Submitted:

07 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

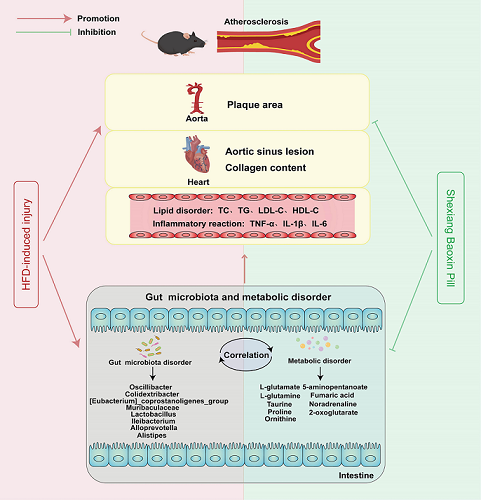

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

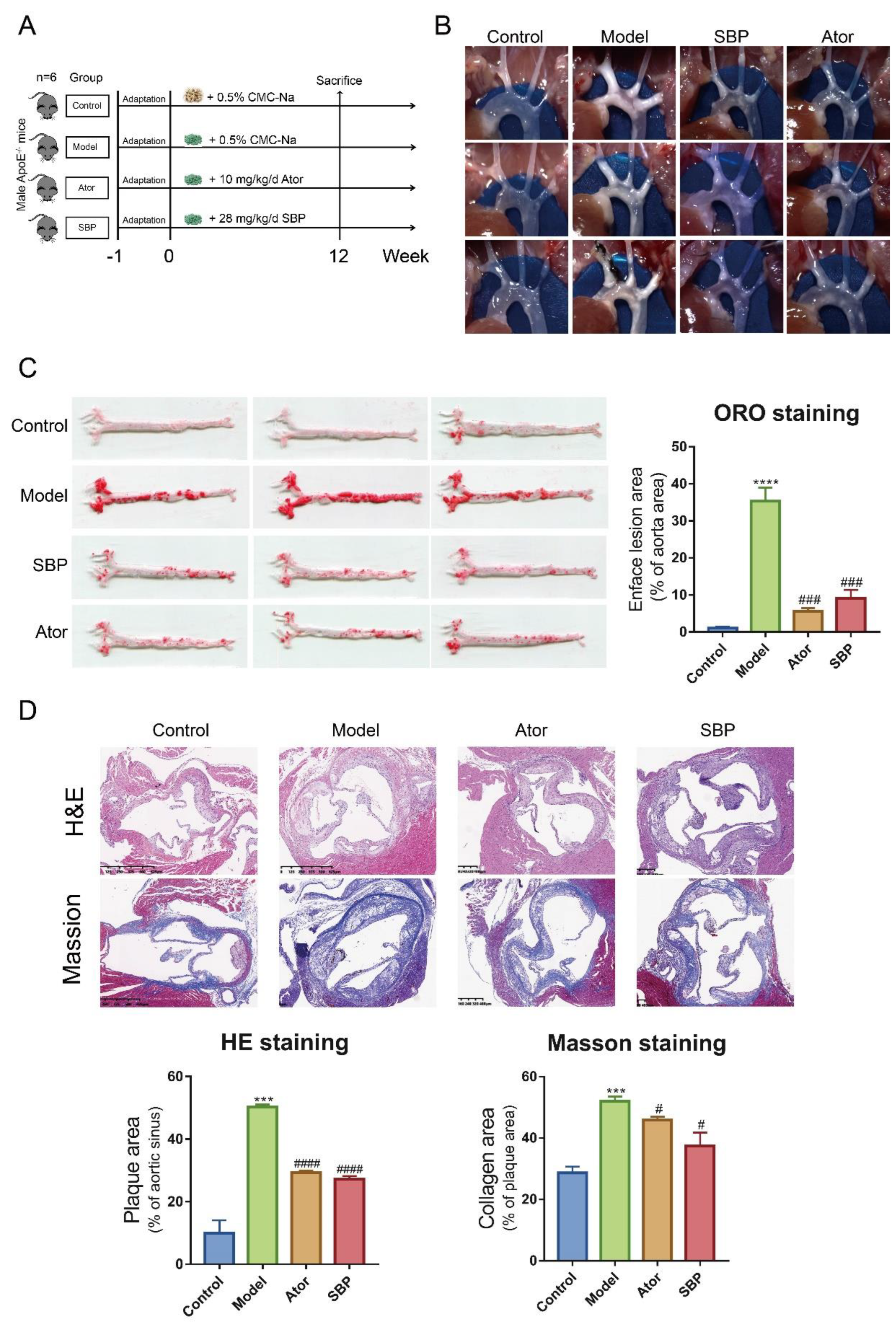

2.1. SBP Ameliorated Atherosclerotic Lesions in HFD-Induced apoE-/- Mice

2.2. SBP Improved Lipid Profiles and Systemic Inflammation in HFD-Induce apoE-/- Mice

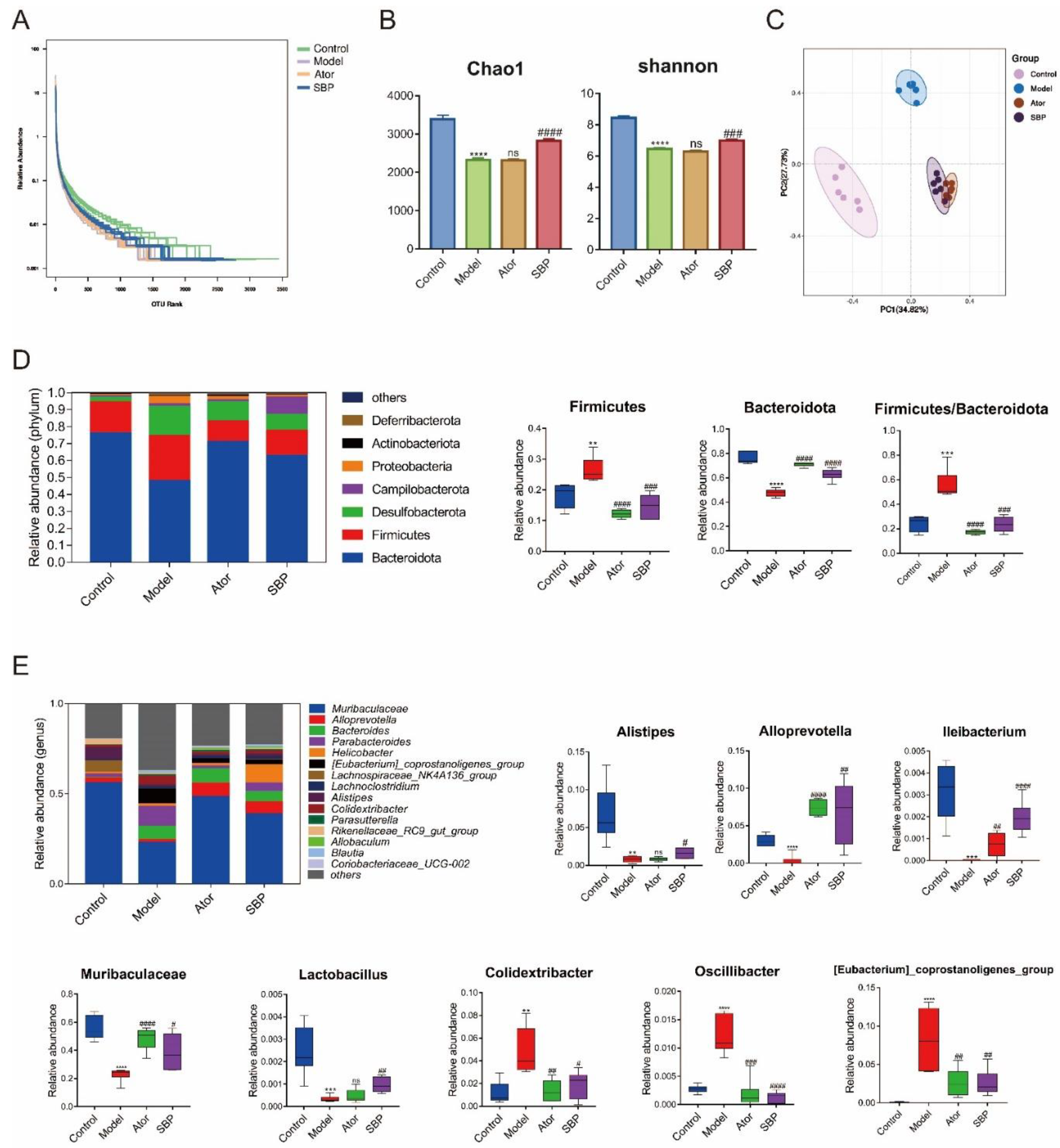

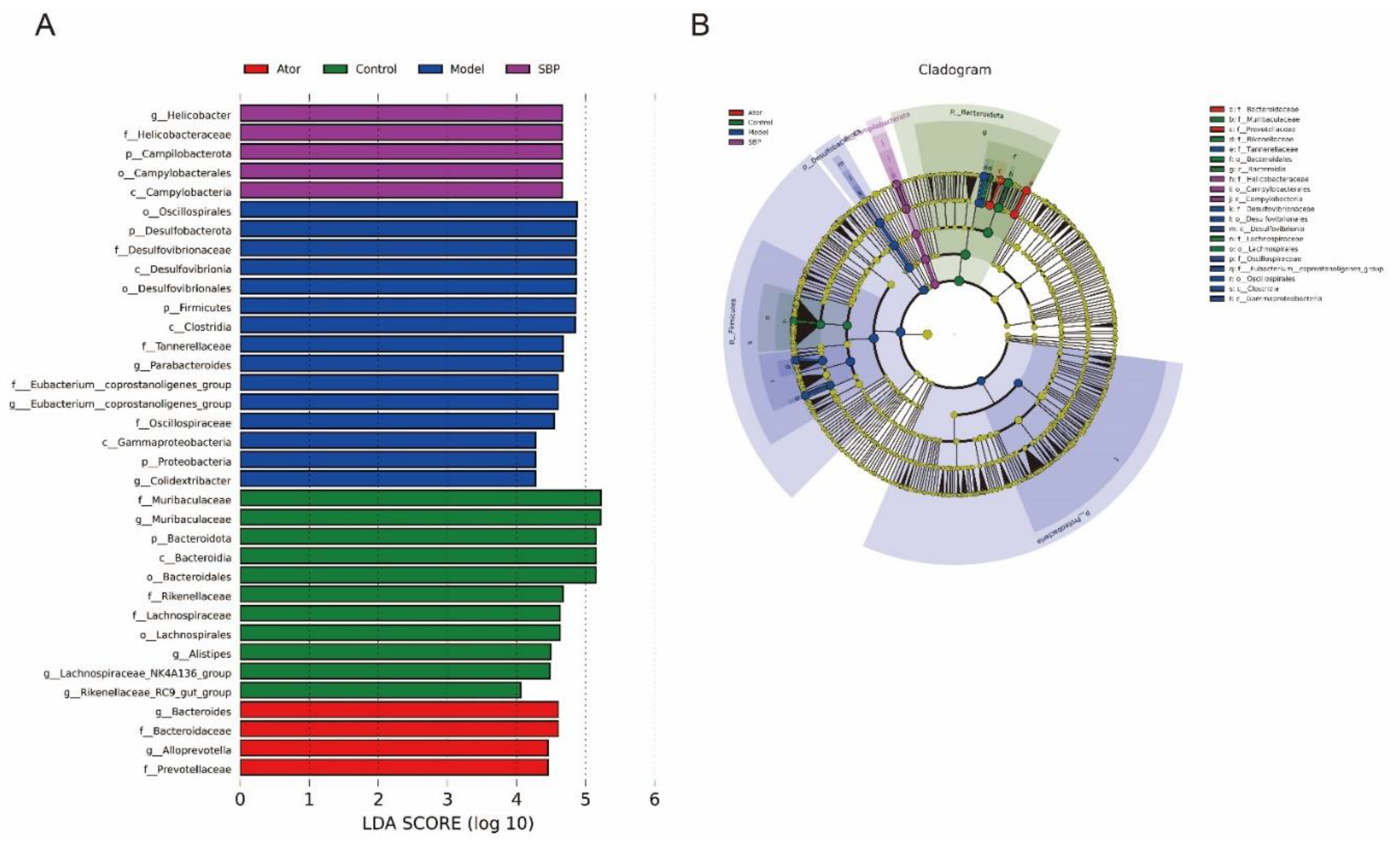

2.3. SBP Regulated Composition of Gut Microbiota in Apoe-/- Mice

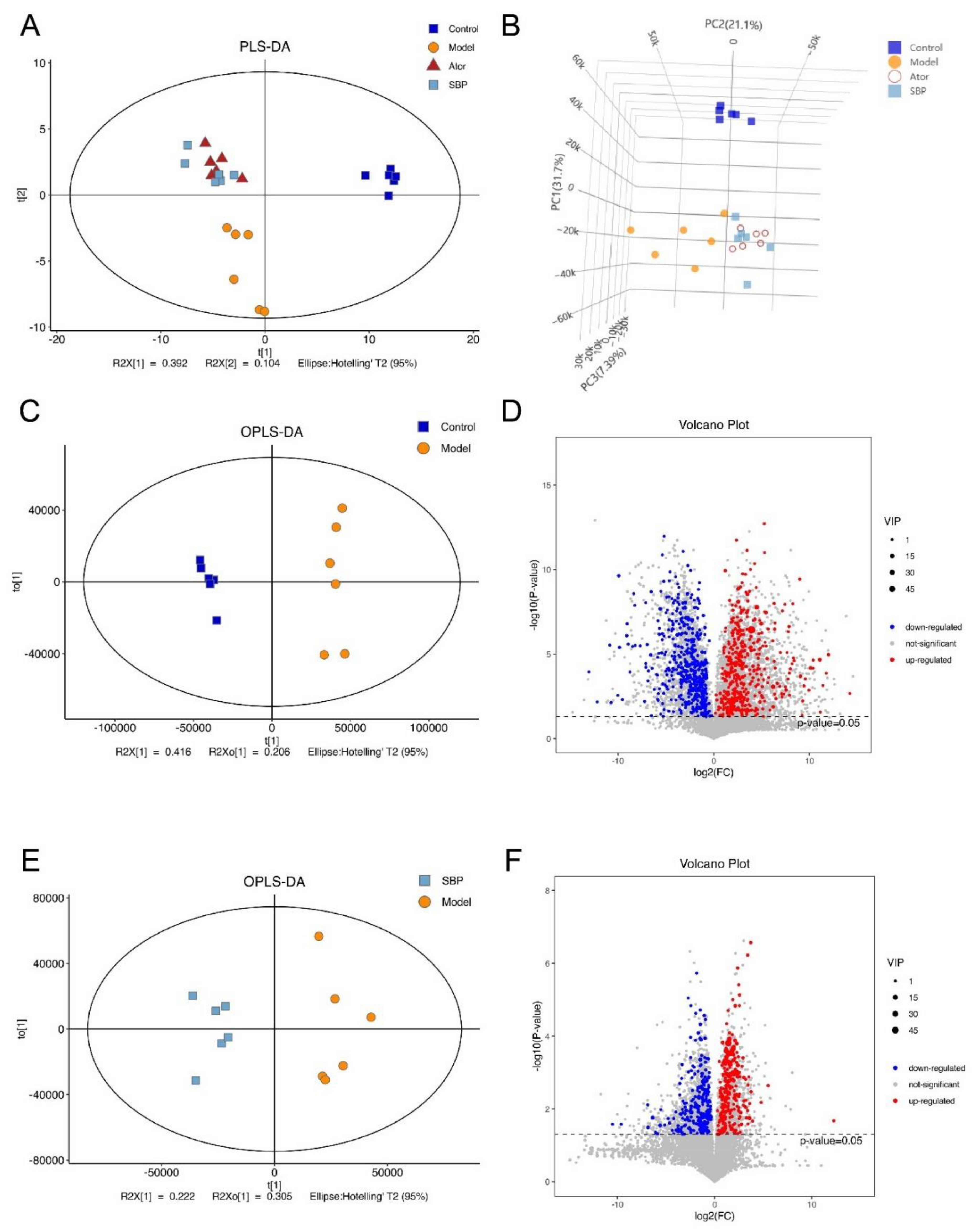

2.4. SBP Reshaped the Fecal Metabolic Profiles in Apoe-/- Mice

2.5. SBP Regulated the Metabolic Pathways Related to CVDs

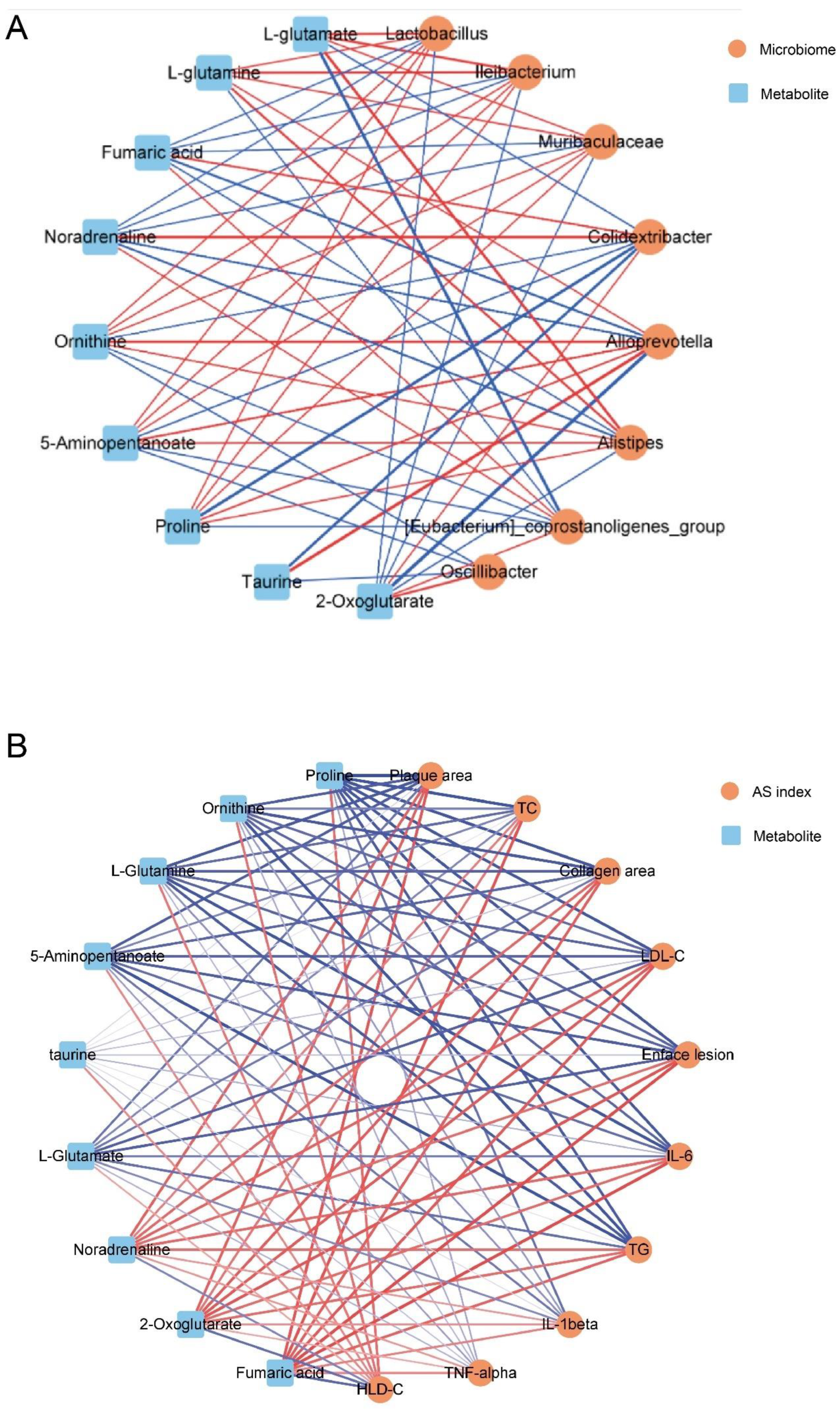

2.6. Correlation among Gut Microbes, Metabolites and AS

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

4.2. Animals and Treatment

4.3. Assessment of Atherosclerotic Lesions

4.4. Determination of Serum Cytokines

4.6. LC-MS-Based Untargeted Metabolomics Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Negre-Salvayre, A.; Guerby, P.; Gayral, S.; Laffargue, M.; Salvayre, R. Role of reactive oxygen species in atherosclerosis: Lessons from murine genetic models. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Boakye-Yiadom, K.O.; Yu, W.; Yuan, Z.W.; Ho, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.Q. Nanomedicine Approaches for Advanced Diagnosis and Treatment of Atherosclerosis and Related Ischemic Diseases. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, e2000336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salekeen, R.; Haider, A.N.; Akhter, F.; Billah, M.M.; Islam, M.E.; Didarul Islam, K.M. Lipid oxidation in pathophysiology of atherosclerosis: Current understanding and therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2022, 14, 200143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D. Human gut microbiome: Hopes, threats and promises. Gut 2018, 67, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer-Englar, T.; Barlow, G.; Mathur, R. Obesity, diabetes, and the gut microbiome: An updated review. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 13, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vourakis, M.; Mayer, G.; Rousseau, G. The Role of Gut Microbiota on Cholesterol Metabolism in Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, A.L.; Backhed, F. Role of gut microbiota in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaar, B.J.H.; Prodan, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Muller, M. Gut Microbiota in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fak, F.; Tremaroli, V.; Bergstrom, G.; Backhed, F. Oral microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2015, 243, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Q.; Yan, S.; Yang, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, T.; Ding, S. Gut Microbiome Alterations in Patients With Carotid Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 739093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, H. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Atherosclerosis and Hypertension. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.K.; Brar, M.S.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Li, D.; El-Nezami, H. High fat diet induced atherosclerosis is accompanied with low colonic bacterial diversity and altered abundances that correlates with plaque size, plasma A-FABP and cholesterol: A pilot study of high fat diet and its intervention with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) or telmisartan in ApoE(-/-) mice. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.K.; El-Nezami, H.; Chen, Y.; Kinnunen, K.; Kirjavainen, P.V. Probiotic mixture VSL#3 reduce high fat diet induced vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis in ApoE(-/-) mice. AMB Express 2016, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Morain, V.L.; Chan, Y.H.; Williams, J.O.; Alotibi, R.; Alahmadi, A.; Rodrigues, N.P.; Ramji, D.P. The Lab4P Consortium of Probiotics Attenuates Atherosclerosis in LDL Receptor Deficient Mice Fed a High Fat Diet and Causes Plaque Stabilization by Inhibiting Inflammation and Several Pro-Atherogenic Processes. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, P.; Jiang, F.; Cheng, J.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Traditional Chinese Medicine for Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence and Potential Mechanisms. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 2952–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Niimi, M.; Watanabe, T.; Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Fan, J. Treatment of atherosclerosis by traditional Chinese medicine: Questions and quandaries. Atherosclerosis 2018, 277, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Sun, X.; Chen, C.; Qin, Y.; Guo, X. Shexiang Baoxin Pill, Derived From the Traditional Chinese Medicine, Provides Protective Roles Against Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.K.; Zhang, W.D.; Liu, R.H.; Zhan, Y.C. Chemical fingerprinting of Shexiang Baoxin Pill and simultaneous determination of its major constituents by HPLC with evaporative light scattering detection and electrospray mass spectrometric detection. Chem Pharm Bull 2006, 54, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Liu, R.; Dou, S.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Ding, J. Analysis of the constituents in rat plasma after oral administration of Shexiang Baoxin pill by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2009, 23, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Han, L.; Huang, H.; Wen, B.; Peng, C.; Lv, C.; Liu, R. Simultaneous determination of four volatile compounds in rat plasma after oral administration of Shexiang Baoxin Pill (SBP) by HS-SPDE-GC-MS/MS and its application to pharmacokinetic studies. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2014, 963, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Peng, C.; Jiang, P.; Fu, P.; Tao, J.; Han, L.; Liu, R. Simultaneous determination of seven bufadienolides in rat plasma after oral administration of Shexiang Baoxin Pill by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry: Application to a pharmacokinetic study. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2014, 967, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Chen, L.; Fu, P.; Yang, N.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, R. Simultaneous quantification of 11 active constituents in Shexiang Baoxin Pill by ultraperformance convergence chromatography combined with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2017, 1052, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Qiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. Efficacy and Safety of Shexiang Baoxin Pill for Coronary Heart Disease after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021, 2021, 2672516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Qin, Z.; He, Q.; Fong, T.L.; Lau, N.C.; Cho, W.C.S.; Chen, H. Shexiang Baoxin Pill for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Clinical Evidence and Molecular Mechanism of Antioxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 7644648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.J.; Zhu, J.Z.; Bao, X.