Submitted:

02 July 2023

Posted:

03 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Graph Theory and Spatial Network Analysis

2.1. Space Syntax (SS)

2.2. Multiple Centrality Assessment (MCA)

3. Comparing Space Syntax and Multiple Centrality Assessment

3.1. Principles

- -

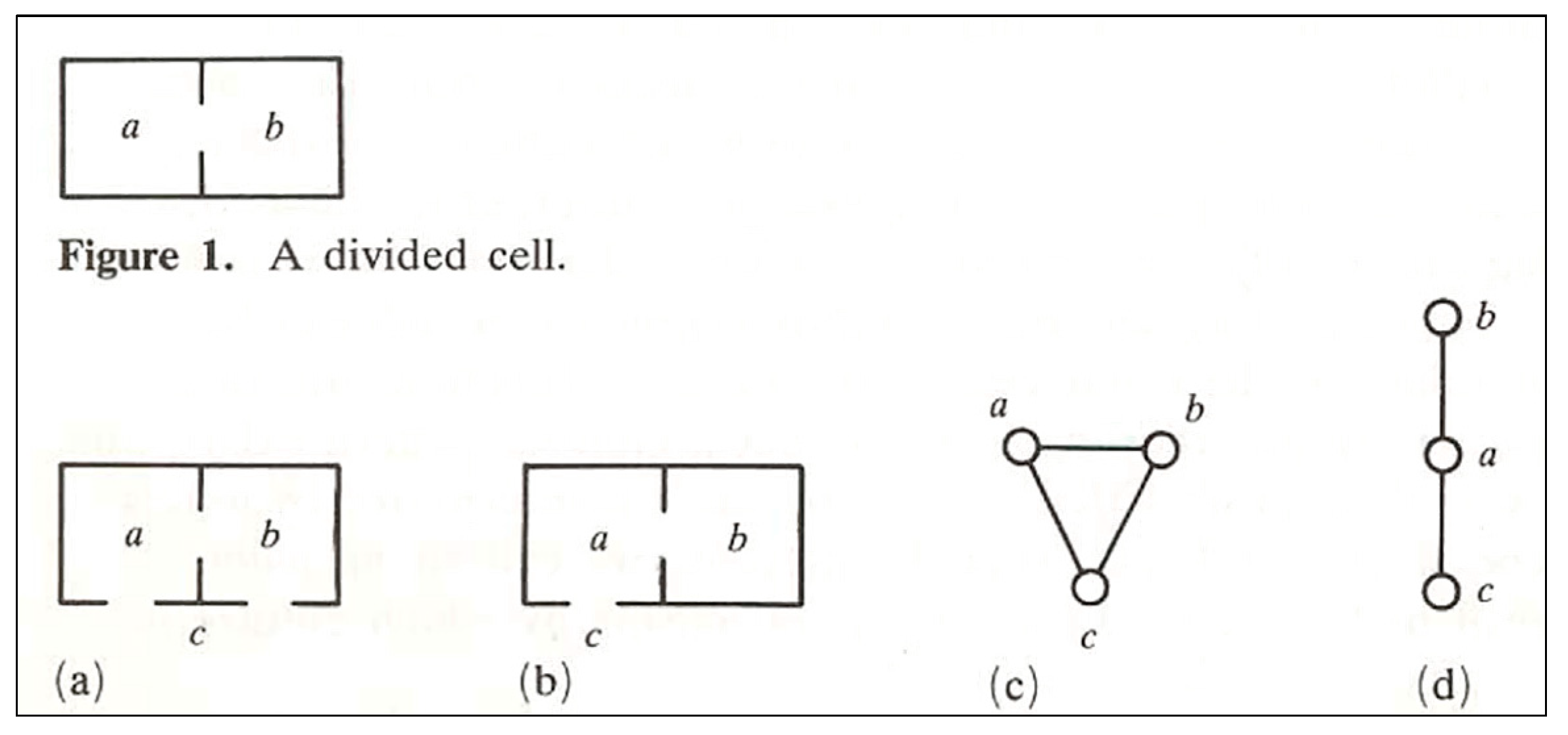

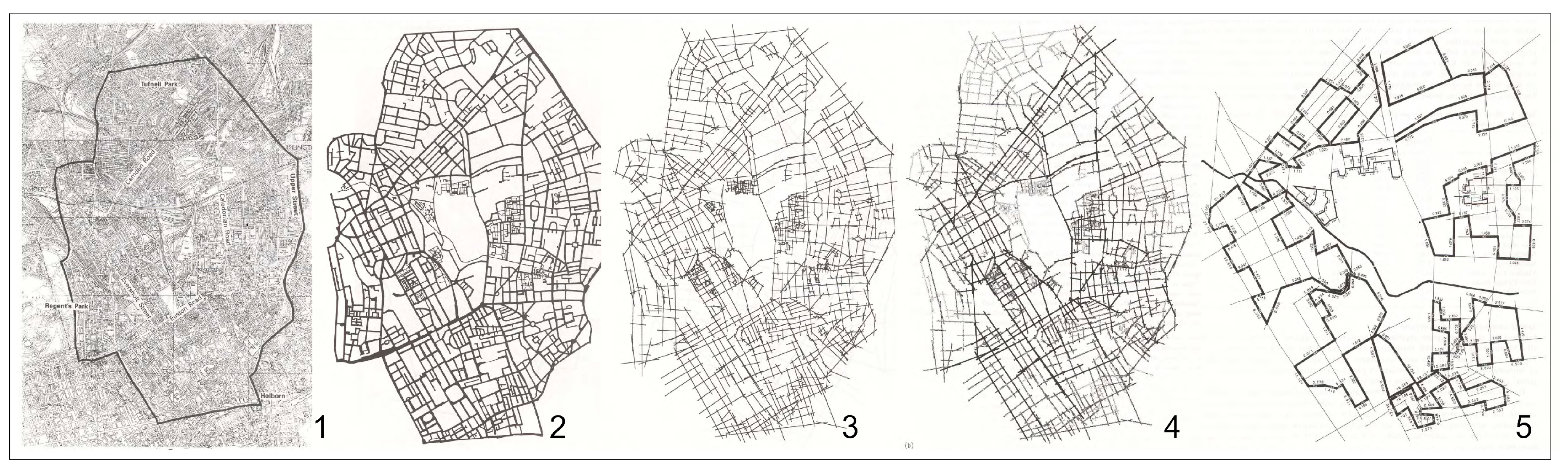

