1. Introduction

Landscape Architecture practice in Kenya is one of the relatively new sectors of the already complex construction industry in the Sub-Saharan Country. The practice is currently unregulated compared to the existing AEC practice in the country, leaving room for creating poor-quality Landscape projects due to lack of adherence to the set Global standards of practice for the profession, thus compromising sustainability standards in Landscape Architecture.

Landscape architecture practice has always been at the forefront of sustainable construction practices globally. However, the practice faces significant challenges that impede the realization of a holistic, sustainable construction approach, especially in megaprojects that affect the public population. According to (Sarfo , et al., 2018), emphasis on environmental sustainability is crucial in the overall achievement of sustainable development goals, especially in developing countries where the concept of sustainability is yet to be fully assimilated into their construction process.

According to the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), Sustainable Landscape Architecture should create value through significant environmental, social, and economic benefits by reflecting the views of both private and public sectors. Since the Landscape Architecture practice is relatively new in Kenya, there is a need to ensure that as the practice grows in the country, sustainability assessments and monitoring are a core strategy moving forward to satisfy the global industry standards and trends. This reiterates the importance of addressing the challenges to sustainability policy implementation in Kenya. Therefore, It is paramount to properly analyze the overall challenges obviously faced in monitoring and evaluating sustainable development through landscape project design and build to ensure achieving Environmentally sustainable construction (ESC).

2. Literature Review

According to (Thomas & Anne , 2011), “ “sustainable Landscape Management is a philosophical approach to creating and maintaining landscapes that are ecologically stable and require less inputs”. Sustainable construction practices in Landscape architecture and engineering projects therefore encompasses social, economic, and environmental tiers of a society. Sustainable practices should commence from landscape design to the construction and to the maintenance and post occupancy stages of a project by incorporating the use of sustainable practices, technology, materials, and processes as stipulated in sustainable development principles.

(Sarfo , et al., 2018) states that emphasis on environmental sustainability is crucial in the overall achievement of sustainable development goals especially in developing countries where the concept of sustainability is yet to be fully assimilated into their construction process. Further research in the field has indicated that there has been a bias towards research on the operational phases therefore neglecting other important phases from design to deconstruction that also need further emphasis to achieve a holistic approach towards sustainable construction. And Environmentally sustainable construction (ESC) this has led to the availability of gaps in a holistic approach to monitoring and evaluating sustainability.

There are several sustainability theories that have previously been developed in order to aid in understanding, implementation and evaluation of SC globally. These theories include, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate Sustainability (CS) , stakeholder theory, Institutional theory, Resilience theory, ecological modernization theory and green economics. CSR and CS are interchangeable theories which state the obligation of companies to implement sustainable practices even in instances where there are no legal requirements. However, according to (Otieno, 2012) there is still room for further improvement of the existing CSR model in the country to improve the practical legal and institutional frameworks to mandate all contractors to adopt these strategies. According to (Rami & Samuel, 2021), Stakeholder theory which argues that stakeholder cooperation follows a specific purpose, the complexity of sustainable construction often leads to reluctance in acceptance of sustainability proposals therefore they influence the uptake and evaluation of sustainability in their projects. All these theories collectively dissect compliance and complacency of the uptake and evaluation of effectiveness of sustainable construction practices locally and globally.

Holistic sustainable construction practices includes sustainability literacy, sustainable procurement practices, sustainability compliance and sustainability asessment frameworks. According to (Paul & Alison, 2007), Powerful policy drivers are needed to integrate sustainability into the curriculum to influence decision making for professional bodies that want to embrace sustainable construction program.

Sustainable procurement evaluates the value for money for sustainable construction and is key in improvement and monitoring of trends within the construction industry. In Kenya, sustainable procurement practices have recently been adopted by ensuring green inventory management, green specifications as well as green tendering processes by ensuring g that suppliers and contractors ensure that they incorporate sustainable or recycled products to ensure highest value for money. However, the acceptance of sustainable construction is still lagging due to other challenges faced in the construction industry which directly affect the procurement processes. (Eunice, et al., 2015).

