1. Introduction

In past years recreational diving has attracted more and more interest

1 and among such divers most likely an increasing number of diabetic divers (as reflected in the research cited throughout this article [

1]). At the same time technological advances such as increased use of continuous blood glucose monitoring (CGM) not only improve therapy but also could increase safety of diabetics and people around them [

2].

Examples of studies

validating CGM before and after dive, Bonomo et al. [

3] indicated during „Deep Monitoring Programme“ that Medtronic CGM delivered plausible values during diving; similarly Lormeau et al. [

4] indicated that Fresstyle Libre may run properly also under pressure/after recompression. Similarly, Adolfsson et al. [

5] tested Medtronic CGM on 117 dives. As early as 2004 Dear et al. [

6] surveyed plasma glucose of 555 dives. Pollock et al. [

7] monitored plasma glucose of teenage divers before and after dives.

Studies

testing CGM sensors in compression chambers comprise inter alia Adolfsson et al. [

8] who tested 48 enlite sensors in hypo- and hyperbaric conditions up to 4bar additional pressure or Pieri et al [

9] who showed that Dexcom G4 work accurately under hyperbaric conditions, collecting 26 data points. Both studies were conducted in compression chambers.

It can be seen that the use and validation of CGM results is an emerging theme in diving and research. However, there is limited evidence under hyperbaric conditions for individual systems and so far no study was conducted under real life scuba diving conditions. This may also be one reason why diving guidelines (see annex 1 for an overview of guidelines for diving with diabetes) make little reference to the use of CGM to increase diabetic divers‘ safety. This research aims to explore usability of CGM systems during diving and derive implications for diabetic divers.

In continuation of the above, this study aims to add to such data for validation and testing contemporary CGM systems. Further, it aims to provide evidence on the accuracy of CGM systems

during real life scuba use including exposure to both pressure and salt water. In order to do so, four dives were conducted with one subject during which blood glucose values were collected to then be compared against CGM readings and test MARD values [

10] and Clarke Error Grid Distirbution [

11].

2. Experimental design

The experiment was set up to enable blood glucose measurement underwater, i.e. under hyperbaric conditions with up to 2 bar additional pressure. All four dives were conducted in the open sea in Tolo, Greece during August 2022 with the support and under the guidance of the dive center Intro Dive, Tolo.

