Submitted:

18 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

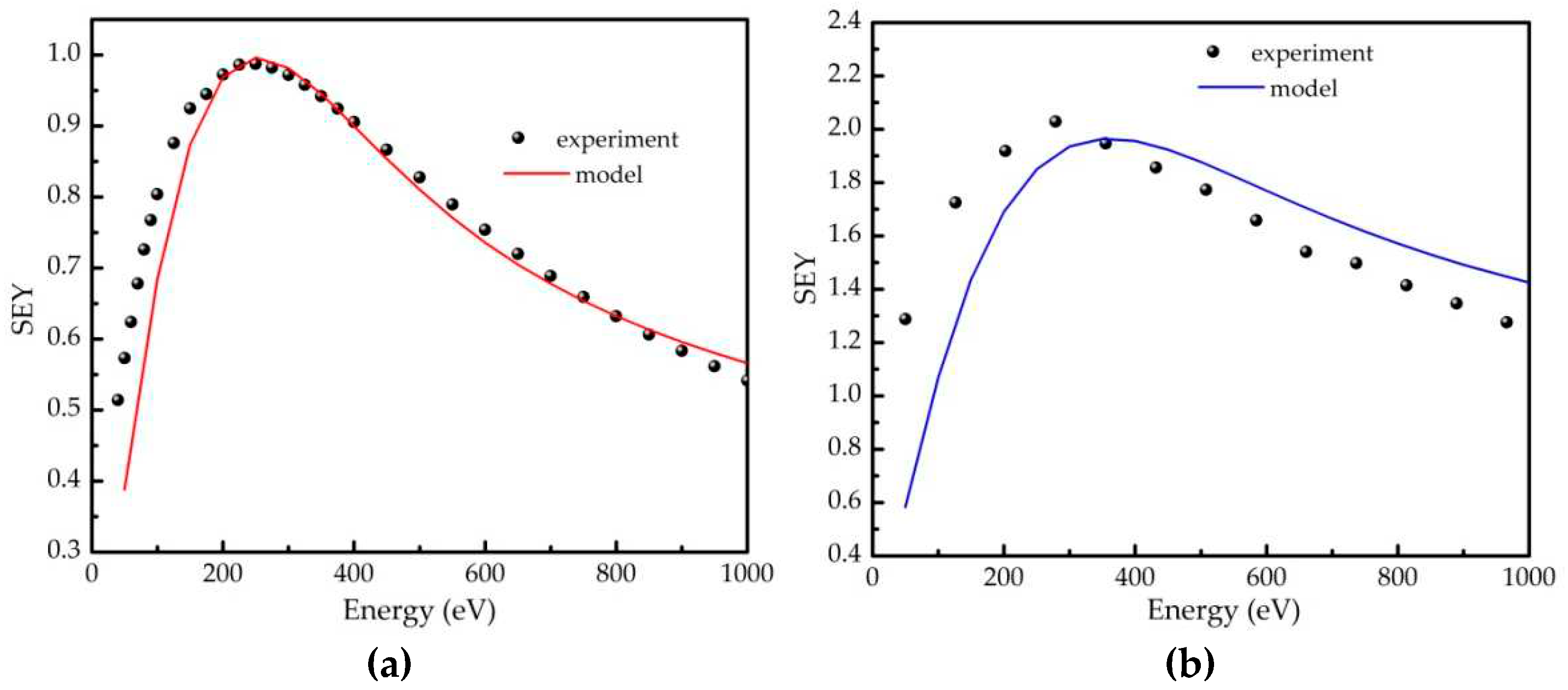

3. Results

3.1. Composition, Electron Emission and Optical Properties of the Coatings

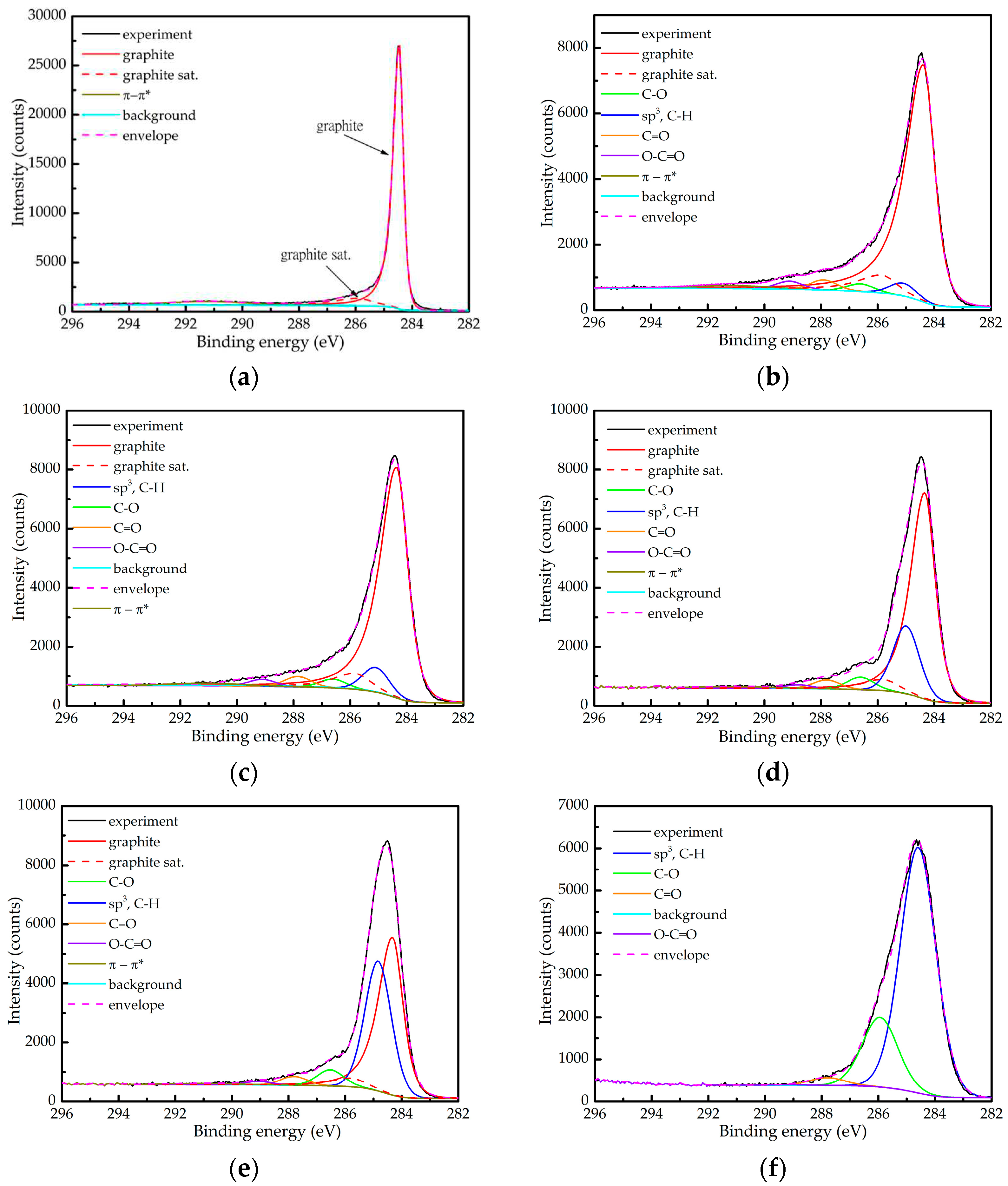

3.2. XPS Measurements

- The relative contribution of the graphitic component decreases and even disappears in the sample 10D;

- The relative contribution attributed to the sp3 carbon and the hydrocarbons increases;

- The asymmetry of the graphitic component becomes less pronounced.

