Introduction

Global value chains continue to grow faster than any other trade. They represent 70% of world trade (

WTO, 2019; OECD, 2020). These global value chains integrate into a global production process a set of activities and actors dispersed among several countries and companies (

Gereffi & Fernandez-Stark, 2016). In this context, the countries in the GVC (Global Value Chains) networks have benefited from increased foreign direct investment, productivity, additional jobs, technology transfers and improved living standards of local populations

1.

Thus, national economies have begun processes of specialization and adaptation to new conditions of access to resources and markets, which now include social and environmental objectives, since even multinationals and extensive agricultural holdings create significant negative externalities. These GVCs are facing significant change due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the shortages caused by these crises throughout supply chains. In addition to these external shocks, GVCs also face two internal mechanisms. Firstly, the desire of multinationals to reorganize their industrial operations regionally. Second, the ambition of many countries to produce and capture greater added value through their efforts to develop solutions based on ESG and green investment (Amachraa A. & Quélin B, 2022).

The vulnerability of the global value chain is the ability to adapt to external shocks and the potential impacts presented by the fragmentation of the global production process and the interdependence between several activities and actors.

Global agricultural and agri-food production is relatively well integrated into global value chains. Globally, 21% of the value of agri-food products exported by a given country was embodied in goods and services produced in other countries. Services are an increasingly important component in agro-food value chains. They represent around 25% of the total value added of agricultural exports

and 35% of agri-food exports ( OECD

2 (Tiva) and UN (UN Comtrade Labs ) databases)

3.

Global agricultural value chains, structured around a small number of global hubs such as China, the United States and Europe, are generally driven by multinationals and large retail markets

4 (Humphrey J. &

Memedovic O., 2006 ) around which are articulated layers of suppliers of different ranks as well as the entire supply chain required to lead to the final food product (

Gereffi et al, 2005; Bair and Palpacuer, 2015 ). According to Miller and Jones (

2013), seller-buyer relationships in an agricultural value chain can be structured into five different categories:

- (1)

Spot (cash) market, where producers sell their products and prices fluctuate; this is the most risky in terms of market pricing;

- (2)

Contract to produce and to buy, known more generally as 'contract farming';

- (3)

Long-term, often informal bonds characterized by building trust and interdependence between parties;

- (4)

Investment made by a buyer for the benefit of a producer, characterized by high credibility and strong dependence on the producer and

- (5)

Totally vertically integrated company.

The global wheat value chain is a representative example of this structuring since it is a staple cereal produced in Ukraine, Russia and Australia, then transformed into flour in Indonesia and Turkey before being exported to make noodles in China or bread in Africa and the Middle East (OECD, 2020 ).

The Kingdom of Morocco, a world major in fertilizers, has chosen to develop green agriculture integrated into AGVCs ( Global Agricultural Value Chains ). Today, more than 43% of its agricultural production is destined for global agri-food value chains, and nearly two-thirds of Moroccan agricultural exports (63%) are destined exclusively for the EU market, of which 73% are fresh fruits and vegetables (Exchange Office, 2022 ). The country is now Africa's fourth-largest exporter of food products and a world leader in exports of citrus fruits, tomatoes, sardines, capers, green beans, olive oil and argan. However, water stress and trade tensions considerably mitigate the positive impacts recorded as part of implementing the Green Morocco plan.

The kingdom benefits from favorable climatic and agricultural conditions to produce fruit and vegetables, which are increasingly in demand in EU markets. While Europe and North America represent about 17% of the current world population, they account for 32% of the global demand for fruits and vegetables. The EU and US markets are buoyant but are protected by stringent standards (

European Commission 5, Lee and Gereffi, 2012 ). Morocco must, in fact, respect an increasing number of conditions motivated by three kinds of concerns: (

1 ) food security and consumer health, (

2 ) fair use of water resources and adaptation to climate change, and (

3 ) stakeholder motivation and positive comfort (

Amachraa A & Maad H., 2023 ).

The objective of this work is to show from a framework of theoretical analysis and the case study of Morocco:

-

How a green and innovative agricultural policy could strengthen the adaptability of actors and help countries to gain in competitiveness and food security

6,

-

How sustainable global agricultural value chains could support local agricultural SMEs and encourage innovation and R&D,

-

What would be the contribution of Morocco, as a global fertilizer hub, to the development and stability of agricultural supply chains in Africa,

It will therefore be a question of an analysis of the challenges of integrating the agriculture and food sector into global value chains and the study of four different agro-industries: fertilizers, fruits and vegetables, sugar and wheat.

Exploring a triangular approach

The realization of this work is based on a tripartite approach:

- (1)

An analysis of major trends in agricultural global value chains;

- (2)

A diagnosis of the agriculture and food sector as well as the identification of Morocco's public policy challenges in an uncertain and complex context, and,

- (3)

A study of four agricultural and agri-food industries to assess their potential and the challenges of cooperation, sustainability and agricultural innovation.

A triangular approach has been adopted to allow analysis at several distinct but complementary levels using macroeconomic sources ( FAO, OECD, UN Cometrade, WTO, ministries, HCP, Foreign Exchange Office, NGOs, etc. ), sector analyzes (chains of agricultural value [ fertilizers, fruits and vegetables, sugar and wheat ], agro-industrial ecosystems and agropoles, etc. ), surveys and interviews with international and national actors ( MNEs, SMEs, cooperatives, industrialists, farmers, public actors, young people and women from rural areas and NGOs, etc. ).

A symphony of policy, innovation, and food security

The current double crisis has strongly affected the global agricultural and food sector. It has destabilized supply chains and agri-food systems that thought they were sustainable. Global agricultural value chains are indeed likely to be impacted at several levels:

-

The rising cost of raw materials and agricultural inputs;

-

An upward trend in the prices of fertilizers and phytosanitary products;

-

Freight cost with increased transportation cost, and,

-

Cost of labor, water and energy for agricultural and industrial activity.

Added to this is the high risk posed by climate change and water stress. However, in some countries such as Morocco, the industrial pricing of energy and water is currently stable because the State subsidizes it. Still, it is difficult to plan for the long term if the crisis persists.

Orchestrating Prosperity: Agricultural Policy and the Path to Food Security

In general, agricultural policies aimed to increase agricultural production and promote food security. They essentially designated all the laws relating to national agriculture ( public aid ) and imports of agricultural and food products ( non-tariff barriers ). The European Common Agricultural Policy ( CAP ) is often cited as a good 7 representative example.

Nevertheless, some policies have been particularly criticized for their social, environmental and governance impact. Thus, the objectives to be achieved have evolved and are different from one country to another, ranging from stable food supply and price stabilization to product quality and competitiveness, including consumer protection, respect for the environment and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Policy tools are also variable and can cover border protection ( EU & US ), land reform ( Ethiopia & Africa South ), agricultural and irrigation subsidies ( Morocco and Spain ), export support ( Egypt and Tunisia ), diversification and differentiation of agricultural territories ( Germany and France ) and sustainable management of natural resources and waterborne ( United States and Australia ).

Similarly, the challenges are not the same for all countries: the lack of water, the management of agricultural land, the income of small farmers, health risks, non-tariff barriers, food independence, respect for the environment and adaptation to climate change top the concerns of agricultural policies. In many developing countries, the agricultural and agri-food sector presents a significant dualism between commercial export agriculture and family subsistence agriculture. In many countries, the agricultural and food context remains marked by a focus on raw materials and a strong dependence on imports of basic products.

