Submitted:

03 July 2023

Posted:

05 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Chemical composition

3.2. Antioxidant capacity

| No | RBAC (dose) | Assay/Model | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (20, 2.0, and 0.2 mg/ml) |

Spin trapping, Fenton reaction, and ultraviolet reaction. | The ROS scavenging rates were dose-dependent against O2•- and •OH. The S fraction Biobran MGN-3 (<3,000 molecules) was the most excellent in the inhibition of •OH caused by O2•- and ultraviolet irradiation. |

Tazawa et al. (2000) [33] |

| 2. | RBEP (1g/15 ml [ORAC], 1 g/20 ml [TAS]) |

ORAC and TAS. | Both fat- and water-soluble RBEP had much higher ORAC values (446 and 326 M TE/g) than lipophilic and hydrophilic extracts from raw broccoli, broccoli seed, and sprout. RBEP had a higher TAS measurement (0.4 mmol/100g) than raw broccoli (0.18) and broccoli seeds (0.38) but not broccoli sprouts (0.56). |

An (2011) [34] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (25 mg/ kg BW i.p. 6x/day for 25 days, 19x total) |

Female Swiss albino mice (n=10 per group) | Mice treated with Biobran MGN-3 had significantly higher GSH and GPx in liver versus the control group. Biobran MGN-3 also upregulated the GPx, and CAT mRNA (p < 0.05) expression compared to the control mice. |

