Submitted:

16 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Organisms

2.2. Determination of Bacterial Tolerance

2.3. Mutant Selection Window

3. Results

3.1. Determination of toleance

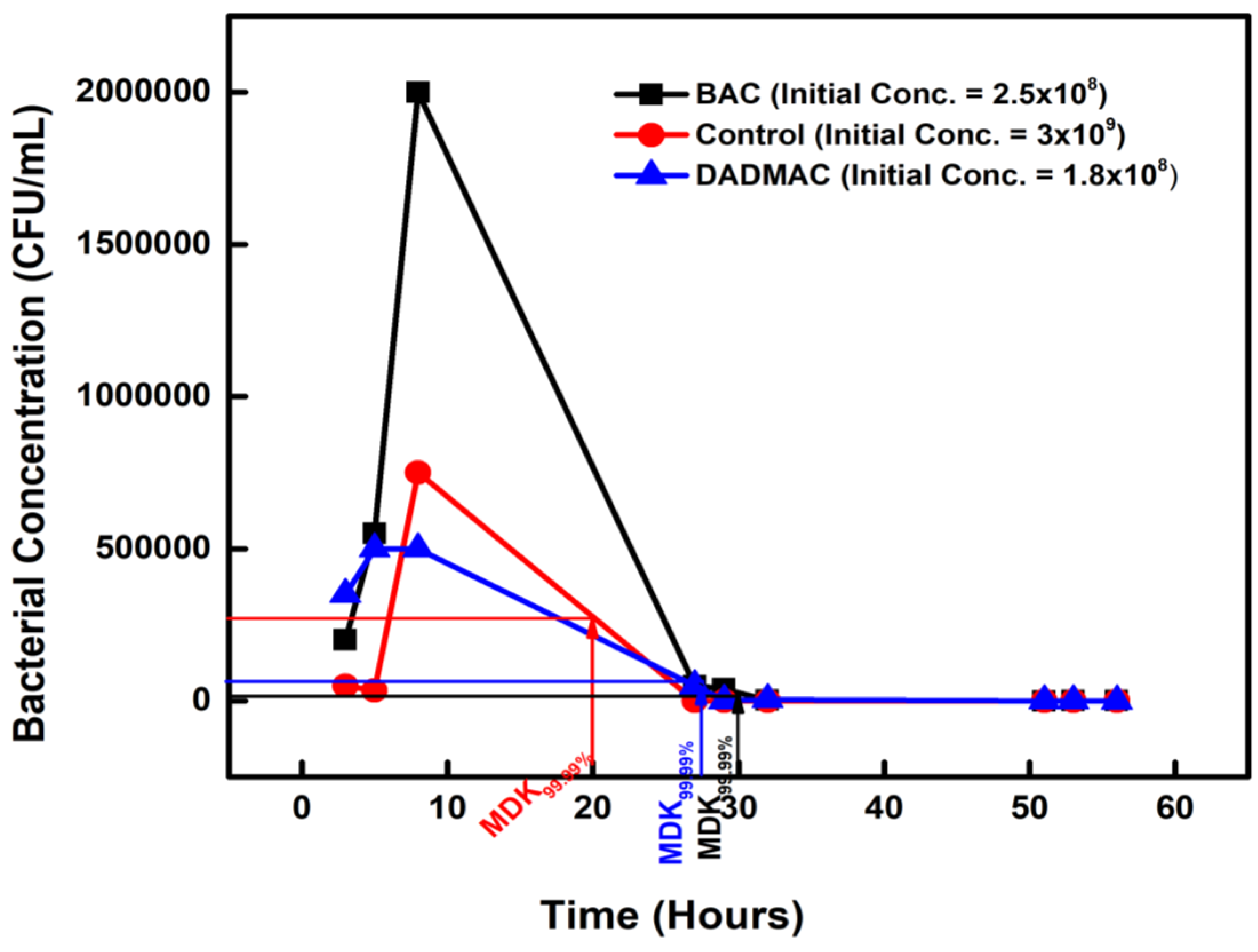

3.1.1. Tolerance among biocide-exposed isolates

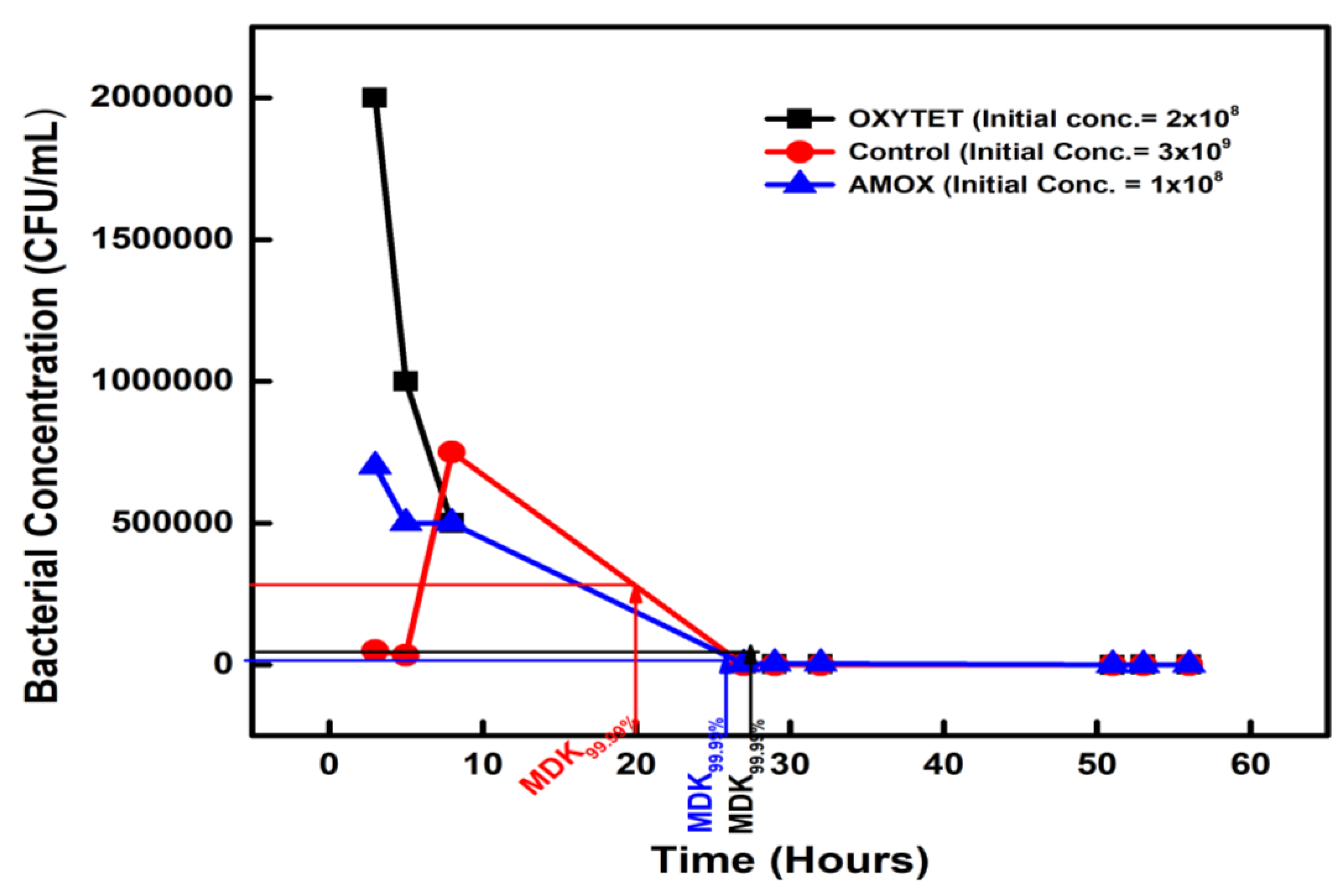

3.1.2. Tolerance among antibiotics residue exposed isolates

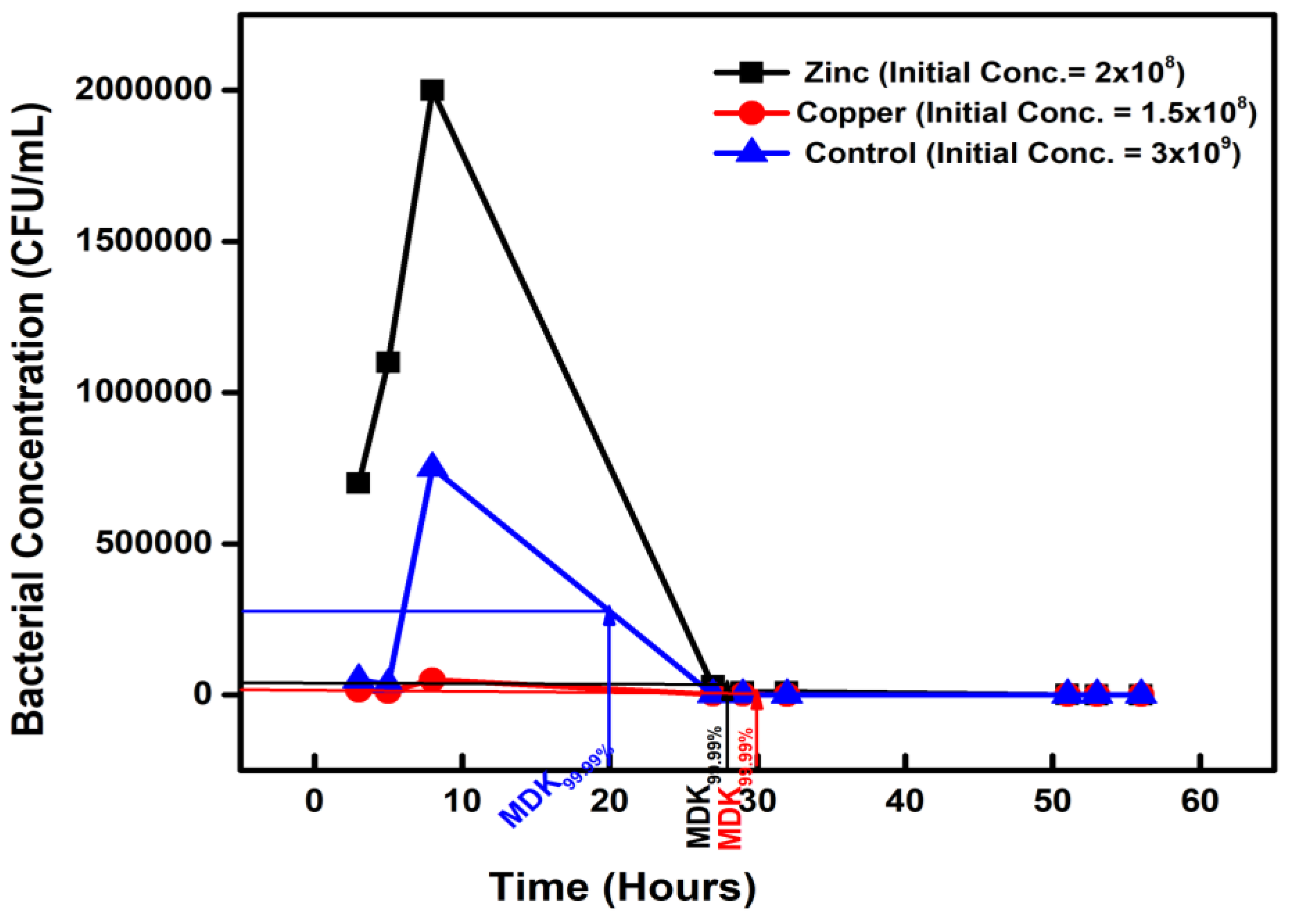

3.1.3. Tolerance among metal-exposed isolates

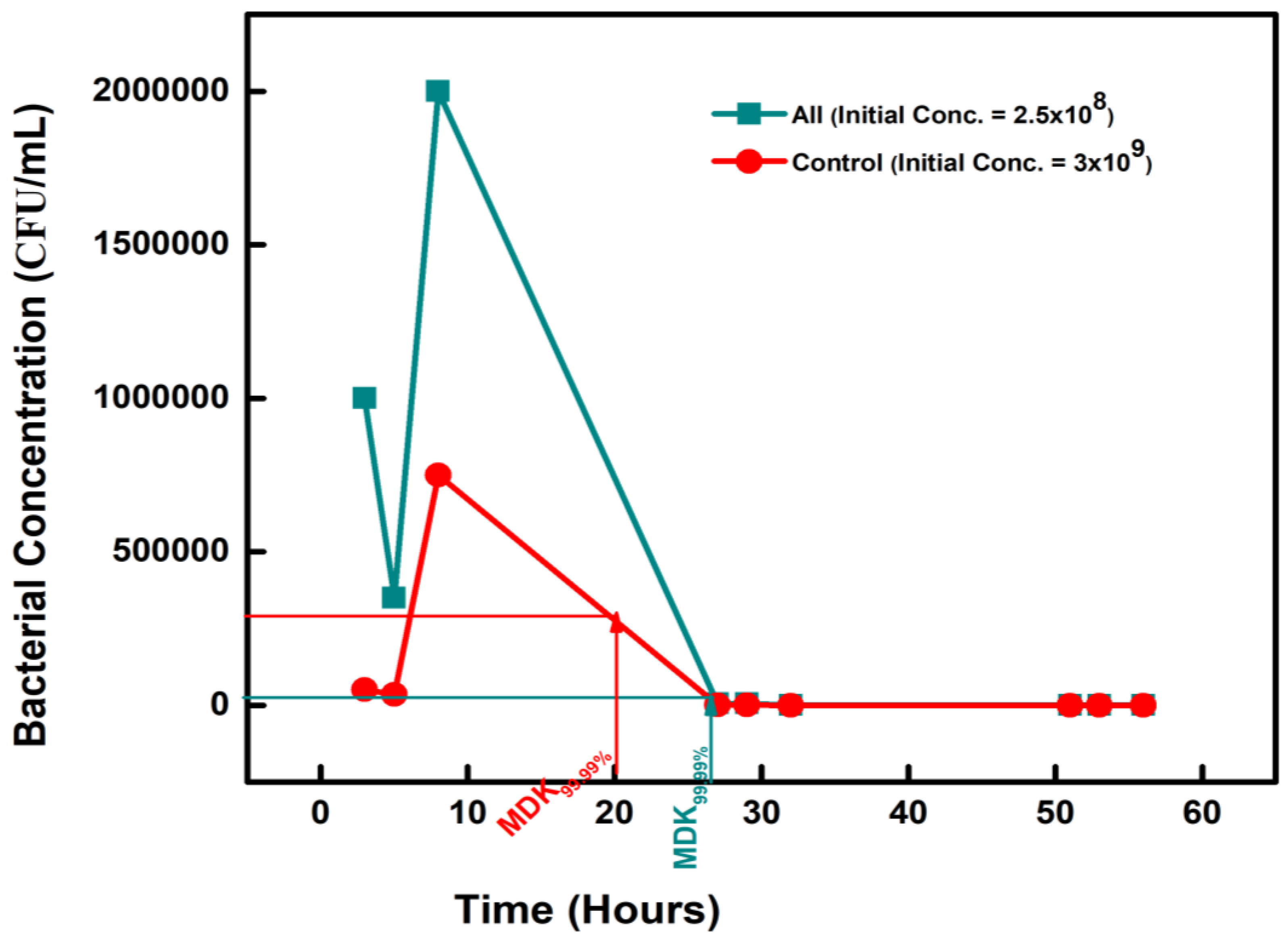

3.1.4. Tolerance for the combined chemicals-exposed isolates

3.1.5. Comparison of pollutant-treated isolates to control in the determination of the MDK99.99

3.2. Determination of the Mutant Selection Window

4. Discussion

4.1. Tolerance in exposed isolates

4.2. Effect of exposure on the mutant selection window

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, V.M.D.; King, C.E.; Kalan, L.; Morar, M.; Sung, W.W.L.; Schwarz, C.; Froese, D.; Zazula, G.; Calmels, F.; Debruyne, R.