Submitted:

09 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling distribution model

2.2. Richness estimation for one assemblage based on integrated data

2.2.1. Chao’s lower bound estimators

2.2.2. Extension of Chao’s lower bound estimators for integrated data

2.2.3. Adjusted Lower bound estimator of species richness for integrated data

2.3. Regional richness estimation based on integrated data

2.4. Variance estimation

3. Results

3.1. Simulation study

3.1.1. For individual-based abundance sampling models:

- a.

- Abundance model 1, random uniform model (CV = 0.53): with , where is a random sample from a uniform distribution.

- b.

- Abundance model 2, broken-stick model (CV = 0.97): with , where is a random sample from an exponential distribution with parameter 1. This model is commonly used in the literature and is equivalent to the Dirichlet distribution.

- c.

- Abundance model 3, log-normal model (CV = 1.56): with , where is a random sample from a log-normal distribution with parameters 0 and 1.

3.1.2. For sample-based incidence sampling models

- d

-

Incidence model 1: the random uniform model (CV = 0.57): where , and is a random sample from a uniform distributionwith parameters (0, 1), and scale c is used to control the maximum of .

- e

- Incidence model 2: the broken stick model (CV = 0.99): where , and is a random sample from an exponential distribution with parameter 1, and scale c is used to control the maximum of . This model is commonly used in the literature and equivalent to the Dirichlet distribution.

- f

- Incidence model 3: the log-normal model (CV = 1.23): where , and is a random sample from a log-normal distribution, and scale c is used to control the maximum of .

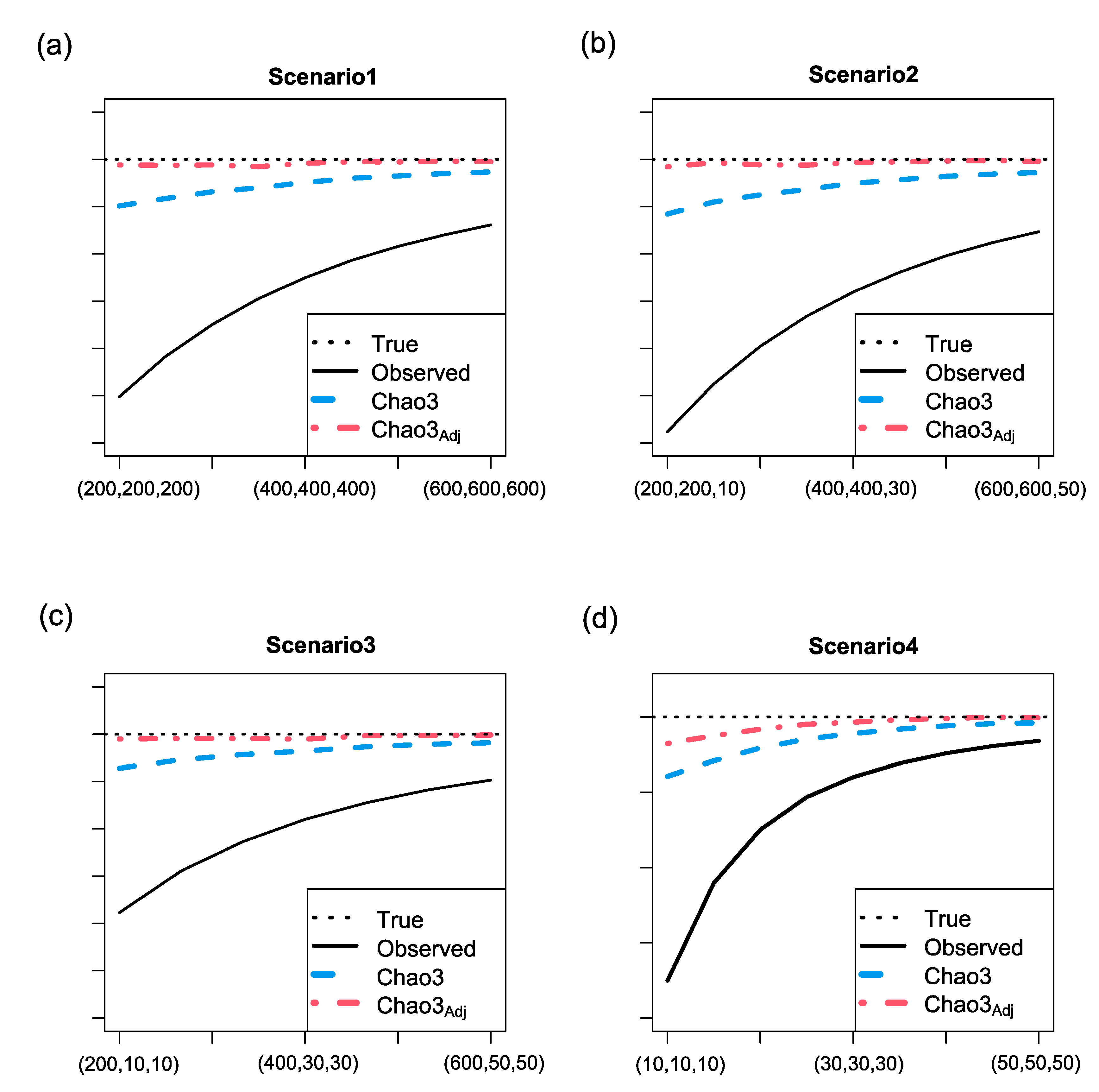

3.2. Simulation results for richness estimation of one assemblage (a local region)

- Three abundance models: random uniform, broken-stick, and log-normal.