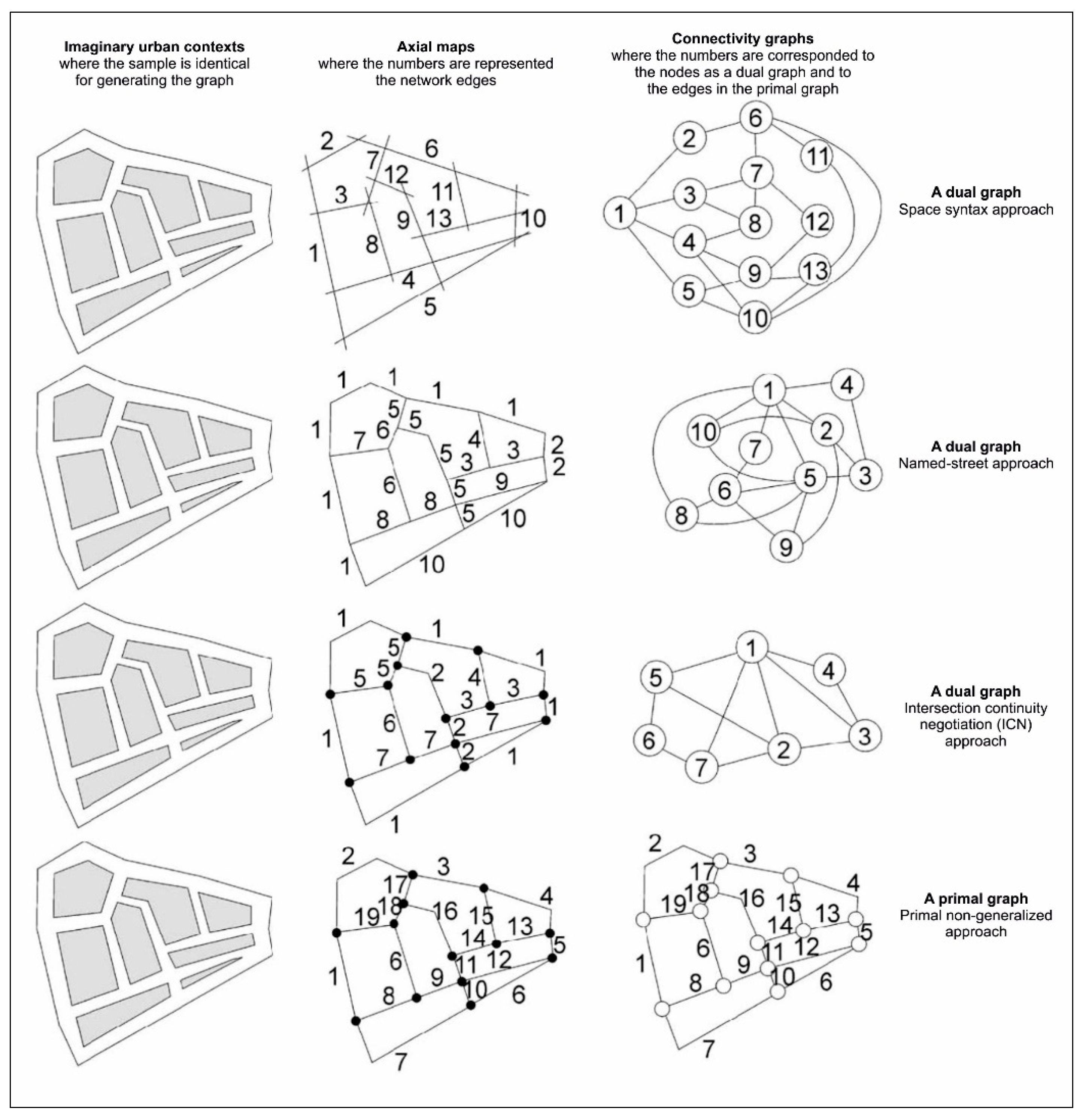

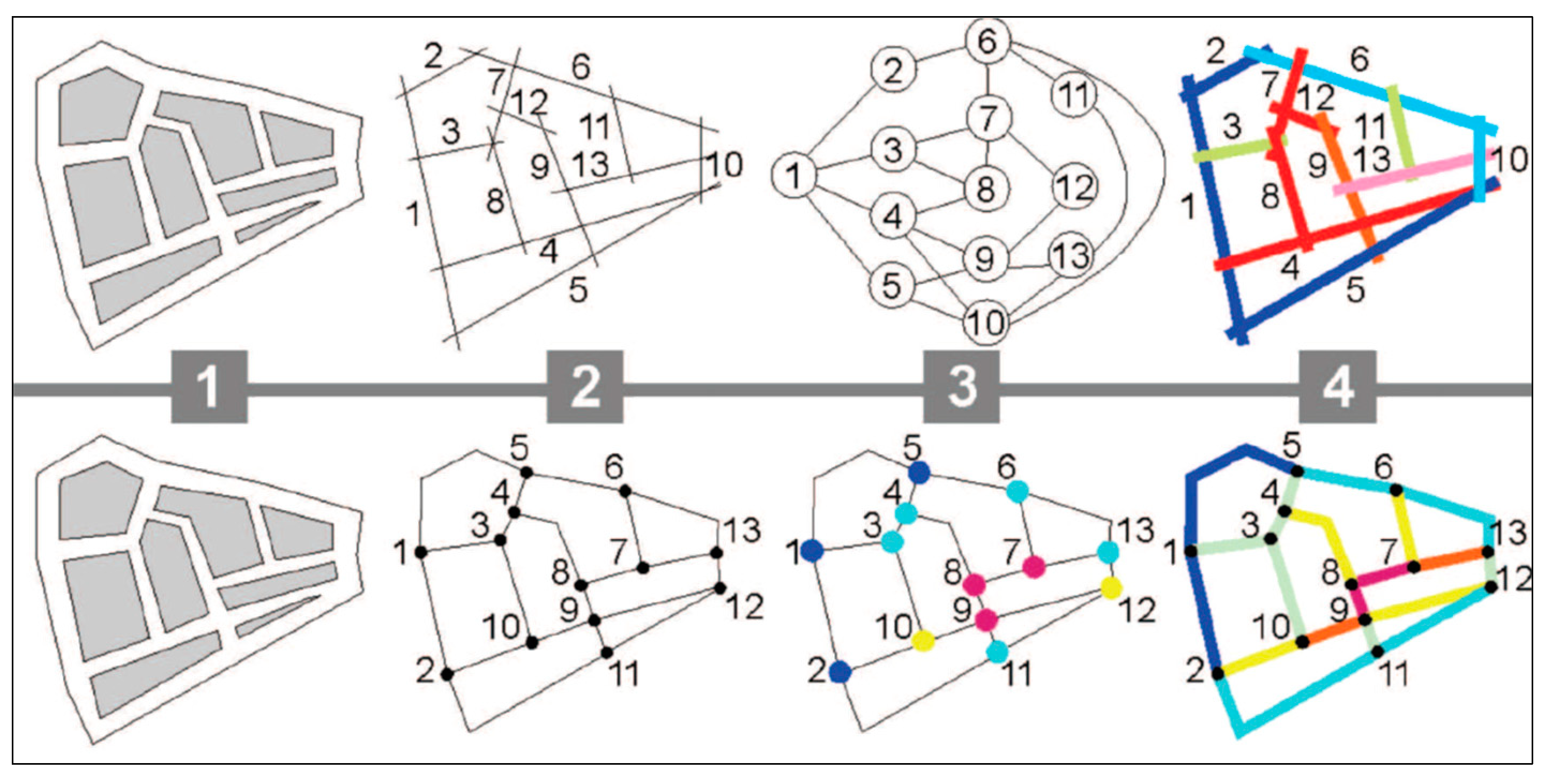

- It relies on the concept of the line of sight where the street pattern is turned into an axial map.