Furthermore, In the sense that they do not subsidize input use and agricultural production, they have a positive and lasting impact on participation in global value chains and on local value added creation (OECD, 2020). In this case, farmers have the flexibility to react to market fluctuations and choose their crops and technologies independently of public policy.

On the other hand, the use of market-distorting public support is likely to have a negative influence on the comparative advantages of participation in global value chains, highlighting potential losses in value added due to protectionist policies.

Therefore, government policy should focus on improving overall competitiveness and enabling agribusinesses to exploit underlying comparative advantages rather than only encouraging subsidy in the belief that it brings domestic added value ( Greenville et al., 2017 ).

In this context, trade protection and government support policies for agriculture will likely distort competition rules and reduce the benefits of participation in global value chains. Although state intervention in the case of Morocco and through the production subsidy was deemed useful in the short term and made it possible to maintain a comparative advantage in exports, aid for irrigation has favored the expansion of agricultural areas but also the overexploitation of groundwater ( CESE, 2021, Srairi M., 2021 and Chiche, 2021 ).

Moreover, these subsidy policies did little to benefit local agricultural SMEs ( Amachraa and Quelin, 2022 ) and the public response (aid to transporters) to deal with the crisis of soaring prices was not sufficient ( Akesbi N., 2013 and 2022 ). Added to this the poor adaptation to climate change and low-paid agricultural work in rural Morocco ( Srairi M., 2021 ).

Thus, government policies must strike the right balance between available water resources and agricultural and food production. More work should also be done to facilitate private sector participation in global agricultural value chains and help structure agricultural SMEs around agropoles and agricultural and technological training centres.

Food security is an essential element of agricultural policy. According to FAO ( 1996 ), it is achieved when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food, meeting their dietary needs and preferences for leading healthy and active lives. Thus, four pillars form this concept: availability, access, usage and stability.

However, the concept does not specify how governments should achieve food security. "Chronic malnutrition could not have been eliminated simply by more humane national policies, but it required major advances in production technology." ( Fogel, 1991 ).

So how can agricultural policies and national economies improve food security? How will global value chains help countries stabilize prices and guarantee partners and consumers of agricultural products good value for money? There are indeed interactions and synergies between food security and economic growth. The two interact in a process that continually reinforces itself during economic development. No country has experienced rapid economic growth without first achieving food security.

Similarly, "no country has succeeded in its industrial revolution without a prior ( or at least simultaneous ) agricultural revolution. To neglect agriculture in the early stages of development is to neglect development" ( Timmer, 2015 ). To deal with food insecurity, governments have developed multiple solutions: In the short term and in crisis conditions, there are essentially social safety nets, income transfers to poor households and the suspension of the debt of some low-income countries. In the medium and long term, the priority is to promote national agriculture and economic growth ( FAO, 2020; Tsakok i., 2021). Cardwell and Ghazalian ( 2020 ), Udmale et al. ( 2020 ), and Barichello ( 2020 ) suggest controlling food prices and developing an efficient supply system.

Also, solutions based on blockchain, artificial intelligence and digital platforms can lead to a reduction in food insecurity at the global level ( FAO 2020; KLASSEN & MURPHY, 2020, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN & East Asia, 2021 ). There is also a need to deal with climate-related disasters and adopt mitigation strategies and mechanisms ( Allison et al., 2009; Tirivangasi, 2018). According to different authors, home food delivery and e-commerce have likely improved the shelf life of food and succeeded in expanding markets.

In a context of crisis, the priorities of a green and innovative agricultural policy are multiple: Develop resilient agricultural systems to reduce the consumption of water resources by agriculture, encourage R&D to face new challenges, reduce the negative impacts of agriculture on the environment and increase their positive effects, improve the added value of agri-food value chains and ensure a good relationship between partners quality/price of agricultural products, maximizing the well-being of small farmers to ensure a decent standard of living for the rural population, in particular by improving the incomes of workers in agriculture, meet societal expectations in terms of food and health concerns related to agricultural production and practices and, finally, build adaptive capacity, anticipate crises and reduce price, productivity and income fluctuations ( FAO, 2021; Kuper, 2022; Tsakok i., 2021; Fosse j., 2019 ).

Seeds of Innovation: Unleashing the Power of Collaboration and Technology in Agrarian Landscape

Technology transfer is the most widespread model. It has its origin in the spread of hybrid corn in the 40s. According to this model, research is the only source of innovation to disseminate knowledge to farmers (Chambers and Jiggins, 1987). Agricultural extension is the most used form of support. It relies on a network of young agricultural technicians. Moreover, this is the model that we tried to implement in Africa through the approach of training and field visits ( Rolling, 2009 ).

Today, times have changed, as have the agricultural innovation programs and projects resulting from this model, which also affect vast areas of agriculture and food: robotics and automation, data management and farms, material and water management, controlled environment agriculture, biotechnology, breeding, food processing, innovative ingredients, consumer packaged goods and retail, supply chain, traceability and packaging, waste, food safety, etc.

In 1946, LEWIS initiated research on innovation in close interaction with local actors. In the 70s, farming systems approaches developed ( Norman DW., 2002, Jouve and Mercoiret, 1987 ), giving rise to more participatory approaches such as rapid rural appraisal ( RRA: Chambers R., 1989 ). , participatory technology development ( PTD: Ashby and Sperling, 1995; Wettasinha et al., 2003 ) and participatory learning and action research ( PLAR ) ( Pretty, J. N., et al., 1995). Subsequently, Paul ENGEL and Monique SALOMON ( 1997 ) developed the Rapid Appraisal of Agricultural Knowledge System ( RAAKS ) methodology. The Farmer Field Schools ( FFS ) model, dedicated to learning through experimentation, is based on often complex practices such as integrated pest management ( IPM ) and integrated soil fertilization management ( Rolling, 2009 ).

These agricultural innovation systems, widely supported by NGOs and corporate foundations, aim to unite stakeholders around an agricultural project to facilitate the development of environments favorable to agricultural innovation, economic empowerment and food security. As it is a system, it is essential to act on several layers. The Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems ( AKIS ) is a famous concept designed to avoid the dispersion of agri-food systems. Innovation can therefore be seen as the property emerging from the interaction between the stakeholders of a resource or an ecosystem service ( Bawden and Packam, 1993 ).

Systems thinking ( Checkland and Scholes 1994 ) has become an important means of understanding what is happening in the agriculture and food sector. According to this perspective, the farmer is a main actor in the agricultural system because of his local know-how and his expertise. It is a source of knowledge and innovation proposals. With AKIS aiming to facilitate linkages and communication between actors in the system, this system emerged in response to challenges in innovation transfer, adoption and diffusion theory, which examined why people were adopting - or not - new farming practices ( Leewis 2004 ).

This theory is the basis of the concept of the National Agricultural Research System ( NARS ) and continues to dominate in developing countries ( Rolling, 2009 ). In this context, the social and human sciences have contributed a great deal to the construction of productive and innovative agricultural systems that did not, however, succeed in bringing on board the small farmers 'left behind' by the existing models.

Current agricultural systems should further strengthen the capacities of actors to increase the social capital of farmers to improve the quality of life of rural communities. We should now consider a different innovation system where the farmer would be at the heart of the action. The birth of Living Labs, the development of agricultural and technological training centers and the emergence of innovative, inclusive agricultural platforms without prerequisites have opened the door to new opportunities.

Thus, the beneficiaries of these structures entering into integrated courses can realize that the chosen structure can be able to evolve according to the objectives of the agricultural project. Cooperatives and young entrepreneurs have the opportunity to evolve into a structured business; a young farmer can decide to create his social enterprise in rural areas or an association to carry out his project because of the non-profitable nature of his activity and its strong social impact.

