1. Introduction

Bone grafting has a long history and is still one of the most widely used techniques for treating bone loss in the musculoskeletal system [

1,

2]. The main complication of reconstruction surgery is surgical site infection (SSI). This risk is variable, ranging from 0.7% to 13% [

1,

3,

4], because it depends on multiple factors [

5]. These include risks intrinsic to the patient (diabetes, smoking, local history of surgery, etc.), surgical indication (location, type of osteosynthesis or prosthetic material used, etc.), and type of bone graft. There are three main types of human bone graft differing in their origin and method of preservation. These are (i) fresh bone autografts, (ii) frozen bone allografts without added cryopreserving agents, and (iii) bone allografts decellularized by a physical-chemical process. Autografts are the reference for biocompatibility but are not widely available. They are the gold standard for studying new biomaterials [

2]. Allografts avoid co-morbidity at the harvesting site and their quantities and availability are unrestricted, but their osseointegration capacity is weaker [

6].

The pathophysiology of an SSI [

7] with a bone graft can be comparable to that with an implantable medical device (osteosynthesis plate or prosthesis), whether by direct intraoperative contamination or secondary contamination via the haematogenous route. Revascularisation and osseointegration of a bone graft are long and sometimes partial processes. The bone graft behaves like an inert foreign body, at least temporarily during the first few weeks after implantation. Bacterial adhesion to the surface of the implanted device is the first stage in biofilm growth [

8]. This process is governed by several factors, including the specific characteristics of the bacteria, local environmental conditions, and the physical, chemical, and structural properties of the contaminated surface [

8,

9]. The growth of bacteria in contact with allografts, particularly according to the type of graft used, has not been studied.

The aim of our study was to compare bacterial adhesion and growth in contact with frozen or decellularized human bone grafts (allografts) versus fresh bone grafts (autografts) in vitro. Our hypothesis was that bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation would be equivalent for the three different types of bone graft (fresh, frozen, and decellularized).

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Authorisation

All the tissues and cells of human origin came from a non-profit tissue bank (Ostéobanque®, France) and from a university orthopaedic surgery and traumatology department with authorisation for use in research (DC-2021-4555).

Selection and Preservation of Bone Grafts

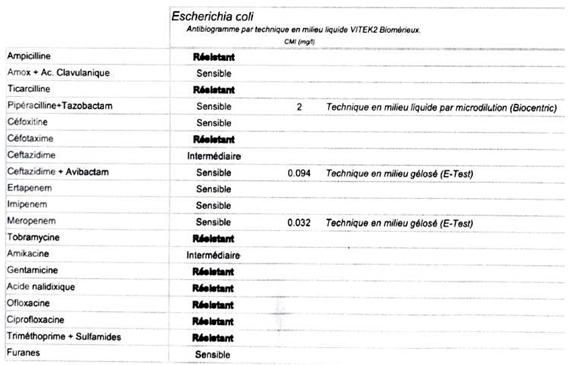

All the bone fragments were derived from postoperative residues after total hip replacement. The cancellous bone was cut into 5 × 5 × 5 mm cubes using a surgical saw in a sterile environment and then divided into three groups according to their method of preservation:

- -

Fresh, stored at 4°C in physiological saline, maximum 2 days ("Fresh" group),

- -

Frozen, without added cryopreserving agents, directly at −40 °C, between 5 and 21 days ("Frozen" group),

- -

At room temperature, after additional decellularization treatment combining mechanical washing with physiological serum (ultrasound and centrifugation) followed by extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO2) ("Decellularized" group).

All the fragments (

Figure 1) came from the same patient for a given series of tests.

