Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

06 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Contribution

2. Literature Review

2.1. Idiosyncratic Volatility

2.1.1. The relation between Idiosyncratic Volatility and Expected Return

2.2. Machine Learning related Literature Review

2.2.1. Supervised Learning and Regression

2.2.2. Feature Selection

- Selection Based on Variance: considers the variance of the different values in each data column (possible feature to be selected) and removes the ones that have a variance less than a certain threshold. VarianceThreshold is one such feature selector in sklearn library.

- Selection Based on Univariate Statistical Tests: considers certain univariate statistical tests as a means of selection and once the tests score the features, selects the highest scoring features using a certain algorithm. Among the feature selectors of this category, SelectPercentile chooses the top p percent of the high scoring features, SelectKBest chooses the k highest scoring ones, SelectFpr selects based on false positive rate test, SelectFdr selects based on false discovery rate test, and SelectFwe selects based on family-wise error rate test. Each of these feature selectors will need a scoring function that can assign importance values to each feature. We will discuss some such scoring functions in the next paragraph.

- Selection Based on Preference of A Regressor/Classifier: considers a regressor or a classifier and tests the importance of the features with training two models one with the feature and the other without it. If the model figures that the existence of the feature does not make much of difference in the model accuracy, the feature will be excluded. SelectFromModel is one such feature selector in sklearn library.

- Sequential Feature Selection: considers a recursive approach in which the model iteratively adds one feature to the selected features set. This is done until the selected features set reaches a desired size. SequentialFeatureSelector is one such feature selector in sklearn library.

2.2.3. Decision Tree based Regression

- DecisionTreeRegressor is a supervised learning method used for regression. The model learns simple decision rules inferred from the features extracted from the training data to predict the target.

- ExtraTreeRegressor uses randomization ideas to find the best split points in the continuous range of target values (as opposed to using a loss function to determine the points). It draws random splits for the node to be added to the tree and chooses the best performing split to be the next chosen range split point.

- GradientBoostingRegressor creates an additive model and adds the regression tree nodes to the tree one at a time.

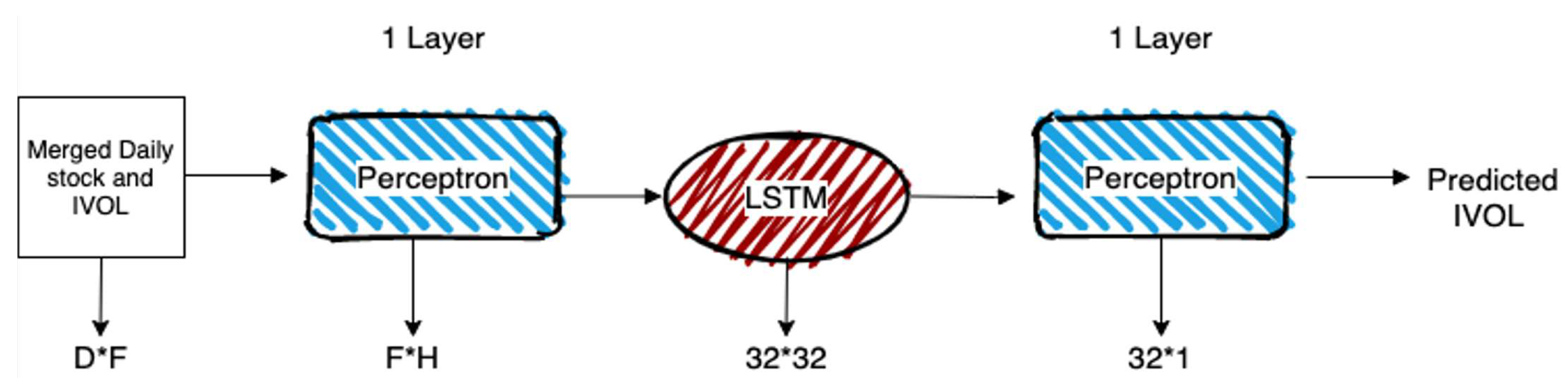

2.2.4. Deep Learning (Neural Network) Components

- Linear Layer: a layer which receives an input one dimensional vector and maps it to another one-dimensional vector using an affine transformation ( where W and B will contain learnable neural network parameters).

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM; Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997; Lindemann et al. 2021): a neural network component designed to extract time-dependant information from the times series data. Internally, it has multiple memory gates and for each input, in addition to the conventional output that the recurrent neural networks emit, it also provides a context output which can be fed back to it to remind it of what information the previous inputs had. This context output is the reason that LSTMs are categorized under the recurrent neural network modules category.

- Loss Function: a mathematical function which is used to calculate the amount of error in a neural network prediction in comparison to the expected actual output. There are many such functions available to be used to train neural networks but we only use the Mean Squared Error function unless otherwise stated.

- Optimizer: an object in charge of updating the neural network parameters based on the calculated loss values by the loss function. Many off-the-shelf optimizers are available, some of which like SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent; Amari 1993) simply multiply the learning rate to the value of error (gradient) and add this value to each parameter (), while the others consider a separate learning rate for each neural network parameter i. Such methods are called adaptive learning rate optimzers and RMSProp (Graves 2013) and AdaDelta (Zeiler 2012) are from such optimizers.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. CRSP-dIVOL a Dataset with Pre-calculated Idiosyncratic Volatility Values

