1. Introduction

Medication therapy is the most common form of medical therapy, helping to maintain and improve the quality of life and extend life expectancy in the chronically ill. However, if used inappropriately, medications can damage health, and in the worst-case scenario end in death. Medication-related problems, also known as drug-related problems (DRPs), are defined as

an unwanted situations experienced by the patient that are caused or suspected to be caused by medication therapy and which involve or may involve problems for the desired result of the medication treatment [

1].

Clinical pharmacy is a discipline, started in the 1990’s, which purpose is to ensure effective and safe consumption of medications [

2]. Dealing with DRP is an area where clinical pharmacists can make a difference.

Today, clinical pharmacy is becoming more and more recognized [

3], however full acceptance and implementation of clinical pharmacy services in the primary and secondary healthcare sectors still requires a lot of work. The clinical pharmacy work in the primary sector (i.e. general practice and municipality care) focuses on control of the quality of the prescriptions, follow-up of medication therapy, patients' and healthcare professionals’ counseling about medications, and preparation of relevant policies and guidelines [

4]. The clinical pharmacy work in the secondary sector (i.e. hospitals) can be divided into medication surveillance services (such as ordering and stock management of medications, and training of clinical staff), and patient-level medication services, when clinical pharmacists conduct medication reviews of the patients aiming to detect and resolve DRPs [

3]. More specifically, medication review is defined as a critical review of the patient's medications to optimize medication treatment based on a patient-oriented approach and rational pharmacotherapy assessment [

5].

The research on the prevalence and burden of DRP in hospitalized patients, as well as the research on the effects of medication reviews conducted by clinical pharmacists in hospitals to deal with DRPs, is quite extensive. According to a meta-analysis conducted in 2012, 17% of all hospitalized patients are at risk of exposure to DRPs [

6], and for 0.06 to 0.20% of these patients, the DRPs are lethal [

7]. Importantly, 45 to 59% of DRPs in hospitalized patients are preventable [

8,

9,

10]. The studies, examining the effects of medication reviews in hospitalized patients conducted by clinical pharmacists, with seldom exceptions [

11], show no clear effects on hard outcomes (such as readmission and mortality), but often document that clinical pharmacists can identify, resolve and prevent DPRs overseen by hospital physicians [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

In Denmark, clinical pharmacists are employed at many hospital departments, where their job includes identification, solving, and prevention of DRP drug-related problems. On the Faroe Islands, which is an autonomous territory within Denmark, this pharmaceutical service is yet to be implemented in the hospitals. The purpose of this study was therefore to investigate the need and feasibility of a clinical pharmacy service, namely medication reviews conducted by a clinical pharmacist, for patients hospitalized at the surgical ward at the national hospital in Torshavn.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

The Faroe Islands, or simply Faroes (Danish: Færøerne), is a North Atlantic archipelago located 320 kilometers (200 miles) north-west of Scotland, and about halfway between Norway and Iceland. Like Greenland, it is an autonomous territory within Denmark. The islands have a total area of about 1400 square kilometers (540 sq miles) with a population of 52.703 as of September 2020.

The four community pharmacies on the Faroe Islands are a part of the Faroes pharmacy organization (Apoteksverk Føroya) managed by the national pharmacy (Landsapotekeren), hosting secretariat, administration and operation management (including production) and the clinical pharmacy team [

18]. The clinical pharmacy team, consisting of tree clinical pharmacists and two clinical pharmacologists, provides services for both primary and secondary care sector. The work in the primary sector includes medication reviews for citizens in nursing homes, as well as little bit of teaching and counseling for community pharmacists and other primary healthcare professionals. The work in the secondary sector includes medication surveillance services for some hospital departments, as well as teaching and counseling for healthcare professionals in the country's hospitals [

19].

The three hospitals on the Faroe Islands are a part of the Faroe hospital organization (Sjúkrahúsverk Føroya). The national hospital (Landssygehuset), located in the capital city Thorshavn, is the largest of the three hospitals; it has 21 somatic and two psychiatric wards. The surgical ward has approx. 25 beds and covers the following specializations: orthopedic, parenchymal, mammary, ear-nose-throat, and eye surgery as well as gynecology and urology. The pharmacy unit at the national hospital consists of two pharmacists and two pharmacy technicians and provides medication surveillance services to two psychiatric, three medical, and one surgical ward. The pharmacy unit staff has access to the patient's medical records.