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zheng, G.Q.; Wang, Y. Shexiang Baoxin Pills for Coronary Heart Disease in Animal Models: Preclinical Evidence and Promoting Angiogenesis Mechanism. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Qiang, T.T.; Wang, K.Y.; Wang, X.L. Shexiang Baoxin Pill Regulates Intimal Hyperplasia, Migration, and Apoptosis after Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB-Stimulation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells via miR-451. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2022, 28, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Xu, X.; Yu, C.; Guo, X. Shexiang Baoxin Pill Alleviates the Atherosclerotic Lesions in Mice via Improving Inflammation Response and Inhibiting Lipid Accumulation in the Arterial Wall. Mediators Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 6710759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, C.; Agasthi, P.; Mookadam, F.; Arsanjani, R. Reversal of coronary atherosclerosis: Role of life style and medical management. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Qin, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Lv, C.; Guo, X. The atheroprotective roles of heart-protecting musk pills against atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookoian, S.; Pirola, C.J. Alanine and aspartate aminotransferase and glutamine-cycling pathway: Their roles in pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 3775–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Mottillo, E.P. Adipocyte lipolysis: From molecular mechanisms of regulation to disease and therapeutics. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 985–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaric, B.L.; Radovanovic, J.N.; Gluvic, Z.; Stewart, A.J.; Essack, M.; Motwalli, O.; Isenovic, E.R. Atherosclerosis Linked to Aberrant Amino Acid Metabolism and Immunosuppressive Amino Acid Catabolizing Enzymes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 551758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutson, A.K.; Williams, A.L.; Boisvert, W.A.; Shohet, R.V. HIF in the heart: Development, metabolism, ischemia, and atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 