Submitted:

13 July 2023

Posted:

14 July 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Work aims and objectives

1.3. Contribution

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1. Online Privacy and Anonymity:

2.1.1. Online Privacy

2.1.2. Online Anonymity

2.2. Anonymous Communication Networks

2.3. TOR Network

2.3.1. History of TOR

2.3.2. About TOR:

- -

- As TOR is relying on an aging (componential breakable) encryption and integrity mechanisms for which global adversaries are or will soon be able and capable of compromising. Thus, the existing pretended cryptology guarantee such as onion construction (wrapping ciphers), keys exchange protocols and the integrity and authentication checks mechanisms should be reviewed.

- -

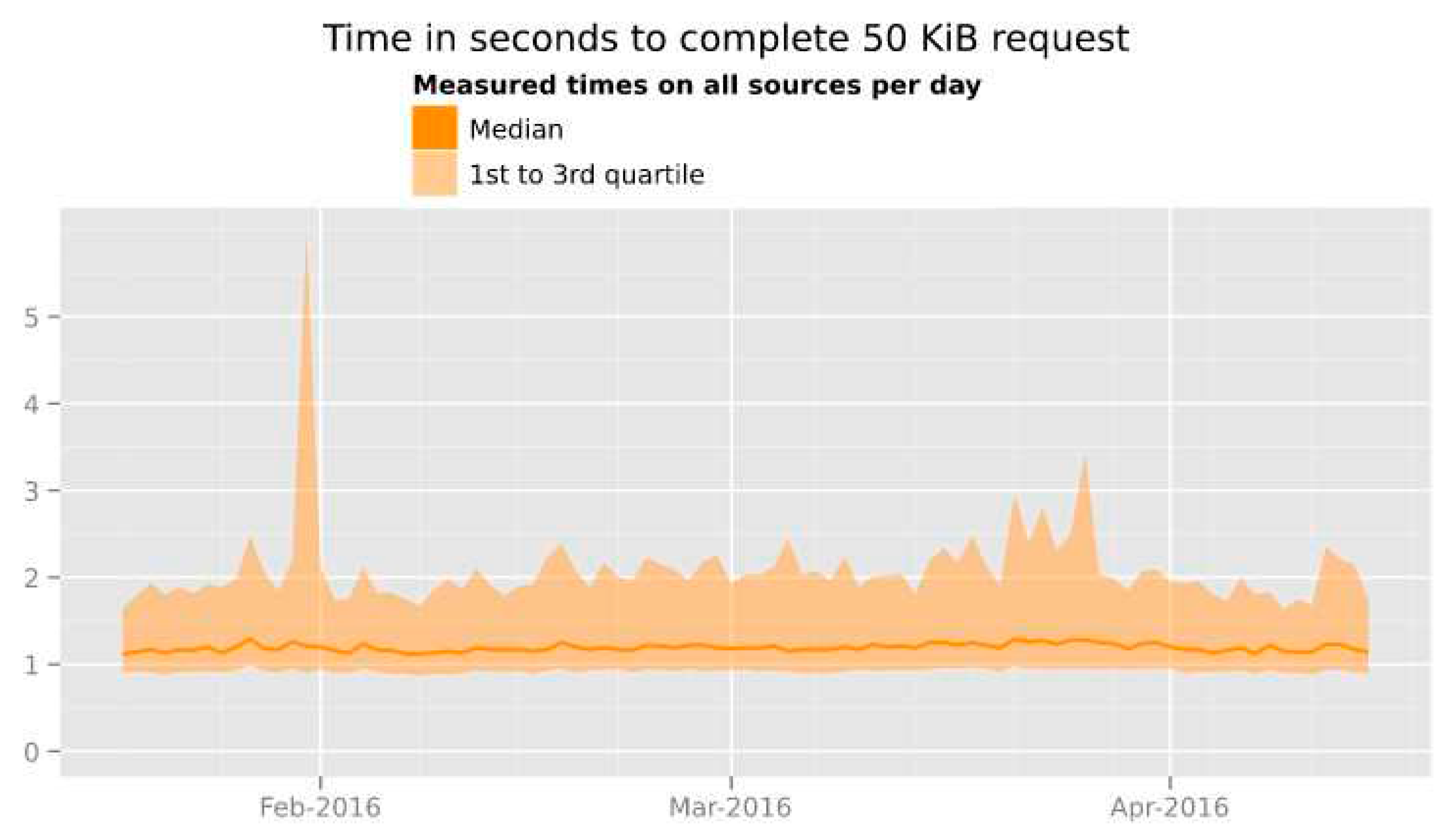

- The delays caused by the congestion on the network and also by the heavyweight encryption and decryption.

- -

- The identification of TOR user through internet and traffic analysis which leads usually to linking several intercepted communication to involved parties or linking multiple communications to a single user (Nia et al., 2014).

2.4. Legal, Social, Ethical, Professional Issues and Academic Misconduct

2.4.1. Academic misconduct, legal and ethical issues:

- -

- Research should be focused TOR and not TOR users,

- -

- Minimize users’ data collection and retention by ensuring that the data is examined directly and deleted after (seeking gather real data about should be secured),

- -

- The researchers should not disclose any identifiable data regarding TOR users acquired accidentally during their work.

- -

- Ensuring research’s legality in the country where it is performed such as the legality of network monitoring for research purposes particularly in the occidental countries where online privacy and interception laws is exceedingly complex.

2.4.2. Professional and Social issues

Chapter 3: Investigating current TOR Deployment

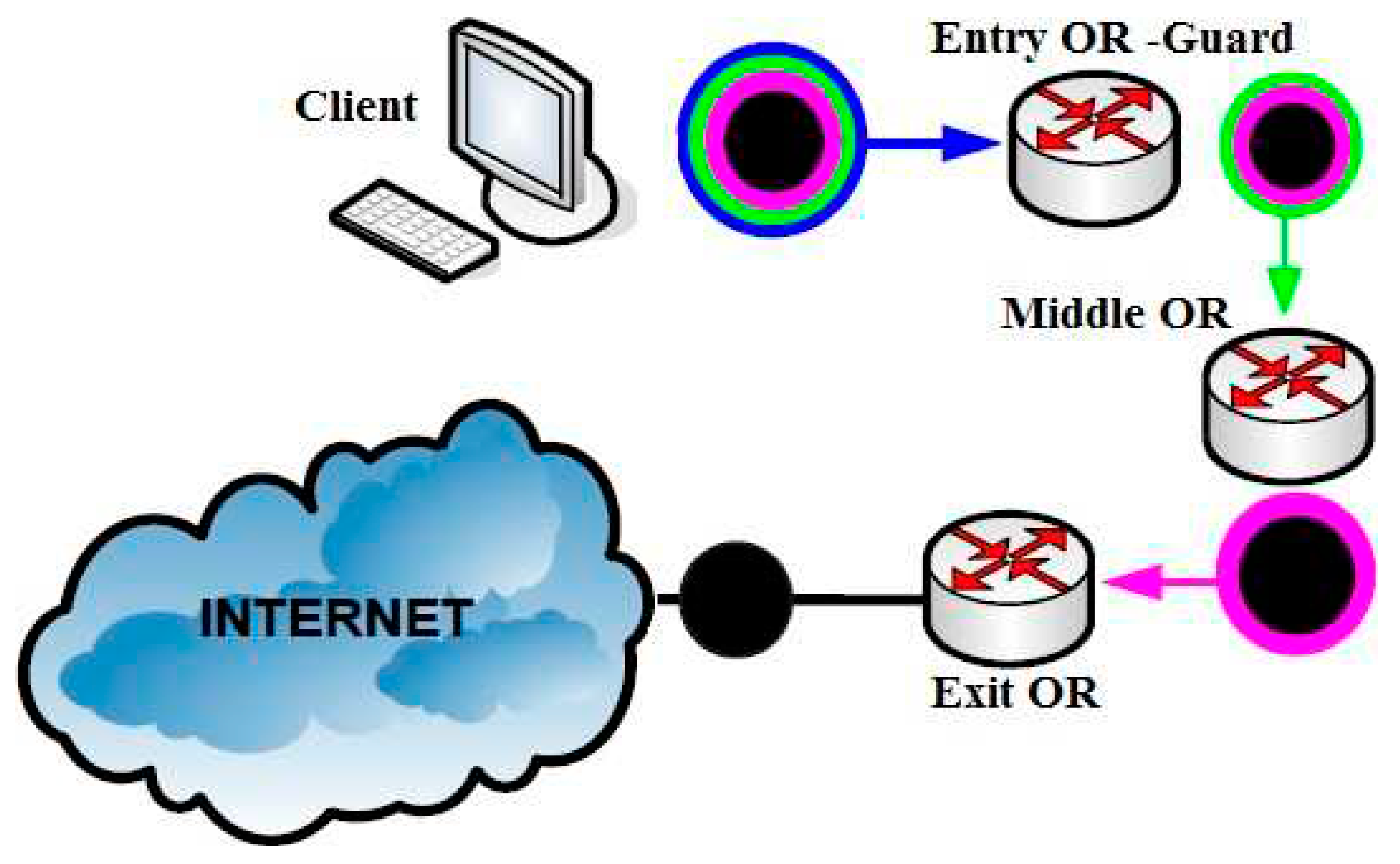

3.1. Current TOR deployment

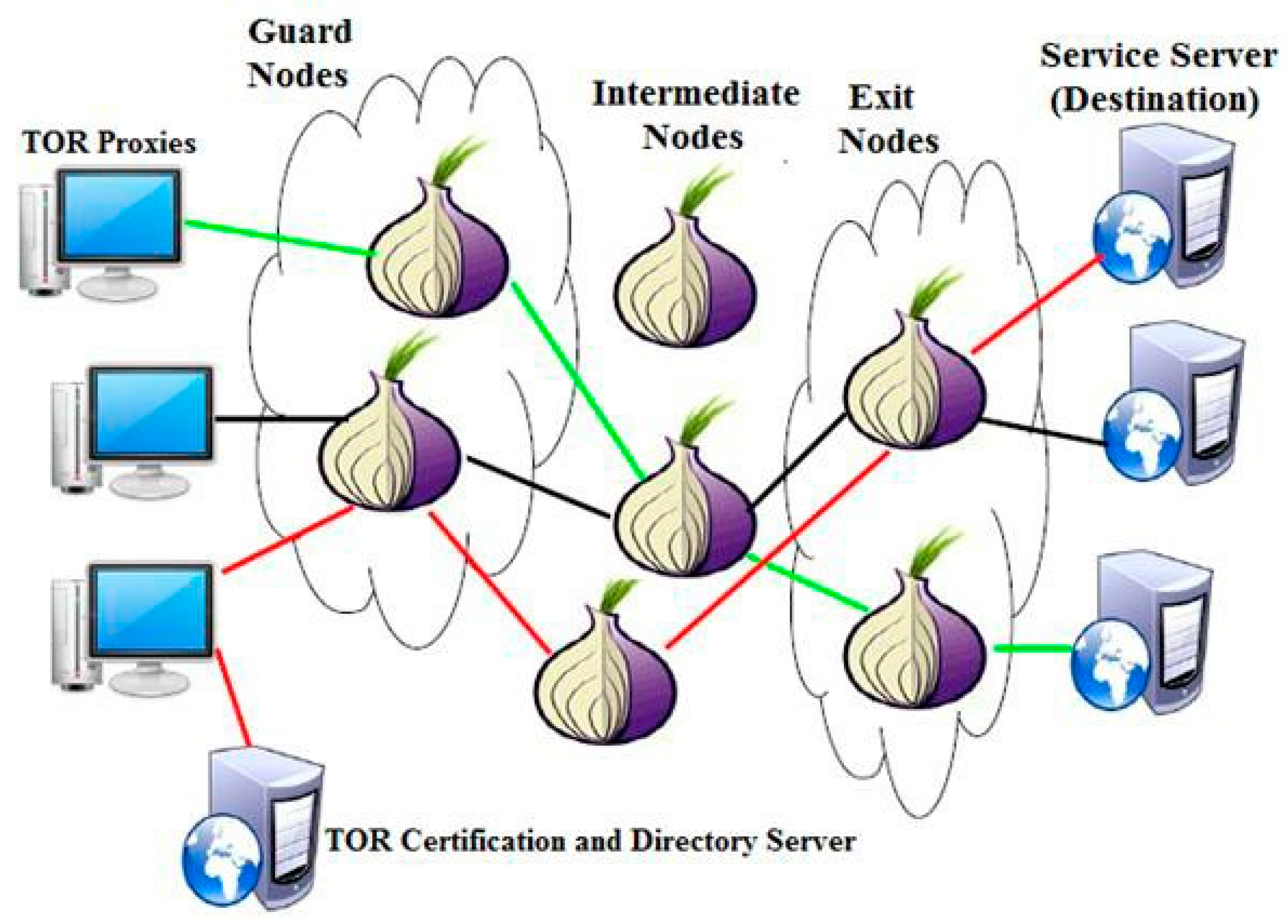

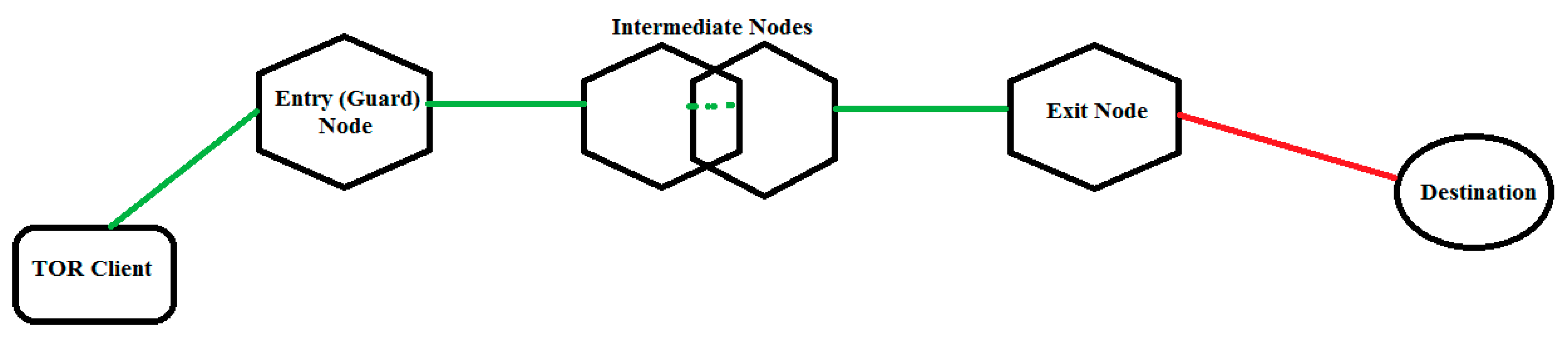

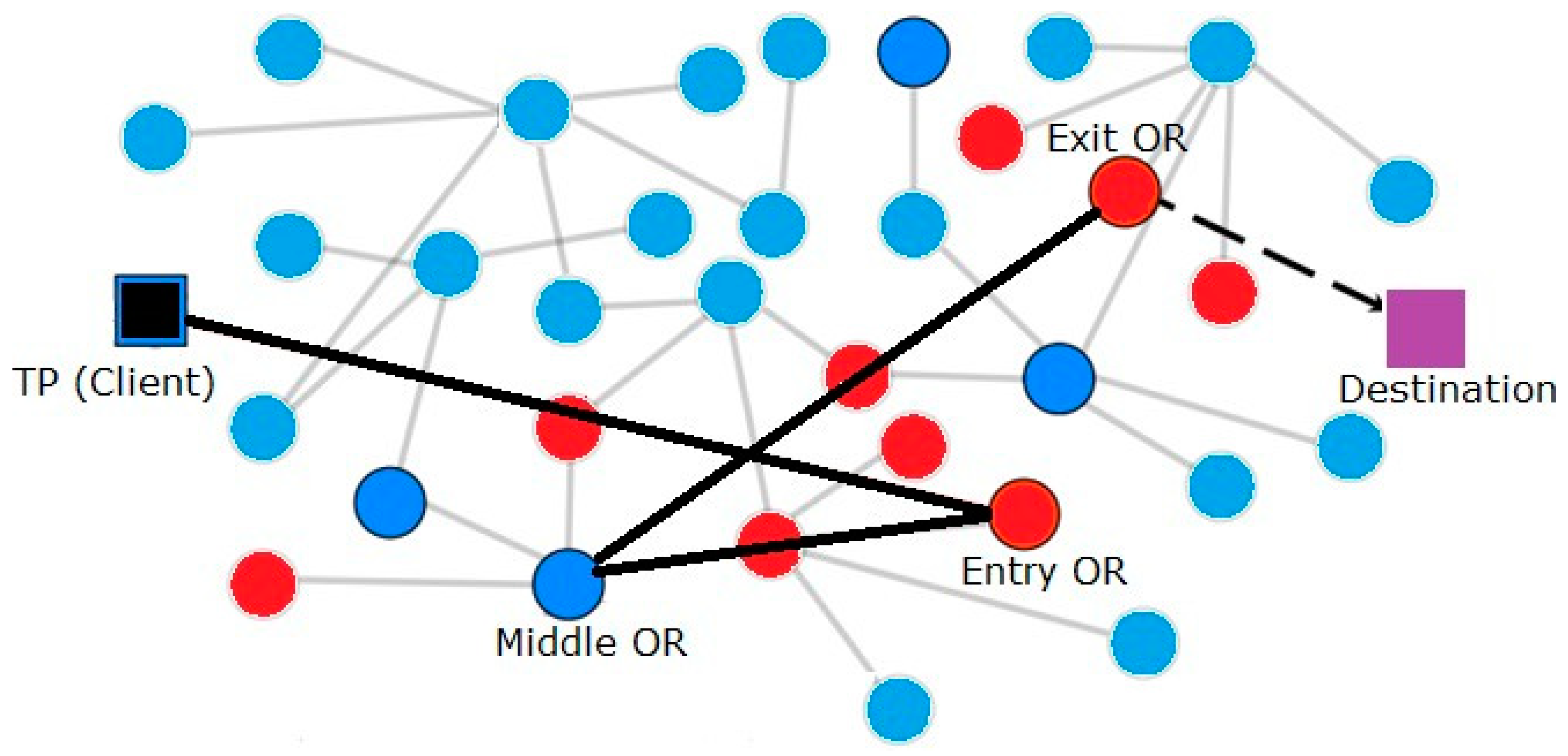

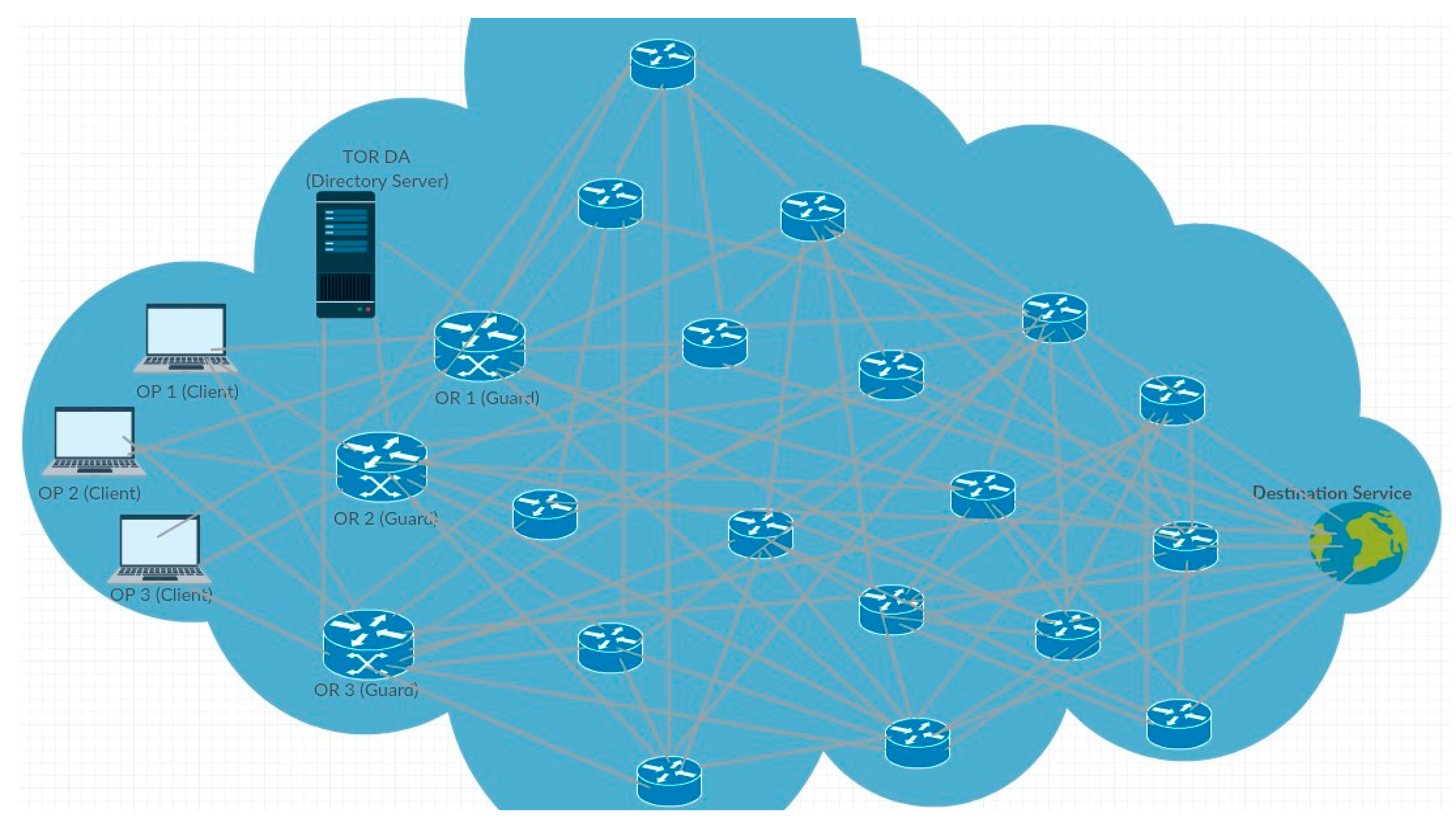

3.1.1. TOR main components

- a)

- TOR Proxies TP (also called Client)

- b)

- Destination Server

- c)

- Onion Routers (Nodes)

- d)

- Certification and Directory servers

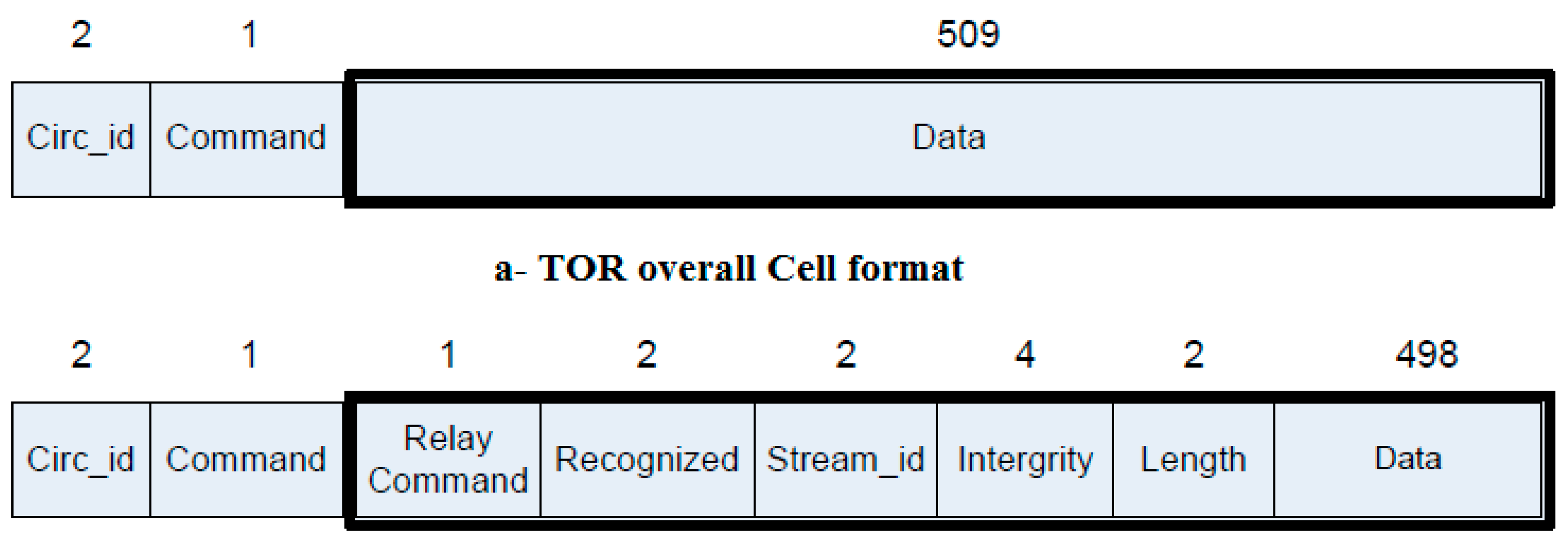

3.1.2. TOR communication mean

- a)

- Cell Header

- b)

