Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

19 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

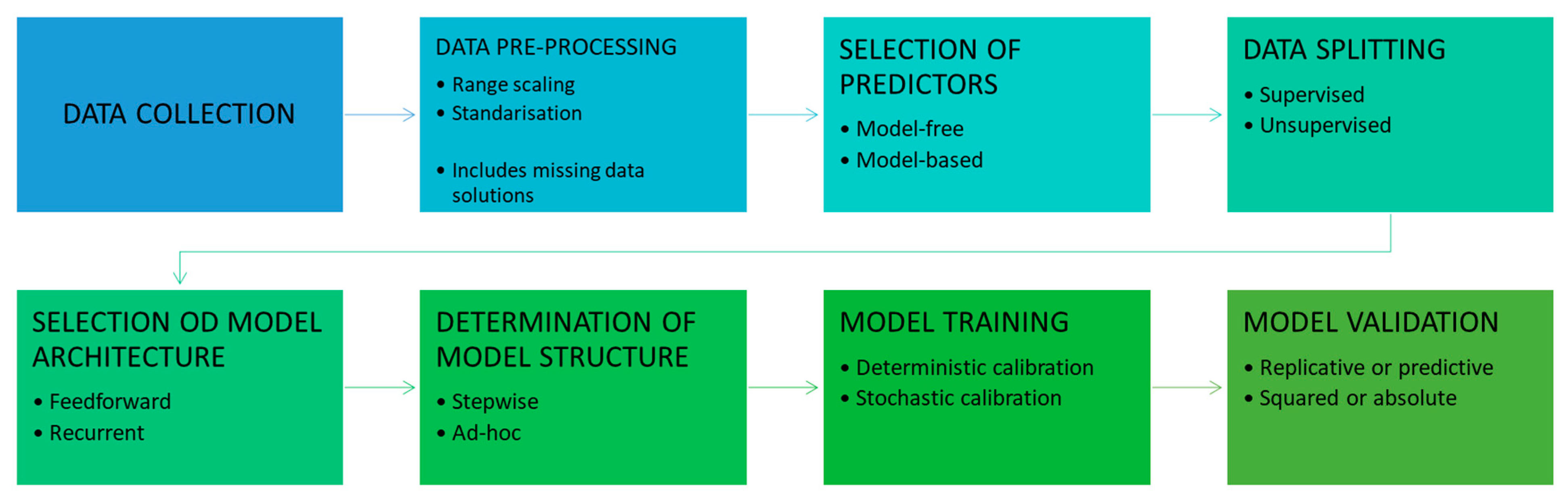

2. Basics of Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning

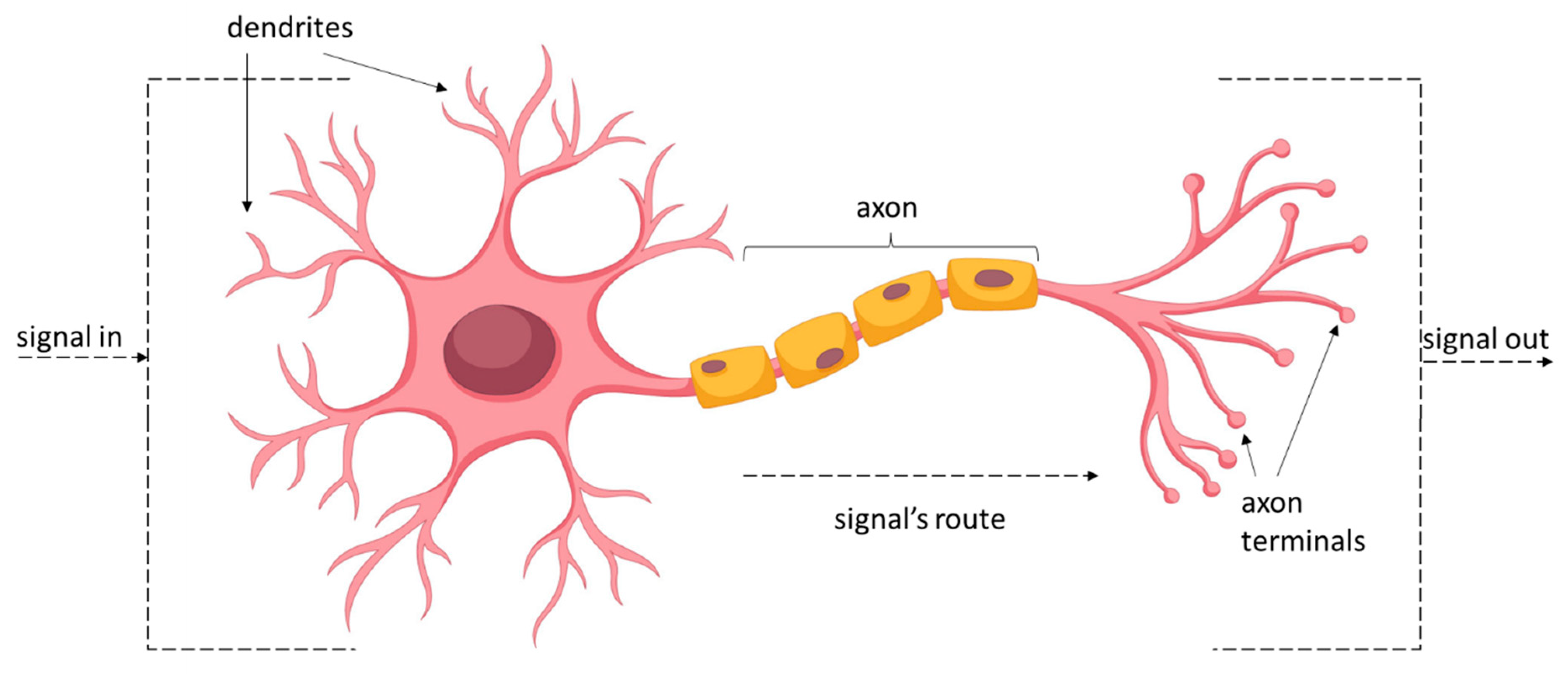

