Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

03 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Ezrin, Radixin, Moesin (ERM) Family of Proteins

3. Moesin in mast cells

4. SNAREs and SNAPs

5. Neuroinflammation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Dileepan, K.N.; Wood, J.G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parwaresch, M.; Homy, H.-P.; Lennert, K. Tissue mast cells in health and disease. Pathol. - Res. Pr. 1985, 179, 439–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csaba, G. Mast cell, the peculiar member of the immune system: A homeostatic aspect. Acta Microbiol. et Immunol. Hung. 2015, 62, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebenhaar, F.; Redegeld, F.A.; Bischoff, S.C.; Gibbs, B.F.; Maurer, M. Mast Cells as Drivers of Disease and Therapeutic Targets. Trends Immunol. 2017, 39, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.; Looareesuwan, S.; White, N.; Silamut, K.; Kietinun, S.; Warrell, D. Quinine pharmacokinetics and toxicity in pregnant and lactating women with falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1986, 21, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falduto, G.H.; Pfeiffer, A.; Luker, A.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Olivera, A. Emerging mechanisms contributing to mast cell-mediated pathophysiology with therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 220, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlin, J.S.; Maurer, M.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Pejler, G.; Sagi-Eisenberg, R.; Nilsson, G. The ingenious mast cell: Contemporary insights into mast cell behavior and function. Allergy 2021, 77, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolkhir, P.; Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Metz, M.; Siebenhaar, F.; Maurer, M. Understanding human mast cells: lesson from therapies for allergic and non-allergic diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 22, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Schaffer, F.; Gibbs, B.F.; Hallgren, J.; Pucillo, C.; Redegeld, F.; Siebenhaar, F.; Vitte, J.; Mezouar, S.; Michel, M.; Puzzovio, P.G.; et al. Selected recent advances in understanding the role of human mast cells in health and disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A.; Beaven, M.A.; Metcalfe, D.D. Mast cells signal their importance in health and disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibilano, R.; Frossi, B.; Pucillo, C.E. Mast cell activation: A complex interplay of positive and negative signaling pathways. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 2558–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Gallenga, C.; Pandolfi, F.; Caraffa, A.; Kritas, S.K.; Ronconi, G.; Toniato, E.; Martinotti, S.; Conti, P. Interleukin-1 family cytokines and mast cells: activation and inhibition. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. agents 2019, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, S.J.; Tsai, M.; Piliponsky, A.M. The development of allergic inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toniato, E.; Frydas, I.; Robuffo, I.; Ronconi, G.; Caraffa, A.; Kritas, S.K.; Conti, P. Activation and inhibition of adaptive immune response mediated by mast cells. . 2017, 31, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avila, M.; Gonzalez-Espinosa, C. Signaling through Toll-like receptor 4 and mast cell-dependent innate immunity responses. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, P. Microbes taming mast cells: Implications for allergic inflammation and beyond. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 778, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll-Portillo, A.; Cannon, J.L.; Riet, J.T.; Holmes, A.; Kawakami, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Cambi, A.; Lidke, D.S. Mast cells and dendritic cells form synapses that facilitate antigen transfer for T cell activation. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 210, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Weng, Z.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Asadi, S.; Therianou, A.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Angelidou, A.; Shirihai, O.; Theoharides, T.C. Mitochondria Distinguish Granule-Stored from de novo Synthesized Tumor Necrosis Factor Secretion in Human Mast Cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 159, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Mascarenhas, J.; Hoffman, R.; Dai, Y.; Wisch, N.; Xu, M. Pivotal role of mast cells in pruritogenesis in patients with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood 2009, 113, 5942–5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekori, Y.A.; Hershko, A.Y.; Frossi, B.; Mion, F.; Pucillo, C.E. Integrating innate and adaptive immune cells: Mast cells as crossroads between regulatory and effector B and T cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 778, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christy, A.L.; Brown, M.A. The Multitasking Mast Cell: Positive and Negative Roles in the Progression of Autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 2673–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim-Rad K, Metz M, Maurer M. Mast cells: makers and breakers of allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009, 9, 427–430.

- Theoharides TC, Alysandratos KD, Angelidou A, Delivanis DA, Sismanopoulos N, Zhang B, Asadi S, Vasiadi M, Weng Z, Miniati A, Kalogeromitros D. Mast cells and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1822, 21–33.

- Kempuraj D, Ahmed ME, Selvakumar GP, Thangavel R, Dhaliwal AS, Dubova I, Mentor S, Premkumar K, Saeed D, Zahoor H, Raikwar SP, Zaheer S, Iyer SS, Zaheer A. Brain Injury-Mediated Neuroinflammatory Response and Alzheimer's Disease. Neuroscientist 2020, 26, 134–155.

- Mukai, K.; Tsai, M.; Saito, H.; Galli, S.J. Mast cells as sources of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 282, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides TC, Valent P, Akin C. Mast Cells, Mastocytosis, and Related Disorders. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 163–172.

- Theoharides, T.C. Atopic Conditions in Search of Pathogenesis and Therapy. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Leeman, S.E. Effect of IL-33 on de novo synthesized mediators from human mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, C. Mast cell activation disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014, 2, 252–257 e251; quiz 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides TC, Tsilioni I, Ren H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019, 15, 639–656.

- Galli, S.J.; Gaudenzio, N.; Tsai, M. Mast Cells in Inflammation and Disease: Recent Progress and Ongoing Concerns. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 49–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj D, Selvakumar GP, Ahmed ME, Raikwar SP, Thangavel R, Khan A, Zaheer SA, Iyer SS, Burton C, James D, Zaheer A. COVID-19, Mast Cells, Cytokine Storm, Psychological Stress, and Neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 2020, 1073858420941476.

