1. Introduction

Glaucoma is the second most common cause of blindness, affecting approximately 60 million people worldwide [

1]. Glaucoma is defined as the loss of retinal ganglion cells that causes irreparable impairment of the visual field. Although increased intraocular pressure (IOP) is a well-established risk factor for glaucoma, recent research has uncovered other key factors influencing disease onset and progression. Several studies have suggested that glaucoma progression is related to central corneal thickness (CCT) magnitude. The thinner the CCT, the more likely the glaucoma is to progress [

2,

3]. Other biomechanical properties of the cornea affect glaucoma [

4]. The corneal visualization Scheimpflug technology instrument (Corvis ST tonometry [CST]; Oculus, Wetzlar, Germany) uses an ultrahigh-speed Scheimpflug camera to quantify the biomechanical aspects of the cornea when a quick air puff is applied. As a result, the velocity of corneal deformation during the first and second applanations and the maximum depth of corneal deformation can be observed during the air puff application. Following the delivery of an air pulse, CST allows for a thorough study of corneal deformities, and the characteristics of corneal behavior observed by CST are linked to glaucoma progression [

4,

5].

Previous studies on CST parameters have mostly focused on primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) [

5,

6,

7]. Primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG) has anatomical features different from POAG [

8,

9]. This suggests that the PACG may have different CST parameters than POAG.

This study compared the CST parameters between patients with POAG and PACG.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research at Hiroshima University (E-826-4). Written consent was obtained from the patients for their information to be stored in the hospital database for use in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients

