Submitted:

03 July 2023

Posted:

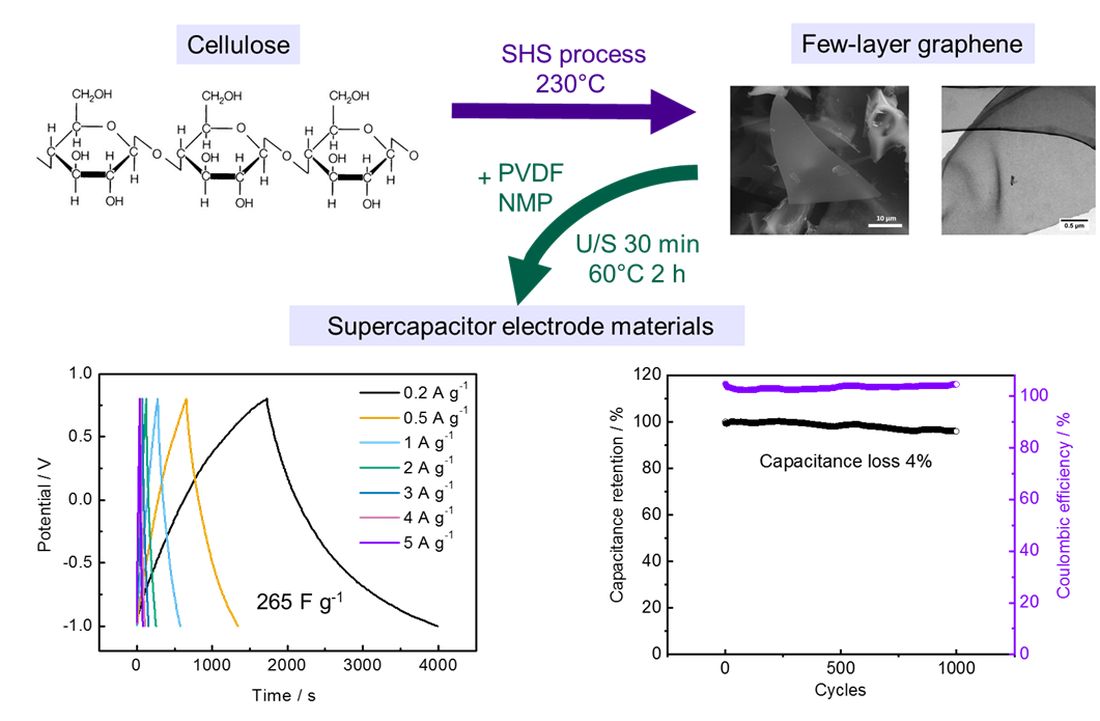

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of FLG

2.2. Methods for the Characterization of FLG

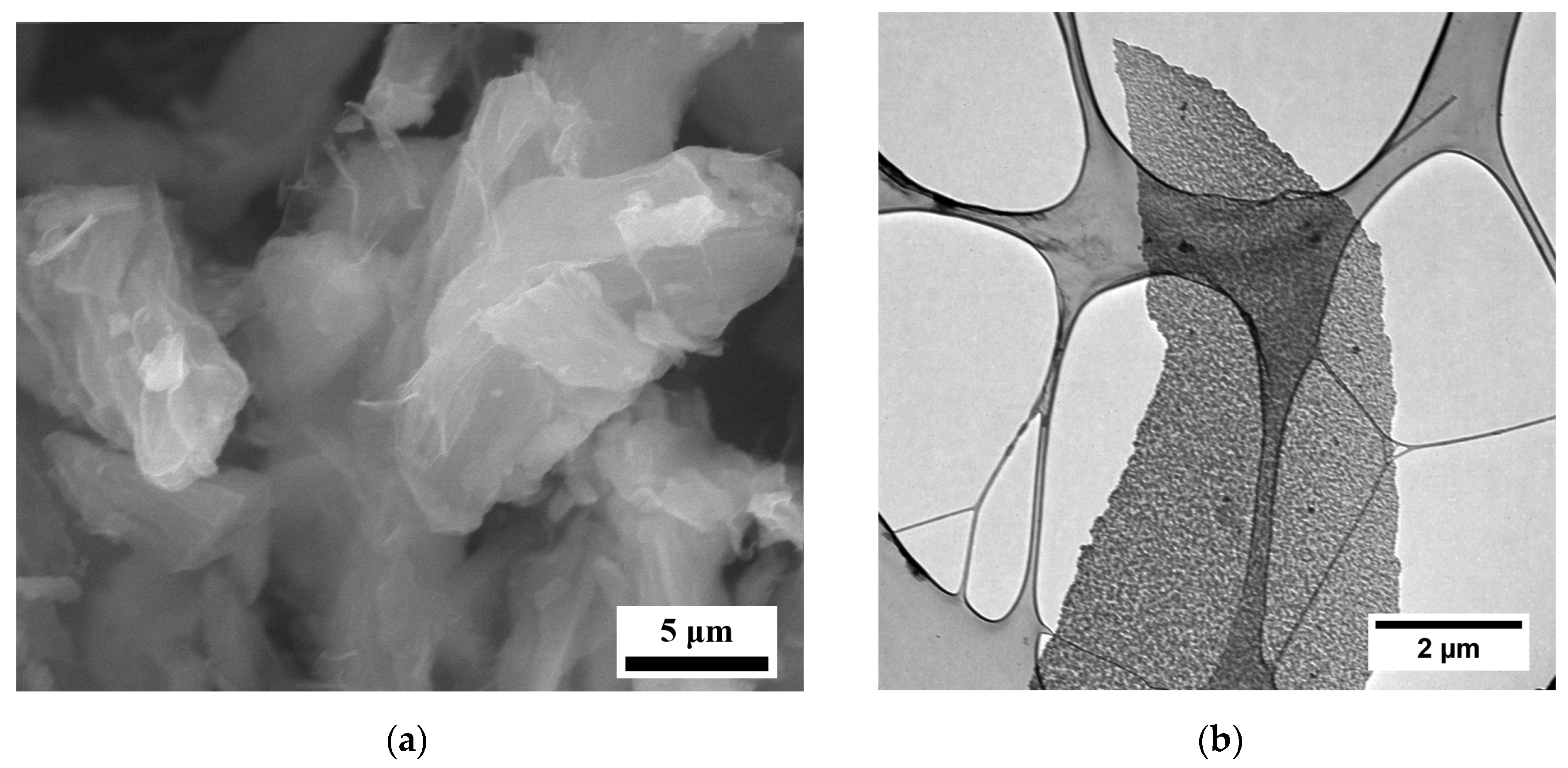

2.2.1. Electron Microscopy

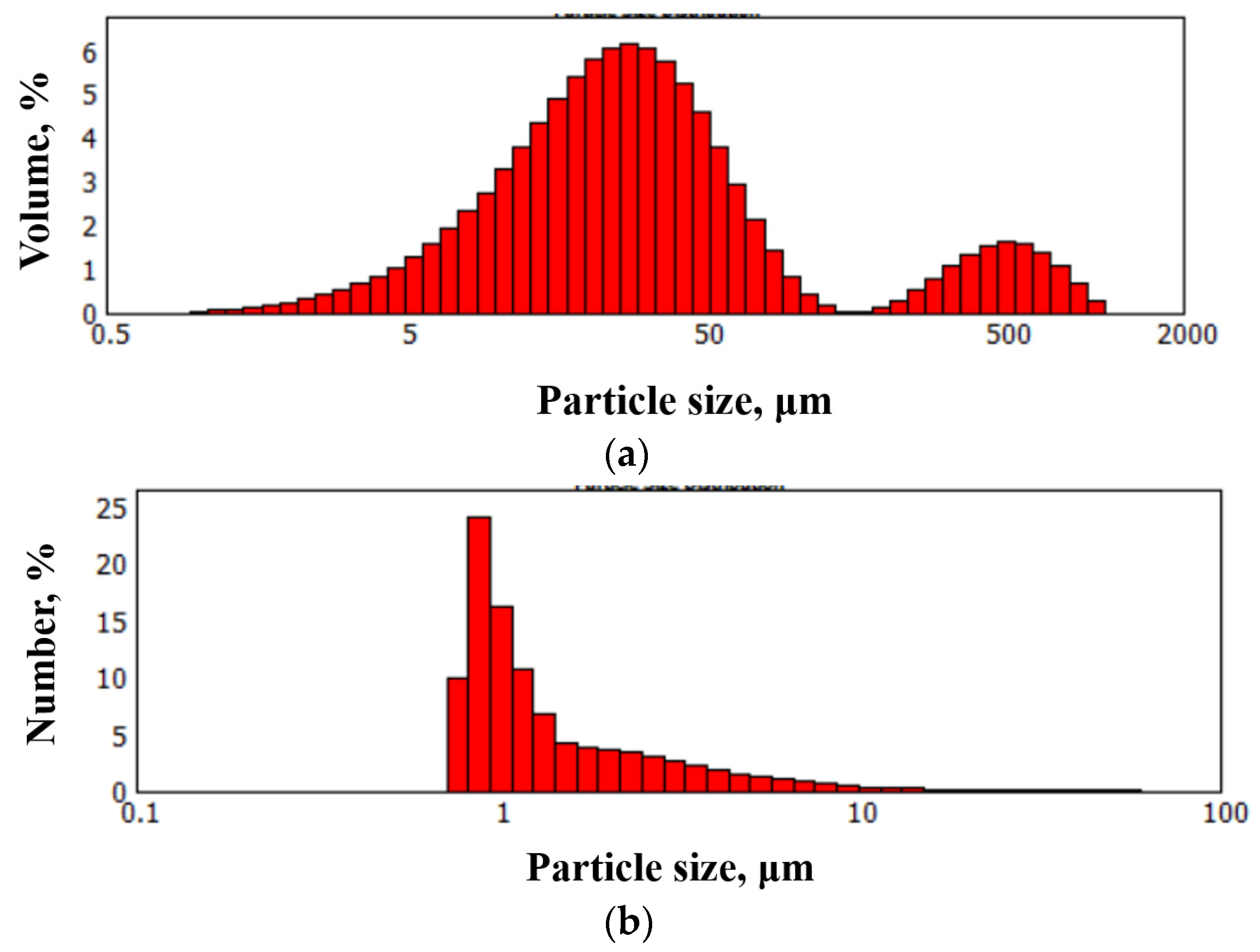

2.2.2. Dispersion Measurement

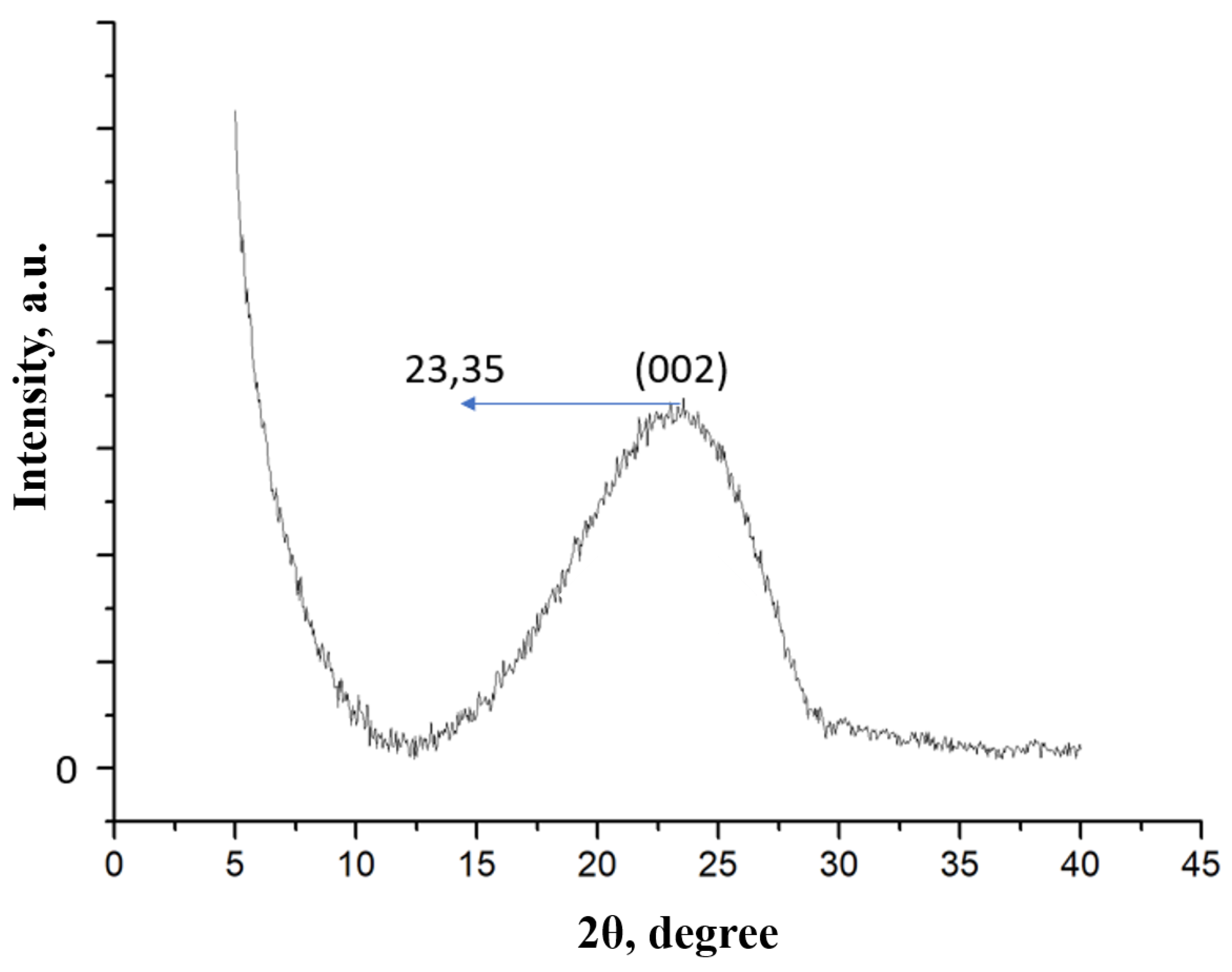

2.2.3. X-ray Diffraction

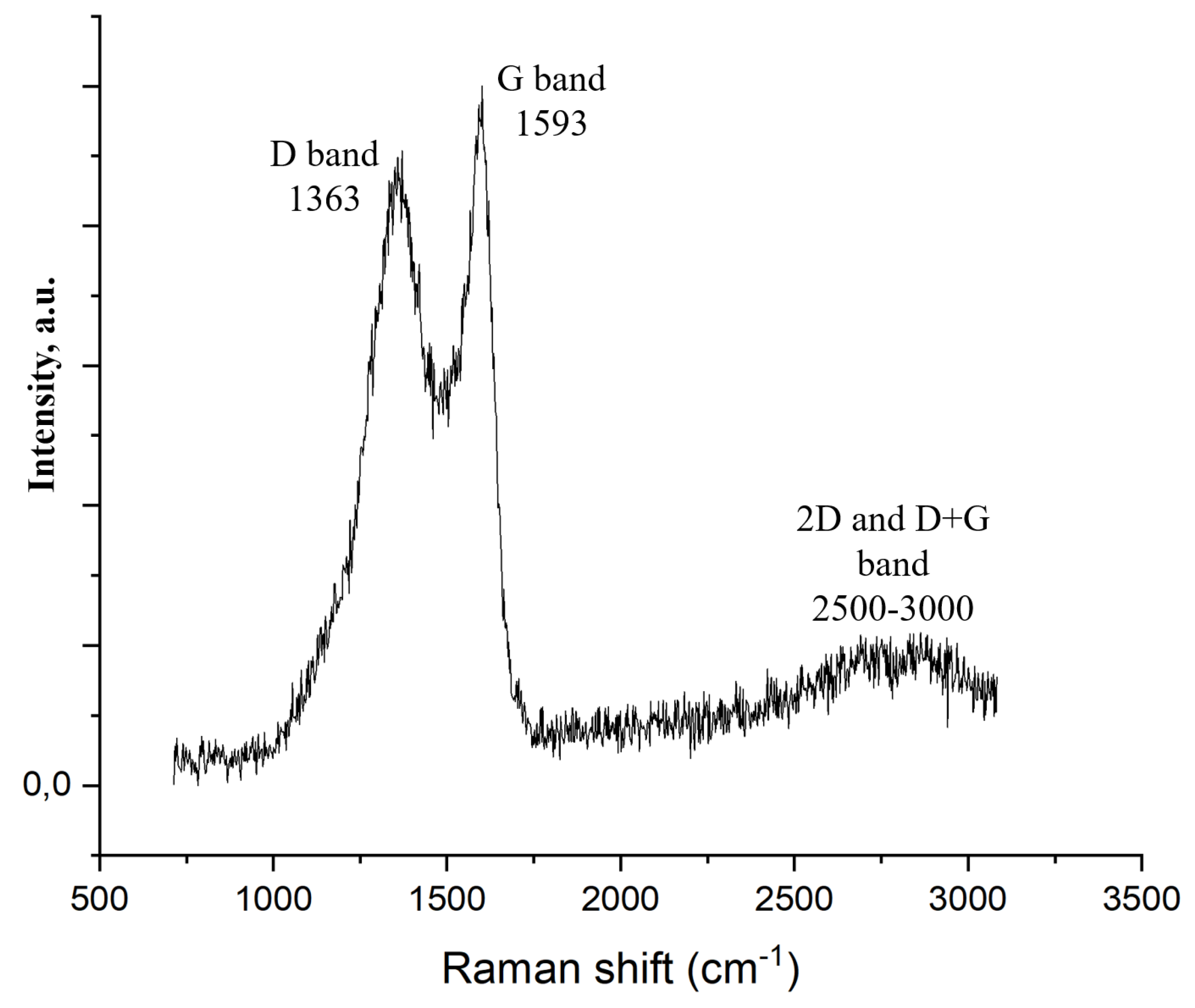

2.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

2.2.5. Specific Surface Area Measurement

2.3. Preparation of Electrodes from FLG

2.4. Electrochemical Measurement Technique

2.5. Specific capacitance

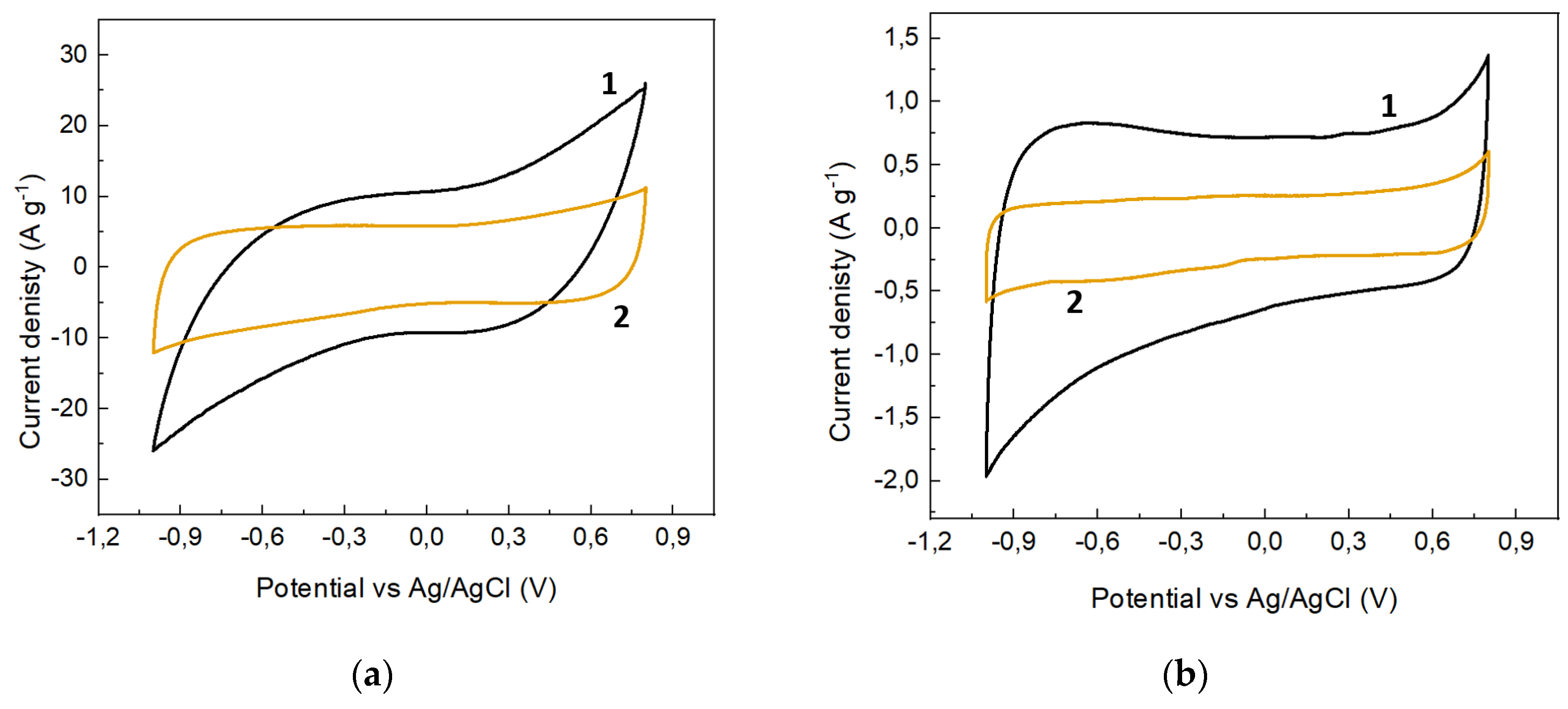

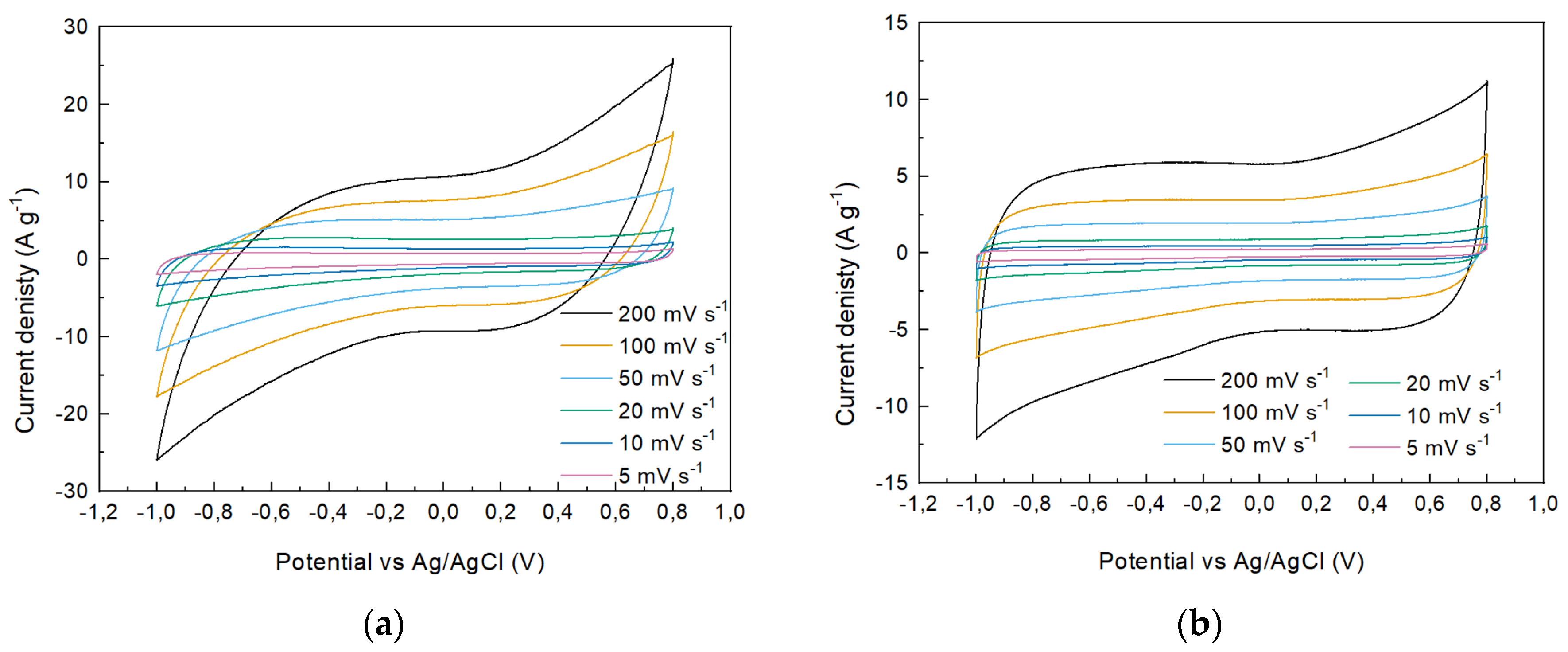

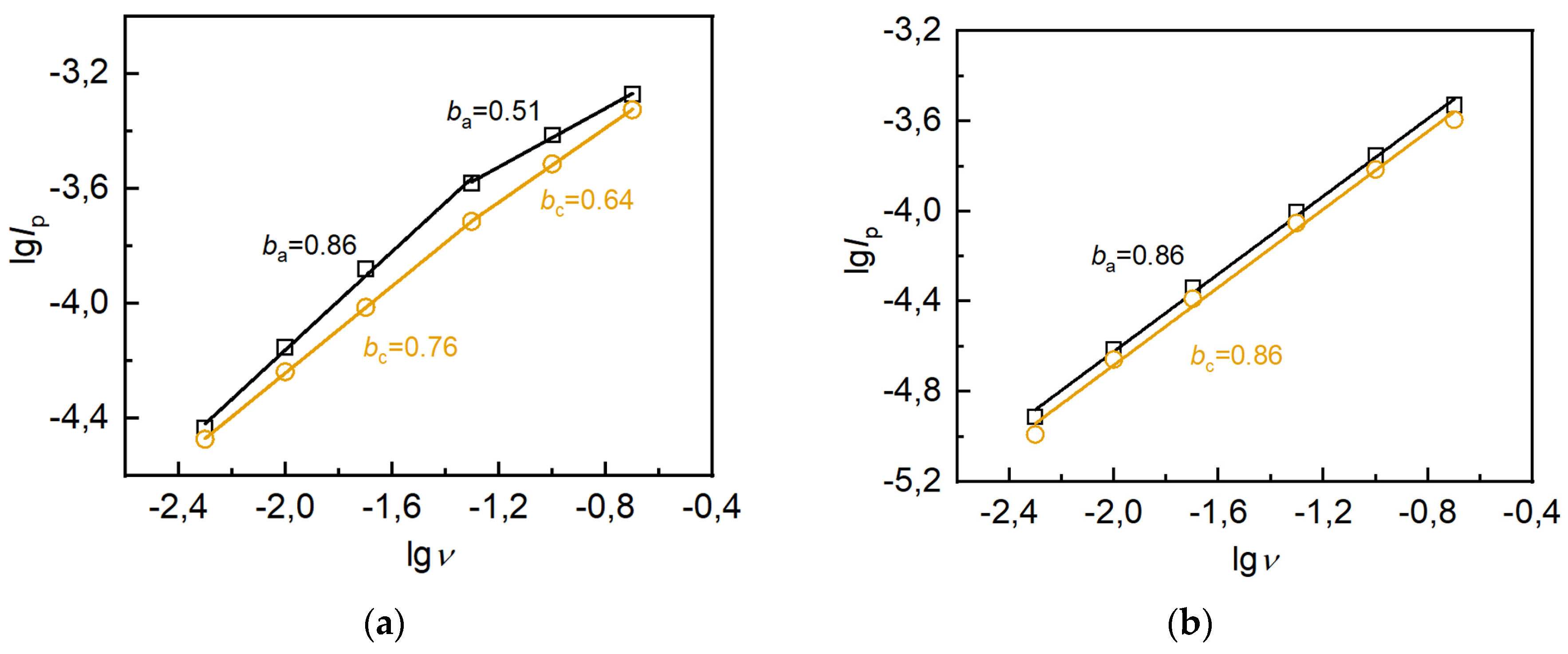

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ataca, C.; Ciraci, S. Perpendicular growth of carbon chains on graphene from first-principles. Phys. Rev. B. 2011, 83, 235417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Mohamed, A.; Ayob, A. Review of energy storage systems for electric vehicle applications: Issues and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Mitra, S.; Basak, M.; Banerjee, T. A comprehensive review on batteries and supercapacitors: development and challenges since their inception. Energy Storag. 