In this configuration, we observe - around the world - how farmers use polyculture to increase their productivity and their resilience and, above all, to fight against drought and pests, better manage water and pastures collectively at the same time. image of these new networks of women and clever young people in Morocco and Kenya who have succeeded in putting into practice service cooperatives and laboratories of good practices between farmers and inhabitants within rural communes. Let's not forget either the emergence of Agritech projects led by ambitious farmers and technological start-ups aiming to develop precision agriculture. The use of 'cheap' drones is an excellent prospect for collecting, analyzing and exploiting agricultural data, which is still expensive and difficult to obtain.

The green morocco plan - cultivating a sustainable future

Cultivating Change: Unearthing the Transformative Vision of Morocco's Green Morocco Plan

Agriculture is a key engine of development in Morocco. The country is one of the major fertilizer producers in the world, 3rd exporter of fruits and vegetables in the MENA region and 4th in Africa. Agriculture contributes up to 12.3% of the GDP and employs approximately 2,960,000 people directly and indirectly. In Morocco, the number of people living from agriculture is estimated at more than 10 million. With 30.4 million hectares of fertile land and 1.6 million farmers, Morocco is a major producer of citrus fruits, tomatoes, olives, sugar, dates and argan, which is a considerable asset for developing an agri-food industry. The latter represents 4% of GDP, 161,000 jobs, and 2,100 companies with a recovery capacity of around 45 million tonnes, generating 3.9 billion MAD for export.

Despite this potential, agricultural production is not stable and variations in its contribution to GDP remain significant (11% to 18% ) depending on the agricultural seasons and climatic conditions. Consequently, the contribution of Moroccan agriculture to GDP growth is declining. Agricultural growth was relatively strong until 2015, driven by investments in export-oriented value-added sectors. However, the performance of Moroccan agricultural value chains has declined by 5.5% in recent years. The value of agricultural production decreased by 7% in 2020 and by another 4.9% the following year.

The constraints are diverse: a scarcity of fertile land and water resources, associated with recurrent droughts which considerably affect agricultural production, essential for food security and animal feed. This drop in agricultural production leads to an increasing dependence on food imports. In 2022, the kingdom's cereal harvests fell by 67% compared to 2021, increasing the need for wheat imports to 10 million tonnes.

It is nevertheless true that this decline and volatility of the agricultural sector is in sync with the overall performance of the Moroccan economy. The contribution of the agro-food industry to the economy has even been lower in recent years compared to the contribution of agriculture since the products of the agro-industry are mainly destined for the domestic market. The dominant service sectors, including tourism, have shown the strongest growth over the past decade. By comparison, the agricultural sectors of the EU-27 experienced stronger growth of 5% in 2020.

Many constraints are holding back the growth of the agricultural sector, including water stress and low and volatile productivity. Moroccan agricultural policy is mainly export-oriented rather than local food security, which generates intense pressure on water resources. In 2021, the ESEC sounded the alarm bell by calling on the government to take urgent measures: "The water shortage situation in Morocco is alarming, since its water resources are estimated at less than 650 m 3 /inhabitant/year, against 2,500 m

3 in 1960, and should fall further by 2030"

7.

Furthermore, the average yields of most Moroccan crops are volatile and lower than those of EU countries

8. For example, the average yields of the main Moroccan cereals - wheat and barley - which cover a non-negligible share of arable land, have reached only half of the average yields in the EU over the last decade

9. This weakness is mainly linked to the difficult agro-climatic conditions, chronic droughts (

the most important in 2012, 2016, 2019 and 2020, 2022 ) and the non-optimal use of production factors, including the expansion of agricultural systems. Irrigation. Obsolete technologies and poor agricultural practices also add to the equation. The lag in agricultural productivity must also be considered in the light of dual farm structures.

It is likely that a limited number of efficient and competitive farms are making productivity gains while the majority are performing less well. As a result, the agriculture and agribusiness sector is dominated by SMEs and cooperatives. Of nearly 1.5 million agricultural holdings ( farms ), more than 98% are SMEs. The agri-food sector comprises around 2,050 companies, most of which are also classified as SMEs. Most agribusinesses are active in low-value addition, covering cereal flours, oil manufacturing, processing ( canning ) of fruits and vegetables, fish and animal feed. The introduction of the Cooperatives Act in 2012 led to a growth in the number of agricultural cooperatives, exceeding 10,000 in 2015.

The current level of standards, such as food and feed safety, quality, hygiene, animal health and welfare, as well as environmental sustainability, prevent better access to the EU market

10. Certification and widespread acceptance of quality schemes have not yet been widely implemented. In particular, the livestock sector in the EU is subject to strict standards that prevent many national economies from accessing more than 500 million consumers.

Moroccan agriculture is characterized by persistently low labor productivity. Given the large number of farmers in a medium-subsistence situation in Morocco, labor productivity is low and declining compared to other sectors of the economy. It remains far behind regional partners and the EU-27. While the Moroccan agricultural sector has a relatively high share in gross value added ( 12% ) compared to Tunisia ( 10.2% ) and the EU ( 1.9% ), the share of jobs in agriculture is significantly higher in Morocco, indicating low labor productivity. As a result, Moroccan labor productivity was only $4,425 per full-time equivalent in agriculture, compared to an average of $37,328 in Europe.

However, since the launch of the Green Morocco Plan in agriculture, labor productivity has improved, thanks, in particular, to progress in mechanization. Higher yields have also led to improved farm incomes, although gaps with other sectors of the economy persist.

Flowing Towards Sustainability: Untangling the Water-Food Security Nexus in Morocco's Agrarian Revolution

The Moroccan agricultural sector is affected by price, production and income volatility. Unfavorable climatic phenomena are frequent and increasingly intense. Dry seasons often have an impact on agriculture and the entire Moroccan economy. In particular, rainfed crops are affected by water stress and water scarcity, which limits agricultural productivity and impacts soil quality. The projected increase in temperature and precipitation is subject to great uncertainty, although recent years indicate greater variability in productivity, resulting in an overall decline in cereal production (-67% in 2022 ).

Rising costs of agricultural inputs, especially energy ( fuel ) and fertilizers have led to greater price volatility. These imbalances between productivity and the volatility of production costs affect incomes and, therefore, competitiveness. Vulnerabilities to climate change may vary depending on farm size. Generally, the climate varies considerably within Morocco. The Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the desert influence rainfall and temperature. The north is favored by rain, while the south is affected by regular droughts. For example, the most recent droughts from November 2015 to spring 2016 resulted in a 3% drop in economic growth. Due to crop diversification, Northern Morocco is the most resilient, while the center of the country, which focuses on cereals and livestock, is less so.

Variations also exist due to the dual-holding structure in Morocco. Large agricultural enterprises are vulnerable to climate change as they focus more on labor-intensive crops such as cereals, and the lack of crop diversification makes them economically vulnerable. SMEs are more socially vulnerable to climate change, i.e. they tend to diversify production towards more labor-intensive crops, such as fruit and vegetables, since they lack appropriate technologies and insurance offers, significantly impacting their livelihoods.

Moroccan agricultural policy aims to modernize the sector, improve productivity, stimulate exports and develop green and innovative agriculture. In recent decades, agricultural policy has aimed to protect traditional and inclusive agriculture. It responds to the recent demand for increased value addition in agriculture, focusing on local production, including improving quality standards and strengthening value chains, while creating an enabling environment for creating jobs.