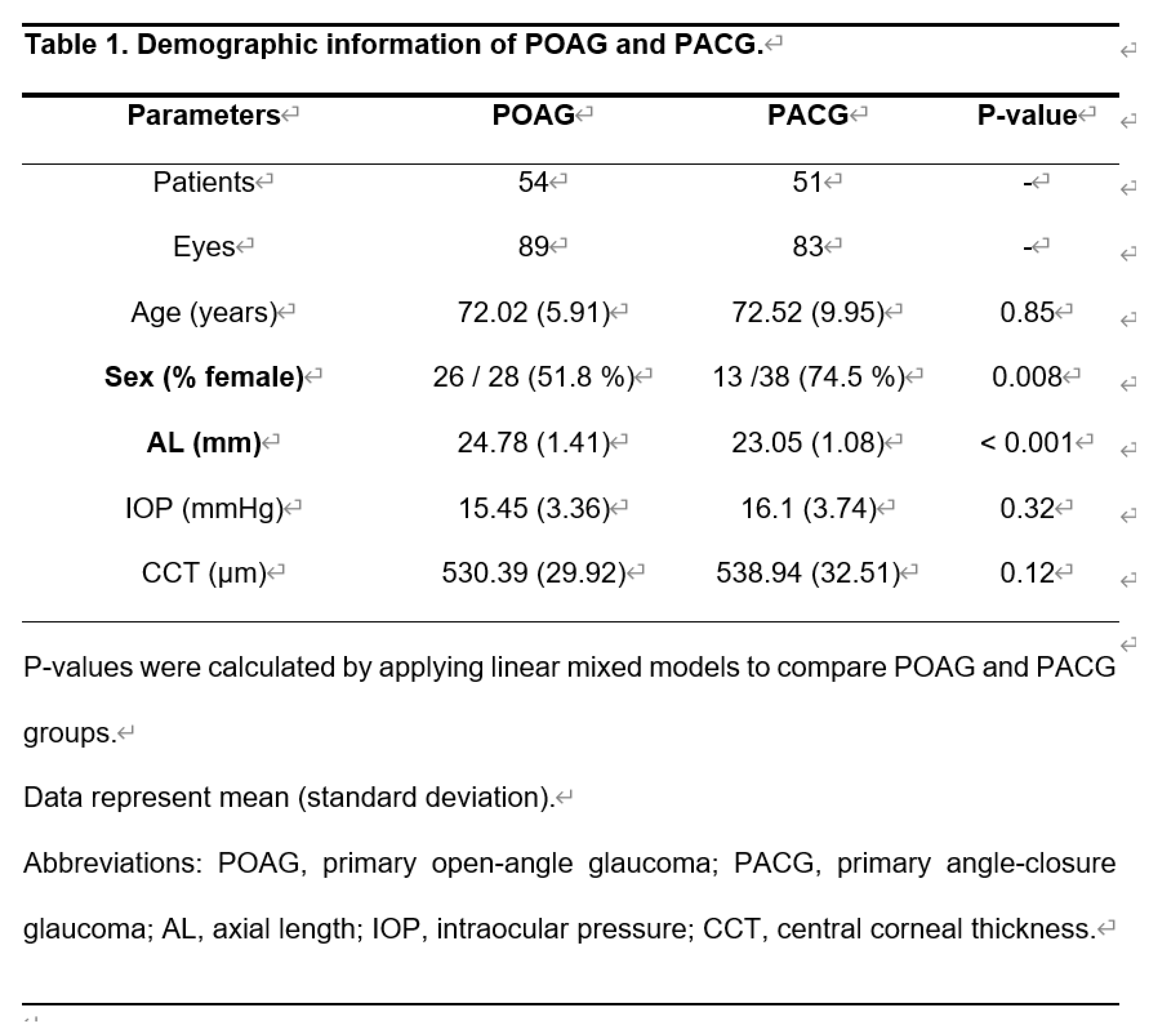

This retrospective cross-sectional study investigated 172 eyes of 105 patients (89 eyes with POAG [54 patients] and 83 eyes with PACG [51 patients]). Data were retrospectively acquired at the Hiroshima University Hospital, Saneikai Tsukazaki Hospital, and Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital between August 2019 and December 2021.

POAG was defined as (1) the presence of typical glaucomatous changes in the optic nerve head, including a rim notch with a rim width of ≦ 0.1 disc diameters or a vertical cup-to-disc ratio greater than 0.7 and/or a retinal nerve fiber layer defect with its width at the optic nerve head margin greater than a major retinal vessel, diverging in an arcuate or wedge shape, and (2) wide open angle with gonioscopy. POAG eyes with significant cataracts were excluded, except those with clinically insignificant senile cataracts on biomicroscopy.

PACG was defined as (1) the presence of angle closure, defined as at least 180°of the posterior pigmented trabecular meshwork not visible on gonioscopy in the primary position of gaze without indentation, and (2) existence of glaucomatous optic neuropathy, defined as neuroretinal rim loss with a vertical cup-to-disc ratio greater than 0.7 or between eye vertical cup-to-disc ratio asymmetry greater than 0.2, focal notching of the neuroretinal rim with a VF defect suggestive of glaucoma, or both.

Only patients aged ≥20 years were included in the study. Eyes with an IOP >25 mmHg or a history of glaucoma attacks, laser treatment, or ocular surgery, including glaucoma and cataracts, were excluded. If both eyes satisfied the inclusion criteria, the patients were included in the study.

Patients with PACG were referred from another hospital for laser or surgical treatment after receiving drug therapy only. The tests were performed before treatment.

Corvis ST tonometer measurement

The principles of CST are described in detail elsewhere [

10]. Briefly, the camera recorded a sequence of images that captured corneal deformation following a rapid air puff. The device was capable of capturing 4,330 images per second, which were analyzed to quantify CCT, deformation amplitude, applanation length, and corneal velocity. Each measurement was further classified as follows: (1) Applanation 1 (A1)/A2 time, (2) A1/2 length, (3) A1/2 velocity, and (4) A1/2 deformation amplitude.

A1/2 time was the length of time from the initiation of the air puff to the first (cornea moves inward) or second applanation (cornea moves outwards), A1/2 length was the length of the flattened cornea at the first or second applanation, A1/2 velocity was the velocity of the movement of the cornea during the first or second applanation, and A1/2 was the deformation amplitude of the movement of the corneal apex of the flattened cornea at the first or second applanation. The highest concavity (HC) time was the length of time required to reach the highest concavity from the pre-deformation of the cornea. The HC length was the length of the flattened cornea at the HC from the pre-deformation of the cornea. The HC deformation amplitude was the magnitude of movement of the corneal apex from before deformation to its HC. Peak distance (PD) was the distance between two peaks surrounding the cornea at the HC. The radius was the central curvature radius at the point of the HC Whole eye movement was the amplitude of the maximum whole eye movement. Whole eye movement time was the time of maximum whole eye movement. CST (software version 1.6r2031) was performed three times on the same day with at least a one-minute interval.