2023, 5, e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsherif, S.A.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Ghany, N.A. A. Graphene fabricated by different approaches for supercapacitors with ultrahigh volumetric capacitance. J. Energy Storag. 2022, 50, 104281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Rakhi, R.B.; Hu, L.; Xie, X.; Cui, Y.; Alshareef, H.N. High-performance nanostructured supercapacitors on a sponge. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5165–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.I. Low voltage electrolytic capacitor. US Patent 2800616, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Bhatti, T.S. A review on electrochemical double-layer capacitors. Energy Convers. Manage. 2010, 51, 2901–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo, A.; Hollenkamp, A. Electrochemical capacitors–scientific fundamentals and technological applications. J Power Sources. 2006, 157, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y.; Dunn, B. Where do batteries end and supercapacitors begin? Science. 2014, 343, 1210–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Arora, A.; Tripathi, S.K. Review of supercapacitors: Materials and devices. J. Energy Storag. 2019, 21, 801–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, W.K.; Lim, H.N.; Zainal, Z.; Huang, N.M.; Harrison, I.; Andou, Y. Flexible graphene-based supercapacitors: a review. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 4153–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ni, M.; Ren, X.; Tian, Y.; Li, N.; Su, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphene in supercapacitor applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 20, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Konno, H.; Tanaike, O. Carbon materials for electrochemical capacitors. J. Power Sources. 2010, 195, 7880–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Nanostructured activated carbons from natural precursors for electrical double layer capacitors. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.R.; Simon, P. The chalkboard: Fundamentals of electrochemical capacitor design and operation. Electrochem. Soc. Interface. 2008, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. ; Zhang, L.; Zhang, A Review of Electrolyte Materials and Compositions for Electrochemical Supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7431–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Yushin, G. Review of nanostructured carbon materials for electrochemical capacitor applications: advantages and limitations of activated carbon, carbide-derived carbon, zeolite-templated carbon, carbon aerogels, carbon nanotubes, onion-like carbon, and graphene. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2014, 3, 424–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, T.M.; Heon, M.; Presser, V.; Hillesheim, P.C.; Dai, S.; Gogotsi, Y.; Kalinin, S.; Balke, N. In situ tracking of the nanoscale expansion of porous carbon electrodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ni, J.; Li, Y. Carbon nanotube-based electrodes for flexible supercapacitors. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 1825–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Niu, Z.; Chen, J. Flexible supercapacitors based on carbon nanotubes. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, X.; Yushin, G. Nanostructured activated carbons for supercapacitors. Nanocarbons Adv. Energy Storag. 2015, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.B.; Lee, J.M. Graphene for supercapacitor applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2013, 1, 14814–14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakra, R.; Kumar, R.; Sahoo, P.K.; Thatoi, D.; Soam, A. A mini-review: Graphene based composites for supercapacitor application. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 133, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Abdala, A.A. ve Macosko, CW, Graphene/polymer nanocomposites. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6515–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, J.; Thanh, T.D.; Heo, S.B.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Novel route to synthesis of N-doped graphene/Cu–Ni oxide composite for high electrochemical performance. Carbon. 2015, 94, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermisoglou, E.C.; Giannakopoulou, T.; Romanos, G.; Boukos, N.; Psycharis, V.; Lei, C.; Lekakou, C.; Petridis, D.; Trapalis, C. (2017). Graphene-based materials via benzidine-assisted exfoliation and reduction of graphite oxide and their electrochemical properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 392, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Pan, F.; Li, Y. A review on the effects of TiO2 surface point defects on CO2 photoreduction with H2O. J. of Materiomics. 2017, 3, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Lau, A.; Ma, T.; Lin, H.; Jia, B. Hybridized graphene for supercapacitors: Beyond the limitation of pure graphene. Small. 2021, 17, 2007311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M.; Gupta, B.; MacLeod, J.; Liu, J.; Motta, N. Graphene-based supercapacitor electrodes: Addressing challenges in mechanisms and materials. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 17, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Salehiyan, R.; Chauke, V.; Botlhoko, O.J.; Setshedi, K.; Scriba, M.; Masukume, M. Ray, S.S. Top-down synthesis of graphene: A comprehensive review. FlatChem. 