Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

04 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

- Specifically, the type and number of services as well as the frequency of claims.

- Specifically, any difference between time taken from the injury date to RTW date, adjusting for explanatory variables (age, gender, type of injury and occupation) as required.

- The time to RTW is a common measure to evaluate the performance and success of injury intervention and healthcare improvement programs [11, 12].

1.2. Definitions

- EIPF – Early Intervention Physiotherapy Framework program (the intervention)

- EP – Physiotherapists who completed EIPF program

- RP – Regular physiotherapists who did not complete the EIPF program

- WSV – WorkSafe Victoria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

- Claims that had at least one day of wage compensation payment (standard time loss claims) with the injury date on or after the first of January 2010,

- Claims that had physiotherapy services provided either by EP or RP,

- Claims that had their initial physiotherapy consultation on or after the first of August 2014,

- If claims resulted in RTW, only claims with RTW on or after the date of initial consultation were included.

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.1.1. Description of Dataset

3.1.2. Services and Claims

3.1.3. Time to Achieving RTW

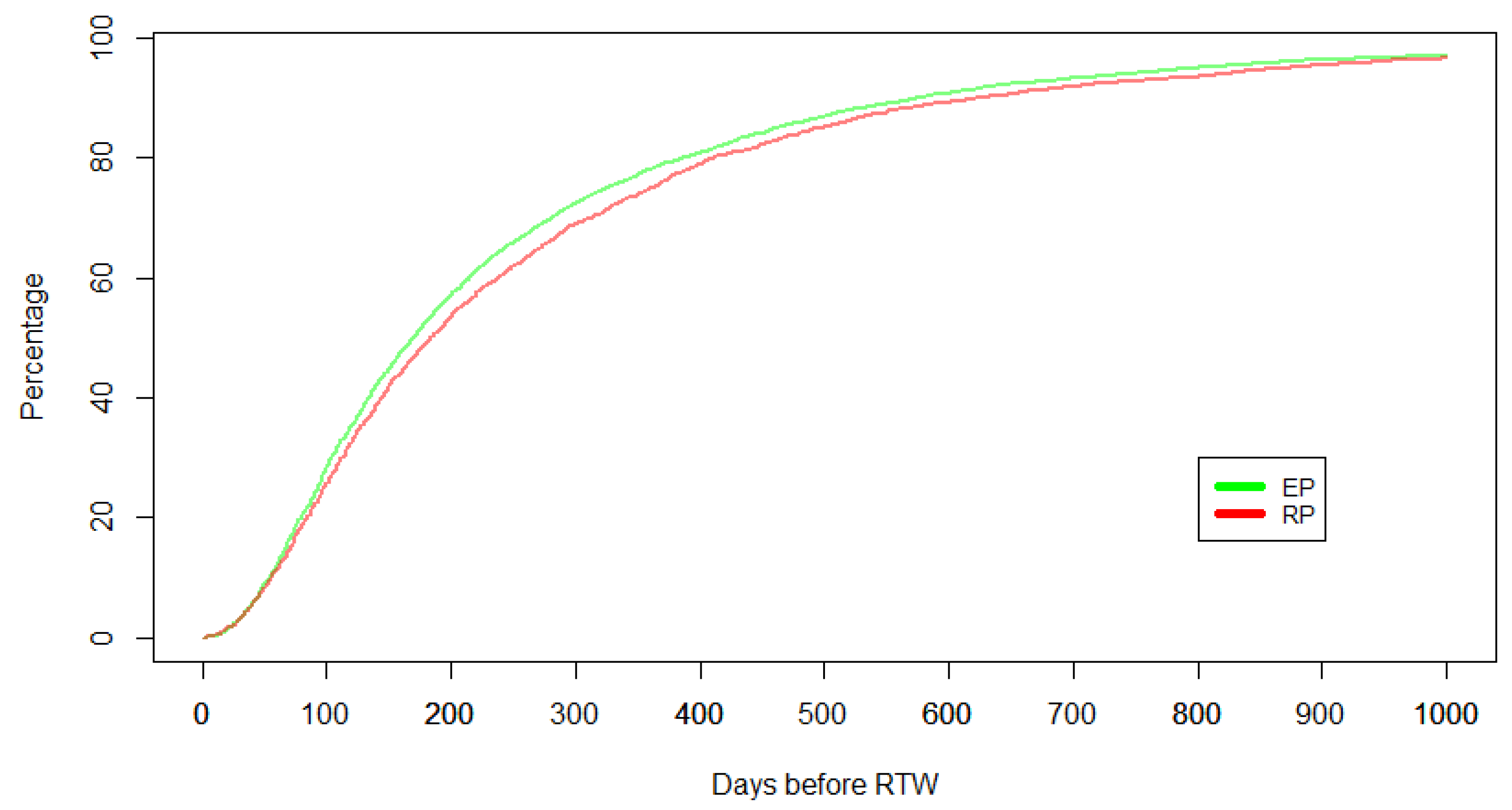

3.2. Survival Analysis

3.3. Regression Analysis

3.3.1. Univariate Analysis

3.3.2. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

- Physiotherapists in the EP group visited more WSV clients per physiotherapist (average of 10.2 claims) than those in the RP group (average of 4.6 claims) over the three-year period.

- Injured workers returned to work on average 25 days sooner when treated by EP compared with RP. This could be a direct result of EIPF by motivating physiotherapists (EP group) for earlier post-injury intervention.

- Survival analysis showed that the clients of the EP group returned to work significantly faster than the RP group. After two years, this difference became statistically significant shown by the log-rank test, confirming the necessity of three-year follow-up analysis such as that performed in this study.

- The time to return to work was significantly associated with age and injury type in both physiotherapy groups. Younger injured workers (between 15 and 24 years old) with fractures had returned to work faster, and the injured workers between 45 and 54 years old with musculoskeletal injuries had taken more time to get back to work.

- After adjusting age and injury type variables, injured workers in the EP group still returned to work significantly faster than those treated in the RP group (by 21 days). These results show that the difference between the two groups was substantially related to the early intervention by EP physiotherapists post-injury.

