorders and suicide attempts. |

| 2. |

Girl / 12.9 |

Fracture of Th12 type A1 AO;

left medial and lateral malleoli fractures. |

ORIF / screws, K-wires stabilization of malleoli fractures; Jewett brace. |

11 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Psychiatric medications /NA/.

Negative history of suicide attempts.

Self-harming. |

| 3. |

Boy / 17.6 |

Fracture of L1 B2, N0, M1 AO type; contusion of L4 and L5; right V metatarsal bone avulsion fracture; abdomen contusions. |

Percutaneous transpedicular Th12-L2 fixation. |

20 days. |

NA |

NA |

| 4. |

Girl / 16.7 |

Bilateral lung contusion; bilateral pneumothorax, fracture of the sacrum, open left humeral shaft with radial nerve laceration fracture of the left humerus. |

Left pleural drainage; ORIF / plate fixation of humeral shaft fracture with radial nerve reconstruction (sural cable grafts). |

13 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Mood disturbances.

Negative history of suicide attempts. |

Table 2.

Patients treated in the COVID-19 pandemic. CRIF -closed reduction with internal fixation; CREF-closed reduction with external fixation; ORIF -open reduction with internal fixation; ICU - Intensive Care Unit; NA - not available.

Table 2.

Patients treated in the COVID-19 pandemic. CRIF -closed reduction with internal fixation; CREF-closed reduction with external fixation; ORIF -open reduction with internal fixation; ICU - Intensive Care Unit; NA - not available.

| No |

Sex / age. |

Sustained injuries. |

Orthopaedic procedures. |

Hospital stay. |

Injury mechanism. |

Previous mental disorders. |

| 1. |

Boy / 17.1 |

Unstable fracture of Th8 and Th9 type C; N4; stable C6 fracture type O according to AO; multiple ribs fractures, bilateral pneumothorax, contusion of the right lung; cerebral hematoma, distal phsysis fracture of the left radius. |

Transpedicular stabilization of Th6 -Th7 / Th10-Th11; laminectomy; right pleural drainage; CRIF of distal phsysis fracture of the left radius – Kwire fixation. |

14 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Depression / Pharmacotherapy with sertraline.

Appetite disturbances.

Self-harming.

History of suicide attempts (5x). |

| 2. |

Boy / 16.5 |

Left femoral shaft fracture; multiple left ribs fractures, left pneumothorax; multiple wounds and abrasions |

ORIF / plate fixation of left femoral shaft fracture. |

11 days. |

Deliberate motor vehicle accident. |

History of suicide attempts (1x). |

| 3. |

Boy / 15.5 |

Multifragmentary burst fracture of the right calcaneus; open fracture of left tibia; III, IV, V left metatarsal fractures. |

ORIF - open left tibia fracture; CRIF - III, IV, V left metatarsal fractures. |

20 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Negative history of mental disorders and suicide attempts. |

| 4. |

Girl / 15.1 |

Multiple pelvic fractures; proximal physis fracture of right humerus / SH type 2; brain concussion; multiple wounds and abrasions |

CRIF / K-wire stabilization of proximal humerus fracture; wounds suturing. |

22 days. |

Throw under the car. |

Depression / psychotherapy.

Self-harming.

Negative history of suicide attempts. |

| 5. |

Boy / 16.1 |

Stable fracture of Th6; bilateral pneumothorax, bilateral lung contusion; spleen contusion; left humeral shaft fracture; bilateral forearm shafts fractures; walls of the right eye socket fractures |

CRIF /FIN stabilization of left humerus; CRIF / K-wires stabilization of right radius fracture; Jewett TLSO. |

10 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Negative history of mental disorders and suicide attempts. |

| 6. |

Girl / 16.3 |

Extensive right trochanteric region wound, damage to the gluteal muscles; open multifragmentary fracture of right tibia and fibula in distal third - type 2 according to GA; multiple pelvic fractures; multiple wounds and abrasions |

ORIF / plate fixation of right tibia fracture; suturing the traumatic wound of the right hip; numerous surgical debridement and focal necrosectomy of the right trochanteric area wound. |

31 days. |

Throw under the train. |

Mood disturbances.