- Two abundance models: random uniform and broken-stick, along with one incidence model: log-normal.

- One abundance model: random uniform, along with two incidence models: broken-stick and log-normal.

- Three incidence models: random uniform, broken-stick, and log-normal.

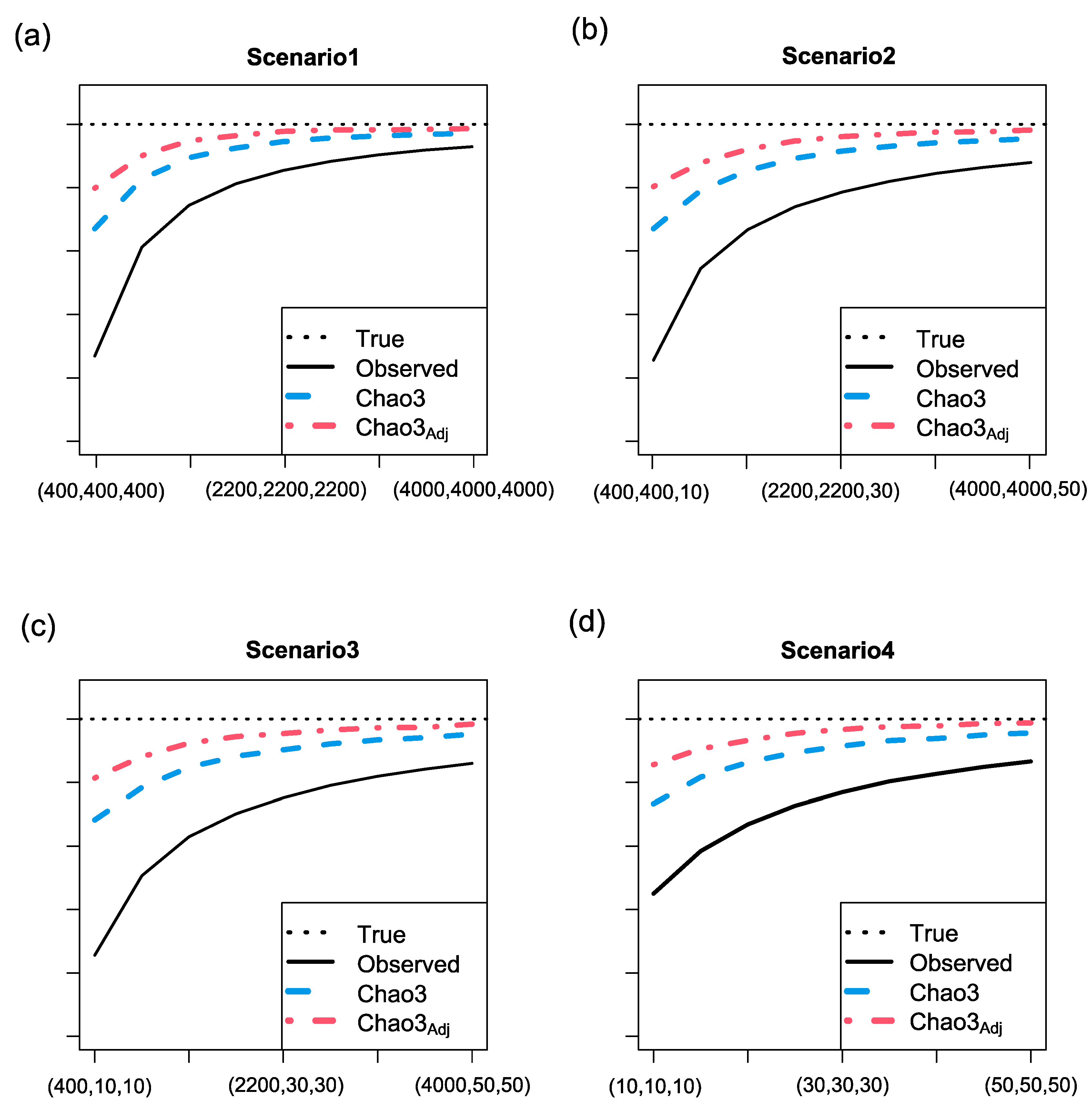

3.3. Simulation results for richness estimation of multiple assemblages (a large-scale region)

- Three abundance models: random uniform, broken-stick, and log-normal.