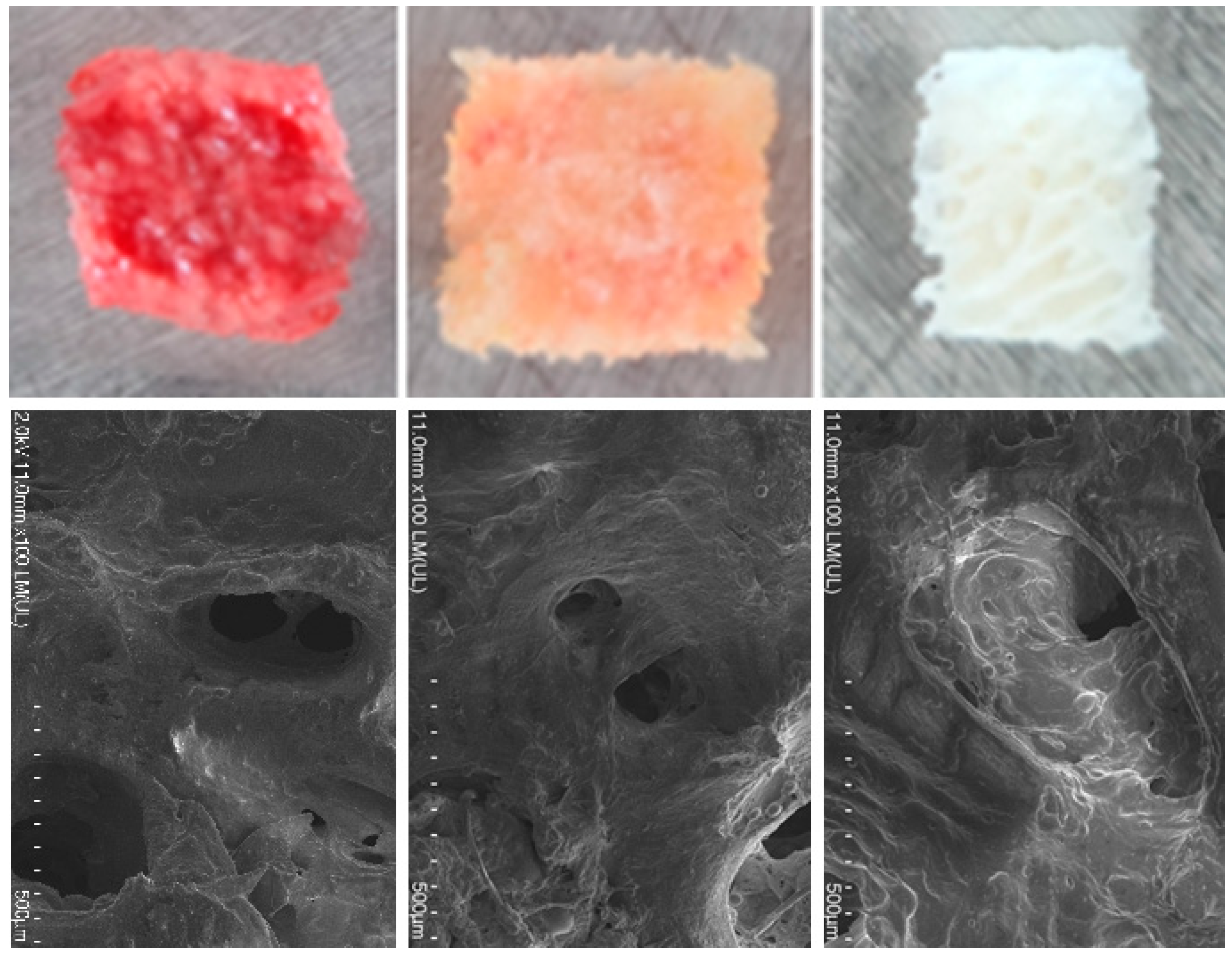

Bacterial Strains and Preparation of Bacterial Suspensions

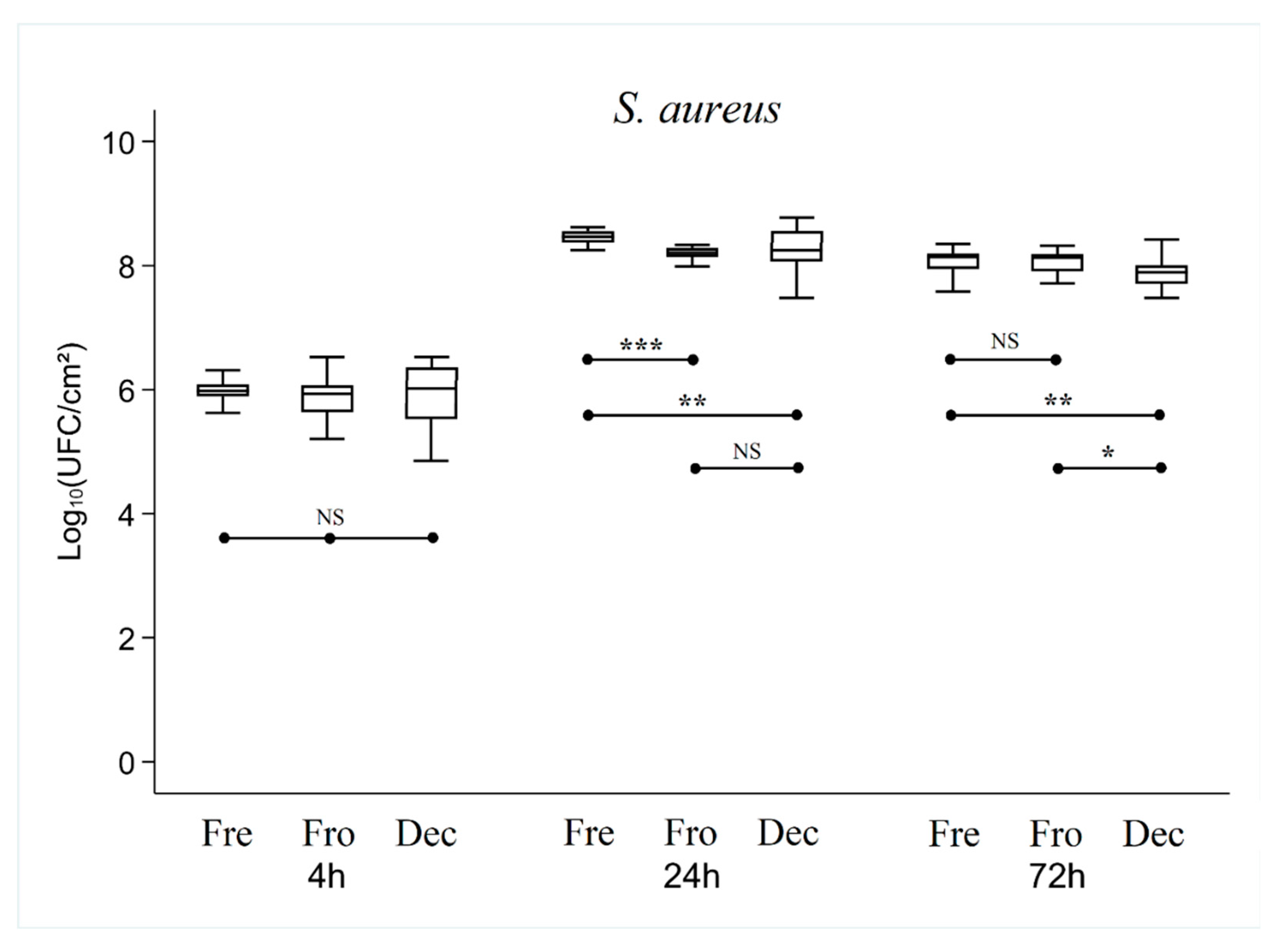

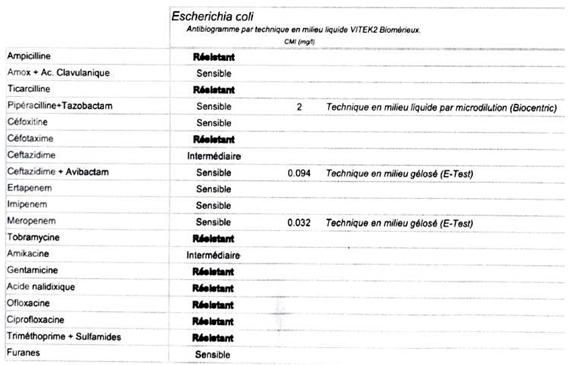

The strains used were antibiotic-resistant strains of S

. aureus, S. epidermidis, and

E. coli. Their antibiograms are given in

Appendix A. This choice was made to limit the effects of systematic pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis with cefazolin during prosthetic surgery in line with current national recommendations [10-12]. Their ability to form biofilm was checked beforehand using a crystal violet test. An initial subculture was carried out using samples from the bacterial collection of a university hospital. A second subculture at 24 hours was used to prepare a stock solution of tryptone soy broth (TSB) containing 108 bacteria per millilitre (target optical density 600 nm), which was then diluted to 10

-4.

Seeding of Bacteria on Bone Grafts

All the bone fragments were soaked for 30 minutes in TSB to rehydrate them before bacterial deposition. The three types of bone grafts were placed in Falcon® 24-well microplates and seeded with 1.5 ml of solution at a bacterial concentration of 10-4. Incubation was carried out in a controlled atmosphere at 37 °C with shaking at 15 rpm for a maximum time of 72 hours.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope

Two samples of each type of bone graft were recovered after 24 hours of culture and stained with a Live/Dead® BacLightTM Bacterial Viability Kit (L7012, Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions [

13]. The dye solution contained SYTO® 9 (green fluorescence, excitation 480 nm/emission 500 nm) and propidium iodide (red fluorescence, excitation 490 nm/emission 635 nm) in equal proportions. Contact time was 15 min at 37 °C in the dark. The fragments were then rinsed three times with TSB. Observations were carried out at room temperature with a Zeiss LSM80 Airyscan confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Le Pecq, France) using objective 20 (20XNA 1.3 Plan-Neofluar objective). The average volume occupied by viable biofilm was expressed relative to the total volume scanned (expressed as a percentage). Analyses were performed using the Fiji image analysis software [

14].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of a Kruskal-Wallis test for the overall difference (between the three bone types) and a Dunn post-hoc test (if KW was significant). Biofilm thickness measurements are expressed as mean +/- standard deviation and compared by a Kruskal-Wallis test. The statistical significance threshold was p < 0.05. Analysis was performed using STATA software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA)..