History of alcohol and cigarettes addiction.

Self-harming.

History of suicide attempts (1x). |

| 7. |

Boy / 17.1 |

Bilateral open fractures of femoral shaft in distal thirds- type 2 GA; bilateral patella fractures with no displacement; medial condyle fracture of the right tibia with no displacement.

nasal bone fractures; brain concussion |

ORIF / external fixation of open femoral fractures; wounds debridement and suturing. |

10 days. |

Throw under the car. |

Depression / bipolar disorder. Pharmacotherapy with fluoxetine, sulpiride, lithium.

Self-harming (1x).

Negative history of suicide attempts. |

| 8. |

Boy / 17.2 |

Multiple, unstable pelvic fractures; multifragmentary articular fracture of the left distal humerus; multifragmentary fracture of the proximal ulna with a bone lost. |

CRIF / anterior external fixation of pelvic ring; ORIF / plate, screws, Weber tension wire of left humeral and ulnar fractures. |

28 days. |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Negative history of mental disorders and suicide attempts. |

| 9. |

Boy / 10.8 |

Bilateral pneumothorax, bilateral lung contusion; open fracture of the distal right radius and ulna- type 1 GA; distal left radius fracture. |

ORIF / K-wires stabilization distal right radius and ulna fracture |

1-day ICU

2 days |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Negative history of mental disorders and suicide attempts. |

| 10. |

Boy / 13.2 |

Severe cardiovascular and respiratory failure; brain contusion and oedema; multiple vertebrae fracture C2,C4,Th9-L5; multiple ribs fractures, bilateral tension pneumothorax, bilateral lung contusion; right femoral neck fracture; bilateral humeral shaft fractures; multiple pelvic fractures.

DEATH |

CRIF / anterior external fixation of pelvic ring; direct right tibia traction. |

13 days

ICU |

Deliberate jump from high. |

Positive psychiatric history (lack of data).

Negative history of suicide attempts. |

Table 3.

Police statistics with the number of fatal suicides for whole country and the silesian province.

Table 3.

Police statistics with the number of fatal suicides for whole country and the silesian province.

| Year. |

Region. |

Number of fatal suicide attempts. |

Age interval |

Age interval |

Age interval |

| '0-6' |

'7-12' |

'13-18' |

| 2017 |

Silesian Voivodeship. |

601 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

| 2017 |

Poland. |

5276 |

0 |

1 |

115 |

| 2018 |

Silesian Voivodeship. |

596 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

| 2018 |

Poland. |

5182 |

0 |

5 |

92 |

| 2019 |

Silesian Voivodeship. |

548 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

| 2019 |

Poland. |

5255 |

0 |

4 |

94 |

| 2020 |

Silesian Voivodeship. |

562 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

| 2020 |

Poland. |

5165 |

0 |

1 |

106 |

| 2021 |

Silesian Voivodeship. |

582 |

0 |

0 |

21 |

| 2021 |

Polska |

5201 |

0 |

2 |

125 |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for children with suicide attempts before and during the pandemic with a test of differences between the above-mentioned U Man Whitney groups. U Mann-Whitney statistic Z=-0.071; p=0.944.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for children with suicide attempts before and during the pandemic with a test of differences between the above-mentioned U Man Whitney groups. U Mann-Whitney statistic Z=-0.071; p=0.944.

