Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Antimicrobial peptides

2.1. Cathelicidins

2.1.1. Humans

2.1.2. Snake

2.1.3. Alligator

2.1.4. Wallaby

2.1.5. Hoofed animals

2.2. Defensins

2.2.1. Human α-Defensins

2.2.2. β-Defensins

2.2.3. Insect defensins

2.3. Frog AMP

2.3.1. Magainin and pexiganan

2.3.2. Brevinin-2 related peptide

2.3.3. Alyteserins

2.3.4. Peptide glycine-leucine-amide

2.3.5. Caerulein precursor fragment

2.3.6. Hymenochirins

2.3.7. XT-7

2.3.8. Buforins

2.3.9. Caerin 1.1 and 1.9

2.3.10. Hyalin a1

2.4. Fish piscins

2.5. Hepcidin

2.6. Melittin

2.7. Cecropins

2.8. Mastoparan

2.9. Histatins

2.10. Dermcidin

2.11. Tachyplesin III

2.12. Spider peptides

2.13. Scorpion

2.14. Lynronne-1

2.15. Hybrid peptides

3. Resistance to AMPS

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistance infections globally: Final report and recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. London, UK: Government of the United Kingdom; 2016, 84 p.

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new. antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. Persister cells, dormancy, and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A.; Gollan, B.; Helaine, S. Persistent bacterial infections and persister cells. Nat Rev Microbiol 2017 15, 453–464. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Breidenstein, E.B.M.; Hancock, R.E.W. Importance of adaptive and stepwise changes in the rise and spread of antimicrobial resistance. In: Keen, P.; Monforts, M. editors. Antimicrobial resistance in the environment. Hoboken, New Jersey, EUA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 43-71. ISBN: 978-1-118-15623-0.

- Olivares, J.; Bernardini, A.; Garcia-Leon, G.; Corona, F.; Sanchez, M.B.; Martinez, J.L. The intrinsic resistome of bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol 2013, 30, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.; Shan, Y. Persister awakening. Mol Cell 2016, 63, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, B.P.; Rowe, S.E.; Gandt, A.B.; Nuxoll, A.S.; Donegan, N.P.; Zalis, E.A.; et al. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Brown Gandt, A.; Rowe, S.E.; Deisinger, J.P.; Conlon, B.P.; Lewis, K. ATP-dependent persister formation in Escherichia coli. mBio 2017, 8, 02267–e02216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana, M.; Sereti, C.; Ioannidis, A.; Mitchell, C.A.; Ball, A.R.; Magiorkinis, E. Chatzipanagiotou, S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Hadjifrangiskou, M.; Tegos, G.P.; et al. Options and limitations in clinical investigation of bacterial biofilms. Clin Microbiol Ver 2018, 31, 00084–e00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.R.; Shan, Y.; Zalis, E.A.; Isabella, V.; Lewis, K. A genetic determinant of persister cell formation in bacterial pathogens. J Bacteriol 2018, 200, e00303–e00318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global, multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.H.; Moore, L.S.P.; Sundsfjord, A.; Steinbakk, M.; Regmi, S.; Karkey, A.; Guerin, P.J.; Piddock, L.J. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2016, 387, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan drug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice LB. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE J Infect Dis 2008, 197, 1079-1081. [CrossRef]

- Friedman ND, Temkin E, Carmeli Y. The negative impact of antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016, 22, 416. [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Zhang, X.D.; Zhao, Q.; Peng, B.; Zheng, J. Analysis of global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii infections disclosed a faster increase in OECD countries. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, E.C.; Chenia, H.Y.; El Zowalaty, M.E. Acinetobacter baumannii biofilms: effects of physicochemical factors, virulence, antibiotic resistance determinants, gene regulation, and future antimicrobial treatments. Infect Drug Resist 2018, 11, 2277–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Biswas, I.; Veeraraghavan, B. Accurate identification of clinically important Acinetobacter spp.: An update. Future Sci OA 2019, 5, FSO395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgaya, C.; Mari-Almirall, M.; van Assche, A.; Fernandez-Orth, D.; Mosqueda, N.; Telli, M.; Huys, G.; Higgins, P.G.; Seifert, H.; Lievens, B.; et al. Acinetobacter dijkshoorniae sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex mainly recovered from clinical samples in different countries. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016, 66, 4105–4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, A.; Krizova, L.; Maixnerova, M.; Sedo, O.; Brisse, S.; Higgins, P.G. Acinetobacter seifertii sp. nov., a member of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter baumannii complex isolated from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2015, 63, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Lee, Y.T.; Kuo, S.C.; Yang, S.P.; Fung, C.P.; Lee, S.D. Rapid identification of Acinetobacter baumannii, Acinetobacter nosocomialis, and Acinetobacter pittii with a multiplex PCR assay. J Med Microbiol 2014, 63, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí-Almirall, M.; Cosgaya, C.; Higgins, P.G.; Van Assche, A.; Telli, M.; Huys, G.; Lievens, B.; Seifert, H.; Dijkshoorn, L.; Roca, I.; et al. MALDI-TOF/MS identification of species from the Acinetobacter baumannii (ab) group revisited: Inclusion of the novel A. seifertii and A. dijkshoorniae species. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017, 23, 210.e1–210.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkshoorn, L.; Nemec, A.; Seifert, H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007, 5, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnacho-Montero, J.; Timsit, J.F. Managing Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2019, 32, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, A.Y.; Seifert, H.; Paterson, D.L. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008, 21, 538–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willyard, C. The drug-resistant bacteria that pose the greatest health threats. Nature 2017, 543, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, V.C.J.; Rodrigues, B.Á.; Bonatto, G.D.; Gallo, S.W.; Pagnussatti, V.E.; Ferreira, C.A.S.; de Oliveira, S.D. Heterogeneous persister cells formation in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukovic, B.; Gajic, I.; Dimkic, I.; Kekic, D.; Zornic, S.; Pozder, T.; Radisavljevic, S.; Opavski, N.; Kojic, M.; Ranin, L. The first nationwide multicenter study of Acinetobacter baumannii recovered in Serbia: Emergence of OXA-72, OXA-23 and NDM-1-producing isolates. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isler, B.; Doi, Y.; Bonomo, R.A.; Paterson, D.L. New treatment options against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e01110–e01118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. Available at: https://www.who. int/medicines/publications/WHO-PPL-Short_Summary_25Feb-ET_NM_WHO.pdf. [Accessed in June 2023].

- Domalaon R, Zhanel GG, Schweizer F. Short antimicrobial peptides and peptide scaffolds as promising antibacterial agents. Curr Top Med Chem 2016, 16, 1217-1230. [CrossRef]

- Vrancianu, C.O.; Gheorghe, I.; Czobor, I.B.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Antibiotic resistance profiles, molecular mechanisms and innovative treatment strategies of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Sun, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, J.; Lao, X.; Zheng, H.; Xu, H. DRAMP: A comprehensive data repository of antimicrobial peptides. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 24482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

