1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the leading male cancer diagnosis in the United States and has seen an incidence rate increase of 3% annually between 2014 through 2019. PCa has a lifetime probability of 1 in 8 men developing invasive prostate cancer, and constitutes an estimated 288,300 new male cancer diagnoses in 2023 [

1]. Although PCa is expected to account for 27% of new male cancer diagnoses, not all cases have high metastatic potential or mortality risk. Despite this, and improved screening and treatment, an estimated 20% to 30% of prostate cancer patients will experience biochemical recurrence (BCR) within five years of treatment [

2,

3,

4].

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MP-MRI), including T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps calculated from diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), has been used to assess PCa and has been a promising tool in diagnosing high-grade PCa [

5,

6,

7]. The Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) has standardized acquisition, interpretation, and reporting of prostate MRI. PI-RADS has aided in the detection of cancerous lesions and has improved consistency of clinical radiology reads [

8,

9,

10,

11]. While PI-RADS has improved cancer detection and is frequently used for biopsy guidance, it has not improved stratification of patients at risk of BCR, therefore, there has been an increase in studies attempting to detect PCa with high metastatic potential [

12,

13,

14].

PCa histology is graded using the Gleason grading scale, which assigns a score corresponding to the Gleason grades of the two most prevalent cell patterns. These patterns have more recently been used to assign patients into one of five Grade Groups (GG) to predict prognosis [

15]. Low risk cancers, detected through biopsies, may be managed through active surveillance using prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood tests. Clinically significant cancer (GG ≥ 2, tumor volume ≥ 0.5 mL, or clinical stage ≥ T3) is more often treated with radical prostatectomy, or removal of the prostate, and/or radiation. Prostatectomy is considered curative if tumors are organ-confined; however, distant metastases may form and result in biochemical recurrence. Currently, PSA is the only validated biomarker for BCR [

2], which is often defined as a rise of PSA from 0 ng/mL after surgery to greater than 0.1 or 0.2 ng/mL [

3,

4]. Improved strategies for predicting biochemical recurrence of PCa have been increasingly assessed in pathological studies: however, few studies using MRI-based features have been used to noninvasively predict BCR.

Radiomics is a multi-step process where quantitative features or textures from MR images are extracted using data-characterization algorithms to decode underlying tissue characteristics [

7,

8]. Radiomic features contain first-, second-, and higher-order statistics that are combined with other patient data to develop models that may detect and characterize a clinically relevant outcome [

9,

10,

11,

12]. They are thought to capture distinct phenotypic differences in tumors and a quantitatively assess intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity [

16,

17]. Recent radiomic feature analyses in prostate cancer research have assessed their ability to differentiate low from higher-grade prostate cancer [

18,

19,

20], predict Gleason Grades [

21,

22], and identify tumor presence [

16,

17,

23]. Radiomic feature calculations are highly sensitive to variations in image acquisition and often sacrifice interpretability of these mathematical representations of image characteristics; however, if properly used as input to machine and deep learning models, they can non-invasively identify relationships and potential biomarkers of a myriad of diseases.

While PI-RADS and Grade Groups are the two current gold standard metrics in assessing prostate cancer severity and risk, both scores are assigned qualitatively and are subjected to interrater variability, which can lead to overtreatment of low-risk cancers [

9,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. With the promising applications of radiomic features in assessing prostate cancer, this study sought to determine whether quantitative radiomic features of prostate cancer MRI differ not only between regions of cancer and noncancer on T2-weighted imaging, but if these features could predict cancer severity and metastatic risk. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that a radiomic feature-based model could be utilized as a non-invasive screening tool for prostate cancer presence and risk, detecting tumoral regions and biochemical recurrence risk. Additionally, we sought to determine if these features could be applied to a simulated low-resolution “quick” MRI that could be clinically practiced for routine patient care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Data Acquisition

Data from 279 prospectively recruited patients with biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy between 2014 and 2023 were analyzed for this institutional review board (IRB) approved study. Patients underwent multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging (MP-MRI) prior to surgery on a 3T MRI scanner (General Electric, Waukesha, WI, USA or Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with or without an endorectal coil. Each protocol included T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), dynamic contrast enhanced imaging (DCE), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), though this study focused on T2WI, which were normalized using the z-score of intensity within the mask of the prostate. The following are example T2W acquisition parameters: repetition time = 4500 ms; 512x512 voxel acquisition matrix; 120 mm field of view (FOV); 3 mm slice thickness; 0.234 x 0.234 mm voxel dimensions; 30 slices/acquisition (range 16 – 44).

Following prostatectomy, patients were monitored with prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing according to standard of care practices (mean 2.1 years, range 0.1 – 7.3 years). Patients with a measured PSA score of ≥ 0.2 ng/mL at any timepoint following surgery were considered biochemically recurrent [

29,

30]. Inclusion criteria for this study included T2-weighted imaging and at least one post-surgery PSA test. A subset of 109 patients with digitized and pathologist-provided Gleason pattern annotated histology were used to assess radiomic features of cancerous and non-cancerous regions on the MRI. Patient demographic information and clinical features for the whole study cohort are summarized in

Table 1, and the subset cohort in

Supplemental Table S1.