- Two abundance models: random uniform and broken-stick, along with one incidence model: log-normal.

- One abundance model: random uniform, along with two incidence models: broken-stick and log-normal.

- Three incidence models: random uniform, broken-stick, and log-normal.

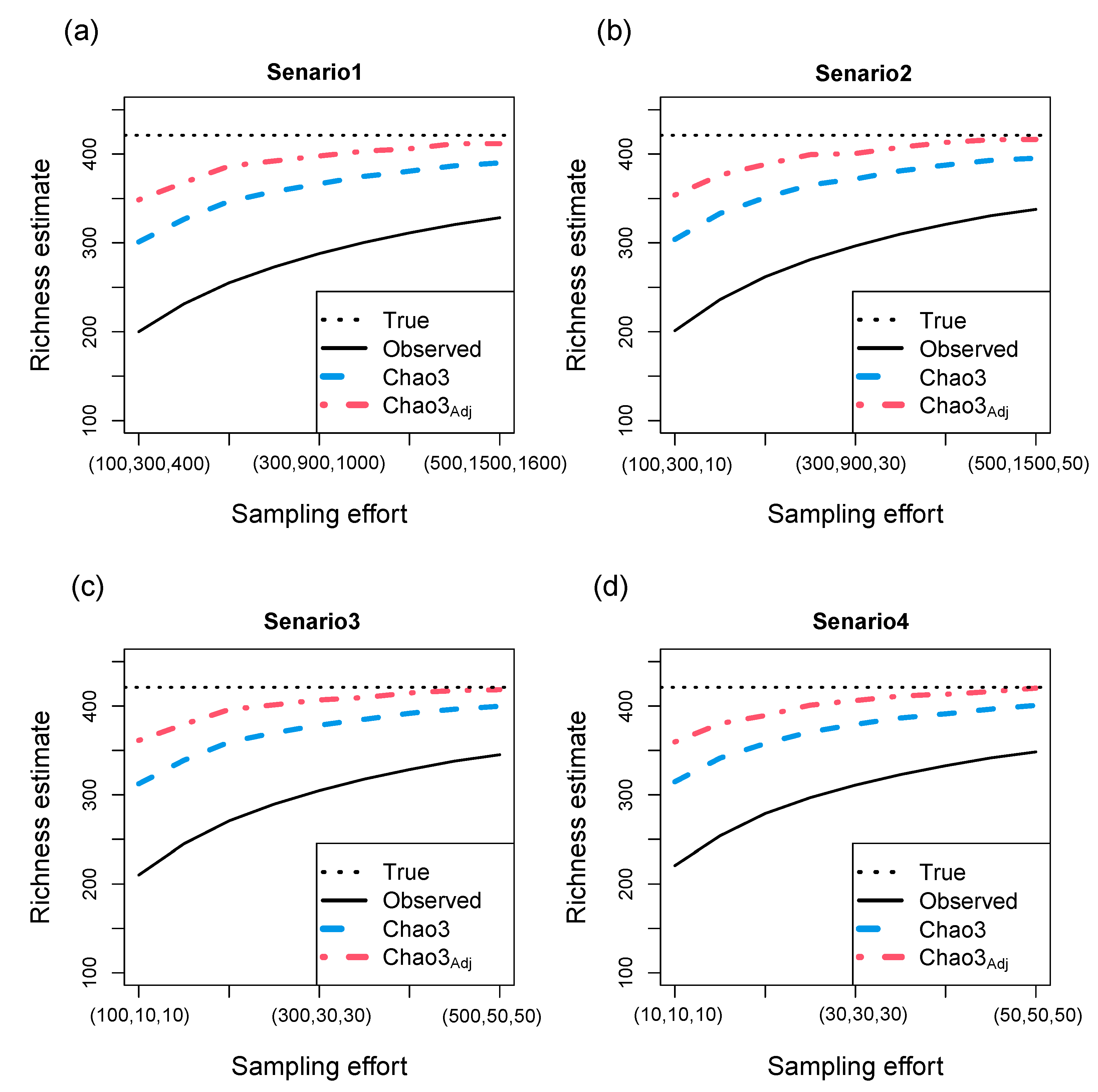

3.4. Using data sets as true assemblages

3.4.1. Moth species data

- Three abundance models: creek, slope, and ridge.

- Two abundance models: creek and slope, along with one incidence model: ridge.

- One abundance model: creek, along with two incidence models: slope and ridge.

- Three incidence models: creek, slope, and ridge.