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance Is Ancient. Nature 2011, 477, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Lam, H. Evolution of Bacterial Tolerance Under Antibiotic Treatment and Its Implications on the Development of Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.S.; Peltier, G.L.; Stepanauskas, R.; McArthur, J.V. Bacterial Tolerances to Metals and Antibiotics in Metal-Contaminated and Reference Streams. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2006, 58, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, B. Van Den; Michiels, J.E.; Wenseleers, T.; Windels, E.M.; Boer, V.; Kestemont, D.; Meester, L. De; Verstrepen, K.J.; Verstraeten, N.; Fauvart, M.; et al. Frequency of Antibiotic Application Drives Rapid Evolutionary Adaptation of Escherichia Coli Persistence. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, J.E.; Lam, H. Application of Proteomics in Studying Bacterial Persistence. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2019, 16, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wood, T.K. PpGpp Ribosome Dimerization Model for Bacterial Persister Formation and Resuscitation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 523, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, A.; Maisonneuve, E.; Gerdes, K. Mechanisms of Bacterial Persistence during Stress and Antibiotic Exposure. Science (80). 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.K.; Knabel, S.J.; Kwan, B.W. Bacterial Persister Cell Formation and Dormancy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7116–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.Q.; Helaine, S.; Lewis, K.; Ackermann, M.; Aldridge, B.; Andersson, D.I.; Brynildsen, M.P.; Bumann, D.; Camilli, A.; Collins, J.J.; et al. Definitions and Guidelines for Research on Antibiotic Persistence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. Mutant Selection Window Hypothesis Updated. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngigi, A.N.; Magu, M.M.; Muendo, B.M. Occurrence of Antibiotics Residues in Hospital Wastewater, Wastewater Treatment Plant, and in Surface Water in Nairobi County, Kenya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkman, A.; Pärnänen, K.; Larsson, D.G.J. Fecal Pollution Can Explain Antibiotic Resistance Gene Abundances in Anthropogenically Impacted Environments. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; Andremont, A.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Brandt, K.K.