2.1. Sustainability compliance Globally and in Kenya

The level of compliance to sustainability practices varies from one continent to another as well as within different countries in the same regions due to various reasons. Compliance and uptake of sustainable practices is generally high in countries in the European, American, and Asian continents in comparison to Africa. The driving factors influencing high levels of sustainability includes the existence of mandatory construction regulations, legislations, and drivers which positively influences the growth and adoption of green building. Despite the existence of initiatives promoting these practices, there are still some challenges facing total quality management and implementation of sustainable and green construction due to reluctance, partial compliance, and misunderstandings due to unfamiliarity with sustainable practices (Joshua, et al., 2022).

Most of the compliance tools used in the rating of sustainability: LEED, BREAM, EDGE and Greenstar rating systems were all developed in first world countries except for the Safari Green building index tool which was developed in Kenya with the aim of localizing the criteria for rating efficiency of sustainability in the projects within the country. These tools all have different rating standards specific to each. Notable differences in compliance to sustainable construction across different countries are subjective to the regulations and policy implementations in each country. Kenya has previously been relying on the use of three different rating systems therefore the creation of a local tool aims to increase the acceptance of accreditation of sustainability ratings with the aim of improving the percentage of awareness within the country. Compliance towards sustainable construction principles is spearheaded by government legislations and restrictions which has been significantly low but has indicated a significant growth over the last five years.

2.2. Sustainability assessment framework and sustainable project management

Globally, there are different sustainable building assessment methods with different strengths and weaknesses due to the influence of the scope of works, different requirements as well as different categorization of elements. Despite the availability of several assessment tools, there is a lack of proper standardization across all methods and tools. The absence of standardization makes it challenging to compare and benchmark sustaibable landscapes and buildings across multiple assessment methodologies because each one may utilize distinct criteria, categories, weighting systems, and documentation needs. Geographical variation in sustainable building assessments ensures that depending on elements like temperature, building codes, and cultural preferences, different assessment techniques may be more suited for certain geographical areas. A sustainable building assessment technique needs to consider regional variations when choosing an evaluation method or assessing the sustainability of their projects.

3. Methodology

An empirical study of both published and unpublished secondary data was undertaken to provide a concise picture of the extent of monitoring and evaluation of sustainable construction measures in Kenya and to ascertain the extent of knowledge on sustainable practices. This was informed by previous research conducted using a similar methodology approach in instances where there was lack of unbiased primary data and minimal data as currently is in the specified field of landscape architecture in Kenya. This is justified by the existence of studies such as research conducted by (Ashish, 2022), (Catherine & Jeniffer, n.d.) and (KUPEKA, 2013) among many other examples.

4. Findings

A comparative analysis of the extent of knowledge on sustainable practices was conducted, and findings were collected from sources such as the Architectural Association of Kenya, Kenya Green Building Society, and other journals published and tabulated to understand best how the results impact monitoring and evaluation of sustainability in construction projects as indicated in

Figure 1 below.

Further research on the level of incorporating Sustainable construction methods into the existing curriculum indicates a significant gap in ensuring that Landscape Architecture is introduced to the existing Universities in Kenya to create awareness of the benefits of Landscape Architecture. The findings are shown in

Table 1.

4.1. Sustainable /Green Rating Tools

Assessment and monitoring of sustainable construction practices in Kenya have been spearheaded by the Architectural Association of Kenya (AAK) in liaison with the Kenya Green Building Society (KGBS). Kenya has been using the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards and Environmental Design for Greater Efficiencies (EDGE), and the Green Star rating system in monitoring and documenting green buildings to achieve sustainability in the country. In 2019, AAK unveiled the Safari Green Building Index, developed over the past five years to streamline the rating system in Kenya. The tool allocates different percentages to the seven performance categories sectioned into prerequisite requirements (0%), building landscapes (5%), noise control and acoustics (5%), passive design strategies (45%), energy efficiency (10%), resource efficiency (30%) and innovation (5%). Like the other international rating tools, the green building rating collaborates with localized benchmarks and guidelines (Architectural Association of Kenya , 2022). It is important to note that these rating tools are heavily subjective toward buildings; therefore, landscape architecture projects are considered secondary to architecture and other engineering projects.