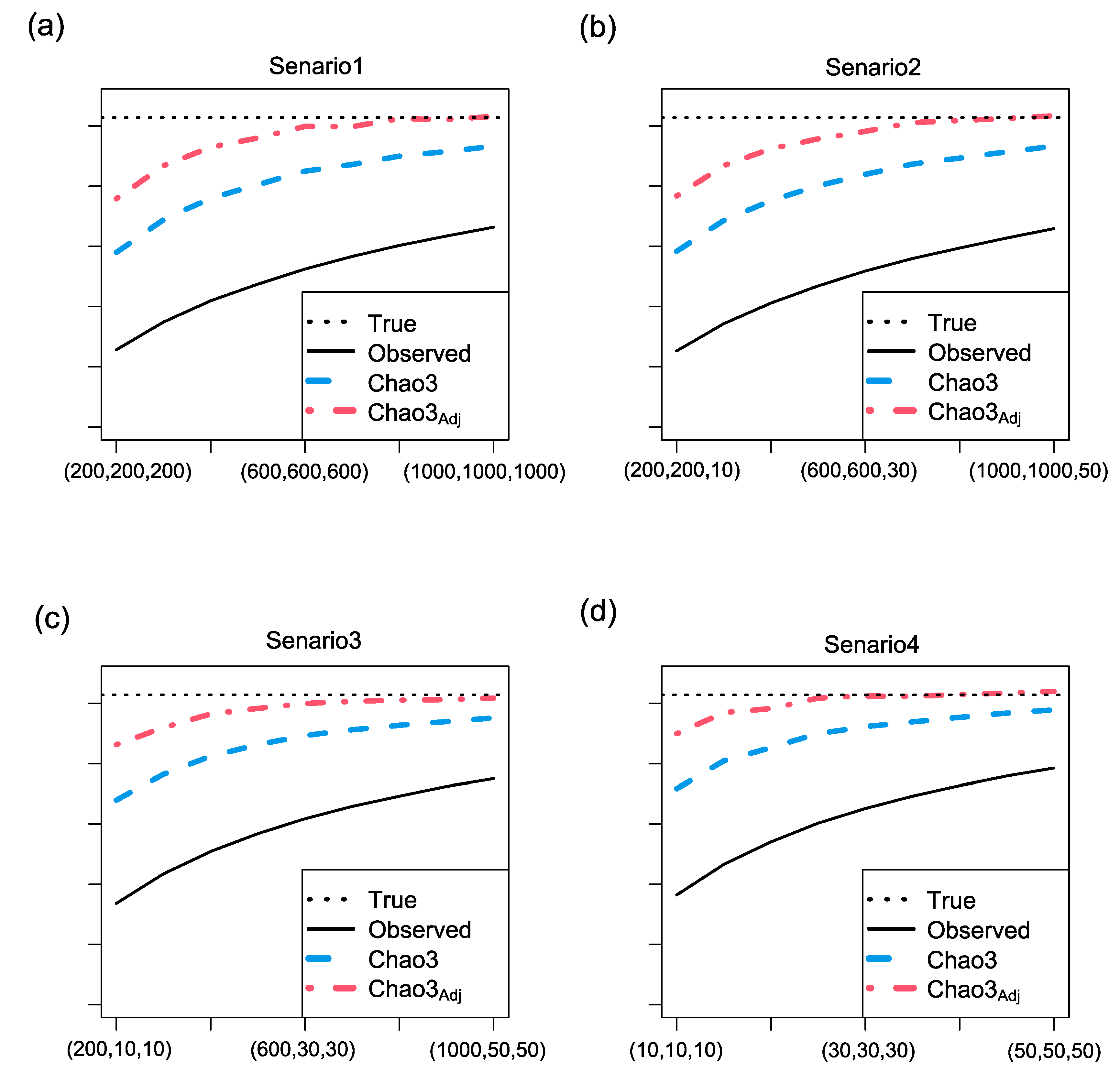

3.4.2. xylobiont beetle species data

- Three abundance models: QR, TC, and FE.

- Two abundance models: QR and TC, along with one incidence model: FE.

- One abundance model: QR, along with two incidence models: TC and FE.

- Three incidence models: QR, TC, and FE.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Numerical study to show that the expectation of species count of rare frequency in the pooled sample is approximately identical to the probability sum of Poisson distribution.

- a.

- For individual-based abundance sampling model, the species detection probabilities (or species relative abundance) , where is a normalizing constant such that .

- b.

- For sample-based incidence model, The species detection probabilities .

| Sample size | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59.4 | 65.1 | 43 | 23.4 | 14.3 | 13.6 | ||

| 55.6 | 66.9 | 44.8 | 22 | 8 | 3.2 | ||

| 21.9 | 39.9 | 42.8 | 35.8 | 25.7 | 16.3 | ||

| 20.2 | 39.2 | 43.3 | 37.4 | 27.1 | 17 | ||

| 9.4 | 22.4 | 30.5 | 32 | 29.3 | 24.4 | ||

| 8.5 | 21.5 | 30 | 32.5 | 29.9 | 25.7 | ||

| 4.4 | 12.8 | 20.5 | 24.7 | 25.6 | 24.3 | ||

| 4 | 12 | 20 | 24.5 | 25.4 | 24.8 | ||

| 2.2 | 7.4 | 13.7 | 18.4 | 20.7 | 21.2 | ||

| 1.9 | 6.9 | 13.1 | 18.1 | 20.6 | 21.2 |

Appendix B: The summary of the statistical properties of the richness estimators discussed in the text.