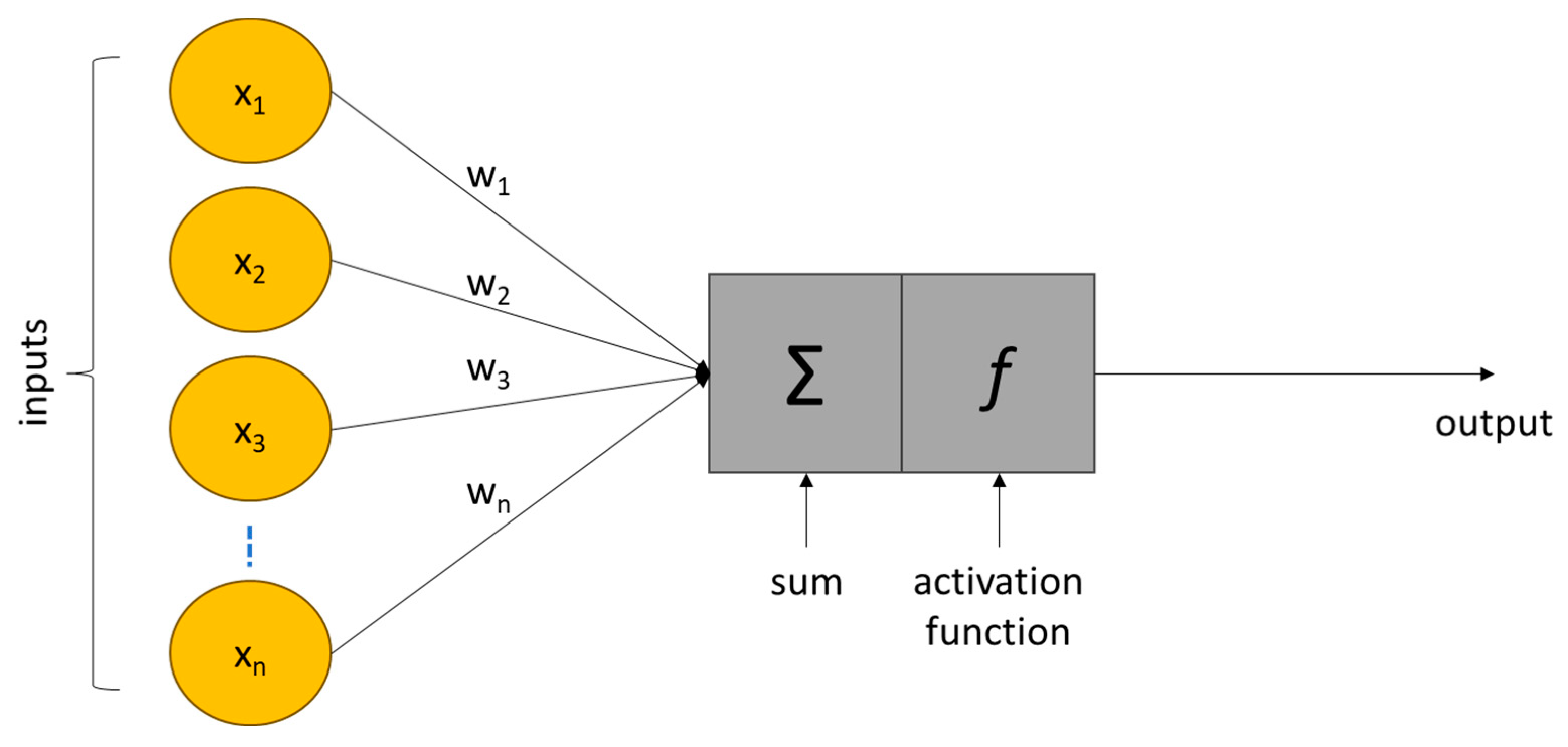

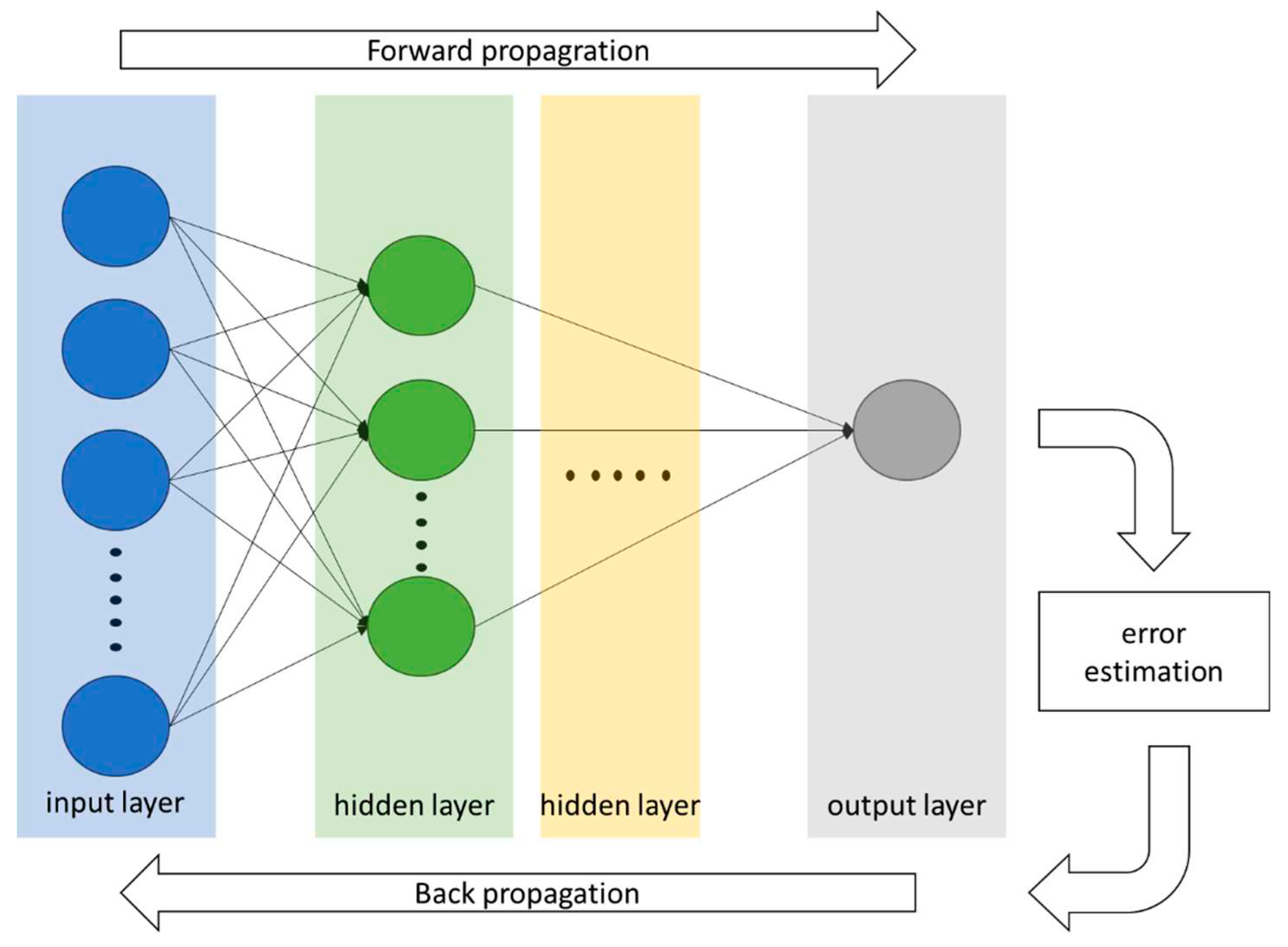

2.1. Artificial Neural Networks

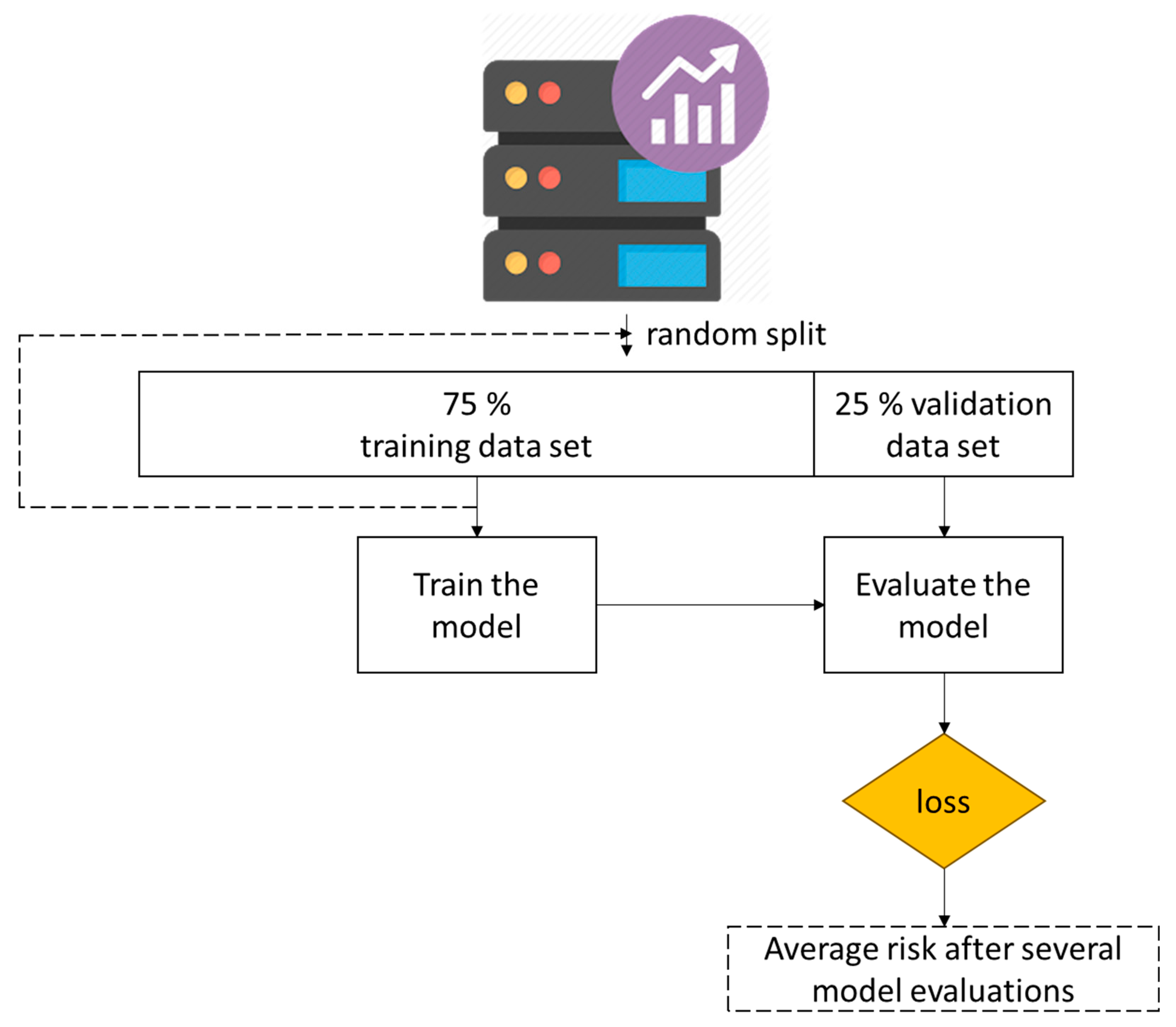

2.2. Machine Learning

- While sensing and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies have been rapidly advanced, more data amounts were collected;

- Access to powerful and affordable computational resources is better than with the design of machine-oriented chips like GPUs (Graphic Processor Units) or TPUs (Tensor Processing Units).

- Advanced machine learning algorithms have been developed and validated.