- Cell Data

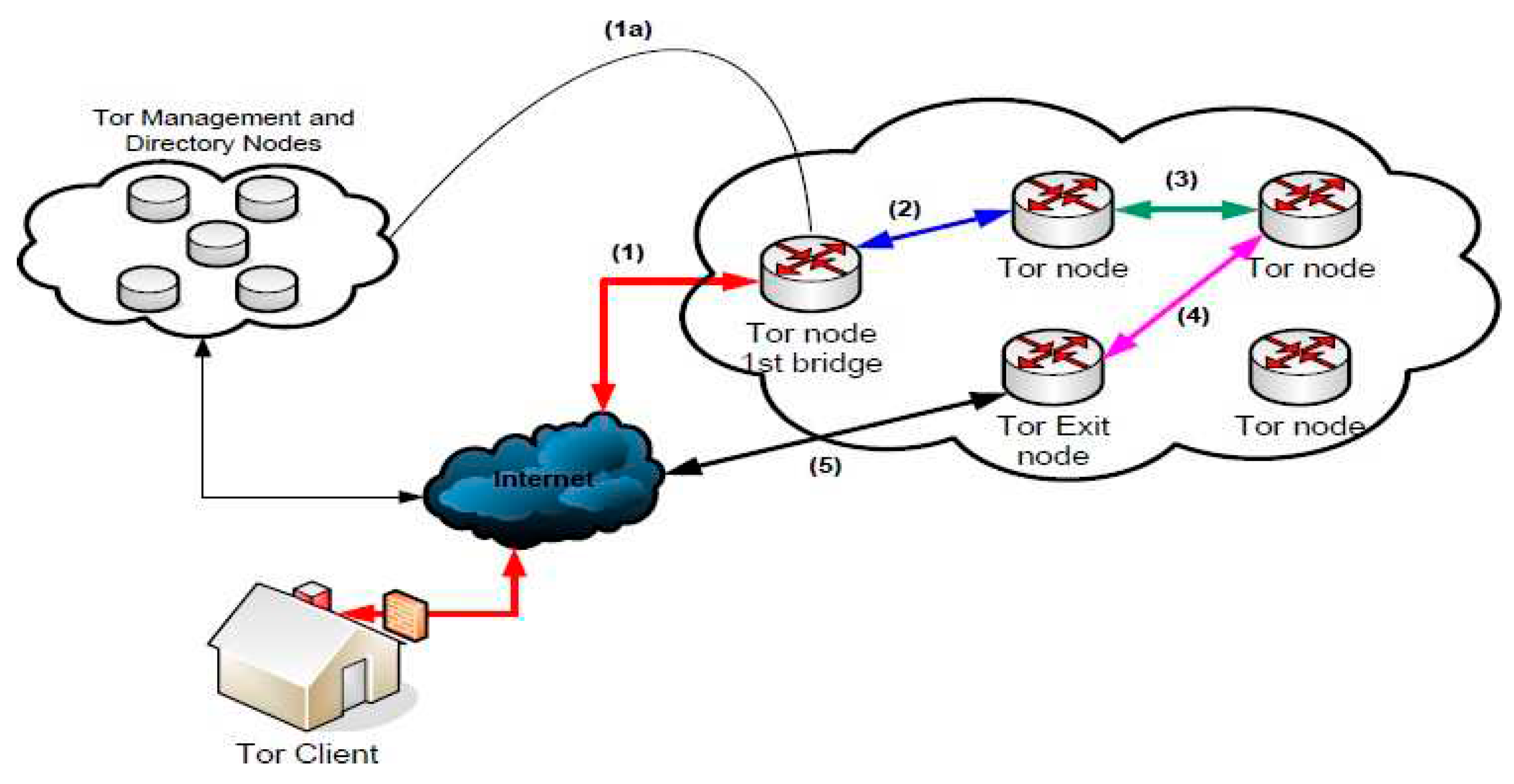

3.2. TOR working principle:

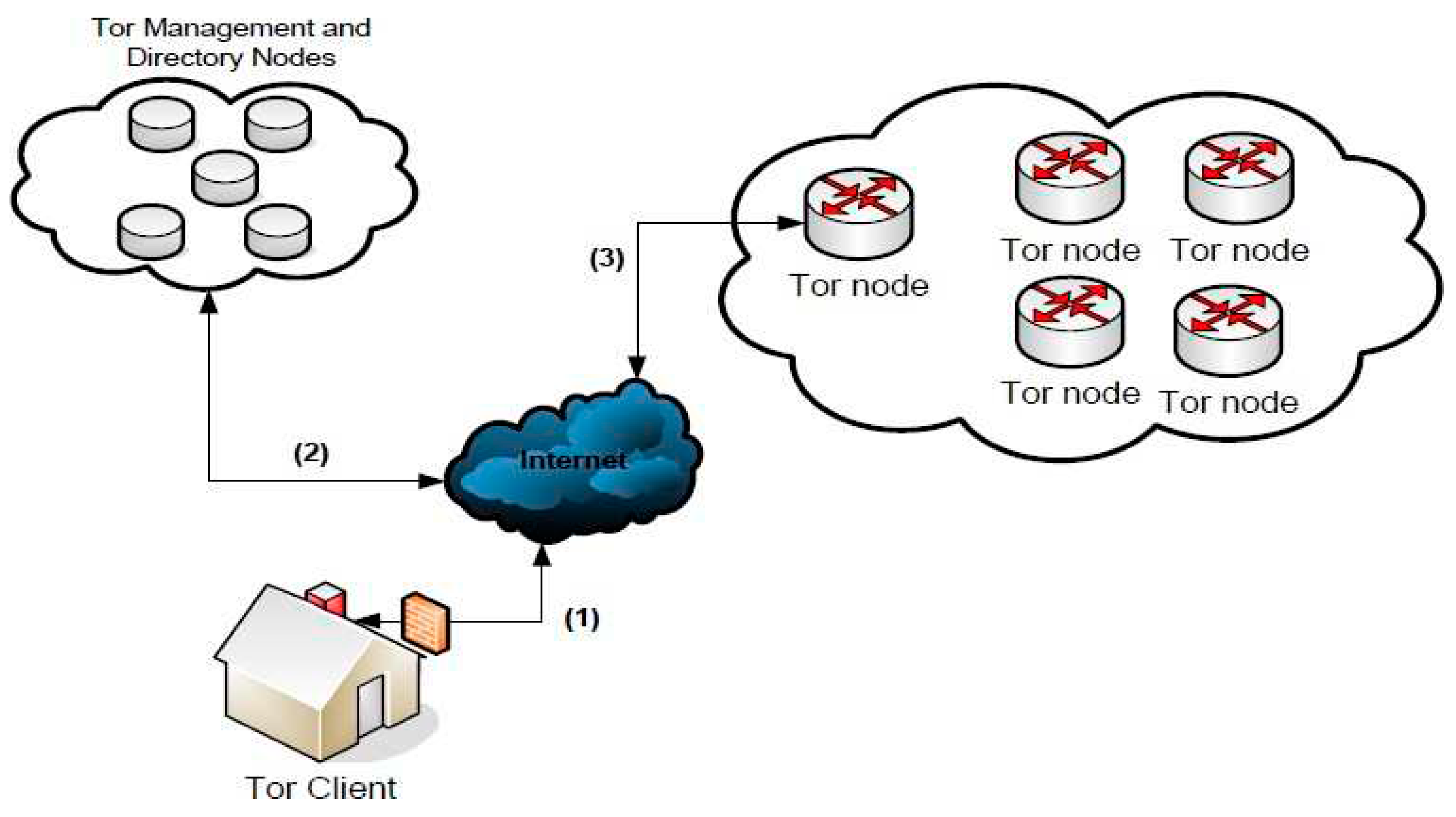

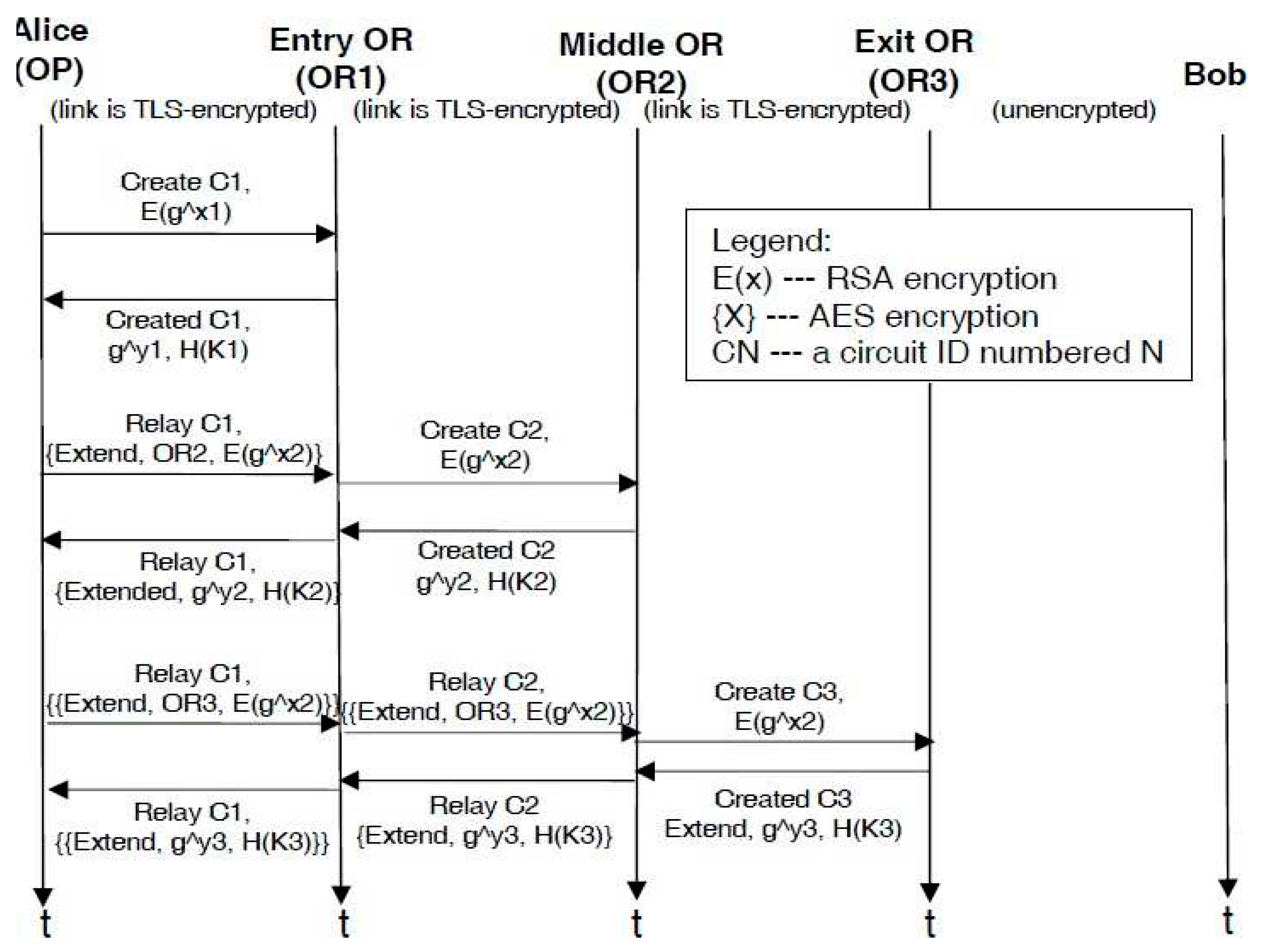

3.2.1. Acquiring, connecting and establishing circuit on TOR

3.2.2. Selecting and Creating a Circuit on TOR

3.3. Cryptography over TOR

- -

- The OP requires an Internet connection in order to able of establishing communication with the TOR network (DA),

- -

- TOR Browser downloads the information known as consensus list which include the available bridges which will be used to initiating the routing circuit establishment.

- -

- TOR establish the connection with the bridge (guard OR), using a specific handshake take place allowing the TOR directory server to authenticate itself to the client. In this phase a specific One-Way Key Exchange Authentication protocol named TAP (TOR authentication protocol) is used, this protocol is the spirit of the anonymity as it allow an authentication without asking for the client identity,

- -

- TOR client broadcast a request of creating a circuit to all live (working) ORs on the list provided by the DA and select the ones to be part of the circuit in a predefined order following the selection algorithm.

- -

- TOR client contacts the selected ORs which are part of the circuit is a secure manner to confirm the circuit and exchange keys.

- -

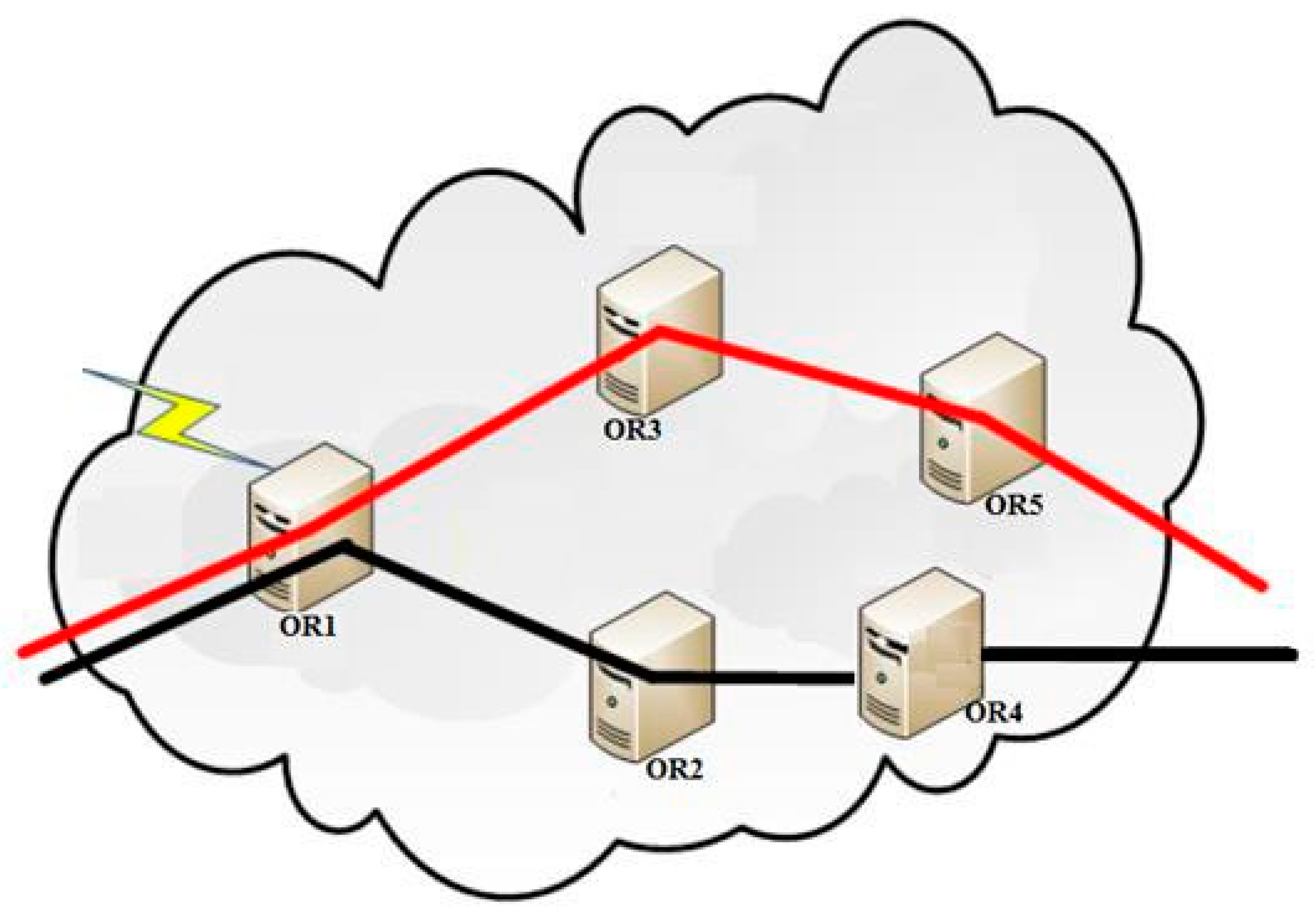

- The OP establishes a secure TLS link with the Entry (Guard) router called also bridge (OR1) using Create Cell C1 on an encrypted way using RSA and K1. The OP receive the confirmation from the OR1,

- -

- To establish the remaining part of the circuit (two remaining ORs), the OP continues on the same method by passing though OR1. In fact, The OP establishes another secure TLS encrypted link with the second router (OR2) through OR1 using Create Cell C2 in encrypted way using RSA and K2. The OP receive the confirmation of link establishment from the OR2 via OR1.

- -

- After a successful link establishment with OR2, the OP establishes the third link with the Exit router OR3 passing via OR1 and OR2 which establish the TLS encrypted link using RSA and K3. It is important to highlight that the links establishment procedure guarantee the forward secrecy (each OR is only knows the predecessor OR/client and the next OR/destination).