- Kempuraj D, Mentor S, Thangavel R, Ahmed ME, Selvakumar GP, Raikwar SP, Dubova I, Zaheer S, Iyer SS, Zaheer A. Mast Cells in Stress, Pain, Blood-Brain Barrier, Neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2019, 13, 54. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.B.; Conti, P.D.; Economu, M.M. Brain Inflammation, Neuropsychiatric Disorders, and Immunoendocrine Effects of Luteolin. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 34, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj D, Selvakumar GP, Thangavel R, Ahmed ME, Zaheer S, Raikwar SP, Iyer SS, Bhagavan SM, Beladakere-Ramaswamy S, Zaheer A. Mast Cell Activation in Brain Injury, Stress, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 703. [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Zaheer, S.; Ahmed, M.E.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zahoor, H.; Saeed, D.; Natteru, P.A.; Iyer, S.; et al. Brain and Peripheral Atypical Inflammatory Mediators Potentiate Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, S.J.; Grimbaldeston, M.; Tsai, M. Immunomodulatory mast cells: negative, as well as positive, regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.E.; Hartmann, K.; Roers, A.; Krummel, M.F.; Locksley, R.M. Perivascular Mast Cells Dynamically Probe Cutaneous Blood Vessels to Capture Immunoglobulin E. Immunity 2013, 38, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, H.; Eglite, S.; Haleem-Smith, H.; Reischl, I.; Torigoe, C. Quantitative aspects of signal transduction by the receptor with high affinity for IgE. Mol. Immunol. 2002, 38, 1207–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Errico, D.; Lessmann, E.; Rivera, J. Adapters in the organization of mast cell signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 232, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando T, Kitaura J. Tuning IgE. IgE-Associating Molecules and Their Effects on IgE-Dependent Mast Cell Reactions. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nagata Y, Suzuki R. FcepsilonRI. A Master Regulator of Mast Cell Functions. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Taracanova, A.; Alevizos, M.; Karagkouni, A.; Weng, Z.; Norwitz, E.; Conti, P.; Leeman, S.E.; Theoharides, T.C. SP and IL-33 together markedly enhance TNF synthesis and secretion from human mast cells mediated by the interaction of their receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E4002–E4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, C.T.; Theoharides, T.C.; Konstantinidou, A.D. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and the blood-brain-barrier. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 1615–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandere-Grzybowska, K.; Letourneau, R.; Kempuraj, D.; Donelan, J.; Poplawski, S.; Boucher, W.; Athanassiou, A.; Theoharides, T.C. IL-1 Induces Vesicular Secretion of IL-6 without Degranulation from Human Mast Cells. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 4830–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.B. Mediators of human mast cells and human mast cell subsets. Ann. Allergy 1987, 58, 226–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wernersson, S.; Pejler, G. Mast cell secretory granules: armed for battle. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvnäs, B. Histamine storage and release. Fed. Proc. 1974, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, S.F.; Schwartz, L.B.; Maric, I.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Carter, M.C. Acute increases in total serum tryptase unassociated with hemodynamic instability in diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2022, 129, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kormelink, T.G.; Arkesteijn, G.J.A.; van de Lest, C.H.A.; Geerts, W.J.C.; Goerdayal, S.S.; Altelaar, M.A.F.; Redegeld, F.A.; Hoen, E.N.M.N.; Wauben, M.H.M. Mast Cell Degranulation Is Accompanied by the Release of a Selective Subset of Extracellular Vesicles That Contain Mast Cell–Specific Proteases. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 3382–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M.; Giavina-Bianchi, P.; Mezzano, V.; Castells, M. Expanding Spectrum of Mast Cell Activation Disorders: Monoclonal and Idiopathic Mast Cell Activation Syndromes. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Bondy, P.K.; Tsakalos, N.D.; Askenase, P.W. Differential release of serotonin and histamine from mast cells. Nature 1982, 297, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Cochrane, D.E. Critical role of mast cells in inflammatory diseases and the effect of acute stress. J. Neuroimmunol. 2004, 146, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solimando, A.G.; Desantis, V.; Ribatti, D. Mast Cells and Interleukins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taracanova A, Tsilioni I, Conti P, Norwitz ER, Leeman SE, Theoharides TC. Substance P and IL-33 administered together stimulate a marked secretion of IL-1beta from human mast cells, inhibited by methoxyluteolin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E9381–E9390.

- Gagari, E.; Tsai, M.; Lantz, C.S.; Fox, L.G.; Galli, S.J. Differential Release of Mast Cell Interleukin-6 Via c-kit. Blood 1997, 89, 2654–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petra, A.I.; Tsilioni, I.; Taracanova, A.; Katsarou-Katsari, A.; Theoharides, TC. Interleukin, 3. 3.; interleukin 4 regulate interleukin 31 gene expression secretion from human laboratory of allergic diseases 2 mast cells stimulated by substance, P.; /or immunoglobulin, E. Allergy Asthma Proc 2018, 39, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kalogeromitros, D. The Critical Role of Mast Cells in Allergy and Inflammation. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2006, 1088, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kempuraj, D.; Tagen, M.; Conti, P.; Kalogeromitros, D. Differential release of mast cell mediators and the pathogenesis of inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2007, 217, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Bin, N.-R.; Sugita, S. Diverse exocytic pathways for mast cell mediators. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilfillan, A.M.; Tkaczyk, C. Integrated signalling pathways for mast-cell activation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzio, N.; Sibilano, R.; Marichal, T.; Starkl, P.; Reber, L.L.; Cenac, N.; McNeil, B.D.; Dong, X.; Hernandez, J.D.; Sagi-Eisenberg, R.; et al. Different activation signals induce distinct mast cell degranulation strategies. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3981–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivellato, E.; Nico, B.; Gallo, V.P.; Ribatti, D. Cell Secretion Mediated by Granule-Associated Vesicle Transport: A Glimpse at Evolution. Anat. Rec. 2010, 293, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.C.; Befus, A.D.; Kulka, M. Mast Cell Mediators: Their Differential Release and the Secretory Pathways Involved. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 569–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukman, K.V.; Försönits, A.; Oszvald. ; Tóth, E.Á.; Buzás, E.I. Mast cell secretome: Soluble and vesicular components. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 67, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng Z, Zhang B, Tsilioni I, Theoharides TC. Nanotube Formation: A Rapid Form of "Alarm Signaling"? Clin Ther 2016, 38, 1066–1072. [CrossRef]

- Carroll-Portillo, A.; Surviladze, Z.; Cambi, A.; Lidke, D.S.; Wilson, B.S. Mast cell synapses and exosomes: membrane contacts for information exchange. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulia, R.; Gaudenzio, N.; Rodrigues, M.; Lopez, J.; Blanchard, N.; Valitutti, S.; Espinosa, E. Mast cells form antibody-dependent degranulatory synapse for dedicated secretion and defence. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, D.E.; Douglas, W.W. Calcium-Induced Extrusion of Secretory Granules (Exocytosis) in Mast Cells Exposed to 48/80 or the Ionophores A-23187 and X-537A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1974, 71, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Theoharides, T.C. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and extracellular mitochondria augment IgE-stimulated human mast-cell vascular endothelial growth factor release, which is inhibited by luteolin. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 85–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Douglas, W.W. Secretion in Mast Cells Induced by Calcium Entrapped Within Phospholipid Vesicles. Science 1978, 201, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, A.M. Piecemeal Degranulation of Basophils and Mast Cells Is Effected by Vesicular Transport of Stored Secretory Granule Contents. 2005, 85, 135–184. [CrossRef]

