Submitted:

05 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

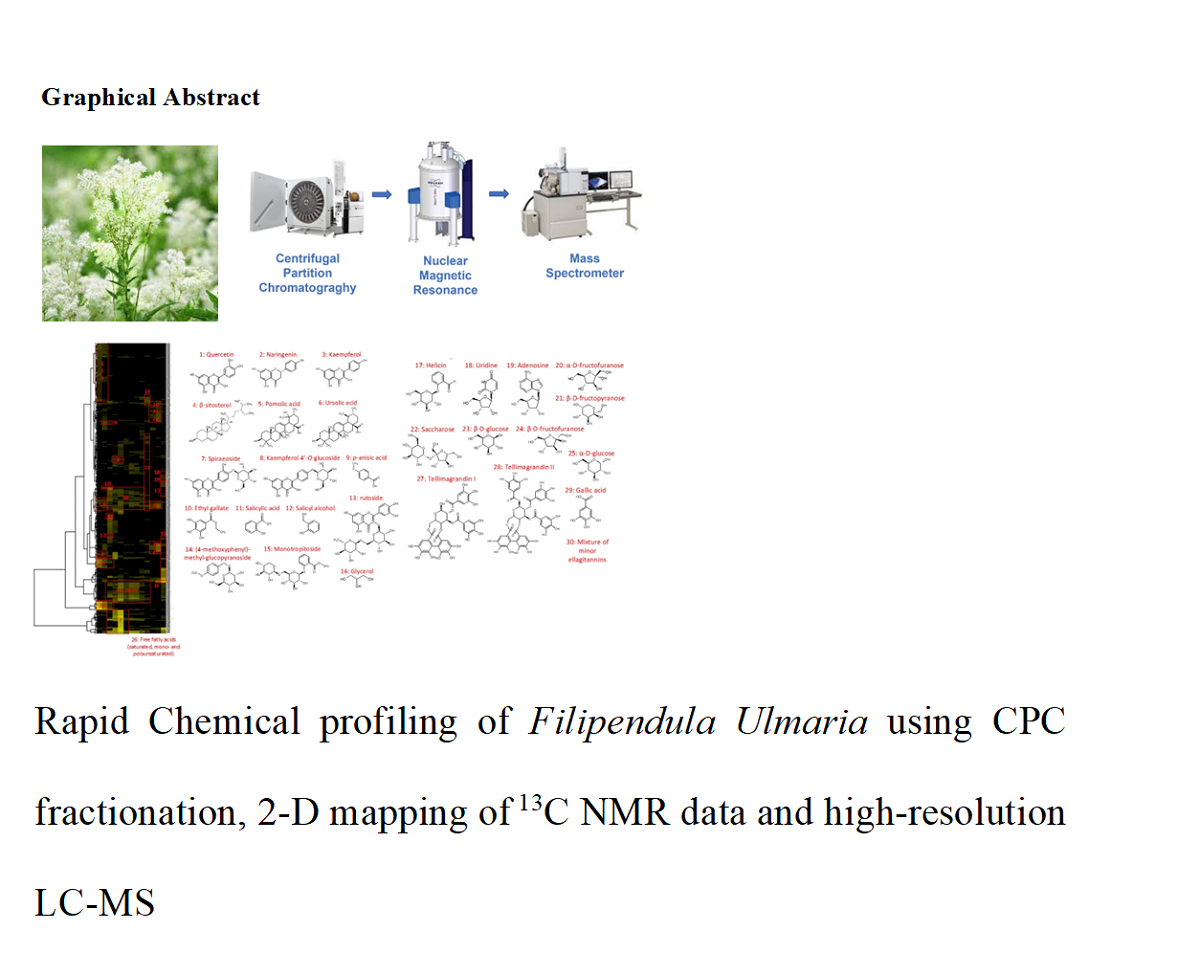

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

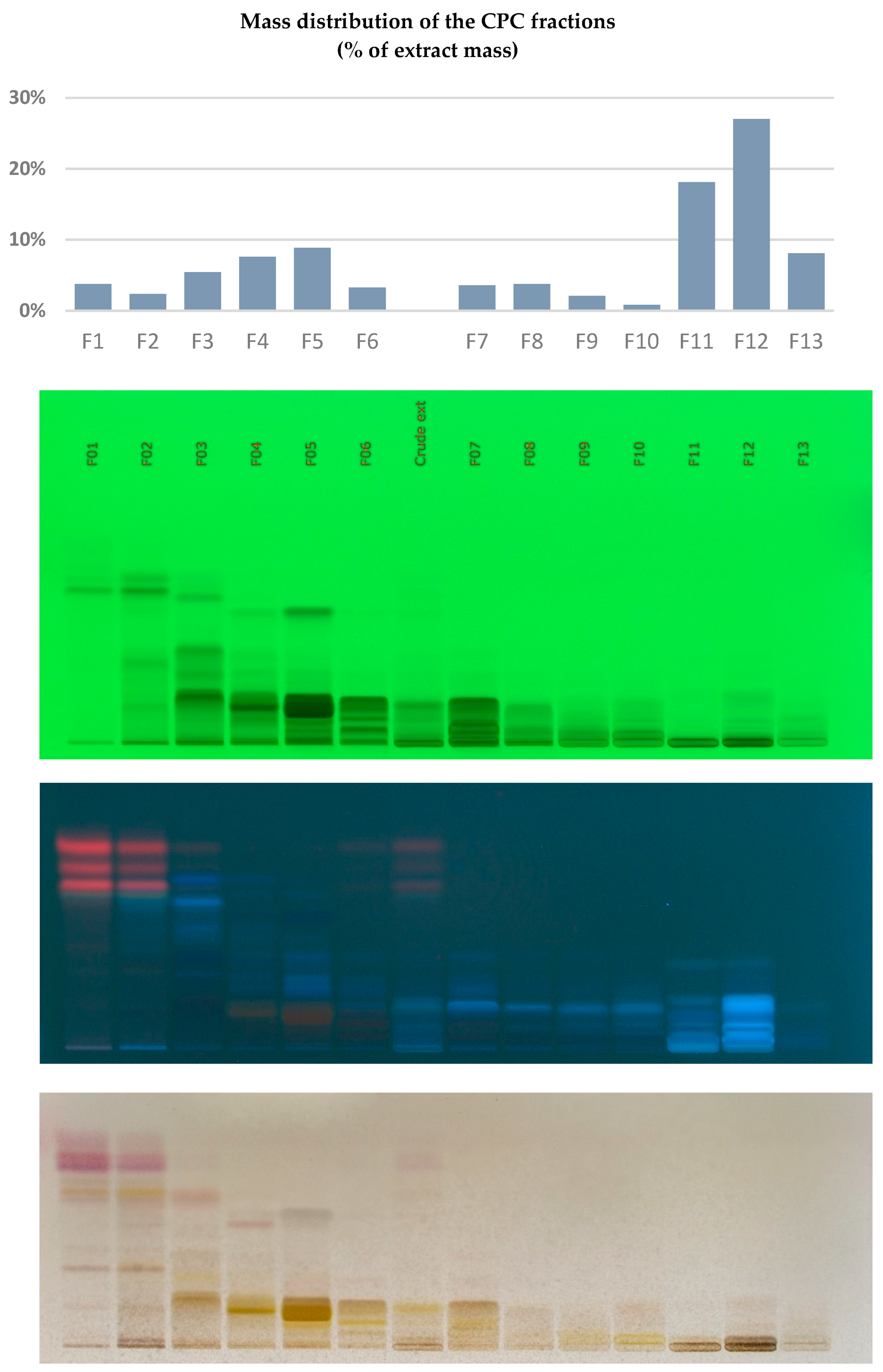

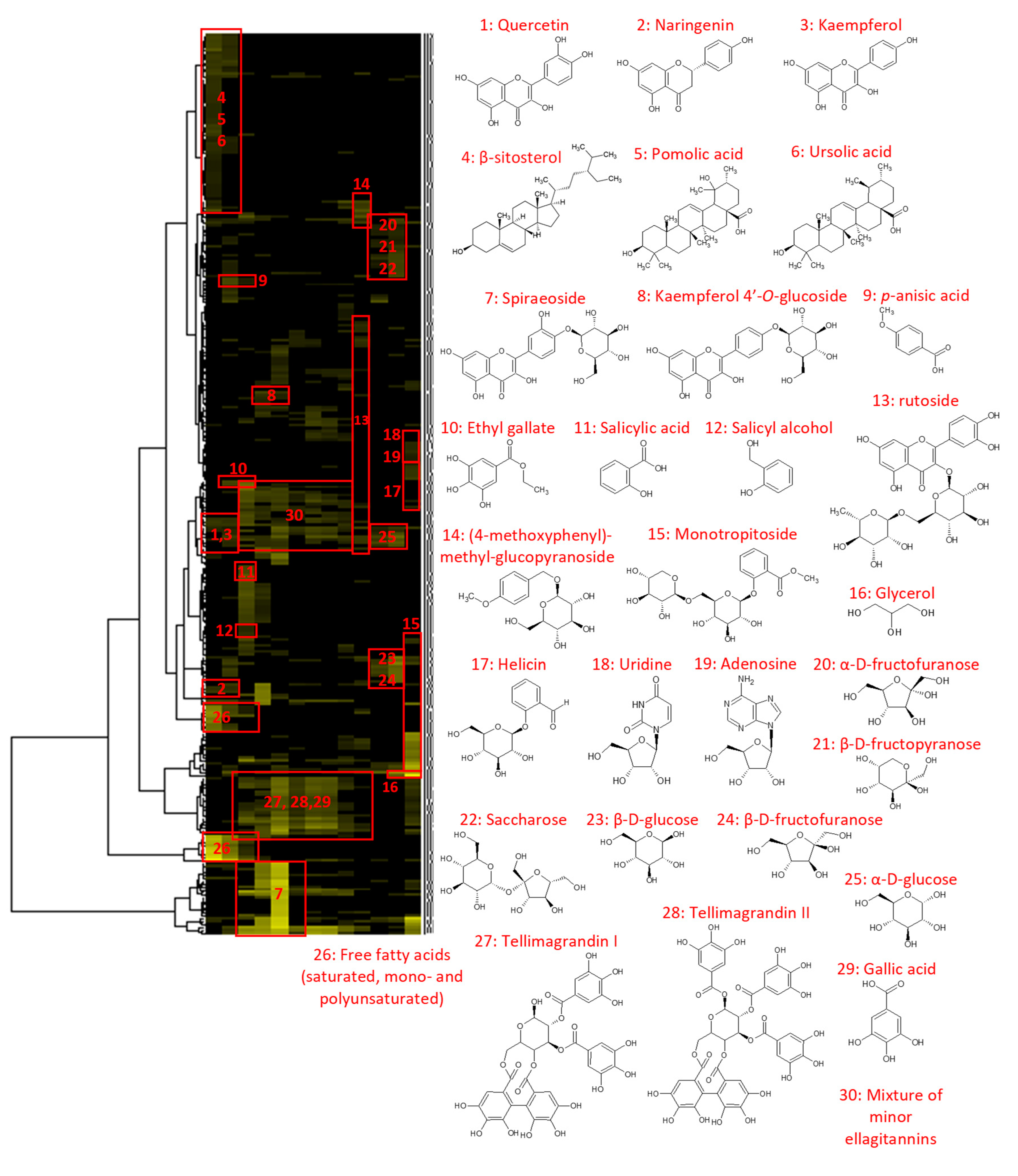

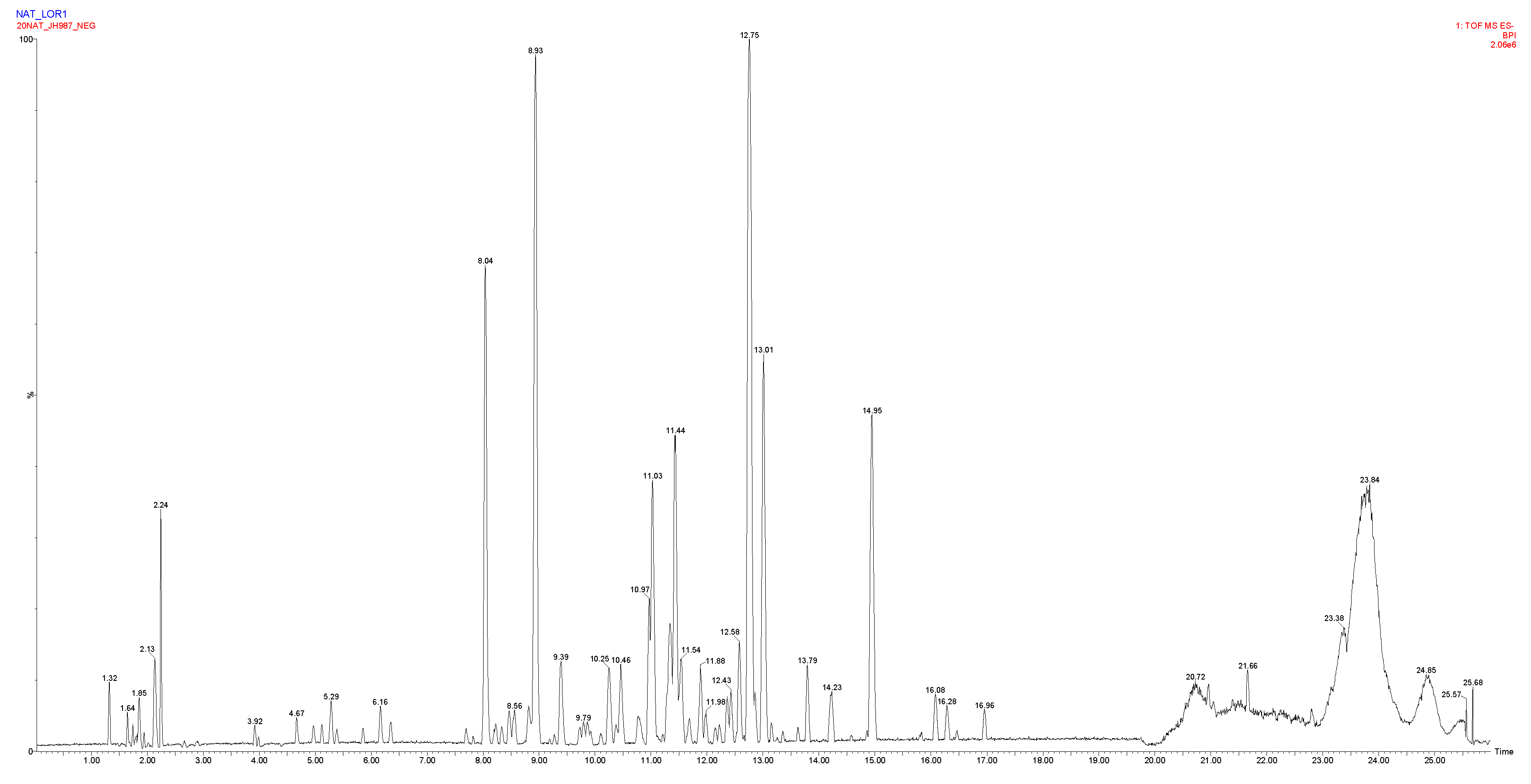

2.1. Chemical Profiling of the Filipendula ulmaria extract

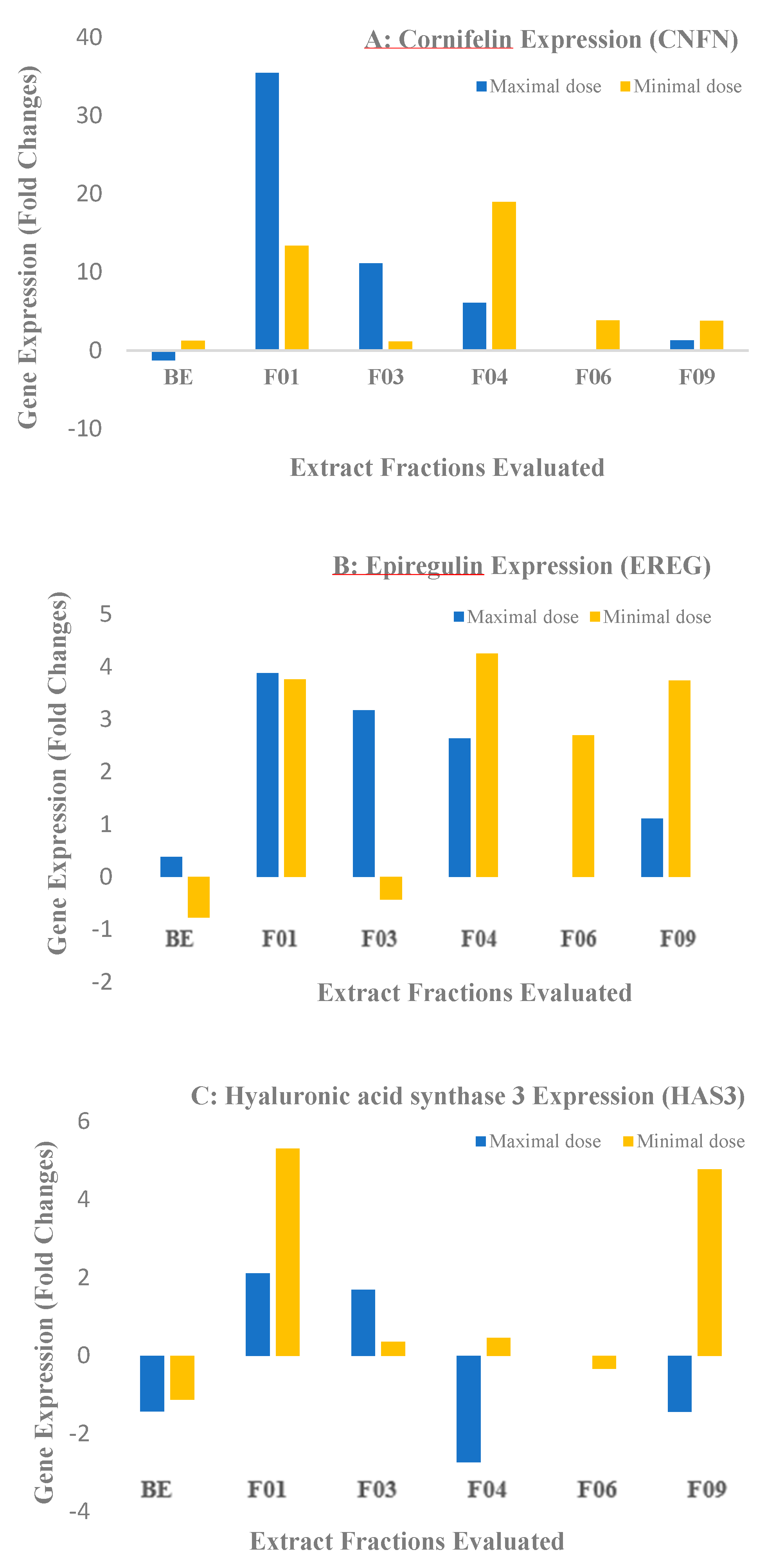

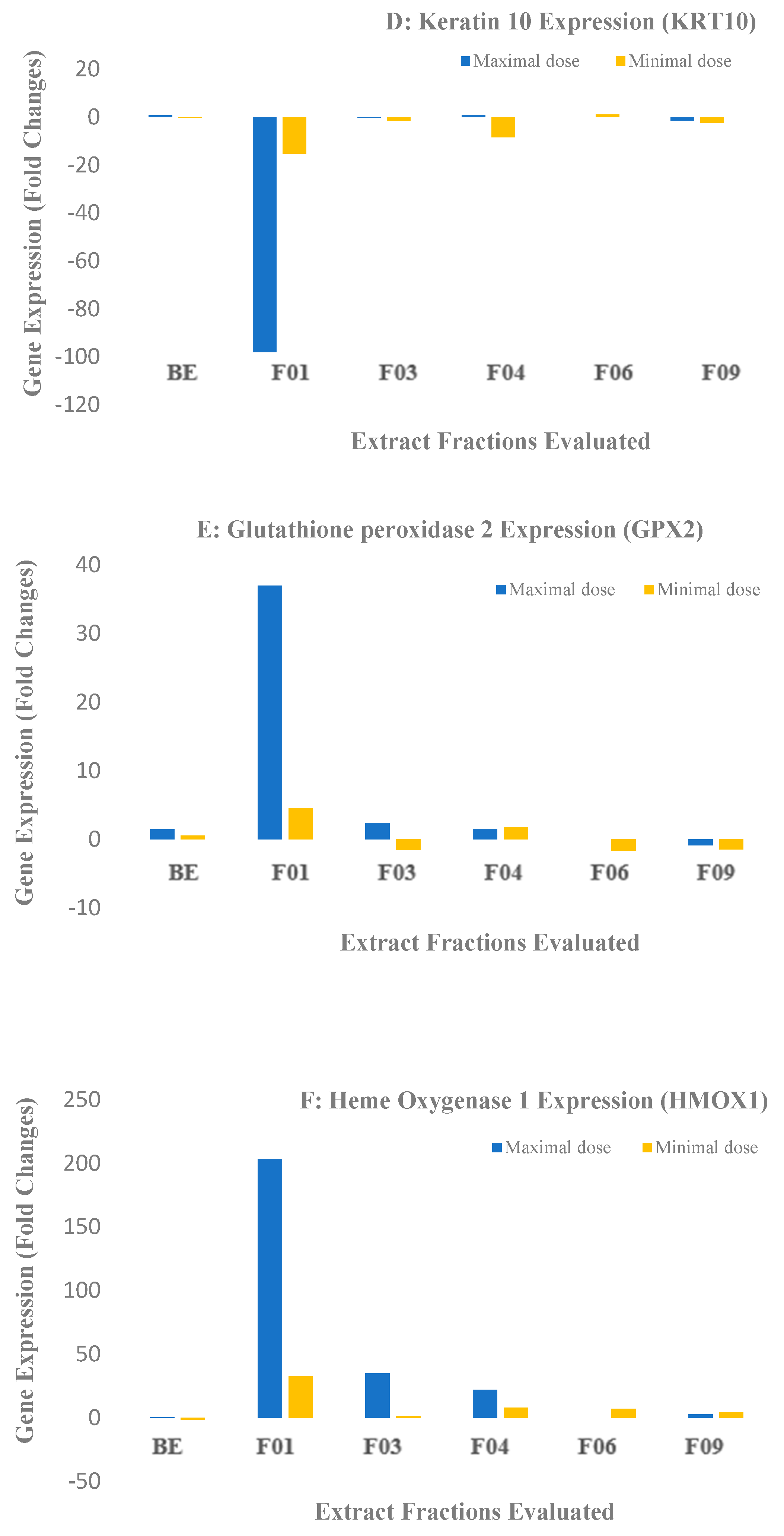

2.2. Biological Results for the Crude Extract and CPC Fractions and Assignment of the Metabolites Responsible for Skin barrier function Improvement

