Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Commercial Milk Collection and Preparation

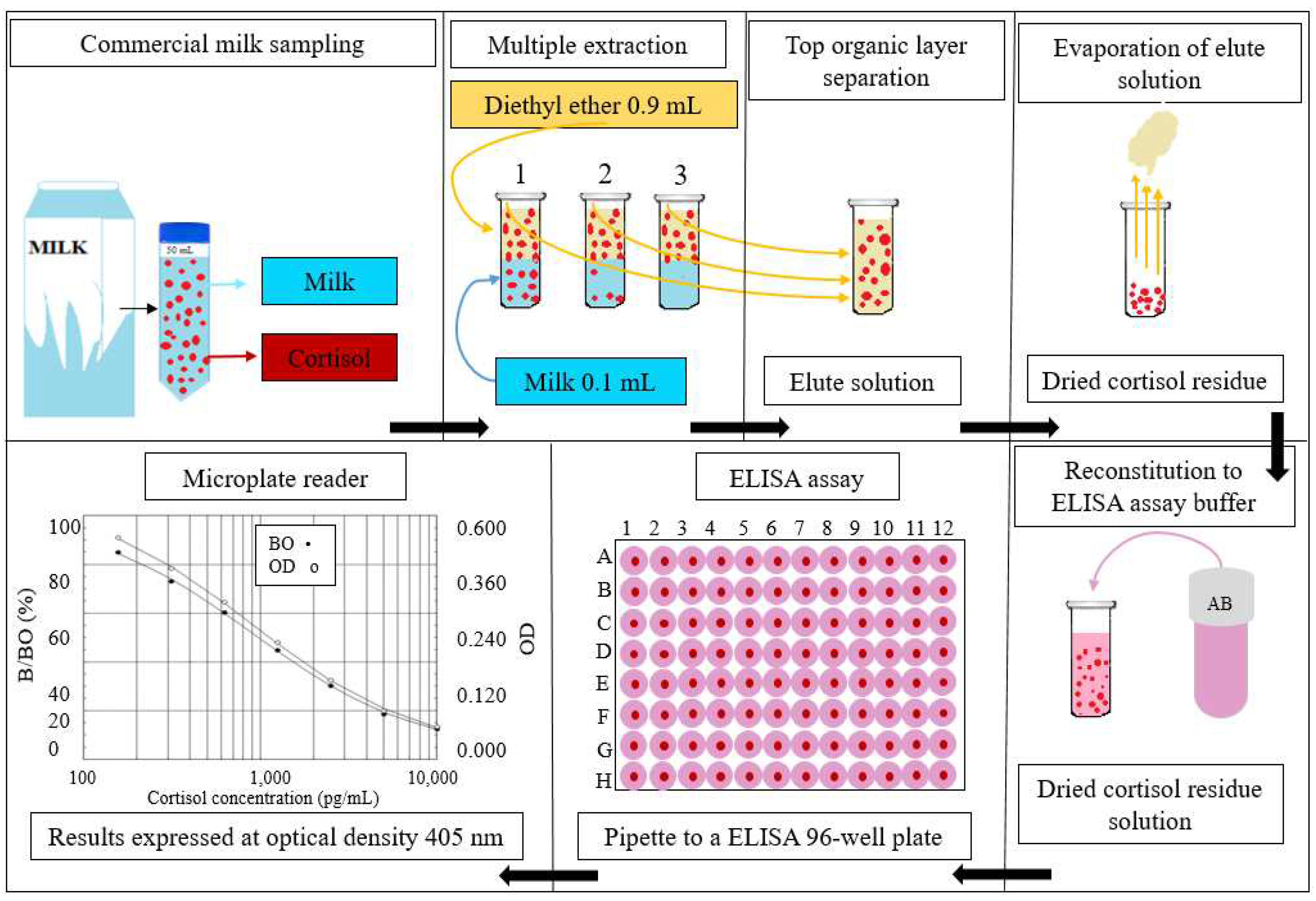

2.2. Milk Cortisol Analysis via Enzyme Immunoassay

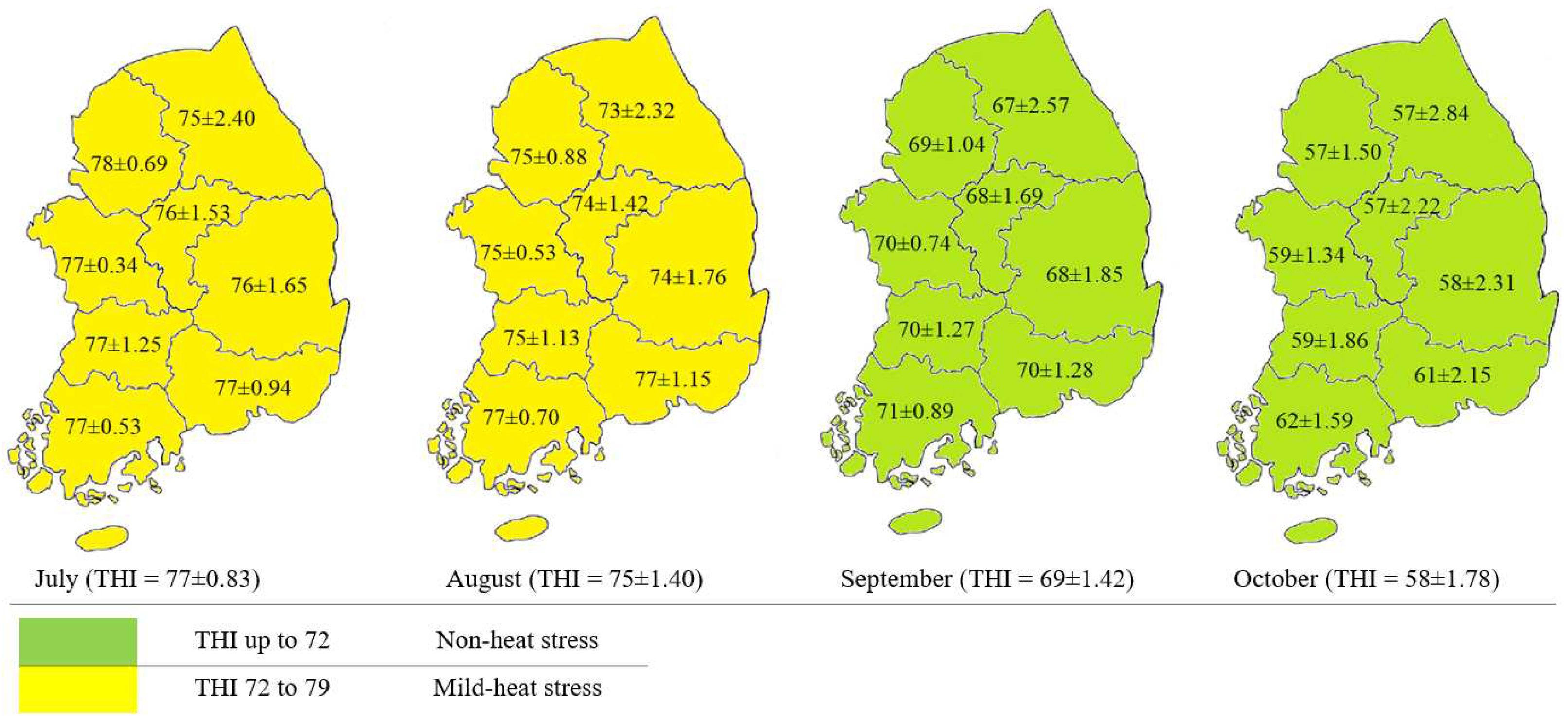

2.3. Temperature-Humidity Index

2.4. Statistical Data Analyses

3. Results

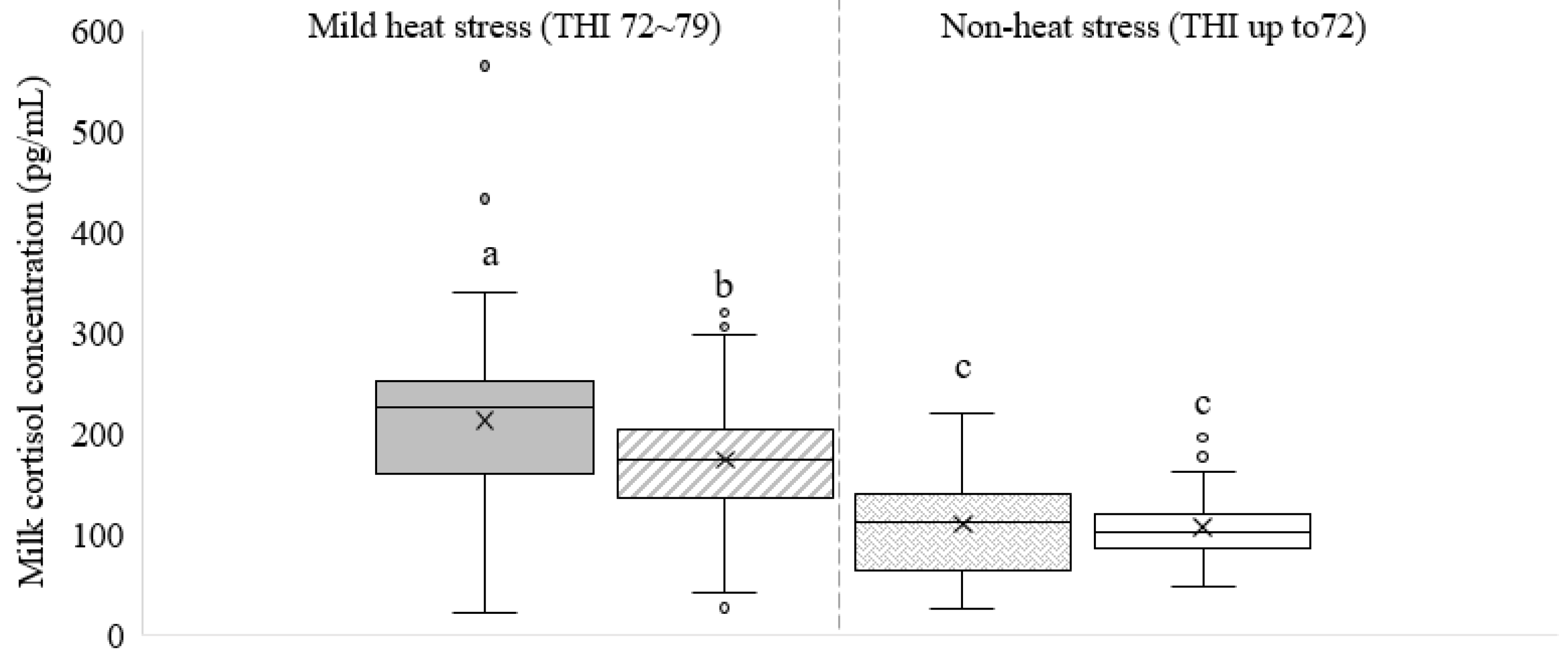

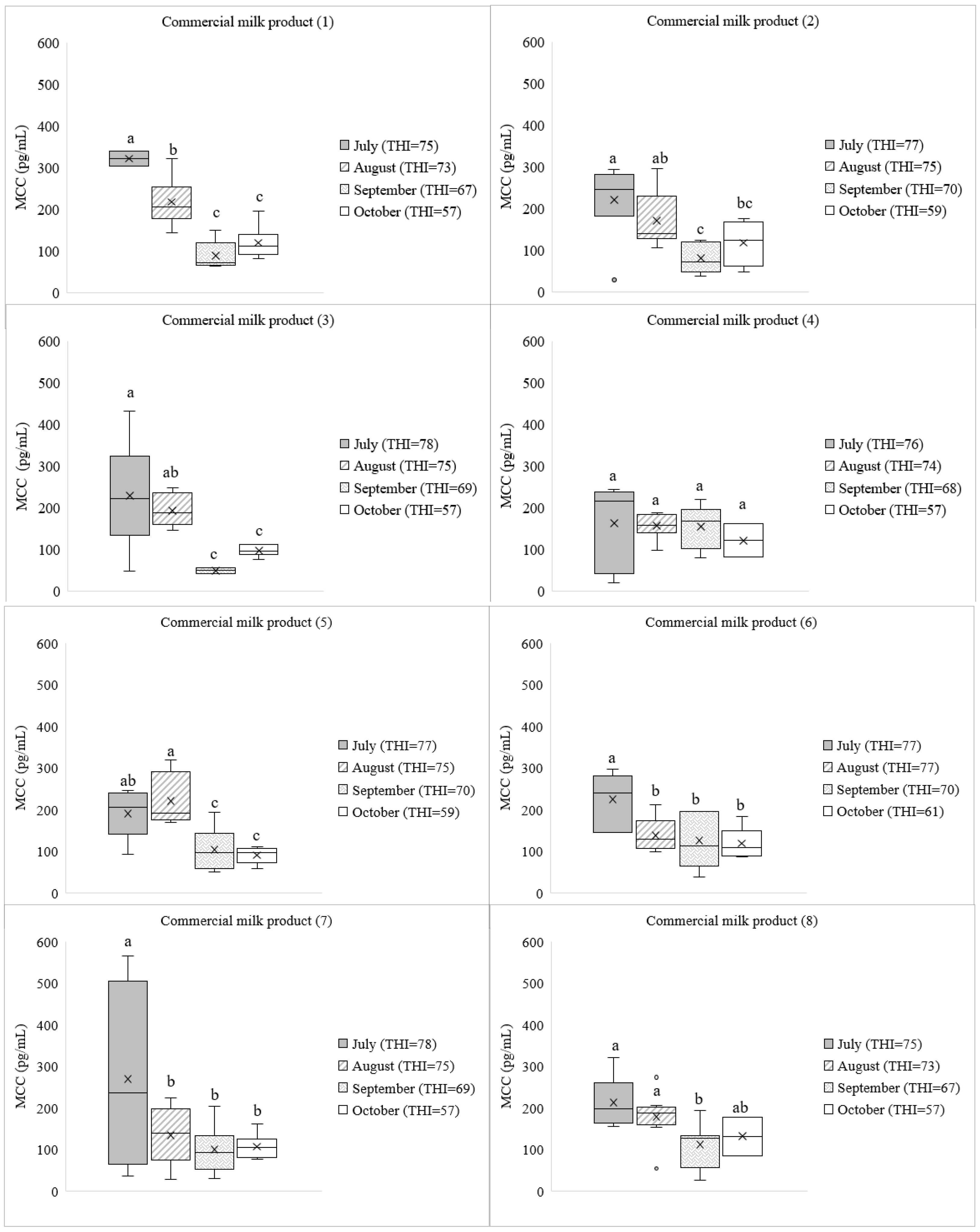

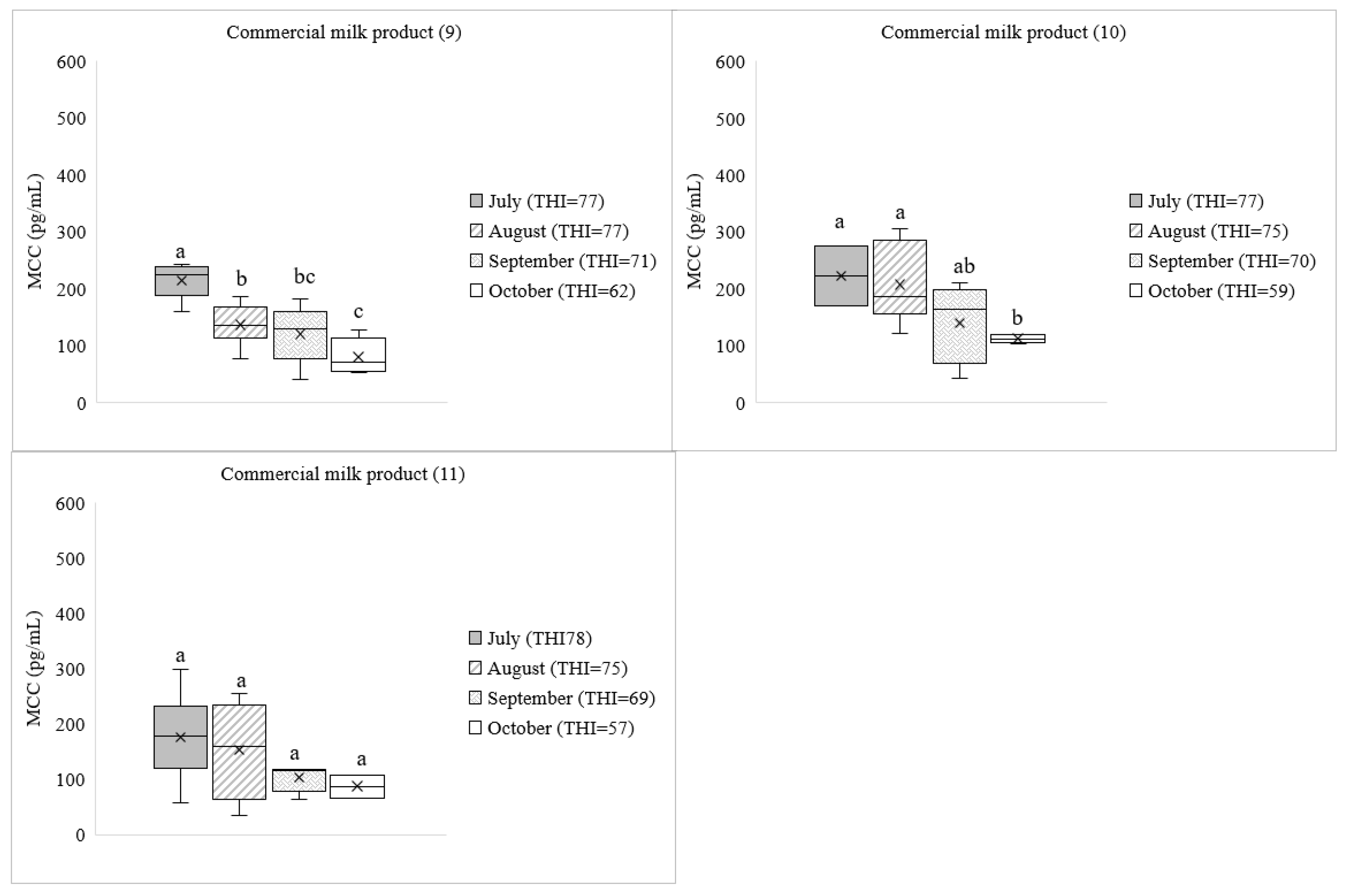