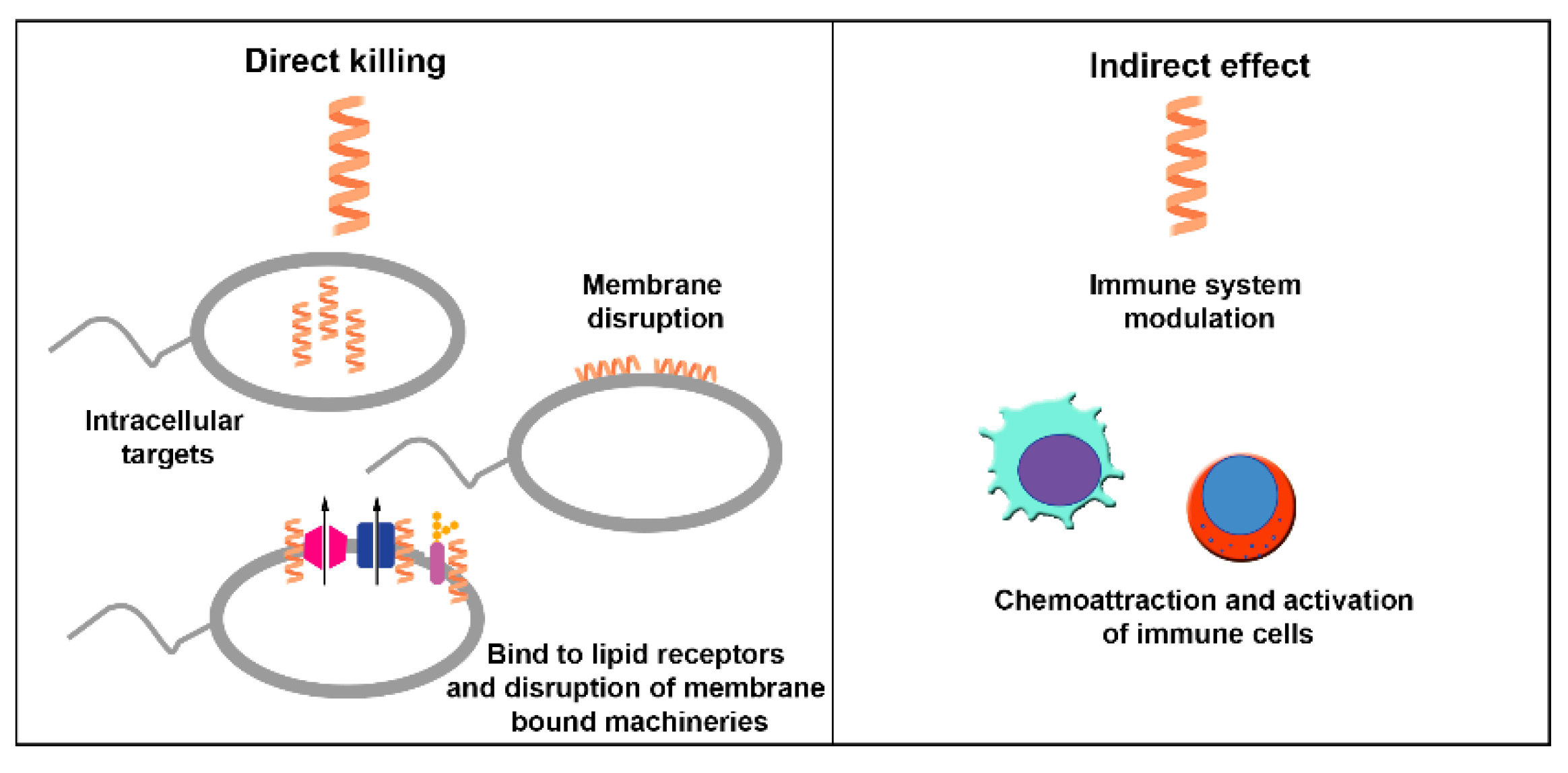

- Kumar, P.; Kizhakkedathu, J.N.; Straus, S.K. Antimicrobial peptides: diversity, mechanism of action and strategies to improve the activity and biocompatibility in vivo. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.J.; Gallo, R.L. Antimicrobial peptides. Curr Biol. 2016, 26, R14–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Sunkara, L.T. Avian antimicrobial host defense peptides: From biology to therapeutic applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2014, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.; Ortiz, C.; Guzman, F.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Torres, R. Antimicrobial peptides: Promising compounds against pathogenic microorganisms. Curr Med Chem 2014, 21, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, T.; Dawood, A.; Esterhuyse, A.J.; Katerere, D.R. Antimicrobial properties of the skin secretions of frogs. S Afr J Sci 2012, 108, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfalzgraff, A.; Brandenburg, K.; Weindl, G. Antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential for bacterial skin infections and wounds. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

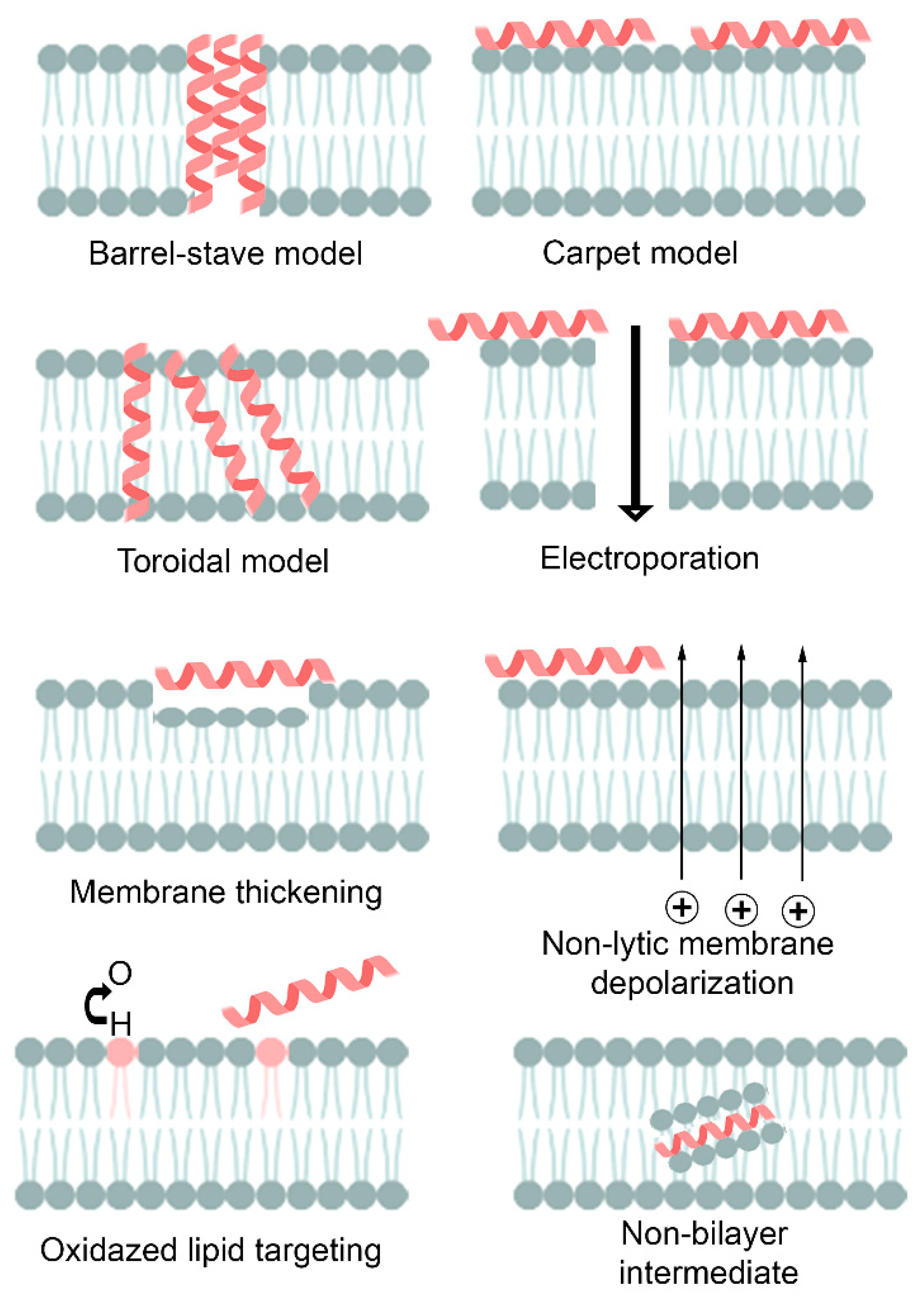

- Epand, R.M.; Walker, C.; Epand, R.F.; Magarvey, N.A. Molecular mechanisms of membrane targeting antibiotics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016, 1858, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson DI, Hughes D, Kubicek-Sutherland JZ. Mechanisms and consequences of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Drug Resist Updat 2016, 26, 43-57. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenstein, G.; Lecar, H. Electrically gated ionic channels in lipid bilayers. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 1977, 10, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogden, K.A. Antimicrobial peptides: Pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005, 3, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breukink, E.; de Kruijff, B. The lantibiotic nisin, a special case or not? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999, 1462, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimley, W.C. Describing the mechanism of antimicrobial peptide action with the interfacial activity model. ACS Chem Biol 2010, 5, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, D.; Shai, Y. Interaction of fluorescently labeled pardaxin and its analogs with lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem 1991, 266, 23769–23775, PMID: 1748653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, Y.; Bach, D.; Yanovsky, A. Channel formation properties of synthetic pardaxin and analogs. J Biol Chem. 1990, 265, 20202–20209, PMID: 1700783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, N.; Matsuzaki, K. Polar angle as a determinant of amphipathic α-helix-lipid interactions: A model peptide study. Biophys J. 2000, 79, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T-H.; Hall, K.N.; Aguilar, M-I. Antimicrobial peptide structure and mechanism of action: A focus on the role of membrane structure. Curr TopMed Chem. 2016, 16, 25-39. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.T.J.; Hale, J.D.; Elliot, M.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Straus, S.K. Effect of membrane composition on antimicrobial peptides aurein 2.2 and 2.3 from Australian southern bell frogs. Biophys J 2009, 96, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparr, E.; Ash, W.L.; Nazarov, P.V.; Rijkers, D.T.S.; Hemminga, M.A.; Tieleman, D.P.; et al. Self-association of transmembrane-helices in model membranes. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 39324–39331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.T.J.; Hale, J.D.; Elliott, M.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Straus, S.K. The importance of bacterial membrane composition in the structure and function of aurein 2.2 and selected variants. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembranes 2011, 1808, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeaman, M.R.; Yount, N.Y. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev 2003, 55, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, Y. Mode of action of membrane-active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002, 66, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.I.; Le Brun, A.P.; Whitwell, T.C.; Sani, M.-A.; James, M.; Separovic, F. The antimicrobial peptide aurein 1.2 disrupts model membranes via the carpet mechanism. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2012, 14, 15739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaram, N.; Nagaraj, R. Interaction of antimicrobial peptides with biological and model membranes: Structural and charge requirements for activity. Biochimt Biophys Acta 1999, 1462, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozek, A.; Friedrich, C.L.; Hancock, R.E. Structure of the bovine antimicrobial peptide indolicidin bound to dodecyl phosphocholine and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15765–15774, PMID: 11123901. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, M.L.; Burton, M.; Grevis-James, A.; Hossain, M.A.; McArthur, S.; Palombo, E.A.; Wade, J.D.; Clayton, A.H. Imaging the action of antimicrobial peptides on living bacterial cells. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Rangarajan, N.; Weisshaar, J.C. Lights, camera, action! Antimicrobial peptide mechanisms imaging in space and time. Trends Microbiol 2016, 24, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Zare, H.; Akbari Eidgahi, M.R.; Chichaklu, A.H.; Movaqar, A.; Ghazvini, K. Review of antimicrobial peptides with anti-helicobacter pylori activity. Helicobacter 2019, 24, e12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Sambanthamoorthy, K.; Palys, T.; Paranavitana, C. The human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 and its fragments possess both antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Peptides 2013, 49, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Breij, A.; Riool, M.; Cordfunke, R.A.; Malanovic, N.; De Boer, L.; Koning, R.I.; et al. The antimicrobial peptide SAAP-148 combats drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms. Sci Transl Med. 2018, 10, eaan4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajbakhsh, M.; Akhavan, M.M.; Fallah, F.; Karimi, A. A recombinant snake cathelicidin derivative peptide: Antibiofilm properties and expression in Escherichia coli. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, R. The antimicrobial peptide ZY4 combats multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 26516–26522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barksdale, S.M.; Hrifko, E.J.; van Hoek, M.L. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide from Alligator mississippiensis has antibacterial activity against multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumanii and Klebsiella pneumonia. Dev Comp Immunol 2017, 70, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Lan, X.Q.; Du, Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, F.; et al. King cobra peptide OH-CATH30 as a potential candidate drug through clinic drug-resistant isolates. Zool Res 2018, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiau-Jing, Jung.; You-Di, Liao.; ;Chih-Chieh, Hsu.; Ting-Yu, Huang.; Yu-Chung, C.; Jeng-Wei, C.; Yu-Min, K.; Jean-San, C. Identification of potential therapeutic antimicrobial peptides against Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse model of pneumonia. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7318. [CrossRef]

