1. Introduction

The transition to a sustainable society is a major challenge for the humankind. For that it will be necessary to use renewable materials that should be complemented with a substantial reduction in the use of natural resources and in the environmental impacts, such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [

1]. In this sense, is essential to comprehend and improve the environmental profile of the materials used in construction.

Biomass is the only renewable material that can be simultaneously converted into energy, fuels, materials, and chemical products [

2]. However, most of the biomass is being wasted, which increase an environmental issue. In fact, for forest biomass, this constitutes a severe problem due to the large amounts available that increase the risk of forest fires [

3]. Forest biomass consists in lignocellulosic materials (shrubs, trees and their trunks, barks, branches, leaves, flowers and even fruits) from forest exploitation activities, under-cover forests, and uncultivated areas. It is worth mentioned that, nowadays biomass as well as forest biomass are being mostly valorized for energy purposes [

4,

5,

6].

Portugal has diverse raw materials that has the potential to be used as sources of biomass, especially forest biomass. The potential to biomass accumulation and availability as an energy source is enormous in forests due of tree dimensions and their life spans [

7]. Forests represents circa of 3.2 million hectares of Portugal land area and the annual production of forest biomass is about 6.5 million tons per year [

8]. However, the availability of forest biomass is only 2.2 million tons per year [

8].

Wood-based composite (WBC) refers to a wide range of products, in which wooden elements are bonded with other wooden or non-wooden materials [

9,

10]. Nowadays, there are WBCs available on the market in a wide variety of typologies, such as plywood, Oriented Strand Board (OSB), particleboard, or Medium-Density Fiberboard (MDF) [

9].

The green transition in the wood-based panel industry intends to decarbonize the sector, as well as implement a circular development model in order to reduce pollution and waste generation [

11,

12]. In this sense, this industry has the opportunity to create a new path for a sustainable growth, fighting climate change and reducing their dependence on natural resources [

11,

12].

One way to achieve this could be by collecting forest biomass from Portuguese forests that will reduce thermal load in these places. This thermal load results from forest biomass accumulation that increase the risk of fire [

13]. In fact, from 2011 to 2021, the type of land cover burnt was forest stands (49% - 63,809 ha), bushes and natural pastures (44% - 58,004 ha) and agricultural land (7% - 8893 ha) [

3]. Undifferentiated forest biomass could be used as a raw material for the technical development of a sustainable composite.

Thus, we aim to characterized undifferentiated forest biomass, as well as the composite developed from this renewable material. Furthermore, we pretend to provide a new material for construction and decoration (through decorative panels) that at the same time is a sustainable composite and contributes to reduce the use of natural resources and all environmental impacts associated.

2. Materials and Methods

Forest biomass comes from North of Portugal and was provided by Ferreira Martins & Filhos, SA. (Braga, Portugal), as well as the production of green wood composite (GWC) (based on forest biomass).

2.1. Biomass pretreatment

In a first approach it was eliminated all the biomass components that could interfere with its correct griding, such as small rocks. Then, forest biomass was dried naturally in a dry and well-ventilated place. Finally, the dried forest biomass was crushed in a mechanical mill (CM500 mill from Laarmann).

2.2. Forest Biomass Characterization

2.2.1. Moisture Content

According to EN 322:2002, it was determined the Moisture Content (MC) of forest biomass. This procedure consists in the determination of the amount of water present in the wood and is normally expressed as a percentage of the mass of the oven-dry wood. In this sense, it was weighted three samples of 10 g of undifferentiated forest biomass that corresponds to the day of material arrival, after 3 days and after a week. These samples pretend to evaluate forest biomass variations over time. Then, they were placed in a DRY-Line® Prime oven (VWR) at 103 ± 2 ºC, weighting every hour until the weight stabilizes. The accuracy of MC is associated with accuracy of the balance used (0.01 g). In this sense, it was used a balance with an accuracy of 0.010g whereby the variation of MC should be less than 0.1%.

To verify the variability of the relative humidity of undifferentiated forest biomass, this procedure was repeated three times for each sample. MC was determined by the equation:

in which, m0 is the initial weight of biomass and m1 is final weight of biomass.