3.1.1. N100IVOL a subset of CRSP-dIVOL

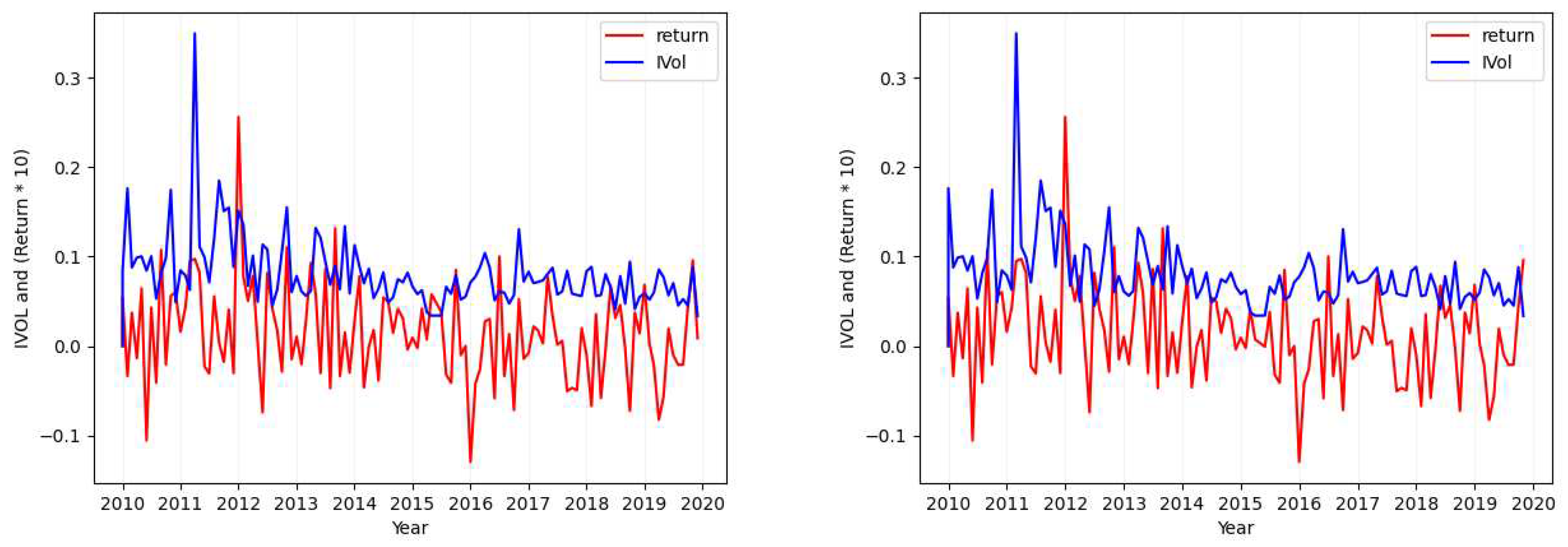

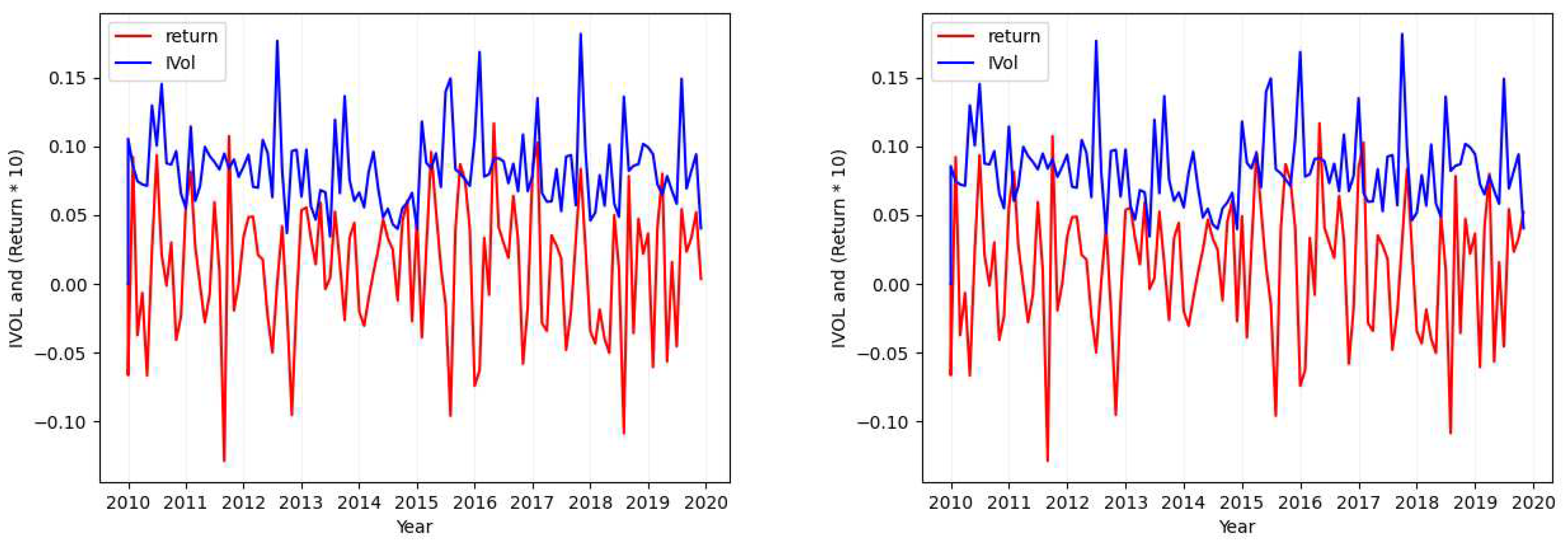

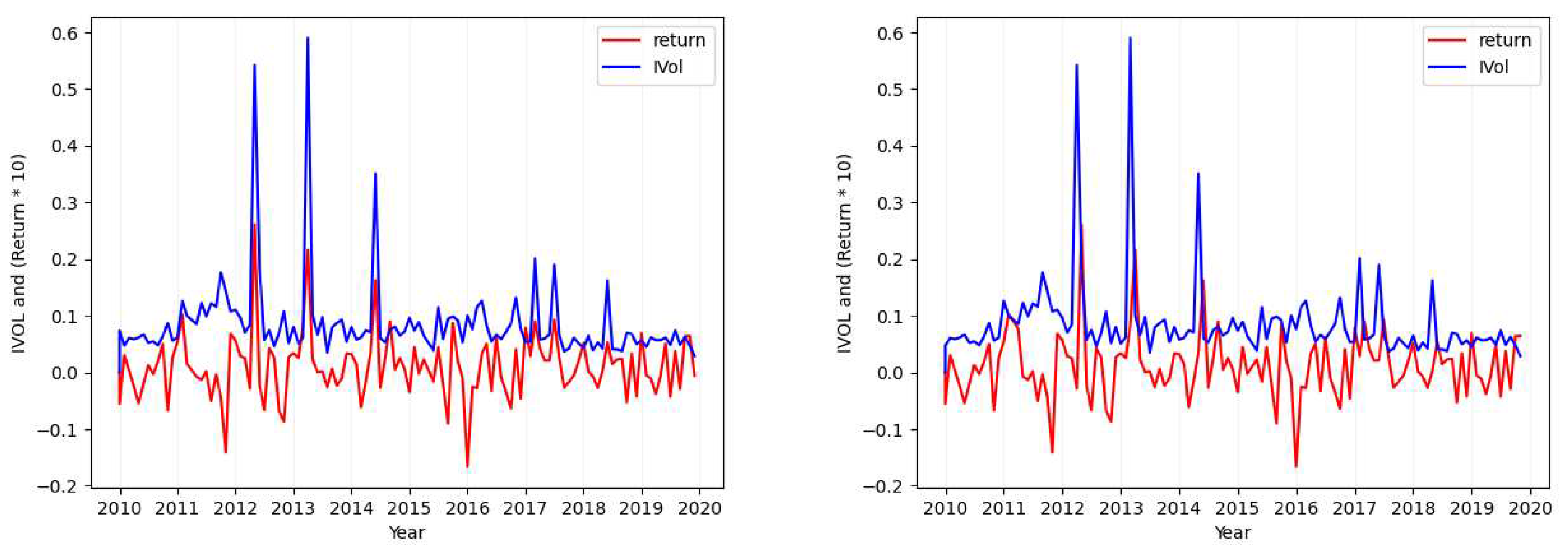

3.1.2. Idiosyncratic Volatility Data Visualization

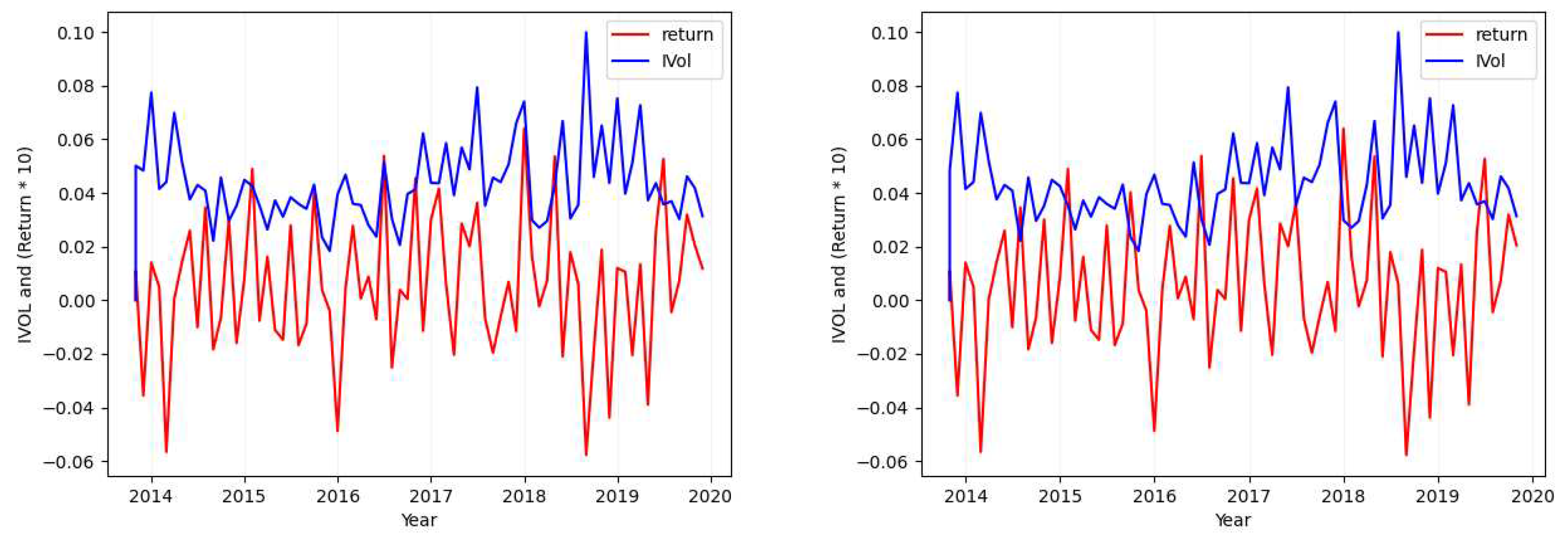

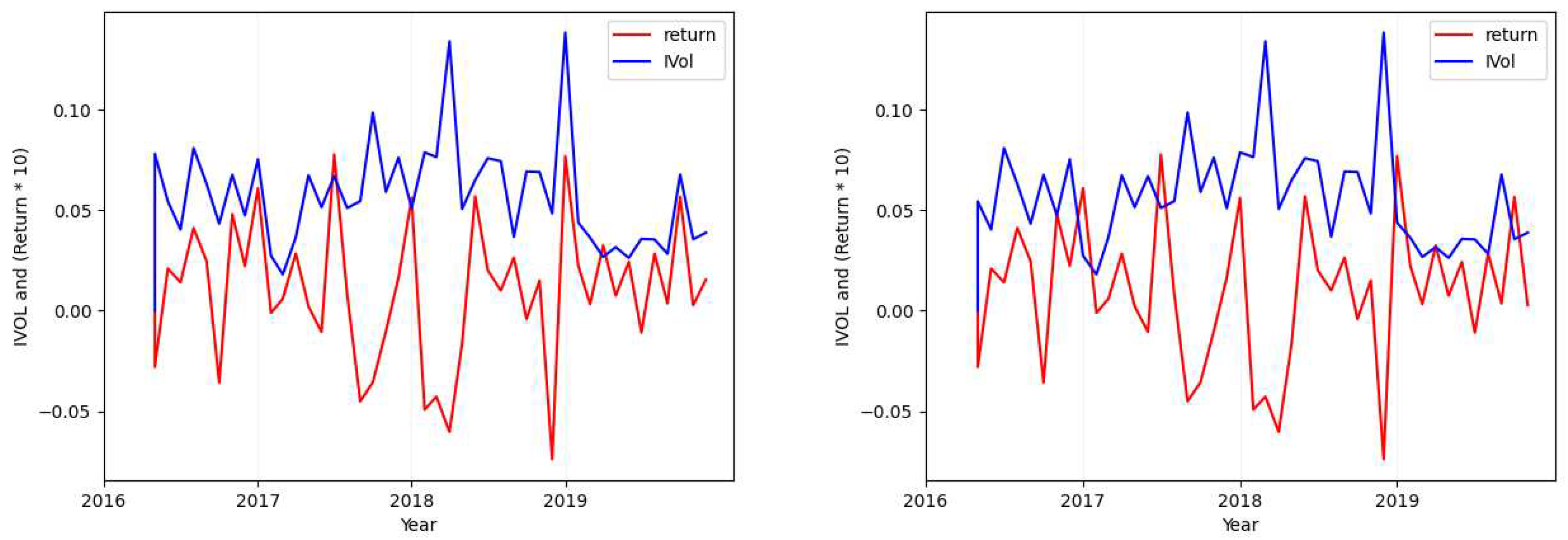

- Case 1

- Considering the tickers MSFT (Figure 1), SIRI (Figure A1), OKTA (Figure A2), and GOOG (Figure A3), we find that the absolute value of the calculated standard deviation for the idiosyncratic volatility and the absolute value of the calculated standard deviation for the return are similar and close (with a maximum of difference).