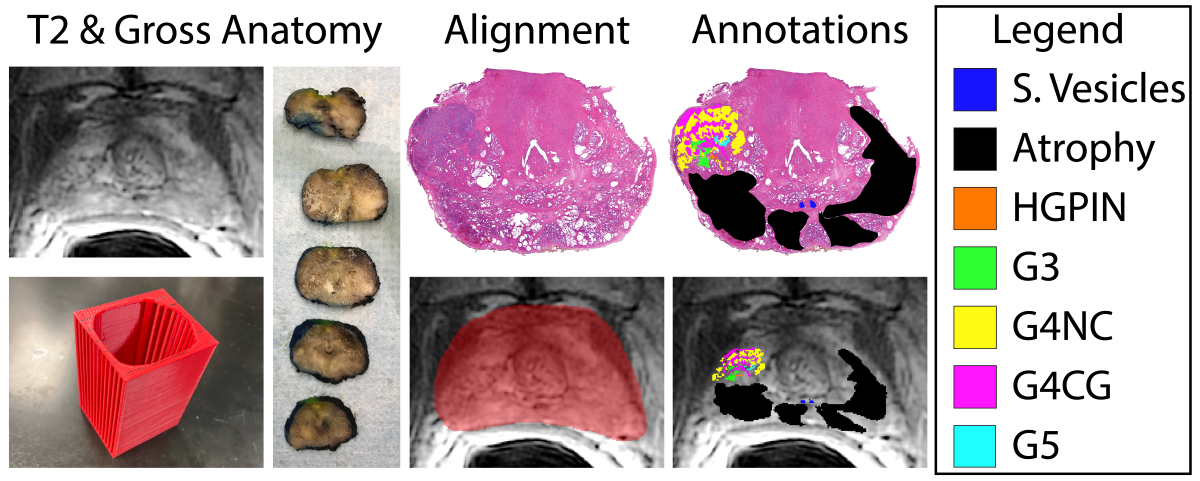

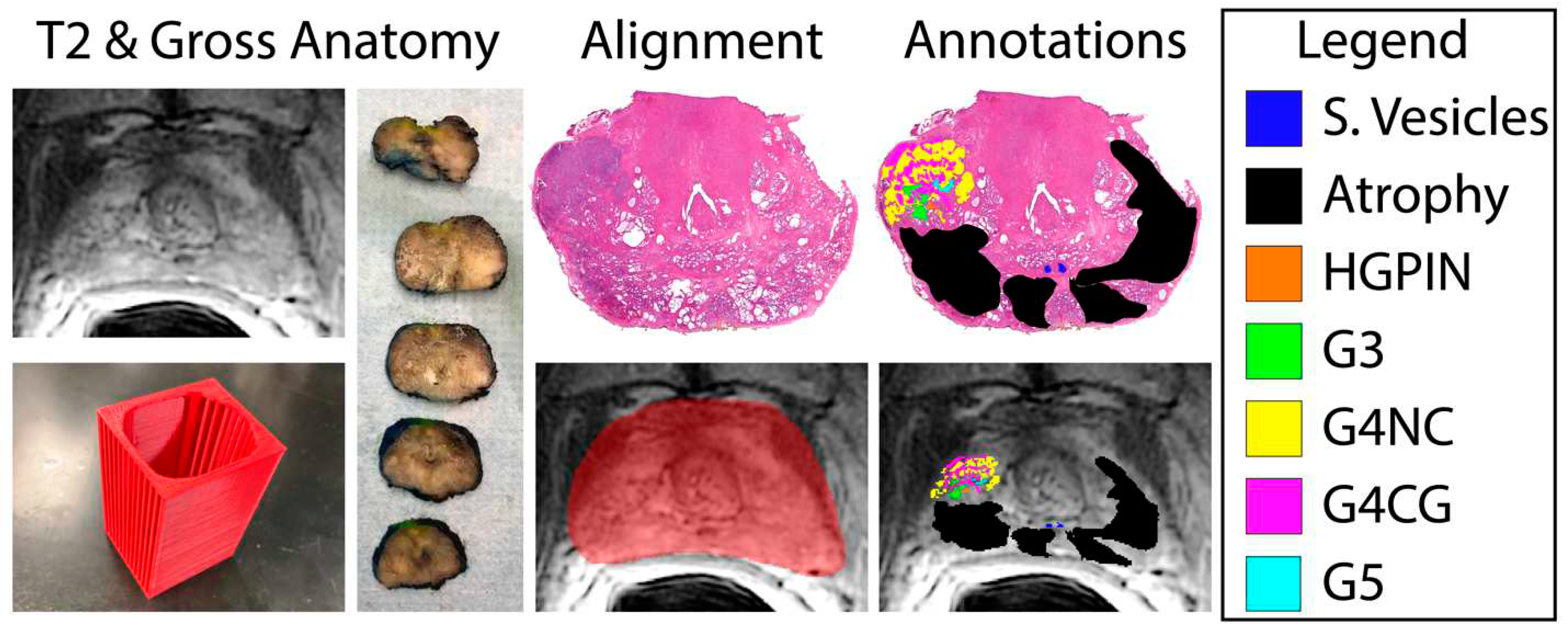

2.2. Histological Analysis

Prostatectomy was performed following imaging using the da Vinci robotic system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) [

31,

32]. Prior to 2020, prostatectomy occurred approximately 4 weeks after imaging; however, since the COVID-19 pandemic, the time between imaging and surgery increased to approximately 19 weeks. Prostate samples were formalin fixed overnight and sectioned using a custom, 3D printed slicing jig modeled after the orientation and slice thickness of the T2WI [

33]. Briefly, prostate masks were manually drawn using AFNI (Analysis of Functional NeuroImages,

http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/) [

34], 3D modeled using 3dSlicer (

https://slicer.org), and imported into Blender 2.75 (

https://www.blender.org/) to create the final slicing jig [

27,

35,

36,

37], and finally 3D printed using a fifth-generation Makerbot (Makerbot Industries, Brooklyn, NY, USA) (

Figure 1, left).