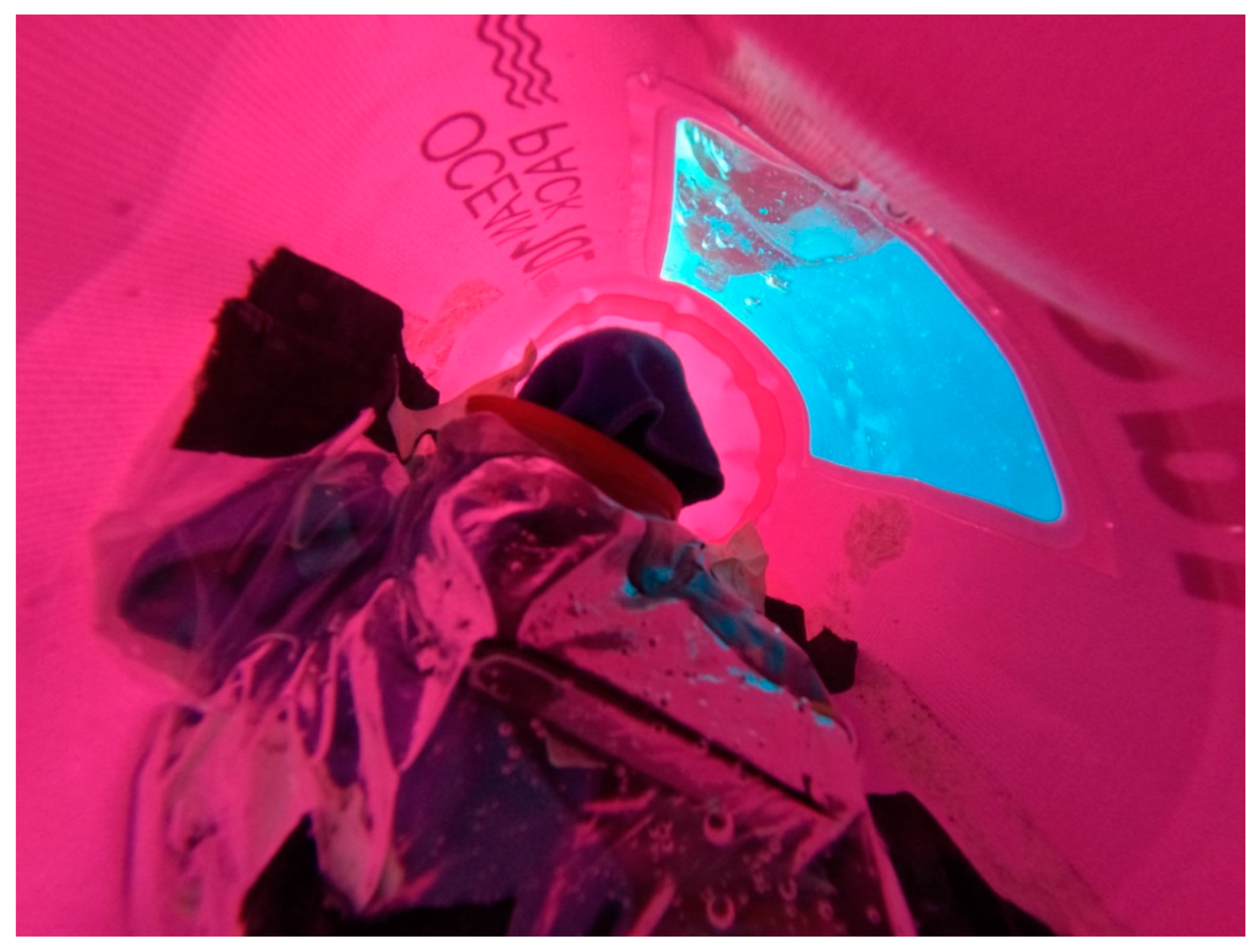

To enable blood glucose measurement underwater, a dry bag was used to create a dry bubble: the dry bag was used upside-down filled with air and pulled down by a weight system to establish neutral buoyancy. Inside the drybag a smaller bag was mounted to carry the blood glucose measurement equipment as well as a towel to dry off subject’s fingers as good as possible. During the dives the subject would bring in its hand from underneath into the air space inside the dry bag. There fingers would be toweled off and blood glucose sample taken. Annex 2 shows pictures of the setup, the equipment, and carrying under water.

The exploratory experiment was conducted with one subject: male, applying pump therapy, with a HbA1C of <=6%, and time in range of >90% in the four quarters preceding the experiment. As the subject conducted the blood glucose measurement under water itself with a familiar device, only some preparatory briefing was provided by diabetologist and the guiding divemaster.

The following equipment was used during the experiment:

The dive profiles were recorded via a Cressi Newton dive computer which recorded measured depth every 20 seconds.

The blood sugar values were collected using mylife Unio Neva

2.

Two CGM systems were tested:

Dexcom G6 sensor inserted fours days before the first dive and calibrations with BG stabilized two days before the first dive. The sensor expired 2 days after the last dive.

Abbott Freestyle Libre 3 sensor inserted 3 days before the first dive and expired 7 days after the last dive.

The CGM sensors were positioned on the abdomen of the subject. They were worn under the wetsuit but without further (environmental) protection/fixation.

In general, every sample would comprise two blood glucose measurements to reduce impact form inaccuracies in the blood glucose values. The sampling procedure was repeated every 5 minutes or longer, corresponding to the frequency of the interstitial glucose recordings via the CGM systems. In total 33 samples were collected, of which 26 under water at various depth/relative pressure, 4 before diving, and 3 after diving. One post dive sample could not be collected as BG reader dropped into the water during exit.

Annex 3 shows the results for each of the dives over time including 2h before and 1h after the dives. Note that none of the BG samples collected was used to calibrate the CGM because otherwise CGM values could have been affected by (re-)adjustment effects.