Noaman et al. (2008) [35] |

3.3. Absorption and effects on Peyer’s patches

3.4. Macrophage stimulation and phagocytosis

3.5. Natural killer cell activity

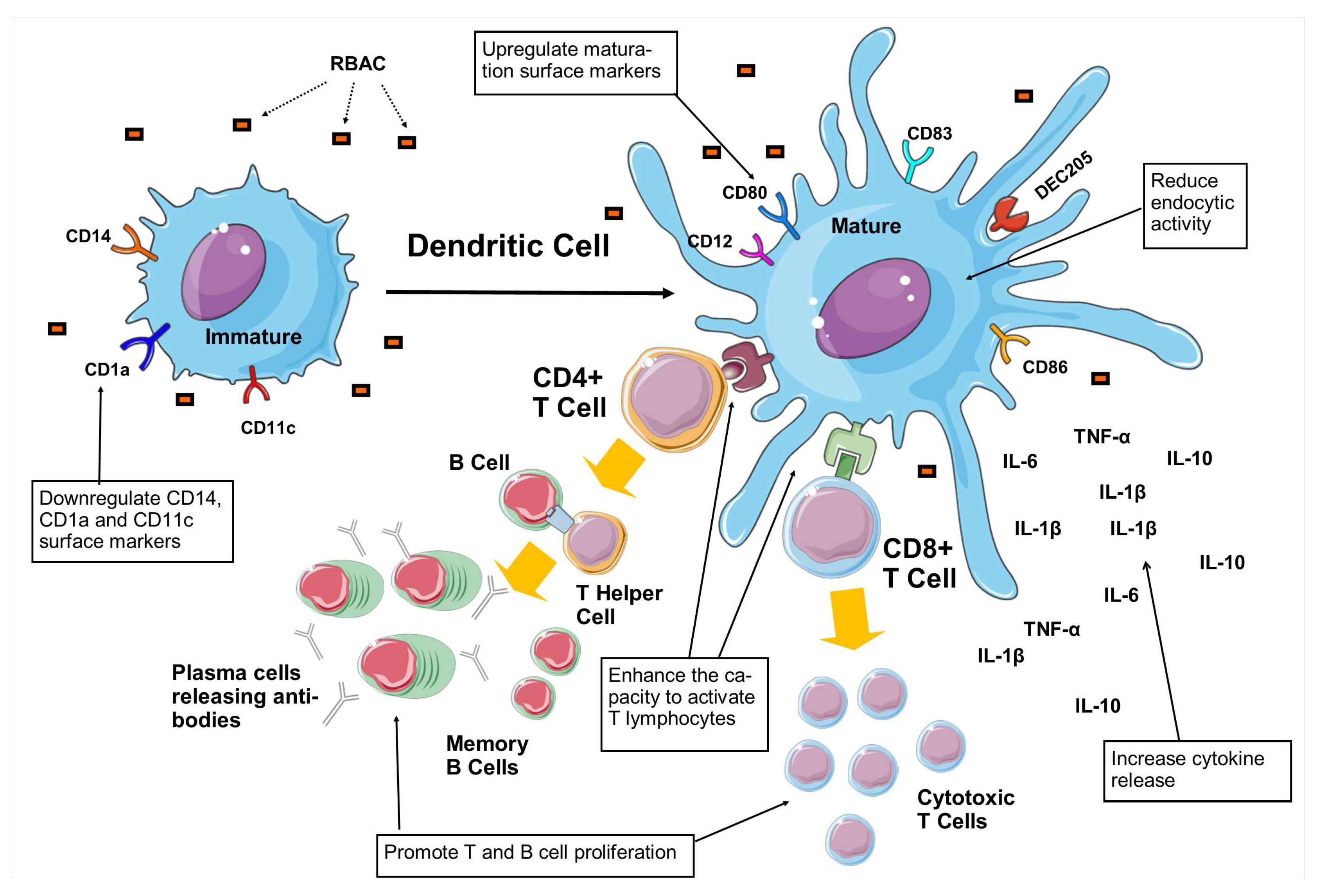

3.6. Dendritic cell maturation

3.7. T and B cell proliferation

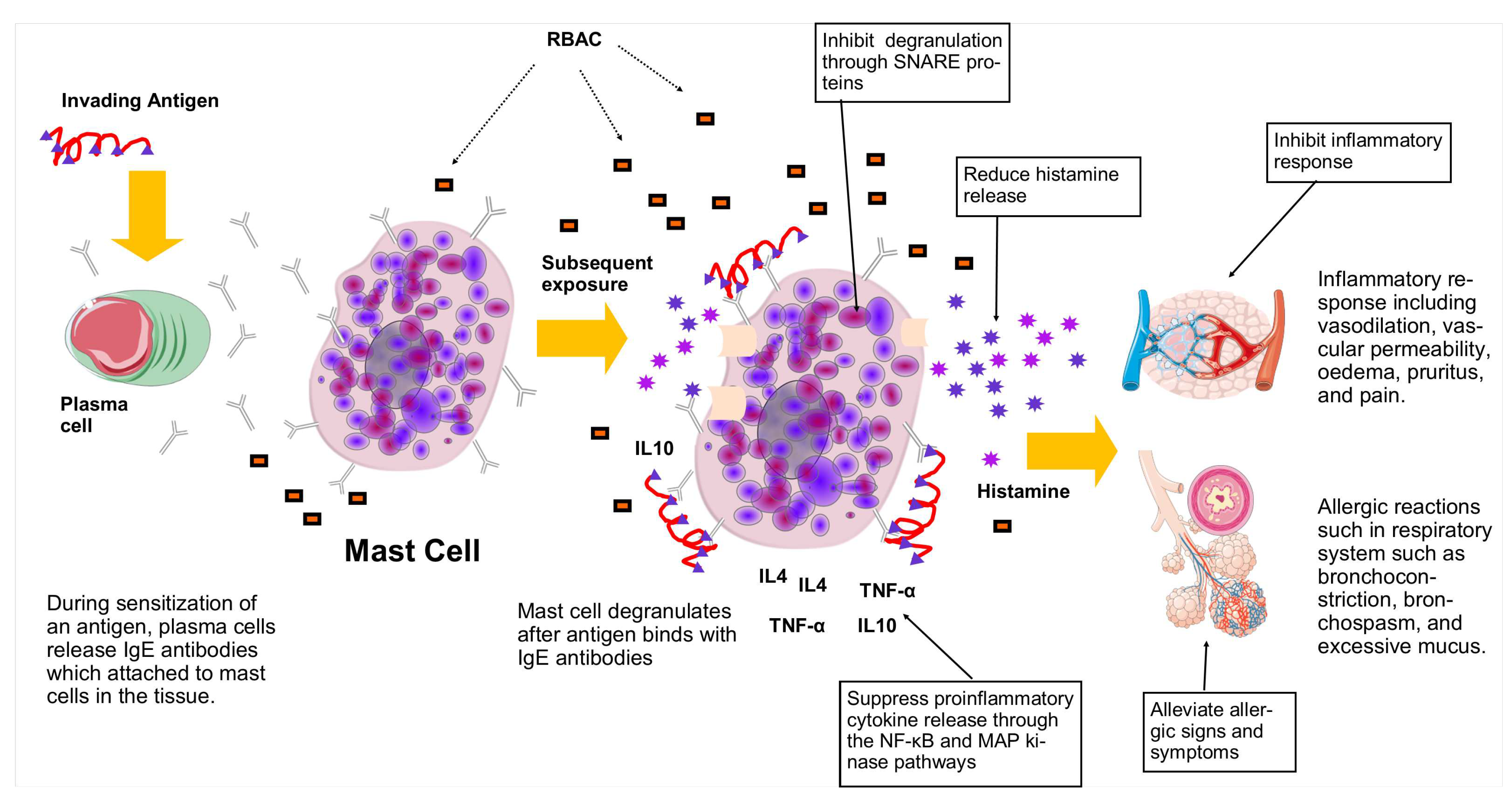

3.8. Mast cells, allergy, and inflammation

3.9. Vascular endothelial growth factor and antiangiogenic effects

3.10. Effects on circulating cytokines

3.11. Effects among older adults

3.12. Safety and adverse events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BALF | bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| BPP | Bioprocessed polysaccharides |

| BPRBE | Bioprocessed rice bran extract |

| BW | Body weight |

| CCS | Common cold symptoms |

| CFP | Fermented black rice bran |

| CMM | Cytokine maturation mix |

| CON A | Concanavalin A |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNAM | DNAX Accessory Molecule |

| DNCB | Dinitrochlorobenzene |

| EFR | Erom’s fermented rice bran |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor [EGF] |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| ICAM-1 | intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| Ig | immunoglobulin |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILI | influanza-like illnesses |

| iDC | immatured dendritic cell |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneal injection |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| LU | Lytic unit |

| MAP | Mitogen-activated protein |

| matDC | Matured dendritic cell |

| MHC-II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| mRNA | messenger Ribonucleic acid |

| NCR | Nuclear receptor coregulators |

| NF-B | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NKC | Natural kill cell |

| NKG2D | Natural killer group 2D |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical antioxidant capacity |

| PAMP | Pathogenic-associated molecular pattern |

| PBL | Peripheral blood lymphocytes |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood-derived mononuclear cells |

| PCA | Passive cutaneous anaphylaxis |

| P-M | Peritoneal macrophage |

| p.o. | Per oral |

| PSP | Polysaccharide-peptide |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RBAC | Rice bran arabinoxylan compound |

| RBEP | Rice bran exo-biopolymer |

| RCT | Randomised controlled trial |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| SNARE | Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor |

| TAS | Total antioxidant status |

| TDI | Toluene diisocyanate |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF | Tumour necrosis factor |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- McComb, S.; Thiriot, A.; Akache, B.; Krishnan, L.; Stark, F. Introduction to the immune system. In Immunoproteomics: Methods and Protocols; Fulton, K.M., Twine, S.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, K.L. Chapter 4 - Overview of the immune system. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Pittock, S.J., Vincent, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.S.; Warrington, R.; Watson, W.; Kim, H.L. An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2018, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2019, 32, e00084–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S.; Pawelec, G. The immune system and its dysregulation with aging. In Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Ageing: Part II Clinical Science; Harris, J.R., Korolchuk, V.I., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, J.J.; Bonneux, L.; Meerding, W.J.; Van Der Maas, P.J. Age-specific increases in health care costs. European Journal of Public Health 2002, 12, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, A.; Farzaneh, F.; Candore, G.; Caruso, C.; Davinelli, S.; Gambino, C.M.; Ligotti, M.E.; Zareian, N.; Accardi, G. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? A review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintapula, U.; Chikate, T.; Sahoo, D.; Kieu, A.; Guerrero Rodriguez, I.D.; Nguyen, K.T.; Trott, D. Immunomodulation in age-related disorders and nanotechnology interventions. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2023, 15, e1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranešic-Bender, D. The role of nutraceuticals in anti-aging medicine. Acta Clinica Croatica (Tisak) 2010, 49, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, S.L.; Pak, S.C. Nutraceuticals in immune function. Molecules 2021, 26, 5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, C.F.; Newman, D.J.; Tan, D.S. Cheminformatic comparison of approved drugs from natural product versus synthetic origins. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2015, 25, 4802–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Orhan, I.E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J.M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E.A.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research. Immune Health Supplements Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product, By Form, By Application, By Mode Of Medication, By Distribution Channel, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2021 - 2028. Report GVR-4-68039-548-0. Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tieu, S.; Charchoglyan, A.; Wagter-Lesperance, L.; Karimi, K.; Bridle, B.W.; Karrow, N.A.; Mallard, B.A. Immunoceuticals: Harnessing their immunomodulatory potential to promote health and wellness. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Pak, S.C.; Micalos, P.S.; Schupfer, E.; Lockley, C.; Park, M.H.; Hwang, S.J. The health-promoting properties and clinical applications of rice bran arabinoxylan modified with shiitake mushroom enzyme-a narrative review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BioBran Research Foundation. , The summary of Biobran/MGM-3. In BioBran/MGN-3 (Rice Bran Arabinoxylan Coumpound): Basic and clinical application to integrative medicine, 2nd ed.; BioBran Research Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, S.L.; McMullen, D.; Golombick, T.; Pak, S.C. Evidence-based review of BioBran/MGN-3 arabinoxylan compound as a complementary therapy for conventional cancer treatment. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2018, 17, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Micalos, P.S.; Pak, S.C. Modified rice bran arabinoxylan as a nutraceutical in health and disease – A scoping review with bibliometric analysis. Preprints.org, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Abdulmalek, S.; Fadel, H.H. Biobran/MGN-3, an arabinoxylan rice bran, protects against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): an in vitro and in silico study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajto, T.; Péczely, L.; Kuzma, M.; Hormay, E.; Ollmann, T.; Jaksó, P.; Baranyai, L.; Karádi, Z. Enhancing effect of streptozotocin-induced insulin deficit on antitumor innate immune defense in rats. Research and Review Insights 2022, 6, 1000170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Chiba, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kato, Y.; Maeda, H. BioBran Research Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2004/2013; pp. 14–22.immunoregulation. In BioBran/MGN-3 (Rice Bran Arabinoxylan Coumpound): Basic and clinical application to integrative medicine, 2nd ed.; BioBran Research Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2004/2013; pp. 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.P.; Lee, S.J.; Nam, S.H.; Friedman, M. The composition of a bioprocessed shiitake (Lentinus edodes) mushroom mycelia and rice bran formulation and its antimicrobial effects against Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 in macrophage cells and in mice. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.P.; Park, S.O.; Lee, S.J.; Nam, S.H.; Friedman, M. A polysaccharide isolated from the liquid culture of Lentinus edodes (Shiitake) mushroom mycelia containing black rice bran protects mice against a Salmonella lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2013, 61, 10987–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.W.; Shin, K.S.; Choi, Y.M.; Suh, H.J. Macrophage stimulating activity of exo-biopolymer from submerged culture of Lentinus edodes with rice bran. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 14, 658–664. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y.; Paik, D.J.; Kwon, D.Y.; Park, Y. Dietary supplementation with rice bran fermented with Lentinus edodes increases interferon-γ activity without causing adverse effects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Nutrition Journal 2014, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.A. Review: Free radicals, antioxidants, and the immune system. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2000, 30, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lugrin, J.; Rosenblatt-Velin, N.; Parapanov, R.; Liaudet, L. The role of oxidative stress during inflammatory processes. Biological Chemistry 2014, 395, 203–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacognosy Reviews 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants maintain cellular redox homeostasis by elimination of reactive oxygen species. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.M. Recent trends in chemical modification and antioxidant activities of plants-based polysaccharides: A review. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2021, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, R.; Subroto, T.; Ishmayana, S.; Kurnia, D. Enhancement methods of antioxidant capacity in rice bran: a review. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazawa, K.; Namikawa, H.; Oida, N.; Itoh, K.; Yatsuzuka, M.; Koike, J.; Masada, M.; Maeda, H. Scavenging activity of MGN-3 (arabinoxylane from rice bran) with natural killer cell activity on free radicals. Biotherapy: Official journal of Japanese Society of Biological Response Modifiers 2000, 14, 493–495. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.Y. Immune-enhance and anti-tumor effect of exo-biopolymer extract from submerged culture of Lentinus edodes with rice bran. Doctoral thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Noaman, E.; Badr El-Din, N.K.; Bibars, M.A.; Abou Mossallam, A.A.; Ghoneum, M. Antioxidant potential by arabinoxylan rice bran, MGN-3/biobran, represents a mechanism for its oncostatic effect against murine solid Ehrlich carcinoma. Cancer Letters 2008, 268, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hamid, A.; Luan, Y.S. Functional properties of dietary fibre prepared from defatted rice bran. Food Chemistry 2000, 68, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Kanbayashi, H. Modified rice bran beneficial for weight loss of mice as a major and acute adverse effect of cisplatin. Pharmacology and Toxicology 2003, 92, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, A.; Plunkett, A.; Li, W.; Tessu Gyamfi, V.E.; Nyaranga, R.R.; Fadel, F.; Dakak, S.; Ranneh, Y.; Salmon, Y.; Ashworth, J.J. Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by arabinoxylans. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2018, 42, e12473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Han, J.T.; Hong, S.G.; Yang, S.B.; Hwang, S.J.; Shin, K.S.; Suh, H.J.; Park, M.H. Enhancement of immunological activity in exo-biopolymer from submerged culture of Lentinus edodes with rice bran. Natural Product Sciences 2005, 11, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Orekhov, A.N.; Orekhova, V.A.; Nikiforov, N.G.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Romanenko, E.B.; Zhang, D.; Chistiakov, D.A. Monocyte differentiation and macrophage polarization. Vessel Plus 2019, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschoor, C.P.; Puchta, A.; Bowdish, D.M.E. , R.B., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; pp. 139–156. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-527-5_10.macrophage. In Leucocytes: Methods and Protocols; Ashman, R.B., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2012; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntjewerff, E.M.; Meesters, L.D.; van den Bogaart, G. Antigen cross-presentation by macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Nair, M.G. Macrophages in wound healing: activation and plasticity. Immunology & Cell Biology 2019, 97, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.D. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Critical Reviews in Immunology 2012, 32, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Advances in research on Immunoregulation of macrophages by plant polysaccharides. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ryu, S.N.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, S.G. In vivo immunological activity in fermentation with black rice bran. The Korean Journal of Food And Nutrition 2011, 24, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Yang, H.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, S.J.; Hong, S.G. Immunostimulatory effect of rice bran fermented by Lentinus edodes mycelia on mouse macrophages and splenocytes. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 51, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Matsuura, M. Augmentation of macrophage phagocytosis by modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3 Biobran). International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2004, 17, 283–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, S.Y.; Shin, S.H.; Bae, M.J.; Park, M.H.; Song, M.K.; Hwang, S.J.; Yee, S.T. Effect of arabinoxylane and PSP on activation of immune cells. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition 2004, 33, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Matsuura, M.; Gollapudi, S. Modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) enhances intracellular killing of microbes by human phagocytic cells in vitro. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2008, 21, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.P.; Park, S.O.; Lee, S.J.; Nam, S.H.; Friedman, M. A polysaccharide isolated from the liquid culture of Lentinus edodes (Shiitake) mushroom mycelia containing black rice bran protects mice against salmonellosis through upregulation of the Th1 immune reaction. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 2384–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Martínez, A.; Valentín, J.; Fernández, L.; Hernández-Jiménez, E.; López-Collazo, E.; Zerbes, P.; Schwörer, E.; Nuñéz, F.; Martín, I.G.; Sallis, H.; Díaz, M.; Handgretinger, R.; Pfeiffer, M.M. Arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) enhances natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity against neuroblastoma in vitro and in vivo. Cytotherapy 2015, 17, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.D. Anatomy of a discovery: M1 and M2 macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2015, 6, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, A.M.; Yang, C.; Thakar, M.S.; Malarkannan, S. Natural killer cells: development, maturation, and clinical utilization. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza Guzman, L.G.; Keating, N.; Nicholson, S.E. Natural killer cells: tumor surveillance and signaling. Cancers 2020, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, M.A. Human natural killer cells. Blood 2008, 112, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoneum, M. Enhancement of human natural killer cell activity by modified arabinoxylane from rice bran (MGN-3). Int. J. Immunother. 1998, 14, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneum, M.; Jewett, A. Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma from human peripheral blood lymphocytes by MGN-3, a modified arabinoxylan from rice bran, and its synergy with interleukin-2 in vitro. Cancer Detection and Prevention 2000, 24, 314–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneum, M.; Abedi, S. Enhancement of natural killer cell activity of aged mice by modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran). Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2004, 56, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr El-Din, N.K.; Noaman, E.; Ghoneum, M. In vivo tumor inhibitory effects of nutritional rice bran supplement MGN-3/Biobran on Ehrlich carcinoma-bearing mice. Nutrition and Cancer 2008, 60, 235–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, S.; Sabell, G.R.; Coussons-Read, M. Impact of ingestion of rice bran and shitake mushroom extract on lymphocyte function and cytokine production in healthy rats. Journal of Dietary Supplements 2008, 5, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, S.B.; Hong, S.G.; Lee, S.A.; Hwang, S.J.; Shin, K.S.; Suh, H.J.; Park, M.H. A polysaccharide extracted from rice bran fermented with Lentinus edodes enhances natural killer cell activity and exhibits anticancer effects. Journal of Medicinal Food 2007, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.H.; Melillo, A.B.; Leonard, S.M.; Asthana, D.; Woolger, J.M.; Wolfson, A.H.; McDaniel, H.; Lewis, J.E. An open-label, randomized clinical trial to assess the immunomodulatory activity of a novel oligosaccharide compound in healthy adults. Functional Foods in Health and Disease 2012, 2, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M. Immunostimulation and cancer prevention. 7th International Congress on Anti-Aging & Biomedical Technologies Dec 11-13; American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tazawa, K.; Ichihashi, K.; Fujii, T.; Omura, K.; Anazawa, M.; Maeda, H. The oral administration of the Hydrolysis Rice Bran (HRB) prevents a common cold syndrome in elderly people based on immunomodulatory function. Journal of Traditional Medicines 2003, 20, 132–141. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, H.; Ichihashi, K.; Fujii, T.; Omura, K.; Zhu, X.; Anazawa, M.; Tazawa, K. Oral administration of hydrolyzed rice bran prevents the common cold syndrome in the elderly based on its immunomodulatory action. Biofactors 2004, 21, 185–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaid, A.F.; Shaheen, M.; Ghoneum, M. Biobran/MGN-3, an arabinoxylan rice bran, enhances NK cell activity in geriatric subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2018, 15, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, A.F.; Agrawal, S.; Agrawal, A.; Ghoneum, M. Dietary supplementation with Biobran/MGN-3 increases innate resistance and reduces the incidence of influenza-like illnesses in elderly subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijs, M.J.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Professional and amateur antigen-presenting cells in type 2 immunity. Trends in Immunology 2019, 40, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flayer, C.H.; Sokol, C.L. Sensory neurons control the functions of dendritic cells to guide allergic immunity. Current Opinion in Immunology 2022, 74, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellman, I. Dendritic cells: master regulators of the immune response. Cancer Immunology Research 2013, 1, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patente, T.A.; Pinho, M.P.; Oliveira, A.A.; Evangelista, G.C.M.; Bergami-Santos, P.C.; Barbuto, J.A.M. Human dendritic cells: their heterogeneity and clinical application potential in cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholujova, D.; Jakubikova, J.; Sedlak, J. BioBran-augmented maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Neoplasma 2009, 56, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Agrawal, S. Activation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells in vitro by the biological response modifier arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran). International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2011, 24, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Agrawal, S. MGN-3/biobran enhances generation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells via upregulation of DEC-205 expression on dendritic cells. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2014, 27, 523–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, R.L.E.; Lopera, H.D.E. Introduction to T and B lymphocytes. In Autoimmunity: From Bench to Bedside; Anaya, J.M., Shoenfeld, Y., Rojas-Villarraga, A., Levy, R.A., Cervera, R., Eds.; Number 5, El Rosario University Press: Bogota, Colombia, 2013; pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, M.J.; Lee, S.T.; Chae, S.Y.; Shin, S.H.; Kwon, S.H.; Park, M.H.; Song, M.Y.; Hwang, S.J. The effects of the arabinoxylane and the polysaccharide peptide (PSP) on the antiallergy, anticancer. Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition 2004, 33, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambayashi, H.; Endo, Y. Evaluation of the effects of asthma prevention and symptom reduction by enzymatically modified rice-bran foods in asthmatic model mice [Abstract]. Japanese Journal of Allergology 2002, 51, 957–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Ryu, S.N.; Han, S.J.; Hong, S.G. Evaluation of biological activities of fermented rice bran from novel black colored rice cultivar SuperC3GHi. Korean J.Crop Sci. 2011, 56, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, Y.; Hirashima, N.; Nakanishi, M.; Furuno, T. Inhibition of degranulation and cytokine production in bone marrow-derived mast cells by hydrolyzed rice bran. Inflammation Research 2010, 59, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.Y.; Chen, A.Y.; Zhu, B.T. Mechanism of dinitrochlorobenzene-induced dermatitis in mice: role of specific antibodies in pathogenesis. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melincovici, C.S.; Boşca, A.B.; Şuşman, S.; Mărginean, M.; Mihu, C.; Istrate, M.; Moldovan, I.M.; Roman, A.L.; Mihu, C.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) - key factor in normal and pathological angiogenesis. Romanian Journal of Morphology & Embryology 2018, 59, 455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Zhao, H.; Ren, X.B. Relationship of VEGF/VEGFR with immune and cancer cells: staggering or forward? Cancer Biology & Medicine 2016, 13, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb, Y.B.; Varvara, G.; Murmura, G.; Saggini, A.; Potalivo, G.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; Tetè, S.; Tripodi, D.; Conti, F.; Cianchetti, E.; Toniato, E.; Rosati, M.; Conti, P.; Speranza, L.; Pantalone, A.; Saggini, R.; Theoharides, T.C.; Pandolfi, F. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), mast cells and inflammation. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2013, 26, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, Y. The impact of VEGF on cancer metastasis and systemic disease. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2022, 86, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Li, H.; Liu, C.; Cheng, L.; Yan, S.; Li, Y. Association of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor levels with autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 674343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, M.; Kumar, S.; Sharife, H.; Volinsky, E.; Gileles-Hillel, A.; Licht, T.; Permyakova, A.; Hinden, L.; Azar, S.; Friedmann, Y.; Kupetz, P.; Tzuberi, R.; Anisimov, A.; Alitalo, K.; Horwitz, M.; Leebhoff, S.; Khoma, O.Z.; Hlushchuk, R.; Djonov, V.; Abramovitch, R.; Tam, J.; Keshet, E. Counteracting age-related VEGF signaling insufficiency promotes healthy aging and extends life span. Science 2021, 373, eabc8479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Okubo, A.; Igari, N.; Ninomiya, K.; Egashira, Y. Modified rice bran hemicellulose inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis in vitro via VEGFR2 and its downstream signaling pathways. Bioscience of Microbiota, Food and Health 2017, 36, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; An, J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. International Anesthesiology Clinics 2007, 45, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Clevers, H. Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 2016, 529, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Rodríguez, L.; López-Hoyos, M.; Muñoz-Cacho, P.; Martínez-Taboada, V.M. Aging is associated with circulating cytokine dysregulation. Cellular Immunology 2012, 273, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, M.; Balardy, L.; Moulis, G.; Gaudin, C.; Peyrot, C.; Vellas, B.; Cesari, M.; Nourhashemi, F. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013, 14, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.O.; Kim, H.S.; Youn, J.C.; Shin, E.C.; Park, S. Serum cytokine profiles in healthy young and elderly population assessed using multiplexed bead-based immunoassays. Journal of Translational Medicine 2011, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.M.; Martins, T.B.; Peterson, L.K.; Hill, H.R. Clinical significance of measuring serum cytokine levels as inflammatory biomarkers in adult and pediatric COVID-19 cases: A review. Cytokine 2021, 142, 155478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, E.; Holmes, A.M.; Treacy, C.M.; Doughty, N.J.; Southgate, L.; Machado, R.D.; Trembath, R.C.; Jennings, S.; Barker, L.; Nicklin, P.; Walker, C.; Budd, D.C.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Morrell, N.W. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines predict survival in idiopathic and familial pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2010, 122, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, A.F.; Fahmi, R.M.; Shaheen, M.; Ghoneum, M. The enhancing effects of Biobran/MGN-3, an arabinoxylan rice bran, on healthy old adults’ health-related quality of life: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Quality of Life Research 2020, 29, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, M.A. Psychoneuroimmunological outcomes and quality of life. Transfusion and Apheresis Science 2010, 42, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Vargas Esteban, A.; Wilk, E.; Canini, L.; Toapanta Franklin, R.; Binder Sebastian, C.; Uvarovskii, A.; Ross Ted, M.; Guzmán Carlos, A.; Perelson Alan, S.; Meyer-Hermann, M. Effects of aging on influenza virus infection dynamics. Journal of Virology 2014, 88, 4123–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilich, S.R.; Bartley, J.M.; Haynes, L. Diminished immune responses with aging predispose older adults to common and uncommon influenza complications. Cellular Immunology 2019, 345, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation, B.R. , ; BioBran Research Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 9–13.Biobran/MGN-3. In BioBran/MGN-3 (Rice Bran Arabinoxylan Coumpound): Basic and clinical application to integrative medicine, 2nd ed.; BioBran Research Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mischnick, P.; Voiges, K.; Cuers-Dammann, J.; Unterieser, I.; Sudwischer, P.; Wubben, A.; Hashemi, P. Analysis of the heterogeneities of first and second order of cellulose derivatives: a complex challenge. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 843–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, S.L.; Pak, S.C.; Micalos, P.S.; Schupfer, E.; Zielinski, R.; Jeffries, T.; Harris, G.; Golombick, T.; McKinnon, D. Rice bran arabinoxylan compound and quality of life of cancer patients (RBAC-QoL): Study protocol for a randomized pilot feasibility trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications 2020, 19, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupfer, E.; Ooi, S.L.; Jeffries, T.; Wang, S.; Micalos, P.; Pak, S.C. Changes in the human gut microbiome during dietary supplementation with modified rice bran arabinoxylan compound. Preprints.org, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Research 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Mills, K.; le Cessie, S.; Noordam, R.; van Heemst, D. Ageing, age-related diseases and oxidative stress: What to do next? Ageing Research Reviews 2020, 57, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.P.P.; Sulaiman Rahman, H. Antioxidant and oxidative stress: A mutual interplay in age-related diseases. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Sanada, H.; Dohi, H.; Hirai, S.; Egashira, Y. Suppressive effect of modified arabinoxylan from rice bran (MGN-3) on D-galactosamine-induced IL-18 expression and hepatitis in rats. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2012, 76, 942–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Sugita, S.; Hirai, S.; Egashira, Y. Protective effect of low molecular fraction of MGN-3, a modified arabinoxylan from rice bran, on acute liver injury by inhibition of NF-[kappa]B and JNK/MAPK expression. International Immunopharmacology 2012, 14, 764–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoneum, M.; El Sayed, N.S. Protective effect of Biobran/MGN-3 against sporadic Alzheimer’s disease mouse model: possible role of oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021, 2021, 8845064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr El-Din, N.K.; Areida, S.K.; Ahmed, K.O.; Ghoneum, M. Arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) enhances radiotherapy in animals bearing Ehrlich ascites carcinoma. Journal of Radiation Research 2019, 60, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneum, M.; Badr El-Din, N.K.; Abdel Fattah, S.M.; Tolentino, L. Arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) provides protection against whole-body gamma-irradiation in mice via restoration of hematopoietic tissues. Journal of Radiation Research 2013, 54, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.F.S.; Flores, J.A.S. The immunomodulating effects of arabinoxylan rice bran ( Lentin ) on hematologic profile, nutritional status and quality of life among head and neck carcinoma patients undergoing radiation therapy: A double blind randomized control trial. Radiology Journal, The Official Publication of the Philippine College of Radiology 2020, 12, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.C.W.; Furman, R.; Axelsen, P.H.; Shchepinov, M.S. Free radical chain reactions and polyunsaturated fatty acids in brain lipids. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25337–25345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maeyer, R.P.H.; Chambers, E.S. The impact of ageing on monocytes and macrophages. Immunology Letters 2021, 230, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasthanam, A.S. Mechanisms underlying the inhibition of interferon signaling by viruses. Virulence 2014, 5, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgovanovic, D.; Song, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles of IFN-γ in tumor progression and regression: a review. Biomarker Research 2020, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeber, M.E.; Rosalia, R.A.; Schmid, D.; Karakus, U.; Boyman, O. Interleukin-2 signals converge in a lymphoid–dendritic cell pathway that promotes anticancer immunity. Science Translational Medicine 2020, 12, eaba5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, F.; Kamencic, H.; Juurlink, B.; Gordon, J.R.; Xiang, J. Tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) transgene-expressing dendritic cells (DCs) undergo augmented cellular maturation and induce more robust T-cell activation and anti-tumour immunity than DCs generated in recombinant TNF-α. Immunology 2003, 108, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, S.S.; Abdullah, B.J.J.; Radzuanb, N.E.I.B.M.; Zain, F.D.B.M.; Sait, N.B.M.; Chua, C.; Subramani, B. Effect of aging on NK cell population and their proliferation at ex vivo culture condition. Analytical Cellular Pathology 2018, 2018, 7871814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazeldine, J.; Lord, J.M. The impact of ageing on natural killer cell function and potential consequences for health in older adults. Ageing Research Reviews 2013, 12, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camous, X.; Pera, A.; Solana, R.; Larbi, A. NK cells in healthy aging and age-associated diseases. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2012, 2012, 195956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, V.K.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; Barnes, R.; Kelso, J.; Milne, G.J.; Blyth, C.C.; Cowling, B.J.; Moore, H.C.; Sullivan, S.G. Excess respiratory mortality and hospitalizations associated with influenza in Australia, 2007–2015. International Journal of Epidemiology 2022, 51, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, B.; Hendry, A.; Dey, A.; Brotherton, J.; Macartney, K.; Beard, F. Annual immunisation coverage report 2021. National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance: Westmead, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rottem, M.; Gershwin, M.E.; Shoenfeld, Y. Allergic disease and autoimmune effectors pathways. Developmental Immunology 2002, 9, 749841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, G. Mast cell and autoimmune diseases. Mediators of Inflammation 2015, 2015, 246126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goronzy, J.J.; Weyand, C.M. Immune aging and autoimmunity. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2012, 69, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajtó, T. Urgent necessity for standardized and evidence based plant immunomodulators (such as rice bran arabinoxylan concentrate/mgn-3) for the tumor research. International Journal of Complementary & Alternative Medicine 2017, 9, 00296–00296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RBAC | Sample | Rha | Fuc | Ara | Xyl | Man | Glc | Gal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biobran | Fr II | 1.0 | 0.2 | 23.0 | 15.1 | 2.0 | 48.1 | 10.7 |