- -

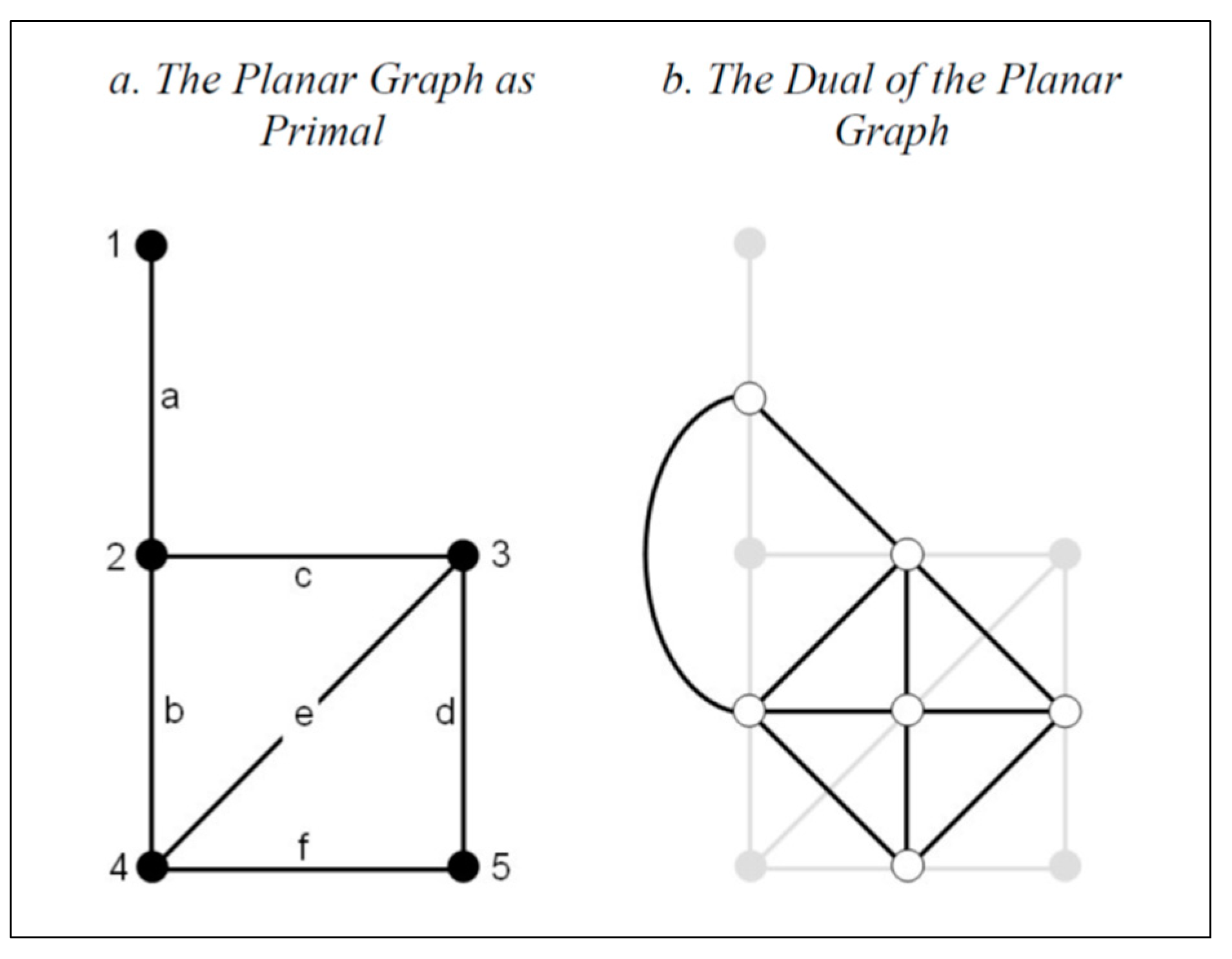

- The axial map is formulated as a dual graph to become what is called a connectivity graph. This connectivity graph expresses the streets as nodes (N) and intersections as edges or links (K).

- -

- The Space Syntax methodology (regarding the index of integration) is based on the analytical key of spatial organisation. The primary equation of integration can be formulated as:

- -

- The integration index, however, will be represented in a coloured graph where each single coloured line is a value of integration. Theoretically and practically, Space Syntax deals with the dual approach; this differs from a network exemplification, which is a geographic system and primal process. Therefore, integration illustrates the value of lines in terms of their relative positions within the global spatial network by depending on the number of mediated steps with others.