3. Results

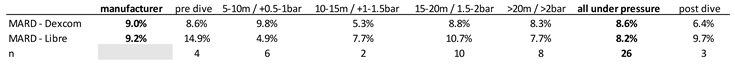

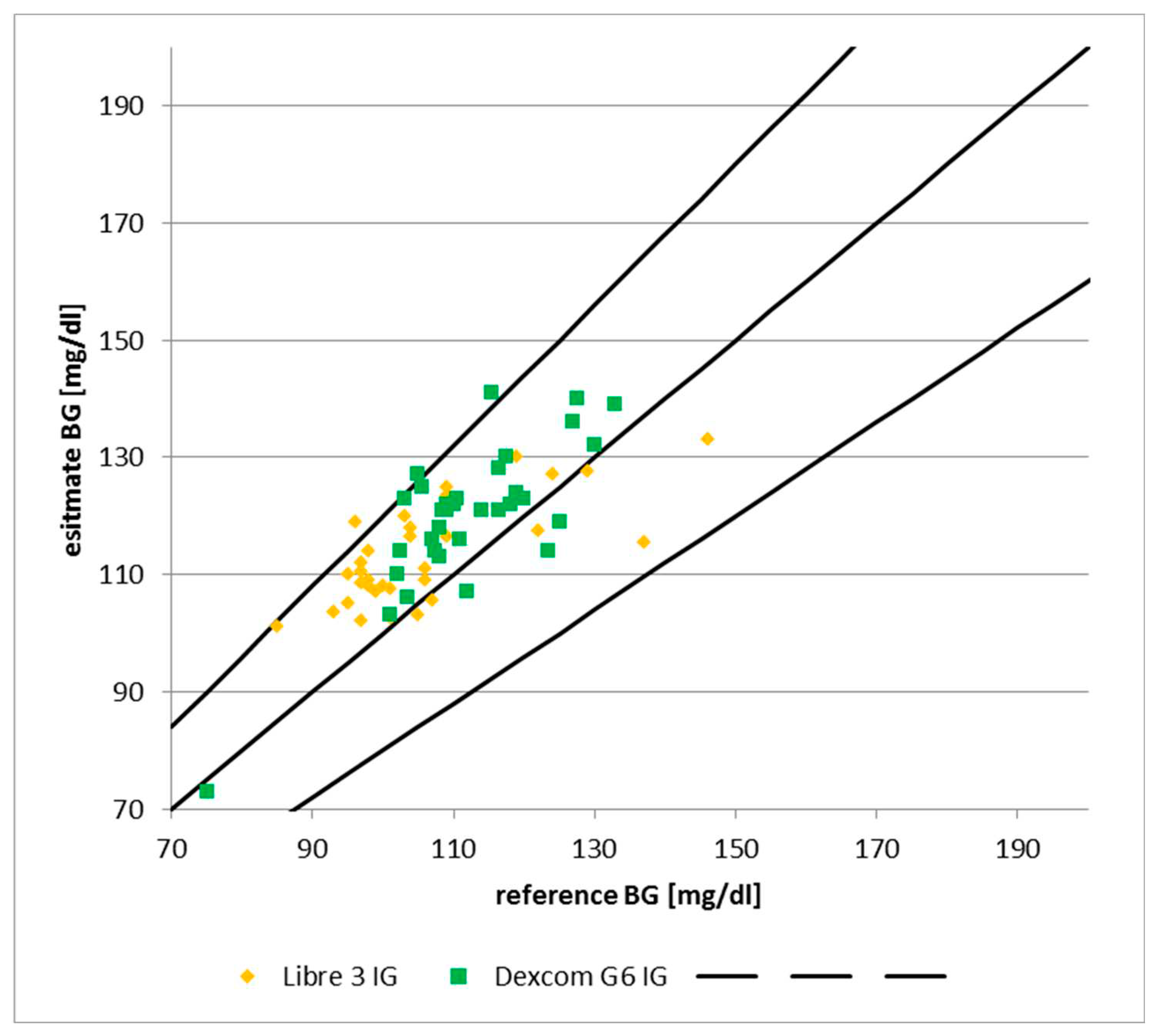

The samples of blood glucose collected during the dive were mapped to the corresponding CGM reading and the absolute relative deviation was calculated to track the accuracy of CGM readings vs. Actual blood glucose. The table below shows the mean absolute relative deviation (MARD) of the samples pre and post dive as well as during the dive (clustered by depth/relative pressure) and compares these against the MARD as quoted by the manufacturer under normal conditions (first column):

Generally two BG samples were taken and the average of the two was used to calculate MARD in order to minimize impact from inaccuracies of BG measurements. Where the dive time realized under water that the value was implausible, e.g. because diluted, a new sample was taken immediately (e.g. „low“ or in the 40ies despite being above 100 shortly before). In one case such resampling took too long and the two samples were used as individual data points as the CGM value updated in the meantime. In three further cases one of the two blood samples was discarded during analysis of the data because they were obviously implausible as they showed both, a larger deviation and also off the trend of neighboring samples.

In the 28 cases where the average of two blood samples was used the median spread around such average was 2.3% (3.7% mean). Even adding this to the observed relative deviations does not indicate undue misreading by CGM under pressure/after decompression.

Further, no correlation between depth and observed deviation between BG and IG could be observed as per exhibit 2 below. However, in order to verify this first impression, increased sample size and regression controlling for other factors like BG level would be required.

Figure 1.

Absolute relative deviation vs. depth. Source: experimental dives.

Figure 1.

Absolute relative deviation vs. depth. Source: experimental dives.

As can be seen from the dive charts in annex 3, no systematic pattern of deviation emerged between blood glucose and tissue glucose. In particular, comparing the blood glucose samples during the dives to those pre/post, it appears the samples were not diluted by seawater.

For Dexcom 25% of samples turned out above the CGM reading leading to the suspicion that if they/some of them were used for calibration, accuracy of results may even have improved. For Libre 42% of samples turned out below the CGM reading, i.e. appears balanced.

All samples were taken while CGM values in range of 70-145 Dexcom / 60-150 Libre and slope was 1mg/dl/min (except for 2 samples at up to 4mg/dl/min Dexcom / 3 samples at up 3mg/dl/min Libre); i.e. minimal distortions expected.

Considering the time lag between CGM readings based tissue glucose and actual blood glucose, one could have expected this effect emerging in the samples shortly after a pressure increase/decrease (i.e. decent/ascent). However, no such pattern emerged as can be seen from the dive logs in annex 3. Similarly, (abrupt) temperature changes may have an effect on tissue glucose and/or CGM readings. Again, no pattern emerged considering temperature decreased a) from air to water (from ca. >30°C to ca. 25°C) and b) in deeper waters (ca. 2°C per 10m).