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and reagents

3.2. Extraction Procedure

3.3. Centrifugal Partition Chromatography (CPC)

3.4. NMR analyses and Metabolite Identification

3.5. Liquid Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry analyses of the extract (LC/MS)

3.6. Biological Assays

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Sample Availability

Abbreviations

| CPC | Centrifugal Partition Chromatography |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| HCA | Hierarchical Clustering Analysis |

| BV | Bed Volume |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

| HSQC | Heteronuclear single quantum coherence |

| HMBC | Heteronuclear multiple-bond coherence |

| COSY | Correlated Spectroscopy |

| LC-MS | Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectra |

| FC | Fold Changes |

| CLDN1 | Claudin 1 |

| CNFN | Cornifelin |

| DSG1 | Desmoglein 1 |

| KLK7 | Kallikrein-related peptidase 7 |

| TJP1 | Tight junction protein 1 |

| EREG | Epiregulin |

| HAS3 | Hyaluronic acid synthase 3 |

| HBEGF | Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor |

| KRT19 | Keratin 19 |

| KRT10 | Keratin 10 |

| SPRR1A | Small prolin-rich protein A1 |

| TGM1 | Transglutaminase 1 |

| GPX2 | Glutathione peroxidase 2 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| PPAR | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α |

References

- Ball P.W., I.N. Miller, T.G. Tutin, V.H. Heywood, N.A. Burges, D.M. Moore, D.H. Valentine, S.M. Walters, D.A. Webb, Flora Europaea, Vol 2. Roseaceae to Umbelliferae, Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 6-7.

- Šarić-Kundalić B., C. Dobeš, V. Klatte-Asselmeyer, J. Saukel, Ethnobotanical survey of traditionally used plants in human therapy of east, north and north-east Bosnia and Herzegovina, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 133 (2011) 1051-1076. [CrossRef]

- Vogl S., P. Picker, J. Mihaly-Bison, N. Fakhrudin, A.G. Atanasov, E.H. Heiss, C. Wawrosch, G. Reznicek, V.M. Dirsch, J. Saukel, B. KopP, Ethnopharmacological in vitro studies on Austria’s folk medicine-An unexplored lore in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of 71 Austrian traditional herbal drugs, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 149 (2013) 750-771. [CrossRef]

- Halkes S.B.A., Filipendula ulmaria - A study on the immunomodulatory activity of extracts and constituents, PhD Thesis, University of Utrecht (1998).