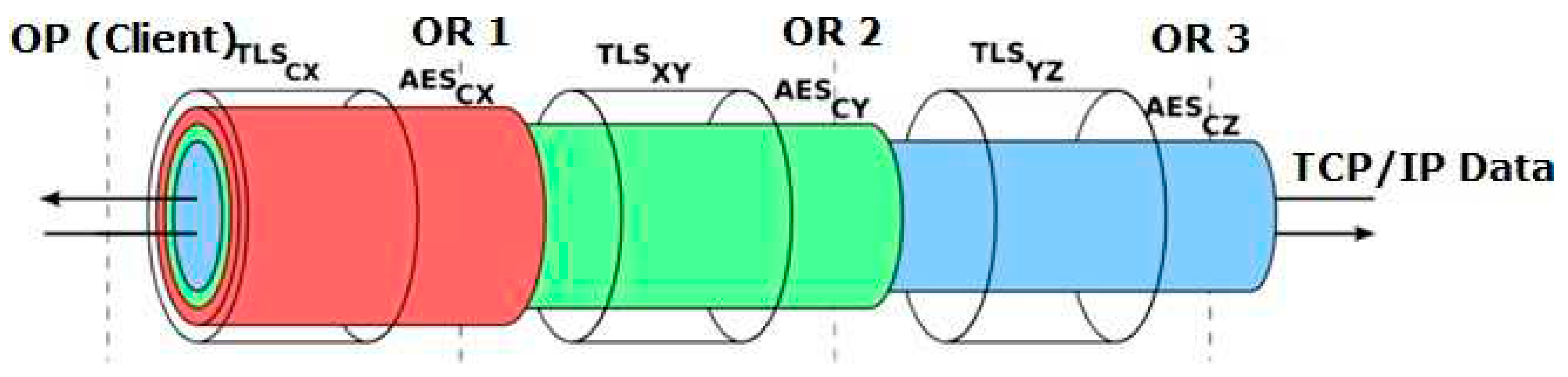

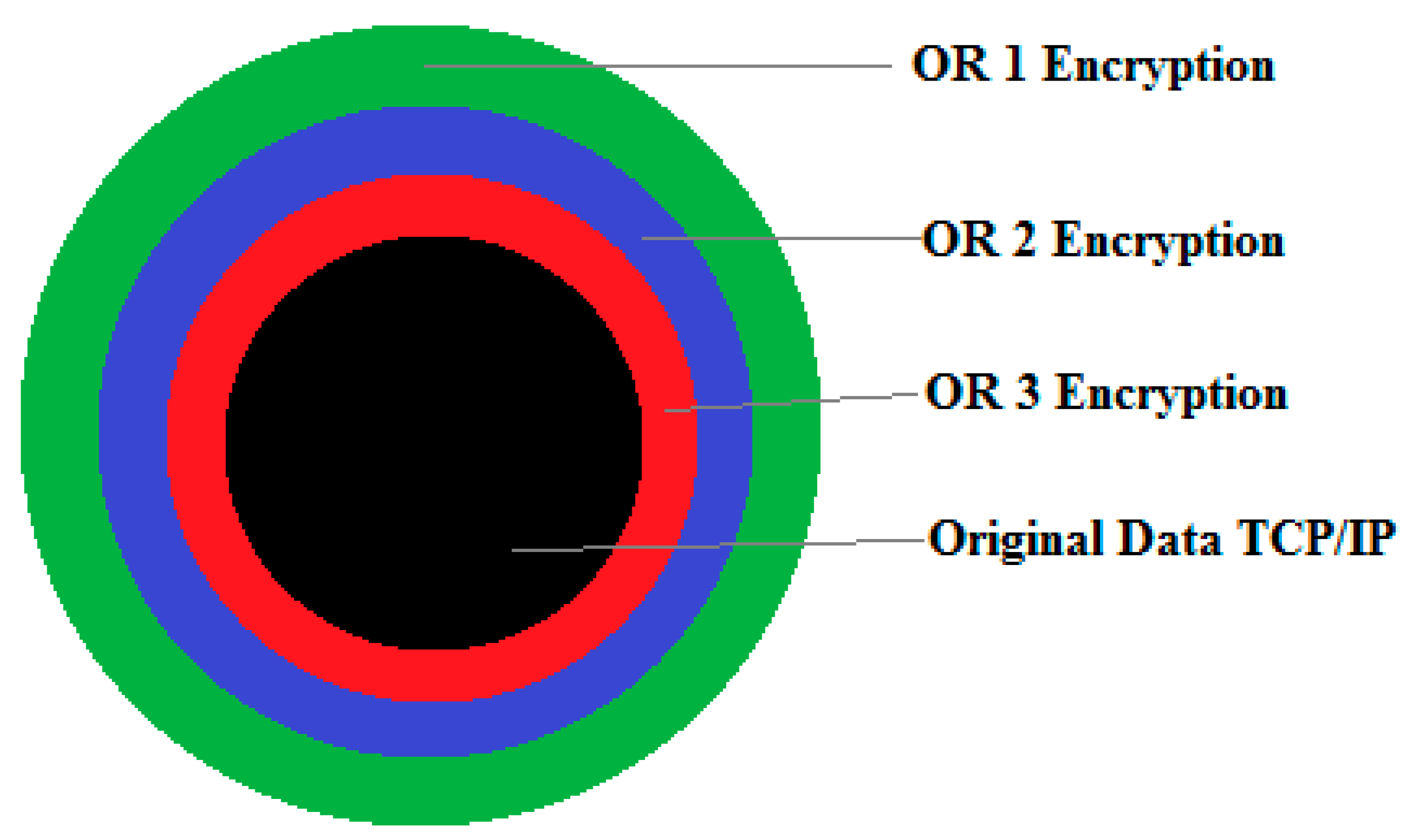

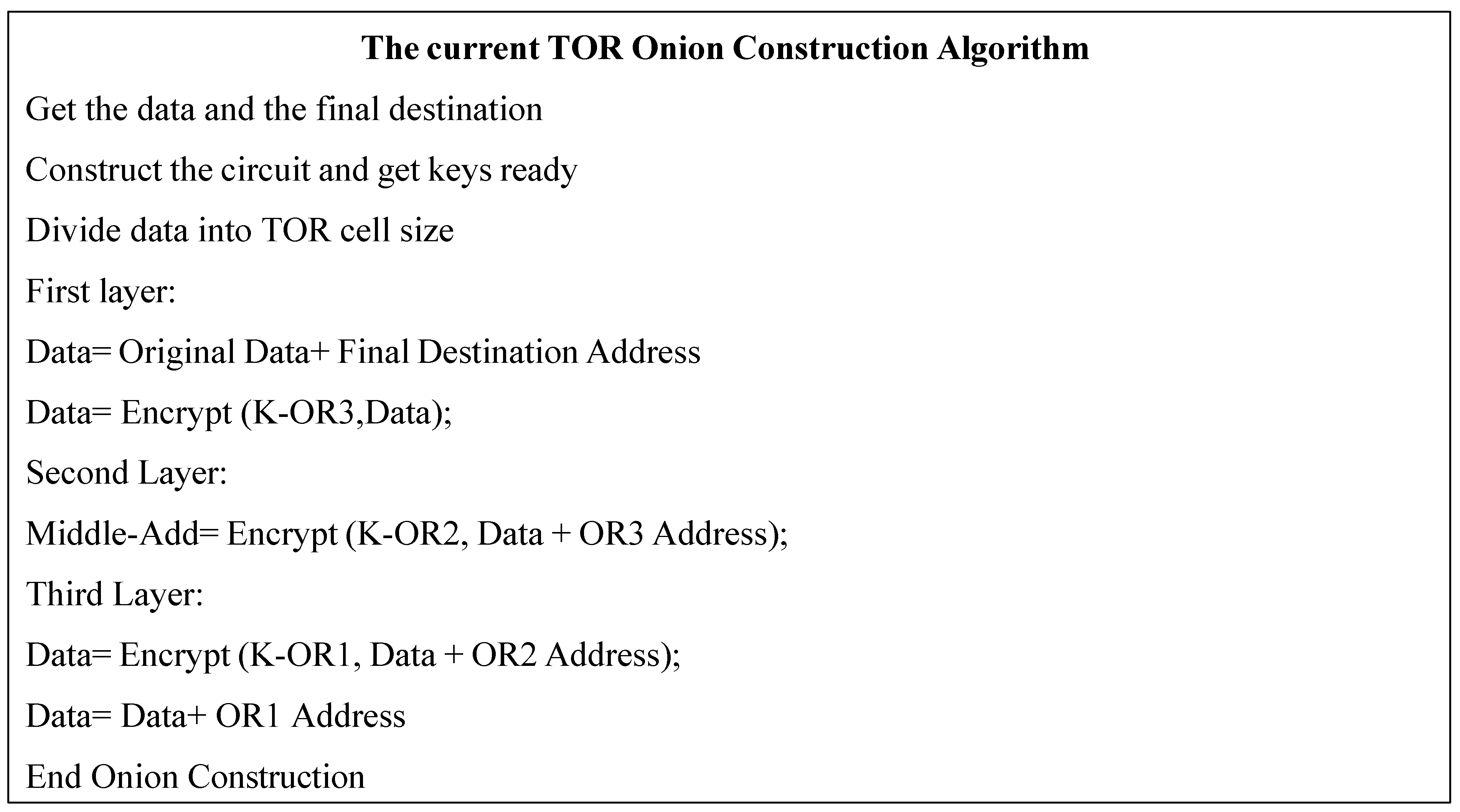

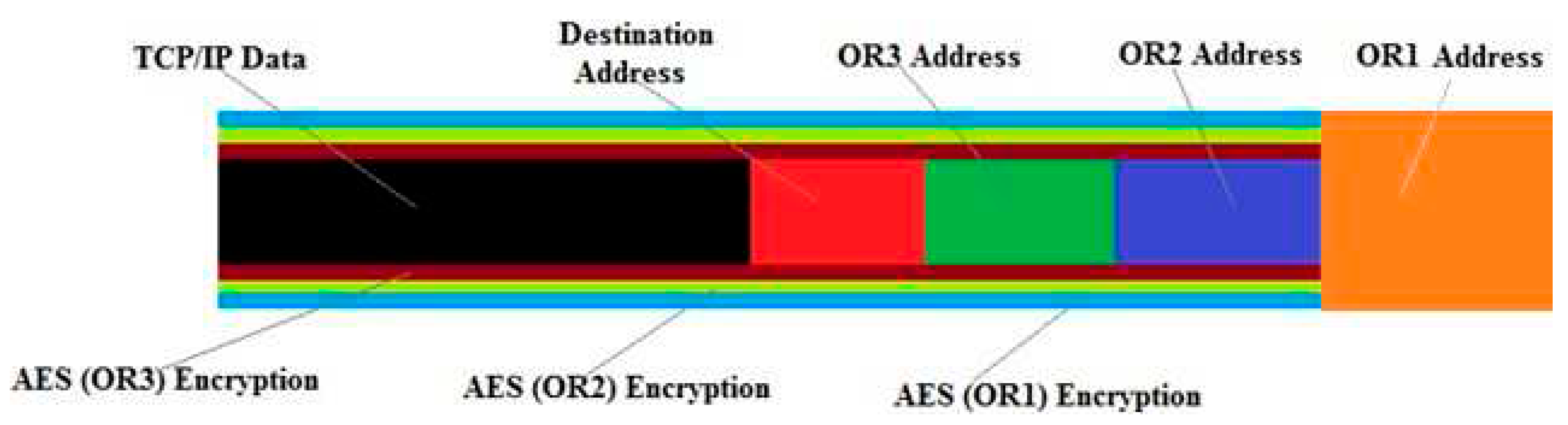

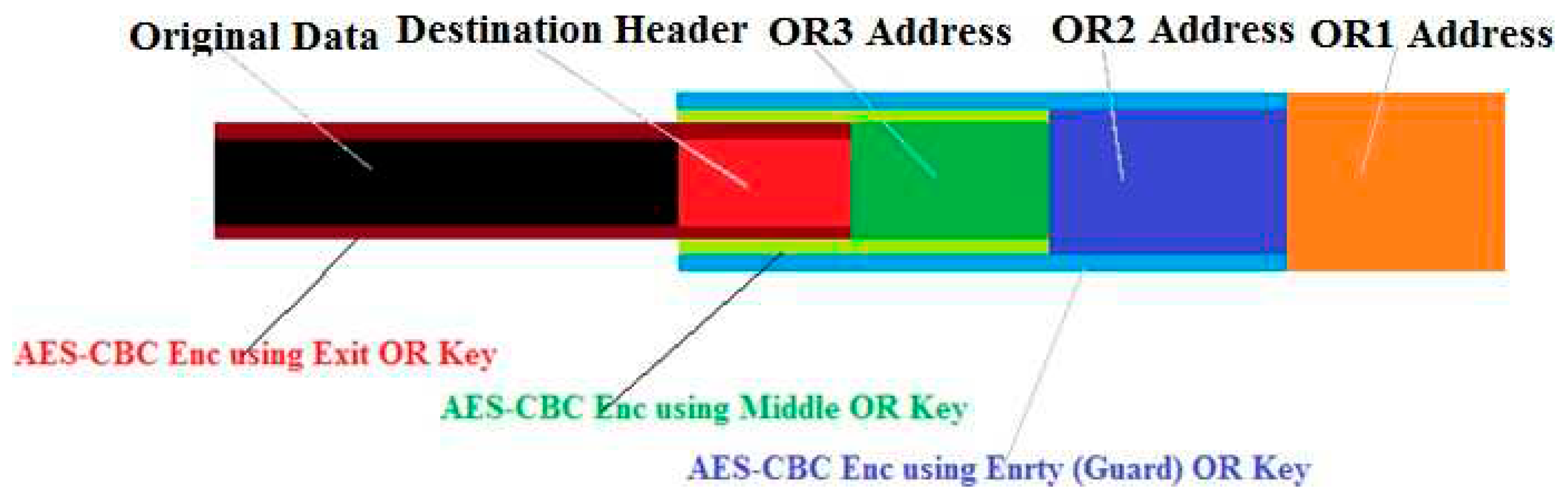

3.4. Encapsulation and multi-layer encryption

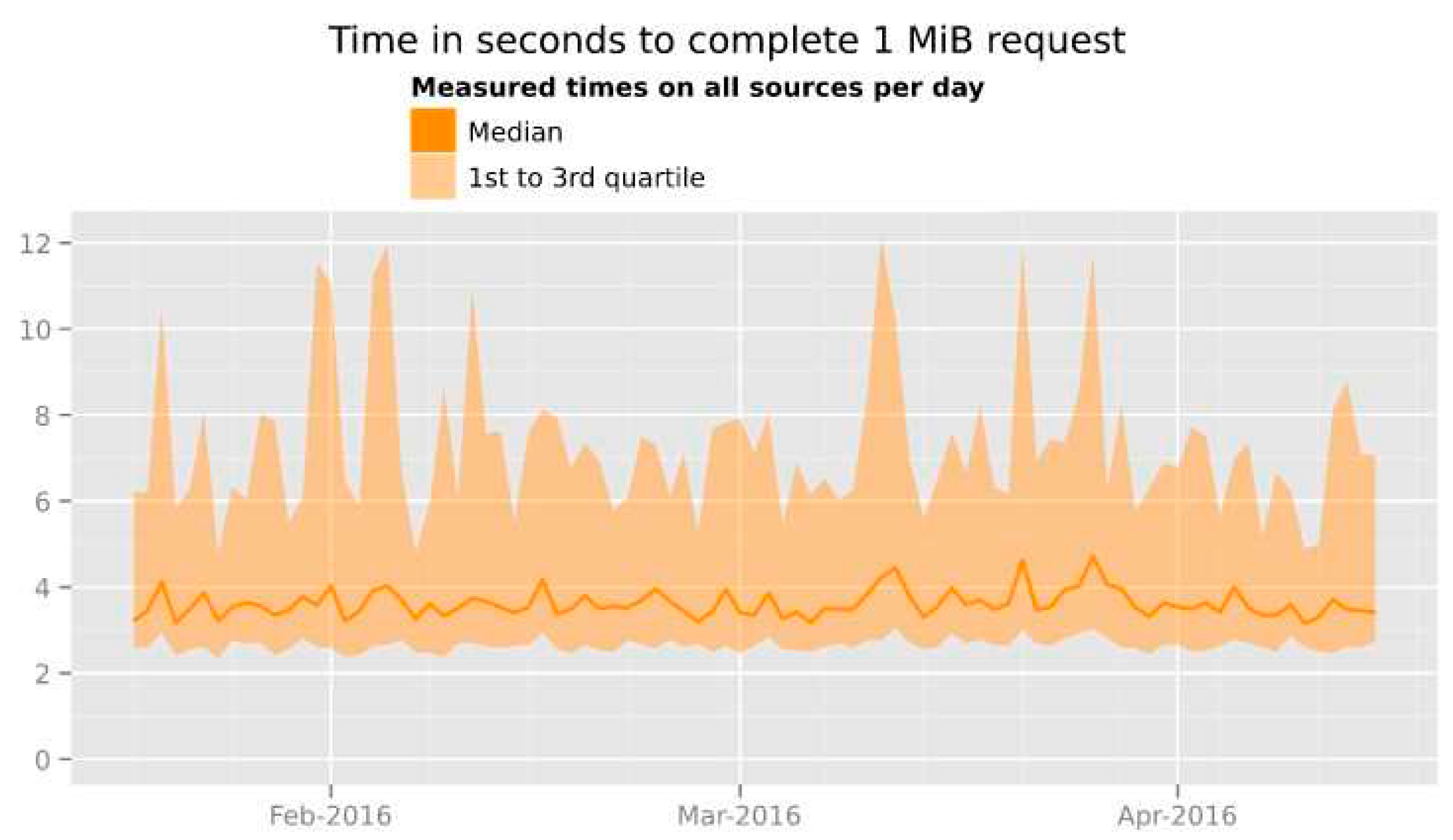

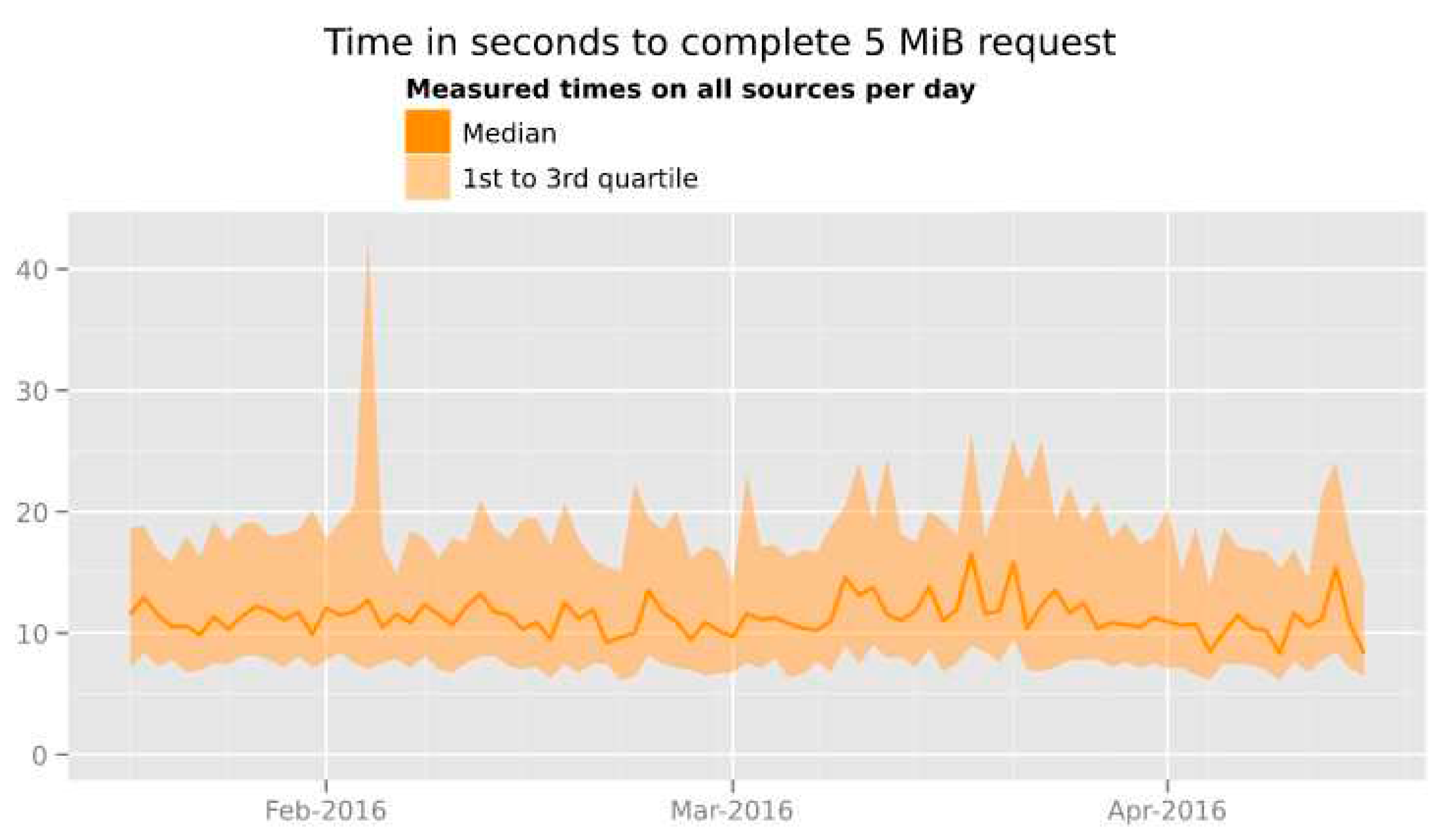

3.5. Performances and Congestion Management

- -

- Real time link and traffic exchange: the ORs share in an real time basis the information about the network status and traffic proportion with the directories server, this information are used to determine the circuit and manage the congestion over TOR.

- -

- Rate limit: ORs use token bucket configurable function that help to limit the bandwidth which an OR can use on the network.

- -

- Circuit windows: TOR circuit relies on a flow control function which limit the quantity of data traveling through a circuit for a given duration. Both the OP and the Exit OR are responsible of maintaining that window which is usually initialised to the default value of 1000 Cells (500 KB). This is the maximum number of cells that OP and exit OR can send before an acknowledgment is received.

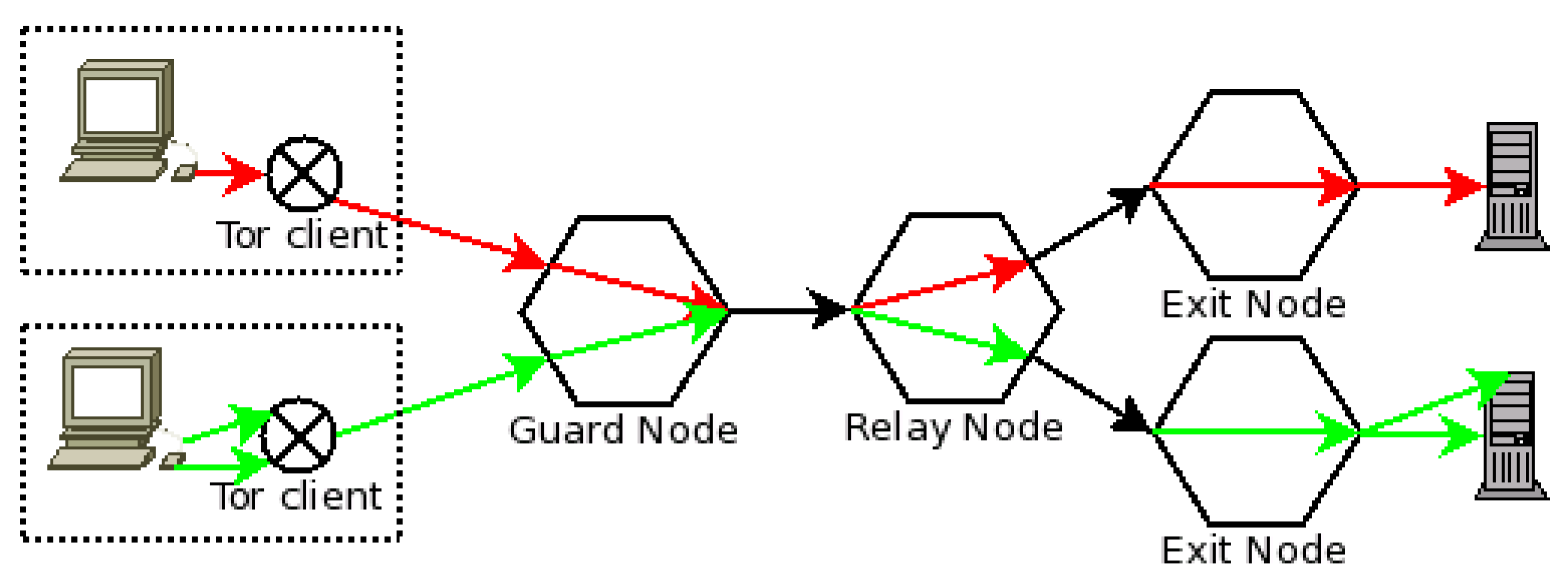

3.6. TOR Routing:

3.7. Circuit selection and scheduling:

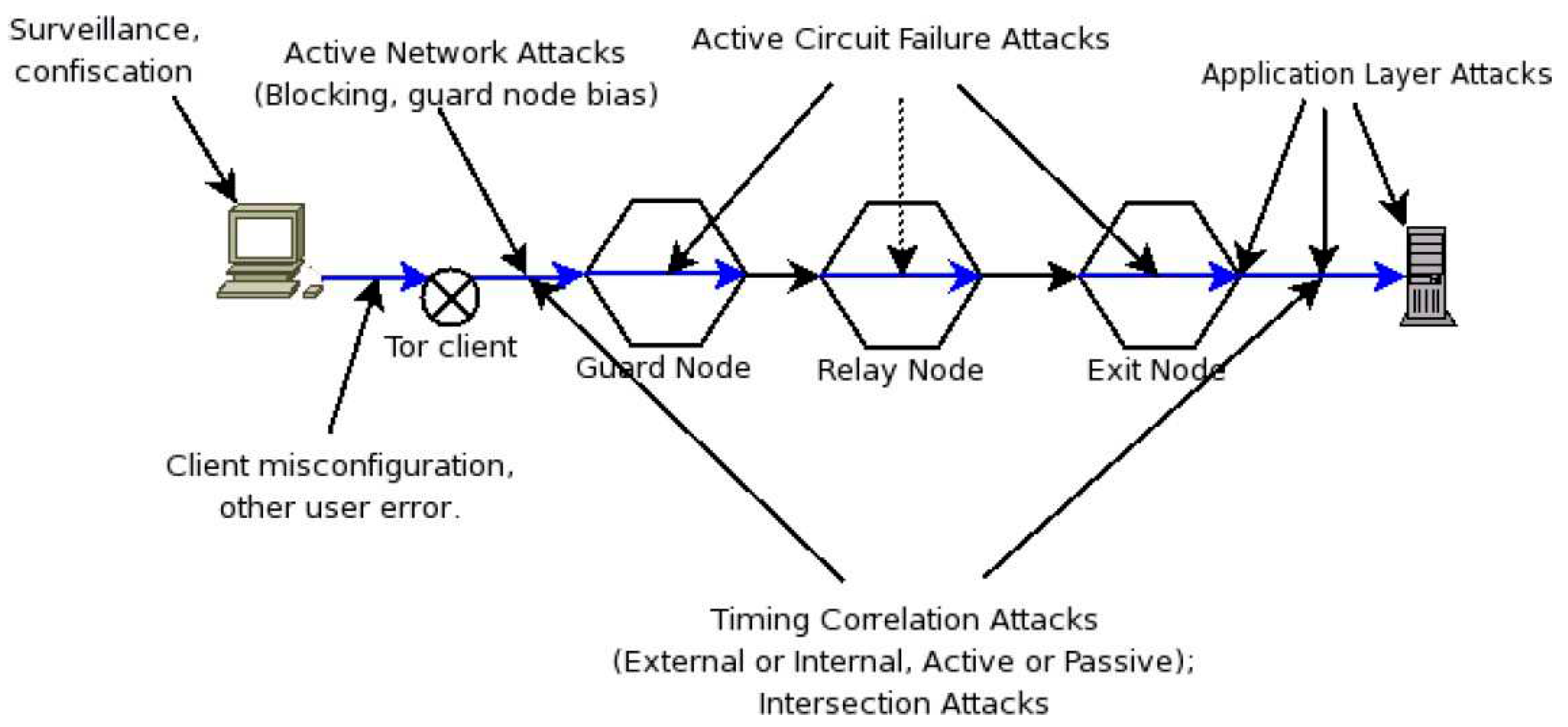

3.8. TOR limits and vulnerabilities:

3.8.1. Application Layer Attacks

3.8.2. Intersection Attacks

3.8.3. Traffic fingerprinting

3.8.4. Circuit Failure and Selection Attacks

3.8.5. Timing Attacks

3.8.6. Path Selection Attacks

Chapter 4: Proposed Improvements and Enhancements

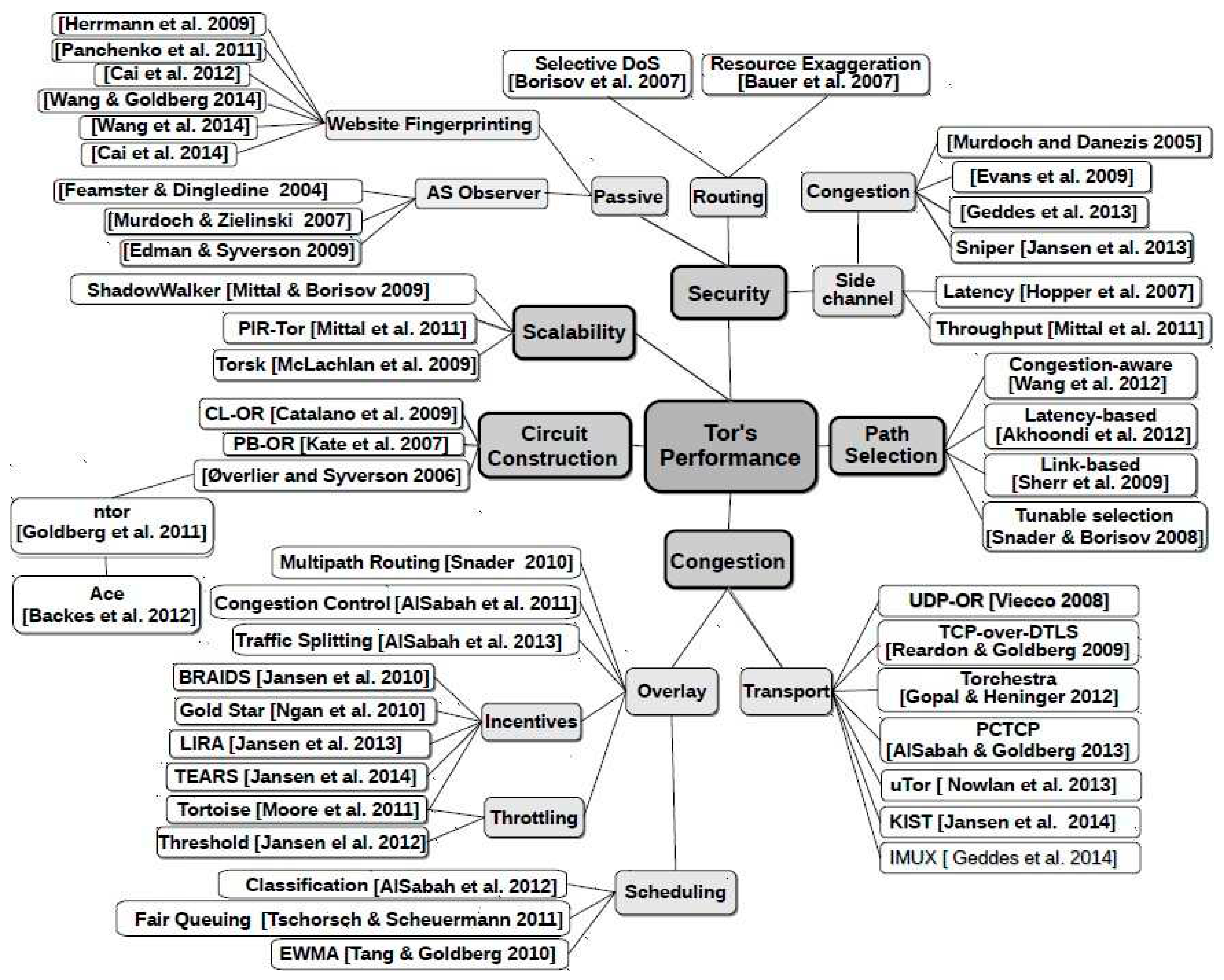

4.1. Related improving research:

4.2. Problem tackled during this works

- a)

- Cryptographic and performance enhancement

- b)

- Circuit selection security

- c)

- Sessions’ and Users’ Un-linkability

- d)

- Network Confusion and Diffusion

- e)

- Node-to-Node cells’ authentication

4.3. Proposed improvements and enhancements

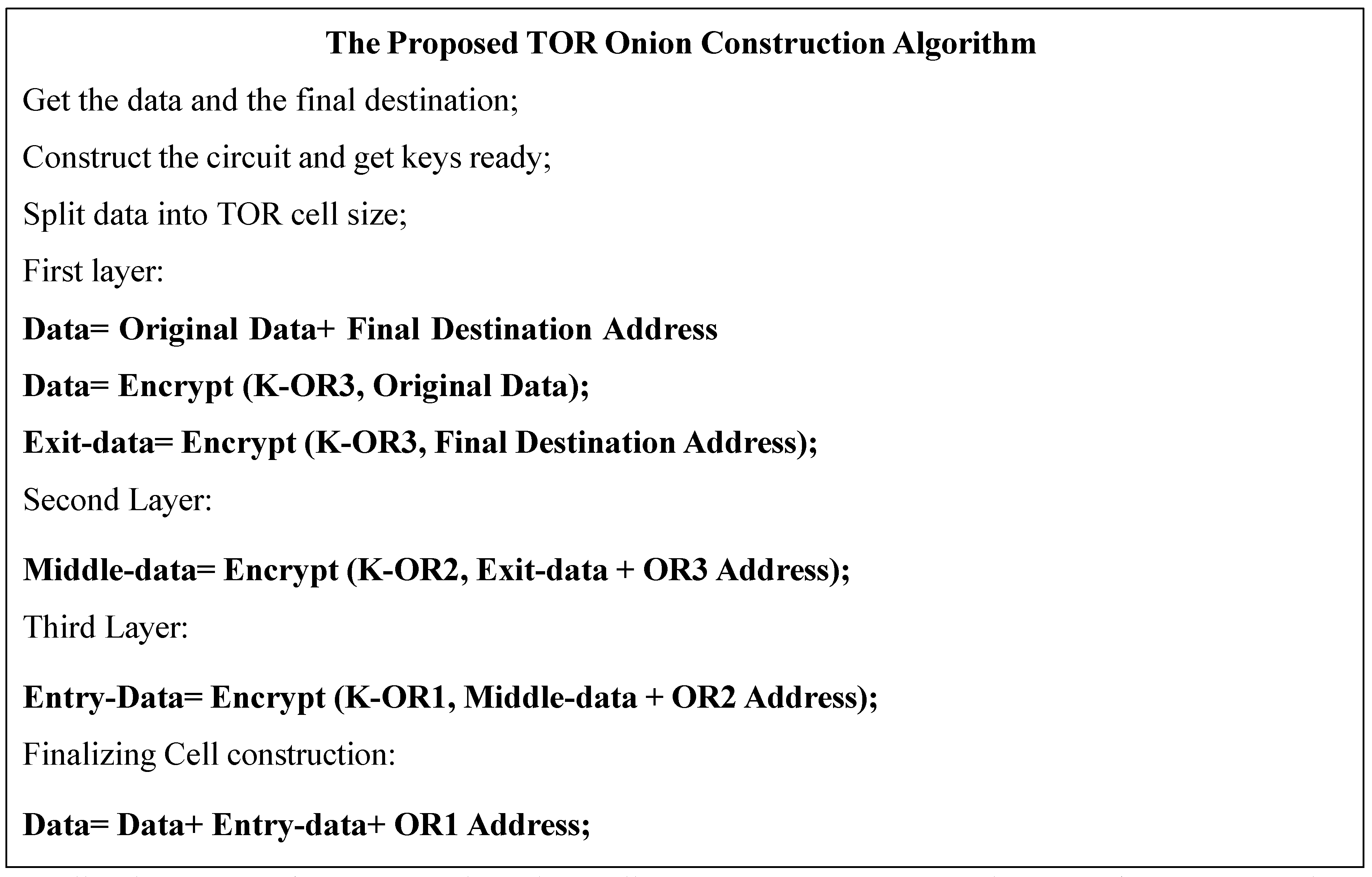

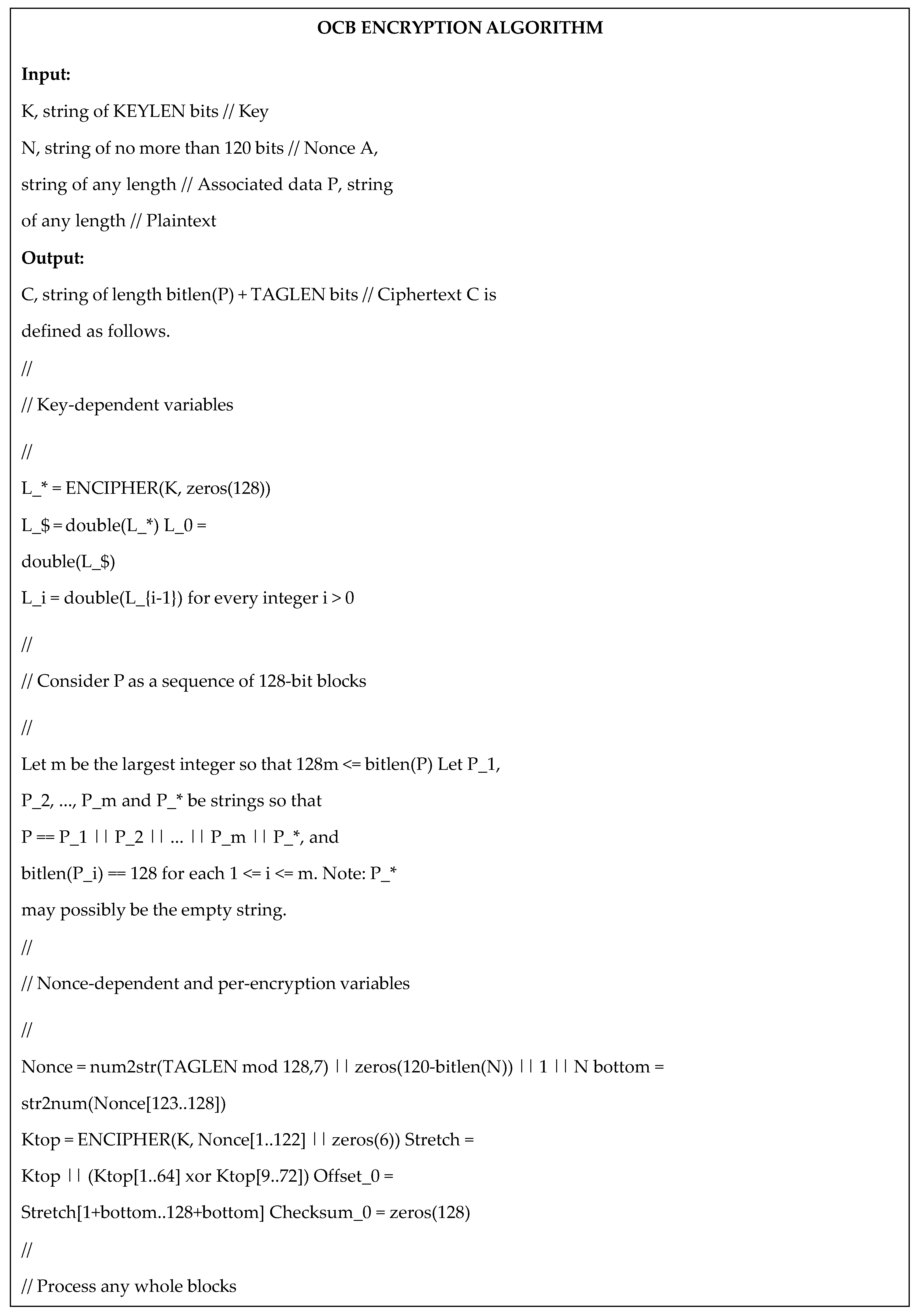

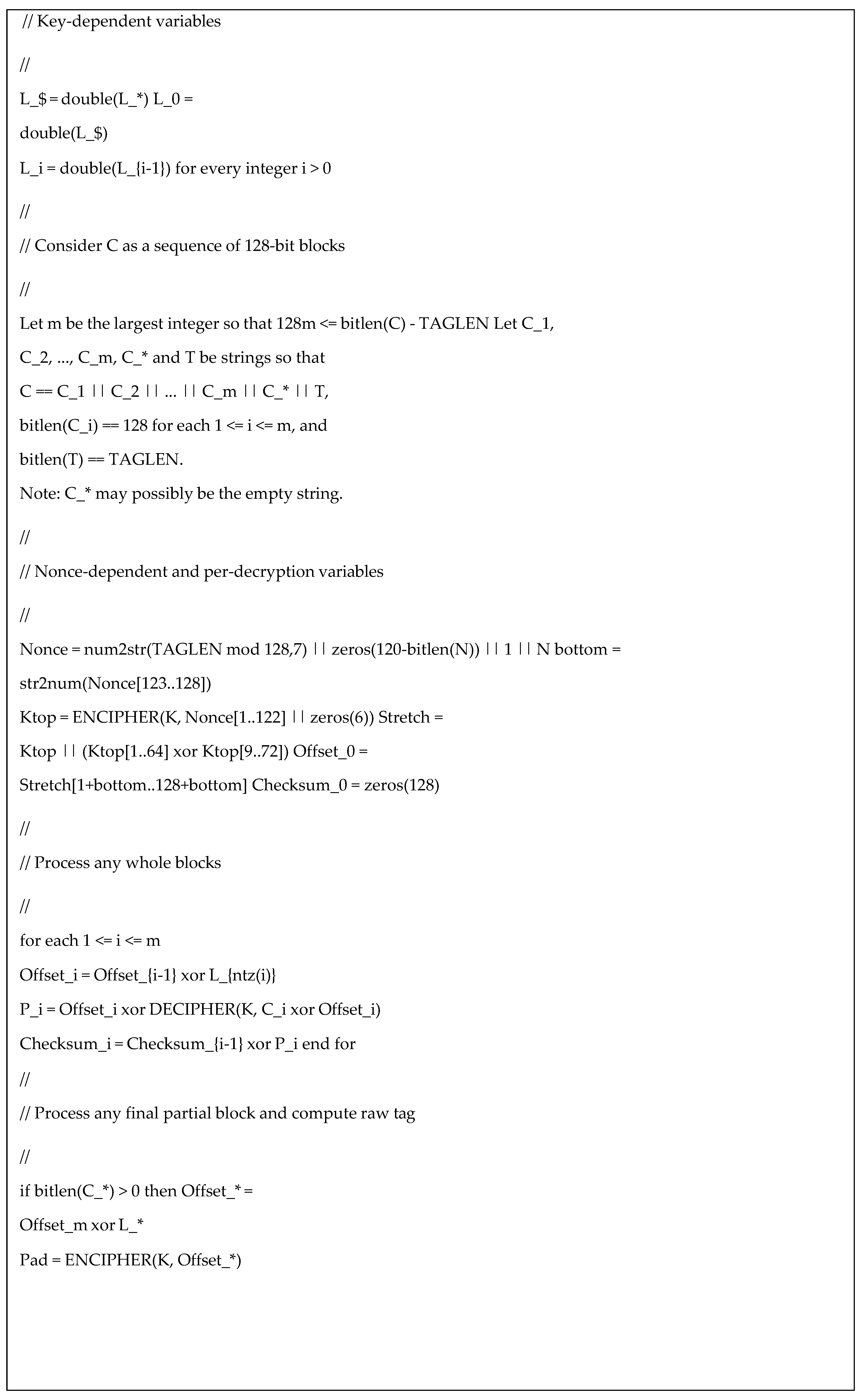

4.3.1. Multi-layer encryption improvement

- -

- OCB eliminate the problem of authenticated-encryption with associated-data (AEAD),

- -

- The OCB nonce required to encrypt and decrypt should not be necessary random as it utelise a counter,

- -

- OCB can encrypt data of any size without padding it to any convenient-length and therefore save some precious computing power.