| Available data and Notation | Richness estimator | Pluses and minuses |

| Individual-based abundance data: sampling unit is an individual randomly selected from target assemblage and identified to species Sobs: the observed richness. f1: the singleton richness in the sample f2: the doubleton richness in the sample . f3: the tripleton richness in the sample |

Chao1[6] |

1. A lower bound estimator of richness for all species composition models. 2. A nearly unbiased estimator when rare species are homogeneous 3. Has severely negative bias when community is highly heterogeneous. |

| Chao1Adj[19] |

1. A lower bound estimator of richness for Gamma-Poisson models. 2. Compare to , has less bias, higher variance, lower RMSE, and has more accurate coverage rate of 95% confidence interval. |

|

| Sample-based incidence data: sampling unit is a quadrat or plot and only the incidence of species appearing in the selected plot is recorded . Sobs: the observed richness. Q1: the singleton richness in the sample. Q2: the doubleton richness in the sample. Q3: the tripleton richness in the sample/ t: the number of selected plot. |

Chao2[7] |

1. A lower bound estimator of richness for all species composition model. 2. A nearly unbiased estimator when rare species are homogeneous 3. Has severely negative bias when community is highly heterogeneous. |

| Chao2Adj[20] |

1. A lower bound estimator of richness for Beta-Binomial models. 2. Compare to , has less bias, higher variance, lower RMSE, and has more accurate coverage rate of 95% confidence interval. |

|

| Pooled sample of integrated data: directly pool the individual-based abundance data and sample-based incidence data as a new sample Sobs: the observed richness. G1: the singleton richness in pooled sample. G2: the doubleton richness in the pooled sample. G3: the tripleton richness in the pooled sample. |

Chao3 (New proposed) |

1. Chao3 is available for pooled sample of integrated data. 2. A lower bound estimator of richness when sample size is large enough. 3. Has severely negative bias when community is highly heterogeneous. |

| Chao3Adj(New proposed) |

1. Compare to , has less bias, higher variance and lower RMSE. 2. Has more accurate coverage rate of 95% confidence interval. |

Appendix C: Supplementary tables (Table A1 and Table A2)