2021, 27, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, T.; Wang, Y.; Hahn, Y.B. Graphene and its derivatives for solar cells application. Nano Energy. 2018, 47, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Hiew, B.Y. Z.; Lai, K.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Gan, S.; Thangalazhy-Gopakumar, S.; Rigby, S. Review on graphene and its derivatives: Synthesis methods and potential industrial implementation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 98, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voznyakovskii, A.; Vozniakovskii, A.; Kidalov, S. New Way of Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene Nanosheets by the Self Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis Method from Biopolymers. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voznyakovskii, A.; Neverovskaya, A.; Vozniakovskii, A.; Kidalov, S. A Quantitative Chemical Method for Determining the Surface Concentration of Stone–Wales Defects for 1D and 2D Carbon Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidalov, S.; Voznyakovskii, A.; Vozniakovskii, A.; Titova, S.; Auchynnikau, Y. The Effect of Few-Layer Graphene on the Complex of Hardness, Strength, and Thermo Physical Properties of Polymer Composite Materials Produced by Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing. Materials 2023, 16, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyushin, M.A.; Voznyakovskii, A.P.; Shugalei, I.; Vozniakovskii, A.A. Carbonization of Biopolymers as a Method for Producing a Photosensitizing Additive for Energy Materials. Nanomanufacturing 2023, 3, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wei, X.; Henderson, W.A.; Shao, Y.; Chen, J.; Bhattacharya, P.; Xiao, J.; Liu, J. On the way toward understanding solution chemistry of lithium polysulfides for high energy Li–S redox flow batteries. Adv. Energy Mater., 2015, 5, 1500113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.L. The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johra, F.T.; Lee, J.W.; Jung, W.G. Facile and safe graphene preparation on solution based platform. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 2883–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, X.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Ma, Y. Scalable self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of graphene for supercapacitors with superior power density and cyclic stability. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamental and Applications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 267–305. [Google Scholar]