- Dekan, Z.; Headey, S.J.; Scanlon, M.; Baldo, B.A.; Lee, T.-H.; Aguilar, M.-I.; Deuis, J.R.; Vetter, I.; Elliott, A.G.; Amado, M.; et al. ∆-Myrtoxin-Mp1a is a helical heterodimer from the venom of the jack jumper ant that has antimicrobial, membrane-disrupting, and nociceptive activities. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2017, 56, 8495–8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Asmari AK, Alamri MA, Almasoudi AS, Abbasmanthiri R, Mahfoud M. Evaluation of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of selected Saudi scorpion venoms tested against multidrug-resistant micro-organisms. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2017,10, 14-18. [CrossRef]

- Domhan, C.; Uhl, P.; Kleist, C.; Zimmermann, S.; Umstätter, F.; Leotta, K.; Mier, W.; Wink, M. Replacement of L-amino acids by d-amino acids in the antimicrobial peptide ranalexin and its consequences for antimicrobial activity and biodistribution. Molecules 2019, 24, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, R.; Wiesner, J.; Marker, A.; Pfeifer, Y.; Bauer, A.; Hammann, P.E.; Vilcinskas, A. Profiling antimicrobial peptides from the medical maggot Lucilia sericata as potential antibiotics for MDR gram-negative bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019, 74, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamova, O.V.; Orlov, D.S.; Zharkova, M.S.; Balandin, S.V.; Yamschikova, E.V.; Knappe, D.; Hoffmann, R.; Kokryakov, V.N.; Ovchinnikova, T.V. Minibactenecins ChBac7.Nα and ChBac7. Nβ—Antimicrobial peptides from leukocytes of the goat Capra hircus. Acta Naturae 2016, 8, 136-146. PMID: 27795854. [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wong, E.S.W.; Whitley, J.C.; Li, J.; Stringer, J.M.; Short, K.R.; Renfree, M.B.; Belov, K.; Cocks, B.G. Ancient antimicrobial peptides kill antibiotic-resistant pathogens: Australian mammals provide new options. PloS One 2011, 6, e24030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.J.; Pitts, R.E.; Pearson, R.A.; King, L.B. The effects of antimicrobial peptides WAM-1 and LL-37 on multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Patho Dis 2018, 76, fty007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Farres, X.; De La Maria, C.G.; López-Rojas, R.; Pachón, J.; Giralt, E.; Vila, J. In vitro activity of several antimicrobial peptides against colistin-susceptible and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infec 2012, 18, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, D.; Skerlavaj, B.; Bolognesi, M.; Gennaro, R. Structure and bactericidal activity of an antibiotic dodecapeptide purified from bovine neutrophils. J Biol Chem 1988, 263, 9573–9575, PMID: 3290210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falla, T.J.; Karunaratne, D.N.; Hancock, R.E. Mode of action of the antimicrobial peptide indolicidin. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 19298–19303, PMID: 8702613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hancock, R.E. Interaction of the cyclic antimicrobial cationic peptide bactenecin with the outer and cytoplasmic membrane. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 29–35, PMID: 9867806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, G.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, X.; Zeng, H.; et al. A simplified derivative of human defensin 5 with potent and efficient activity against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, e01504–e01517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, A.; Gupta, K.; Van Hoek, M.L. Characterization of Cimex lectularius (bedbug) defensin peptide and its antimicrobial activity against human skin microflora. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 470, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routsias, J.G.; Karagounis, P.; Parvulesku, G.; Legakis, N.J.; Tsakris, A. In vitro bactericidal activity of human β-defensin 2 against nosocomial strains. Peptides 2010, 31, 1654–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisetta, G.; Batoni, G.; Esin, S.; Florio, W.; Bottai, D.; Favilli, F.; Campa, M. In vitro bactericidal activity of human beta-defensin 3 against multidrug-resistant nosocomial strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006, 50, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacometti, A.; Cirioni, O.; Del Prete, M.S.; Barchiesi, F.; Paggi, A.M.; Petrelli, E.; Scalise, G. Comparative activities of polycationic peptides and clinically used antimicrobial agents against multidrug-resistant nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000, 46, 807–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Kang, N.; Ko, S.J.; Park, J.; Park, E.; Shin, D.W.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, S.H.; et al. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity and mode of action of Magainin 2 against drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, M. Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: isolation, characterization of two active forms, and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987, 84, 5449–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamm, R.K.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Simpson, K.M.; Farrell, D.J.; Sader, H.S.; Jones, R.N. In vitro spectrum of pexiganan activity when tested against pathogens from diabetic foot infections and with selected resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 1751–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; MacDonald, D.L.; Holroyd, K.J.; Thornsberry, C.; Wexler, H.; Zasloff, M. In vitro antibacterial properties of pexiganan, an analog of magainin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999, 43, 782–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaśkiewicz, M.; Neubauer, D.; Kazor, K.; Bartoszewska, S.; Kamysz, W. Antimicrobial activity of selected antimicrobial peptides against planktonic culture and biofilm of Acinetobacter baumannii. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2019, 11, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Ahmed, E.; Condamine, E. Antimicrobial properties of brevinin-2-related peptide and its analogs: Efficacy against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009, 74, 488–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, J.M.; Sonnevend, A.; Pál, T.; Vila-Farrés, X. Efficacy of six frog skin-derived antimicrobial peptides against colistin-resistant strains of the Acinetobacter baumannii group. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012, 39, 317–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.B.; Shan, B.; Bai, H.M.; Tang, J.; Yan, L.Z.; Ma, Y.B. Hydrophilic/hydrophobic characters of antimicrobial peptides derived from animals and their effects on multidrug resistant clinical isolates. Dongwuxue Yanjiu. 2015, 36, 41–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghaferi, N.; Kolodziejek, J.; Nowotny, N.; Coquet, L.; Jouenne, T.; Leprince, J.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Conlon, J.M. Antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the South-East Asian frog Hylarana erythraea (Ranidae). Peptides 2010, 31, 548–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Ahmed, E.; Pal, T.; Sonnevend, A. Potent and rapid bactericidal action of alyteserin-1c and its [E4K] analog against multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Peptides 2010, 31, 1806–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Mechkarska, M.; Arafat, K.; Attoub, S.; Sonnevend, A. Analogues of the frog skin peptide alyteserin-2a with enhanced antimicrobial activities against Gram-negative bacteria. J Pept Sci 2012, 18, 270–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean DT, McCrudden MT, Linden GJ, Irwin CR, Conlon JM, Lundy FT. Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties of PGLa-AM1, CPF-AM1, and magainin-AM1: potent activity against oral pathogens. Regul Pept. 2014, 194-195, 63-8. [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Al-Ghaferi, N.; Ahmed, E.; Meetani, M.A.; Leprince, J.; Nielsen, P.F. Orthologs of magainin, PGLa, procaerulein-derived, and proxenopsin-derived peptides from skin secretions of the octoploid frog Xenopus amieti (Pipidae). Peptides. 2010, 31, 989–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Leprince, J.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Takada, K. Purification and properties of antimicrobial peptides from skin secretions of the Eritrea clawed frog Xenopus clivii (Pipidae). Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2011, ;153, 350-4. [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Ahmed, E.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D.; Conlon, J.M. Antimicrobial peptides with therapeutic potential from skin secretions of the Marsabit clawed frog Xenopus borealis (Pipidae). Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010, 152, 467–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechkarska, M.; Prajeep, M.; Radosavljevic, G.D.; Jovanovic, I.P.; Al Baloushi, A.; Sonnevend, A.; Lukic, M.L.; Conlon, J.M. An analog of the host-defense peptide hymenochirin-1B with potent broad-spectrum activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria and immunomodulatory properties. Peptides 2013, 50, 153–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, I.; Scorciapino, M.A.; Manzo, G.; Casu, M.; Rinaldi, A.C.; Attoub, S.; Mechkarska, M.; Conlon, J.M. Conformational analysis and cytotoxic activities of the frog skin host-defense peptide, hymenochirin-1Pa. Peptides 2014, 61, 114–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Galadari, S.; Raza, H.; Condamine, E. Design of potent, non-toxic antimicrobial agents based upon the naturally occurring frog skin peptides, ascaphin-8 and peptide XT-7. Chem Biol Drug Des 2008, 72, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.B.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.C. Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II: buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 244, 253–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirioni, O.; Silvestri, C.; Ghiselli, R.; Orlando, F.; Riva, A.; Gabrielli, E.; Mocchegiani, F.; Cianforlini, N.; Trombettoni, M.M.; Saba, V.; et al. Therapeutic efficacy of buforin II and rifampin in a rat model of Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis. Crit Care Med 2009, 37, 1403–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashaei, F.; Bevalian, P.; Akbari, R.; Pooshang Bagheri, K. Single dose eradication of extensively drug resistant Acinetobacter spp. In a mouse model of burn infection by melittin antimicrobial peptide. Microb Pathog 2019, 127, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, R.; Hakemi-Vala, M.; Pashaie, F.; Bevalian, P.; Hashemi, A.; Pooshang Bagheri, K. Highly synergistic effects of melittin with conventional antibiotics against multidrug-resistant isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Drug Resist 2019, 25, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacometti, A.; Cirioni, O.; Kamysz, W.; D'Amato, G.; Silvestri, C.; Del Prete, M.S.; Łukasiak, J.; Scalise, G. Comparative activities of cecropin A, melittin, and cecropin A-melittin peptide CA(1-7)M(2-9)NH2 against multidrug-resistant nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Peptides 2003, 24, 1315–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayamani, E.; Rajamuthiah, R.; Larkins-Ford, J.; Fuchs, B.B.; Conery, A.L.; Vilcinskas, A.; Ausubel, F.M.; Mylonakis, E. Insect-derived cecropins display activity against Acinetobacter baumannii in a whole-animal high-throughput Caenorhabditis elegans model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 1728–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, S.; Li, R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, S. Transmission electron microscopic morphological study and flow cytometric viability assessment of Acinetobacter baumannii susceptible to Musca domestica cecropin. ScientificWorldJournal 2014, 2014, 657536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, H.G.; Agerberth, B.; Boman, A. Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin P1 and PR-39, two antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect Immun. 1993, 61, 2978–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.M.; Ko, S.; Cheong, M.J.; Bang, J.K.; Seo, C.H.; Luchian, T.; Park, Y. Myxinidin2 and myxinidin3 suppress inflammatory responses through STAT3 and MAPKs to promote wound healing. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 87582–87597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordya, N.; Yakovlev, A.; Kruglikova, A.; Tulin, D.; Potolitsina, E.; Suborova, T.; Bordo, D.; Rosano, C.; Chernysh, S. Natural antimicrobial peptide complexes in the fighting of antibiotic resistant biofilms: Calliphora vicina medicinal maggots. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0173559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Farrés, X.; López-Rojas, R.; Pachón-Ibáñez, M.E.; Teixidó, M.; Pachón, J.; Vila, J.; Giralt, E. Sequence-activity relationship, and mechanism of action of mastoparan analogues against extended-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur J Med Chem. 2015, 101, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, Z.; Al-Samaree, M. Design of synthetic antimicrobial peptides against resistant Acinetobacter baumannii using computational approach. Int J Pharmaceut Sci Res. 2017, 8, 2033–2039255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Lee, M.C.; Tzen, J.T.C.; Lee, H.M.; Chang, S.M.; Tu, W.C.; Lin, C.F. Efficacy of Mastoparan-AF alone and in combination with clinically used antibiotics on nosocomial multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017, 24, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Ikram, A.; Raza, A.; Saeed, S.; Zafar Paracha, R.; Younas, Z.; Khadim, M.T. Therapeutic potential of novel mastoparan-chitosan nanoconstructs against clinical MDR Acinetobacter baumannii: In silico, in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 3755–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağmak Tartar, A.; Özer Balin, Ş.; Akbulut, A.; Yardim, M.; Aydin, S. Roles of dermcidin, salusin-α, salusin-β and TNF-α in the pathogenesis of human brucellosis. Iran J Immunol 2019, 16, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshadzadeh, Z.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Taheri, B.; Ekrami, A.; Modarressi, M.H.; Azimzadeh, M.; Bahador, A. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potencies of dermcidin-derived peptide DCD-1L against Acinetobacter baumannii: an in vivo wound healing model. BMC Microbiol 2022, 22, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, M.J.; Kim, M.K.; Park, Y. Comparative antimicrobial activity of Hp404 peptide and its analogs against Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Sedighian, H.; Mirhosseini, S.A.; Ghazvini, K.; Zare, H.; Jahangiri, A. Antimicrobial peptides as a promising treatment option against Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Microb Pathog 2020, 146, 104238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morroni, G.; Simonetti, O.; Brenciani, A.; Brescini, L.; Kamysz, W.; Kamysz, E.; Neubauer, D.; Caffarini, M.; Orciani, M.; Giovanetti, E.; et al. In vitro activity of Protegrin-1, alone and in combination with clinically useful antibiotics, against Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from surgical wounds. Med Microbiol Immunol 2019, 208, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, N.M.; Zorgani, A.; Jalowicki, G.; Kerr, A.; Khaldi, N.; Martins, M. Unlocking NuriPep 1653 from common pea protein: a potent antimicrobial peptide to tackle a pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 2019, 18, 10:2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Neves, R.C.; Mortari, M.R.; Schwartz, E.F.; Kipnis, A.; Junqueira-Kipnis, A.P. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of peptides from venom of social wasp and scorpion on multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Toxins (Basel) 2019, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejman-Yarden, N.; Robinson, A.; Davidov, Y.; Shulman, A.; Varvak, A.; Reyes, F.; Rahav, G.; Nissan, I. Delftibactin-A, a non-ribosomal peptide with broad antimicrobial activity. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedan, S.; Shubair, Z.; Almaaytah, A. Synergism of cationic antimicrobial peptide WLBU2 with antibacterial agents against biofilms of multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 2019–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 126 Mant, C.; Jiang, Z.; Gera, L.; Davis, T.; Nelson, K.L.; Bevers, S.; Hodges, R.S. De novo designed amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides incorporating dab and dap residues on the polar face to treat the gram-negative pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii. J Med Chem. 2019, 62, 3354–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C.L.; Broberg, C.A.; McCool, E.M.; Lee, W.J.; Chao, A.; McConnell, E.W.; Pritchard, D.A.; Hebert, M.; Fleeman, R.; Adams, J.; et al. The "PepSAVI-MS" pipeline for natural product bioactive peptide discovery. Anal Chem. 2017, 89, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, M.G.; Ferrari, E.; Goddard, A.D.; Lancaster, L.; Sanderson, P.; Miller, C. Mechanistic and phenotypic studies of bicarinalin, BP100 and colistin action on Acinetobacter baumannii. Res Microbiol. 2018, 169, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, S.H.; Murphy, R.A.; Juul-Madsen, K.; Fredborg, M.; Hvam, M.L.; Axelgaard, E.; Skovdal, S.M.; Meyer, R.L.; Sørensen, U.B.S.; Möller, A.; et al. The immunomodulatory drug glatiramer acetate is also an effective antimicrobial agent that kills gram-negative bacteria. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, L.; Mahdi, N.; Al-Kakei, S.; Musafer, H.; Al-Joofy, I.; Essa, R.; Zwain, L.; Salman, I.; Mater, H.; Al-Alak, S.; et al. Treatment strategy by lactoperoxidase and lactoferrin combination: Immunomodulatory and antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb Pathog 2018, 114, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defraine, V.; Schuermans, J.; Grymonprez, B.; Govers, S.K.; Aertsen, A.; Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J.; Lavigne, R.; Briers, Y. Efficacy of artilysin art-175 against resistant and persistent Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemothe 2016, 60, 3480–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Xu, M.; Wang, T.; You, C.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Zhou, H.; Khan, A.; Han, C.; Li, P. Catechol cross-linked antimicrobial peptide hydrogels prevent multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection in burn wounds. Biosci Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenei, S.; Tiricz, H.; Szolomájer, J.; Tímár, E.; Klement, É.; Al Bouni, M.A.; Lima, R.M.; Kata, D.; Harmati, M.; Buzás, K.; et al. Potent chimeric antimicrobial derivatives of the medicago truncatula ncr247 symbiotic peptide. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, R.M.; Rathod, B.B.; Tiricz, H.; Howan, D.H.O.; Al Bouni, M.A.; Jenei, S.; Tímár, E.; Endre, G.; Tóth, G.K.; Kondorosi, É. legume plant peptides as sources of novel antimicrobial molecules against human pathogens. Front Mol Biosci. 2022, 9, 870460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Su, P.Y.; Kuo, S.C.; Lauderdale, T.Y.; Shih, C. Adding a c-terminal cysteine (ctc) can enhance the bactericidal activity of three different antimicrobial peptides. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, R.; Liang, B.B.; An, M.M. In-vitro bactericidal activity of colistin against biofilm-associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. J Hosp Infect 2009, 72, 368–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thandar, M.; Lood, R.; Winer, BY.; Deutsch, D.R.; Euler, C.W.; Fischetti, V. A. novel engineered peptides of a phage lysin as effective antimicrobials against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 671–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, N.; Basardeh, E.; Samiee, F.; Fateh, A.; Shooraj, F.; Rahimi, A.; Shahcheraghi, F.; Vaziri, F.; Masoumi, M.; Pazhouhandeh, M.; et al. The inhibitory effect of the combination of two new peptides on biofilm formation by Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb Pathog 2018, 121, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardbari, AM.; Arabestani, MR.; Karami, M.; Keramat, F.; Aghazadeh, H.; Alikhani, MY.; Bagheri, KP. Highly synergistic activity of melittin with imipenem and colistin in biofilm inhibition against multidrug-resistant strong biofilm producer strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018 Mar;37(3):443-454. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Liu, S.; Lu, Z.; Luo, H.; Tang, X. Antibacterial potential analysis of novel α-helix peptides in the chinese wolf spider Lycosa sinensis. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, P.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, K.; Ni, G.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Wu, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Caerin 1.1 and 1.9 peptides from australian tree frog inhibit antibiotic-resistant bacteria growth in a murine skin infection model. Microbiol Spectr 2021, 9, e0005121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, F.L.; Arenas, I.; Haney, E.F.; Estrada, K.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Corzo, G. Identification of a crocodylian β-defensin variant from Alligator mississippiensis with antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity. Peptides 2021, 141, 170549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A.; Neshani, A.; Mirhosseini, SA.; Ghazvini, K.; Zare, H.; Sedighian, H. Synergistic effect of two antimicrobial peptides, Nisin and P10 with conventional antibiotics against extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and colistin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Microb Pathog 2021, 150, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Ye, X.; Ding, L.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Luo, D.; Liu, N.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z. Identification of the scorpion venom-derived antimicrobial peptide Hp1404 as a new antimicrobial agent against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb Pathog 2021, 157, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.J.; Kim, M.K.; Park, Y. Comparative antimicrobial activity of Hp404 peptide and its analogs against Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawant, E.S.; Hutchinson, J.; Gašparíková, D.; Lockey, C.; Pruñonosa Lara, L.; Guy, C.; Brooks, R.L.; Dixon, AM. Molecular basis of selectivity and activity for the antimicrobial peptide lynronne-1 informs rational design of peptide with improved activity. Chembiochem 2021, 22, 2430–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, A.; Swain, S.S.; Behera, A.; Sahoo, G.; Mahapatra, P.K.; Panda, S.K. Antimicrobial peptides derived from insects offer a novel therapeutic option to combat biofilm: a review. Front Microbiol 2021, 10, 661195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kang, H.K.; Park, E.; Kim, M.K.; Park, Y. Bactericidal activities and action mechanism of the novel antimicrobial peptide Hylin a1 and its analog peptides against Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Eur J Pharm Sci 2022, 175, 106205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, F.; Bitossi, C.; Casciaro, B.; Loffredo, M.R.; Fabiano, G.; Torrini, L.; Raponi, F.; Raponi, G.; Mangoni, ML. The antimicrobial peptide Esc(1-21) synergizes with colistin in inhibiting the growth and in killing multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolatchiev, A. Antimicrobial peptides Epinecidin-1 and Beta-Defesin-3 are effective against a broad spectrum of antibiotic-resistant bacterial isolates and increase survival rate in experimental sepsis. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; van Gent, M.E.; de Waal, A.M.; van Doodewaerd, B.R.; Bos, E.; Koning, R.I.; Cordfunke, R.A.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Nibbering, P.H. Physical and functional characterization of plga nanoparticles containing the antimicrobial peptide SAAP-148. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Long, H.; Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; Wang, T.; Zeng, Z.; Guo, G.; Wu, J. Antibacterial mechanism of peptide Cec4 against Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 417–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Mao, C.; Li, L.; Cao, H.; Qiu, Z.; Guo, G.; Liang, G.; Shen, F. Antimicrobial peptide Cec4 eradicates multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro and in vivo. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023, 30, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapaksha, D.C.; Jayathilaka, E.H.T.T.; Edirisinghe, S.L.; Nikapitiya, C.; Lee, J.; Whang, I.; De Zoysa, M. Octopromycin: Antibacterial and antibiofilm functions of a novel peptide derived from Octopus minor against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2021, 117, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, J.C.M.; Willliam, G.L.; Resende, J.M.; Assis, D.C.S.; Boff, D.; Cardoso, V.N.; Amaral, F.A.; Souza-Fagundes, E.M.; Fernandes, S.O.A.; Lima, M.E. Pegylated LyeTx I-b peptide is effective against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in an in vivo model of pneumonia and shows reduced toxicity. Int J Pharm 2021, 609, 121156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, P.; Yi, L.; Xu, J.; Gao, W.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Chan, KF.; Wong, KY. Investigation of antibiofilm activity, antibacterial activity, and mechanistic studies of an amphiphilic peptide against Acinetobacter baumannii. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howan, D.H.O.; Jenei, S.; Szolomajer, J.; Endre, G.; Kondorosi, É.; Tóth, G.K. Enhanced antibacterial activity of substituted derivatives of NCR169C peptide. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, S.; Michaeli, J.; Nur, N.; Erbetti, I.; Zazoun, J.; Ferrari, L.; Felici, A.; Cohen-Kutner, M.; Bachnoff, N. OMN6 a novel bioengineered peptide for the treatment of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, J.; Mandel, S.; Maximov, S.; Zazoun, J.; Savoia, P.; Kothari, N.; Valmont, T.; Ferrari, L.; Duncan, LR.; Hawser, S.; et al. In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial activity of the novel peptide OMN6 against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; An, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Wang, K.J. The antimicrobial peptide lj-hep2 from Lateolabrax japonicus exerting activities against multiple pathogenic bacteria and immune protection in vivo. Mar Drugs 2022, 20, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorr, S.U.; Brigman, H.V.; Anderson, J.C.; Hirsch, E.B. The antimicrobial peptide DGL13K is active against drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria and sub-inhibitory concentrations stimulate bacterial growth without causing resistance. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0273504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Morales, J.; Guardiola, S.; Ballesté-Delpierre, C.; Giralt, E.; Vila, J. A new synthetic protegrin as a promising peptide with antibacterial activity against MDR Gram-negative pathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022, 77, 3077–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Prats-Ejarque, G.; Torrent, M.; Andreu, D.; Brandenburg, K.; Fernández-Millán, P.; Boix, E. In vivo evaluation of ecp peptide analogues for the treatment of Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.; Hua, X.; Zhou, R.; Cui, J.; Wang, T.; Kong, F.; You, H.; Liu, X.; Adu-Amankwaah, J.; Guo, G.; et al. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities of MAF-1-derived antimicrobial peptide Mt6 and its D-enantiomer D-Mt6 against Acinetobacter baumannii by targeting cell membranes and lipopolysaccharide interaction. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0131222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayathilaka, E.H.T.T.; Rajapaksha, D.C.; Nikapitiya, C.; De Zoysa, M.; Whang, I. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm peptide octominin for controlling multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilaka, E.H.T.T.; Nikapitiya, C.; De Zoysa, M.; Whang, I. Antimicrobial peptide octominin-encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles enhanced antifungal and antibacterial activities. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacioglu, M.; Oyardi, O.; Bozkurt-Guzel, C.; Savage, PB. Antibiofilm activities of ceragenins and antimicrobial peptides against fungal-bacterial mono and multispecies biofilms. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2020, 73, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, F.W.; Wang, W.X.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Sun, S.Y.; Yu, J.H.; Vitek, M.P.; Li, G.F.; Ma, R.; Wang, S.; et al. Apolipoprotein E mimetic peptide COG1410 combats pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 934765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denardi, L.B.; de Arruda Trindade, P.; Weiblen, C.; Ianiski, LB.; Stibbe, PC.; Pinto, SC.; Santurio, J.M. In vitro activity of the antimicrobial peptides h-Lf1-11, MSI-78, LL-37, fengycin 2B, and magainin-2 against clinically important bacteria. Braz J Microbiol 2022, 53, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshtiaghi, S.; Nazari, R.; Fasihi-Ramandi, M. Molecular docking, anti-biofilm & antibacterial activities and therapeutic index of mCM11 peptide on Acinetobacter baumannii strains. Curr Microbiol 2023, 80, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzi, N.; Oloomi, M.; Bahramali, G.; Siadat, S.D.; Bouzari, S. Antibacterial properties and efficacy of LL-37 fragment GF-17D3 and scolopendin A2 peptides against resistant clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii in vitro and in vivo model studies. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Torre, C.; Sannio, F.; Battistella, M.; Docquier, J.D.; De Zotti, M. Peptaibol analogs show potent antibacterial activity against multidrug resistant opportunistic pathogens. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.F.; Hamed, M.I.; Panitch, A.; Seleem, M.N. Targeting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with short salt-resistant synthetic peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.F.; Brezden, A.; Mohammad, H.; Chmielewski, J.; Seleem, M.N. A short D-enantiomeric antimicrobial peptide with potent immunomodulatory and antibiofilm activity against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 6953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; He, G.; Wan, Y.; Yu, C.; Tang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; rt, al. In vitro and in vivo activities of antimicrobial peptides developed using an amino acid-based activity prediction method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 5342–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, R.; Yang, L. Synergistic effects of antimicrobial peptide DP7 combined with antibiotics against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cheng, X.; Lian, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L. Efficacy of antimicrobial peptide DP7, designed by machine-learning method, against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, D.; Roy, N.; Kulkarni, O.; Nanajkar, N.; Datey, A.; Ravichandran, S.; Thakur, C.T.S.; Aprameya, I.V.; Sarma, S.P.; Chakravortty, D.; et al. Ω76: A designed antimicrobial peptide to combat carbapenem- and tigecycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaax–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.P.; Chen, E.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Kuo, P.S.; Jan, H.M.; Yang, T.C.; Hsieh, M.Y.; Lee, KT.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, R.P. A systematic study of the stability, safety, and efficacy of the de novo designed antimicrobial peptide PepD2 and its modified derivatives against Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 678330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, M.; Choi, J.; Jang, A.; Yoon, YK.; Kim, Y. Antiseptic 9-Meric peptide with potency against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 12520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazam, P.K.; Cheng, C.C.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Hsu, P.H.; Chen, T.L.; Lee, Y.T.; Chen, J.Y. Development of bactericidal peptides against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii with enhanced stability and low toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, S.R.; de Sardi, J.C.O.; Júnior, E.C.; Marchetto, R.; Wender, H.; Vargas, L.F.P.; de Miranda, A.; Almeida, C.V.; de Oliveira Almeida, L.H.; de Oliveira, C.F.R.; et al. The synthetic antimicrobial peptide IKR18 displays anti-infectious properties in Galleria mellonella in vivo model. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2022, 1866, 130244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, R.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.K.; Chae, J.D.; Son, B.K.; Seo, C.H.; Park, Y. Synergistic effects and antibiofilm properties of chimeric peptides against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 1622–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heulot, M.; Jacquier, N.; Aeby, S.; Le Roy, D.; Roger, T.; Trofimenko, E.; Barras, D.; Greub, G.; Widmann, C. The anticancer peptide TAT-RasGAP317-326 exerts broad antimicrobial activity. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizzarro, G.; Jacquier, N. In vitro synergistic action of TAT-RasGAP317-326 peptide with antibiotics against Gram-negative pathogens. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2022, 31, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, T.; Hargraves, S.; Georgieva, M.; Widmann, C.; Jacquier, N. The antimicrobial peptide TAT-RasGAP317-326 inhibits the formation and expansion of bacterial biofilms in vitro. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021, 25, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, B.; Mohammadi, M.; Momenzadeh, N.; Farshadzadeh, Z.; Roozbehani, M.; Dehghani, P.; Hajian, S.; Darvishi, S.; Shamseddin, J. Substitution of lysine for isoleucine at the center of the nonpolar face of the antimicrobial peptide, piscidin-1, leads to an increase in the rapidity of bactericidal activity and a reduction in toxicity. Infect Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 1629–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jang, A.; Yoon, Y.K.; Kim, Y. development of novel peptides for the antimicrobial combination therapy against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jariyarattanarach, P.; Klubthawee, N.; Wongchai, M.; Roytrakul, S.; Aunpad, R. Novel D-form of hybrid peptide (D-AP19) rapidly kills Acinetobacter baumannii while tolerating proteolytic enzymes. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, I.K.L.; Thomsen, T.T.; Rashid, J.; Bobak, T.R.; Oddo, A.; Franzyk, H.; Løbner-Olesen, A.; Hansen, PR. C-locked analogs of the antimicrobial peptide BP214. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.; Lapuebla, A.; Landman, D.; Quale, J. In vitro and in vivo activity of a novel antisense peptide nucleic acid compound against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb Drug Resist 2019, 25, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtada, R.; Herce, H.D.; Yin, D.J.; Moroco, J.A.; Wales, T.E.; Engen, J.R.; Walensky, L.D. Design of stapled antimicrobial peptides that are stable, nontoxic and kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria in mice. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Choudhary, M.; Vashistt, J.; Shrivastava, R.; Bisht, G.S. Cationic antimicrobial peptide and its poly-N-substituted glycine congener: Antibacterial and antibiofilm potential against A. baumannii. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 518, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostorhazi, E.; Hoffmann, R.; Herth, N.; Wade, J.D.; Kraus, C.N.; Otvos, L., Jr. Advantage of a narrow spectrum host defense (antimicrobial) peptide over a broad spectrum analog in preclinical drug development. Front Chem 2018, 6, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Duan, H.; Li, M.; Xu, W.; Wei, L. Characterization and mechanism of action of amphibian-derived wound-healing-promoting peptides. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1219427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kościuczuk, E.M.; Lisowski, P.; Jarczak, J.; Strzałkowska, N.; Jóźwik, A.; Horbańczuk, J.; Krzyżewski, J.; Zwierzchowski, L.; Bagnicka, E. Cathelicidins: family of antimicrobial peptides. A review. Mol Biol Rep 2012, 39, 10957–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowzicky, M.J.; Chmelařová, E. Antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria collected from eastern Europe: results from the tigecycline evaluation and surveillance trial (T. E.S.T.), 2011-2016. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019, 17, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björstad, A.; Askarieh, G.; Brown, K.L.; Christenson, K.; Forsman, H.; Onnheim, K.; Li, HN.; Teneberg, S.; Maier, O.; Hoekstra, D.; et al. The host defense peptide LL-37 selectively permeabilizes apoptotic leukocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 1027–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, Y.; Chen, Q.; Schmidt, A.P.; Anderson, G.M.; Wang, J.M.; Wooters, J.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Chertov, O. LL-37 the neutrophil granule-and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils monocytes and T cells. J Exp Med 2000, 192, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, A.; Hancock, R.E.W. Host defense peptides: Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activity and potential applications for tackling antibiotic-resistant infections. Emerg Health Threats J 2009, 2, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Zare, H.; Eidgahi, M.R.A.; Kakhki, R.K.; Safdari, H.; Khaledi, A.; Ghazvini, K. LL-37: A review of antimicrobial profile against sensitive and antibiotic-resistant human bacterial pathogens. Gene Rep 2019, 17, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiyari, R.; Halabian, R.; Behzadi, E.; Sedighian, H.; Jafari, R.; Fooladi, A.A.I. Performance evaluation of antimicrobial peptide ll-37 and hepcidin and β-defensin-2 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisma, E.M.; de Breij, A.; Chan, H.; van Dissel, J.T.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Hiemstra, P.S.; El Ghalbzouri, A.; Nibbering, P.H. LL-37-derived peptides eradicate multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from thermally wounded human skin equivalents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 4411–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deslouches, B.; Steckbeck, J.D.; Craigo, J.K.; Doi, Y.; Mietzner, T.A.; Montelaro, R.C. Rational design of engineered cationic antimicrobial peptides consisting exclusively of arginine and tryptophan, and their activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013, 57, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Shan, B.; Qi, J.; Ma, Y. Systemic responses of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii following exposure to the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin-BF imply multiple intracellular targets. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gan, T.X.; Liu, X.D.; Jin, Y.; Lee, W.H.; Shen, J.H.; et al. Identification and characterization of novel reptile cathelicidins from elapid snakes. Peptides 2008, 29, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Samuel, R.L.; Massiah, M.A.; Gillmor, S.D. The structure and behavior of the NA-CATH antimicrobial peptide with liposomes. Biochim Biophy Acta 2015, 1848, 2394–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, B.M.; Juba, M.L.; Devine, M.C.; Barksdale, S.M.; Rodriguez, C.A.; Chung, M.C.; et al. Bioprospecting the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) host defense peptidome. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0117394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, K.A.; Digby, M.R.; Lefévre, C.; Nicholas, K.R.; Deane, E.M.; Williamson, P. Identification characterization and expression of cathelicidin in the pouch young of Tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Comp Biochem Physiol Part B, Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 149, 524-533. [CrossRef]