3. Results

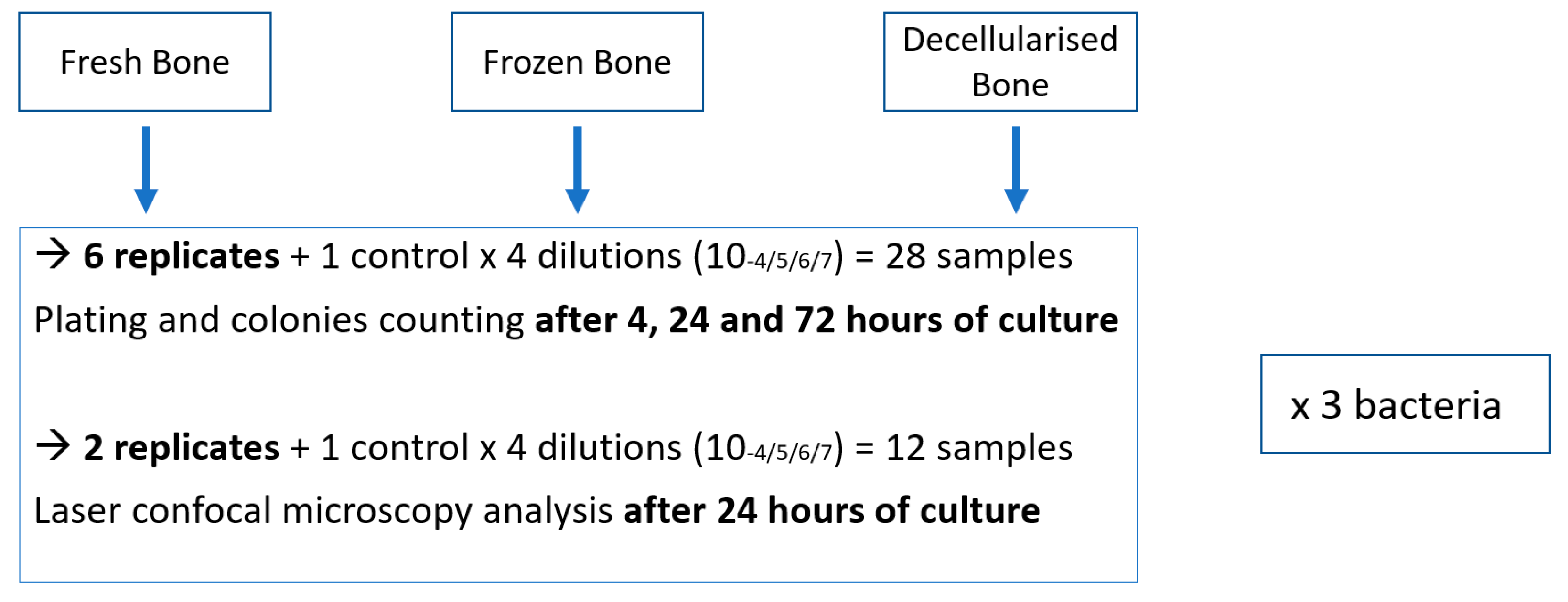

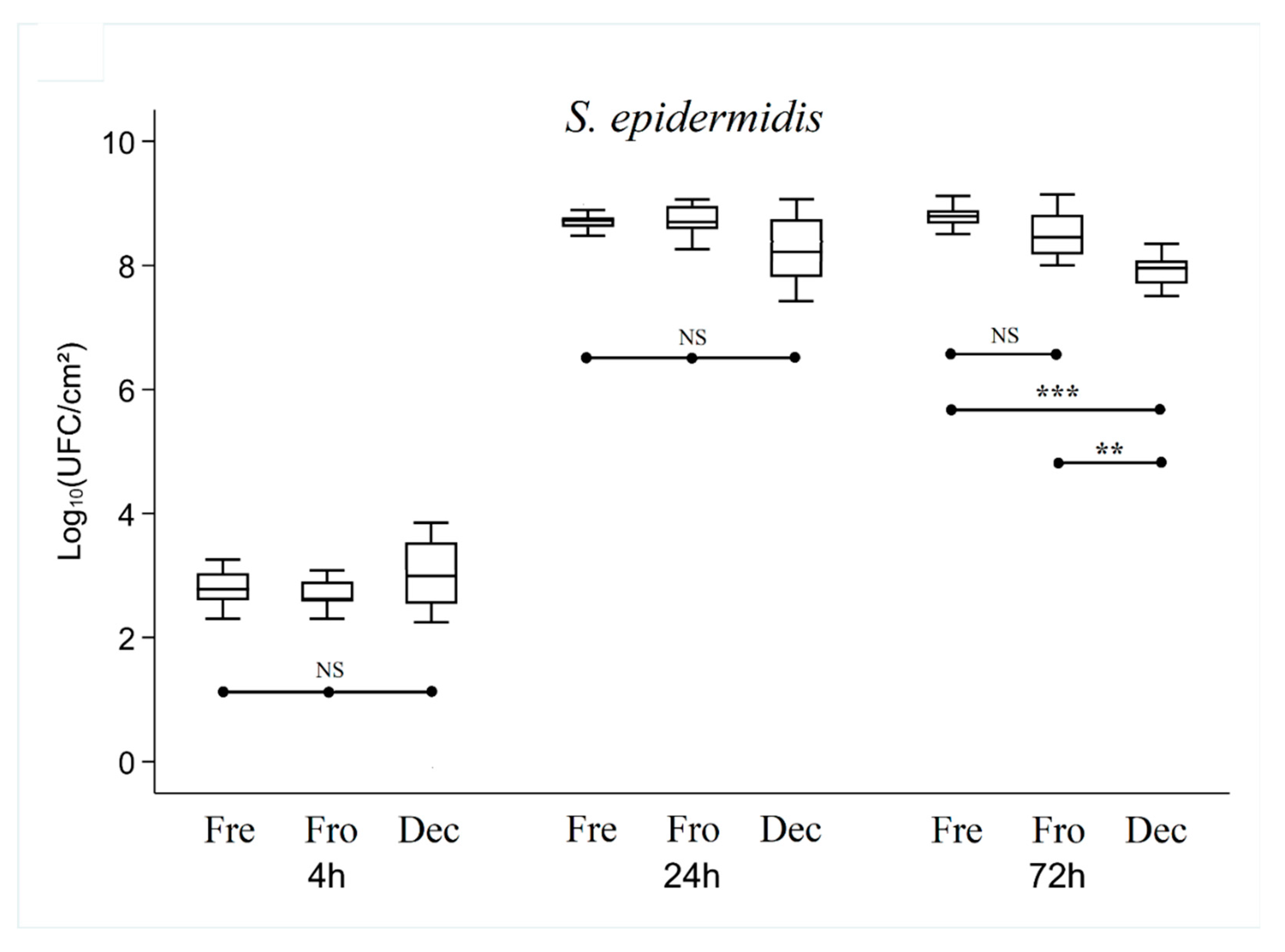

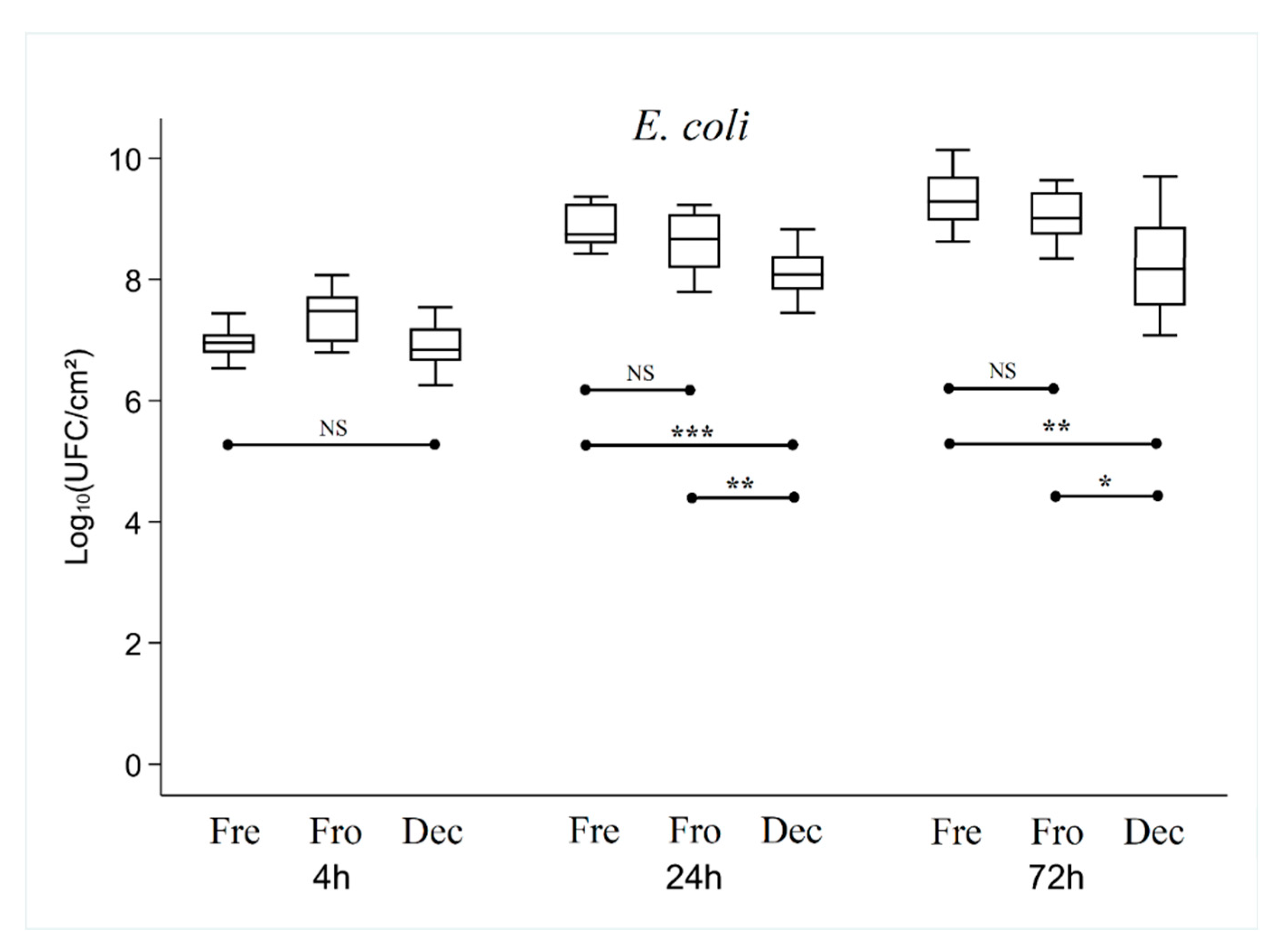

There was no significant difference in bacterial adhesion (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) between the three types of bone tested, irrespective of the bacterial strain used (p > 0.22).

However, adhesion was significantly different between the three strains after 4 hours of culture, with an average of 2.71 +/- 0.97 lg, 5.96 +/- 0.45 lg and 7.01+/-0.44 lg CFU for S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and E. coli respectively (p < 0.001).

After 24 hours of culture, overall analysis of the results showed that the number of CFUs was higher or equivalent in the Fresh bone group compared with the Frozen and Decellularized bone groups (which showed no significant difference between them).

- -

For S. epidermidis, there was no significant difference (p = 0.09), with an average of 8.49 ± 0.53 lg CFUs.

- -

For S. aureus, the number of CFUs was significantly lower in the Frozen (p < 0.001) and Decellularized (p < 0.01) bone groups than in the Fresh group (8.21 ± 0.09 lg, 8.25 ± 0.31 lg and 8.46 ± 0.11 lg, respectively)

- -

For E. coli, the number of CFUs was significantly lower in the Decellularized (p < 0.001) and Frozen (p < 0.01) bone groups than in the Fresh group (8.10 ± 0.39 lg, 8.65 ± 0.41 lg and 8.89 ± 0.34 lg respectively)).