Further research indicates that a significant percentage of Kenyan developers are unaware of how these green building rating tools work; therefore, implementation of sustainable and green building uptake and monitoring is significantly low. The state department for public works, in liaison with the Kenya Building and Research Centre (KBRC), is mandated to conduct research and coordinate the government’s sustainable and green building agenda per the 2017/2018 to 2021/2022 strategic plan. KBRC’s key action areas include researching climate-resilient and sustainable building construction materials and technologies, developing green-building policies, regulations, and guidelines, and mainstreaming green building principles in design and construction (United Nations Development Program, 2019).

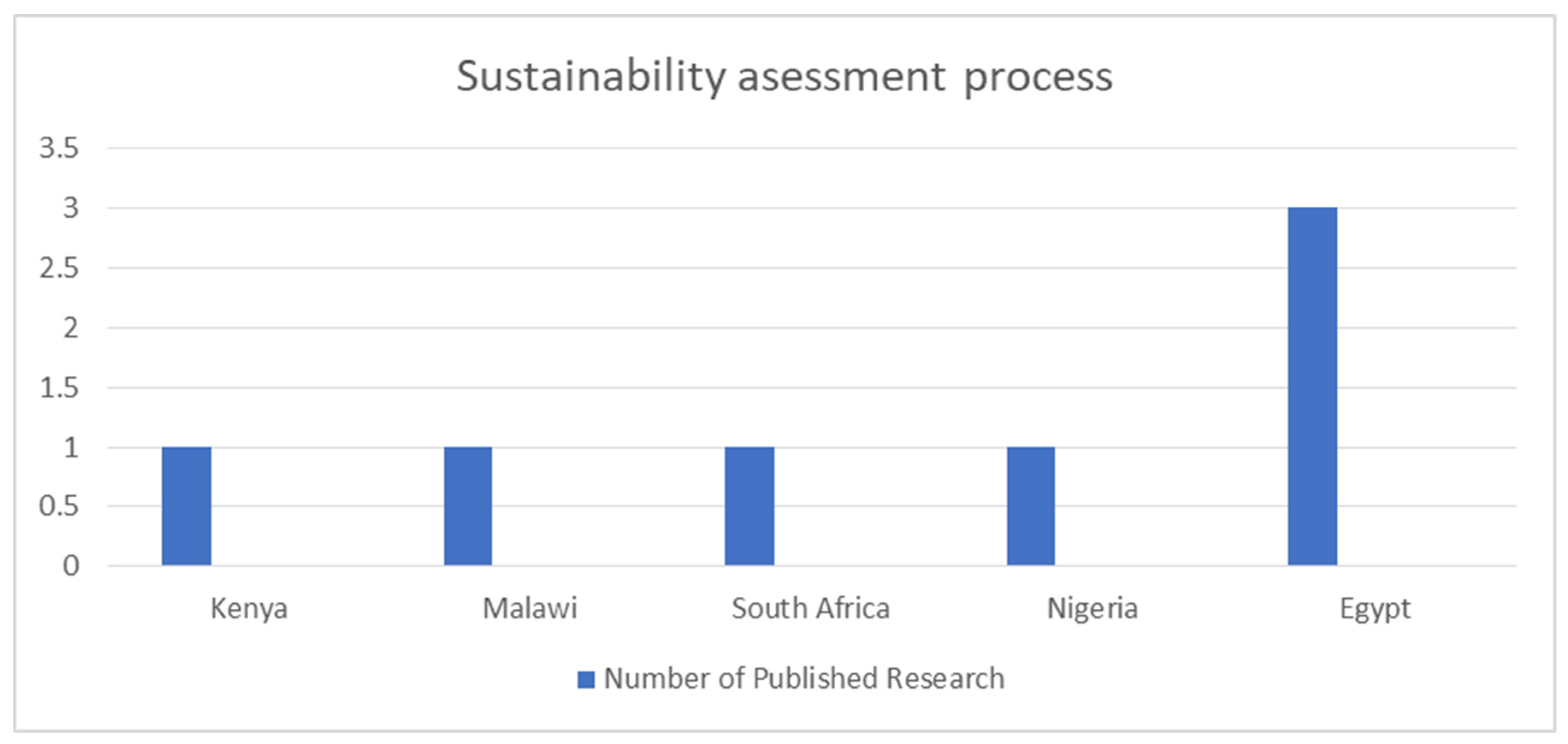

4.2. Sustainability Assessment Process

According to Etheldreder et al. (2023), Kenya has only one published Sustainability assessment process compared to other African Nations in the continent, as indicated below. A comparison between the five countries above showed that Egypt, Nigeria, and South Figure Africa are highly productive in creating Sustainability assessment processes for their local construction industries compared to Kenya and Malawi. Etheldreder et al. (2023) argue that these three countries have significantly higher economies than Kenya, causing a much higher environmental risk and, thus, the need for sustainability practices in their local industries. Kenya, being among the countries with a lower GDP than the above-stated countries, has a lower implementation of sustainable infrastructure projects and, thus, lower sustainability assessments. This phenomenon is indicative of the findings by other scholars that these countries have several of their higher education institutions ranked among the top five hundred universities worldwide according to the Times Higher Education (THE) compared to Kenyan institutions.

4.3. Sustainable Construction Materials

Data on sustainable or alternative construction materials in the country is significantly low, with less than 20% of data readily available. In contrast, approximately 47% of data was missing hindering the significance of assessment and monitoring of the sustainability of alternative construction materials in the country, according to findings from Gregor et al. (2017), illustrated in

Table 2.

However, the KNBS and the construction cost handbook published by the Institute of Quantity Surveyors of Kenya (IQSK) did not cover further research on the cost of these alternative construction materials. It is, therefore, challenging to facilitate total cost assessment of sustainable construction since the cost of alternative materials will vary from one contractor to the next.

Currently, the country uses other international European EPD databases since there is a lack of data on locally specific embodied energy for any of the materials surveyed, thus lacking a local life-cycle inventory database. This creates a significant barrier in substantiating the sustainability of almost all alternative materials in Kenya (Gregor, et al., 2017).

The State Department for Housing and Urban Development is mandated to facilitate the use of Appropriate Building materials and Technology (ABMT). However, the department faces challenges in assessing said policy due to varying appropriateness relative to geographical and project scope (State Department for Housing and Urban Development, 2017). Findings indicate that challenges faced in the uptake and monitoring of ABMT arise from the slow adoption by professionals, a prevailing research gap, the lack of harmonized regulatory framework, and low capacity to drive ABMT in the fabrication, maintenance, and equipment servicing.