- Skokos, D.; Le Panse, S.; Villa, I.; Rousselle, J.-C.; Peronet, R.; David, B.; Namane, A.; Mécheri, S. Mast Cell-Dependent B and T Lymphocyte Activation Is Mediated by the Secretion of Immunologically Active Exosomes. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skokos, D.; Goubran-Botros, H.; Roa, M.; Mécheri, S. Erratum to “Immunoregulatory properties of mast cell-derived exosomes” [Molecular Immunology 38 (16–18) (2002) 1359–1362]. Mol. Immunol. 2003, 39, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefler, I.; Salamon, P.; Hershko, A.Y.; Mekori, Y.A. Mast Cells as Sources and Targets of Membrane Vesicles. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 3797–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecce M, Molfetta R, Milito ND, Santoni A, Paolini R. FcepsilonRI Signaling in the Modulation of Allergic Response: Role of Mast Cell-Derived Exosomes. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Shefler, I.; Salamon, P.; Mekori, Y.A. Extracellular Vesicles as Emerging Players in Intercellular Communication: Relevance in Mast Cell-Mediated Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phukan, P.; Barman, B.; Chengappa, N.K.; Lynser, D.; Paul, S.; Nune, A.; Sarma, K. Diffusion tensor imaging analysis of rheumatoid arthritis patients with neuropsychiatric features to determine the alteration of white matter integrity due to vascular events. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 41, 3169–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Zhang, B.; Kempuraj, D.; Tagen, M.; Vasiadi, M.; Angelidou, A.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Asadi, S.; Stavrianeas, N.; et al. IL-33 augments substance P-induced VEGF secretion from human mast cells and is increased in psoriatic skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4448–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristinziano, L.; Poto, R.; Criscuolo, G.; Ferrara, A.L.; Galdiero, M.R.; Modestino, L.; Loffredo, S.; de Paulis, A.; Marone, G.; Spadaro, G.; et al. IL-33 and Superantigenic Activation of Human Lung Mast Cells Induce the Release of Angiogenic and Lymphangiogenic Factors. Cells 2021, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti P, Caraffa A, Tete G, Gallenga CE, Ross R, Kritas SK, Frydas I, Younes A, Di Emidio P, Ronconi G. Mast cells activated by SARS-CoV-2 release histamine which increases IL-1 levels causing cytokine storm and inflammatory reaction in COVID-19. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2020, 34, 1629–1632.

- Kaur, D.; Gomez, E.; Doe, C.; Berair, R.; Woodman, L.; Saunders, R.; Hollins, F.; Rose, F.; Amrani, Y.; May, R.; et al. IL-33 drives airway hyper-responsiveness through IL-13-mediated mast cell: airway smooth muscle crosstalk. Allergy 2015, 70, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobío, A.; Bandara, G.; Morris, D.A.; Kim, D.; Connell, M.P.O.; Komarow, H.D.; Carter, M.C.; Smrz, D. Oncogenic D816V-KIT signaling in mast cells causes persistent IL-6 production. Haematologica 2020, 105, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Boucher, W.; Spear, K. Serum Interleukin-6 Reflects Disease Severity and Osteoporosis in Mastocytosis Patients. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2002, 128, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockow, K.; Akin, C.; Huber, M.; Metcalfe, D.D. IL-6 levels predict disease variant and extent of organ involvement in patients with mastocytosis. Clin. Immunol. 2005, 115, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayado, A.; Teodosio, C.; Garcia-Montero, A.C.; Matito, A.; Rodriguez-Caballero, A.; Morgado, J.M.; Muñiz, C.; Jara-Acevedo, M.; Álvarez-Twose, I.; Sanchez-Muñoz, L.; et al. Increased IL6 plasma levels in indolent systemic mastocytosis patients are associated with high risk of disease progression. Leukemia 2015, 30, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudeck, J.; Kotrba, J.; Immler, R.; Hoffmann, A.; Voss, M.; Alexaki, V.I.; Morton, L.; Jahn, S.R.; Katsoulis-Dimitriou, K.; Winzer, S.; et al. Directional mast cell degranulation of tumor necrosis factor into blood vessels primes neutrophil extravasation. Immunity 2021, 54, 468–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons DO, Pullen NA. Beyond IgE. Alternative Mast Cell Activation Across Different Disease States. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Franke K, Wang Z, Zuberbier T, Babina M. Cytokines Stimulated by IL-33 in Human Skin Mast Cells: Involvement of NF-kappaB and p38 at Distinct Levels and Potent Co-Operation with FcepsilonRI and MRGPRX2. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Babina M, Wang Z, Li Z, Franke K, Guhl S, Artuc M, Zuberbier T. FcepsilonRI- and MRGPRX2-evoked acute degranulation responses are fully additive in human skin mast cells. Allergy 2022, 77, 1906–1909.

- Asadi, S.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Angelidou, A.; Miniati, A.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Vasiadi, M.; Zhang, B.; Kalogeromitros, D.; Theoharides, T.C. Substance P (SP) Induces Expression of Functional Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor-1 (CRHR-1) in Human Mast Cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCary C, Tancowny BP, Catalli A, Grammer LC, Harris KE, Schleimer RP, Kulka M. Substance P downregulates expression of the high affinity IgE receptor (FcepsilonRI) by human mast cells. J Neuroimmunol 2010, 220, 17–24.