- British Herbal Pharmacopoeia, British Herbal Medicine Association, (1983) 91-92.

- British Herbal Pharmacopoeia, British Herbal Medicine Association, 1 (1990) 65-6.

- Bradley PR editor. British Herbal Compendium, British Herbal Medicine Association, 1 (1992) 158-160.

- Bespalov, V.G., V.A. Alexandrov, A.L. Semenov, E.G. Kovan’ko, S.D. Ivanov, G.I. Vysochina, V.A. Kostikova, D.A. Baranenko, The inhibitory effect of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) on radiation-induced carcinogenesis in rats. International Journal of Radiational Biology, 93 (2018) 394–401. [CrossRef]

- Zeylstra, H., Filipendula ulmaria Br, Journal of Phytotherapy, 5 (1998) 8-12.

- Filipendulaeulmaria herba – Meadowsweet, ESCOP Monographs, European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy, editor, Thieme, 2 (2003,) 157-161.

- Berardesca E., F. Distante, G. P. Vignoli, C. Oresajo, and B. Green, Alpha hydroxyacids modulate stratum corneum barrier function, British Journal of Dermatology, 137 (1997) 934–938. [CrossRef]

- Bashir S. J., F. Dreher, A. L. Chew, H. Zhai, C. Levin, R. Stern, H. I. Maibach, Cutaneous bioassay of salicylic acid as a keratolytic, International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 292 (2005) 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Ademola J., C. Frazier, S. J. Kim, C. Theaux, and X. Saudez, Clinical evaluation of 40% urea and 12% ammonium lactate in the treatment of xerosis, The American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 3 (2002) 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Pannakal S., Eilstein J., Prasad A., et al. Comprehensive characterization of naturally occurring antioxidants from the twigs of mulberry (Morus alba) using on-line high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with chemical detection and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Phytochemical Analysis. 2022;33(1):105-114. [CrossRef]

- Hubert, J., J.M. Nuzillard, S. Purson, M. Hamzaoui, N. Borie, R. Reynaud, J.H. Renault, Identification of natural metabolites in mixture: a pattern recognition strategy based on (13)C NMR, Analytical Chemistry, 86 (2014) 2955-2962. [CrossRef]

- Bijttebier S., Auwera A., Voorspoels S., Noten B., Hermans N., Pieters L., ApersS., A First Step in the Quest for the Active Constituents in Filipendula ulmaria (Meadowsweet): Comprehensive Phytochemical Identification by Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry, Planta Medica, 82 (2016) 559-572. [CrossRef]

- Gainche, M., Ogeron, C., Ripoche, I., Senejoux, F., Cholet, J., Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors from Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. and Their Efficient Detections by HPTLC and HPLC Analyses, Molecules, 26 (2021) 1939-1950. [CrossRef]

- Halles, S.B.A., Filipendula ulmaria – a study on the immunomodulatory activity of extracts and constituents [dissertation] Universiteit Utrecht, (1998).

- Samardžić, S., J. Arsenijević, D. Božić, M. Milenković, V. Tešević, Z. Maksimović, Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and gastroprotective activity of Filipendula ulmaria (L.) Maxim. and Filipendula vulgaris Moench, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 213 (2018) 132-137. [CrossRef]

- Katanic, J., T. Boroja, V. Mihailovic, S. Nikles, S.P. Pan, G. Rosic, D. Selakovic, J. Joksimovic, S. Mitrovic, R. Bauer, In vitro and in vivo assessment of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) as anti-inflammatory agent, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 193 (2016) 627-636.

- Harbourne, N., J.C. Jacquier, D. O’Riordan, Optimisation of the aqueous extraction conditions of phenols from meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria L.) for incorporation into beverages, Food Chemistry, 116 (2009) 722-727.

- Nitta, Y., H. Kikuzaki, T. Azuma, Y. Ye, M. Sakaue, Y. Higuchi, H. Komori, H. Ueno, Inhibitory activity of Filipendula ulmaria constituents on recombinant human histidine decarboxylase, Food Chemistry, 138 (2013) 1551-1556.

- Pukalskienė, M., Venskutonis, R., Pukalskas, A., Phytochemical Characterization of Filipendula ulmaria by UPLC/Q-TOF-MS and Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity, Records of Natural Products 9 (2015) 451-455.

- Rockwell G. A., Johnson, G., Sibatani, A., In vitro senescence of human keratinocyte cultures. Cell Structure & Functions, 12 (1987) 539–548.

- Katayama, S., Skoog, T., Jouhilahti, E., Siitonen, H. A., Nuutila, K., Gene expression analysis of skin grafts and cultured keratinocytes using synthetic RNA normalization reveals insights into differentiation and growth control, BMC Genomics 16 (2015) 476-489. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J. H., Lee J. O., Kim, J. H., Lee, S. K., You G. A., Park, S. H., Park, J. M., Kim, E. K., Suh, P. G., An, J. K., Kim, H. S., Quercetin Suppresses HeLa Cell Viability via AMPK-Induced HSP70 and EGFR Down-Regulation, Journal of Cellular Physiology, 223 (2010) 408–414. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.T., Hwang, J. J., Effects of luteolin and quercetin, inhibitors of tyrosine kinase, on cell growth and metastasis-associated properties in A431 cells overexpressing epidermal growth factor receptor, British Journal of Pharmacology, 128 (1999) 999 – 1010.