The average CST parameters were calculated from three repeated tests. All CST measurements were considered reliable according to the “OK” quality index displayed on the device monitor.

Other measurements

The axial length (AL) was measured using an IOLMaster 700 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA). IOP was measured using a Goldman applanation tonometer.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and range. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. A linear mixed model (LMM) was employed to compare the two groups in this study, considering the presence of two eyes per patient. LMM was equivalent to ordinary linear regression in that it described the relationship between predictor variables and a single outcome variable. However, standard linear regression analysis assumed that all observations were independent of each other. The measurements were nested within the patients and test points in this study; therefore, they were interdependent. Ignoring this grouping of measurements resulted in an underestimation of the standard errors of the regression coefficients. The LMM adjusted for the hierarchical structure of the data, modeling in a way in which measurements were grouped within patients to reduce the possible bias derived from the nested structure of the data [

11,

12].

Furthermore, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to correlate AL and CST parameters. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical programing language R (version 4.3.0; The Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

The demographic characteristics of eyes with POAG and PACG are shown in Table 1. The patients with POAG and PACG had similar age, IOP, and CCT values (P = 0.85, 0.32, 0.12, LMM). However, the patients with PACG had a significantly shorter AL than eyes with POAG (P <0.001, LMM) and had a significantly higher proportion of females than the POAG group (P = 0.008, chi-square test).