- -

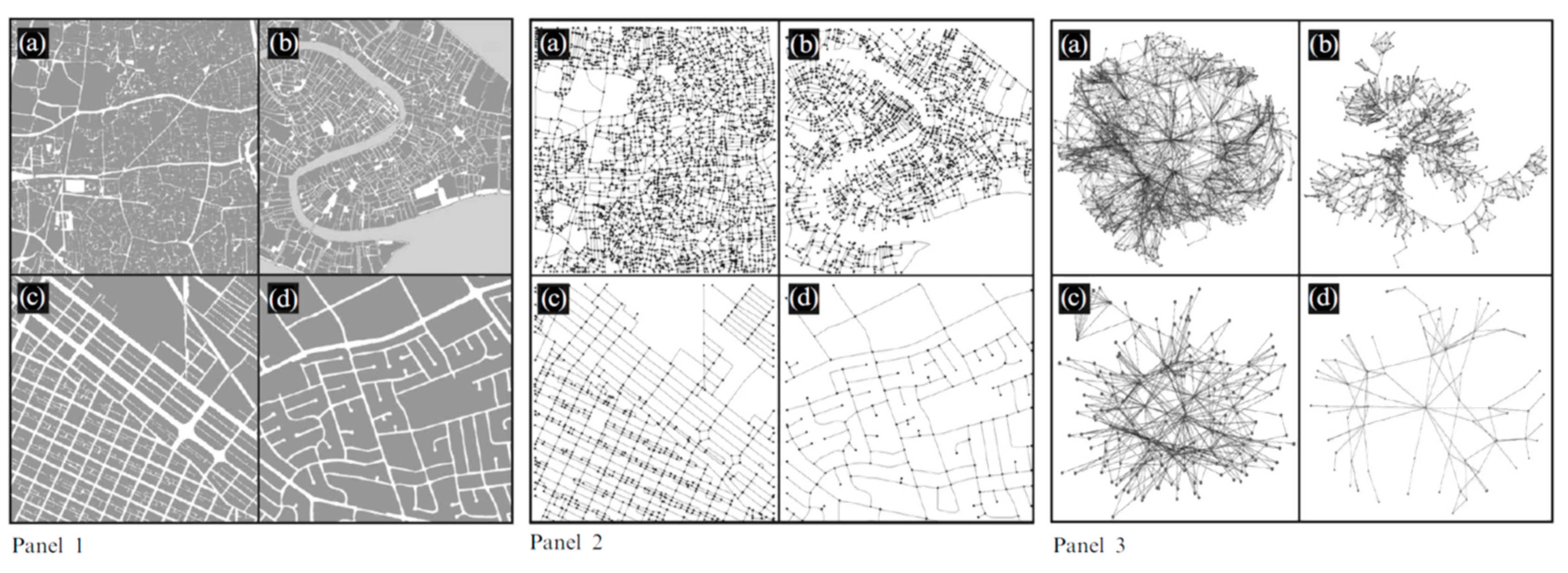

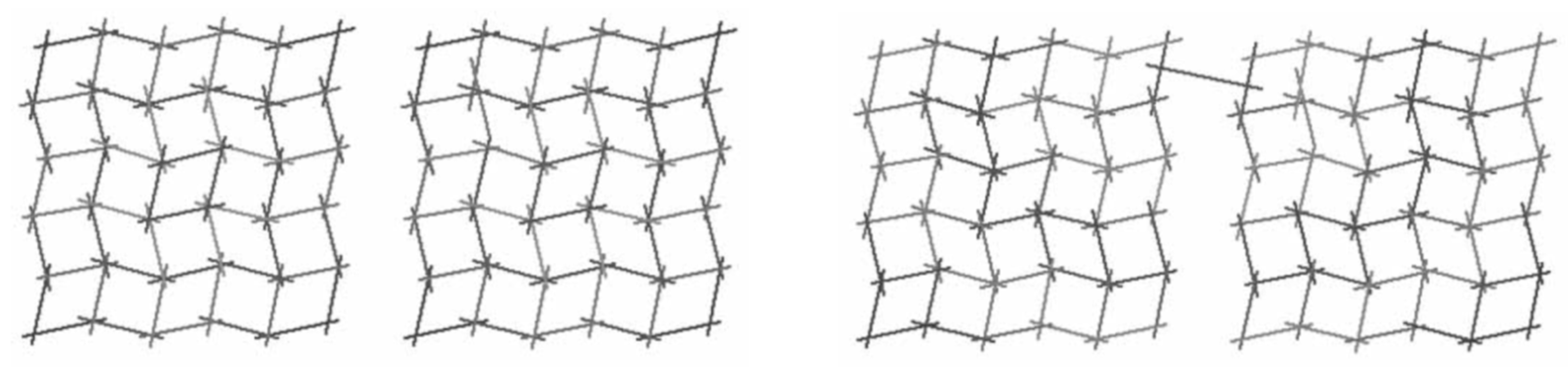

- The street pattern creates the primal graph where the intersections are represented as nodes, and the streets serve as edges or links. The edges reflect the metric distance of real streets. Each street length responds to the single edge in the primal graph, where the metric dimension of the street network is analysed both topologically and geographically.

- -

- A node in the primal graph is subject to four types of centrality, namely: closeness CC, betweenness CB, straightness CS and information CI.

- -

- The analytical values are coded and coloured in the primal graph to weight the centrality of each node.