Whole-mount tissue sections were paraffin-embedded, axially sectioned, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained in our histology core lab. Stained slides were digitally scanned at 40x magnification using either a Nikon (Nikon Metrology, Brighton, MI, USA), Olympus (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or Huron (Huron Digital Pathology, Ontario, Canada) sliding stage microscopes at resolutions of 0.8, 0.34 or 0.2 microns per pixel, respectively. Multiple slide scanners were used due to upgrading equipment throughout the evolution of our lab. Slides were down sampled by a factor of 8 for the Nikon or Olympus scanners or 10 or Huron slide scanner, to account for the large file size of the raw, scanned slides and the increased resolution of the Huron scanned images. Scanned slides were annotated by a board-certified genitourinary pathologist to identify regions of unique Gleason patterns, including Gleason 3 (G3), G4 non-cribriform glands (G4NC), G4 cribriform (to papillary) glands (G4CG), and Gleason 5 (G5), as well as non-cancerous regions including seminal vesicles, atrophy, and high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN). Gleason 4 patterns were separately annotated due to their prognostic differences [

26,

38,

39,

40,

41]; however, all cancerous annotations were combined into one class for these analyses. An example of these annotations can be found in

Figure 1.

2.3. Histology & MRI Co-Registration

Digitized whole-slide images, as well as their respective annotation masks, were co-registered to the T2-weighted image using previously published software and techniques [

27,

33,

35,

36,

37,

42,

43,

44] (n = 3 slides/patient). Briefly, slides were flipped and rotated to match their respective MRI slice, and a control-point co-registration was applied using manually fixed points corresponding to their respective position between both modalities. Specifically, points were arranged along the boundaries of and on distinct landmarks within the prostate (i.e., the urethra, seminal vesicles, etc.). Approximately 20 – 30 control points were placed on each slide, which was then down-sampled to MRI resolution. A nonlinear, spatial transform was calculated from control points using Matlab’s (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA)

fitgeotrans function and applied using the

imwarp function. A local weighted-means transform was used to bring the histology slides into MRI space to account for non-uniform distortions, and an additional nearest-neighbor interpolation was applied on annotations to retain integer values (

Figure 1, right).

2.4. Radiomic Feature Extraction & Statistical Analyses

Radiomic features were extracted using Pyradiomics v3.1.0 [

45] in Visual Studio Code v1.79, including 14 shape features, 18 first order features, and 75 higher-order features. These features were extracted first across the whole prostate within the prostate mask and then again for cancerous and noncancerous regions of interest, delineated through our pathologist’s annotations and normalized using the training data’s Z-score for each feature. To prevent model overfitting, a t-test was performed to determine features that were significantly different between (1) patients who did and did not biochemically recur and (2) within regions of cancer and noncancer, and these features were used for model input parameters.

Both patient cohorts were divided using a 2/3rd – 1/3rd train/test split, balancing for Gleason Grade and biochemical recurrence. Two fine tree models, which allows for greater splits and thus fine distinctions between classes, were trained using Matlab 2021b with a 5-fold cross-validation to (1) predict patients who will experience eventual biochemical recurrence and (2) classify regions of cancer from noncancer. Models were evaluated on the withheld validation set and test set using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC AUC) curve for the BCR regression model and accuracy of the cancer/noncancer classification model.