- Donelan, J.; Boucher, W.; Papadopoulou, N.; Lytinas, M.; Papaliodis, D.; Dobner, P.; Theoharides, T.C. Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces skin vascular permeability through a neurotensin-dependent process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 7759–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alysandratos, K.; Asadi, S.; Angelidou, A.; Zhang, B.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Yang, H.; Critchfield, A.; Theoharides, T.C. Neurotensin and CRH Interactions Augment Human Mast Cell Activation. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e48934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. Effect of Stress on Neuroimmune Processes. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C. The impact of psychological stress on mast cells. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2020, 125, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, F.R.; Wallerman, O.; Paivandy, A.; Calounova, G.; Gustafson, A.-M.; Sabari, B.R.; Zabucchi, G.; Allis, C.D.; Pejler, G. Tryptase-catalyzed core histone truncation: A novel epigenetic regulatory mechanism in mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, S.; Melo, F.R.; Pejler, G. Tryptase Regulates the Epigenetic Modification of Core Histones in Mast Cell Leukemia Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, S.; Leoni, C. Epigenetic and transcriptional control of mast cell responses. F1000Research 2017, 6, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, R.; Chelbi, R.; Agopian, J.; Letard, S.; Griffon, A.; Ghamlouch, H.; Vernerey, J.; Ladopoulos, V.; Voisset, E.; De Sepulveda, P.; et al. TET2 regulates immune tolerance in chronically activated mast cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Perlman, A.I.; Twahir, A.; Kempuraj, D. Mast cell activation: beyond histamine and tryptase. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, U.; Huang, H.; Kawakami, T. The high affinity IgE receptor: a signaling update. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 72, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Leung PSC, Gershwin ME, Song J. New Mechanistic Advances in FcepsilonRI-Mast Cell-Mediated Allergic Signaling. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2022, 63, 431–446.

- Babina, M.; Wang, Z.; Artuc, M.; Guhl, S.; Zuberbier, T. MRGPRX2 is negatively targeted by SCF and IL-4 to diminish pseudo-allergic stimulation of skin mast cells in culture. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Babina M. MRGPRX2 signals its importance in cutaneous mast cell biology: Does MRGPRX2 connect mast cells and atopic dermatitis? Exp Dermatol 2020, 29, 1104–1111.

- Ogasawara, H.; Noguchi, M. Therapeutic Potential of MRGPRX2 Inhibitors on Mast Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Li Z, Bal G, Franke K, Zuberbier T, Babina M. beta-arrestin-1 and beta-arrestin-2 Restrain MRGPRX2-Triggered Degranulation and ERK1/2 Activation in Human Skin Mast Cells. Front Allergy 2022, 3, 930233.

- Wang Z, Franke K, Bal G, Li Z, Zuberbier T, Babina M. MRGPRX2-Mediated Degranulation of Human Skin Mast Cells Requires the Operation of G(alphai), G(alphaq), Ca++ Channels, ERK1/2 and PI3K-Interconnection between Early and Late Signaling. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Bulfone-Paus, S.; Nilsson, G.; Draber, P.; Blank, U.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Positive and Negative Signals in Mast Cell Activation. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitallé, J.; Terrén, I.; Orrantia, A.; Bilbao, A.; Gamboa, P.M.; Borrego, F.; Zenarruzabeitia, O. The Expression and Function of CD300 Molecules in the Main Players of Allergic Responses: Mast Cells, Basophils and Eosinophils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochner, B.S.; O'Sullivan, J.A.; Chang, A.T.; Youngblood, B.A. Siglecs in allergy and asthma. Mol. Asp. Med. 2023, 90, 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, S.; Gibbs, B.F.; Karra, L.; Ben-Zimra, M.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Siglec-7 is an inhibitory receptor on human mast cells and basophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur GK, Cruse G. Regulation of Trafficking and Signaling of the High Affinity IgE Receptor by FcepsilonRIbeta and the Potential Impact of FcepsilonRIbeta Splicing in Allergic Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Gamperl, S.; Stefanzl, G.; Peter, B.; Smiljkovic, D.; Bauer, K.; Willmann, M.; Valent, P.; Hadzijusufovic, E. Effects of ibrutinib on proliferation and histamine release in canine neoplastic mast cells. Veter- Comp. Oncol. 2019, 17, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponuwei, G.A. A glimpse of the ERM proteins. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukita, S.; Yonemura, S. Cortical Actin Organization: Lessons from ERM (Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin) Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 34507–34510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neisch AL, Fehon RG. Ezrin, Radixin and Moesin: key regulators of membrane-cortex interactions and signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2011, 23, 377–382.

- García-Ortiz, A.; Serrador, J.M. ERM Proteins at the Crossroad of Leukocyte Polarization, Migration and Intercellular Adhesion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iontcheva, I.; Amar, S.; Zawawi, K.H.; Kantarci, A.; Van Dyke, T.E. Role for Moesin in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Signal Transduction. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2312–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez JP, Turner JR, Philipson LH. Glucose-induced ERM protein activation and translocation regulates insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010, 299, E772–E785.

- Ben-Aissa, K.; Patino-Lopez, G.; Belkina, N.V.; Maniti, O.; Rosales, T.; Hao, J.-J.; Kruhlak, M.J.; Knutson, J.R.; Picart, C.; Shaw, S. Activation of Moesin, a Protein That Links Actin Cytoskeleton to the Plasma Membrane, Occurs by Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) Binding Sequentially to Two Sites and Releasing an Autoinhibitory Linker. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 16311–16323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Maeda, M.; Doi, Y.; Yonemura, S.; Amano, M.; Kaibuchi, K.; Tsukita, S.; Tsukita, S. Rho-Kinase Phosphorylates COOH-terminal Threonines of Ezrin/Radixin/Moesin (ERM) Proteins and Regulates Their Head-to-Tail Association. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 140, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazki-Hagenbach, P.; Klein, O.; Sagi-Eisenberg, R. The actin cytoskeleton and mast cell function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 72, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Inoh, Y.; Yokawa, S.; Furuno, T.; Hirashima, N. Receptor dynamics regulates actin polymerization state through phosphorylation of cofilin in mast cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 534, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Sun, N.; Han, S.; Song, R.; Che, H. Dok-1 regulates mast cell degranulation negatively through inhibiting calcium-dependent F-actin disassembly. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 238, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanga, J.; Zhang, E.L.; Eitzen, G.; Guo, Y. Mast cell granule motility and exocytosis is driven by dynamic microtubule formation and kinesin-1 motor function. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0265122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navinés-Ferrer, A.; Ainsua-Enrich, E.; Serrano-Candelas, E.; Proaño-Pérez, E.; Muñoz-Cano, R.; Gastaminza, G.; Olivera, A.; Martin, M. MYO1F Regulates IgE and MRGPRX2-Dependent Mast Cell Exocytosis. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 2277–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Angelidou, A.; Asadi, S.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Delivanis, D.-A.; Weng, Z.; Miniati, A.; Vasiadi, M.; Katsarou-Katsari, A.; et al. Human mast cell degranulation and preformed TNF secretion require mitochondrial translocation to exocytosis sites: Relevance to atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 127, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storci, G.; Bonifazi, F.; Garagnani, P.; Olivieri, F.; Bonafè, M. The role of extracellular DNA in COVID-19: Clues from inflamm-aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 66, 101234–101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andargie, T.E.; Tsuji, N.; Seifuddin, F.; Jang, M.K.; Yuen, P.S.; Kong, H.; Tunc, I.; Singh, K.; Charya, A.; Wilkins, K.; et al. Cell-free DNA maps COVID-19 tissue injury and risk of death and can cause tissue injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa TJ, Potje SR, Fraga-Silva TFC, da Silva-Neto JA, Barros PR, Rodrigues D, Machado MR, Martins RB, Santos-Eichler RA, Benatti MN, de Sa KSG, Almado CEL, Castro IA, Pontelli MC, Serra L, Carneiro FS, Becari C, Louzada-Junior P, Oliveira RDR, Zamboni DS, Arruda E, Auxiliadora-Martins M, Giachini FRC, Bonato VLD, Zachara NE, Bomfim GF, Tostes RC. Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 activation contribute to SARS-CoV-2-induced endothelial cell damage. Vascul Pharmacol 2022, 142, 106946. [CrossRef]

