Submitted:

06 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

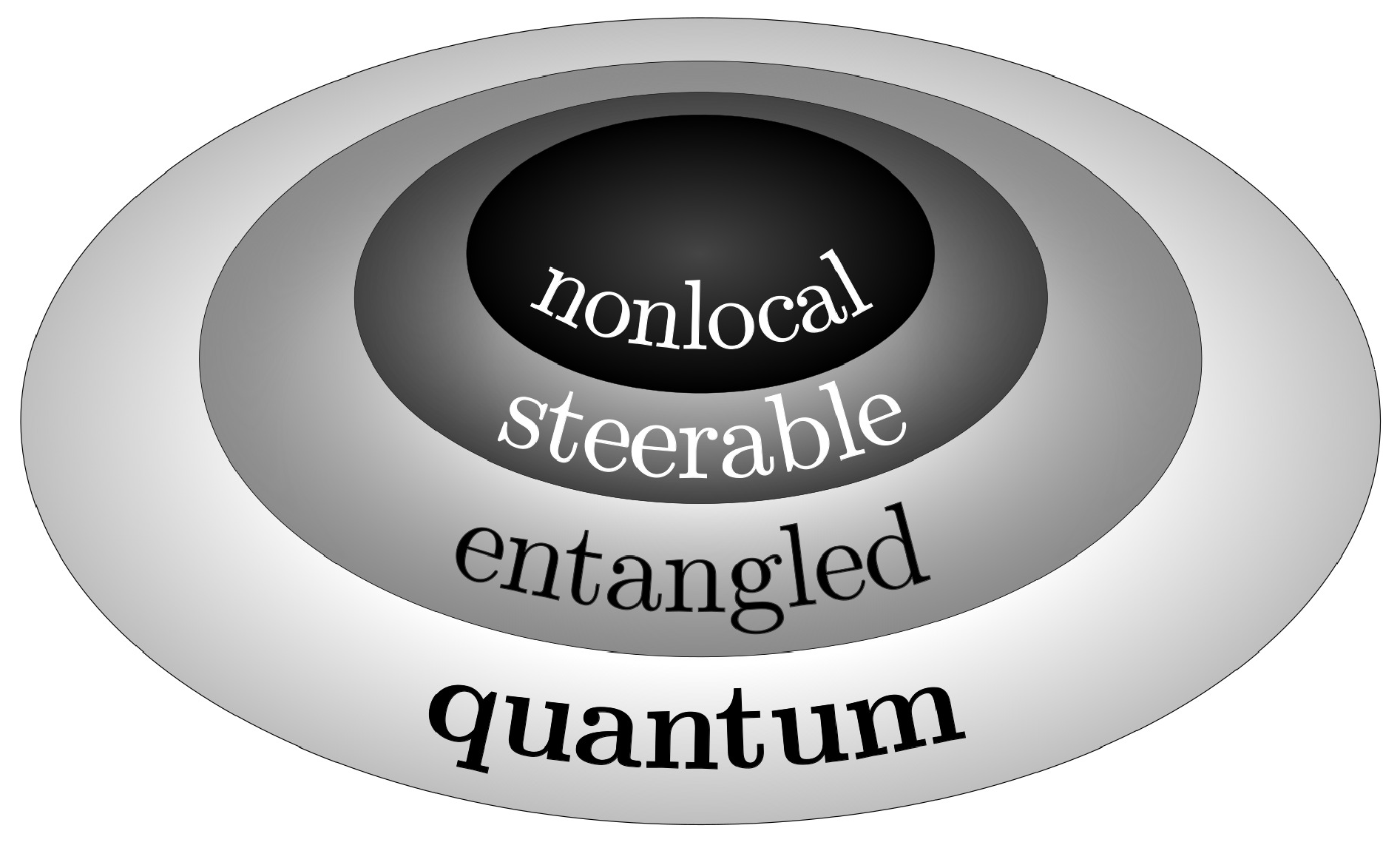

1. Introduction

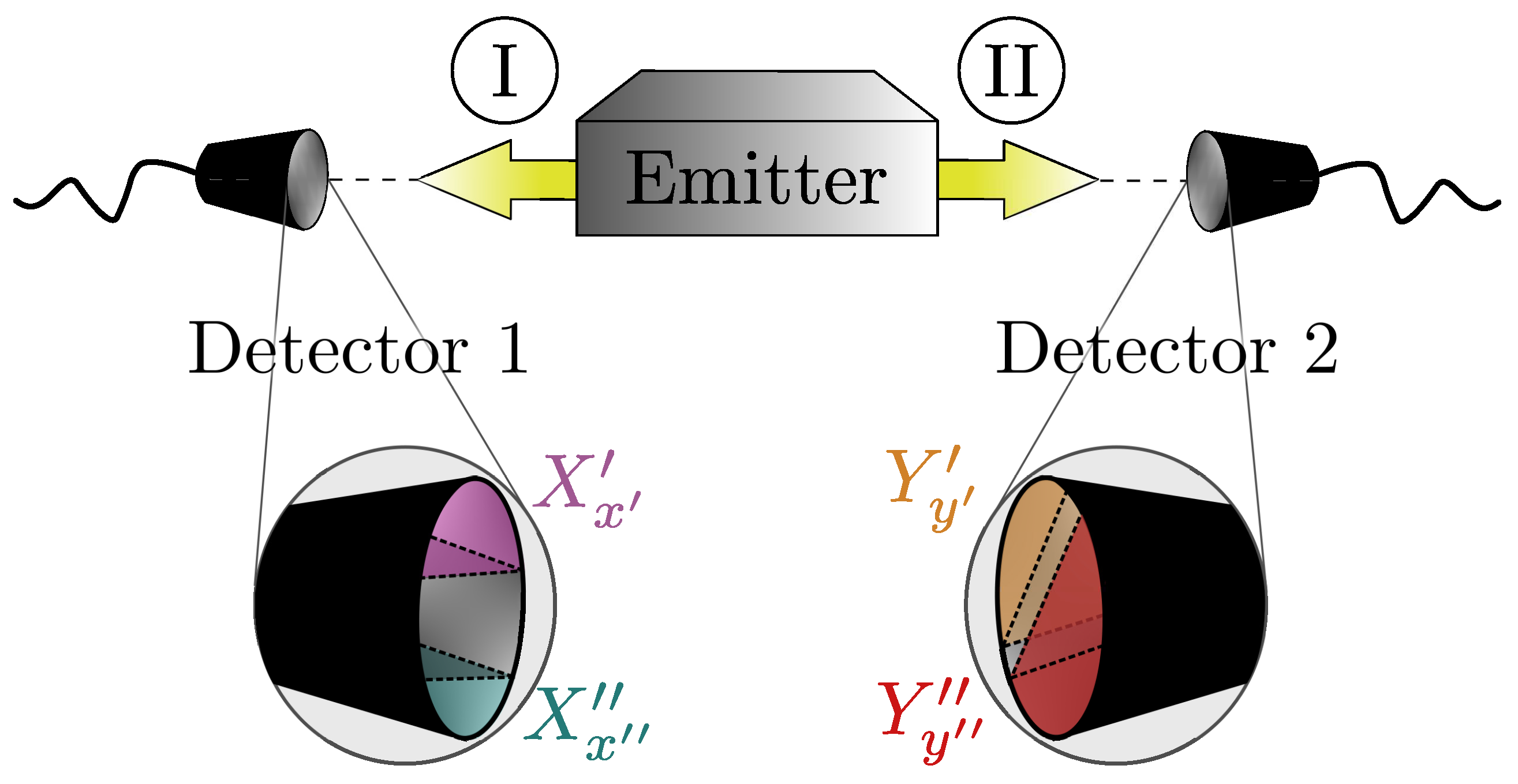

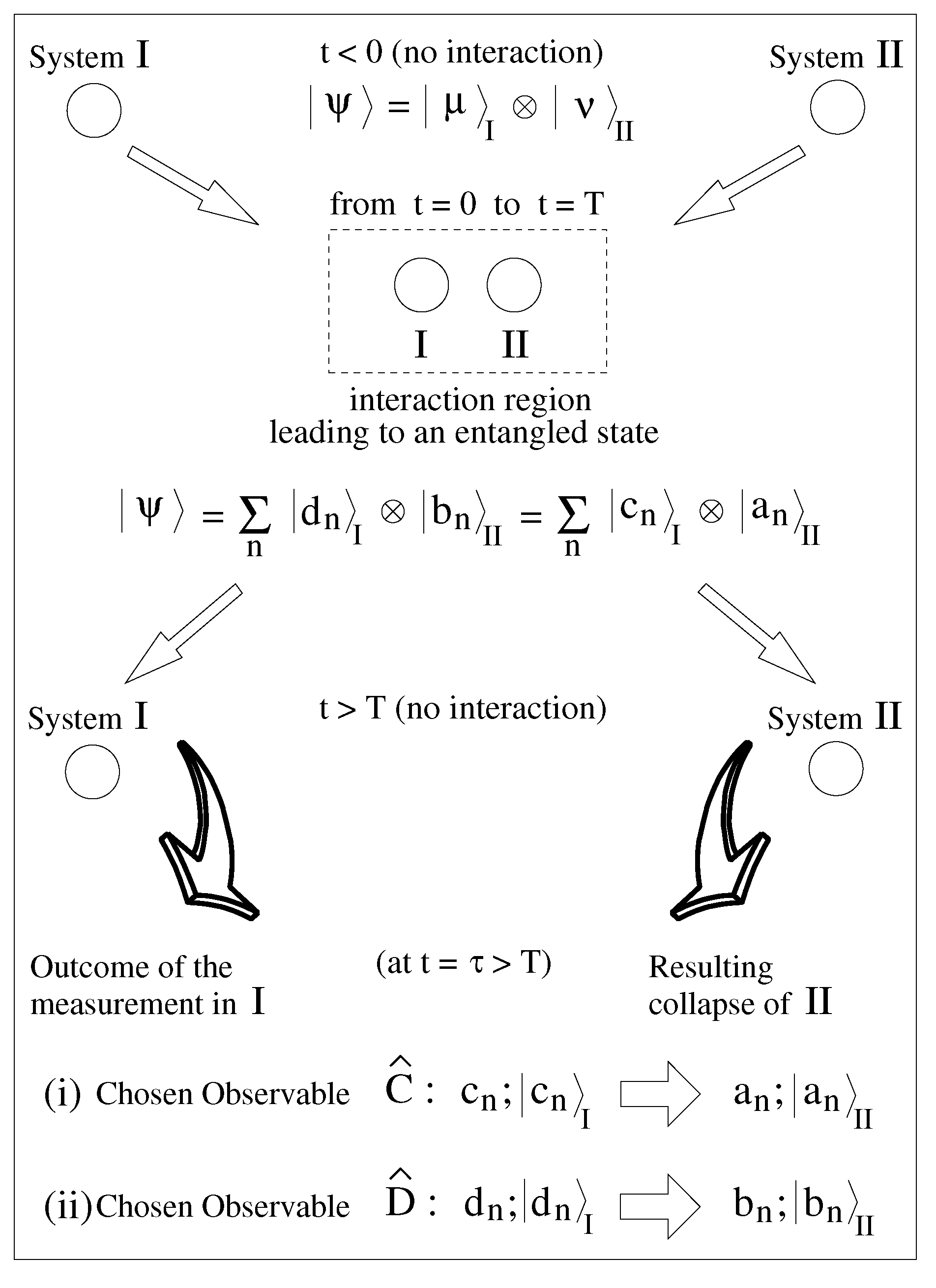

2. Some Key Aspects in Forming and Measuring EPR States

3. A Necessary Condition for EPR States: The Observables Are Pairwisely Associated to Non-Commuting Operators

3.1. Correlations in the Observables of EPR States

4. An Explicit Example: Three Levels System

- •

- (1,2) :

- •

- (2,1) :

- •

- (1,3) :

- •

- (3,1) :

- •

- (2,3) :

- •

- (3,2) :

5. EPR Observable Correlations for Qubits Do Not Violate the Bell Inequalities

6. Final Remarks and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EPR | Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen |

| CHSH | Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt |

| ONB | Orthonormal basis |

Appendix A. Transformations between Eigenbasis Associated to Commuting and Non-Commuting Operators

Appendix A.1. The Observables Assumed for EPR States

Appendix A.2. The Structure of the Transformation Matrix Γ

- and commute: (1) The operators have common eigenvectors. (2) So, in a basis in which one is diagonal, say , is block diagonal with the distinct blocks having dimensions (all finite, see Appendix A.1) equal to the multiplicity of the different eigenvalues. (3) But from the previous remarks about spectra decomposition, these blocks always can be put in a diagonal form. Therefore, there is at least one basis simultaneously diagonalizing and . As consequence of (3), in Eq. (4) can be reduced to an identity matrix of size N. Actually, in general is a permutation matrix once in Eq. (4) we can have for some subsets of indices . Nonetheless, given that for any permutation matrix , a trivial relabeling of one of the basis indices, say , gets into .