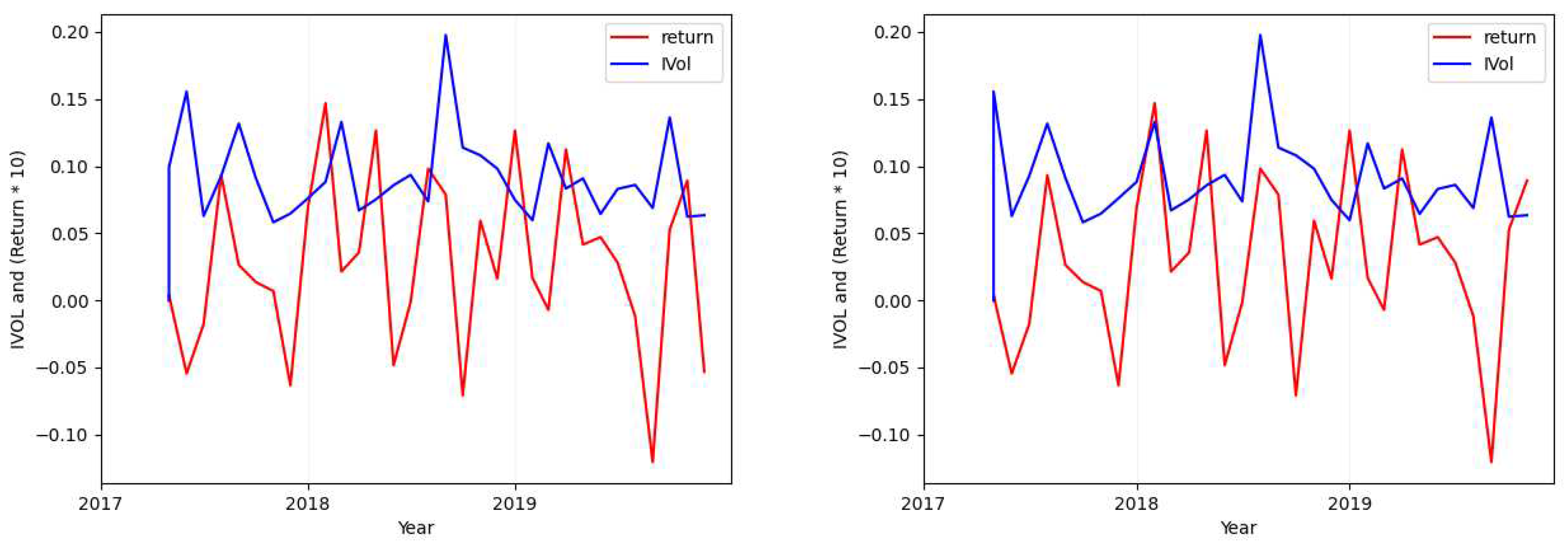

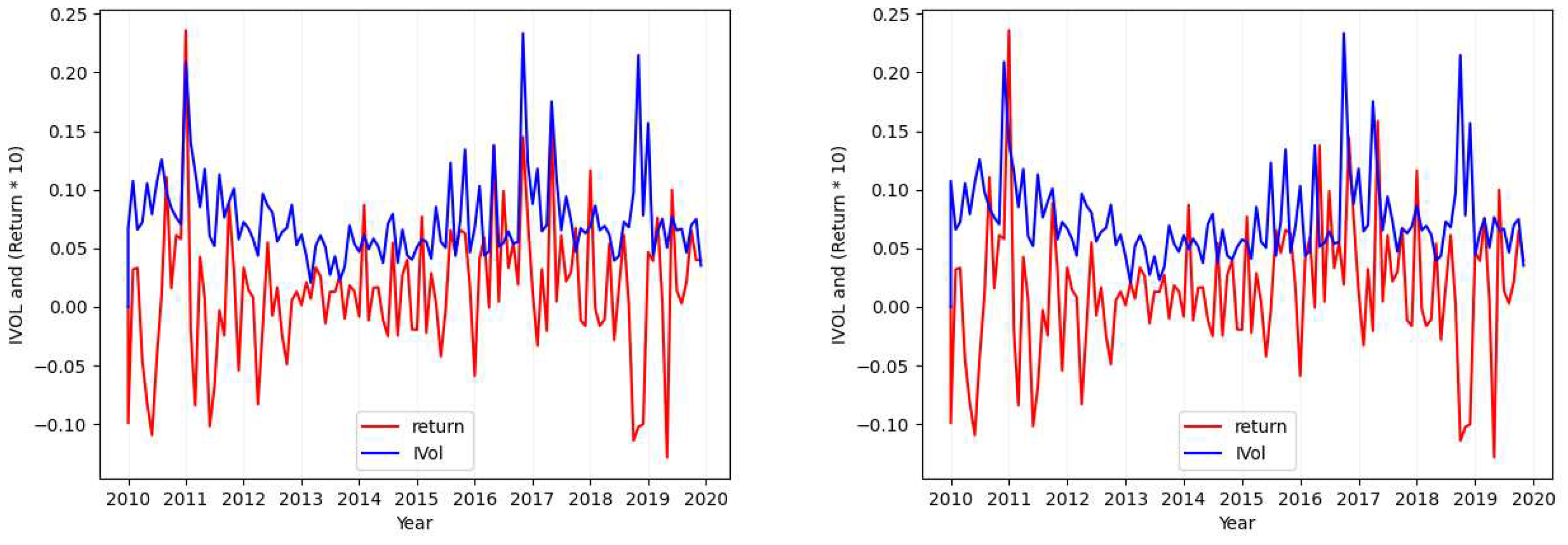

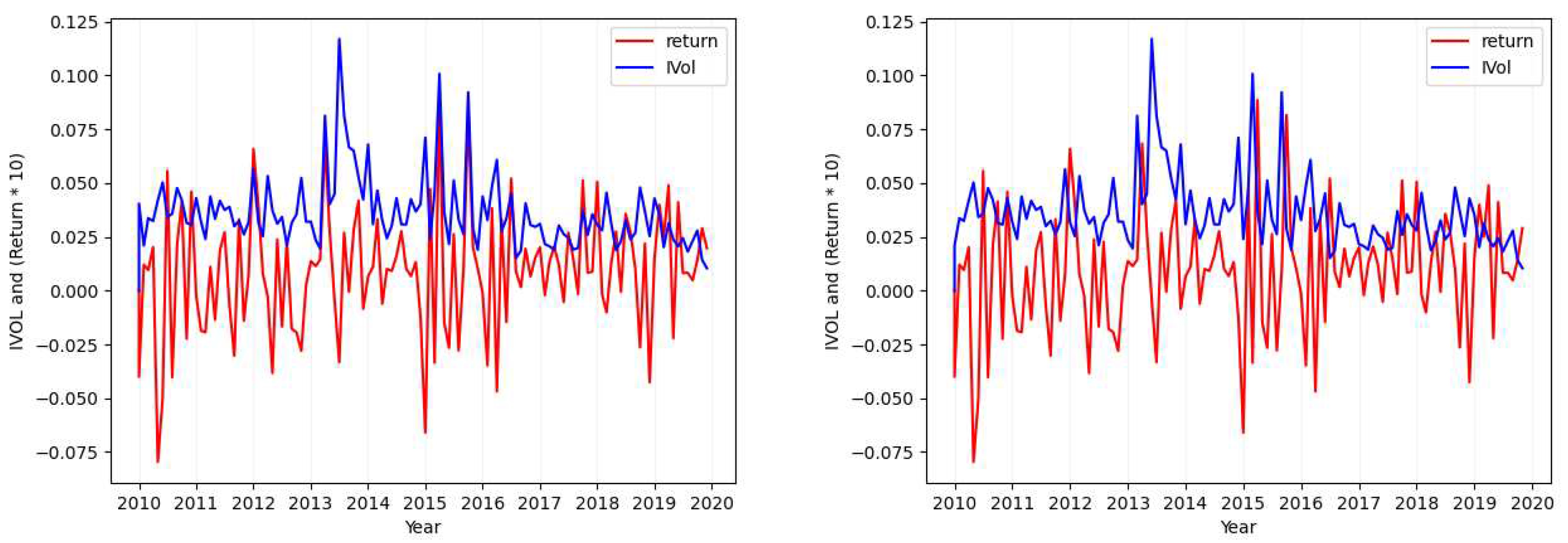

- Case 2

- Considering the tickers ALGN (Figure 2), NFLX (Figure A7), REGN (Figure A4), CHTR (Figure A5), and NVDA (Figure A6), we find that the calculated standard deviation for each of these tickers differs largely (one is approximately double the absolute value of the other) when calculating the metric over the idiosyncratic volatility values in comparison to its calculation over returns.