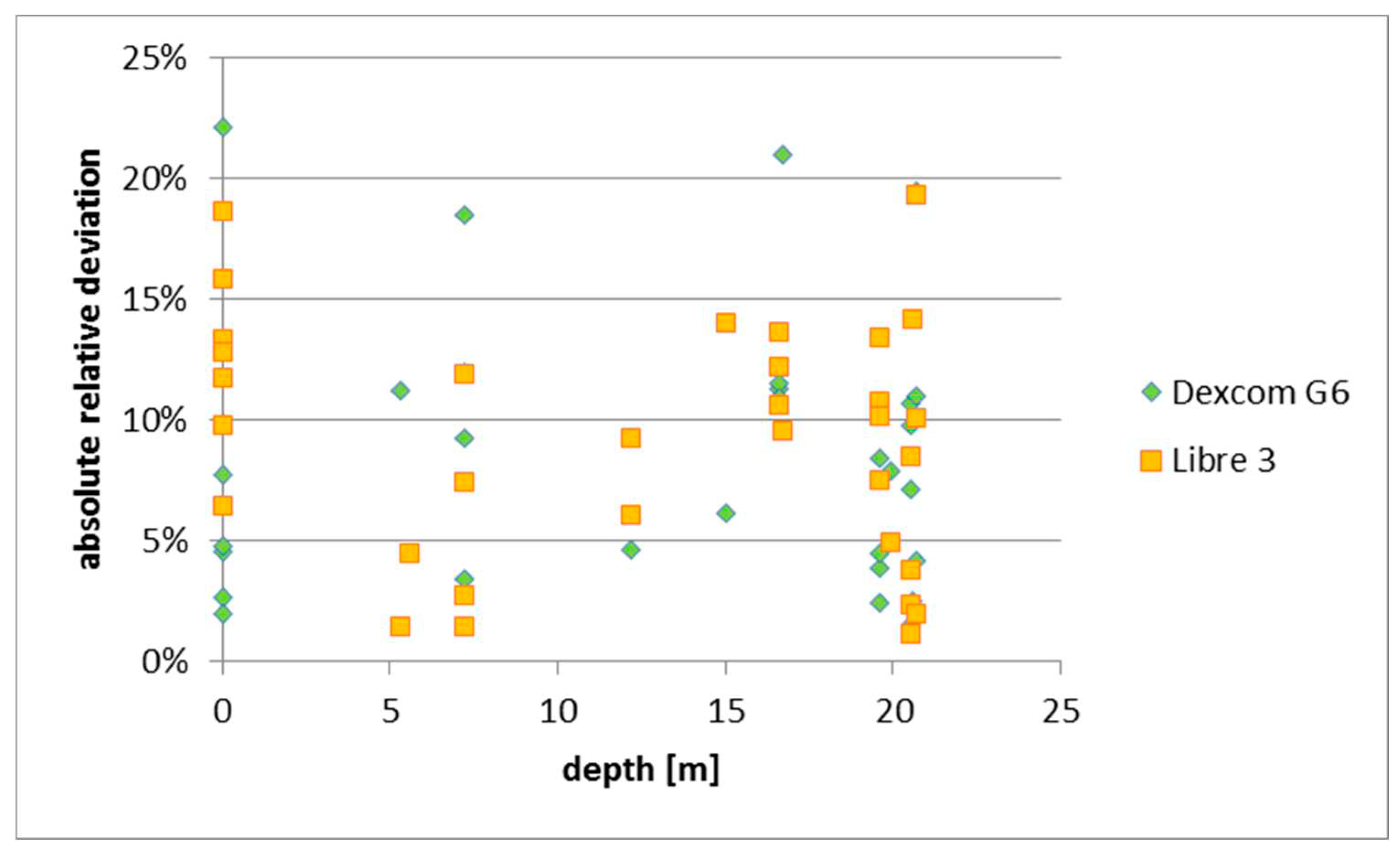

According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO guideline 15197), a maximum acceptable difference within 20% for glucose levels > 75mg/dL and within 15mg/dL for levels < 75mg/dL in at least 95% of the values compared. The chart below shows that this criterion is fulfilled. All but one reading of the Dexcom fall into area „A“ of the Clarke Error Grid. The only outlier is a reading at ca. 17m depth; the subsequent readings at the same depth showed 6-12% deviation. Furthermore, all readings of the Libre 3 fall into area „A“ of the Clarke Error Grid.

Figure 2.

MARD under hyperbaric conditions vs. Manufacturer data. Source: experimental dives, Clarke et al. (1987).

Figure 2.

MARD under hyperbaric conditions vs. Manufacturer data. Source: experimental dives, Clarke et al. (1987).

An obviously critical point is the rather small sample size (33 in total, of which 4 pre-dive, 26 under hyperbaric conditions, 3 post-dive). To note that similar conclusions were reached based on a sample of 26 in a hyperbaric chamber using Dexcom G4 [

9] and 48 enlite sensors up to 4bar additional pressure in a chamber [

8]. Whilst the results cannot be added together because different systems were tested, they are consistent in the sense encouraging diabetic divers to carefully consider of CGM data bearing in mind limitations in manufacturers‘ clearances.

4. Conclusion

For

practitioners the result of this study indicate that Dexcom G6/Libre 3 CGM can be used in planning and monitoring dives in order to increase divers‘ safety. However, further testing and evidence could be collected before issuing a recommendation as currently CGM only cleared by manufacturer for up to e.g. 2.5m for 24h

3 / 1m for 0.5h

4. Once the results could be confirmed it seems advisable to update safety-recommendations to diabetic divers to take account of CGM technology:

Dives can be planned based on a combination of CGM observed trend and own extrapolation based on basic indicators such as active insulin, recent and expected activity level, carbohydrate intake, and typical trends that time of the day [

12]. CGM curve up to beginning of dive offers more insight than insulated blood glucose values (cf. examples in annex 3)

Diabetic divers may consider taking CGM-sensor and –monitor under water to increase safety. In particular, monitoring glucose values enables underwater intake of glucose: Some of the current guidelines recommend carrying carbohydrate supplies under water. However, taking out regulator to supplement sugar when sensing hypoglycemia can be dangerous symptoms include impaired motion control and consciousness. Using a CGM monitor for early monitoring allows to supplement sugar before actual hypoglycemic event, i.e. under full control.

This is particularly viable as the use of electronics during dives appears ot be increasing. This includes phones in protective cases used as camera – the same phone that may have the CGM monitor app installed.

Organizations issuing guidelines for safe diving are encouraged to weigh the benefits of using CGM at least for indicative monitoring against the fact that this exceeds the range of use warranted by manufacturers. The experimental setup developed here appears a cost effective way to collect further evidence and test also other CGM models.

For

academia the experiment achieved milestones in terms of being the first study to a) overlay CGM data with dive profile and b) collect blood glucose values under water (real life situation) to verify CGM values. The results add to the research on the accuracy of CGM systems during dives quoted in the introduction . in particular validations under actual hyperbaric conditions [

8,

9] by indicating for further systems that CGM readings in hyperbaric situations and after decompression not less accurate than under normal use. Notably, the experimental setup allowed testing in real life conditions under water in an efficient manner which can be considered a step beyond compression chamber testing.

In terms of further research there is a strong need to confirm this exploratory research by increasing size of sample and collecting samples under even higher additional pressure (recreational diving up to 40m implies up to 4bar additional pressure; so far only tested in compression chamber [

8]). As a variation to the direct BG testing under water with handheld devices, one may consider collecting blood samples for more accurate laboratory analysis in order to increase precision of the results.

Further analysis could be taken out, such as testing for impact of temperature, use of oxygen enriched air [

13], or activity level e.g. using heart rate monitor to track strain. An increased sample size could further enable regression analysis whether depth or other factors during diving have a (small) impact on CGM accuracy. For additional certainty, one may consider collecting blood samples under water which then are tested for BG a) at normobaric conditions and b) using higher precision devices.