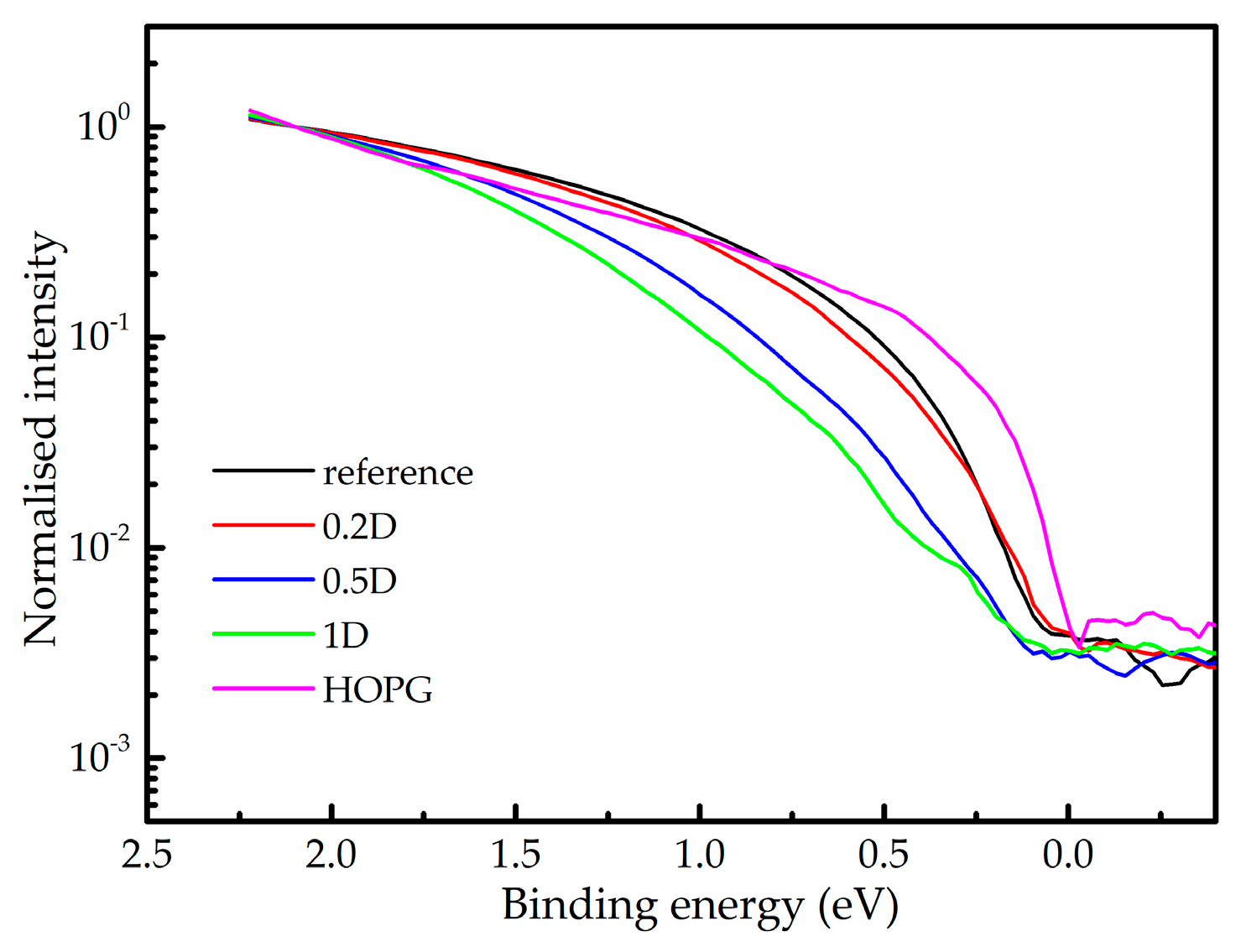

3.3. UPS Measurements

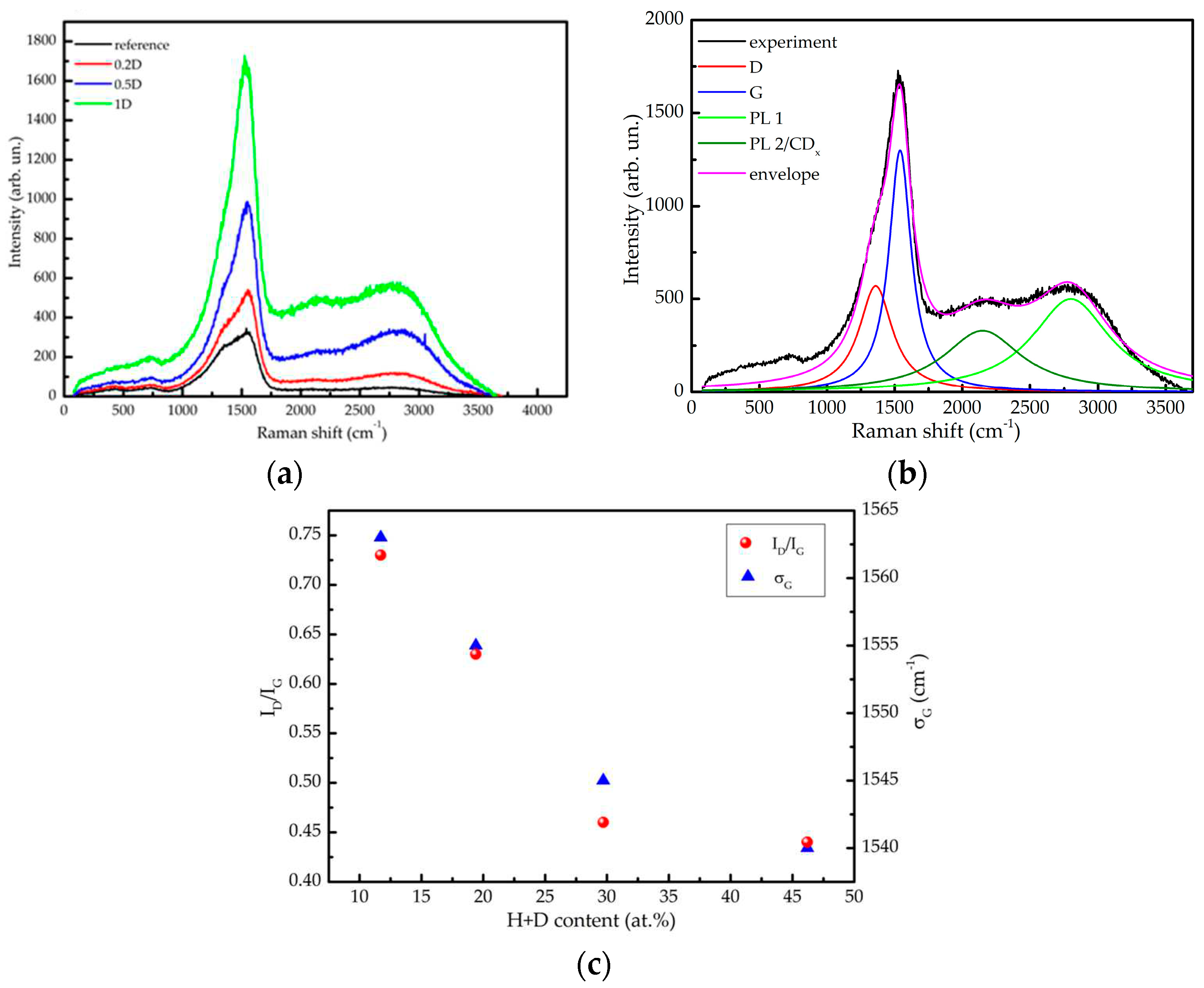

3.4. Raman Spectroscopy

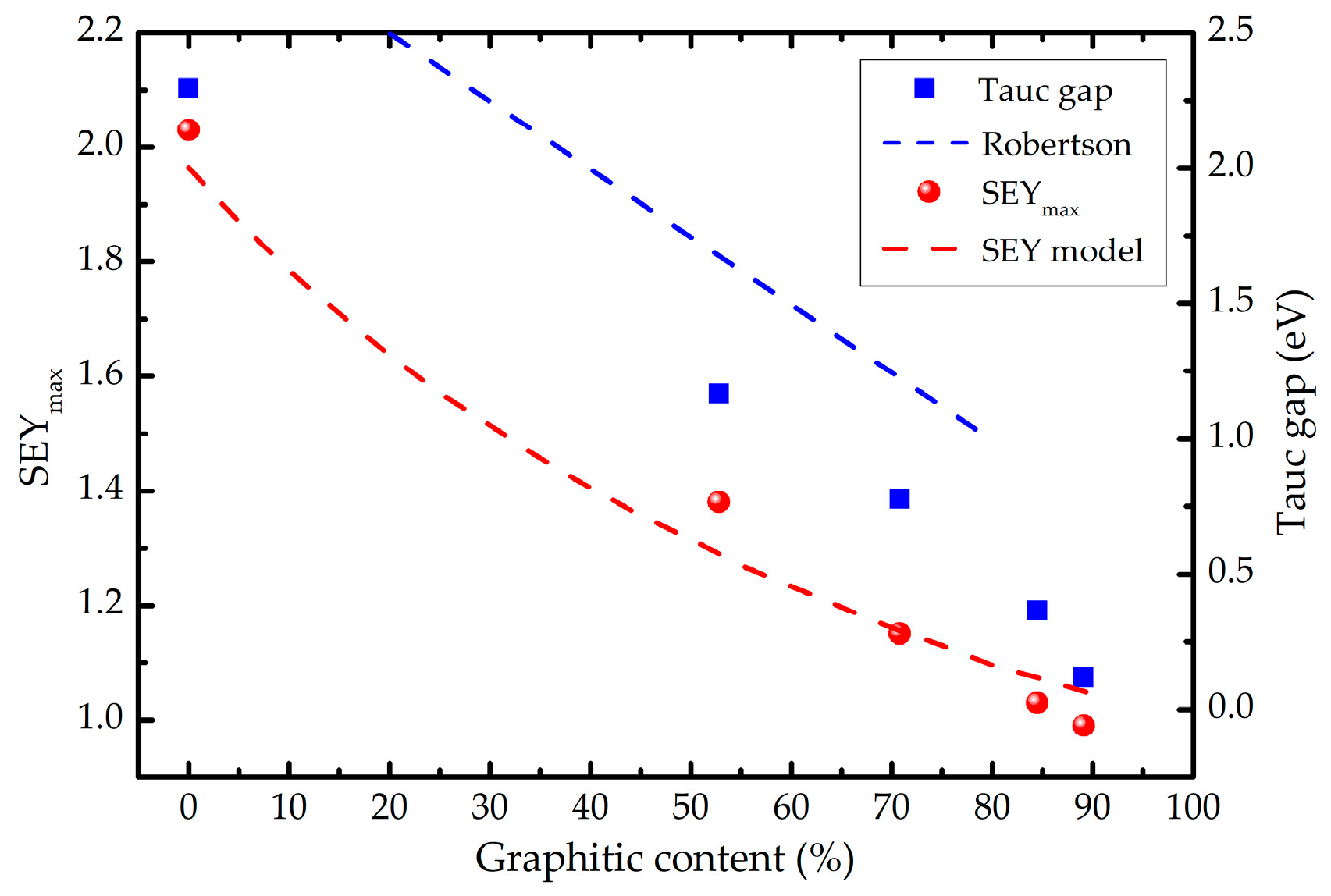

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

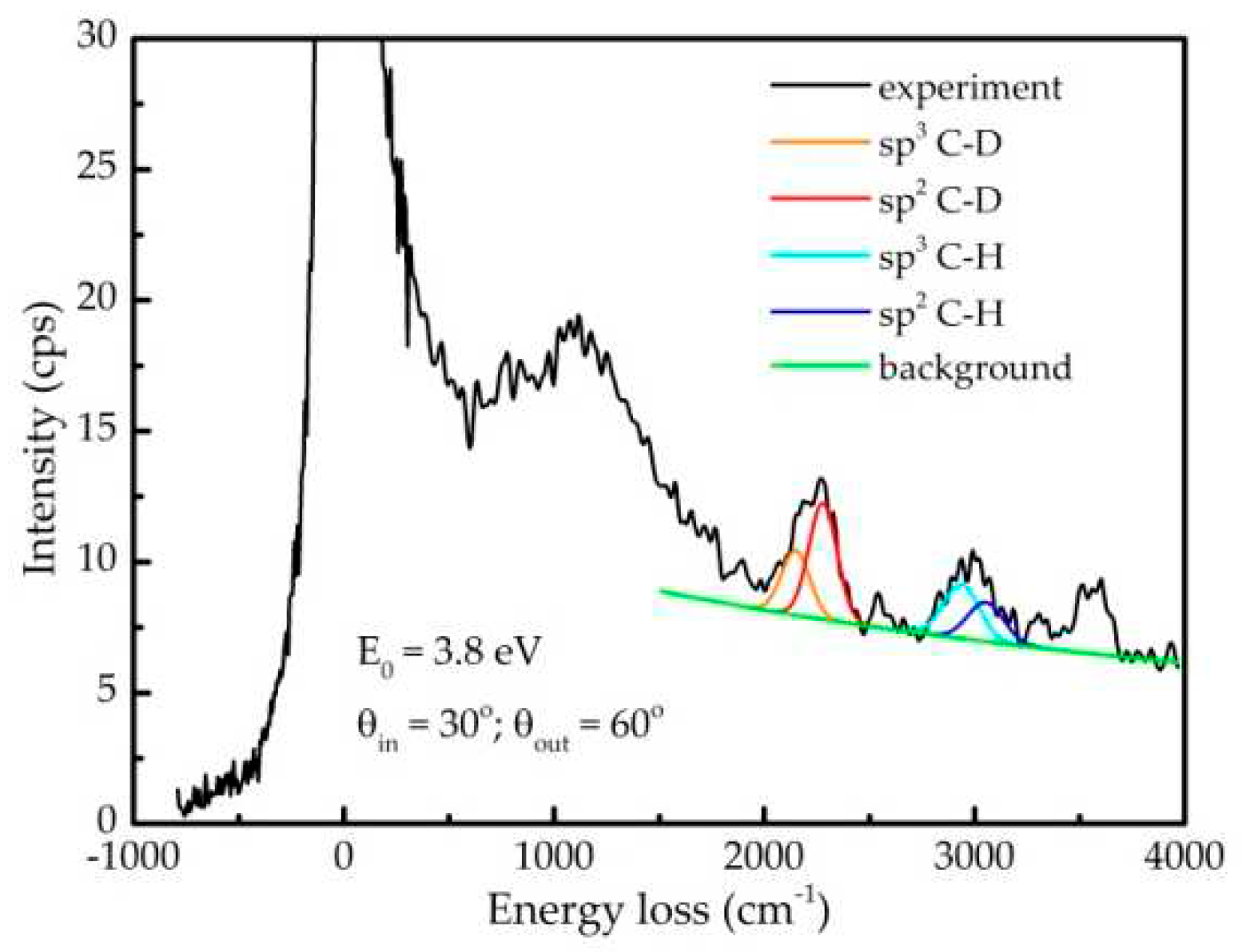

Appendix A. HREELS Measurements

A.1 Experimental Setup

A.2 Results

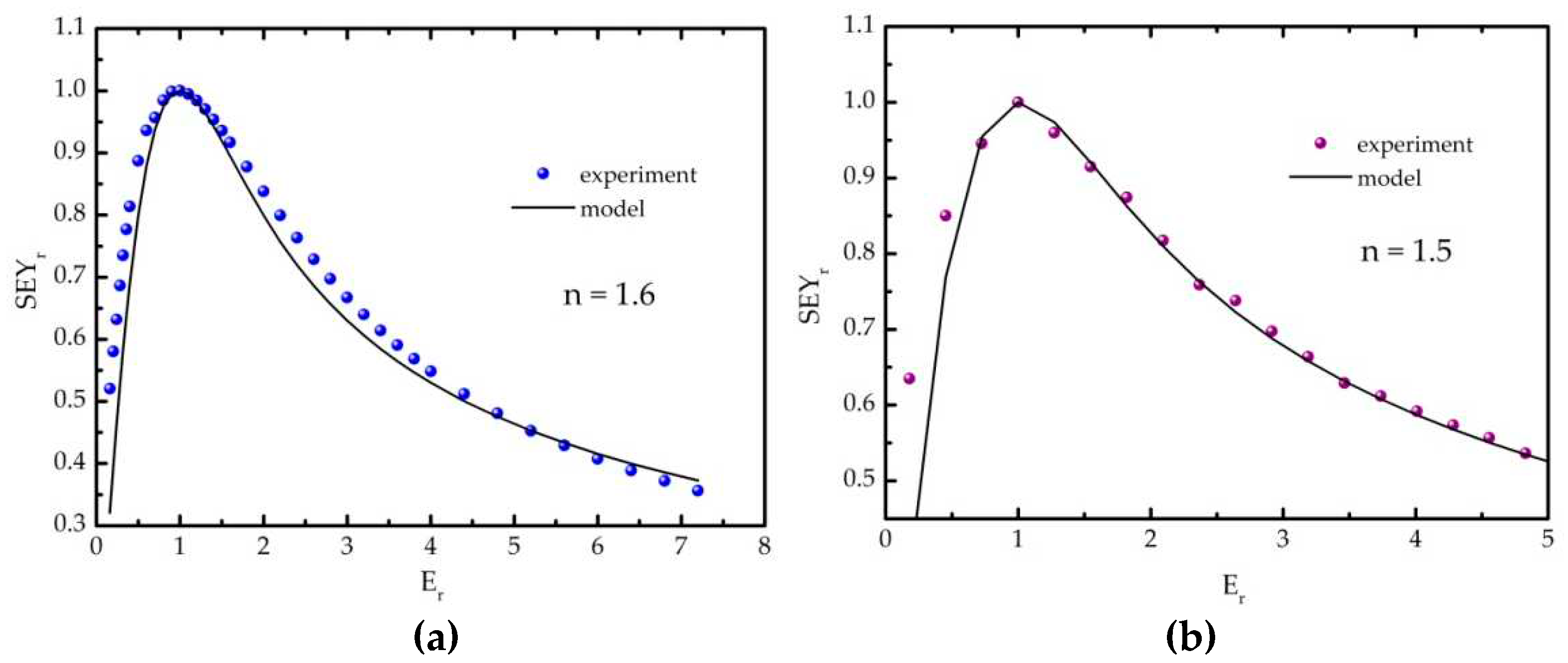

Appendix B. Modelling SEY from Non-Uniform a-Carbon Samples

B.1 Semi-Empirical Theory of Secondary Electron Emission and Its Application to Graphitic and Polymeric Samples

- all primary electrons have the same range R in a material, which can be described by the power law R = b∙En, with E being the energy of incident electrons, while b is the material constant;

- the number of internal secondary electrons generated in the depth interval (z, z + Δz) is directly proportional to the stopping power of primary electrons S(z) = -dE/dz, ΔN(z) = S(z)Δz/ε, where ε is the effective energy required to create one internal secondary electron;

