Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- 1)

- Scanning dental record by an intraoral scanner connected to a dedicated software

- 2)

- Processing the digital data with a program that allows the visualization of the dental product

- 3)

- Manufacturing processes performed by subtractive (by milling it from a prefabricated block) or additive techniques [1]

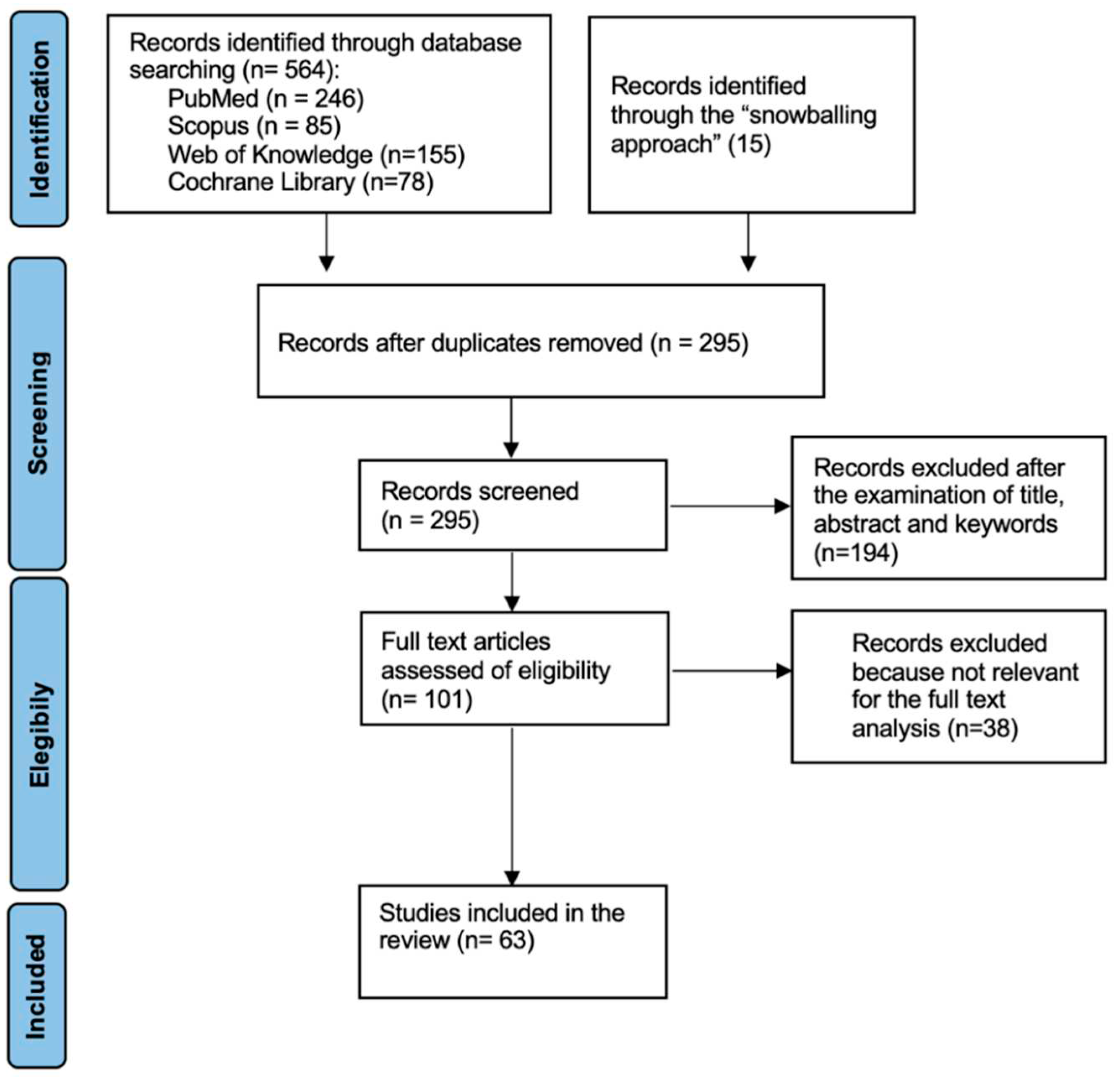

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search strategy

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- 1)

- Articles addressing at least one of the following topics regarding dental materials for CAD-CAM systems: clinical indications and/or outcomes, manufacturers, mechanical features (flexural strength, hardness, and elastic modulus) and materials’ composition or optical properties.