3. Results

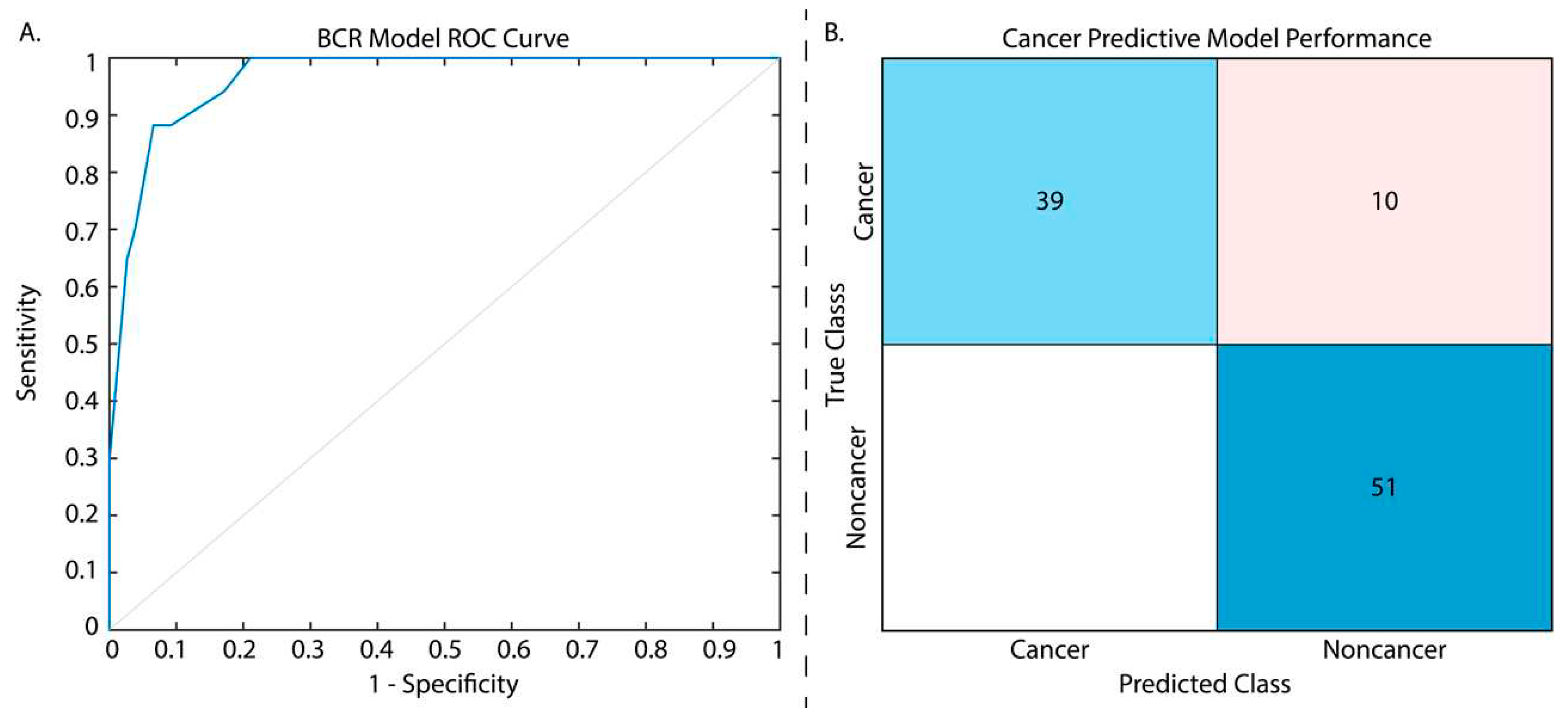

3.1. Biochemical Recurrence Regression Model

From our t-test analysis, of the initial 107 calculated radiomic features only 7 first order features were found to be significantly different between patients who did and did not experience eventual BCR (p < 0.01) including the following: 90

th percentile, Interquartile Range, Mean, Mean Absolute Deviation, Robust Mean Absolute Deviation, Root Mean Squared, and Variance. An additional two first order features, Maximum and Range, and four higher order, gray level size zone (GLSZM) features (i.e., Size Zone NonUniformity Normalized, Small Area Emphasis, Small Area High Gray Level Emphasis, and Zone Entropy) saw trending significance (all p < 0.1). Of the latter features, only Zone Entropy aided in model performance, thus the remaining features were excluded from the final model. The final features used in this model are described in

Table 2, with the full assessment in

Supplemental Table S2, and parameters are detailed in

Supplemental Table S3. This regression model was trained on data from 186 patients, and when evaluated on the withheld test set of 93 patients had an AUC of 0.97 (

Figure 2, A.)

3.2. Cancer/Noncancer Classification Model

From our t-test analysis, only 13 features of the 107 were not found to be significantly different cancerous and noncancerous regions, thus we chose to use the same 10 features used for our regression analysis in this model to determine whether these features alone could determine BCR risk and cancer presence and prevent model overfitting. T-test results for radiomic features between cancer and noncancer can be found in

Supplemental Table S4 and classification model parameters in Table 3. The cancer classification model was assessed on the validation set during model training and again on the withheld test set (n = 74 patients), and had an accuracy of 90.7% and 89.9%, respectively (

Figure 2, B.).

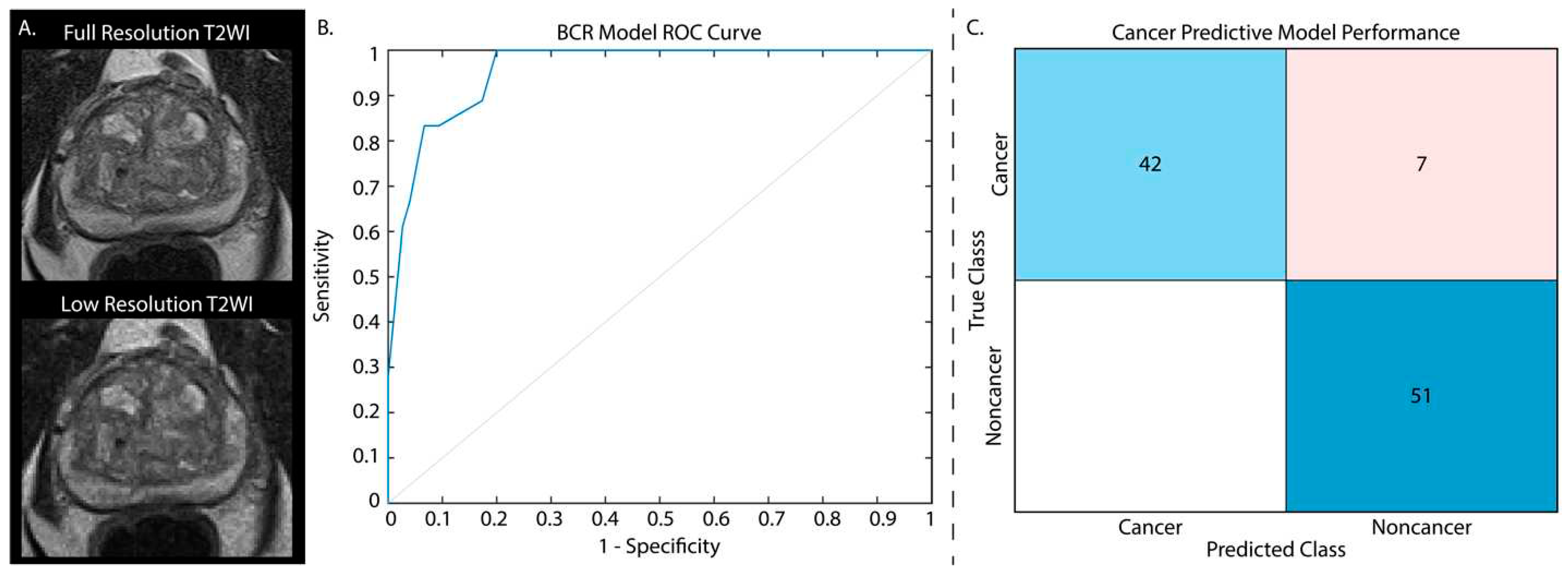

3.3. Low Resolution Image Assessment

As this models showed high performance at assessing cancer presence and BCR risk, we further assessed their capabilities on artificially noisy data as a proof of concept to determine if this model could applied to low-quality images that may be rapidly acquired as a prostate cacner screening tool. Briefly, simulated gaussian noise was added to the testing data with mean centered on 50 and a variance of 100, and furthermore downsampled by a factor of 2 (