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| Title and abstract | ||

| 1 | Title | Our paper includes a title which reflects the aim of the study |

| 2 | Abstract | Our paper includes an abstract which provides a summary of background, objectives, study design, participants, predictors, outcomes, statistical analysis, results and conclusions. |

| Introduction | ||

| 3 | Background and objectives | Our paper specifies the objectives, explains the background of the study and refers to existing studies. |

| Methods | ||

| 4 | Source of data | Our paper describes the source of data and specifies the selection criteria. |

| 5 | Participants | Our paper specifies who participated in the study. |

| 6 | Outcome | Our paper defines the outcomes clearly. |

| 7 | Predictors | Our paper clearly explains all predictors used in analyses. |

| 8 | Sample size | Our paper mentions the sample size for both intervention and control groups. |

| 9 | Missing data | There were no missing data. |

| 10 | Statistical analysis methods | Our paper describes all the statistical analysis methods used in the study. |

| 11 | Risk groups | We did not have any risk group in our study. |

| 12 | Development vs validation | Our paper compares the distribution of categories in intervention and control groups. |

| Results | ||

| 13 | Participants | Our paper includes descriptive statistics about participants. |

| 14 | Model development | Our paper compares two groups using descriptive statistics, survival analysis and regression models. |

| 15 | Model specification | Our paper reports all parameters associated with the statistical analysis methods. |

| 16 | Model performance | Our paper presents the results of statistical tests for comparison. |

| 17 | Model updating | Our paper explains how we adjusted for the impact of other predictors on the comparison. |

| Discussion | ||

| 18 | Limitations | Our paper lists limitations and refers to potential future work to address these. |

| 19 | Interpretation | Our paper discusses the results and interprets the outcomes considering the research questions and goals. |

| 20 | Implications | Our paper discusses how the results provide insights on the performance of an early intervention program. |

| Other information | ||

| 21 | Supplementary information | Our paper provides information about ethics. |

| 22 | Funding | Our paper acknowledges the source of funding for the study. |

References

- Berecki-Gisolf, J., A. Collie, and R.J. McClure, Determinants of physical therapy use by compensated workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2013. 23(1): p. 63-73.