- 2)

- Studies performed in vitro or in vivo.

- 3)

- Systematic and Narrative reviews.

3. Results

4. Discussion

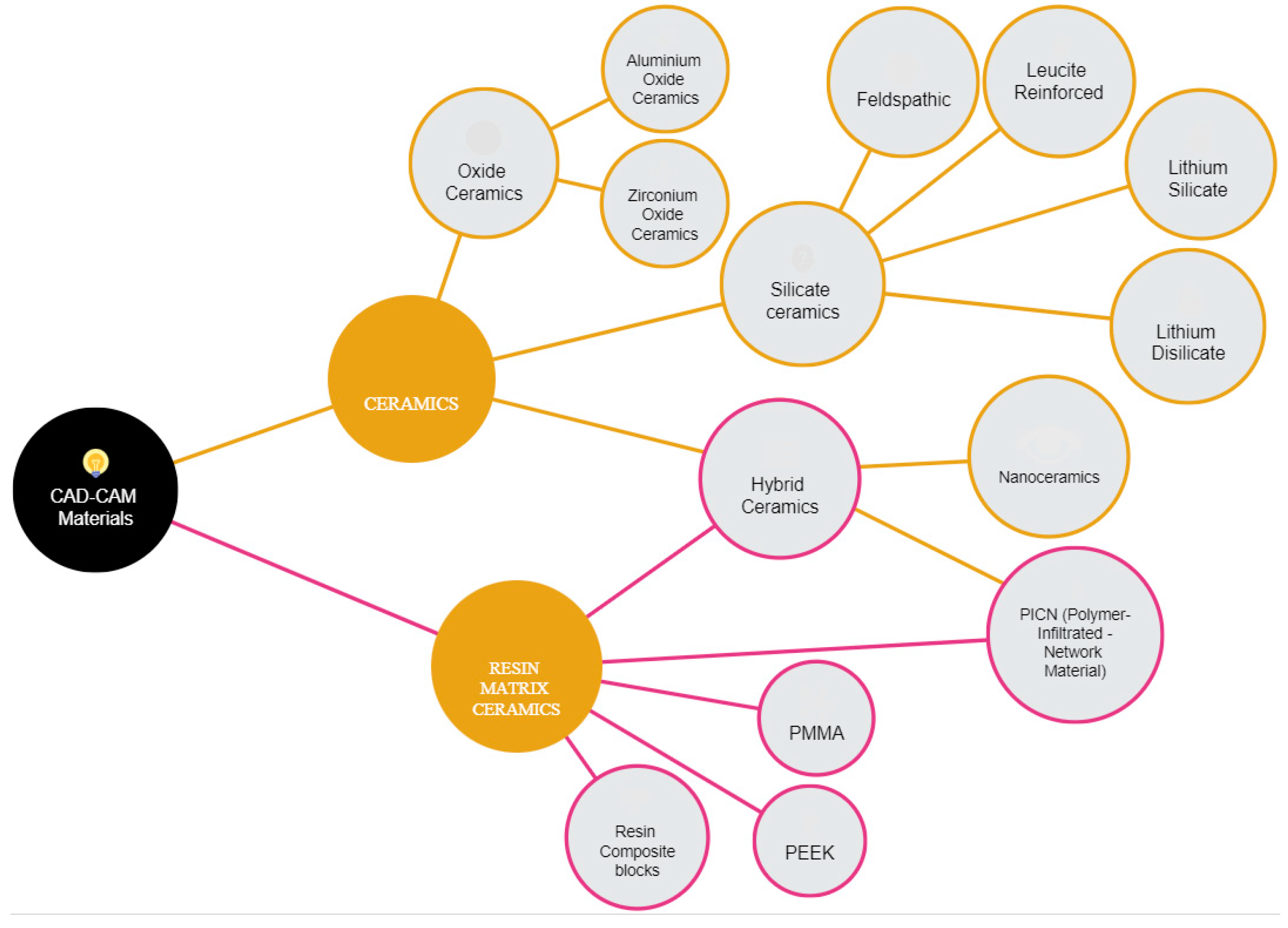

4.1. Silicate Ceramics (Glass Ceramics)

4.1.1. Feldespathic

4.1.2. Leucite-Reinforced

4.1.3. Lithium silicate

4.1.4. Lithium Disilicate

4.2. Oxide Ceramics

4.2.1. Zirconium oxide ceramics

4.2.2. Aluminum oxide ceramics

4.3. Hybrid Ceramics

4.3.1. PICN

4.3.2. Nanoceramics

4.4. Resin Matrix Ceramics

4.4.1. PMMA

4.4.2. PEEK

4.4.3. Resin Composite Blocks (RCBs)

- -

- Tetric CAD (Ivoclar Vivadent, Liechtenstein) is a resinous matrix consisting of Bis-GMA, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA, UDMA, filled with 70% barium glass and silicon dioxide particles. This composite has a flexural strength of 273.8 MPa and an elastic modulus of 10.2 GPa [72].

- -

- LuxaCam Composite (LUXA) (DMG; Hamburg, Germany) is a resin matrix composed of 70% silicate-glass filling particles. This composite demonstrates a flexural strength of 164 MPa and an elastic modulus of 10.1 GPa. [73].