On the Faroe Islands, there is a common patient medical record system (Cambio COSMIC [

20]) used by health professionals in primary and secondary sectors. Hence, it covers all medications prescribed and administered during hospitalization, the hospital's records, clinical data (e.g. results from blood tests), and discharge summaries (i.e. notes that the hospital doctor writes to the patient's general practitioner upon discharge). For each medication in the administration list, the dose, form, and time of administration are indicated.

2.2. Study Subjects

Patients over 65 years old of age, hospitalized in a surgical ward of the national hospital of the Faroe Islands, and having five and more prescribed medications due to multimorbidity, including medications prescribed before and during hospitalization and over-the- counter (OTC) medications, were included. Patients in a bad condition and therefore not able to contribute to their medication anamnesis, as well as those who were not capable to understand the informed consent were excluded. Patient inclusion lasted seven weeks in January-February 2021.

2.3. Study Design

The study was planned as a feasibility study with a quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the outcomes. A quantitative evaluation consisted of the collection and classification of information about DRP, and the calculation of the acceptance rate of medication changes, suggested by a clinical pharmacist. A qualitative evaluation consisted of ward staff reflections about the entire medication review process and considerations about what can be done to implement the service on a routine basis.

2.4. Medication Data Collection and Analysis

Medication information was retrieved from the hospital’s medical records system and collected in interviews with patients. First, the medical records of all patients hospitalized during a particular day were screened and an overview of potential patients to be included in the study was formed. After the morning meeting, where nurses presented the details of the hospitalized patients, this list was refined taking into account multimorbidity. The selected patients were then approached and informed about the study. Those who agreed to participate signed informed consent allowing to use their data for the study. They were later interviewed to collect supplemental medication information. Supplemental information was collected using a structured template, covering information about prescribed medication administration and compliance, OTC medications, side effects, allergies, and medication burden. Interviews with patients lasted on average 20 min.

Then, using the collected information, medications were reviewed with the help of the checklist prepared specifically for this medication review process (see

Supplementary Table S1) and consulting clinical guidelines. During the review process, DRPs were identified and classified using PCNE models for DRPs and their causes. The PCNE model differentiates DRPs into three main categories (i.e. problems related to medication effectiveness, medication safety, and others) and further six subcategories (i.e. no effect, not optimal effect, untreated symptom, adverse, unnecessary treatment, and unclear problem). The model also differentiates DRPs into actual and potential ones. Concerning causes of DRPs, the PCNE model differentiates them into eight categories: 1) medication selection; 2) medication form; 3) dose selection; 4) treatment duration; 5) dispensing; 6) medication use process; 7) patient-related, e.g. compliance; 8) patient transfer related; 9) other. The nine categories are further divided into 38 subcategories (see

Supplementary Table S2).

Proposed medication changes (e.g. initiation or discontinuation of treatment, dose change, etc.) were noted in the patient's medical records and notification was sent to the responsible physician by e-mail; selected changes were also listed, printed, and handed to a responsible physician personally. When a patient was discharged from the ward, his/her medical records were checked again, and the percentage of actually executed medication changes was calculated. This percentage is further called the acceptance rate.

2.5. Qualitative Evaluation Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative data was collected during observations of the medication review implementation process and from unstructured conversations with physicians and nurses conducted during morning meetings when delivering proposals for medication changes, and from e-mail correspondence. In the conversations and e-mails, the following subjects were discussed: what works well, what does not work well, what can be changed in the process, and any other ideas and considerations. The collected qualitative information was narrated and content analyzed.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The Faroese Data Protection Agency evaluated the study including data processing details and granted permission to use personally sensitive data. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Following Danish law, a formal ethical assessment was not needed, as the study did not use any biological material.

3. Results

3.1. Included Patients

In total, 42 patients were included in the study; 64% were men, mean (SD) age was 73 (12) years. The median (IQR) number of medications per patient was 12.5 (10-16).