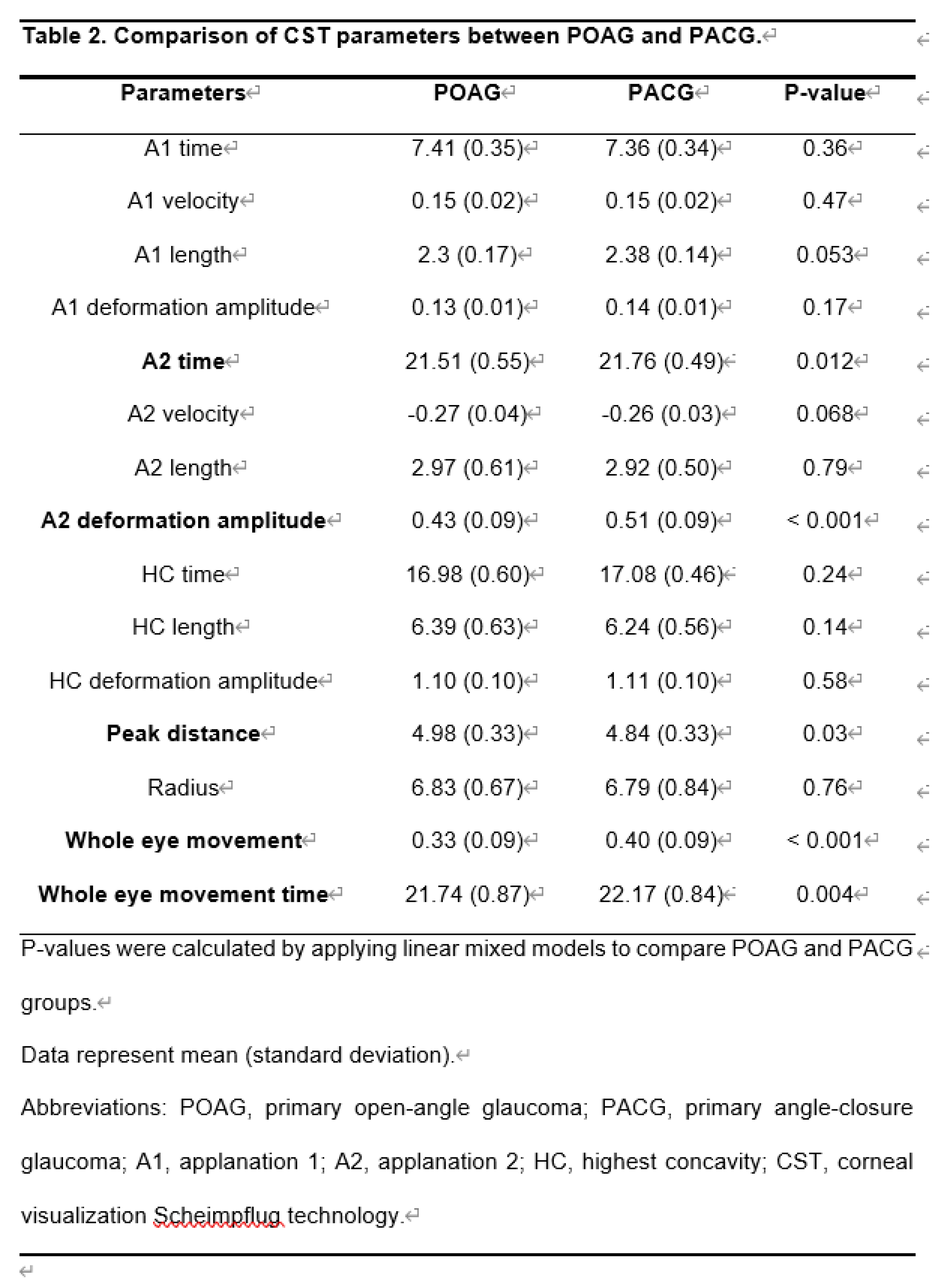

As shown in Table 2, the A2 time in eyes with PACG was significantly longer than in eyes with POAG (P = 0.012, LMM). The A2 deformation amplitude in eyes with PACG was significantly greater than in eyes with POAG (P <0.001, LMM). The PD of eyes with PACG was significantly shorter than eyes with POAG (P = 0.03, LMM). Whole eye movement in eyes with PACG was significantly longer than in eyes with POAG (P <0.001, LMM). The whole eye movement time of eyes with PACG was significantly longer than in eyes with POAG (P = 0.004, LMM).