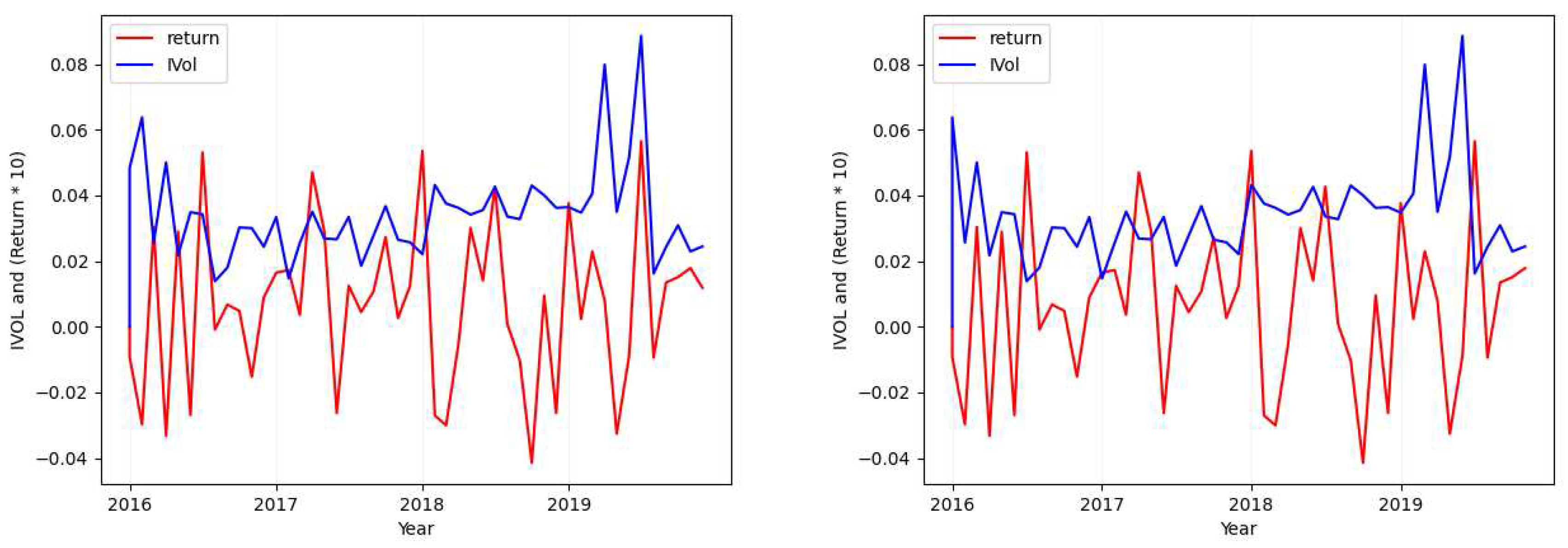

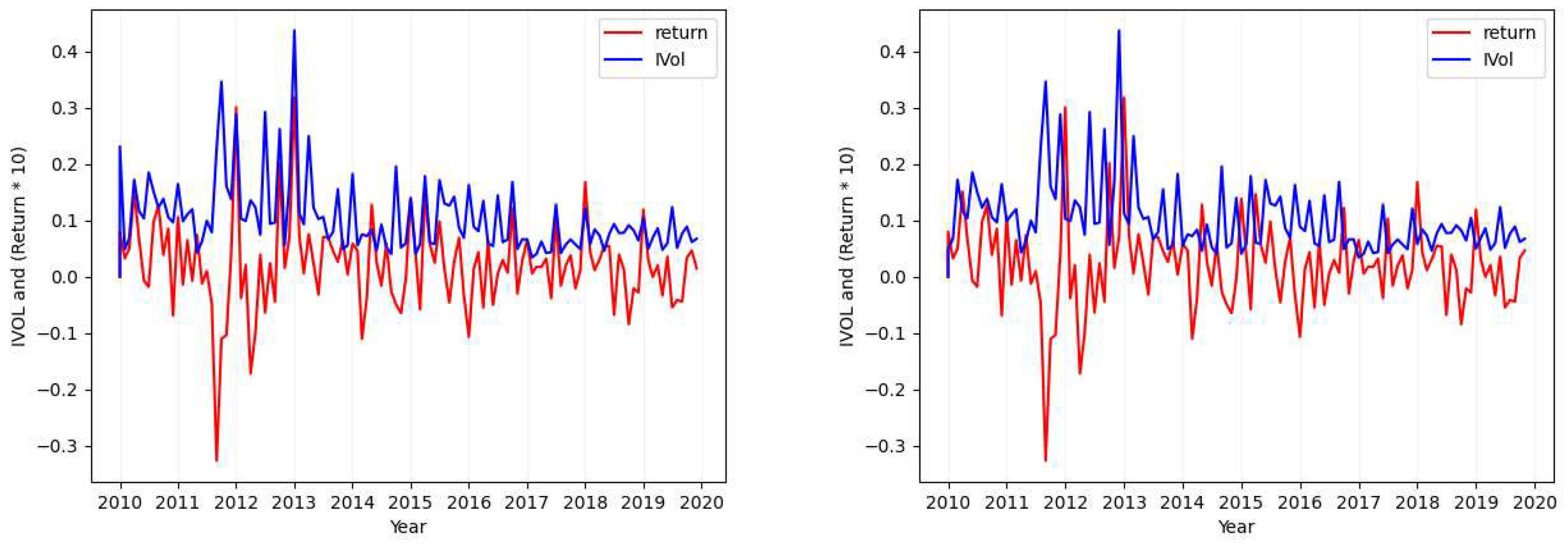

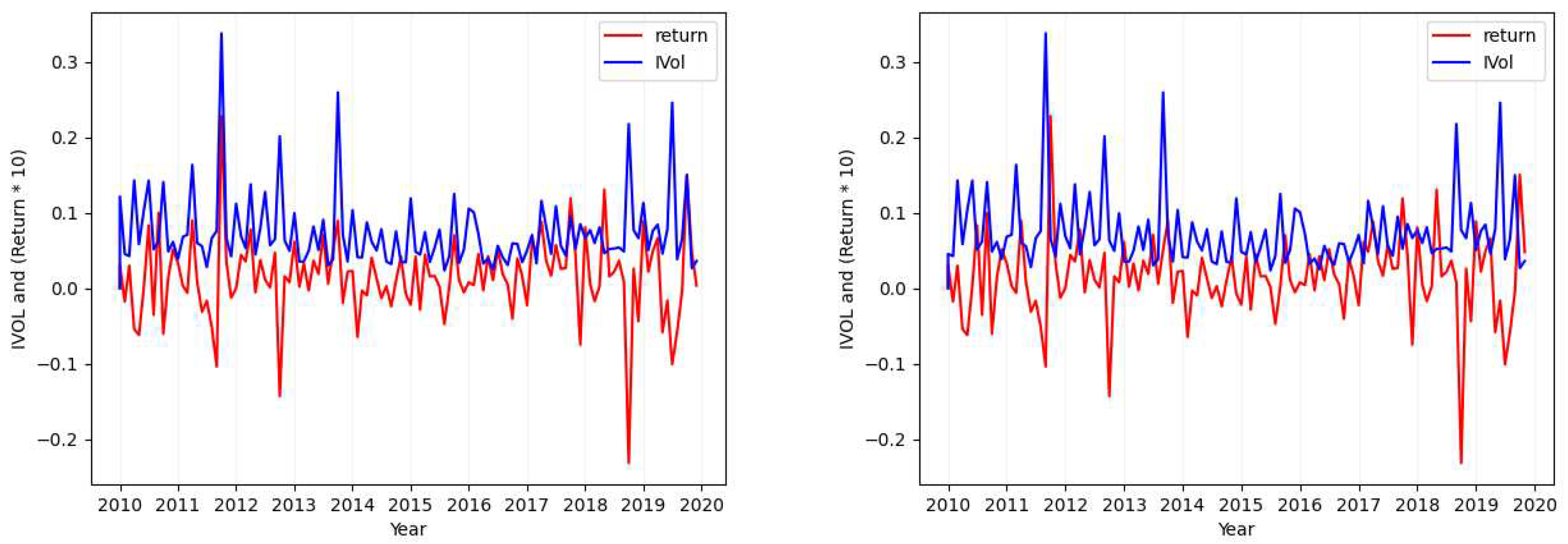

- Case 3

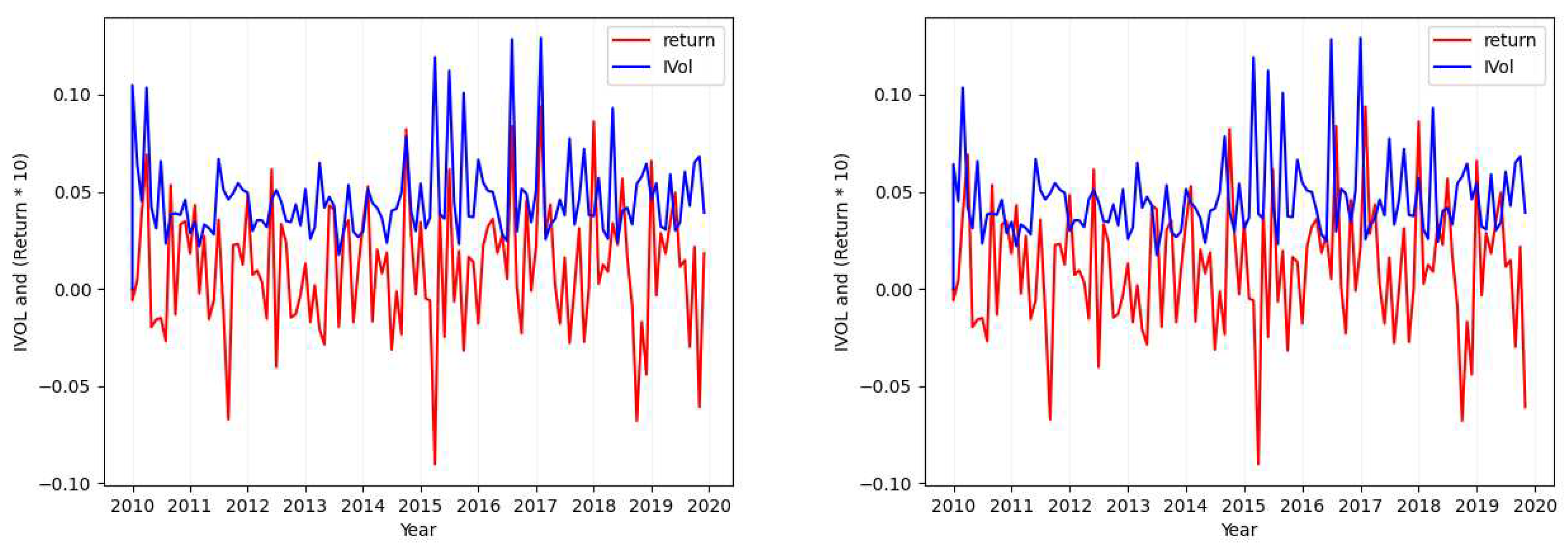

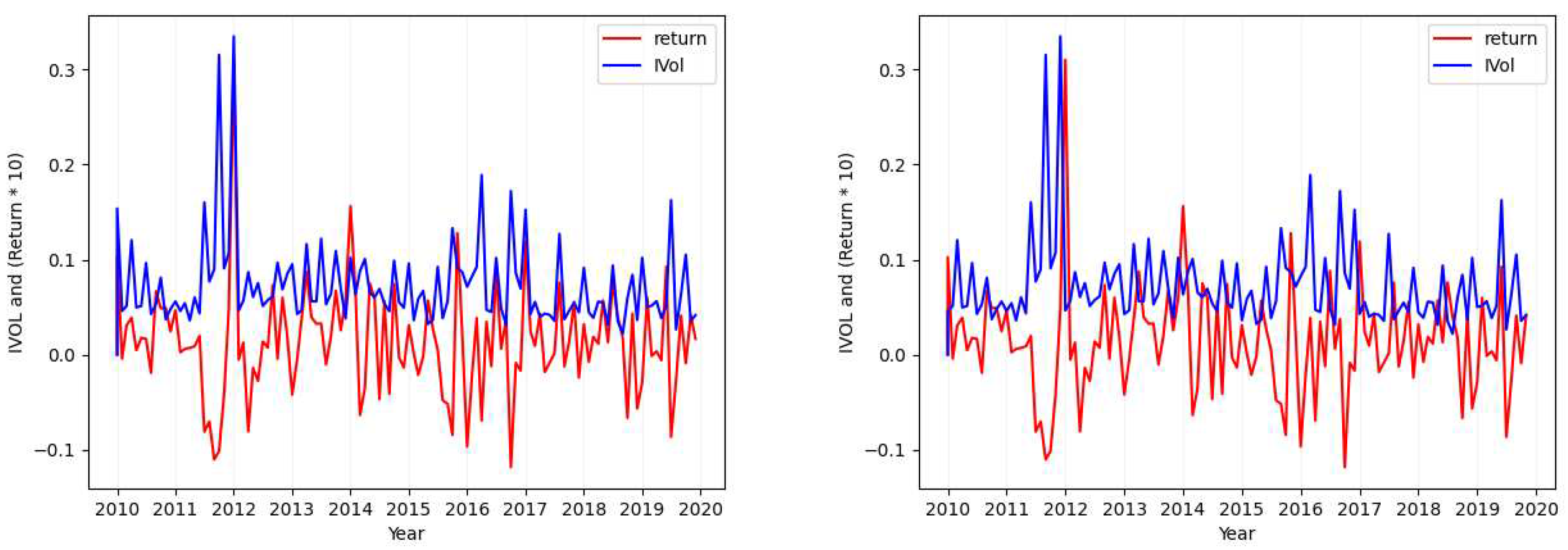

- Case 4

3.1.3. Systematic Risk and Volatility

3.2. Idiosyncratic Volatility Prediction

3.2.1. LSTM based Regression

3.2.2. Model Performance Evaluation

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Feature Selection

4.2. Evaluating the LSTM based Regressor on daily data

4.2.1. Experimental Setup

- Setup 1

- We would consider all the available data from 1969 to 2018 as the training data (the default setup).

