Submitted:

08 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

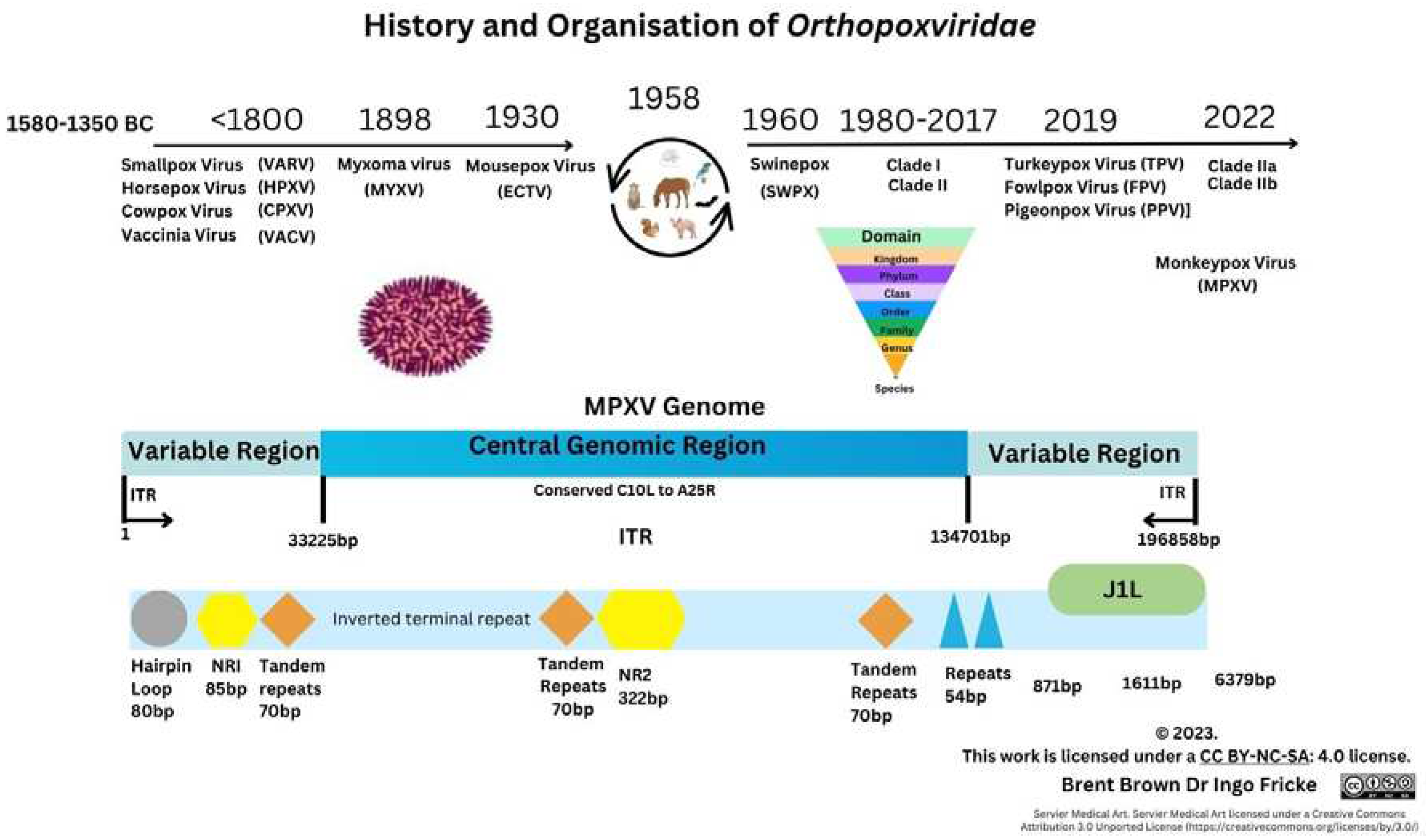

Historical and Epidemiology Overview of Monkeypox Virus

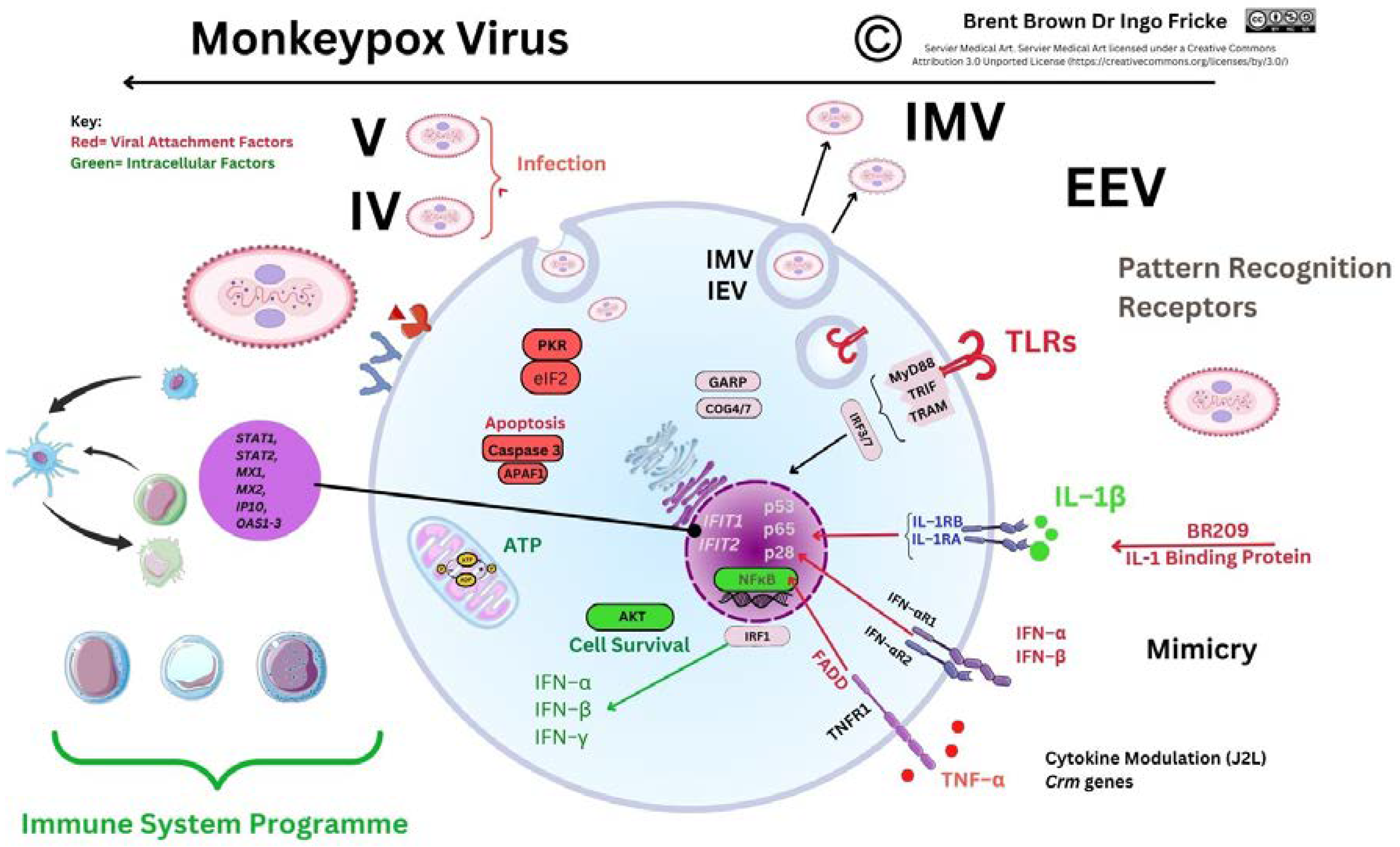

Pathogenesis

Clinical manifestations and Diagnosis

3.2. Cellular Monkeypox and Orthopoxvirus Historical Evolution on Viral Entry

Differences between Smallpox and Monkeypox virus

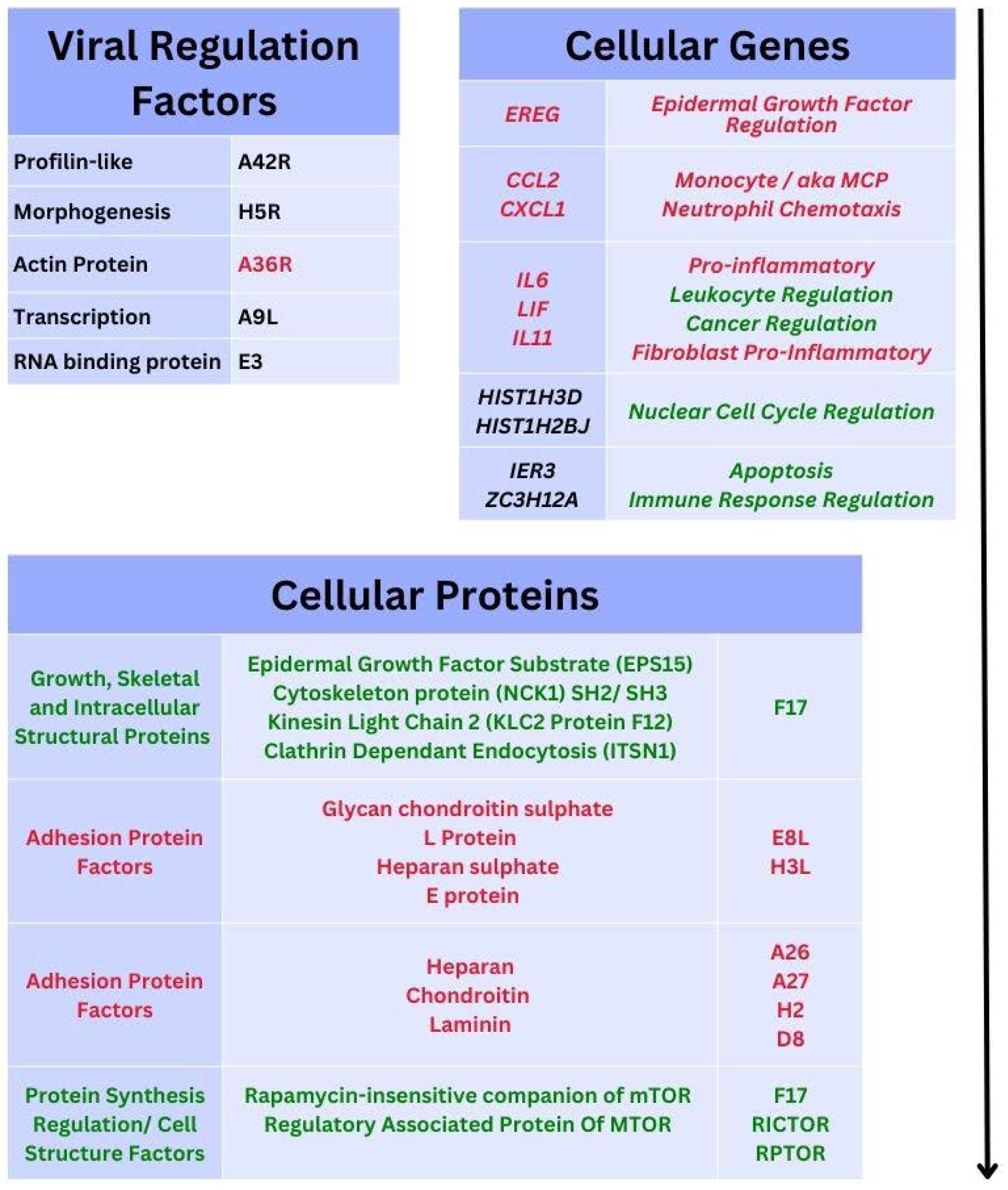

Gene Transcripts and Proteins during Monkeypox virus Infection

3.5. Recent Monkeypox Virus Protein Characterisation and Research

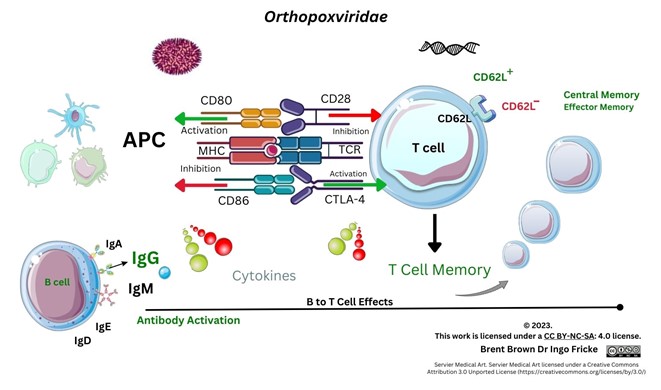

Orthopoxvirus and Monkeypox Virus 21st Century Immunological Research

Background

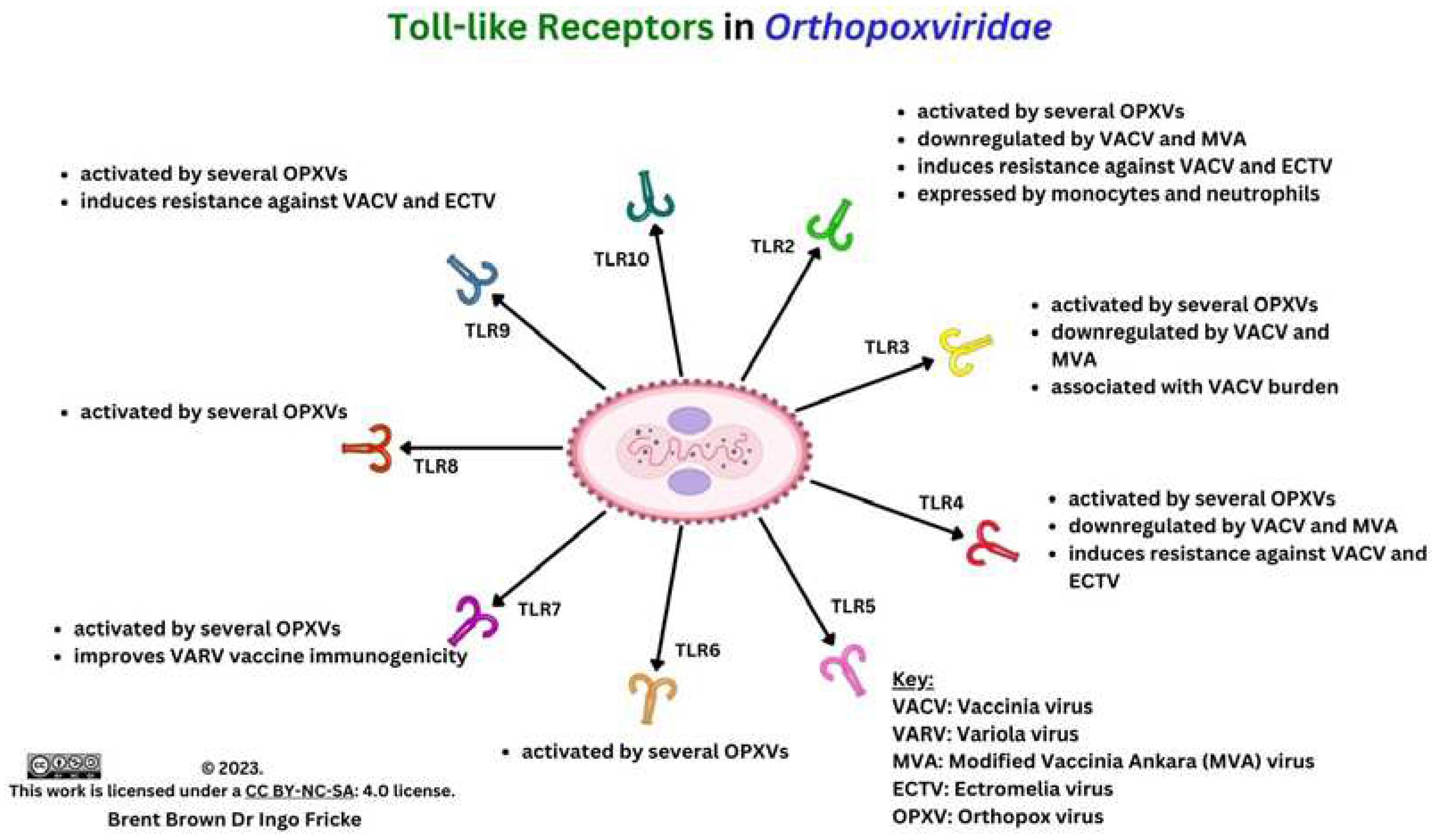

Immunological Response during OPXV Infection

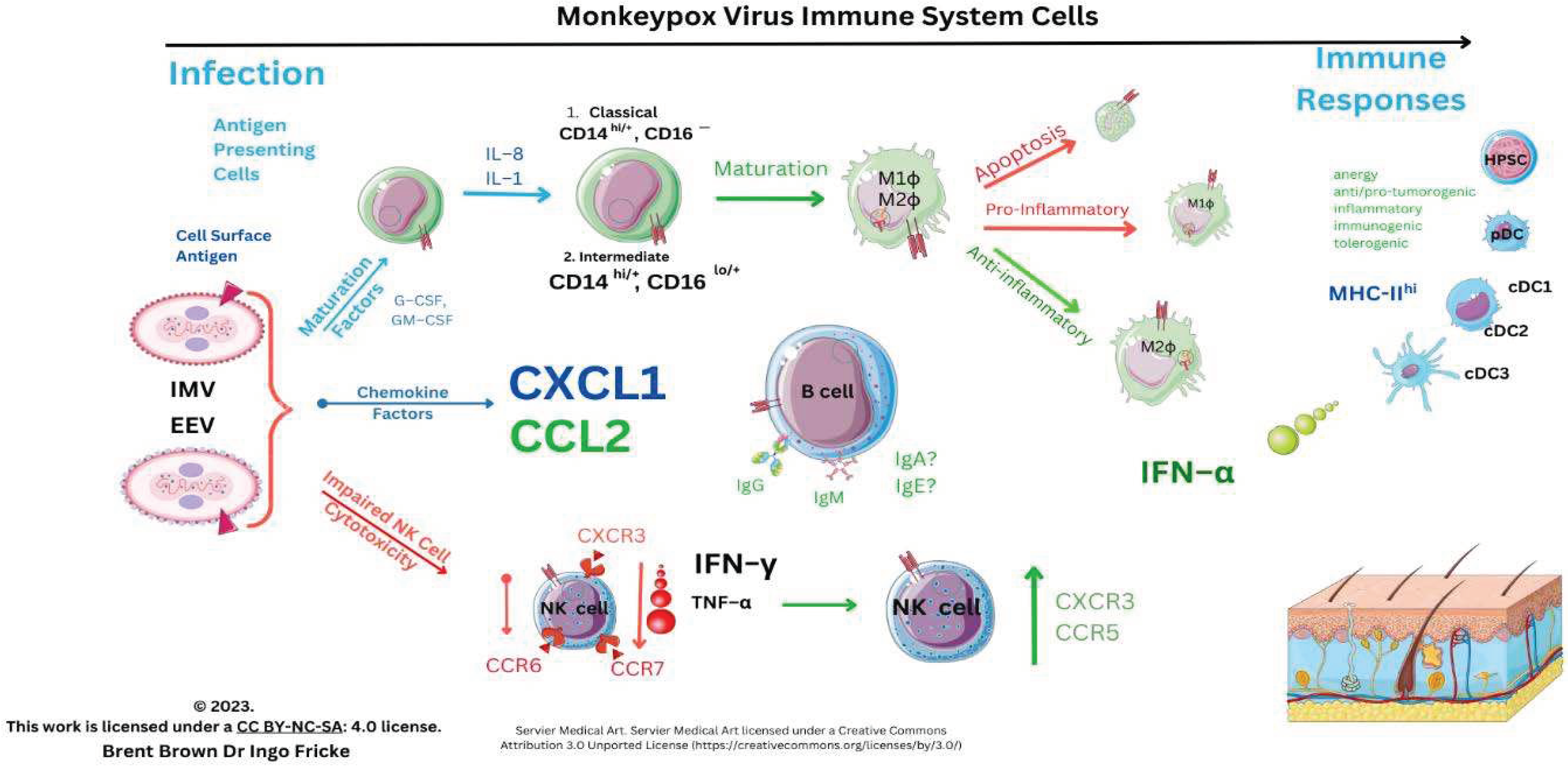

Immunological Responses to Monkeypox Virus and Orthopoxviruses

Background to Vaccinia and Orthopoxvirus Role in Cellular Research

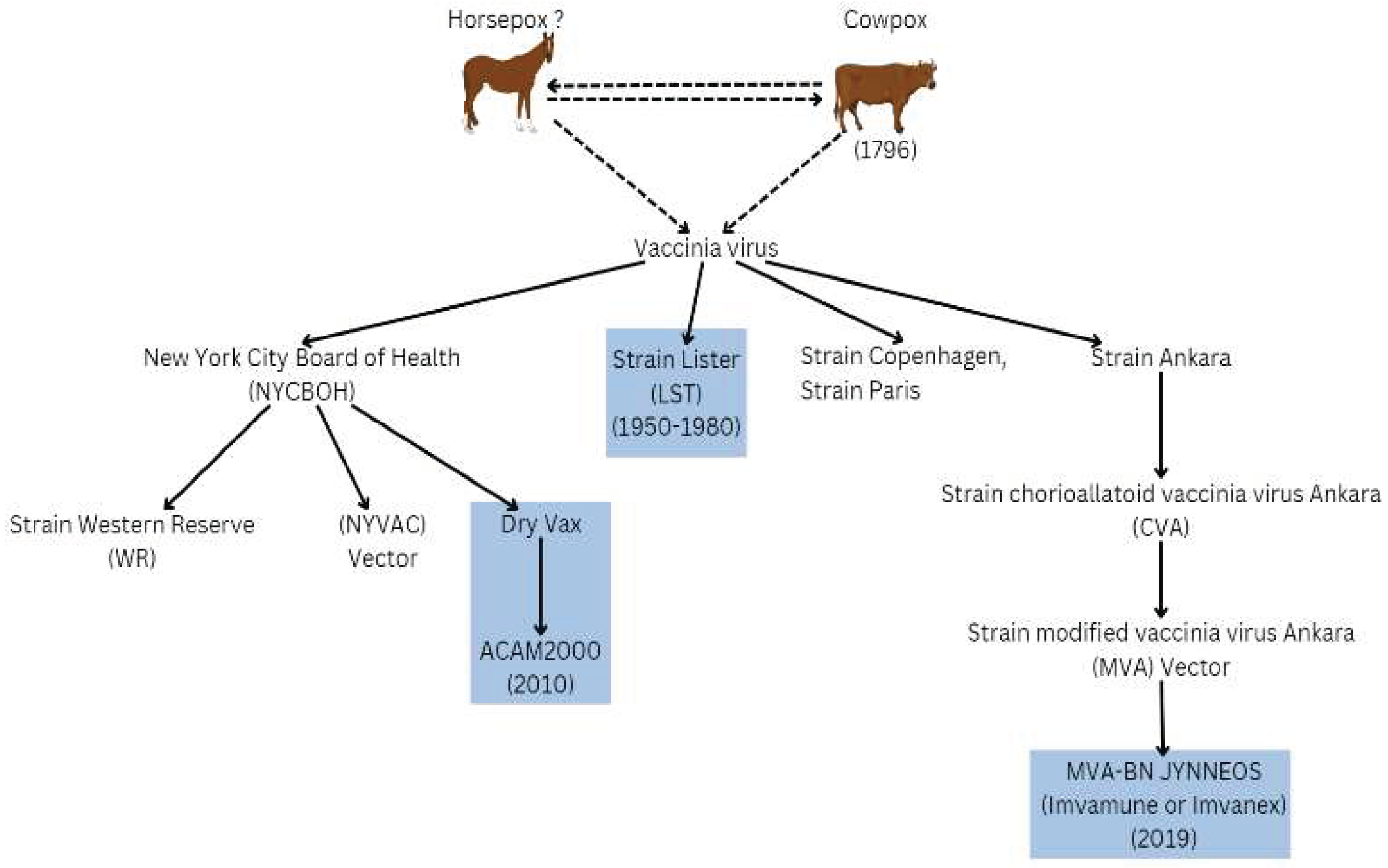

Background to Therapeutics, Prevention and Therapy

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Disclaimer

Publication Ethics

List of Abbreviations

References

- Nuzzo, J.B.; Borio, L.L.; Gostin, L.O. The WHO Declaration of Monkeypox as a Global Public Health Emergency. JAMA 2022, 328(7), 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrick, L.; Tausch, S.H.; Dabrowski, P.W.; Damaso, C.R.; Esparza, J.; Nitsche, A. An Early American Smallpox Vaccine Based on Horsepox. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377(15), 1491–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; King, A.M.Q.; Harrach, B.; Harrison, R.L.; Knowles, N.J.; Kropinski, A.M.; Krupovic, M.; Kuhn, J.H.; Mushegian, A.R.; et al. Ratification Vote on Taxonomic Proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2016). Arch Virol 2016, 161(10), 2921–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.T.; Wenner, H.A. Monkeypox Virus. Bacteriol Rev 1973, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessain, A.; Nakoune, E.; Yazdanpanah, Y. Monkeypox. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 387(19), 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, E.M.; Rao, V.B. A Systematic Review of the Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox Outbreaks and Implications for Outbreak Strategy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13(10), e0007791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereewit, J.; Lieberman, N.A.P.; Xie, H.; Bakhash, S.A.K.M.; Nunley, B.E.; Chung, B.; Mills, M.G.; Roychoudhury, P.; Greninger, A.L. ORF—Interrupting