- -

- Grandio Blocks (VOCO GmbH, Germany) is a resin matrix highly nanohybrid filled (86%) with a flexural strength of 330 MPa and an elastic modulus of 18 GPa offer physical properties that mimic natural human tissues, such as thermocycling. [74-75].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barenghi, L.; Barenghi, A.; Garagiola, U.; Di Blasio, A.; Giannì, A.B.; Spadari, F. Pros and Cons of CAD/CAM Technology for Infection Prevention in Dental Settings during COVID-19 Outbreak. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, G.; Tosco, V.; Monterubbianesi, R.; Orilisi, G.; Putignano, A. A New Era in Restorative Dentistry. In The First Out-Standing 50 Years of “Università Politecnica delle Marche”: Research Achievements in Life Sciences; Longhi, S., Monteriù, A., Freddi, A., Aquilanti, L., Ceravolo, M.G., Carnevali, O., Giordano, M., Moroncini, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 319–334. ISBN 978-3-030-33832-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tapie, L.; Lebon, N.; Mawussi, B.; Fron Chabouis, H.; Duret, F.; Attal, J.P. Understanding dental CAD/CAM for restorations--the digital workflow from a mechanical engineering viewpoint. Int J Comput Dent. 2015, 18, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, K.E. We're Going Digital: The Current State of CAD/CAM Dentistry in Prosthodontics. Prim Dent J. 2018, 7, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.W.K.; Chow, T.W.; Matinlinna, J.P. Ceramic dental biomaterials and CAD/CAM technology: State of the art. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2014, 58, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadiochou, S.; Pissiotis, A.L. Marginal adaptation and CAD-CAM technology: A systematic review of restorative material and fabrication techniques. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Hotta, Y.; Kunii, J.; Kuriyama, S.; Tamaki, Y. A review of dental CAD/CAM: Current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent. Mater. J. 2009, 28, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, T.; Dent, M. Case series Clinical Results from a Long-Term Case Series using Chairside CEREC CAD-CAM Inlays and Onlays. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2008, 21, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Alghazzawi, T.F. Advancements in CAD/CAM technology: Options for practical implementation. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2016, 60, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, P.C.; Yilmaz, B.; Heshmati, R.H.; McGlumphy, E.A. Clinical performance of CAD-CAM-fabricated complete dentures: A cross-sectional study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecsei, B.; Joós-Kovács, G.; Borbély, J.; Hermann, P. Comparison of the accuracy of direct and indirect three-dimensional digitizing processes for CAD/CAM systems—An In Vitro study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2017, 61, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebieluch, W.; Mikulewicz, M.; Kaczmarek, U. Resin Composite Materials for Chairside CAD/CAM Restorations: A Comparison of Selected Mechanical Properties. J Healthc Eng. 2021, 8828954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiu, J.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U. Contemporary CAD/CAM Materials in Dentistry. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2019, 6, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, T.A. Materials in digital dentistry-A review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020, 32, 71–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuer, F.; Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D. Digital dentistry: An overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, H.; Durand, J.C.; Jacquot, B.; Fages, M. Dental biomaterials for chairside CAD/CAM: State of the art. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D. G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P. C.; Ioannidis, J. P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P. J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorulska, A.; Piszko, P.; Rybak, Z.; Szymonowicz, M.; Dobrzyński, M. Review on Polymer, Ceramic and Composite Materials for CAD/CAM Indirect Restorations in Dentistry-Application, Mechanical Characteristics and Comparison. Materials 2021, 14, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Novel zirconia materials in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2018, 97, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracis, S.; Thompson, V.P.; Ferencz, J.L.; Silva, N.R.; Bonfante, E.A. A new classification system for all-ceramic and ceramic-like restorative materials. Int J Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H. Craig's Restorative Dental Materials, 14th Ed. ed; United Kingdom, 2019; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Hinz, S.; Bensel, T.; Bömicke, W.; Henningsen, A.; Rudolph, J.; Boeckler, A.F. Impact of the Veneering Technique and Framework Material on the Failure Loads of All-Ceramic Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing Fixed Partial Dentures. Materials (Basel). 