- electron stopping power is assumed to be constant, and frequently its average value along the trajectory E/R(E) is used;

- the probability that an internal secondary electron will be emitted is 0.5∙exp(-z/λ), where λ is an electron escape depth (a material dependent parameter).

B.2 Model Description

References

- O. Gröbner, Bunch induced multipactoring, CM-P0064850, CERN Libraries, Geneva, Switzerland, presented at the 10th International Conference on High-Energy Accelerators, 11th-17th of July 1977, Serpukhov, USSR.

- R. Cimino, I.R. Collins, M.A. Furman, M. Pivi, F. Ruggiero, G. Rumolo, F. Zimmermann, Can low-energy electrons affect high-energy physics accelerators?, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 014801. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Kishek, Y.Y. Lau, L.K. Ang, A. Valfells, R.M. Gilgenbach, Multipactor discharge on metals and dielectrics: historical review and recent theories, Phys. Plasmas 1998, 5, 2120–2126. [CrossRef]

- J. Puech, et al., A multipactor threshold in waveguides: theory and experiment, in: J.L. Hirshfield, M.I. Petelin (Eds.), Quasi-Optical Control of Intense Microwave Transmission. NATO Science Series II: Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry vol. 203, Springer, Dordrecht, 2006.

- J. Hillairet, M. Goniche, N. Fil, M. Belhaj, and J. Puech, Multipactor in High Power Radio-Frequency Systems for Nuclear Fusion, presented at the International Workshop on Multipactor, Corona and Passive Intermodulation, MULCOPIM 2017, 5th-7th of April 2017 Noordwijk, The Netherlands.

- G. Skripka, G. Iadarola, L. Mether, G. Rumolo, Non-monotonic dependence of heat loads induced by electron cloud on bunch population at the LHC, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 849. [CrossRef]

- C. Yin Vallgren, G. Arduini, J. Bauche, S. Calatroni, P. Chiggiato, K. Cornelis, P. Costa Pinto, B. Henrist, E. Métral, H. Neupert, G. Rumolo, E. Shaposhnikova, M. Taborelli, Amorphous carbon coatings for the mitigation of electron cloud in the CERN super proton synchrotron, Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 2011, 14, 071001. [CrossRef]

- F. Willeke, J. F. Willeke, J. Beebe-Wang, Electron Ion Collider Conceptual Design Report 2021. United States: N. p., 2021. Web. [CrossRef]

- S. Verdú-Andrés et at., A beam screen to prepare the RHIC vacuum chamber for EIC hadron beams: conceptual design and requirements, 12th International Particle Accelerator Conference - IPAC’21, May 24 - 28, 2021 Web. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1784486.