After 72 hours of culture, there was no longer any significant difference between the Fresh and Frozen bone groups, while the number of CFUs in the Decellularized group was still significantly lower (p < 0.01) (7.93 ± 0.23 lg, 8.52 ± 0.35 lg and 8.78 ± 0.20 lg for Decellularized, Frozen and Fresh bone respectively with S. epidermidis, 7.86 ± 0.24 lg, 8.06 ± 0.21 lg and 8.06 ± 0.20 lg for Decellularized, Frozen and Fresh respectively with S. aureus, and (8.40 ± 0.94 lg, 9.04 ± 0.40 lg and 9.32 ± 0.42 lg for Decellularized, Frozen, and Fresh respectively with E. coli).

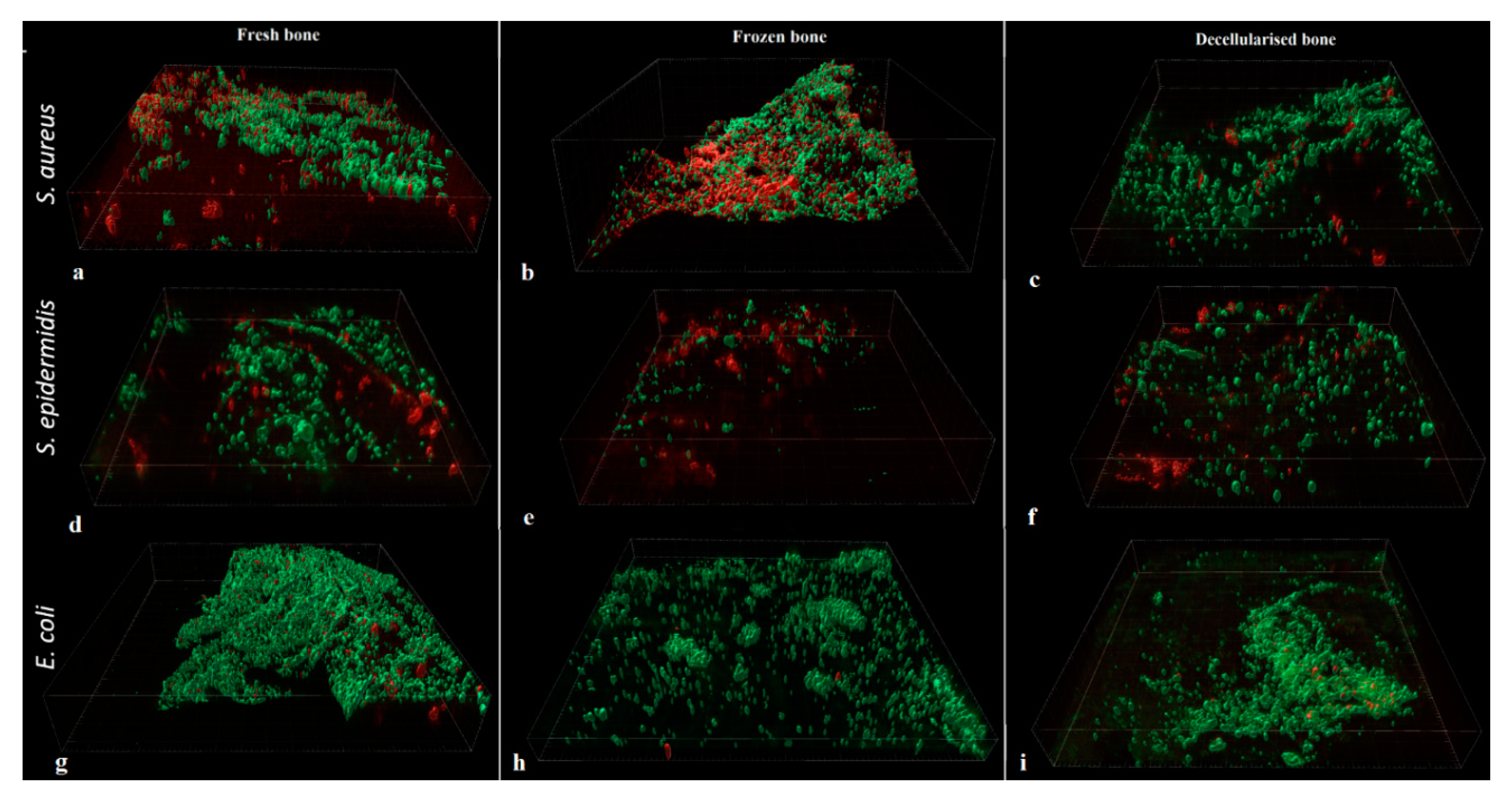

When biofilm formation was analysed using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy, no significant difference in volume was found between the different types of bone, whatever the bacterial strain.

- -

For

S. aureus (

Figure 6a-c), the volume of biofilm was 1.34 ± 0.13% for Fresh, 0.66 ± 0.12% for Frozen and 1.40 ± 0.61% for Decellularized bone (p = 0.103).

- -

For

S. epidermidis (

Figure 6d-f), the volume of biofilm was 0.27 ± 0.03% for Fresh, 0.07 ± 0.03% for Frozen, and 0.12 ± 0.03% for Decellularized bone (p = 0.112).

- -

For

E. coli (

Figure 6g-i), the biofilm volume was 2.13 ± 0.38% for Fresh, 2.13 ± 1.69% for Frozen, and 0.24 ± 0.26% for Decellularized bone (p = 0.138).