2.2.2. Organic Matter

Organic Matter (OM) was determined by Loss On Ignition method (LOI). This methodology consists of comparing the mass of a biomass sample before and after its combustion at elevated temperatures. Combustion eliminates organic matter, leaving the mineral fraction that is resistant. In order to determine the percentage of each one in the sample, calcination of the same was carried out using a tubular furnace from Termolab. This oven allows you to reach temperatures of up to 1800 °C and keep them constant for as long as necessary. Thus, forest biomass was weighed in a porcelain crucible and heated at 500 °C for one hour. At this temperature it was considered that the cellulose and hemicellulose had already been degraded and were not present in the sample [

14]. Posteriorly, the sample was reweighed and heated at 900°C for one hour. After this time, it was considered that the lignin would also have degraded and would not form part of the sample [

14]. Each component of OM was determined by the equation:

in which, m1 is the initial mass of forest biomass and m2 is the final mass of forest biomass.

2.2.3. pH

pH of forest biomass was measured in cold water extract. In this sense, it was weight 4.0 g of undifferentiated forest biomass and mixed with 15mL for 30 minutes. Posteriorly, it was centrifuged with a Hettich MIKRO 220R. Finally, the supernatant was used to measure pH with a Hanna pH Meter.

2.3. Composite Characterization

2.3.1. Moisture Content

To MC determination the prototypes were cut in 1.5x5x5 cm and was followed the same procedure applied to forest biomass characterization.

2.3.2. Density

This parameter was determined according to EN 323:1993, in which the test pieces should be square in shape, with sides of a nominal length of 50 mm. For that, the prototypes were cut 1.5 x 5 x 5 cm. Then, these test pieces were weight and the dimensions measured. Density was determined by the equation:

in which, m is the mass of the test pieces (g), b1 and b2 is the length of the test pieces sides, and t is the thickness.

2.3.3. Thickness Swelling

Thickness swelling was determined according to EN 317:1993, in which the test pieces should be square in shape, with sides length of 50±1 mm. In this sense, the prototypes were cut 1.5 x 5 x 5 cm. Then, the test pieces should be immersed during 24 hours in clean, still water with pH of 7 and temperature of 20±1 °C. During the test period this temperature should be maintained. After the immersion time has elapsed, the test pieces were taken out of the water, remove the excess of water and measure the thickness of each test piece. Thickness swelling was determined by the equation:

In which, t1 and t2 is the thickness of test piece, respectively before and after immersion (mm).

2.3.4. SEM

The composite characteristics, as well as prototype’s structure were analyzed by Scanning Electron 110 Microscopy (SEM) Hitachi Flex SEM 1000. It was applied to forest biomass-based composite panel and floor.

In this way, it was cut 1 cm2 of both samples and embedded in a polyethylene mold greased with Silicone Oil, with a mixture of resin and EpoFix hardener (25:3). These were maintained under normal pressure and temperature conditions and then were cut and polished on the Struers Planopol-2 polishing machine. Finally, the samples were deposited unto carbon tape for SEM analysis.

2.4. Life Cycle Assessment

The present LCA consist in a gate-to-gate study that aims quantify and compare the potential environmental impacts, as well as to evaluate the differences between these two types of composites (

Figure 1). For this study the environmental impacts were analyzed and compared by using a weight-based functional unit of 100 kg. This functional unit intend to achieve an industrial scale, considering direct emissions from the production of panels, as well as indirect impacts associated with the acquisition of precursor material.

This approach for the study of the environmental impact of the production of GWC panels at an industrial level was chosen considering that the fabrication of forest biomass-based composite applied in panels will have a similar production as OSB. In this sense, this simplification, allows that the differences between the two production processes are given by the factors that differentiate them, namely the precursor material and the adhesive used. Thus, the infrastructure used, as well as the expenses (energy and resources) associated with the place of production will be the same in both cases, so they will not be considered in this LCA.

2.4.1. Life Cycle Inventory Data

The assessment of the environmental impacts associated with the panels fabrication was based on inventory data from laboratory-scale synthesis procedures found in the Ecoinvent® 3.5 database. The foreground system of the composites production consists of chemicals used as raw material, such as precursor material (forest biomass and wood chips) and the adhesive, which consists of a mixture of water and an adhesive in urea-formaldehyde powder. This were modeled with the following data present in the Ecoinvent®3.5 database (RoW standing for Rest of the World, and RER for regional market for Europe).