3.2. Identified DRPs

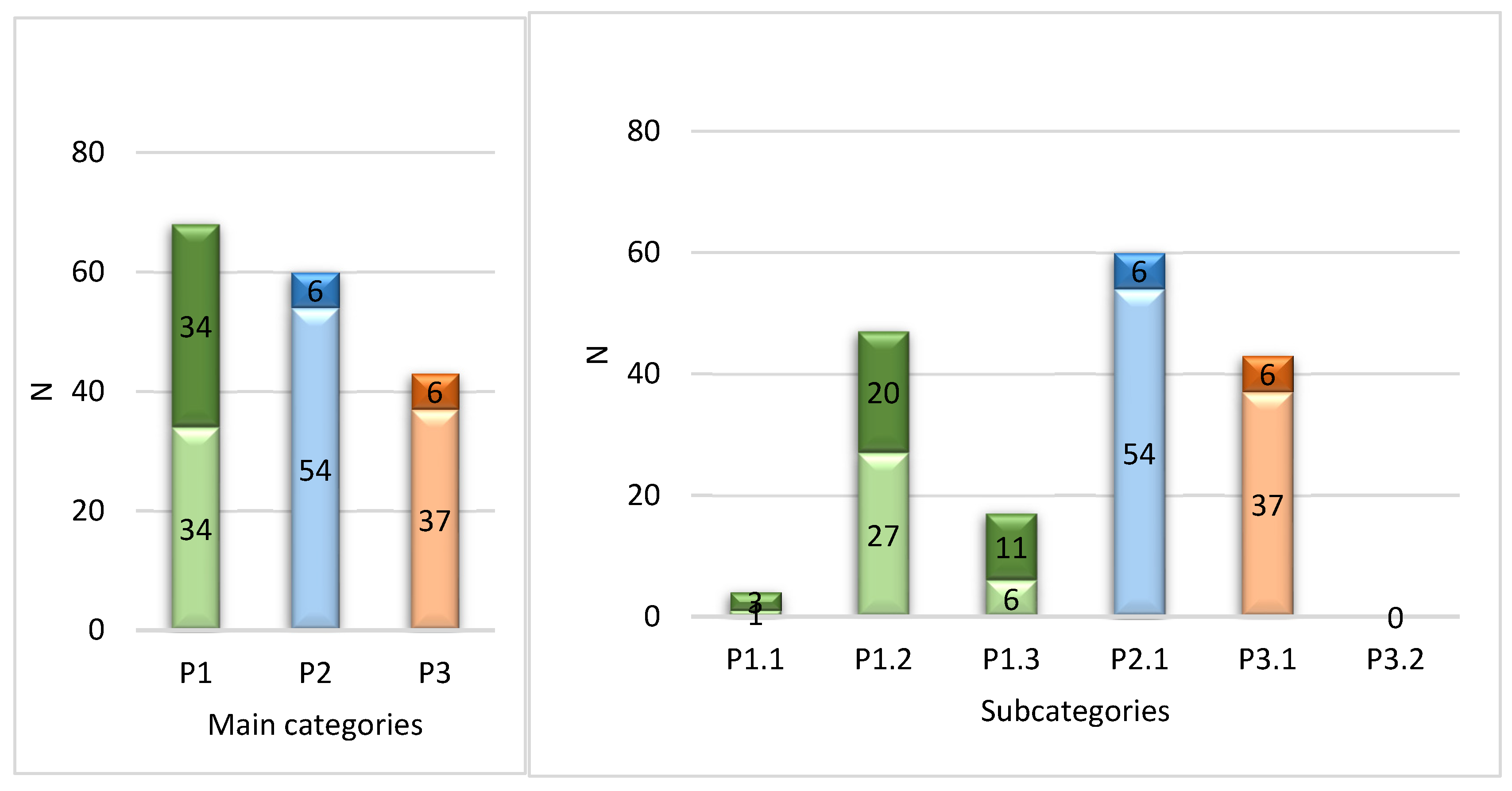

In total 171 DRPs were identified. The mean (range) of DRPs per patient was 4.1 (0-9). Out of 42, 39 patients had at least one DRP. The distribution of DRPS according to the PCNE classification is shown in

Figure 1.