- Selsted, M.E.; Novotny, M.J.; Morris, W.L.; Tang, Y.Q.; Smith, W.; Cullor, J.S. Indolicidin is a novel bactericidal tridecapeptide amide from neutrophils. J Biol Chem 1992, 267, 4292–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Végh, A.G.; Nagy, K.; Bálint, Z.; Kerényi, A.; Rákhely, G.; Váró, G.; Szegletes, Z. Effect of antimicrobial peptide-amide: Indolicidin on biological membranes. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011, 2011, 670589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Chen, C.; Jou, M.L.; Lee, A.Y.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Yu, Y.P.; Huang, W.T.; Wu, S.H. Structural and DNA-binding studies on the bovine antimicrobial peptide indolicidin: Evidence for multiple conformations involved in binding to membranes and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 2005, 33, 4053–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, C.; Krajewski, K.; Lee, H.F.; Antony, S.; Johnson, A.A.; Amin, R.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; Pommier, Y. Covalent binding of the natural antimicrobial peptide indolicidin to DNA abasic sites. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34, 5157–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutelski, S.; Awad, M.; Łukasz, N.; Bukowski, M.; Śmiałek, J.; Suder, P.; Dubin, G.; Mak, P. Isolation, identification, and bioinformatic analysis of antibacterial proteins and peptides from immunized hemolymph of red palm weevil Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.J.; Unholzer, A.; Schaller, M.; Schäfer-Korting, M.; Korting, H.C. Human defensins. J Mol Med(Berlin, Germany) 2005, 83, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, R.I.; Lu, W. α-Defensins in human innate immunity. Immunol Rev 2012, 45, 84–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, G.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, X.; Zeng, H.; et al. A simplified derivative of human defensin 5 with potent and efficient activity against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antim Agents Chemoth 2018, 62, e01504–e01517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanniarachchi, Y.A.; Kaczmarek, P.; Wan, A.; Nolan, E.M. Human defensin 5 disulfide array mutants: Disulfide bond deletion attenuates antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 2011, 37, 8005–8017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcelino-Pérez, G.; Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Gallardo-Hernández, S.; Xoconostle-Cázares, B. Adsorption of recombinant human β-defensin 2 and two mutants on mesoporous silica nanoparticles and its effect against Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. Michiganensis. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2021, 11, 8–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schibli, D.J.; Hunter, H.N.; Aseyev, V.; Starner, T.D.; Wiencek, J.M.; McCray, P.B.; Tack, B.F.; Vogel, H.J. The solution structures of the human beta-defensins lead to a better understanding of the potent bactericidal activity of HBD3 against Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 8279–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, T.; Spielmann, M.; Zuhaili, B.; Fossum, M.; Metzig, M.; Koehler, T.; et al. Human beta defensin-3 promotes wound healing in infected diabetic wounds. J Gene Med 2009, 11, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerweck, J.; Strandberg, E.; Kukharenko, O.; Reichert, J.; Bürck, J.; Wadhwani, P.; Ulrich, A.S. Molecular mechanism of synergy between the antimicrobial peptides PGLa and magainin 2. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamba, Y.; Yamazaki, M. Magainin 2-induced pore formation in the lipid membranes depends on its concentration in the membrane interface. J Physical Chem B 2009, 113, 486–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloy, W.L.; Kari, U.P. Structure-activity studies on magainins and other host defense peptides. Biopolymers 1995, 37, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottler, L.M.; Ramamoorthy, A. Structure membrane orientation mechanism and function of pexiganan-a highly potent antimicrobial peptide designed from magainin. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1788, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramamoorthy, A.; Thennarasu, S.; Lee, D.K.; Tan, A.; Maloy, L. Solid-state NMR investigation of the membrane-disrupting mechanism of antimicrobial peptides MSI-78 and MSI-594 derived from magainin 2 and melittin. Biophysical J 2006, 91, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, P.C.; Barry, A.L.; Brown, S.D. In vitro antimicrobial activity of MSI-78 a magainin analog. Antim Agents Chemoth 1998, 42, 1213–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevier, C.R.; Sonnevend, A.; Kolodziejek, J.; Nowotny, N.; Nielsen, P.F.; Conlon, J.M. Purification and characterization of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the mink frog (Rana septentrionalis). Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2004, 139, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Abraham, B.; Sonnevend, A.; Jouenne, T.; Cosette, P.; Leprince, J.; et al. Purification and characterization of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the carpenter frog Rana virgatipes (Ranidae, Aquarana). Reg Peptides 2005, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelyeva, A.; Ghavami, S.; Davoodpour, P.; Asoodeh, A.; Los, M.J. An overview of Brevinin superfamily: Structure function and clinical perspectives. Adv Exp Med Biol 2014, 818, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, S.; Urbán, E.; Lukic, M.; Conlon, J.M. Peptides with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities that have therapeutic potential for treatment of acne vulgaris. Peptides 2012, 34, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, S.; Djurdjevic, P.; Zaric, M.; Mijailovic, Z.; Avramovic, D.; Baskic, D. Effects of host defense peptides B2RP Brevinin-2GU D-Lys-Temporin Lys-XT-7 and DLys-Ascaphin-8 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells: Preliminary study. Periodicum Biologorum 2017, 119, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, J.M.; Demandt, A.; Nielsen, P.F.; Leprince, J.; Vaudry, H.; Woodhams, D.C. The alyteserins: Two families of antimicrobial peptides from the skin secretions of the midwife toad Alytes obstetricans (Alytidae). Peptides 2009, 30, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. APD3: The antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 44, D1087–D1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, J.M.; Prajeep, M.; Mechkarska, M.; Coquet, L.; Leprince, J.; Jouenne, T.; Vaudry, H.; King, J.D. Characterization of the host-defense peptides from skin secretions of Merlin's clawed frog Pseudhymenochirus merlini: Insights into phylogenetic relationships among the Pipidae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genomic Proteonomics 2013, 8, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Soto, A.; Knoop, F.C.; Conlon, J.M. Antimicrobial peptides isolated from skin secretions of the diploid frog Xenopus tropicalis (Pipidae). Biochim Biophys Acta 2001, 1550, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.B.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.C. A novel antimicrobial peptide from Bufo bufo gargarizans. Biochem Biophy Res Commun 1996, 218, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apponyi, M.A.; Pukala, T.L.; Brinkworth, C.S.; Maselli, V.M.; Bowie, J.H.; Tyler, M.J.; Booker, G.W.; Wallace, J.C.; Carver, J.A.; Separovic, F. Host-defence peptides of Australian anurans: structure, mechanism of action and evolutionary significance. Peptides 2004, 25, 1035–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.S.; Ferreira, T.C.G.; Cilli, E.M.; Crusca JR, E.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S.; Sebben, A.; Ricart, C.A.O.; Sousa, M.V.; Fontes, W. Hylin a1, the first cytolytic peptide isolated from the arboreal South American frog Hypsiboas albopunctatus (“spotted treefrog”). Peptides 2009, 30, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Ross, N.W.; Mackinnon, S.L. Comparison of the biochemical composition of normal epidermal mucus and extruded slime of hagfish (Myxine glutinosa L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol 2008, 25, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.E. Innate host defense mechanisms of fish against viruses and bacteria. Dev Comp Immunol 2001, 25, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silphaduang, U.; Noga, E.J. Peptide antibiotics in mast cells of fish. Nature 2001, 414, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noga, E.J.; Silphaduang, U.; Park, N.G.; Seo, J.K.; Stephenson, J.; Kozlowicz, S. Piscidin 4, a novel member of the piscidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 2009, 152, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.C.; Lee, S.H.; Hour, A.L.; Pan, C.Y.; Lee, L.H.; Chen, J.Y. Five diferent piscidins from Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus: analysis of their expressions and biological functions. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.M.; Weis, P.; Diamond, G. Isolation and characterization of pleurocidin, an antimicrobial peptide in the skin secretions of winter flounder. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 12008–12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, R.; Tong, Z.; Lin, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, W.; Kuang, R.; Wang, P.; Tian, Y.; Ni, L. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of pleurocidin against cariogenic microorganisms. Peptides 2011, 32, 1748–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.G. Structure–antimicrobial activity relationship between pleurocidin and its enantiomer. Exp Mol Med 2008, 40, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrzykat, A.; Friedrich, C.L.; Zhang, L.; Mendoza, V.; Hancock, R.E.W. Sublethal concentrations of pleurocidin-derived antimicrobial peptides inhibit macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002, 46, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.G. Influence of the hydrophobic amino acids in the N- and Cterminal regions of pleurocidin on antifungal activity. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 20, 1192–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazam, P.K.; Cheng, C.C.; Lin, W.C.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Chen, J.Y. Strategic modification of low-active natural antimicrobial peptides confers ability to neutralize pathogens in vitro and in vivo. 2022; Unpublished.