Figure 3, A.). Whole prostate, cancer, and noncaner annotation masks were likewise downsampled to retain the same space on the low quality images and radiomic features were re-extracted. These features were normalized using the full resolution training data Z-score for each feature, and the same independent test sets that were used in the previous applications were again assessed. Applying the regression model to predict BCR yielded an AUC = 0.96 (

Figure 3, B.) and the classification model to the low-resolution test data yielded a test accuracy of 92.8%, highlighting the ability of these radiomic features at detecting cancer on poor quality images (

Figure 3, C.) and assessing BCR risk.

4. Discussion

Due to the significant rate of prostate cancer recurrence, there has been increasing interest in accurately and promptly predicting biochemical recurrence. This interest stems from the need to identify individuals who are at a high risk of experiencing adverse outcomes. Although the likelihood of BCR is dependent on the extent and aggressiveness of the cancer, roughly 20 percent to 30 percent of men will relapse within five years post-treatment [

46,

47]. These trends were observed in our cohort, where 16% of patients experienced BCR despite an average follow-up time of 2 years. Currently, the current gold standard prognostic indicator of BCR is defined by Gleason Grade Groups and measured by increased PSA, which is monitored post-radical prostatectomy [

48,

49,

50]. Non-invasive metrics to predict prostate cancer BCR risk are not widely researched, and may hinder patient treatment and follow-up following surgery.

This study showed that the use of quantitative radiomic features calculated from T2-weighted MR imaging has the potential to offer supplementary information beyond the conventional pathological evaluation. Specifically, we show that a tree regression model using nine first-order and one higher-order radiomic feature calculated and averaged across the whole prostate can predict BCR with an accuracy of 97%. We additionally, we found that these same features when used as input to a tree classificaiton model can accurately identify regions of cancer from noncancer on T2WI alone. The quantitative characteristics extracted from prostate cancer MR imaging have the potential to assist clinicians in predicting a patient's likelihood of biochemical recurrence, surpassing the insights gained from a qualitative analysis of gland morphology, as used in the Gleason grading scale. This was especially noted when using imaging that was downsampled and with additional simulated noise. Using our models on radiomic features calculated across these low resolution images provided high accuracy at both determining cancer presence and assigning metastatic potential. These results on low-resolution images highlight the feasibility of using these models as a noninvasive prostate cancer screening tool, similar in nature to a woman’s annual mammogram. A screening tool for prostate cancer may detect prostate cancer before it has progressed to a stage requiring surgical intervention.

Previous studies have explored the use of radiomic feature-based models in predicting prostate cancer [

51,

52,

53]. These models leverage the quantitative analysis of radiographic images to extract a wide range of features, such as shape, texture, and intensity, which can provide valuable insights into tumor characteristics. By incorporating these radiomic features into predictive models, researchers have aimed to enhance the accuracy and precision of prostate cancer diagnosis, risk stratification, and prognosis prediction. Previous studies showed 64 percent to 82 percent accuracy at annotated Gleason patterns using radiomic features calculated from T2WI and ADC maps [

21,

54]. Additionally, previous studies utilizing radiomic features to predict BCR showed similar success [

55,

56]. These models have shown promising results, demonstrating their potential as non-invasive tools for assessing cancer aggressiveness, treatment response, and patient outcomes.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that radiomic features of prostate cancer can predict eventual biochemical recurrence and tumor presence. Of the 107 total radiomic features calcualted, we found seven first-order features that significantly differed between patients who did and did not recurrence following radical prostatectomy, and an additional 3 features with marginal signficance that improved our model’s accuracy. While most radiomic features were significantly different between regions of cancer and noncancer, we found that the utilization of the aforementioned features could reliably identify cancerous lesions. These findings suggest that the variation in MRI-based features may be correlated with the aggressiveness and prognosis of prostate cancer.

4.1. Limitations

Although the findings of this study are propitious, it is essential to acknowlege several limitations. In comparision to previous studies on prostate cancer, this study utilizes a relatively small patient cohort. As a result, employing a larger cohort of patients may reveal additional radiomic characteristics. Additionally, though this was a single-center study, only clinical imaging was examined; therefore, there was a lack of standardization in acquisition parameters. This may confound future studies using imaging from additional MR vendors. Future studies should compare radiomic features calculated from other clinical MR vendors and imaging sequences to more precisely model BCR risk. Furthermore, only mean whole-prostate and lesion-wise radiomic featuers were investigated in our models; thus, future studies should examine voxel-wise or larger tile-based radiomic features. Finally, pathologist-provided cancer annotations were used as ground truth for the cancerous region model, which may not best inform on a radiologist’s delination of cancer on MR imaging. Future studies should additionally assess radiomic features based on radiologist-annotated tumoral regions.