2.4.2. Environmental impact assessment

The present LCA study is based on a gate-to-gate approach since only one process in the entire production chain is evaluated, that in this case is the precursor material used to fabricate the panels. Environmental impacts were modeled using the ReCiPe 2016 V1.03 endpoint method, Hierarchist version [

15], which evaluates three categories of potential impacts (Human Health, Ecosystems and Resources). The Hierarchist perspective is a scientific consensus model to deal with uncertainties and assumptions based on the most common policy principles with regards to the time frame and plausibility of impact mechanisms. In Human Health (HH) subsection were assessed Global Warming – Human Health (GW–HH), Stratospheric ozone depletion (SO), Ionization Radiation (IR), Ozone formation – Human Health (OF), Fine Particulate Matter formation (FPM), Human Carcinogenic toxicity (HC), Human Non-Carcinogenic toxicity (HNC) and Water Consumption – Human Health (WC–HH). Ecosystems (E) potential impacts evaluated were Global Warming – Terrestrial Ecosystems (GW–TE), Global Warming – Freshwater Ecosystems (GW–FE), Ozone Formation – Terrestrial Ecosystems (OF–TE), Terrestrial acidification (TA), Freshwater Eutrophication (FE), Marine Eutrophication (ME), Terrestrial EcoToxicity (TET), Freshwater EcoToxicity (FET), Marine EcoToxicity (MET), Land Use (LU), Water Consumption – Terrestrial.

3. Results

3.1. Biomass characterization

3.1.1. MC, OM, and pH

Biomass moisture show that there is a decrease in water content over time (

Figure 2A) since MC of undifferentiated forest biomass in day of arrival was maximum circa 30% (24h) and 1 week after arrival was 20% (168 h). This is an essential parameter that could affect the aggregation of particles and the efficiency of binding agents.

Despite we pretend to use undifferentiated forest biomass in composite fabrication it was determined MC of two different particle size (

Figure 2B). Thus, it was verified that particle size significantly affects the amount of water retained by the biomass, in which the larger particle is the best to retain moisture over time (between 3 and 5% more retention).

Organic Matter present in the biomass is mainly responsible for the stability of the aggregates, for a part of the ion exchange capacity and, very importantly, it provides the necessary components for microbial activity. It is estimated 8-20% of the total mass of a biomass sample is lignin, 30-50% is cellulose and 20-35% is hemicellulose. These polymers act as structural components of plants, giving rigidity and protecting them from pests and external agents. The results of OM for undifferentiated forest biomass can be observed in

Figure 3.

Finally, pH of undifferentiated forest biomass was also determined. However due to their heterogeneity the results obtained are presented as a range of values. In this sense, pH of this sample was between 4 and 6. pH values of most wood species are naturally acidic, with most of them having a pH between 4.0 and 5.5 [

16]. Besides this, in temperate zones, the values of pH of several tree species range from 3.3 to 6.4 and tropical tree species range from 3.7 to 8.2 [

16]. Thus, pH values of undifferentiated forest biomass are in accordance with the pH values for wood species and temperate climates such as Portugal (origin of biomass). It is worth mentioning that wet environment and higher temperature results in the increase of wood acidity [

16].

3.2. Forest biomass-based Composite characterization

Forest biomass-based composite was applied either in panels and floor, as it is possible to observe in

Figure 4.

The results of the main properties evaluated can be consulted in

Table 1.

Comparing the density values with other wooden composites, such as OSB it is possible to verify that forest biomass-based composite has slightly higher values. On the other hand, MC of this composite also has higher values than OSB.

MC of forest biomass-based composite applied in panels and floor over time can be observed in

Figure 5. It is possible to verify that MC of panels stabilizes after 17 hours, however in the floor only stabilizes after 23 hours.

SEM analysis can contribute to understand the composite characteristics, prototype’s structure, and to increase the knowledge of these type of materials in various fields such as materials science, environmental engineering, and biomass utilization. SEM of forest biomass-based panel (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) showed the microcracks and alterations observed agree both in size and in shape with what would be expected for a deck of the same characteristics made from conventional wood materials.

3.3. LCA of forest biomass-based composite

In this LCA study, it was performed a comparison of potential environmental impacts, considering a weight-based functional unit of 100 kg of composite. However, our intention was to compare, for each panel, the contributions of the different impact categories of the input involved in each composite and with each other. In this sense, it is not intended to make quantitative appreciations of the environmental impacts of each material input.