Mutations in Monkeypox Virus Genomes from Washington and Ohio, 2022. Viruses 2022, 14(11), 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov, S.N.; Totmenin, A.V.; Safronov, P.F.; Mikheev, M.V.; Gutorov, V.V.; Ryazankina, O.I.; Petrov, N.A.; Babkin, I.V.; Uvarova, E.A.; Sandakhchiev, L.S.; et al. Analysis of the Monkeypox Virus Genome. Virology 2002, 297(2), 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Americo, J.L.; Earl, P.L.; Moss, B. Virulence Differences of Monkeypox Virus Clades 1, 2a and 2b. 1 in a Small Animal Model. 2022, bioRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, S.D.; Lester, R.; Devine, K.; Warrell, C.E.; Groves, N.; Beadsworth, M.B.J. Clade IIb A.3 Monkeypox Virus: An Imported Lineage during a Large Global Outbreak. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23(4), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, F.-M.; Torres-Ruesta, A.; Tay, M.Z.; Lin, R.T.P.; Lye, D.C.; Rénia, L.; Ng, L.F.P. Monkeypox: Disease Epidemiology, Host Immunity and Clinical Interventions. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22(10), 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.L.; Langland, J.O.; Kibler, K. v.; Denzler, K.L.; White, S.D.; Holechek, S.A.; Wong, S.; Huynh, T.; Baskin, C.R. Vaccinia Virus Vaccines: Past, Present and Future. Antiviral Res 2009, 84(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knöpfel, N.; Noguera-Morel, L.; Latour, I.; Torrelo, A. Viral Exanthems in Children: A Great Imitator. Clin Dermatol 2019, 37(3), 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel AB, Pacha O. Skin Reactions to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017, 995, 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Gasparini G, et al. Contemporary infectious exanthems: an update. Future Microbiol. 2017, 12, 171–193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soman, L. Fever with Rashes. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 85(7), 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Acharya, A.; Gendelman, H.E.; Byrareddy, S.N. The 2022 Outbreak and the Pathobiology of the Monkeypox Virus. J Autoimmun 2022, 131, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, T.-Y.; Hsieh, Z.-Y.; Feehley, M.C.; Feehley, P.J.; Contreras, G.P.; Su, Y.-C.; Hsieh, S.