5. Conclusion

We demonstrate that in a cohort of 279 patients with biopsy-confirmed prostate cancer, radiomic features were able to predict eventual biochemical recurrence. Additionally, in a subset of 109 patients, these same radiomic features were able to classify regions of cancer from noncancer at the whole-lesion level. These features may be quickly extracted from patient’s T2-weighted MR images to determine whether cancer is present and aid in patient monitoring after treatment. Future studies should assess these features in larger patient cohorts to further develop predictive models and determine if higher-grade cancers can be further circumscribed in prostate MRI.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Savannah Duenweg and Peter LaViolette; Data curation, Stephanie Vincent-Sheldon and Peter LaViolette; Formal analysis, Savannah Duenweg and Peter LaViolette; Funding acquisition, Peter LaViolette; Investigation, Peter LaViolette; Methodology, Kenneth Iczkowski, Kenneth Jacobsohn and Peter LaViolette; Project administration, Peter LaViolette; Resources, Peter LaViolette; Software, Savannah Duenweg, Samuel Bobholz, Michael Barrett, Allison Lowman, Aleksandra Winiarz, Biprojit Nath, Margaret Stebbins and John Bukowy; Supervision, Peter LaViolette; Validation, Savannah Duenweg, Samuel Bobholz, Michael Barrett, Allison Lowman, Aleksandra Winiarz, Biprojit Nath, Margaret Stebbins, John Bukowy and Peter LaViolette; Visualization, Savannah Duenweg; Writing – original draft, Savannah Duenweg; Writing – review & editing, Savannah Duenweg, Samuel Bobholz, Allison Lowman, Aleksandra Winiarz, Biprojit Nath, Margaret Stebbins, John Bukowy, Kenneth Iczkowski, Stephanie Vincent-Sheldon and Peter LaViolette.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH/NCI R01CA218144, R21CA231892, R01CA249882, and the State of Wisconsin Tax Check Off Program for Prostate Cancer Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of MEDICAL COLLEGE OF WISCONSIN (PRO00022426, 19 September 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our patients for their participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro, A.; Esposito, A.I.; Gallina, A.; Nees, M.; Angelini, G.; Albini, A.; Pfeffer, U. Validation of proposed prostate cancer biomarkers with gene expression data: A long road to travel. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2014, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, M.C.; Li, J.; Klink, J.C.; Kattan, M.W.; Klein, E.A.; Stephenson, A.J. Optimal definition of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy depends on pathologic risk factors: Identifying candidates for early salvage therapy. European Urology 2014, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokoll, L.J.; Zhang, Z.; Chan, D.W.; Reese, A.C.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Partin, A.W.; Walsh, P.C. Do Ultrasensitive Prostate Specific Antigen Measurements Have a Role in Predicting Long-Term Biochemical Recurrence-Free Survival in Men after Radical Prostatectomy? Journal of Urology 2016, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrock, T.; Somford, D.M.; Huisman, H.J.; van Oort, I.M.; Witjes, J.A.; Hulsbergen-van de Kaa, C.A.; Scheenen, T.; Barentsz, J.O. Relationship between Apparent Diffusion Coefficients at 3.0-T MR Imaging and Gleason Grade in Peripheral Zone Prostate Cancer. Radiology 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, E.K.; Kobus, T.; Litjens, G.J.S.; Hambrock, T.; Hulsbergen-Van De Kaa, C.A.; Barentsz, J.O.; Maas, M.C.; Scheenen, T.W.J. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Discriminating Low-Grade from High-Grade Prostate Cancer. Investigative Radiology 2015, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichtmann, B.D.; Zöllner, F.G.; Attenberger, U.I.; Schönberg, S.O. Multiparametric MRI in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer: Physical Foundations, Limitations, and Prospective Advances of Diffusion-Weighted MRI. Rofo 2021, 193, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barentsz, J.O.; Richenberg, J.; Clements, R.; Choyke, P.; Verma, S.; Villeirs, G.; Rouviere, O.; Logager, V.; Fütterer, J.J.; Radiology, E.S.o.U. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol 2012, 22, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohestani, K.; Wallström, J.; Dehlfors, N.; Sponga, O.M.; Månsson, M.; Josefsson, A.; Carlsson, S.; Hellström, M.; Hugosson, J. Performance and inter-observer variability of prostate MRI (PI-RADS version 2) outside high-volume centres. Scand J Urol 2019, 53, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, H.A.; Hötker, A.M.; Goldman, D.A.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Gondo, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Ehdaie, B.; Woo, S.; Fine, S.W.; Reuter, V.E.; et al. Updated prostate imaging reporting and data system (PIRADS v2) recommendations for the detection of clinically significant prostate cancer using multiparametric MRI: critical evaluation using whole-mount pathology as standard of reference. European Radiology 2016, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, J.C.; Barentsz, J.O.; Choyke, P.L.; Cornud, F.; Haider, M.A.; Macura, K.J.; Margolis, D.; Schnall, M.D.; Shtern, F.; Tempany, C.M.; et al. PI-RADS Prostate Imaging - Reporting and Data System: 2015, Version 2. Eur Urol 2016, 69, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergaglio, C.; Giasotto, V.; Marcenaro, M.; Barra, S.; Turazzi, M.; Bauckneht, M.; Casaleggio, A.; Sciabà, F.; Terrone, C.; Mantica, G.; et al. The Role of mpMRI in the Assessment of Prostate Cancer Recurrence Using the PI-RR System: Diagnostic Accuracy and Interobserver Agreement in Readers with Different Expertise. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaur, S.; Turkbey, B. Prostate MR Imaging for Posttreatment Evaluation and Recurrence. Radiol Clin North Am 2018, 56, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manceau, C.; Beauval, J.B.; Lesourd, M.; Almeras, C.; Aziza, R.; Gautier, J.R.; Loison, G.; Salin, A.; Tollon, C.; Soulié, M.; et al. MRI Characteristics Accurately Predict Biochemical Recurrence after Radical Prostatectomy. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.I.; Zelefsky, M.J.