2022, 15, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addazio, G.; Santilli, M.; Rollo, M.L.; Cardelli, P.; Rexhepi, I.; Murmura, G.; Al-Haj Husain, N.; Sinjari, B.; Traini, T.; Özcan, M.; Caputi, S. Fracture Resistance of Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate Ceramic Crowns Cemented with Conventional or Adhesive Systems: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2020, 13, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavriqi, L.; Valente, F.; Murmura, G.; Sinjari, B.; Macrì, M.; Trubiani, O.; Caputi, S.; Traini, T. Lithium disilicate and zirconia reinforced lithium silicate glass-ceramics for CAD/CAM dental restorations: biocompatibility, mechanical and microstructural properties after crystallization. J Dent. 2022, 119, 104054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian Fonzar, R.; Carrabba, M.; Sedda, M.; Ferrari, M.; Goracci, C.; Vichi, A. Flexural resistance of heat-pressed and CAD-CAM lithium disilicate with different translucencies. Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials. 2017, 33, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardell, E.; Larsson, C.; von Steyern, P. V. Translucent Zirconium Dioxide and Lithium Disilicate: A 3-Year Follow-up of a Prospective, Practice-Based Randomized Controlled Trial on Posterior Monolithic Crowns. The International journal of prosthodontics 2021, 34, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traini, T.; Gherlone, E.; Parabita, S.F.; Caputi, S.; Piattelli, A. Fracture toughness and hardness of a Y-TZP dental ceramic after mechanical surface treatments. Clin Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 707–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guazzato, M.; Albakry, M.; Ringer, S.P.; Swain, M.V. Strength, fracture toughness, and microstructure of a selection of all-ceramic materials. Part II. Zirconia-based dental ceramics. Dent Mater 2004, 20, 449–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaco, C.; Caldari, M.; Scotti, R.; Group, A.C.R. Clinical evaluation of tooth-supported zirconia-based fixed dental prostheses: a retrospective cohort study from the AIOP clinical research group. Int. J.Prosthodont. 2015, 28, 236–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlaja, J.; Näpänkangas, R.; Raustia, A. Outcome of zirconia partial fixed dental prostheses made by predoctoral dental students: A clinical retrospective study after 3 to 7 years of clinical service. J Prosthet Dent. 2016, 116, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Gintaute, A.; Brägger, U.; Ferrari, M.; Weber, K.; Zitzmann, N. U. Time-efficiency and cost-analysis comparing three digital workflows for treatment with monolithic zirconia implant fixed dental prostheses: A double-blinded RCT. Journal of dentistry 2021, 113, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlenz, M. A.; Skroch, M.; Schmidt, A.; Rehmann, P.; Wöstmann, B. Monitoring fatigue damage in different CAD/CAM materials: A new approach with optical coherence tomography. Journal of prosthodontic research. 2021, 65, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, F.; Mante, F.K.; Chiche, G.; Saleh, N.; Takeichi, T.; Blatz, M.B. A retrospective survey on long-term survival of posterior zirconia and porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns in private practice. Quintessence Int. 2014, 45, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Selz, C.F; Strub, J.R; Vach, K.; Guess, P.C. Long-term performance of posterior InCeram Alumina crowns cemented with different luting agents: a prospective, randomized clinical split-mouth study over 5 years. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawajiri, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Shimizu, H. PICN Nanocomposite as Dental CAD/CAM Block Comparable to Human Tooth in Terms of Hardness and Flexural Modulus. Materials. 2021, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lan, J.; Yu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Yang, X. Effect of resin composition on performance of polymer-infiltrated feldsparnetwork composites for dental restoration. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrenner, H. Multichromatic and highly translucent hybrid ceramic Vita Enamic. International journal of computerized dentistry. 2018, 21, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yano, H.T.; Ikeda, H.; Nagamatsu, Y.; Masaki, C.; Hosokawa, R.; Shimizu, H. Correlation between microstructure of CAD/CAM composites and the silanization effect on adhesive bonding. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 101, 103441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Kou, H.; Rao, J.; Liu, C.; Ning, C. Fabrication of enamel-like structure on polymer-infiltrated zirconia ceramics. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, e245–e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, A.; Bezgin, T.; Akaltan, F.; Sarı, Ş. Resin Nanoceramic CAD/CAM Restoration of the Primary Molar: 3-Year Follow-Up Study. Case Rep Dent. 2017; 3517187. [Google Scholar]