According to

Figure 1, the majority of DRPs were related to medication effectiveness - 68 cases or 40% of all DRPs. Among these, the largest amount concerned suboptimal effect of the medication - 47 cases or 28% of all DRPs; followed by cases where the symptom was not treated – 17 cases or 10% of all DRPs. The safety category referring to adverse medication events was the second largest by the number of cases: 60 cases, or 35% of all DRPs. Within the

other category, all 43 cases (or 25% of all DRPS) were related to unnecessary treatment. Out of all 171 DRPs identified, 125 (73%) were assessed as potential and 46 (27%) as actual. The largest proportion of potential DRPs (i.e. 56 cases from 60) was within the medication safety category.

Table 1 shows percentages of patients with at least one DRP from a certain category. In line with the frequencies of DRPs, the largest amount of patients (79%) had suboptimal effect of the medication, followed by patients who had or could have adverse medication events (67%).

3.3. Identified DRP Causes

As one DRP can have several possible causes, a total of 190 possible DRP causes were identified. The distribution of the main categories of the DRP causes is shown in

Table 2, and the distribution of the most frequent subcategories of DRP causes is shown in

Table 3. Frequencies of DRP causes according to all 38 subcategories of the PCNE classification are displayed in Supplementary material 2.

The three most frequent categories of DRP causes were medication selection (C1, 33% of all DRP), patients’ transfer between care sectors (C8, 22% of all DRP), and dose selection (C3, 16% of all DRP). The two most frequent subcategories were medication reconciliation problems (c 8.1, 22%) and inappropriate combination of medications (C1.3, 12%). With respect to medication reconciliation, out of 42 patients, 16 (38%) had inconsistencies between medication ordinations recorded in medical records and patients’ reports of what medication they were using.

3.4. Aacceptance of Proposed Medicaion Changes by Physicians

For 36 (out of 42) patients medication changes were proposed. One patient was discharged before the medication review was finalized. For 35 (out of 36) patients the acceptance rate for proposed medicaion changes was calculated; one patient passed away shortly after medication changes were proposed, and his information was deleted from the medical records. In total, 123 medication changes were proposed, with on average 3 (range 0-9) medication changes per patient; 48 medication changes were only recorded in medical records, 75 were both recorded in medical records and delivered printed to one of the ward physicians. In total 61 (50%) of the proposed changes were accepted by the physicians. Acceptance rates by delivery mode are specified in

Table 4.

Out of 61 accepted changes, 85 % were immediately implemented in a the ward. Out of the rest 15 %, 13 % were discussed with the patient, and the patient was encouraged to talk about it with his/her general practitioner; the remaining 2 % were introduced by the physician as a note to the patient’s medical records, accessible for the personnel in the ward.

3.5. Resutls of Qualitative Evaluations

Several themes and sub-themes were identified analysing the observations, content of conversations and e-mail correspondence with the physicians and nurses, that the pharmacist conducting medication reviews narrated. The results. of the content analysis of all the qualitative inputs are summarized in

Table 5.

The physicians and nurses, who contributed to this study, first, suggested improving the visibility of a clinical pharmacist in the ward, as not all ward staff, which usually works in shifts, actually saw a clinical pharmacist. Different physicians and nurses were in the ward on different days, and there was no agreement on who, when, and how to communicate with the pharmacist about the hospitalized patients’ medications.

For a pharmacist, to conduct a proper medication review, a challenge was a lack of information on the indication of the medications prescribed during hospitalization in a ward. Moreover, a pharmacist’s note in medical records was sometimes overlooked, especially for patients, who were hospitalized for several days, a pharmacist's note was difficult to find among multiple daily notes written by both doctors and nurses.