- and do not commute: (4) There are no common eigenvectors and thus no basis can simultaneously diagonalize and . (5) In this way, the matrix may (due to occasional symmetries associated to and ) or may not display a block diagonal format. However, in either situation itself or its eventual diagonal blocks cannot be turned into identity matrices, once then it would imply the existence of mutual eigenvectors, violating (4).

Appendix A.3. The Basis Transformation Matrix for Spin-1/2 Systems in Arbitrary Directions

References

- Brémaud, P. Probability theory and stochastic processes, 1st ed.; Springer Cham: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Knill, E.; Zhang, Y.; Bierhorst, P. Generation of quantum randomness by probability estimation with classical side information. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 033465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrametti, E. G. Classical versus quantum probabilities. In Chance in physics: foundations and perspectives; Bricmont, J., Ghirardi, G., Dürr, D., Petruccione, F., Galavotti M., C., Zanghi, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, R.; Masanes, L.; De La Torre, G.; Dhara, C.; Aolita, L.; Acín, A. Full randomness from arbitrarily deterministic events. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causality: models, reasoning and inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Modi, K.; Paterek, T.; Son, W.; Vedral, V.; Williamson, M. Unified view of quantum and classical correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Datta, A. Quantum versus classical correlations in Gaussian states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziero, J.; Werlang, T.; Fanchini, F. F.; Céleri, L. C.; Serra, R. M. System-reservoir dynamics of quantum and classical correlations. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 022116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Bromley, T. R.; Cianciaruso, M. Measures and applications of quantum correlations. J. Phys. A 2016, 49, 473001. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Cao, H.; Chen, Z. Distinguishing classical correlations from quantum correlations. J. Phys. A 2012, 45, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Zou, X.; Guo, G. Experimental investigation of classical and quantum correlations under decoherence. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciard, C.; Gisin, N.; Pironio, S. Characterizing the nonlocal correlations created via entanglement swapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 170401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, T. Beyond Bell’s theorem: correlation scenarios. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 14, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chiara, G.; Sanpera, A. Genuine quantum correlations in quantum many-body systems: a review of recent progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2018, 81, 074002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frérot, I.; Fadel, M.; Lewenstein, M. Probing quantum correlations in many-body systems: a review of scalable methods. arXiv preprint:2302.00640 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, D.; Skrzypczyk, P. Quantum steering: a review with focus on semidefinite programming. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2016, 80, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uola, R.; Costa, A. C. S.; Nguyen, H. C.; Gühne, O. Quantum steering. RMP 2020, 92, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics 1964, 1, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental realization of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen-Bohm gedankenexperiment: a new violation of Bell’s inequalities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A.; Grangier, P.; Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1804–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapster, P. R.; Rarity, J. G.; Owens, P. C. M. Violation of Bell’s inequality over 4 km of optical fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittel, W.; Brendel, J.; Zbinden, H.; Gisin, N. Violation of Bell inequalities by photons more than 10 km apart. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G.; Jennewein, T.; Simon, C.; Weinfurter, H.; Zeilinger, A. Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A. Quantum mechanics: to be or not to be local. Nature 2007, 446, 866–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensen, B.; Bernien, H.; Dréau, A. E.; Reiserer, A.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M. S.; Ruitenberg, J.; Vermeulen, R. F. L.; Schouten, R. N.; Abellán, C.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins separated by 1.3 kilometers. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalm, L. K.; Meyer-Scott, E.; Christensen, B. G.; Bierhorst, P.; Wayne, M. A.; Stevens, M. J.; Gerrits, T.; Glancy, S.; Hamel, D. R.; Allman, M. S.; et al. Strong loophole-free test of local realism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 250402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensen, B.; Kalb, N.; Blok, M. S.; Dréau, A. E.; Reiserer, A.; Vermeulen, R. F. L.; Schouten, R. N.; Markham, M.; Twitchen, D. J.; Goodenough, K.; et al. Loophole-free Bell test using electron spins in diamond: second experiment and additional analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, W.; Burchardt, D.; Garthoff, R.; Redeker, K.; Ortegel, N.; Rau, M.; Weinfurter, H. Event-ready Bell test using entangled atoms simultaneously closing detection and locality loopholes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, M.; Gramegna, M. Quantum correlations and quantum non-locality: A review and a few new ideas. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J. F.; Horne, M. A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R. A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 23, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodutch, A.; Modi, K. Criteria for measures of quantum correlations. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2012, 12, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slofstra, W. The set of quantum correlations is not closed. In Forum of Mathematics, Pi; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Miller C., A.; Slofstra, W. The membership problem for constant-sized quantum correlations is undecidable. arXiv preprint:2101.11087. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, A.; The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen argument in quantum theory. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2020 Edition; Zalta, E. N., (Ed.); Available online:. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/qt-epr/ (accessed on 23 april 2023).