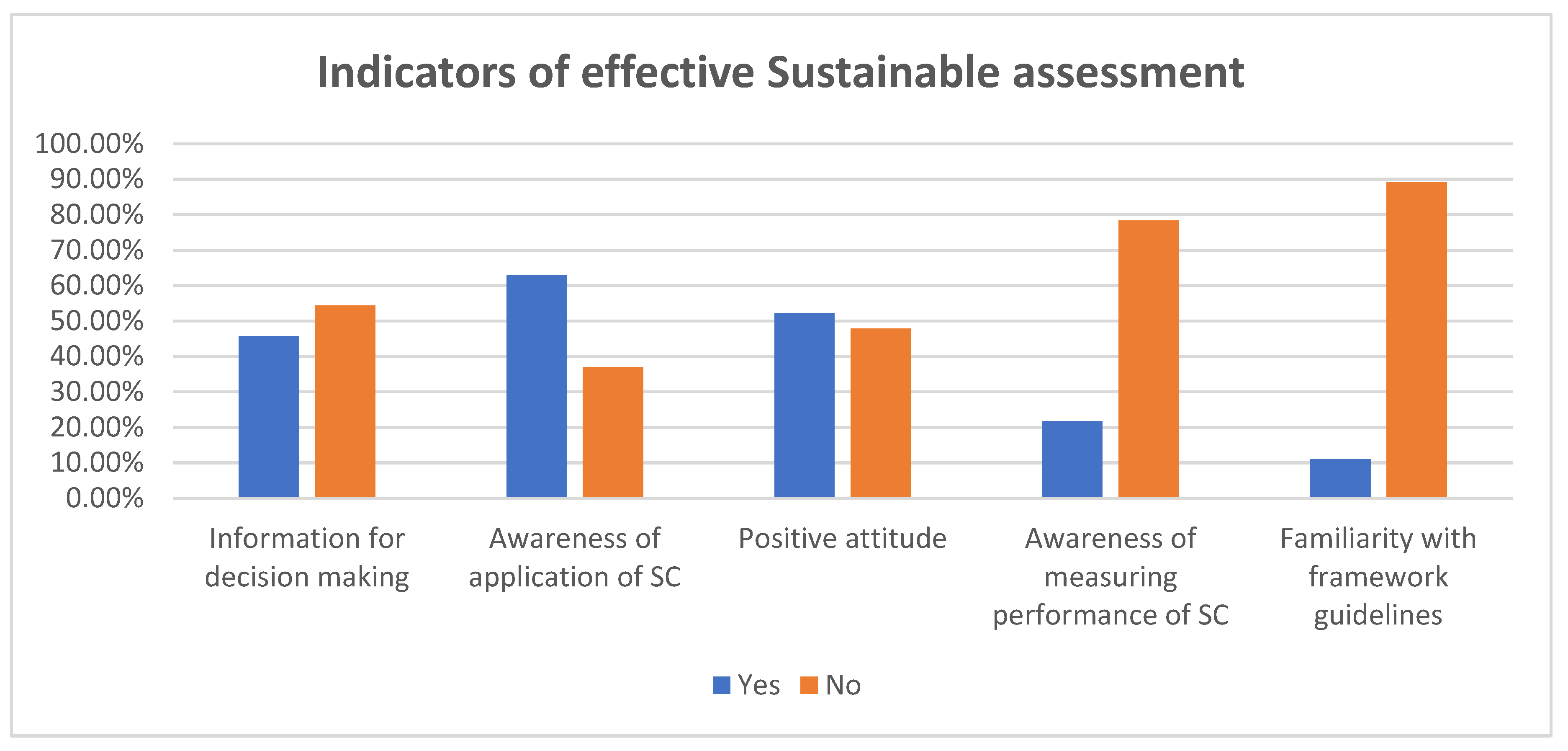

Findings from construction assessment research data on the level of monitoring of the efficiency of sustainable practices, such as energy consumption and water consumption, indicate that sustainable construction assessment standards and tools existent in Kenya are below average (Samuel, 2019). Currently, observations suggest that sustainability assessment is not deemed a necessary project requirement; therefore, there is a lack of sufficient information for decision-making in the monitoring and decision-making for assessments of sustainable projects (Samuel, 2019).

Figure 3.

Indicators of effective sustainable assessment. Source: (Samuel, 2019).

Figure 3.

Indicators of effective sustainable assessment. Source: (Samuel, 2019).

4.4. Monitoring of Cost of Sustainable Landscape Materials

Data from the construction cost handbook of Kenya published by the Institute of Quantity Surveyors of Kenya (IQSK) in liaison with the state department for public works indicated a lack of a comprehensive cost analysis for landscape construction materials directly affecting the efficient implementation of high-quality landscape projects. Published cost estimates in Kenyan shillings from the year 2018 to 2022 in Nairobi were analyzed, and an average was calculated for each category as indicated in the table below:

Findings indicate a significant gap in the monitoring of Landscape Construction cost for the period stated since it depicts a reduction of the expenses for some aspects from one year to another, contrary to the evidence of increased construction cost indices in the country. The handbook does not cater to all aspects of sustainable practices, such as monitoring water consumption in landscape projects from irrigations and the cost of permeable paving materials with lower embodied carbon. Some findings indicate that sustainable construction materials like paving blocks