Disruptions to global value chains as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded have brought food security issues to the centre of attention. Aspirations for a modern, social and environmentally sustainable agricultural sector remain a priority. Improving agricultural productivity requires the use of modern technologies, such as precision agriculture and the deployment of digital technologies. The expansion of irrigation infrastructure and the efficient use of water have also been the subject of an evolving agricultural policy.

The Green Morocco Plan focused on sustainability while addressing employment, income and prospects for young farmers. The plan aimed to strengthen market orientation and agricultural growth, double the added value of primary value chains and create 1.5 million jobs.

Since 2008, the PMV has contributed to the performance of the agricultural sector by supporting plantations of more than 400,000 ha of fruit and olive trees, as well as investments in the irrigation sector, which have also shown improvements. productivity ( 3% per year on average for horticulture, 4% for citrus fruits and almost 2% for olives ).

Targeting rural SMEs while focusing on boosting employment and sustainable management of natural resources is the goal of a new agricultural strategy. Launched in February 2020, the new agricultural strategy 'Green Generation 2020-2030' calls for the consolidation of the achievements of the Green Plan and to draw lessons to complete the other links in the agricultural value chain not yet served to date. The strategy aims to contribute to the emergence of an agricultural middle class while strengthening investments, the sustainable management of natural resources, support for young farmers, improving access to agricultural insurance and constructing a social protection framework.

Morocco's agricultural sector is relatively well managed, with the government acting as a regulator that controls prices and provides subsidies. The state sets prices for essential agri-food products, such as wheat, sugar, oilseeds and milk. The system is motivated by the objective of protecting farmers and consumers from price volatility while maintaining their level of competitiveness in international markets. To lower the price paid by processors and, at the other end of the chain, by consumers, part of the income received by farmers comes from subsidies. The result is that the Moroccan government transfers market risk from farmers and consumers to the detriment of the government budget.

Agricultural inputs are also subject to price caps (fixing) and subsidies. Despite Morocco's agricultural potential, there is a strong demand for inputs such as seeds, fertilizers and phytosanitary products. The number of companies importing seeds is estimated at 80, while those handling phytosanitary products are 70. Fertilizer use in Morocco is only a quarter of the average amount used in Italy and one-eighth of the volumes consumed in France.

As a result, the Ministry of Agriculture is making great efforts to improve supply through more competitive prices. The state regulates prices and provides subsidies for agricultural inputs. The distribution of seeds and fertilizers is also controlled, but this concerns more the better quality inputs. Other contributions are also offered informally.

With an annual expenditure of 3.4 billion MAD ( 330 million euros ) in aid and subsidies, the State devotes 0.29% of its GDP to agriculture. This is higher than the expenditure of most African economies in this area. Still, this figure remains lower than the share of agricultural expenditure in the average of the EU-27 ( 0.36% ). The level of expenditure in Moroccan agriculture has increased by 36% since the year 2011. More than 50% of investment support is granted to irrigation, the rest being dedicated to agricultural equipment, intensification of animal breeding and the planting of fruit trees.

Part of the public support program is intended to deal with adverse climatic phenomena, in particular drought. Through the PMV, agricultural insurance is subsidized, with a share of the agriculture budget reserved for R&D. Public spending in Moroccan agriculture also includes export subsidies to reduce export freight costs and position these agrifood products in international markets.

Despite international commitments under the World Trade Organization Agreement on Agriculture to phase out these subsidies to create fairer competition, Morocco's appropriate policies still provide these financial instruments.

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Water and Forests has a broad mandate that covers most rural areas. It coordinates the formulation and implementation of the PMV with the support of several subordinate bodies: the Agricultural Development Agency ( ADA ), the National Food Safety Office ( ONSSA ) and the National Office of Agricultural Advice ( ONCA ). The Department of Agriculture also coordinates, in partnership with the Ministry of the Interior, regional administrations and municipalities for the management of retail and wholesale markets as well as the Ministry of Industry and Commerce on matters relating to the food industry. The National Institute for Agricultural Research ( INRA ) specializes in R&D, adaptation to climate change, irrigation, productivity and soil quality monitoring. Other research institutes, such as the Agronomic and Veterinary Institute ( IAV ) and the National School of Agriculture ( ENA ) and, more recently, some specialized subsidiaries of UM6P, also take part in R&D efforts in the country. There are several categories of producer representations, such as Chambers of Agriculture, sectoral federations, associations and economic interest groups (EIGs). These inter-branch associations aim to improve the value chain integration and organise public-private dialogue.

Balancing Trade Winds: Navigating Global Value Chains Amidst Trade Tensions

After years of persistent agrifood trade deficits, Morocco has generated consistent surpluses since 2017. The country is now Africa's fourth largest exporter of agrifood products and a world leader in exports of citrus fruits, tomatoes, capers, green beans, argan oil and olives. This trend to become an exclusive exporter of agri-food products is based on the growth of exports of fresh agricultural products, which have increased by 94% over the last decade. While the development of exports of higher-value Moroccan processed agri-food products is also showing growth, imports remain on the rise and still exceed these exports.

As Morocco is not self-sufficient in primary and processed agri-food products such as wheat, corn, sugar, soybean oil, tea and tobacco products, imports further affect the persistent trade deficit of processed agri-food products of greater value. It is estimated that almost 40% of the income generated by the agri-food sector is linked to the processing of imported goods, such as tobacco, sugar, flour mills and beverages. Signed in 2004, the Agadir Agreement ( AA ) promotes free trade between Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Jordan.

Beyond improving trade flows between these regional partners, the AA contributes to the coordination of sectoral policies and the alignment of legislation. The AA uses EU rules of origin and allows its partners to accumulate added value to benefit from preferential tariffs. Geographical proximity has also been decisive since it has led to an expansion of trade flows. Morocco has also experienced growth in exports of meat, fish and other processed food preparations. In addition, the AA countries have reaped the benefits of their strategic positioning, which has led to the signing of bilateral agreements with other economies. On the other hand, the instability of the MENA region (

particularly in Libya ) persists, thus providing an opportunity for Asian countries and Turkey to compete for prosperous export markets. Since 2012, the EU and Morocco have concluded an agreement on further liberalization of trade in agricultural products

11.

Today, nearly two-thirds of Moroccan agri-food exports ( 63% ) are intended exclusively for the European market, of which more than 73% are fresh products such as fruits and vegetables. The proximity of the market and the increase in imports of fruit, vegetables and fish products in Europe justifies this upward trend. As regards processed agri-food products, 55% of exports are destined for third countries. It should be noted that Morocco has a positive agri-food trade balance with the EU ( 0.3 billion euros ).

Compliance with food safety and quality standards impacts unconditional access to the EU market. Food producers and processors are struggling to fully exploit the opportunities of this market despite its proximity. EU standards for food and feed safety, and in terms of sanitary, phytosanitary and environmental quality defined in the Community acquis, pose a challenge for exporters. The example of tomatoes and fertilizers illustrates how the protective measures taken by Morocco's trading partners prevent full access to these highly demanding markets. Traceability is another requirement introduced within the EU, which requires the ability to track food, compound feed and ingredients through all stages of production, processing and distribution.