- -

- Calculating the average of their paired nodes computerises the centrality of the edges. The importance of the end-nodes for every single edge is represented in the axial graph where each edge has its colour and code.

3.2. Structural Generational Model

3.3. Topological, Geometrical and Metric Representation

3.4. Edge Effect in Spatial Network Analysis

3.5. Two-Dimensional Representation in Spatial Network Analysis

3.6. Urban Form Elements and Land Use

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Al-Saaidy, H. J. E. (2019). Measuring urban form and urban life: four case studies in Baghdad, Iraq. Architecture. United Kingdom, University of Strathclyde, Department of Architecture, United Kingdom UK. Doctor of Philosophy.

- Al-Saaidy, H. J. E. and D. Alobaydi (2021b). "Studying street centrality and human density in different urban forms in Baghdad, Iraq." Ain Shams Engineering Journal 12(1): 1111-1121. [CrossRef]

- Alobaydi, D. and M. Rashid (2015). Evolving Syntactic Structures of Baghdad - Introducing 'transect' as a way to study morphological evolution. The 10th Space Syntax Symposium (SSS10) from 13 to 17 July 2015, University College London, Bloomsbury, London, UK.

- Batty, M. (2004). "A new theory of space syntax." Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College London, 1-19 Torrington Place, London WC1E 6BT, UK.

- Batty, M. and S. Rana (2002). "Reformulating space syntax: the automatic definition and generation of axial lines and axial maps." Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis Working Paper 58.

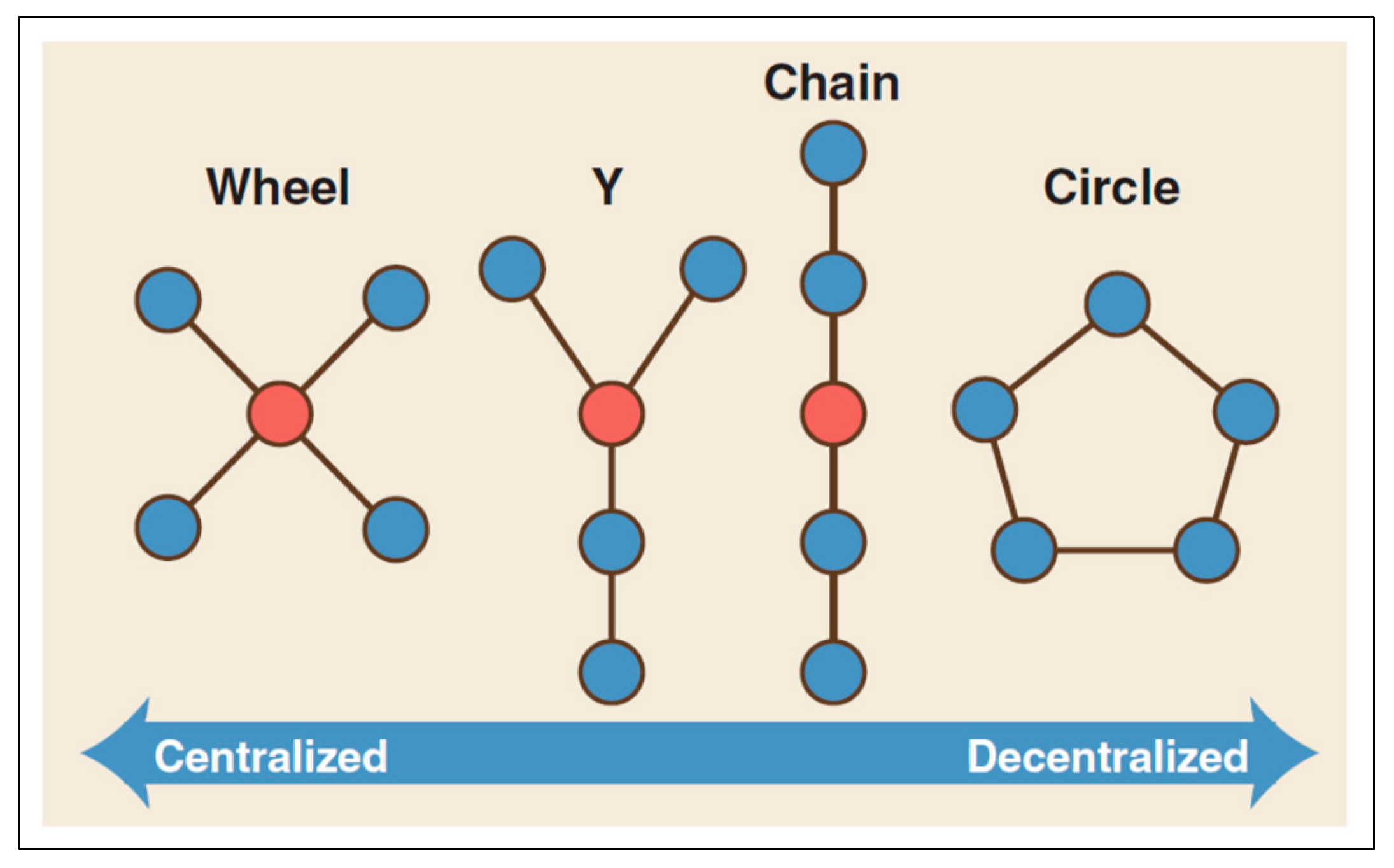

- Bavelas, A. (1948) A mathematical model for group structures. Human organization 7, 16-30. 7. [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, A. (1950). "Communication patterns in task-oriented groups." The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 22(6): 725-730.