- R.F. Egerton, Electron-Energy Loss Spectroscopy in the Electron Microscope 3rd edn. Springer, New York, 2011.

- S. Ono, K. Kanaya, The energy dependence of secondary emission based on the range-energy retardation power formula, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1979, 12, 619.

- P. Costa Pinto, et al., Carbon coating of the SPS dipole chambers. AIP Conf. Proc, C 2013, 12, 141–148.

- A. Santos, N. Bundaleski, B.J. Shaw, A.G. Silva, O.M.N.D. Teodoro, Increase of Secondary Electron Yield of Amorphous Carbon Coatings under High Vacuum Conditions. Vacuum 2013, 98, 37–40. [CrossRef]

- H. M. Fernández, M. Himmerlich, P. Costa Pinto, J. Coroa, D. Sousa, A. Baris, M. Taborelli, The impact of H2 and N2 on the material properties and secondary electron yield of sputtered amorphous carbon films for anti-multipacting applications, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 542, 148552. [CrossRef]

- C. F. Adame, E. Alves, N.P. Barradas, P. Costa Pinto, Y. Delaup, I.M.M. Ferreira, H. Neupert, M. Himmerlich, S. Pfeiffer, M. Rimoldi, M. Taborelli, O.M.N.D. Teodoro, N. Bundaleski, Amorphous carbon thin films: mechanisms of hydrogen incorporation during magnetron sputtering and consequences for the secondary electron emission, J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2023, 41, 043412. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Ferrari, J. Robertson, Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon, Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 14095. [CrossRef]

- D. Roy, G. F. Samub, M. K. Hossain, C. Janáky, K. Rajeshwar, On the measured optical bandgap values of inorganic oxide semiconductors for solar fuels generation, Catalysis Today 2018, 300, 136–144. [CrossRef]

- J. Robertson, Diamond-like amorphous carbon, Mat. Sci. & Engineering R 2002, 37, 129–281. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Ferrari, J. Robertson, Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon, Phys. Rev. B, 2000, 61, 14095. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, X. Wei, F. Wang, A ternary phase diagram for amorphous carbon, Carbon 2015, 94, 202–213. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaciulis, Spectroscopy of carbon: from diamond to nitride films, Surf. Interface Anal. 2012, 44, 1155–1161. [CrossRef]

- P. Mérel, M. Tabbal, M. Chaker, S. Moisa, J. Morgot, Direct evaluation of the sp3 content in diamond-like-carbon films by XPS, Appl. Surf. Sci. 1998, 136, 105–110. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Morgan, Comments on the XPS analysis of carbon materials, C 2021, 7, 51. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Biesinger, Accessing the robustness of adventitious carbon for charge referencing (correction) purposes in XPS analysis: Insights from a multi-user facility data review, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153681. [CrossRef]

- G. Beamson, D. Briggs, High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers - The Scienta ESCA300 Database, Wiley Interscience, 1992.

- N. Fairley, A. Carrick, The Casa Cookbook – Part 1: Recipes for XPS data processing, Acolyte Science, Cheshire, 2005.

- J. H. Scofield, Hartree-Slater subshell photoionisation cross-sections at 1254 and 1487 eV, J. Elec. Spec. Rel. Phenom. 1976, 8, 129–137.

- A. Law, M. Johnson, and H. Hughes, Synchrotron-radiation-excited angle-resolved photoemission from single-crystal graphite, Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 4289.

- I. Ozfidan, M. Karkusinski, P. Hawrylak, Electronic properties and electron-electron interactions in graphene quantum dots, Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2016, 10, 13–23.

- A. C. Ferrari, J. Robertson, Raman spectroscopy of amorphous, nanostructured, diamond-like carbon, and nanodiamond, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London A 2004, 362, 2477–2512. [CrossRef]

- M. E.H. Maia da Costa, F.L. Freire Jr., Deuterated amorphous carbon films: Film growth and properties, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2010, 204, 1993–1996. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Ferrari, D.M. Basko, Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene, Nature Nanotechnology 2013, 8, 235–246. [CrossRef]

- S. Nakahara, S. Stauss, H. Miyazoe, T. Shizuno, M. Suzuki, H. Kataoka, T. Sasaki, K. Terashima, Pulsed Laser Ablation Synthesis of Diamond Molecules in Supercritical Fluids, App. Phys. Express 2010, 2, 096201. [CrossRef]

- Rusli and, J. Robertson, G. A.J. Amaratunga, Photoluminescence behavior of hydrogenated amorphous carbon, J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 80, 2998–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Merlen, J.G. Buijnsters, C. Pardanaud, A Guide to and Review of the Use of Multiwavelength Raman Spectroscopy for Characterizing Defective Aromatic Carbon Solids: from Graphene to Amorphous Carbons, Coatings 2017, 7, 153.