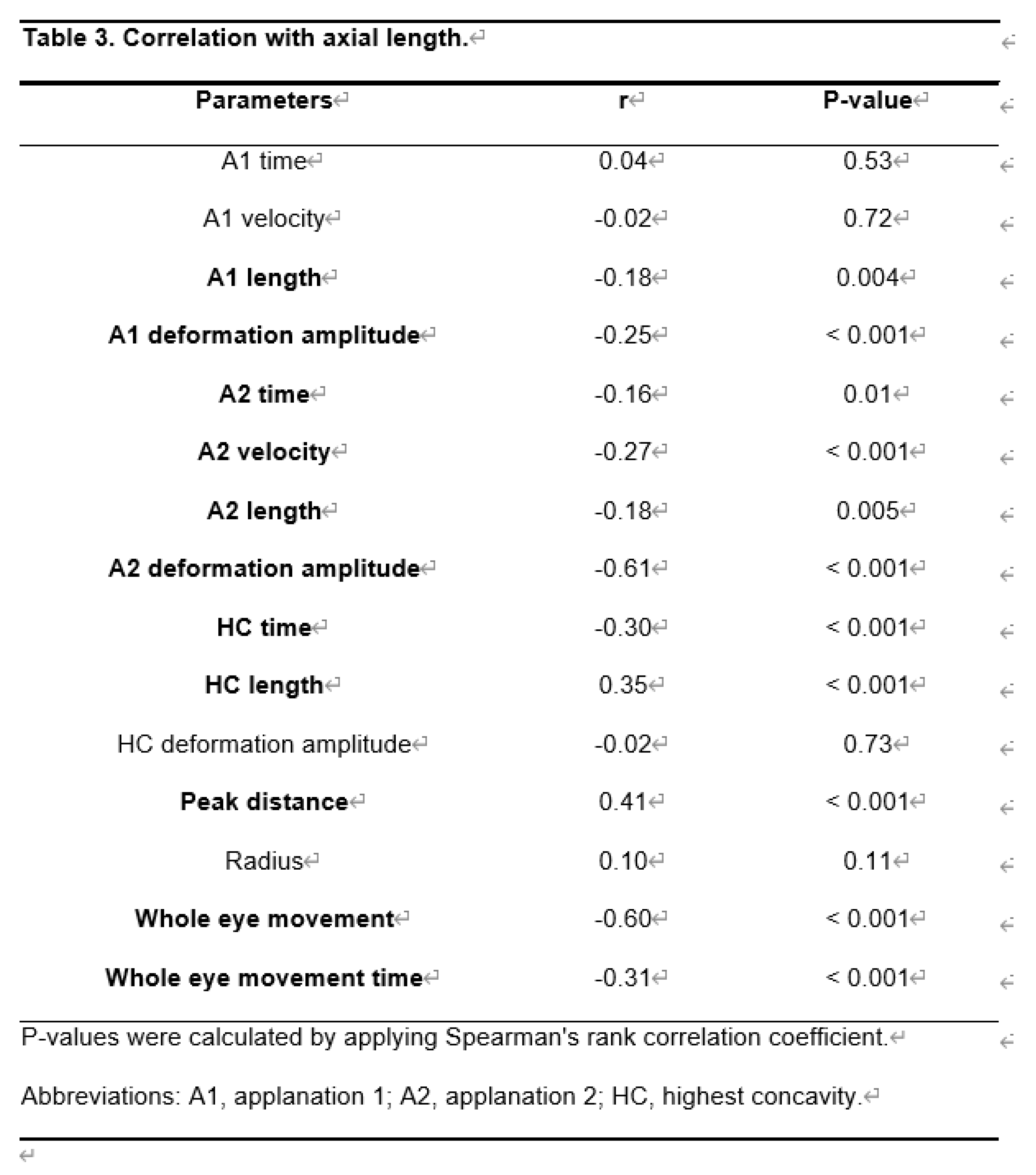

As shown in Table 3, HC length and PD had a significant positive correlation with AL (r = 0.35, P < 0.001, and r = 0.41, P <0.001, respectively). However, A1 length, A1 deformation amplitude, A2 time, A2 velocity, A2 length, A2 deformation amplitude, HC time, whole eye movement, and whole eye movement time showed a significant negative correlation with AL.

4. Discussion

We compared CST parameters between eyes with POAG and those with PACG. The PACG had a shorter AL and a higher proportion of females compared to the POAG. The backgrounds of the patients in this study were consistent with those of many previous reports [

5,

6,

13,

14]. A longer AL is more likely to deform the cornea. Higher IOP results in scant corneal deformation [

1,

15], and age resists both corneal deformation and IOP [

16].

In this study, no significant difference was observed between age and IOP. In PACG, the CCT has been reported to be significantly thicker [

17], thinner [

18], or not significantly different [

19] from POAG. Moreover, no significant differences were observed in the CCT.

Significant differences were observed between the POAG and PACG regarding the CST parameters for corneal movement. Compared to POAG, PACG had a longer A2 time, deeper A2 deformation amplitude, shorter PD, longer whole eye movement, and longer whole eye movement time.

These parameters were affected by the AL. A2 time, A2 deformation amplitude, whole eye movement, and longer whole eye movement time increased with increasing AL. The peak distance decreased with increasing AL. The difference in CST parameters between POAG and PACG was most likely due to the difference in AL.

No significant difference was observed in the CST parameters between the POAG and PACG groups when the corneal depression phase started with an air puff. A1 time is when the corneal surface first flattens after the cornea begins to depress. Non-contact tonometers convert A1 time into IOP. The fact that the A1 time, which is important for IOP measurement, was not affected by IOP and AL means that in actual clinical practice, differences in AL and disease type do not need to be considered when interpreting IOP measurement results.

Corneal biomechanics has been reported to influence glaucoma progression [

4,

20,

31]. Previous studies [

4,

20] have shown that the cornea begins to deform faster and returns from deformation with a faster progression of visual field loss. Glaucomatous visual field defects in POAG progress more rapidly in patients with corneal deformities and return quickly after being pushed into the cornea [

5,

15].

The slower the A2 time, the "deeper A2 deformation amplitude" in PACG, indicating that the return of corneal deformation was slower than that of POAG. PD is the distance between the two highest points of the cornea at the maximum depression. In a hard cornea, the peak distance is smaller than that in a soft, thin cornea at the same IOP.

A comparison of CST parameters between POAG and PACG suggests that POAG is more prone to glaucomatous neuropathy progression than PACG. However, glaucoma is a multifactorial disease, and one cannot conclude that POAG is more prone to progressive glaucomatous optic neuropathy than PACG.