- Bavelas, A. and D. Barrett (1951). An experimental approach to organizational communication, American Management Association.

- Borgatti, S. P., A. Mehra, et al. (2009). "Network analysis in the social sciences." science 323(5916): 892-895.

- Cardillo, A., S. Scellato, et al. (2006). "Structural properties of planar graphs of urban street patterns." Physical Review E 73(6): 066107.

- Cohn, B. S. and M. Marriott (1958). "Networks and centres of integration in India civilization." Journal of Social Research 1: 1-9.

- Crucitti, P., V. Latora, et al. (2006a). "Centrality measures in spatial networks of urban streets." Physical Review E 73(3): 036125,.

- Crucitti, P., V. Latora, et al. (2006b). "Centrality in networks of urban streets." Chaos: an interdisciplinary journal of nonlinear science 16(1): 015113.

- Dalton, N., J. Peponis, et al. (2003). "To tame a TIGER one has to know its nature: extending weighted angular integration analysis to the descriptionof GIS road-centerline data for large scale urban analysis.".

- Freeman, L. C. (1977) A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. C. (1979) Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Social networks 1, 215-239, 1. [CrossRef]

- Garau, C., A. Annunziata, et al. (2020). "A walkability assessment tool coupling multi-criteria analysis and space syntax: The case study of Iglesias, Italy." European Planning Studies: 1-23.

- Gastner, M. T. and M. E. Newman (2006). "The spatial structure of networks." The European Physical Journal B-Condensed Matter and Complex Systems 49(2): 247-252.

- Gehl, J. (2010a). Cities for people, Washington : Island Press.

- Hall, E. T. (1959). The silent language, Doubleday, New York, USA.

- Hillier, B. (1999b). "The hidden geometry of deformed grids: or, why space syntax works, when it looks as though it shouldn't." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 26: 169-191.

- Hillier, B. and J. Hanson (1984). The social logic of space, Cambridge Cambridgeshire ; New York : Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B., J. Hanson, et al. (1987). "Ideas are in things: an application of the space syntax method to discovering house genotypes." 14(4).

- Hillier, B., A. Leaman, et al. (1976). "Space syntax." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 3(2): 147-185.

- Hillier, B. and A. Penn (2004). "Rejoinder to carlo ratti." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31(4): 501-511.

- Hillier, B., A. Penn, et al. (1993a). "Natural movement-or, configuration and attraction in urban pedestrian movement." Environment and Planning B-Planning & Design 20(1): 29-66.

- Jiang, B. (2007). "A topological pattern of urban street networks: universality and peculiarity." Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 384(2): 647-655.

- Leavitt, H., J (1951). "Some effects of communication patterns on group performance." The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 46: 38-50.

- Leavitt, H. J. (1949). Some effects of certain communication patterns on group performance. Cambridge, Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. PhD dissertation.

- Lin, G., X. Chen, et al. (2018). "The location of retail stores and street centrality in Guangzhou, China." Applied geography 100: 12-20.