| |

Mean. |

Standard deviation. |

Median. |

Confidence

-95% |

Confidence

+95% |

Minimum. |

Maximum. |

| Patients treated before the COVID-19 pandemic |

14,98 |

2,54 |

14,80 |

10,93 |

19,02 |

12,70 |

17,60 |

| Patients treated in the COVID-19 pandemic |

15,49 |

2,04 |

16,20 |

14,03 |

16,95 |

10,80 |

17,20 |

4. Discussion

From the perspective of Children's Trauma Center exclusively, this paper examines whether the number of suicides in children and adolescents have raised over the past years. We decided to evaluate the SA because we believe that the number of suicides in children is one of the strongest factors which measures young people mental health condition. Based on our analysis, the frequency of SA among children has raised. Although this increase is not statistically significant (p>0.05), the growing trend is undoubtedly alarming. In the last four years at the Children's Orthopedic Department, we have treated 14 patients after serious SA. The reason for this enlargement is undoubtedly multifactorial, but the pandemic's contribution could have a substantial impact because the COVID-19 could affect immature populations in multiple fields. Before COVID-19, we have treated 4 patients and after COVID-19, 10 patients which is a more than twofold increase at the same time intervals. 4.45 million people live in the Silesian Voivodeship, which is 12.14% of the country's population. Our hospital is the only Children's Trauma Center in the Silesian Voivodeship, which makes us a representative unit. A trauma center with an emergency department cares for immature patients suffering from injuries from the city of Katowice, the capital of the voivodeship, and the neighboring towns. Through a helipad for receiving patients who have been airlifted to the center from the Silesian region and highly specialized departments with a full range of specialists, the hospital provides professional multidisciplinary care for patients suffering major trauma. We compared our results with the Polish police suicide statistics additionally. We have isolated the number of fatal SA separately for the entire country and for the Silesian Voivodeship. According to the police records in the last four years among children between 12 and 18 y.o. for the whole country there was an increase of SA (92 cases in 2018 compared to 125 cases in 2021). The same tendency was observed for the Silesian Voivodeship (7 cases in 2018 compared to - 21 cases in 2021). In our study only one patient was younger than 12, others were in the 12-18 years interval. Based on the other authors reports, female adolescents have a higher risk of mental disorder, but those studies did not include suicidal behavior [

10,

11,

12]. In our group, we observed a predominance of girls taking SA before SARS-Cov-2 era (three girls and one boy) but a definite prevalence of boys in the pandemic crisis (eight boys and only two girls). The pandemic’s physical restrictions and social distancing measures have affected each domain of life. Anxiety, depression, sleep and appetite disturbances, as well as impairment in social interactions are the most common symptoms despite the patient age. The suicide rate in children and adolescents in the last two decades was stable, in contrast to the downward trend in adults [

13]. Although data from the Swiss National Cohort have shown increasing suicide rate with age: 0 per 100,000 at age 10 years to 14.8 per 100,000 boys and 5.4 per 100,000 girls at 18 years [

14]. Isumi A et al reported that first wave of the COVID-19 has not significantly affected suicide rates among children and adolescents [

15]. Based on real-time suicide data from multiple countries including Poland, Pirkis et al. relying on an interrupted time-series analysis reported no significant increase in risk of suicide during the pandemics in any country [

16]. However, mentioned study did not stratified data by age or gender. Yoshioka E et al. examined the impact of the pandemic on suicide by gender and age through December 2021 in Japan and did not find statistically significant results of the impact of the pandemic on suicide rates for men and women under 20 years old [

17]. Our results could differ from literature reports, probably because our study was limited to patients treated at the Children's Orthopedic Department exclusively. Interestingly, our observation coincides with the Bruns N et al. reports [

18]. Based on a retrospective multicenter study among 37 pediatric intensive care units they found that SA increased in adolescent boys (standardized morbidity rate: 1.38) but decreased in adolescent girls (standardized morbidity rate: 0.56).

4.1. Initiators of Suicide Risk

The main initiators which increase the risk for suicide and suicidal behaviors in children and adolescents can be divided to

school factors - bullying, peer relationships, violent school habitat;

family factors - family dysfunction, conflicts, poor communication, and

individual psychological factors - depression and other mental health disorders [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The children reaction for the major stress depends also upon many things including physical and mental health, the socioeconomic family status, cultural environment and experience with previous emergency situations [

25,

26]. What's interesting, in the study caried with the help of United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) based on 1700 children and adolescents from 104 countries they reported that high levels of stress, affect children brain development with long-term consequences [

26].