are slightly cheaper at Ksh. 850 per square meter compared to traditional concrete pavers retailing at Ksh. 950 per square meter; however, these cost rates of new alternative materials are not published in the handbook. The summary in all the construction cost handbooks published does not give a composite building cost per square meter for Landscape works therefore leaving room for a higher margin of error during costing for Landscape works.

Findings from the Jenga green tool, a directory of green building materials and their respective costs, are significant in the overall projections and comparison of costs between predominant construction materials and sustainable materials. However, the library does not have a vast array of construction materials since it is a relatively new library; therefore, there is a significant gap in documentation and evaluation of available sustainable materials and their respective costs across all the construction disciplines and, more specifically the variations of the cost of Sustainable landscape Architecture materials.

5. Results

Globally, there are different sustainable assessment methods with different strengths and weaknesses due to the influence of the scope of work, different requirements, and different categorization of elements. Despite the availability of several assessment tools in Kenya, there is a lack of proper standardization across all methods and tools. Monitoring and evaluating in the country indicated a significant gap in procedural monitoring of sustainability practices from the inception of projects to the completion and operationalization of Landscape projects similar to the Architectural and Engineering projects. It was noted that only four tools are used in the country. Still, there is a significant gap in the evaluation, monitoring, and assessments of sustainability practices during and after the commissioning of construction projects.