4. Discussion

This study shows the adhesion and biofilm growth of three bacterial strains on bone fragments preserved in three different ways (fresh, frozen, and decellularized). Taking all the results into account, and although some were statistically significant, the differences in absolute values were modest given the scales of magnitude. If we take fresh bone (equivalent to autograft) as the gold standard, owing to the low rates of infection in clinical studies, it seems that the method of treatment and preservation of a bone graft is not a factor influencing the characteristics of adhesion and growth of biofilm, supporting our initial hypothesis.

The originality of this work is that it provides general data on the initial development of infections in the context of bone grafting, with a specific focus on the impact of the method of preservation of human bone grafts used in orthopaedic practice (fresh autograft, frozen allograft, decellularized processed allograft).

These results are in line with those of Nysirios et al. [

15] who found no differences in bacterial adhesion or growth between three bone substitutes (xenograft, allograft, synthetic materials) with five bacterial strains.

Various studies show that the physical properties (roughness, nanostructure, etc.) [16-22] and chemical properties (molecular structure, electrostatic charge, hydrophilicity, etc.) [23-28] of biomaterials influence initial adhesion and biofilm formation, although how they do so is not fully understood. Generally speaking, tissues composed of lipids and proteins (fresh and frozen bone) seem to favour biofilm formation. Biofilms act as receptors for bacteria, particularly staphylococci [

24,

29]. Historically, porous materials have also been considered to be more favourable to the development of infections than non-porous ones [

30]. However, this assumption is now in doubt, particularly with the discovery of the antibacterial effect produced by modifying the surface structure of materials on micro- and nanometric scales [

31,

32].

One limitation of this study is its use of an in vitro experimental model, which is only an approximation of reality. The growth of bacteria on the bone fragments was regularly disturbed by the washings (4 h and 24 h) necessary to control the environment as much as possible and standardise the method. However, these are not typical conditions for the development of an infection in a surgical site during the implantation of a bone graft (no iterative washing, permanent supply of nutrients, etc.). This potential bias was controlled by a complementary experiment that came closer to clinical conditions (no intermediate washing for 72 hours), and which yielded fully superimposable results.

Our experimental conditions did not take into account potential immunological phenomena (in the broadest sense). A donor's biological characteristics, the compatibility of a graft with the recipient host, and the presence of living immune cells in a graft (in the case of a fresh autograft) can influence the development of an infection positively or negatively [

33]. The bias linked to inter-individual differences in the donor was controlled by selecting a single donor for each manipulation.

Another limitation is that freezing times of 3–5 days are very different from those used in a tissue bank, where the quarantine period is at least several weeks. This difference may limit the transformations undergone by proteins and lipids due to freezing, albeit these alterations seem to occur at time scales of years [

34].

5. Conclusions

Human bone grafts, irrespective of how they are stored and processed (fresh, frozen, or decellularized) had similar in vitro bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation characteristics. Comparative clinical studies with these different grafts are now needed to confirm our results and validate the absence of any increased infectious risk when using human allograft bone as a bone substitute.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GV, YW, GF, OT ; methodology, GF, OT ; formal analysis, GF ; investigation, GF.; writing—original draft preparation, GF, GV; writing—review and editing, GV, RE OT, SD; supervision, SB, JMN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

References

- Delloye C, Cornu O, Druez V, Barbier O. Bone allografts: What they can offer and what they cannot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. May 2007;89(5):574-9.

- Wang W, Yeung KWK. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioact Mater. 7 June 2017;2(4):224-47. [CrossRef]

- Zamborsky R, Svec A, Bohac M, Kilian M, Kokavec M. Infection in Bone Allograft Transplants. Exp Clin Transplant Off J Middle East Soc Organ Transplant. Oct 2016;14(5):484-90.

- Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ, Raskin KA. Infection in massive bone allografts. Clin Orthop. March 2005;(432):210-6. [CrossRef]

- Lee FH, Shen PC, Jou IM, Li CY, Hsieh JL. A Population-Based 16-Year Study on the Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infection in Patients after Bone Grafting: A Cross-Sectional Study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). Nov 2015;94(47):e2034.

- Villatte G, Erivan R, Descamps S, Arque P, Boisgard S, Wittrant Y. In vitro osteoblast activity is decreased by residues of chemicals used in the cleaning and viral inactivation process of bone allografts. PloS One. 2022;17(10):e0275480. [CrossRef]

- Zabaglo M, Sharman T. Postoperative Wound Infection. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 [cited 13 June 2023]. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560533/.

- Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC. How do bacteria know they are on a surface and regulate their response to an adhering state? PLoS Pathog. Jan 2012;8(1):e1002440.

- An YH, Friedman RJ. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43(3):338-48.

- Yamada K, Matsumoto K, Tokimura F, Okazaki H, Tanaka S. Are Bone and Serum Cefazolin Concentrations Adequate for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis? Clin Orthop. Dec 2011;469(12):3486-94.

- Chang Y, Shih HN, Chen DW, Lee MS, Ueng SWN, Hsieh PH. The concentration of antibiotic in fresh-frozen bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Oct 2010;92-B(10):1471-4. [CrossRef]

- Martin C. Antibioprophylaxie in surgery and interventionnelle medicine (adult patients). Actualization 2018 [Internet]. Société Française d’Anesthésie et de Réanimation. 2018 [cited 13 June 2023]. Available at: https://sfar.org/antibioprophylaxie-en-chirurgie-et-medecine-interventionnelle-patients-adultes-maj2018/.