- a)

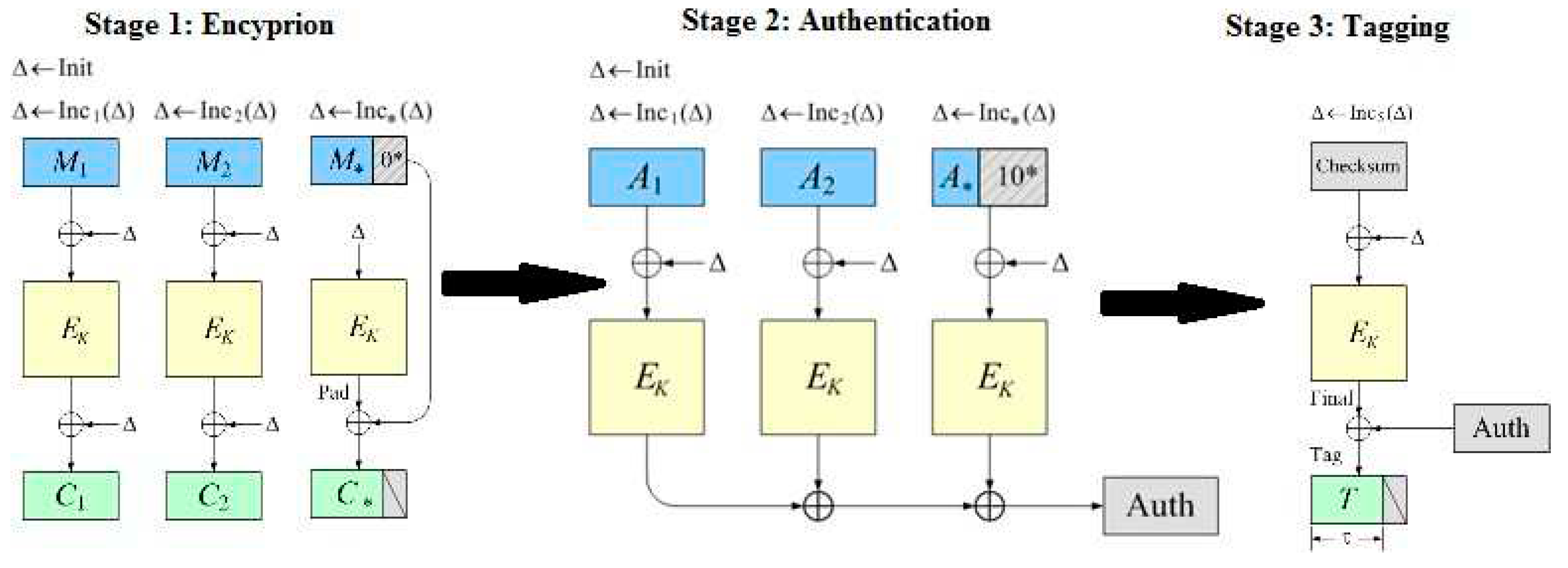

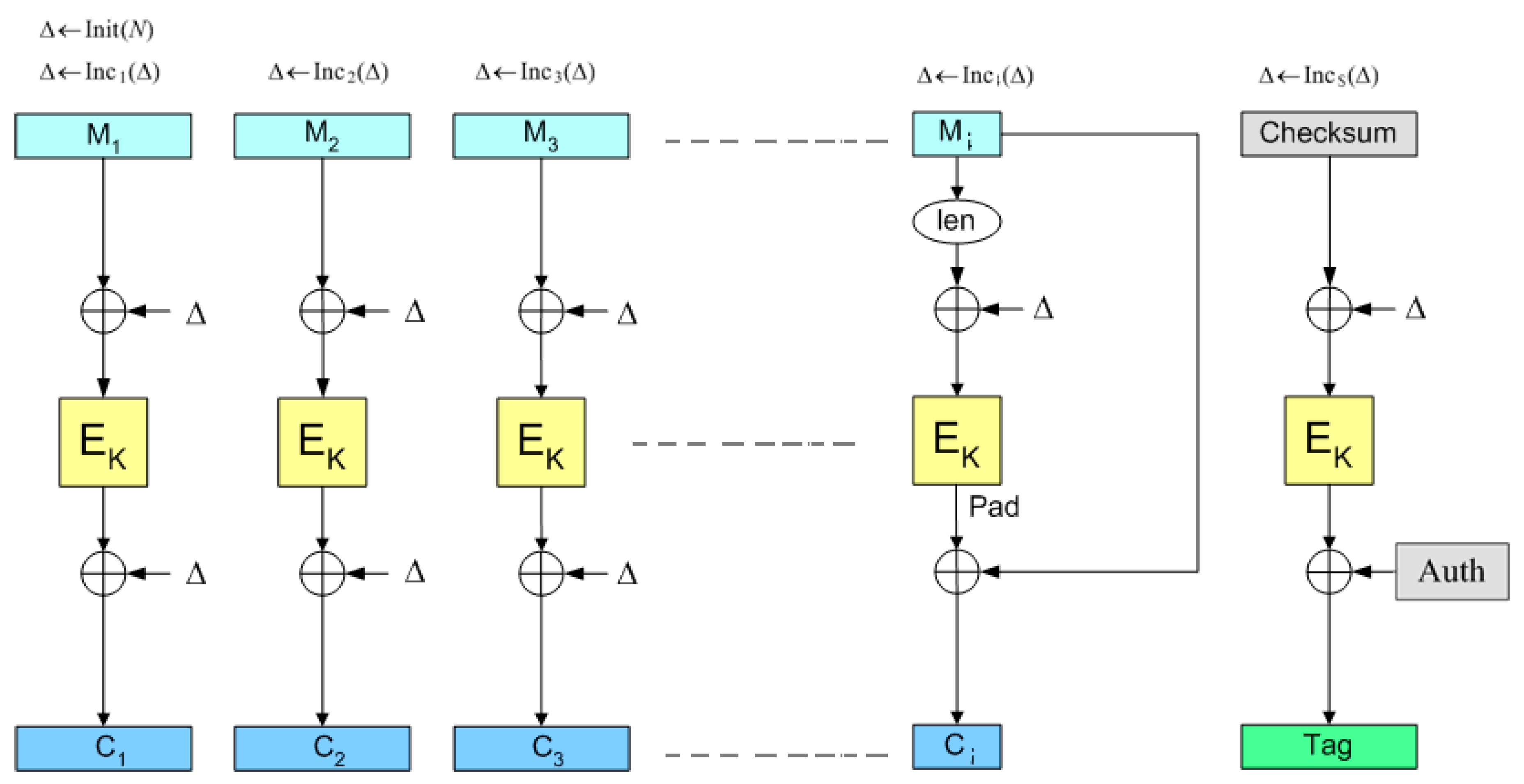

- Working principle of the OCB mode

- -

- First the plaintext M is divided into blocks of 128 bits each M = M1 ... Mm, Here there is two cases; the data size in bit is a multiple of 128, or there is a remainder and therefore the algorithm require a padding.

- -

- Secondly, a Checksum of 128 bits is calculated Checksum = M1 ⊕…⊕ Mm and will be used later during the authentication process.

- -

- Thirdly, an initialisation function “Init” take place and using the nonce N which is concatenated with a 32 bits constant value to produce a 128 bits value called “Top”. Later, the

- -

- Fourthly, for each block “i” the increment is called to increment the Δ, XOR with the Mi, and encrypted using the key K and the algorithm AES-OCB as showed in the scheme. Later, the output of the encryption in stage 4 is XOR again with the Δ to produce Ci... The authenticated ciphertext is CT = C1 C2 … Cm T.

- -

- Fully parallelizable operations of the block ciphering can be performed simultaneously. Thus, OCB is very efficient and suitable for hardware encrypting at high network speeds.

- -

- Block-ciphering scheme make it strong and resist better to the new timing attacks which the other mode like CBC would be vulnerable.

- -

- OCB is a single key scheme as it use the same key for encryption and authentication which make it more efficient in term of memory use.

- -

- OCB can process any data size without requiring it to be a multiple of the block length. Moreover, no external padding function is used and thus it economise time as there is no bits- waste in the ciphertext due to padding.

- -

- The main computational function used beyond the block-ciphering is XOR which is very time and power efficient function (three 128 bits XOR per block).

- -

- OCB can be perfectly used into memory-limited systems as the main memory cost the amount needed to hold the AES sub-keys.

- b)

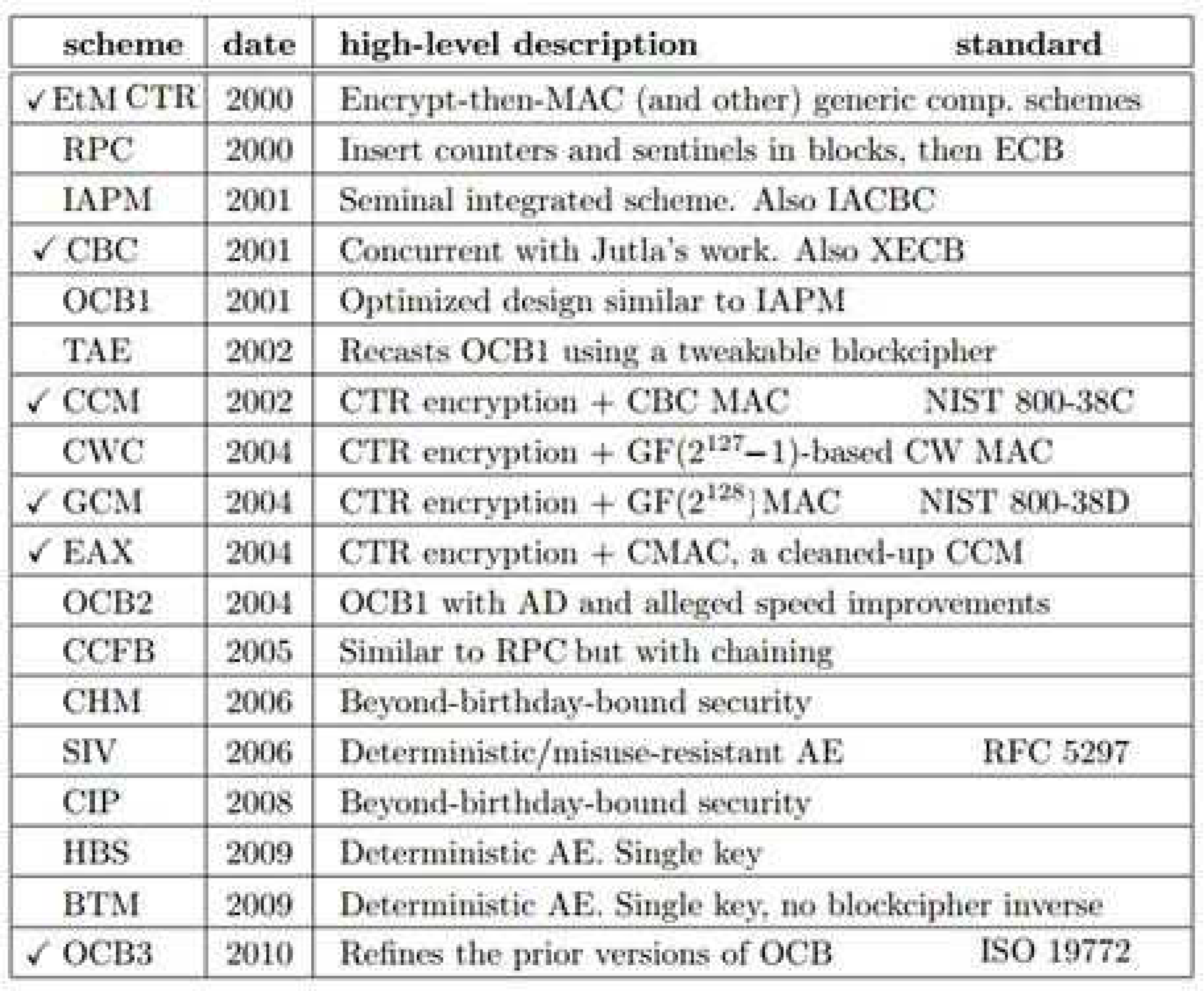

- Choice justification

- c)

- Cryptographic features comparison against competitors

| Feature | CCM | GCM | OCB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security Proved | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Online ability | No | Yes | Yes |

| Key requirement | 128 bits block size | 128 or 64 bits block size | 128 or 64 bits block size |

- -

- Provably secure: all the three modes are proved to be mathematically secure by assuming that the used with block cipher (AES) is pseudorandom permutation. As far as the cryptography permit, AES is proved secure and thus both three modes of implementation are absolutely secure.

- -

- Online message processing: this feature is crucial for the suitability of the mode as the modes should be able to process data without knowing the whole length in advance as the TOR have no pre-set or pre-defined data length. Moreover, this feature is highly desired for a memory restricted environment which is the case of ORs in this part, CCM mode fail to achieve the set baselines.

- -

- Cipher requirements: CCM mode is developed to only work with ciphers using block size of 128 bits, while GCM and OCB can work with cipher using different block size (64/128 bits).

4.3.2. The Encapsulation approach (Onion wrapping method)

- d)

- Proposed Improvement:

4.4.3. The number of intermediate ORs

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

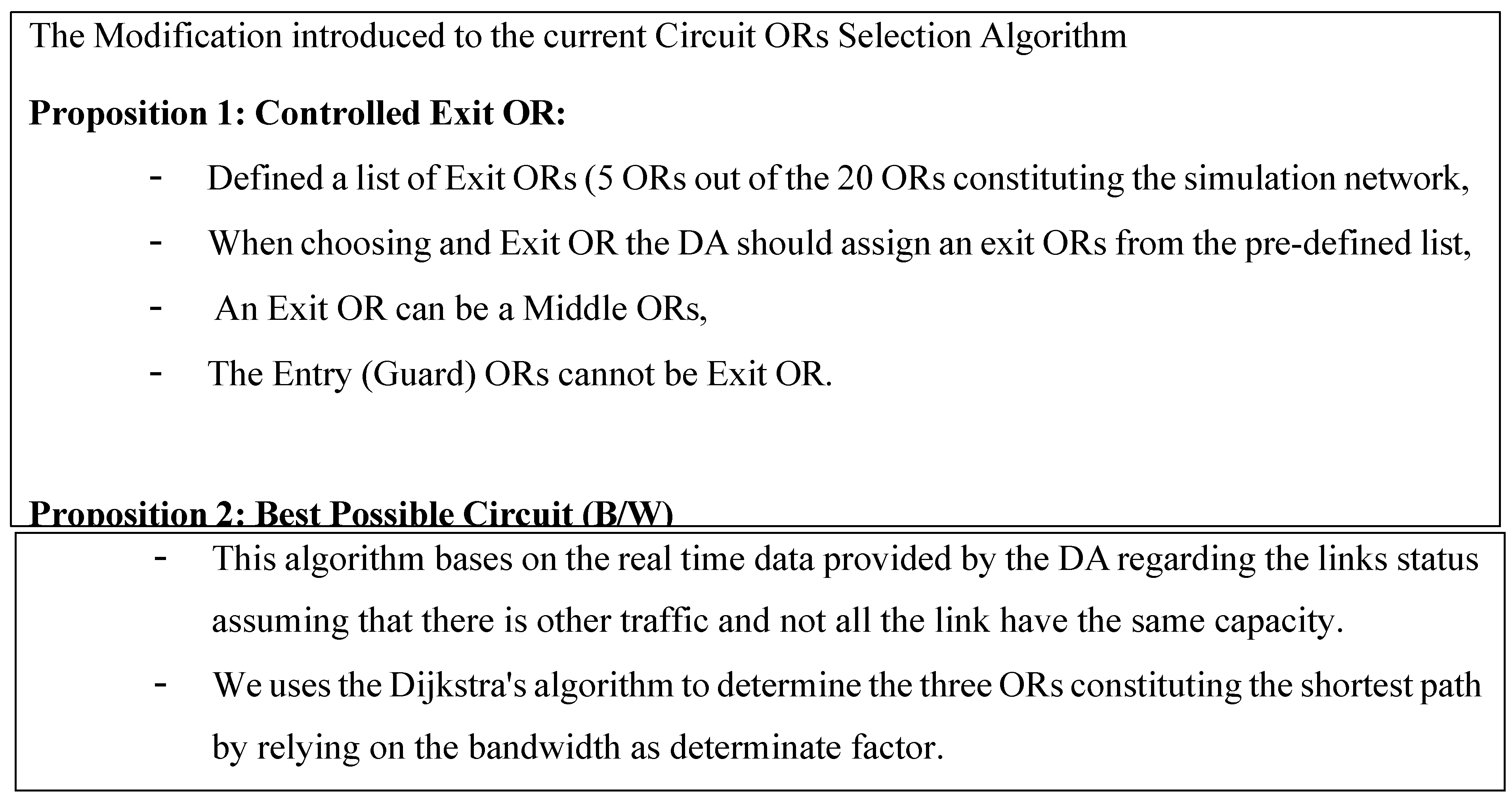

4.4.4. Circuit ORs’ Selection Approach

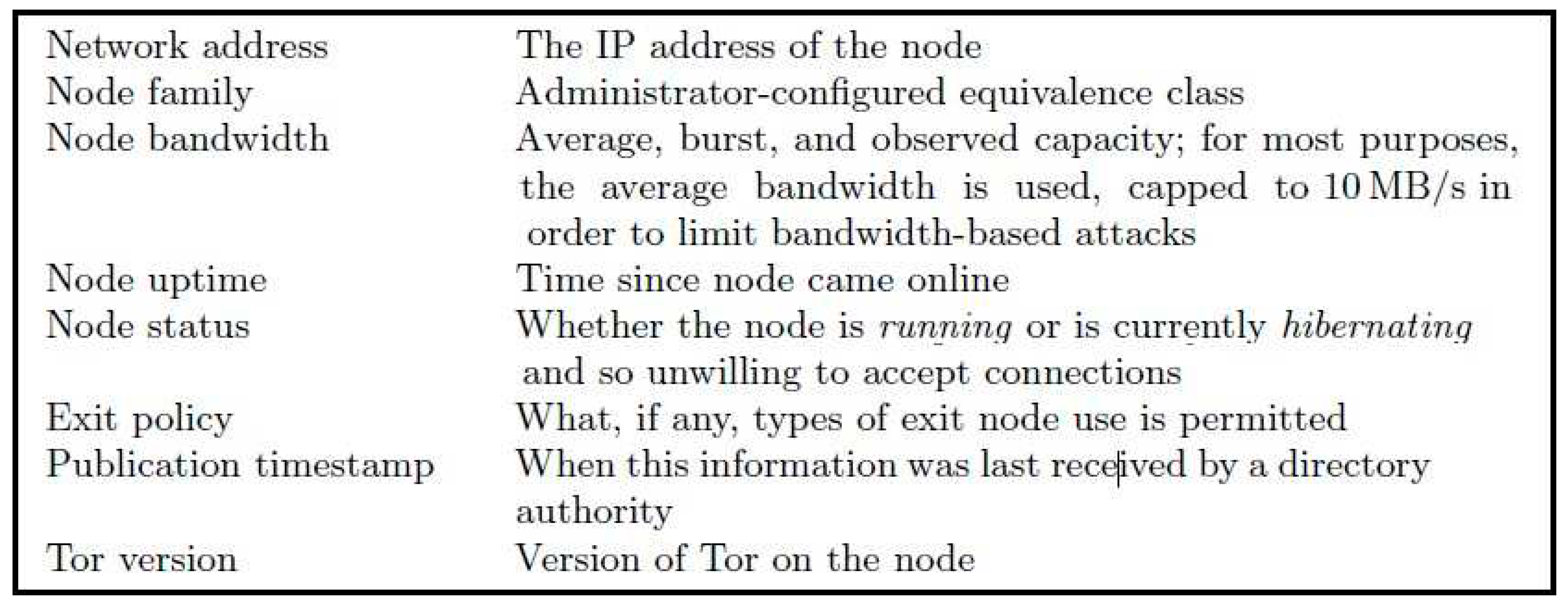

- -

- No OR should be used in the same circuit more than once,

- -

- ORs in the same circuit should belong to different class of TOR network,

- -

- A special treatment for co-administered ORs is introduced by marking them as the same family,

- -

- Directory Authorities will assign flags to ORs basing on the following parameters: performances, status, position and role.

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

- b)