- C. Pardanaud, C. Martin, P. Roubin, G. Giacometti, C. Hopf, T. Schwarz-Selinger, W. Jacob, Raman spectroscopy investigation of the H content of heated hard amorphous layers, Diam. Relat. Mat. 2013, 34, 100–104. [CrossRef]

- J. Robertson, Photoluminescence Mechanism in amorphous hydrogenated carbon, Diamond and Related Materials 1996, 5, 457–460. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Lye, A.J. Dekker, Theory of Secondary Emission, Phys. Rev. 1957, 107, 977–981. [CrossRef]

- Y. He, T. Shen, Q. Wang, G. Miao, C. Bai, B. Yu, J. Yang, G. Feng, T. Hu, X. Wang, W. Cui, Effect of atmospheric exposure on secondary electron yield of inert metal and its potential impact on the threshold of multipactor effect, Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 520, 146320. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin, D.C. Joy, A new examination of secondary electron yield data, Surf. Interface Anal. 2005, 37, 895–900. [CrossRef]

- H. Ibach, D. L. Mills, Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy and Surface Vibrations (Acad. Press, New York, 1982).

- A. M. Botelho do Rego, M. Rei Vilar, J. Lopes da Silva, Mechanisms of vibrational and electronic excitations of polystyrene films in high resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy, J. Elec. Spectr. Rel. Phenom. 1997, 85, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- M. Rei Vilar, A.M. Botelho do Rego, J. Lopes da Silva, F. Abel, V. Quillet, M. Schott, S. Petitjean, R. Jérôme, Quantitative Analysis of Polymer Surfaces and Films Using Elastic Recoil Detection Analysis (ERDA), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIRS), and High-Resolution Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy (HREELS) Macromolecules 1994, 27, 5900–5906.

- A. M. Botelho do Rego, A.M. Ferraria, M. Rei Vilar, Grafting of Cobaltic Protoporphyrin IX on Semiconductors toward Sensing Devices: Vibrational and Electronic High-Resolution Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study, J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013, 117, 22298–22306. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Botelho do Rego, J.L. da Silva, M. Rei Vilar, R. Voltz, Resonance mechanisms in electron energy loss spectra of stearic acid Langmuir-Blodgett monolayers revealed by isotopic effects, J. Electron. Spectrosc. 1998, 87, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- M. Diem, Modern Vibrational Spectroscopy and Micro-Spectroscopy, 2nd edition (John Wiley&Sons Ltd, The Atrium, 2015).

- NIST Standard Reference Database SRD Number 69. Last access to data: May 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Rei Vilar, M. Schott, J.J. Pireaux, C. Grégoire, P.A. Thiry, R. Caudano, A. Lapp, A.M. Botelho do Rego, J. Lopes da Silva, Study of Polymer Film Surfaces by EELS Using Selectively Deuterated Polystyrene, Surf. Sci. 1987, 189/190, 927–934.

- S. Clerc, J.R. Dennison, R. Hoffmann, J. Abbott, On the computation of secondary electron emission models, IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2006, 34, 2219–2225. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Dionne, Origin of secondary electron emission yield curve parameters, J. Appl. Phys. 1975, 46, 3347–3351. [CrossRef]

- N. Bundaleski, M. Belhaj, T. Gineste, O.M.N.D. Teodoro, Calculation of the angular dependence of the total electron yield, Vacuum 2015, 122, 255–259. [CrossRef]

| Sample | pD2 (Pa) | C (%) | H (%) | D (%) | O (%) | SEYmax | ET (eV) | ρ(g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 0 | 83.4 | 11.7 | 0 | 4.9 | 0.99 | 0.12 | 1.44 |

| 0.2D | 3.8·10-3 | 77.9 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 2.7 | 1.03 | 0.37 | 1.99 |

| 0.5D | 1.1·10-2 | 67.8 | 6.0 | 23.7 | 2.5 | 1.15 | 0.78 | 1.91 |

| 1D | 2.6·10-2 | 52.2 | 6.3 | 39.9 | 1.6 | 1.38 | 1.17 | 2.34 |

| 10D | 2.2·10-1 | 45.2 | 2.8 | 50.4 | 1.6 | 2.03 | 2.29 | 1.15 |

| Sample | α/β | graphitic (%) | sp3 C-H (%) | C-O (%) | C=O (%) | -(C=O)-O- (%) | H+D content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 0.45 | 88.14 | 3.29 | 1.91 | 2.55 | 2.01 | 11.7 |

| 0.2D | 0.50 | 85.17 | 6.43 | 2.41 | 2.57 | 1.73 | 19.4 |

| 0.5D | 0.58 | 71.09 | 20.4 | 3.75 | 2.46 | 1.05 | 29.7 |

| 1D | 0.58 | 52.75 | 38.11 | 4.83 | 2.46 | 0.96 | 46.2 |

| 10D | 1.00 | 0 | 75.99 | 21.53 | 2.35 | 0.13 | 53.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).