| Size (Observed richness) |

Estimator | Average Estimate |

Bias | Sample SE |

Average Estimated SE |

Sample RMSE |

95% CI Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenerio1 | |||||||

| 100,300,400 (200.0) |

Chao3 | 301.6 | -119.4 | 30.4 | 29.4 | 123.2 | 0.158 |

| Chao3Adj | 350.7 | -70.3† | 57.8 | 56.8 | 91† | 0.85† | |

| 300,900,1000 (288.2) |

Chao3 | 367.6 | -53.4 | 22.1 | 22.4 | 57.8 | 0.49 |

| Chao3Adj | 399.1 | -21.9† | 39.6 | 41.7 | 45.2† | 0.926† | |

| 500,1500,1600 (328.2) |

Chao3 | 391.9 | -29.1 | 19.8 | 18.7 | 35.2† | 0.754 |

| Chao3Adj | 416.4 | -4.6† | 36.1 | 34.1 | 36.3 | 0.943† | |

| Scenerio2 | |||||||

| 100,300,10 (201.2) |

Chao3 | 303.7 | -117.3 | 30.1 | 29.5 | 121.1 | 0.18 |

| Chao3Adj | 353.4 | -67.6† | 58.3 | 56.9 | 89.2† | 0.846† | |

| 300,900,30 (297.3) |

Chao3 | 333 | -88 | 30.5 | 27.2 | 93.1 | 0.294 |

| Chao3Adj | 377.2 | -43.8† | 57.9 | 51.9 | 72.6† | 0.891† | |

| 500,1500,50 (338.4) |

Chao3 | 351.8 | -69.2 | 26 | 25.1 | 73.9 | 0.408 |

| Chao3Adj | 389 | -32† | 49 | 47.2 | 58.5† | 0.931† | |

| Scenerio3 | |||||||

| 100,10,10 (200) |

Chao3 | 310.2 | -110.8 | 29.4 | 28.8 | 114.7 | 0.186 |

| Chao3Adj | 357.1 | -63.9† | 56.3 | 54.8 | 85.1† | 0.846† | |

| 300,30,30 (288.2) |

Chao3 | 339.2 | -81.8 | 28.6 | 26.5 | 86.7 | 0.32 |

| Chao3Adj | 380 | -41† | 54.7 | 49.6 | 68.3† | 0.882† | |

| 500,50,50 (328.2) |

Chao3 | 357.2 | -63.8 | 24.5 | 24.3 | 68.3 | 0.4 |

| Chao3Adj | 393.7 | -27.3† | 46.5 | 45.9 | 53.9† | 0.942† | |

| Scenerio4 | |||||||

| 10,10,10 (221.1) |

Chao3 | 313.3 | -107.7 | 28.7 | 26.7 | 111.4 | 0.168 |

| Chao3Adj | 356.3 | -64.7† | 54.6 | 50.9 | 84.6† | 0.842† | |

| 30,30,30 (311.1) |

Chao3 | 341.3 | -79.7 | 25.4 | 25 | 83.7 | 0.286 |

| Chao3Adj | 379.5 | -41.5† | 47.6 | 47 | 63.1† | 0.911† | |

| 50,50,50 (348.0) |

Chao3 | 359.3 | -61.7 | 23.6 | 23.2 | 66 | 0.428 |

| Chao3Adj | 393.7 | -27.3† | 44.4 | 43.3 | 52.1† | 0.941† | |

| Size (Observed richness) |

Estimator | Average Estimate |

Bias | Sample SE |

Average Estimated SE |

Sample RMSE |

95% CI Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenerio1 | |||||||

| 200,200,200 (132.2) |

Chao3 | 212.3 | -94.7 | 29.9 | 29.1 | 99.3 | 0.321 |

| Chao3Adj | 253.7 | -53.3† | 59 | 56.2 | 79.5† | 0.856† | |

| 600,600,600 (196.4) |

Chao3 | 233.7 | -73.3 | 28.4 | 27.4 | 78.6 | 0.428 |

| Chao3Adj | 271.6 | -35.4† | 55.4 | 52.5 | 65.8† | 0.912† | |

| 1000,1000,1000 (228.1) |

Chao3 | 250 | -57 | 28.3 | 26.5 | 63.6 | 0.561 |

| Chao3Adj | 287.6 | -19.4† | 54.4 | 50.5 | 57.7† | 0.928† | |

| Scenerio2 | |||||||

| 200,200,10 (115.7) |

Chao3 | 199.1 | -107.9 | 34.6 | 31.8 | 113.3 | 0.287 |

| Chao3Adj | 245.9 | -61.1† | 69.2 | 62.3 | 92.3† | 0.841† | |

| 600,600,30 (181.3) |

Chao3 | 221.3 | -85.7 | 30.3 | 29.5 | 91 | 0.386 |

| Chao3Adj | 263.1 | -43.9† | 59.7 | 56.9 | 74.1† | 0.892† | |

| 1000,1000,50 (215.8) |

Chao3 | 238.3 | -68.7 | 30.3 | 28.3 | 75.1 | 0.497 |

| Chao3Adj | 278.8 | -28.2† | 59.7 | 54 | 66† | 0.912† | |

| Scenerio3 | |||||||

| 200,10,10 (127.5) |

Chao3 | 209.3 | -97.7 | 30.4 | 30 | 102.3 | 0.334 |

| Chao3Adj | 252.2 | -54.8† | 59.4 | 58.5 | 80.8† | 0.855† | |

| 600,30,30 (195.4) |

Chao3 | 232 | -75 | 29.1 | 27.8 | 80.5 | 0.43 |

| Chao3Adj | 269.9 | -37.1† | 57.1 | 52.9 | 68.1† | 0.885† | |

| 1000,50,50 (227.8) |

Chao3 | 245.5 | -61.5 | 26.4 | 25.3 | 66.9 | 0.504 |

| Chao3Adj | 278.4 | -28.6† | 50.4 | 47.7 | 57.9† | 0.929† | |

| Scenerio4 | |||||||

| 10,10,10 (141.1) |

Chao3 | 228.5 | -78.5 | 33.2 | 31 | 85.2 | 0.453 |

| Chao3Adj | 274.3 | -32.7† | 66.1 | 60.3 | 73.7† | 0.882† | |

| 30,30,30 (213.0) |

Chao3 | 251.5 | -55.5 | 27.9 | 28.5 | 62.2 | 0.613 |

| Chao3Adj | 291.2 | -15.8† | 55.1 | 54.3 | 57.3† | 0.916† | |

| 50,50,50 (246.2) |

Chao3 | 264.4 | -42.6 | 27.8 | 25.6 | 50.8† | 0.685 |

| Chao3Adj | 297.5 | -9.5† | 52.7 | 47.7 | 53.6 | 0.922† | |

References

- Bunge, J.; Fitzpatrick, M. Estimating the number of species: A review. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993, 88, 364–373. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R. K.; Coddington, J. A. Estimating terrestrial biodiversity through extrapolation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1994, 345, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chiu, C.-H. Species richness: estimation and comparison. Wiley StatsRef: statistics reference online 2016, 1, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R. M. a. C. M. F. M. Capture-recapture estimation with samples of size one using frequency data. Biometrika 1992, 79, 543–553. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A., Species estimation and applications. In Encyclopedia of statistical sciences, Balakrishnan, N.; Read, C. B.; Vidakovic, B., Eds. Wiley: New York, 2005; pp 7907-7916.

- Chao, A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Stat. 1984, 11 265-270.