| MGN-3 | Fr I-4 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 22.5 | 19.4 | 4.7 | 26.7 | 25.2 |

| Fr I-5 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 22.2 | 14.8 | 3.5 | 32.2 | 23.9 | |

| Fr I-6* | 7.6 | 0.6 | 22.2 | 13.7 | 2.7 | 30.2 | 23.0 | |

| Fr III | 1.9 | 5.9 | 15.7 | 7.5 | 1.3 | 30.1 | 37.8 | |

| Fr IV | - | - | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 89.2 | 4.0 | |

| RBEP | 1 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 21.8 | 9.0 | 22.9 | 22.0 | 18.6 |

| 2 | NR | NR | Trace | 22.25 | NR | 11.71 | Trace | |

| BPP | 2.7 | 0.8 | NR | 3.0** | 18.2 | 9.1 | ||

| BPRBE | NR | NR | NR | 0.59 | 10.8 | 0.09 | 55.1 | |

| NPRBE*** | NR | NR | NR | - | - | 0.17 | - | |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Cell type | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Enhance lysosomal enzyme production | ||||

| 1. | RBEP (10 and 100 g/ml) |

P-M (in vitro) |

RBEP showed the highest stimulating activity in both concentrations compared to 8 other rice bran extracts cultured with different fungi. The levels were similar to LPS at 10 g/ml and higher at 100 g/ml. |

Yu et al. (2004) [24] |

| 2. | RBEP (10 and 100 g/ml) |

P-M (in vitro) |

Both doses (10 and 100 g/ml) elicited more than twice the control activity level, similar to the levels of LPS under the same amount. |

Kim et al. (2005) [39] |

| 3. | RBEP (50 and 250 mg/kg BW p.o.) |

P-M (in vivo) |

Dose-dependent (1.41- and 1.44-fold) increases in lysosomal enzyme activity were recorded compared to the control in P-M extracted from mice fed with REBP for 5 days. |

Kim et al. (2005) [39] |

| 4. | CFP (250 mg/kg BW p.o. for 4 weeks) |

P-M (in vivo) |

Lysosomal enzyme activity was 104.60±10.97% relative to control. The secondary fermented products either increased (CFP-S, 115.21±18.94%) or decreased activities (CFP-L, 97.99±16.79%). The activities of CFP and CFP-L were significantly enhanced (p<0.05) in the presence of LPS but reduced in the case of CFP-S. |

Kim et al. (2011) [46] |

| 5. | BPP (10 and 100 g/ml) |

P-M (in vitro) |

BPP could increase the lysosomal enzyme activity by ∼5.4-fold at 10 g/ml and ∼2.5-fold at 100 g/ml, compared to the polysaccharides of L. edodes alone. At 100 g/ml, BPP also exhibited a higher activity than LPS. |

Kim et al. 2013 [23] |

| 6. | EFR (0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 g/ml) |

P-M (in vitro) |

Significant increases in enzyme activity relative to the control were observed (134.9-142.2% at different concentrations, p<0.05). Such levels are at par with the 135.8% increase demonstrated by LPS. |

Kang et al. (2022) [47] |

| B. Increase phagocytosis rate | ||||

| 7. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10 and 100 g/ml) |

U937, RAW264.7, and P-M (in vitro) |

Biobran MGN-3 enhanced the rate of attachment and phagocytosis of yeast in a dose-dependent manner, with responsiveness varied across cell types. |

Ghoneum & Matsuura (2004) [48] |

| B. Increase phagocytosis rate(Cont.) | ||||

| 8. | Biobran MGN-3 (1.5 mg/l p.o. for 10 days) |

P-M (in vivo) |

The phagocytic activity of P- Mtreated with Biobran MGN-3 (69%) was comparable with those with PSP (65%) treatment against Candida parapsilosis, and both were significantly higher (p<0.05) than the control (47%). |

Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| 9. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml) |

Human PBL (in vitro) |

Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml) significantly enhanced (p<0.01) the phagocytosis of Escherichia coli by monocytes (110%) and neutrophils (400%) compared to the control. Increased oxidative burst with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of E. coli was observed. |