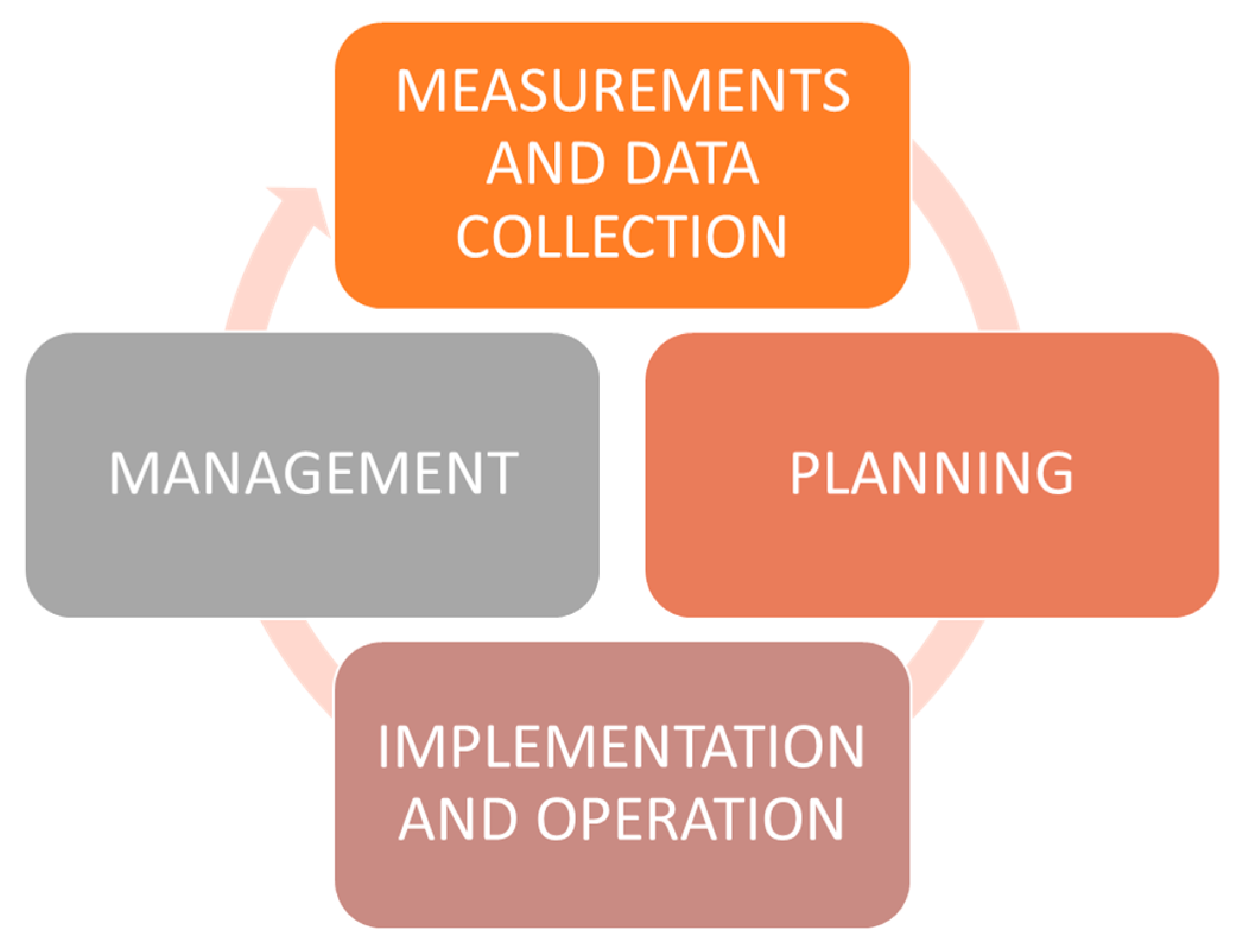

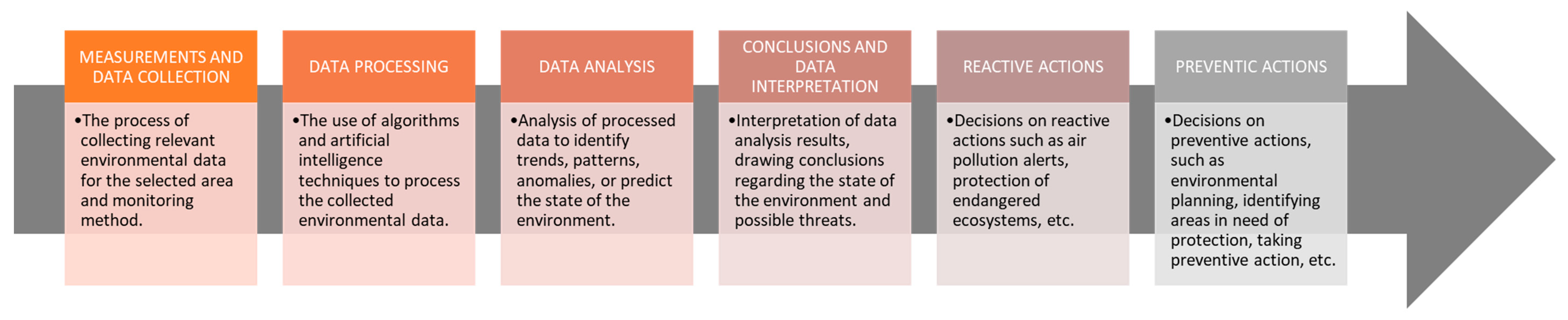

3. AI-Augmented Environmental Monitoring Systems vs. Data Security

- Proper interpretation of bias in AI algorithms: AI algorithms are designed to learn from data, but if the data used for training is biased, the algorithms can perpetuate and amplify that bias. This can lead to inaccurate or unfair decision-making in environmental monitoring, affecting the integrity and effectiveness of the systems.

- Full automation of systems and substitution of humans: While automation can enhance efficiency, relying solely on machines to replace human involvement in environmental monitoring may lead to the neglect of critical human insights, intuition, and judgment. Over-reliance on machines for cost reduction purposes could potentially overlook important contextual factors and compromise the accuracy and effectiveness of monitoring efforts.

- Cyberattacks: As AI systems in environmental monitoring become more interconnected and reliant on networked infrastructure, they become vulnerable to cyberattacks. Malicious actors could exploit security vulnerabilities to manipulate or sabotage data, compromise the integrity of monitoring systems, or gain unauthorized access to sensitive information.

- Cascading failures: AI systems are complex and interconnected, which means that a failure or error in one component can potentially propagate and lead to widespread consequences. In environmental monitoring systems, a cascading failure in AI algorithms or infrastructure could compromise the accuracy of data analysis, decision-making processes, and ultimately, the effectiveness of monitoring efforts.

- Ethical and legal aspects of data storage: The use of AI in environmental monitoring generates vast amounts of data, including potentially sensitive information. The ethical and legal aspects of storing, managing, and securing this data pose challenges. Ensuring privacy, consent, data ownership, and compliance with relevant regulations and frameworks are critical to maintaining trust and safeguarding the rights of individuals and organizations involved.

- Overall, addressing these identified threats is crucial for the responsible and effective deployment of AI in environmental monitoring systems, promoting data security, fairness, accountability, and ethical considerations.

4. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Environmental Data Management

4.1. Atmospheric Pollution

| Specific topic of a reviewed paper | Model applied | Compilation with and/or comparison to other numerical model | Data pre-processing method | Activation function / training algorithm | Loss function and error | General conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forecasting of PM10 hourly concentration [29] | Multiple-layered perceptrons (MLP)

|

No approach | Input data were standardized to zero mean and unity deviation | Training algorithm: quasi Newton | Sum of squared errors (SSE)

|

A genetic algorithm optimisation procedure allows to select variables with need to be taken as inputs into the NN model. This allows to save computational time. |

| Forecasting of PM10 maximum episodes in ambient air [20] |

|

No approach | No information | A sigmoid activation function | Absolute percent errors:

|

Neural model gave better results than linear model |

| Forecasting of annual PM10 emissions [15] | General Regression Neural Network (GRNN)guifeninputs were selected using a general algorithm based on a smoothing factor | Compared to conventional models as multiple linear regression (MLR) and principal components regression (PCR) | No information | A supervised training; | The root mean squared error (RMSE), the normalized mean squared error (NMSE), the mean absolute error (MAE), the correlation coefficient (R2), the index of agreement (IA), the fractional bias (FB)guifenR2GRNN (0.91-0.94)guifenR2PCR (0.55-0.94) | A smoothing factor applied in a as a sensitivity analysis tool (the larger the factor for a given inputs is, the more important the input is to the model);guifenBetter forecast performance for artificial neural networks than for classic statistical methods |

| Forecasting of the daily average concentration of PM10 [21] | MLP, radial basis function network (RBF), Elman recurrent network (EN), support machine vector machine working in regression mode (SVR) | ARX model | No information | No information | The root mean squared error (RMSE), the mean absolute error (MAE), the correlation coefficient (R2), the index of agreement (IA)guifenR2: 0.52 for ARXguifenR2: 0.82-0.95 for NN models compiled with wavelet transformation | Due to the complex relation between PM10 concentration and basic atmospheric parameters influencing the mechanisms of creation and spreading the pollution, PM10 prediction represents nonlinear problem and to obtain the highest accuracy of prediction the nonlinear model should be also applied. |

| Identifying pollution sources and predicting urban air quality [22] | Three machine learning models: single decision tree, decision tree forest, decision tree boost, support vector machines | PCA | Regression modelling | Bagging and boosting | The root mean squared error (RMSE), the mean absolute error (MAE), the correlation coefficient (R2)guifenR2 ~ 0.9 for all learning ensembles | PCA identified the vehicular emissions and fuel combustion as the major air pollution. All models gave satisfying results and can be used as tools in air quality prediction and management. |

| Forecasting of PM2.5 [23] | MLP | Air mass trajectory analysis and wavelet transformation | Regression modelling | A sigmoid activation function | MAE, RMSE, IA | The hybrid model of ANN and air mass trajectory analysis and wavelet transformation was applied. The model combined with meteorological forecasted parameters and respective pollutant predictors is considered to be an effective tool to improve the forecasting accuracy of PM2.5. |

| Identification of sources of combustion generated PM [24] | 5-fold-cross-validation for fitting PCR and CNN model | No approach | Regression modelling | Machine learning with Excitation-emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy was used for model training | Mean squared error as a loss function.guifenR2 = 0.745 for mobile sourcesguifenR2 = 0.908 for vegetative sources | The EEM-ML approach was mostly successful in predicting vegetative burning and mobile sources |

4.2. Automotive Exhaust Toxicity

| Specific topic of a reviewed paper | Model applied | Compilation with and/or comparison to other numerical model | Data pre-processing method | Activation function / training algorithm | Loss function and error | General conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification and optimisation of diesel engine emissions [32] | Hinging Hyperplane Trees (HHT) | No approach | Regression modelling | The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm | Normalized Root Mean Square Error | Incorporation of proposed model allowed to find a acceptable compromise between fuel consumption and emissions. |

| Modelling of nitrogen dioxide dispersion from vehicular exhaust emissions [34] | Multilayered NN with different configuration including and excluding meteorological data together with traffic-related data | No approach | No information | Hyperbolic tangent function, training using the supervised algorithm | RMSE, descriptive statistics | Better model performance when both traffic-related and meteorological data were taken into modelling processes |

| Performance and exhausts emissions of a biodiesel engine [35] | Multilayered NN | No approach | Input data were standardized to zero mean and unity deviation | Back propagation, scaled conjugate gradient, Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms were applied for model training | RMS, R2guifenR2 = 0.99 for all emission parameters | The relationship between fuel properties and emitted pollutants can be successfully determined with an usage of artificial neural networks. |

| Performance and exhausts emissions of a CNG-diesel engine [40] | MLP | No approach | No information | Back propagation for model training, a sigmoid activation function | R2 = (0.87-0.99) | Emission performance of an engine was modelled against engine speed (rpm) and the compressed natural gas-to-diesel ratio. Applied model allowed to concluded that a dual fuel CNG-diesel engine gives better brake thermal efficiency and lower emission than diesel engine. ANNs can provide accurate analysis and simulation of the engine performance. |

| Prediction of emission performance of HCCI engines with oxygenated fuels [41] | FFNN, RBF | No approach | No information | Different training functions were used for model training, i.e. scaled conjugate gradient, Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms and others | RMSE, R2guifenR2 = 0.99 for FFNN | Both FFNN and RBF were found to be capable of extracting the relationship between inputs and outputs to predict HCCI engine parameters. FFNN gave better performance, however computational time of RBF was shorter. |

| Prediction of exhaust gas temperature of a heavy-duty natural gas spark ignition engine [42] | ANN, random forest (RF), support vector regression (SVR), gradient boosting regression trees (GBRT) | 1D CFD model | Input data were standardized to zero mean and unity deviation | A sigmoid activation function, a back propagation training algorithms | RMSE, R2guifenR2 = 0.90 for ANNguifenR2 = 0.84 for RFguifenR2 = 0.92 for SVRguifenR2 = 0.98 for GBRT | All four deep learning algorithms were able to correctly capture the relationship between key engine control variables and exhaust gas temperature (EGT). The computations resulted in acceptable level of EGT prediction. |

4.3. Combustion Processes

5. Conclusions and Challenges

- AI may be successively applied as a tool supporting the environmental monitoring systems

- Multi-layered perceptron networks with backpropagation training (the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) seem to be the most frequently used model for training and short-time predictions. Moreover, a sigmoid (hyperbolic or tangent) activation function is mostly used as it is faster and efficient in mapping the nonlinearity among the hidden layer neurones than others.

- Designing of ANNs topology with possible highest satisfactory ratios needs many approaches and testing. Overtraining and underfitting of neural network are frequent problems while developing of AI-based models. To avoid both overfitting and underfitting, it is necessary to apply appropriate regularization techniques, such as L1/L2 regularization, early stopping, using proper cross-validation techniques, and adjusting neural network parameters to find the right balance between a model that is too complex and one that is too simple.

- In order to train the network on the base of a given data set, a separate algorithm is needed. This can be further applied for process predictions and optimisation, however another algorithms (based on machine learning) should be applied.