- Chao, A. Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 1987, 43, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K. P.; Overton, W. S. Estimation of the size of a closed population when capture probabilities vary among animals. Biometrika 1978, 65, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P.; Overton, W. S. Robust estimation of population size when capture probabilities vary among animals. Ecology 1979, 60, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15(4), 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B. J.; Duffy, J. E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D. U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G. M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D. A. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486(7401), 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchioli, R.; Ripple, W. J.; Timmis, K. N.; Azam, F.; Bakken, L. R.; Baylis, M.; Behrenfeld, M. J.; Boetius, A.; Boyd, P. W.; Classen, A. T. Scientists’ warning to humanity: microorganisms and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17(9), 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F. T.; Reich, P. B.; Jeffries, T. C.; Gaitan, J. J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C. D.; Singh, B. K. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Good, I. J.; Toulmin, G. The Number of New Species and the Increase of Population Coverage When a Sample Is Increased. Biometrika 1956, 43, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, R. K.; Chao, A.; Gotelli, N. J.; Lin, S.-Y.; Mao, C. X.; Chazdon, R. L.; Longino, J. T. Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages. J. Plant Ecol. 2012, 5(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Chiu, C. H.; Colwell, R. K.; Magnago, L. F. S.; Chazdon, R. L.; Gotelli, N. J. Deciphering the enigma of undetected species, phylogenetic, and functional diversity based on Good-Turing theory. Ecology 2017, 98(11), 2914–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A.; Colwell, R. K., Thirty years of progeny from Chao's inequality: Estimating and comparing richness with incidence data and incomplete sampling. SORT: statistics and operations research transactions 2017, 41 (1), 0003-54.

- Chiu, C. H.; Wang, Y. T.; Walther, B. A.; Chao, A. An improved nonparametric lower bound of species richness via a modified good–turing frequency formula. Biometrics 2014, 70(3), 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-H. A more reliable species richness estimator based on the Gamma–Poisson model. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. H. Incidence-data-based species richness estimation via a Beta-Binomial model. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13(11), 2546–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A.; Lee, S.-M. Estimating the number of classes via sample coverage. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1992, 87, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Rabl, D.; Gottsberger, B.; Brehm, G.; Hofhansl, F.; Fiedler, K. Moth assemblages in Costa Rica rain forest mirror small-scale topographic heterogeneity. Biotropica 2020, 52(2), 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haack, N.; Grimm-Seyfarth, A.; Schlegel, M.; Wirth, C.; Bernhard, D.; Brunk, I.; Henle, K. Patterns of richness across forest beetle communities—A methodological comparison of observed and estimated species numbers. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11(1), 626–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Size (Observed richness) |

Estimator | Average Estimate |

Bias | Sample SE |

Average Estimated SE |

Sample RMSE |

95% CI Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenerio1 | |||||||

| 200, 200, 200 (352.3) |

Chao3 | 557.3 | -42.7 | 37.6 | 38.7 | 56.9† | 0.834 |

| Chao3Adj | 601.6 | 1.6† | 71.6 | 68.2 | 71.5 | 0.856† | |

| 400, 400, 400 (480.0) |

Chao3 | 582.1 | -17.9 | 21.4 | 20.9 | 27.8† | 0.882 |

| Chao3Adj | 601.6 | 1.6† | 35.7 | 34.1 | 35.7 | 0.87† | |

| 600, 600, 600 (536.2) |

Chao3 | 590.4 | -9.6 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 17.2† | 0.91 |

| Chao3Adj | 599.9 | -0.1† | 22.1 | 21.5 | 22.1 | 0.95† | |

| Scenerio2 | |||||||

| 200, 200, 10 (307.9) |

Chao3 | 548.8 | -51.2 | 50.1 | 46.8 | 71.6† | 0.804 |

| Chao3Adj | 598.2 | -1.8† | 93.2 | 82.1 | 93.1 | 0.890† | |

| 400, 400, 20 (441) |

Chao3 | 571 | -29 | 26.3 | 25.3 | 39.1† | 0.8 |

| Chao3Adj | 596.3 | -3.7† | 45.4 | 41.9 | 45.5 | 0.91† | |

| 600, 600, 40 (513.4) |

Chao3 | 584.9 | -15.1 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 22.6† | 0.858 |

| Chao3Adj | 598.8 | -1.2† | 27.4 | 26.4 | 27.4 | 0.932† | |

| Scenerio3 | |||||||

| 200, 10, 10 (330.8) |

Chao3 | 547.9 | -52.1 | 41 | 41.4 | 66.3† | 0.786 |

| Chao3Adj | 587.1 | -12.9† | 74.5 | 70.7 | 75.5 | 0.872† | |

| 400, 20, 20 (460.2) |

Chao3 | 572.1 | -27.9 | 22.6 | 22.4 | 35.9† | 0.814 |

| Chao3Adj | 593.6 | -6.4† | 39.6 | 36.9 | 40 | 0.902† | |

| 600, 40, 40 (538.5) |

Chao3 | 589.3 | -10.7 | 13.2 | 13.1 | 17† | 0.902 |

| Chao3Adj | 599.8 | -0.2† | 20.7 | 21.3 | 20.6 | 0.95† | |

| Scenerio4 | |||||||

| 10, 10, 10 (445.0) |

Chao3 | 570.1 | -29.9 | 24.7 | 24.2 | 38.8† | 0.808 |

| Chao3Adj | 589.4 | -10.6† | 41.8 | 38.2 | 43.1 | 0.88† | |

| 20, 20, 20 (540.5) |

Chao3 | 585 | -15 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 19.1† | 0.826 |