According to (Paul & Alison, 2007), Powerful policy drivers are needed to integrate sustainability into the curriculum to influence decision-making for professional bodies that want to embrace sustainable construction programs to foster the improvement of personal responsibility towards achieving sustainable construction practices through monitoring and evaluation. Studies indicated that 83 buildings in the country have been cumulatively certified as green buildings from 25 in the year 2021. In contrast, there are no certified sustainable Landscapes or civil engineering projects despite the high number of construction projects ongoing. This number indicated a slow increase in monitoring efforts and policy development that suit landscape and civil engineering projects.

The development of the Safari Green building tool, localized to suit the assessment of projects implemented within the country and the East African market, has been instrumental in ensuring that parameters are monitored within the context of the geographical location of the existing projects. Despite the unveiling of this tool, the main challenge faced in its use is the lack of a specific website or repository dedicated to the tool. The tool has only been in use for less than five years; it is subject to more improvements in performance criteria for different elements. Therefore, there is room to incorporate a rating criterion specific to Landscape Architecture projects. The use of different international rating tools infers different rating standards, affecting the classification of rated buildings and constructions subject to the tool used. For instance, LEED certification is classified into four levels: Platinum (80+ points), Gold (60-79 points), Silver (50-59 points), and Certified (40-49 points).

On the other hand, the Greenstar rating system uses four to six stars to evaluate the construction’s efficiency, with different stars allocated for different categories assessed, such as communities, design and build interiors and fit-outs, and performance categories. The Safari green index rates sustainability by use of percentages allocated to the different performance categories expounded into prerequisite requirements (0%), Building landscapes (5%), passive design strategies (45%), energy efficiency (10%), Resource efficiency (30%), Noise control (5%) and innovation (5%). These three rating systems have allocated different weights to different aspects of sustainable practices; therefore, there is a likelihood that these rating systems may have some differences when used to rate the same project. The challenge, therefore, is to ensure that the development of the safari green building tool is continuous to improve on any possible gaps to best suit its application in monitoring sustainability.

Institutions such as KBRC have the mandate to research sustainability but significantly face challenges in collecting data for alternative construction materials, impeding the accuracy level in analyzing the effectiveness of sustainable construction. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) should also incorporate statistics on Landscape Construction and sustainable construction materials and costs to inform further research and certification of the same by the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), whose mandate is to test and certify the standards for use in construction. Findings indicate that only one published Environmental product declaration (EPD) is conducted by the country compared to other countries such as Egypt. It is paramount that there should be a deliberate effort in the research and publishing of more EPDs to inform future assessments of the impact of construction materials on the environment, facilitating more data on the feasibility of sustainable construction.

Life cycle analysis is lacking for construction projects in Kenya. The National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) is mandated to conduct environmental audits in the country. However, frequent audits are not undertaken on existing landscapes after the operationalization of Landscape and civil construction projects. This consequently translates to a lack of post-occupancy assessments of landscape projects and the lack of monitoring of possible unsustainable materials. The lack of an existing policy on life cycle assessment for Kenyan projects has left room for private assessments of the efficiency of projects using different variables, thus leaving room for unstandardized reports. This implies that there is room for growth in a holistic approach toward monitoring and evaluating the post-occupancy efficiency of projects in the future.

6. Conclusions

The level of technical know-how and knowledge on sustainable construction practices in construction and Landscape Architecture is average at slightly higher than 50%. Less than 5% of construction practitioners incorporate Landscape Architects in their projects from inception, leaving room for a lack of sustainability in outdoor spaces. There is a significant lack of existing academic structures in place for teaching sustainability in higher institutions of Learning in Kenya, especially in Landscape Architecture and green building academia, therefore impeding the practice of monitoring and life cycle assessment of ongoing and completed Landscape Architecture projects.