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; Fagerstedt, P.; Fick, J.; Flach, C.F.; Gaze, W.H.; Kuroda, M.; et al. Critical Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs Related to the Environmental Dimensions of Antibiotic Resistance. Environ. Int. 2018, 117, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhao, X.; Kreiswlrth, B.N.; Drlica, K. Mutant Prevention Concentration as a Measure of Antibiotic Potency: Studies with Clinical Isolates of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2581–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau, J.M.; Zhao, X.; Hansen, G.; Drlica, K. Mutant Prevention Concentrations of Fluoroquinolones for Clinical Isolates of Streptococcus Pneumoniae. 2001, 45, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauner, A.; Shoresh, N.; Fridman, O.; Balaban, N.Q. An Experimental Framework for Quantifying Bacterial Tolerance. Biophys. J. 2017, 112, 2664–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kester, J.C.; Fortune, S.M. Persisters and beyond: Mechanisms of Phenotypic Drug Resistance and Drug Tolerance in Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 49, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, O.; Goldberg, A.; Ronin, I.; Shoresh, N.; Balaban, N.Q. Optimization of Lag Time Underlies Antibiotic Tolerance in Evolved Bacterial Populations. Nature 2014, 513, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and Broth Dilution Methods to Determine the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Antimicrobial Substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Seventh Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S27; 2017; ISBN 1562387855. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. Testing Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, J.M. New Concepts in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: The Mutant Prevention Concentration and Mutant Selection Window Approach. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcázar, J.L.; Subirats, J.; Borrego, C.M. The Role of Biofilms as Environmental Reservoirs of Antibiotic Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin-reisman, I.; Ronin, I.; Gefen, O.; Braniss, I. Antibiotic Tolerance Facilitates the Evolution of Resistance. 2017, 830, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trastoy Crossm Gastrointestinal and Respiratory Environments. 2018; 31, 1–46.