-L.; Lewis, D.A. Recombination Shapes the 2022 Monkeypox (Mpox) Outbreak. Med 2022, 3(12), 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov, S.N. Emergence and Reemergence of Smallpox: The Need for Development of a New Generation Smallpox Vaccine. Vaccine 2011, 29, D49–D53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, C.; Kitchen, A.; Shapiro, B.; Suchard, M.A.; Holmes, E.C.; Rambaut, A. Using Time—Structured Data to Estimate Evolutionary Rates of Double—Stranded DNA Viruses. Mol Biol Evol 2010, 27(9), 2038–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, P.J.; Ghedin, E.; DePasse, J. V.; Fitch, A.; Cattadori, I.M.; Hudson, P.J.; Tscharke, D.C.; Read, A.F.; Holmes, E.C. Evolutionary History and Attenuation of Myxoma Virus on Two Continents. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8(10), e1002950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakunle, E.; Moens, U.; Nchinda, G.; Okeke, M.I. Monkeypox Virus in Nigeria: Infection Biology, Epidemiology, and Evolution. Viruses 2020, 12(11), 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodakevich L, Jezek Z, Kinzanzka K. Isolation of monkeypox virus from wild squirrel infected in nature. Lancet 1986, 1(8472), 98–99. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.G.; Yorita, K.L.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Davidson, W.B.; Huhn, G.D.; Holman, R.C.; Damon, I.K. Clinical Manifestations of Human Monkeypox Influenced by Route of Infection. J Infect Dis 2006, 194(6), 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.; Buller, R.M. A Review of Experimental and Natural Infections of Animals with Monkeypox Virus between 1958 and 2012. Future Virol 2013, 8(2), 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, S.-L.; Nakazawa, Y.; Gao, J.; Wilkins, K.; Gallardo-Romero, N.; Li, Y.; Emerson, G.L.; Carroll, D.S.; Upton, C. Characterization of Eptesipoxvirus, a Novel Poxvirus from a Microchiropteran Bat. Virus Genes 2017, 53, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gray, M.; Winter, L. Why Do Poxviruses Still Matter? Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 96–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.G.; Guagliardo, S.A.J.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Doty, J.B.; Mauldin, M.R. Understanding Orthopoxvirus Host Range and Evolution: From the Enigmatic to the Usual Suspects. Curr Opin Virol 2018, 28, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen JM, Bamford A, Eisen S, et al. Comment Title: Care of children exposed to monkeypox. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022, 21, 100514. [CrossRef]