- Heck, K.; Paterno, H.; Lederer, A.; Litzenburger, F.; Hickel, R.; Kunzelmann, K.H. Fatigue resistance of ultrathin CAD/CAM ceramic and nanoceramic composite occlusal veneers. Dent Mater. 2019, 35, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amri, M.D.; Labban, N.; Alhijji, S.; Alamri, H.; Iskandar, M.; Platt, J.A. In Vitro Evaluation of Translucency and Color Stability of CAD/CAM Polymer-Infiltrated Ceramic Materials after Accelerated Aging. J Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Harbi, F.A; Ayad, N.M.; ArRejaie, A.S.; Bahgat, H.A.; Baba, N.Z. Effect of Aging Regimens on Resin Nanoceramic Chairside CAD/CAM Material. J Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Kim, Y.K.; Jang, Y.S.; Lee, J.J.; Lee, M.H.; Bae, T.S. Comparative evaluation of the mechanical properties of CAD/CAM dental blocks. Odontology. 2019, 107, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludovichetti, F.S.; Trindade, F.Z; Werner, A。; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Fonseca, R.G. Wear resistance and abrasiveness of CAD-CAM monolithic materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2018, 120, 318.e1–318.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauvahutanon, S.; Shiozawa, M.; Takahashi, H.; Iwasaki, N.; Oki, M.; Finger, W. J.; Arksornnukit, M. Discoloration of various CAD/CAM blocks after immersion in coffee. Restorative dentistry & endodontics. 2017, 42, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, S.; Cengiz, E.; Ongun, S.; Karakaya, I. The Effect of Surface Treatments on the Mechanical and Optical Behaviors of CAD/CAM Restorative Materials. J Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e496–e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Asghar, M.; Din, S.U.; Zafar, M.S. Chapter 8. In Thermoset Polymethacrylate-Based Materials for Dental Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, M.; Alp, G.; Zaimoglu, A.; Murat, S. Evaluation of flexural strength and surface properties of pre-polymerized CAD/CAM PMMA-based polymers used for digital 3D complete dentures. Int J Comput Dent. 2018, 21, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Dwairi, Z.N.; Tahboub, K.Y.; Baba, N.Z.; Goodacre, C.J. A comparison of the flexural and impact strengths and flexural modulus of CAD/CAM and conventional heat-cured polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). J Prosthodont. 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dwairi, Z.N.; Tahboub, K.Y.; Baba, N.Z.; Goodacre, C.J; Ozcan, M. A comparison of the surface properties of CAD/CAM and conventional polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). J Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidra, A.S.; Taylor, T.D.; Agar, J.R. Computer-aided technology for fabricating complete dentures: Systematic review of historical background, current status, and future perspectives. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 109, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.J.E.; Uy, C.E.; Plaksina, P.; Ramani, R.S.; Ganjigatti, R.; Waddell, J.N. Bond Strength of denture teeth to heat-cured, CAD/CAM and 3D printed denture acrylics. J. Prosthodont. 2020, 29, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalberer, N.; Mehl, A.; Schimmel, M.; Müller, F.; Srinivasan, M. CAD-CAM milled versus rapidly prototyped (3D-printed) complete dentures: An in vitro evaluation of trueness. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Limírio, J.; Gomes, J.; Alves Rezende, M.; Lemos, C.; Rosa, C.; Pellizzer, E. P. Mechanical properties of polymethyl methacrylate as a denture base: Conventional versus CAD-CAM resin - A systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murat, S.; Alp, G.; Alatalı, C.; Uzun, M. In vitro evaluation of adhesion of candida albicans on CAD/CAM PMMA-based polymers. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.; Kamposiora, P.; Papavasiliou, G.; Ferrari, M. The use of PEEK in digital prosthodontics: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health. 2020, 20, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakou, E.; Damanaki, M.; Zoidis, P.; Bakiri, E.; Mouzis, N.; Smidt, G.; Kourtis, S. PEEK high performance polymers: a review of properties and clinical applications in prosthodontics and restorative dentistry. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2019, 27, 113–21. [Google Scholar]