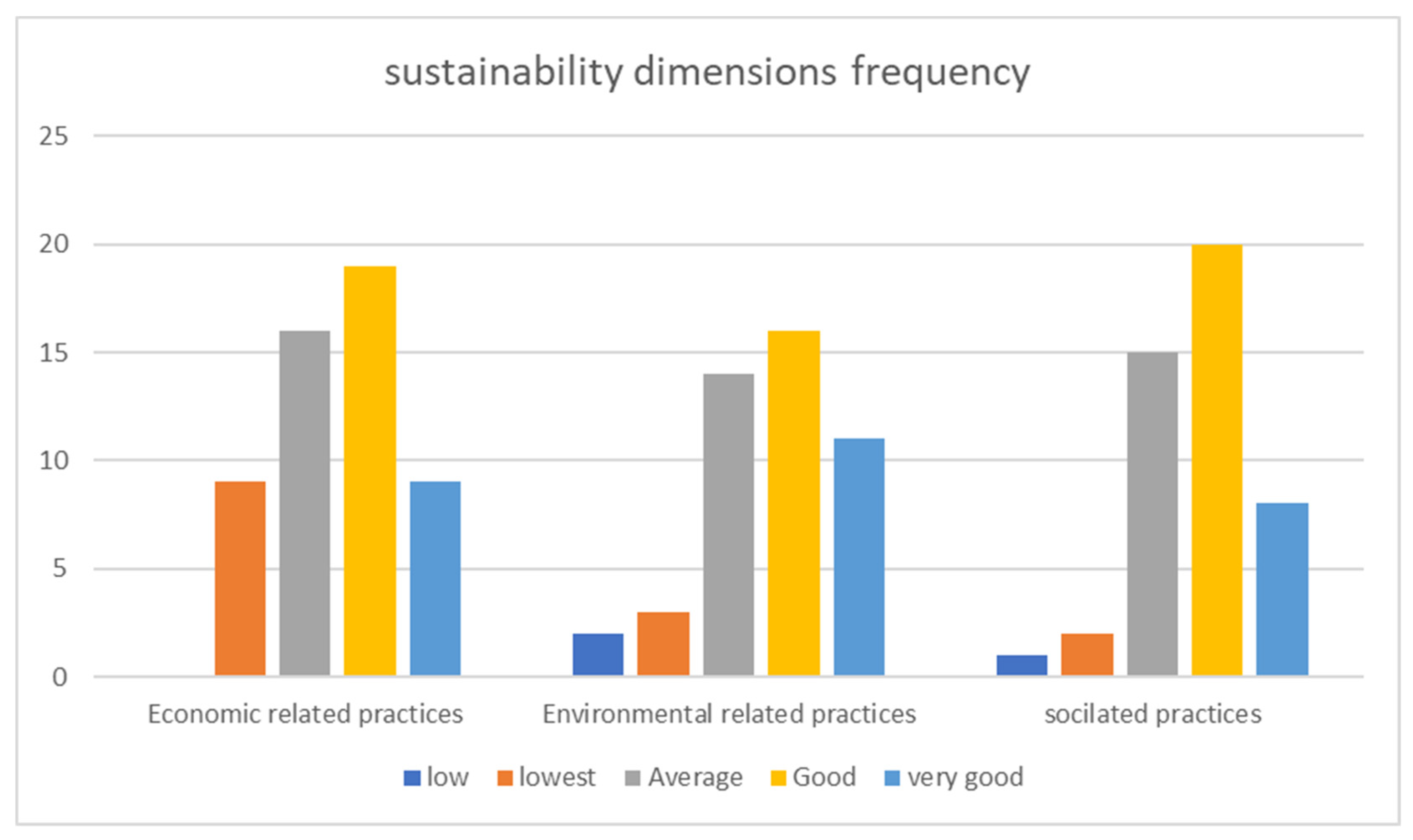

Sustainable construction in Landscape Architecture should heavily focus on environmental sustainability. However, findings indicate that the Kenyan market generally focuses more on social and economic aspects than environmental aspects. Therefore, Sustainability assessment frameworks should be further developed and broken down into suitable categories and scales to include clients, developers, designers, and the public. Public education on the benefits of sustainability monitoring will increase awareness, thus enabling the emphasis on implementing sustainability assessments, leading to a high acceptance of sustainable construction practices.