- Edinger, F.; Edinger, S.; Koch, C.; Markmann, M.; Hecker, M.; Sander, M.; Schneck, E. Peak Plasma Levels of mtDNA Serve as a Predictive Biomarker for COVID-19 in-Hospital Mortality. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therianou, A.; Vasiadi, M.; Delivanis, D.A.; Petrakopoulou, T.; Katsarou-Katsari, A.; Antoniou, C.; Stratigos, A.; Tsilioni, I.; Katsambas, A.; Rigopoulos, D.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in affected skin and increased mitochondrial DNA in serum from patients with psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilioni I, Natelson B, Theoharides TC. Exosome-Associated Mitochondrial DNA from Patients with ME/CFS Stimulates Human Cultured Microglia to Release IL-1beta. Eur J Neurosci 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Angelidou, A.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Vasiadi, M.; Francis, K.; Asadi, S.; Theoharides, A.; Sideri, K.; Lykouras, L.; Kalogeromitros, D.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA and anti-mitochondrial antibodies in serum of autistic children. J. Neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieghart, W.; Theoharides, T.C.; Alper, S.L.; Douglas, W.W.; Greengard, P. Calcium-dependent protein phosphorylation during secretion by exocytosis in the mast cell. Nature 1978, 275, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

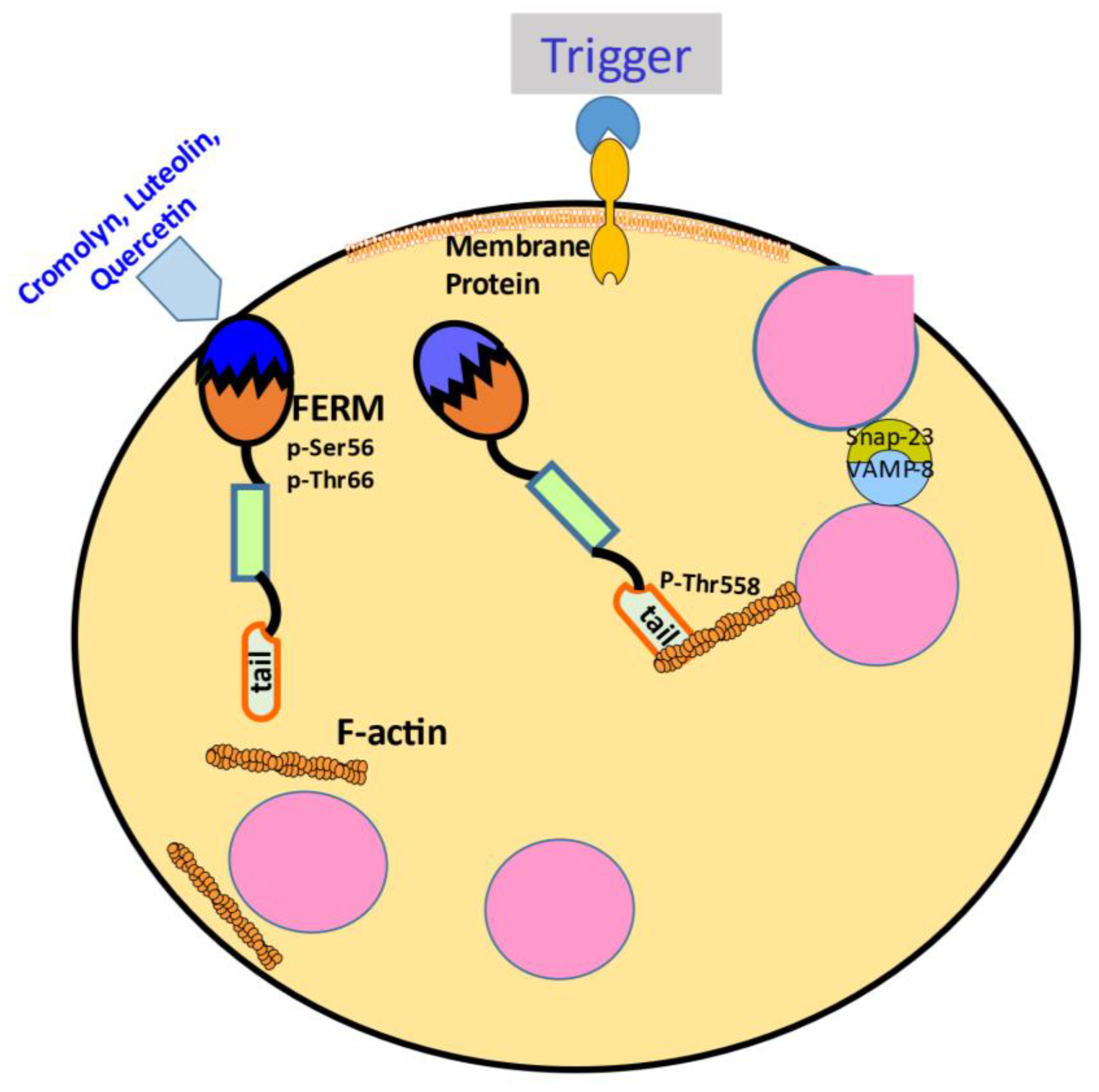

- Theoharides, T.C.; Sieghart, W.; Greengard, P.; Douglas, W.W. Antiallergic Drug Cromolyn May Inhibit Histamine Secretion by Regulating Phosphorylation of a Mast Cell Protein. Science 1980, 207, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj, D.; Madhappan, B.; Christodoulou, S.; Boucher, W.; Cao, J.; Papadopoulou, N.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Theoharides, T.C. Flavonols inhibit proinflammatory mediator release, intracellular calcium ion levels and protein kinase C theta phosphorylation in human mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 145, 934–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Correia, I.; Basu, S.; Theoharides, T.C. Ca2+ and phorbol ester effect on the mast cell phosphoprotein induced by cromolyn. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 371, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Wang, L.; Pang, X.; Letourneau, R.; E Culm, K.; Basu, S.; Wang, Y.; Correia, I. Cloning and cellular localization of the rat mast cell 78-kDa protein phosphorylated in response to the mast cell "stabilizer" cromolyn. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 294. [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides, T.C. The mast cell: a neuroimmunoendocrine master player. Int. J. Tissue React. 1996, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.-S.; Hinds, P.W. Phosphorylation of Ezrin by Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5 Induces the Release of Rho GDP Dissociation Inhibitor to Inhibit Rac1 Activity in Senescent Cells. Cancer Res 2006, 66, 2708–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Alexandrakis, M.; Kempuraj, D.; Lytinas, M. Anti-inflammatory actions of flavonoids and structural requirements for new design. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2003, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, F.J.; Ludowyke, R.I.; Karlsson, N.G. Discovery and Identification of Serine and Threonine Phosphorylated Proteins in Activated Mast Cells: Implications for Regulation of Protein Synthesis in the Rat Basophilic Leukemia Mast Cell Line RBL-2H3. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 3068–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, K.; Asano, S. Pathophysiological Roles of Actin-Binding Scaffold Protein, Ezrin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Luo, J.; Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, N.; Cao, M.; Zhang, C.; Hu, R.; Liu, L. Role of Ezrin in Asthma-Related Airway Inflammation and Remodeling. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, M.E.A.; Gupta, J.K.; Gross, S.R. Ezrin and Its Phosphorylated Thr567 Form Are Key Regulators of Human Extravillous Trophoblast Motility and Invasion. Cells 2023, 12, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Y.; Itoh, M.; Yonemura, S.; Ishihara, S.; Takano, H.; Noda, T.; Tsukita, S.; Tsukita, S. Normal Development of Mice and Unimpaired Cell Adhesion/Cell Motility/Actin-based Cytoskeleton without Compensatory Up-regulation of Ezrin or Radixin in Moesin Gene Knockout. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 2315–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, L.; Robertson, T.F.; Wu, C.F.; Roy, N.H.; Chauvin, S.D.; Perkey, E.; Vanderbeck, A.; Maillard, I.; Burkhardt, J.K. A Murine Model of X-Linked Moesin-Associated Immunodeficiency (X-MAID) Reveals Defects in T Cell Homeostasis and Migration. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 726406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F.; Amieva, M.R.; Furthmayr, H. Phosphorylation of Threonine 558 in the Carboxyl-terminal Actin-binding Domain of Moesin by Thrombin Activation of Human Platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 31377–31385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shcherbina, A.; Kenney, D.M.; Bretscher, A.; Remold-O-Donnell, E. Dynamic association of moesin with the membrane skeleton of thrombin- activated platelets. Blood 1999, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T.; Uher, T.; Schwartz, P.; Buchwald, A.B. Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Moesin in Arachidonic Acid-Stimulated Human Platelets. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 1998, 6, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hishiya, A.; Ohnishi, M.; Tamura, S.; Nakamura, F. Protein Phosphatase 2C Inactivates F-actin Binding of Human Platelet Moesin. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26705–26712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F.; Amieva, M.R.; Hirota, C.; Mizuno, Y.; Furthmayr, H. Phosphorylation of558T of Moesin Detected by Site-Specific Antibodies in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 226, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrin, S.; Alcover, A. Role of ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin) proteins in T lymphocyte polarization, immune synapse formation and in T cell receptor-mediated signaling. Front. Biosci. 2006, 11, 1987–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu H, Espinoza JL, Lu X, Qi Z, Okawa K, Nakao S. Anti-moesin antibodies in the serum of patients with aplastic anemia stimulate peripheral blood mononuclear cells to secrete TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma. J Immunol 2009, 182, 703–710. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Nagao, T.; Itabashi, M.; Hamano, Y.; Sugamata, R.; Yamazaki, Y.; Yumura, W.; Tsukita, S.; Wang, P.-C.; Nakayama, T.; et al. A novel autoantibody against moesin in the serum of patients with MPO-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 29, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Südhof, T.C.; Rothman, J.E. Membrane Fusion: Grappling with SNARE and SM Proteins. Science 2009, 323, 474–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, U.; Cyprien, B.; Martin-Verdeaux, S.; Paumet, F.; Pombo, I.; Rivera, J.; Roa, M.; Varin-Blank, N. SNAREs and associated regulators in the control of exocytosis in the RBL-2H3 mast cell line. Mol. Immunol. 2002, 38, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, A.; Baumann, A.; Vitte, J.; Blank, U. The SNARE Machinery in Mast Cell Secretion. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woska JR, Jr. , Gillespie ME. SNARE complex-mediated degranulation in mast cells. J Cell Mol Med 2012, 16, 649–656. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Verma IM. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 by IkappaB kinase 2 regulates mast cell degranulation. Cell 2008, 134, 485–495.

- Janowicz, Z.A.; Melber, K.; Merckelbach, A.; Jacobs, E.; Harford, N.; Comberbach, M.; Hollenberg, C.P. Simultaneous expression of the S and L surface antigens of hepatitis B, and formation of mixed particles in the methylotrophic yeast,Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast 1991, 7, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.P.; Thon, K.-P.; Bischoff, S.C.; Lorentz, A. SNAP-23 and syntaxin-3 are required for chemokine release by mature human mast cells. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 49, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepp, R.; Puri, N.; Hohenstein, A.C.; Crawford, G.L.; Whiteheart, S.W.; Roche, P.A. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 Regulates Exocytosis from Mast Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 6610–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naskar, P.; Puri, N. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 regulates its dynamic membrane association during Mast Cell exocytosis. Biol. Open 2017, 6, 1257–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Kong, B.; Jung, Y.; Park, J.-B.; Oh, J.-M.; Hwang, J.; Cho, J.Y.; Kweon, D.-H. Soluble N-Ethylmaleimide-Sensitive Factor Attachment Protein Receptor-Derived Peptides for Regulation of Mast Cell Degranulation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam FR, 3rd, Rivas PA, Wendt DJ, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Extracellular pH modulates block of both sodium and calcium channels by nicardipine. Am J Physiol 1990, 259, H1178–H1184.