The qualitative inputs further indicated a higher interest in interdisciplinary collaboration among younger doctors compared to the older and more experienced ones. Several younger doctors regularly praised the medication review service, while older doctors were not interested in the medications not related to a specific hospitalization. However, even with a greater interest of younger doctors in a pharmaceutical service none of the doctors, unlike nurses, spontaneously returned with good proposals on how to improve the implementation of the service. Suggestions from the physicians (such as introducing medication changes as changes in the ordinations that physicians could sign if they agreed, and sending medication changes electronically to patients’ general practitioners to become responsible for the implementation of these suggestions) were only received by confronting them with the questions.

4. Discussion

This study reports the results of a pilot project introducing a pharmacist-led medication review intervention in a surgical ward of the national hospital in the Faroe islands. The study identified the most frequent DRP in hospitalized patients, the causes of DRP, and the acceptance of the pharmacist's proposed medication changes by the ward’s physicians. The study also narrated and analysed the qualitative inputs observed by a pharmacist and expressed by the ward physicians and nurses during the medication review process. In the following, this information is reflected in terms of the needs, challenges, and possibilities when implementing a novel medication review service by a clinical pharmacist in a hospital setting in the Faroe Islands.

The categorization of the identified DRPs and their causes gives a good overview of the medication therapy areas, where pharmacist-led medication reviews could make a difference. The study showed that a pharmacist could find on average more than 4 DPRs per hospitalized patient, where DRPs related to medication effectiveness and safety were the most important ones. The latter result corresponds well with the results of the other studies where DRPs in hospitalized patients were classified using the PCNE system [

12,

13]. Moreover, from the total of 42 patients included in this study, 39 had at least one DRP. This is a clear indication that the medication lists of hospitalized patients need to be reviewed by a clinical pharmacist and that these reviews could have an impact on the quality of medication therapy in hospitalized patients. The most frequent causes of the identified DRPs - such as choice and doses of the medication, and DRPs related to care sector transfer - shows focus areas for the pharmacist-led medication review. The fact, that many DRPs were related to care sector transfer, shows the importance of pharmacists’ work in cross-sectorial settings.

The overall acceptance rate of clinical pharmacists’ proposed medication changes in this study was 49.6%. The acceptance rate of medication change proposals made by clinical pharmacists in hospitals in other similar studies varied between 39% and 89% [

13], depending on the hospital department (i.e. medical, surgical, or emergency) and the way the changes were communicated (i.e. via pharmacists’ note in hospital medical records or physically to a physician). Concerning medical departments, a Danish study from 2013, showed that physicians' acceptance rate of medication change proposed by the clinical pharmacist was higher for medical patients than for surgical patients: 69% and 51% respectively [

21]. Hence, it is possible, that the acceptance rate could be higher if the medication reviews by a clinical pharmacist were carried out in one of the medical departments of the national hospital of Faroe Island. Concerning the way the medication change proposals were communicated, this study demonstrated that the acceptance rate of the medication changes delivered exclusively via pharmacist's note in the medical record system was considerably lower compared if this change was delivered physically to one of the ward physicians: 19% and 68%, respectively. Other similar studies also showed that physically delivered proposals of medication changes can produce a far greater response among physicians than a pharmacist's note in the medical records. In the studies, where medication change proposals were communicated exclusively via pharmacists’ notes in the hospital's electronic patient record, the acceptance rate was lower (between 39% and 70% [

22,

23,

24], than in the studies, where these proposals were communicated to doctors physically with an explanation (between 69 and 89% [

25,

26,

27,

28]. In general, however, the acceptance rate in this study was on the lower end, if compared with other listed studies, which may be an indicator that current work standards and systems in the hospital do not function optimally for the implementation of medication review service by a clinical pharmacist. The physicians and nurses, who contributed to this study suggested improving the visibility of a clinical pharmacist in the ward. For a clinical pharmacist, visibility of his/her notes in the medical record system was important, as an in-person conversation about medicines with the other personnel in the ward was challenging due to an absence of standards for collaboration, and also a lack of interest in a collaboration.