- Dynamic circuit construction with traffic management

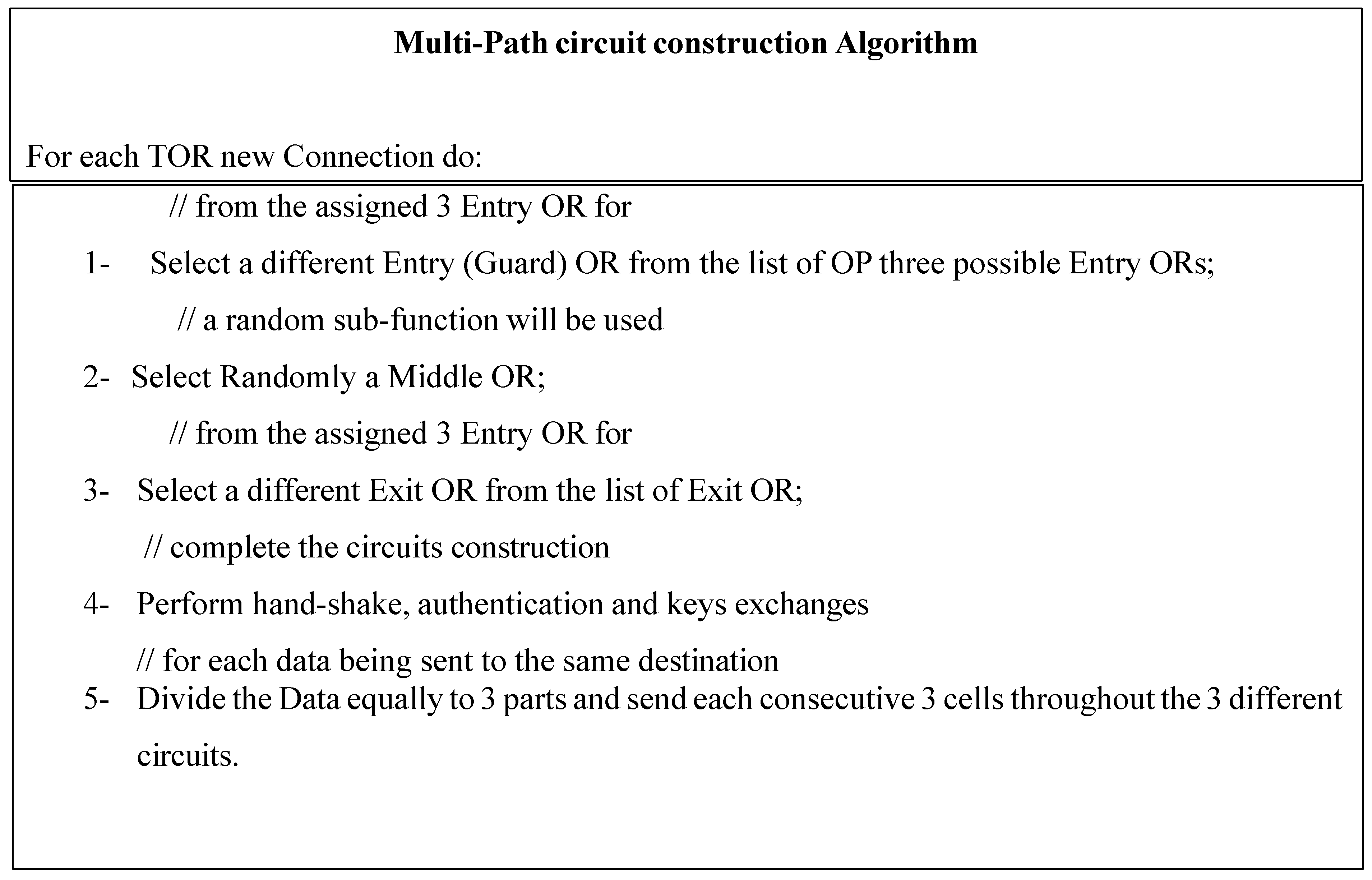

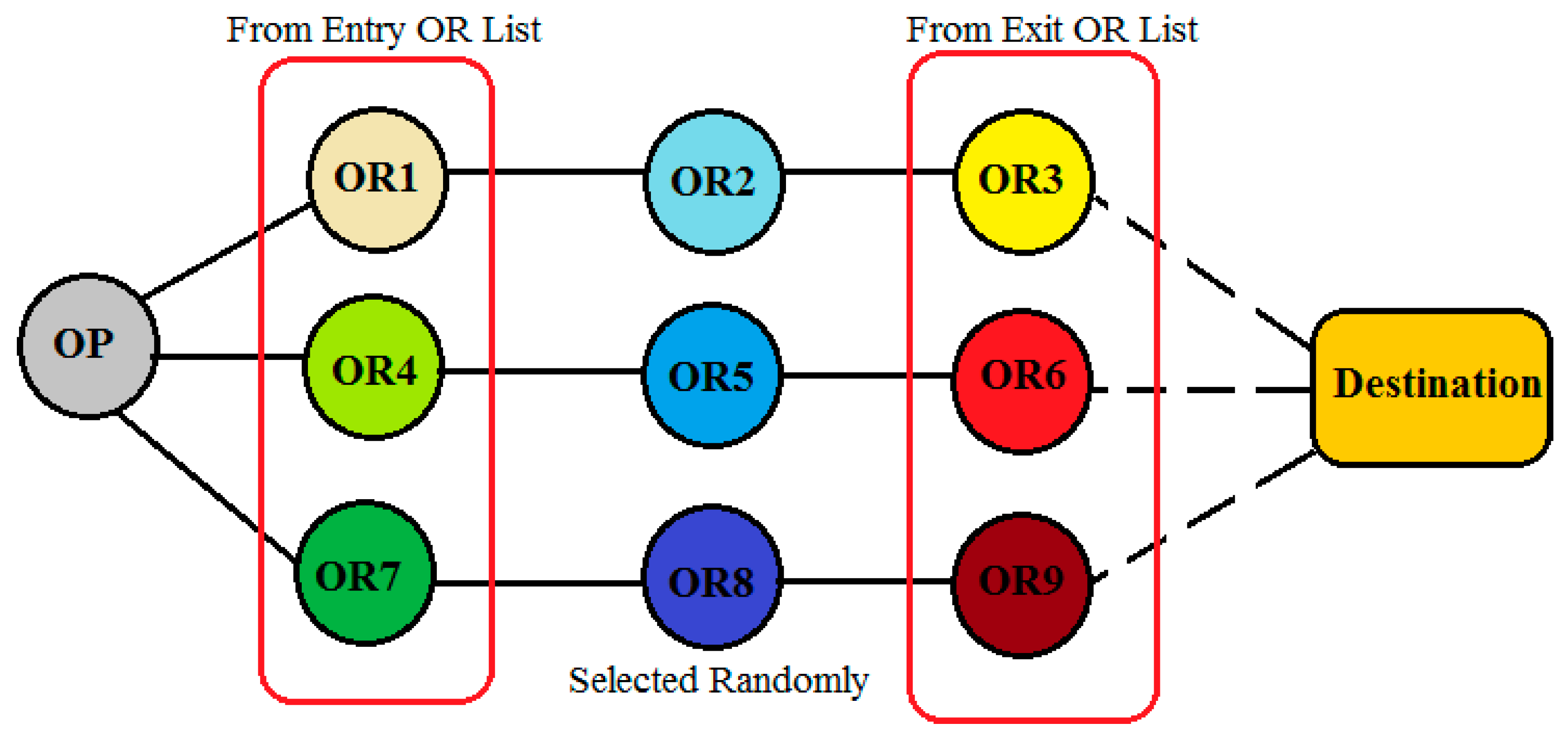

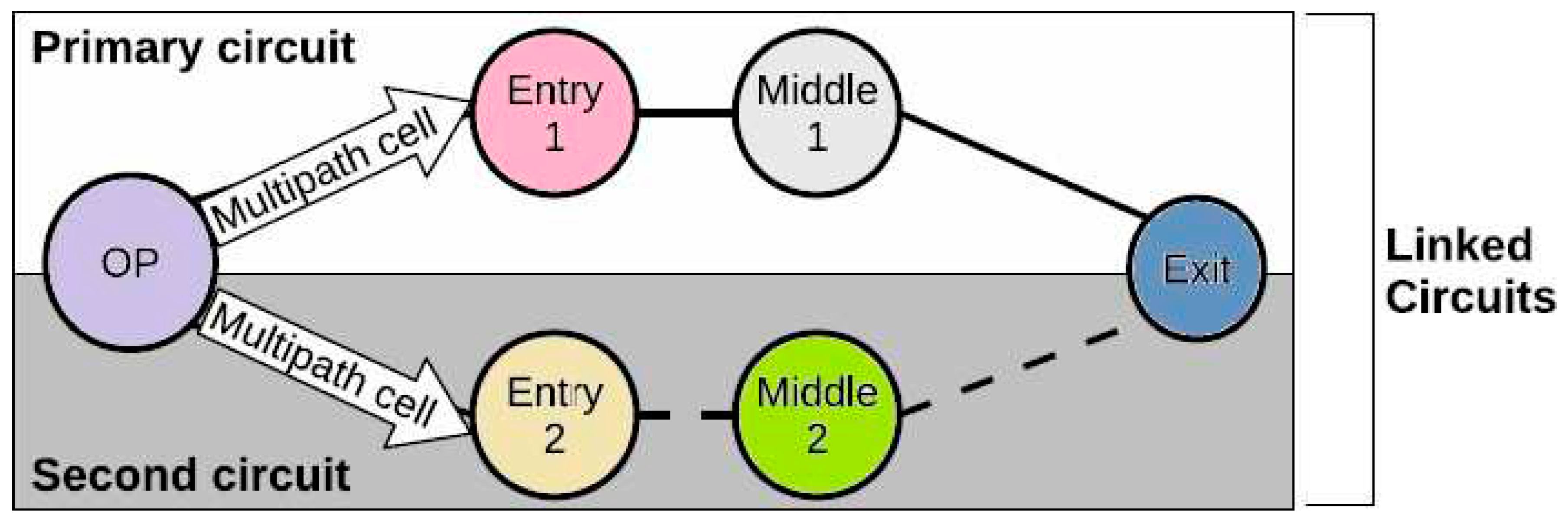

4.4.5. Cells’ Multi-circuit routing (limited to three Circuits)

- a)

- Proposed Improvement

Chapter 5: Implementation, Testing and Results

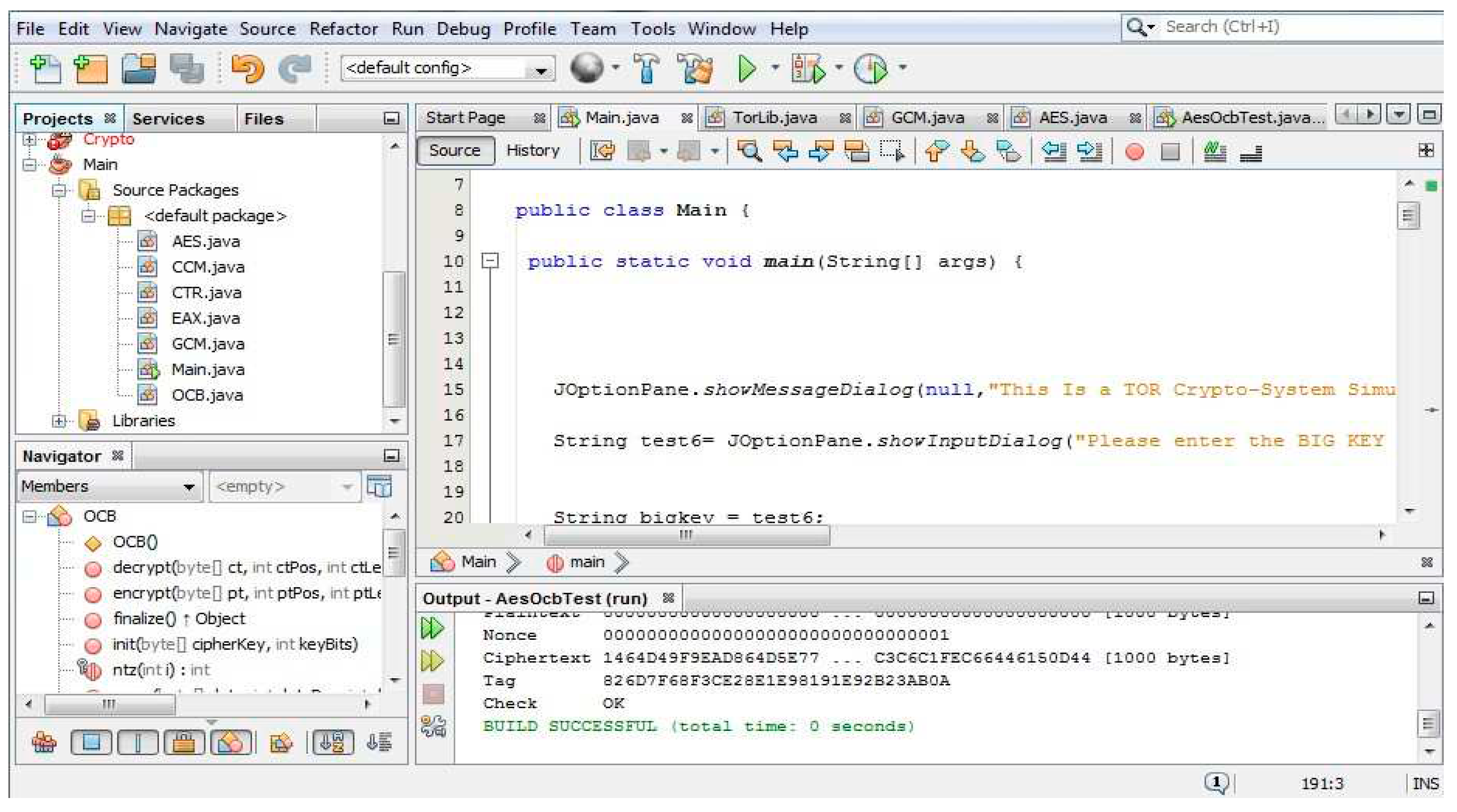

5.1. Simulation test-beds design and adoption

- -

- Implementing, testing and comparing the obtained results of AES-OCB, AES-GCM and AES-CCM,

- -

- Implementing the proposed Wrapping approach (multi-layered encapsulation), testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Implementing the two variant of Circuit construction algorithms, testing and comparing the results,

- -

- Implementing the variable circuit length algorithm, testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Implementing the Multi-path Cell routing algorithm, testing and comparing the obtained results,

- -

- Validation of the results and discussion.

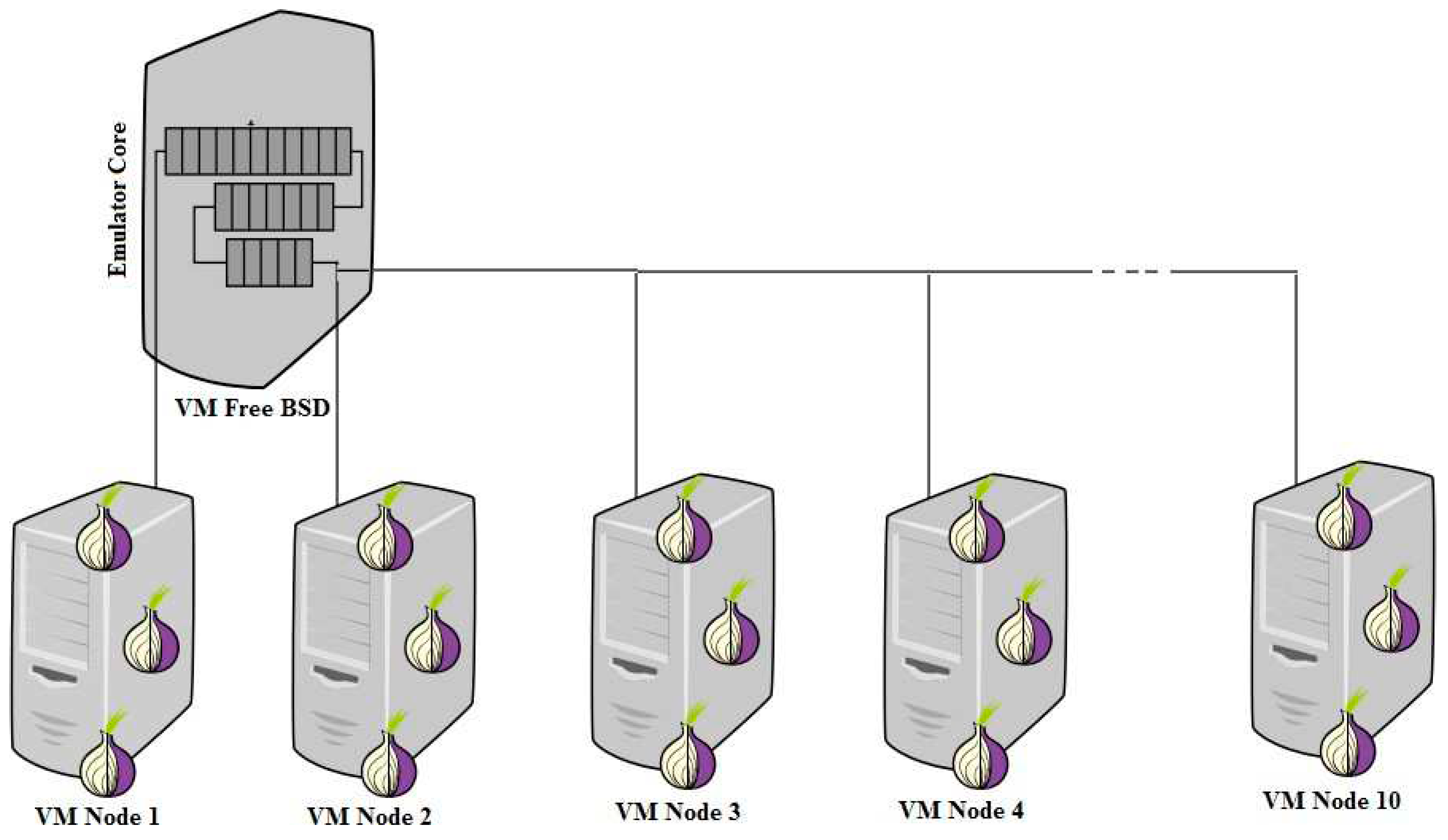

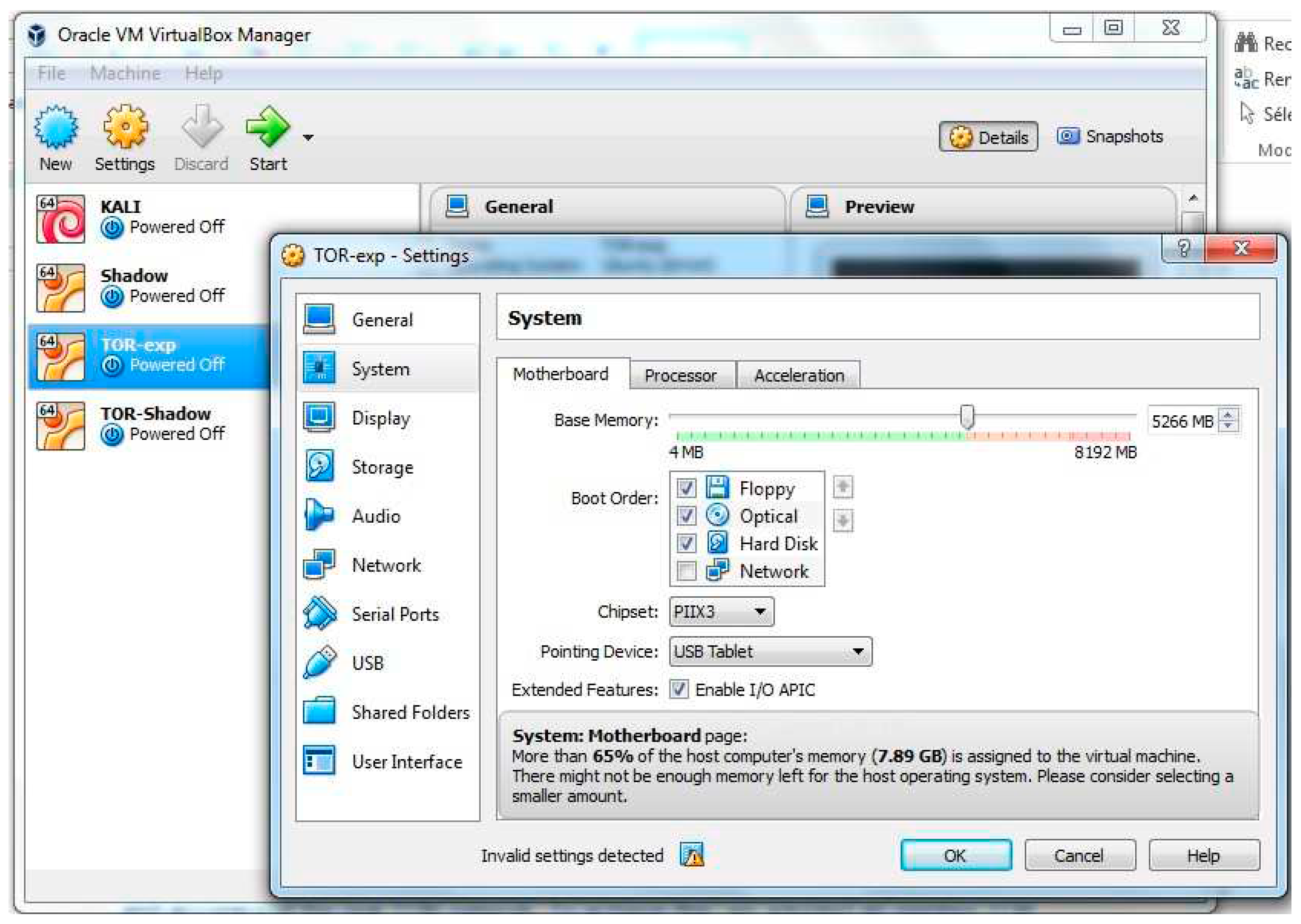

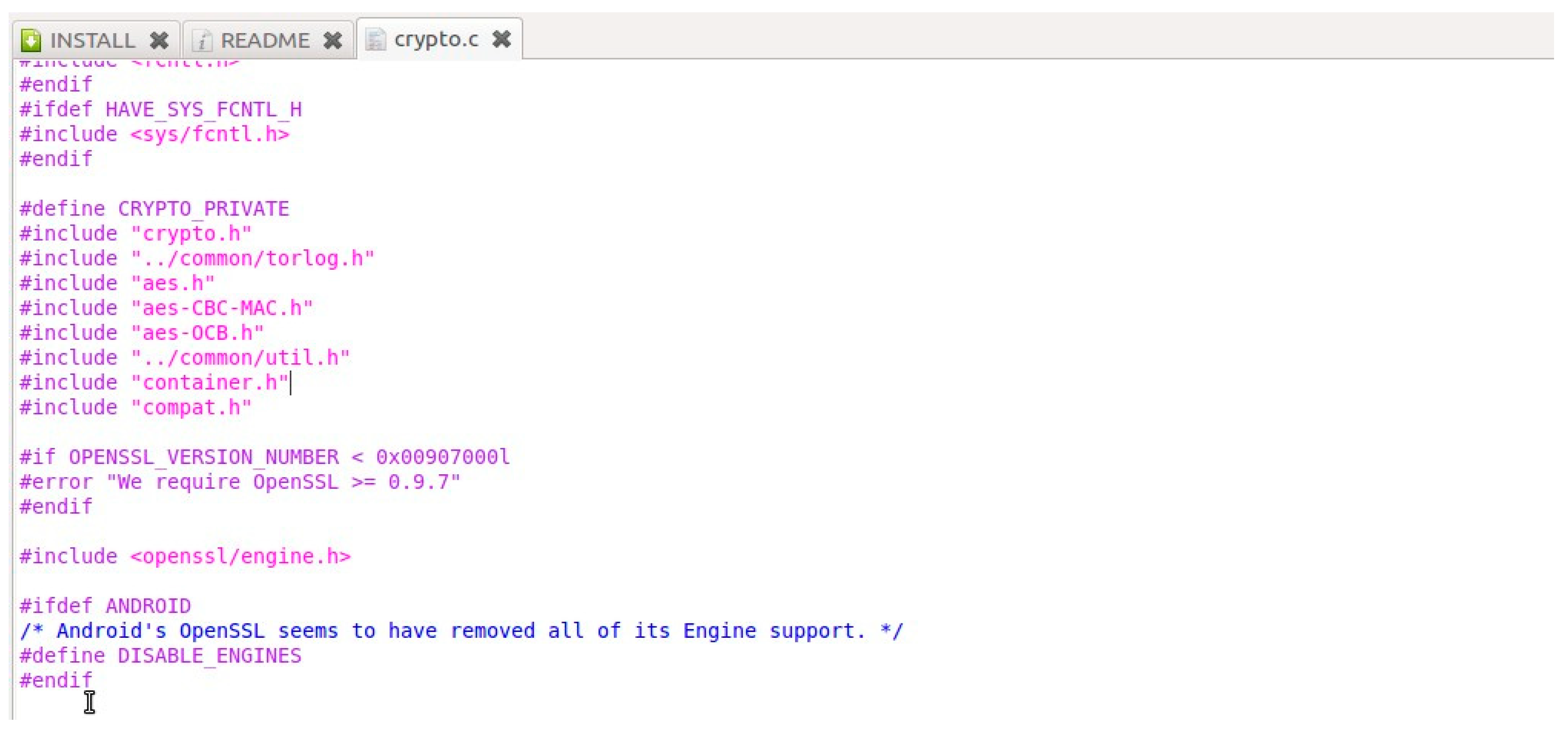

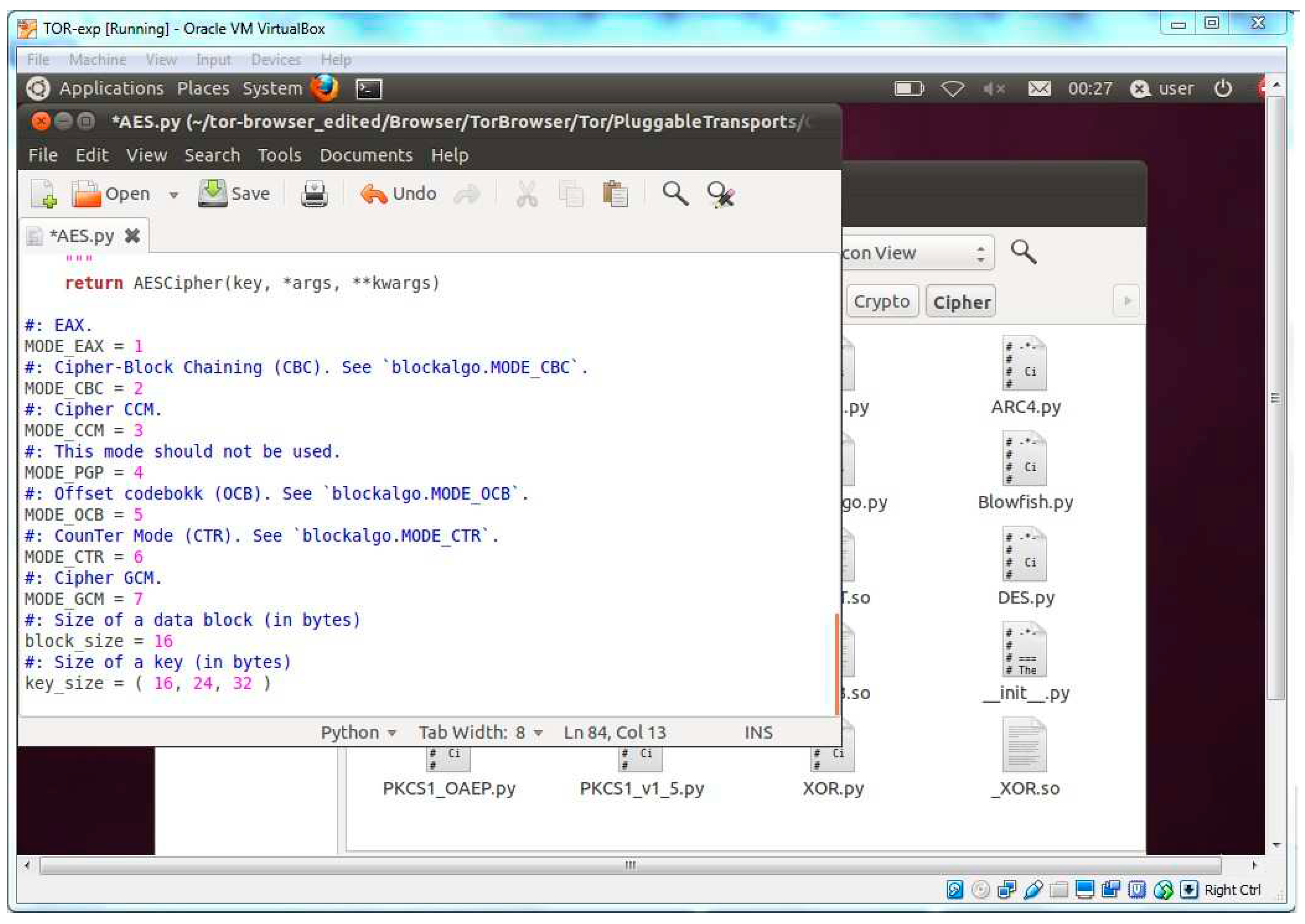

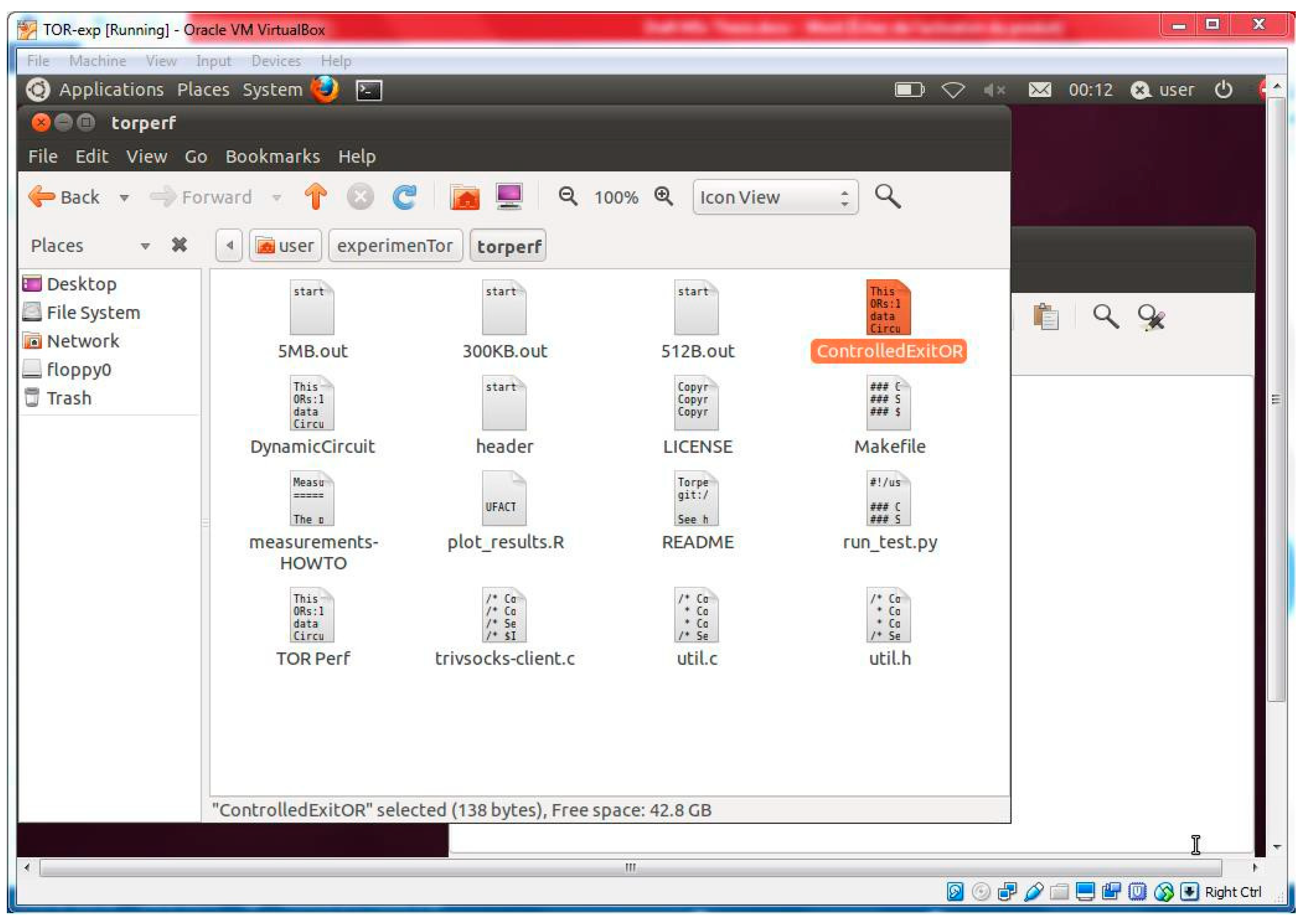

5.2. ExperimenTOR platform

5.3. TOR test-bed topology and deployment

5.3.1. Simulation network size

- -

- Twenty (20) FreeBSD Onion Routers including 3 dedicated Guard (Entry) ORs,

- -

- One Directory Server (DA),

- -

- Three (03) Onion Proxy (Clients),

- -

- One service server (destination),

- -

- Different size testing data

5.3.2. Test-bed Preparations and configuration:

5.3.3. Logging and measurements

5.4. Testing and results

5.4.1. Testing the proposed ciphers and encapsulation approach

- -

- AES-OCB-128,

- -

- AES-CCM-128,

- -

- AES-GCM-128,

- -

- AES-EAX-128,

- -

- Add a separate MAC calculation function to the existing CBC and CTR code.