- Puri, N.; Roche, P.A. Mast cells possess distinct secretory granule subsets whose exocytosis is regulated by different SNARE isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 2580–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paumet, F.; Le Mao, J.; Martin, S.; Galli, T.; David, B.; Blank, U.; Roa, M. Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptors (SNAREs) in RBL-2H3 Mast Cells: Functional Role of Syntaxin 4 in Exocytosis and Identification of a Vesicle-Associated Membrane Protein 8-Containing Secretory Compartment. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 5850–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, L.E.; Frank, S.P.C.; Bolat, S.; Blank, U.; Galli, T.; Bigalke, H.; Bischoff, S.C.; Lorentz, A. Vesicle associated membrane protein (VAMP)-7 and VAMP-8, but not VAMP-2 or VAMP-3, are required for activation-induced degranulation of mature human mast cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Verdeaux, S.; Pombo, I.; Iannascoli, B.; Roa, M.; Varin-Blank, N.; Rivera, J.; Blank, U. Evidence of a role for Munc18-2 and microtubules in mast cell granule exocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Oh, J.-M.; Heo, P.; Shin, J.Y.; Kong, B.; Shin, J.; Lee, J.-C.; Oh, J.S.; Park, K.W.; Lee, C.H.; et al. Polyphenols differentially inhibit degranulation of distinct subsets of vesicles in mast cells by specific interaction with granule-type-dependent SNARE complexes. Biochem. J. 2013, 450, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Heo, P.; Kong, B.; Shin, J.; Jung, Y.-H.; Yoon, K.; Chung, W.-J.; Shin, Y.-K.; Kweon, D.-H. SNARE zippering is hindered by polyphenols in the neuron. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Asadi, S.; Sismanopoulos, N.; Butcher, A.; Fu, X.; Katsarou-Katsari, A.; Antoniou, C.; Theoharides, T.C. Quercetin Is More Effective than Cromolyn in Blocking Human Mast Cell Cytokine Release and Inhibits Contact Dermatitis and Photosensitivity in Humans. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e33805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.C.; Wolf, E.J.; Kagey-Sobotka, A.; Lichtenstein, L.M. Comparison of human lung and intestinal mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1988, 81, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandere-Grzybowska, K.; Kempuraj, D.; Cao, J.; Cetrulo, C.L.; Theoharides, T.C. Regulation of IL-1-induced selective IL-6 release from human mast cells and inhibition by quercetin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieghart, W.; Theoharides, T.C.; Douglas, W.W.; Greengard, P. Phosphorylation of a single mast cell protein in response to drugs that inhibit secretion. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1981, 30, 2737–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Theoharides, T.C. Methoxyluteolin Inhibits Neuropeptide-stimulated Proinflammatory Mediator Release via mTOR Activation from Human Mast Cells. Experiment 2017, 361, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, J.K.; Kulka, M. Decoding Mast Cell-Microglia Communication in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriksen, E.; van Bergeijk, D.; Oosting, R.S.; Redegeld, F.A. Mast cells in neuroinflammation and brain disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 79, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Giusti, P. Neuroinflammation, Microglia and Mast Cells in the Pathophysiology of Neurocognitive Disorders: A Review. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 13, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D.; Facci, L.; Zusso, M.; Giusti, P. Neuroinflammation, Mast Cells, and Glia: Dangerous Liaisons. Neurosci. 2017, 23, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, S. Induction of Microglial Activation by Mediators Released from Mast Cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 38, 1520–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S. Histamine Induces Microglia Activation and the Release of Proinflammatory Mediators in Rat Brain Via H1R or H4R. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2019, 15, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, X.; Yang, H.; Hu, G.; He, S. Mast Cell Tryptase Induces Microglia Activation via Protease-activated Receptor 2 Signaling. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 29, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sha, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y. The Mast Cell Is an Early Activator of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Neuroinflammation and Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in the Hippocampus. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 8098439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kavalioti, M.; Martinotti, R. Factors adversely influencing neurodevelopment. . 2020, 33, 1663–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Qian, Y. Activated brain mast cells contribute to postoperative cognitive dysfunction by evoking microglia activation and neuronal apoptosis. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kavalioti, M.; Tsilioni, I. Mast Cells, Stress, Fear and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, T.C. Ways to Address Perinatal Mast Cell Activation and Focal Brain Inflammation, including Response to SARS-CoV-2, in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Luo, X.; Hao, Y. Microglia: Synaptic modulator in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 958661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampiasi, N.; Bonaventura, R.; Deidda, I.; Zito, F.; Russo, R. Inflammation and the Potential Implication of Macrophage-Microglia Polarization in Human ASD: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Chen, M.; Li, Y. The glial perspective of autism spectrum disorder convergent evidence from postmortem brain and PET studies. Front. Neuroendocr. 2023, 70, 101064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Ahmed, M.E.; Zaheer, S.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zahoor, H.; Saeed, D.; Dubova, I.; Giler, G.; Herr, S.; Iyer, S.S.; Zaheer, A. Mast Cell Proteases Activate Astrocytes Glia-Neurons Release Interleukin-33 by Activating, p. 3.8.; ERK1/2 MAPKs, N.F.-k.a.p.p.a.B. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 1681–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Kempuraj, D.; Ahmed, M.E.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Thangavel, R.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Burton, C.; James, D.; Zaheer, A. Mast Cell Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Tight Junction Protein Derangement in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Saito, D.; Inden, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; Wakimoto, S.; Nakahari, T.; Asano, S. Moesin is involved in microglial activation accompanying morphological changes and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo T, Ou JN, Cao LF, Peng XQ, Li YM, Tian YQ. The Autism-Related lncRNA MSNP1AS Regulates Moesin Protein to Influence the RhoA, Rac1, and PI3K/Akt Pathways and Regulate the Structure and Survival of Neurons. Autism Res 2020, 13, 2073–2082.

- Hoshi Y, Uchida Y, Kuroda T, Tachikawa M, Couraud PO, Suzuki T, Terasaki T. Distinct roles of ezrin, radixin and moesin in maintaining the plasma membrane localizations and functions of human blood-brain barrier transporters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020, 40, 1533–1545.