- Muhsin, S.A.; Wood, D.J.; Johnson, A.; Hatton, V.P. Effects of novel polyetheretherketone (PEEK) clasp design on retentive force at different tooth undercuts. J Oral Dent Res. 2018, 5, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, T.Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Akebono, H.; Iwaguro, S.; Sugeta, A.; Shimoe, S. Finite element analysis and optimization of the mechanical properties of polyetheretherketone (PEEK) clasps for removable partial dentures. J Prosthodont Res. 2020, 64, 250–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, E.E.; Aboutaleb, F.A.; Alam-Eldein, A.M. Virtual evaluation of the accuracy of fit and trueness in maxillary poly (etheretherketone) removable partial denture frameworks fabricated by direct and indirect CAD/CAM techniques. J Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 804–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, P.; Liu, H. L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L. P.; Ma, C. F.; Chen, J. H. Polyetheretherketone versus titanium CAD-CAM framework for implant-supported fixed complete dentures: a retrospective study with up to 5-year follow-up. Journal of prosthodontic research 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, C.; Hey, J.; Schweyen, R.; Setz, J.M. Accuracy of CAD-CAM-fabricated removable partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 2018, 119, 586–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoush, R.A.; Silikas, N.; Salim, N.A.; Al-Nasrawi, S.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Effect of the Composition of CAD/CAM Composite Blocks on Mechanical Properties. BioMed Res Int. 2018, 4893143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoush, R.A.; Salim, N.A.; Silikas, N.; Satterthwaite, J.D. Long-term hydrolytic stability of CAD/CAM composite blocks. Eur J Oral Sci. 2022, 130, e12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, A.S.Q.S.; Labruna Moreira, A.D.; de Albuquerque, P.P.A.C.; de Menezes, L.R.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Schneider, L.F.J. Effect of monomer type on the CC degree of conversion, water sorption and solubility, and color stability of model dental composites. Dent Mater. 2017, 33, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, G.; Camurri Piloni, A.; Nicolin, V.; Turco, G.; Di Lenarda, R. Chairside CAD/CAM Materials: Current Trends of Clinical Uses. Biology (Basel). 2021, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, A.; Wimmer, T.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Scherer, H.; Löffler, P.; Roos, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Physico Mechanical Characterization of polyetheretherketone and current esthetic dental CAD/CAM polymers after aging in different storage media. J Prosthet Dent. 2016, 115, 321–328.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterubbianesi, R.; Tosco, V.; Sabbatini, S.; Orilisi, G.; Conti, C.; Özcan, M.; Orsini, G.; Putignano, A. How Can Different Polishing Timing Influence Methacrylate and Dimethacrylate Bulk Fill Composites? Evaluation of Chemical and Physical Properties. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 1965818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, A.; Ardu, S.; Bortolotto, T.; Krejci, I. Stain susceptibility of composite and ceramic CAD/CAM blocks versus direct resin composites with different resinous matrices. Odontology. 2017, 105, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzebieluch, W.; Mikulewicz, M.; Kaczmarek, U. Resin Composite Materials for Chairside CAD/CAM Restorations: A Comparison of Selected Mechanical Properties. J Healthc Eng. 2021, 8828954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Skroch, M.; Schmidt, A.; Rehmann, P.; Wöstmann, B. Influence of Different Luting Systems on Microleakage of CAD/CAM Composite Crowns: A Pilot Study. Int J Prosthodont. 2019, 32, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichi, A.; Goracci, C.; Carrabba, M.; Tozzi, G.; Louca, C. Flexural resistance of CAD-CAM blocks. Part 3: Polymer-based restorative materials for permanent restorations. Am J Dent. 2020, 33, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, M.; Stenger, A.; Ripper, J.; Priewich, E.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U. Mechanical degradation of contemporary CAD/CAM resin composite materials after water ageing. Dental materials: official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials 2021, 37, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Focused Question (PICO) | Is there a greater range of clinical applications of CAD / CAM materials than traditional ones due to the improvement of their mechanical properties? |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Search strategy |