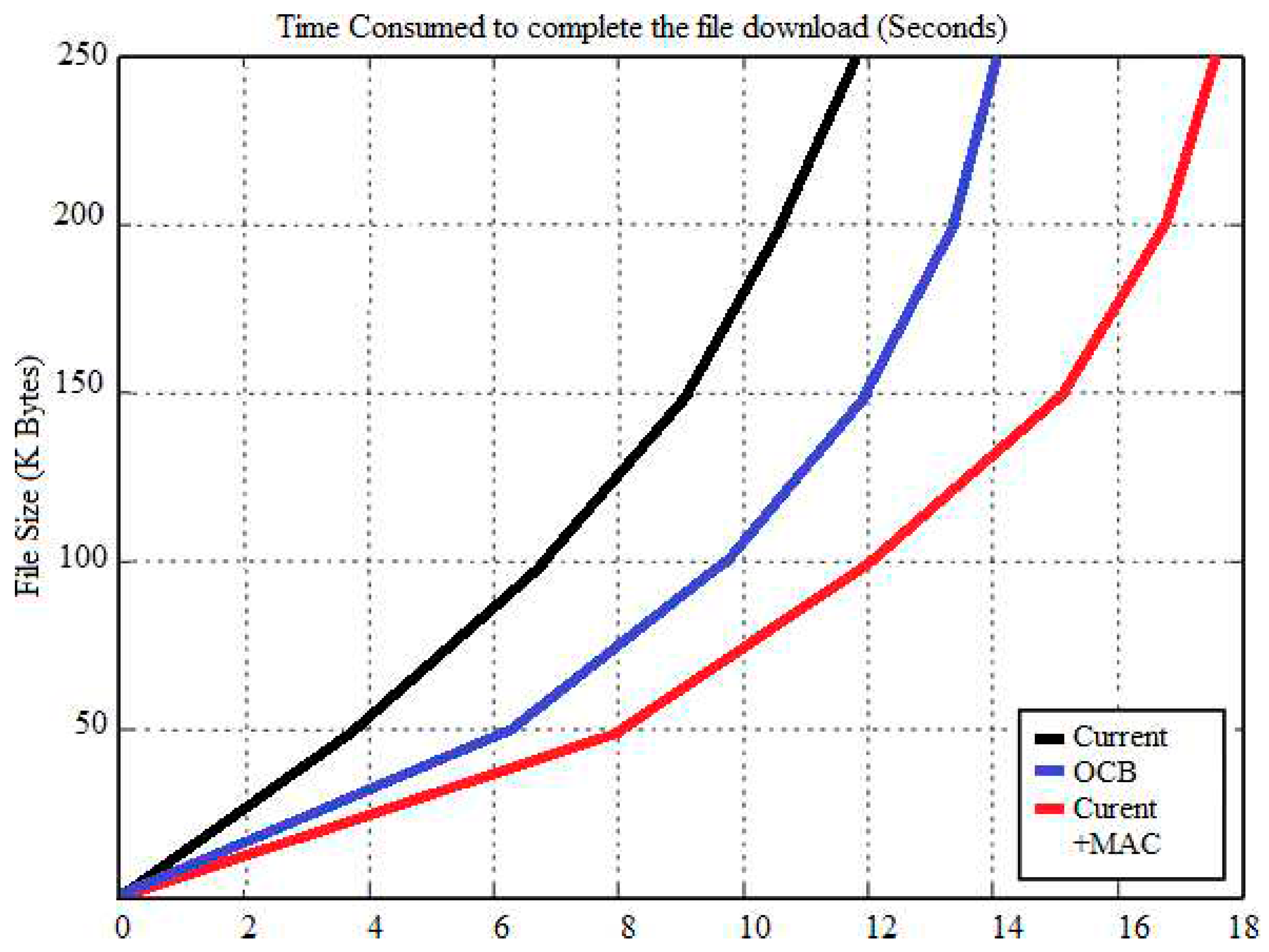

- a)

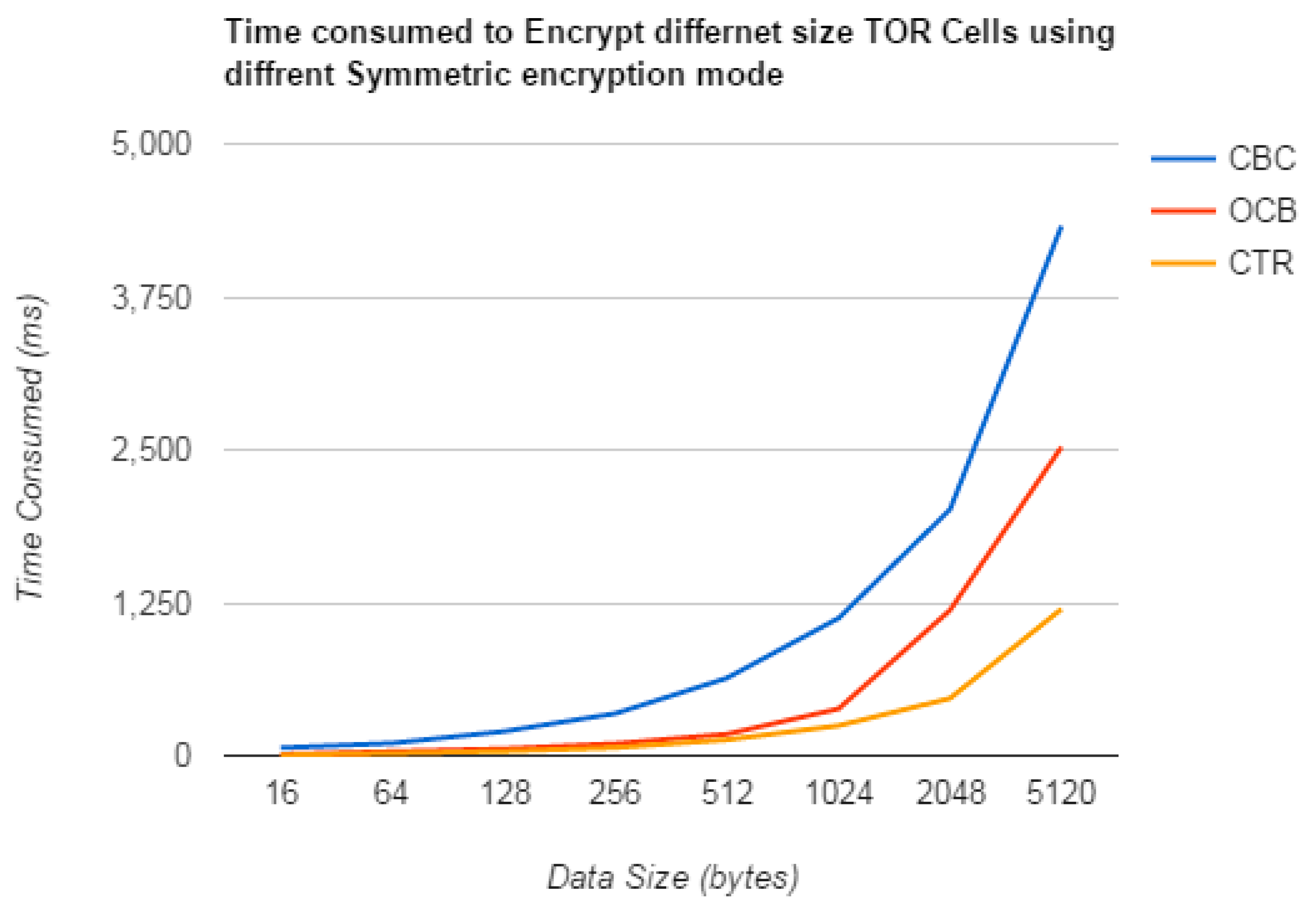

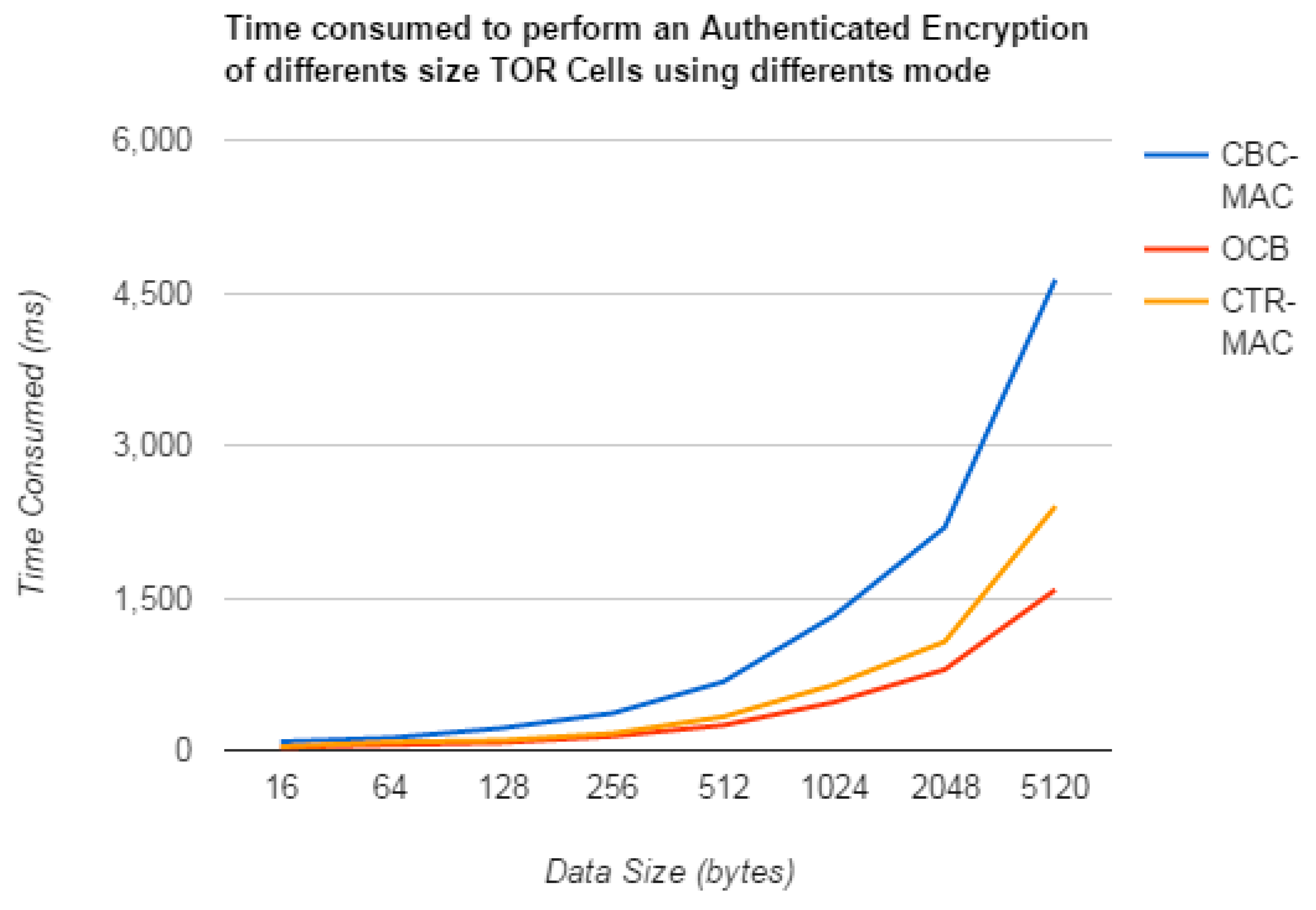

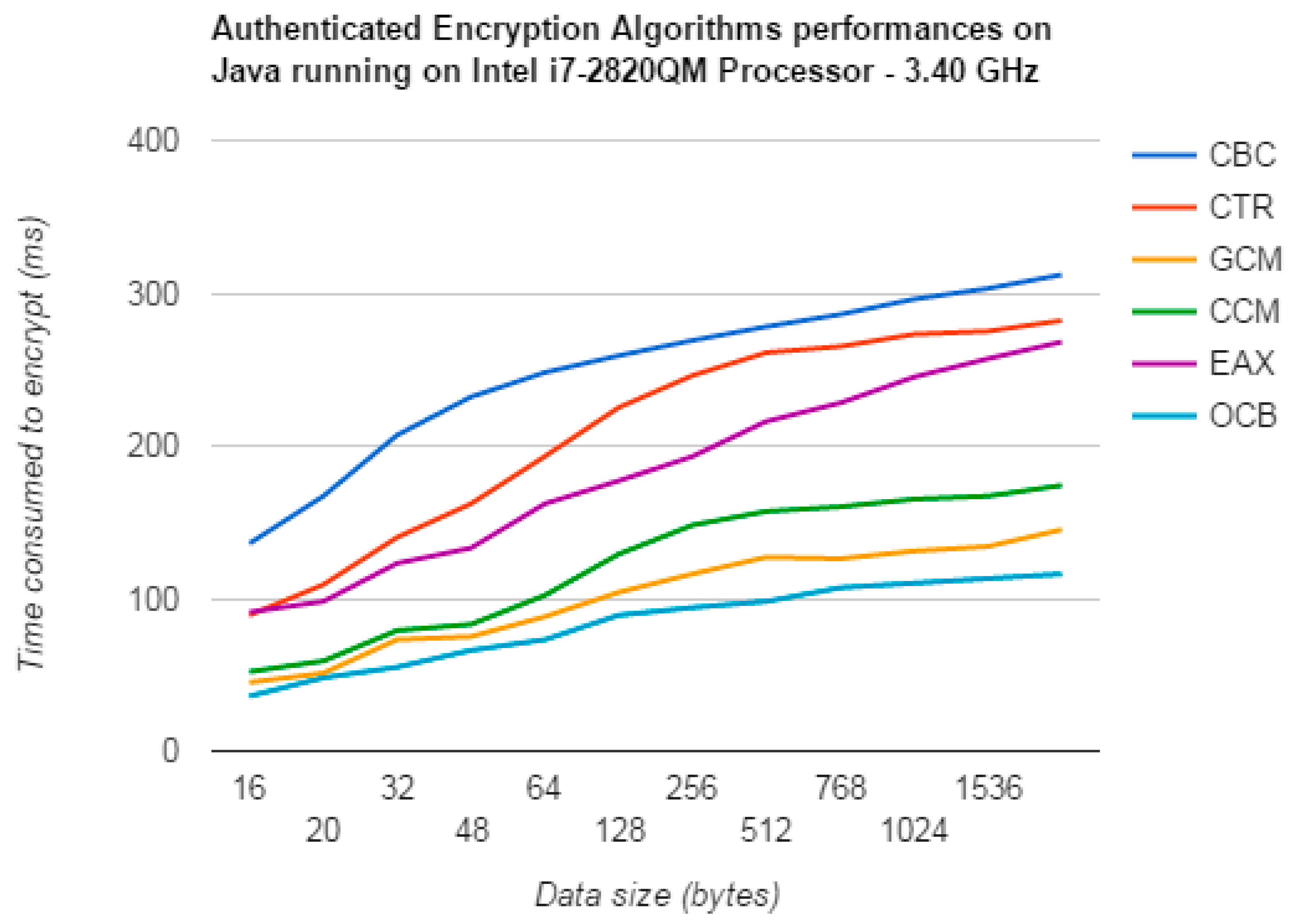

- Experimentation Results and Discussion

| Input size (Bytes) | 16 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 5120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Consumed (ms) per mode | ||||||||

| CBC | 64.11 | 102.31 | 198.34 | 344.76 | 634.21 | 1123.44 | 2011.54 | 4329.33 |

| OCB | 10.54 | 34.25 | 56.23 | 98.50 | 176.32 | 322.90 | 603.74 | 1488.60 |

| CTR | 5.82 | 20.58 | 36.77 | 65.88 | 129.98 | 245.34 | 468.13 | 1198.86 |

| Data Size | 16 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 5120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Consumed (ms) per mode | ||||||||

| CBC+MAC | 84.11 | 122.31 | 218.34 | 364.76 | 674.21 | 1323.44 | 2191.54 | 4629.33 |

| CTR+MAC | 35.82 | 80.58 | 96.77 | 165.88 | 329.98 | 645.34 | 1068.13 | 2398.86 |

| OCB | 29.54 | 54.25 | 76.23 | 138.50 | 246.32 | 472.90 | 793.74 | 1578.60 |

| Data size (Bytes) | 16 | 20 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 768 | 1024 | 1536 | 2048 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time consumed (ms) per Mode | |||||||||||

| CBC | 136 | 167 | 207 | 232 | 248 | 259 | 269 | 278 | 286 | 299 | 312 |

| CTR | 89 | 109 | 140 | 162 | 193 | 225 | 246 | 261 | 269 | 275 | 282 |

| EAX | 91 | 98 | 123 | 133 | 162 | 177 | 193 | 216 | 228 | 257 | 268 |

| CCM | 52 | 59 | 79 | 83 | 102 | 129 | 148 | 157 | 160 | 167 | 174 |

| GCM | 45 | 51 | 73 | 75 | 88 | 104 | 116 | 127 | 131 | 139 | 153 |

| OCB | 36 | 48 | 65 | 73 | 89 | 101 | 113 | 120 | 127 | 135 | 148 |

- b)

- Encryption testing results

- c)

- Resources use analysis

- d)

- Choice and Discussion

- -

- CCM is inspired from the generic composition of CBC+MAC mode allowing a moderate performance by the use of integrated authentication scheme and optimize the implementation. However, it remains less efficient in term of performance than GCM and OCB,

- -

- GCM is an improved incorporation of CTR mode encryption mechanism with an integrated internal MAC allowing parallelizable operation and thus a better performances and resources efficiency. Nevertheless, GCM parallelization feature have a significant impact only on high-speed hardware-based applications. In TOR context, because the cryptographic operation are performed on software basis the GCM mode performance was not optimal and hence not as well as OCB.

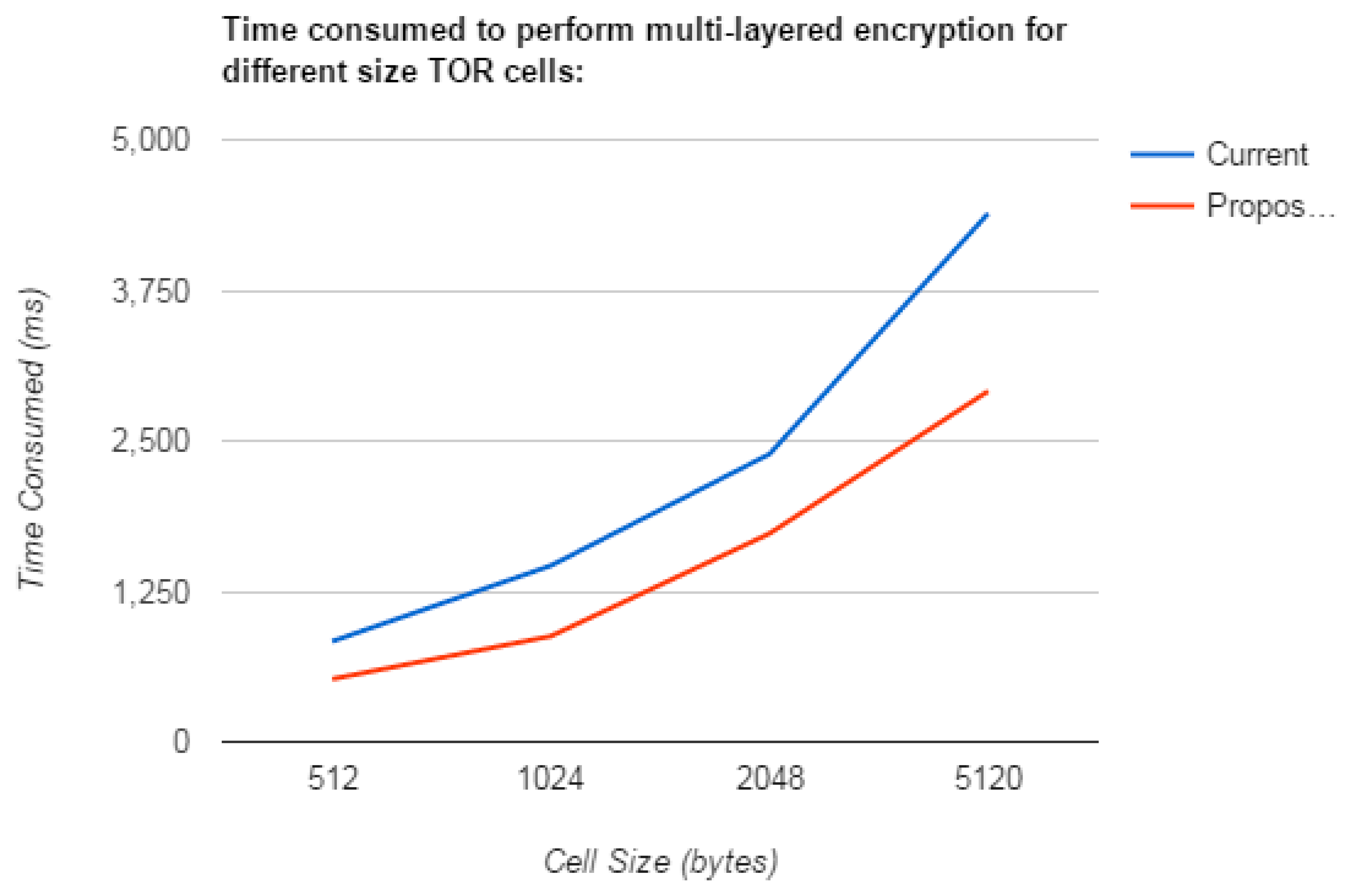

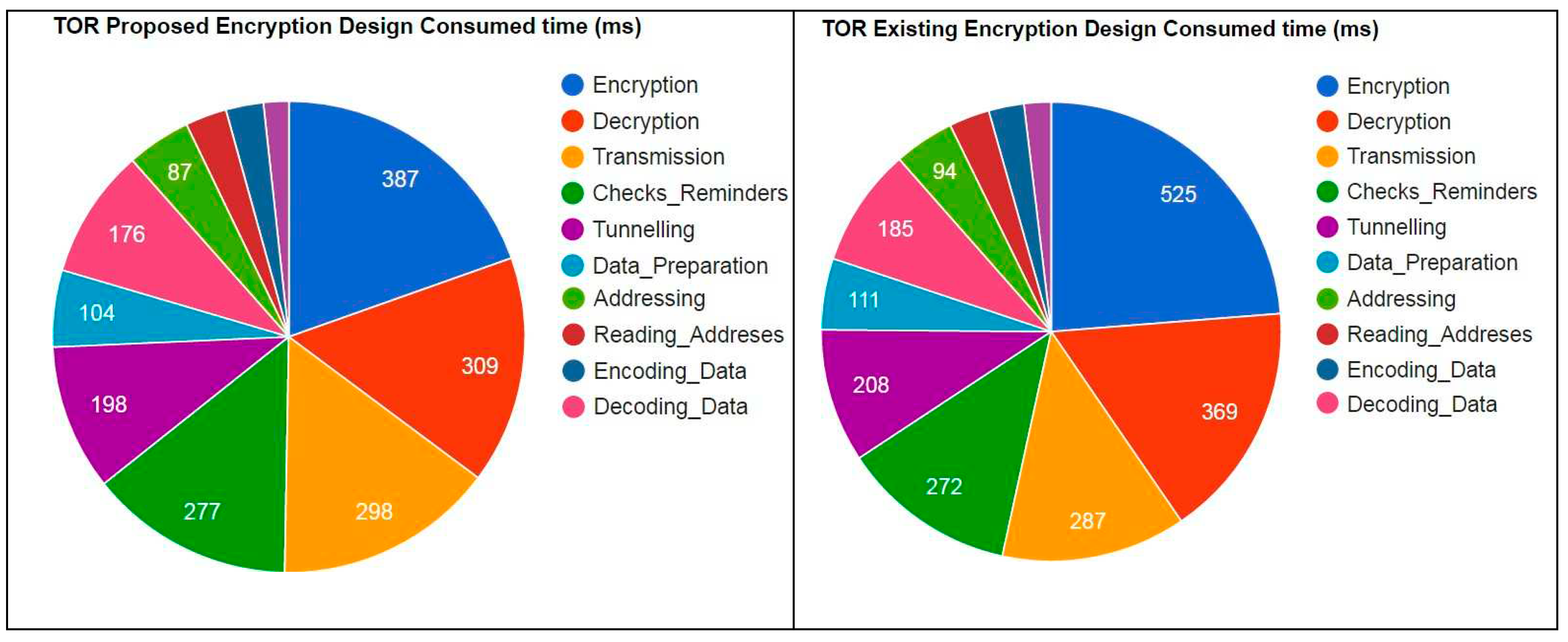

5.4.2. The Onion construction (Encapsulation)

- a)

- Obtained results:

| Cell Size (Bytes) | 512 | 1024 | 2048 | 5120 |

| Current TOR Cryptosystem (ms) | 834.81 | 1463.65 | 2390.03 | 4388.41 |

| Proposed Cryptosystem (ms) | 521.90 | 877.74 | 1730.11 | 2912.43 |

- b)

- Discussion of the obtained results:

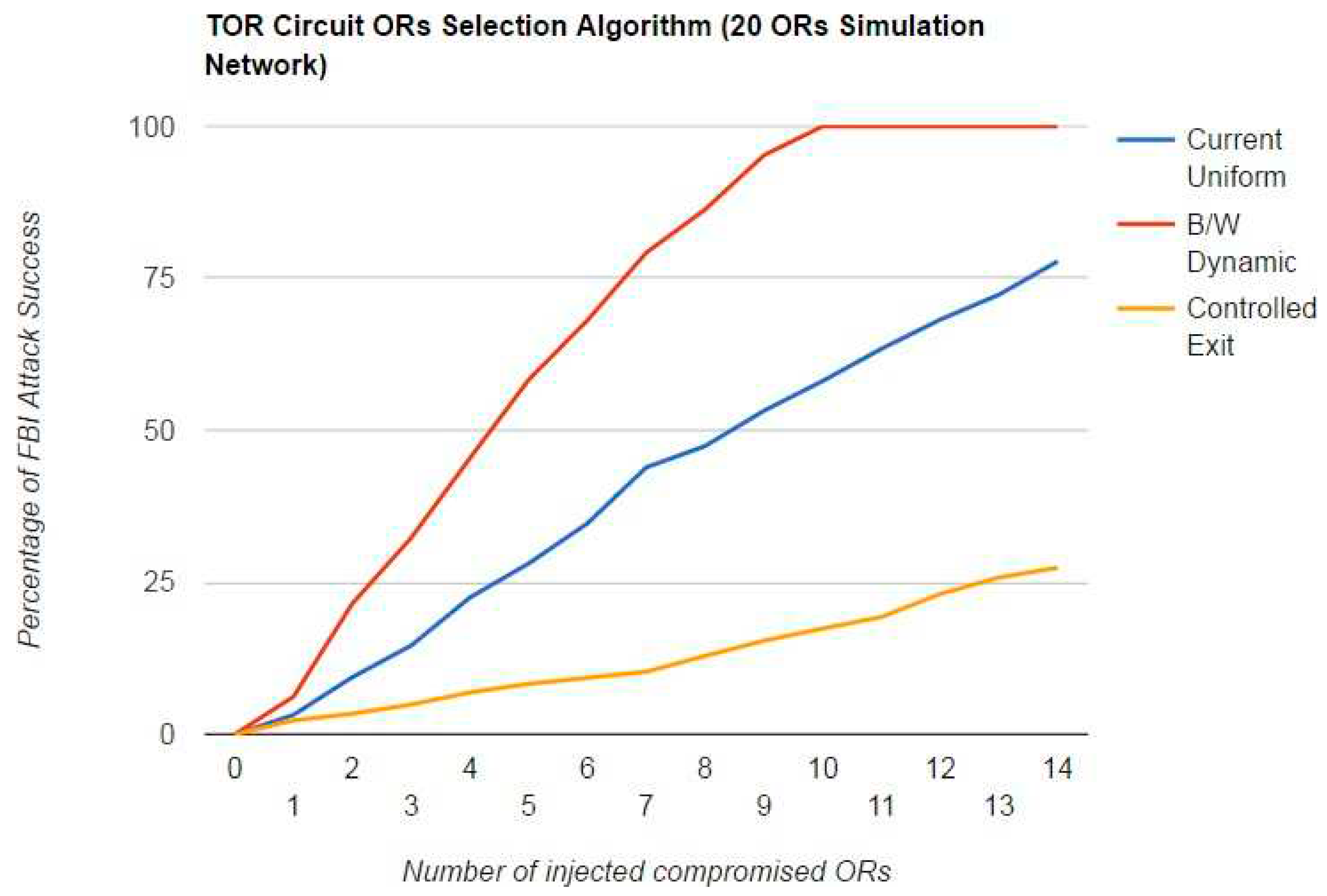

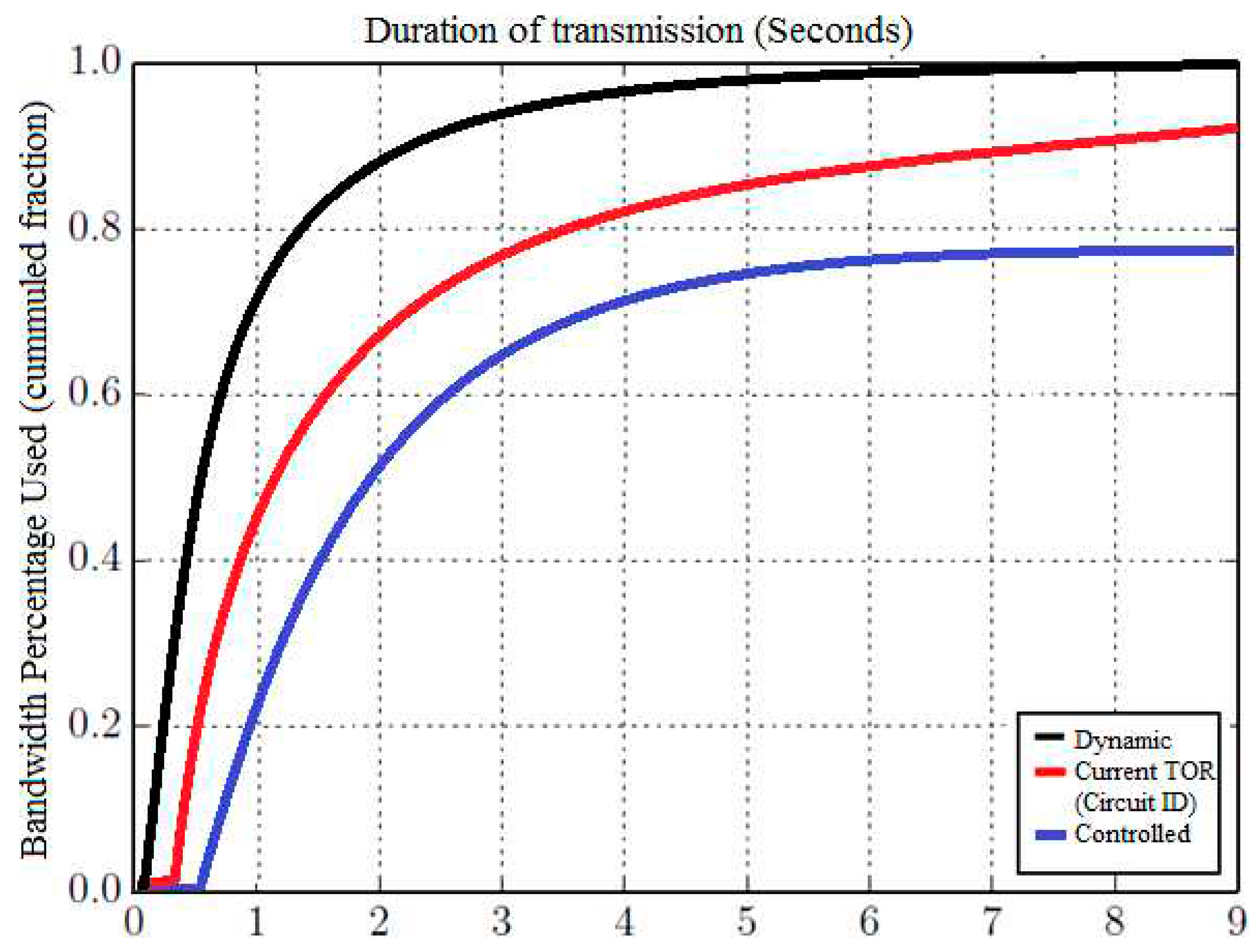

5.4.3. ORs Selection and Circuit Construction testing

- -

- Bandwidth-Weighted algorithm optimised by a combination of Dekjstra and A* algorithms,

- -

- Controlled Exit OR Algorithm with random intermediate selection.

- c)

- Obtained results:

- d)

- Results discussion:

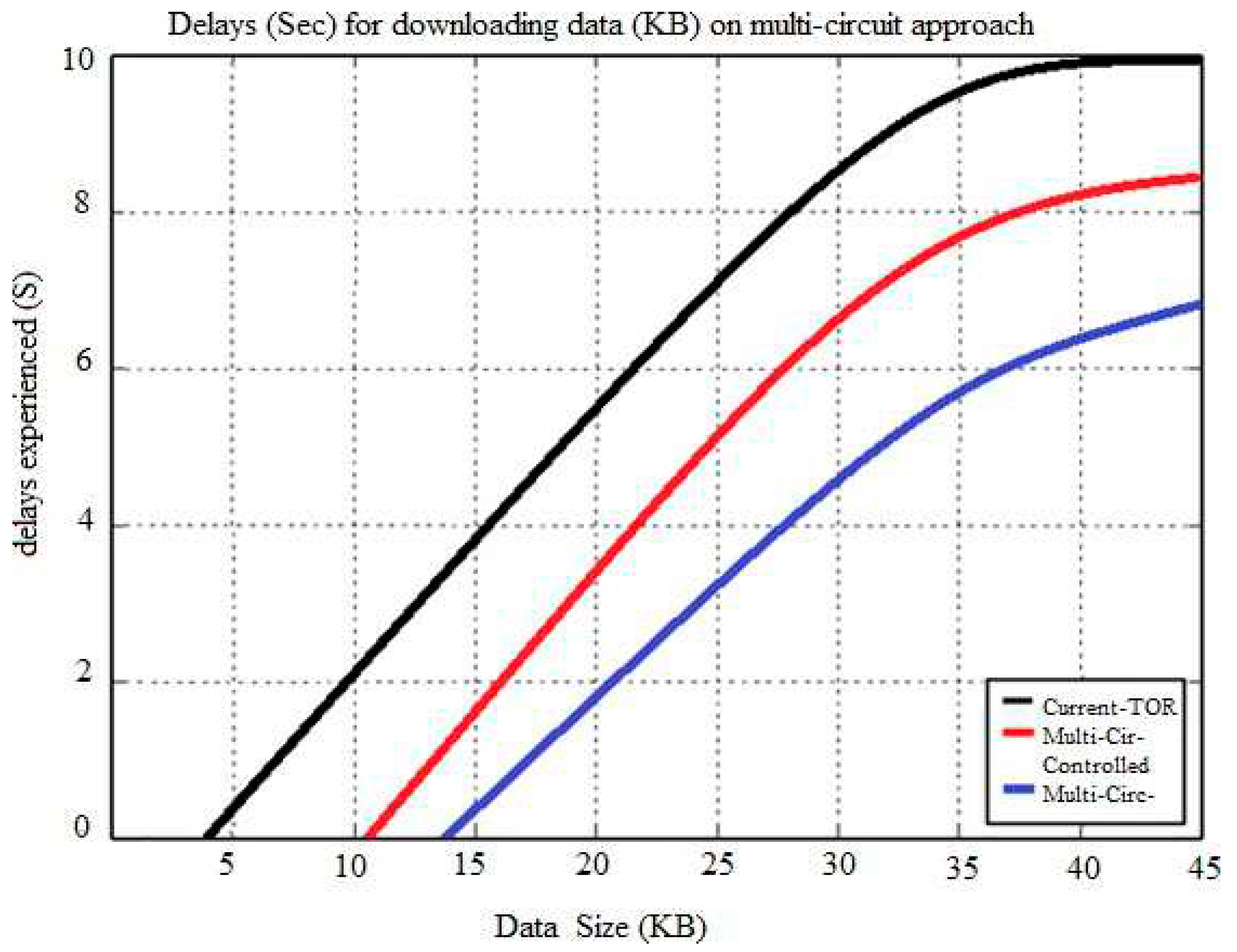

5.4.4. The Multi-circuit routing testing and results

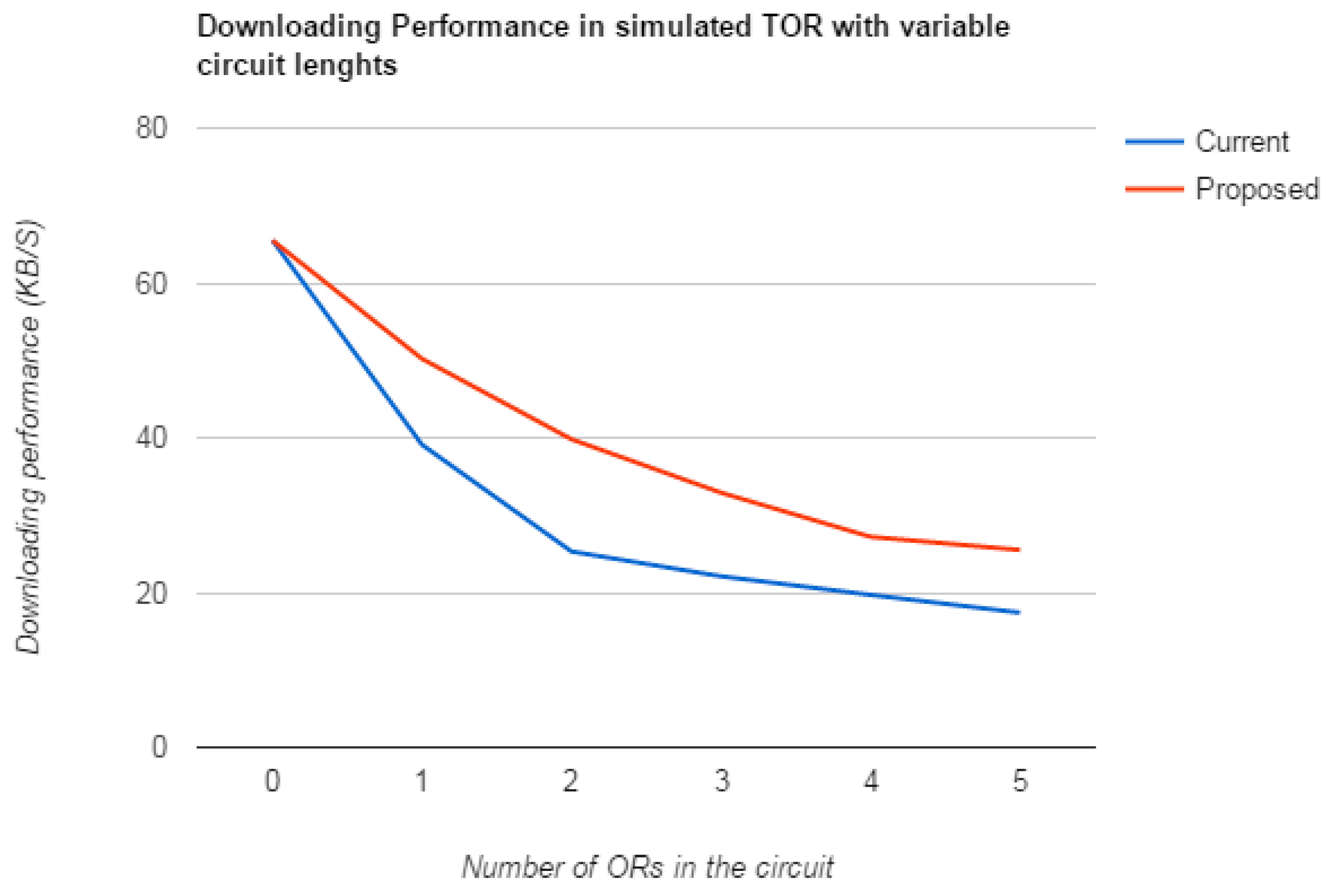

5.4.5. The dynamic circuit length results and discussion

| Number of ORs in the circuit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| TOR current deployment performance (KB/S) | 65.5 | 39.1 | 25.3 | 22.1 | 19.7 | 17.4 |

| Proposed enhancement performance (KB/S) | 65.5 | 50.2 | 39.8 | 32.9 | 27.2 | 25.5 |

5.5. Results’ validation and findings summary

Chapter 6: Conclusion

6.1. Work output and conclusion

6.2. Further works

6.3. Work Evaluation

6.4. Reflective and Critical Evaluation

6.5. Personal development and Skills Improvement

- -

- Project management skills including time management, scope management and risk management,

- -

- Requirements analysis skills,

- -

- Virtualisation and the use of complex computing enviorments,

- -

- FreeBSD and Open Source virtual routing,

- -

- Fortification of my skills in Java programming and the use of design patterns,

- -

- Python Programming skills,

- -

- C++ advanced development skills,

- -

- Academic research skills,

- -

- Testing cryptographic program efficiency and simulating anonymity network functioning and features,

- -

- Capacity to overcome problems that emerge during the different stages of the work.

Acknowledgements

Frequently used terms and acronyms

| Onion Proxy | OP is the client side of TOR (the software) running on behalf of the user machine and ensure communication with the network (create cells, perform encryption and decryption, manage circuit and routing … etc.). |

| Onion Router | OR is TOR dedicated software router ensuring routing cells throughout the network and performing wrapping and un-wrapping (encryption/decryption). |

| Bandwidth | the volume of traffic (incoming and outgoing) that a OR could sustain. The information is retrieved from the operator claimed capacity or DA observed. |

| Directory Authority | DA is a special dedicated server managed by the TOR and maintains all the information about the ORs and links status. |

| Circuit | called also path is the route through the TOR network built by used by a client and consists of an entry (guard) OR, middle(s) OR and Exit OR. |

| Hidden Service | HS is location and functioning not public internet service that only TOR user can access. |

| AES | The Advanced Encryption Standard (Rijndael) is a secret key (symmetric) encryption. |

| RSA | public-key (asymmetric) encryption algorithm. |

| DH | Diffie–Hellman key exchange algorithm. |

| MAC | Massage Authentication Code (also called MIC) |

| Hash | one way function used to map data of arbitrary size to data of fixed size for integrity and authenticity purposes. |

| CBC | the Cipher Block Chaining encryption mode. |

| CTR | Counter-mode encryption mode. |

| OCB | Offset Codebook Mode authenticated encryption mode. |

| CCM | Counter with CBC-MAC authenticated encryption mode. |

| GCM | Galois/Counter Mode authenticated encryption mode. |

| EAX | Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) |

| TCP/IP | Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol. |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security. |

| Cell | the TOR equivalence for packets, a fixed size data structured into a specific way. |

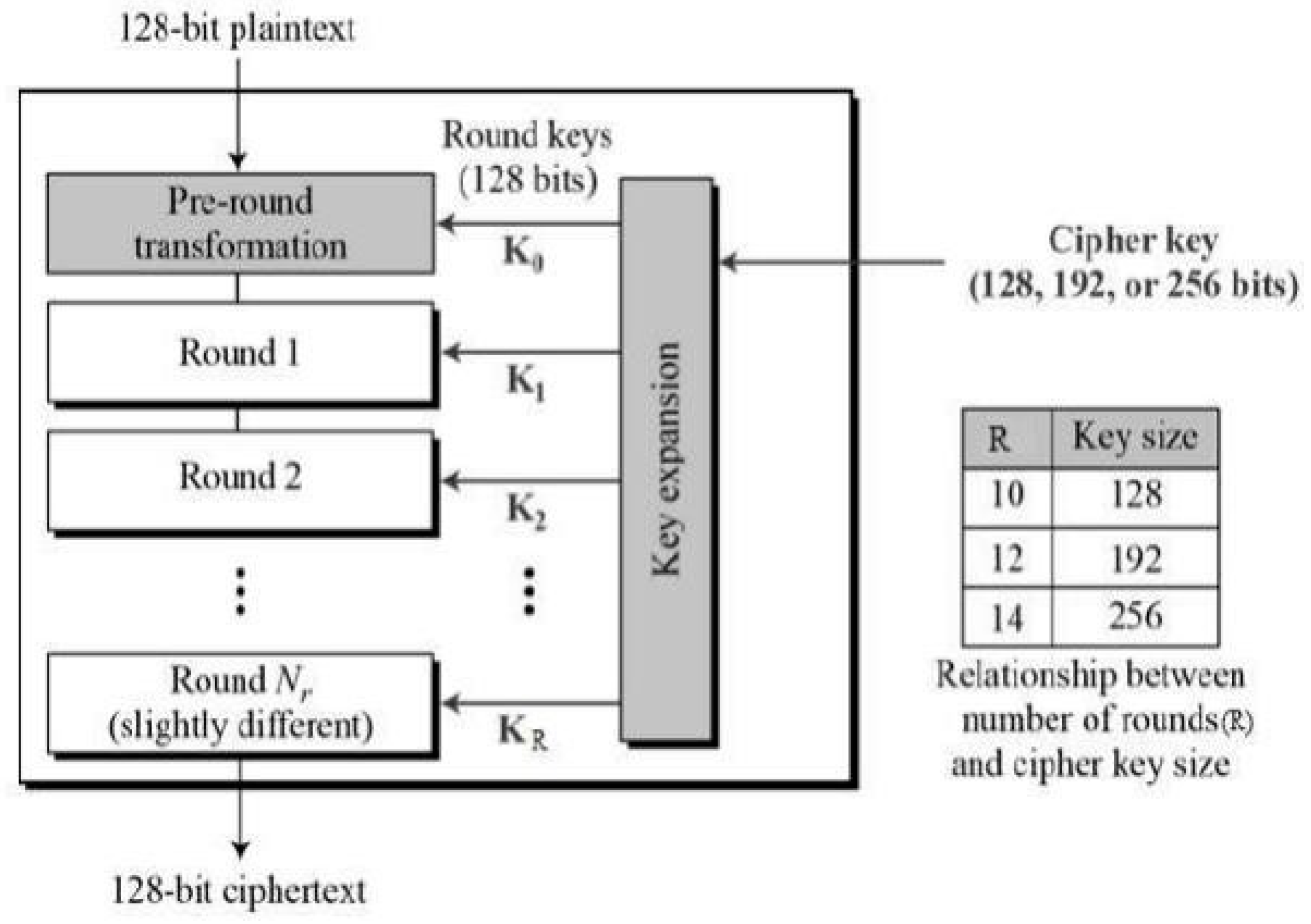

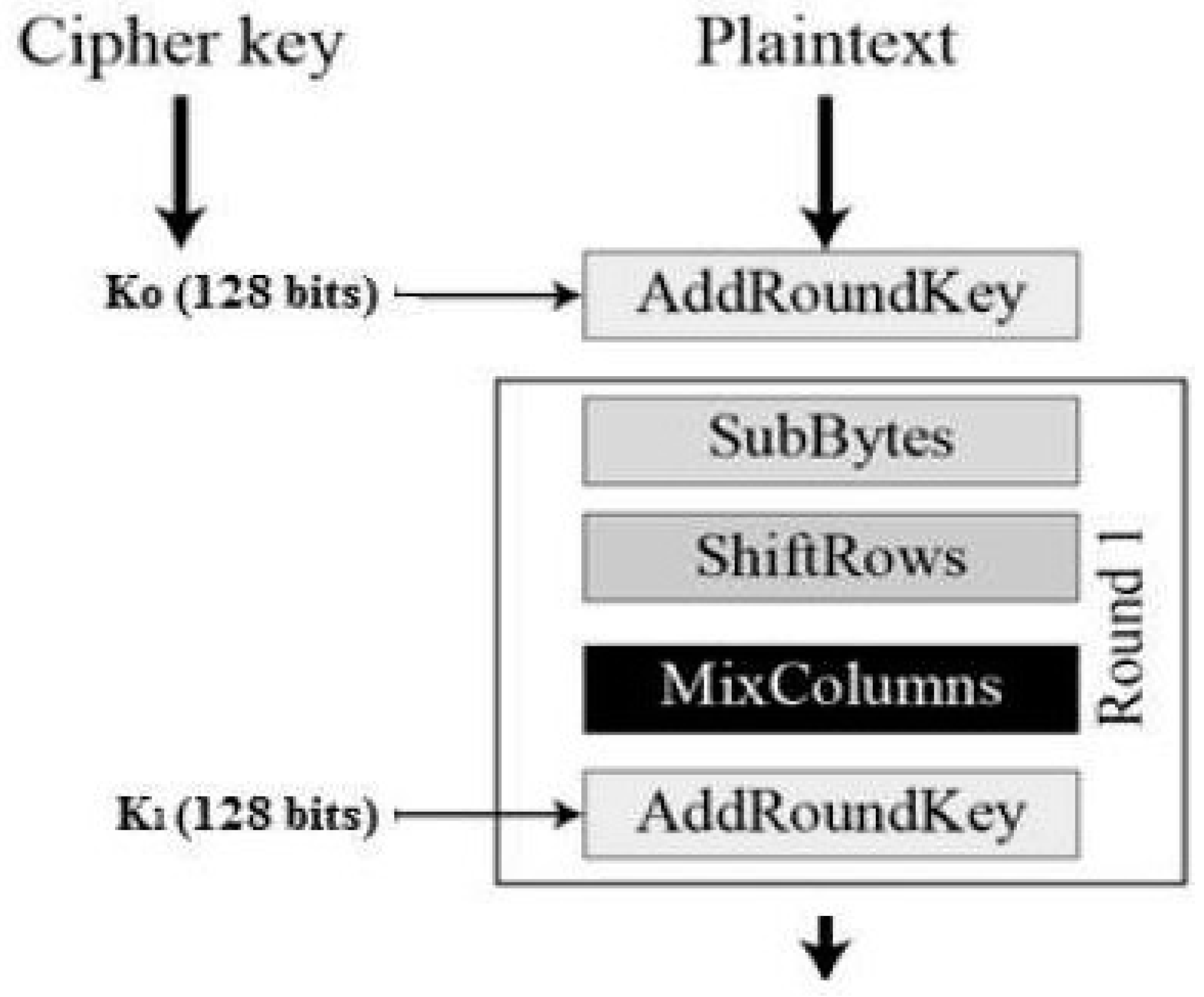

Appendix 1: Advanced Encryption Standard AES algorithm

- -

- In a block and key size of 128 bits, there are 10 computation rounds,

- -

- In a block and key size of 192 bits, there are 12 computation rounds,

- -

- In a block and key size of 256 bits, there are 14 computation rounds.

- Operation of AES:

- Encryption Process:

- AES Functions:

- AES Analysis

- AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) detailed scheme

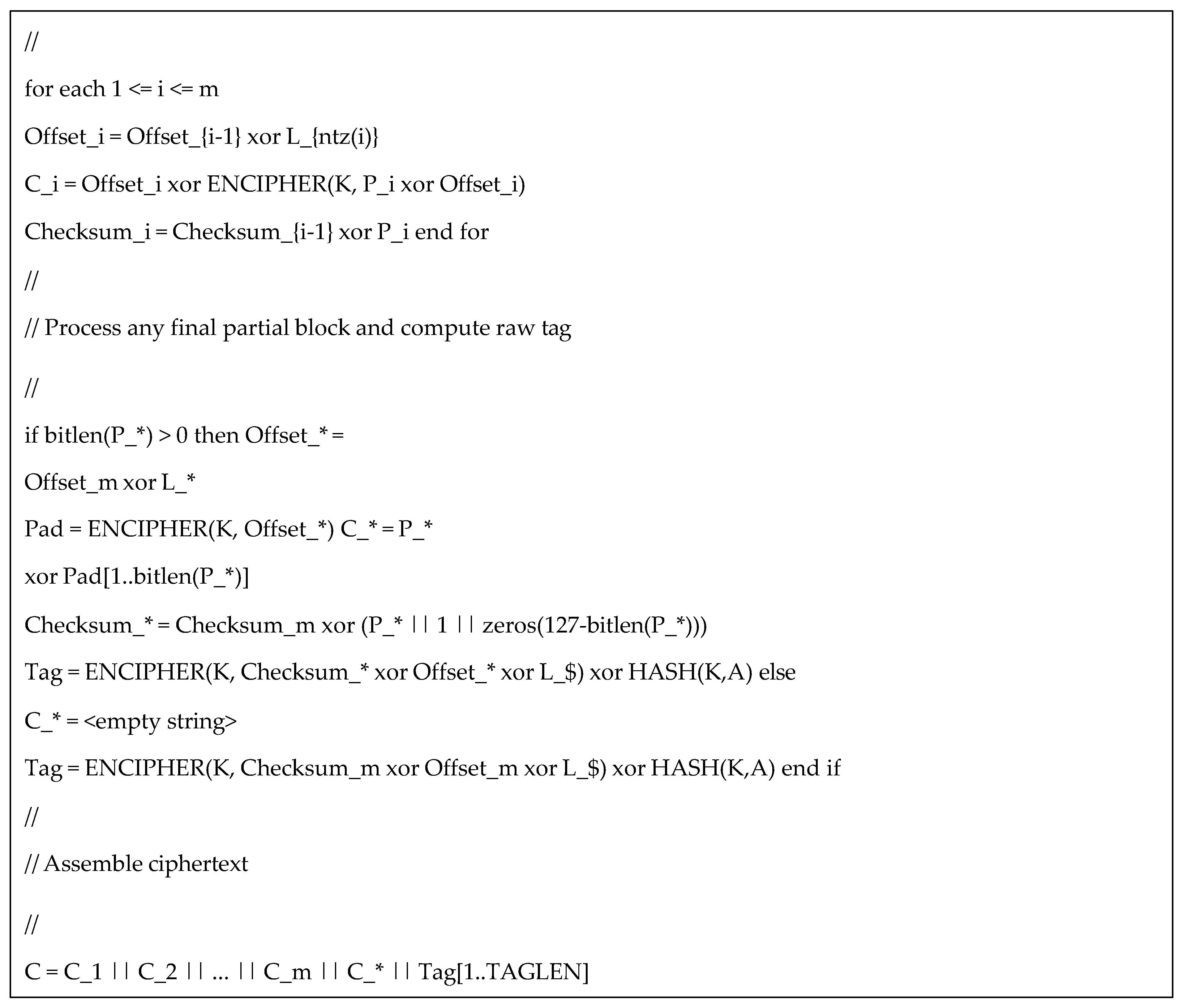

Appendix 2: Authenticated-encryption OCB Mode

References

- AlSabah, M. and Goldberg, I. (2015). Performance and Security Improvements for Tor: A Survey. Available online: http://eprint.iacr.org/2015/235.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., Elahi, T. and Goldberg. (2013a). The Path Less Travelled: Overcoming Tor’s Bottlenecks with Traffic Splitting. In Privacy Enhancing Technologies - 13th International Symposium, PETS 2013, Bloomington, IN, USA, July 10-12, 2013. Proceedings. Springer, 143–163.

- AlSabah, M. and Goldberg, I. (2013b). PCTCP: Per-Circuit TCP-over-IPsec Transport for Anonymous Communication Overlay Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS’13, Berlin, Germany, 349–360.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., and Goldberg, I. (2012). Enhancing Tor’s Performance Using Real-Time Traffic Classification. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS ’12). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 73–84.