- Kisalu, N.K.; Mokili, J.L. Toward Understanding the Outcomes of Monkeypox Infection in Human Pregnancy. J Infect Dis 2017, 216(7), 795–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbala, P.K.; Huggins, J.W.; Riu-Rovira, T.; Ahuka, S.M.; Mulembakani, P.; Rimoin, A.W.; Martin, J.W.; Muyembe, J.-J.T. Maternal and Fetal Outcomes Among Pregnant Women With Human Monkeypox Infection in the Democratic Republic of Congo. J Infect Dis 2017, 216(7), 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’toole, Á.; Neher, R.A.; Ndodo, N.; Borges, V.; Gannon, B.; Gomes, J.P.; Groves, N.; King, D.J.; Maloney, D.; Lemey, P.; et al. Putative APOBEC3 Deaminase Editing in MPXV as Evidence for Sustained Human Transmission since at Least 2016. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milewska, A.; Kindler, E.; Vkovski, P.; Zeglen, S.; Ochman, M.; Thiel, V.; Rajfur, Z.; Pyrc, K. APOBEC3—Mediated Restriction of RNA Virus Replication. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, R.; Mohanty, A.; Abdelaal, A.; Reda, A.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; Henao-Martinez, A.F. First Monkeypox Deaths Outside Africa: No Room for Complacency. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2022, 9, 20499361221124027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomori, O.; Ogoina, D. Monkeypox: The Consequences of Neglecting a Disease, Anywhere. Science (1979) 2022, 377(6612), 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Shao, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L.; Herrera-Diestra, J.L.; Fox, S.J.; Ertem, Z.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Cowling, B.J. Reproduction Number of Monkeypox in the Early Stage of the 2022 Multi—Country Outbreak. J Travel Med 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Ding, K.; Wang, X.-H.; Sun, G.-Y.; Liu, Z.-X.; Luo, Y. The Evolving Epidemiology of Monkeypox Virus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2022, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, P.L.; Street, E.J.; Leslie, T.F.; Yang, Y.T.; Jacobsen, K.H. Complexity of the Basic Reproduction Number (R0). Emerg Infect Dis 2019, 25(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.; Koopmans, M.; Go, U.; Hamer, D.H.; Petrosillo, N.; Castelli, F.; Storgaard, M.; al Khalili, S.; Simonsen, L. Comparing SARS—CoV—2 with SARS—CoV and Influenza Pandemics. Lancet Infect Dis 2020, 20(9), e238–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, N.H.L. Transmissibility and Transmission of Respiratory Viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19(8), 528–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.M.; Bolotin, S.; Lim, G.; Heffernan, J.; Deeks, S.L.; Li, Y.; Crowcroft, N.S. The Basic Reproduction Number (R 0 ) of Measles: A Systematic Review. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17(12), e420–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoin, A.W.; Mulembakani, P.M.; Johnston, S.C.; Lloyd Smith, J.O.; Kisalu, N.K.; Kinkela, T.L.; Blumberg, S.; Thomassen, H.A.; Pike, B.L.; Fair, J.N.; et al. Major Increase in Human Monkeypox Incidence 30 Years after Smallpox Vaccination Campaigns Cease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107(37), 16262–16267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, F.V.S. de; Lorene Soares Rocha, K.; Silva-Oliveira, R.; Macedo, M.V.; Silva, T.G.M.; Gonçalves-dos-Santos, M.E.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Aquino-Teixeira, S.M.; Ottone, V. de O.; da Silva, A.J.J.; et al. Serological Evidence of Orthopoxvirus Infection in Neotropical Primates in Brazil. Pathogens 2022, 11(10), 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, T.Y.; Townsend, M.B.; Pohl, J.; Karem, K.L.; Damon, I.K.; Mbala Kingebeni, P.; Muyembe Tamfum, J.-J.; Martin, J.W.; Pittman, P.R.; Huggins, J.W.; et al. Design and Optimization of a Monkeypox Virus Specific Serological Assay. Pathogens 2023, 12(3), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karem, K.L.; Reynolds, M.; Braden, Z.; Lou, G.; Bernard, N.; Patton, J.; Damon, I.K. Characterization of Acute—Phase Humoral Immunity to Monkeypox: Use of Immunoglobulin M Enzyme—Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Detection of Monkeypox Infection during the 2003 North American Outbreak. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2005, 12(7), 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.J.; Goldstein, J.; Pohl, J.; Hooper, J.W.; Lee Pitts, R.; Townsend, M.B.; Bagarozzi, D.; Damon, I.K.; Karem, K.L. A Highly Specific Monoclonal Antibody against Monkeypox Virus Detects the Heparin Binding Domain of A27. Virology 2014, 464–465, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prkno, A.; Hoffmann, D.; Goerigk, D.; Kaiser, M.; van Maanen, A.; Jeske, K.; Jenckel, M.; Pfaff, F.; Vahlenkamp, T.; Beer, M.; et al. Epidemiological Investigations of Four Cowpox Virus Outbreaks in Alpaca Herds, Germany. Viruses 2017, 9(11), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, A.; Pfaff, F.; Jenckel, M.; Hoffmann, B.; Höper, D.; Antwerpen, M.; Meyer, H.; Beer, M.; Hoffmann, D. Classification of Cowpox Viruses into Several Distinct Clades and Identification of a Novel Lineage. Viruses 2017, 9(6), 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, B.; Burton, C.; Pottage, T.; Thompson, K.; Ngabo, D.; Crook, A.; Pitman, J.; Summers, S.; Lewandowski, K.; Furneaux, J.; et al. Infection-competent Monkeypox Virus Contamination Identified in Domestic Settings Following an Imported Case of Monkeypox into the UK. Environ Microbiol 2022, 24(10), 4561–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.N.; Whitehill, F.; Doty, J.B.; Schulte, J.; Matheny, A.; Stringer, J.; Delaney, L.J.; Esparza, R.; Rao, A.K.; McCollum, A.M. Environmental Persistence of Monkeypox Virus on Surfaces in Household of Person with Travel—Associated Infection, Dallas, Texas, USA, 2021. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28(10), 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nörz, D.; Pfefferle, S.; Brehm, T.T.; Franke, G.; Grewe, I.; Knobling, B.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Huber, S.; Klupp, E.M.; Jordan, S.; et al. Evidence of Surface Contamination in Hospital Rooms Occupied by Patients Infected with Monkeypox, Germany, June 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27(26), 2200477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, A.; Aarons, E.; Astbury, J.; Brooks, T.; Chand, M.; Flegg, P.; Hardman, A.; Harper, N.; Jarvis, R.; Mawdsley, S.; et al. Human—to—Human Transmission of Monkeypox Virus, United Kingdom, October 2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26(4), 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, S.; Atkinson, B.; Onianwa, O.; Spencer, A.; Furneaux, J.; Grieves, J.; Taylor, C.; Milligan, I.; Bennett, A.; Fletcher, T.; et al. Air and Surface Sampling for Monkeypox Virus in a UK Hospital: An Observational Study. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3(12), e904–e911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrea M. McCollum, Inger K. Damon, Human Monkeypox. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2014, 58(2), 260–267. [CrossRef]

- Xu YS, Jiang MY, Cao YL, et al. Research progress on the effectiveness of smallpox vaccination against mpox virus infection. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2023, 44(4), 673–676. [CrossRef]