- Artificial neural networks and machine learning algorithms altogether may be utilized for optimisation of currently uncontrolled residential stoves fuelled by biomass in the aspect of limitation of pollutants emission, with a special concern on the emission which are nonregulated by any directive. This creates a possible gap to fill up and will be the subject of future work of the Author.

- How much data is required to train the model properly and effectively?

- How to incorporate the existing knowledge about fuel combustion in a chamber of a stove to the learning process of a model in order to improve the algorithm effectiveness and to protect the system from possible failures?

- How to sensitize the trained AI-based model to changes of many parameters during combustion process, which are sometimes naturally instable, in order to avoid the situation when an occurring failure is treated as a true input to the network?

- Data Privacy: ANN models often require access to large amounts of data, including sensitive information. Ensuring data privacy and protection is crucial to maintain the confidentiality and integrity of the data. Robust data anonymization techniques, secure data storage, and compliance with relevant privacy regulations are essential to address this challenge.

- Expert Interpretation of Results: ANNs can be complex and opaque models, making it challenging for domain experts to interpret and understand the underlying factors driving the model's predictions. The lack of interpretability can hinder trust and acceptance of ANN models in practical applications. Efforts are underway to develop techniques for interpreting and explaining the decisions made by ANNs, such as feature importance analysis and model visualization.

- Data Standardization: ANNs rely on high-quality and standardized data for training and validation. In environmental monitoring, data may come from diverse sources, with variations in formats, units, and quality. Ensuring data standardization and normalization is crucial to achieve reliable and accurate ANN models. Establishing data standards, data preprocessing techniques, and quality control measures are necessary to address this challenge.

- Limited Data Availability: ANN models require large amounts of labelled data for training, which may not always be readily available in environmental monitoring applications. Limited data can lead to overfitting or underfitting issues, resulting in suboptimal model performance. Techniques such as data augmentation, transfer learning, and active learning can help mitigate this challenge by making the most of the available data and optimizing the training process.

- Computational Resources: Training and optimizing ANNs can be computationally demanding, especially for large-scale environmental monitoring applications. Access to sufficient computational resources, such as high-performance computing clusters or cloud-based solutions, is essential to handle the complexity of ANN models efficiently.

- Ethical Considerations: The ethical implications of using ANNs in environmental monitoring should be carefully considered. Ensuring fairness, avoiding biases, and addressing potential discriminatory effects of ANN models are crucial. Regular audits, transparency in model development, and ongoing evaluation of the social and environmental impact of ANN applications are necessary to mitigate ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

Nomenclature

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| ANN | artificial neural network |

| ARX | auto-regressive model with exogenous inputs |

| BSFC | brake specific fuel-consumption |

| CART | classification and regression trees |

| C/H ratio | carbon-to-hydrogen mass ratio |

| DRNN | deep recurrent neural network |

| EEM | excitation-emission matrix |

| FC | fully-connected |

| FFNN | feed forward neural network |

| FG-CPD | chemical percolation devolatilization coupled with the functional group |

| GPUs | graphic processor units |

| GRU | gated recurrent unit |

| HM | Hopfield model |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LM | the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm |

| LPG | liquid petroleum gas |

| LSTM-NN | long short-term memory neural network |

| ML | machine learning |

| MLP | multi-layer perceptron |

| NARMAX | nonlinear autoregressive moving average with exogenous input |

| NARX | nonlinear autoregressive with exogenous inputs |

| NN | neural network |

| PAHs | polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| PM | particulate matter |

| PMF | positive matrix factorisation |

| RBF | radial basis function |

| RNN | recurrent neural network |

| RT-AQF | real-time air quality forecasting model |

| SF | scale-free network |

| SW | small world network |

| TPUs | tensor processing units |

References

- X. Zhang, K. Shu, S. Rajkumar, and V. Sivakumar, “Research on deep integration of application of artificial intelligence in environmental monitoring system and real economy,” Environ. Impact Assess. Rev., vol. 86, p. 106499, Jan. 2021.

- J. Zupan and J. Gasteiger, “Neural networks: A new method for solving chemical problems or just a passing phase?,” Anal. Chim. Acta, vol. 248, no. 1, pp. 1–30, Jul. 1991.

- J. J. Hopfield, “Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 79, no. 8, pp. 2554–2558, Apr. 1982.

- S. Kaviani and I. Sohn, “Application of complex systems topologies in artificial neural networks optimization: An overview,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 180, p. 115073, Oct. 2021.

- S. M. Cabaneros, J. K. Calautit, and B. R. Hughes, “A review of artificial neural network models for ambient air pollution prediction,” Environmental Modelling and Software, vol. 119. Elsevier Ltd, pp. 285–304, 01-Sep-2019.

- D. Lakshmi et al., “Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in adsorption of heavy metals using modified biochar,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 801, p. 149623, Dec. 2021.

- L. Zhang et al., “A review of machine learning in building load prediction,” Appl. Energy, vol. 285, p. 116452, Mar. 2021.

- C. Crisci, B. Ghattas, and G. Perera, “A review of supervised machine learning algorithms and their applications to ecological data,” Ecol. Modell., vol. 240, pp. 113–122, Aug. 2012.

- T. Hong, Z. Wang, X. Luo, and W. Zhang, “State-of-the-art on research and applications of machine learning in the building life cycle,” Energy Build., vol. 212, p. 109831, Apr. 2020.

- T. Zarra, M. G. Galang, F. Ballesteros, V. Belgiorno, and V. Naddeo, “Environmental odour management by artificial neural network – A review,” Environ. Int., vol. 133, p. 105189, Dec. 2019.

- Y. Zhang, M. Bocquet, V. Mallet, C. Seigneur, and A. Baklanov, “Real-time air quality forecasting, part I: History, techniques, and current status,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 60, pp. 632–655, Dec. 2012.

- Y. Zhang, M. Bocquet, V. Mallet, C. Seigneur, and A. Baklanov, “Real-time air quality forecasting, part II: State of the science, current research needs, and future prospects,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 60, pp. 656–676, Dec. 2012.

- A. L. Dutot, J. Rynkiewicz, F. E. Steiner, and J. Rude, “A 24-h forecast of ozone peaks and exceedance levels using neural classifiers and weather predictions,” Environ. Model. Softw., vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1261–1269, Sep. 2007.

- A. Russo, F. Raischel, and P. G. Lind, “Air quality prediction using optimal neural networks with stochastic variables,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 79, pp. 822–830, Nov. 2013.