- Setup 2

- We would consider all the trade records from 2016 to 2018 as the training data (a period of 36 months of history will be considered as all the available history and the older trade records will be discarded).

- Setup 3

- We would consider all the trade records from 2017 to 2018 as the training data (same as above).

- Setup 4

- We would consider all the trade records only from year 2018 as the training data (same as above).

4.2.2. Results and Analysis

4.3. Evaluating the LSTM based Regressor on monthly data

4.3.1. Results and Analysis

4.4. Further Experiments and Results on Year 2022

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Extra Idiosyncratic Volatility Data Visualization Graphs

References

- Amari, Shun-ichi. 1993. Backpropagation and stochastic gradient descent method. Neurocomputing 5(4-5), 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Ang, Andrew, Robert J Hodrick, Yuhang Xing, and Xiaoyan Zhang. 2006. The cross-section of volatility and expected returns. The Journal of Finance 61(1), 259–299. [CrossRef]

- Ang, Andrew, Robert J Hodrick, Yuhang Xing, and Xiaoyan Zhang. 2009. High idiosyncratic volatility and low returns: International and further us evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 91(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- De Bondt, Werner FM and Richard Thaler. 1985. Does the stock market overreact? The Journal of finance 40(3), 793–805.

- Eiling, Esther. 2013. Industry-specific human capital, idiosyncratic risk, and the cross-section of expected stock returns. The Journal of Finance 68(1), 43–84. [CrossRef]

- Eugene, Fama and Kenneth French. 1992. The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance 47(2), 427–465.

- Eugene, Fama, R French Kenneth, et al. 1996. Multifactor explanations of asset pricing anomalies. Journal of Finance 51(1), 55–84.

- Fama, Eugene F and Kenneth R French. 1993. Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of financial economics 33(1), 3–56. [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F. and James D. MacBeth. 1973. Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy 81(3), 607–636. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Fangjian. 2009. Idiosyncratic risk and the cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of financial Economics 91(1), 24–37. [CrossRef]

- Ghoddusi, Hamed, Germán G Creamer, and Nima Rafizadeh. 2019. Machine learning in energy economics and finance: A review. Energy Economics 81, 709–727. [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, Raul, Gautam Vora, et al. 2015. Reassessing export diversification strategies: a cross-country comparison. Modern Economy 6(01), 96. [CrossRef]

- Graves, Alex. 2013. Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.0850.

- Gu, Shihao, Bryan Kelly, and Dacheng Xiu. 2020, 02. Empirical Asset Pricing via Machine Learning. The Review of Financial Studies 33(5), 2223–2273. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Hui and Robert Savickas. 2006. Idiosyncratic volatility, stock market volatility, and expected stock returns. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 24(1), 43–56.

- Hao, Jiangang and Tin Kam Ho. 2019. Machine learning made easy: A review of scikit-learn package in python programming language. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics 44(3), 348–361. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S. and J. Schmidhuber. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 9, 1735–1780.

- Jegadeesh, Narasimhan and Sheridan Titman. 1993. Returns to buying winners and selling losers: Implications for stock market efficiency. The Journal of finance 48(1), 65–91.

- Leippold, Markus, Qian Wang, and Wenyu Zhou. 2022. Machine learning in the chinese stock market. Journal of Financial Economics 145(2), 64–82. [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Benjamin, Timo Müller, Hannes Vietz, Nasser Jazdi, and Michael Weyrich. 2021. A survey on long short-term memory networks for time series prediction. Procedia CIRP 99, 650–655. [CrossRef]

- Lintner, John. 1969. The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets: A reply. The review of economics and statistics, 222–224. [CrossRef]

- Loh, Wei-Yin. 2014. Fifty years of classification and regression trees. International Statistical Review 82(3), 329–348. [CrossRef]

- Mangram, Myles E. 2013. A simplified perspective of the markowitz portfolio theory. Global journal of business research 7(1), 59–70.

- Markowitz, Harry M. 1952. Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance 7(1), 77–91.

- Merton, Robert C et al. 1987. A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information.

- Nartea, Gilbert V, Bert D Ward, and Lee J Yao. 2011. Idiosyncratic volatility and cross-sectional stock returns in southeast asian stock markets. Accounting & Finance 51(4), 1031–1054. [CrossRef]

- Pilnenskiy, Nikita and Ivan Smetannikov. 2020. Feature selection algorithms as one of the python data analytical tools. Future Internet 12(3), 54. [CrossRef]

- Rasekhschaffe, Keywan Christian and Robert C Jones. 2019. Machine learning for stock selection. Financial Analysts Journal 75(3), 70–88. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Alberto G. 2018. Predicting stock market returns with machine learning. Georgetown University.

- Sharpe, William F. 1964. Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The journal of finance 19(3), 425–442.

- Shi, Yanlin, Wai-Man Liu, and Kin-Yip Ho. 2016. Public news arrival and the idiosyncratic volatility puzzle. Journal of Empirical Finance 37, 159–172. [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, Matthew I and Xiaotong Wang. 2005. Cross-sectional variation in stock returns: Liquidity and idiosyncratic risk.

- Xu, Yexiao and Burton G Malkiel. 2004. Idiosyncratic risk and security returns. Available at SSRN 255303.

- Zeiler, Matthew D. 2012. Adadelta: an adaptive learning rate method. arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.5701.