- De Levie, R. On porous electrodes in electrolyte solutions: I. Capacitance effects. Electrochim. Acta. 1963, 8, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| s-1 | g-1 | |

|---|---|---|

| FLG | AC | |

| 200 | 65 | 35 |

| 100 | 83 | 38 |

| 50 | 105 | 43 |

| 20 | 135 | 50 |

| 10 | 151 | 57 |

| 5 | 170 | 65 |

| g-1 | g-1 | |

|---|---|---|

| FLG | AC | |

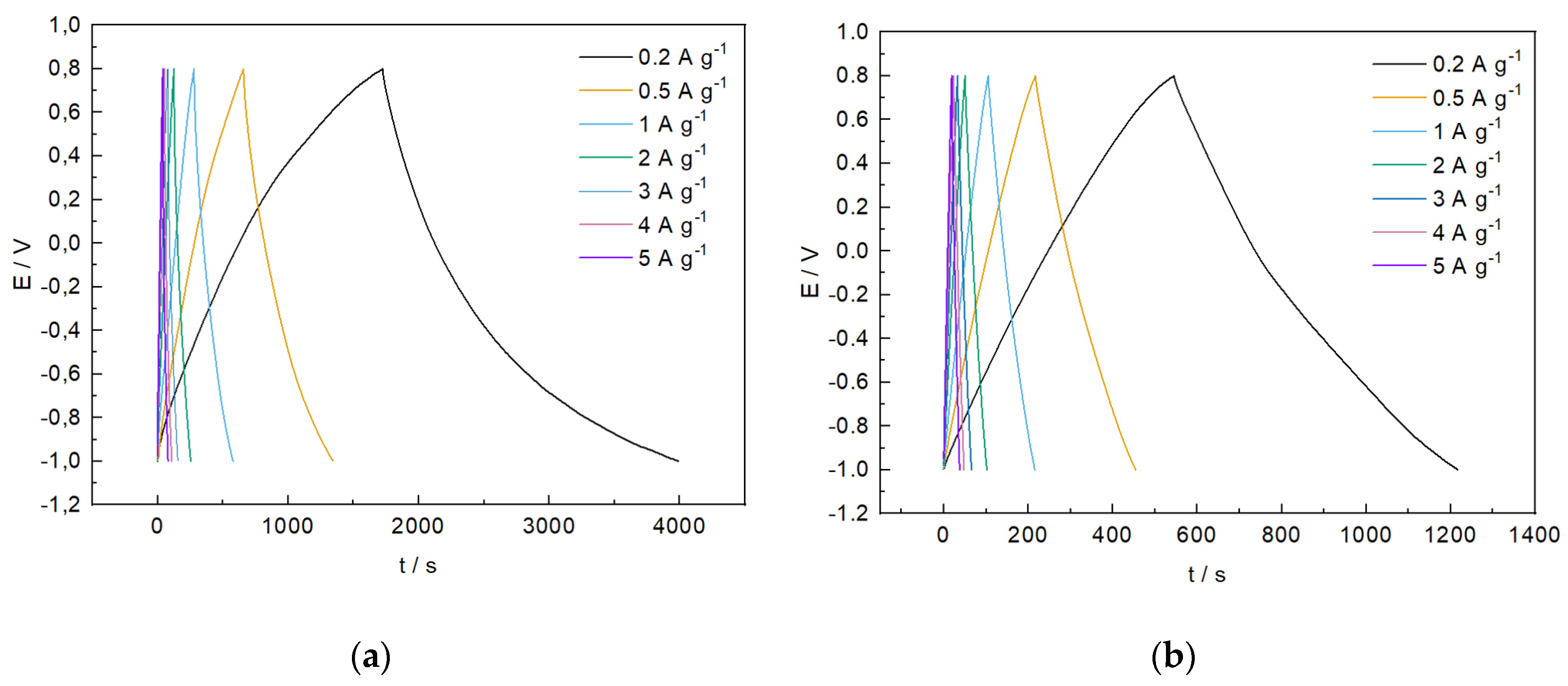

| 0.2 | 265 | 75 |

| 0.5 | 194 | 67 |

| 1 | 168 | 62 |

| 2 | 145 | 58 |

| 3 | 130 | 56 |

| 4 | 121 | 54 |

| 5 | 113 | 52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).