- Hazam, P.K.; Chen, J.Y. Therapeutic utility of the antimicrobial peptide Tilapia Piscidin 4 (TP4). Aquac Rep 2020, 17, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Neitz, S.; Mägert, H.J.; Schulz, A.; Forssmann, W.G.; Schulz-Knappe, P.; Adermann, K. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett 2000, 480, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Valore, E.V.; Waring, A.J.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin, a urinary antimicrobial peptide synthesized in the liver. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 7806–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.C.; Acton, R.T. Hepcidin, iron, and bacterial infection. Vitam Horm 2019, 110, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shike, H.; Lauth, X.; Westerman, M.E.; Ostland, V.E.; Carlberg, J.M.; Van Olst, J.C.; Shimizu, C.; Bulet, P.; Burns, J.C. Bass hepcidin is a novel antimicrobial peptide induced by bacterial challenge. Eur J Biochem 2002, 269, 2232–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, A.; Verghese, B. Evidence for positive Darwinian selection on the hepcidin gene of Perciform and Pleuronectiform fishes. Mol Divers 2007, 11, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, K.B.; Lambert, L.A. Molecular evolution and characterization of hepcidin gene products in vertebrates. Gene 2008, 415, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.J.; Cai, J.J.; Cai, L.; Qu, H.D.; Yang, M.; Zhang, M. Cloning and expression of a hepcidin gene from a marine fish (Pseudosciaena crocea) and the antimicrobial activity of its synthetic peptide. Peptides 2009, 30, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.V.; Caldas, C.; Vieira, I.; Ramos, M.F.; Rodrigues, P.N. Multiple hepcidins in a teleost fish, Dicentrarchus labrax: Different hepcidins for differen roles. J Immunol 2015, 195, 2696–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell JF, Shipman WH, Cole LJ. Antibacterial action of melittin, a polypeptide from bee venom. Proceed Soc Exp Biol Med 1968, 127, 707-710. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.V.; de Barros, G.; Pinto, E.G.; Tempone, A.G.; Orsi, R.O.; Dos Santos, L.D.; et al. Melittin induces in vitro death of Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum by triggering the cellular innate immune response. J Venom Animals Toxins Trop Dis 2016, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kwon, O.; An, H.J.; Park, K.K. Antifungal effects of bee venom components on Trichophyton rubrum: A novel approach of bee venom study for possible emerging antifungal agent. Annals Dermatol 2018, 30, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Chaturvedi, P.K.; Chun, S.N.; Lee, Y.G.; Ahn, W.S. Honeybee venom possesses anticancer and antiviral effects by differential inhibition of HPV E6 and E7 expression on cervical cancer cell line. Oncology Rep 2015, 33, 1675–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bogaart, G.; Guzman, J.V.; Mika, J.T.; Poolman, B. On the mechanism of pore formation by melittin. J Biol Chem 2008, 283, 33854–33857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, K.; Lechuga, G.C.; Almeida Souza, A.L.; Carvalho, J.P.R.S.; Villas-Bôas, M.H.S.; De Simone, S.G. Pan-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii but not other strains are resistant to the bee venom peptide melittin. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 149, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casteels, P.; Ampe, C.; Jacobs, F.; Vaeck, M.; Tempst, P. Apidaecins: Antibacterial peptides from honeybees. EMBO J 1989, 8, 2387–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovsky, D.; Rougé, P.; Shatters, R.G. Jr. Bactericidal properties of proline-rich Aedes aegypti trypsin modulating oostatic factor (AeaTMOF). Life (Basel) 2022, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Patočka, J.; Kuča, K. Insect Antimicrobial peptides, a mini review. Toxins (Basel). 2018, 10, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, H.; Hultmark, D.; Engström, Å.; Bennich, H.; Boman, H.G. Sequence and specificity of two antibacterial proteins involved in insect immunity. Nature 1981, 292, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, L.; Leung, K.; Chen, H.M. The combined effects of antibacterial peptide cecropin a and anticancer agents on leukemia cells. Anticancer Research 2002, 22, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.; Hong, J.; Jung, Y.; Ha, J.; Kim, H.; Myung, H; Song, M.J. Bactericidal effect of Cecropin A fused endolysin on drug-resistant gram-negative pathogens. Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 32, 816-823. [CrossRef]