The experimental setup developed to collect blood glucose samples under water proved to be an efficient option for future data collection, be it to confirm results on systems tested to date or to test new CGM systems as they come to market.

Annex 1: Selected Guidelines for Recreational Diving with Diabetes

Annex 2: Underwater Dry Bubble Construction

Picture 1.

dry bag with window used upside-down; second small bag taped to the inside to carry blood glucose measurement equipment and towel. Slates to note down time and value of blood glucose. Not depicted: weight system to neutralize buoyancy of dry bag. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Picture 1.

dry bag with window used upside-down; second small bag taped to the inside to carry blood glucose measurement equipment and towel. Slates to note down time and value of blood glucose. Not depicted: weight system to neutralize buoyancy of dry bag. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Picture 2.

close up of equipment bag underwater from underneath, where subject put in arms; ca. 20cm diameter Anaconda-like. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Picture 2.

close up of equipment bag underwater from underneath, where subject put in arms; ca. 20cm diameter Anaconda-like. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Picture 3.

Picture 3. divers carrying dry bag including weight system. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Picture 3.

Picture 3. divers carrying dry bag including weight system. Source: courtesy of Intro Dive, Tolo.

Annex 3: Dive Logs

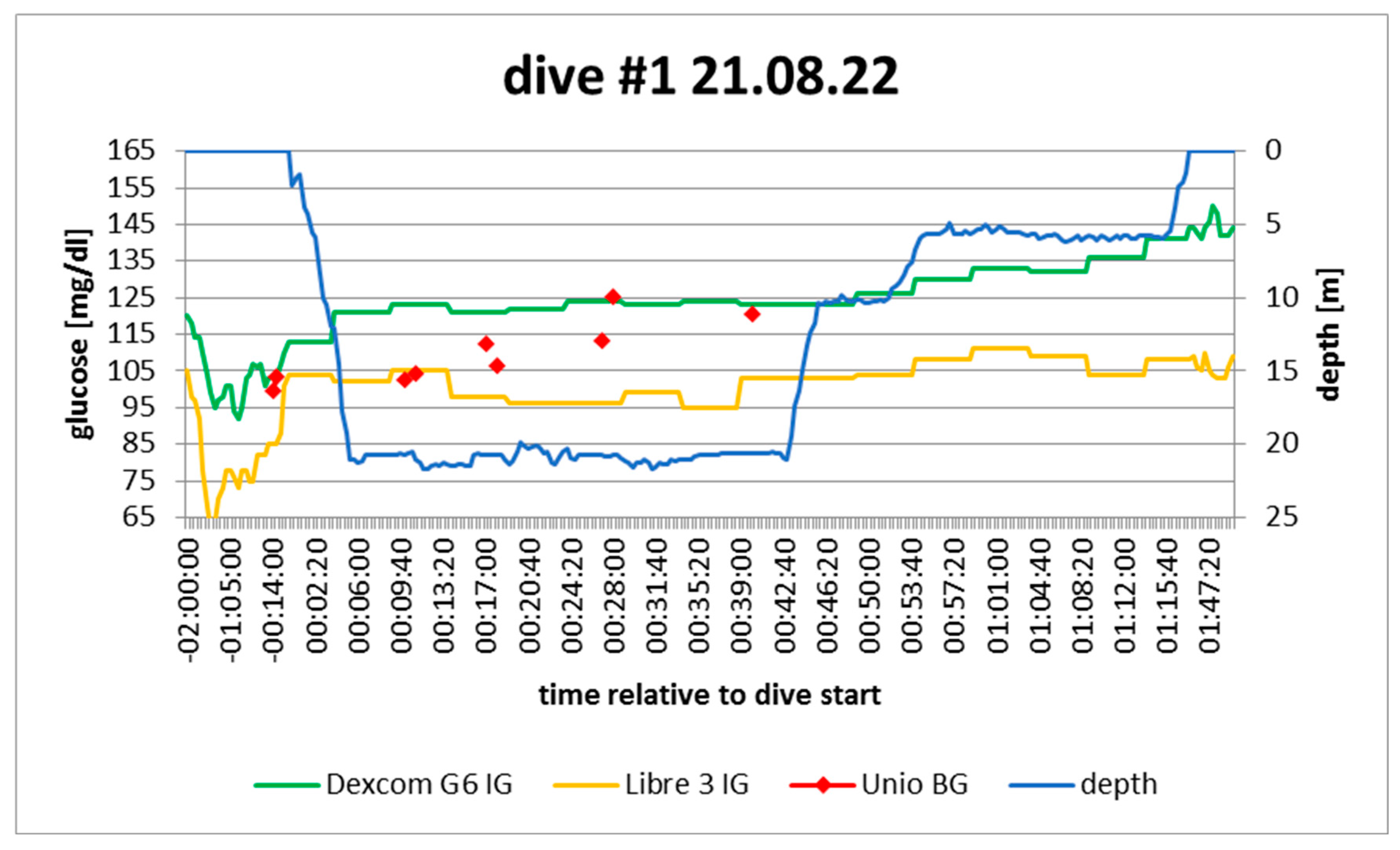

Figure 3.

dive log #1. Source: experimental dives.

Figure 3.

dive log #1. Source: experimental dives.