- AlSabah, M., Bauer, K., Goldberg, I., Grunwald, D., McCoy, D., Savage, S. and Voelker, G. (2011). DefenestraTor: Throwing Out Windows in Tor. In Privacy Enhancing Technologies. 11th International Symposium, PETS 2011, Waterloo, ON, Canada, July 27-29, 2011. Proceedings. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 134–154.

- Antonakakis, M., Edman, M. and Syverson, P. (2009). As-Awareness in TOR Path Selection. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS 2009, Chicago, Illinois, USA, ACM 380–389.

- Backes, M., Goldberg, I., Kate, A., & Mohammadi, E. (2012). Provably Secure and Practical Onion Routing.

- Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), 25, 369-385.

- Bauer, K. and Sherr, M. (2011). ExperimenTor: A Testbed for Safe and Realistic Tor Experimentation. USENIX 2011. Available online: http://www.usenix.org/events/cset11.

- Bauer, K., Mccoy, D., Sherr, M. and Grunwald, D. (2011). ExperimenTOR: A test-bed for safe and realistic tor experimentation. In Proceedings of the USENIX Workshop on Cyber Security Experimentation and Test (CSET). Bogdanov, A., Lauridsen, M. and Tischhauser, E. (2014). AES-Based Authenticated Encryption Modes in Parallel High-Performance Software. IEEE library.

- Fu, X. and Ling, Z. (2009). One Cell is enough to break Tor’s Anonymity. White Paper for Black Hat DC 2009. Boyd, W. (2011). A Simulation of Circuit Creation in Tor. Master thesis, submitted at Wesleyan University, Connecticut April, 2011.

- Benmeziane. S., Badache. N. & Bensimessaoud. S. (2011). Tor Network Limits. International Conference on Network Computing and Information Security, 1, 200-205.

- Burstein, A. J. (2008). Conducting cyber security research legally and ethically. 1st USENIX Workshop on Large- Scale Exploits and Emergent Threats, Berkeley, CA, USA, pages 1-8. USENIX Association.

- Camenisch, J., Lysyanskaya, A. (2005). A formal treatment of onion routing. 25th Annual International Conference in Advances in Cryptology CRYPTO 2005, 169-187.

- Carnielli, A. and Aiash, M. (2015). Will TOR Achieve its Goals in the Future Internet? An Empirical Study of using TOR with Cloud Computing. 2015 29th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops.

- Casenove, M., Miraglia, A. (2014). Botnet over Tor: The Illusion of Hiding. 6th International Conference on Cyber Conflict P.Brangetto, M.Maybaum, J.Stinissen (Eds.), NATO CCD COE Publications, Tallinn.

- Castelluccia, C., De Cristofaro, E. and Perito, D. (2010). Private information disclosure from web searches. In Mikhail J. Atallah and Nicholas J. Hopper, editors, Privacy Enhancing Technologies, 6205 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 38-55.

- Dahal, S., Lee, J., Kang, J. and Shin, S. (2015). Analysis on End-to-End Node Selection Probability in TOR Networking, IEEE ICOIN 2015. ISBN 978-1-4799-8342-1/15.

- Danezis, G. Diaz, C. and Syverson, P. (2010). Systems for Anonymous Communication. In CRC Handbook of Financial Cryptography and Security, CRC Cryptography and Network Security Series, B. Rosenberg, and D. Stinson (Eds.), 341-390.

- Darcie, W., Boggs, R., Sammons, J. and Fenger, T. (2013). Online Anonymity: Forensic Analysis of the Tor Browser Bundle. ICDFSC 2013.

- Dingledine, R. and Mathewson, N. (2016a). TOR Directory Specification. Available online: https://gitweb.etorproject.org/torspec.git/tree/dir-spec.txt (accessed on March 2016).

- Dingledine, R. and Mathewson, N. (2016b). TOR Protocol Specification. Available online: https://gitweb.torproject.org/torspec.git/tree/tor-spec.txt (accessed on March 2016).

- Dingledine, R., Mathewson, N. & Syverson, P. (2004). Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router. 13th Security Symposium (USENIX), 303–320.

- Dingledine, R., Mathewson, N., Murdoch, S. & Syverson, P. (2014). Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router Draft 2014. Available online: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/ (accessed on 11 February 2014).

- Douceur, J. (2002). The Sybil Attack. In: Proceedings of the 1st International Peer To Peer Systems Workshop (IPTPS 2002). Volume 2429 of LNCS, Springer.

- Feigenbaum, J., Johnson, A. and Syverson, P. F. (2007). Probabilistic analysis of onion routing in a black-box model. 6th ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (WPES), 1–10.

- Goldberg, I., Stebila, D. and Ustaoglu, B. (2012). Anonymity and one-way authentication in key exchange protocols. IEEE ICPA 2012.

- Haraty, R.A. & Zantout, B. (2014). The TOR Data Communication System: A Survey. Journal of Communications and Networks, 16, 415-420.

- Huhta, O. (2014). Linking Tor Circuits. MSc Information Security dissertation submitted to University College London.

- Jansen, R., Geddes, J., Wacek, C., Sherr, M. and Syverson, P. (2014). US Never Been KIST: Tor’s Congestion Management Blossoms with Kernel-Informed Socket Transport. Proceedings of the 23rd USENIX Security Symposium, San Diego, CA ISBN 978-1-931971-15-7.

- Johnson, A., Wacek, C., Jansen, R., Sherr, M. and Syverson, P. (2010). Users Get Routed: Traffic Correlation on Tor by Realistic Adversaries, Association for Computing Machinery, ACM, US.

- Kate, A. and Goldberg, I. (2010). Distributed Private-Key Generators for Identity-Based Cryptography. 7th Conference on Security and Cryptography for Networks (SCN), 436–453.

- Krovetz, T. and Rogaway, P. (2014).OCB implementation and performance analysis. IETF RFC publications. Lazzari, M. (2014). Systematic Testing of Tor. Submitted as Master Thesis, ETH Zurich.

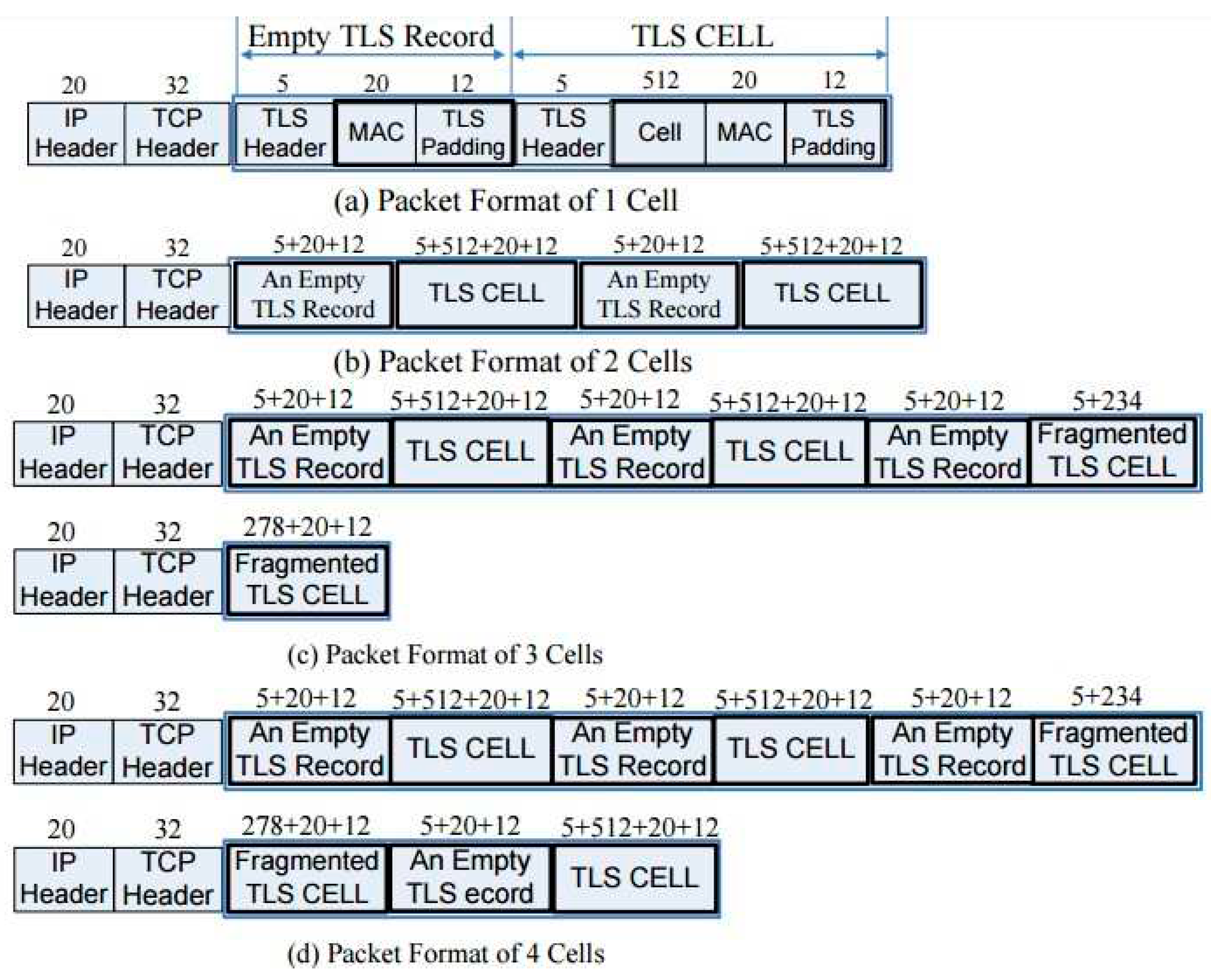

- Ling, Z., Luo, J., Yu, W. and Fu, X. (2011). Equal-sized Cells Mean Equal-sized Packets in TOR. IEEE Communications Society subject matter experts for publication in the IEEE ICC 2011 proceedings.

- Marquis, M. (2013). For their eyes only. The Commercialization of Digital Spying citizen lab Canada global security research.

- Mccoy, D., Bauer, K., Grunwald, D., Kohno, T. and Sicker, D. (2008). Shining light in dark places: Understanding the tor network. 8th international symposium on Privacy Enhancing Technologies, PETS '08, 63-76, Berlin.

- Murdoch, S. and Watson, R. (2007). Metrics for Security and Performance in Low-Latency Anonymity Systems. University of Cambridge, UK.

- Nia, M.A., Karbasi, A.H. & Atani, R.E. (2014). Stop Tracking Me: An anti-detection type solution for anonymous data. 4th International eConference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), 14, 685-690.

- Øverlier, L. and Syverson, P. (2006). Locating hidden servers. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, US, IEEE Computer Society.

- Perry, M. (2007). Securing the Tor Network, Black Hat USA 2007 Supplementary Handout.

- Reardon, J. and Goldberg, I. (2010). Improving TOR using a TCP-over-DTLS Tunnel. TOR project research papers. Available online: https://gitweb.etorproject.org.

- Schanck, J., Whyte, W. and Zhang, Z. (2015). A quantum-safe circuit-extension handshake for Tor. Security innovation white paper.

- Singh, S. (2015). Large-Scale Emulation of Anonymous Communication Networks. Matser thesis presented to the University of Waterloo.

- Snader, R. and Borisov, N. (2008). A tune-up for Tor: Improving security and performance in the Tor network. Network & Distributed System Security Symposium, Interne Society.

- Soghoian, C. (2011). Enforced Community Standards for Research on Users of the Tor Anonymity Network.

- Second Workshop on Ethics in Computer Security Research WECSR, 02, St. Lucia.

- Stupples, D. (2013). Security Challenge of TOR and the Deep Web. The 8th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions ICITST 2013.

- Svenda, P. (2012). Basic comparison of Modes for Authenticated-Encryption (IAPM, XCBC, OCB, CCM, EAX, CWC, GCM, PCFB, CS). Masaryk University in Brno.

- Syverson, S., Goldschlog, D. and Reeds, M. (1997). Anonymous connections and onion routing. Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, USA, 482-494.

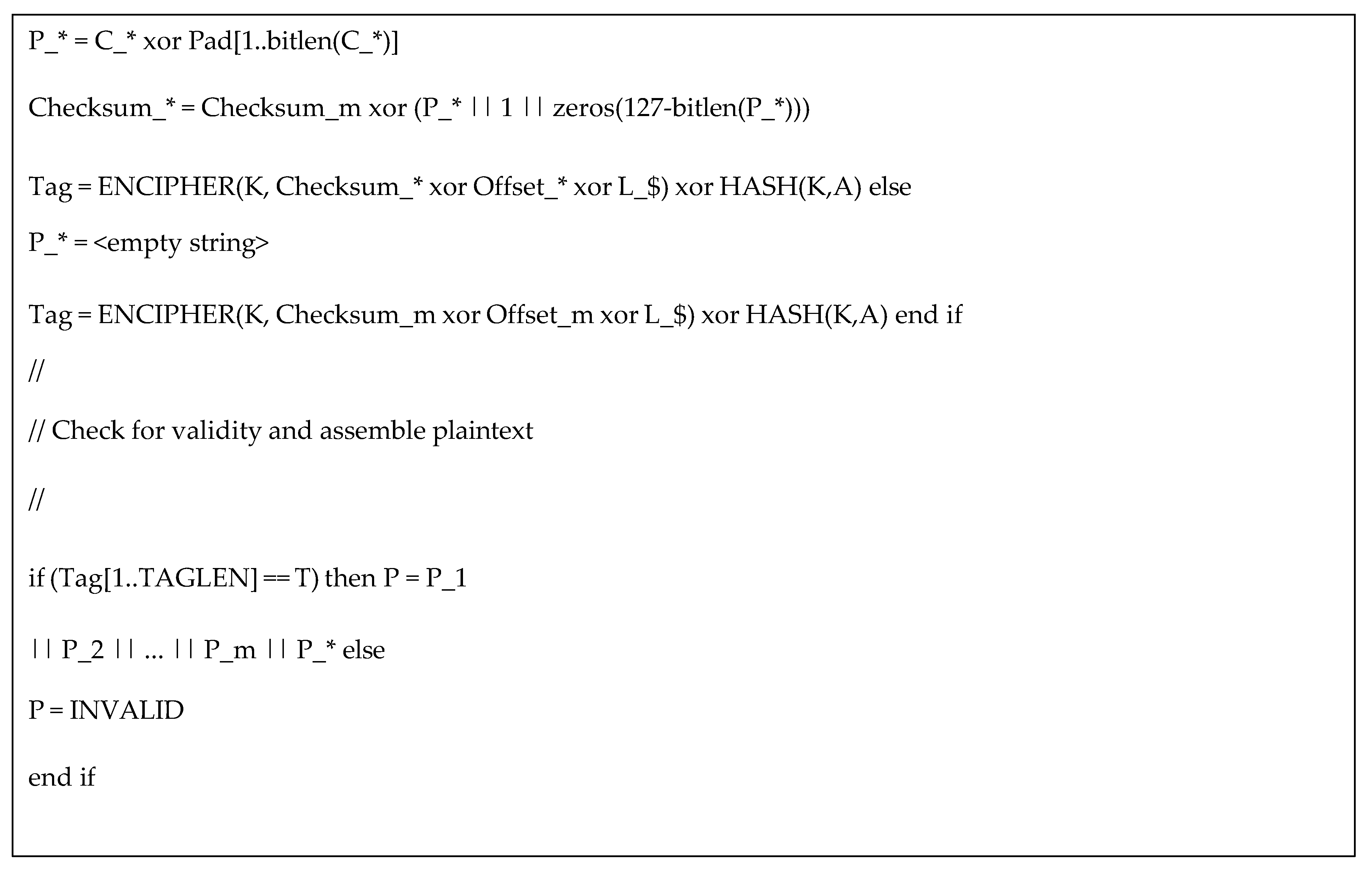

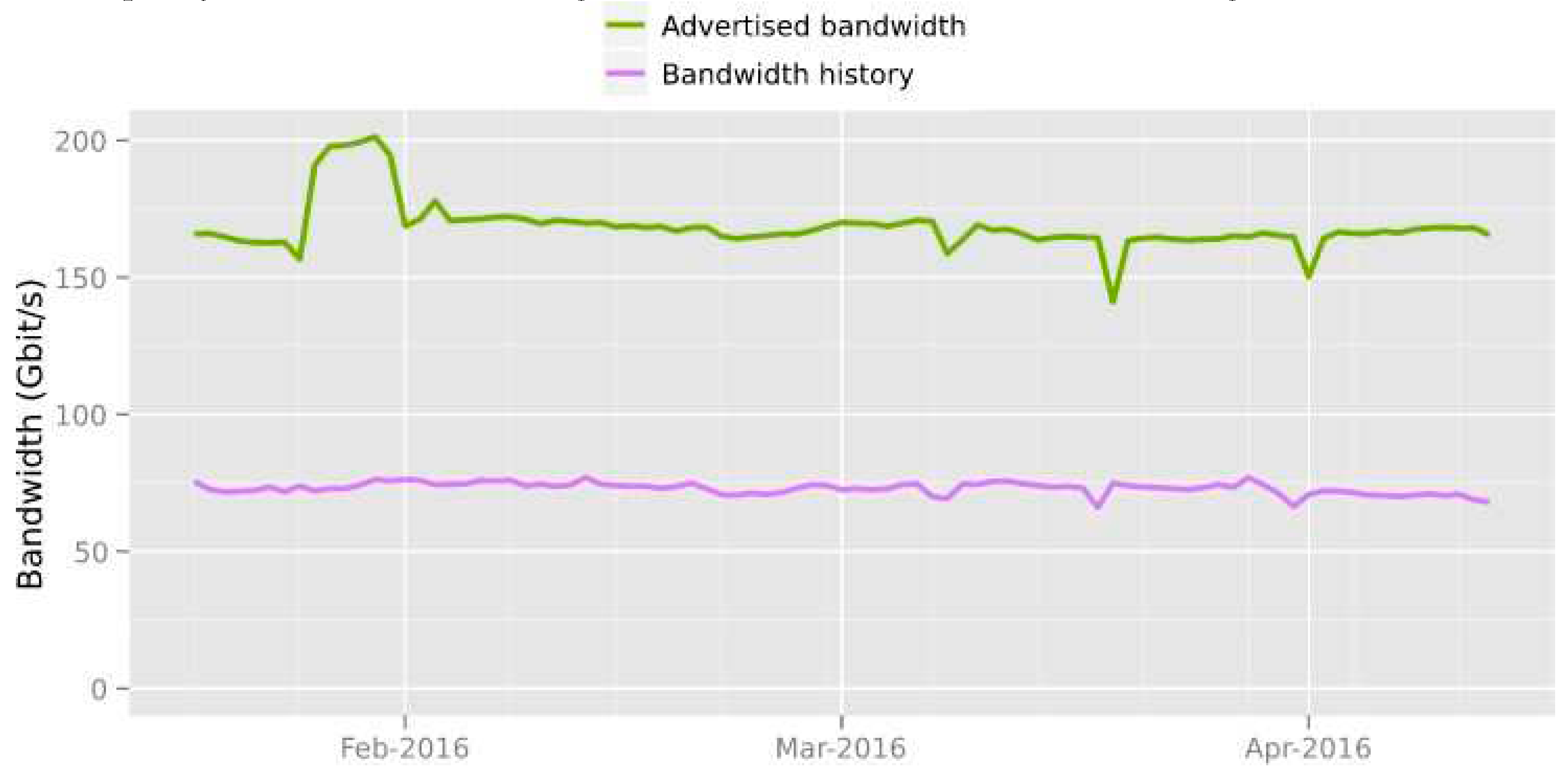

- TOR Deployment. (2016). TOR network detailed deployment. Available online: https://abouttor.tor.org (accessed on April 2016).

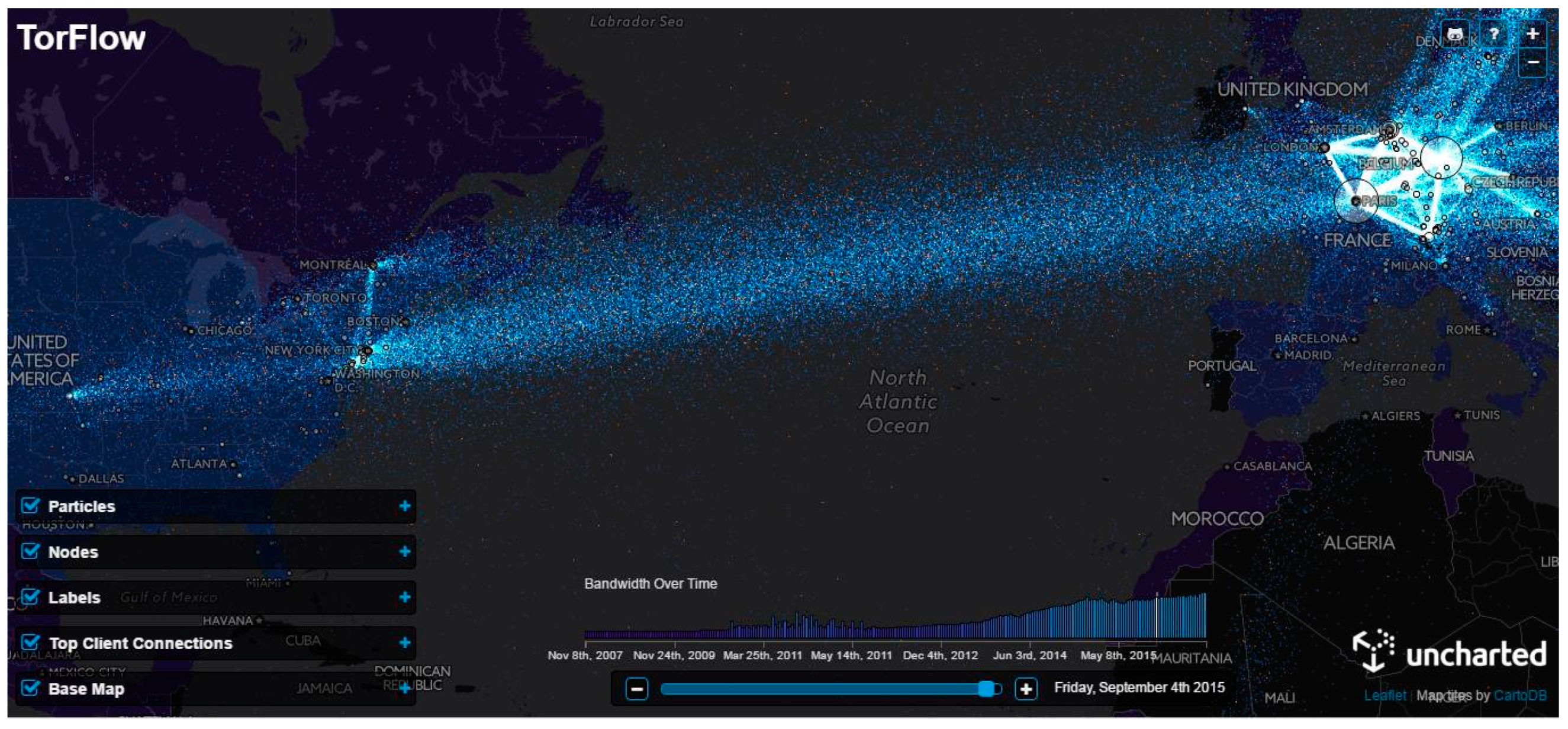

- TOR Flow. (2016). TOR flux across the world. Available online: https://torflow.uncharted.software (accessed on April 2016).

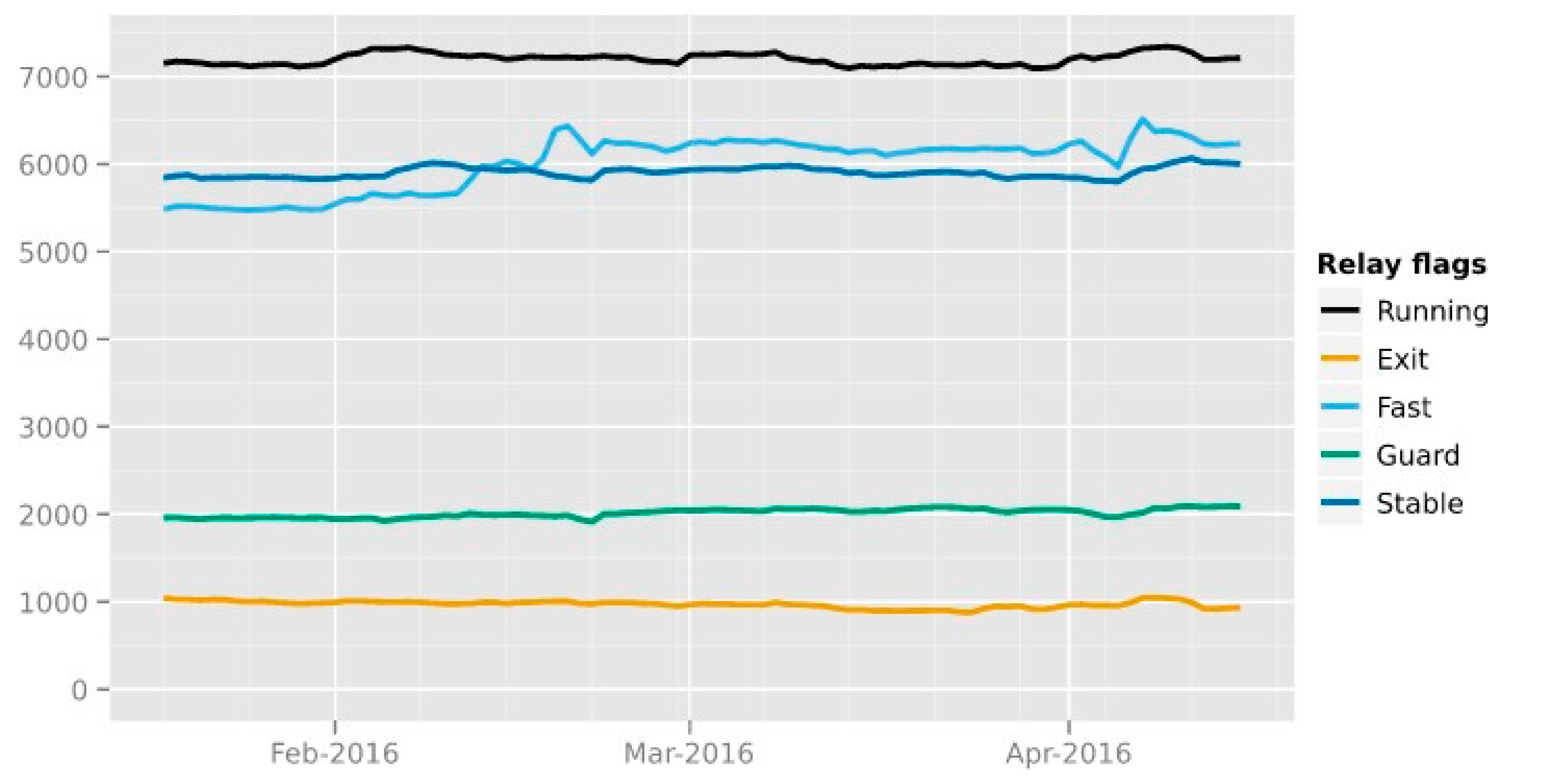

- TOR Project. (2016). TOR active users number in UK. Available online: https://metrics.torproject.org (accessed on April 2016).

- TOR Metrics. (2016). TOR Network overall bandwidth. Available online: https://metrics.torproject.org/bandwidth.html (accessed on April 2016).

- Wacek, C., Tan, H., Bauer, K. and Sherr, M. (2013). An Empirical Evaluation of Relay Selection in TOR. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium - NDSS’13, The Internet Society.

- Yenuguvanilanka, J. and Elkeelany, O. (2007). Performance Evaluation of Hardware Models of Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Algorithm. Tennessee Tech University.

- Zhang, Y. (2009). Effective attacks in the tor authentication protocol. 3th International Conference on Network and System Security, 09, 81-86.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).