- Abdallah, M.; Benoliel, C.; Drider, D.; Dhulster, P.; Chihib, N.E. Biofilm Formation and Persistence on Abiotic Surfaces in the Context of Food and Medical Environments. Arch. Microbiol. 2014, 196, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachiyama, S.; Chan, K.L.; Liu, X.; Hathroubi, S.; Li, W.; Peterson, B. The Fl Agellar Motor Protein FliL Forms a Scaffold of Circumferentially Positioned Rings Required for Stator Activation. 2022, 119, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakooti, J.; Komeda, Y.; Matsumura, P. DNA Sequence Analysis, Gene Product Identification, and Localization of Flagellar Motor Components of Escherichia Coli. 1989, 171, 2728–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabryla, L.M.; Johnston, K.A.; Diemler, N.A.; Cooper, V.S.; Millstone, J.E.; Haig, S.J.; Gilbertson, L.M. Role of Bacterial Motility in Differential Resistance Mechanisms of Silver Nanoparticles and Silver Ions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, P.; Cabo, M.L. Tolerance Development in Listeria Monocytogenes-Escherichia Coli Dual-Species Biofilms after Sublethal Exposures to Pronase-Benzalkonium Chloride Combined Treatments. Food Microbiol. 2017, 67, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bore, E.; Hébraud, M.; Chafsey, I.; Chambon, C.; Skjæret, C.; Moen, B.; Møretrø, T.; Langsrud, Ø.; Rudi, K.; Langsrud, S. Adapted Tolerance to Benzalkonium Chloride in Escherichia Coli K-12 Studied by Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses. Microbiology 2007, 153, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, B.; Rudi, K.; Bore, E.; Langsrud, S. Subminimal Inhibitory Concentrations of the Disinfectant Benzalkonium Chloride Select for a Tolerant Subpopulation of Escherichia Coli with Inheritable Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 4101–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.; Morgan, N.; Humphreys, G.J.; Amézquita, A.; Mistry, H.; McBain, A.J. Loss of Function in Escherichia Coli Exposed to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Benzalkonium Chloride. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, I.; Rolseth, V.; Luna, L.; Rognes, T.; Bjørås, M.; Seeberg, E. Human DNA Glycosylases of the Bacterial Fpg/MutM Superfamily: An Alternative Pathway for the Repair of 8-Oxoguanine and Other Oxidation Products in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 4926–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makasheva, K.A.; Endutkin, A. V; Zharkov, D.O. Requirements for DNA Bubble Structure for Efficient Cleavage by Helix – Two-Turn – Helix DNA Glycosylases. 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromme, J.C.; Banerjee, A.; Verdine, G.L. DNA Glycosylase Recognition and Catalysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004, 14, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalow, B.J.; Courcelle, C.T.; Courcelle, J. Escherichia Coli Fpg Glycosylase Is Nonrendundant and Required for the Rapid Global Repair of Oxidized Purine and Pyrimidine Damage In Vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourahmad Jaktaji, R.; Pasand, S. Overexpression of SOS Genes in Ciprofloxacin Resistant Escherichia Coli Mutants. Gene 2016, 576, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valat, C.; Hirchaud, E.; Drapeau, A.; Touzain, F.; de Boisseson, C.; Haenni, M.; Blanchard, Y.; Madec, J.Y. Overall Changes in the Transcriptome of Escherichia Coli O26:H11 Induced by a Subinhibitory Concentration of Ciprofloxacin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porin, M.; Santiviago, C.A.; Toro, C.S.; Hidalgo, A.A.; Youderian, P.; Mora, G.C. Global Regulation of the Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium. 2003, 185, 5901–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Teng, Y.; Ou, L.; Xi, Y.; Chen, S.; Duan, G. The Resistance Mechanism of Escherichia Coli Induced by Ampicillin in Laboratory. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogol, E.B.; Rhodius, V.A.; Papenfort, K.; Vogel, J.; Gross, C.A. Small RNAs Endow a Transcriptional Activator with Essential Repressor Functions for Single-Tier Control of a Global Stress Regulon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 12875–12880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boto, A.N.; Xu, W.; Jakoncic, J.; Pannuri, A.; Romeo, T.; Bessman, M.J.; Gabelli, S.B.; Amzel, L.M. Structural Studies of the Nudix GDP-Mannose Hydrolase from E. Coli Reveals a New Motif for Mannose Recognition. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrov, A.G.; Kirillina, O.; Perry, R.D. The Phosphodiesterase Activity of the HmsP EAL Domain Is Required for Negative Regulation of Biofilm Formation in Yersinia Pestis. 2005, 247, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, U.; Jaeger, T.; Tra, B.; Sattler, J.M.; Mayer, C. Identification of a Phosphotransferase System of Escherichia Coli Required for Growth on N -Acetylmuramic Acid. 2004, 186, 2385–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heravi, K.M.; Altenbuchner, J. Cross-Talk among Transporters of the Phosphoenolpyruvate- Dependent Phosphotransferase System in Bacillus Subtilis. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitto, A.; Hottmann, I.; Stafford, G.P.; Schäffer, C. Downloaded from Http://Jb.Asm.Org/ on September 9 , 2016 by NYU LANGONE MED CTR-SCH OF MED Identification of a Novel N -Acetylmuramic Acid ( MurNAc ) Transporter in Tannerella Forsythia. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bergh, B.; Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J. Formation, Physiology, Ecology, Evolution and Clinical Importance of Bacterial Persisters. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 219–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.; Ottinger, S.; Venkat, S.; Gan, Q.; Fan, C.; Werner, C. Studying Acetylation of Aconitase Isozymes by Genetic Code Expansion. 2022, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, M.; Maerker, C.; Schu, A.; Vo, U. Oxidation of Propionate to Pyruvate in Escherichia Coli Involvement of Methylcitrate Dehydratase and Aconitase. 2002, 6194, 6184–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, L.; Gruer, M.J.; Guest, J.R. Transcriptional Regulation of the Aconitase Genes ( AcnA and AcnB ) of Escherichia Coli. 1997, 3795–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmaerts, D.; Dewachter, L.; De Loose, P.J.; Bollen, C.; Verstraeten, N.; Michiels, J. HokB Monomerization and Membrane Repolarization Control Persister Awakening. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 1031–1042.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Cho, D.H.; Heo, P.; Jung, S.C.; Park, M.; Oh, E.J.; Sung, J.; Kim, P.J.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Fumarate-Mediated Persistence of Escherichia Coli against Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2232–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, N.R.; Lobritz, M.A.; Collins, J.J. Microbial Persistence and the Road to Drug Resistance. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 13, 632–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin-Reisman, I.; Ronin, I.; Gefen, O.; Braniss, I.; Shoresh, N.; Balaban, N.Q. Antibiotic Tolerance Facilitates the Evolution of Resistance. Science (80-. ). 2017, 355, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cui, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Drlica, K.; Zhao, X. Selection of Rifampicin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus during Tuberculosis Therapy: Concurrent Bacterial Eradication and Acquisition of Resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 56, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquali, F.; Manfreda, G. Mutant Prevention Concentration of Ciprofloxacin and Enrofloxacin against Escherichia Coli, Salmonella Typhimurium and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 119, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, J.; Mao, D.; Luo, Y. Effect of the Selective Pressure of Sub-Lethal Level of Heavy Metals on the Fate and Distribution of ARGs in the Catchment Scale. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical-Exposed Isolate | Initial Concentration (CFU/mL) |