- Bryer, J.; Freeman, E.E.; Rosenbach, M. Monkeypox Emerges on a Global Scale: A Historical Review and Dermatologic Primer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2022, 87(5), 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titanji, B.K.; Tegomoh, B.; Nematollahi, S.; Konomos, M.; Kulkarni, P.A. Monkeypox: A Contemporary Review for Healthcare Professionals. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022, 9(7), ofac310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariou, M. Monkeypox: Symptoms Seen in London Sexual Health Clinics Differ from Previous Outbreaks, Study Finds. BMJ 2022, 378, o1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yuan, W.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Ultrasensitive and Specific Identification of Monkeypox Virus Congo Basin and West African Strains Using a CRISPR/Cas12b—Based Platform. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11(2), e0403522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Song, X.; Fredj, Z.; Bian, S.; Sawan, M. Challenges and Perspectives of Multi—Virus Biosensing Techniques: A Review. Anal Chim Acta 2023, 1244, 340860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.; Zuo, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, J. CRISPR—Cas12a—Based Detection of Monkeypox Virus. Journal of Infection 2022, 85(6), 702–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, D.A.; Wang, J.Y.; Moeser, M.-E.; Starkey, T.; Lee, L.Y.W. A Systematic Review of the Sensitivity and Specificity of Lateral Flow Devices in the Detection of SARS—CoV—2. BMC Infect Dis 2021, 21(1), 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.; Shin, H.Y. Advanced CRISPR—Cas Effector Enzyme—Based Diagnostics for Infectious Diseases, Including COVID—19. Life 2021, 11(12), 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colavita, F.; Mazzotta, V.; Rozera, G.; Abbate, I.; Carletti, F.; Pinnetti, C.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; Mondi, A.; Lapa, D.; et al. Kinetics of Viral DNA in Body Fluids and Antibody Response in Patients with Acute Monkeypox Virus Infection. iScience 2023, 26(3), 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Olson, V.A.; Laue, T.; Laker, M.T.; Damon, I.K. Detection of Monkeypox Virus with Real—Time PCR Assays. Journal of Clinical Virology 2006, 36(3), 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchelkunov, S.N.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Gavrilova, E. v. Species—Specific Identification of Variola, Monkeypox, Cowpox, and Vaccinia Viruses by Multiplex Real—Time PCR Assay. J Virol Methods 2011, 175(2), 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró-Mestres, A.; Fuertes, I.; Camprubí-Ferrer, D.; Marcos, M.Á.; Vilella, A.; Navarro, M.; Rodriguez-Elena, L.; Riera, J.; Català, A.; Martínez, M.J.; et al. Frequent Detection of Monkeypox Virus DNA in Saliva, Semen, and Other Clinical Samples from 12 Patients, Barcelona, Spain, May to June 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27(28). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orba, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ishii, A.; Thomas, Y.; Ogawa, H.; Hang’ombe, B.M.; Mweene, A.S.; Morikawa, S.; Saijo, M.; et al. Orthopoxvirus Infection among Wildlife in Zambia. Journal of General Virology 2015, 96(Pt 2) Pt 2, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davi, S.D.; Kissenkötter, J.; Faye, M.; Böhlken-Fascher, S.; Stahl-Hennig, C.; Faye, O.; Faye, O.; Sall, A.A.; Weidmann, M.; Ademowo, O.G.; et al. Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Assay for Rapid Detection of Monkeypox Virus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 95(1), 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasov, G.; Inniss, N.L.; Shuvalova, L.; Anderson, W.F.; Satchell, K.J.F. Structure of the Monkeypox Virus Profilin—like Protein A42R Reveals Potential Functional Differences from Cellular Profilins. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2022, 78(Pt 10) Pt 10, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murk, K.; Ornaghi, M.; Schiweck, J. Profilin Isoforms in Health and Disease – All the Same but Different. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowie, A.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Symons, J.A.; Smith, G.L.; Dower, S.K.; O’Neill, L.A.J. A46R and A52R from Vaccinia Virus Are Antagonists of Host IL—1 and Toll—like Receptor Signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97(18), 10162–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot-Cooper, C.; Pantelejevs, T.; Shannon, J.P.; Cherry, C.R.; Au, M.T.; Hyvönen, M.; Hickman, H.D.; Smith, G.L. Poxviruses and Paramyxoviruses Use a Conserved Mechanism of STAT1 Antagonism to Inhibit Interferon Signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30(3), 357–372.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubins, K.H.; Hensley, L.E.; Relman, D.A.; Brown, P.O. Stunned Silence: Gene Expression Programs in Human Cells Infected with Monkeypox or Vaccinia Virus. PLoS One 2011, 6(1), e15615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, R.R.; Kotenko, S. V.; Kaplan, M.J. Interferon Lambda in Inflammation and Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021, 17(6), 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.N.; Gan, Z.; Hou, J.; Yang, Y.C.; Huang, L.; Huang, B.; Wang, S.; Nie, P. Identification and Establishment of Type IV Interferon and the Characterization of Interferon—υ Including Its Class II Cytokine Receptors IFN— υ R1 and IL—10R2. Nat Commun 2022, 13(1), 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus Cell Entry: How Many Proteins Does It Take? Viruses 2012, 4(5), 688–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B. Membrane Fusion during Poxvirus Entry. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2016, 60, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schin, A.M.; Diesterbeck, U.S.; Moss, B. Insights into the Organization of the Poxvirus Multicomponent Entry—Fusion Complex from Proximity Analyses in Living Infected Cells. J Virol 2021, 95(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaler, J.; Hussain, A.; Flores, G.; Kheiri, S.; Desrosiers, D. Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathogenesis, and Manifestation. Cureus 2022, 14(17), e26531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong Q, Wang C, Chuai X, Chiu S. Monkeypox virus: a re—emergent threat to humans. Virol Sin. 2022, 37(4), 477–482. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senkevich TG, Ojeda S, Townsley A, Nelson GE, Moss B. Poxvirus multiprotein entry—fusion complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102(51), 18572–18577. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Mu, L.; Wang, W. Monkeypox: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7(1), 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, R.C.; Wang, C.; Hatcher, E.L.; Lefkowitz, E.J. Orthopoxvirus Genome Evolution: The Role of Gene Loss. Viruses 2010, 2(9), 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, J.R.; Isaacs, S.N. Monkeypox Virus and Insights into Its Immunomodulatory Proteins. Immunol Rev 2008, 225, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Chi-Long et al. Vaccinia Virus Envelope H3L Protein Binds to Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate and Is Important for Intracellular Mature Virion Morphogenesis and Virus Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. J Virol 2000, 74(7), 3353–3365. [CrossRef]