- Cuevas, M. J., Tieppo, J., Marroni, N. M., Suppression of Amphiregulin/Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signals Contributes to the Protective Effects of Quercetin in Cirrhotic Rat, Journal of Nutrition, 141 (2011) 1299–1305. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Cho, N., Kim, E. M., Park, K. S., Cudrania Tricuspidata Leaf Extracts and Its Components, Chlorogenic Acid, Kaempferol, And Quercetin, Increase Claudin 1 Expression in Human Keratinocytes, Enhancing Intercellular Tight Junction Capacity, Applied Biological Chemistry, 63 (2020) 23. [CrossRef]

- Al-Roujayee, A. S., Naringenin improves the healing process of thermally-induced skin damage in rats, Journal of International Medical Research, 45 (2017) 570–582. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. S., Lobo, J. M. S., Almeida, I. F., Sensitive skin: Active ingredients on the spotlight, International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 44 (2022) 56–73. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. W., Hong, S. P., Jeong, S. W., Simultaneous effect of ursolic acid and oleanolic acid on epidermal permeability barrier function and epidermal keratinocyte differentiation via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α, Journal of Dermatology, 34 (2007) 625–634. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H., Sonam T., Shimizu, K., The Potential of Triterpenoids from Loquat Leaves (Eriobotrya japonica) for Prevention and Treatment of Skin Disorder, International Journal of Molecular Science, 18 (2017) 1030. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Hwang, I. H., and Lee, M. N., Anti-acne vulgaris effect including skin barrier improvement and 5α-reductase inhibition by Tellimagrandin I from Carpinus tschonoskii, BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19 (2019) 323. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Cho,N., Kim, E. M., Park, K. S., Cudrania Tricuspidata Leaf Extracts And Its Components, Chlorogenic Acid, Kaempferol, And Quercetin, Increase Claudin 1 Expression In Human Keratinocytes, Enhancing Intercellular Tight Junction Capacity, Applied Biological Chemistry, 63 (2020) 23. [CrossRef]

- Al-Roujayee, A. S., Naringenin improves the healing process of thermally-induced skin damage in rats, Journal of International Medical Research, 45 (2017) 570–582. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M. S., Lobo, J. M. S., Almeida, I. F., Sensitive skin: Active ingredients on the spotlight, International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 44 (2022) 56–73. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. W., Hong, S. P., Jeong, S. W., Simultaneous effect of Ursolic acid and Oleanolic acid on Epidermal permeability barrier function and epidermal keratinocyte differentiation via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α, Journal of Dermatology, 34 (2007) 625–634. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Hwang, I. H., and Lee, M. N., Anti-acne vulgaris effect including skin barrier improvement and 5α-reductase inhibition by tellimagrandin I from Carpinus tschonoskii, BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19 (2019) 323. [CrossRef]

| Retention time (min) | Observed m/z | Elemental composition | Δppm | Tentative identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.6 | 285.0815 | C9H17O10 | -2.5 | Not assigned |

| 1.8 | 195.0505 [M-H]- | C6H11O7 | 0.0 | Hexonic acid |

| 1.9 | 191.0555 [M-H]- | C7H11O6 | -0.5 | Quinic acid |

| 2.2 | 341.1089 [M-H]- | C12H21O11 | 1.5 | Saccharose* |

| 4.6 | 331.0664 [M-H]- | C13H15O10 | 0.0 | Mono-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 1 |

| 4.9 | 331.0665 [M-H]- | C13H15O10 | -0.3 | Mono-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 2 |

| 5.1 | 339.1292 | C13H23O10 | 0.3 | Not assigned |

| 5.2 | 169.0137 [M-H]- | C7H5O5 | 0.0 | Gallic acid* |

| 5.4 | 483.0783 [M-H]- | C20H19O14 | 1.7 | Di-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 1 |

| 5.8 | 331.0667 [M-H]- | C13H15O10 | 0.6 | Mono-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 3 |

| 6.1 | 483.0775 [M-H]- | C20H19O14 | 0.2 | Di-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 2 |