Active insulin: pump disconnected ca. 3h before dive; minimal tail from correction bolus

Sport: none 2h before

Food: none 2h before

Expectation: no exercise, no food, no insulin > steady to rising

In hindsight: confirmed; rise started when i) all insulin depleted and ii) freezing began

Note: no post-measurement because device dropped in water

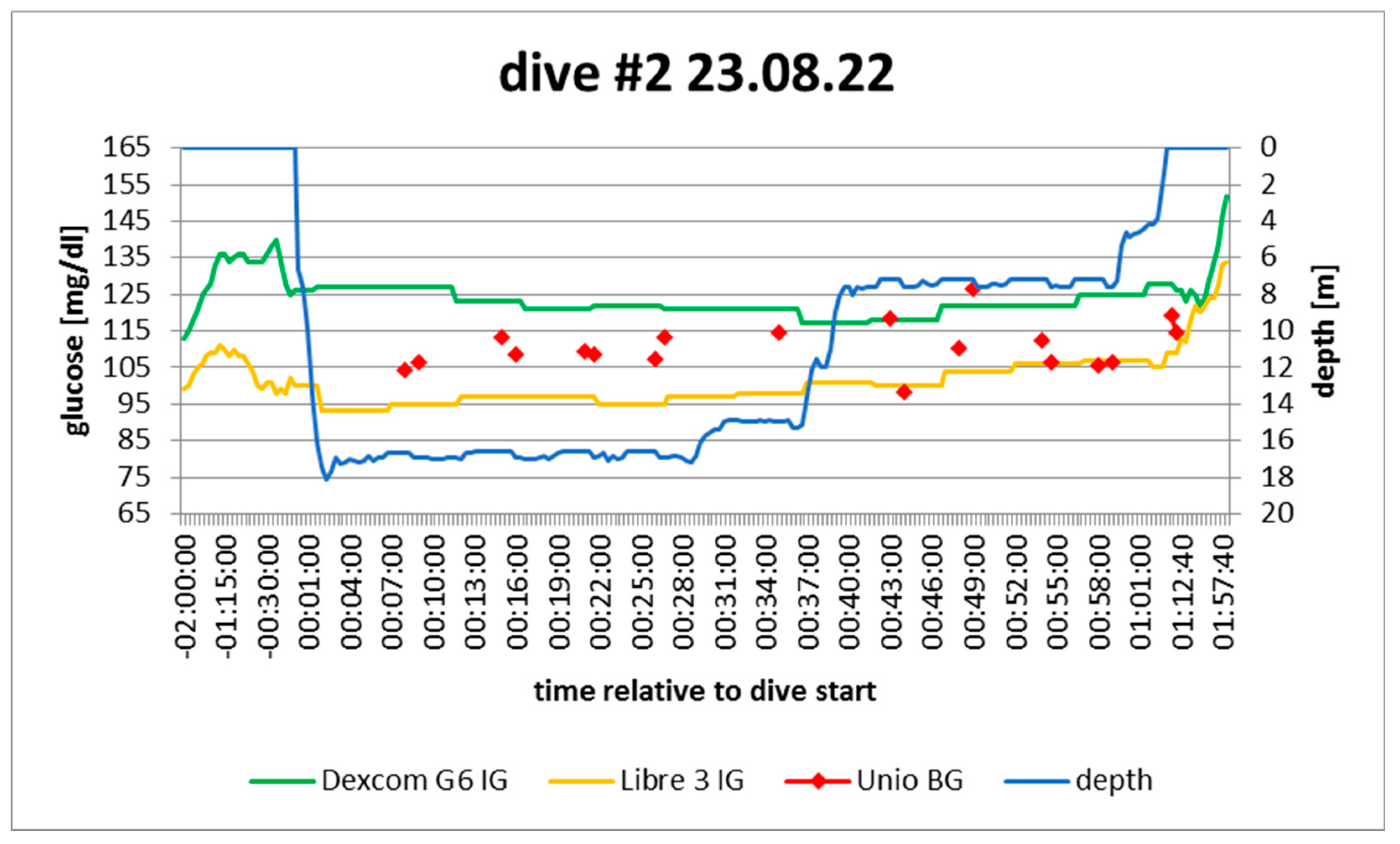

Figure 4.

dive log #2. Source: experimental dives.

Figure 4.

dive log #2. Source: experimental dives.

Active insulin: pump disconnected 50‘ before dive; minimal correction bolus at that moment