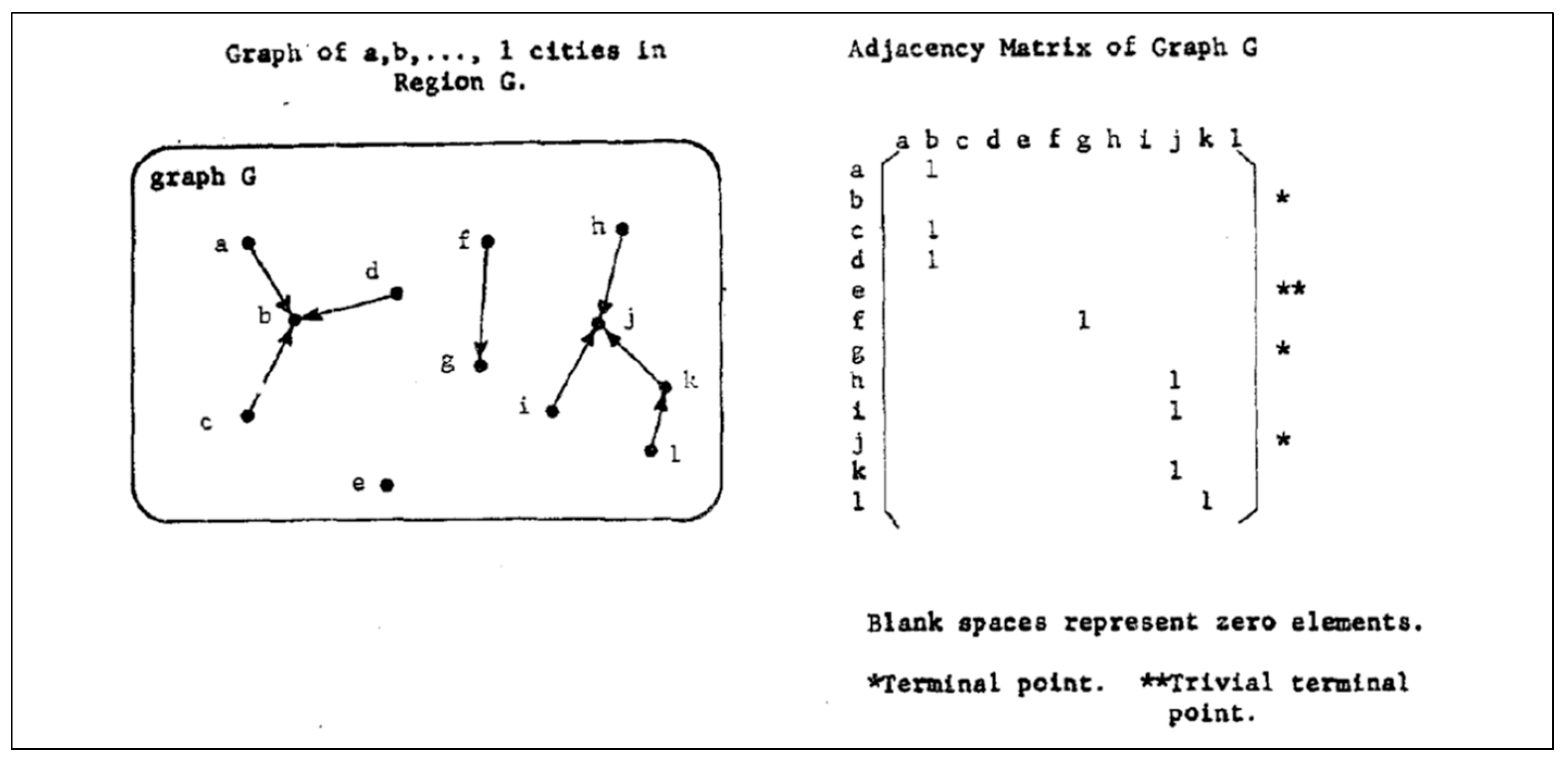

- Nystuen, J. D. and M. F. Dacey (1961). "A graph theory interpretation of nodal regions." Papers in Regional Science 7(1): 29-42.

- Pafka, E., K. Dovey, et al. (2020). "Limits of space syntax for urban design: Axiality, scale and sinuosity." Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 47(3): 508-522.

- Peponis, J., J. Wineman, et al. (1998). "On the generation of linear representations of spatial configuration." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 25(4): 559-576.

- Pitts, F. R. (1965). "A graph theoretic approach to historical geography." The professional geographer 17(5): 15-20.

- Porta, S., P. Crucitti, et al. (2006a). "The network analysis of urban streets: A primal approach." Environment and Planning B Planning and Design 33(5): 705-725. [CrossRef]

- Porta, S., P. Crucitti, et al. (2006b). "The network analysis of urban streets: A dual approach." Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 369(2): 853-866. [CrossRef]

- Porta, S., S., et al. (2009). "Street centrality and densities of retail and services in Bologna, Italy." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 36(3): 450-465. [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C. (2004). "Urban texture and space syntax: some inconsistencies." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31(4): 487-499.

- Remali, A. M. (2014). Capturing the essence of the capital city : urban form and urban life in the city centre of Tripoli, Libya. Department of, Architecture, University of Strathclyde.

- Rogers, A. V., Steven (1995). The urban context : ethnicity, social networks, and situational analysis, Oxford England ; Washington, D.C. : Berg Publishers.

- Smith, S. L. (1950). "Communication pattern and the adaptability of task-oriented groups: an experimental study." Group Networks Laboratory, Research Laboratory of Electronics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

- Thomson, R. C. (2004). Bending the axial line: Smoothly continuous road centre-line segments as. Proceedings 4th International Space Syntax Symposium, London, UK.

- Turner, A. (2007). "From axial to road-centre lines: a new representation for space syntax and a new model of route choice for transport network analysis." Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 34(3): 539-555.

- van Nes, A. and C. Yamu (2017). Space Syntax: A method to measure urban space related to social, economic and cognitive factors. The virtual and the real in planning and urban design, Routledge: 136-150.

- van Nes, A. and C. Yamu (2021). Introduction to space syntax in urban studies, Springer Nature.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).