Morocco has the strongest comparative advantage ( CA ) for vegetables, fruits and fish products. As the vegetable value chain is one of the largest contributors to the value of agricultural production, it also has by far the highest CA, with a value of almost 12. Vegetables are also the main product of export of the Moroccan agricultural sector, with a value of 1.350 million dollars in 2019, or more than 21% of the total value of Moroccan agri-food exports. Since 2015, vegetable exports have increased, showing CA growth of 16% over the past 5 years. Fruit is the second most important export product. With a contribution of 21% to total agri-food exports, the fruit value chain brings in $1.343 million to the Moroccan economy. While the AC of fruit exports corresponds to a value of nearly 7, it has shown a growth rate of 28% for the past 5 years. The fisheries value chain ( fish, crustaceans and molluscs ) achieves an export turnover of approximately 2.015 million dollars or 19% of total agri-food exports. However, in terms of competitiveness, the fishing industry has lost ground over the past 5 years, registering a decline of 18% for fresh fish and 8% for processing.

Harvesting growth - unveiling morocco's agrifood industries

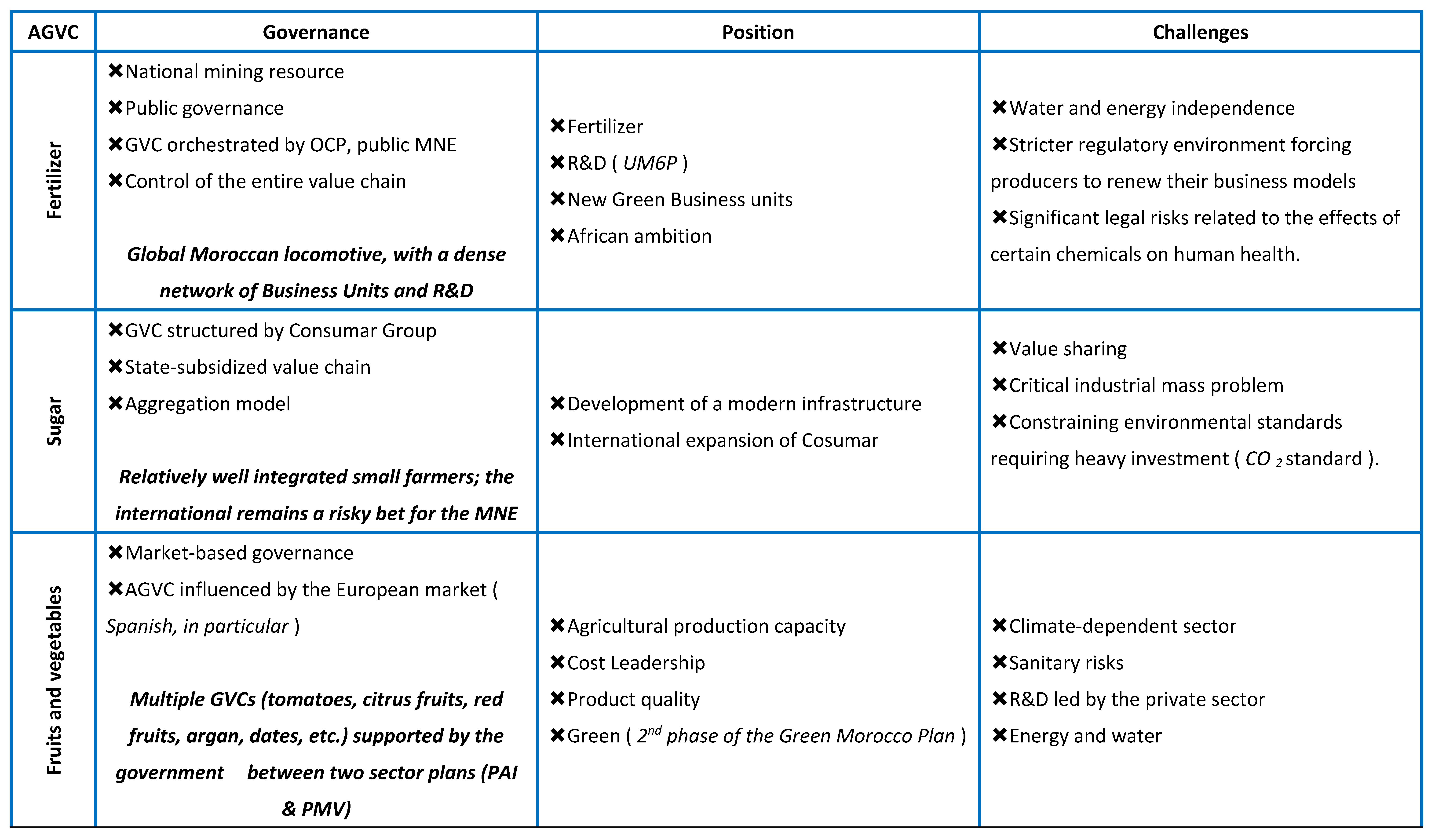

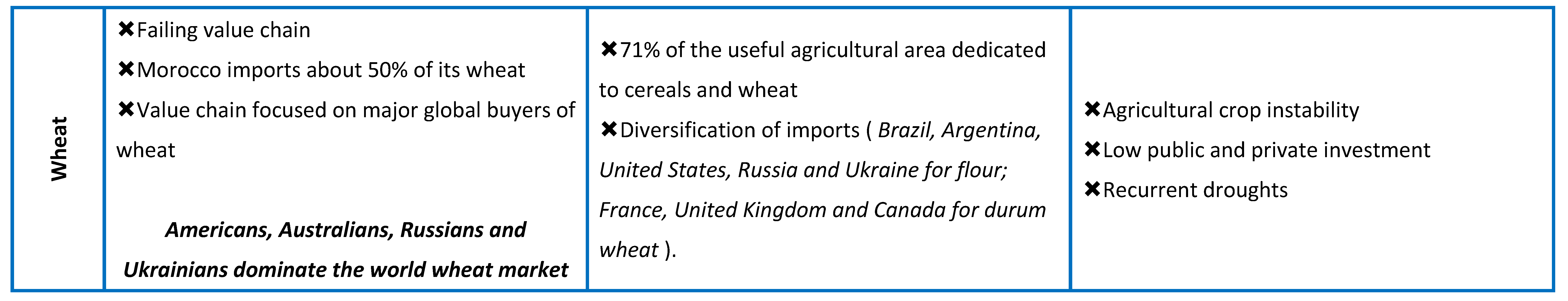

In this part, we have chosen to study these four AGVCs because of their importance but also because of their very different positioning:

- (1)

The Kingdom of Morocco is a major player in the international phosphate market. The country holds more than 75% of the world's phosphate rock reserves, which allows it to ensure production over several centuries. The Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP), which is the company that controls the entire phosphate and fertilizer value chain, has in the past set up a vast investment program (20 billion dollars) in two phases, one of the pillars of which is R&D. Consequently, Morocco is the world's leading producer and exporter of phosphates and phosphoric acid. OCP is also one of the largest fertilizer producers in the world. The establishment of the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University represents OCP's new vision in favor of R&D as a new growth engine for the company. However, the gap between the OCP infrastructure and the local infrastructure poses a problem. Added to this is the growing risk posed by the lack of water on the value chain, the need to accelerate the Group's energy and ecological transition, not to mention the commercial tensions characterizing the fertilizer industry. At the international level, the OCP group has succeeded in becoming more integrated, as illustrated so well by the partnership with the American multinational Koch Ag & Energy Solutions. Even more recently, OCP presented its new and very ambitious green investment program, which aims to meet water and energy challenges.

- (2)

The sugar industry, another strategic sector for the kingdom, must meet radically new industrial, social and environmental challenges. The Cosumar Group is a national champion in the food industry. The company controls all the links in the sugar value chain, and its local aggregation model has even aroused the interest of the FAO. Cosumar must now reduce its carbon footprint and find suitable financing for its program to increase production capacity and internationalization, all in an uncertain and complex global context.