PACG has been reported to have a worse prognosis than POAG, with a three-fold higher risk of blindness [

8,

25,

26,

27]. Other studies have reported faster progression rates in eyes with PACG than in POAG; therefore, PACG has a threefold greater risk of developing blindness than eyes with POAG [

2,

4,

18,

19,

28]. This may have been due to the glaucoma attacks.

Yousefi et al. [

29] excluded eyes with a history of glaucoma attacks, laser-treated eyes, and eyes with a history of cataract surgery. They examined patients with relatively stable IOP who received eye drop therapy, which may explain why no difference was observed in the progression rate between POAG and PACG. De Moraes reported a progression rate of -0.39 and -0.48 dB/year for PACG with peripheral iridectomy and POAG, respectively [

30].

No difference was observed in the shape of the optic nerve head between POAG and PACG when the degree of visual field progression was matched with the optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings. The optic nerve shape was evaluated using Heidelberg retina tomography, OCT, and nerve fiber layer (NFL) examination [

14,

22]. No difference was observed in the speed of progression of the visual field between the POAG and PACG. Although the superior half of the visual field progressed faster than the inferior half in POAG, no difference was observed between the superior and inferior halves in PACG [

23,

24].

The whole eye movement represents the backward displacement of the eyeball calculated from the corneal periphery (4 mm away from the corneal apex in each horizontal direction). Tonometry has shown that the backward displacement of the eye is greater in elderly females than in males or young adults. The fact that whole eye movement was greater in the PACG with a higher proportion of females in this study is consistent with previous reports [

21]. The eyes that move backward under air pressure for shorter distances are closely related to glaucoma [

15]. Collectively, the corneal parameters of the CST suggest that PACG is less prone to glaucoma progression than POAG.

This study had several limitations. First, we compared the CST parameters between eyes with POAG and PACG. However, the relationship between functional changes in visual field testing and morphological changes in OCT and CST parameters could not be determined. Second, most patients take antiglaucoma eye drops to control IOP and do not consider the effect of antiglaucoma eye drops on the biomechanical properties of the cornea [

32,

33]. Finally, healthy eyes were excluded.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the biomechanical properties of the cornea differed between PACG and POAG. In some parts, AL differences between the POAG and PACG groups might contribute to the variation in CST parameters.