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Nelson, J.B.; Egevad, L.; Magi-Galluzzi, C.; Vickers, A.J.; Parwani, A.V.; Reuter, V.E.; Fine, S.W.; et al. A Contemporary Prostate Cancer Grading System: A Validated Alternative to the Gleason Score. European Urology 2016, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgadillo, R.; Ford, J.C.; Abramowitz, M.C.; Dal Pra, A.; Pollack, A.; Stoyanova, R. The role of radiomics in prostate cancer radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 2020, 196, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, R.; Takhar, M.; Tschudi, Y.; Ford, J.C.; Solórzano, G.; Erho, N.; Balagurunathan, Y.; Punnen, S.; Davicioni, E.; Gillies, R.J.; et al. Prostate cancer radiomics and the promise of radiogenomics. Transl Cancer Res 2016, 5, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuocolo, R.; Stanzione, A.; Ponsiglione, A.; Romeo, V.; Verde, F.; Creta, M.; La Rocca, R.; Longo, N.; Pace, L.; Imbriaco, M. Clinically significant prostate cancer detection on MRI: A radiomic shape features study. Eur J Radiol 2019, 116, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merisaari, H.; Taimen, P.; Shiradkar, R.; Ettala, O.; Pesola, M.; Saunavaara, J.; Boström, P.J.; Madabhushi, A.; Aronen, H.J.; Jambor, I. Repeatability of radiomics and machine learning for DWI: Short-term repeatability study of 112 patients with prostate cancer. Magn Reson Med 2020, 83, 2293–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, B.; Chen, F.; Hwang, D.; Palmer, S.L.; De Castro Abreu, A.L.; Ukimura, O.; Aron, M.; Gill, I.; Duddalwar, V.; Pandey, G. Objective risk stratification of prostate cancer using machine learning and radiomics applied to multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, A.; Kucharczyk, M.J.; Niazi, T. Multimodal Radiomic Features for the Predicting Gleason Score of Prostate Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaddad, A.; Niazi, T.; Probst, S.; Bladou, F.; Anidjar, M.; Bahoric, B. Predicting Gleason Score of Prostate Cancer Patients Using Radiomic Analysis. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; He, Z.; Ouyang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Y.; Mao, L.; Ren, W.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging radiomics predicts preoperative axillary lymph node metastasis to support surgical decisions and is associated with tumor microenvironment in invasive breast cancer: A machine learning, multicenter study. EBioMedicine 2021, 69, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, B.G.; Shih, J.H.; Sankineni, S.; Marko, J.; Rais-Bahrami, S.; George, A.K.; de la Rosette, J.J.; Merino, M.J.; Wood, B.J.; Pinto, P.; et al. Prostate Cancer: Interobserver Agreement and Accuracy with the Revised Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System at Multiparametric MR Imaging. Radiology 2015, 277, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphalen, A.C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Anaokar, J.M.; Arora, S.; Barashi, N.S.; Barentsz, J.O.; Bathala, T.K.; Bittencourt, L.K.; Booker, M.T.; Braxton, V.G.; et al. Variability of the Positive Predictive Value of PI-RADS for Prostate MRI across 26 Centers: Experience of the Society of Abdominal Radiology Prostate Cancer Disease-focused Panel. Radiology 2020, 296, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Slot, M.A.; Hollemans, E.; den Bakker, M.A.; Hoedemaeker, R.; Kliffen, M.; Budel, L.M.; Goemaere, N.N.T.; van Leenders, G.J.L.H. Inter-observer variability of cribriform architecture and percent Gleason pattern 4 in prostate cancer: relation to clinical outcome. Virchows Archiv 2021, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, S.D.; Bukowy, J.D.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Lowman, A.K.; Brehler, M.; Bobholz, S.; Nencka, A.; Barrington, A.; Jacobsohn, K.; Unteriner, J.; et al. Radio-pathomic mapping model generated using annotations from five pathologists reliably distinguishes high-grade prostate cancer. Journal of Medical Imaging 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, M.K.K.; Parwani, A.V.; Gurcan, M.N. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, e253–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Urological, A. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) best practice policy. American Urological Association (AUA). Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 2000, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, G.P.; Chen, W.; Trevathan, S.; Hermans, M. Long-Term Follow-Up after Prostatectomy for Prostate Cancer and the Need for Active Monitoring. Prostate Cancer 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Jeong, W.; Peabody, J.O.; Hemal, A.K.; Menon, M. Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Inching Toward Gold Standard. In Urologic Clinics of North America; 2014; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, M.; Hemal, A.K. Vattikuti Institute prostatectomy: A technique of robotic radical prostatectomy: Experience in more than 1000 cases. Journal of Endourology 2004, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.; Pohida, T.; Turkbey, B.; Mani, H.; Merino, M.; Pinto, P.A.; Choyke, P.; Bernardo, M. A method for correlating in vivo prostate magnetic resonance imaging and histopathology using individualized magnetic resonance -based molds. Review of Scientific Instruments 2009, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.W. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical Research 1996, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurrell, S.L.; McGarry, S.D.; Kaczmarowski, A.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Jacobsohn, K.; Hohenwalter, M.D.; Hall, W.A.; See, W.A.; Banerjee, A.; Charles, D.K.; et al. Optimized b-value selection for the discrimination of prostate cancer grades, including the cribriform pattern, using diffusion weighted imaging. Journal of Medical Imaging 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, S.D.; Hurrell, S.L.