- (3)

Morocco controls all of the world's argan reserves. However, the country cannot manage the entire value chain sustainably and positively. Between rights holders, intermediaries and global brands, Morocco's policy remains marked by low added value and a lack of innovation. Nevertheless, this global value chain represents a major opportunity for the National Agency for the Development of Oasis and Argan Zones ( ANDZOA ) to disseminate good sustainable development practices and test new social and transformation innovations. territories, on the condition that breeders, local populations and ecotourism operators are not opposed.

- (4)

Despite the efforts made by the Green Morocco Plan in the past, the country imports more than 50% of its cereal needs. Morocco has succeeded in diversifying its partners internationally, but private investment has little means and ambition to attract the major cereal locomotives and thus guarantee its food security. In 2021/2022 ( drought year ), the cereal campaign recorded a 67% drop in production compared to 2020/2021. Water stress is now becoming a constant reality for this value chain, which is also impacted by the surge in prices caused by the crisis in Ukraine.

Innovation and cooperation are key requirements for developing and maintaining competitive advantage along global value chain networks. Participation in a GVC can help the country and national agricultural SMEs in their process of improving product quality and developing value-added tasks.

However, the agricultural and agri-food value chains are multiple, and their operating models are just as diverse. It is, therefore, important that the stakeholder involved in a GVC properly assesses its scaling capabilities and chooses a value chain with the same shared values and interests. On the one hand, it is necessary to start from the conviction that the overall performance of a global agricultural and agri-food value chain is closely linked to the positive and lasting impact that production and product development operations must generate on the territories. where MNEs and their subsidiaries operate. On the other hand, AGVCs must imperatively act for fair and innovative use of resources and integrate ESG as a lever for the overall performance of the value chain.

The AGVCs are now led by international locomotives through which local producers are suppliers of raw materials. These locomotives are often multinationals or supermarket chains that rarely create joint ventures with Moroccan companies. Local agricultural SMEs are often only involved as suppliers or traders. Although this situation is not new, it still raises many concerns about the country's ability to capture value addition and exploit the sustainable stages of value chains.

From now on, the main challenge for the agricultural SME or the cooperative is to gradually move upmarket, going from the role of supplier of raw materials to that of partner in a JV, to then create national and regional locomotives. This observation is particularly true in the case of export sectors with high added value, such as citrus fruits, red fruits, early vegetables and avocado.

Although the Agrifood value chain in Morocco is backed by volatile agricultural production, we have national champions such as the OCP Group, the Cosumar Group, Lesieur, COPAG Jaouda, etc. While they all benefit from access to resources, specific assets and public aid, very few take the lead in their GVC like OCP in the fertilizer and phosphate industry.

The argan value chain is a remarkable illustration of the lack of control of an endemic national resource, the two ends of this chain, namely R&D, marketing and development, being controlled by foreign brands.

Considering the four case studies analyzed here, it appears that AGVCs governed by national actors ( OCP and Cosumar ) or by global brands and global retail and MNE multinationals ( case of L'Oréal for argan and supermarkets for fruit and vegetables ) are adopting two complementary initiatives to implement their shared value strategies:

- (1)

An industry initiative through the establishment of a purchasing process and another of local content dedicated to farmers and SME companies and,

- (2)

A societal initiative with agricultural programs aimed for small farmers, rural women and young rural entrepreneurs.

Thanks to the control of an essential mining resource, OCP has succeeded in an industrial transformation allowing it to transition to high value-added products ( fertilizers and compound feed).

Thus, R&D becomes a strategic area of activity for the Group. In the case of the sugar industry, the internationalization of Cosumar has given rise to a more integrated and competitive industrial group. Key infrastructures such as agropoles, the Tangier Med port and the LGV form the backbone of these value chains.

Table.

Different AGVC governance models in Morocco.

Table.

Different AGVC governance models in Morocco.

We have observed how the gradual evolution of Morocco's participation in AGVC has strengthened the local market. The fruit and vegetable ecosystem is a good example of this and shows how an export policy could support both domestic consumption and the kingdom's food security. We also analyzed how the OCP Group has successfully innovated by implementing an agile ecosystem around phosphates and fertilizers.

OCP also established the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University to become the new engine of growth for the phosphate and fertilizer industry. This modern university hosts laboratories that can train future engineers and researchers of certain AGVCs like wheat and seeds. Our approach allowed us to study the integration of Morocco in the AGVC from the four complementary experiences ( fertilizers, fruits and vegetables, sugar and argan ) and to identify the favorable and unfavorable factors of the local and global dynamics ( similarly as well as their social, economic and environmental consequences ).

Thanks to this, we demonstrate how the mobilization of international and national actors around a long-term vision has been favorable in the case of Morocco. The strengthening of the strategic state, trust, motivation of stakeholders, agro-industrial flexibility, diversification of customers and suppliers, national solidarity and the exemplary collaboration of Moroccan industrialists have made Morocco a resilient and stable country on the food plan during the difficult period of the pandemic.

The challenge of Morocco's integration policy in the AGVCs is therefore to place itself as close as possible to the stakeholders, their needs and their expectations in order to make the most of them, to act and work mutually on the issues of ESG, value sharing and innovation. More recently, the impact of the conflict in Europe, the Covid-19 pandemic and the interdependencies between links and actors have made it more than necessary to change the rules of the game which would be based on participatory and sustained tripartite governance (government , business and civil society ).

The emergence of the kingdom in AGVC must create lasting value while respecting the environment. The skills and resources of MNEs and agricultural estates should be put at the service of the local agricultural industry. This new framework for Morocco's participation in AGVCs must guarantee its partners the best quality/price ratio for products and services, maximum collective well-being ( stakeholders and local communities ), and sustainable use of resources.

Accordingly, the challenge of participating in sophisticated GVCs offers Morocco the opportunity to trigger all national initiatives and co-build innovative agrifood systems over time. The country needs to broaden its current participation framework to include all stakeholders.

OCP Group's experience offers the first elements of broad and sustainable governance. It also seems relevant to us to study the projection of these experiences in Africa by the Group, on the dimensions of governance and societal contribution ( well-being of stakeholders and local communities ). Finally, despite government support, the food value chains of wheat, fruits and vegetables and argan remain dominated by international buyers and large retailers. Moroccan companies, which appear above all as suppliers of raw materials, must find the industrial critical mass and improve the quality of products in these hypercompetitive contexts.

Conclusion and reflections: standards, scarcity, and beyond - unraveling the impacts

A global value chain integrates a set of actors in a production process. The main goal is to divide the work and create a final added value through intermediate added values, each actor being focused on a specific business. These value chains are driven by structuring operators called 'prime contractors' around which are articulated layers of equipment manufacturers of different ranks as well as the entire subcontracting chain required to achieve the final product. ( Amachraa A., and Quélin B, 2022 ).

Global agricultural and agri-food production is relatively well integrated into global value chains. Globally, 21% of the value of agri-food products exported by a given country was embodied in goods and services produced in other countries. Services are an increasingly important component in agrifood value chains, accounting for around 25% of total value added in agricultural exports and 35% of agrifood exports ( OECD, 2020; Amachraa A., & Maad H., 2023).

These AGVCs are instrumentalized by multinationals and retail chains around a small number of global hubs such as China, the United States and Europe. Nevertheless, the markets for these GVCs are protected by very strict health standards, essential labels and public aid. The example of global tomato and fertilizer value chains shows us how these protective barriers imposed by Morocco's trading partners prevent access to European and American markets ( Humphrey J. & Memedovic O., 2006; CNUCD, 2016; Amachraa A., & Maad H., 2023 ).