Population | teeth to be partially or totally rehabilitated |

| Intervention | CAD/CAM restorations. |

|

| Comparison | Conventionally manufactured restorations. | |

| Outcome | Clinical Application of these materials | |

| Materials | Clinical Application | References |

|---|---|---|

| Silicate Ceramics | ||

| Feldespathic | inlay, onlay, anterior and posterior restorations and for veneers | Sulaiman T. A. (2020) [14], Gracis, Stefano et al. (2015) [20] |

| Leucite-reinforced | veneers, inlays, onlays, and single crowns | Zhang Y et al (2018) [19], Gracis, Stefano et al. (2015) [20], H Ahmed et al. (2019) [21] |

| Lithium disilicate | veneers, inlays/onlays, single crowns or small bridges (up to 3 units) | H Ahmed et al. (2019) [21] Hinz, Sebastian et al. (2022) [22] D'Addazio, Gianmaria et al. (2020) [23] Mavriqi, Luan et al. (2021) [24] Fabian Fonzar, Riccardo et al. (2017) [25] |

| Lithium silicate | single crowns (better in anterior regions), veneers and inlays/onlays | Hinz, Sebastian et al. (2022) [22] D'Addazio, Gianmaria et al. (2020) [23] |

| Oxide Ceramics | ||

| Zirconium | bridges in anterior or posterior region, up to entire full-arch rehabilitations on implants or natural teeth | Traini, Tonino et al. (2014) [27] Guazzato, Massimiliano et al. (2004) [28] Monaco, Carlo et al. (2015) [29] Pihlaja, Juha et al. (2016) [30] Joda, Tim et al. (2021) [31] |

| Aluminum | anterior three-unit fixed dental prosthesis, crowns and for posterior rehabilitation | Schlenz, Maximiliane Amelie et al. (2021) [32] Ozer, Fusun et al. (2014) [33] Selz, Christian F et al. (2014) [34] |

| Resin Matrix Ceramics | ||

| PMMA | long term (up to one year) provisional restoration | Zafar, Muhammad Sohail (2020) [48] Hassan, M et al. (2019) [49] Arslan, Mustafa et al. (2018) [50] Al-Dwairi, Ziad N et al. (2018) [51] Al-Dwairi, Ziad N et al. (2019) [52] Bidra, Avinash S et al. (2013) [53] Choi, Joanne Jung Eun et al. (2020) [54] Kalberer, Nicole et al. (2019) [55] de Oliveira Limírio, João Pedro Justino et al. (2021) [56] Murat, Sema et al. (2019) [57] |