4.2. School Closure as a Stressor Related to COVID-19

School closure was a crucial change during the COVID-19 that directly hit young people. Children were unable to meet with friends and teachers, moreover they could not participate in school and out-of-school activities. Staying long-hours at home could affect children in both, positive and negative way. Children may get a reprieve from problems at school: e.g., bullying, negative rivalry, exam stress, peer conflict, romantic breakups, stress related to sexual orientation or on the other hand feel distressed from relationships with family members: i.e., family physical and/or sexual violence, parental alcohol addiction [

27,

28]. The pandemic affected children by changing the relationship with their parents, who may be also positively or negatively affected by the pandemic. Increased stress might cause deterioration of parent-child relationships or in opposite parents could support their children while working from home [

29,

30]. Another danger of social isolation involving a significant increase in the number of hours that young people spend online and on social media should be pointed out. There are many proofs that internet overuse can lead to behavioral problems, decrease real-life social interactions, cause relationship disorders and mood dysfunction [

31,

32]

. This may correspond with increased risk of suicide, especially in children with pre-existing psychiatric problems.

5. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Small study and quite homogenic, narrow population of patients being treated at Children's Orthopedic Department.

6. Conclusions

The results of our study, as reported by other authors, indicate that the pandemic may have caused a wide range of negative mental health consequences for young individuals. We found a critical gap in the literature concerning injuries after suicide attempts among children and adolescents, however it requires a lot of attention from the whole medical staff. Medical health providers including orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of rising suicide rates among adolescents. Multi-center study should be considered to assess increasing rate of suicide rate among immature population. The effort should be put to find effective strategies to promote positive mental health during pandemics crisis in order to reduce suicide rate and suicidal behaviors.