Moroccan agricultural and agri-food production is hindered by protective barriers imposed by some trading partners, preventing full access to the EU and US markets. Now, it is necessary to comply with standards driven by three concerns: food safety and consumer health, fair use of resources, and minimizing environmental impacts, as well as engaging stakeholders.

Global agricultural and agri-food production is well integrated into international value-added trade but is protected by stringent sanitary standards, essential labels, and public subsidies. The example of frequent tensions in the tomato and fertilizer trade illustrates how protective barriers imposed by some trading partners prevent full access to the European Union (EU) and US markets. The trend of restricting access to resources (water, fertilizers, and technologies primarily) and markets will continue in the future for the global agriculture and food value chain. Therefore, national economies and agricultural and food companies will have to comply with an increasing number of standards driven by three concerns: food safety and consumer health, fair use of resources and minimizing environmental impacts, and stakeholder motivation and commitment.

In this context, we have identified three trends. First, the problem of access to water resources, energy and fertilizers ( NPK ) is a major obstacle to the stability of global agricultural value chains as well as to Morocco's economic growth. Secondly, the markets for food products are growing strongly but their access is more or less difficult for health and protectionist reasons. Quality standards are a major trend in global agricultural value chains, although they are perceived as real taxes payable by producers and consumers. Thirdly, the Mass Markets Distribution are a rapidly growing and attractive model for producers and consumers ( modernity, quality, price, variety of supply, attractive promotions, means of payment, etc. ). The internal market is also buoyant, provided that it is regularly supplied with products of good quality/price ratio.

In the study titled "Agricultural Global Value Chains in Turmoil: Risks and Opportunities for Agriculture and Food" published in the Policy Center of the New South, we delved into the vulnerability of the agricultural sector by proposing a framework to understand this vulnerability as a function of adaptive capacity in the face of shocks and potential impacts arising from the fragmentation of the global production process and the interdependence of geographically dispersed actors (Amachraa A. and Maad H., 2023). We introduced a new paradigm centered around three core values:

-

Global community: Integrating a global value chain in the agriculture and food sector is the response of a network of agricultural countries and MNEs to a global social demand such as climate change mitigation/adaptation and food security. It is a matter of supporting collective dynamics and breaking with the individualism of previous programs for food security and adaptation to climate change.

-

Responsibility : Integrating a GVC is a way of guaranteeing its stakeholders agricultural products and services at the best quality/price ratio to ensure maximum well-being with the fairest use of resources (water, fertilizer and technology as a priority) . ).

-

Innovation: Integrating a GVC is finally a way of always encouraging R&D and reflection for solutions to the challenges of tomorrow: agro-industrial, social and environmental.

Successive crises impact the standardization process

These restrictions result from the ongoing dual crisis of energy and the military conflict in Ukraine, which "significantly hampers processes that were developing in the post-Covid-19 era." This "fragile and tumultuous" context brings about high uncertainties, highlighting that it is still difficult to predict the future developments of Global Value Chains (GVC): fragmentation due to scarcity effects along supply chains or regionalization with a redirection of investment flows and organization of production unit locations to reduce Western countries' dependence.

Furthermore, global agricultural value chains are systematically confronted with multinational corporations' desire to reorganize more regionally and the ambition of several countries to produce and capture more value-added, particularly by making efforts to promote green investments and greater national autonomy.

Agri-food sector: Increased volatility in production, income, and prices

In this tumultuous and uncertain context, uncertainty also affects Morocco. However, the structural elements of agricultural public policy and national priorities are present, and the directions are clear. In addition to these advantages, the Moroccan agri-food sector has the strongest competitive advantage for vegetables and fruits, and the government plays a regulatory role by controlling prices and providing subsidies to farmers and industrialists. However, this sector is characterized by "increased volatility in production, income, and prices." This volatility is due to chronic droughts and suboptimal use of production factors and technologies. Furthermore, complying with food safety and quality standards also has an impact on access to European and American markets.

To address these challenges, our study proposes policy options and adaptation measures "with a view to increasing the resilience of Agricultural Global Value Chains (AGVC) and reducing productivity, price, and income vulnerability." These options and measures include promoting resilient and sustainable agriculture, reducing water-consuming crop areas, targeting harvested yields rather than cultivated areas to improve agricultural value chain productivity and profitability, and recalibrating financing and investment toward sustainable and innovative value chains.

Impacts on four industries in Morocco: fertilizers, sugar, fruits and vegetables, and wheat

This study focuses on four industries in Morocco: fertilizers, sugar, fruits and vegetables, and wheat. These industries are considered "well representative" of Morocco's agricultural and agri-food sector, excluding the informal sector. These four value chains have structural characteristics that effectively illustrate value creation mechanisms and food security. In the future, the energy and water sectors will also be covered.

Thanks to strict control of the phosphate and fertilizer value chain by the OCP Group, the Kingdom of Morocco is a key player in global food security. The group's strength lies in its focus on R&D, enabling it to address radically new industrial, social, and environmental challenges, as well as the development of a dense network of new green business units. The recent green investment by OCP in water desalination and solar energy production is unprecedented.

Cosumar Group, another national driving force, has successfully implemented a model aggregation plan recognized by the FAO. This has allowed small farmers to be relatively well integrated into the sugar production and value chain. However, its international investment plan is a risky bet for Morocco due to a lack of critical industrial volume.

The multiple value chains of fruits and vegetables (tomatoes, citrus fruits, watermelon, berries, argan, dates, avocado, etc.) are supported by the state and intersect with two national sectoral plans (Industrial Acceleration Plan and Generation Green). However, water stress and market access conditions greatly hinder the development of these AGVCs. The study also indicates that the global argan value chain, an endemic species in Morocco, has not achieved notable success, with international brands capturing the majority of the added value.

Navigating Morocco's Vulnerability to International Market Prices

Despite efforts to diversify cereal suppliers and establish a strategic stock, the study reveals that Morocco remains vulnerable to international market prices and continues to import over 50% of its wheat needs. Americans, Australians, Russians, and Ukrainians dominate the global wheat market.

The sustainable development of Moroccan agriculture integrated into GVCs must create constant and positive value while respecting the environment. One potential solution is to limit financing for water-intensive and energy-consuming crops. Additionally, a system of green investment credit and ESG impact for agricultural value chains could be established, rewarding agricultural and non-agricultural areas for their civic engagement. Similarly, green land rehabilitation aimed at developing integrated agricultural projects targeting rural entrepreneurship, cereal production, and the establishment of a strategic food stock would be encouraged and rewarded.