3.1. Cortisol Concentration in Commercial Dairy Milk

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toghdory, A.; Ghoorchi, T.; Asadi, M.; Bokharaeian, M.; Najafi, M.; Ghassemi Nejad, J. Effects of environmental temperature and humidity on milk composition, microbial load, and somatic cells in milk of Holstein dairy cows in the northeast regions of Iran. Animals 2022, 12, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Ataallahi, M.; Jo, J.H.; Lee, H.G. Stress concepts and applications in various matrices with a focus on hair cortisol and analytical methods. Animals 2022, 12, 3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, Y.; Taluja, J.S.; Vaish, R.; Pandey, A.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, D. Gross anatomical structure of the mammary gland in cow. J Entomol Zoo Stud. 2018, 6, 728–733. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, L.; Marangoni, F.; Muscogiuri, G.; D’Incecco, P.; Duval, G.T.; Annweiler, C.; Colao, A. Vitamin D fortification of consumption cow’s milk: Health, nutritional and technological aspects. A multidisciplinary lecture of the recent scientific evidence. Molecules 2021, 26, 5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Lee, B.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Sung, K.I.; Lee, H.G. Daytime grazing in mountainous areas increases unsaturated fatty acids and decreases cortisol in the milk of Holstein dairy cows. Animals 2021, 11, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlhoff, E.; Bennett, A.; McMahon, D. Milk and dairy products in human nutrition. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations (FAO); 2013.