- Zhong, Xiao and David Enke. 2019. Predicting the daily return direction of the stock market using hybrid machine learning algorithms. Financial Innovation 5(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Studies like Eugene et al. (1996) demonstrate that CAPM fails to explain certain patterns in average stock returns, but these anomalies are captured by the three-factor model Fama and French (1993) (explained in Section 2.1). |

| 2 | They follow the trading strategy suggested by Jegadeesh and Titman (1993). |

| 3 | Using international data from January 1980 to December 2003, except for Finland, Greece, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden, which began in the mid-1980s. |

| 4 | The exponential generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model. |

| 5 | Using data from DataStream that covers the period up to November 2007. |

| 6 | Please note that we use each method in combination with different possible regressors and classifiers to test their suitability to our framework. |

| 7 | Downloaded from Wharton Research Data Services (WRDS); https://wrds-web.wharton.upenn.edu/wrds/ds/crsp/stock_a/dsf.cfm?navId=128; last accessed on December 15, 2020. |

| 8 | According to the guidelines provided by WRDS, a unique (CUSIP, PERMNO) pair represents a distinct company. In certain cases, companies undergo significant changes but retain their trading ticker, resulting in a disparity between the number of tickers and companies. |

| 9 |

https://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.french/data_library.html; last accessed on December 15, 2020. |

| 10 | Although the FF-3 dataset covers a wider range of years from 1926 to 2022 (97 years), we focus only on the data from 1963 to 2019, disregarding the remaining years in the created FF-3 yearly data. |

| 11 | These attributes serve as permanent stock identifiers over time. |

| 12 | We exclude 112,601 stock/year-month groups due to having fewer than 16 trading day records. |

| 13 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasdaq-100; last accessed on May 16, 2022. |

| 14 | In the process, we remove the irrelevant, empty and repetitive feature selector results from the different combinations. |

| 15 |

| Data | observations | IVOL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | sd | min | max | ||

| CRSP-dIVOL | 4,024,328† | 0.117 | 0.123 | 0.000 | 16.627 |

| N100IVOL | 501,429 | 0.078 | - | 0.006 | 1.156 |

| CRSP-All | ||

|---|---|---|

| observation | 4,024,328 | 4,024,328 |

| mean | 0.007 | -0.016 |

| std | 0.015 | 0.015 |

| min | -1.277 | -0.208 |

| max | 1.450 | 1.113 |

| 1969-2018 | 2016-2018 | 2017-2018 | 2018 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | ||

| Decision Tree Regressor | Best | 0.000 | DDOG | 0.000 | DDOG | 0.000 | DDOG | 0.000 | DDOG |

| Average | 0.438 | - | 0.510 | - | 0.509 | - | 0.557 | - | |

| Worst | 1.341 | VRSN | 2.354 | VRSN | 2.350 | VRSN | 4.110 | VRSN | |

| Extra Tree Regressor | Best | 0.000 | KDP | 0.000 | DOCU | 0.000 | DOCU | 0.000 | MRNA |

| Average | 0.476 | - | 0.524 | - | 0.550 | - | 0.539 | - | |

| Worst | 1.694 | NVDA | 2.065 | VRSN | 2.350 | VRSN | 4.110 | VRSN | |

| Gr. Boosting Regressor | Best | 0.000 | CRWD | 0.000 | CRWD | 0.000 | CRWD | 0.000 | CRWD |

| Average | 0.503 | 0.524 | - | 0.530 | - | 0.563 | - | ||

| Worst | 2.346 | VRSN | 2.353 | VRSN | 2.351 | VRSN | 4.110 | VRSN | |

| LSTM based Regressor | Best | 0.180 | MRNA | 0.161 | ODFL | 0.182 | ODFL | 0.173 | ANSS |

| Average | 0.302 | - | 0.308 | - | 0.306 | - | 0.297 | - | |

| Worst | 0.521 | ASML | 0.819 | CHTR | 0.586 | PCAR | 0.563 | ASML | |

| 1969-2018 | 2016-2018 | 2017-2018 | 2018 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | ||

| With All Months Prediction | Best | 0.155 | ANSS | 0.168 | CMCSA | 0.161 | ODFL | 0.160 | ODFL |

| Average | 0.283 | - | 0.299 | - | 0.282 | - | 0.286 | - | |

| Worst | 0.935 | WBA | 0.833 | EBAY | 1.465 | PAYX | 0.735 | CPRT | |

| With One Month Prediction | Best | 0.177 | EXC | 0.160 | ANSS | 0.160 | ODFL | 0.160 | ODFL |

| Average | 0.506 | - | 0.287 | - | 0.271 | - | 0.279 | - | |

| Worst | 4.367 | HON | 0.890 | ISRG | 0.726 | COST | 0.957 | XEL | |

| With One Month Lagged Prediction | Best | 0.124 | CMCSA | 0.145 | ODFL | 0.126 | CMCSA | 0.134 | ODFL |

| Average | 0.283 | - | 0.277 | - | 0.270 | - | 0.273 | - | |

| Worst | 1.317 | PEP | 0.580 | AMGN | 0.663 | AMAT | 0.576 | EXC | |

| N100Dataset | observations | IVOL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | min | max | ||

| 1963-2019 | 501,429 | 0.078 | 0.006 | 1.156 |

| 2020-2022 | 3696 | 0.073 | 0.008 | 0.679 |

| 1969-2021 | 2019-2021 | 2020-2021 | 2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | ||

| Decision Tree Regressor | Best | 0.170 | NXPI | 0.178 | MDLZ | 0.118 | EXC | 0.128 | EXC |

| Average | 0.448 | - | 0.488 | - | 0.520 | - | 0.434 | - | |

| Worst | 2.760 | DOCU | 2.767 | DOCU | 2.767 | DOCU | 2.421 | DOCU | |

| Extra Tree Regressor | Best | 0.230 | ADI | 0.193 | PCAR | 0.125 | EXC | 0.120 | EXC |

| Average | 0.579 | - | 0.513 | - | 0.556 | - | 0.424 | - | |

| Worst | 2.980 | CSX | 1.404 | QCOM | 2.706 | DOCU | 2.767 | DOCU | |

| Gr. Boosting Regressor | Best | 0.203 | HON | 0.192 | MU | 0.147 | EXC | 0.121 | EXC |

| Average | 0.494 | 0.489 | - | 0.524 | - | 0.426 | - | ||

| Worst | 2.756 | DOCU | 2.755 | DOCU | 2.767 | DOCU | 2.556 | DOCU | |

| LSTM based Regressor | Best | 0.120 | NVDA | 0.215 | SWKS | 0.122 | NVDA | 0.121 | NVDA |

| Average | 0.270 | - | 0.310 | - | 0.269 | - | 0.260 | - | |

| Worst | 1.324 | ATVI | 0.578 | AMD | 0.846 | ATVI | 0.529 | ATVI | |

| 1969-2021 | 2019-2021 | 2020-2021 | 2021 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | IVError | Ticker | ||

| With All Months Prediction | Best | 0.122 | NVDA | 0.120 | NVDA | 0.130 | NVDA | 0.137 | EXC |

| Average | 0.480 | - | 0.354 | - | 0.401 | - | 0.385 | - | |

| Worst | 2.050 | ANSS | 1.375 | VRSK | 2.558 | ROST | 1.673 | LRCX | |

| With One Month Prediction | Best | 0.211 | PEP | 0.215 | NVDA | 0.215 | NVDA | 0.215 | NVDA |

| Average | 0.292 | - | 0.322 | - | 0.311 | - | 0.309 | - | |

| Worst | 0.522 | GOOG | 0.929 | CTAS | 0.626 | XEL | 0.593 | AZN | |

| With One Month Lagged Prediction | Best | 0.207 | NVDA | 0.107 | NVDA | 0.210 | NVDA | 0.171 | CRWD |

| Average | 0.324 | - | 0.396 | - | 0.333 | - | 0.643 | - | |

| Worst | 1.602 | CDNS | 3.978 | XEL | 1.258 | PEP | 2.649 | ADP | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).