List of abbreviations and acronyms

| ADA |

Agricultural Development Agency |

| AGVC |

Agricultural Global Value Chains |

| AKIS |

Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems |

| ESEC |

Economic, Social and Environmental Council |

| UNCTAD |

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development |

| ENA |

National School of Agriculture |

| ESG |

Environmental, Social, & Corporate Governance |

| FFS |

Farmer Field Schools |

| GCC |

Global Commodity Chain |

| EIG |

Economic Interest Groups |

| GPN |

Global Production Networks |

| GVC |

Global Value Chain |

| INRA |

National Institute of Agronomic Research |

| IPM |

Integrated Pest Management |

| JV |

Joint Ventures |

| NARS |

National Agricultural Research System |

| NICT |

New information and communication technologies |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| ONCA |

National office of agricultural advice |

| ONSSA |

National Office for Food Safety |

| UN |

United Nations Organization |

| SME |

Small and medium enterprises |

| R&D |

Research and Development |

| RAAKS |

Rapid Appraisal of Agricultural Knowledge Systems |

| CSR |

Corporate Social Responsibility |

| UAA |

Useful agricultural area |

| ICT |

Information and communication technologies |

| EU |

European Union |

| UM6P |

Mohammed VI Polytechnic University |

| WTO |

World Trade Organization |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

According to data from the FAO and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, a limited number of multinational corporations (MNEs) have control of global agricultural and agrifood value chains, from production, to trading and then to distribution. sales, processing and marketing. For example, four MNE companies are estimated to control 90% of the world grain trade. Similarly, 10 large companies drive 70% of the tomato value chain. The four major players in the cocoa markets of Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria bought more than half of the crops. Nearly 50% of the global banana trade is orchestrated by two MNEs. It is estimated that four companies in the coffee industry provided 45% of the global processing while only three MNEs controlled 80% of the tea market. |

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

According to FAO (1996), food security is achieved when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life. |

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

Climate Variability, Drought, and Drought Management in Morocco's Agricultural Sector, 2018. |

| 9 |

Eurostat, 2021. |

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

European Commission: Agreement in the form of an exchange of letters between the EU and Morocco concerning reciprocal liberalization measures for agricultural products - Official Journal of the European Union, L 241/4, 7.9.2012. |

References

- Akesbi N. (2013). Does Morocco's new agricultural strategy herald the country's food insecurity? The Harmattan | “Mediterranean Confluences” 2011/3 No. 78 | pages 93 to 105.

- Akesbi N. (2022). “Even today, we are in an agricultural economy that depends on rain and good weather”. CFCM, conjuncture.info.

- Allison et al. (2009) Vulnerability of national economies to the impacts of climate change on fisheries, Fish and Fisheries, 2009.

- Amachraa, A., and Hassna, M. (2023). Chaînes Globales de Valeur Tourmentées : Risques et Opportunités pour l’Agriculture et l’Alimentation. Policy Center for the New South, RP01/23. https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/chaines-globales-de-valeur-tourmentees-risques-et-opportunites-pour-lagriculture-et.

- Amachraa, A., and Quélin, B. (2022). Morocco Emergence in Global Value Chains: Four exemplary industries. Policy Center for the New South, April 7/22. https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/morocco-emergence-global-value-chains-four-exemplary-industries.

- Ashby, J. A., & Sperling, L. (1995). Institutionalizing participatory, client-driven research and technology development in agriculture. Development and Change, 26(4), 753-770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1995.tb00573.x. [CrossRef]

- Bair, J., & Palpacuer, F. (2015). CSR beyond the corporation: Contested governance in global value chains. Global networks, 15(s1), S1-S19. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12085. [CrossRef]

- Barichello, R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Anticipating its effects on Canada's agricultural trade. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d'agroeconomie, 68(2), 219-224. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12244. [CrossRef]

- Bawden, R. J., & Packham, R. G. (1993). Systemic praxis in the education of the agricultural systems practitioner. Systems practice, 6, 7-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01059677. [CrossRef]

- Cardwell R. Ghazalian PL. (2020). Covid-19 and International Food Assistance: Policy proposals to keep food flowing. World Development Volume 135 , November 2020, 105059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105059. [CrossRef]

- CESE. (2014). Governance through integrated water resources management. Opinion of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council.

- Chambers, R. (2004). Participatory Rural Appraisal: Methods and Applications in Rural Planning: Essays in Honour of Robert Chambers (Vol. 5). Concept Publishing Company.

- Chambers, R., & Jiggins, J. (1987). Agricultural research for resource-poor farmers Part I: Transfer-of-technology and farming systems research. Agricultural administration and extension, 27(1), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0269-7475(87)90008-0. [CrossRef]

- Checkland, P. B., & Haynes, M. G. (1994). Varieties of systems thinking: the case of soft systems methodology. System dynamics review, 10(2-3), 189-197. DOI:10.1002/sdr.4260100207. [CrossRef]

- Chiche J. (2021). Peasant agriculture and food self-sufficiency, between legends and realities. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7iccSrf4K8c.

- Engel, P. G., & Salomon, M. L. (1997). Facilitating innovation for development: a RAAKS resource box. Facilitating innovation for development: a RAAKS resource box.

- Exchange Office. (2022). Multidimensional analysis of the evolution of the profile of Moroccan exporters.

- FAO. (2020). The state of agricultural markets and sustainable development: global value chains, smallholders and digital innovations in agricultural commodity markets.

- FAO. (2021). CFS Voluntary Guidelines on Food Systems and Nutrition. Committee on World Food Security.

- Fogel, A. (1991). Infancy: Infant, family, and society. West Publishing Co.

- Fosse J. & al. (2019). Making the common agricultural policy a lever for agroecological transition. France Strategy.

- Gereffi G. and Fernandez-Stark K. (2016). Global Value Chain Analysis. Duke, Social Science Research Institute.

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, TJ. (2005). The governance of global value chains. Global Value Chains and Development, 108-137.

- Greenville, J., K. Kawasaki and R. Beaujeu. (2017). “How policies shape global food and agriculture value chains”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 100, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Humphrey. J. (2006). Policy Implications of Trends in Agribusiness Value Chains. European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810601070704. [CrossRef]

- Jouve, P., & Mercoiret, M. R. (1987). La recherche-développement: une démarche pour mettre les recherches sur les systèmes de production au service du développement rural.

- Klassen, S., & Murphy, S. (2020). Equity as both a means and an end: Lessons for resilient food systems from COVID-19. World Development, 136, 105104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105104. [CrossRef]

- Kuper M. (2022). Water in Morocco: we must listen to the crisis. Media 24, November 13, 2022.

- Lee J., Gereffi G., and Beauvais J. (2012). Global value chains and agrifood standards: Challenges and possibilities for smallholders in developing countries. Prabhu Pingali, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA.

- Lewis, D. W. (2004). The innovator's dilemma: Disruptive change and academic libraries.

- Miller, C., & Jones, L. (2013). Financement des chaînes de valeur agricoles: outils et leçons. Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation.

- Norman, D. W. (2002). The farming systems approach: A historical perspective. In Presentation held at the 17th Symposium of the International Farming Systems Association in Lake Buena Vista, Florida, USA (pp. 17-20).

- OECD. (2020). “Global value chains in agriculture and food: A synthesis of OECD analysis”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 139, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Pretty, J. N., Guijt, I., Thompson, J., & Scoones, I. (1995). Participatory learning and action: A trainer’s guide.

- Rolling N. (2009). agrifood innovation systems. Innovation Africa: Enriching Farmers' Livelihoods. Amazon books.

- Timmer, C. P. (2015). Food security and scarcity: why ending hunger is so hard. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Tirivangasi, H. M. (2018). Regional disaster risk management strategies for food security: Probing Southern African Development Community channels for influencing national policy. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 10(1), 1-7.

- Tsakok I. (2021). Managing and Improving Food Security in Africa. UM6P Public Policy School / HEC. Feb. 26, 2021.

- Udmal P. and al. (2020). Global food security in the context of Covid-19: A scenario-based exploratory analysis. Progress in Disaster Science Volume 7 , October 2020, 100120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100120. [CrossRef]

- Wettasinha, C., van Veldhuizen, L., & Waters-Bayer, A. (2003). Advancing participatory technology development. Case studies on integration into Agricultural research, extension and education, IIRR/ETC Ecoculture/CTA, Silaang, Cavite, Philipppines.

- WTO. (2019). World Trade Report: The Future of Trade in Services. Postponement.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).