- Kaever, T.; Matho, M.H.; Meng, X.; Crickard, L.; Schlossman, A.; Xiang, Y.; Crotty, S.; Peters, B.; Zajonc, D.M. Linear Epitopes in Vaccinia Virus A27 Are Targets of Protective Antibodies Induced by Vaccination against Smallpox. J Virol 2016, 90(9), 4334–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, R.D.; Messaoudi, I.; O’Connor, M.A.; Li, H.; Sprague, J.; Barron, A.; Engelmann, F.; Yen, B.; Powers, M.F.; Jones, J.M.; et al. Deletion of the Monkeypox Virus Inhibitor of Complement Enzymes Locus Impacts the Adaptive Immune Response to Monkeypox Virus in a Nonhuman Primate Model of Infection. J Virol 2011, 85(18), 9527–9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, W.D.; Cotsmire, S.; Trainor, K.; Harrington, H.; Hauns, K.; Kibler, K. v.; Huynh, T.P.; Jacobs, B.L. Evasion of the Innate Immune Type I Interferon System by Monkeypox Virus. J Virol 2015, 89(20), 10489–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehwinkel, J.; Gack, M.U. RIG—I—like Receptors: Their Regulation and Roles in RNA Sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20(9), 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown E, Senkevich TG, Moss B. Vaccinia virus F9 virion membrane protein is required for entry but not virus assembly, in contrast to the related L1 protein. J Virol. 2006, 80(19), 9455–9464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, B. Poxvirus DNA Replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubins, K.H.; Hensley, L.E.; Bell, G.W.; Wang, C.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Brown, P.O.; Relman, D.A. Comparative Analysis of Viral Gene Expression Programs during Poxvirus Infection: A Transcriptional Map of the Vaccinia and Monkeypox Genomes. PLoS One 2008, 3(7), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampogu, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Lee, K.W. An Overview on Monkeypox Virus: Pathogenesis, Transmission, Host Interaction and Therapeutics. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1076251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realegeno, S.; Priyamvada, L.; Kumar, A.; Blackburn, J.B.; Hartloge, C.; Puschnik, A.S.; Sambhara, S.; Olson, V.A.; Carette, J.E.; Lupashin, V.; et al. Conserved Oligomeric Golgi (COG) Complex Proteins Facilitate Orthopoxvirus Entry, Fusion and Spread. Viruses 2020, 12(7), 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maluquer de Motes, C. Poxvirus cGAMP Nucleases: Clues and Mysteries from a Stolen Gene. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17(3), e1009372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaglesham, J.B.; Pan, Y.; Kupper, T.S.; Kranzusch, P.J. Viral and Metazoan Poxins Are CGAMP—Specific Nucleases That Restrict CGAS–STING Signalling. Nature 2019, 566(7743), 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realegeno, S.; Puschnik, A.S.; Kumar, A.; Goldsmith, C.; Burgado, J.; Sambhara, S.; Olson, V.A.; Carroll, D.; Damon, I.; Hirata, T.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Host Factor Screen Using Haploid Cells Identifies Essential Role of GARP Complex in Extracellular Virus Formation. J Virol 2017, 91(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Huang, H.; Duan, Y.; Luo, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, T.; Nguyen, H.C.; Shen, W.; Su, D.; Li, X.; et al. Crystal Structure of Monkeypox H1 Phosphatase, an Antiviral Drug Target. Protein Cell 2022, pwac051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Standley, D.M.; Kumagai, Y.; Kawagoe, T.; Miyake, T.; Satoh, T.; Kato, H.; Tsujimura, T.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Zc3h12a Is an RNase Essential for Controlling Immune Responses by Regulating MRNA Decay. Nature 2009, 45(7242), 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Meng, Y.; Qiu, X.; Bajinka, O.; Wu, G.; Tan, Y.; Guojun, W. A Bioinformatics Approach to Systematically Analyze the Molecular Patterns of Monkeypox Virus—Host Cell Interactions., bioRxiv (pre—print), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Arlt, A.; Schäfer, H. Role of the Immediate Early Response 3 (IER3) Gene in Cellular Stress Response, Inflammation and Tumorigenesis. Eur J Cell Biol 2011, 90, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, K.Y.; Louis, C.; Metcalfe, R.D.; Kosasih, C.C.; Wicks, I.P.; Griffin, M.D.W.; Putoczki, T.L. Emerging Roles for IL—11 in Inflammatory Diseases. Cytokine 2022, 149, 155750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widjaja, A.A.; Chothani, S.; Viswanathan, S.; Goh, J.W.T.; Lim, W. —W.; Cook, S.A. IL11 Stimulates IL33 Expression and Proinflammatory Fibroblast Activation across Tissues. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(16), 8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuong, N.T.T.; Hawn, T.R.; Chau, T.T.H.; Bang, N.D.; Yen, N.T.B.; Thwaites, G.E.; Teo, Y.Y.; Seielstad, M.; Hibberd, M.; Lan, N.T.N.; et al. Epiregulin (EREG) Variation Is Associated with Susceptibility to Tuberculosis. Genes Immun 2012, 13(3), 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, I.D.; Steach, H.; Gauld, S.B.; Reinke-Breen, L.; Karman, J.; Carr, T.L.; Wetter, J.B.; Phillips, L.; Hinchcliff, M.; Flavell, R.A. Epiregulin Is a Dendritic Cell–Derived EGFR Ligand That Maintains Skin and Lung Fibrosis. Sci Immunol 2022, 7(78), eabq6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.A.; Rather, M.I.; Tiwari, A.; Bhat, V.K.; Kumar, A. Evidence That TSC2 Acts as a Transcription Factor and Binds to and Represses the Promoter of Epiregulin. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42(10), 6243–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Luo, L.; Chen, W.; Liang, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Yue, J. Polymorphism in the EREG Gene Confers Susceptibility to Tuberculosis. BMC Med Genet 2019, 20(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hop, P.J.; Luijk, R.; Daxinger, L.; van Iterson, M.; Dekkers, K.F.; Jansen, R.; Heijmans, B.T.; ’t Hoen, P.A.C.; van Meurs, J.; Jansen, R.; et al. Genome—Wide Identification of Genes Regulating DNA Methylation Using Genetic Anchors for Causal Inference. Genome Biol 2020, 21(1), 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berasain, C.; Avila, M.A. Amphiregulin. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 28, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Ismail, S.; Ullah, A.; Bibi, S. Immuno—Informatics Profiling of Monkeypox Virus Cell Surface Binding Protein for Designing a next Generation Multi—Valent Peptide—Based Vaccine. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Barczak, K.; Gutowska, I.; Chlubek, D.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. CXCL1: Gene, Promoter, Regulation of Expression, MRNA Stability, Regulation of Activity in the Intercellular Space. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(2), 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaucha, G.M.; Jahrling, P.B.; Geisbert, T.W.; Swearengen, J.R.; Hensley, L. The Pathology of Experimental Aerosolized Monkeypox Virus Infection in Cynomolgus Monkeys (Macaca Fascicularis). Laboratory Investigation 2001, 81(12), 1581–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.; Ojha, V.; Fricke, I.; Al-Sheboul, S.A.; Imarogbe, C.; Gravier, T.; Green, M.; Peterson, L.; Koutsaroff, I.P.; Demir, A.; et al. Innate and Adaptive Immunity during SARS—CoV—2 Infection: Biomolecular Cellular Markers and Mechanisms. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11(2), 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.L.; Parekh, N.J.; Kaminsky, L.W.; Soni, C.; Reider, I.E.; Krouse, T.E.; Fischer, M.A.; van Rooijen, N.; Rahman, Z.S.M.; Norbury, C.C. A Systemic Macrophage Response Is Required to Contain a Peripheral Poxvirus Infection. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13(6), e1006435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, D.; Shepherd, N.; Lan, J.; Hu, N.; Amet, T.; Yang, K.; Desai, M.; Yu, Q. Primary Human Macrophages Serve as Vehicles for Vaccinia Virus Replication and Dissemination. J Virol 2014, 88(12), 6819–6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourquain, D.; Schrick, L.; Tischer, B.K.; Osterrieder, K.; Schaade, L.; Nitsche, A. Replication of Cowpox Virus in Macrophages Is Dependent on the Host Range Factor P28/N1R. Virol J 2021, 18(1), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, M.; Martinez, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y. A Critical Role for Direct TLR2—MyD88 Signaling in CD8 T—Cell Clonal Expansion and Memory Formation Following Vaccinia Viral Infection. Blood 2009, 113(10), 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, D.; Gentili, V.; Rizzo, S.; Schiuma, G.; Beltrami, S.; Strazzabosco, G.; Fernandez, M.; Caccuri, F.; Caruso, A.; Rizzo, R. TLR3 and TLR7 RNA Sensor Activation during SARS—CoV—2 Infection. Microorganisms 2021, 9(9), 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Reba, Qing Li, Sophia Onwuzulike, Nancy Nagy, Kyle Parker, Katharine Umphred—Wilson, Supriya Shukla, Clifford V. Harding, W. Henry Boom, Roxana E. Rojas, TLR2 on CD4+ and CD8+ T Cells Promotes Late Control of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection., 2021, bioRxiv (pre—print). [CrossRef]

- Schattner, M. Platelet TLR4 at the Crossroads of Thrombosis and the Innate Immune Response. J Leukoc Biol 2018, 105(5), 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y. γδ T Cells Are Required for CD8+ T Cell Response to Vaccinia Viral Infection. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 727046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, R.; Wesch, D.; Kabelitz, D. Correction: Serrano, R.; Wesch, D.; Kabelitz, D. Activation of Human γδ T Cells: Modulation by Toll—Like Receptor 8 Ligands and Role of Monocytes. Cells 2020, 9(3), 713. Cells 2020, 9, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Kaushik, V.; Grewal, R.K.; Wani, A.K.; Suwattanasophon, C.; Choowongkomon, K.; Oliva, R.; Shaikh, A.R.; Cavallo, L.; Chawla, M. Immunoinformatics—Aided Design of a Peptide Based Multiepitope Vaccine Targeting Glycoproteins and Membrane Proteins against Monkeypox Virus. Viruses 2022, 14(11), 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubi, A.; Khazaei, M.; Avan, A.; Hasanian, S.M.; Cho, W.C.; Soleimanpour, S. P28 Bacterial Peptide, as an Anticancer Agent. Front Oncol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, K.; Mohamed, M.R.; Zhang, L.; Villa, N.Y.; Werden, S.J.; Liu, J.; McFadden, G. Poxvirus Proteomics and Virus—Host Protein Interactions. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2009, 73(4), 730–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Navarro A, González-Soria I, Caldiño-Bohn R, Bobadilla NA. An integrative view of serpins in health and disease: the contribution of SerpinA3. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021, 320(1), C106–C118. [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, R.; MacNeill, A.L.; Wang, Y.-X.; Turner, P.C.; Moyer, R.W. Cowpox Virus CrmA, Myxoma Virus SERP2 and Baculovirus P35 Are Not Functionally Interchangeable Caspase Inhibitors in Poxvirus Infections. Journal of General Virology 2004, 85(Pt 5) Pt 5, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.C.; Bahar, M.W.; Abrescia, N.G.A.; Smith, G.L.; Stuart, D.I.; Grimes, J.M. Structure of CrmE, a Virus—Encoded Tumour Necrosis Factor Receptor. J Mol Biol 2007, 372(3), 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwitz, S.; Schutzbank, T.; Heberling, R.L.; Kalter, S.S.; Galpin, J.E. Smallpox: Residual Antibody after Vaccination. J Clin Microbiol 2003, 41(9), 4068–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, S.; Felgner, P.; Davies, H.; Glidewell, J.; Villarreal, L.; Ahmed, R. Cutting Edge: Long—Term B Cell Memory in Humans after Smallpox Vaccination. The Journal of Immunology 2003, 171(10), 4969–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanna, I.J.; Slifka, M.K.; Crotty, S. Immunity and Immunological Memory Following Smallpox Vaccination. Immunol Rev 2006, 211, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarlund, E.; Dasgupta, A.; Pinilla, C.; Norori, P.; Früh, K.; Slifka, M.K. Monkeypox Virus Evades Antiviral CD4 + and CD8 + T Cell Responses by Suppressing Cognate T Cell Activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105(38), 14567–14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Josleyn, N.; Janosko, K.; Skinner, J.; Reeves, R.K.; Cohen, M.; Jett, C.; Johnson, R.; Blaney, J.E.; Bollinger, L.; et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection of Rhesus Macaques Induces Massive Expansion of Natural Killer Cells but Suppresses Natural Killer Cell Functions. PLoS One 2013, 8(10), e77804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrati C, Cossarizza A, Mazzotta V, et al. Immunological signature in human cases of monkeypox infection in 2022 outbreak: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023, 23(3), 320–330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Sidney, J.; Wiseman, R.W.; Josleyn, N.; Cohen, M.; Blaney, J.E.; Jahrling, P.B.; Sette, A. Characterizing Monkeypox Virus Specific CD8+ T Cell Epitopes in Rhesus Macaques. Virology 2013, 447(1–2), 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, E.; Sun, M.M.; Wang, X.; Geurs, T.L.; Nelson, C.A.; Campbell, J.A.; Lippold, D.; Krupnick, A.S.; Davis, R.S.; Carayannopoulos, N.; et al. Structural Basis of Cowpox Evasion of NKG2D Immunosurveillance. Europe PMC (pre—print) 2019. [CrossRef]