- D. Z. Antanasijević, V. V. Pocajt, D. S. Povrenović, M. D. Ristić, and A. A. Perić-Grujić, “PM10 emission forecasting using artificial neural networks and genetic algorithm input variable optimization,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 443, pp. 511–519, Jan. 2013.

- S. Gürgen, B. Ünver, and İ. Altın, “Prediction of cyclic variability in a diesel engine fueled with n-butanol and diesel fuel blends using artificial neural network,” Renew. Energy, vol. 117, pp. 538–544, Mar. 2018.

- A. J. Jakeman, R. A. Letcher, and J. P. Norton, “Ten iterative steps in development and evaluation of environmental models,” Environ. Model. Softw., vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 602–614, May 2006.

- V. Galaz et al., “Artificial intelligence, systemic risks, and sustainability,” Technol. Soc., vol. 67, p. 101741, Nov. 2021.

- The Royal Society, Digital technology and the planet: Harnessing computing to achieve net zero. 2020.

- P. Perez and J. Reyes, “An integrated neural network model for PM10 forecasting,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 40, no. 16, pp. 2845–2851, May 2006.

- K. Siwek and S. Osowski, “Improving the accuracy of prediction of PM10 pollution by the wavelet transformation and an ensemble of neural predictors,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 1246–1258, Sep. 2012.

- K. P. Singh, S. Gupta, and P. Rai, “Identifying pollution sources and predicting urban air quality using ensemble learning methods,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 80, pp. 426–437, Dec. 2013.

- X. Feng, Q. Li, Y. Zhu, J. Hou, L. Jin, and J. Wang, “Artificial neural networks forecasting of PM2.5 pollution using air mass trajectory based geographic model and wavelet transformation,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 107, pp. 118–128, Apr. 2015.

- J. W. Rutherford, T. V. Larson, T. Gould, E. Seto, I. V. Novosselov, and J. D. Posner, “Source apportionment of environmental combustion sources using excitation emission matrix fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 259, p. 118501, Aug. 2021.

- X. H. Song et al., “Source apportionment of gasoline and diesel by multivariate calibration based on single particle mass spectral data,” Anal. Chim. Acta, vol. 446, no. 1–2, pp. 327–341, Nov. 2001.

- G. De Gennaro et al., “Neural network model for the prediction of PM10 daily concentrations in two sites in the Western Mediterranean,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 463–464, pp. 875–883, Oct. 2013.

- A. Donnelly, B. Misstear, and B. Broderick, “Real time air quality forecasting using integrated parametric and non-parametric regression techniques,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 103, pp. 53–65, Feb. 2015.

- H. J. S. Fernando et al., “Forecasting PM10 in metropolitan areas: Efficacy of neural networks,” Environ. Pollut., vol. 163, pp. 62–67, Apr. 2012.

- G. Grivas and A. Chaloulakou, “Artificial neural network models for prediction of PM10 hourly concentrations, in the Greater Area of Athens, Greece,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 1216–1229, Mar. 2006.

- D. Vinay Kumar, P. Ravi Kumar, and M. S. Kumari, “Prediction of Performance and Emissions of a Biodiesel Fueled Lanthanum Zirconate Coated Direct Injection Diesel Engine Using Artificial Neural Networks,” Procedia Eng., vol. 64, pp. 993–1002, Jan. 2013.

- S. Lotfan, R. A. Ghiasi, M. Fallah, and M. H. Sadeghi, “ANN-based modeling and reducing dual-fuel engine’s challenging emissions by multi-objective evolutionary algorithm NSGA-II,” Appl. Energy, vol. 175, pp. 91–99, Aug. 2016.

- C. Vlad, S. Töpfer, M. Hafner, and R. Isennann, “A Hinge Neural Network Approach for the Identification and Optimization of Diesel Engine Emissions,” IFAC Proc. Vol., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 399–404, Mar. 2001.

- M. Kapusuz, H. Ozcan, and J. A. Yamin, “Research of performance on a spark ignition engine fueled by alcohol–gasoline blends using artificial neural networks,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 91, pp. 525–534, Dec. 2015.

- S. M. S. Nagendra and M. Khare, “Artificial neural network approach for modelling nitrogen dioxide dispersion from vehicular exhaust emissions,” Ecol. Modell., vol. 190, no. 1–2, pp. 99–115, Jan. 2006.

- M. Canakci, A. Erdil, and E. Arcaklioǧlu, “Performance and exhaust emissions of a biodiesel engine,” Appl. Energy, vol. 83, no. 6, pp. 594–605, Jun. 2006.

- A. Parlak, Y. Islamoglu, H. Yasar, and A. Egrisogut, “Application of artificial neural network to predict specific fuel consumption and exhaust temperature for a Diesel engine,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 26, no. 8–9, pp. 824–828, Jun. 2006.

- N. Kara Togun and S. Baysec, “Prediction of torque and specific fuel consumption of a gasoline engine by using artificial neural networks,” Appl. Energy, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 349–355, Jan. 2010.

- Y. Cay, “Prediction of a gasoline engine performance with artificial neural network,” Fuel, vol. 111, pp. 324–331, Sep. 2013.

- R. K. Mehra, H. Duan, S. Luo, A. Rao, and F. Ma, “Experimental and artificial neural network (ANN) study of hydrogen enriched compressed natural gas (HCNG) engine under various ignition timings and excess air ratios,” Appl. Energy, vol. 228, pp. 736–754, Oct. 2018.

- T. F. Yusaf, D. R. Buttsworth, K. H. Saleh, and B. F. Yousif, “CNG-diesel engine performance and exhaust emission analysis with the aid of artificial neural network,” Appl. Energy, vol. 87, no. 5, pp. 1661–1669, May 2010.

- J. Rezaei, M. Shahbakhti, B. Bahri, and A. A. Aziz, “Performance prediction of HCCI engines with oxygenated fuels using artificial neural networks,” Appl. Energy, vol. 138, pp. 460–473, Jan. 2015.

- J. Liu, Q. Huang, C. Ulishney, and C. E. Dumitrescu, “Machine learning assisted prediction of exhaust gas temperature of a heavy-duty natural gas spark ignition engine,” Appl. Energy, vol. 300, p. 117413, Oct. 2021.

- L. Cammarata, A. Fichera, and A. Pagano, “Neural prediction of combustion instability,” Appl. Energy, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 513–528, Jun. 2002.

- A. Fichera and A. Pagano, “Application of neural dynamic optimization to combustion-instability control,” Appl. Energy, vol. 83, no. 3, pp. 253–264, Mar. 2006.