- Bell, J. S. EPR correlations and EPW distributions. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1986, 480, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, M. D.; Drummond, P. D.; Bowen, W. P.; Cavalcanti, E. G.; Lam, P. K.; Bachor, H. A.; Andersen, U. L.; Leuchs, G. The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox: from concepts to applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 87, 1727. [Google Scholar]

- Arens, R.; Varadarajan, V. S. On the concept of Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen states and their structure. J. Math. Phys. 2000, 41, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R. F. EPR states for von Neumann algebras. arXiv preprint quant-ph/9910077 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Keyl, M.; Schlingemann, D.; Werner, R. F. Infinitely entangled states. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2003, 3, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Generalized Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen states. J. Math. Phys. 2007, 48, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- It means that the system might be described by a larger Hilbert space H⊗H′, but the observables O of interest are restricted to the subspace H. Hence, instead of H⊗H′ and O^⊗1′ one may simply consider H and O^.

- Larsson, J. A. Bell inequalities for position measurements. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 022102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D.; Aharonov, Y. Discussion of experimental proof for the paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouraddy, A. F.; Yarnall, T.; Saleh, B. E. A.; Teich, M. C. Violation of Bell’s inequality with continuous spatial variables. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 052114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, D.; Nocerino, G.; Solimeno, S.; Porzio, A. Different operational meanings of continuous variable Gaussian entanglement criteria and Bell inequalities. Laser Phys. 2014, 24, 074008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesso, G.; Illuminati, F. Entanglement in continuous-variable systems: recent advances and current perspectives. J. Phys. A 2007, 40, 7821–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustina, M.; Versteegh, M. A. M.; Wengerowsky, S.; Handsteiner, J.; Hochrainer, A.; Phelan, K.; Steinlechner, F.; Kofler, J.; Larsson, J.; Abellán, C.; et al. Significant loophole-free test of Bell’s theorem with entangled photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 250401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinfelder, H. A geometric proof of the spectral theorem for unbounded self-adjoint operators. Mathem. Annal. 1979, 242, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celeghini, E.; Gadella, M.; del Olmo M., A. Applications of rigged Hilbert spaces in quantum mechanics and signal processing. J. Math. Phys. 2016, 57, 072105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For D(H) the domain of A^ in the Hilbert space H, the norm of A^, ||A^||, is given by sup||A^|ψ〉|| with |ψ〉∈D(H) and |||ψ〉||=1. A^ is said bounded (unbounded) if ||A^|| is finite (infinite).

- Schmüdgen, K. Unbounded self-adjoint operators on Hilbert space; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D. Quantum theory, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, United States, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 48, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspers, W. J. Degeneracy of the eigenvalues of hermitian matrices. J. Phys. Conf. Series 2008, 104, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, H.; Barker, G. P. Matrices and linear algebra, 2nd ed.; Dover: Mineola, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Cirel’son, B. S. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Lett. Math. Phys. 1980, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Kaszlikowski, D.; Kwek, L. C.; Oh, C. H. Wringing out new Bell inequalities for three-dimensional systems (qutrits). Mod. Phys. Lett. A 2002, 17, 2231–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; Gisin, N.; Linden, N.; Massar, S.; Popescu, S. Bell inequalities for arbitrarily high-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 040404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, T.; Hua, B. et al. Quantum nonlocality of arbitrary dimensional bipartite states. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, P. E. T.; Kornelson, K. A.; Shuman, K. L. Iterated function systems, moments, and transformations of infinite matrices. In Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goertzen, C. M. Operations on Infinite × Infinite matrices and their use in dynamics and spectral theory. PhD Thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa City, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. S.; Noz, M. E. Theory and applications of the Poincaré group, 3rd ed.; D. Reidel Publish. Comp.: Dordrecht, Holland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Akhiezer, N. I.; Glazman, I. M. Theory of linear operators in Hilbert space; Dover: Mineola, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Halmos, P. R. A Hilbert space problem book; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, P. E. T.; Pearse, E. P. J. Spectral reciprocity and matrix representations of unbounded operators. J. Funct. Analys. 2011, 261, 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutkay, D. E.; Jorgensen, P. E. T. Fourier duality for fractal measures with affine scales. Math. Comp. 2012, 81, 2253–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, M.; Simon, B. Methods of modern mathematical physics, 1: functional analysis, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, S. Mathematical physics: a modern introduction to its foundations, 2nd ed.; Springer: Basel, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Last, Y. Quantum dynamics and decompositions of singular continuous spectra. J. Func. Anal. 1996, 142, 406–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirring, W. Quantum mathematical physics, 2nd ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teschl, G. Mathematical methods in quantum mechanics: with applications to Schrödinger operators, 2nd ed.; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- There are different ways to classify <italic>σ</italic>(<italic>A</italic>^) (see, e.g., [69]). The one here — perhaps the most appropriate in quantum mechanics — is based on the Lebesgue decomposition of a measure on <italic>R</italic> [72].