CONCENTRATION (CFU/mL) on Day 2 |

Percentage Difference | |

| BAC 12 | 2.5 × 108 | 2.5 × 104 | 30 | +50% |

| DADMAC 10 | 1.5 × 108 | 1.5 × 104 | 28 | +40% |

| AMOXICILLIN | 1 × 108 | 1 × 104 | 26 | +30% |

| OXYTETRACYCLINE | 2 × 108 | 2 × 104 | 28 | +40% |

| ZINC | 2 × 108 | 2 × 104 | 28 | +40% |

| COPPER | 1.5 × 108 | 1.5 × 104 | 26 | +30% |

| CONTROL | 3 × 109 | 3 × 105 | 20 | 0 |

| MSW Treatment | Exposure pollutant | Test Isolates | Controls | ||||

| MIC | MPC | MSW | MIC | MPC | MSW | ||

| OXYTETRACYCLIN | AMX | 2 | 256 | 0.5 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 |

| OXYTET | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | |

| COPPER | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | |

| ZINC | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | |

| BAC | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | |

| DADMAC | 0.5 | 256 | 0.5 – 256 | 0.5 | 256 | 0.5 – 256 | |

| ALL | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | 2 | 256 | 2 – 256 | |

| AMOXICILLIN | AMX | 8 | 512 | 8 - 512 | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 |

| OXYTET | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | |

| COPPER | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | |

| ZINC | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| BAC | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| DADMAC | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | 8 | 128 | 8 – 128 | |

| ALL | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| AMPICILLIN | AMX | 8 | 256 | 8 - 256 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 |

| OXYTET | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| COPPER | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| ZINC | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | 8 | 128 | 8 – 128 | |

| BAC | 8 | 512 | 8 – 512 | 8 | 128 | 8 – 128 | |

| DADMAC | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | 8 | 256 | 8 – 256 | |

| ALL | 8 | 258 | 8 – 258 | 8 | 128 | 8 – 128 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).