| 6.3 | 315.0715 [M-H]- | C13H15O9 | -0.3 | Dihydroxybenzoic acid O-hexoside |

| 7.7 | 319.0423 [M-H]- | C15H11O8 | -9.7 | Dihydromyricetin |

| 7.8 | 483.0775 [M-H]- | C20H19O14 | 0.0 | Di-O-galloyl-hexoside isomer 3 |

| 8.0 | 785.0839 [M-H]- | C34H25O22 | 0.3 | Tellimagrandin I* or isomer |

| 8.2 | 635.0889 [M-H]- | C27H23O18 | 0.8 | Tri-O-galloyl-hexoside |

| 8.3 | 451.1010 [M-H]- | C24H19O9 | -4.2 | Coumaroylepigallocatechin |

| 8.4 | 375.0694 191.0556 quinic acid fragment |

C18H15O9 C7H11O6 |

-5.9 0.0 |

Not assigned |

| 8.5 | 289.0714 909.0999, 785.0842, 454.0461 |

C15H13O6 | 0.7 | Catechin |

| 8.8 | 953.0895 [M-H]- 909.0999 [M-COOH]- 785.0837, 465.0367, 454.0460 |

C41H29O27 C40H29O25 C34H25O22 |

-0.1 0.0 |

Chebulagic acid or isomer |

| 8.9 | 785.0840 [M-H]- | C34H25O22 | 0.4 | Tellimagrandin I* or isomer |

| 9.3 | 319.0431 | C15H11O8 | Not assigned | |

| 9.7 | 339.0718 | C15H15O9 | 0.6 | Not assigned |

| 9.8 | 359.0745 337.0925 coumaroylquinic acid 191.0556 quinic acid fragment |

C18H15O8 C16H17O8 C7H11O6 |

Not assigned | |

| 9.9 | 785.0845 [M-H]- 481.1118, 491.1403, 625.1407 |

C34H25O22 |

1.0 | Minor isomer of tellimagrandin I |

| 10.1 | 935.0803 [M-H]- 467.0357 [M-H-3galloyl]- |

C41H27O26 |

1.3 | Casuarinin or Casuarictin |

| 10.2 | 1105.1012 [M-H]- 1061.1110 fragment of Rugosin D 936.0874 [M-2H]2- 530.0513 fragment of rugosin A 541.0423 |

C48H33O31 C47H33O29 |

0.5 0.2 |

Rugosin A Rugosin D |

| 10.4 | 937.0955 [M-H]- 959.0774, 479.0345, 468.0435 |

C41H29O26 | 0.9 | Tellimagrandin II* |

| 10.8 | 935.0800 [M-H]- 787.1003 [M-H-galloyl]- 467.0357 [M-H-3galloyl]- 303.0485 [M-H-4galloyl]- |

C41H27O26 | 1.0 | Casuarinin or Casuarictin |

| 10.9 | 687.3029 [M-H]- | xx | xx | Not assigned |

| 11.0 | 609.1450 [M-H]- | C27H29O16 | -1.0 | Rutoside* |

| 11.3 | 197.0454 [M-H]- | C9H9O5 | 2.0 | Syringic acid |

| 11.4 | 463.0877 [M-H]- | C21H19O12 | 0.0 | Quercetin O-hexoside isomer 1 |

| 11.5 | 463.0876 [M-H]- 301.0348 quercetin fragment |

C21H19O12 | -0.2 | Quercetin O-hexoside isomer 2 |

| 11.9 | 593.1505 [M-H]- 1087.0900 [2M-H]- 285.0396 kaempferol fragment |

C27H29O15 | -0.2 | Kaempferol O-hexoside-rhamnoside |

| 11.9 | 433.0771 [M-H]- | C20H17O11 | 0.0 | Quercetin O-pentoside |

| 12.1 | 447.0930 [M-H]- | C21H19O11 | 0.0 | Quercetin O-rhamnoside |

| 12.2 | 477.1034 [M-H]- | C22H21O12 | 0.2 | Methyl-quercetin O-hexoside |

| 12.3 | 433.0772 [M-H]- 301.0353 quercetin fragment |

C20H17O11 | 0.2 | Quercetin O-pentoside |

| 12.4 | 447.0927 [M-H]- | C21H19O11 | 0.0 | Quercetin O-rhamnoside |

| 12.5 | 477.1031 [M-H]- | C22H21O12 | -0.4 | Methyl-quercetin O-hexoside |

| 12.7 | 463.0882 301.0353 quercetin fragment |

C21H19O12 | 1.1 | Spiraeoside* (Quercetin O-hexoside isomer 3) |

| 12.8 | 601.0827 [M-H]- 301.0347 quercetin fragment |

C27H21O16 | -0.5 | Quercetin O-galloyl-pentoside |

| 13.0 | 447.0922 [M-H]- 285.0389 kaempferol fragment |

C21H19O11 | -1.1 | Kaempferol 4’-O-glucoside* |

| 13.2 | 519.1136 465.1031 |

C24H23O13 C21H21O12 |

-0.6 -0.4 |

Not assigned |

| 13.4 | 615.0984 [M-H]- | C28H23O16 | -0.3 | Quercetin O-galloyl-hexoside |

| 13.8 | 585.0880 [M-H]- 301.0350 quercetin fragment |

C27H21O15 C15H9O7 |

0.9 0.7 |

Quercetin O-galloyl-arabinoside |

| 14.2 | 297.0399 [M-H]- | C16H9O6 | -7.1 | Not assigned |

| 14.9 | 301.0348 [M-H]- | C15H9O7 | 1.0 | Quercetin* |

| 16.1 | 271.0606 [M-H]- | C15H11O5 | 0.4 | Naringenin* |

| 16.2 | 285.0399 [M-H]- | C15H9O6 | 1.1 | Kaempferol* |

| 16.5 | 329.2329 | C18H33O5 | 0.3 | Tri-HOME (trihydroxyyoctadecenoic acid) |

| 16.9 | 287.222 | C16H31O4 | 1.5 | Dihydroxypalmitic acid |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).