131, e137557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, E.E.; Clancy, C.E.; Lewis, T.J. Dynamics of adrenergic signaling in cardiac myocytes and implications for pharmacological treatment. J. Theor. Biol. 2021, 519, 110619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stary, H.C.; Chandler, A.B.; Dinsmore, R.E.; Fuster, V.; Glagov, S.; Insull, W., Jr.; Wissler, R.W. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation 1995, 92, 1355–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatana, C.; Saini, N.K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Saini, V.; Sharma, A.; Saini, R.V.; Saini, A.K. Mechanistic Insights into the Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein-Induced Atherosclerosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 5245308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, T.; Cesari, M.; Vergani, C. [Dislipidemia and lipid lowering drugs: From guidelines to clinical practice. An updated review of the literature. ]. Recenti Prog. Med. 2020, 111, 426–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Loscalzo, J.; Ridker, P.M.; Farkouh, M.E.; Hsue, P.Y.; Fuster, V.; Amar, S. Inflammation, Immunity, and Infection in Atherothrombosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andoh, A. Physiological Role of Gut Microbiota for Maintaining Human Health. Digestion 2016, 93, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Macias, I.; Orenes-Pinero, E.; Camelo-Castillo, A.; Rivera-Caravaca, J.M.; Lopez-Garcia, C.; Marin, F. Novel insights in the relationship of gut microbiota and coronary artery diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3738–3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menni, C.; Lin, C.; Cecelja, M.; Mangino, M.; Matey-Hernandez, M.L.; Keehn, L.; Valdes, A.M. Gut microbial diversity is associated with lower arterial stiffness in women. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 2390–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Park, H.; Choi, B.R.; Ji, Y.; Kwon, E.Y.; Choi, M.S. Alteration of Microbiome Profile by D-Allulose in Amelioration of High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, M.; Liang, H. Red yeast rice ameliorates high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis in Apoe(-/-) mice in association with improved inflammation and altered gut microbiota composition. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3880–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emoto, T.; Yamashita, T.; Sasaki, N.; Hirota, Y.; Hayashi, T.; So, A.; Hirata, K. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Coronary Artery Disease Patients: A Possible Link between Gut Microbiota and Coronary Artery Disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016, 23, 908–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, H.; Hernyes, A.; Piroska, M.; Ligeti, B.; Fussy, P.; Zoldi, L.; Tarnoki, D.L. Association between Gut Microbial Diversity and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness. Medicina 2021, 57, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Bao, M. Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 attenuates the atherosclerotic progression through modulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory process. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013, 17, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Quan, G.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhong, L. Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 prevents atherosclerosis via inhibition of intestinal cholesterol absorption in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 7496–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Duan, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, S. Lactobacillus plantarum NA136 improves the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating the AMPK/Nrf2 pathway. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5843–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hartigh, L.J.; Gao, Z.; Goodspeed, L.; Wang, S.; Das, A.K.; Burant, C.F.; Blaser, M.J. Obese Mice Losing Weight Due to trans-10,cis-12 Conjugated Linoleic Acid Supplementation or Food Restriction Harbor Distinct Gut Microbiota. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohue-Kitano, R.; Taira, S.; Watanabe, K.; Masujima, Y.; Kuboshima, T.; Miyamoto, J.; Kimura, I. 3-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propionic Acid Produced from 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic Acid by Gut Microbiota Improves Host Metabolic Condition in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, B.J.; Wearsch, P.A.; Veloo, A.C.M.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A. The Genus Alistipes: Gut Bacteria With Emerging Implications to Inflammation, Cancer, and Mental Health. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, C.; Gao, R.; Yan, X.; Huang, L.; Qin, H. Probiotics improve gut microbiota dysbiosis in obese mice fed a high-fat or high-sucrose diet. Nutrition 2019, 60, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.C.; Hoffmann, C.; Mota, J.F. The human gut microbiota: Metabolism and perspective in obesity. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.Y.; Ha, C.W.; Campbell, C.R.; Mitchell, A.J.; Dinudom, A.; Oscarsson, J.; Storlien, L.H. Increased gut permeability and microbiota change associate with mesenteric fat inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Guan, X.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, J.; Shen, M. Flavonoids from Whole-Grain Oat Alleviated High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia via Regulating Bile Acid Metabolism and Gut Microbiota in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7629–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, R.; Wan, F.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H. Olive Fruit Extracts Supplement Improve Antioxidant Capacity via Altering Colonic Microbiota Composition in Mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 645099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieczynska, M.D.; Yang, Y.; Petrykowski, S.; Horbanczuk, O.K.; Atanasov, A.G.; Horbanczuk, J.O. Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites in Atherosclerosis Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Wu, S.; Xu, G.; Wei, D. Essential Role of Nonessential Amino Acid Glutamine in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2020, 39, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, S.; Downs, K.; Short, J.D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Lai, Y.; Jerabek, P.A.; Asmis, R. Characterization of Macrophage Polarization States Using Combined Measurement of 2-Deoxyglucose and Glutamine Accumulation: Implications for Imaging of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatnik, M.; Thorpe, S.R.; Baynes, J.W. Succination of proteins by fumarate: Mechanism of inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1126, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Cardaci, S.; Jerby, L.; MacKenzie, E.D.; Sciacovelli, M.; Johnson, T.I.; Gottlieb, E. Fumarate induces redox-dependent senescence by modifying glutathione metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Ashwell, K.W.