References

- Quigley, H.A. Glaucoma. Lancet 2011, 377, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmin, C.; Thorburn, W.; Krakau, C.E. Treatment versus no treatment in chronic open angle glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol 1988, 66, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Holbach, L. Central corneal thickness and thickness of the lamina cribrosa in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005, 46, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, M.; Hirasawa, K.; Murata, H.; Nakakura, S.; Kiuchi, Y.; Asaoka, R. The usefulness of CorvisST tonometry and the ocular response analyzer to assess the progression of glaucoma. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 40798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, R.; Nakakura, S.; Tabuchi, H.; Murata, H.; Nakao, Y.; Ihara, N.; Rimayanti, U.; Aihara, M.; Kiuchi, Y. The relationship between Corvis ST tonometry measured corneal parameters and intraocular pressure, corneal thickness and corneal curvature. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, M.; Murata, H.; Nakakura, S.; Nakao, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Hirasawa, K.; Fujino, Y.; Kiuchi, Y.; Asaoka, R. The relationship between retinal nerve fibre layer thickness profiles and Corvis ST tonometry measured biomechanical properties in young healthy subjects. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miki, A.; Yasukura, Y.; Weinreb, R.N.; Yamada, T.; Koh, S.; Asai, T.; Ikuno, Y.; Maeda, N.; Nishida, K. Dynamic Scheimpflug ocular biomechanical parameters in healthy and medically controlled glaucoma eyes. J Glaucoma 2019, 28, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.Y.; Cringle, S.J.; Chen, J.; Kong, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C. Primary angle closure glaucoma: what we know and what we don't know. Prog Retin Eye Res 2017, 57, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzard, G.; Foster, P.J.; Viswanathan, A.C.; Devereux, J.G.; Oen, F.T.; Chew, P.T.; Khaw, P.T.; Seah, S.K. The severity and spatial distribution of visual field defects in primary glaucoma: a comparison of primary open-angle glaucoma and primary angle-closure glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002, 120, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprowski, R. Automatic method of analysis and measurement of additional parameters of corneal deformation in the Corvis tonometer. Biomed Eng Online 2014, 13, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J Mem Lang 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M.; Walker, S.C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.V.; Zhang, L.; Broman, A.T.; Jampel, H.D.; Quigley, H.A. Comparison of optic nerve head topography and visual field in eyes with open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, C.S.; Aquino, M.C.; Noor, S.; Loon, S.C.; Sng, C.C.; Gazzard, G.; Wong, W.L.; Chew, P.T. A prospective comparison of chronic primary angle-closure glaucoma versus primary open-angle glaucoma in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2013, 54, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, A.; Maeda, N.; Ikuno, Y.; Asai, T.; Hara, C.; Nishida, K. Factors associated with corneal deformation responses measured with a dynamic Scheimpflug analyzer. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017, 58, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuchi, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Mochizuki, H.; Takenaka, J.; Yamada, K.; Tanaka, J. Corneal displacement during tonometry with a noncontact tonometer. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2012, 56, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, S.; Torabi, H.; Hashemian, H.; Amini, H.; Lin, S. Central corneal thickness in primary angle closure and open angle glaucoma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2014, 9, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Muhsen, S.; Alkhalaileh, F.; Hamdan, M.; AlRyalat, S.A. Central corneal thickness in a Jordanian population and its association with different types of Glaucoma: cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol 2018, 18, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.E.; Lee, K.Y.; Su, D.H.; Htoon, H.M.; Ng, J.Y.; Kumar, R.S.; Aung, T. Central corneal thickness in Chinese subjects with primary angle closure glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2011, 20, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, M.; Hirasawa, K.; Murata, H.; Nakakura, S.; Kiuchi, Y.; Asaoka, R. Using Corvis ST tonometry to assess glaucoma progression. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0176380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakakura, S.; Kiuchi, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Mochizuki, H.; Takenaka, J.; Yamada, K.; Kimura, Y.; Tabuchi, H. Evaluation of corneal displacement using high-speed photography at the early and late phases of noncontact tonometry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54, 2474–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.V.; Zhang, L.; Broman, A.T.; Jampel, H.D.; s Quigley, H.A. Comparison of optic nerve head topography and visual field in eyes with open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.J.; Chaurasia, A.K.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, S.; Khanna, A.; Gupta, V. Comparison of rates of fast and catastrophic visual field loss in three glaucoma subtypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019, 60, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, S.; Sakai, H.; Murata, H.; Fujino, Y.; Matsuura, M.; Garway-Heath, D.; Weinreb, R.; Asaoka, R. Rates of visual field loss in primary open-angle glaucoma and primary angle-closure glaucoma: asymmetric patterns. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 5717–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, D.S.; Foster, P.J.; Aung, T.; He, M. Angle closure and angle-closure glaucoma: what we are doing now and what we will be doing in the future. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2012, 40, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltgen, N.; Leifert, D.; Funk, J. Correlation between central corneal thickness, applanation tonometry, and direct intracameral IOP readings. Br J Ophthalmol 2001, 85, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, S.; Sakai, H.; Murata, H.; Fujino, Y.; Garway-Heath, D.; Weinreb, R.; Asaoka, R. Asymmetric patterns of visual field defect in primary open-angle and primary angle-closure glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, C.G.; Liebmann, J.M.; Liebmann, C.A.; Susanna, R., Jr.; Tello, C.; Ritch, R. Visual field progression outcomes in glaucoma subtypes. Acta Ophthalmol 2013, 91, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.; Murata, H.; Matsuura, M.; Fujino, Y.; Nakakura, S.; Nakao, Y.; Kiuchi, Y.; Asaoka, R. The relationship between the waveform parameters from the ocular response analyzer and the progression of glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2018, 1, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, J.; Tan, H.; Cheng, Y. The comparison of the effects of latanoprost, travoprost, and bimatoprost on central corneal thickness. Cornea 2011, 30, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Sun, X. The changes of corneal biomechanical properties with long-term treatment of prostaglandin analogue measured by Corvis ST. BMC Ophthalmol 2020, 20, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).