- Depierreux, D.M.; Smith, G.L.; Ferguson, B.J. Transcriptional Reprogramming of Natural Killer Cells by Vaccinia Virus Shows Both Distinct and Conserved Features with MCMV. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1093381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, C.W.; Mathew, P.A.; Mathew, S.O. Roles of NK Cell Receptors 2B4 (CD244), CS1 (CD319), and LLT1 (CLEC2D) in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12(7), 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, Q.; Ding, H.; Shang, H.; Jiang, Y. CD160 Promotes NK Cell Functions by Upregulating Glucose Metabolism and Negatively Correlates With HIV Disease Progression. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 854432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edghill-Smith, Y.; Golding, H.; Manischewitz, J.; King, L.R.; Scott, D.; Bray, M.; Nalca, A.; Hooper, J.W.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Schmitz, J.E.; et al. Smallpox Vaccine–Induced Antibodies Are Necessary and Sufficient for Protection against Monkeypox Virus. Nat Med 2005, 11(7), 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karem, K.L.; Reynolds, M.; Hughes, C.; Braden, Z.; Nigam, P.; Crotty, S.; Glidewell, J.; Ahmed, R.; Amara, R.; Damon, I.K. Monkeypox—Induced Immunity and Failure of Childhood Smallpox Vaccination To Provide Complete Protection. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2007, 14(10), 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.F.; Dyall, J.; Ragland, D.R.; Huzella, L.; Byrum, R.; Jett, C.; st. Claire, M.; Smith, A.L.; Paragas, J.; Blaney, J.E.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Monkeypox Virus Infection of Cynomolgus Macaques by the Intravenous or Intrabronchial Inoculation Route. J Virol 2011, 85(5), 2112–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.T.M.; Yeh, I.-J.; Wu, C.-C.; Su, C.-Y.; Liu, H.-L.; Chiao, C.-C.; Ku, S.-C.; Jiang, J.-Z.; Sun, Z.; Ta, H.D.K.; et al. Comparison of Transcriptomic Signatures between Monkeypox—Infected Monkey and Human Cell Lines. J Immunol Res 2022, 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourquain, D.; Nitsche, A. Cowpox Virus but Not Vaccinia Virus Induces Secretion of CXCL1, IL—8 and IL—6 and Chemotaxis of Monocytes in Vitro. Virus Res 2013, 171(1), 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindrachuk, J.; Arsenault, R.; Kusalik, A.; Kindrachuk, K.N.; Trost, B.; Napper, S.; Jahrling, P.B.; Blaney, J.E. Systems Kinomics Demonstrates Congo Basin Monkeypox Virus Infection Selectively Modulates Host Cell Signaling Responses as Compared to West African Monkeypox Virus. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2012, 11(6), M111.015701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.-C.; Satija, R.; Reynolds, G.; Sarkizova, S.; Shekhar, K.; Fletcher, J.; Griesbeck, M.; Butler, A.; Zheng, S.; Lazo, S.; et al. Single—Cell RNA—Seq Reveals New Types of Human Blood Dendritic Cells, Monocytes, and Progenitors. Science (1979) 2017, 356(6635), eaah4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijdra, D.; Vorselaars, A.D.M.; Grutters, J.C.; Claessen, A.M.E.; Rijkers, G.T. Phenotypic Characterization of Human Intermediate Monocytes. Front Immunol 2013, 4(339). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siami H, Asghari A, Parsamanesh N. Monkeypox: Virology, laboratory diagnosis and therapeutic approach. J Gene Med 2023, e3521. [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Gravier, T.; Fricke, I.; Al-Sheboul, S.A.; Carp, T.-N.; Leow, C.Y.; Imarogbe, C.; Arabpour, J. Immunopathogenesis of Nipah Virus Infection and Associated Immune Responses. Immuno 2023, 3(2), 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutaftsi, M.; Tscharke, D.C.; Vaughan, K.; Koelle, D.M.; Stern, L.; Calvo-Calle, M.; Ennis, F.; Terajima, M.; Sutter, G.; Crotty, S.; et al. Uncovering the Interplay between CD8, CD4 and Antibody Responses to Complex Pathogens. Future Microbiol 2010, 5(2), 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tarke, A.; Sidney, J.; Rubiro, P.; Reina-Campos, M.; Filaci, G.; Dan, J.M.; Scheuermann, R.H.; Sette, A. Defining Antigen Targets to Dissect Vaccinia Virus and Monkeypox Virus—Specific T Cell Responses in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30(12), 1662–1670.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefet, R.; Friedel, N.; Tamir, H.; Polonsky, K.; Mor, M.; Hagin, D.; Sprecher, E.; Israely, T.; Freund, N.T. A35R and H3L Are Serological and B Cell Markers for Monkeypox Infection. medRxiv (pre—print), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rowley, D.A.; Fitch, F.W. The Road to the Discovery of Dendritic Cells, a Tribute to Ralph Steinman. Cell Immunol 2012, 273(2), 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechmann, M.; Berchtold, S.; Steinkasserer, A.; Hauber, J. CD83 on Dendritic Cells: More than Just a Marker for Maturation. Trends Immunol 2002, 23(6), 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.; ONeill, L.A.J. Metabolic Reprogramming in Macrophages and Dendritic Cells in Innate Immunity. Cell Res 2015, 2(7), 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marongiu, L.; Protti, G.; Facchini, F.A.; Valache, M.; Mingozzi, F.; Ranzani, V.; Putignano, A.R.; Salviati, L.; Bevilacqua, V.; Curti, S.; et al. Maturation Signatures of Conventional Dendritic Cell Subtypes in COVID-19 Suggest Direct Viral Sensing. Eur J Immunol 2022, 52, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, A.M.; Martin, S.; Garg, A.D.; Agostinis, P. Immature, Semi—Mature, and Fully Mature Dendritic Cells: Toward a DC—Cancer Cells Interface That Augments Anticancer Immunity. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flechsig, C.; Suezer, Y.; Kapp, M.; Tan, S.M.; Löffler, J.; Sutter, G.; Einsele, H.; Grigoleit, G.U. Uptake of Antigens from Modified Vaccinia Ankara Virus—Infected Leukocytes Enhances the Immunostimulatory Capacity of Dendritic Cells. Cytotherapy 2011, 13(6), 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, C.E. T Helper Cell Subsets: Diversification of the Field. Eur J Immunol 2023, 2250218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, S.; Popovic, S.; Djurdjevic, P.; Todorovic, D.; Djordjevic, N.; Mijailovic, Z.; Sazdanovic, P.; Milovanovic, D.; Ruzic Zecevic, D.; Petrovic, M.; et al. SARS—CoV—2 Infection Induces Mixed M1/M2 Phenotype in Circulating Monocytes and Alterations in Both Dendritic Cell and Monocyte Subsets. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0241097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sheboul, S.A.; Brown, B.; Shboul, Y.; Fricke, I.; Imarogbe, C.; Alzoubi, K.H. An Immunological Review of SARS—CoV—2 Infection and Vaccine Serology: Innate and Adaptive Responses to MRNA, Adenovirus, Inactivated and Protein Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 11(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.J.; Rushton, J.; Dekonenko, A.; Chand, H.S.; Olson, G.K.; Hutt, J.A.; Pickup, D.; Lyons, C.R.; Lipscomb, M.F. Cowpox Virus Inhibits Human Dendritic Cell Immune Function by Nonlethal, Nonproductive Infection. Virology 2011, 412(2), 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spel, L.; Luteijn, R.D.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Nierkens, S.; Boes, M.; Wiertz, E.J.H. Endocytosed Soluble Cowpox Virus Protein CPXV012 Inhibits Antigen Cross—Presentation in Human Monocyte—Derived Dendritic Cells. Immunol Cell Biol 2018, 96(2), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite Pereira, A.; Jouhault, Q.; Marcos Lopez, E.; Cosma, A.; Lambotte, O.; le Grand, R.; Lehmann, M.H.; Tchitchek, N. Modulation of Cell Surface Receptor Expression by Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara in Leukocytes of Healthy and HIV—Infected Individuals. Front Immunol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, F.; Tao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Muschaweckh, A.; Zollmann, T.; Protzer, U.; Abele, R.; Drexler, I. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara—Infected Dendritic Cells Present CD4 + T—Cell Epitopes by Endogenous Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Presentation Pathways. J Virol 2015, 89(5), 2698–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahroudi, A.; Garber, D.A.; Reeves, P.; Liu, L.; Kalman, D.; Feinberg, M.B. Differences and Similarities in Viral Life Cycle Progression and Host Cell Physiology after Infection of Human Dendritic Cells with Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara and Vaccinia Virus. J Virol 2006, 80(17), 8469–8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breloer, M.; Fleischer, B. CD83 Regulates Lymphocyte Maturation, Activation and Homeostasis. Trends Immunol 2008, 29(4), 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, B.; Islam, S.M.S.; Ryu, H.M.; Sohn, S. CD83 Regulates the Immune Responses in Inflammatory Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(3), 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Gao, C.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, X. CD83—Stimulated Monocytes Suppress T—Cell Immune Responses through Production of Prostaglandin E2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108(46), 18778–18783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-J.; Song, Y.-N.; Geng, X.-R.; Ma, F.; Mo, L.-H.; Zhang, X.-W.; Liu, D.-B.; Liu, Z.-G.; Yang, P.-C. Soluble CD83 Alleviates Experimental Allergic Rhinitis through Modulating Antigen—Specific Th2 Cell Property. Int J Biol Sci 2020, 16(2), 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenmuller, W.; Drexler, I.; Ludwig, H.; Erfle, V.; Peschel, C.; Bernhard, H.; Sutter, G. Infection of Human Dendritic Cells with Recombinant Vaccinia Virus MVA Reveals General Persistence of Viral Early Transcription but Distinct Maturation—Dependent Cytopathogenicity. Virology 2006, 350(2), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chavan, R.; Feinberg, M.B. Dendritic Cells Are Preferentially Targeted among Hematolymphocytes by Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara and Play a Key Role in the Induction of Virus—Specific T Cell Responses in Vivo. BMC Immunol 2008, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Wang, W.; Cao, H.; Avogadri, F.; Dai, L.; Drexler, I.; Joyce, J.A.; Li, X.-D.; Chen, Z.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a CGAS/STING—Mediated Cytosolic DNA—Sensing Pathway. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10(4), e1003989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabé, S.; Guay-Giroux, A.; Tormo, A.J.; Duluc, D.; Lissilaa, R.; Guilhot, F.; Mavoungou-Bigouagou, U.; Lefouili, F.; Cognet, I.; Ferlin, W.; et al. The IL—27 P28 Subunit Binds Cytokine—Like Factor 1 to Form a Cytokine Regulating NK and T Cell Activities Requiring IL—6R for Signaling. The Journal of Immunology 2009, 183(12), 7692–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Bathke, B.; Lauterbach, H.; Pätzold, J.; Kassub, R.; Luber, C.A.; Schlatter, B.; Hamm, S.; Chaplin, P.; Suter, M.; et al. A Major Role for TLR8 in the Recognition of Vaccinia Viral DNA by Murine PDC? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107(36), E139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP—Sensing Receptors in Sterile Inflammation and Inflammatory Diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20(2), 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, D.L.; Szczeniowski, M.; Esteves, K. Re—Emergence of Monkeypox in Africa: A Review of the Past Six Years. Br Med Bull 1998, 54(3), 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarlund, E.; Lewis, M.W.; Carter, S. V.; Amanna, I.; Hansen, S.G.; Strelow, L.I.; Wong, S.W.; Yoshihara, P.; Hanifin, J.M.; Slifka, M.K. Multiple Diagnostic Techniques Identify Previously Vaccinated Individuals with Protective Immunity against Monkeypox. Nat Med 2005, 11(9), 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, J.G.; Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M.; Forthal, D.N.; Rizk, Y. Prevention and Treatment of Monkeypox. Drugs 2022, 82(9), 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C. Monkeypox Response Relies on Three Vaccine Suppliers. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40(9), 1306–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, P.R.; Hahn, M.; Lee, H.S.; Koca, C.; Samy, N.; Schmidt, D.; Hornung, J.; Weidenthaler, H.; Heery, C.R.; Meyer, T.P.H.; et al. Phase 3 Efficacy Trial of Modified Vaccinia Ankara as a Vaccine against Smallpox. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 381(20), 1897–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Liu C, Du Z, Bai Y, Wang Z, Gao C. Real—world effectiveness of mpox (monkeypox) vaccines: a systematic review [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 11]. J Travel Med 2023, taad048. [CrossRef]