Sport: none 2h before

Food: none 2h before

Expectation: stable as no food and no exercise; no basal, but remaining bolus

In hindsight: confirmed

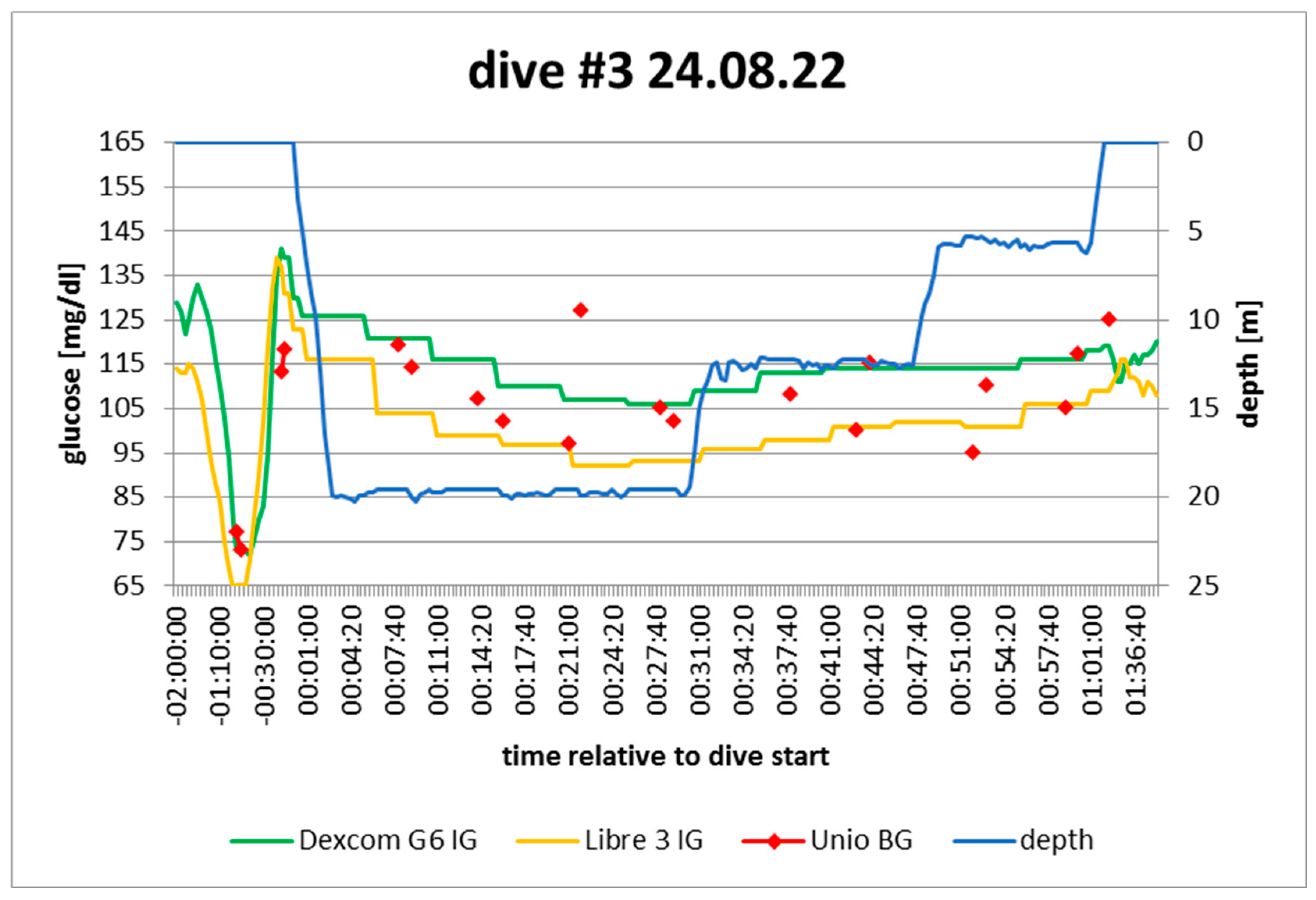

Figure 5.

dive log #3. Source: experimental dives.

Figure 5.

dive log #3. Source: experimental dives.

Active insulin: pump disconnected 45‘ before dive; small correction bolus 2.5h before dive

Sport: none 2h before

Food: 2KE 50‘ before dive

Expectation: ?: Remaining bolus vs possible late digestion of food; no exercise and no basal