- Centre, T.S.R. Return to work survey - 2016 (Australia and New Zealand). 2016; Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1703/return-to-work-survey-2016-summary-research-report_0.pdf.

- Pransky, G., et al., Improving return to work research. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2005. 15(4): p. 453-457.

- Khorshidi, H.A., et al., Early identification of undesirable outcomes for transport accident injured patients using semi-supervised clustering. Studies in health technology and informatics, 2019. 266: p. 1-6.

- Nicholas, M., et al., Implementation of Early Intervention Protocol in Australia for ‘High Risk’Injured Workers is Associated with Fewer Lost Work Days Over 2 Years Than Usual (Stepped) Care. Journal of occupational rehabilitation: p. 1-12.

- Association, A.P. The physiotherapists' role in occupational rehabilitation. 2012; Available from: https://www.physiotherapy.asn.au/DocumentsFolder/APAWCM/Advocacy/PositionStatement_2017_Thephysiotherapist%E2%80%99s_role_occ_rehabilitation.pdf.

- Donovan, M., A. Khan, and V. Johnston, The Contribution of Onsite Physiotherapy to an Integrated Model for Managing Work Injuries: A Follow Up Study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2021. 31(1): p. 207-218.

- St-Georges, M., N. Hutting, and A. Hudon, Competencies for Physiotherapists Working to Facilitate Rehabilitation, Work Participation and Return to Work for Workers with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Scoping Review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2022. 32(4): p. 637-651.

- Victoria, W. Early Intervention Physiotherapy Framework (EIPF) 2020; Available from: https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/early-intervention-physiotherapy-framework-eipf.

- Gosling, C., et al., Strategies to enable physiotherapists to promote timely return to work following injury. 2015.

- Awang, H. and N. Mansor, Predicting Employment Status of Injured Workers Following a Case Management Intervention. Safety and Health at Work, 2017.

- Choi, K., et al., Time to return to work following workplace violence among direct healthcare and social workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2020.

- Collins, G.S., et al., Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD Statement. BMC Medicine, 2015. 13(1): p. 1.

- Khorshidi, H.A., B. Hassani-Mahmooei, and G. Haffari Hassani-Mahmooei, and G. Haffari, An Interpretable Algorithm on Post-injury Health Service Utilization Patterns to Predict Injury Outcomes. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2020. 30: p. 331–342.

- Prang, K.H., B. Hassani-Mahmooei, and A. Collie, Compensation Research Database: population-based injury data for surveillance, linkage and mining. BMC Research Notes, 2016. 9(1): p. 1-11.

- Stel, V.S., et al., Survival Analysis I: The Kaplan-Meier Method. Nephron Clinical Practice, 2011. 119(1): p. c83-c88.

- Martinez, M.C. and F.M. Fischer, Work ability and job survival: Four-year follow-up. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019. 16(17).

- Md Noor, A.K.C., et al., Survival time of visual gains after diabetic vitrectomy and its relationship with ischemic heart disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020. 17(1).

- Khorshidi, H.A., M. Marembo, and U. Aickelin, Predictors of Return to Work for Occupational Rehabilitation Users in Work-Related Injury Insurance Claims: Insights from Mental Health. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 2019. 29: p. 740–753.