- Mandel, S.; Michaeli, J.; Nur, N.; Erbetti, I.; Zazoun, J.; Ferrari, L.; Felici, A.; Cohen-Kutner, M.; Bachnoff, N. OMN6 a novel bioengineered peptide for the treatment of multidrug resistant Gram negative bacteria. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Giralt, E. Three valuable peptides from bee and wasp venoms for therapeutic and biotechnological use: Melittin apamin and mastoparan. Toxins 2015, 7, 1126–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Xi, X.; Bininda-Emonds, O.R.P.; Shaw, C.; Chen, T.; Zhou, M. Evaluation of the bioactivity of a mastoparan peptide from wasp venom and of its analogues designed through targeted engineering. Int J Biol Sci 2018, 14, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burian, M.; Schittek, B. The secrets of dermcidin action. Int J Med Microbiol 2015, 305, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeth, K.; Méndez-Vilas, A. Structure and mechanism of human antimicrobial peptide dermcidin and its antimicrobial potential microb pathog strateg combat them. Sci Technol Educ 2013, p.1333-1342.

- Liu, C.; Qi, J.; Shan, B.; Ma, Y. Tachyplesin causes membrane instability that kills multidrug-resistant bacteria by inhibiting the 3-ketoacyl carrier protein reductase FabG. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.J.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, H.; Guo, L.X.; Liu, Z.H.; Shi, X.L.; Hu, M. In vitro potential of Lycosin-I as an alternative antimicrobial drug for treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014, 58, 6999–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Dai, C.; Li, Z.; Fan, Z.; Song, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of a scorpion venom peptide derivative in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2012, 7, e40135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, L.B.; Girdwood, S.E.; Cookson, A.R.; Fernandez-Fuentes, N.; Privé, F.; Vallin, H.E.; Wilkinson, T.J.; Golyshin, P.N.; Golyshina, O.V.; Mikut, R.; et al. The rumen microbiome: an underexplored resource for novel antimicrobial discovery. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2017, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, A.; Lee, E.; Jeon, D.; Park, Y.G.; Bang, J.K.; Park, Y.S.; Shin, S.Y.; Kim, Y. Peptoid-substituted hybrid antimicrobial peptide derived from papiliocin and magainin 2 with enhanced bacterial selectivity and anti-inflammatory activity. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 3921–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klubthawee, N.; Adisakwattana, P.; Hanpithakpong, W.; Somsri, S.; Aunpad, R. A novel, rationally designed, hybrid antimicrobial peptide, inspired by cathelicidin and aurein, exhibits membrane-active mechanisms against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 2021, 10, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre, R.; Melo, M.N.; Correia, A.D.; Feliu, L.; Bardaji, E.; Planas, M.; Castanho, M. Synergistic effects of the membrane actions of cecropin-melittin antimicrobial hybrid peptide BP100. Biophys J 2009, 96, 1815–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, A.; Thomsen, T.T.; Kjelstrup, S.; Gorey, C.; Franzyk, H.; Frimodt-Møller, N.; Løbner-Olesen, A.; Hansen, P.R. An all-D amphipathic undecapeptide shows promising activity against colistin-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii and a dual mode of action. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageitos, J.M.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Calo-Mata, P.; Villa, T.G. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): Ancient compounds that represent novel weapons in the fight against bacteria. Biochem Pharmacol 2017, 133, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.I.; Hughes, D.; Kubicek-Sutherland, J.Z. Mechanisms and consequences of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Drug Resist Updat 2016, 26, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravej, H.; Moravej, Z.; Yazdanparast, M.; Heiat, M.; Mirhosseini, A.; Moghaddam, M.M. , Mirnejad R. Antimicrobial peptides: Features action and their resistance mechanisms in bacteria. Microb Drug Resist 2018, 24, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.S.; Fu, C.I.; Otto, M. Bacterial strategies of resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2016, 371, 20150292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omardien, S.; Brul, S.; Zaat, S.A.J. Antimicrobial activity of cationic antimicrobial peptides against gram-positive: Current progress made in understanding the mode of action and the response of bacteria. Front Cell Develop Biol 2016, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Tomida, J.; Kawamura, Y. MexXY multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front Microbiol 2012, 3, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B.; Gorr, S.U. Antimicrobial peptides: Mechanisms of action and resistance. J Dental Res 2017, 96, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannot, K.; Bolard, A.; Plésiat, P. Resistance to polymyxins in gram-negative organisms. Int. J Antimicr Ag 2017, 49, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X.; et al., Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.L.; Harris, P.N.A. Colistin resistance: A major breach in our last line of defense. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, 132–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnair, C.R.; Stokes, J.M.; Carfrae, L.A.; Fiebig-Comyn, A.A.; Coombes, B.K.; Mulvey, M.R.; Brown, E.D. Overcoming mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance with colistin in combination with other antibiotics. Nature Commun 2018, 9, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, I.; Saviuc, C.; Ciubuca, B.; Lazar, V.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Chapter 8—Nano drug delivery. In: Grumezescu, A.M, Ed. Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Therapy. Norwich NY USA: William Andrew Publishing; 2019. pp. 225-244. ISBN: 978-0-12-816505-8.

- Sun, B.; Wibowo, D.; Middelberg, A.P.J.; Zhao, C.X. Cost-effective downstream processing of recombinantly produced pexiganan peptide and its antimicrobial activity. AMB Express 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Zare, H.; Akbari Eidgahi, M.R.; Khaledi, A.; Ghazvini, K. Epinecidin-1, a highly potent marine antimicrobial peptide with anticancer and immunomodulatory activities. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2019, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Tanhaeian, A.; Zare, H.; Eidgahi, M.R.A.; Ghazvini, K. Preparation and evaluation of a new biopesticide solution candidate for plant disease control using pexiganan gene and Pichia pastoris expression system. Gene Rep 2019, 17, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peptide | Source | Sequence (nº amino acid) | Structure | MIC against A. baumannii (μg/mL) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic-susceptible | MDR | |||||

| LL-37 | H. sapiens | LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIK DFLRNLVPRTES (37aa) | AH | 32 | 16–32 | [61,62] |

| KR-30 | H. sapiens | KSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLV PRTES (30aa) | AH | 16 | 8–16 | [62] |

| KR-20 | H. sapiens | KRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES (20aa) | AH | 64 | 16–32 | [62] |

| KS-12 | H. sapiens | KRIVQRIKDFLR (12aa) | AH | 256 | 64–256 | [62] |

| SAAP-148 | H. sapiens | LKRVWKRVFKLLKRYWRQLKKPVR (24aa) | AH | — | 6 | [63] |

| CATH-BF derivative (Cath-A and OH- | Bungarus fasciatus (Snake venom) | KFFRKLKKSVKKRAKEFFKKPRVI GVSIPF(30aa) | AH | — | 8–32 | [64] |

| ZY4 cathelicidin-BF-15 derived | Bungarus fasciatus (Snake venom) | VCKRWKKWKR KWKKWCV-NH2 (17aa) | Cyclic SH-bridge | — | 4.6–9.4 | [65] |

| NA-CATH | Naja atra (Snake venom) | KRFKKFFKKLKNSVKKRAKKFFKK PKVIGVTFPF (34aa) | AH | 10 | 10 | [66] |

| OH-CATH30 | King cobra (Snake venon) | KFFKKLKNSVKKRAKKFFKKPRVI GVSIPF(30aa) | AH | 10 | 10 | [67] |

| DOH-CATH30 | King cobra (Snake venon) | KFFKKLKNSVKKRAKKFFKKPRVIGVSIPF (30aa) | AH | — | 1.56–12.5 | [67] |