- Robertson J, McGoverin C, Vanholsbeeck F, Swift S. Optimisation of the Protocol for the LIVE/DEAD® BacLightTM Bacterial Viability Kit for Rapid Determination of Bacterial Load. Front Microbiol. 12 Apr 2019;10:801. [CrossRef]

- Fiji: ImageJ, with "Batteries Included" [Internet]. [cited 20 July 2022]. Available at: https://fiji.sc/.

- Nisyrios T, Karygianni L, Fretwurst T, Nelson K, Hellwig E, Schmelzeisen R, et al. High Potential of Bacterial Adhesion on Block Bone Graft Materials. Materials. 1 May 2020;13(9):2102. [CrossRef]

- Bhadra CM, Khanh Truong V, Pham VTH, Al Kobaisi M, Seniutinas G, Wang JY, et al. Antibacterial titanium nano-patterned arrays inspired by dragonfly wings. Sci Rep. Dec 2015;5(1):16817. [CrossRef]

- Damiati L, Eales MG, Nobbs AH, Su B, Tsimbouri PM, Salmeron-Sanchez M, et al. Impact of surface topography and coating on osteogenesis and bacterial attachment on titanium implants. J Tissue Eng. 1 Jan 2018;9:2041731418790694. [CrossRef]

- Damiati L, Eales MG, Nobbs AH, Su B, Tsimbouri PM, Salmeron-Sanchez M, et al. Impact of surface topography and coating on osteogenesis and bacterial attachment on titanium implants. J Tissue Eng. 1 Jan 2018;9:204173141879069. [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva E, Truong VK, Stiesch M, Chichkov BN, Crawford RJ, Wang J, et al. Bacterial Retention on Superhydrophobic Titanium Surfaces Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Ablation. Langmuir. 15 March 2011;27(6):3012-9. [CrossRef]

- Puckett SD, Taylor E, Raimondo T, Webster TJ. The relationship between the nanostructure of titanium surfaces and bacterial attachment. Biomaterials. Feb 2010;31(4):706-13. [CrossRef]

- Yoshinari M, Oda Y, Kato T, Okuda K. Influence of surface modifications to titanium on antibacterial activity in vitro. Biomaterials. 1 Jan 2001;22(14):2043-8. [CrossRef]

- Truong VK, Lapovok R, Estrin YS, Rundell S, Wang JY, Fluke CJ, et al. The influence of nano-scale surface roughness on bacterial adhesion to ultrafine-grained titanium. Biomaterials. 1 May 2010;31(13):3674-83. [CrossRef]

- Tang H, Wang A, Liang X, Cao T, Salley SO, McAllister JP, et al. Effect of surface proteins on Staphylococcus Epidermidis adhesion and colonization on silicone. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. Aug 2006;51(1):16-24. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann M, Vaudaux PE, Pittet D, Auckenthaler R, Lew PD, Perdreau FS, et al. Fibronectin, Fibrinogen, and Laminin Act as Mediators of Adherence of Clinical Staphylococcal Isolates to Foreign Material. J Infect Dis. Oct 1988;158(4):693-701. [CrossRef]

- An YH, Friedman RJ. Concise review of mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to biomaterial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43(3):338-48.

- Hogt AH, Dankert J, Feijen J. Adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus saprophyticus to a Hydrophobic Biomaterial. Microbiology. 1 Sept 1985;131(9):2485-91. [CrossRef]

- Hogt AH, Dankert J, De Vries JA, Feijen J. Adhesion of Coagulase-negative Staphylococci to Biomaterials. Microbiology. 1 Sept 1983;129(9):2959-68. [CrossRef]

- Brokke P, Dankert J, Carballo J, Feijen J. Adherence of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci onto Polyethylene Catheters in vitro and in vivo: A Study on the Influence of various Plasma Proteins. J Biomater Appl. 1 Jan 1991;5(3):204-26. [CrossRef]

- Tegoulia VA, Cooper SL. Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to self-assembled monolayers: effect of surface chemistry and fibrinogen presence. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 1 Apr 2002;24(3):217-28.

- Clauss M, Trampuz A, Borens O, Bohner M, Ilchmann T. Biofilm formation on bone grafts and bone graft substitutes: comparison of different materials by a standard in vitro test and microcalorimetry. Acta Biomater. Sept 2010;6(9):3791-7. [CrossRef]

- Nishitani T, Masuda K, Mimura S, Hirokawa T, Ishiguro H, Kumagai M, et al. Antibacterial effect on microscale rough surface formed by fine particle bombarding. AMB Express. 31 Jan 2022;12(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard S, Hickey DJ, de Luca AC, Malheiro VN, Markaki AE, Guagliano M, et al. The influence of nanostructured features on bacterial adhesion and bone cell functions on severely shot peened 316L stainless steel. Biomaterials. Dec 2015;73:185-97. [CrossRef]

- Stevenson S, Shaffer JW, Goldberg VM. The Humoral Response to Vascular and Nonvascular Allografts of Bone: Clin Orthop. May 1996;326:86-95.

- Wagner-Golbs A, Neuber S, Kamlage B, Christiansen N, Bethan B, Rennefahrt U, et al. Effects of Long-Term Storage at −80 °C on the Human Plasma Metabolome. Metabolites. May 2019;9(5):99.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).