- De Passillé, A.M.; Rushen, J. Food safety and environmental issues in animal welfare. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot. 2005, 24, 757. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Ataallahi, M.; Park, K.H. Methodological validation of measuring Hanwoo hair cortisol concentration using bead beater and surgical scissors. J Anim Sci Technol. 2019, 61, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.; Uddin, J.; Sullivan, M.; McNeill, D.M.; Phillips, C.J. Non-invasive physiological indicators of heat stress in cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataallahi, M.; Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Park, K.H. Selection of appropriate biomatrices for studies of chronic stress in animals: A review. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022, 64, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgorlon, S.; Fanzago, M.; Guiatti, D.; Gabai, G.; Stradaioli, G.; Stefanon, B. Factors affecting milk cortisol in mid lactating dairy cows. BMC Vet Res. 2015, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekinejad, H.; Rezabakhsh, A. Hormones in dairy foods and their impact on public health-a narrative review article. Iran J Public Health 2015, 44, 742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Der Voorn, B.; De Waard, M.; Dijkstra, L.R.; Heijboer, A.C.; Rotteveel, J.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Finken, M.J. Stability of cortisol and cortisone in human breast milk during holder pasteurization. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017, 65, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, R.A.; Bell, E.F.; Colaizy, T.T.; Schmelzel, M.L.; Johnson, K.J.; Walker, J.R.; Ertl, T.; Roghair, R.D. Hormone levels in preterm and donor human milk before and after Holder pasteurization. Pediatr Res. 2020, 88, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, G.E.; Billeaud, C.; Rachel, B.; Calvo, J.; Cavallarin, L.; Christen, L.; Escuder-Vieco, D.; Gaya, A.; Lembo, D.; Wesolowska, A.; Arslanoglu, S. Processing of donor human milk: Update and recommendations from the European milk bank Association (EMBA). Front Pediatr. 2019, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, M.; Tsukada, H.; Kosako, T.; Yamada, A. Effect of lactation stage, season and parity on milk cortisol concentration in Holstein cows. Livest Sci. 2008, 113, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataallahi, M.; Park, G.W.; Kim, J.C.; Park, K.H. Evaluation of substitution of meteorological data from the Korea meteorological administration for data from a cattle farm in calculation of temperature-humidity index. J Climate Change Res. 2020, 11, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S.; Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Peng, D.Q.; Jo, Y.H.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.G. Effects of different protein levels on growth performance and stress parameters in beef calves under heat stress. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.W.; Ataallahi, M.; Ham, S.Y.; Oh, S.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Park, K.H. Estimating milk production losses by heat stress and its impacts on greenhouse gas emissions in Korean dairy farms. J Anim Sci Technol. 2022, 64, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygax, L.; Neuffer, I.; Kaufmann, C.; Hauser, R.; Wechsler, B. Milk cortisol concentration in automatic milking systems compared with auto-tandem milking parlors. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3447–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Aoki, N.; Tsuchiya, A.; Kaneko, S.; Akiyama, K.; Uetake, K.; Suzuki, K. Detection of stress hormone in the milk for animal welfare using QCM method. J Sens. 2017, 2017, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellrich, K.; Sigl, T.; Meyer, H.H.; Wiedemann, S. Cortisol levels in skimmed milk during the first 22 weeks of lactation and response to short-term metabolic stress and lameness in dairy cows. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Su, C.; Zheng, N.; Li, S.; Meng, L.; Wang, J. A survey of naturally-occurring steroid hormones in raw milk and the associated health risks in Tangshan city, Hebei province, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaghi, A.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Rico, D.E. The impact of environmental and nutritional stresses on milk fat synthesis in dairy cows. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2022, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Kamboj, M.L.; Patil, N.V. Effect of thermal protective measures during hot humid season on productive and reproductive performance of Nili-Ravi buffaloes. Indian Buffalo J. 2005, 3, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, F.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; He, M.; Nie, X.; Liu, T. Effect of physiological and production activities on the concentration of naturally occurring steroid hormones in raw milk. Int J Dairy Technol. 2020, 73, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaie, A.H.; Ghasura, R.S.; Mir, N.A.; Bumla, N.A.; Sankar, G.; Wani, S.A. Biochemical and physiological changes during thermal stress in bovines: A review. Iran J Appl Anim Sci. 2013, 3, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Nardone, A.; Ronchi, B.; Lacetera, N.; Ranieri, M.S.; Bernabucci, U. Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livest Sci. 2010, 130, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morignat, E.; Perrin, J.B.; Gay, E.; Vinard, J.L.; Calavas, D.; Henaux, V. Assessment of the impact of the 2003 and 2006 heat waves on cattle mortality in France. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.; Ugurlu, N. Effects of heat stress on dairy cattle. Eurasian J Agric Res. 2017, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, J.H.; Ghassemi Nejad, J.; Peng, D.Q.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.G. Characterization of short-term heat stress in Holstein dairy cows using altered indicators of metabolomics, blood parameters, milk MicroRNA-216 and characteristics. Animals 2021, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papinchak, L.; Paudyal, S.; Pineiro, J. Effects of prolonged lock-up time on milk production and health of dairy cattle. Vet Q. 2022, 42, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gygax, L.; Neuffer, I.; Kaufmann, C.; Hauser, R.; Wechsler, B. Milk cortisol concentration in automatic milking systems compared with auto-tandem milking parlors. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3447–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pragna, P.; Archana, P.R.; Aleena, J.; Sejian, V.; Krishnan, G.; Bagath, M.; Manimaran, A.; Beena, V.; Kurien, E.K.; Varma, G.; Bhatta, R. Heat stress and dairy cow: Impact on both milk yield and composition. Int J Dairy Sci. 2017, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Commercial Milk Products | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Number | Fat (g/100 mL) |

Protein (g/100 mL) |

Heating Process (Temperature-Holding Time) |

| 1 | 3.5 | 3 | Ultra short time (130~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | Ultra short time (125~135 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 3 | 3.6 | 3 | Ultra short time (120~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | Ultra short time (120~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 5 | 3.6 | 3 | Ultra short time (120~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 6 | 3.5 | 3 | Ultra short time (120~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | Ultra short time (120~130 ºC-2~3 seconds) |

| 8 | 1 | 3 | Low temperature low time (63 ºC-30 min) |

| 9 | 3.6 | 3 | Ultra high temperature (135~150 ºC-1~4 seconds) |

| 10 | 3.6 | 3 | Ultra high temperature (135~150 ºC-1~4 seconds) |

| 11 | 3.4 | 3 | Ultra high temperature (135~150 ºC-1~4 seconds) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).