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. Innervation of the arterial wall and its modification in atherosclerosis. Auton. Neurosci. 2015, 193, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Z.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Ying, H.; Lv, Q.; Zhou, B. Proline improves cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction and attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via redox regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 114065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Pei, L.L.; Tian, M.; Liang, J.; Song, B. Changes of Metabolites in Acute Ischemic Stroke and Its Subtypes. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 580929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Khan, A.; Hong, S.; Jee, S.H.; Park, Y.H. A metabolomic study on high-risk stroke patients determines low levels of serum lysine metabolites: A retrospective cohort study. Mol. Biosyst. 2017, 13, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Medicine | Medicinal Materials | Bioactive Extracts |

|---|---|---|

| Shexiang Baoxin Pill | Cinnamomum cassia Presl | Cinnamaldehyde; Cinnamic acid |

| Liquidambar orientalis Mill | Benzyl benzoate | |

| Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl | Borneol; Isoborneol | |

| Panax ginseng C.A.Mey | Ginsenosides | |

| Bufo bufo gargarizans Cantor | Cinobufagin; Resibufogenin; Arenobufagin | |

| Moschus berezovskii Flerov | Muscone; Testosterone | |

| Bos taurus domesticus Gmelin | Cholic acid; Deoxycholic acid |

| NO. | KEGG pathway | Model/Control | SBP/Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rich Factor | p value | Rich Factor | p value | |||

| 1 | Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism | 0.1786 | 0.003646 | 0.1786 | 0.000352 | |

| 2 | Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes | 0.2143 | 0.014570 | 0.2143 | 0.003462 | |

| 3 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 0.2000 | 0.017712 | 0.2000 | 0.004257 | |

| 4 | Taurine and hypotaurine metabolism | 0.1364 | 0.049406 | 0.1364 | 0.004969 | |

| 5 | Adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes | 0.3000 | 0.005372 | 0.2000 | 0.020522 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).