| PEEK | mill frameworks for dentures or FDPs, three to four-unit FDPs, telescopic restorations, implant abutments, and secondary structures associated with bar-supported prostheses | Papathanasiou, Ioannis et al. (2020) [58] Alexakou, E et al. (2019) [59] Muhsin, S.A et al. (2018) [60] Peng, Tzu-Yu et al. (2020) [61] Negm, Enas Elhamy et al. (2019) [62] Wang, Jing et al. (2021) [63] Arnold, Christin et al. (2018) [64] |

| Resin Block Composites | inlays, onlays, veneers, partial crowns, crowns, and multi-unit, up to three bridge units | Alamoush, Rasha A et al. (2018) [65] Alamoush, Rasha A et al. (2022) [66] Fonseca, Andrea Soares Q S et al. (2017) [67] Marchesi, Giulio et al. (2021) [68] Liebermann, Anja et al. (2016) [69] Monterubbianesi, Riccardo et al. (2020) [70] Alharbi, Amal et al. (2017) [71] Grzebieluch, Wojciech et al. (2021) [72] Schlenz, Maximiliane Amelie et al. (2019) [73] Vichi, Alessandro et al. (2020) [74] Wendler, Michael et al. (2021) [75] |

| Hybrid Ceramics | ||

| PICN | veneers, inlays / onlays, anterior and posterior single crowns and for implant prostheses | Kawajiri, Yohei et al. (2021) [35] Kang, Longzhao et al (2020) [36] Steinbrenner, Harald (2018) [37] Yano, Haruka Takesue et al. (2020) [38] Li, Ke et al. (2021) [39] |

| Nanoceramics | veneers, inlay / onlay, anterior and posterior single crowns, anterior and posterior bridges | Demirel, Akif et al. (2017) [40] Heck, Katrin et al. (2019) [41] Al Amri, Mohammad D et al. (2021) [42] Al-Harbi, Fahad A et al. (2017) [43] Yin, Ruizhi et al. (2019) [44] Ludovichetti, Francesco Saverio et al. (2018) [45] Lauvahutanon, Sasipin et al. (2017) [46] Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, Sevcan et al. (2019) [47] |

| Mechanical properties: | Flexural strength (MPa) | Vickers Hardness (VH) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | References | Manufacturers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate Ceramics | |||||

| Feldespathic | 97-133 | 640 ± 20 | 45 | [14,20] | CEREC Blocs, VITABLOC |

| Leucite-reinforced | 106-160 | 525-565 | 62-70 | [19-21] | IPS Empress CAD |

| Lithium disilicate | 130 | 452-731 | 58-110 | [21-25] | IPS E.max CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent) |

| Lithium silicate | 400 | up to 7000 | 70 | [22,23] | Suprinity PC (VITA Zahnfabri), Celtra Duo (Densply Sirona) |

| Oxide Ceramics | |||||

| Zirconium | 500–1200 | 12 | 210 | [27-31] | Nobelprocera Zirconia, Nobel Biocare; Lava Plus,3M ESPE |

| Aluminum | 500 | 18.3 | 206 | [32-34] | InCeram Alumina (Vita Zahnfabrik) |

| Resin Matrix Ceramics | |||||

| PMMA | 80 - 135 | 27.7411 | 2.68-3.43 | [48-57] | Telio CAD, Ivoclar Vivadent, VITA CAD-Temp MultiColor Blocks, (VITA Zahnfabrik) |

| PEEK | 165 - 185 | 26.1-28.5 | 4 | [58-64] | Juvora dental PEEK CAD/CAM- Rohling, Straumann, Bio High Performance Polymer, Bredent, Senden, Germany |

| Resin Block Composites | 80 | 65–98 | 2.8 | [65-75] | Grandio Blocks (VOCO GmbH), LuxaCam Composite (LUXA, DMG) |

| Hybrid Ceramics | |||||

| PICN | 107.8–153.7 | 204.8–299.2 | 13.0–2.2 | [35-39] | VITA ENAMIC (Vita Zahnfabrik) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).