Ghoneum et al. (2008) [50] |

| 10. | BPP (1, 10 and 100 g/ml) |

RAW 264.7 (in vitro) |

Bacterial uptake rates against Salmonella typhimurium increased by 1.4-, 2.4-, and 3.5-fold in a dose-dependent manner compared to untreated macrophages. A greater intracellular bacteria presence after 2 hours compared to the control, but the bacterial count decreased after 4 and 8 hours relative to the control. |

Kim et al. (2014) [51] |

| 11. | BPP (10 mg/kg BW p.o. & i.p.) |

P-M (in vivo) |

Pretreatment with BPP (p.o. and i.p.) for 14 days significantly reduced (p<0.05) S. typhimurium count in the peritoneal cavity of the infected mice. |

Kim et al. (2014) [51] |

| 12. | BPRBE (1, 10 and 100 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Dose-dependent increases in phagocytotic rates against S. typhimurium at 1.3-, 2.3-, and 3.4-fold compared to the control were observed. |

Kim et al. (2018) [22] |

| C. Induce NO production | ||||

| 13. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100 and 1000 g/ml) |

P-M (in vitro) |

Crude Biobran MGN-3 induced NO production in general, but different fractions of Biobran MGN-3 yielded NO differently at a dose-dependent rate. |

Miura et al. (2004) [21] |

| 14. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100 and 1000 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Biobran MGN-3 and PSP were observed to increase NO production compared to the control, but Biobran MGN-3 appeared less effective than PSP. |

Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| 15. | BPRBE (1, 10 and 100 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

NO production significantly increased relative to both passive control and non-bioprocessed rice bran extract for all doses and LPS for doses 10 g/ml. Increased iNOS (∼1.9 fold) expression was detected. |

Kim et al. (2018) [22] |

| 16. | EFR (0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

A dose-dependent significant increase (p<0.05) in NO production was observed compared to control with an associated increase in iNOS expression. The level of NO production in 8 g/ml of EFR was comparable to that of 1 g/ml of LPS. |

Kang et al. (2022) [47] |

| D. Influence cytokine secretion | ||||

| 17. | Biobran MGN-3 (1000 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Biobran MGN-3 induced higher levels of IL-6 and TNF- production than control but much less than the levels influenced by PSP and LPS. |

Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| 18. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100 and 1000 g/ml) |

U937 (in vitro) |

Dose-dependently increases of TNF-, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 production with significant (p<0.01) differences observed at 10 g/ml compared to control. |

Ghoneum et al. (2008) [50] |

| 19. | Biobran MGN-3 (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 g/ml) |

Human macrophages (in vitro) |

Only higher levels of Biobran MGN-3 (10 g/ml and above) resulted in the release of of IL-8, IL-6 and TNF- but significantly lower than LPS. |

Pérez-Martínez et al. (2015) [52] |

| 20. | BPRBE (100 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Treatment markedly induced (p<0.05) IFN- production in the Salmonella-infected macrophage cells via the IFR3 pathway. |

Kim et al. (2018) [22] |

| 21. | EFR (0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Significant increases (p<0.05) in the secretion of IL-1, IL-10, IL-6, and TNF- compared to the control in a dose-dependent manner. |

Kang et al. (2022) [47] |

| E. Cross-presenting of antigens | ||||

| 22. | Biobran MGN-3 (1000 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

Biobran MGN-3 increased the MHC-II expression compared to the control but at a level lower than PSP, LPS, and IFN-. |

Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| 23. | BPP (100 g/ml) |

RAW 264.7 (in vitro) |

BPP-treated cells showed dendrite-like morphological changes, reaching up to 3.6-, 10.3-, and 12.4-fold changes after 2, 4, and 8 hours of incubation. |

Kim et al. (2014) [51] |

| F. Activate autophagy | ||||

| 24. | BPRBE (100 g/ml) |

RAW264.7 (in vitro) |

BPRBE treatment was found to upregulate the expression of the autophagy-related proteins (Beclin-1, Atg5, Atg12, Atg16L) regardless of bacterial infection. |

Kim et al. (2018) [22] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Model | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Enhance NKC cytotoxicity (chromium assay) | ||||

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (25 and 100 g/ml) |

PBL from healthy human donors (n=6) |

Biobran MGN-3 significantly increased (p<0.001) NKC cytotoxicity in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (130% at 25 g/ml vs 150% at 100g/ml). |

Ghoneum (1998) [57] |

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 g/ml) |

PBL and purified NKC from healthy human donors (n=25) |

Significant increases in NKC cytotoxicity in both PBL (p<0.001) and purified NKC (p<0.01) by Biobran MGN-3. The NKC augmentation effect of Biobran MGN-3 was enhanced by co-culturing with IL-2 (500 U/ml) in PBL but not in purified NKC. |

Ghoneum & Jewett (2000) [58] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (10 mg/kg BW, i.p. or p.o. daily) |

Aged C57BL/6 and C3H female mice |

Biobran MGN-3 i.p. significantly increased peritoneal NKC activity (4.8 – 6-fold, p<0.01) from day 2 to 14 but not splenic NKC activity. However, oral feeding of Biobran MGN-3 elicited a 200% increase (p<0.01) in splenic NKC activity but not peritoneal NKC activity. |

Ghoneum & Abedi (2004) [59] |

| 4. | Biobran MGN-3 (25 and 100 g/ml) |

Splenic lymphocytes from aged C57BL/6 mice |

In vitro NKC activity exhibited a 4-fold increase (p<0.01) over the control after culturing with Biobran MGN-3. |

Ghoneum & Abedi (2004) [59] |

| A. Enhance NKC cytotoxicity (chromium assay)(Cont.) | ||||

| 5. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml i.m. daily) |

Young Swiss albino mice |

The treated mice showed a significant increase in splenic NKC activity (27.1 LUs vs .3 Lus, p<0.01) compared to the control after 14 days. |

Badr El-Din et al. (2008) [60] |

| 6. | Biobran MGN-3 (250mg/day p.o.) |

Male Lewis rats |

Rats fed with Biobran MGN-3 as a dietary supplement showed significantly enhanced splenic NKC activity (p<0.045) compared to rats fed with only a control diet after two weeks. |

Giese et al. (2008) [61] |

| 7. | RBEP (50 mg/kg or 250 mg/kg, p.o. daily) |

Male ICR mice |

RBEP was shown to enhance the splenic NKC activity significantly after 5 days, reporting 32.8 LUs (50 mg/kg, p<0.05) and 46.3 LUs (250 mg/kg, p<0.01) compared to the 22.8 LUs of the controls. |

Kim et al. (2007) [62] |

| 8. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml) |

NKC isolated from PBL of healthy donors |

Significant increases (p<0.05) in NKC cytotoxicity against 7 different tested cell lines compared to resting NKC with overnight in vitro stimulation of Biobran MGN-3, although the levels were lower than IL-5 (10 ng/ ml) stimulated NKC. Biobran MGN-3 also synergistically enhanced the stimulatory effect (p<0.05) of low-dose IL-2 (40 IU/ml) on NKC cytotoxicity level to that obtained with 1000 IU/ml of IL-2. | Pérez-Martínez et al. (2015) [52] |

| B. Elevate NKC activity (other indicators) | ||||

| 9. | Biobran MGN-3 (10 mg/kg BW, i.p. daily) |

C57BL/6 mice (n=3) |

A remarkable increase in BLT-esterase activity (p<0.01) and granularity after 5 days of i.p. was detected. The binding capacity of peritoneal NKC also significantly increased with higher percentage conjugates (26% vs. 13%, p<0.01) compared to the control. |

Ghoneum & Abedi (2004) [59] |

| 10. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml, i.m. daily) |

Young Swiss albino mice |

A two-fold increase (27.5% vs. 14%, p<0.01) in the splenic NKC binding capacity in the percentage of conjugate formation to target cells was detected after 14 days. |

Badr El-Din et al. (2008) [60] |

| C. Increase cytokine production | ||||

| 11. | Biobran MGN-3 (25, 50 and 100 g/ml) |

PBL from healthy human donors (n=6) |

Biobran MGN-3 also increased IFN- production significantly (p<0.001), showing 340, 390, and 580 pg/ml of IFN- production at 25, 50, and 100 g/ml, respectively, compared to <100 pg/ml in control. |