- L. Zhang, Y. Xue, Q. Xie, and Z. Ren, “Analysis and neural network prediction of combustion stability for industrial gases,” Fuel, vol. 287, p. 119507, Mar. 2021.

- L. M. Romeo and R. Gareta, “Neural network for evaluating boiler behaviour,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 26, no. 14–15, pp. 1530–1536, Oct. 2006.

- H. Nikpey, M. Assadi, and P. Breuhaus, “Development of an optimized artificial neural network model for combined heat and power micro gas turbines,” Appl. Energy, vol. 108, pp. 137–148, Aug. 2013.

- J. Smrekar, P. Potočnik, and A. Senegačnik, “Multi-step-ahead prediction of NOx emissions for a coal-based boiler,” Appl. Energy, vol. 106, pp. 89–99, Jun. 2013.

- E. Oko, M. Wang, and J. Zhang, “Neural network approach for predicting drum pressure and level in coal-fired subcritical power plant,” Fuel, vol. 151, pp. 139–145, Jul. 2015.

- Y. Sun, L. Liu, Q. Wang, X. Yang, and X. Tu, “Pyrolysis products from industrial waste biomass based on a neural network model,” J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis, vol. 120, pp. 94–102, Jul. 2016.

- S. Sunphorka, B. Chalermsinsuwan, and P. Piumsomboon, “Artificial neural network model for the prediction of kinetic parameters of biomass pyrolysis from its constituents,” Fuel, vol. 193, pp. 142–158, Apr. 2017.

- K. Luo, J. Xing, Y. Bai, and J. Fan, “Prediction of product distributions in coal devolatilization by an artificial neural network model,” Combust. Flame, vol. 193, pp. 283–294, Jul. 2018.

- P. Sakiewicz, K. Piotrowski, and S. Kalisz, “Neural network prediction of parameters of biomass ashes, reused within the circular economy frame,” Renew. Energy, vol. 162, pp. 743–753, Dec. 2020.

- J. F. Tuttle, L. D. Blackburn, K. Andersson, and K. M. Powell, “A systematic comparison of machine learning methods for modeling of dynamic processes applied to combustion emission rate modeling,” Appl. Energy, vol. 292, p. 116886, Jun. 2021.

- X. Li, C. Han, G. Lu, and Y. Yan, “Online dynamic prediction of potassium concentration in biomass fuels through flame spectroscopic analysis and recurrent neural network modelling,” Fuel, vol. 304, p. 121376, Nov. 2021.

- L. Zhang, Y. Xue, Q. Xie, and Z. Ren, “Analysis and neural network prediction of combustion stability for industrial gases,” Fuel, vol. 287, p. 119507, Mar. 2021.

| Specific topic of a reviewed paper | Model applied | Compilation with and/or comparison to other numerical model | Data pre-processing method | Activation function / training algorithm | Loss function and error | General conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion instability [43,44,56] | MLP | NARMAX as a testing set | No information | Back propagation (a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm) was applied for model training | No information | The NARMAX model implemented using a neural network was effective in long-term predictions. This can be applied as a suitable control solution ensuring the stability of he combustion process basing on the control three main parameters. |

| Evaluation of boiler behaviour and combined heat and power micro gas turbines [46,47] | FFNN | No approach | No information | Back propagation | real and equation-based monitoring data | The NN can predict a set of operational variables and the fouling state of the boiler. It is also pointed out the NN is a stronger tool for monitoring than equation-based monitoring. |

| Prediction of NOx emissions for a coal-based boiler [48] | Random-walk (RW), Auto-regressive with exogenous inputs (ARX), Auto-regressive moving-average with exogenous inputsguifen(ARMAX), Neural networks (NNs), Support vector regression (SVR) | No approach | 4-fold cross-validation of the models, data with zero mean and standard deviation | Back propagation | MAE | Results show that the adaptive modelling approach does not significantly improve the NOx prediction. Hence, the recommended model structure for multi-step NOx prediction is a static ARX model with occasional retrainings. |

| Prediction of drum pressure and level in coal-fired subcritical power plant [49] | NARX NN | No approach | mapminmax and removeconstantrows processing functions | A sigmoid transfer activation function, open loop function | MSE | The results of the validation and testing showed good agreement. |

| Prediction of pyrolysis products from industrial waste biomass [50] | A 3-layer ANN | No approach | No information | A logarithm sigmoid transfer function at the hidden layer and a linear function at the output layer. Back propagation: the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm for model training | MSEguifenR2 = 0.99 | Three processing parameters, space velocity, reaction temperature, and particle size, were identified as input variables in the model, while the target output variables include selectivity of the four gas products (H2, CO, CH4, CO2). There was fairly good agreement between the experimental results and simulated data for the biomass pyrolysis process. |

| Prediction of kinetic parametersguifenof biomass pyrolysis from its constituents [51] | Mammalian neural networks | No approach | No information | A hyperbolic tangent sigmoid function (tansig) was used in the hidden layer whilst a linear transfer function (purelin) was used in the output layer. The Levenberg-Marquardt backpropagation algorithm was used for model training. | MSEguifenR2 > 0.90 | This study applied ANN for constructing the correlation between biomass constituents and the kinetic parameters (activation energy ‘Ea’, pre-exponential factor ‘k0’ and reaction order ‘n’) of biomass pyrolysis. Three ANN models were developed, one for each of the three kinetic parameters. The relationships between the main biomass components and the output parameters were non-linear and could potentially be predicted by the selected ANN models. The combination of tansig/purelin transfer function provided the lowest mean square error (MSE) in many cases. |

| Prediction of product distributions in coal devolatilization [52] | FFNN | FG-CPD | No information | A tangent sigmoid activation function was used. | MSE | The results show that the detailed product distributions of coal devolatilization predicted by the proposed ANN model are in good agreement with the experimental data for both the training and validation database, and the ANN model can give a more accurate prediction on both the yield of each component and its evolution compared with the FG-CPD model. |

| Online dynamic prediction of potassium concentration in biomass fuels [55] | long short-term memory neural network (LSTM-NN) and deep recurrent neural network (DRNN) | No approach | No information | The activation functions of the hidden layer and the fully connected layer are the tanh function and the Leaky ReLU function, respectively | RMSA, MAE, MAPE | It is found that the DRNN and LSTM-NN models have a longer computational time than the RNN. It is thought that the architecture of the DRNN model is more complex than those of the RNN and LSTM-NN models, resulting in a longer computational time. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).