The results of this pilot study suggest, that to improve possibilities for implementing a medication review service by a clinical pharmacist in a hospital ward, one would need to build up a foundation for collaborative practice between physicians and pharmacists. A clear definition of the role and communication channels for a clinical pharmacist could for both physicians and nurses in a ward be a start. Further, a pharmacy technician could help save a clinical pharmacist’s time recording medication anamnesis (including indications), which, according to a Danish study, pharmacy technicians in Denmark are qualified for [

29]. Finally, one could work further on implementing changes in the medical records system, that physicians in this study provided, e.g. investigate possibilities for a pharmacist to propose changes directly in the patient's prescription list, which the doctors could sign if they agree. This could improve the visibility of the pharmacist’s notes.

4.1. Limitations

During the pilot project, on average 1.6 hospitalized patients per day were offered a medication review service. This, however, does not reflect the real workload for a pharmacist on the ward. It is estimated that to cover the need of all hospitalized ward patients, more patients should have gotten the service. One of the reasons for that was data protection and informed consent requirements in the setting of the research project. A permanently employed pharmacist would not need a consent form to begin his/her work, and therefore, could conduct medication reviews for more patients. In this pilot, the situation means that some factors which potentially might have been important in assessing the feasibility of the service could be missed. Another limitation is that the data was collected and the medications were reviewed by one pharmacist only. This may have affected the reliability of the results. It would be an advantage if data were collected and the results of medications were reviewed by at least two pharmacists. This could also help to better reflect the applicability of the PCNE model. Finally, the lack of anonymity when collecting data for qualitative input could affect the information provided by physicians and nurses. It is possible that a supplementary anonymous questionnaire would have resulted in more extensive feedback and perhaps included more negative comments.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the feasibility of the medication review service, provided by a clinical pharmacist, in the surgical ward of the national hospital in the Faroe Islands, and showed that such a service could make a difference in the effectiveness and safety of medication therapy among hospitalized patients. As the majority of actual DRPs identified by the clinical pharmacist were associated with treatment effect, and most potential DRPs identified were associated with the safety of the treatment, a clinical pharmacist’s service could immediately improve patients' drug treatment, and in the long term prevent side effects of the treatment. The study also showed that the current work organization in the ward and the current medical record system could present challenges to the optimal implementation of the medication review service. Examples of these challenges include a lack of indication for the medications prescribed during hospitalization, poor visibility of the notes made by a pharmacist in the medical records, and a lack of physicians’ interest in interdisciplinary collaboration. Thus, to successfully implement the medication review service for hospitalized patients in the national hospital in the Faroe Islands, one needs to find innovative solutions to overcome these challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Medication Review Checklist, Table S2: DRP causes according to PCNE classification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C and N.J; methodology, M.C. and R.J; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; data curation, N.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, M.C. and N.J.; supervision, N.J. and R.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as according to Danish law this is not required for studies that do not used biological material.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be obtained by personnel request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Lamsam GD. Drug-related problems: their structure and function. DICP. 1990;24(11):1093-7. [CrossRef]

- Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533-43.

- AMGROS. Klinisk Farmaci Anno 2019. Available online: https://amgros.dk/media/2552/klinisk-farmaci-anno-2019_rapport.pdf2019 (accessed 17-03-2023).

- Lægemidelsturrelsen [National Board of Health]. Brug medicinen bedre: perspektiver i klinisk farmaci: rapport fra Lægemiddelstyrelsens arbejdsgruppe om klinisk farmaci [Use medicine better: clinical pharmacy perspectives: report from working groupd for clinical harmacy at the National Board of Health]. København [Copenhagen]: Lægemiddelstyrelsen National Board of Health]; 2004: p.1-134.

- Kjeldsen LJA, Axelsen TB, Grønkjær LS, Nielsen TRH, Nielsen DV, Væver TJ. Udvikling af patientspecifikke begreber vedrørende medicin er en udfordring for alle sundhedsprofessionelle [Developent of the concept about medicines is a challned for all healtcare proffesionals]. Ugeskrift for læger 2015 Available from: https://ugeskriftet.dk/videnskab/udvikling-af-patientspecifikke-begreber-vedrorende-medicin-er-en-udfordring-alle (accessed 16-03-2023).