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Hall, W.; Kaczmarowski, A.L.; Banerjee, A.; Keuter, T.; Jacobsohn, K.; Bukowy, J.D.; Nevalainen, M.T.; et al. Radio-pathomic Maps of Epithelium and Lumen Density Predict the Location of High-Grade Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 2018, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, S.D.; Bukowy, J.D.; Iczkowski, K.A.; Unteriner, J.G.; Duvnjak, P.; Lowman, A.K.; Jacobsohn, K.; Hohenwalter, M.; Griffin, M.O.; Barrington, A.W.; et al. Gleason probability maps: A radiomics tool for mapping prostate cancer likelihood in mri space. Tomography 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iczkowski, K.A.; Torkko, K.C.; Kotnis, G.R.; Wilson, R.S.; Huang, W.; Wheeler, T.M.; Abeyta, A.M.; La Rosa, F.G.; Cook, S.; Werahera, P.N.; et al. Digital quantification of five high-grade prostate cancer patterns, including the cribriform pattern, and their association with adverse outcome. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2011, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iczkowski, K.A.; Paner, G.P.; Van der Kwast, T. The New Realization About Cribriform Prostate Cancer. Adv Anat Pathol 2018, 25, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweldam, C.F.; Wildhagen, M.F.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Bangma, C.H.; Van Der Kwast, T.H.; Van Leenders, G.J.L.H. Cribriform growth is highly predictive for postoperative metastasis and disease-specific death in Gleason score 7 prostate cancer. Modern Pathology 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montironi, R.; Cimadamore, A.; Gasparrini, S.; Mazzucchelli, R.; Santoni, M.; Massari, F.; Cheng, L.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Scarpelli, M. Prostate cancer with cribriform morphology: diagnosis, aggressiveness, molecular pathology and possible relationships with intraductal carcinoma. In Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy; 2018; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Bobholz, S.A.; Lowman, A.K.; Barrington, A.; Brehler, M.; McGarry, S.; Cochran, E.J.; Connelly, J.; Mueller, W.M.; Agarwal, M.; O'Neill, D.; et al. Radiomic Features of Multiparametric MRI Present Stable Associations with Analogous Histological Features in Patients with Brain Cancer. Tomography 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, S.D.; Hurrell, S.L.; Kaczmarowski, A.L.; Cochran, E.J.; Connelly, J.; Rand, S.D.; Schmainda, K.M.; LaViolette, P.S. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Based Radiomic Profiles Predict Patient Prognosis in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Before Therapy. Tomography 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, S.D.; Brehler, M.; Bukowy, J.D.; Lowman, A.K.; Bobholz, S.A.; Duenweg, S.R.; Banerjee, A.; Hurrell, S.L.; Malyarenko, D.; Chenevert, T.L.; et al. Multi-Site Concordance of Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Quantification for Assessing Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, M.S.; Aus, G.; Burnett, A.L.; Canby-Hagino, E.D.; D'Amico, A.V.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Eton, D.T.; Forman, J.D.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Hernandez, J.; et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: the American Urological Association Prostate Guidelines for Localized Prostate Cancer Update Panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. J Urol 2007, 177, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, A.; Bastian, P.J.; Bellmunt, J.; Bolla, M.; Joniau, S.; van der Kwast, T.; Mason, M.; Matveev, V.; Wiegel, T.; Zattoni, F.; et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2014, 65, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amling, C.L.; Blute, M.L.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Seay, T.M.; Slezak, J.; Zincke, H. Long-term hazard of progression after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: Continued risk of biochemical failure after 5 years. Journal of Urology 2000, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockman, J.A.; Alanee, S.; Vickers, A.J.; Scardino, P.T.; Wood, D.P.; Kibel, A.S.; Lin, D.W.; Bianco, F.J.; Rabah, D.M.; Klein, E.A.; et al. Nomogram predicting prostate cancer-specific mortality for men with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. European Urology 2015, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, T.A.; Eruyar, A.T.; Cebeci, O.O.; Memik, O.; Ozcan, L.; Kuskonmaz, I. Interobserver variability in Gleason histological grading of prostate cancer. Scandinavian Journal of Urology 2016, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algohary, A.; Viswanath, S.; Shiradkar, R.; Ghose, S.; Pahwa, S.; Moses, D.; Jambor, I.; Shnier, R.; Böhm, M.; Haynes, A.M.; et al. Radiomic features on MRI enable risk categorization of prostate cancer patients on active surveillance: Preliminary findings. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, F.; Anceschi, U.; Cordelli, E.; Faiella, E.; Civitella, A.; Tuzzolo, P.; Iannuzzi, A.; Ragusa, A.; Esperto, F.; Prata, S.M.; et al. Radiomic Machine-Learning Analysis of Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer: New Combination of Textural and Clinical Features. Curr Oncol 2023, 30, 2021–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Schabath, M.B. Radiomics Improves Cancer Screening and Early Detection. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2020, 29, 2556–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, C.; Wei, X.; Bao, J.; Ji, X.; Bai, H.; Xia, W.; Gao, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. MRI-based radiomics models to assess prostate cancer, extracapsular extension and positive surgical margins. Cancer Imaging 2021, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algohary, A.; Shiradkar, R.; Pahwa, S.; Purysko, A.; Verma, S.; Moses, D.; Shnier, R.; Haynes, A.M.; Delprado, W.; Thompson, J.; et al. Combination of Peri-Tumoral and Intra-Tumoral Radiomic Features on Bi-Parametric MRI Accurately Stratifies Prostate Cancer Risk: A Multi-Site Study. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiradkar, R.; Ghose, S.; Jambor, I.; Taimen, P.; Ettala, O.; Purysko, A.S.; Madabhushi, A. Radiomic features from pretreatment biparametric MRI predict prostate cancer biochemical recurrence: Preliminary findings. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018, 48, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).