| Claimant characteristics | EP | RP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 4,909 | 66.67 % | 2,563 | 64.11 % |

| Female | 2,454 | 33.33 % | 1,435 | 35.89 % |

| Age groups | ||||

| 15-24 | 552 | 7.50 % | 298 | 7.45 % |

| 25-34 | 1,269 | 17.23 % | 698 | 17.46 % |

| 35-44 | 1,610 | 21.87 % | 803 | 20.09 % |

| 45-54 | 2,120 | 28.79 % | 1,104 | 27.61 % |

| 55-64 | 1,622 | 22.03 % | 952 | 23.81 % |

| Others | 190 | 2.58 % | 143 | 3.58 % |

| Injury type | ||||

| Fractures | 1,090 | 14.80 % | 594 | 14.86 % |

| Joints | 1,887 | 25.63 % | 1,062 | 26.56 % |

| Mental | 35 | 0.48 % | 16 | 0.40 % |

| Musculoskeletal | 3,442 | 46.75 % | 1,902 | 47.57 % |

| Wounds | 606 | 8.23 % | 241 | 6.03 % |

| Other injuries | 142 | 1.93 % | 98 | 2.45 % |

| Other diseases | 161 | 2.19 % | 85 | 2.13 % |

| Occupation groups | ||||

| Managers | 224 | 3.04 % | 161 | 4.03 % |

| Professionals | 659 | 8.95 % | 432 | 10.81 % |

| Associate professionals | 604 | 8.20 % | 387 | 9.68 % |

| Tradespersons | 1,403 | 19.05 % | 694 | 17.36 % |

| Advanced clerical and Service workers | 84 | 1.14 % | 68 | 1.70 % |

| Intermediate clerical, sales and Service workers | 817 | 11.10 % | 479 | 11.98 % |

| Intermediate production and transport workers | 1,677 | 22.78 % | 741 | 18.53 % |

| Elementary clerical, sales and Service workers | 288 | 3.91 % | 179 | 4.48 % |

| Laborers | 1,607 | 21.83 % | 857 | 21.44 % |

| Measures | EP | RP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |

| Number of claims treated per physiotherapist | 10.2* | [9.6, 10.8] | 4.6 | [4.3, 4.9] |

| Physiotherapy services per claim | 29.6 | [28.9, 30.4] | 28.5 | [24.4, 29.6] |

| Measures | EP | RP | Difference (EP-RP) |

p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |||

| Days from date of Injury to RTW | 267.7 | [259.3, 276.2] | 289.1 | [277.0, 301.2] | - 25.4 | <0.01 |

| Time period (months) | RTW percentage | Log-rank test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | RP | Chi-square stat | P-value | |

| 3 | 23.90 % | 22.23 % | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| 6 | 53.31 % | 49.72 % | 0.22 | 0.64 |

| 12 | 78.53 % | 75.30 % | 2.83 | 0.09 |

| 24 | 93.69 % | 92.54 % | 6.94 | <0.001 |

| 36 | 96.93 % | 96.51 % | 12.11 | <0.001 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Variable p-value | Coefficient | Model p-value | |

| Physiotherapy group | < 0.0001 | |||

| RP | Ref | < 0.01 | Ref | |

| EP | -21.38 | -21.57 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Ref | n.s. | - | |

| Female | 4.77 | - | ||

| Age groups | ||||

| 15-24 | Ref | < 0.0001 | Ref | |

| 25-34 | 26.39 | 14.60 | ||

| 35-44 | 87.84 | 68.55 | ||

| 45-54 | 93.62 | 78.58 | ||

| 55-64 | 59.63 | 49.33 | ||

| Others | 9.33 | 0.77 | ||

| Injury type | ||||

| Fractures | Ref | < 0.0001 | Ref | |

| Joints | 53.34 | 51.80 | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 179.22 | 159.78 | ||

| Mental | 97.92 | 94.63 | ||

| Other Diseases | -22.47 | -16.13 | ||

| Other Injuries | 61.83 | 62.05 | ||

| Wounds | 144.06 | 130.42 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Managers | Ref | n.s. | - | |

| Professionals | 303.68 | - | ||

| Associate professionals | -35.51 | - | ||

| Tradespersons | -31.52 | - | ||

| Advanced clerical & service workers | -29.55 | - | ||

| Intermediate clerical, sales & service workers | 1.37 | - | ||

| Intermediate production & transport workers | -43.97 | - | ||

| Elementary clerical, sales & service workers | -36.85 | - | ||

| Labourers | -8.73 | - | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).