- Miguel A, Azevedo LF, Araujo M, Pereira AC. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(11):1139-54. [CrossRef]

- Patel PB, Patel TK. Mortality among patients due to adverse drug reactions that occur following hospitalisation: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2019;75(9):1293-307. [CrossRef]

- Hakkarainen KM, Hedna K, Petzold M, Hagg S. Percentage of patients with preventable adverse drug reactions and preventability of adverse drug reactions--a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7(3):e33236. [CrossRef]

- Patel NS, Patel TK, Patel PB, Naik VN, Tripathi CB. Hospitalizations due to preventable adverse reactions-a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2017;73(4):385-98. [CrossRef]

- Winterstein AG, Sauer BC, Hepler CD, Poole C. Preventable drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36(7-8):1238-48. [CrossRef]

- Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert ML, Lund ML, Henriksen JP, Nielsen ML, Eriksen CS, et al. Effect of an In-Hospital Multifaceted Clinical Pharmacist Intervention on the Risk of Readmission: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(3):375-82. [CrossRef]

- Graabaek T, Hedegaard U, Christensen MB, Clemmensen MH, Knudsen T, Aagaard L. Effect of a medicines management model on medication-related readmissions in older patients admitted to a medical acute admission unit-A randomized controlled trial. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25(1):88-96. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen TR, Andersen SE, Rasmussen M, Honore PH. Clinical pharmacist service in the acute ward. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35(6):1137-51. [CrossRef]

- Bulow C, Clausen SS, Lundh A, Christensen M. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023;1(1):CD008986. [CrossRef]

- Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(2):CD008986. [CrossRef]

- Christensen M, Lundh A. Medication review in hospitalised patients to reduce morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2(2):CD008986. [CrossRef]

- Hohl CM, Wickham ME, Sobolev B, Perry JJ, Sivilotti ML, Garrison S, Lang E, Brasher P, Doyle-Waters MM, Brar B, Rowe RH, Lexchin J, Holland R. The effect of early in-hospital medication review on health outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(1):51-61. [CrossRef]

- Apoteksverkið [Pharmacies]. Bygnaður 2019 [Built 2019]. Available from: https://www.apotek.fo/um-okkum/bygna%C3%B0ur (accessed 16-03-2023).

- Apoteksverkið [Pharmacies]. Klinisk farmasi 2019 [Clinical pharmacy 1019]. Available from: https://www.apotek.fo/um-okkum/klinisk-farmasi (accessed 16-03-2023.

- Cambio COSMIC journalsystem [Cambio COSMIK journal system]. Available from: https://www.cambio.dk/vores-losninger/cambio-cosmic-journalsystem/ (accessed 16-3-2023).

- Mogensen CB, Olsen I, Thisted AR. Pharmacist advice is accepted more for medical than for surgical patients in an emergency department. Dan Med J 2013;60(8):A4682.

- Buck TC, Brandstrup L, Brandslund I, Kampmann JP. The effects of introducing a clinical pharmacist on orthopaedic wards in Denmark. Pharm World Sci 2007;29(1):12-8. [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen LJ, Birkholm T, Fischer H, Graabaek T, Kibsdal KP, Ravn-Nielsen LV, et al. Characterization of drug-related problems identified by clinical pharmacy staff at Danish hospitals. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36(4):734-41. [CrossRef]

- Lisby M, Thomsen A, Nielsen LP, Lyhne NM, Breum-Leer C, Fredberg U, et al. The effect of systematic medication review in elderly patients admitted to an acute ward of internal medicine. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106(5):422-7. [CrossRef]

- Bergkvist Christensen A, Holmbjer L, Midlov P, Hoglund P, Larsson L, Bondesson A, et al. The process of identifying, solving and preventing drug related problems in the LIMM-study. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33(6):1010-8. [CrossRef]

- Galindo C, Olive M, Lacasa C, Martinez J, Roure C, Llado M, et al. Pharmaceutical care: pharmacy involvement in prescribing in an acute-care hospital. Pharm World Sci 2003;25(2):56-64. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H, et al. A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2009;169(9):894-900. [CrossRef]

- Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 2007;370(9582):173-84. [CrossRef]

- Henriksen JP, Noerregaard S, Buck TC, Aagaard L. Medication histories by pharmacy technicians and physicians in an emergency department. Int J Clin Pharm 2015;37(6):1121-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).