- Damon, I.K.; Damaso, C.R.; McFadden, G. Are We There Yet? The Smallpox Research Agenda Using Variola Virus. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10(5), e1004108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shahed—AI—Mahmud, M.; Chen, A.; Li, K.; Tan, H.; Joyce, R. An Overview of Antivirals against Monkeypox Virus and Other Orthopoxviruses. J Med Chem 2023, 66(7), 4468–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Pevear, D.C.; Davies, M.H.; Collett, M.S.; Bailey, T.; Rippen, S.; Barone, L.; Burns, C.; Rhodes, G.; Tohan, S.; et al. An Orally Bioavailable Antipoxvirus Compound (ST—246) Inhibits Extracellular Virus Formation and Protects Mice from Lethal Orthopoxvirus Challenge. J Virol 2005, 79(20), 13139–13149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Du, Z.; Lamers, M.M.; Incitti, R.; Tejeda-Mora, H.; Li, S.; Schraauwen, R.; van den Bosch, T.P.P.; de Vries, A.C.; Alam, I.S.; et al. Mpox Virus Infects and Injures Human Kidney Organoids, but Responding to Antiviral Treatment. Cell Discov 9, 34. [CrossRef]

- Florescu, D.F.; Keck, M.A. Development of CMX001 (Brincidofovir) for the Treatment of Serious Diseases or Conditions Caused by DsDNA Viruses. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014, 12(10), 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quenelle, D.C.; Lampert, B.; Collins, D.J.; Rice, T.L.; Painter, G.R.; Kern, E.R. Efficacy of CMX001 against Herpes Simplex Virus Infections in Mice and Correlations with Drug Distribution Studies. J Infect Dis 2010, 202, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smee, D.F.; Dagley, A.; Downs, B.; Hagloch, J.; Tarbet, E.B. Enhanced Efficacy of Cidofovir Combined with Vaccinia Immune Globulin in Treating Progressive Cutaneous Vaccinia Virus Infections in Immunosuppressed Hairless Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59(1), 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, A.E.; Spencer, J.F.; Ying, B.; Buller, R.M.L.; Wold, W.S.M.; Toth, K. Cidofovir and Brincidofovir Reduce the Pathology Caused by Systemic Infection with Human Type 5 Adenovirus in Immunosuppressed Syrian Hamsters, While Ribavirin Is Largely Ineffective in This Model. Antiviral Res 2014, 112, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylden, G.D.; Hirsch, H.H.; Rinaldo, C.H. Brincidofovir (CMX001) Inhibits BK Polyomavirus Replication in Primary Human Urothelial Cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59(6), 3306–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat RA; Shah R; El-Sakka AA, B.A.K.M.L.F.S.R.A.A.A.B. Human Monkeypox Disease (MPX). Infezioni in Medicina 2022, 30. [CrossRef]

- Overton, E.T.; Lawrence, S.J.; Stapleton, J.T.; Weidenthaler, H.; Schmidt, D.; Koenen, B.; Silbernagl, G.; Nopora, K.; Chaplin, P. A Randomized Phase II Trial to Compare Safety and Immunogenicity of the MVA—BN Smallpox Vaccine at Various Doses in Adults with a History of AIDS. Vaccine 2020, 38(11), 2600–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahariya, C.; Thakur, A.; Dudeja, N. Monkeypox Disease Outbreak (2022): Epidemiology, Challenges, and the Way Forward. Indian Pediatr 2022, 59(8), 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Andreani, J.; Garrett, N.; Winter, M.; Golubchik, T.; Breuer, J.; Reynolds, C.; Brailsford, S.R.; Harvala, H.; Simmonds, P. Absence of Detectable Monkeypox Virus DNA in 11,000 English Blood Donations during the 2022 Outbreak. Transfusion (Paris) 2023, 63(4), 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, W.; Beard, P.M.; Brookes, S.M.; Frost, A.; Roberts, H.; Russell, K.; Wyllie, S. The Risk of Reverse Zoonotic Transmission to Pet Animals during the Current Global Monkeypox Outbreak, United Kingdom, June to Mid—September 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27(39), 2200758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitjà, O.; Alemany, A.; Marks, M.; Lezama Mora, J.I.; Rodríguez-Aldama, J.C.; Torres Silva, M.S.; Corral Herrera, E.A.; Crabtree-Ramirez, B.; Blanco, J.L.; Girometti, N.; et al. Mpox in People with Advanced HIV Infection: A Global Case Series. The Lancet 2023, 401(10380), 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloch, E.M.; Sullivan, D.J.; Shoham, S.; Tobian, A.A.R.; Casadevall, A.; Gebo, K.A. The Potential Role of Passive Antibody—Based Therapies as Treatments for Monkeypox. mBio 2022, 13(6), e0286222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Martínez, Y.; Zambrano-Sanchez, G.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J. Monkeypox and HIV/AIDS: When the Outbreak Faces the Epidemic. https://doi.org/10.1177/09564624221114191 2022, 33(10), 949–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan N, Haq ZU, Malik A, Mehmood A, Ishaq U, Faraz M, Malik J, Mehmoodi A. Human monkeypox virus: An updated review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022, 101(35), e30406. [CrossRef]

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, Lienert F, Weidenthaler H, Baer LR, Steffen R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022, 16(2), e0010141. [CrossRef]

- Kmiec D, Kirchhoff F. Monkeypox: A New Threat? Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(14), 7866. [CrossRef]

- Lim CK, Roberts J, Moso M, et al. Mpox diagnostics: Review of current and emerging technologies [published correction appears in J Med Virol. 2023 Feb;95(2):e28581]. In J Med Virol.; 95(2): e28581]. J Med Virol. 2023, 2023; Volume 95, 1, p. e28429. [CrossRef]

- Perdiguero B, Esteban M. The interferon system and vaccinia virus evasion mechanisms. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009, 29(9), 581–598. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).