Ghoneum (1998) [57] |

| 12. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100 and 1000 g/ml) |

PBL and purified NKC from healthy human donors (n=25 for TNF-, n=14 for IFN-) |

Biobran MGN-3 at higher concentrations (100 and 1000 g/ml) significantly increased TNF- (p<0.001) and IFN- (p<0.03) secretions in PBL with variations across samples. IL-2+Biobran MGN-3 further enhanced TNF- secretion by PBL but not purified NKC. A synergistic effect of IL-2+Biobran MGN-3 on IFN- production by purified NKC was detected. |

Ghoneum & Jewett (2000) [58] |

| 13. | Biobran MGN-3 (250mg/day p.o.) |

Male Lewis rats (n=24) |

Significant elevations of IL-2 (p<0.05) and IFN- (p<0.08) production after 14 days in splenocytes of rats fed with Biobran MGN-3 compared to control. |

Giese et al. (2008) [61] |

| D. Expression of cell surface markers | ||||

| 14. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 and 1000 g/ml) |

PBL from healthy human donors (n=25) |

Upregulation of CD69, CD54, and CD25 was observed in NKC after Biobran MGN-3 treatment at levels comparable to IL-2-stimulated NKC. |

Ghoneum & Jewett (2000) [58] |

| 15. | Biobran MGN-3 (100 g/ml) |

NKC isolated from PBL of healthy donors |

NKC stimulated with Biobran MGN-3 showed increased expression of CD69 and CD25 by 3.1-fold and 3.2-fold over resting NKC, respectively. |

Pérez-Martínez et al. (2015) [52] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Participants | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (15, 30, 45 mg/kg BW/day for 2 months) |

Healthy adults (n=24, 8 in each group) |

Significantly enhanced NKC cytotoxicity was achieved at 1 week (∼3.1-fold, p<0.001) for 30 and 45 mg/kg doses and after 1 month (2-fold) for 15 mg/kg. Peak response was achieved after 2 months (∼5-fold) for all doses and returned to baseline after 1 month of discontinuing treatment. The percentage of conjugate formations increased significantly over baseline (38.5% vs 9.4%, p<0.005) after 1 month at 45 mg/kg dose. |

Ghoneum (1998) [57] |

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (15 mg/kg BW/day for 4 months) |

Adults with workplace chemical exposure (n=11) |

The participants had low levels of NKC activity (10.2±4.2 LUs) at baseline, but treatment with MGN-3 increased NKC activity 4- and 7-fold at 2 and 4 months, respectively. T and B cell functions were 130-150% higher than base line values. |

Ghoneum (1999) [64] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 mg/day for 2 weeks with cross-over) |

Older adults (age 75-90, n=31) |

There was no significant difference in NKC activity before and after the study and across intervention periods. A secondary analysis showed that those with low NKC activity at baseline (n=12, ≤30%) had higher activity during treatment compared to the control (↑34.1% vs 15.6%). |

Tazawa et al.(2003) [65] Maeda et al. (2004) [66] |

| 4. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 3 g/day for 60 days) |

Healthy adults (n=20, 10 in each group) |

A significant effect of time (p=0.001) on the NKC activity was detected but not for the group and the interaction of group and time. Total NKC activity peaked at 1 week and was significantly higher than the values at other time points (0, 48 hours, 30 and 60 days). |

Ali et al. (2012) [63] |

| 5. | RBEP (3g/day or placebo for 8 weeks) |

Healthy adults (n=80, 40 in each group) |

No significant effect of RBEP supplementation on NKC activity over placebo at all time points (0, 4, 8 weeks) |

Choi et al. (2014) [25] |

| 6. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 mg/day for 1 month) |

Older adults (age ≥56, n=12, 6 in each group) |

The median CD107a expression (NKC activity) in the Biobran MGN-3 group significantly increased from 60.5% to 83.0% after 1 month (p<0.046), with no significant differences detected in the placebo group. |

Elsaid et al. (2018) [67] |

| 7. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 mg/day for 3 month) |

Older adults (age ≥56, n=12, 6 in each group) |

Mean NKC CD107a expression significantly increased (p=0.004) from 49.5±10.4% to 75.2±6.6% for the Biobran MGN-3 group compared to an insignificant difference in the placebo group (45.3±12 vs 50.8±19.5). |

Elsaid et al. (2021) [68] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Cell Type | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Induce DC maturation | ||||

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (10, 100, 400 and 1000 g/ml) |

Monocytes isolated from buffy coats of healthy donors. |

BioBran MGN3 downregulated the CD14 and CD1a on the surface of iDC while markedly increasing CD80, CD83, and CD86 expressions. Also, BioBran MGN-3 decreased CD11c surface antigen and increased CD123. |

Cholujova et al. (2009) [73] |

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (5, 10 and 20 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

Flow cytometry analysis showed a dose-dependent upregulation in CD83 and CD86 surface markers similar to the effects of LPS on DC. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2011) [74] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (20 and 40 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

BioBran MGN3 showed signs of maturation with increased DEC-205 expression for antigen-presenting in a dose-dependent manner. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2014) [75] |

| B. Reduce endocytic activity | ||||

| 4. | Biobran MGN-3 (100, 400 and 1000 g/ml) |

Monocytes isolated from buffy coats of healthy donors. |

BioBran MGN3 reduced the endocytic activity of iDC from 73% to 27.7% (100 g/ml), 17.7% (400 g/ml), and 14.4% (1000 g/ml) under different concentrations, approaching the levels of mDC. |

Cholujova et al. (2009) [73] |

| C. Stimulate cytokine secretion | ||||

| 5. | Biobran MGN-3 (5, 10 and 20 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

BioBran MGN3 treated DC produced significantly higher levels (p<0.05) of IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, and IL-2, compared to untreated DC. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2011) [74] |

| 6. | Biobran MGN-3 (10 and 20 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

Treatment of 20 g/ml of BioBran MGN3 significantly increased IL-29 production in DC (p<0.05) compared to the control. Increased secretion of IFN- and - were also detected but did not achieve statistical significance. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2014) [75] |

| D. Enhance the capacity to activate T lymphocytes | ||||

| 7. | Biobran MGN-3 (10 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

Co-culturing of DC pretreated with 10 g/ml BioBran MGN3 with allogeneic CD4+T cells increased the proliferation by 1.4 fold and CD25 marker expression by 1.3 fold, compared to those cultured with untreated DC. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2011) [74] |

| 8. | Biobran MGN-3 (20 g/ml) |

Monocyte-derived DCs |

Culturing the activated DC (by BioBran MGN3) with purified, allogeneic CD8+T cells resulted in significantly higher levels of granzyme B-positive CD8+ T cells (p<0.05) with increased cytotoxicity against tumour cell targets (p<0.05), compared to control. |

Ghoneum & Agrawal (2014) [75] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Cell Type | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Increase plague and rosette formation | ||||

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (1.5 mg/day p.o. for 10 days) |

Splenocytes from BALB/c mice |

Rosette formation due to higher antibody production increased by 30% over control (p<0.005). Splenocyte plague formation was also highest in the Biobran MGN-3 group, with a 14% increase over the control group. |

Bae et al. (2004) [77] Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| B. Enhance splenocyte proliferative activity | ||||

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100, 1000 g/ml) |

Splenocytes from BALB/c mice |

Biobran MGN-3 induced splenocyte proliferation in a dose-dependent manner at a much lower level than LPS, Con A and PSP. Biobran MGN-3 also induced IFN- secretion like LPS in splenocytes. |

Bae et al. (2004) [77] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (10 mg/kg BW/day, i.p. or p.o. for 2,5, & 14 days) |

Splenocytes from aged C57BL/6 and C3H female mice |

Biobran MGN-3 significantly increased splenic cellularity in both strains of mice by 145 to 192% (p<0.025) compared to the control. |

Ghoneum & Abedi (2004) [59] |

| 4. | RBEP (10, 100 g/ml) |

Splenocytes from ICR mice |

A 1.39- to 1.44-fold increase in cell proliferation levels in vitro relative to untreated control was detected. The levels were lower compared to that produced with LPS and Con A. |