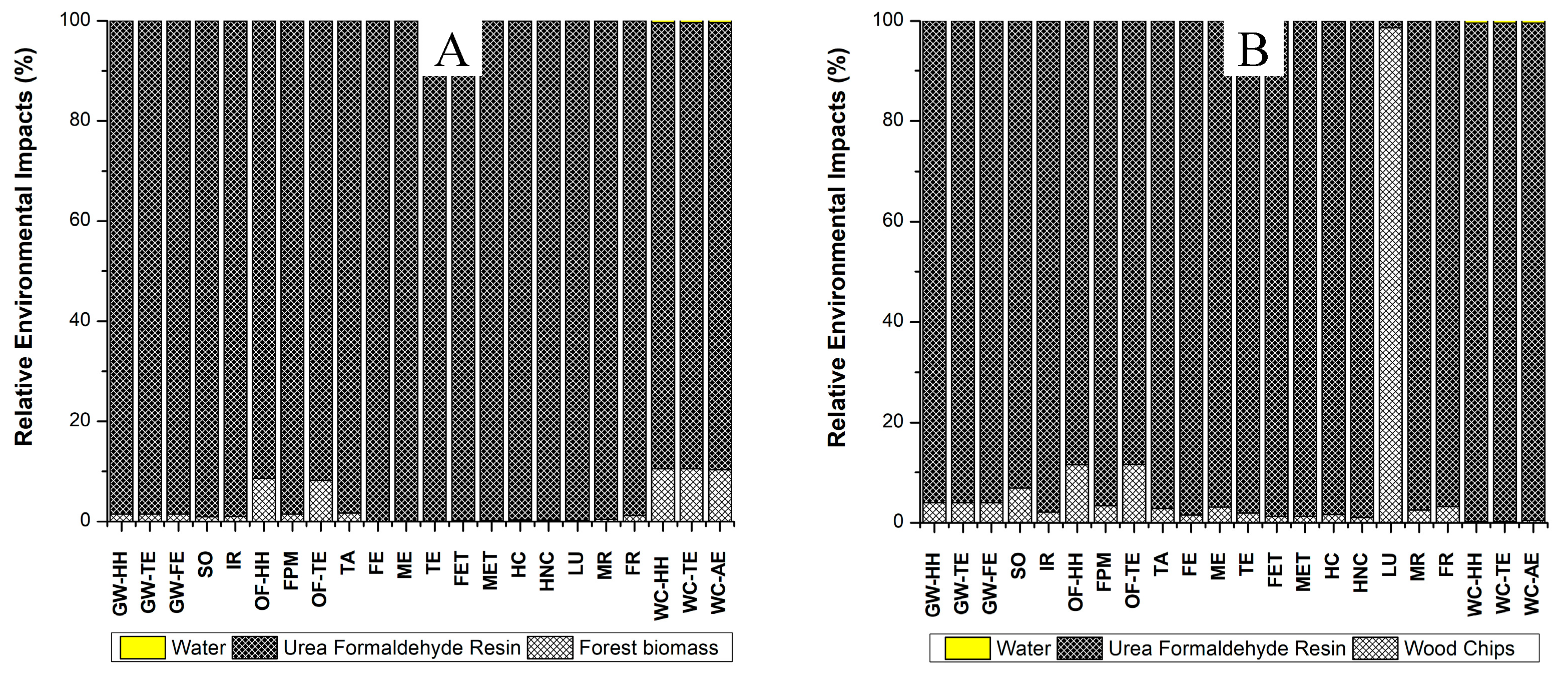

Environmental impacts associated with panels of forest biomass-based composite and wood chips-based composite can be observed in

Figure 8.

It is possible to verify that the greatest contributor for both composite is the urea formaldehyde resin, in almost all categories. However, for wood chips-based composite the precursor material is the highest contributor in the Land Use (LU) category. Thus, changing the precursor material implies a greater difference in the impacts of LU category. This allows to conclude that undifferentiated forest biomass-based composite can be a major opportunity to wood industry become more environmentally sustainable. It is worth mentioning that the precursor material wood chips has a slightly greater influence than forest biomass in several categories (GW-HH, GW-TE, GW-FE, SO, IR, OF-HH, FPM, OF-TE, TA, FE, ME, TE, FET, MET, HC, HNC, MR and FR). However, in the water consumption categories (WC-HH, WC-TE and WC-AE), the precursor material forest biomass has a slightly greater influence in the environmental impacts. It should be noted that, regardless of the precursor material, in this composite process water has a negligible influence in all categories of potential environmental impacts.