- Theoharides, T. Mast cells: The immune gate to the brain. Life Sci. 1990, 46, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides TC, Zhang B. Neuro-inflammation, blood-brain barrier, seizures and autism. J Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 168.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Kempuraj, D. Role of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Protein-Induced Activation of Microglia Mast Cells in the Pathogenesis of, N.e.u.r.o.-C.O.V.I.D. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, E., Jr.; Kandaswami, C.; Theoharides, T.C. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000, 52, 673–751. [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Ambriz-Perez, D.L.; Heredia, J.B. Flavonoids as Cytokine Modulators: A Possible Therapy for Inflammation-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, A.K.; Saaby, L. Flavonoids the, C. N.S. Molecules 2011, 16, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calfio, C.; Gonzalez, A.; Singh, S.K.; Rojo, L.E.; Maccioni, R.B. The Emerging Role of Nutraceuticals and Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2020, 77, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Kempuraj, D.D.; Ahmed, M.E.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Govindarajan, R.; Chandrasekaran, P.N.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of flavone luteolin in neuroinflammation and neurotrauma. BioFactors 2020, 47, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calis, Z.; Mogulkoc, R.; Baltaci, A.K. The Roles of Flavonols/Flavonoids in Neurodegeneration and Neuroinflammation. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1475–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theoharides, TC. Could SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Be Responsible for Long-COVID Syndrome? MolNeurobiol 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ashaari, Z.; Hadjzadeh, M.-A.; Hassanzadeh, G.; Alizamir, T.; Yousefi, B.; Keshavarzi, Z.; Mokhtari, T. The Flavone Luteolin Improves Central Nervous System Disorders by Different Mechanisms: A Review. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 65, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezai-Zadeh K, Douglas SR, Bai Y, Tian J, Hou H, Mori T, Zeng J, Obregon D, Town T, Tan J. Flavonoid-mediated presenilin-1 phosphorylation reduces Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid production. J Cell MolMed 2009, 13, 574–588.

- Yao, Z.-H.; Yao, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.-F.; Hu, J.-C. Luteolin Could Improve Cognitive Dysfunction by Inhibiting Neuroinflammation. Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton G, Weaver SR, Burley CV, Low KA, Maclin EL, Johns PW, Pham QS, Lucas SJE, Fabiani M, Rendeiro C. Dietary flavanols improve cerebral cortical oxygenation and cognition in healthy adults. SciRep, 10, 19409. [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.A.; Chamoli, A. Polyphenols as an Effective Therapeutic Intervention Against Cognitive Decline During Normal and Pathological Brain Aging. 2020, 1260, 159–174. [CrossRef]

- Theoharides TC, Stewart JM, Hatziagelaki E, Kolaitis G. Brain "fog," inflammation and obesity: key aspects of 2 neuropsychiatric disorders improved by luteolin. FrontNeurosci 2015, 9, 225.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Cholevas, C.; Polyzoidis, K.; Politis, A. Long-COVID syndrome-associated brain fog and chemofog: Luteolin to the rescue. BioFactors 2021, 47, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, G.B.; Büttiker, P.; Weissenberger, S.; Martin, A.; Ptacek, R.; Kream, R.M. Editorial: The Pathogenesis of Long-Term Neuropsychiatric COVID-19 and the Role of Microglia, Mitochondria, and Persistent Neuroinflammation: A Hypothesis. Experiment 2021, 27, e933015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugon, J.; Msika, E.-F.; Queneau, M.; Farid, K.; Paquet, C. Long COVID: cognitive complaints (brain fog) and dysfunction of the cingulate cortex. J. Neurol. 2021, 269, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Ehrhart, J.; Bai, Y.; Sanberg, P.R.; Bickford, P.; Tan, J.; Shytle, R.D. Apigenin and luteolin modulate microglial activation via inhibition of STAT1-induced CD40 expression. J. Neuroinflammation 2008, 5, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kelley, K.W.; Johnson, R.W. Luteolin reduces IL-6 production in microglia by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation and activation of AP-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 7534–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.B.; Tsilioni, I.; Leeman, S.E.; Theoharides, T.C. Neurotensin stimulates sortilin and mTOR in human microglia inhibitable by methoxyluteolin, a potential therapeutic target for autism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E7049–E7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Z.; Patel, A.B.; Panagiotidou, S.; Theoharides, T.C. The novel flavone tetramethoxyluteolin is a potent inhibitor of human mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 135, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelinger, G.; Merfort, I.; Schempp, C.M. Anti-Oxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Allergic Activities of Luteolin. Planta Medica 2008, 74, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taliou, A.; Zintzaras, E.; Lykouras, L.; Francis, K. An Open-Label Pilot Study of a Formulation Containing the Anti-Inflammatory Flavonoid Luteolin and Its Effects on Behavior in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsilioni, I.; Taliou, A.; Francis, K.; Theoharides, T.C. Children with autism spectrum disorders, who improved with a luteolin-containing dietary formulation, show reduced serum levels of TNF and IL-6. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e647–e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharides, T.C.; Guerra, L.; Patel, K. Successful Treatment of a Patient With Severe COVID-19 Using an Integrated Approach Addressing Mast Cells and Their Mediators. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 118, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Kempuraj, D.D.; Ahmed, M.E.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Raikwar, S.P.; Zaheer, S.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Govindarajan, R.; Chandrasekaran, P.N.; et al. Neuroprotective effects of flavone luteolin in neuroinflammation and neurotrauma. BioFactors 2020, 47, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenbaum, A.S.; Yin, Y.; Sundstrom, J.B.; Bandara, G.; Metcalfe, D.D. Description and Characterization of a Novel Human Mast Cell Line for Scientific Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Vallone, V.F.; He, J.; Frischbutter, S.; Kolkhir, P.; Moñino-Romero, S.; Stachelscheid, H.; Streu-Haddad, V.; Maurer, M.; Siebenhaar, F.; et al. A novel approach for studying mast cell–driven disorders: Mast cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 149, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L'Homme L, Dombrowicz D. In vitro models of human mast cells: How to get more and better with induced pluripotent stem cells? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 149, 904–906. [CrossRef]

- de Toledo, M.A.S.; Fu, X.; Maié, T.; Buhl, E.M.; Götz, K.; Schmitz, S.; Kaiser, A.; Boor, P.; Braunschweig, T.; Chatain, N.; et al. KIT D816V Mast Cells Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Recapitulate Systemic Mastocytosis Transcriptional Profile. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Degranulation (exocytosis) |

| Compound exocytosis |

| Piece meal degranulation |

| Transgranulation |

| Directed degranulation |

| Vesicular (differential) release of mediators |

| Extracellular microvesicles (exosomes) |

| Nanotubules |

| Immunologic synapses |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).