| Chao3Adj | 594 | -6† | 18.5 | 19.2 | 19.4 | 0.961† | |

| 40, 40, 40 (583.9) |

Chao3 | 596.3 | -3.7 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 7.1† | 0.954 |

| Chao3Adj | 599.6 | -0.4† | 9.1 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 0.952† | |

| Sizes (Observed richness) |

Estimator | Average Estimate |

Bias | Sample SE |

Average Estimated SE |

Sample RMSE |

95% CI Coverage Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenerio1 | |||||||

| 500, 500, 500 (457) |

Chao3 | 544.8 | -55.2 | 21.7 | 20 | 59.3 | 0.42 |

| Chao3Adj | 572.9 | -27.1† | 38.2 | 35.5 | 46.8† | 0.892† | |

| 1000, 1000, 1000 (529.4) |

Chao3 | 573.1 | -26.9 | 13.5 | 12.8 | 30.1 | 0.6 |

| Chao3Adj | 587.3 | -12.7† | 22.7 | 22.1 | 26† | 0.906† | |

| 2000, 2000, 2000 (569.5) |

Chao3 | 589.5 | -10.5 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 14.1† | 0.806 |

| Chao3Adj | 596.3 | -3.7† | 15.2 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 0.972† | |

| Scenerio2 | |||||||

| 500, 500, 10 (430.7) |

Chao3 | 518 | -82 | 20.1 | 20 | 84.4 | 0.13 |

| Chao3Adj | 545.7 | -54.3† | 34.7 | 35.4 | 64.4† | 0.786† | |

| 1000, 1000, 20 (502.5) |

Chao3 | 553.2 | -46.8 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 49.2 | 0.306 |

| Chao3Adj | 572.4 | -27.6† | 26.4 | 25.4 | 38.1† | 0.858† | |

| 2000, 2000, 400 (547.9) |

Chao3 | 580.2 | -19.8 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 23.7 | 0.694 |

| Chao3Adj | 593 | -7† | 22.1 | 20.6 | 23.2† | 0.942† | |

| Scenerio3 | |||||||

| 500, 10, 10 (452.6) |

Chao3 | 540.9 | -59.1 | 21.1 | 19.9 | 62.7 | 0.32 |

| Chao3Adj | 567.2 | -32.8† | 36.8 | 34.9 | 49.3† | 0.862† | |

| 1000, 20, 20 (524.9) |

Chao3 | 570.4 | -29.6 | 13.8 | 13.1 | 32.6 | 0.57 |

| Chao3Adj | 584.4 | -15.6† | 23.4 | 22.6 | 28† | 0.912† | |

| 2000, 40, 40 (566.4) |

Chao3 | 587.4 | -12.6 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 15.5 | 0.782 |

| Chao3Adj | 594.4 | -5.6† | 14.5 | 14.6 | 15.4† | 0.984† | |

| Scenerio4 | |||||||

| 10, 10, 10 (492.4) |

Chao3 | 553.4 | -46.6 | 18 | 16.6 | 50 | 0.41 |

| Chao3Adj | 575.3 | -24.7† | 31.6 | 29.3 | 40.1† | 0.886† | |

| 20, 20, 20 (541.8) |

Chao3 | 576.1 | -23.9 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 27 | 0.642 |

| Chao3Adj | 587.3 | -12.7† | 21.3 | 20.1 | 24.8† | 0.920† | |

| 40, 40, 40 (571.8) |

Chao3 | 588.3 | -11.7 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 14.1 | 0.806 |

| Chao3Adj | 594.2 | -5.8† | 12.8 | 13.4 | 14† | 0.976† | |

| Moth species data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat | SampleSize | Observed richness | SampleCV | ||||

| creek | 461 | 115 | 1.86 | 54 | 22 | 9 | 32 |

| slope | 2382 | 285 | 2.40 | 92 | 47 | 23 | 123 |

| ridge | 3710 | 356 | 2.68 | 94 | 59 | 31 | 172 |

| Beetle species data | |||||||

| Tree species |

SampleSize | Observed richness | SampleCV | ||||

| Quercus robur | 2205 | 174 | 2.72 | 74 | 29 | 10 | 61 |

| Tilia cordata | 1737 | 198 | 2.37 | 92 | 27 | 16 | 63 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | 1797 | 184 | 3.30 | 77 | 31 | 11 | 65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).