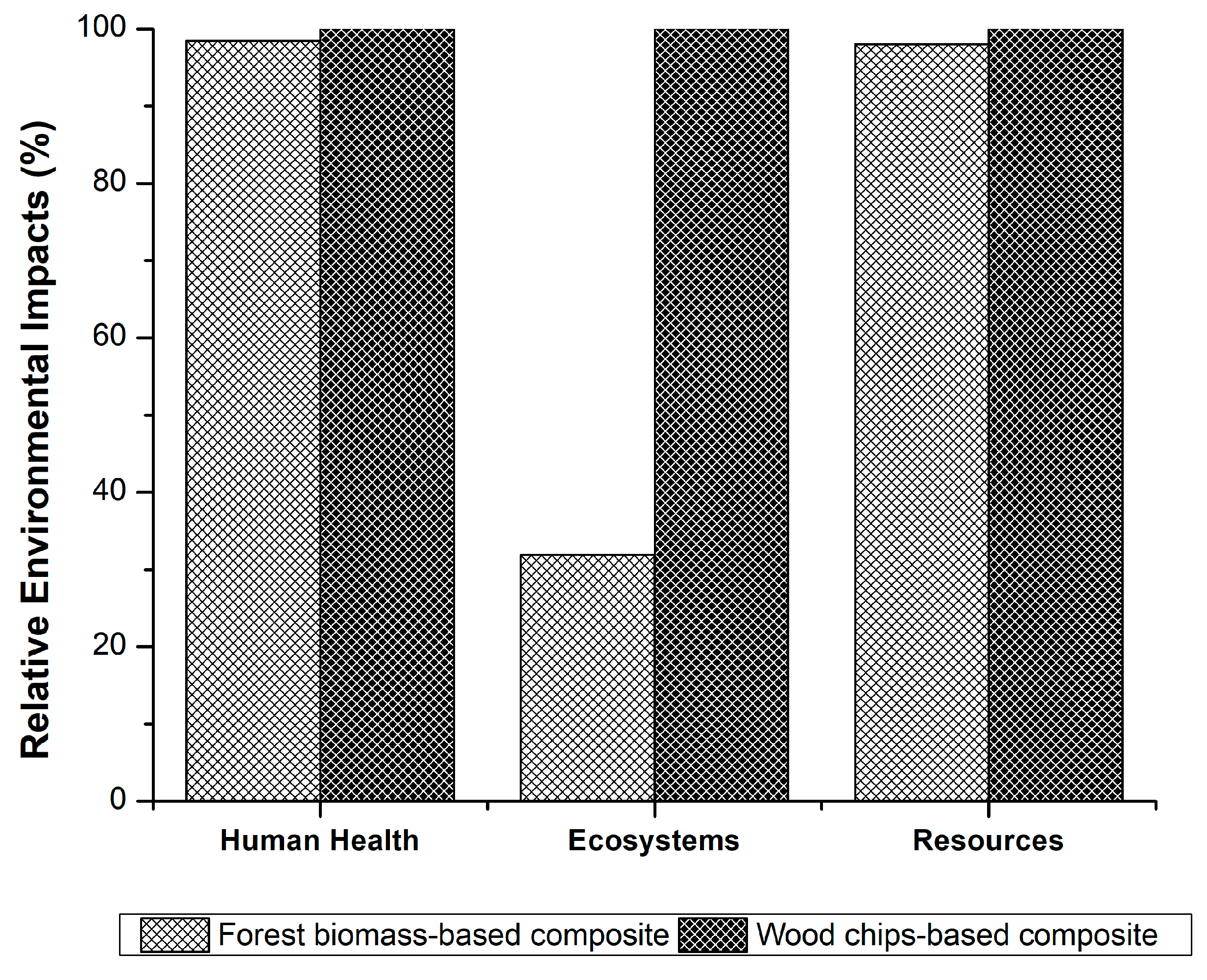

It was performed a comparison with both composite in order to understand each composite is associated with higher environmental impacts (

Figure 9).