In hindsight: stable

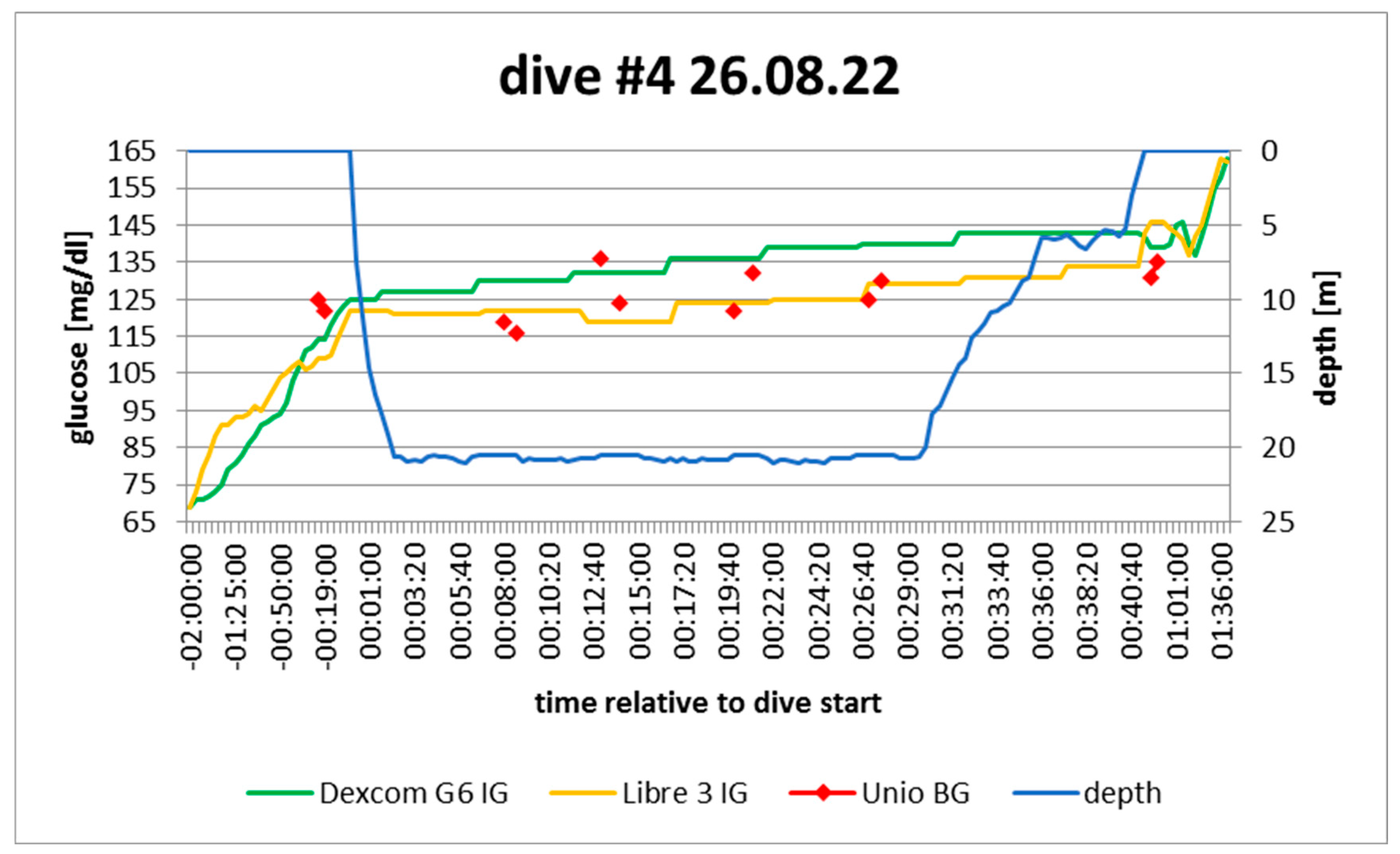

Figure 6.

dive log #4. Source: experimental dives.

Figure 6.

dive log #4. Source: experimental dives.

Active insulin: pump disconnected 1h pre-dive; no active bolus

Sport: none 2h before

Food: none 2h before

Expectation: increasing: no active insulin, no sport, no food

In hindsight: confirmed

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Both; Methodology: Both; ValidationPrimarily Daniel; Formal Analysis Primarily Philipp; Resources: both; Data curation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Visualization: Philipp; Writing – Review & Editing: Daniel.

Ethical review and approval

not applicable for this study: only analyzing BG/IG values that subjects collect as part of their ongoing monitoring anyway.

Informed Consent Statement

was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Please refer to suggested Data Availability Statements in section “MDPI Research Data Policies”. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the diving equipment and logisitcal support from Intro Dive, Tolo. A particular thanks to divemaster Will van den Heuvel for his support during the dives.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

Before conducting the experimental dives it was not clear whether pressure may have an effect on the functioning of the device, e.g. because of blood denisty on sensor. Considering the plausibility of the results, also vis a vis pre/post dive measurments, it is assumed that the BG device was not affected by pressure. |

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

References

- Edge, C.J.; Dowse, M.S.L.; Bryson, P. Scuba diving with diabetes mellitus--the UK experience 1991-2001. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2005, 32, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matteo Andrea Bonomo, Giovanni Careddu, Gerardo Corigliano, Paolo Di Bartolo, Pasquale Longobardi, Andrea Fazi, Elena Cimino, Elena Gamarra, Umberto Valentini: La persona con diabete tipo 1 e le immersioni subacquee. Rassegna 2019, 31, 22–40.

- Bonomo M, Cairoli R, Verde G, Morelli L, Moreo A, Delle Grottaglie M, Brambilla MC, Meneghini E, Aghemo P, Corigliano G, Marroni A. Safety of recreational scuba diving in type 1 diabetic patients: The Deep Monitoring programme. Diabetes Metab 2009, 35, 101–107. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lormeau, B.; Pichat, S.; Dufaitre, L.; Chamouine, A.; Gataa, M.; Rastami, J.; Coll-Lormeau, C.; Goury, G.; François, A.-L.; Etien, V.; et al. Impact of a sports project centered on scuba diving for adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: New guidelines for adolescent recreational diving, a modification of the French regulations. Archives de Pédiatrie 2019, 26, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, P.; Örnhagen, H.; Jendle, J. The Benefits of Continuous Glucose Monitoring and a Glucose Monitoring Schedule in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes during Recreational Diving. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, G.D.L.; Pollock, N.W.; Uguccioni, D.M.; Dovenbarger, J.; Feinglos, M.N.; E Moon, R. Plasma glucose responses in recreational divers with insulin-requiring diabetes. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2004, 31, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, N.W., Uguccioni, D.M., Dear GdeL, Eds. Diabetes and recreational diving: Guidelines for the future. Proceedings of the UHMS/DAN 2005 Workshop. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network; 2005. 19 June.

- Adolfsson, P.; Örnhagen, H.; Eriksson, B.M.; Cooper, K.A.; Jendle, J.; M.D.; M.E.; MacNeill, G.; Fredericks, C.; de Mol, P.; et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring—A Study of the Enlite Sensor During Hypo- and Hyperbaric Conditions. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2012, 14, 527–532. [CrossRef]

- Pieri, M.; Cialoni, D.; Marroni, A. “Continuous real time monitoring and recording of glycaemia during scuba diving: Pilot study. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2016, 43, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Reiterer, F.; Polterauer, P.; Schoemaker, M.; Schmelzeisen-Redecker, G.; Freckmann, G.; Heinemann, L.; Del Re, L. Significance and Reliability of MARD for the Accuracy of CGM Systems. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2017, 11, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, W.L., Cox. Evaluating clinical accuracy of systems for selfmonitoring of blood glucose. Diabetes Care 1987, 10, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R. A day in the life of a diabetic diver: The Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society/Divers Alert Network protocol for diving with diabetes in action. Diving Hyperb Med. 2016, 46, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lormeau, B.; Sola-Gazagnes, A.; Dufaitre, L.; Tabah, A.; Thurninger, O.; Assad, N.; Valensi, P. P2006 Intérêt d’un mélange suroxygéné (Nitrox) en plongée sous marine chez le patient diabétique de type 1. Diabetes Metab. 2013, 39, A70–A71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.W.; Uguccioni, D.M.; Del Dear, G.; Bates, S.; Albushies, T.M.; A Prosterman, S. Plasma glucose response to recreational diving in novice teenage divers with insulin-requiring diabetes mellitus. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 2006, 33, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).