Author Contributions

Ł.W. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Ł.W. collected data. Ł.W and M.D. conducted the data analysis. Ł.W. prepared the final version of the manuscript. Ł.W and M.D. Ł.W. M.D. and R.T. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was not funded. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. For the study ethical approval was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Silesian Medical Chamber in Katowice, Poland (ŚIL.KB.1134.2022) due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Improving the Mental and Brain Health of Children and Adolescents. 2020. Available online: https://www.who. Int/activities/improving-the-mental-and-brain-health-of-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- World Health Organisation. Suicide [Fact Sheet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Geulayov, G.; Casey, D.; McDonald, K.C.; Foster, P.; Pritchard, K.; Wells, C.; Clements, C.; Kapur, N.; Ness, J.; Waters, K.; et al. Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal self-harm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): a retrospective study. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelmore, L.; Hindley, P. Help-Seeking for Suicidal Thoughts and Self-Harm in Young People: A Systematic Review. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2012, 42, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.J.; Kloess, J.A.; Gill, C.; Michail, M. Assessing and Responding to Suicide Risk in Children and Young People: Understanding Views and Experiences of Helpline Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 10887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.J.; Nielsen, E.; Coulson, N.S. “They aren’t all like that”: Perceptions of clinical services, as told by self-harm online communities. J. Health Psychol. 2018;25:2164–2177. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, P.; Bambling, M.; Sheffield, J.; Edirippulige, S. Exploring Young People’s Perceptions of the Effectiveness of Text-Based Online Counseling: Mixed Methods Pilot Study. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2019, 6, e13152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolski, M.; Beza, M. Modification of the Principal Component Analysis Method Based on Feature Rotation by Class Centroids. JUCS - J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2022, 28, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, W.E.; Dumas, T.M.; Forbes, L.M. Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Behav. Sci. / Rev. Can. des Sci. du Comport. 2020, 52, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-J.; Zhang, L.-G.; Wang, L.-L.; Guo, Z.-C.; Wang, J.-Q.; Chen, J.-C.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.-X. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, U.; Ring, M.; Frei, A.; Rössler, W.; Schnyder, U.; Ajdacic-Gross, V. Suicide trends diverge by method: Swiss suicide rates 1969–2005. Eur. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steck, N.; Cohort, F.T.S.N.; Egger, M.; Schimmelmann, B.G.; Kupferschmid, S. Suicide in adolescents: findings from the Swiss National cohort. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 27, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isumi, A.; Doi, S.; Yamaoka, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Fujiwara, T. Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; John, A.; Shin, S.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Analuisa-Aguilar, P.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Bantjes, J.; Baran, A.; et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, E.; Hanley, S.J.; Sato, Y.; Saijo, Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates in Japan through December 2021: An interrupted time series analysis. Lancet Reg. Heal. - West. Pac. 2022, 24, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruns N, Willemsen LY, Holtkamp K, Kamp O, Dudda M, Kowall B, Stang A, Hey F, Blankenburg J, Sabir H, Eifinger F, Fuchs H, Haase R, Andrée C, Heldmann M, Potratz J, Kurz D, Schumann A, Müller-Knapp M, Mand N, Doerfel C, Dahlem P, Rothoeft T, Ohlert M, Silkenbäumer K, Dohle F, Indraswari F, Niemann F, Jahn P, Merker M, Braun N, Brevis Nunez F, Engler M, Heimann K, Wolf GK, Wulf D, Hankel S, Freymann H, Allgaier N, Knirsch F, Dercks M, Reinhard J, Hoppenz M, Felderhoff-Müser U, Dohna-Schwake C. Impact of the First COVID Lockdown on Accident- and Injury-Related Pediatric Intensive Care Admissions in Germany-A Multicenter Study. Children (Basel). 2022;9(3):363. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Robledillo, N.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Albaladejo-Blázquez, N.; Sánchez-SanSegundo, M. Family and School Contexts as Predictors of Suicidal Behavior among Adolescents: The Role of Depression and Anxiety. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Zappino, J. Suicide among children and adolescents: a review. Actas espanolas de Psiquiatr. 2014, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J.F.; Goldstein, S.E.; Gager, C.T. A longitudinal examination of social connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adolescents. Child Adolesc. Ment. Heal. 2018, 23, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVille, D.C.; Whalen, D.; Breslin, F.J.; Morris, A.S.; Khalsa, S.S.; Paulus, M.P.; Barch, D.M. Prevalence and Family-Related Factors Associated With Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Attempts, and Self-injury in Children Aged 9 to 10 Years. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1920956–e1920956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, J.J.; Llorente, C.; Kehrmann, L.; Flamarique, I.; Zuddas, A.; Purper-Ouakil, D.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Coghill, D.; Schulze, U.M.E.; Dittmann, R.W.; et al. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 29, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilillo, D.; Mauri, S.; Mantegazza, C.; Fabiano, V.; Mameli, C.; Zuccotti, G.V. Suicide in pediatrics: epidemiology, risk factors, warning signs and the role of the pediatrician in detecting them. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2015, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Smith, L.E.; Webster, R.K.; Weston, D.; Woodland, L.; Hall, I.; Rubin, G.J. The impact of unplanned school closure on children’s social contact: rapid evidence review. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, J.G.; Campione-Barr, N.; Metzger, A. Adolescent Development in Interpersonal and Societal Contexts. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, P.J. Suicidality in children and adolescents: lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 crisis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klasen, F.; Otto, C.; Kriston, L.; Patalay, P.; Schlack, R.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; The BELLA study group. Risk and protective factors for the development of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: results of the longitudinal BELLA study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 24, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating Effects of Parental Stress on Harsh Parenting and Parent-Child Relationship during Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. COVID-19 is Hurting Children’s Mental Health. Here’s How to Help|World Economic. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/covid-19-is-hurting-childrens-mental-health.

- Duan, L.; Shao, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Miao, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, G. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).