- Cycon, H. L.; Froese, R. G.; Kirsch, W.; Simon, B. Schrödinger operators with application to quantum mechanics and global geometry, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Last, Y. Exotic spectra: a review of Barry Simon’s central contributions. In Spectral theory and mathematical physics: a festschrift in honor of Barry Simon’s 60th birthday; Gesztesy, F., Deift, P., Galvez, C., Perry, P., Schlag, W., Eds.; AMS: Providence, RI, USA, 2007; pp. 697–714. [Google Scholar]

- Tchebotareva, O. An example of embedded singular continuous spectrum for one-dimensional Schrodinger operators. Lett. Math. Phys. 2005, 72, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D. Singular continuous measure in scattering theory. Comm. Math. Phys. 1978, 60, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, A.; Last, Y.; Simon, B. Modified Prfer and EFGP transforms and the spectral analysis of one-dimensional Schrodinger operators. Comm. Math. Phys. 1998, 194, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remling, C. Embedded singular continuous spectrum for one-dimensional Schrodinger operators. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 1999, 351, 2479–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actually, σpp(A^) is the closure of σp(A^) [73], hence it follows that σp(A^)⊂σpp(A^).

- Davis, E. B. Linear operators and their spectra, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- An operator A^: H→H is compact iff for any bounded sequence {|ψn〉}∈H, the sequence {A^|ψn〉} has a convergent subsequence in H (see, e.g., [70]). Any compact operator is bounded. For finite N, a self-adjoint operator is always compact.

- A bounded self-adjoint, but not compact, operator is not considered here because it is always unitarily equivalent to a certain multiplication operator [65]. And usually, multiplication operators have just generalized eigenvectors [85] (e.g., delta-functions).

- Buck, R. C. Multiplication operators. Pacific J. Math. 1961, 11, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancès, E. Introduction to first-principle simulation of molecular systems. In Computational mathematics, numerical analysis and applications; Mateos, M., Alonso, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amrein, W. O. Non-relativistic quantum dynamics, 1st ed.; D. Reidel Publishing Company: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Carreau, M.; Farhi, E.; Gutmann, S. Functional integral for a free particle in a box. Phys. Rev. D 1990, 42, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Luz, M. G. E.; Cheng, B. K. Quantum-mechanical results for a free particle inside a box with general boundary conditions. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 51, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, J.; Zanetti, F. M.; Azevedo, A. L.; Schmidt, A. G. M.; Cheng, B. K.; da Luz, M. G. E. Time-dependent point interactions and infinite walls: some results for wavepacket scattering. J. Opt. B 2005, 7, S77–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrametti, E. G.; Cassinelli, G. The logic of quantum mechanics. In Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, R. Principles of quantum mechanics, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chaichian, M.; Hagedorn, R. Symmetries in quantum mechanics; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | We are obviously not considering logical/philosophical digressions like “the sun raises every morning” and “humans are mortal”, such that A and B are true, but with no causal association between them. |

| 2 | Albeit not the goal of the present work, we mention there are some general ways to identify between classical and quantum correlations, e.g., through the idea of distance measures as relative entropy [6]. Other procedures may be problem-oriented. For instance, like those employed in the study of Gaussian states [7] or of system-reservoir interactions [8]. |

| 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).