Notably, 99.8% of construction projects and buildings in Kenya have not been certified to be sustainable in the country despite the availability of sustainability rating tools. There is a general reluctance to assess the sustainability performance of constructions due to a lack of familiarity with assessment standards and the cost of incorporating frequent assessment drills throughout the project life cycle. In Kenya, there have been several independent Landscape Architecture projects which have been implemented. Still, the green rating tools have accredited none compared to other countries where Landscape projects have been certified under the SITES accredited professionals (AP) credentials through green building certifications. It is crucial to create a long-term monitoring system of ecosystems that will form the basis for assessing the growth and impact of sustainable construction practices, especially in Landscape Architecture projects in Kenya.

Several government bodies are mandated to oversee research of sustainable materials, cost of alternative materials, creation of policies for implementation and assessments, as well as education on the benefits of sustainable practices. However, these government bodies have not been entirely successful in performing their duties, therefore hindering further development in sustainable construction, especially in emerging practices such as Landscape Architecture. This leaves room for poor attitude towards monitoring and assessment strategies for sustainability in Landscape Architecture. It is, therefore essential to streamline the mandate of these governing bodies to ensure their ability to monitor and assess sustainable construction trends and practices in Kenya.

Funding

This study has not received any funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Architectural Association of Kenya, 2022. The ststus of the built environment Report, Nairobi: Architectural Association of Kenya.

- Ashish, G. , 2022. Using secondary data in research on social sustainability in construction project management: a transition from “interview society” to “project-as-practice”. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 3 May.

- C. K. & J. M., n.d. Sustainable Real Estate Development in Kenya: an Empirical Investigation. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

- Etheldreder, T.K. , Innocent, M. & Sambo, L. Z., 2023. A Systematic Literature Review on Local Sustainability Assessment Processes for Infrastructure Development Projects in Africa. MDPI.

- Eunice, K. M. , Edward, W. & Peter,. K. M., 2015. Application and Practice of Sustainable Procurement in Kenya. International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, 2(12), pp. 289-299.

- Gregor, H. , Robert, S. & Maximilian, B., 2017. Low Cost, low Carbon, but no data: Kenya's struggle to Develop the availability of performance data for Building Products. s.l., Elsevier B.V.

- Joshua, A. , De-Graft, J. O., Prince,. A.-A.. & Rita, Y.. M. L., 2022. Sustainable building processes’ challenges and strategies: The relative important index approach. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, Volume 7, pp. 1-9.

- KUPEKA, C. M. A. , 2013. FACTORS INFLUENCING SUSTAINABILITY OF HOUSING PROJECTS IN KENYA: A CASE OF KCB SIMBA VILLAS ESTATE EMBAKASI PROJECT, NAIROBI COUNTY. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

- Margaret, K. W. , 2016. ORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY PRACTICES AND PERFORMANCE OF FIRMS LISTED AT NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE, KENYA. Nairobi: Kenyatta University.

- Otieno, O. S. , 2012. An investigation into the practice corporate social responsibility in the construction industry in Kenya: a case of contractors, Nairobi. Nairobi: University of Nairobi.

- Paul, M. & Alison, J. C., 2007. Sustainability literacy: The future paradigm for construction education. Structural Survey.

- Rami, B. Y. & Samuel, M., 2021. Sustainable Value Creation for Stakeholders During a Projects Life Cycle. Stockholm: KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY.

- Rui-Dong, C. et al., 2017. Evolving theories of sustainability and firms: History, future directions and implications for renewable energy research. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 72, pp. 48-56. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, K. J. , 2019. An Investigation on sustainability compliance in the Kenyan construction Industry (A perspective of Interior design Professionals in Nairobi city county). Nairobi: Nairobi University.

- Sarfo, M. , Joshua, A. & Gabriel, N., 2018. A theoretical framework for conceptualizing contractors’ adaptation to environmentally sustainable construction. International Journal of Construction Management, 20(7), pp. 801-811. [CrossRef]

- State Department for Housing and Urban Development, 2017. Appropriate Building Materials And Technology (Abmt). [Online] Available at: https://housingandurban.go.ke/appropriate-building-materials-and-technology-abmt/ [Accessed 8 April 2023]. 8 April.

- Thomas, W. C. & Anne, M. V., 2011. Sustainable Landscape Management. Design, Construction and Management. s.l.:John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- United Nations Development Program, 2019. United Nations Development Program. [Online] Available at: https://www.undp.org/kenya/publications/greenmark-standard-green-buildings [Accessed 6 April 2023].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).