Kim et al. (2005) [39] |

| 5. | Biobran MGN-3 (0.25 g/day for 14 days) |

Splenocytes from male Lewis rats (n=24) |

Biobran MGN3-fed rats showed a significantly higher splenocyte proliferative activity against the superantigen TSST-1 compared to control rats and associated with a higher level of IFN- secretion. |

Giese et al. (2008) [61] |

| 6. | EFR (0.5 to 8 g/ml) |

Splenocytes from C57/BL6 mice |

EFR could significantly increase in vitro splenocyte proliferation by 1.33 to 1.74 times (p<0.05) compared to the control. |

Kang et al. (2022) [47] |

| C. Purified T and B cell proliferative activity | ||||

| 7. | Biobran MGN-3 (1, 10, 100, 1000 g/ml) |

Purified T and B cells isolated from Splenocytes of BALB/c mice |

Biobran MGN-3 had minimal in vitro effects on splenic T cell proliferation and only induced B cell proliferation at a very high concentration (1000 g/ml). |

Chae et al. (2004) [49] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Model | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Alleviate allergic signs and symptoms | ||||

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (2 g/l drinking water for 1 month) |

TDI-induced asthmatic Balb/c mice |

A 10- to 100-fold decrease in sensitivity compared to control was observed with Biobran MGN-3 treatment under TDI ear provocation test at 0.01-10% concentrations. Biobran MGN-3 also significantly lowered the eosinophil counts in the BALF of asthmatic mice. No effects on IgG and IgE production were found. |

Kambayashi & Endo (2002) [78] |

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (1.5 mg/day p.o. for 14 days) |

PCA-titre in Balb/c mice (n=24) |

Biobran MGN-3-fed mice showed a lower allergic dermal response (20 spots) after PCA induction compared to 40 in the PSP group and 80 among the saline control mice. |

Bae et al. (2004) [77] |

| 3. | RBEP (250 mg/kg BW/day for 4 weeks) |

DNCB-induced contact dermatitis in NC/Nga mice (n=21) |

Significantly lower symptom scores (p<0.05) in the RBEP group compared to the negative control group. Rising IgE concentrations in plasma and splenocytes were observed in the RBEP group but at levels significantly lower (50% less) than those in the negative controls (p<0.05). |

An (2011) [34] |

| B. Reduce histamine release | ||||

| 4. | Biobran MGN-3 (2 g/l drinking water for 1 month) |

TDI-induced asthmatic Balb/c mice |

Significantly lower (p<0.05) plasma histamine concentrations were detected in all Biobran MGN-3 treated mice compared to the control. |

Kambayashi & Endo (2002) [78] |

| 5. | Biobran MGN-3 (1.5 mg/day p.o. for 14 days) |

PCA-titre in Balb/c mice (n=24) |

The plasma histamine content in the Biobran MGN-3-fed mice was also 25% lower than in control and PSP (6.5% lower) groups. |

Bae et al. (2004) [77] |

| 6. | Fermented SuperC3GHi bran (100 and 250 g/ml) |

RBL-2H3 mast cell line |

Analysis of in vitro histamine secretion showed a statistically significant 18% reduction (p<0.05) recorded in stimulated mast cells treated with 100 µg/ml fermented SuperC3GHi bran and 43% with 250 g/ml. |

Kim et al. (2011) [79] |

| C. Inhibit mast cell degranulation | ||||

| 7. | Biobran MGN-3 (200, 500, 1000, 3000 g/ml) |

Bone marrow-derived mast cells from BALB/c mice |

Pretreatment with Biobran MGN-3 for 30 minutes resulted in significant inhibition (p<0.01) of -hexosaminidase release after antigen stimulation in a dose-dependent manner. Biobran MGN-3 significantly inhibited (p<0.05) the degranulation activities mediated by SNARE proteins. |

Hoshino et al. (2010) [80] |

| 8. | Fermented SuperC3GHi bran (100 and 250 g/ml) | RBL-2H3 mast cell line |

Treatment with fermented SuperC3GHi bran significantly reduced (p<0.05) the release of -hexosaminidase in antigen-stimulated mast cells by 25% (100 g/ml) and 40% (250 g/ml) compared to the controls. |

Kim et al. (2011) [79] |

| D. Regulate proinflammatory cytokine production | ||||

| 9. | Biobran MGN-3 (200, 500, 1000, 3000 g/ml) |

Bone marrow-derived mast cells from BALB/c mice |

Biobran MGN-3 suppressed the proinflammatory cytokines (TNF- and IL-4) syntheses potentially through the NF-B and MAP kinase (ERK & JNK) activation pathways. |

Hoshino et al. (2010) [80] |

| 10. | RBEP (250 mg/kg BW/day for 4 weeks) |

DNCB-induced contact dermatitis in NC/Nga mice (n=21) |

RBEP significantly lowered IL-4 and IL-10 in both plasma and splenocytes compared to the negative controls (p<0.05). The splenocyte IFN- and IFN–/IL-4 ratio of the RBEP group remained normal, whereas the negative control group registered significantly lower (p<0.05) levels of IFN– and IFN–/IL-4 ratio. |

An (2011) [34] |

| E. Inhibit mast cell degranulation | ||||

| 11. | Fermented SuperC3GHi bran (100 and 250 g/ml) |

AA-induced ear-oedema in ICR mice |

The inflammatory rates (% increase in ear thickness) were 23.5% (control), 14.6% (SuperC3GHi), and 8.5% (indomethacin). SuperC3GHi bran reduced inflammatory response by 35.6% compared to controls, less effective than the 68.5% of indomethacin, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. |

Kim et al. (2011) [79] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Participants | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (1 or 3 g/day for 60 days) |

Healthy adults (n=20, 10 in each group) |

The study found significant effects (p<0.05) over time (baseline, 1 week, 30 days, and 60 days) for IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1, IL-1, IFN-, TNF-, MCP-1, VEGF, EGF. IFN-, TNF-, IL-1, IL-1, IL-8, and IL-10, and EGF peaked at 30 days and returned to the baseline level at 60 days. |

Ali et al. (2012) [63] |

| 2. | RBEP (3g/day or placebo for 8 weeks) |

Healthy adults (n=80, 40 in each group) |

RBEP significantly increased serum IFN- compared to placebo at week 8 (35.56±17.66 vs 27.04±12.51 pg/ml, p<0.05), whereas no significant differences were detected for other cytokines (TNF-, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-12). |

Choi et al. (2004) [25] |

| No | RBAC (dose) | Participants | Key Findings | Author (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 mg/day for 2 weeks with cross-over) |

Older adults (age 75-90, n=36) |

The mean total symptom score for CCS during the control period (0.1535±0.38591) was significantly higher than that of the Biobran MGN-3 treatment period (0.0491±0.09083, p=0.0426). Biobran MGN-3 significantly prevented decrease in T lymphocyte blastogenesis based on PHA mitogen test compared to control. |

Tazawa et al. (2003) [65] |

| 2. | Biobran MGN-3 (250 mg/day for 3 months) |

Older adults (age ≥56, n=60, 30 in each group) |

Biobran MGN-3 significantly improved the QoL of older adults compared to baseline. Compared to placebo, Biobran MGN-3 significantly improved both the physical (p<0.037) and mental (p<0.012) component summary scores and the specific component scores of role physical (p<0.002), bodily pain (p<0.006), vitality (p<0.000), and social functioning (p<0.001). |

Elsaid et al. (2020) [97] |

| 3. | Biobran MGN-3 (500 mg/day for 3 months) |

Older adults (age ≥56, n=80, 40 in each group) |

Biobran MGN-3 group had significantly lower ILI incidents compared to the placebo group (5% vs 22.5%, p=0.048). The risk of ILI infection in the Biobran MGN-3 group was estimated to be 18.2% (95% CI: 3.9-48.9), which was significantly lower (p<0.05) than the 55.1% (95% CI: 43.4-66.3) for the placebo group. |

Elsaid et al. (2021) [68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).