This comparison shows that for Human Health and Resources categories there is not significant differences (less than 2%) between these composites. However, in Resources category, it is possible to verify that forest biomass-based composite is associated with less environmental impacts (difference of 68% of impacts).

5. Conclusions

This work allowed to develop and characterized an undifferentiated forest biomass-based composite for wood products, such as panels and floor. The aim of this work was to develop and contribute with novel composites that could allow the green transition in wood industry through panels and floor fabrication from massive residue (forest biomass). This work should provide a new strategy for the development of new and innovative wood products, with commercial value.

Properties evaluated for panel and floor based on forest biomass composite does not show huge differences with standard panels, such as OSB. This is an excellent indicator for the future development of this product and subsequent commercialization, what could allow to achieve a more sustainable future in the wood industry.

LCA identify the adhesive as the major contributor for these commercial products. In this sense, undifferentiated forest biomass-based composite further developments should be for a greener adhesive. It is worth noting that panels from forest biomass represent lower impacts to the ecosystems.

Thus, the obtained results should be useful for the future development of novel commercial products using environmentally friendly materials, such as forest biomass.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F., Y.L., L.P.d.S. and J.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F., Y.L. and J.E.S.; writing—review and editing, L.P.d.S. and J.E.S.; supervision, L.P.d.S. and J.E.S.; funding acquisition, L.P.d.S. and J.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded through the COMPETE 2020 and PORTUGAL 2020, specifically, through funding the project “Green Wood Composite (GWC)” (POCI-01-0247-FEDER-038383). It is acknowledged that these results are an integral part of the GWC reports: A2 (September 2019), A6 (November 2020), A7 (September 2020), and Final report (December 2020). The Portuguese “Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia” (FCT, Lisbon) is acknowledged for funding the project PTDC/QUI-QFI/2870/2020, R&D Units CIQUP (UIDB/00081/2020) and the Associated Laboratory IMS (LA/P/0056/2020). Sónia Fernandes acknowledges the FCT for funding her PhD grant (2021.05479.BD).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sathre, R. and S. González-García, Life cycle assessment (LCA) of wood-based building materials, in Eco-efficient Construction and Building Materials. 2014. p. 311-337. [CrossRef]

- Opia, A.C., et al., Biomass as a potential source of sustainable fuel, chemical and tribological materials – Overview. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2021. 39: p. 922-928. [CrossRef]

- Casau, M., et al., Reducing Rural Fire Risk through the Development of a Sustainable Supply Chain Model for Residual Agroforestry Biomass Supported in a Web Platform: A Case Study in Portugal Central Region with the Project BioAgroFloRes. Fire, 2022. 5(3). [CrossRef]

- Berndes, G., et al., Forest biomass, carbon neutrality and climate change mitigation. 2016. 27. [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.G., et al., Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2012. 23(3): p. 396-405. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, G., A. Sharma, and A. Chandra Dash, Biomass from trees for bioenergy and biofuels – A briefing paper. Materials Today: Proceedings, 2022. 65: p. 461-467. [CrossRef]

- Cristina Gonçalves, A., I. Malico, and A. M.O. Sousa, Energy Production from Forest Biomass: An Overview, in Forest Biomass - From Trees to Energy. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S., et al., Biomass resources in Portugal: Current status and prospects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017. 78: p. 1221-1235. [CrossRef]

- Zanuttini, R. and F. Negro, Wood-Based Composites: Innovation towards a Sustainable Future. Forests, 2021. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Laboratory, F.P., Wood Handbook - Wood as an Engineeering Material. 2010, Forest Products Laboratory and United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Madison, Wisconsin. p. 508.

- Antov, P., et al., Advanced Eco-Friendly Wood-Based Composites II. Forests, 2023. 14(4). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., et al., Forest Biomass Availability and Utilization Potential in Sweden: A Review. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 2020. 12(1): p. 65-80. [CrossRef]

- Enes, T., et al., Thermal Properties of Residual Agroforestry Biomass of Northern Portugal. Energies, 2019. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Dorez, G., et al., Effect of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin contents on pyrolysis and combustion of natural fibers. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2014. 107: p. 323-331. [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J., et al., ReCiPe2016: a harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 2016. 22(2): p. 138-147. [CrossRef]

- Geffert, A., J. Geffertova, and M. Dudiak, Direct Method of Measuring the pH Value of Wood. Forests, 2019. 10(10). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).